Eighty Years' War, 1566–1572 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The period between the start of the

The period between the start of the

The atmosphere in the Netherlands was tense due to preaching of

The atmosphere in the Netherlands was tense due to preaching of

The many exiles found asylum in the few areas in neighboring countries that welcomed Calvinists, like the

The many exiles found asylum in the few areas in neighboring countries that welcomed Calvinists, like the

The period between the start of the

The period between the start of the Beeldenstorm

''Beeldenstorm'' () in Dutch and ''Bildersturm'' in German (roughly translatable from both languages as 'attack on the images or statues') are terms used for outbreaks of destruction of religious images that occurred in Europe in the 16th centu ...

in August 1566 until early 1572 (before the Capture of Brielle on 1 April 1572) contained the first events of a series that would later be known as the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

between the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

and disparate groups of rebels in the Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands were the parts of the Low Countries that were ruled by sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. This rule began in 1482 and ended for the Northern Netherlands in 1581 and for the Southern Netherlands in 1797. ...

. Some of the first pitched battles and sieges between radical Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

s and Habsburg governmental forces took place in the years 1566–1567, followed by the arrival and government takeover by Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba

Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel, 3rd Duke of Alba (29 October 150711 December 1582), known as the Grand Duke of Alba (, ) in Spain and Portugal and as the Iron Duke () or shortly 'Alva' in the Netherlands, was a Spaniards, Spanish noblema ...

(simply known as "Alba" or "Alva") with an army of 10,000 Spanish and Italian soldiers. Next, an ill-fated invasion by the most powerful nobleman of the Low Countries, the exiled but still-Catholic William "the Silent" of Orange, failed to inspire a general anti-government revolt. Although the war seemed over before it got underway, in the years 1569–1571, Alba's repression grew severe, and opposition against his regime mounted to new heights and became susceptible to rebellion.

Although virtually all historians place the start of the war somewhere in this period, there is no historical consensus on which exact event should be considered to have begun the war. Consequently, there is no agreement whether the war really lasted exactly eighty years. For this and other reasons, some historians have endeavoured to replace the name "Eighty Years' War" with "Dutch Revolt", but there is also no consensus either to which period the term "Dutch Revolt" should apply (be it the prelude to the war, the initial stage(s) of the war, or the entire war).

Origins

Events and developments

''Beeldenstorm'' (August–November 1566)

Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

leaders, hunger after the bad harvest of 1565, and economic difficulties due to the Northern Seven Years' War

The Northern Seven Years' War (also known as the ''Nordic Seven Years' War'', the ''First Northern War,'' the ''Seven Years' War of the North'' or the ''Seven Years War in Scandinavia'') was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden (1523–1611), K ...

. The Compromise of Nobles

The Compromise of Nobles (; ) was a covenant of members of the nobility in the Habsburg Netherlands who came together to submit a petition to the Regent Margaret of Parma on 5 April 1566, with the objective of obtaining a moderation of the ''pl ...

led to the lesser nobility of the Habsburg Netherlands offering a petition to governor-general Margaret of Parma

Margaret (; 5 July 1522 – 18 January 1586) was Duchess of Parma from 1547 to 1586 as the wife of Duke Ottavio Farnese and Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1559 to 1567 and from 1578 to 1582. She was the illegitimate daughter of Ch ...

on 5 April 1566 to moderate the ''placards'' against heresy which were used for persecuting Protestants. One of her aides supposedly insulted the nobles by calling them ''gueux'', French for "beggars"; this word evolved to Dutch ''geuzen

''Geuzen'' (; ; ) was a name assumed by the confederacy of Calvinist Dutch nobles, who from 1566 opposed Spanish rule in the Netherlands. The most successful group of them operated at sea, and so were called ''Watergeuzen'' (; ; ). In the Eigh ...

