Duško Popov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

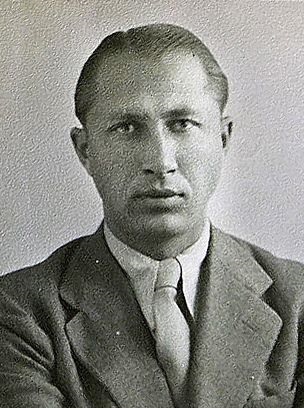

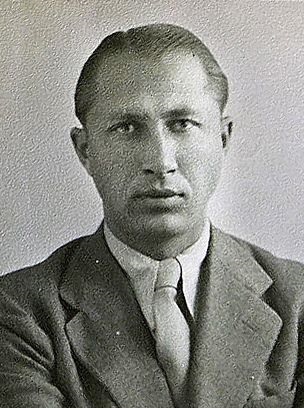

Dušan "Duško" Popov ( sr-Cyrl, Душко Попов; 10 July 1912 – 10 August 1981) was a

Upon his return to Dubrovnik in the fall of 1937, Popov began practicing law. In February 1940, he received a message from Jebsen, asking to meet him at the Hotel Serbian King in Belgrade. Popov was shocked to find Jebsen a nervous wreck, chain smoking and drinking exorbitantly. He told Popov that he had joined his family's shipping business after graduating from Freiburg and explained that he needed a Yugoslav shipping license to evade the Allied naval blockade at

Upon his return to Dubrovnik in the fall of 1937, Popov began practicing law. In February 1940, he received a message from Jebsen, asking to meet him at the Hotel Serbian King in Belgrade. Popov was shocked to find Jebsen a nervous wreck, chain smoking and drinking exorbitantly. He told Popov that he had joined his family's shipping business after graduating from Freiburg and explained that he needed a Yugoslav shipping license to evade the Allied naval blockade at

FBI: A History''"> FBI: A History''

p.110. Yale University Press. . or they, for reasons of their own, took no action. Hoover distrusted Popov because he was a double agent although MI6 had told the FBI in

The spy who

',

The spy who inspired 007

' (2024).

Official website

VOA Profile

The National Archives

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Popov, Dusan 1912 births 1981 deaths 20th-century British memoirists Abwehr personnel of World War II English people of Serbian descent Serbian Austro-Hungarians Double agents Double-Cross System People educated at Ewell Castle School People from Titel Serbian people of World War II Serbian socialites Serbian spies University of Freiburg alumni Spies World War II spies for Germany World War II spies for the United Kingdom

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

n intelligence agent, lawyer and businessman who served as a double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

for MI6 during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Feigning to be an asset of the German Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

, he passed off disinformation

Disinformation is misleading content deliberately spread to deceive people, or to secure economic or political gain and which may cause public harm. Disinformation is an orchestrated adversarial activity in which actors employ strategic dece ...

to Germany as part of the British Double-Cross System

The Double-Cross System or XX System was a World War II counter-espionage and deception operation of the British Security Service ( MI5). Nazi agents in Britain – real and false – were captured, turned themselves in or simply announced themse ...

while occasionally using cover as a diplomat for the Yugoslav government-in-exile in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

.

Popov was born into a wealthy family and was practicing law at the start of the war. He held a great aversion to Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

, and in 1940, infiltrated the Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

, Germany's military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

service, which considered him a valuable asset due to his business connections in France and the United Kingdom. Popov provided the Germans with misleading and inaccurate information for much of the war.

Deceptions in which he participated included Operation Fortitude

Operation Fortitude was a military deception operation by the Allied nations as part of Operation Bodyguard, an overall deception strategy during the buildup to the 1944 Normandy landings. Fortitude was divided into two subplans, North and So ...

, which sought to convince German military planners that the Allied invasion of Europe would take place in Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

, not Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

, thereby diverting hundreds of thousands of German troops and increasing the likelihood that Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The ope ...

would succeed.

