Edward, the Black Prince on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward of Woodstock (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), known as the Black Prince, was the eldest son and

Edward, Prince of Wales, sailed with King Edward III on 11 July 1346, and as soon as he landed at La Hougue he received knighthood from his father in the local church of Quettehou. Then he "made a right good beginning", for he rode through the Cotentin, burning and ravaging as he went. Edward distinguished himself at the taking of Caen and in the Battle of Blanchetaque with the force under Sir Godemar I du Fay, which endeavoured to prevent the English army from crossing the

Edward, Prince of Wales, sailed with King Edward III on 11 July 1346, and as soon as he landed at La Hougue he received knighthood from his father in the local church of Quettehou. Then he "made a right good beginning", for he rode through the Cotentin, burning and ravaging as he went. Edward distinguished himself at the taking of Caen and in the Battle of Blanchetaque with the force under Sir Godemar I du Fay, which endeavoured to prevent the English army from crossing the  Edward was present at the siege of Calais (1346–1347), and after the surrender of the town harried and burned the country for around, and he brought much booty back with him. He returned to England with his father on 12 October 1347, took part in the jousts and other festivities of the court, and was invested by the king with the new

Edward was present at the siege of Calais (1346–1347), and after the surrender of the town harried and burned the country for around, and he brought much booty back with him. He returned to England with his father on 12 October 1347, took part in the jousts and other festivities of the court, and was invested by the king with the new

On 6 July 1356 Edward set out on another expedition, undertaken with the intention of passing through France to Normandy and there giving aid to his father's Norman allies, the party headed by the king of Navarre and Geoffrey d'Harcourt. In Normandy he expected to be met by his father. He crossed the

On 6 July 1356 Edward set out on another expedition, undertaken with the intention of passing through France to Normandy and there giving aid to his father's Norman allies, the party headed by the king of Navarre and Geoffrey d'Harcourt. In Normandy he expected to be met by his father. He crossed the

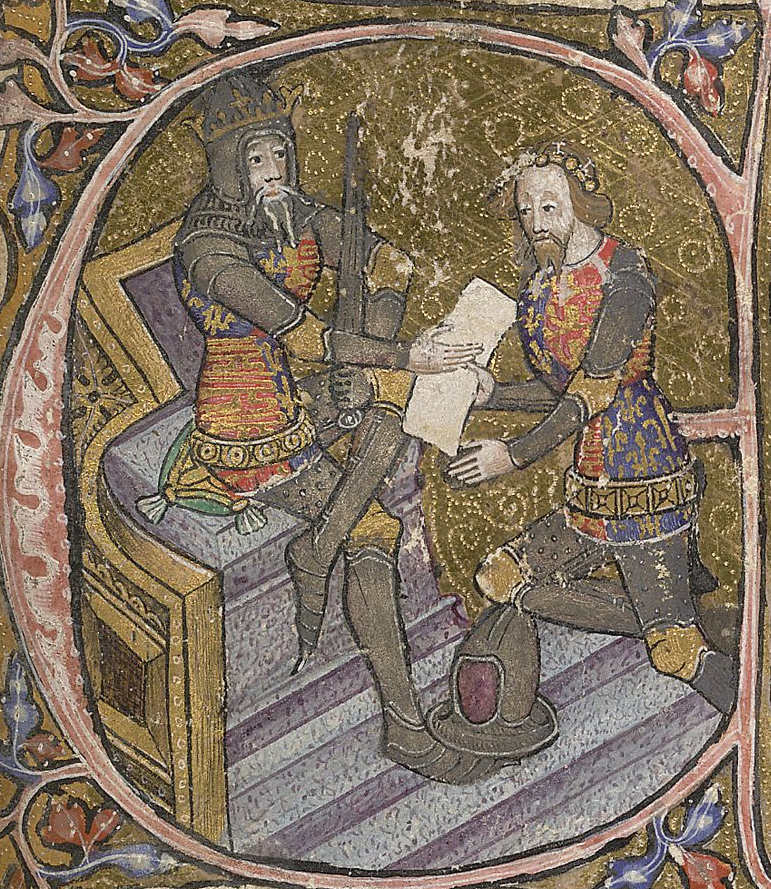

On 19 July 1362 Edward III granted Prince Edward all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony, to be held as a principality by liege homage on payment of an ounce of gold each year, together with the title of Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony. During the rest of the year he was occupied in preparing for his departure to his new principality, and after Christmas he received the king and his court at Berkhamsted, took leave of his father and mother, and in the following February sailed with Joan and all his household for Gascony, landing at

On 19 July 1362 Edward III granted Prince Edward all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony, to be held as a principality by liege homage on payment of an ounce of gold each year, together with the title of Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony. During the rest of the year he was occupied in preparing for his departure to his new principality, and after Christmas he received the king and his court at Berkhamsted, took leave of his father and mother, and in the following February sailed with Joan and all his household for Gascony, landing at

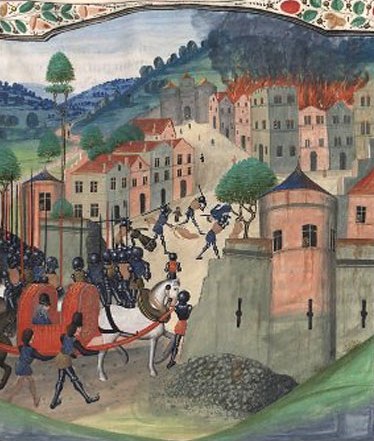

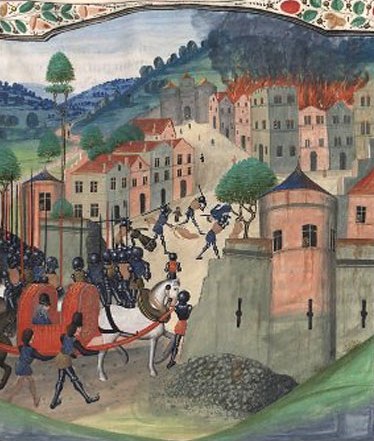

When Prince Edward heard of the surrender of Limoges to the French, he swore "by the soul of his father" that he would have the place again and would make the inhabitants pay dearly for their treachery. He set out from Cognac with an army of about 4,000 men. Due to his sickness he was unable to mount his horse, and was carried in a litter. During the siege of Limoges, the prince was determined to take the town and ordered the undermining of its walls. On 19 September, his miners succeeded in demolishing a large piece of wall which filled the ditches with its ruins. The town was then stormed, with the inevitable destruction and loss of life. cites ''Froissart'', i. 620, Buchon; ''Cont''. Murimuth, p. 209.

The Victorian historian William Hunt, author of Prince Edward's biography in the ''

When Prince Edward heard of the surrender of Limoges to the French, he swore "by the soul of his father" that he would have the place again and would make the inhabitants pay dearly for their treachery. He set out from Cognac with an army of about 4,000 men. Due to his sickness he was unable to mount his horse, and was carried in a litter. During the siege of Limoges, the prince was determined to take the town and ordered the undermining of its walls. On 19 September, his miners succeeded in demolishing a large piece of wall which filled the ditches with its ruins. The town was then stormed, with the inevitable destruction and loss of life. cites ''Froissart'', i. 620, Buchon; ''Cont''. Murimuth, p. 209.

The Victorian historian William Hunt, author of Prince Edward's biography in the ''

Edward is often referred to as the "Black Prince". The first known source to use this

Edward is often referred to as the "Black Prince". The first known source to use this

Welsh title: Owain Glyndwr (1400/15) {{DEFAULTSORT:Edward, The Black Prince 1330 births 1376 deaths 14th-century English nobility 14th-century peers of France Basque history Burials at Canterbury Cathedral Children of Edward III of England Deaths from dysentery Dukes of Cornwall English heirs apparent who never acceded High sheriffs of Cornwall House of Plantagenet Garter Knights appointed by Edward III Knights Bachelor Peers created by Edward III People from Wallingford, Oxfordshire People from Woodstock, Oxfordshire People of the Hundred Years' War Princes of Wales Sons of kings English princes

heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

of King Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II, succeeded to the throne instead. Edward nevertheless earned distinction as one of the most successful English commanders during the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

, being regarded by his English contemporaries as a model of chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct that developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of ...

and one of the greatest knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

of his age. Edward was made Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall () is a title in the Peerage of England, traditionally held by the eldest son of the reigning Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British monarch, previously the English monarch. The Duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created i ...

