Edith Nourse Rogers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edith Rogers (née Nourse; March 19, 1881 – September 10, 1960) was an American

This experience served her well when her husband died in Washington, D.C, on March 28, 1925, a little more than three weeks after starting his seventh term. Spurred by pressure from the Republican Party and the

This experience served her well when her husband died in Washington, D.C, on March 28, 1925, a little more than three weeks after starting his seventh term. Spurred by pressure from the Republican Party and the

Rogers was regarded as capable by her male peers and became a model for younger Congresswomen. Her trademark was an

Rogers was regarded as capable by her male peers and became a model for younger Congresswomen. Her trademark was an

Women had served in the United States military before. In 1901, a female Nurse Corps was established in the Army Medical Department and in 1907 a Navy Nurse Corps was established. However, despite their

Women had served in the United States military before. In 1901, a female Nurse Corps was established in the Army Medical Department and in 1907 a Navy Nurse Corps was established. However, despite their

Edith Rogers introduced a bill in October 1942 to make the WAACs a formal part of the

Edith Rogers introduced a bill in October 1942 to make the WAACs a formal part of the

brochure online

) * Brown, Dorothy M. (1999). "Edith Nourse Rogers: biographical sketch," eds John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes. ''American National Biography,'' volume 18.

* Leventhal, Robert S. (2002)

Retrieved February 16, 2005. * Morden, Bettie J. (1990). ''The Women's Army Corp, 1945–1978.''

book online

* Synnott, Marcia G

The Devens Historical Museum. Retrieved February 15, 2005.

''Rogers, Edith Nourse, 1881-1960. Papers, 1854-1961: A Finding Aid''. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

* , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Rogers, Edith Nourse 1881 births 1960 deaths American social workers American women civilians in World War I American women civilians in World War II Female members of the United States House of Representatives Military personnel from Maine People from Saco, Maine Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts Women in Massachusetts politics American expatriates in France Politicians from Lowell, Massachusetts 20th-century American women politicians American anti-communists 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives Burials at Lowell Cemetery (Lowell, Massachusetts)

social welfare

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance p ...

volunteer and politician

A politician is a person who participates in Public policy, policy-making processes, usually holding an elective position in government. Politicians represent the people, make decisions, and influence the formulation of public policy. The roles ...

who served as a Republican in the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

. She was the first woman elected to Congress from Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. Until 2012, she was the longest serving Congresswoman and was the longest serving female Representative until 2018 (a record now held by Marcy Kaptur

Marcia Carolyn Kaptur ( ; born June 17, 1946) is an American politician serving as the U.S. representative from Ohio's 9th congressional district. Currently in her 22nd term, she has been a member of Congress since 1983.

A member of the Democr ...

). In her 35 years in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

she was a powerful voice for veteran

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in an job, occupation or Craft, field.

A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in the military, armed forces.

A topic o ...

s and sponsored seminal legislation, including the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 (commonly known as the G.I. Bill

The G.I. Bill, formally the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I. (military), G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in ...

), which provided education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

al and financial benefits for veterans returning home from World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the 1942 bill that created the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), and the 1943 bill that created the Women's Army Corps

The Women's Army Corps (WAC; ) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), on 15 May 1942, and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the United S ...

(WAC). She was also instrumental in bringing federal appropriations to her constituency

An electoral (congressional, legislative, etc.) district, sometimes called a constituency, riding, or ward, is a geographical portion of a political unit, such as a country, state or province, city, or administrative region, created to provi ...

, Massachusetts's 5th congressional district

Massachusetts's 5th congressional district is a congressional district in eastern Massachusetts. The district is represented by Katherine Clark of the Democratic Party. Massachusetts's congressional redistricting after the 2010 census changed ...

.

Early life

Edith Nourse was born on March 19, 1881, inSaco, Maine

Saco ( ) is a city in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 20,381 at the 2020 census. It is home to Ferry Beach State Park, Funtown Splashtown USA, Thornton Academy, as well as Saco Valley Shopping Center. General Dynamics ...

, to Franklin T. Nourse, the manager of a textile

Textile is an Hyponymy and hypernymy, umbrella term that includes various Fiber, fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, Staple (textiles)#Filament fiber, filaments, Thread (yarn), threads, and different types of #Fabric, fabric. ...

mill

Mill may refer to:

Science and technology

* Factory

* Mill (grinding)

* Milling (machining)

* Millwork

* Paper mill

* Steel mill, a factory for the manufacture of steel

* Sugarcane mill

* Textile mill

* List of types of mill

* Mill, the arithmetic ...

, and Edith France Riversmith, who volunteered with the Christian church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus Christ. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a syn ...

and social causes. Both parents were from old New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

families, and were able to have their daughter privately tutored until she was fourteen. Edith Nourse then attended and graduated from Rogers Hall School, a private boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

for girls in Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell () is a city in Massachusetts, United States. Alongside Cambridge, Massachusetts, Cambridge, it is one of two traditional county seat, seats of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in ...

, and then Madame Julien's School, a finishing school

A finishing school focuses on teaching young women social graces and upper-class cultural rites as a preparation for entry into society. The name reflects the fact that it follows ordinary school and is intended to complete a young woman's ...

at Neuilly near Paris, France.

Like her mother, she volunteered with the church and other charities. In 1907, she married John Jacob Rogers

John Jacob Rogers (August 18, 1881 – March 28, 1925) was an American lawyer and politician who served seven terms as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts from 1913 until his death in office in 1925.

His wife ...

, newly graduated from Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, Harvard Law School is the oldest law school in continuous operation in the United ...

