Douglas Hyde on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

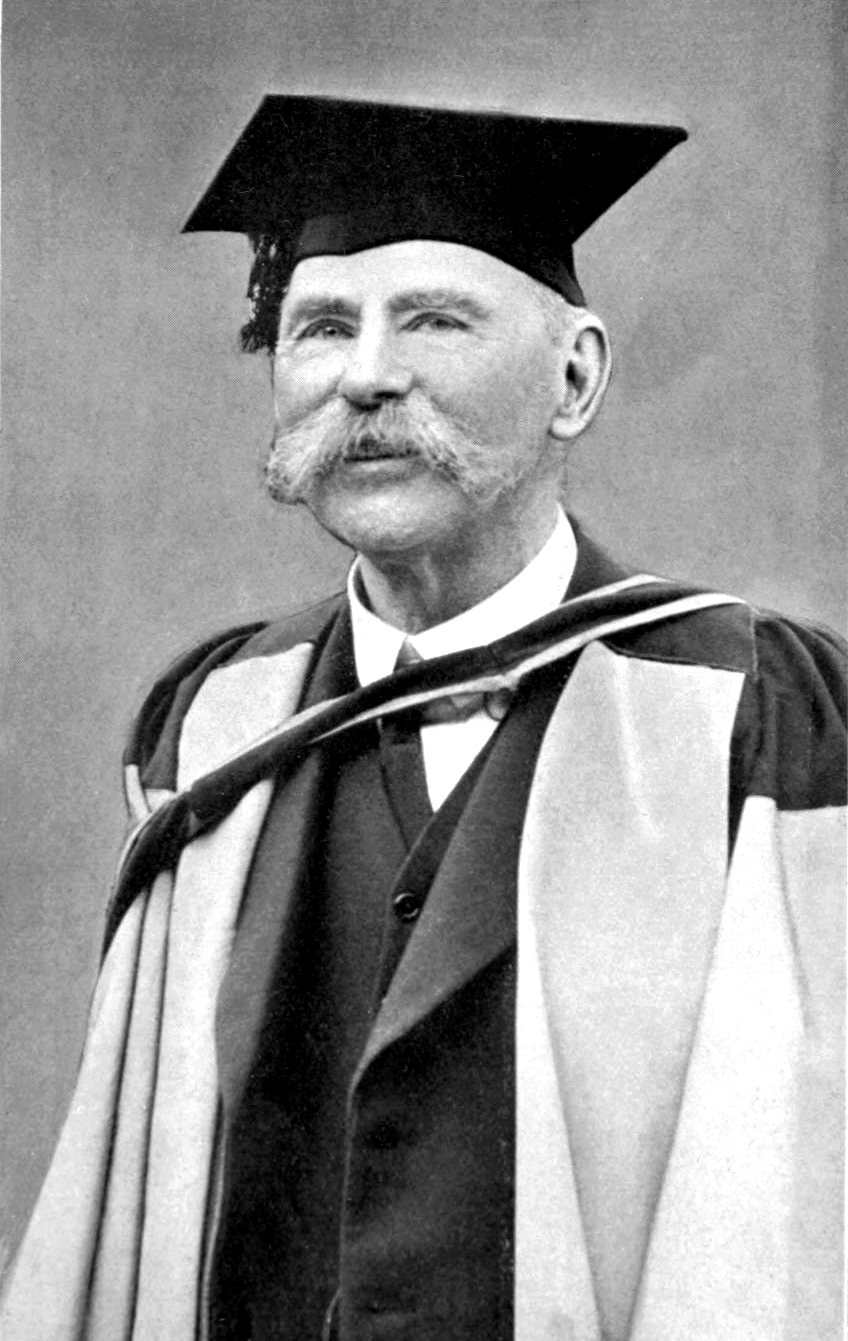

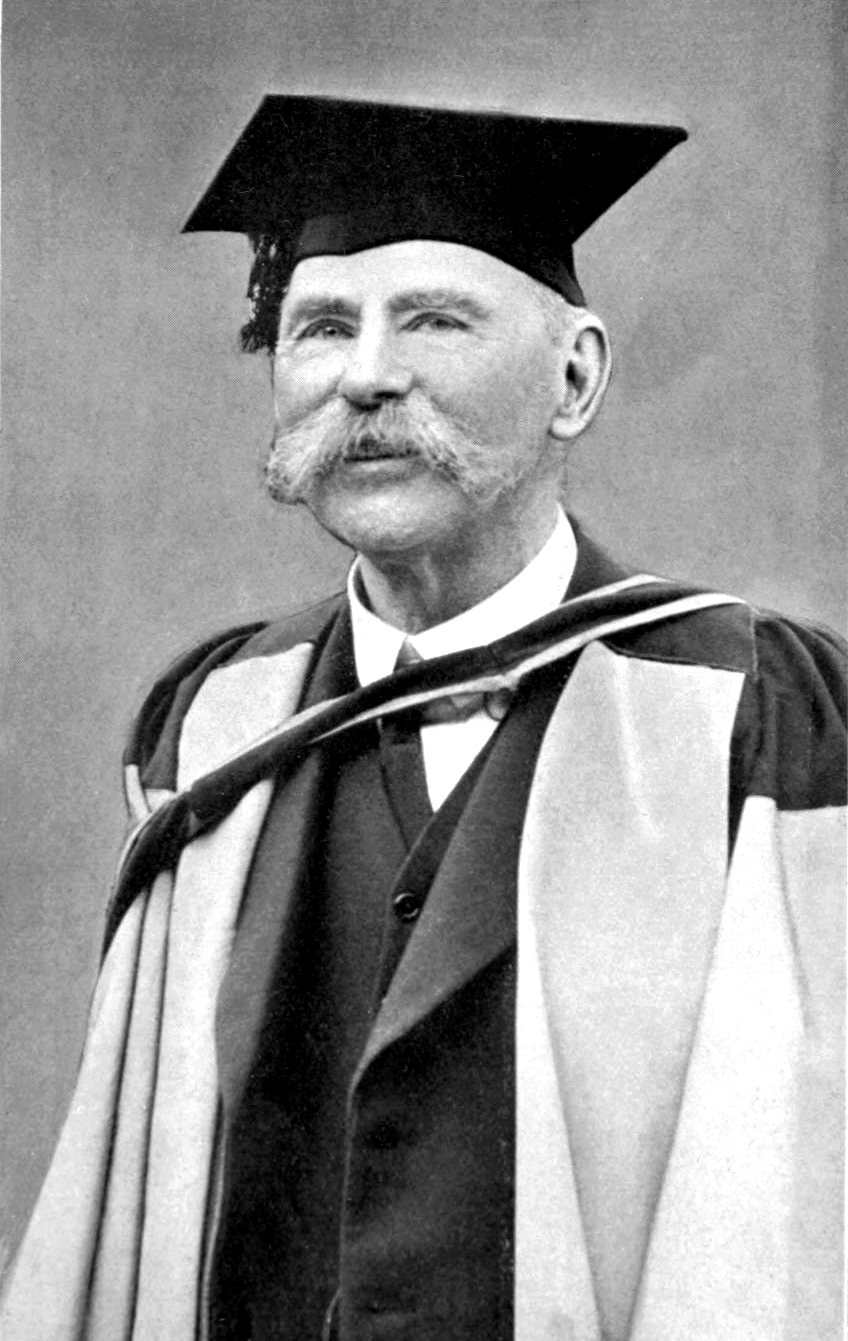

Douglas Ross Hyde (; 17 January 1860 – 12 July 1949), known as (), was an Irish academic, linguist, scholar of the Irish language, politician, and diplomat who served as the first

In 1867, his father was appointed

In 1867, his father was appointed

Initially derided, the Irish language movement gained a mass following. Hyde helped establish the '' Gaelic Journal'' in 1892; in November, he wrote a manifesto called ''The necessity for de-anglicising the Irish nation'', arguing that Ireland should follow its own traditions in language, literature, and dress.

In 1893, he helped found Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League) to encourage the preservation of Irish culture, music, dance and language. A new generation of Irish republicans (including Pádraig Pearse,

Initially derided, the Irish language movement gained a mass following. Hyde helped establish the '' Gaelic Journal'' in 1892; in November, he wrote a manifesto called ''The necessity for de-anglicising the Irish nation'', arguing that Ireland should follow its own traditions in language, literature, and dress.

In 1893, he helped found Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League) to encourage the preservation of Irish culture, music, dance and language. A new generation of Irish republicans (including Pádraig Pearse,

