Dún Dealgan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dundalk ( ; ) is the

Dundalk ( ; ) is the

Archaeological studies at Rockmarshall on the

Archaeological studies at Rockmarshall on the

Castle Roche was destroyed in 1315 by the armies of

Castle Roche was destroyed in 1315 by the armies of

In 1540, the Priory of St Leonard founded by Bertram de Verdun was surrendered to the Crown because of

In 1540, the Priory of St Leonard founded by Bertram de Verdun was surrendered to the Crown because of

The latter part of the 19th century was dominated by the

The latter part of the 19th century was dominated by the

There was no strategic military action in north Louth during the

There was no strategic military action in north Louth during the

The main part of the census town lies at sea level. Dún Dealgan Motte at Castletown is the highest point in the urban area at an elevation of . The municipal district includes the

The main part of the census town lies at sea level. Dún Dealgan Motte at Castletown is the highest point in the urban area at an elevation of . The municipal district includes the

Dundalk ( ; ) is the

Dundalk ( ; ) is the county town

In Great Britain and Ireland, a county town is usually the location of administrative or judicial functions within a county, and the place where public representatives are elected to parliament. Following the establishment of county councils in ...

of County Louth

County Louth ( ; ) is a coastal Counties of Ireland, county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. Louth is bordered by the counties of County Meath, Meath to the ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. The town is situated on the Castletown River

The Castletown River () is a river which flows through the town of Dundalk, County Louth, Ireland. It rises near Newtownhamilton, County Armagh, Northern Ireland, and is known as the Creggan River in its upper reaches. Its two main tributaries ...

, which flows into Dundalk Bay

Dundalk Bay () is a large (33 km2), exposed estuary on the east coast of Ireland.

The inner bay is shallow, sandy and intertidal, though it slopes into a deeper area 2 km from the transitional water boundary.Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

and Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

, close to and south of the border with Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

. It is surrounded by several townlands and villages that form the wider Dundalk Municipal District. It is the seventh largest urban area in Ireland, with a population of 43,112 as of the 2022 census.

Dundalk has been inhabited since the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

period. It was established as a Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 9th and 10th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norma ...

stronghold in the 12th century following the Norman invasion of Ireland

The Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland took place during the late 12th century, when Anglo-Normans gradually conquered and acquired large swathes of land in Ireland over which the monarchs of England then claimed sovereignty. The Anglo-Normans ...

, and became the northernmost outpost of The Pale

The Pale ( Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast s ...

in the Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

. Located where the northernmost point of the province of Leinster

Leinster ( ; or ) is one of the four provinces of Ireland, in the southeast of Ireland.

The modern province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige, which existed during Gaelic Ireland. Following the 12th-century ...

meets the province of Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

, the town came to be known as the "Gap of the North". The modern street layout dates from the early 18th century and owes its form to James Hamilton (later 1st Earl of Clanbrassil). The legends of the mythical warrior hero Cú Chulainn

Cú Chulainn ( ), is an Irish warrior hero and demigod in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology, as well as in Scottish and Manx folklore. He is believed to be an incarnation of the Irish god Lugh, who is also his father. His mother is the ...

are set in this district, and the motto on the town's coat of arms is ("I gave birth to brave Cú Chulainn").