, who passed the bar and began practicing in Lowell in the same year. In 1911, he started his career in politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

, becoming involved in the city government, and the next year he became the school commissioner. In 1912 he was elected as a Republican to the 63rd United States Congress

The 63rd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1913, t ...

as the Representative from the 5th District of Massachusetts, and began service in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

on March 13, 1913.

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

soon broke out. In 1917, John Rogers, as a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee

The United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, also known as the House Foreign Affairs Committee, is a standing committee of the U.S. House of Representatives with jurisdiction over bills and investigations concerning the foreign affairs ...

, traveled to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

to observe the conditions of the war firsthand. He remained a Congressman during his brief enlistment as a private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

in an artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

training battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of up to one thousand soldiers. A battalion is commanded by a lieutenant colonel and subdivided into several Company (military unit), companies, each typically commanded by a Major (rank), ...

, the 29th Training Battery, 10th Training Battalion, Field Artillery, Fourth Central Officers' Training School from September 2, 1918, until his honorable discharge

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and the ...

on November 29, 1918.

During this period, Edith Rogers volunteered with the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organisation based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It has nearly 90,000 staff, some 920,000 volunteers and 12,000 branches w ...

) in London for a short time, then from 1917 to 1922 as a "Gray Lady" with the American Red Cross

The American National Red Cross is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit Humanitarianism, humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. Clara Barton founded ...

in France and with the Walter Reed Army Medical Center

The Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC), officially known as Walter Reed General Hospital (WRGH) until 1951, was the United States Army, U.S. Army's flagship medical center from 1909 to 2011. Located on in Washington, D.C., it served more ...

in Washington, D.C. This was the start of what became a lifelong commitment to veterans. She also witnessed the conditions faced by women employees and volunteers working with the United States armed forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

; with the exception of a few nurse

Nursing is a health care profession that "integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alle ...

s, they were civilian

A civilian is a person who is not a member of an armed force. It is war crime, illegal under the law of armed conflict to target civilians with military attacks, along with numerous other considerations for civilians during times of war. If a civi ...

s, and received no benefits including no housing, no food, no insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to protect ...

, no medical care

Health care, or healthcare, is the improvement or maintenance of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in people. Health care is deliver ...

, no legal protection, no pension

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a " defined benefit plan", wh ...

s, and no compensation for their families in cases of death. In contrast, the women in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

loaned to the American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

(AEF) in France were military, with the attendant benefits and responsibilities.

At the end of the war, her husband joined the American Legion

The American Legion, commonly known as the Legion, is an Voluntary association, organization of United States, U.S. war veterans headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. It comprises U.S. state, state, Territories of the United States, U.S. terr ...

veteran's organization, and she joined the auxiliary. Her experience with veteran's issues led President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he was one of the most ...

to appoint her as the inspector of new veterans' hospitals from 1922 to 1923, for $1 USD

The United States dollar (symbol: $; currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introduced the U.S. dollar at par with the Spanish silver dollar, divided it int ...

a year. She reported on conditions and her appointment was renewed by both the Coolidge and Hoover administrations. Her first experience in politics was serving as an elector in the U.S. Electoral College

In the United States, the Electoral College is the group of presidential electors that is formed every four years for the sole purpose of voting for the president and vice president in the presidential election. This process is described in ...

during Calvin Coolidge's 1924 presidential campaign.

Congresswoman

This experience served her well when her husband died in Washington, D.C, on March 28, 1925, a little more than three weeks after starting his seventh term. Spurred by pressure from the Republican Party and the

This experience served her well when her husband died in Washington, D.C, on March 28, 1925, a little more than three weeks after starting his seventh term. Spurred by pressure from the Republican Party and the American Legion

The American Legion, commonly known as the Legion, is an Voluntary association, organization of United States, U.S. war veterans headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. It comprises U.S. state, state, Territories of the United States, U.S. terr ...

who approved of her stance on veteran's issues and wanted the sympathy vote, she was urged to run for her late husband's seat. She ran in a special election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, or a bypoll in India, is an election used to fill an office that has become vacant between general elections.

A vacancy may arise as a result of an incumben ...

as the Republican candidate for Representative to the 69th United States Congress

The 69th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1925, ...

from the 5th District of Massachusetts, and beat Eugene Foss, the former Governor of Massachusetts

The governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the head of government of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The governor is the chief executive, head of the state cabinet and the commander-in-chief of the commonw ...

, with a landslide 72 percent of the vote. Like Mae Ella Nolan and Florence Prag Kahn

Florence Kahn (née Prag; November 9, 1866 – November 16, 1948) was an American teacher and politician who in 1925 became the first Jewish woman to serve in the United States Congress. She was only the fifth woman to serve in Congress, and ...

before her, she won her husband's seat.

Her term started on June 30, 1925, making her the sixth woman elected to Congress, after Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin (June 11, 1880 – May 18, 1973) was an American politician and women's rights advocate who became the first woman to hold federal office in the United States. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as ...

, Alice Mary Robertson, Winnifred Sprague Mason Huck, Mae Nolan, Florence Kahn, and Mary Teresa Norton. Like all but Norton, Rogers was a Republican, and like them all she was a member of the House of Representatives; Hattie Wyatt Caraway would become the first woman elected to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

in 1932. Rogers was also the first woman elected to Congress from New England, and the second from an Eastern state after Norton, who was from New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

.