'' which the nobles and other dissidents would soon reappropriate as a badge of pride. On 9 April, the duchess decided to temporarily suspend them and await further instructions from king Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

on what to do, but suspension of the ''placards'' emboldened the Protestants. Some returned from exile. Calvinists started to organise open-air sermons (, "hedge-sermons") outside the city walls of many cities. Though these meetings were peaceful, their size alone caused anxiety for the authorities, especially as some of the people attending bore arms. Then, the situation deteriorated rapidly. On 1 August 1566, 2000 armed Calvinists tried to force entry to the walled town of Veurne

Veurne (; , ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality in the Belgium, Belgian Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the town of Veurne proper and the settlements of , , ...

, but they failed. They were led by , who was a hatmaker by trade, but turned into a Calvinist preacher. He and other Calvinist weavers from the industrial area around Ypres

Ypres ( ; ; ; ; ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality comprises the city of Ypres/Ieper ...

such as then started attacking churches and destroying religious statuary in western Flanders. On 10 August 1566, their first target was a monastery church at Steenvoorde in Flanders (now in Northern France), which was sacked by a mob led by Sebastiaan Matte. This incident was followed by similar riots elsewhere in Flanders, and before long the Netherlands had become the scene of the Beeldenstorm

''Beeldenstorm'' () in Dutch and ''Bildersturm'' in German (roughly translatable from both languages as 'attack on the images or statues') are terms used for outbreaks of destruction of religious images that occurred in Europe in the 16th centu ...

. This iconoclastic

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

movement was planned and organised by prominent Calvinists, who supervised the actions of men (who had no property themselves) in storming churches and other religious buildings to desecrate and destroy church art and all kinds of decorative fittings over most of the country. The number of actual statue-breakers appears to have been relatively small, and the exact backgrounds of the movement are debated, but in general local authorities did not rein in the vandalism

Vandalism is the action involving deliberate destruction of or damage to public or private property.

The term includes property damage, such as graffiti and defacement directed towards any property without permission of the owner. The t ...

. The actions of the iconoclasts drove the nobility into two camps, with Orange and other grandee

Grandee (; , ) is an official royal and noble ranks, aristocratic title conferred on some Spanish nobility. Holders of this dignity enjoyed similar privileges to those of the peerage of France during the , though in neither country did they ha ...

s opposing the movement and others, notably Hendrick van Brederode, supporting it.

First battles and repression (December 1566 – March 1567)

The authorities at first did not react. The central government was especially disturbed by the fact that in many cases the civic militias refused to intervene. This seemed to portend insurrection. Margaret, and also authorities at lower levels, feared insurrection and made further concessions to the Calvinists, such as designating certain churches for Calvinist worship. Some provincialstadtholder

In the Low Countries, a stadtholder ( ) was a steward, first appointed as a medieval official and ultimately functioning as a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and ...

s used force to confront the unrest, foremost Philip of Noircarmes of Hainaut, who suppressed the revolt of the Calvinists led by Guido de Bres

Guido de Bres (also known as Guido de Bray,L.A. van Langeraad, ''Guido de Bray Zijn Leven en Werken'', Zierikzee: S.Ochtman en Zoon 1884 p.9, 13 Guy de Bray and Guido de Brès, 1522 – 31 May 1567) was a Walloon pastor, Protestant reformer and ...

during the Siege of Valenciennes (6 December 1566 – 23 March 1567). After the parties could not reach a compromise, and Valenciennes refused to accept a royal garrison, the city was declared in a state of rebellion on 14 December 1566. Rebel attempts to relieve Valenciennes were crushed in the Battle of Wattrelos (27 December 1566) and the Battle of Lannoy (29 December 1566). For his part as stadtholder of Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

and Zeeland

Zeeland (; ), historically known in English by the Endonym and exonym, exonym Zealand, is the westernmost and least populous province of the Netherlands. The province, located in the southwest of the country, borders North Brabant to the east ...

, William of Orange took decisive action to quell the disturbances.

