Dunkirk Beaches, 1940 Art on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dunkirk ( ; ; ;

A

A

The city of Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the

The city of Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the

Picard

Picard may refer to:

Places

* Picard, Quebec, Canada

* Picard, California, United States

* Picard (crater), a lunar impact crater in Mare Crisium

People and fictional characters

* Picard (name), a list of people and fictional characters with th ...

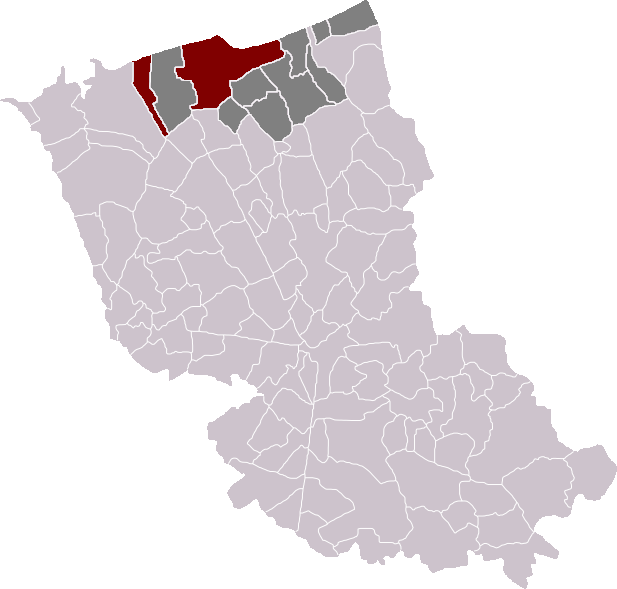

: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the department of Nord

Nord, a word meaning "north" in several European languages, may refer to:

Acronyms

* National Organization for Rare Disorders, an American nonprofit organization

* New Orleans Recreation Department, New Orleans, Louisiana, US

Film and televisi ...

in northern France. It lies from the Belgian border. It has the third-largest French harbour. The population of the commune in 2019 was 86,279.

Etymology and language use

The name of Dunkirk derives fromWest Flemish

West Flemish (''West-Vlams'' or ''West-Vloams'' or ''Vlaemsch'' (in French Flanders), , ) is a collection of Low Franconian varieties spoken in western Belgium and the neighbouring areas of France and the Netherlands.

West Flemish is spoken by ...

'dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, flat ...

' or 'dun

Dun most commonly refers to:

*Dun gene, which produces a brownish-gray color (dun) in horses and other Equidae

* Dun (fortification), an ancient or medieval fort

Dun or DUN may also refer to:

Places

Scotland

* Dun, Angus, a civil parish in ...

' and 'church', thus 'church in the dunes'. A smaller town 25 km (15 miles) farther up the Flemish coast originally shared the same name, but was later renamed Oostduinkerke

Oostduinkerke (; ; ) is a place on the southern west coast of Belgium, located in the province of West Flanders. Once a municipality of its own, Oostduinkerke now is a sub-municipality in the municipality of Koksijde.

The name ''Oostduinkerke'' ...

(n) in order to avoid confusion.

Until the middle of the 20th century, French Flemish

French Flemish (, Standard Dutch: , ) is a West Flemish dialect spoken in the north of contemporary France.

Place names attest to Flemish having been spoken since the 8th century in the part of Flanders that was ceded to France at the 1659 ...

(the local variety of Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

) was commonly spoken.

History

Middle Ages

fishing village

A fishing village is a village, usually located near a fishing ground, with an economy based on catching fish and harvesting seafood. The continents and islands around the world have coastlines totalling around 356,000 kilometres (221,000 ...

arose late in the tenth century, in the originally flooded coastal area of the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

south of the Western Scheldt

The Western Scheldt ( ), in the province of Zeeland in the southwestern Netherlands, is the estuary of the Scheldt river. This river once had several estuaries, but the others are now disconnected from the Scheldt, leaving the Westerschelde as ...

, when the area was held by the Counts of Flanders

The count of Flanders was the ruler or sub-ruler of the county of Flanders, beginning in the 9th century. Later, the title would be held for a time, by the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. During the French Revolution, in 1790, the ...