After her election to the 69th Congress, Rogers was reelected to the 70th, 71st, 72nd, 73rd, 74th, 75th, 76th, 77th, 78th, 79th, 80th, 81st, 82nd, 83rd, 84th, 85th, and 86th Congress

The 86th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from January 3, 1959 ...

es. She continued to win with strong majorities, serving a total of 35 years and 18 consecutive terms, until her death on September 10, 1960. She was considered a formidable candidate for U.S. Senate in 1958 against the much younger John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

, but decided not to run. This was the longest tenure of any woman elected to the United States Congress, until surpassed by Barbara Mikulski

Barbara Ann Mikulski ( ; born July 20, 1936) is an American politician and social worker who served as a United States senator from Maryland from 1987 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, she also served i ...

in 2012. Like her husband, she served on the Foreign Affairs Committee, and also on the Civil Service Committee and the Committee on Veterans' Affairs. She chair

A chair is a type of seat, typically designed for one person and consisting of one or more legs, a flat or slightly angled seat and a back-rest. It may be made of wood, metal, or synthetic materials, and may be padded or upholstered in vario ...

ed the Committee on Veterans' Affairs from 1947 to 1948 and again from 1953 to 1954, during the 80th and 83rd Congresses. She was also the first woman to preside as Speaker ''pro tempore'' over the House of Representatives.

On the afternoon of December 13, 1932, Marlin Kemmerer perched on the gallery railing of the U.S. House of Representatives, waved a pistol, and demanded the right to speak. As other representatives fled in panic, Reps. Rogers and Melvin Maas

Melvin Joseph Maas (May 14, 1898 – April 13, 1964) was a U.S. Representative from Minnesota and decorated Major general (United States), Major General of the United States Marine Corps Reserve during World War II.

Early years

Melvin Joseph ...

(R-MN) approached the would-be gunman. Rogers had counseled shell-shocked veterans at Walter Reed Hospital; she looked up at Kemmerer and told the troubled young man, "You won't do anything." Maas, a Marine in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, stood next to Rogers and asked Kemmerer to throw down his pistol. When he did so, he was apprehended by Congressman (R – NY, and future mayor of New York City) Fiorello H. La Guardia and an off-duty D.C. police officer. Kemmerer was released a month later at the request of House members.