Popov was known for his lifestyle and courted women during his missions, including the French actress Simone Simon. Apart from MI6 and the Abwehr, he also reported to the Yugoslav intelligence service, which assigned him the codename Duško. His German handlers referred to him by the codename Ivan. He was codenamed Tricycle by the British MI5 because he was the head of a group of three double agents.

In 1974, he published an autobiography titled ''Spy/Counterspy'', in which he recounted his wartime exploits. Popov is considered one of Ian Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer, best known for his postwar ''James Bond'' series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., and his ...

's primary inspirations for the character of James Bond

The ''James Bond'' franchise focuses on James Bond (literary character), the titular character, a fictional Secret Intelligence Service, British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels ...

. He has been the subject of a number of non-fiction books and documentaries.

Early life

Dušan "Duško" Popov was born to a Serb family inTitel

Titel ( sr-Cyrl, Тител, ) is a town and municipality located in the South Bačka District of the province of Vojvodina, Serbia. The town of Titel has a population of 4,522, while the population of the municipality of Titel is 13,984 (2022 ...

, Austria-Hungary on 10 July 1912. His parents were Milorad and Zora Popov. He had an older brother named Ivan ("Ivo") (who also became an agent, codenamed Dreadnought) and a younger brother named Vladan. The family was exceedingly wealthy and owed its fortune to Popov's paternal grandfather, Omer, a wealthy banker and industrialist who founded a number of factories, mines, and retail businesses. They hailed from the village of Karlovo (now Novo Miloševo). Records from as early as 1773 describe them as the most affluent family there. Popov's father expanded the family's business interests to include real estate dealings. When Popov was an infant, the family left Titel and permanently relocated to their summer residence in Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik, historically known as Ragusa, is a city in southern Dalmatia, Croatia, by the Adriatic Sea. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean, a Port, seaport and the centre of the Dubrovni ...

, which was their home for much of the year. They also had a manor in Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

, where they spent the winter months.

Popov's childhood coincided with a series of monumental political changes in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. In November 1918, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

disintegrated into a number of smaller states, and its Balkan possessions were incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () has been its colloq ...

(renamed Yugoslavia in 1929). The newly established, Serb-led state was plagued by political infighting among its various constitutive ethnic groups, particularly Serbs and Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

, but also Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars, are an Ethnicity, ethnic group native to Hungary (), who share a common Culture of Hungary, culture, Hungarian language, language and History of Hungary, history. They also have a notable presence in former pa ...

and Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

. The young Popov and his family enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle and were far removed from the political turmoil in the country. They boasted a sizeable collection of villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

s and yachts, and were attended by servants, even on their travels. Duško and his brothers spent most of their formative years along the Adriatic coast, and were avid athletes and outdoorsmen.

Popov's father indulged his sons, building a spacious villa by the sea for their exclusive use where they could entertain their friends and host expensive parties. He was also insistent that they receive a quality education. Apart from his native Serbian, Popov was fluent in Italian, German and French by his teenage years. Between the ages of 12 and 16, he attended a '' lycée'' in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

.

In 1929, Popov's father enrolled him into Ewell Castle, a prestigious preparatory school in Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

. Popov's stint at the school proved to be short lived. After only four months, he was expelled following an altercation with a teacher. He had previously endured a caning at the teacher's hands after being caught smoking a cigarette. Another caning was adjudicated after Popov missed a detention, and so as to evade further corporal punishment

A corporal punishment or a physical punishment is a punishment which is intended to cause physical pain to a person. When it is inflicted on Minor (law), minors, especially in home and school settings, its methods may include spanking or Padd ...

, Popov grabbed the teacher's cane and snapped it in two before his classmates. Popov's father subsequently enrolled him at '' Lycée Hoche'', a secondary institution in Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

, which he attended for the following two years.

Student activism

At the age of 18, Popov enrolled in theUniversity of Belgrade

The University of Belgrade () is a public university, public research university in Belgrade, Serbia. It is the oldest and largest modern university in Serbia.

Founded in 1808 as the Belgrade Higher School in revolutionary Serbia, by 1838 it me ...