, vassals of the French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

Crown. About AD 960, Count Baldwin III had a town wall erected in order to protect the settlement against Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

raids. The surrounding wetlands were drained and cultivated by the monks of nearby Bergues

Bergues (; ; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department in northern France.

It is situated to the south of Dunkirk and from the Belgium, Belgian border. Locally it is referred to ...

Abbey. The name ''Dunkirka'' was first mentioned in a tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in money, cash, cheques or v ...

privilege of 27 May 1067, issued by Count Baldwin V of Flanders

Baldwin V ( 1012 – 1 September 1067) was Count of Flanders from 1035 until his death. He secured the personal union between the counties of Flanders and Hainaut and maintained close links to the Anglo-Saxon monarchy, which was overthrown by h ...

. Count Philip I Philip(p) I may refer to:

* Philip I of Macedon (7th century BC)

* Philip I Philadelphus (between 124 and 109 BC–83 or 75 BC)

* Philip the Arab (c. 204–249), Roman Emperor

* Philip I of France (1052–1108)

* Philip I (archbishop of Cologne) ( ...

(1157–1191) brought further large tracts of marshland under cultivation, laid out the first plans to build a Canal from Dunkirk to Bergues and vested the Dunkirkers with market rights

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

.

In the late 13th century, when the Dampierre count Guy of Flanders entered into the Franco-Flemish War

The Franco-Flemish War>(; ) was a conflict between the Kingdom of France and the County of Flanders between 1297 and 1305.

The war should be seen as related to the original Gascon War and the First War of Scottish Independence, as Philip IV of ...

against his suzerain

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy and economic relations of another subordinate party or polity, but allows i ...

King Philippe IV

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip I from ...

of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, the citizens of Dunkirk sided with the French against their count, who at first was defeated at the 1297 Battle of Furnes

The Battle of Furnes, also known as Battle of Veurne and Battle of Bulskamp, was fought on 20 August 1297 between French and Flemish forces.

The French were led by Robert II of Artois and the Flemish by Guy of Dampierre. The French forces wer ...

, but reached ''de facto'' autonomy upon the victorious Battle of the Golden Spurs

The Battle of the Golden Spurs (; ) or 1302 Battle of Courtrai was a military confrontation between the royal army of Kingdom of France, France and rebellious forces of the County of Flanders on 11 July 1302 during the 1297–1305 Franco-Flem ...

five years later and exacted vengeance. Guy's son, Count Robert III (1305–1322), nevertheless granted further city rights to Dunkirk; his successor Count Louis I Louis I may refer to:

Cardinals

* Louis I, Cardinal of Guise (1527–1578)

Counts

* Ludwig I, Count of Württemberg (c. 1098–1158)

* Louis I of Blois (1172–1205)

* Louis I of Flanders (1304–1346)

* Louis I of Châtillon (died 13 ...

(1322–1346) had to face the Peasant revolt of 1323–1328, which was crushed by King Philippe VI of France at the 1328 Battle of Cassel, whereafter the Dunkirkers again were affected by the repressive measures of the French king.

Count Louis remained a loyal vassal of the French king upon the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

with England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

in 1337, and prohibited the maritime trade, which led to another revolt by the Dunkirk citizens. After the count had been killed in the 1346 Battle of Crécy

The Battle of Crécy took place on 26 August 1346 in northern France between a French army commanded by King PhilipVI and an English army led by King Edward III. The French attacked the English while they were traversing northern France ...

, his son and successor Count Louis II of Flanders

Louis II (; ) (25 October 1330, Male – 30 January 1384, Lille), also known as Louis of Male, a member of the House of Dampierre, was Count of Flanders, Count of Nevers, and Count of Rethel from 1346 to 1384, and also Count of Artois and C ...

(1346–1384) signed a truce with the English; the trade again flourished and the port was significantly enlarged. However, in the course of the Western Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Great Occidental Schism, the Schism of 1378, or the Great Schism (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 20 September 1378 to 11 November 1417, in which bishops residing ...

from 1378, English supporters of Pope Urban VI

Pope Urban VI (; ; c. 1318 – 15 October 1389), born Bartolomeo Prignano (), was head of the Catholic Church from 8 April 1378 to his death, in October 1389. He was the last pope elected from outside the College of Cardinals. His pontificate be ...