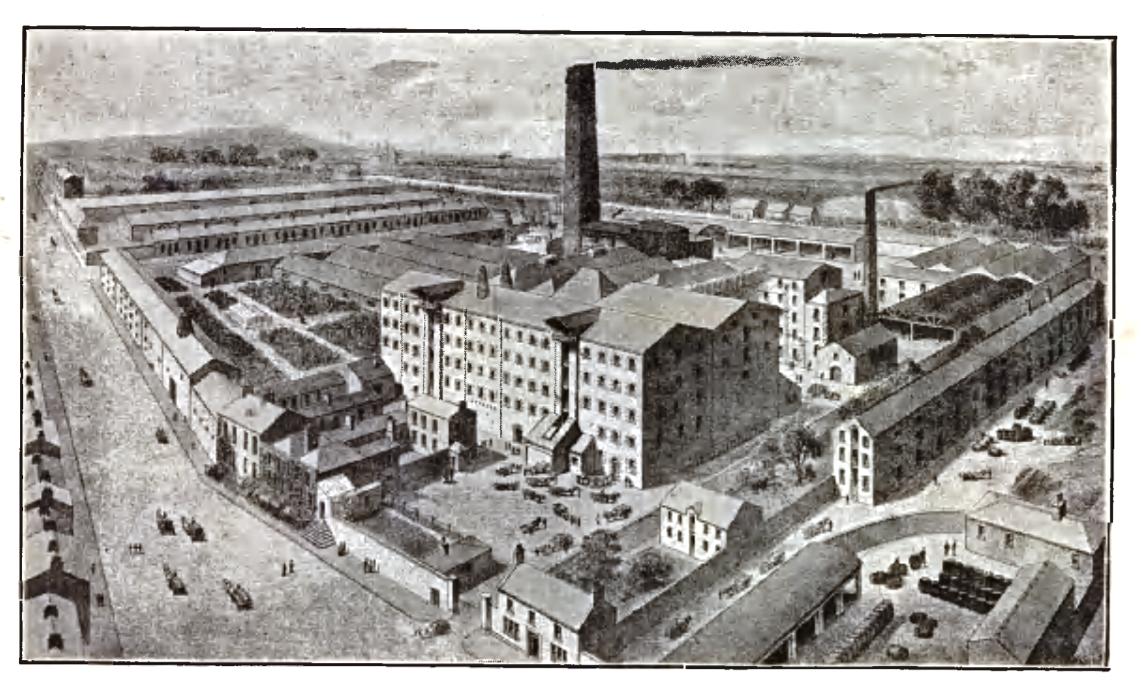

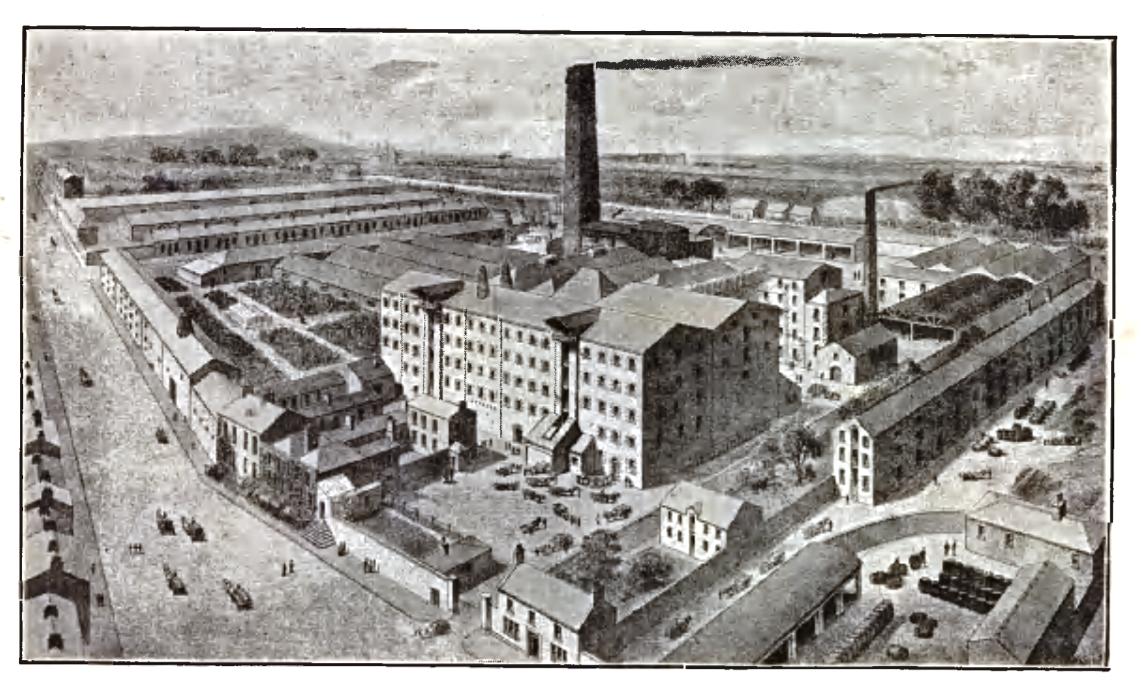

The town developed brewing, distilling, tobacco, textile, and engineering industries during the 19th century. It became prosperous and its population grew as it became an important manufacturing and trading centre, both as a hub on the Great Northern Railway (Ireland)

The Great Northern Railway (Ireland) (GNR(I), GNRI or simply GNR) was an Irish gauge () railway company in Ireland. It was formed in 1876 by a merger of the Irish North Western Railway (INW), Northern Railway of Ireland, and Ulster Railway. Th ...

network and with its maritime link to Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

from the Port of Dundalk. It suffered from high unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work du ...

and urban decay

Urban decay (also known as urban rot, urban death or urban blight) is the sociological process by which a previously functioning city, or part of a city, falls into disrepair and decrepitude. There is no single process that leads to urban decay. ...

after these industries closed or were scaled back, both in the aftermath of the Partition of Ireland

The Partition of Ireland () was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland (the area today known as the R ...

in 1921 and following the accession of Ireland to the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

in 1973. New industries were established in the early part of the 21st century, including pharmaceutical, technology, financial services, and specialist foods.

There is one third-level education institute, Dundalk Institute of Technology

Dundalk Institute of Technology (DkIT; ) is an institute of technology, located in Dundalk, Ireland. Established as the Dundalk Regional Technical College, students were first enrolled in the college in 1971 and it was later re-defined as an i ...

. The largest theatre in the town, ''An Táin'' Arts Centre (named after the epic of Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths indigenous to the island of Ireland. It was originally Oral tradition, passed down orally in the Prehistoric Ireland, prehistoric era. In the History of Ireland (795–1169), early medieval era, myths were ...

), is housed in Dundalk Town Hall, and the restored buildings of the nearby former Dundalk Distillery house both the County Museum Dundalk and the Louth County Library. Sporting clubs include Dundalk Football Club (who play at Oriel Park

Oriel Park is a UEFA Category 2 football stadium located on the Carrickmacross Road in Dundalk, Ireland. The stadium is the home ground of Dundalk Football Club and is owned and operated by the club on land that has been leased from the Casey ...

), Dundalk Rugby Club, Dundalk Golf Club, and several clubs competing in Gaelic games

Gaelic games () are a set of sports played worldwide, though they are particularly popular in Ireland, where they originated. They include Gaelic football, hurling, Gaelic handball and rounders. Football and hurling, the most popular of the s ...

. Dundalk Stadium

Dundalk Stadium is a horse and greyhound racing venue in Ireland. It is located to the north of Dundalk in County Louth.

The total build cost €35million with a modern grandstand, elevated viewing areas, restaurant and bars.

Horse racing

T ...

is a horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

and greyhound racing

Greyhound racing is an organized, competitive sport in which greyhounds are raced around an oval track. The sport originates from Hare coursing, coursing. Track racing uses an artificial lure (usually a form of windsock) that travels ahead of th ...

venue and is Ireland's only all-weather horse racing track.

History

Toponymy

Dundalk is ananglicisation

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

of that was adopted by the first Norman settlers of the area in the 12th century. It means "the fort of Dealgan" (''Dún

A dun is an ancient or medieval fort. In Great Britain and Ireland it is mainly a kind of hillfort and also a kind of Atlantic roundhouse.

Etymology

The term comes from Irish ''dún'' or Scottish Gaelic ''dùn'' (meaning "fort"), and is c ...

'' being a type of medieval fort and ''Delga'' being the name of a mythical Fir Bolg

In medieval Irish myth, the Fir Bolg (also spelt Firbolg and Fir Bholg) are the fourth group of people to settle in Ireland. They are descended from the Muintir Nemid, an earlier group who abandoned Ireland and went to different parts of Europe. ...

Chieftain). The site of ''Dún Dealgan'' is traditionally associated with the ringfort

Ringforts or ring forts are small circular fortification, fortified settlements built during the Bronze Age, Iron Age and early Middle Ages up to about the year 1000 AD. They are found in Northern Europe, especially in Ireland. There are ...

known to have existed at Castletown Mount before the arrival of the Normans. The first mention of Dundalk in historical sources appears in the ''Annals of Ulster

The ''Annals of Ulster'' () are annals of History of Ireland, medieval Ireland. The entries span the years from 431 AD to 1540 AD. The entries up to 1489 AD were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luin� ...

'', which record that Brian Boru

Brian Boru (; modern ; 23 April 1014) was the High King of Ireland from 1002 to 1014. He ended the domination of the High King of Ireland, High Kingship of Ireland by the Uí Néill, and is likely responsible for ending Vikings, Viking invasio ...

met the King of Ulster at "''Dún Delgain''" in 1002 to demand submission. 12th century versions of the ''Táin Bó Cúailnge

(Modern ; "the driving-off of the cows of Cooley"), commonly known as ''The Táin'' or less commonly as ''The Cattle Raid of Cooley'', is an epic from Irish mythology. It is often called "the Irish ''Iliad''", although like most other earl ...

'' feature "''Delga in Muirtheimne''". The manor house built by Bertram de Verdon at Castletown Mount on the site of the earlier settlement is referred to as the "''Castle of Dundalc''" in the 12th century records of the Gormanston Register.

Early history and legend

Archaeological studies at Rockmarshall on the

Archaeological studies at Rockmarshall on the Cooley peninsula

The Cooley Peninsula (, older ''Cúalṅge'') is a hilly peninsula in the north of County Louth on the east coast of Ireland; the peninsula includes the small town of Carlingford, the port of Greenore and the village of Omeath.