, the first English dukedom, in 1337. He was guardian of the kingdom in his father's absence in 1338, 1340, and 1342. He was created Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

in 1343 and knighted by his father at La Hougue in 1346.

In 1346, Prince Edward commanded the vanguard at the Battle of Crécy

The Battle of Crécy took place on 26 August 1346 in northern France between a French army commanded by King PhilipVI and an English army led by King Edward III. The French attacked the English while they were traversing northern France ...

, his father intentionally leaving him to win the battle. He took part in Edward III's 1349 Calais expedition. In 1355, he was appointed the king's lieutenant in Gascony and ordered to lead an army into Aquitaine

Aquitaine (, ; ; ; ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne (), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former Regions of France, administrative region. Since 1 January 2016 it has been part of the administ ...

on a chevauchée, during which he pillaged Avignonet and Castelnaudary, sacked Carcassonne

Carcassonne is a French defensive wall, fortified city in the Departments of France, department of Aude, Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania. It is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the department.

...

, and plundered Narbonne

Narbonne ( , , ; ; ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and was ...

. In 1356, on another chevauchée, he ravaged Auvergne, Limousin

Limousin (; ) is a former administrative region of southwest-central France. Named after the old province of Limousin, the administrative region was founded in 1960. It comprised three departments: Corrèze, Creuse, and Haute-Vienne. On 1 Jan ...

, and Berry

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone or pit although many pips or seeds may be present. Common examples of berries in the cul ...

but failed to take Bourges

Bourges ( ; ; ''Borges'' in Berrichon) is a commune in central France on the river Yèvre (Cher), Yèvre. It is the capital of the Departments of France, department of Cher (department), Cher, and also was the capital city of the former provin ...

. He offered terms of peace to King John II of France

John II (; 26 April 1319 – 8 April 1364), called John the Good (French: ''Jean le Bon''), was King of France from 1350 until his death in 1364. When he came to power, France faced several disasters: the Black Death, which killed between a thir ...

, who had outflanked him near Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

, but Edward refused to surrender himself. This led to the Battle of Poitiers

The Battle of Poitiers was fought on 19September 1356 between a Kingdom of France, French army commanded by King John II of France, King JohnII and an Kingdom of England, Anglo-Gascony, Gascon force under Edward the Black Prince, Edward, the ...

, where his army routed the French and took King John prisoner.

In 1360, he negotiated the Treaty of Brétigny. He was created Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

in 1362, but his suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

was not recognised by the lord of Albret or other Gascon nobles. He was directed by his father to forbid the marauding raids of the English and Gascon free companies in 1364. He entered into an agreement with Kings Peter of Castile

Peter (; 30 August 133423 March 1369), called Peter the Cruel () or the Just (), was King of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. Peter was the last ruler of the main branch of the House of Ivrea. He was excommunicated by Pope Urban V for h ...

and Charles II of Navarre

Charles II (, , , 10 October 1332 – 1 January 1387), known as the Bad, was King of Navarre beginning in 1349, as well as Count of Évreux beginning in 1343, holding both titles until his death in 1387.

Besides the Kingdom of Navarre nestled in ...

, by which Peter covenanted to mortgage Castro Urdiales and the province of Biscay to him as security for a loan; in 1366 a passage was secured through Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

. In 1367, he received a letter of defiance from Henry of Trastámara, Peter's half-brother and rival. The same year, after an obstinate conflict, he defeated Henry at the Battle of Nájera

The Battle of Nájera, also known as the Battle of Navarrete, was fought on 3 April 1367 to the northeast of Nájera, in the province of La Rioja, Castile. It was an episode of the first Castilian Civil War which confronted King Peter of Ca ...

. However, after a wait of several months during which he failed to obtain either the province of Biscay or liquidation of the debt from Don Pedro, he returned to Aquitaine. Edward persuaded the estates of Aquitaine to allow him a hearth tax

A hearth tax was a property tax in certain countries during the medieval and early modern period, levied on each hearth, thus by proxy on wealth. It was calculated based on the number of hearths, or fireplaces, within a municipal area and is con ...

of ten sous

The Sous region (also spelt Sus, Suss, Souss or Sousse) (, ) is a historical, cultural and geographical region of Morocco, which constitutes part of the region administration of Souss-Massa and Guelmim-Oued Noun. The region is known for the en ...

for five years in 1368, thereby alienating the lord of Albret and other nobles.

Prince Edward returned to England in 1371 and resigned the principality of Aquitaine and Gascony in 1372. He led the Commons in their attack upon the Lancastrian administration in 1376. He died in 1376 of dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

and was buried in Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christianity, Ch ...

, where his surcoat

A surcoat or surcote is an outer garment that was commonly worn in the Middle Ages by soldiers. It was worn over armor to show insignia and help identify what side the soldier was on. In the battlefield the surcoat was also helpful with keeping ...

, helmet, shield, and gauntlets are still preserved.

Early life (1330–1343)

Edward—the eldest son ofEdward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, Lord of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland (), sometimes referred to retrospectively as Anglo-Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of Kingdom of England, England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Normans in Ireland, Anglo ...

and ruler of Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

, and Queen Philippa—was born at Woodstock

The Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held from August 15 to 18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. Billed as "a ...

, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire ( ; abbreviated ''Oxon'') is a ceremonial county in South East England. The county is bordered by Northamptonshire and Warwickshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the east, Berkshire to the south, and Wiltshire and Glouceste ...

, on 15 June 1330. On 10 September Edward III allowed five hundred mark

Mark may refer to:

In the Bible

* Mark the Evangelist (5–68), traditionally ascribed author of the Gospel of Mark

* Gospel of Mark, one of the four canonical gospels and one of the three synoptic gospels

Currencies

* Mark (currency), a currenc ...

s per year from the profits of the county of Chester

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shropshire to the south; to the west ...

for his son's maintenance; on 25 February 1331, the whole of these profits were assigned to the queen for maintaining Edward and the king's sister Eleanor. In July 1331 the king proposed to marry Edward to a daughter of Philip VI of France

Philip VI (; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (), the Catholic (''le Catholique'') and of Valois (''de Valois''), was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 1328 until his death in 1350. Philip's reign w ...

.

Edward III had been in conflict with the French over English lands in France and also the kingship of France; Edward III's mother and the Prince's grandmother, Queen Isabella of France

Isabella of France ( – 22 August 1358), sometimes described as the She-Wolf of France (), was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the wife of Edward II of England, King Edward II, and ''de facto'' regent of England from 1327 ...

was a daughter of King Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. Jure uxoris, By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip&n ...

, thus placing her son in line for the throne of France. Relations between England and France quickly deteriorated when Philip threatened to confiscate his lands in France, beginning the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

.

On 18 March 1333, Edward was invested with the earldom and county of Chester, and in the parliament of 9 February 1337 he was created duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall () is a title in the Peerage of England, traditionally held by the eldest son of the reigning Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British monarch, previously the English monarch. The Duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created i ...

and received the duchy

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a country, territory, fiefdom, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or Queen regnant, queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important differe ...

by charter dated 17 March. This is the earliest instance of the creation of a duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobi ...

in England. By the terms of the charter the duchy was to be held by Edward and the eldest sons of kings of England. His tutor was Dr. Walter Burley of Merton College, Oxford

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 126 ...

. His revenues were placed at the disposal of his mother in March 1334 for the expenses she incurred in bringing up him and his two sisters, Isabella and Joan. Rumours of an impending French invasion led the king in August 1335 to order that he and his household should remove to Nottingham Castle

Nottingham Castle is a Stuart Restoration-era ducal mansion in Nottingham, England, built on the site of a Normans, Norman castle built starting in 1068, and added to extensively through the medieval period, when it was an important royal fortr ...

as a place of safety.