(the Roman claimant) disembarked at Dunkirk, captured the city and flooded the surrounding estates. They were ejected by King Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved () and in the 19th century, the Mad ( or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychosis, psychotic episodes t ...

, but left great devastations in and around the town.

Upon the extinction of the Counts of Flanders with the death of Louis II in 1384, Flanders was acquired by the Burgundian, Duke Philip the Bold

Philip II the Bold (; ; 17 January 1342 – 27 April 1404) was Duke of Burgundy and ''jure uxoris'' Count of Flanders, Artois and Burgundy. He was the fourth and youngest son of King John II of France and Bonne of Luxembourg.

Philip was th ...

. The fortifications were again enlarged, including the construction of a belfry daymark

A daymark is a navigational aid for sailors and maritime pilot, pilots, distinctively marked to maximize its visibility in daylight.

The word is also used in a more specific, technical sense to refer to a signboard or daytime identifier that ...

(a navigational aid similar to a non-illuminated lighthouse). As a strategic point, Dunkirk has always been exposed to political greed, by Duke Robert I of Bar

Robert I of Bar (8 November 1344 – 12 April 1411) was Marquis of Pont-à-Mousson and Count and then Duke of Bar. He succeeded his elder brother Edward II of Bar as count in 1352. His parents were Henry IV of Bar and Yolande of Flanders.

Wh ...

in 1395, by Louis de Luxembourg in 1435 and finally by the Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example:

** Austria-Hungary

** Austria ...

archduke Maximilian I of Habsburg

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519. He was never crowned by the Pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians. He proclaimed hi ...

, who in 1477 married Mary of Burgundy

Mary of Burgundy (; ; 13 February 1457 – 27 March 1482), nicknamed the Rich, was a member of the House of Valois-Burgundy who ruled the Burgundian lands, comprising the Duchy of Burgundy, Duchy and Free County of Burgundy, County of Burgundy a ...

, sole heiress of late Duke Charles the Bold

Charles Martin (10 November 1433 – 5 January 1477), called the Bold, was the last duke of Burgundy from the House of Valois-Burgundy, ruling from 1467 to 1477. He was the only surviving legitimate son of Philip the Good and his third wife, ...

. As Maximilian was the son of Emperor Frederick III, all Flanders was immediately seized by King Louis XI of France

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII. Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revolt known as the ...

. However, the archduke defeated the French troops in 1479 at the Battle of Guinegate. When Mary died in 1482, Maximilian retained Flanders according to the terms of the 1482 Treaty of Arras. Dunkirk, along with the rest of Flanders, was incorporated into the Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands were the parts of the Low Countries that were ruled by sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. This rule began in 1482 and ended for the Northern Netherlands in 1581 and for the Southern Netherlands in 1797. ...

and upon the 1581 secession of the Seven United Netherlands, remained part of the Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands, also called the Catholic Netherlands, were the parts of the Low Countries belonging to the Holy Roman Empire which were at first largely controlled by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1556–1714) and later by the ...

, which were held by Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Rex Catholicissimus, Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In t ...

(Spanish Netherlands) as Imperial fiefs.

Corsair base

The area remained much disputed betweenSpain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. At the beginning of the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

, Dunkirk was briefly in the hands of the Dutch rebels, from 1577. Spanish forces under Duke Alexander Farnese of Parma

Parma (; ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmesan, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,986 inhabitants as of 2025, ...

re-established Spanish rule in 1583 and it became a base for the notorious ''Dunkirkers''. The Dunkirkers briefly lost their home port when the city was conquered by the French in 1646 but Spanish forces recaptured the city in 1652. In 1658, as a result of the long war between France and Spain, it was captured after a siege by Franco-English forces following the battle of the Dunes. The city along with Fort-Mardyck

Fort-Mardyck (; ; ) is a former Communes of France, commune in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department in northern France. It has been part of the commune of Dunkirk since 9 December 2010. In 2022 it had 3,491 inhabi ...

was awarded to England in the peace the following year as agreed in the Franco-English alliance against Spain. The English governors were Sir William Lockhart (1658–60), Sir Edward Harley

Sir Edward Harley (21 October 1624 – 8 December 1700) was an English politician from Herefordshire. A devout Puritan who fought for Parliament in the First English Civil War, Harley belonged to the moderate Presbyterian faction, which oppose ...