Geography

...

indicate that the Dundalk district was first inhabited circa 3700 BC during the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

period. Pre-Christian archaeological sites in the Dundalk Municipal District include the Proleek Dolmen

Proleek Dolmen is a dolmen (portal tomb) and national monument in County Louth, Ireland.

Location

Proleek Dolmen is northeast of Dundalk, on the west bank of the Ballymascanlan River. History

The dolmen dates to the Neolithic, around 3000 B ...

(a portal tomb

A dolmen, () or portal tomb, is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the Late Neolithic period (40003000 BCE) and ...

) in Ballymascanlon, which dates to around 3000 BC, the nearby "Giant's Grave" (a wedge-shaped gallery grave

A gallery grave is a form of megalithic tomb built primarily during the Neolithic Age in Europe in which the main gallery of the tomb is entered without first passing through an antechamber or hallway. There are at least four major types of ga ...

), Rockmarshall Court Tomb (a court cairn

The court cairn or court tomb is a megalithic type of chambered cairn or gallery grave. During the period, 3900–3500 BC, more than 390 court cairns were built in Ireland and over 100 in southwest Scotland. The Neolithic (New Stone Age) mon ...

), and Aghnaskeagh Cairns (a chambered cairn

A chambered cairn is a burial monument, usually constructed during the Neolithic, consisting of a sizeable (usually stone) chamber around and over which a cairn of stones was constructed. Some chambered cairns are also passage-graves. They are fo ...

and portal tomb).

The legends of Cú Chulainn

Cú Chulainn ( ), is an Irish warrior hero and demigod in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology, as well as in Scottish and Manx folklore. He is believed to be an incarnation of the Irish god Lugh, who is also his father. His mother is the ...

, including the ''Táin Bó Cúailnge'' (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), an epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film defined by the spectacular presentation of human drama on a grandiose scale

Epic(s) ...

of early Irish literature, are set in the first century AD, before the arrival of Christianity to Ireland. ''Clochafarmore

Clochafarmore (, meaning "stone of the great man") is a menhir (standing stone) and National Monument in County Louth, Ireland.

Location

Clochafarmore is located east-northeast of Knockbridge, Dundalk on the left bank of the River Fane.

Hi ...

'', the menhir

A menhir (; from Brittonic languages: ''maen'' or ''men'', "stone" and ''hir'' or ''hîr'', "long"), standing stone, orthostat, or lith is a large upright stone, emplaced in the ground by humans, typically dating from the European middle Br ...

that Cú Chulainn reputedly tied himself to before he died, is located to the west of the town, near Knockbridge

Knockbridge () is a village in County Louth, Ireland. 7 km south-west of Dundalk, it is in the townland of Ballinlough (''Baile an Locha'') in the historical barony of Dundalk Upper. As of the 2022 census, the village had a population of ...

.

Saint Brigid

Saint Brigid of Kildare or Saint Brigid of Ireland (; Classical Irish: ''Brighid''; ; ) is the patroness saint (or 'mother saint') of Ireland, and one of its three national saints along with Patrick and Columba. According to medieval Irish ...

is reputed to have been born in 451 AD in Faughart

Faughart or Fochart () is an area north of Dundalk in County Louth, Ireland. The Hill of Faughart is the site of early Christian church ruins and a medieval graveyard, as well as a shrine to Saint Brigid.

According to tradition, it was the birt ...

. A shrine to her is located at Faughart. St Brigid's Church in Kilcurry holds what worshippers believe is a relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains or personal effects of a saint or other person preserved for the purpose of veneration as a tangible memorial. Reli ...

of the saint, a fragment of her skull.

Most of what is recorded about the Dundalk area between the 5th century and the foundation of the town as a Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 9th and 10th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norma ...

stronghold in the 12th century comes from the ''Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' () or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' () are chronicles of Middle Ages, medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Genesis flood narrative, Deluge, dated as 2,242 Anno Mundi, years after crea ...

'' and the ''Annals of Tigernach

The ''Annals of Tigernach'' (Abbreviation, abbr. AT, ) are chronicles probably originating in Clonmacnoise, Ireland. The language is a mixture of Latin language, Latin and Old Irish, Old and Middle Irish.

Many of the pre-historic entries come f ...

'', which were both written hundreds of years after the events they record. According to the annals, the area that is now Dundalk was known as ''Magh Muirthemne'' (the Plain of the Dark Sea). It was bordered to the northeast by ''Cuailgne'' (Cooley) and to the south by the ''Ciannachta

The Ciannachta were a population group of early historic Ireland. They claimed descent from the legendary figure Tadc mac Céin. Modern research indicates Saint Cianán and his followers may have been the origin behind the tribal name as it is ...

''. It was ruled by a Cruthin

The Cruthin (; or ; ) were a people of early medieval Ireland. Their heartland was in Ulster and included parts of the present-day counties of Antrim, Down and Londonderry. They are also said to have lived in parts of Leinster and Connacht ...

kingdom known as ''Conaille Muirtheimne

Conaille Muirthemne was a Cruithin kingdom located in County Louth, Ireland, from before 688 to after 1107 approximately.

Overview

The Ulaid according to historian Francis John Byrne 'possibly still ruled directly in Louth as far as the Boyne i ...

'' (who were aligned to the ''Ulaid

(Old Irish, ) or (Irish language, Modern Irish, ) was a Gaelic Ireland, Gaelic Provinces of Ireland, over-kingdom in north-eastern Ireland during the Middle Ages made up of a confederation of dynastic groups. Alternative names include , which ...

'') in the early Christian period.

There are several references in the annals to battles fought in the district such as the 'Battle of Fochart' in 732, which are folklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

. Geoffrey Keating

Geoffrey Keating (; – ) was an Irish historian. He was born in County Tipperary, Ireland, and is buried in Tubrid Graveyard in the parish of Ballylooby-Duhill. He became a Catholic priest and a poet.

Biography

It was generally believed unt ...

's ''Foras Feasa ar Éirinn

''Foras Feasa ar Éirinn'' – literally 'Foundation of Knowledge on Ireland', but most often known in English as 'The History of Ireland' – is a narrative history of Ireland by Geoffrey Keating, written in Irish and completed .Bernadette Cun ...

'' recounts the mythical tale of a 10th-century naval battle in Dundalk Bay. Sitric, son of Turgesius

Turgesius (died 845) (also called Turgeis, Tuirgeis, Turges, and Thorgest) was a Viking chief active in Ireland during the 9th century. Turgesius Island, the principal island on Lough Lene, is named after him. It is not at all clear whether the na ...

and ruler of the ''Lochlann

In the modern Gaelic languages, () signifies Scandinavia or, more specifically, Norway. As such it is cognate with the Welsh name for Scandinavia, (). In both old Gaelic and old Welsh, such names literally mean 'land of lakes' or 'land of sw ...

aigh'' in Ireland, had offered Cellachán Caisil

Cellachán mac Buadacháin (died 954), called Cellachán Caisil, was King of Munster.

Biography

The son of Buadachán mac Lachtnai, he belonged to the Cashel branch of the Eóganachta kindred, the Eóganacht Chaisil. The last of his cognatic ...

