Dürnkrut on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle on the Marchfeld (''i.e. Morava Field''; ; ; ); at Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen took place on 26 August 1278 and was a decisive event for the history of

The death of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in 1250 and subsequently his son

The death of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in 1250 and subsequently his son

Meanwhile, Rudolph was gathering allies and preparing for battle. He achieved two of these alliances through the classic Habsburg style – marriage. First, he married his son Albert to

Meanwhile, Rudolph was gathering allies and preparing for battle. He achieved two of these alliances through the classic Habsburg style – marriage. First, he married his son Albert to

Bellum.cz – Battle on the Marchfeld 26 August 1278

{{Authority control 1278 in Europe Marchfeld 13th century in Hungary 13th century in Bohemia Lower Austria Marchfeld Marchfeld Marchfeld Marchfeld Conflicts in 1278 Ottokar II of Bohemia Battles involving Germany Battles involving the Holy Roman Empire

Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

for the following centuries. The opponents were a Bohemian (Czech) army led by the Přemyslid king Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II (; , in Městec Králové, Bohemia – 26 August 1278, in Dürnkrut, Austria, Dürnkrut, Lower Austria), the Iron and Golden King, was a member of the Přemyslid dynasty who reigned as King of Bohemia from 1253 until his death in 1278 ...

and the German army under the German king Rudolph I of Habsburg in alliance with King Ladislaus IV of Hungary

Ladislaus IV (, , ; 5 August 1262 – 10 July 1290), also known as Ladislaus the Cuman, was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1272 to 1290. His mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of a chieftain from the pagan Cumans who had settled in Hung ...

. With 15,300 mounted troops, it was one of the largest cavalry battles in Central Europe during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. The Hungarian cavalry played a significant role in the outcome of the battle.

King Ottokar II of Bohemia expanded his territories considerably from 1250 to 1273, but suffered a devastating defeat in November 1276, when the newly elected German king Rudolph I of Habsburg imposed the Imperial ban

The imperial ban () was a form of outlawry in the Holy Roman Empire. At different times, it could be declared by the Holy Roman Emperor, by the Imperial Diet, or by courts like the League of the Holy Court (''Vehmgericht'') or the '' Reichskammerg ...

on Ottokar, declaring him an outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them. ...

and took over Ottokar's holdings in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, Carinthia

Carinthia ( ; ; ) is the southernmost and least densely populated States of Austria, Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The Lake Wolayer is a mountain lake on the Carinthian side of the Carnic Main ...

, Carniola

Carniola ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region that comprised parts of present-day Slovenia. Although as a whole it does not exist anymore, Slovenes living within the former borders of the region still tend to identify with its traditional parts Upp ...

, and Styria

Styria ( ; ; ; ) is an Austrian Federal states of Austria, state in the southeast of the country. With an area of approximately , Styria is Austria's second largest state, after Lower Austria. It is bordered to the south by Slovenia, and cloc ...

. Ottokar was reduced to his possessions in Bohemia and Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

, but was determined to regain his dominions, power, and influence. In 1278 he invaded Austria, where parts of the local population, especially in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, resented Habsburg rule. Rudolf allied himself with King Ladislaus IV of Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

and mustered forces for a decisive confrontation.

Ottokar abandoned his siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

of Laa an der Thaya

Laa an der Thaya is a town in the Mistelbach District of Lower Austria in Austria, near the Czech Republic, Czech border. The population in 2016 was 6,224.

Geography

The town is located in the northern Weinviertel region, near the Thaya river, ...

and advanced to meet the allies near Dürnkrut, north of Vienna. Both armies were composed purely of cavalry and were divided into three divisions that attacked the enemy piecemeal. In the first phase of the battle, the Cuman

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Rus' chronicles, as " ...

horse archers in the Hungarian army outflanked and distracted the Bohemian left flank by launching arrow

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers c ...

s while the Hungarian light cavalry crashed into the Bohemians, driving them from the field. In the second phase, a great collision of knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

s and heavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry was a class of cavalry intended to deliver a battlefield charge and also to act as a Military reserve, tactical reserve; they are also often termed ''shock cavalry''. Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the re ...

took place in the center, with Rudolf's forces being driven back. Rudolf's third division, led by the king personally, attacked and halted Ottokar's charge. Rudolf was unhorsed in the melee and nearly killed. At a decisive moment, a German cavalry force of 200 riders, commanded by Ulrich von Kapellen, ambush

An ambush is a surprise attack carried out by people lying in wait in a concealed position. The concealed position itself or the concealed person(s) may also be called an "". Ambushes as a basic military tactics, fighting tactic of soldi ...

ed and attacked the Bohemian right flank from the rear. Assailed from two directions at once, Ottokar's army disintegrated into a rout, and Ottokar himself was killed in the confusion and slaughter. The Cumans pursued and killed the fleeing Bohemians with impunity.