When two cardinals came to England at the end of 1337 to make peace between Edward III and Philip VI, Edward reportedly met the cardinals outside the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

and, in company with many nobles, conducted them to Edward III. On 11 July 1338 his father, who was on the point of leaving England for Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

, appointed him guardian of the kingdom during his absence, and he was appointed to the same office on 27 May 1340 and 6 October 1342; he was, of course, too young to take any save a nominal part in the administration, which was carried on by the council. To attach John III, Duke of Brabant

John III (; 1300 – 5 December 1355) was Duke of Brabant, Duke of Lothier, Lothier (1312–1355) and List of rulers of Limburg, Limburg (1312–1347 then 1349–1355), the last Brabant male to rule them.

Biography

John was the son of John II, ...

, to his cause, the king in 1339 proposed a marriage between Edward and John's daughter Margaret, and in the spring of 1345 wrote urgently to Pope Clement VI

Pope Clement VI (; 1291 – 6 December 1352), born Pierre Roger, was head of the Catholic Church from 7 May 1342 to his death, in December 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope. Clement reigned during the first visitation of the Black Death (1 ...

for a dispensation for the marriage.

On 12 May 1343, Edward III created Edward Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

in a parliament held at Westminster, investing Edward with a circlet, gold ring, and silver rod. Edward accompanied his father to Sluys on 3 July 1345, and the king tried to persuade the burgomaster

Burgomaster (alternatively spelled burgermeister, ) is the English form of various terms in or derived from Germanic languages for the chief magistrate or executive of a city or town. The name in English was derived from the Dutch .

In so ...

s of Ghent

Ghent ( ; ; historically known as ''Gaunt'' in English) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the Provinces of Belgium, province ...

, Bruges

Bruges ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the province of West Flanders, in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is in the northwest of the country, and is the sixth most populous city in the country.

The area of the whole city amoun ...

and Ypres

Ypres ( ; ; ; ; ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality comprises the city of Ypres/Ieper ...

to accept his son as their lord, but the murder of Jacob van Artevelde put an end to this project. Both in September 1345 and in April 1346, Edward was called on to furnish troops from his principality and earldom for the impending campaign in France, and as he incurred heavy debts in the king's service, his father authorised him to make his will and provided that, in case he fell in the war, his executors should have all his revenue for a year.

Early campaigns (1346–53)

Battle of Crécy

Edward, Prince of Wales, sailed with King Edward III on 11 July 1346, and as soon as he landed at La Hougue he received knighthood from his father in the local church of Quettehou. Then he "made a right good beginning", for he rode through the Cotentin, burning and ravaging as he went. Edward distinguished himself at the taking of Caen and in the Battle of Blanchetaque with the force under Sir Godemar I du Fay, which endeavoured to prevent the English army from crossing the

Edward, Prince of Wales, sailed with King Edward III on 11 July 1346, and as soon as he landed at La Hougue he received knighthood from his father in the local church of Quettehou. Then he "made a right good beginning", for he rode through the Cotentin, burning and ravaging as he went. Edward distinguished himself at the taking of Caen and in the Battle of Blanchetaque with the force under Sir Godemar I du Fay, which endeavoured to prevent the English army from crossing the Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

* Somme, Queensland, Australia

* Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), ...

. cites Baron Seymour de Constant, ''Bataille de Crécy'', ed, 1846; Louandre, ''Histoire d'Abbeville; Archæologia'', xxviii. 171.