, the King of Munster

The kings of Munster () ruled the Kingdom of Munster in Ireland from its establishment during the Irish Iron Age until the High Middle Ages. According to Gaelic traditional history, laid out in works such as the ''Book of Invasions'', the earli ...

, his sister in marriage. But it was a trick to take the king prisoner and he was captured and held hostage in Armagh. An army was raised in Munster and marched on Armagh to free the king, but Sitric retreated to Dundalk and moved his hostages to his ship in Dundalk Bay as the Munster army approached. A fleet from Munster commanded by the King of Desmond

The following is a list of monarchs of the Kingdom of Desmond. Most were of the MacCarthy Mór ("great MacCarthy"), the senior branch of the MacCarthy dynasty.

12th century MacCarthy

MacCarthy claimants

O'Brien claimants

MacCarthy

13th ...

, Failbhe Fion, attacked the Danes in the bay from the south. During the sea battle, Failbhe Fion boarded Sitric's ship and freed Cellachán, but was killed by Sitric who put Failbhe Fion's head on a pole. Failbhe Fion's second in command, Fingal, seized Sitric by the neck and jumped into the sea where they both drowned. Two more Irish captains each grabbed one of Sitric's two brothers and did the same, and the Danes were subsequently routed.

There is a high concentration of souterrains

''Souterrain'' (from French ', meaning "subterrain", is a name given by archaeologists to a type of underground structure associated mainly with the European Atlantic Iron Age.

These structures appear to have been brought northwards from Gaul d ...

in north Louth, particularly along the western periphery of the town including at Castletown Mount, which is evidence of settlements from early Christian Ireland

Early may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa, a city

* Early, Texas, a city

* Early Branch, a stream in Missouri

* Early County, Georgia

* Fort Early, Georgia, an early 19th century fort

Music

* Early B, stage name of Jamaican d ...

. This indicates that the area was regularly subject to raids and the discovery of a type of pottery known as 'souterrain ware', which has only been found in north Louth, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 552,261. It borders County Antrim to the ...

and County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, County Antrim, Antrim, ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, located within the historic Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the c ...

, suggests that these areas shared cultural ties separate from the rest of early historic Ireland. The number of souterrains drops significantly on crossing the River Fane to the south, indicating that the district was a border area between separate kingdoms.

Archaeological and historical research suggests that before the arrival of the Normans, the district was composed of rural settlements of ringforts

Ringforts or ring forts are small circular fortified settlements built during the Bronze Age, Iron Age and early Middle Ages up to about the year 1000 AD. They are found in Northern Europe, especially in Ireland. There are also many in S ...

located on the higher ground that surrounds the present-day town. There are references in the annals and folklore to a pre-Norman town located in the present-day Seatown area, east of the town centre. This area was alternatively called ''Traghbaile'' and later ''Sraidbhaile'' in Irish. These names could have derived from the folkloric tale of the death of Bailé Mac Buain—hence ''Traghbaile'', meaning 'Bailé's Strand', or ''Sraid Baile mac Buain'', meaning the street town of Bailé Mac Buain. Dundalk continued to be referred to as 'Sraidbhaile' in Irish into the 20th Century.

Norman arrival

By the time of theNorman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 9th and 10th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norma ...

invasion of Ireland in 1169, ''Magh Muirthemne'' had been absorbed into the kingdom of ''Airgíalla

Airgíalla (; Modern Irish: Oirialla, English: Oriel, Latin: ''Ergallia'') was a medieval Irish over-kingdom and the collective name for the confederation of tribes that formed it. The confederation consisted of nine minor kingdoms, all indepen ...

'' (Oriel) under the Ó Cearbhaills. In about 1185

Year 1185 ( MCLXXXV) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* August – King William II of Sicily ("the Good") lands in Epirus with a Siculo-Norman expeditionary force of 2 ...

, Bertram de Verdun

Bertram de Verdun was the name of several members of the Norman family of de Verdun, native to the Avranchin.

According to the historian Mark Hagger, the de Verdun family lived originally in Normandy where they held land, and after the Norman ...

, a counsel

A counsel or a counsellor at law is a person who gives advice and deals with various issues, particularly in legal matters. It is a title often used interchangeably with the title of ''lawyer''.

The word ''counsel'' can also mean advice given ...

of Henry II of England

Henry II () was King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with the ...

, erected a manor house at Castletown Mount on the ancient site of ''Dún Dealgan''. De Verdon founded his settlement seemingly without resistance from ''Airgíalla'' (the Ó Cearbhaills are recorded as having submitted to Henry by this time), and in 1187 he founded an Augustinian friary under the patronage of St Leonard

Leonard of Noblac (also Leonard of Limoges or Leonard of Noblet; also known as Lienard, Linhart, Lenart, Leonhard, Léonard, Leonardo, Annard; died 559) is a Frankish saint closely associated with the town and abbey of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat, ...

. He was awarded the lands around what is now Dundalk by Prince John on the death of Murchadh Ó Cearbhaill in 1189.

On de Verdun's death in Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

in 1192 at the end of the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt led by King Philip II of France, King Richard I of England and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187. F ...

, his lands at Dundalk passed to his son Thomas and then to his second son Nicholas after Thomas died. In 1236, Nicholas's daughter Roesia commissioned Castle Roche, 8 km north-west of the present-day town centre, on a large rocky outcrop with a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. It was completed by her son, John, in the 1260s.

Castle Roche was destroyed in 1315 by the armies of

Castle Roche was destroyed in 1315 by the armies of Edward Bruce

Edward Bruce, Earl of Carrick (Norman French: ; ; Modern Scottish Gaelic: or ; 1280 – 14 October 1318), was a younger brother of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots. He supported his brother in the 1306–1314 struggle for the Scottish cro ...

, brother of the Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

king Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (), was King of Scots from 1306 until his death in 1329. Robert led Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against Kingdom of Eng ...

, as they made their way south through Ulster during the Bruce campaign in Ireland

The Bruce campaign was a three-year military campaign in Ireland by Edward Bruce, brother of the Scottish king Robert the Bruce. It lasted from his landing at Larne in 1315 to his defeat and death in 1318 at the Battle of Faughart in County ...

. They then attacked the town and massacred its population. After taking possession of the town, Bruce proclaimed himself King of Ireland

Monarchical systems of government have existed in Ireland from ancient times. This continued in all of Ireland until 1949, when the Republic of Ireland Act removed most of Ireland's residual ties to the British monarch. Northern Ireland, as p ...

. Following three more years of battles across the north-eastern part of the island, Bruce was killed and his army defeated at the Battle of Faughart

The Battle of Faughart (or Battle of Dundalk) was fought on 14 October 1318 between an Anglo-Irish force led by John de Bermingham (later created 1st Earl of Louth) and Edmund Butler, Earl of Carrick, and a Scottish and Irish army command ...

by a force led by John de Birmingham, who was created the 1st Earl of Louth as a reward.

