Earth's Mantle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Earth's mantle is a layer of silicate rock between the crust and the

Earth's mantle is a layer of silicate rock between the crust and the

The top of the mantle is defined by a sudden increase in seismic velocity, which was first noted by Andrija Mohorovičić in 1909; this boundary is now referred to as the

The top of the mantle is defined by a sudden increase in seismic velocity, which was first noted by Andrija Mohorovičić in 1909; this boundary is now referred to as the

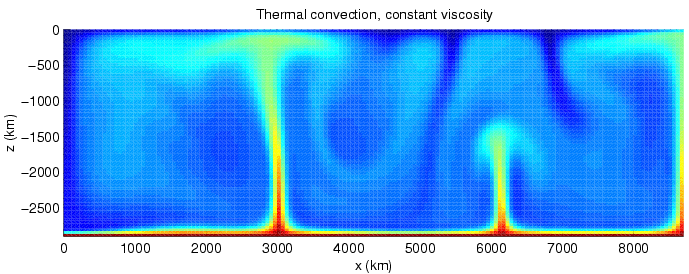

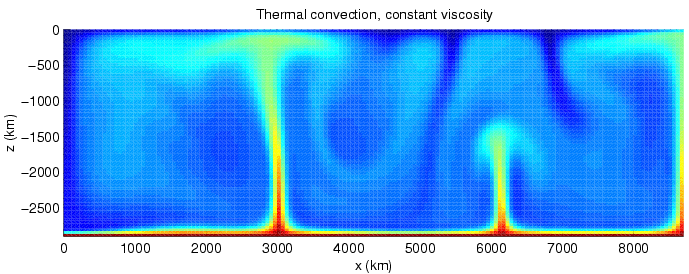

Because of the temperature difference between the Earth's surface and outer core and the ability of the crystalline rocks at high pressure and temperature to undergo slow, creeping, viscous-like deformation over millions of years, there is a

Because of the temperature difference between the Earth's surface and outer core and the ability of the crystalline rocks at high pressure and temperature to undergo slow, creeping, viscous-like deformation over millions of years, there is a

Mantle Viscosity and the Thickness of the Convective Downwellings

igw.uni-jena.de The mantle within about above the core–mantle boundary appears to have distinctly different seismic properties than the mantle at slightly shallower depths; this unusual mantle region just above the core is called D ("D double-prime"), a nomenclature introduced over 50 years ago by the geophysicist Keith Bullen. D may consist of material from subducted slabs that descended and came to rest at the core–mantle boundary or from a new mineral polymorph discovered in perovskite called post-perovskite. Earthquakes at shallow depths are a result of faulting; however, below about the hot, high pressure conditions ought to inhibit further seismicity. The mantle is considered to be viscous and incapable of brittle faulting. However, in subduction zones, earthquakes are observed down to . A number of mechanisms have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, including dehydration, thermal runaway, and phase change. The geothermal gradient can be lowered where cool material from the surface sinks downward, increasing the strength of the surrounding mantle, and allowing earthquakes to occur down to a depth of between and . The pressure at the bottom of the mantle is ~. Pressure increases as depth increases, since the material beneath has to support the weight of all the material above it. The entire mantle, however, is thought to deform like a fluid on long timescales, with permanent plastic deformation accommodated by the movement of point, line, and/or planar defects through the solid crystals composing the mantle. Estimates for the viscosity of the upper mantle range between and pascal seconds (Pa·s) depending on depth, temperature, composition, state of stress, and numerous other factors. Thus, the upper mantle can only flow very slowly. However, when large forces are applied to the uppermost mantle it can become weaker, and this effect is thought to be important in allowing the formation of tectonic plate boundaries.

Super-computer Provides First Glimpse Of Earth's Early Magma Interior

The Biggest Dig: Japan builds a ship to drill to the earth's mantle

– ''Scientific American'' (September 2005)

Information on the Mohole Project

{{Authority control Structure of the Earth

outer core

Earth's outer core is a fluid layer about thick, composed of mostly iron and nickel that lies above Earth's solid Earth's inner core, inner core and below its Earth's mantle, mantle. The outer core begins approximately beneath Earth's surface ...