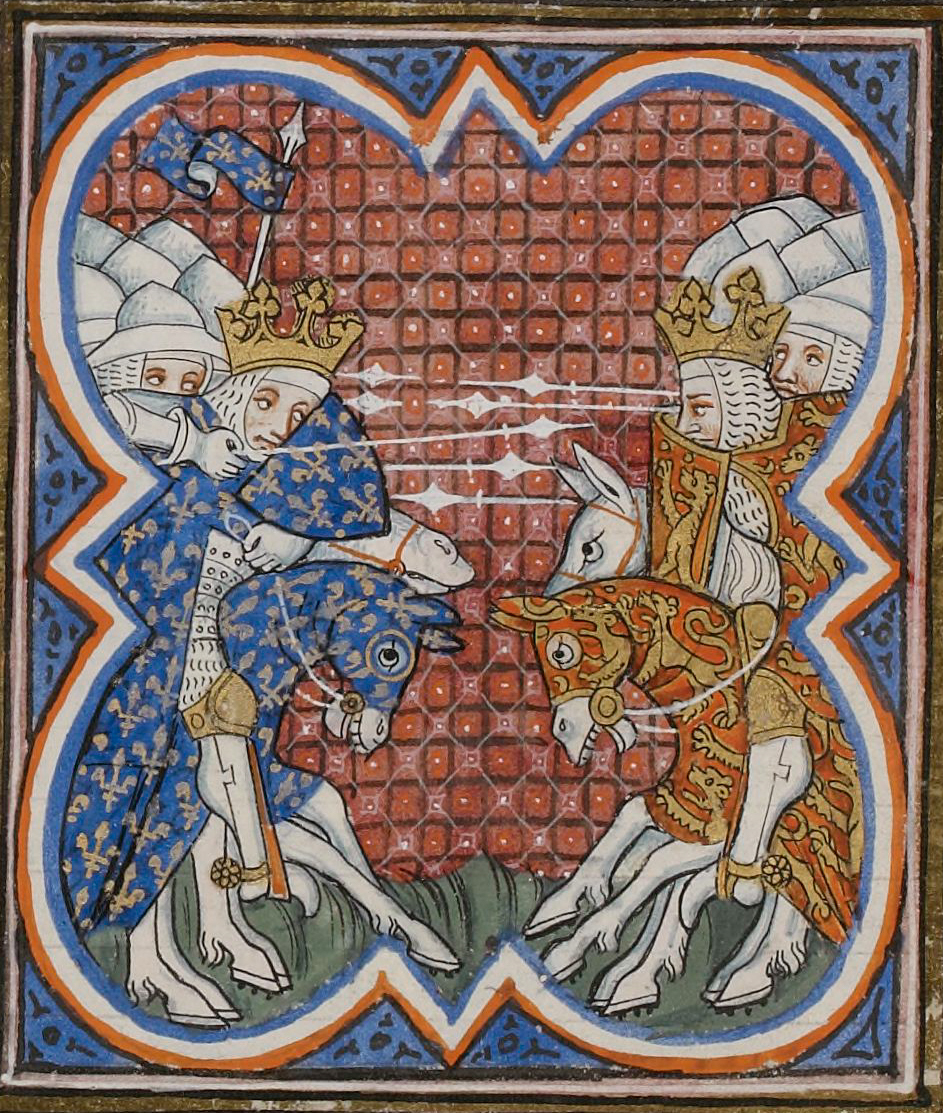

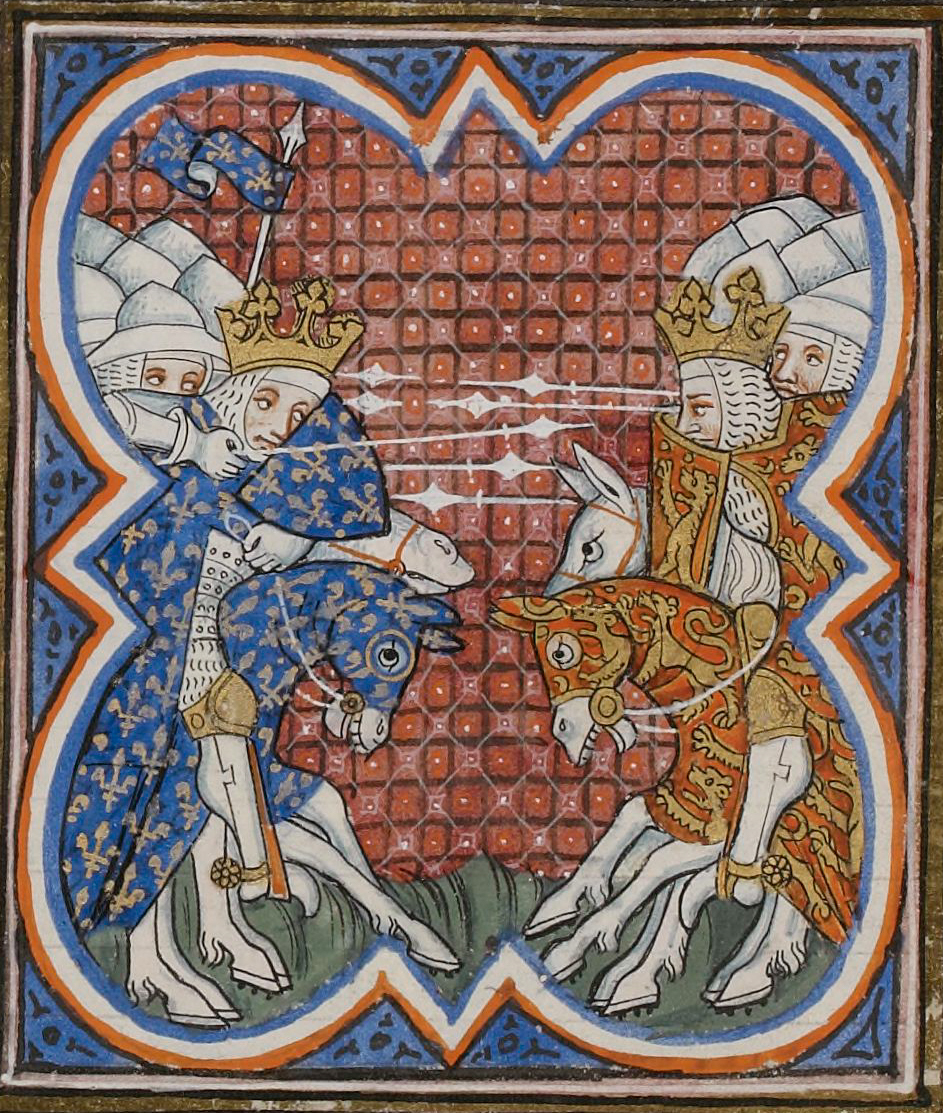

Early on 26 August 1346, before the start of the Battle of Crécy

The Battle of Crécy took place on 26 August 1346 in northern France between a French army commanded by King PhilipVI and an English army led by King Edward III. The French attacked the English while they were traversing northern France ...

, Edward received the sacrament with his father at Crécy, and took the command of the right, or van, of the army with the earls of Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined wit ...

and Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, Sir Geoffroy d'Harcourt, Sir John Chandos

Sir John Chandos, Viscount of Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte, Saint-Sauveur in the Cotentin Peninsula, Cotentin, Constable of Aquitaine, Seneschal of Count of Poitiers, Poitou, (c. 1320 – 31 December 1369) was a medieval English knight who haile ...

, and other leaders, and at the head of 800 men-at-arms, 2,000 archers, and 1,000 Welsh foot soldiers, though the numbers are by no means trustworthy. When the Genoese bowmen were discomfited and the front line of the French was in some disorder, Edward apparently left his position to attack their second line. At this moment, however, the Count of Alençon

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility.L. G. Pine, Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty'' ...

charged his division with such fury that Edward was in great danger, and the leaders who commanded with him sent a messenger to tell Edward III that he was in great straits and to beg for assistance. When Edward III learned that his son was not wounded, he responded that he would send no help, for he wished to give Edward the opportunity to "win his spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to ba ...

s" (he was in fact already a knight), and to allow him and those who had charge of him the honour of the victory. Edward was thrown to the ground and was rescued by Sir Richard Fitz-Simon, his standard-bearer, who threw down the banner, stood over his body, and beat back his assailants while he regained his feet. Harcourt sent to Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and it is used (along with the earldom of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title ...

for help, and he forced back the French, who had probably by this time advanced to the rising ground of the English position.

A flank attack on the side of Wadicourt was next made by the Counts of Alençon

Alençon (, , ; ) is a commune in Normandy, France, and the capital of the Orne department. It is situated between Paris and Rennes (about west of Paris) and a little over north of Le Mans. Alençon belongs to the intercommunality of Alen� ...

and Ponthieu

Ponthieu (; ; ) was one of six feudal counties that eventually merged to become part of the Province of Picardy, in northern France.Dunbabin.France in the Making. Ch.4. The Principalities 888-987 Its chief town is Abbeville.

History

Ponthieu p ...

, but the English were strongly entrenched there, and the French were unable to penetrate the defences and lost the Duke of Lorraine

The kings and dukes of Lorraine have held different posts under different governments over different regions, since its creation as the kingdom of Lotharingia by the Treaty of Prüm, in 855. The first rulers of the newly established region were ...

and the Counts of Alençon

Alençon (, , ; ) is a commune in Normandy, France, and the capital of the Orne department. It is situated between Paris and Rennes (about west of Paris) and a little over north of Le Mans. Alençon belongs to the intercommunality of Alen� ...

and Blois

Blois ( ; ) is a commune and the capital city of Loir-et-Cher Departments of France, department, in Centre-Val de Loire, France, on the banks of the lower Loire river between Orléans and Tours.

With 45,898 inhabitants by 2019, Blois is the mos ...

. The two front lines of their army were utterly broken before King Philip's division engaged. Then Edward III appears to have advanced at the head of the reserve, and the rout soon became complete. When Edward III met his son after the battle was over, he embraced him and declared that he had acquitted himself loyally, and Edward bowed low and did reverence to his father. The next day he joined the king in paying funeral honours to King John of Bohemia

John of Bohemia, also called the Blind or of Luxembourg (; ; ; 10 August 1296 – 26 August 1346), was the Count of Luxembourg from 1313 and King of Bohemia from 1310 and titular King of Poland. He is well known for having died while fighting ...

.

Edward was present at the siege of Calais (1346–1347), and after the surrender of the town harried and burned the country for around, and he brought much booty back with him. He returned to England with his father on 12 October 1347, took part in the jousts and other festivities of the court, and was invested by the king with the new

Edward was present at the siege of Calais (1346–1347), and after the surrender of the town harried and burned the country for around, and he brought much booty back with him. He returned to England with his father on 12 October 1347, took part in the jousts and other festivities of the court, and was invested by the king with the new Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

in 1348.

Siege of Calais and Battle of Winchelsea

Prince Edward shared in the king's expedition to Calais in the last days of 1349, came to the rescue of his father, and when the combat was over and the king and his prisoners sat down to feast, he and the other English knights served the king and his guests at the first course and then sat down for the second course at another table. When the king embarked atWinchelsea

Winchelsea () is a town in the county of East Sussex, England, located between the High Weald and the Romney Marsh, approximately south west of Rye and north east of Hastings. The current town, which was founded in 1288, replaced an earli ...

on 28 August 1350 to intercept the fleet of La Cerda, the Prince sailed with him, though in another ship, and in company with his brother, the young John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399), was an English royal prince, military leader and statesman. He was the fourth son (third surviving) of King Edward III of England, and the father of King Henry IV. Because ...

, Earl of Richmond

The now-extinct title of Earl of Richmond was created many times in the Peerage of Peerage of England, England. The earldom of Richmond, North Yorkshire, Richmond was initially held by various Breton people, Breton nobles; sometimes the holde ...

. During the Battle of Winchelsea his ship was grappled by a large Spanish ship and was so full of leaks that it was likely to sink, and though he and his knights attacked the enemy manfully, they were unable to take her. Henry of Grosmont, Earl of Lancaster, came to his rescue and attacked the Spaniard on the other side; she was soon taken, her crew were thrown into the sea, and as the Prince and his men got on board her their own ship foundered.

Cheshire expedition

In 1353 some disturbances seem to have broken out inCheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shrop ...

, for the Prince as Earl of Chester

The Earldom of Chester () was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, ...

marched with Henry of Grosmont, now Duke of Lancaster

The dukedom of Lancaster is a former Peerage of England, English peerage, created three times in the Middle Ages, which finally merged in the Crown when Henry V of England, Henry V succeeded to the throne in 1413. Despite the extinction of the ...