Later generations of de Verduns continued to own lands at Dundalk into the 14th century. Following the death of Theobald de Verdun, 2nd Baron Verdun

Theobald de Verdun (1278–1316) was the second and eldest surviving son of Theobald de Verdun, 1st Baron Verdun, of Alton, Staffordshire, and his wife Margery de Bohun. The elder Theobald was the son of John de Verdon, otherwise Le Botiller, o ...

in 1316 without a male heir, the family's landholdings were split. One of Theobold de Verdun's daughters, Joan, married the second Baron Furnivall

Baron Furnivall is an ancient title in the Peerage of England. It was originally created (by writ) when Thomas de Furnivall was summoned to the Model Parliament on 24 June 1295 as Lord Furnivall. The barony eventually passed to Thomas Nevill, who ...

, Thomas de Furnivall, and his family subsequently acquired much of the de Verdun land at Dundalk. The de Furnivall family's coat of arms formed the basis of the seal of the 'New Town of Dundalk'—a 14th-century seal discovered in the early 20th century, which became the town's coat of arms in 1968. The 'new town' that was established in the 13th century is the present-day town centre; the 'old town of the Castle of Dundalk' being the original de Verdun settlement at Castletown Mount 2 km to the west. The de Furnivalls then sold their holdings to the Bellew family, another Norman family long established in County Meath. The town was granted its first formal charter as a 'New Town' in the late 14th century under the reign of Richard II of England

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Jo ...

.

In effect a frontier town as the northernmost outpost of The Pale, Dundalk continued to grow in the 14th and 15th centuries. The town was regularly attacked and was heavily fortified, with at least 14 separate assaults, sieges or demands for tribute by a resurgent native Irish population recorded between 1300 and 1600 (with more than that number being likely).

English rule

In 1540, the Priory of St Leonard founded by Bertram de Verdun was surrendered to the Crown because of

In 1540, the Priory of St Leonard founded by Bertram de Verdun was surrendered to the Crown because of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

's Dissolution of the Monasteries. During the subsequent Tudor conquest of Ireland

Ireland was conquered by the Tudor monarchs of England in the 16th century. The Anglo-Normans had Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, conquered swathes of Ireland in the late 12th century, bringing it under Lordship of Ireland, English rule. In t ...

, Dundalk remained the northern outpost of English rule. In 1600, the town was used as a base of operations for the English, led by Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy

Charles Brooke Blount, 1st Earl of Devonshire, KG (pronounced ''Blunt''; 15633 April 1606), was an English nobleman and soldier who served as Lord Deputy of Ireland under Elizabeth I, and later as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland under James I. He wa ...

, for their push into Ulster through the 'Gap of the North' (the Moyry Pass

The Moyry Pass is a geographical feature on the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. It is a mountain pass running along Slieve Gullion between Newry and Dundalk. It is also known as the Gap of the North.Spring p.105

The pa ...

) during the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between Kingdom of France, France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial poss ...

.

Following the Flight of the Earls

On 14 September ld Style and New Style dates, O.S. 4 September1607, Irish earls Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O'Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, permanently departed Rathmullan in Ireland for mainland Europe, accompanied by their fa ...

, the subsequent Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster (; Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster Scots: ) was the organised Settler colonialism, colonisation (''Plantation (settlement or colony), plantation'') of Ulstera Provinces of Ireland, province of Irelandby people from Great ...

(and the associated suppression of Catholicism) resulted in the Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 was an uprising in Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, initiated on 23 October 1641 by Catholic gentry and military officers. Their demands included an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and ...

. After only token resistance, Dundalk was occupied by an Ulster Irish Catholic army on 31 October. They subsequently tried and failed to take Drogheda and retreated to Dundalk. The Royal Irish Army

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family or royalty

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, ...

, who were led by the Duke of Ormond

The peerage title Earl of Ormond and the related titles Duke of Ormonde and Marquess of Ormonde have a long and complex history. An earldom of Ormond has been created three times in the Peerage of Ireland.

History of Ormonde titles

The earldom ...

(and known as Ormondists), in turn, laid siege to Dundalk and overran and plundered the town in March 1642, killing many inhabitants.

The Ormondists held the town during the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

until it was occupied by the Northern Parliamentary Army of George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (6 December 1608 3 January 1670) was an English military officer and politician who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support ...

. The Parliamentarians held it for two years before surrendering it back to the Ormondists. It was then retaken by the forces of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, who had landed in Ireland in August 1649 and sacked Drogheda

Drogheda ( , ; , meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth ...

. After the massacre in Drogheda, Cromwell wrote to the Ormondist commander in Dundalk warning him that his garrison would suffer the same fate if it did not surrender. The Duke of Ormond ordered the commander to have his men burn the town before his retreat, but they did not do so such was their haste to leave. For the remainder of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the Commonwealth of England, initially led by Oliver Cromwell. It forms part of the 1641 to 1652 Irish Confederate Wars, and wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three ...

, the town was again used as a base for operations against the Irish in Ulster.

After the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state. This may refer to:

*Conservation and restoration of cultural property

**Audio restoration

**Conservation and restoration of immovable cultural property

**Film restoration

** Image ...

of the monarchy, the Corporation of Dundalk was granted a new charter by Charles II on 4 March 1673. The forfeiture of property and settlements carried out during the Restoration saw much of the land of Dundalk granted to Marcus Trevor, 1st Viscount Dungannon

Marcus Trevor, 1st Viscount Dungannon (1618 – 3 January 1670), also known as Colonel Mark Trevor, was an Anglo-Irish soldier and peer. During the English Civil War and the Interregnum he switched sides several times between the Royalist and Parl ...

, who had fought for both sides in the civil war. Even though the Bellews were seen as Papists

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox ...

, Sir John Bellew appears to have held onto much of his family's legacy landholdings.

When the Williamite War in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland took place from March 1689 to October 1691. Fought between Jacobitism, Jacobite supporters of James II of England, James II and those of his successor, William III of England, William III, it resulted in a Williamit ...

began in 1689, the Williamite commander Schomberg landed in Belfast and marched unopposed to Dundalk but, as the bulk of his forces were raw and undisciplined as well as inferior in numbers to the Jacobite Irish Army

The Irish Army () is the land component of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Defence Forces of Republic of Ireland, Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. ...

, he decided against risking a battle. He entrenched himself at Dundalk and declined to be drawn beyond the circle of his defences. With poor logistics and struck by disease, over 5,000 of his troops died.

After the end of the Williamite War, the third Viscount Dungannon, Mark Trevor, sold the Dundalk estate to James Hamilton of Tollymore, County Down. Hamilton's son, also James, was created Viscount Limerick in 1719 and then the first Earl of Clanbrassil in 1756. The modern town of Dundalk owes its form to Hamilton. The military activity of the 17th century had left the town's walls in ruins. With the collapse of the Gaelic aristocracy and the total takeover of the country by the English, Dundalk was no longer a frontier town and no longer had a need for its 15th-century fortifications. Hamilton commissioned the construction of streets leading to the town centre; his ideas stemming from his visits to Continental Europe. In addition to the demolition of the old walls and castles, he had new roads laid out eastwards of the principal streets.