, seeking an undergraduate degree

An undergraduate degree (also called first degree or simply degree) is a colloquial term for an academic degree earned by a person who has completed undergraduate courses. In the United States, it is usually offered at an institution of higher ed ...

in law. Over the next four years, he became a familiar face in Belgrade's cafes and nightclubs, and had the reputation of a ladies' man. "Women ... found him irresistible," '' Times'' columnist Ben Macintyre writes, "with his easy manner, loose, sensual mouth ... and green ... bedroom eyes." In 1934, Popov enrolled in the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially ), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The university was founded in 1 ...

, intent on securing a doctorate in law. Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

had only recently come under the rule of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

and the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

, but at the time, Popov paid little regard to politics. He had chosen Freiburg because it was relatively close to his native country and he was eager to improve his German-language skills. Germany was already the site of mass book burnings, the first concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

had been established and the systematic persecution of Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

had commenced.

Popov began his studies at the University of Freiburg in the autumn of 1935, and in subsequent months, began showing greater interest in politics and voiced his political opinions more vigorously. Around the same time, he befriended a fellow student, Johnny Jebsen, the son of a German shipping magnate. The two grew close, largely due to their raucous lifestyle and a shared interest in sports vehicles. In 1936–37, Popov began participating in debates at the ''Ausländer Club'', which were held every other Friday evening. He was disappointed that many foreign students appeared to be swayed by the pro-Nazi arguments espoused there. Popov discovered that the German debaters were all hand-picked party members who chose the subject of each debate beforehand and vigorously rehearsed Nazi talking points. He persuaded Jebsen, then the president of the club, to inform him of the debate topics in advance and passed this information along to the British and American debaters. Popov himself delivered two speeches at the club, arguing in favour of democracy. He also wrote several articles for the Belgrade daily ''Politika

( sr-Cyrl, Политика, lit=Politics) is a Serbian daily newspaper, published in Belgrade. Founded in 1904 by Vladislav F. Ribnikar, it is the oldest daily newspaper still in circulation in the Balkans.

Publishing and ownership

is publ ...

'', ridiculing the Nazis. "Duško despised Nazism," biographer Larry Loftis writes, "and since he wasn't German, he believed he owed no allegiance to Hitler or the state."

In the summer of 1937, Popov completed his doctoral thesis, and decided to celebrate by embarking on a trip to Paris. Before he could leave, he was arrested by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

, who accused him of being a communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

. His movements had been tracked by undercover agents beforehand and his acquaintances questioned. Popov was incarcerated at the Freiburg prison without formal proceedings. When Jebsen received news of his friend's arrest, he called Popov's father and informed him of what had occurred. Popov's father contacted Yugoslav Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Milan Stojadinović

Milan Stojadinović ( sr-Cyrl, Милан Стојадиновић; 4 August 1888 – 26 October 1961) was a Serbs, Serbian and Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav politician and economist who was the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia from 1935 to 1939. ...

, who raised the issue with Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

, and after eight days in captivity, Popov was released. He was ordered to leave Germany within 24 hours, and upon collecting his belongings, boarded a train for Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. He soon arrived in Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

and found Jebsen waiting for him on the station platform. Jebsen informed Popov of the role he played in securing his release. Popov expressed gratitude and told Jebsen that if he was ever in need of any assistance he needed only ask.

World War II

Initiation

Upon his return to Dubrovnik in the fall of 1937, Popov began practicing law. In February 1940, he received a message from Jebsen, asking to meet him at the Hotel Serbian King in Belgrade. Popov was shocked to find Jebsen a nervous wreck, chain smoking and drinking exorbitantly. He told Popov that he had joined his family's shipping business after graduating from Freiburg and explained that he needed a Yugoslav shipping license to evade the Allied naval blockade at

Upon his return to Dubrovnik in the fall of 1937, Popov began practicing law. In February 1940, he received a message from Jebsen, asking to meet him at the Hotel Serbian King in Belgrade. Popov was shocked to find Jebsen a nervous wreck, chain smoking and drinking exorbitantly. He told Popov that he had joined his family's shipping business after graduating from Freiburg and explained that he needed a Yugoslav shipping license to evade the Allied naval blockade at Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

. Popov agreed to help Jebsen, and the latter travelled back to Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

to collect the required documentation. Two weeks later, Jebsen returned to Belgrade, and informed Popov that he had joined the ''Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

'', German's military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

service, as a ''Forscher'' (researcher).