Other noblemen attempted a more conciliatory approach. After the Beeldenstorm reached the city of Tournai

Tournai ( , ; ; ; , sometimes Anglicisation (linguistics), anglicised in older sources as "Tournay") is a city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia located in the Hainaut Province, Province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies by ...

on 23 August 1566, the Calvinists (who claimed to constitute three fourths of Tournai's population) demanded their own church buildings. Margaret of Parma dispatched Philip de Montmorency, Count of Horn

Philip de Montmorency (ca. 1524 – 5 June 1568 in Brussels), also known as Count of County of Horn, Horn, ''Horne'', ''Hoorne'' or ''Hoorn'', was a victim of the Inquisition in the Spanish Netherlands.

Biography

De Montmorency was born as the e ...

to restore order, and he sought to achieve this through a kind of religious peace, including allowing the Calvinists to build their own churches. Margaret of Parma and king Philip resented him for this, and they recalled Horne.Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993-2002) s.v. ''Horne''. Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum. In January 1567, Philip of Noircarmes retook Tournai.

On 13 March 1567 at the Battle of Oosterweel

The Battle of Oosterweel took place on 13 March 1567 near the village of , near Antwerp, in present-day Belgium, and is traditionally seen as the beginning of the Eighty Years' War. A Spanish mercenary army surprised a band of rebels and kille ...

, Calvinists under John of St. Aldegonde were defeated by a royalist army and all rebels summarily executed. Orange prevented the citizens of nearby Antwerp to come to the rebels' aid. Margaret of Parma sent Lamoral, Count of Egmont

Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Prince of Gavere (18 November 1522 – 5 June 1568) was a general and statesman in the Habsburg Netherlands, Spanish Netherlands just before the start of the Eighty Years' War, whose execution helped spark the national up ...

and Philippe III de Croÿ, Duke of Aarschot to Valenciennes to negotiate with the rebels, but the talks broke down. A cannonade of the city forced the Calvinist rebels to surrender, and on 23 March (Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is the Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Its name originates from the palm bran ...

) Noircarmes entered Valenciennes. Protestant leaders Peregrin de la Grange and Guido de Bres

Guido de Bres (also known as Guido de Bray,L.A. van Langeraad, ''Guido de Bray Zijn Leven en Werken'', Zierikzee: S.Ochtman en Zoon 1884 p.9, 13 Guy de Bray and Guido de Brès, 1522 – 31 May 1567) was a Walloon pastor, Protestant reformer and ...

initially escaped, but were soon captured, and were both hanged on 31 May 1567. Due to Valenciennes' capitulation, other Calvinist strongholds quickly surrendered.

Arrival and takeover of Alba (April 1567 – June 1568)

In April 1567, Margaret reported to her brother Philip II that order had been restored. However, news travelled slowly and the court in Madrid had received a rather exaggerated impression of the severity of the situation. Even before he answered the petition by the nobles, Philip believed he had lost control in the troublesome Netherlands, and came to the conclusion that there was no other option than to send an army to suppress the rebellion. In September 1566, Philip had decided to travel himself to the Netherlands to restore order, but debate among the two factions at the Spanish court, led by theDuke of Alba

Duke of Alba de Tormes (), commonly known as Duke of Alba, is a title of Spanish nobility that is accompanied by the dignity of Grandee of Spain. In 1472, the title of ''Count of Alba de Tormes'', inherited by García Álvarez de Toledo, wa ...

and the Prince of Éboli, about the advisability of this journey grew fierce. Eventually it was decided to send an army from Italy under the command of Alba. Margaret's emissary arrived at the court on 17 April 1567, the same day that Alba and his army departed on their mission from Cartagena, Spain

Cartagena () is a Spanish city belonging to the Region of Murcia. As of January 2018, it has a population of 218,943 inhabitants. The city lies in a natural harbor of the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula. Cartage ...

by ship, too late to prevent the fateful intervention.