Legislator

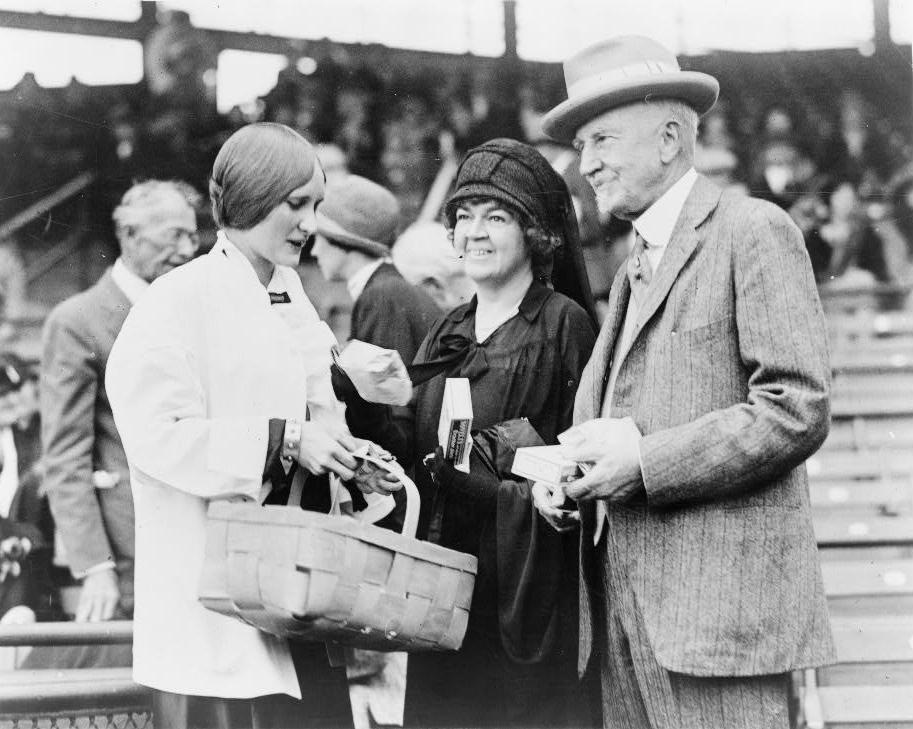

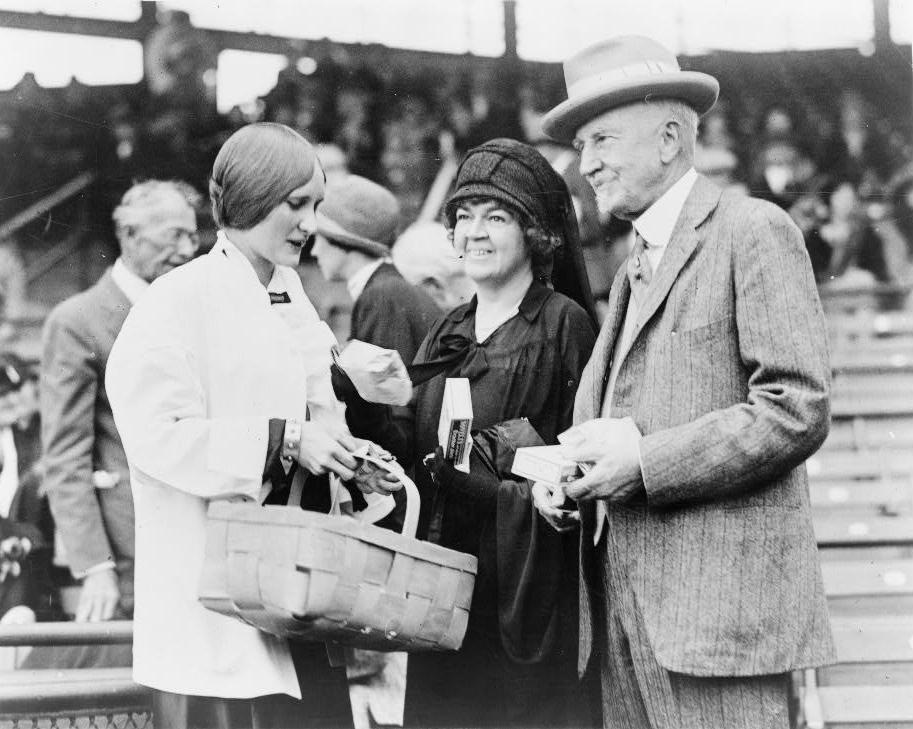

Rogers was regarded as capable by her male peers and became a model for younger Congresswomen. Her trademark was an

Rogers was regarded as capable by her male peers and became a model for younger Congresswomen. Her trademark was an orchid

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant. Orchids are cosmopolitan plants that are found in almost every habitat on Eart ...

or a gardenia

''Gardenia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the coffee family, Rubiaceae, native to the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, Madagascar, Pacific Islands, and Australia.

The genus was named by Carl Linnaeus and John Ellis after ...

on her shoulder. She was also an active legislator and sponsored more than 1,200 bills, over half on veteran or military issues. She voted for a permanent nurse corps in the Department of Veteran's Affairs, and benefits for disabled veterans and veterans of the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

.

In 1937 she sponsored a bill to fund the maintenance of the neglected Congressional Cemetery

The Congressional Cemetery, officially Washington Parish Burial Ground, is a historic and active cemetery located at 1801 E Street in Washington, D.C., in the Hill East neighborhood on the west bank of the Anacostia River. It is the only American ...

, even though her husband was placed at rest in their hometown. She opposed child labor

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation w ...

, and fought for "equal pay for equal work

Equal pay for equal work is the concept of labour rights that individuals in the same workplace be given equal pay. It is most commonly used in the context of sexual discrimination, in relation to the gender pay gap. Equal pay relates to the fu ...

" and a 48-hour workweek for women, though she believed a woman's first priority was home and family. She supported local economic autonomy; on April 19, 1934, she read a petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer called supplication.

In the colloquial sense, a petition is a document addressed to an officia ...

against the expanded business regulations of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

, and all 1,200 signature

A signature (; from , "to sign") is a depiction of someone's name, nickname, or even a simple "X" or other mark that a person writes on documents as a proof of identity and intent. Signatures are often, but not always, Handwriting, handwritt ...

s, into the ''Congressional Record

The ''Congressional Record'' is the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress, published by the United States Government Publishing Office and issued when Congress is in session. The Congressional Record Ind ...

''. Rogers voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960

It is also known as the "Year of Africa" because of major events—particularly the independence of seventeen African nations—that focused global attention on the continent and intensified feelings of Pan-Africanism.

Events January

* Janu ...

.

Rogers was an advocate for the textile and leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning (leather), tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffal ...

industries in Massachusetts. She acquired funding for flood control

Flood management or flood control are methods used to reduce or prevent the detrimental effects of flood waters. Flooding can be caused by a mix of both natural processes, such as extreme weather upstream, and human changes to waterbodies and ru ...

measures in the Merrimack River

The Merrimack River (or Merrimac River, an occasional earlier spelling) is a river in the northeastern United States. It rises at the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipesaukee rivers in Franklin, New Hampshire, flows southward into M ...

basin, helped Camp Devens become Fort Devens, Massachusetts in 1931, and was responsible for many other jobs and grants in the state.

In 1935 Rogers twice introduced resolutions to authorize funding for traffic safety studies, eventually resulting in $75,000 for Bureau of Public Roads

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is a division of the United States Department of Transportation that specializes in highway transportation. The agency's major activities are grouped into two programs, the Federal-aid Highway Program a ...

to study traffic safety conditions.

A confidential 1943 analysis of the House Foreign Affairs Committee

The United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, also known as the House Foreign Affairs Committee, is a standing committee of the U.S. House of Representatives with jurisdiction over bills and investigations concerning the foreign affairs ...

by Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

for the British Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

described Rogers as

It is noted in the private papers of ETO Logistics Chief Lt. Gen. John C. H. Lee

John Clifford Hodges Lee (1 August 1887 – 30 August 1958) was a career US Army engineer, who rose to the rank of lieutenant general (United States), lieutenant general and commanded the Communications Zone (ComZ) in the European Theater of Oper ...

that she was received at Cherbourg, France on 4 October 1944. The following day she decorated Col. Benjamin B. Talley, commander of operations at Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach was one of five beach landing sectors of the amphibious assault component of Operation Overlord during the Second World War.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies of World War II, Allies invaded German military administration in occupied Fra ...

on and after D-Day with the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievemen ...

for his work in operating the beach-port at Omaha.

German refugees

Rogers was one of the first members of Congress to speak out againstAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's treatment of Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

s. The expulsion of Jews from Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

without proper papers caused a refugee crisis in 1938, and after the Evian Conference failed to lift immigration quotas in the 38 participating nations, Edith Rogers co-sponsored the Wagner-Rogers Bill with Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

Robert F. Wagner. Introduced to the Senate on February 9, 1939, and to the House on February 14, it would have allowed 20,000 German Jewish refugees

This article lists expulsions, refugee crises and other forms of displacement that have affected Jews.

Timeline

The following is a list of Jewish expulsions and events that prompted significant streams of Jewish refugees.

Assyrian captivity

...

under the age of 14 to settle in the United States.