Jebsen's ability to travel across Europe on business trips would remain unimpeded so long as he submitted reports detailing the information he had received from his business contacts. He told Popov he joined the ''Abwehr'' to avoid being conscripted into the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

''. Jebsen said military service was not an option because he suffered from varicose veins. The news came as a surprise to Popov, as his friend had previously expressed anti-Nazi views.

Popov informed Clement Hope, a passport control officer at the British legation in Yugoslavia. Hope enrolled Popov as a double agent with the codename Scoot (he was later known to his handler as Tricycle), and advised him to cooperate with Jebsen. Nigel West, 'Popov, Dusan (1912–1981)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2008 Once accepted as a double agent, Popov moved to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. His international business activities in an import-export business provided cover for visits to neutral Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

; its capital, Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, was linked to the UK by a weekly civilian air service for most of the war. Popov used his cover position to report periodically to his Abwehr handlers in Portugal. Popov fed enough MI6-approved information to the Germans to keep them happy and unaware of his actions, and was well-paid for his services. The assignments given to him were of great value to the British in assessing enemy plans and thinking.

His most important deception was convincing the Germans that the D-Day landings would be in Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

, not Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

, and was able to report back to MI6 that they fell for this deception, which corroborated Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and Bletchley Park estate, estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allies of World War II, Allied World War II cryptography, code-breaking during the S ...

's decryption of Lorenz cipher

The Lorenz SZ40, SZ42a and SZ42b were German Rotor machine, rotor stream cipher machines used by the German Army (Wehrmacht), German Army during World War II. They were developed by C. Lorenz AG in Berlin. The model name ''SZ'' is derived from ' ...

machine messages. Popov was famous for his playboy lifestyle, while carrying out perilous wartime missions for the British.

Allegations regarding Pearl Harbor

In 1941, Popov repeatedly travelled to Portugal during his missions. He stayed inEstoril

Estoril () is a town in the civil parish of Cascais e Estoril of the Portuguese Municipality of Cascais, on the Portuguese Riviera. It is a popular tourist destination, with hotels, beaches, and the Casino Estoril. It has been home to numero ...

, at the Hotel Palácio, in January and March 1941, then again between 29 June and 10 August 1941. Exiles Memorial Center. During his stay, he met Ian Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer, best known for his postwar ''James Bond'' series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., and his ...

, at the time working for the British Royal Navy. They both shared a mission at Casino Estoril, and it is believed that Popov served as inspiration for the character of James Bond

The ''James Bond'' franchise focuses on James Bond (literary character), the titular character, a fictional Secret Intelligence Service, British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels ...

in Fleming’s novels.

After this last stay, he was dispatched to the United States by the Abwehr to establish a new German network. He was given ample funds and an intelligence questionnaire (a list of intelligence targets, later published as an appendix to J.C. Masterman's book '' The Double Cross System''). Of the three typewritten pages of the questionnaire, one entire page was devoted to highly detailed questions about US defences at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

on the Hawaiian island of Oahu

Oahu (, , sometimes written Oahu) is the third-largest and most populated island of the Hawaiian Islands and of the U.S. state of Hawaii. The state capital, Honolulu, is on Oahu's southeast coast. The island of Oahu and the uninhabited Northwe ...

. He made contact with the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

and explained what he had been asked to do.