When the first Earl died in 1758, the estates passed to his son, the second Earl of Clanbrassil, who died without an heir in 1798. The Earl of Roden

Earl of Roden is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1771 for Robert Jocelyn, 2nd Viscount Jocelyn. This branch of the Jocelyn family descends from the 1st Viscount, prominent Irish lawyer and politician Robert Jocelyn, the s ...

inherited the Dundalk estate because the second Earl's sister, Lady Anne Hamilton, had married Robert Jocelyn, the first Earl of Roden. Portions of the Roden Dundalk estate were sold under the auspices of the various land acts of the 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in the Irish Free State government lands purchase acts of the 1920s. The remaining freeholds and ground rents were sold in 2006, severing the links between the Earls of Roden and the town of Dundalk.

During the 18th century, Ireland was controlled by the minority Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy (also known as the Ascendancy) was the sociopolitical and economical domination of Ireland between the 17th and early 20th centuries by a small Anglicanism, Anglican ruling class, whose members consisted of landowners, ...

via the Penal Laws

Penal law refers to criminal law.

It may also refer to:

* Penal law (British), laws to uphold the establishment of the Church of England against Catholicism

* Penal laws (Ireland)

In Ireland, the penal laws () were a series of Disabilities (C ...

, which discriminated against both the majority Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

population and Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

. Mirroring other boroughs around the country, Dundalk Corporation was a 'closed shop', consisting of an electorate of 'freemen' (mostly absentee landlords of the Ascendancy). The Earl of Clanbrassil controlled the procedures for both the nomination of new freemen and the nomination of parliamentary candidates, therefore disenfranchising the local populace. In the late 18th century, the United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure Representative democracy, representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British ...

movement, inspired by the American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

and French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

revolutions, led to the Rebellion of 1798. In north Louth, the authorities had successfully suppressed the activities of the United Irishmen prior to the rebellion with the help of informants, and several local leaders had been rounded up and imprisoned in Dundalk Gaol. An attack on the military barracks and gaol to free prisoners was planned for 21 June 1798. The attack failed because of a thunderstorm, which dispersed the gathered United Irish volunteers, and two of the jailed leaders—Anthony Marmion and John Hoey—were subsequently tried for treason and hanged.

After the Acts of Union

Following the Act of Union, which came into force on 1 January 1801, The 19th century saw industrial expansion in the town (seeEconomy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

) and the construction of several buildings that are landmarks in the town. The first railway links arrived when the Dundalk and Enniskillen Railway

Irish North Western Railway (INW) was an Irish gauge () railway company in Ireland.

Development

The company was founded as the Dundalk and Enniskillen Railway (D&ER) and opened the first section of its line, from to , in 1849. In Dundalk t ...

opened a line from Quay Street to Castleblayney in 1849, and by 1860 the company operated a route northwest to Derry. Also in 1849, the Dublin and Belfast Junction Railway

Dublin and the Belfast Junction Railway (D&BJct) was an Irish gauge () railway in Ireland. The company was incorporated in 1845 and opened its line in stages between 1849 and 1853, with the final bridge over the River Boyne opening in 1855. ...

opened Dundalk railway station

Dundalk Clarke railway station ( ''Dún Dealgan'') serves Dundalk in County Louth, Republic of Ireland, Ireland.

It consists of an island platform, with a Bay platform, bay facing south. It is served by the Dublin-Belfast ''Enterprise (train s ...

. Following a series of mergers, both lines were incorporated into the Great Northern Railway (Ireland)

The Great Northern Railway (Ireland) (GNR(I), GNRI or simply GNR) was an Irish gauge () railway company in Ireland. It was formed in 1876 by a merger of the Irish North Western Railway (INW), Northern Railway of Ireland, and Ulster Railway. Th ...

in 1876.

The established and merchant classes prospered alongside a general population that suffered from poverty. A typhus epidemic struck in the 1810s, potato-crop failures in the 1820s caused famine, and a cholera epidemic struck in the 1830s. During the Great Famine of the 1840s, the town did not suffer to the same extent as the west and south of Ireland. Cereal-based agriculture, new industries, construction projects, and the arrival of the railway all contributed to sparing the town of its worst effects. Nevertheless, so many people died in the Dundalk Union Workhouse

In Britain and Ireland, a workhouse (, lit. "poor-house") was a total institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. In Scotland, they were usually known as Scottish poorhouse, poorh ...

that the graveyard was quickly filled. A second graveyard was opened on the Ardee Road—the Dundalk Famine Graveyard—which is known to contain approximately 4,000 bodies. It was closed in 1905 and was left derelict until the 21st century when local volunteers worked to restore it.

The latter part of the 19th century was dominated by the

The latter part of the 19th century was dominated by the Irish Home Rule movement

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to ...

and Dundalk became a focal point of the politics of the time. The Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún''), also known as the Land League, was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which organised tenant farmers in their resistance to exactions of landowners. Its prima ...

held a demonstration in Dundalk on New Year's Day, 1881, stated by the local press to be the largest gathering ever seen in the town.

As the Home Rule movement developed, the sitting Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

MP, Philip Callan

Philip Callan (1837 - 13 June 1902) was an Irish Member of Parliament.

Early life

Callan was born in Cookstown House Ardee in 1837 and was the son of Owen Callan. He studied law at Trinity College Dublin, and also at the King's Inns as can be ...

, fell out with party leader Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom from 1875 to 1891, Leader of the Home Rule Leag ...

, who travelled to Dundalk to oversee efforts to have Callan unseated. Parnell's candidate, Joseph Nolan Joseph Nolan may refer to:

* Joseph Nolan (politician) (c. 1846–1928), Irish nationalist politician

* Joseph Nolan (organist) (born 1974), English-born Australian organist and conductor.

* Joseph A. Nolan (1857–1921), United States Army sold ...

, defeated Callan in the election of 1885 after a campaign of voter suppression and intimidation on both sides. Following the split in the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

, the leading anti-Parnellite

The Irish National Federation (INF) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded in 1891 by former members of the Irish National League (INL), after a split in the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) on the leadership of Charles S ...

, Tim Healy, won the North Louth seat in 1892

In Samoa, this was the only leap year spanned to 367 days as July 4 repeated. This means that the International Date Line was drawn from the east of the country to go west.

Events

January

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins processing imm ...

, defeating Nolan (who had stayed loyal to Parnell). The campaign, predicted by Healy to be "the nastiest fight in Ireland", saw running battles and mass brawls in the streets between Parnellites, 'Healyites', and 'Callanites'—supporters of Philip Callan, who was trying to regain his seat.