The bill was supported by religious and labor groups, and the news media

The news media or news industry are forms of mass media that focus on delivering news to the general public. These include News agency, news agencies, newspapers, news magazines, News broadcasting, news channels etc.

History

Some of the fir ...

, but was strongly opposed by patriotic

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to one's country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, politic ...

groups who believed "charity begins at home". After rancorous 1938 elections in the House and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, Congress had turned conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

, and despite provisions requiring the children to be supported by private individuals and agencies, not public funds, organizations like the American Legion, the Daughters of the American Revolution

The National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (often abbreviated as DAR or NSDAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a patriot of the American Revolutionary War.

A non-p ...

, and the American Coalition of Patriotic Societies lined up against it. With rising nativism and antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

, economic troubles, and Congress asserting its independence, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

was unable to support the bill, and it failed.

WAAC

Women had served in the United States military before. In 1901, a female Nurse Corps was established in the Army Medical Department and in 1907 a Navy Nurse Corps was established. However, despite their

Women had served in the United States military before. In 1901, a female Nurse Corps was established in the Army Medical Department and in 1907 a Navy Nurse Corps was established. However, despite their uniform

A uniform is a variety of costume worn by members of an organization while usually participating in that organization's activity. Modern uniforms are most often worn by armed forces and paramilitary organizations such as police, emergency serv ...

s the nurses were civilian employees with few benefits. They slowly gained additional privileges, including "relative rank

A rank is a position in a hierarchy. It can be formally recognized—for example, cardinal, chief executive officer, general, professor—or unofficial.

People Formal ranks

* Academic rank

* Corporate title

* Diplomatic rank

* Hierarchy ...

s" and insignia in 1920, a retirement pension in 1926, and a disability pension if injured in the line of duty in 1926. Rogers voted to support the pensions.

The first American women enlisted into the regular armed forces were 13,000 women admitted into active duty in the Navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

and Marines during World War I, and a much smaller number admitted into the Coast Guard

A coast guard or coastguard is a Maritime Security Regimes, maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with cust ...

. These " Yeomanettes" and "women Marines" primarily served in clerical

Clerical may refer to:

* Pertaining to the clergy

* Pertaining to a clerical worker

* Clerical script, a style of Chinese calligraphy

* Clerical People's Party

See also

* Cleric (disambiguation)

* Clerk (disambiguation)

{{disambiguation ...

positions. They received the same benefits and responsibilities as men, including identical pay, and were treated as veterans after the war. These women were quickly demobilized when hostilities ceased, and aside from the Nurse Corps, the soldiery became once again exclusively male. In contrast, the army clerks and "Hello Girls" who worked the telephones during World War I were civilian contractors with no benefits.

Rogers' volunteer work in World War I exposed her to the status of the women with the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

, and the much more egalitarian role of women in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

. With this inspiration and model, Edith Rogers introduced a bill to the 76th Congress in early 1941 to establish a Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) during World War II. The bill was intended to free men for combat duty by creating a cadre of 25,000 noncombatant clerical workers. The bill languished in the face of strong opposition to women in the army, and indifference in the face of higher priorities like the lend-lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (),3,000 Hurricanes and >4,000 other aircraft)

* 28 naval vessels:

** 1 Battleship. (HMS Royal Sovereign (05), HMS Royal Sovereign)

* ...

bill, price control

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of go ...

s, and ramping up war production.

After the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

, manpower shortages threatened as productivity increased. Rogers approached the Army Chief of Staff George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

, and with his strong support she reintroduced the bill to the 77th Congress with a new upper limit of 150,000 women, and an amendment giving the women full military status. The amendment was resoundingly rejected but the unamended bill passed, and on May 14, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's signature turned "An Act to Establish the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps" into Public Law

Public law is the part of law that governs relations and affairs between legal persons and a government, between different institutions within a state, between different branches of governments, as well as relationships between persons that ...

77-554.

While "Auxiliaries", and thus not a part of the regular army, the WAACs were given food, clothing, housing, medical care, training, and pay. They did not receive death benefits, medical care as veterans, retirement or disability pensions, or overseas pay. They were given auxiliary ranks which granted no command authority over men, and also earned less than men with comparable regular army ranks, until November 1, 1942, when legislation equalized their remuneration. Since they were not regular army they were not governed by army regulations, and if captured, were not protected by international conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

(POWs).

On July 30, 1942, Public Law 77-554 created the WAVES

United States Naval Reserve (Women's Reserve), better known as the WAVES (for Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), was the women's branch of the United States Naval Reserve during World War II. It was established on July 21, 1942, ...

(Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) in the Navy. The law passed with no significant opposition, despite granting the WAVES full status as military reserves, under the same Naval regulations that applied to men. The WAVES were granted equal pay and benefits, but no retirement or disability pensions and were restricted to noncombat duties in the continental United States

The contiguous United States, also known as the U.S. mainland, officially referred to as the conterminous United States, consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the District of Columbia of the United States in central North America. The te ...

. The similarly empowered SPARS

SPARS was the authorized nickname for the United States Coast Guard (USCG) Women's Reserve. The nickname was derived from the USCG's motto, "—"Always Ready" (''SPAR''). The Women's Reserve was established by law in November 1942 during Wor ...

(from the motto

A motto (derived from the Latin language, Latin , 'mutter', by way of Italian language, Italian , 'word' or 'sentence') is a Sentence (linguistics), sentence or phrase expressing a belief or purpose, or the general motivation or intention of a ...

''Semper Paratus''/"Always Ready") in the Coast Guard, and the Marine Corps Women's Reserve soon followed. The September 27, 1944, Public Law 78-441 allowed WAVES to also serve in Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

and Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

.