. It has a mass of and makes up 67% of the mass of Earth. It has a thickness of making up about 46% of Earth's radius and 84% of Earth's volume. It is predominantly solid but, on geologic time scale

The geologic time scale or geological time scale (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochro ...

s, it behaves as a viscous

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for example, syrup h ...

fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that may continuously motion, move and Deformation (physics), deform (''flow'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are M ...

, sometimes described as having the consistency of caramel. Partial melting of the mantle at mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a undersea mountain range, seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading ...

s produces oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

, and partial melting of the mantle at subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere and some continental lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at the convergent boundaries between tectonic plates. Where one tectonic plate converges with a second p ...

zones produces continental crust

Continental crust is the layer of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks that forms the geological continents and the areas of shallow seabed close to their shores, known as '' continental shelves''. This layer is sometimes called '' si ...

.

Structure

Rheology

Earth'supper mantle

The upper mantle of Earth is a very thick layer of rock inside the planet, which begins just beneath the crust (geology), crust (at about under the oceans and about under the continents) and ends at the top of the lower mantle (Earth), lower man ...

is divided into two major rheological layers: the rigid lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the lithospheric mantle, the topmost portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time ...

comprising the uppermost mantle (the lithospheric mantle), and the more ductile asthenosphere

The asthenosphere () is the mechanically weak and ductile region of the upper mantle of Earth. It lies below the lithosphere, at a depth between c. below the surface, and extends as deep as . However, the lower boundary of the asthenosphere i ...

, separated by the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. Lithosphere underlying ocean crust has a thickness of around , whereas lithosphere underlying continental crust generally has a thickness of . The lithosphere and overlying crust make up tectonic plates

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

, which move over the asthenosphere. Below the asthenosphere, the mantle is again relatively rigid.

The Earth's mantle is divided into three major layers defined by sudden changes in seismic velocity:

* the upper mantle

The upper mantle of Earth is a very thick layer of rock inside the planet, which begins just beneath the crust (geology), crust (at about under the oceans and about under the continents) and ends at the top of the lower mantle (Earth), lower man ...

(starting at the Moho, or base of the crust around downward to )

* the transition zone (approximately ), in which wadsleyite

Wadsleyite is an orthorhombic mineral with the formula β-(Mg,Fe)2SiO4. It was first found in nature in the Peace River meteorite from Alberta, Canada. It is formed by a phase transformation from olivine (α-(Mg,Fe)2SiO4) under increasing press ...

(≈ ) and ringwoodite (≈ ) are stable

* the lower mantle (approximately ), in which bridgmanite (≈ ) and post-perovskite (≈ ) are stable

The lower ~200 km of the lower mantle constitutes the D" region (D-double-prime), a region with anomalous seismic properties. This region also contains large low-shear-velocity provinces

Large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs), also called large low-velocity provinces (LLVPs) or superplumes, are characteristic structures of parts of the lowermost mantle, the region surrounding the outer core deep inside the Earth. These provi ...

and ultra low velocity zone

Ultra low velocity zones (ULVZs) are patches on the core-mantle boundary that have extremely low seismic velocities. The zones are mapped to be hundreds of kilometers in diameter and tens of kilometers thick. Their shear wave velocities can be ...

s.

Mineralogical structure

Mohorovičić discontinuity

The Mohorovičić discontinuity ( ; )usually called the Moho discontinuity, Moho boundary, or just Mohois the boundary between the Earth's crust, crust and the Earth's mantle, mantle of Earth. It is defined by the distinct change in velocity of s ...

or "Moho".

The upper mantle is dominantly peridotite

Peridotite ( ) is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock consisting mostly of the silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium (Mg2+), reflecting the high pr ...

, composed primarily of variable proportions of the minerals olivine

The mineral olivine () is a magnesium iron Silicate minerals, silicate with the chemical formula . It is a type of Nesosilicates, nesosilicate or orthosilicate. The primary component of the Earth's upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle, it is a com ...