The battle marked the beginning of the ascendancy of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

in Austria and Central Europe. The influence of the Přemyslid kings of Bohemia was diminished and restricted to their inheritance in Bohemia and Moravia.

Background

The death of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in 1250 and subsequently his son

The death of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in 1250 and subsequently his son Conrad IV of Germany

Conrad (25 April 1228 – 21 May 1254), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was the only son of Emperor Frederick II from his second marriage with Queen Isabella II of Jerusalem. He inherited the title of King of Jerusalem (as Conrad II) u ...

, created a grave crisis for the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, as in the following decades several nobles were elected as '' Rex Romanorum'' and Emperor-to-be, none of whom were able to gain actual governing power upon the Emperor's death in 1250. That same year, Ottokar II, son of King Wenceslaus I of Bohemia

Wenceslaus I (; c. 1205 – 23 September 1253), called One-Eyed, was King of Bohemia from 1230 to 1253.

Wenceslaus was a son of Ottokar I of Bohemia and his second wife Constance of Hungary.

Marriage and children

In 1224, Wenceslaus married ...

, moved into the princeless Duchies of Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

and Styria

Styria ( ; ; ; ) is an Austrian Federal states of Austria, state in the southeast of the country. With an area of approximately , Styria is Austria's second largest state, after Lower Austria. It is bordered to the south by Slovenia, and cloc ...

. The last Babenberg duke Frederick II of Austria had been killed at the 1246 Battle of the Leitha River, in a border conflict he had picked with King Béla IV of Hungary

Béla IV (1206 – 3 May 1270) was King of Hungary and King of Croatia, Croatia between 1235 and 1270, and Duke of Styria from 1254 to 1258. As the oldest son of Andrew II of Hungary, King Andrew II, he was crowned upon the initiative of a group ...

. Ottokar II gained the support of the local nobility and was proclaimed Austrian and Styrian duke by the estates one year later.

In 1253, Ottokar II became Bohemian king upon the death of his father; the concentration of power on the western Hungarian border was viewed with suspicion by King Béla IV, who campaigned against Austria and Styria but was finally defeated at the 1260 Battle of Kressenbrunn. In 1268 Ottokar signed a contract of inheritance with Ulrich III, the last Carinthian duke of the House of Sponheim

The House of Sponheim or Spanheim was a medieval Germans, German noble family, which originated in Rhenish Franconia. They were Imperial immediacy, immediate Counts of County of Sponheim, Sponheim until 1437 and Dukes of Duchy of Carinthia, Carint ...

, and thus acquired Carinthia including the March of Carniola

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Its length is 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of March. The March equinox on the 20 or 21 ...

and the Windic March one year later. At the height of his power he aimed at the Imperial crown, but the Princes-Electors (''Kurfürsten''), distrustful of his steep rise, elected the "poor Swabia

Swabia ; , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of Swabia, one of ...

n count" Rudolph of Habsburg King of the Romans on 29 September 1273.

Prelude

As the election had taken place in his absence, Ottokar did not acknowledge Rudolph as King. Rudolph himself had promised to regain the "alienated" territories which had to be conferred by the Imperial power with consent of the Prince-electors. He claimed the Austrian and Carinthian territories for the Empire and summoned Ottokar to the 1275 '' Reichstag'' atWürzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is, after Nuremberg and Fürth, the Franconia#Towns and cities, third-largest city in Franconia located in the north of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Lower Franconia. It sp ...

. By not appearing before the Diet, Ottokar set the events of his demise in motion. He was placed under the Imperial ban

The imperial ban () was a form of outlawry in the Holy Roman Empire. At different times, it could be declared by the Holy Roman Emperor, by the Imperial Diet, or by courts like the League of the Holy Court (''Vehmgericht'') or the '' Reichskammerg ...

and had all his territorial rights revoked, including even his Bohemian inheritance.

Meanwhile, Rudolph was gathering allies and preparing for battle. He achieved two of these alliances through the classic Habsburg style – marriage. First, he married his son Albert to

Meanwhile, Rudolph was gathering allies and preparing for battle. He achieved two of these alliances through the classic Habsburg style – marriage. First, he married his son Albert to Elisabeth of Gorizia-Tyrol

Elisabeth of Carinthia (also known as Elisabeth of Tyrol; – 28 October 1312), was a List of Austrian consorts, Duchess of Austria from 1282 and Queen of Germany from 1298 until 1308, by marriage to King Albert I of Germany, Albert I of the Ho ...