The local Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

cumann

A ( Irish for association; plural ) is the lowest local unit or branch of a number of Irish political parties. The term ''cumann'' may also be used to describe a non-political association. Cumainn are usually made up of 5+ (the recommendation ...

was founded in 1907 by Patrick Hughes. It struggled to grow beyond a handful of members because of the dominance of the existing political factions. In 1910, on the accession of George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

to the English throne, the local High Sheriff, accompanied by police and soldiers, led a proclamation to the new king at the Market Square. The ceremony was interrupted by the local Sinn Féin members, who raised a tricolour beside the Maid of Erin monument and chanted "God Save Ireland" during a rendition of "God Save the King"—giving the party visibility in the town for the first time.

Approximately 2,500 men from Louth volunteered for Allied regiments in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and it is estimated that 307 men from the Dundalk district died during the war. In the months before the outbreak of the war, the G.N.R. converted nine of its carriages into a mobile 'ambulance train', which could hold 100 wounded soldiers. ''Ambulance Train 13'' was kept in service for the duration of the war before being decommissioned in 1919. The war came to Dundalk weeks before the Armistice, when the ''S.S. Dundalk'' was sunk by a German U-boat on 14 October 1918 on a voyage from Liverpool to Dundalk. 20 crew-members were killed, while 12 were rescued.

Meanwhile, the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

had changed the political landscape. 80 members of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

had left Dundalk to take part in the Rising. After the countermanding order of Eoin MacNeill

Eoin MacNeill (; born John McNeill; 15 May 1867 – 15 October 1945) was an Irish scholar, Irish language enthusiast, Gaelic revivalist, nationalist, and politician who served as Minister for Education from 1922 to 1925, Ceann Comhairle of D ...

, members of the unit ended up in Castlebellingham

Castlebellingham () is a village and townland in County Louth, Ireland. The village has become quieter since the construction of the new M1 motorway, which bypasses it. The population of Castlebellingham-Kilsaran (named for the two townlands whi ...

, trying to evade the Dundalk RIC. There, they held several RIC men and a British Army officer at gunpoint until one of the Volunteers, believing the army officer was reaching for a hidden weapon, fired at the captives, killing RIC constable Charles McGee. After the Rising ended, the Volunteers went on the run and most were captured. Four were sentenced to death for the murder of Constable McGee but were released in the general amnesty of 1917.

Independence

In the1918 Irish general election

The Irish component of the 1918 United Kingdom general election took place on 14 December 1918. It was the final United Kingdom general election to be held throughout Ireland, as the next election would happen following Irish independence. It is ...

, Louth elected its first Sinn Féin MP when John J. O'Kelly defeated the sitting MP, Richard Hazleton

Richard Hazleton (5 December 1879 – 26 January 1943) was an Irish nationalist politician of the Irish Parliamentary Party. He was Member of Parliament (MP) for North Galway from 1906 to 1918, taking his seat in the House of Commons of the U ...

of the Irish Parliamentary Party, in the closest contest of the election—O'Kelly winning by 255 votes. In the run-up to the election, the local newspapers had supported the Irish Party over Sinn Féin and complained afterwards that the area of Drogheda in County Meath that was included in the Louth constituency had tipped the contest in Sinn Féin's favour. Again, the campaign saw reports of widespread violence and intimidation tactics.

There was no strategic military action in north Louth during the

There was no strategic military action in north Louth during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

. Activity consisted of acts of sabotage and attacks on the RIC to seize arms. Arson attacks were a feature of the period in particular. Crown forces committed reprisal attacks in response, hardening support for Sinn Féin. In the aftermath of a shooting of an RIC auxiliary on 17 June 1921, brothers John and Patrick Watters were taken from their home at the Windmill Bar and shot dead. The British authorities subsequently suppressed the ''Dundalk Examiner'' newspaper for reporting on the incident, and smashed its printing presses. Volunteers

Volunteering is an elective and freely chosen act of an individual or group giving their time and labor, often for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergenc ...

from the area led by Frank Aiken

Francis Thomas Aiken (13 February 1898 – 18 May 1983) was an Irish revolutionary and politician. He was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army, chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army (1922–1969), Anti-Treaty IRA at the end of the I ...

were more active in Ulster, and were responsible for the derailing of a military train at Adavoyle railway station, 13 km north of Dundalk, which killed three soldiers, the train's guard, and dozens of horses.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

turned Dundalk, once again, into a frontier town. In the new Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, the split over the treaty led to the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

. Before the outbreak of hostilities, Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

toured Ireland making a series of anti-treaty speeches. He visited Dundalk on 2 April 1922 and before a large crowd in the Market Square, he said that those who had negotiated the treaty "had run across to Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

to be spanked like little boys".

Frank Aiken attempted to keep his division neutral during the split over the treaty but on 16 July 1922, Aiken and all of the anti-treaty elements among his men were arrested and imprisoned at Dundalk military barracks and Dundalk Gaol in a surprise move by the pro-treaty Fifth Northern Division, now part of the National Army. On 27 July, anti-treaty 'Irregulars' blew a hole in the outer wall of the gaol, freeing Aiken and his men. On 14 August, Aiken led an attack on the barracks that resulted in its capture with five National Army and two Irregular soldiers killed. Aiken's men killed another dozen National Army soldiers in guerrilla attacks before the town was retaken without resistance on 26 August. Before withdrawing, Aiken called for a truce at a meeting in the centre of Dundalk.

From that point, north Louth ceased to be an area of strategic importance in the war. Guerrilla attacks continued—mostly acts of sabotage, particularly against the railway. In January 1923, six anti-treaty prisoners were executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

by firing squad in Dundalk for bearing arms against the state.

Border town

Thepartition of Ireland

The Partition of Ireland () was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland (the area today known as the R ...

turned Dundalk into a border town and the Dublin–Belfast main line into an international railway. On 1 April 1923, the Free State government began installing border posts for the purpose of collecting customs duties. Almost immediately, the town started to suffer economic problems. The introduction of the border and tariffs exacerbated the effects of a global post-war slump.

With a population of 14,000 at the time, unemployment was reported to be nearly 2,000 and it was reported that: "Up to a few years ago, Dundalk was one of the most prosperous and go-ahead towns in Ireland... utit is a matter of common local knowledge that distress to an acute degree is prevalent". The Anglo-Irish trade war

The Anglo-Irish Trade War (also called the Economic War) was a retaliatory trade war between the Irish Free State and the United Kingdom from 1932 to 1938. The Irish government refused to continue reimbursing Britain with land annuities from f ...

, in the midst of a global depression, made things more difficult still. The industrial situation stabilised, however, as the protectionist policies adopted allowed local industries to increase employment and prosper.

During the Emergency (as World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

was called in Ireland), there were three aeroplane crashes in what is now the municipal district. A British Hudson bomber crashed in 1941, killing three crew, and a P-51 Mustang fighter of the US Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

crashed in September 1944, killing its pilot. The worst of the wartime air crashes occurred on 16 March 1942. 15 allied airmen died when their Consolidated B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models desi ...

bomber crashed into Slieve na Glogh, which rises above the townland of Jenkinstown. On 24 July 1941, the Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

dropped bombs near the town. There were no casualties and only minor damage was caused.