, clinopyroxene, orthopyroxene, and an aluminous phase. The aluminous phase is plagioclase

Plagioclase ( ) is a series of Silicate minerals#Tectosilicates, tectosilicate (framework silicate) minerals within the feldspar group. Rather than referring to a particular mineral with a specific chemical composition, plagioclase is a continu ...

in the uppermost mantle, then spinel

Spinel () is the magnesium/aluminium member of the larger spinel group of minerals. It has the formula in the cubic crystal system. Its name comes from the Latin word , a diminutive form of ''spine,'' in reference to its pointed crystals.

Prop ...

, and then garnet

Garnets () are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

Garnet minerals, while sharing similar physical and crystallographic properties, exhibit a wide range of chemical compositions, de ...

below ~. Gradually through the upper mantle, pyroxenes become less stable and transform into majoritic garnet.

At the top of the transition zone, olivine undergoes isochemical phase transition

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic Sta ...

s to wadsleyite

Wadsleyite is an orthorhombic mineral with the formula β-(Mg,Fe)2SiO4. It was first found in nature in the Peace River meteorite from Alberta, Canada. It is formed by a phase transformation from olivine (α-(Mg,Fe)2SiO4) under increasing press ...

and ringwoodite. Unlike nominally anhydrous olivine, these high-pressure olivine polymorphs have a large capacity to store water in their crystal structure. This and other evidence has led to the hypothesis that the transition zone may host a large quantity of water. At the base of the transition zone, ringwoodite decomposes into bridgmanite (formerly called magnesium silicate perovskite), and ferropericlase. Garnet also becomes unstable at or slightly below the base of the transition zone.

The lower mantle is composed primarily of bridgmanite and ferropericlase, with minor amounts of calcium perovskite, calcium-ferrite structured oxide, and stishovite

Stishovite is an extremely hard, dense tetragonal form ( polymorph) of silicon dioxide. It is very rare on the Earth's surface; however, it may be a predominant form of silicon dioxide in the Earth, especially in the lower mantle.

Stishovite w ...

. In the lowermost ~ of the mantle, bridgmanite isochemically transforms into post-perovskite.

Possible remnants of Theia collision

Seismic images of Earth’s interior have revealed in the lowermost mantle two continent-sized anomalies with low seismic velocities. These zones are denser and likely compositionally different from the surrounding mantle. These anomalies may represent buried relics ofTheia

Theia (; , also rendered Thea or Thia), also called Euryphaessa (, "wide-shining"), is one of the twelve Titans, the children of the earth goddess Gaia and the sky god Uranus in Greek mythology. She is the Greek goddess of sight and vision, an ...

mantle material remaining after the Moon-forming event proposed in the Giant-impact hypothesis

The giant-impact hypothesis, sometimes called the Theia Impact, is an astrogeology hypothesis for the formation of the Moon first proposed in 1946 by Canadian geologist Reginald Daly. The hypothesis suggests that the Early Earth collided wi ...

.

Composition

The chemical composition of the mantle is difficult to determine with a high degree of certainty because it is largely inaccessible. Mantle rocks can become accessible in rare circumstances. For example, rare exposures of mantle rocks occur inophiolite

An ophiolite is a section of Earth's oceanic crust and the underlying upper mantle (Earth), upper mantle that has been uplifted and exposed, and often emplaced onto continental crustal rocks.

The Greek word ὄφις, ''ophis'' (''snake'') is ...

s, where sections of oceanic lithosphere have been obducted onto a continent. Another example is when mantle rocks are sampled as xenolith

A xenolith ("foreign rock") is a rock (geology), rock fragment (Country rock (geology), country rock) that becomes enveloped in a larger rock during the latter's development and solidification. In geology, the term ''xenolith'' is almost exclusi ...

s within basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

s or kimberlite

Kimberlite is an igneous rock and a rare variant of peridotite. It is most commonly known as the main host matrix for diamonds. It is named after the town of Kimberley, Northern Cape, Kimberley in South Africa, where the discovery of an 83.5-Car ...

s, when fragments of mantle rock become embedded in these rocks during their formation.