. In return, her father Count Meinhard II of Gorizia-Tyrol received the Duchy of Carinthia as a fief. Second, he established an — unstable — alliance with Duke Henry I of Lower Bavaria by offering Rudolph's daughter Katharina as wife for the Duke's son, Otto

Otto is a masculine German given name and a surname. It originates as an Old High German short form (variants '' Audo'', '' Odo'', '' Udo'') of Germanic names beginning in ''aud-'', an element meaning "wealth, prosperity".

The name is recorded fr ...

, in addition to the region of present-day Upper Austria

Upper Austria ( ; ; ) is one of the nine States of Austria, states of Austria. Its capital is Linz. Upper Austria borders Germany and the Czech Republic, as well as the other Austrian states of Lower Austria, Styria, and Salzburg (state), Salzbur ...

as a pledge for her dowry. He also concluded an alliance with King Ladislaus IV of Hungary

Ladislaus IV (, , ; 5 August 1262 – 10 July 1290), also known as Ladislaus the Cuman, was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1272 to 1290. His mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of a chieftain from the pagan Cumans who had settled in Hung ...

, who intended to settle old scores with Ottokar.

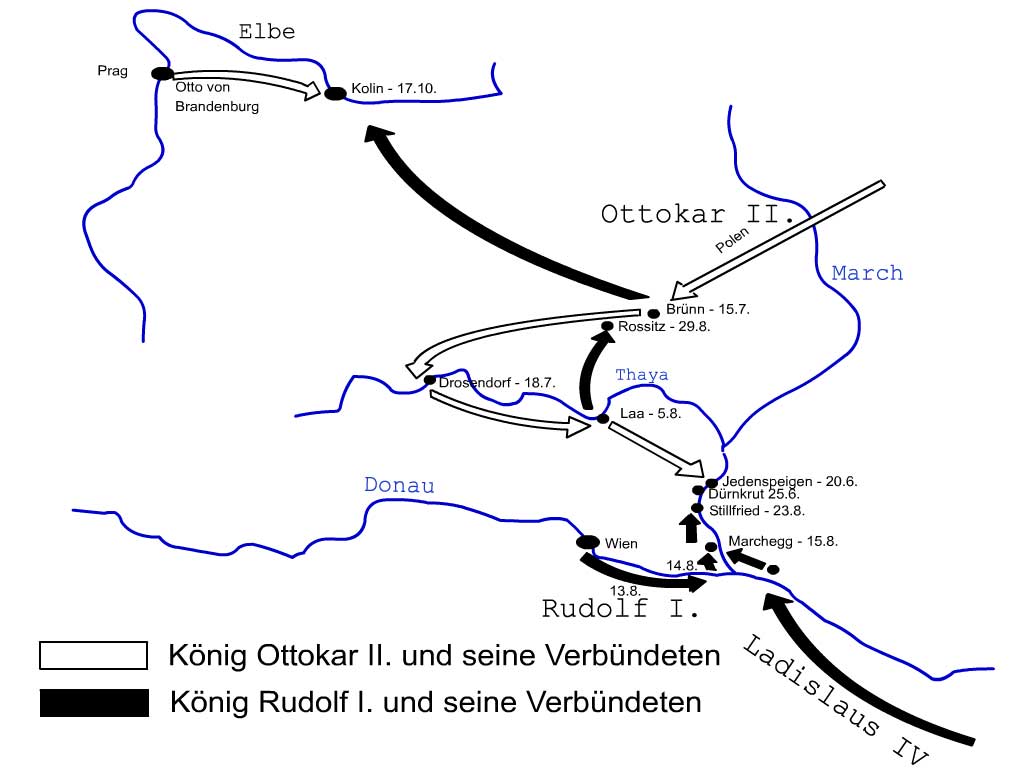

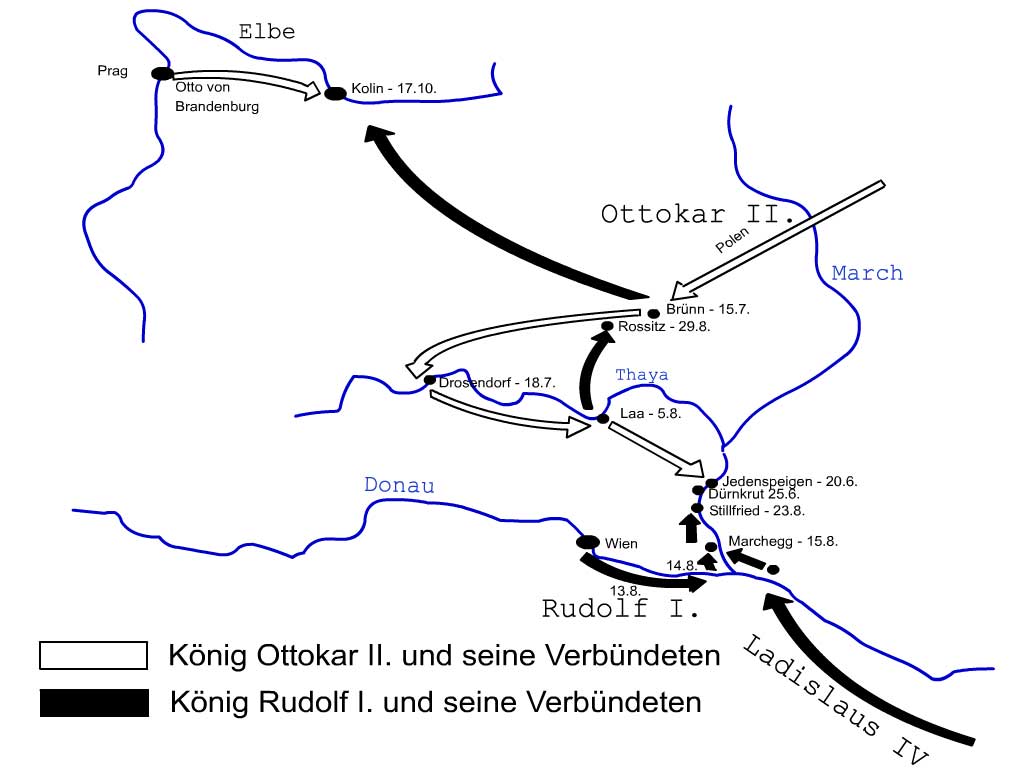

Rudolph, so strengthened, besieged Ottokar at the Austrian capital Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

in 1276. Ottokar was forced to surrender and to renounce all his acquisitions, receiving only Bohemia and Moravia as a fief from King Rudolph. Heavily deprived by this, he was determined to regain his territories and contracted an alliance with the Ascanian Margraves of Brandenburg and the Polish princes. In 1278 he campaigned against Austria, supported by Duke Henry I of Lower Bavaria, who had switched sides. Ottokar first laid siege to the towns of Drosendorf and Laa an der Thaya

Laa an der Thaya is a town in the Mistelbach District of Lower Austria in Austria, near the Czech Republic, Czech border. The population in 2016 was 6,224.

Geography

The town is located in the northern Weinviertel region, near the Thaya river, ...

near the Austrian border, while Rudolph decided to leave Vienna and to face the Bohemian army in open battle in the Morava basin north of the capital, where the Cuman cavalry of King Ladislaus could easily join his forces.