(1660–61) and Lord Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nuclear physics", ...

(1661–62).

On 17 October 1662, Dunkirk was sold to France by Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651 and King of England, Scotland, and King of Ireland, Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest su ...

for £320,000. The French government developed the town as a fortified port. The town's existing defences were adapted to create ten bastions. The port was expanded in the 1670s by the construction of a basin that could hold up to thirty warships with a double lock system to maintain water levels at low tide. The basin was linked to the sea by a channel dug through coastal sandbanks secured by two jetties. This work was completed by 1678. The jetties were defended a few years later by the construction of five forts, Château d'Espérance, Château Vert, Grand Risban, Château Gaillard, and Fort de Revers. An additional fort was built in 1701 called Fort Blanc.

During the reign of Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, a large number of commerce raider

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a fo ...

s and pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

s once again made their base at Dunkirk, the most famous of whom was Jean Bart

Jean Bart (; ; 21 October 1650 – 27 April 1702) was a Flemish naval commander and privateer.

Early life

Jean Bart was born in Dunkirk in 1650 to a seafaring family, the son of Jean-Cornil Bart (c. 1619–1668) who has been described various ...

. The main character (and possible real prisoner) in the famous novel Man in the Iron Mask

The Man in the Iron Mask (; died 19 November 1703) was an unidentified prisoner of state during the reign of Louis XIV of France (1643–1715). The strict measures taken to keep his imprisonment secret resulted in a long-lasting legend about ...

by Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

was arrested at Dunkirk. The eighteenth-century Swedish privateers and pirates Lars Gathenhielm

Lars Gathenhielm (originally Lars Andersson Gathe; 1689–1718) was a Swedish sea captain, commander, shipowner, merchant, and privateer.

Biography

Lars Gathenhielm was born on the Gatan estate in Onsala Parish in Halland. His parents were ...

and his wife Ingela Hammar are known to have sold their gains in Dunkirk.

As France and Great Britain became commercial and military rivals, the British grew concerned about Dunkirk being used as an invasion base to cross the English Channel. The jetties, their forts, and the port facilities were demolished in 1713 under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

. The Treaty of Paris of 1763, which concluded the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, included a clause restricting French rights to fortify Dunkirk. This clause was overturned in the subsequent Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

of 1783.

Dunkirk in World War I

Dunkirk's port was used extensively during the war by British forces who brought in dock workers from, among other places, Egypt and China. From 1915, the city experienced severe bombardment, including from the largest gun in the world in 1917, the German ' Lange Max'. On a regular basis, heavy shells weighing approximately 750 kg (1700 lb) were fired fromKoekelare

Koekelare (; ) is a municipality located in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the towns of Bovekerke, Koekelare proper and Zande. On 1 January 2006 Koekelare had a total population of 8,291. The total area is 39.1 ...

, about 45–50 km (30 miles) away. The bombardment killed nearly 600 people and wounded another 1,100, both civilian and military, while 400 buildings were destroyed and 2,400 damaged. The city's population, which had been 39,000 in 1914, reduced to fewer than 15,000 in July 1916 and 7,000 in the autumn of 1917.

In January 1916, a spy scare took place in Dunkirk. The writer Robert W. Service

Robert William Service (16 January 1874 – 11 September 1958) was an English-born Canadian poet and writer, often called “The Poet of the Yukon" and "The Canadian Kipling". Born in Lancashire of Scottish descent, he was a bank clerk by trade ...

, then a war correspondent for the ''Toronto Star

The ''Toronto Star'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet daily newspaper. It is owned by Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary of Torstar Corporation and part of Torstar's Daily News Brands (Torstar), Daily News Brands division.

...

'', was mistakenly arrested as a spy and narrowly avoided being executed out of hand. On 1 January 1918, the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

established a naval air station

A Naval Air Station (NAS) is a military air base, and consists of a permanent land-based operations locations for the military aviation division of the relevant branch of a navy (Naval aviation). These bases are typically populated by squadron ...

to operate seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

s. The base closed shortly after the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed in a railroad car, in the Compiègne Forest near the town of Compiègne, that ended fighting on land, at sea, and in the air in World War I between the Entente and their las ...

.