During a televised interview, Duško Popov related having informed the FBI on 12 August 1941 of the impending attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

. Either the FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover did not report this fact to his superiorsJeffreys-Jones, Rhodri (2007)FBI: A History''"> FBI: A History''

p.110. Yale University Press. . or they, for reasons of their own, took no action. Hoover distrusted Popov because he was a double agent although MI6 had told the FBI in

New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

that he would be arriving. Popov himself said Hoover was quite suspicious and distrustful of him and, according to author William "Mole" Wood, when Hoover discovered Popov had brought a woman from New York State

New York, also called New York State, is a state in the northeastern United States. Bordered by New England to the east, Canada to the north, and Pennsylvania and New Jersey to the south, its territory extends into both the Atlantic Ocean and ...

to Florida, threatened to have him arrested under the Mann Act if he did not leave the US immediately.

Operation Fortitude

In 1944, Popov became a key part of the deception operation codenamed Fortitude, which was when the Allies were trying to convince Germany that they (the Allies) were going to storm Calais and not Normandy. At the time of the operation, he was staying in Portugal. He stayed inEstoril

Estoril () is a town in the civil parish of Cascais e Estoril of the Portuguese Municipality of Cascais, on the Portuguese Riviera. It is a popular tourist destination, with hotels, beaches, and the Casino Estoril. It has been home to numero ...

once again, at the Hotel Palácio, between 31 March and 12 April 1944. When Jebsen was arrested by the Gestapo in Lisbon, the British feared Popov had been compromised and ceased giving him critical information to pass along to the Germans. It was later discovered that the Abwehr still regarded Popov as an asset and he was brought back into use by the British. Jebsen's death at the hands of the Nazis had a profound emotional impact on Popov.

Later life

In 1972, John Cecil Masterman published ''The Double Cross System in the War of 1939 to 1945'', an intimate account of wartime British military deception. Before its publication, Popov had no intention of revealing his wartime activities, believing that the MI6 would not allow it. Masterman's book convinced Popov that it was time to make his exploits public. In 1974, Popov published an autobiography titled ''Spy/Counterspy'', "a racy account of his adventures that read like aJames Bond

The ''James Bond'' franchise focuses on James Bond (literary character), the titular character, a fictional Secret Intelligence Service, British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels ...

novel." Russel Miller described it as "fundamentally accurate, if occasionally embellished". Several of the events described in the book were either entirely fictional, such as a fistfight Popov claimed to have had with a German agent, exaggerated for dramatic effect, or could not be substantiated through subsequently declassified intelligence records. Popov's wife and children were apparently unaware of his past until the book's publication.

By the early 1980s, years of chain smoking and heavy drinking had taken a toll on Popov's health. He died in Opio on 10 August 1981, aged 69. His family said his death came after a long illness. He was predeceased by his brother Ivo, who died in 1980. Shortly after Popov's death, MI6 began declassifying documents that pertained to Allied intelligence-gathering and disinformation activities during the war, thereby verifying many of his claims.

Legacy

Duško Popov is considered one of the main inspirations forIan Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer, best known for his postwar ''James Bond'' series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., and his ...

's James Bond novels. He was the subject of a one-hour television documentary produced by Starz Inc. and Cinenova, titled ''True Bond'', which aired in June 2007. Two other documentaries recounting Popov's exploits, ''The Real Life James Bond: Dusko Popov'' and ''Double Agent Dusko Popov: Inspiration for James Bond'', have also been produced. Popov has also been the subject of several biographies, notably Miller's ''Codename Tricycle'' (2004) and Loftis' ''Into the Lion's Mouth'' (2016).

He is the subject of numerous podcasts, including the opening season of Wondery's The spy who

',

The spy who inspired 007

' (2024).

See also

* Inspirations for James Bond * Pearl Harbor advance-knowledge debateReferences

Explanatory notes

Citations

General bibliography

* * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Official website

VOA Profile

The National Archives

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Popov, Dusan 1912 births 1981 deaths 20th-century British memoirists Abwehr personnel of World War II English people of Serbian descent Serbian Austro-Hungarians Double agents Double-Cross System People educated at Ewell Castle School People from Titel Serbian people of World War II Serbian socialites Serbian spies University of Freiburg alumni Spies World War II spies for Germany World War II spies for the United Kingdom