Opposing forces

Ottakar fielded 6,000 cavalry, of which 1,000 were heavily armed and armored and 5,000 lightly equipped riders. Ottokar's heavy cavalry rode armored horses. About one third of Ottakar’s knights were Poles from Silesia, Greater Poland and Lesser Poland. Rudolf had 300 heavy cavalry and 4,000 light cavalry, of which an indeterminate number were Hungarians. Rudolf's force included a force of 5,000 Cuman horse archers.Battle

Surprised by Rudolph's maneuver, Ottokar quickly abandoned the siege at Laa, marched southwards, and on August 26 met the united German and Hungarian forces near Dürnkrut. When he arrived his enemies had already taken the opportunity to explore the topography of the future battleground. From the early morning, the left wing of the advancing Bohemian troops were embroiled in impetuous attacks by the Cuman forces, which the heavily armed knights could not ward off. Nevertheless, as the main armies collided and the battle wore on, Ottokar's outnumbering cavalry seemed to gain the upper hand, when even Rudolph's horse was stabbed under him and the 60-year-old narrowly escaped with his life, rescued by his liensmen. After three hours of continuous fighting on a hot summer day, Ottokar's knights in their heavy armour were suffering from heat exhaustion and were not able to move. At noon Rudolph ordered a fresh heavy cavalry regiment he had concealed behind nearby hills and woods to attack the right flank of Ottokar's troops. Such ambushes were commonly regarded as dishonourable in medieval warfare and Rudolph's commander Ulrich von Kapellen apologized to his own men in advance. Nevertheless, the attack prevailed in splitting and stampeding the Bohemian troops. Ottokar became aware of the surprise attack and tried to lead a remaining reserve contingent in the rear of von Kapellen's troops, a maneuver that was misinterpreted as arout

A rout is a Panic, panicked, disorderly and Military discipline, undisciplined withdrawal (military), retreat of troops from a battlefield, following a collapse in a given unit's discipline, command authority, unit cohesion and combat morale ...

by the Bohemian forces. The resulting collapse led to a complete victory for Rudolph and his allies. Ottokar's camp was plundered, and he himself was found slain on the battlefield.''The Land Between: A History of Slovenia'', ed. Oto Luthar, (Peter Lang GmbH, 2008), 128.