In October 1917, to mark the gallant behaviour of its inhabitants during the war, the City of Dunkirk was awarded the and, in 1919, the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

and the British Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

*Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

*Distinguished Service Cross (U ...

. These decorations now appear in the city's coat of arms.

Dunkirk in World War II

Evacuation

During theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

1940 Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), while aiding the French and Belgian armies, were forced to retreat in the face of overpowering German Panzer attacks. Fighting in Belgium and France, the BEF and a portion of the French Army became outflanked by the Germans and retreated to the area around the port of Dunkirk. More than 400,000 soldiers were trapped in the pocket as the German Army closed in for the kill. Unexpectedly, the German Panzer attack halted for several days at a critical juncture. For years, it was assumed that Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

ordered the German Army to suspend the attack, favouring bombardment by the Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

. However, according to the Official War Diary of Army Group A

Army Group A () was the name of three distinct army groups of the ''German Army (1935–1945), Heer'', the ground forces of the ''Wehrmacht'', during World War II.

The first Army Group A, previously known as "Army Group South", was active from Oct ...

, its commander, ''Generaloberst

A ("colonel general") was the second-highest general officer rank in the German '' Reichswehr'' and ''Wehrmacht'', the Austro-Hungarian Common Army, the East German National People's Army and in their respective police services. The rank w ...

'' Gerd von Rundstedt

Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt (12 December 1875 – 24 February 1953) was a German ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (Field Marshal) in the ''German Army (1935–1945), Heer'' (Army) of Nazi Germany and OB West, ''Oberbefehlshaber West'' (Commande ...

, ordered the halt to allow maintenance on his tanks, half of which were out of service, and to protect his flanks which were exposed and, he thought, vulnerable. Hitler merely validated the order several hours later. This lull gave the British and French a few days to fortify their defences. The Allied position was complicated by Belgian King Leopold III's surrender on 27 May, which was postponed until 28 May. The gap left by the Belgian Army stretched from Ypres to Dixmude. Nevertheless, a collapse was prevented, making it possible to launch an evacuation by sea, across the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

, codenamed Operation Dynamo. British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet, and selects its ministers. Modern pri ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

ordered any ship or boat available, large or small, to collect the stranded soldiers. 338,226 men (including 123,000 French soldiers) were evacuated – the ''miracle of Dunkirk'', as Churchill called it. It took over 900 vessels to evacuate the BEF, with two-thirds of those rescued embarking via the harbour, and over 100,000 taken off the beaches. More than 40,000 vehicles as well as massive amounts of other military equipment and supplies were left behind. Forty thousand Allied soldiers (some who carried on fighting after the official evacuation) were captured or forced to make their own way home through a variety of routes including via neutral Spain. Many wounded who were unable to walk were abandoned.

Liberation

The city of Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the

The city of Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division

The 2nd Canadian Division, an infantry Division (military), division of the Canadian Army, was mobilized for war service on 1September 1939 at the outset of World War II. Adopting the designation of the 2nd Canadian Division, it was initially c ...

attempting to liberate the city in September, as Allied forces surged northeast after their victory in the Battle of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the N ...

. However, German forces refused to relinquish their control of the city, which had been converted into a fortress. To seize the now strategically insignificant town would consume too many Allied resources which were needed elsewhere. The town was by-passed masking the German garrison with Allied troops, notably the 1st Czechoslovak Armoured Brigade

The 1st Czechoslovak Independent Armoured Brigade Group () was an armoured unit of expatriate Czechoslovaks organised and equipped by the United Kingdom during the Second World War in 1943.

The brigade landed in Normandy in August 1944 and was gi ...

. During the German occupation

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the government of Nazi Germany at ...

, Dunkirk was largely destroyed by Allied bombing. The artillery siege of Dunkirk was directed on the final day of the war by pilots from No. 652 Squadron RAF, and No. 665 Squadron RCAF. The fortress, under the command of German Admiral Friedrich Frisius

Friedrich Frisius (17 January 1895 – 30 August 1970) was a German naval commander of World War II.

Life

Pre WWII

Born in 1895 in Bad Salzuflen, son of the Lutheran pastor Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Frisius and his wife Karoline Luise Antoinette, F ...

, eventually unconditionally surrendered to the commander of the Czechoslovak forces, Brigade General Alois Liška, on 9 May 1945.