The initial goal of 25,000 WAACs by June 30, 1943, was passed in November 1942. The goal was reset at 150,000, the maximum allowed by law, but competition from sister units like the WAVES and the private war industry, the retention of high educational and moral standards, underuse of skilled WAACs, and a spate of vicious gossip and bad publicity in 1943 prevented the goal from ever being reached.

The rumors of immoral conduct were widely published by the press without verification, and harmed morale. Investigations by the War Department and Edith Rogers uncovered nothing; and the incidence of disorderly and criminal

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a State (polity), state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definiti ...

conduct among the WAACs was a tiny fraction of that among the male military population, venereal disease

A sexually transmitted infection (STI), also referred to as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) and the older term venereal disease (VD), is an infection that is spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, or ...

was almost non-existent, and the pregnancy

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring gestation, gestates inside a woman's uterus. A multiple birth, multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Conception (biology), Conception usually occurs ...

rate was far below civilian women. Despite this, the June 30, 1943, enlistment reached 60,000.

Women's Army Corps

Edith Rogers introduced a bill in October 1942 to make the WAACs a formal part of the

Edith Rogers introduced a bill in October 1942 to make the WAACs a formal part of the United States Army Reserve

The United States Army Reserve (USAR) is a Military reserve force, reserve force of the United States Army. Together, the Army Reserve and the Army National Guard constitute the Army element of the reserve components of the United States Armed ...

. Fearing it would hinder other war legislation, George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

declined to support it and it failed. He changed his mind in 1943, and asked Congress to give the WAAC full military status. Experience showed that the two separate systems were too difficult to manage. Rogers and Oveta Culp Hobby, the first Director of the WAACs, drafted a new bill which was debated in the House for six months before passing. On July 1, 1943, Roosevelt signed "An Act to Establish the Women's Army Corps in the Army of the United States", which became Public Law 78-110. The "auxiliary" portion of the name was officially dropped, and on July 5, 1943, Hobby was commissioned as a full colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

, the highest rank allowed in the new Women's Army Corps.

The WACs received the same pay, allowances, and benefits as regular army units, though time spent as a WAC did not count toward time served and the allowance for dependents was heavily restricted. The WACs were now discipline

Discipline is the self-control that is gained by requiring that rules or orders be obeyed, and the ability to keep working at something that is difficult. Disciplinarians believe that such self-control is of the utmost importance and enforce a ...

d, promoted, and given the same legal protections as regular Army units, and the 150,000 ceiling was lifted. While the legislators made it very clear they expected the WACs to be noncombatants, the bill contained no specific restrictions. Existing Army regulations still prohibited them from combat training with weapons, tactical exercises, duty assignments requiring weapons, supervising men, and jobs requiring great physical strength, unless waived by the United States Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the President of the United States, U.S. president's United States Cabinet, Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's Presidency of George Washington, administration. A similar position, called either "Sec ...

; but of the 628 Army specialties, women now qualified for 406. Additional Army regulations were adopted to cover pregnancy, marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognised union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children (if any), and b ...

, and maternity

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of gestatio ...

care.

As part of the regular Army, WACs could not be permanently assigned as cook

Cook or The Cook may refer to:

Food preparation

* Cooking, the preparation of food

* Cook (domestic worker), a household staff member who prepares food

* Cook (profession), an individual who prepares food for consumption in the food industry

* C ...

s, waitress

Waiting staff ( BrE), waiters () / waitresses (), or servers (AmE) are those who work at a restaurant, a diner, or a bar and sometimes in private homes, attending to customers by supplying them with food and drink as requested. Waiting staff ...

es, janitor

A cleaner, cleanser or cleaning operative is a type of Industry (economics), industrial or domestic worker who is tasked with cleaning a space. A janitor (Scotland, United States and Canada), also known as a custodian, Facility Operator, porter ...

s, or to any other civilian jobs. While most became clerks, secretaries

A secretary, administrative assistant, executive assistant, Personal assistant, personal secretary, or other similar titles is an individual whose work consists of supporting management, including executives, using a variety of project manageme ...

, and drivers, they also became mechanic

A mechanic is a skilled tradesperson who uses tools to build, maintain, or repair machinery, especially engines. Formerly, the term meant any member of the handicraft trades, but by the early 20th century, it had come to mean one who works w ...

s, weather

Weather is the state of the atmosphere, describing for example the degree to which it is hot or cold, wet or dry, calm or stormy, clear or cloud cover, cloudy. On Earth, most weather phenomena occur in the lowest layer of the planet's atmo ...

observers, radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

operators, medical technicians, intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

analysts, chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

s, postal worker

A postal worker is one who works for a post office, such as a mail carrier. In the U.S., postal workers are represented by the National Association of Letter Carriers, AFL–CIO, National Postal Mail Handlers Union – NPMHU, the National Associ ...

s, and heavy equipment

Heavy equipment, heavy machinery, earthmovers, construction vehicles, or construction equipment, refers to heavy-duty vehicles specially designed to execute construction tasks, most frequently involving earthwork operations or other large con ...

operators. The restriction against combat training and carrying weapons was waived in several cases, allowing women to serve as pay officers, military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. Not to be confused with civilian police, who are legally part of the civilian populace. In wartime operations, the military police may supp ...

, in code rooms, or as drivers in some overseas areas. On January 10, 1943, a 200-WAC unit was even trained as an antiaircraft gun

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface ( submarine-launched), and air-ba ...

crew, though they were not allowed to fire the 90 mm weapon. Several were also assigned to the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

.