Aftermath

Rudolph, to demonstrate his victory, had Ottokar's body displayed in Vienna. The "poor count" from SwabianHabsburg Castle

Habsburg Castle (, ) is a medieval Swiss fortress located in what is now Habsburg, Switzerland, in the canton of Aargau, near the Aar River. At the time of its construction, the location was part of the Duchy of Swabia. Habsburg Castle is th ...

assured his possession of the Duchies of Austria and Styria, the heartland and foundation of the rise of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

. At the 1282 Diet of Augsburg

The diets of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such se ...

, he installed his sons Albert and Rudolf II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the H ...

as Austrian dukes; their descendants held the ducal dignity until 1918. However, in Bohemia, Rudolph acted cautiously and reached an agreement with the nobility and Ottokar's widow Kunigunda of Slavonia on the succession of her son Wenceslaus II to the throne. On the same occasion he reconciled with the Brandenburg margraves, ceding them the guardianship over the minor heir apparent. King Ladislaus IV exerted himself in the christianization

Christianization (or Christianisation) is a term for the specific type of change that occurs when someone or something has been or is being converted to Christianity. Christianization has, for the most part, spread through missions by individu ...

of the Cuman warriors, before he was assassinated in 1290.

Ottokar's son, the young king Wenceslaus II of Bohemia, turned out to be a capable ruler. In 1291 he acquired the Polish Seniorate Province

Seniorate Province, also known as the Senioral Province, was a district principality in the Duchy of Poland that was formed in 1138, following the fragmentation of the state.Kwiatkowski, Richard. The Country That Refused to Die: The Story of t ...

at Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

and was crowned King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

in 1300. He was even able to secure the Hungarian crown for his son Wenceslaus III, still a minor, who nevertheless was murdered in 1306, one year after his father's death, whereby the Přemyslid dynasty became extinct.

Casualties

No exact data on casualties is available, but Ottokar's losses were considerably higher than Rudolf's.In art and popular culture

The battle was depicted in art especially during the rise ofnationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

in the 19th century, when it was viewed as the example of a traditional co-operation between the Habsburg dynasty (Austria) and the Kingdom of Hungary, from one side, and the traditional tension between the Habsburg dynasty and Bohemia, from the Czech side.

The tragedy '' König Ottokars Glück und Ende'' written by Franz Grillparzer in 1823 is based on the rise and fall of king Ottokar II. The drama was originally inspired by the life of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, but Grillparzer, fearing Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a Germans, German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian ...

's censorship, chose to write the play about Ottokar, in whose story he found many parallels. It nevertheless was immediately forbidden and could not be performed until 1825. Grillparzer perpetuated the legend of Ottokar's wife, Margaret of Babenberg, unsuccessfully trying to reconcile the opponents on the eve of the battle. In fact, Margaret had died in 1266.

The opera ''The Brandenburgers in Bohemia

''The Brandenburgers in Bohemia'' () is a three-act opera, the first by Bedřich Smetana. The Czech libretto was written by Karel Sabina, and is based on events from Czech history. The work was composed in the years 1862–1863. Smetana and ...

'', by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana ( ; ; 2 March 1824 – 12 May 1884) was a Czech composer who pioneered the development of a musical style that became closely identified with his people's aspirations to a cultural and political "revival". He has been regarded ...

in 1863, was inspired by the battle and the following events.

See also

* Battle of Kressenbrunn * List of battles 601–1400 * Battle of RozgonyCitations

References

* * *Andreas Kusternig: 700 Jahre Schlacht bei Duernkrut und Jedenspeigen. Wien 1978. * * * *External links

Bellum.cz – Battle on the Marchfeld 26 August 1278

{{Authority control 1278 in Europe Marchfeld 13th century in Hungary 13th century in Bohemia Lower Austria Marchfeld Marchfeld Marchfeld Marchfeld Conflicts in 1278 Ottokar II of Bohemia Battles involving Germany Battles involving the Holy Roman Empire