, to the neighbourhood of Chester

Chester is a cathedral city in Cheshire, England, on the River Dee, Wales, River Dee, close to the England–Wales border. With a built-up area population of 92,760 in 2021, it is the most populous settlement in the borough of Cheshire West an ...

to protect the justices, who were holding an assize there. The men of the earldom offered to pay him a heavy fine to bring the assize to an end, but when they thought they had arranged matters the justices opened an inquisition of trailbaston, took a large sum of money from them, and seized many houses and much land into the prince's, their earl's, hands. On his return from Chester the prince is said to have passed by the Abbey of Dieulacres in Staffordshire, to have seen a fine church which his great-grandfather, Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

, had built there, and to have granted five hundred marks, a tenth of the sum he had taken from his earldom, towards its completion; the abbey was almost certainly not Dieulacres but Vale Royal

Vale Royal was, from 1974 to 2009, a Non-metropolitan district, local government district with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Cheshire, England. It contained the towns of Northwich, Winsford and Frodsham.

History

The ...

.

Further campaigns (1355–64)

Aquitaine

When Edward III determined to renew the war with France in 1355, he ordered Edward to lead an army intoAquitaine

Aquitaine (, ; ; ; ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne (), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former Regions of France, administrative region. Since 1 January 2016 it has been part of the administ ...

while he, as his plan was, acted with the king of Navarre in Normandy, and the Duke of Lancaster upheld the cause of John of Montfort in Brittany. Edward's expedition was made in accordance with the request of some of the Gascon lords who were anxious for plunder. On 10 July the king appointed him his lieutenant in Gascony and gave him powers to act in his stead and to receive homages. Edward left London for Plymouth on 30 June, was detained there by contrary winds, and set sail on 8 September with about 300 ships, in company with four earls (Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, William Ufford, Earl of Suffolk, William Montagu, Earl of Salisbury, and John Vere, Earl of Oxford) and in command of 1,000 men-at-arms, 2,000 archers, and a large body of Welsh foot soldiers. At Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

the Gascon lords received him with much rejoicing. It was decided to make a short campaign before the winter, and on 10 October he set out with 1,500 lances, 2,000 archers, and 3,000 light foot. Whatever scheme of operations the king may have formed during the summer, this expedition of Edward was purely a piece of marauding. After grievously harrying the counties of Juliac, Armagnac

Armagnac (, ) is a distinctive kind of brandy produced in the Armagnac (region), Armagnac region in Gascony, southwest France. It is distilled from wine usually made from a blend of grapes including Baco 22A, Colombard, Folle blanche and Ugni ...

, Astarac, and part of Comminges

The Comminges (; Occitan language, Occitan/Gascon language, Gascon: ''Comenge'') is an ancient region of southern France in the foothills of the Pyrenees, corresponding approximately to the arrondissement of Saint-Gaudens in the departments of Fran ...

, he crossed the Garonne

The Garonne ( , ; Catalan language, Catalan, Basque language, Basque and , ;

or ) is a river that flows in southwest France and northern Spain. It flows from the central Spanish Pyrenees to the Gironde estuary at the French port of Bordeaux � ...

at Sainte-Marie a little above Toulouse

Toulouse (, ; ; ) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Haute-Garonne department and of the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region. The city is on the banks of the Garonne, River Garonne, from ...

, which was occupied by John I, Count of Armagnac

John I of Armagnac (French: Jean d’Armagnac; 1311–1373), son of Bernard VI and Cecilia Rodez, was Count of Armagnac from 1319 to 1373. In addition to Armagnac he controlled territory in Quercy, Rouergue and Gévaudan. He was the count who ...

, and a considerable force. The count refused to allow the garrison to make a sally, and Edward passed on into the Lauragais. His troops stormed and burnt Montgiscard, where many men, women, and children were ill-treated and slain, and took and pillaged Avignonet and Castelnaudary. The country was "very rich and fertile" according to Edward, and the people "good, simple, and ignorant of war", so the prince took great spoil, especially of carpets, draperies, and jewels, for "the robbers" spared nothing, and the Gascons who marched with him were especially greedy. The only castle to resist the English forces was Montgey. Its châtelain

Châtelain was originally the French title for the keeper of a castle.Abraham Rees Ebers, "CASTELLAIN", in: The Cyclopædia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature' (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1819), vol. 6.

H ...

e defended its walls by pouring beehives onto the attackers, who fled in panic.

Carcassonne

Carcassonne is a French defensive wall, fortified city in the Departments of France, department of Aude, Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania. It is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the department.

...

was taken and sacked, but Edward did not take the citadel which was strongly situated and fortified. Ourmes (or Homps, near Narbonne

Narbonne ( , , ; ; ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and was ...

) and Trèbes bought off his army. He plundered Narbonne

Narbonne ( , , ; ; ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and was ...

and thought of attacking the citadel, for he heard that there was much booty there, but he gave up the idea on finding that it was well defended. While there a messenger came to him from the papal court, urging him to allow negotiations for peace. He replied that he could do nothing without knowing his father's will. From Narbonne he turned to march back to Bordeaux. The Count of Armagnac tried to intercept him, but a small body of French having been defeated in a skirmish near Toulouse the rest of the army retreated into the city, and the prince returned in peace to Bordeaux, bringing back with him enormous spoils. The expedition lasted eight weeks, during which the prince only rested eleven days in all the places he visited, and without performing any feat of arms did the French king much mischief. During the next month, before 21 January 1356, the leaders under his command reduced five towns and seventeen castles.

Battle of Poitiers

On 6 July 1356 Edward set out on another expedition, undertaken with the intention of passing through France to Normandy and there giving aid to his father's Norman allies, the party headed by the king of Navarre and Geoffrey d'Harcourt. In Normandy he expected to be met by his father. He crossed the

On 6 July 1356 Edward set out on another expedition, undertaken with the intention of passing through France to Normandy and there giving aid to his father's Norman allies, the party headed by the king of Navarre and Geoffrey d'Harcourt. In Normandy he expected to be met by his father. He crossed the Dordogne

Dordogne ( , or ; ; ) is a large rural departments of France, department in south west France, with its Prefectures in France, prefecture in Périgueux. Located in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region roughly half-way between the Loire Valley and ...

at Bergerac on 4 August and rode through Auvergne, Limousin, and Berry, plundering and burning as he went until he came to Bourges

Bourges ( ; ; ''Borges'' in Berrichon) is a commune in central France on the river Yèvre (Cher), Yèvre. It is the capital of the Departments of France, department of Cher (department), Cher, and also was the capital city of the former provin ...

, where he burnt the suburbs but failed to take the city. He then turned westward and made an unsuccessful attack on Issoudun

Issoudun () is a commune in the Indre department, administrative region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is also referred to as ''Issoundun'', which is the ancient name.

Geography Location

Issoudun is a sub-prefecture, located in the eas ...

on 25–27 August. Meanwhile, King John II was gathering a large force at Chartres

Chartres () is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Eure-et-Loir Departments of France, department in the Centre-Val de Loire Regions of France, region in France. It is located about southwest of Paris. At the 2019 census, there were 1 ...

, from which he was able to defend the passages of the Loire

The Loire ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

It rises in the so ...

and was sending troops to the fortresses that seemed in danger of attack. From Issoudun Edward returned to his former line of march and took Vierzon

Vierzon () is a Communes of France, commune in the Cher (department), Cher departments of France, department, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

Geography

A medium-sized town by the banks of the river Cher (river), Cher with some light industry and a ...

. There he learnt that it would be impossible for him to cross the Loire or to form a junction with Lancaster, who was then in Brittany. Accordingly he determined to return to Bordeaux by way of Poitiers, and after putting to death most of the garrison of the castle of Vierzon he set out on 29 August towards Romorantin.

Some French knights who skirmished with the English advanced guard retreated into Romorantin, and when Prince Edward heard of this he said: "Let us go there; I should like to see them a little nearer". He inspected the fortress in person and sent his friend Chandos to summon the garrison to surrender. The place was defended by Boucicault and other leaders, and on their refusing his summons he assaulted it on 31 August. The siege lasted three days, and the prince, who was enraged at the death of one of his friends, declared that he would not leave the place untaken. Finally he set fire to the roofs of the fortress by using Greek fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon system used by the Byzantine Empire from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries. The recipe for Greek fire was a closely-guarded state secret; historians have variously speculated that it was based on saltp ...

, reduced it on 3 September.