Postwar Dunkirk

On 14 December 2002, the Norwegiancar carrier

Roll-on/roll-off (RORO or ro-ro) ships are cargo ships designed to carry wheeled cargo, such as cars, motorcycles, trucks, semi-trailer trucks, buses, trailers, and railroad cars, that are driven on and off the ship on their own wheels or usin ...

collided with the Bahamian-registered ''Kariba'' and sank off Dunkirk Harbour, causing a hazard to navigation in the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

.

Population

The population data in the table and graph below refer to the commune of Dunkirk proper, in its geography at the given years. The commune of Dunkirk absorbed the former commune of Malo-les-Bains in 1969, Rosendaël and Petite-Synthe in 1971,Mardyck

Mardyck ( Dutch: ''Mardijk'', ) is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. It is an associated commune with Dunkirk since it joined the latter in January 1980.Fort-Mardyck

Fort-Mardyck (; ; ) is a former Communes of France, commune in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department in northern France. It has been part of the commune of Dunkirk since 9 December 2010. In 2022 it had 3,491 inhabi ...

and Saint-Pol-sur-Mer

Saint-Pol-sur-Mer (, literally ''Saint-Pol on Sea''; ; Picard: ''Saint-Po-dsu-Mér'') is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. Since 9 December 2010, it is part of the commune of Dunkirk.Nord's 13th constituency, The current Member of Parliament is Christine Decodts of the

The commune has grown substantially by absorbing several neighbouring communes:

* 1970: Merger with Malo-les-Bains (which had been created by being detached from Dunkirk in 1881)

* 1972: Fusion with Petite-Synthe and Rosendaël (the latter had been created by being detached from

The commune has grown substantially by absorbing several neighbouring communes:

* 1970: Merger with Malo-les-Bains (which had been created by being detached from Dunkirk in 1881)

* 1972: Fusion with Petite-Synthe and Rosendaël (the latter had been created by being detached from

miscellaneous centre

Miscellaneous centre (''Divers centre'', ''DVC'') in the nation of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guian ...

.

Presidential elections second round

Heraldry

Administration

Téteghem

Téteghem (; Dutch and ) is a former commune in the Nord department, northern France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune Téteghem-Coudekerque-Village.associated commune, with a population of 372 in 1999)

* 1980: A large part of Petite-Synthe is detached from Dunkirk and included into

In June 1792 the French astronomers Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre and Pierre Méchain, Pierre François André Méchain set out to measure the meridian arc distance from Dunkirk to Barcelona, two cities lying on approximately the same longitude as each other and also the longitude through Paris. The belfry was chosen as the reference point in Dunkirk.

Using this measurement and the latitudes of the two cities they could calculate the distance between the North Pole and the Equator in classical French units of length and hence produce the first prototype metre which was defined as being one ten millionth of that distance. The definitive metre bar, manufactured from platinum, was presented to the French legislative assembly on 22 June 1799.

Dunkirk was the most easterly cross-channel measuring point for the Anglo-French Survey (1784–1790), which used triangulation to calculate the precise distance between the Paris Observatory and the Royal Greenwich Observatory. Sightings were made of signal lights at Dover Castle from the Dunkirk Belfry, and vice versa.

In June 1792 the French astronomers Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre and Pierre Méchain, Pierre François André Méchain set out to measure the meridian arc distance from Dunkirk to Barcelona, two cities lying on approximately the same longitude as each other and also the longitude through Paris. The belfry was chosen as the reference point in Dunkirk.

Using this measurement and the latitudes of the two cities they could calculate the distance between the North Pole and the Equator in classical French units of length and hence produce the first prototype metre which was defined as being one ten millionth of that distance. The definitive metre bar, manufactured from platinum, was presented to the French legislative assembly on 22 June 1799.

Dunkirk was the most easterly cross-channel measuring point for the Anglo-French Survey (1784–1790), which used triangulation to calculate the precise distance between the Paris Observatory and the Royal Greenwich Observatory. Sightings were made of signal lights at Dover Castle from the Dunkirk Belfry, and vice versa.