WACs also served overseas, and close to the front lines. During the invasion of Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

by the U.S. Fifth Army under Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (1 May 1896 – 17 April 1984) was a United States Army officer who fought in World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the U.S. Army during World War II.

During World War I, he wa ...

, a 60-woman platoon

A platoon is a Military organization, military unit typically composed of two to four squads, Section (military unit), sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the Military branch, branch, but a platoon can ...

served in the advance headquarters, sometimes only a few miles from the front lines; and in the south Pacific WACs moved into Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

, Philippines only three days after occupation. By V-J Day

Victory over Japan Day (also known as V-J Day, Victory in the Pacific Day, or V-P Day) is the day on which Imperial Japan surrendered in World War II, in effect bringing the war to an end. The term has been applied to both of the days on wh ...

, one fifth had served overseas.

On V-E Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945; it marked the official surrender of all German military operations ...

, May 8, 1945, WACs reached their peak of 99,388 women in active duty, and a total of more than 140,000 WACs served during World War II. The majority served in the Army Service Forces

The Army Service Forces was one of the three autonomous components of the United States Army during World War II, the others being the Army Air Forces and Army Ground Forces, created on 9 March 1942. By dividing the Army into three large comman ...

, but large numbers also served as "Air WACs" in the Army Air Force

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

, largely because of the enthusiastic and early support of General Henry H. Arnold

Henry Harley "Hap" Arnold (25 June 1886 – 15 January 1950) was an American General officers in the United States, general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army and later, General of the Ai ...

, and in the Army Medical Corps. Only 2,000 served in the combat-heavy Army Ground Force.

Despite the noncombatant status of her directorate, Oveta Hobby was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, the third-highest U.S. Army decoration and the highest one which can be awarded for non-combat service. The WACs were awarded a total of 62 Legions of Merit, 565 Bronze Star

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

Wh ...

s, 3 Air Medal

The Air Medal (AM) is a military decoration of the United States Armed Forces. It was created in 1942 and is awarded for single acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight.

Criteria

The Air Medal was establi ...

s, and 16 Purple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the president to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, ...

s.

The initial bill called for the WACs to be discontinued 6 months after the President declared the war was at an end, but despite the resistance in the House and the smear campaign, the WACs performed capably and well. According to Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, "During the time I have had WACs under my command they have met every test and task assigned to them.... Their contributions in efficiency, skill, spirit, and determination are immeasurable." Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

called them "my best soldiers". With the rush to send as many men home as quickly as possible after the cessation of hostilities, WACs were even more in demand.

Supported by Eisenhower, the "Act to Establish a Permanent Nurse Corps of the Army and Navy and to Establish a Women's Medical Specialists Corps in the Army", or the Army-Navy Nurses Act of 1947, passed and became Public Law 8036, granting regular, permanent status to female nurses. Then in early 1946, Chief of Staff Eisenhower ordered legislation drafted to make the WACs a permanent part of the armed forces. The bill was unanimously approved by the Senate but the House Armed Forces Committee amended the bill to restrict women to reserve status, with only Representative Margaret Chase Smith dissenting.

After vehement objection by Eisenhower, who wrote "the women of America must share the responsibility for the security of their country in a future emergency as the women of England did in World War II"; the personal testimony of Secretary of Defense James Forrestal

James Vincent Forrestal (February 15, 1892 – May 22, 1949) was the last Cabinet (government), cabinet-level United States Secretary of the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense.

Forrestal came from a very strict middle-cla ...

; and support from every major military commander including the Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the highest-ranking officer of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an Admiral (United States), admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the United States Secretary ...

Fleet Admiral

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

Chester W. Nimitz

Chester William Nimitz (; 24 February 1885 – 20 February 1966) was a fleet admiral in the United States Navy. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander in Chief, US Pacific Fleet, and Commander in Chief, ...

, and MacArthur, the Commander of United States Army Forces in the Far East

United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) (Filipino language, Filipino: ''Hukbong Katihan ng Estados Unidos sa Malayong Silangan''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Fuerzas del Ejército de los Estados Unidos en el Lejano Oriente'') was a m ...

, who wrote, "we cannot ask these women to remain on duty, nor can we ask qualified personnel to volunteer, if we cannot offer them permanent status"; supporting articles in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' and ''The Christian Science Monitor

''The Christian Science Monitor'' (''CSM''), commonly known as ''The Monitor'', is a nonprofit news organization that publishes daily articles both in Electronic publishing, electronic format and a weekly print edition. It was founded in 1908 ...

'', and the support of Senator and future President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

and Representative Edith Rogers, the amended bill passed in the House but was rejected in the Senate. A compromise restored the original wording but limited the total number of women allowed to serve for the first few years, which then passed regular army, which was submitted to Congress in 1947 in the midst of a massive reorganization of the unanimously in the Senate, and 206 to 133 in the House. On June 12, 1948, President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

signed the "Women's Armed Services Integration Act", making it Public Law 80-625.

On December 3, 1948, the Director of the WACs, Colonel Mary A. Hallaren, became the first commissioned female officer in the U.S. Army. The WACs still were not equal. They were limited in numbers, had no command authority over men, were restricted from combat training and duties, had additional restrictions on claiming dependents, and aside from their director, no woman could be promoted above the rank of lieutenant colonel. WACs served in the Korean and Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

s.

On November 8, 1967, Congress lifted the restriction on promotions, allowing the first WAC generals, and then, on October 29, 1978, the Women's Army Corps was disestablished and women were integrated into the rest of the Army.