On 5 September Edward proceeded to march through Berry. On 9 September King John II, who had gathered a large force, crossed the Loire at Blois and went in pursuit of them. When the king was at Loches

Loches (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

It is situated southeast of Tours by road, on the left bank of the river Indre (river), Indre.

History

Loch ...

on 12 September he had as many as 20,000 men-at-arms, and with these and his other forces he advanced to Chauvigny. On 16 and 17 September his army crossed the Vienne. Meanwhile, Edward was marching almost parallel to the French and at only a few miles distance from them. From 14 to 16 September he was at Châtellerault, and 17 September as he was marching towards Poitiers, some French men-at-arms skirmished with his advance guard, pursued them up to the main body of his army, and were all slain or taken prisoners. The French king had outstripped him, and his retreat was cut off by an army at least 50,000 strong, while Edward he about 7,500 men. Lancaster had endeavoured to come to his relief but had been stopped by the French at Pont-de-Cé.

When Prince Edward knew that the French army lay between him and Poitiers, he took up his position on some rising ground to the south-east of the city in the commune of Beauvoir and remained there that night. On 18 September Cardinal Hélie Talleyrand endeavoured to make peace. Edward was willing to come to terms and offered to give up all the towns and castles he had conquered, to set free all his prisoners, and not to serve against the king of France for seven years, besides, it is said, offering a payment of 100,000 francs. King John, however, was persuaded to demand that Edward and 100 of his knights should surrender themselves as prisoners, and to this Edward would not consent. The cardinal's negotiations lasted the whole day and were protracted in the interest of the French, for John was anxious to give time for further reinforcements to join his army. Considering the position of Edward, it seems probable that the French might have destroyed his army by hemming it in with a portion of their host, and so either starving it or forcing it to leave its strong station and fight in the open with the certainty of defeat. John made a mistake in allowing Edward respite during the negotiations, during which he employed his army in strengthening its position. The English front was well covered by vines and hedges; on its left and rear was the ravine of the Miausson river and a good deal of broken ground, and its right was flanked by the wood and abbey of Nouaillé. All through the day the army was busily engaged in digging trenches and making fences, so that it stood, as at Crécy, in a kind of entrenched camp.

Prince Edward drew up his men in three divisions, the first being commanded by the earls of Warwick and Suffolk, the second by himself, and the rear by Salisbury and Oxford. The French were drawn up in four divisions, one behind the other, and so lost much of the advantage of their superior numbers. In front of his first line and on either side of the narrow lane that led to his position the prince stationed his archers, who were well protected by hedges, and posted a kind of ambush of 300 men-at-arms and 300 mounted archers, who were to fall on the flank of the second battle of the enemy, commanded by the Dauphin, Charles, Duke of Normandy.

At daybreak on 19 September Prince Edward addressed his army, and the fight began. An attempt was made by 300 picked men-at-arms to ride through the narrow lane and force the English position, but they were shot down by the archers. A body of Germans and the first division of the army which followed were thrown into disorder; then the English force in ambush charged the second division on the flank, and as it began to waver the English men-at-arms mounted their horses, which they had kept near them, and charged down the hill. Edward kept Chandos by his side, and his friend did him good service in the fray. As they prepared to charge he cried: "John, get forward; you shall not see me turn my back this day, but I will be ever with the foremost", and then he shouted to his banner-bearer, "Banner, advance, in the name of God and St. George!". All the French except the advance guard fought on foot, and the division of the Duke of Normandy, already wavering, could not stand against the English charge and fled in disorder. The next division, under Philip, Duke of Orléans, also fled, though not so shamefully, but the rear under King John fought with much gallantry. The prince, "who had the courage of a lion, took great delight that day in the fight". The combat lasted until a little after 3 pm, and the French, who were utterly defeated, left 11,000 dead on the field, of whom 2,426 were men of gentle birth. Nearly 100 counts, barons, and banneret

A knight banneret, sometimes known simply as banneret, was a Middle Ages, medieval knight who led a company of troops during time of war under his own banner (which was square-shaped, in contrast to the tapering Heraldic flag#Standard, standar ...

s and 2,000 men-at-arms, besides many others, were made prisoners, and the king and his youngest son Philip were among those who were taken. The English losses were not large.

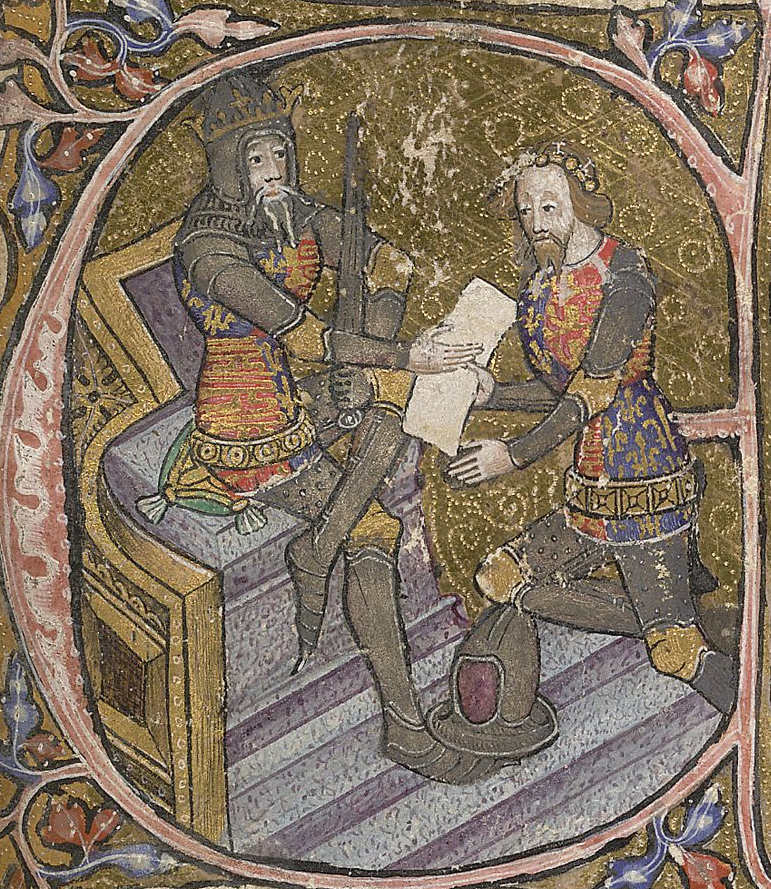

When King John was brought to him, Edward received him with respect, helped him to take off his armour, and entertained him and the greater part of the princes and barons who had been made prisoners at supper. He served at the king's table and would not sit down with him, declaring that "he was not worthy to sit at table with so great a king or so valiant a man", and speaking many comfortable words to him, for which the French praised him highly. The next day Edward continued his retreat on Bordeaux; he marched warily, but no one ventured to attack him.

At Bordeaux, which Prince Edward reached on 2 October, he was received with much rejoicing, and he and his men tarried there through the winter and wasted in festivities the immense spoil they had gathered. On 23 March 1357 Edward concluded a two years' truce, for he wished to return home. The Gascon lords were unwilling that King John should be carried off to England, and the prince gave them 100,000 crowns to silence their murmurs. He left the country under the government of four Gascon lords and arrived in England on 4 May, landing at Plymouth. When he entered London in triumph on 24 May with King John as his prisoner.

England, tournaments and debts

After his return to England, Prince Edward took part in the many festivals and tournaments of his father's court, and in May 1359 he and the king and other challengers held the lists at a joust proclaimed at London by the mayor and sheriffs, and, to the great delight of the citizens, the king appeared as the mayor and the prince as the senior sheriff. Festivities of this sort and the lavish gifts he bestowed on his friends brought him into debt, and on 27 August, when a new expedition into France was being prepared, the king granted that if he fell his executors should have his whole estate for four years for the payment of his debts.Reims campaign

In October 1359 Prince Edward sailed with his father to Calais and led a division of the army during the Reims campaign. At its close he took the principal part on the English side in negotiating the Treaty of Brétigny, and the preliminary truce arranged at Chartres on 7 May 1360 was drawn up by proctors acting in his name and the name of Charles, Duke of Normandy, the regent of France. He probably did not return to England until after his father, who landed atRye

Rye (''Secale cereale'') is a grass grown extensively as a grain, a cover crop and a forage crop. It is grown principally in an area from Eastern and Northern Europe into Russia. It is much more tolerant of cold weather and poor soil than o ...

on 18 May. On 9 July he and Henry, Duke of Lancaster, landed at Calais in attendance on the French king. As, however, the stipulated instalment of the king's ransom was not ready, he returned to England, leaving King John in the charge of Sir Walter Manny and three other knights. He accompanied his father to Calais on 9 October to assist at the liberation of King John and the ratification of the treaty. He rode with John to Boulogne, where he made his offering in the Church of the Virgin. He returned with King Edward to England at the beginning of November.