Alba's army of Spanish and Italian mercenaries reached the Netherlands by way of the Spanish Road

The Spanish Road was a military road and trade route linking Spanish territories in Flanders with those in Italy. It was in use from approximately 1567 to 1648.

The Road was created to support the Spanish war effort in the Eighty Years' War ag ...

, passing Thionville

Thionville (; ; ) is a city in the northeastern French Departments of France, department of Moselle (department), Moselle. The city is located on the left bank of the river Moselle (river), Moselle, opposite its suburb Yutz.

History

Thionvi ...

in Luxemburg on 3 August 1567. On 22 August 1567, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba

Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel, 3rd Duke of Alba (29 October 150711 December 1582), known as the Grand Duke of Alba (, ) in Spain and Portugal and as the Iron Duke () or shortly 'Alva' in the Netherlands, was a Spaniards, Spanish noblema ...

, marched into Brussels at the head of 10,000 troops. Over the course of six years, the army grew to 67,000 men. Alba was supposed to act as military captain-general, while Margaret would remain in office as civil governor-general. Alba took harsh measures, and rapidly established a special court (''Raad van Beroerten'' or Council of Troubles) on 5 September 1567 to put anyone who opposed the king in some way on trial. The Council conducted a campaign of repression of suspected heretics and people deemed guilty of the (already extinguished) insurrection. The Council used its power to override the civilian authorities in arresting suspects. Alba considered himself the direct representative of Philip in the Netherlands and therefore frequently bypassed Margaret of Parma

Margaret (; 5 July 1522 – 18 January 1586) was Duchess of Parma from 1547 to 1586 as the wife of Duke Ottavio Farnese and Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1559 to 1567 and from 1578 to 1582. She was the illegitimate daughter of Ch ...

, the king's half-sister who had been appointed governor of the Netherlands. He made use of her to lure back some of the fugitive nobles, notably the counts of Egmont and Horn

Horn may refer to:

Common uses

* Horn (acoustic), a tapered sound guide

** Horn antenna

** Horn loudspeaker

** Vehicle horn

** Train horn

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various animals

* Horn (instrument), a family ...

, causing her to resign office in September 1567. Rather than working with Margaret, Alba took over command and Margaret resigned in protest.

Alba thereafter was in sole command. Many high-ranking officials were arrested on various pretexts, among whom the Counts of Egmont and Horn

Horn may refer to:

Common uses

* Horn (acoustic), a tapered sound guide

** Horn antenna

** Horn loudspeaker

** Vehicle horn

** Train horn

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various animals

* Horn (instrument), a family ...

. The victims of the repression were found in all social strata. A total of about 9,000 people were eventually convicted by the council, though only 1,000 were actually executed, as many managed to go into exile. One of the latter was Orange, who forfeited his extensive possessions in the Netherlands, like most of the people being proscribed

Proscription () is, in current usage, a 'decree of condemnation to death or banishment' (''Oxford English Dictionary'') and can be used in a political context to refer to state-approved murder or banishment. The term originated in Ancient Rome ...

. The victims were not necessarily only Protestants. For instance, the Counts of Egmont and Horne, executed for treason on 5 June 1568, protested their Catholic orthodoxy on the scaffold.

Egmont and Horne were arrested for high treason, condemned, and a year later beheaded

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood by way of severing through the jugular vein and common c ...

on the Grand-Place

The (French language, French, ; "Grand Square"; also used in English) or (Dutch language, Dutch, ; "Big Market") is the central Town square, square of Brussels, Belgium. It is surrounded by opulent Baroque architecture, Baroque guildhalls of ...

in Brussels. Egmont and Horne had been Catholic nobles, loyal to the King of Spain until their deaths. The reason for their execution was that Alba considered they had been treasonous to the king in their tolerance to Protestantism. Their executions, ordered by a Spanish noble, provoked outrage. More than one thousand people were executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

in the following months. The large number of executions led the court to be nicknamed the "Blood Court" in the Netherlands, and Alba to be called the "Iron Duke". Rather than pacifying the Netherlands, these measures helped to fuel the unrest.