Most estimates of the mantle composition are based on rocks that sample only the uppermost mantle. There is debate as to whether the rest of the mantle, especially the lower mantle, has the same bulk composition. The mantle's composition has changed through the Earth's history due to the extraction of magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma (sometimes colloquially but incorrectly referred to as ''lava'') is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also ...

that solidified to form oceanic crust and continental crust.

It has also been proposed in a 2018 study that an exotic form of water known as ice VII

Variations in pressure and temperature give rise to different phases of ice, which have varying properties and molecular geometries. Currently, twenty-one phases, including both crystalline and amorphous ices have been observed. In modern histor ...

can form from supercritical water in the mantle when diamonds containing pressurized water bubbles move upward, cooling the water to the conditions needed for ice VII to form.

Temperature and pressure

In the mantle, temperatures range from approximately 500kelvin

The kelvin (symbol: K) is the base unit for temperature in the International System of Units (SI). The Kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale that starts at the lowest possible temperature (absolute zero), taken to be 0 K. By de ...

(K) (230 °C; 440 °F) at the upper boundary with the crust to approximately 4,200 K (3,900 °C; 7,100 °F) at the core-mantle boundary. The temperature of the mantle increases rapidly in the thermal boundary layers

In physics and fluid mechanics, a boundary layer is the thin layer of fluid in the immediate vicinity of a bounding surface formed by the fluid flowing along the surface. The fluid's interaction with the wall induces a no-slip boundary condi ...

at the top and bottom of the mantle, and increases gradually through the interior of the mantle. Although the higher temperatures far exceed the melting point

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state of matter, state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase (matter), phase exist in Thermodynamic equilib ...

s of the mantle rocks at the surface (about 1,500 K (1,200 °C; 2,200 °F) for representative peridotite), the mantle is almost exclusively solid. The enormous lithostatic pressure

Pressure is force magnitude applied over an area. Overburden pressure is a geology term that denotes the pressure caused by the weight of the overlying layers of material at a specific depth under the earth's surface. Overburden pressure is also ca ...

exerted on the mantle prevents melting, because the temperature at which melting begins (the solidus) increases with pressure.

The pressure in the mantle increases from a few hundred megapascals (GPa) at the Moho to at the core-mantle boundary.

Movement

Because of the temperature difference between the Earth's surface and outer core and the ability of the crystalline rocks at high pressure and temperature to undergo slow, creeping, viscous-like deformation over millions of years, there is a

Because of the temperature difference between the Earth's surface and outer core and the ability of the crystalline rocks at high pressure and temperature to undergo slow, creeping, viscous-like deformation over millions of years, there is a convective

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously through the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the convec ...

material circulation in the mantle. Hot material rises (in a mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic ho ...

) while cooler (and heavier) material sinks downward. Downward motion of material occurs at convergent plate boundaries called subduction zones. Locations on the surface that lie over plumes are predicted to have high elevation (because of the buoyancy of the hotter, less-dense plume beneath) and to exhibit hot spot volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism, volcanicity, or volcanic activity is the phenomenon where solids, liquids, gases, and their mixtures erupt to the surface of a solid-surface astronomical body such as a planet or a moon. It is caused by the presence of a he ...

. The volcanism often attributed to deep mantle plumes is alternatively explained by passive extension of the crust, permitting magma to leak to the surface: the plate hypothesis.

The convection

Convection is single or Multiphase flow, multiphase fluid flow that occurs Spontaneous process, spontaneously through the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoy ...

of the Earth's mantle is a chaotic process (in the sense of fluid dynamics

In physics, physical chemistry and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids – liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including (the study of air and other gases in motion ...

), which is thought to be an integral part of the motion of plates. Plate motion should not be confused with continental drift

Continental drift is a highly supported scientific theory, originating in the early 20th century, that Earth's continents move or drift relative to each other over geologic time. The theory of continental drift has since been validated and inc ...

which applies purely to the movement of the crustal components of the continents. The movements of the lithosphere and the underlying mantle are coupled since descending lithosphere is an essential component of convection in the mantle. The observed continental drift is a complicated relationship between the forces causing oceanic lithosphere to sink and the movements within Earth's mantle.