Marriage to Joan

On 10 October 1361 Edward married his cousin Joan, Countess of Kent, daughter of Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent (younger son ofEdward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

, and Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

, daughter of Philip III of France

Philip III (1 May 1245 – 5 October 1285), called the Bold (), was King of France from 1270 until his death in 1285. His father, Louis IX, died in Tunis during the Eighth Crusade. Philip, who was accompanying him, returned to France and wa ...

) and widow of Thomas Holland, 1st Earl of Kent

Thomas Holland, 2nd Baron Holand, and ''jure uxoris'' 1st Earl of Kent, Order of the Garter, KG (26 December 1360) was an Kingdom of England, English nobleman and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. By the time of the Crécy campai ...

and the mother of three children. Because Edward and Joan were related in the third degree (and since Edward was the godfather of Joan's elder son Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

) a dispensation was obtained for their marriage from Pope Innocent VI. The marriage was performed at Windsor in the presence of King Edward III by Simon Islip Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

. According to Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart ( Old and Middle French: ''Jehan''; sometimes known as John Froissart in English; – ) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries who wrote several works, including ''Chronicles'' and ''Meli ...

the contract of marriage (the engagement) was entered without the knowledge of the king. Edward and Joan resided at Berkhamsted Castle in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and one of the home counties. It borders Bedfordshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the north-east, Essex to the east, Greater London to the ...

and held the manor of Princes Risborough

Princes Risborough () is a market town and civil parish in Buckinghamshire, England; it is located about south of Aylesbury and northwest of High Wycombe. It lies at the foot of the Chiltern Hills, at the north end of a gap or pass through ...

from 1343; though local history describes the estate as "his palace", many sources suggest it was used more as a hunting lodge.

Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony

On 19 July 1362 Edward III granted Prince Edward all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony, to be held as a principality by liege homage on payment of an ounce of gold each year, together with the title of Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony. During the rest of the year he was occupied in preparing for his departure to his new principality, and after Christmas he received the king and his court at Berkhamsted, took leave of his father and mother, and in the following February sailed with Joan and all his household for Gascony, landing at

On 19 July 1362 Edward III granted Prince Edward all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony, to be held as a principality by liege homage on payment of an ounce of gold each year, together with the title of Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony. During the rest of the year he was occupied in preparing for his departure to his new principality, and after Christmas he received the king and his court at Berkhamsted, took leave of his father and mother, and in the following February sailed with Joan and all his household for Gascony, landing at La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle'') is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime Departments of France, department. Wi ...

.

At La Rochelle the prince was met by John Chandos, the king's lieutenant, and proceeded with him to Poitiers, where he received the homage of the lords of Poitou and Saintonge; he then rode to various cities and at last came to Bordeaux, where from 9 to 30 July he received the homage of the lords of Gascony. He received all graciously and kept a splendid court, residing sometimes at Bordeaux and sometimes at Angoulême

Angoulême (; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Engoulaeme''; ) is a small city in the southwestern French Departments of France, department of Charente, of which it is the Prefectures of France, prefecture.

Located on a plateau overlooking a meander of ...

.

The prince appointed Chandos constable of Guyenne

Guyenne or Guienne ( , ; ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of '' Aquitania Secunda'' and the Catholic archdiocese of Bordeaux.

Name

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transform ...

and provided the knights of his household with profitable offices. They kept much state, and their extravagance displeased the people. Many of the Gascon lords were dissatisfied at being handed over to the dominion of the English, and the favour the prince showed to his own countrymen, and the ostentatious magnificence they exhibited, increased this feeling of dissatisfaction. Arnaud Amanieu, Lord of Albret

Arnaud Amanieu (also ''Arnold'' and ''Amaneus'', 4 August 1338–1401) was the Lord of Albret from 1358.

Amanieu held lands in Gascony which by the Treaty of Brétigny (1360) were obtained by Edward III of England. Edward III appointed his son E ...

, and many more were always ready to give what help they could to the French cause, and Gaston, Count of Foix, though he visited the prince on his first arrival, was thoroughly French at heart and gave some trouble in 1365 by refusing to do homage for Bearn. Charles V, who succeeded to the throne of France in April 1364, was careful to encourage the malcontents, and the prince's position was by no means easy.

In April 1363 Edward mediated between the Counts of Foix and Armagnac, who had for a long time been at war with each other. He also attempted in February 1364 to mediate between Charles of Blois and John of Montfort, the rival competitors for the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany (, ; ) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of France, bordered by the Bay of Biscay to the west, and the English Channel to the north. ...

. Both appeared before him at Poitiers, but his mediation was unsuccessful.

In May 1363 the prince entertained Peter, King of Cyprus, at Angoulême and held a tournament there. At the same time he and his lords excused themselves from assuming the cross—that is, they declined to join Peter's proposed crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. During the summer the lord of Albret was at Paris, and his forces and several other Gascon lords held the French cause in Normandy against the party of Navarre. Meanwhile, war was renewed in Brittany; the prince allowed Chandos to raise and lead a force to succour the party of Montfort, and Chandos won the Battle of Auray

The Battle of Auray took place on 29 September 1364 at the Breton-French town of Auray. This battle was the decisive confrontation of the Breton War of Succession, a part of the Hundred Years' War.

In the battle, which began as a siege, a Bre ...

(29 September 1364) against the French.

As the leaders of the free companies which desolated France were for the most part Englishmen or Gascons, they did not ravage Aquitaine, and the prince was suspected, probably not without cause, of encouraging or at least of taking no pains to discourage their proceedings. Accordingly on 14 November 1364 Edward III called upon him to restrain their ravages.

Spanish campaign (1365–67)

In 1365 the free companies, under Sir Hugh Calveley and other leaders, took service withBertrand du Guesclin

Bertrand du Guesclin (; 1320 – 13 July 1380), nicknamed "The Eagle of Brittany" or "The Black Dog of Brocéliande", was a Breton knight and an important military commander on the French side during the Hundred Years' War. From 1370 to his ...

, who employed them in 1366 in compelling King Peter of Castile

Peter (; 30 August 133423 March 1369), called Peter the Cruel () or the Just (), was King of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. Peter was the last ruler of the main branch of the House of Ivrea. He was excommunicated by Pope Urban V for h ...

to flee from his kingdom, and in setting up his bastard brother, Henry of Trastámara, as king in his stead. Peter, who was in alliance with Edward III, sent messengers to Prince Edward asking his help, and on receiving a gracious answer at Corunna, set out at once, and arrived at Bayonne

Bayonne () is a city in southwestern France near the France–Spain border, Spanish border. It is a communes of France, commune and one of two subprefectures in France, subprefectures in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques departments of France, departm ...

with his son and his three daughters. The prince met him at Capbreton and rode with him to Bordeaux. Many of the prince's lords, both English and Gascon, were unwilling that he should espouse Peter's cause, but he declared that it was not fitting that a bastard should inherit a kingdom or drive out his lawfully born brother, and that no king or king's son ought to suffer such disrespect to royalty; nor could any turn him from his determination to restore the king.

Peter won friends by declaring that he would make Edward's son king of Galicia and would divide his riches among those who helped him. A parliament was held at Bordeaux, in which it was decided to ask the wishes of the English king. Edward III replied that it was right that his son should help Peter, and the prince held another parliament at which the king's letter was read. Then the lords agreed to give their help, provided that their pay was secured to them. To give them the required security, the prince agreed to lend Peter whatever money was necessary.