The town continued to grow in size after the war—in terms of area, population and employment—despite economic shocks such as the dissolution of the G.N.R. in 1958. The accession of Ireland to the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

in 1973, however, saw factory closures and job losses in businesses that struggled due to competition, collapsing consumer confidence, and unfavourable exchange rates with cross-border competitors. The downturn resulted in an unemployment rate of 26% by 1986.

In addition, the outbreak of the Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

in Northern Ireland in 1968 and the town's position close to the border saw the town's population swell, as nationalists/Catholics fleeing the violence in Northern Ireland settled in the area. As a result of the ongoing sectarianism

Sectarianism is a debated concept. Some scholars and journalists define it as pre-existing fixed communal categories in society, and use it to explain political, cultural, or Religious violence, religious conflicts between groups. Others conceiv ...

in the north, there was sympathy for the cause of the Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA), officially known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA; ) and informally known as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary force that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland ...

and Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

, and the town was home to several IRA members. It was in this period that Dundalk earned the nickname 'El Paso

El Paso (; ; or ) is a city in and the county seat of El Paso County, Texas, United States. The 2020 United States census, 2020 population of the city from the United States Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the List of ...

', after the town in Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

on the border with Mexico. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

asked Taoiseach

The Taoiseach (, ) is the head of government or prime minister of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the President of Ireland upon nomination by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

Garret FitzGerald

Garret Desmond FitzGerald (9 February 192619 May 2011) was an Irish Fine Gael politician, economist, and barrister who served twice as Taoiseach, serving from 1981 to 1982 and 1982 to 1987. He served as Leader of Fine Gael from 1977 to 1987 an ...

after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement

The Anglo-Irish Agreement was a 1985 treaty between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland which aimed to help bring an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The treaty gave the Irish government an advisory role in Northern Irelan ...

what his reaction would be if the British bombed Dundalk to stop the IRA from launching attacks in Northern Ireland.

On 19 December 1975, a car bombing in the centre of the town carried out by the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group based in Northern Ireland. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former Royal Ulster Rifles soldier from North ...

killed two people and injured 15. There were several incidents of British military incursions into North Louth. The town was also the scene of several killings connected to the INLA and its internal feuds and criminal activity. On 1 September 1973, the 27 Infantry Battalion of the Irish Army

The Irish Army () is the land component of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Defence Forces of Republic of Ireland, Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. ...

was established with its headquarters in Dundalk barracks, as a result of the ongoing violence in the border region of North Louth / South Armagh. The barracks was renamed Aiken Barracks in 1986 in honour of Frank Aiken.

Dundalk celebrated its 'official' 1200th year in 1989, meaning the Irish government recognised 789 as the year in which the first settlement was founded, with then President of Ireland, Dr. Patrick Hillery

Patrick John Hillery (; 2 May 1923 – 12 April 2008) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as the sixth president of Ireland from December 1976 to December 1990. He also served as vice-president of the European Commission and Europea ...

, attending a celebration at the Market Square.

After the start of the Northern Ireland peace process

The Northern Ireland peace process includes the events leading up to the 1994 Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire, the end of most of the violence of the Troubles, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and subsequent political develop ...

, and the subsequent Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) or Belfast Agreement ( or ; or ) is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April (Good Friday) 1998 that ended most of the violence of the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland since the la ...

, then U.S. president, Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

chose Dundalk to make an open-air address in December 2000 in support of the peace process. In his speech in the Market Square, witnessed by an estimated 60,000 people, Clinton spoke of "a new day in Dundalk and a new day in Ireland".

21st century

The town was slow to benefit from a 'peace dividend', and in the first decade of the new millennium the two Diageo-owned breweries and theCarroll's

P. J. Carroll & Company Limited, often called Carroll's, is an Irish manufacturing company of tobacco. Having been established in 1824, P.J. Carroll is the oldest tobacco manufacturer in the country, and currently a subsidiary of British Amer ...

tobacco factory were among several factories to close—finally severing the links to the town's industrial past. By 2012, the town was being painted as "one of Ireland's most deprived areas" after the global downturn following the 2008 financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), was a major worldwide financial crisis centered in the United States. The causes of the 2008 crisis included excessive speculation on housing values by both homeowners ...

.

Indigenous industry started to recover, with the Great Northern Brewery being reopened as 'the Great Northern Distillery' in 2015 by John Teeling

John James Teeling (born January 1946) is an Irish academic and businessperson, notable for the wide range of businesses he has developed or overhauled over several decades. In particular, he broke the Irish Distillers monopoly which existed i ...

, who had established and later sold the Cooley Distillery

Cooley Distillery is an Irish whiskey distillery on the Cooley Peninsula in County Louth, Republic of Ireland, Ireland established in 1987 and owned by Suntory Global Spirits, a subsidiary of Suntory Holdings of Osaka, Japan.

The distillery ...

; and locally-driven initiatives led to a flurry of foreign direct investment

A foreign direct investment (FDI) is an ownership stake in a company, made by a foreign investor, company, or government from another country. More specifically, it describes a controlling ownership an asset in one country by an entity based i ...

announcements in the latter half of the 2010s, particularly in the technology and pharmaceutical sectors.

The town's association football

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 Football player, players who almost exclusively use their feet to propel a Ball (association football), ball around a rectangular f ...

club, Dundalk F.C.

Dundalk Football Club ( ) is a professional football club that competes in the League of Ireland First Division. It was founded in 1903 as Dundalk G.N.R., the works-team of the Great Northern Railway. It is based in Dundalk, County Louth and ...

, formed in 1903 by the workers of the Great Northern Railway, received European-wide recognition when it became the first Irish side to win points in the group stage of European competition in the 2016–17 UEFA Europa League

The 2016–17 UEFA Europa League was the 46th season of Europe's secondary club football tournament organised by UEFA, and the eighth season since it was renamed from the UEFA Cup to the UEFA Europa League.

The final was played between Ajax and ...

.

In April 2023, Joe Biden

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. (born November 20, 1942) is an American politician who was the 46th president of the United States from 2021 to 2025. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as the 47th vice p ...

, who has ancestry in north Louth, became the second sitting US president to visit the town.

Geography

Dundalk lies on the54th parallel north

Following are circles of latitude between the 50th parallel north and the 55th parallel north:

51st parallel north

The 51st parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 51 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, A ...

circle of latitude

A circle of latitude or line of latitude on Earth is an abstract east–west small circle connecting all locations around Earth (ignoring elevation) at a given latitude coordinate line.

Circles of latitude are often called parallels because ...

. It is situated where the Castletown River

The Castletown River () is a river which flows through the town of Dundalk, County Louth, Ireland. It rises near Newtownhamilton, County Armagh, Northern Ireland, and is known as the Creggan River in its upper reaches. Its two main tributaries ...

flows into Dundalk Bay

Dundalk Bay () is a large (33 km2), exposed estuary on the east coast of Ireland.