Although there is a tendency to larger viscosity at greater depth, this relation is far from linear and shows layers with dramatically decreased viscosity, in particular in the upper mantle and at the boundary with the core.Walzer, Uwe; Hendel, Roland and Baumgardner, JohnMantle Viscosity and the Thickness of the Convective Downwellings

igw.uni-jena.de The mantle within about above the core–mantle boundary appears to have distinctly different seismic properties than the mantle at slightly shallower depths; this unusual mantle region just above the core is called D ("D double-prime"), a nomenclature introduced over 50 years ago by the geophysicist Keith Bullen. D may consist of material from subducted slabs that descended and came to rest at the core–mantle boundary or from a new mineral polymorph discovered in perovskite called post-perovskite. Earthquakes at shallow depths are a result of faulting; however, below about the hot, high pressure conditions ought to inhibit further seismicity. The mantle is considered to be viscous and incapable of brittle faulting. However, in subduction zones, earthquakes are observed down to . A number of mechanisms have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, including dehydration, thermal runaway, and phase change. The geothermal gradient can be lowered where cool material from the surface sinks downward, increasing the strength of the surrounding mantle, and allowing earthquakes to occur down to a depth of between and . The pressure at the bottom of the mantle is ~. Pressure increases as depth increases, since the material beneath has to support the weight of all the material above it. The entire mantle, however, is thought to deform like a fluid on long timescales, with permanent plastic deformation accommodated by the movement of point, line, and/or planar defects through the solid crystals composing the mantle. Estimates for the viscosity of the upper mantle range between and pascal seconds (Pa·s) depending on depth, temperature, composition, state of stress, and numerous other factors. Thus, the upper mantle can only flow very slowly. However, when large forces are applied to the uppermost mantle it can become weaker, and this effect is thought to be important in allowing the formation of tectonic plate boundaries.

Exploration

Exploration of the mantle is generally conducted at the seabed rather than on land because of the relative thinness of the oceanic crust as compared to the significantly thicker continental crust. The first attempt at mantle exploration, known asProject Mohole

Project Mohole was an attempt in the early 1960s to drill through the Earth's Crust (geology), crust to obtain samples of the Mohorovičić discontinuity, or Moho, the boundary between the Earth's Crust (geology), crust and Mantle (geology), m ...

, was abandoned in 1966 after repeated failures and cost over-runs. The deepest penetration was approximately . In 2005 an oceanic borehole reached below the sea floor from the ocean drilling vessel '' JOIDES Resolution''.

More successful was the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) that operated from 1968 to 1983. Coordinated by Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) is the center for oceanography and Earth science at the University of California, San Diego. Its main campus is located in La Jolla, with additional facilities in Point Loma.

Founded in 1903 and incorpo ...

at the University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego in communications material, formerly and colloquially UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California, United States. Es ...

, DSDP provided crucial data to support the seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading, or seafloor spread, is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener ...

hypothesis and helped to prove the theory of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

. '' Glomar Challenger'' conducted the drilling operations. DSDP was the first of three international scientific ocean drilling programs that have operated over more than 40 years. Scientific planning was conducted under the auspices of the Joint Oceanographic Institutions for Deep Earth Sampling (JOIDES), whose advisory group consisted of 250 distinguished scientists from academic institutions, government agencies, and private industry from all over the world. The Ocean Drilling Program

The Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) was part of an international project to explore and study the composition and structure of Earth's oceanic basins. This collaborative effort spanned multiple decades and produced comprehensive data that improved un ...

(ODP) continued exploration from 1985 to 2003 when it was replaced by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP).

On 5 March 2007, a team of scientists on board the RRS ''James Cook'' embarked on a voyage to an area of the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

seafloor where the mantle lies exposed without any crust covering, midway between the Cape Verde Islands

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

and the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

. The exposed site lies approximately three kilometres beneath the ocean surface and covers thousands of square kilometres.