Edward and Peter then held a conference with Charles of Navarre at Bayonne and agreed with him to allow their troops to pass through his dominions. To persuade him to do this, Peter had, besides other grants, to pay Charles 56,000 florin

The Florentine florin was a gold coin (in Italian ''Fiorino d'oro'') struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time.

It had 54 grains () of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a pu ...

s, and this sum was lent him by Edward. On 23 September a series of agreements (the Treaty of Libourne) were entered into between Edward, Peter, and Charles at Libourne

Libourne (; ) is a commune in the Gironde department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in southwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

It is the wine-making capital of northern Gironde and lies near Saint-Émilion and Pomerol.

Geog ...

, by which Peter covenanted to put the prince in possession of the province of Biscay and the territory and fortress of Castro de Urdialès as pledges for the repayment of this debt, to pay 550,000 florins for six months' wages at specified dates, 250,000 florins being the prince's wages, and 800,000 florins the wages of the lords who were to serve in the expedition. Peter consented to leave his three daughters in Edward's hands as hostages for the fulfilment of these terms, and he further agreed that whenever the king, the prince, or their heirs, the king of England, should march in person against the Moors

The term Moor is an Endonym and exonym, exonym used in European languages to designate the Muslims, Muslim populations of North Africa (the Maghreb) and the Iberian Peninsula (particularly al-Andalus) during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a s ...

, they should have the command of the vanguard before all other Christian kings, and that if they were not present the banner of the king of England should be carried in the vanguard side by side with the banner of Castile.

Edward received 100,000 francs from his father out of the ransom of John II, the late king of France, and broke up his plate to help to pay the soldiers he was taking into his pay. While his army was assembling he remained at Angoulême and was there visited by Peter. He then stayed over Christmas at Bordeaux, where Joan gave birth to their second son Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language">Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'st ...

. Prince Edward left Bordeaux early in February 1367 and joined his army at Dax where he remained three days and received a reinforcement of 400 men-at-arms and 400 archers sent out by Edward III under his brother John of Gaunt. From Dax, Edward advanced via Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port

Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (literally "Saint John t theFoot of hePass"; ; ; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques Departments of France, department in south-western France. It is close to Ostabat in the Pyrenean f ...

through Roncesvalles (in the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

) to Pamplona

Pamplona (; ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Navarre, Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain.

Lying at near above sea level, the city (and the wider Cuenca de Pamplona) is located on the flood pl ...

(the capital of Kingdom of Navarre

The Kingdom of Navarre ( ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona, occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, with its northernmost areas originally reaching the Atlantic Ocean (Bay of Biscay), between present-day Spain and France.

The me ...

).

When Calveley and other English and Gascon leaders of free companies found that Prince Edward was about to fight for Peter, they withdrew from the service of Henry of Trastámara and joined Edward "because he was their natural lord". While the prince was at Pamplona he received a letter of defiance from Henry. From Pamplona Edward marched by Arruiz to Salvatierra, which opened its gates to his army, and thence advanced to Vitoria, intending to march on Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populous municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence of th ...

by this direct route. A body of his knights, which he had sent out to reconnoitre under Sir William Felton, was defeated by a skirmishing party, and he found that Henry had occupied some strong positions, and especially Santo Domingo de la Calzada on the right of the river Ebro

The Ebro (Spanish and Basque ; , , ) is a river of the north and northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, in Spain. It rises in Cantabria and flows , almost entirely in an east-southeast direction. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea, forming a de ...

, and Zaldiaran mountain on the left, which made it impossible for him to reach Burgos through Álava

Álava () or Araba (), officially Araba/Álava, is a Provinces of Spain, province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Country, heir of the ancient Basque señoríos#Lords of Álava, Lordship ...

. Accordingly he crossed the Ebro and encamped under the walls of Logroño

Logroño ( , , ) is the capital of the autonomous community of La Rioja (Spain), La Rioja, Spain. Located in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, primarily in the right (South) bank of the Ebro River, Logroño has historically been a place of pa ...

. During these movements the prince's army had suffered from want of provisions both for men and horses, and from wet and windy weather. At Logroño, however, though provisions were still scarce, they were somewhat better off.

On 30 March 1367, the prince wrote an answer to Henry's letter. On 2 April he left Logroño and moved to Navarrete, La Rioja. Meanwhile, Henry and his French allies had encamped at Nájera, so that the two armies were now near each other. Letters passed between Henry and Edward, for Henry seems to have been anxious to make terms. He declared that Peter was a tyrant and had shed much innocent blood, to which Edward replied that Peter had told him that all the persons he had slain were traitors. On the morning of 3 April, Edward's army marched from Navarrete, and all dismounted while they were yet some distance from Henry's army. The vanguard

The vanguard (sometimes abbreviated to van and also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

...

, in which were 3,000 men-at-arms, both English and Bretons, was led by Lancaster, Chandos, Calveley, and Clisson; the right division was commanded by Armagnac and other Gascon lords; the left, in which some German mercenaries marched with the Gascons, by Jean, Captal de Buch, and the Count of Foix; the rear or main battle by Edward with 3,000 lances; with the prince was Peter and the dethroned James of Majorca and his company; the numbers, however, are scarcely to be depended on.

Before the Battle of Nájera

The Battle of Nájera, also known as the Battle of Navarrete, was fought on 3 April 1367 to the northeast of Nájera, in the province of La Rioja, Castile. It was an episode of the first Castilian Civil War which confronted King Peter of Ca ...

began, Edward prayed aloud to God that as he had come that day to uphold the right and reinstate a disinherited king, God would grant him success. Then, after telling Peter that he should know that day whether he should have his kingdom or not, he cried: "Advance, banner, in the name of God and Saint George

Saint George (;Geʽez: ጊዮርጊስ, , ka, გიორგი, , , died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was an early Christian martyr who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to holy tradition, he was a soldier in the ...

; and God defend our right". The knights of Castile attacked and pressed the English vanguard, but the wings of Henry's army failed to move, so that the Gascon lords were able to attack the main body on the flanks. Then Edward brought the main body of his army into action, and the fighting became intense for he had under him "the flower of chivalry, and the most famous warriors in the whole world". At length Henry's vanguard gave way, and he fled from the field. When the battle was over Edward asked Peter to spare the lives of those who had offended him. Peter assented, with the exception of one notorious traitor, whom he at once put to death; and he also had two others slain the next day.

Among the prisoners was the French marshal Arnoul d'Audrehem, whom Edward had formerly taken prisoner at Poitiers and whom he had released on d'Audrehem giving his word that he would not bear arms against the prince until his ransom was paid. When Edward saw him he reproached him bitterly and called him "liar and traitor". D'Audrehem denied that he was either, and Edward asked him whether he would submit to the judgment of a body of knights. To this d'Audrehem agreed, and Edward chose 12 knights—four English, four Gascons, and four Bretons—to judge between him and the marshal. After he had stated his case, d'Audrehem replied that he had not broken his word, for the army Edward led was not his own; he was merely in the pay of Peter. The knights considered that this view of Edward's position was sound and gave their verdict for d'Audrehem.

On 5 April 1367, Edward and Peter marched to Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populous municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence of th ...

, where they celebrated Easter. Edward, however, did not take up his quarters in the city but camped outside the walls at the Monastery of Las Huelgas. Peter did not pay him any of the money he owed him, and Edward could get nothing from him except a solemn renewal of his bond of the previous 23 September, which he made on 2 May 1367 before the high altar of the Cathedral of Burgos. By this time, Edward began to suspect his ally of treachery. Peter had no intention of paying his debts, and when Edward demanded possession of Biscay, Peter told him that the Biscayans would not consent to be handed over to him. To get rid of his creditor, Peter told Edward that he could not get money at Burgos and persuaded Edward to take up his quarters at Valladolid

Valladolid ( ; ) is a Municipalities of Spain, municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and ''de facto'' capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the pr ...

while he went to Seville, whence he declared he would send the money he owed.

Edward remained at Valladolid

Valladolid ( ; ) is a Municipalities of Spain, municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and ''de facto'' capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the pr ...