G.I. Bill

In 1944, Edith Rogers helped draft, and then co-sponsored the G. I. Bill, with Representative John E. Rankin, and SenatorsErnest McFarland

Ernest William McFarland (October 9, 1894 – June 8, 1984) was an American politician, jurist and, with Warren Atherton, one of the "Fathers of the G.I. Bill". He served in all three branches of government, two at the state level, one at the ...

, and Bennett Champ Clark. The bill provided for education and vocational training, low-interest loan

In finance, a loan is the tender of money by one party to another with an agreement to pay it back. The recipient, or borrower, incurs a debt and is usually required to pay interest for the use of the money.

The document evidencing the deb ...

s for homes, farm

A farm (also called an agricultural holding) is an area of land that is devoted primarily to agricultural processes with the primary objective of producing food and other crops; it is the basic facility in food production. The name is used fo ...

s, and business

Business is the practice of making one's living or making money by producing or Trade, buying and selling Product (business), products (such as goods and Service (economics), services). It is also "any activity or enterprise entered into for ...

es, and limited unemployment benefit

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for Work (hu ...

s for returning servicemen. On June 22, 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed "The Servicemen's Readjustment Act", which became Public Law 78-346 and handed her the first pen. As a result of the bill, roughly half of the returning veterans went on to higher education.

In August 2019, as part of the Forever GI Bill, the Edith Nourse Rogers Science Technology Engineering Math (STEM) Scholarship will be available to veterans pursuing STEM careers. This scholarship will allow recipients to receive up to nine additional months Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits.

After World War II

During theCold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

Rogers supported the House Committee on Un-American Activities

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty an ...

and Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

during the "Red Scare

A Red Scare is a form of moral panic provoked by fear of the rise of left-wing ideologies in a society, especially communism and socialism. Historically, red scares have led to mass political persecution, scapegoating, and the ousting of thos ...

". Although she supported the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, in 1953 she said that UN headquarters should be expelled from the U.S. if communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

were admitted. In 1954, she opposed sending U.S. soldiers to Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

.

Death and legacy

Edith Rogers died on September 10, 1960, at Philips House,Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General or MGH) is a teaching hospital located in the West End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. It is the original and largest clinical education and research facility of Harvard Medical School/Harvar ...

, in Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

in the midst of her 19th Congressional campaign. She was interred with her husband in Lowell Cemetery, in their hometown of Lowell.

She received many honors during her life, including the Distinguished Service Medal of the American Legion in 1950. In honor of her work with veterans, the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital in Bedford, Massachusetts

Bedford is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population of Bedford was 14,161 at th2022 United States census

History

''The following compilation comes from Ellen Abrams (1999) based on information from Abram Engl ...

bears her name.

The Women's Army Corps Museum (now the United States Army Women's Museum

The United States Army Women's Museum is an educational institution located in Fort Gregg-Adams, Virginia. It provides exhibits and information related to the role of women in the United States Army, especially the Women's Army Corps.

The museu ...

), established on May 14, 1955, in Fort McClellan, Alabama

Fort McClellan, originally Camp McClellan, is a United States Army post located adjacent to the city of Anniston, Alabama. During World War II, it was one of the largest U.S. Army installations, training an estimated half-million troops. After t ...

, was renamed the Edith Nourse Rogers Museum on August 18, 1961, but returned to its original name on May 14, 1977.

The Edith Nourse Rogers Stem Academy in Lowell, Massachusetts is named after Edith Rogers. Among its famous graduates is former Congressman, and current chancellor of The University of Massachusetts Lowell

The University of Massachusetts Lowell (UMass Lowell and UML) is a Public university, public research university in Lowell, Massachusetts, with a satellite campus in Haverhill, Massachusetts. It is the northernmost member of the University of M ...

, Marty Meehan, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from January 5, 1993, to July 1, 2007. Edith Nourse Rogers Stem Academy serves approximately 1200 students in grades K through 8.

In 1998, Rogers was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame

The National Women's Hall of Fame (NWHF) is an American institution founded to honor and recognize women. It was incorporated in 1969 in Seneca Falls, New York, and first inducted honorees in 1973. As of 2024, the Hall has honored 312 inducte ...

.

Governor Deval Patrick signed a Proclamation declaring June 30, 2012, as "Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers Day."

See also

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1950–99)

There are several lists of United States Congress members who died in office. These include:

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–1949)

*List ...

* Women in the United States House of Representatives

References

Further reading

* Bellafaire, Judith A. "The Women's Army Corps: A commemoration of World War II service."United States Army Center of Military History

The United States Army Center of Military History (CMH) is a directorate within the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. The Institute of Heraldry remains within the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Arm ...

publication 72-15.brochure online

) * Brown, Dorothy M. (1999). "Edith Nourse Rogers: biographical sketch," eds John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes. ''American National Biography,'' volume 18.

* Leventhal, Robert S. (2002)

Retrieved February 16, 2005. * Morden, Bettie J. (1990). ''The Women's Army Corp, 1945–1978.''

United States Army Center of Military History

The United States Army Center of Military History (CMH) is a directorate within the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. The Institute of Heraldry remains within the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Arm ...

publication 30-14.book online

* Synnott, Marcia G

The Devens Historical Museum. Retrieved February 15, 2005.

External links

* Retrieved on 2008-02-17''Rogers, Edith Nourse, 1881-1960. Papers, 1854-1961: A Finding Aid''. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

* , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Rogers, Edith Nourse 1881 births 1960 deaths American social workers American women civilians in World War I American women civilians in World War II Female members of the United States House of Representatives Military personnel from Maine People from Saco, Maine Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts Women in Massachusetts politics American expatriates in France Politicians from Lowell, Massachusetts 20th-century American women politicians American anti-communists 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives Burials at Lowell Cemetery (Lowell, Massachusetts)