File:Dunkerque Tour du Leughenaer.jpg, The Tour du Leughenaer () (the Liar's Tower)

File:Dunkerque Town Hall.jpg, The Hôtel de Ville

File:Carnaval dunkerque.jpg, Carnival in Dunkirk

File:Jielbeaumadier Dunkerque 2007 25.jpeg, Malo-les-Bains beach front

File:Dunkerque (plage).jpg, Dunkirk Beach

File:East Mole Dunkirk.jpg, The remains of the East Mole of Dunkirk harbour, pictured in 2009

File:Léon Germain Pelouse, La Vallée de Cernay, 1873, Dunkerque, Musée des Beaux-Arts.jpg, Léon Germain Pelouse, ''La Vallée de Cernay'', 1873, Musée des Beaux-Arts

As of August 2019, approximately 5% of 2000 people surveyed had used the free bus service to completely replace their cars.

*

*

City council website

Tourist office website

{{Authority control Dunkirk, Communes of Nord (French department) France–United Kingdom border crossings Port cities and towns on the French Atlantic coast Port cities and towns of the North Sea Subprefectures in France Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Juxtaposed border controls Pirate dens and locations Vauban fortifications in France French Flanders

Grande-Synthe

Grande-Synthe (; ) is a commune in the Nord department in the Nord-Pas de Calais region in northern France.

It is the third-largest suburb of the city of Dunkerque (Dunkirk) and lies adjacent to it on the west.

History

In 1980, a large par ...

* 2010: After a failed fusion-association attempt with Saint-Pol-sur-Mer

Saint-Pol-sur-Mer (, literally ''Saint-Pol on Sea''; ; Picard: ''Saint-Po-dsu-Mér'') is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. Since 9 December 2010, it is part of the commune of Dunkirk.Fort-Mardyck

Fort-Mardyck (; ; ) is a former Communes of France, commune in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department in northern France. It has been part of the commune of Dunkirk since 9 December 2010. In 2022 it had 3,491 inhabi ...

in 2003, both successfully become associated communes with Dunkirk in December 2010.

Economy

Dunkirk has the third-largest harbour in France, after those ofLe Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

and Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

. As an industrial city, it depends heavily on the steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

, food processing, oil refining, oil-refining, ship-building and chemical industry, chemical Industry (economics), industries.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Dunkirk closely resembles Flemish Belgian cuisine, cuisine; perhaps one of the best known dishes is ''coq à la bière'' – chicken in a creamy beer sauce.Prototype metre

Tourist attractions

Two belfries in Dunkirk (the belfry near the Church of Saint-Éloi, Dunkirk, Church of Saint-Éloi and the one at the Hôtel de Ville, Dunkirk, Hôtel de Ville) are part of a group of belfries of Belgium and France, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2005 in recognition of their civic architecture and importance in the rise of municipal power in Europe. The 63-meter-high Dunkirk Lighthouse, also known as the Risban Light, was built between 1838 and 1843 as part of early efforts to place lights around the coast of France. At the time of its construction it was one of only two first order lighthouses (the other being Calais) to be set up in a port. Automated since 1985, the light can be seen 28 nautical miles (48 km) away. In 2010 it was listed as an historical monument. Two museums in Dunkirk include: * The ''Musée Portuaire'', which displays exhibits of images about the history and presence of the port. * The ''Musée des Beaux-Arts'', which has a large collection of Flemish, Italian and French paintings and sculptures.Transport