Opposition in exile (April 1567 – April 1568)

The many exiles found asylum in the few areas in neighboring countries that welcomed Calvinists, like the

The many exiles found asylum in the few areas in neighboring countries that welcomed Calvinists, like the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

areas in France, England, and Emden

Emden () is an Independent city (Germany), independent town and seaport in Lower Saxony in the north-west of Germany and lies on the River Ems (river), Ems, close to the Germany–Netherlands border, Netherlands border. It is the main town in t ...

or Wesel

Wesel () is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, in western Germany. It is the capital of the Wesel (district), Wesel district.

Geography

Wesel is situated at the confluence of the Lippe River and the Rhine.

Division of the city

Suburbs of Wesel i ...

in Germany. Many were ready to join an armed fight, but the fate of the rebels at Oosterweel had shown that irregular forces did not stand a chance against well-disciplined troops. A better organised effort was needed to lead such an effort, and Orange was uniquely well-placed. As a sovereign prince of the Holy Roman Empire Orange was in a sense the equal of Philip, in his capacity of Count of Holland, for instance. Orange was therefore entirely within his rights to make war on Philip (or, as he for the moment preferred, on Philip's "bad advisor" Alba). This was important in a diplomatic context as it legitimised Orange's efforts to hire mercenaries in the principalities of his German "colleagues," and enabled him to issue letters of marque

A letter of marque and reprisal () was a government license in the Age of Sail that authorized a private person, known as a privateer or corsair, to attack and capture vessels of a foreign state at war with the issuer, licensing internationa ...

to the many Calvinist seamen who had embarked on a career of piracy from economic desperation. Such letters elevated the latter, the so-called Sea Beggars, to the status of privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s, which enabled the authorities in neutral countries, like the England of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

, to accommodate them without legal embarrassment. Orange's temporary abode in Dillenburg

Dillenburg, officially Oranienstadt Dillenburg, is a town in Hesse's Gießen region in Germany. The town was formerly the seat of the old Dillkreis district, which is now part of the Lahn-Dill-Kreis.

The town lies on the German- Dutch holiday roa ...

therefore became the command center for plans to invade the Netherlands from several directions at once. Orange went into exile in his ancestral castle in Dillenburg, which became the centre for plans to invade the Netherlands.

Other nobles decided to stay, but remained critical of the royal government. Philippe III de Croÿ, the Duke of Aarschot, had been Orange's rival before Alba's 1567 arrival, and he became the ''de facto'' leader of his majesty's loyal opposition in the years thereafter (1567–1576). It was not until the Spanish Fury that their interests firmly coincided, and Orange and Aarschot became allies in their joint rebellion against the king.