A relatively difficult attempt to retrieve samples from the Earth's mantle was scheduled for later in 2007. The Chikyu Hakken mission attempted to use the Japanese vessel ''Chikyū

is a Japanese scientific drilling ship built for the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP). The vessel is designed to ultimately drill beneath the seabed, where the Earth's crust is much thinner, and into the Earth's mantle, deeper than an ...

'' to drill up to below the seabed. This is nearly three times as deep as preceding oceanic drillings.

A novel method of exploring the uppermost few hundred kilometres of the Earth was proposed in 2005, consisting of a small, dense, heat-generating probe which melts its way down through the crust and mantle while its position and progress are tracked by acoustic signals generated in the rocks. The probe consists of an outer sphere of tungsten

Tungsten (also called wolfram) is a chemical element; it has symbol W and atomic number 74. It is a metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively in compounds with other elements. It was identified as a distinct element in 1781 and first ...

about one metre in diameter with a cobalt-60

Cobalt-60 (Co) is a synthetic radioactive isotope of cobalt with a half-life of 5.2714 years. It is produced artificially in nuclear reactors. Deliberate industrial production depends on neutron activation of bulk samples of the monoisotop ...

interior acting as a radioactive heat source. It was calculated that such a probe will reach the oceanic ''Moho'' in less than 6 months and attain minimum depths of well over in a few decades beneath both oceanic and continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' (album), an album by Saint Etienne

* Continen ...

lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the lithospheric mantle, the topmost portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time ...

.

Exploration can also be aided through computer simulations of the evolution of the mantle. In 2009, a supercomputer

A supercomputer is a type of computer with a high level of performance as compared to a general-purpose computer. The performance of a supercomputer is commonly measured in floating-point operations per second (FLOPS) instead of million instruc ...

application provided new insight into the distribution of mineral deposits, especially isotopes of iron, from when the mantle developed 4.5 billion years ago.University of California – Davis (2009-06-15)Super-computer Provides First Glimpse Of Earth's Early Magma Interior

ScienceDaily

''ScienceDaily'' is an American website launched in 1995 that aggregates press releases and publishes lightly edited press releases (a practice called churnalism) about science, similar to Phys.org and EurekAlert!.

History

The site was f ...

. Retrieved on 2009-06-16.

In 2023, JOIDES Resolution recovered cores of what appeared to be rock from the upper mantle after drilling only a few hundred meters into the Atlantis Massif

The Atlantis Massif is a prominent undersea massif in the North Atlantic Ocean. It is a dome-shaped region approximately across and rising about from the sea floor. It is located at approximately 30°8′N latitude 42°8′W longitude; just ea ...

. The borehole reached a maximum depth of 1,268 meters and recovered 886 meters of rock samples consisting of primarily peridotite

Peridotite ( ) is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock consisting mostly of the silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium (Mg2+), reflecting the high pr ...

. There is debate over the extent to which the samples represent the upper mantle with some arguing the effects of seawater on the samples situates them as examples of deep lower crust. However, the samples offer a much closer analogue to mantle rock than magmatic xenoliths as the sampled rock never melted into magma or recrystallized.

See also

*Internal structure of Earth

The internal structure of Earth are the layers of the Earth, excluding its atmosphere and hydrosphere. The structure consists of an outer silicate solid crust, a highly viscous asthenosphere, and solid mantle, a liquid outer core whose flow ge ...

* Large low-shear-velocity provinces

Large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs), also called large low-velocity provinces (LLVPs) or superplumes, are characteristic structures of parts of the lowermost mantle, the region surrounding the outer core deep inside the Earth. These provi ...

* Mantle (geology)

A mantle is a layer inside a planetary body bounded below by a Planetary core, core and above by a Crust (geology), crust. Mantles are made of Rock (geology), rock or Volatile (astrogeology), ices, and are generally the largest and most massive l ...

– a wider description of the mantle of Earth and other astronomical bodies

* Seismic tomography – technique for imaging the subsurface of Earth using seismic waves

References

External links

The Biggest Dig: Japan builds a ship to drill to the earth's mantle

– ''Scientific American'' (September 2005)

Information on the Mohole Project

{{Authority control Structure of the Earth