Dunkirk has a ferry route to Dover that is run by DFDS, which serves as an alternative to the route to the service to nearby Calais. The Dover-Dunkirk ferry route takes two hours compared to Dover-Calais' 1 hour 30 minutes, is run by MS Dunkerque Seaways, thMS Delft Seaways, rMS Dover Seaways, ee vessels and runs every two hours from Dunkirk. Another DFDS route connects Dunkirk to Rosslare Europort in the Republic of Ireland and carries truck freight as well as a limited number of private car passengers. The Dunkirk-Rosslare route take 24 hours and is run by the MF ''Regina Seaways''. The Gare de Dunkerque railway station offers connections to Gare de Calais-Ville, Gare de Lille Flandres, Arras and Paris, and several regional destinations in France. The railway line from Dunkirk to De Panne and Adinkerke, Belgium, is closed and has been dismantled in places. In September 2018, Dunkirk's public transit service introduced free public transport, thereby becoming the largest city in Europe to do so. Several weeks after the scheme had been introduced, the city's mayor, Patrice Vergriete, reported that there had been 50% increase in passenger numbers on some routes, and up to 85% on others. As part of the transition towards offering free bus services, the city's fleet was expanded from 100 to 140 buses, including new vehicles which run on natural gas. The Dunkirk free public transport initiative, initially lauded for its bold ambition, saw a significant decline in ridership after the initial surge. While the first three months post-launch demonstrated a dramatic increase in usage, with some lines experiencing up to 120% higher demand on weekends, the system faced substantial challenges. By the end of the first three months, ridership plummeted by 73% from its peak, eventually stabilizing at only 12% more than pre-pandemic levels (2019-2020). This decline was primarily due to the inability of the public transport infrastructure to handle the overwhelming demand, leading to overcrowding, delays, and reduced service quality. Despite these issues, Dunkirk’s free transport program remains operational, albeit limited to weekends, a marked reduction from its original full-time service. This scaling back underscores the difficulties in maintaining such an ambitious project, with financial constraints and logistical inefficiencies contributing to its partial rollback. While the program succeeded in increasing mobility for low-income residents and reducing car usage initially, its long-term sustainability has been questioned, casting doubt on its viability as a model for other cities. (https://www.goodnewsnetwork.org/after-becoming-largest-european-city-to-offer-free-public-transit-theyre-enjoying-a-revolution-from-their-buses/)As of August 2019, approximately 5% of 2000 people surveyed had used the free bus service to completely replace their cars.

Sports

* USL Dunkerque, French football (soccer), football club, currently playing in Ligue 2. * The Four Days of Dunkirk (or ''Quatre Jours de Dunkerque'') is an important elite professional road bicycle racing event. * Stage 2 of the 2007 Tour de France departed from Dunkirk.Notable residents

*

* Jean Bart

Jean Bart (; ; 21 October 1650 – 27 April 1702) was a Flemish naval commander and privateer.

Early life

Jean Bart was born in Dunkirk in 1650 to a seafaring family, the son of Jean-Cornil Bart (c. 1619–1668) who has been described various ...

(1650—1702), naval commander and privateer

* Eugène Chigot, 19th-century post impressionist painter

* Marvin Gakpa (born 1993), footballer

* Louise Lavoye (1823—1897), 19th-century soprano

* Robert Malm (born 1973), footballer

* Jean-Paul Rouve (born 1967), actor

* François Rozenthal (born 1975), ice hockey player

* Maurice Rozenthal (born 1975), ice hockey player

* Djoumin Sangaré (born 1983), footballer

* Tancrède Vallerey (born 1892, date of death unknown), writer

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Dunkirk is Twin towns and sister cities, twinned with: * Krefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany since 15 June 1974 * Middlesbrough, England, United Kingdom since 12 April 1976 * Gaza City, Gaza, Palestine since 2 April 1996 * Rostock, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany since 9 April 2000 * Ramat HaSharon, Israel since 15 September 1997 * Qinhuangdao, Hebei, China since 25–26 September 2000Friendship links

Dunkirk has co-operation agreements with: * Borough of Dartford, Dartford, Kent, England, United Kingdom since March 1988 * Thanet District, Thanet, Kent, England, United Kingdom since 18 June 1993Climate

Dunkirk has an oceanic climate, with cool winters and warm summers. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Dunkirk has a marine west coast climate, abbreviated "Cfb" on climate maps. Summer high temperatures average around , being significantly influenced by the marine currents.See also

* Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine * Dunkirkers * French Flanders *French Flemish

French Flemish (, Standard Dutch: , ) is a West Flemish dialect spoken in the north of contemporary France.

Place names attest to Flemish having been spoken since the 8th century in the part of Flanders that was ceded to France at the 1659 ...

* Hortense Clémentine Tanvet

* Liberation of France

* Treaty of Dunkirk

* Flanders bank

References

External links

City council website

Tourist office website

{{Authority control Dunkirk, Communes of Nord (French department) France–United Kingdom border crossings Port cities and towns on the French Atlantic coast Port cities and towns of the North Sea Subprefectures in France Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Juxtaposed border controls Pirate dens and locations Vauban fortifications in France French Flanders