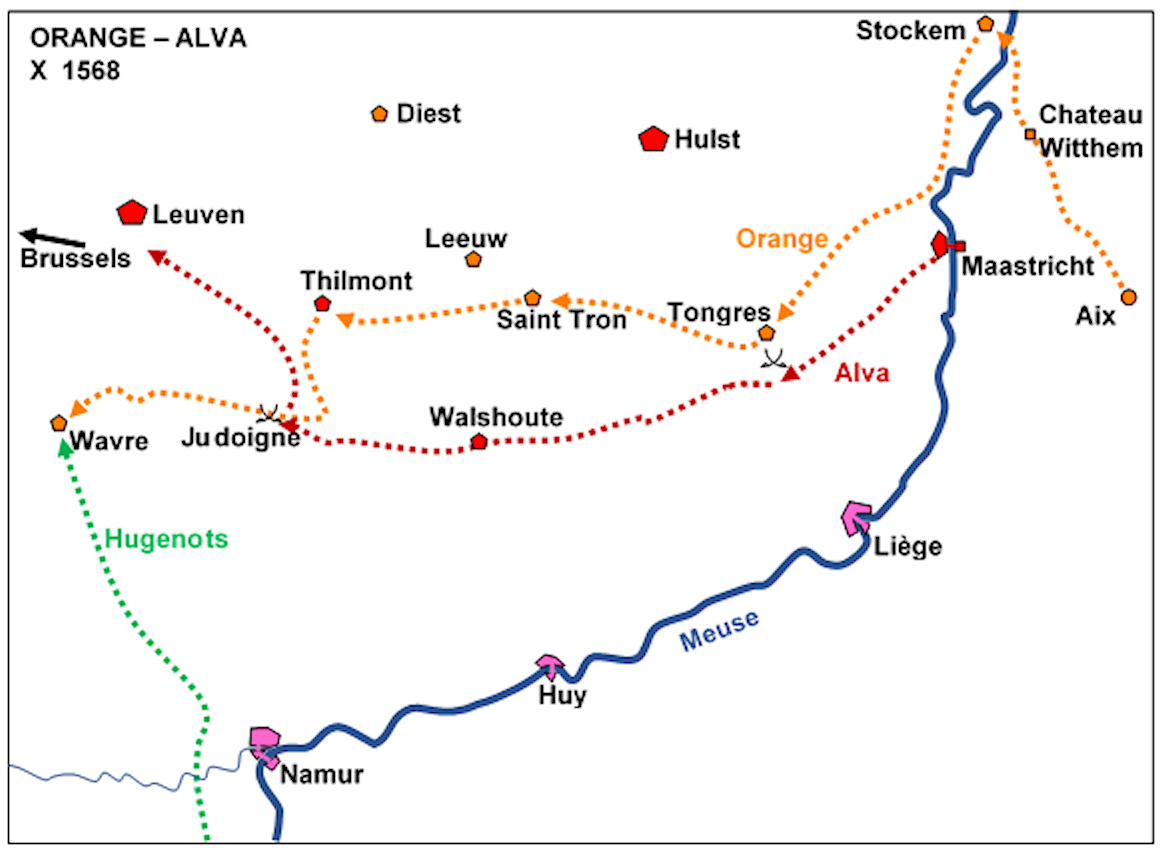

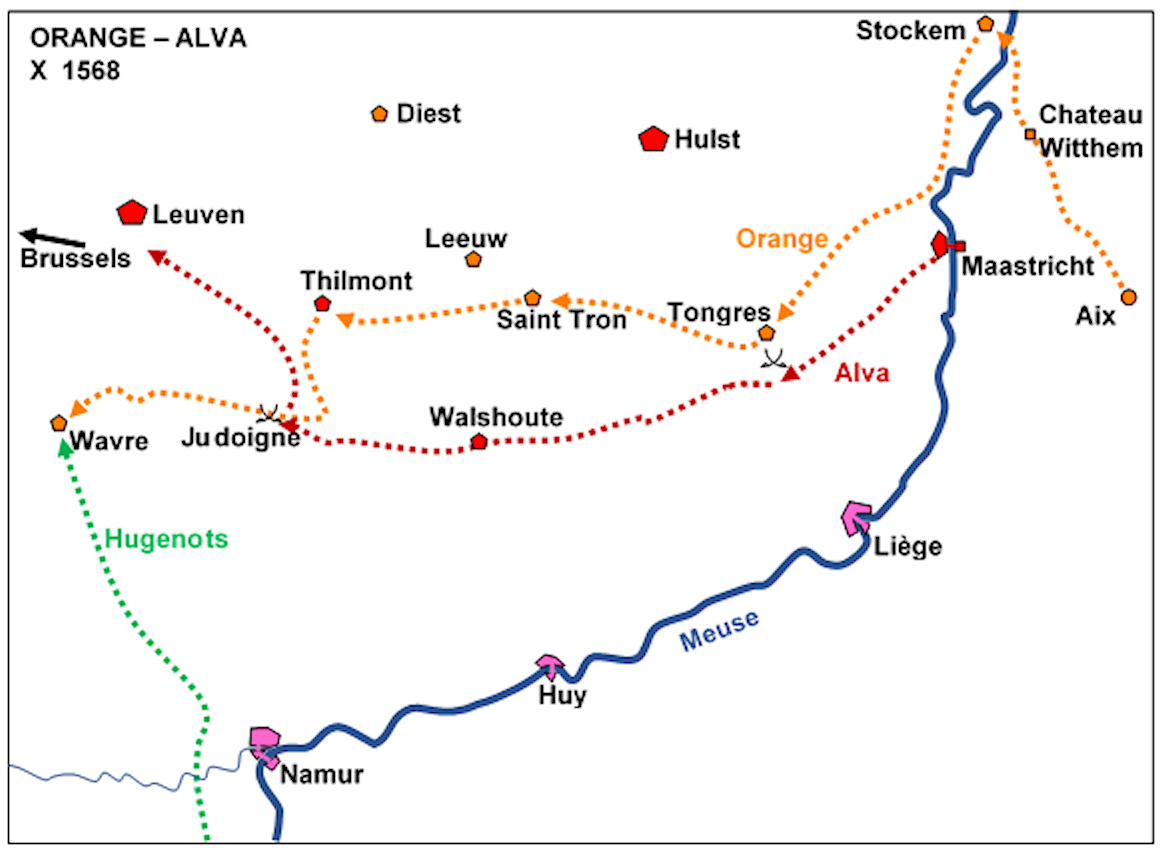

Orange's first invasion (April–November 1568)

Louis of Nassau

Louis of Nassau (Dutch: Lodewijk van Nassau, 10 January 1538 – 14 April 1574) was a Dutch nobleman, the third son of William I, Count of Nassau-Siegen and Juliana of Stolberg, and the younger brother of Prince William the Silent, William ...

, Orange's brother, crossed into Groningen

Groningen ( , ; ; or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen (province), Groningen province in the Netherlands. Dubbed the "capital of the north", Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of ...

from East Friesland with a mercenary army of ''Landsknecht

The (singular: , ), also rendered as Landsknechts or Lansquenets, were German mercenaries used in pike and shot formations during the early modern period. Consisting predominantly of pikemen and supporting foot soldiers, their front line was ...

en'', and defeated a small royalist force at Heiligerlee on 23 May 1568. Two months later, Louis's mercenary forces were smashed at the Battle of Jemmingen. Shortly thereafter, a Sea Beggars naval squadron defeated a royalist fleet in a naval battle on the Ems. However, a Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

army invading Artois

Artois ( , ; ; Picard: ''Artoé;'' English adjective: ''Artesian'') is a region of northern France. Its territory covers an area of about 4,000 km2 and it has a population of about one million. Its principal cities include Arras (Dutch: ...

was pushed back into France and then annihilated by the forces of Charles IX of France

Charles IX (Charles Maximilien; 27 June 1550 – 30 May 1574) was List of French monarchs, King of France from 1560 until his death in 1574. He ascended the French throne upon the death of his brother Francis II of France, Francis II in 1560, an ...

in June. Orange marched into Brabant, but with money running out he could not maintain his mercenary army and had to retreat.

1569–1571

Philip was suffering from the high cost of his war against theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, and ordered Alba to fund his armies from taxes levied in the Netherlands. Alba went against the States General of the Netherlands

The States General of the Netherlands ( ) is the Parliamentary sovereignty, supreme Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of the Netherlands consisting of the Senate (Netherlands), Senate () and the House of Representatives (Netherlands), House of R ...

by imposing sales taxes by decree on 31 July 1571. Alba commanded local governments to collect the unpopular taxes, which alienated even loyal lower governments from the central government.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * paperback * * 16th century in Spain 16th-century conflicts Wars involving Spain Wars involving the Netherlands {{DEFAULTSORT:Eighty Years' War, 1566-1572