Hyde had no association with

Hyde had no association with

Hyde was inaugurated as the first President of Ireland, on 26 June 1938. ''

Hyde was inaugurated as the first President of Ireland, on 26 June 1938. ''

the General Elections (Emergency Powers) Act 1943

legislation under the emergency provisions of Article 28.3.3°), which allowed an election to be called separate from a dissolution, with the Dáil only being dissolved just before new Dáil would assemble. This ensured the gap between Dála (plural of Dáil) would be too short to cause a vacuum in major decision-making. Under the Act, the President could "refuse to proclaim a general election on the advice of a Taoiseach who had ceased to retain the support of a majority in Dáil Éireann". Hyde had that option but, after considering it with his senior advisor Michael McDunphy, he granted the dissolution. Hyde twice used his prerogative under Article 26 of the Constitution, having consulted the

Biography at Áras an Uachtaráin websiteOireachtas Members Database – Profile

*Dunleavy, Janet Egleson and Gareth W. Dunleavy. ''Douglas Hyde: A Maker of Modern Ireland''. Berkeley et al.: Univ. of California Press, 1991

Available from eScholarship

*Hyde, Douglas. ''The Love Songs of Connacht: Being the Fourth Chapter of the Songs of Connacht''. Dundrum, Ireland: Dun Emer Press, 1904

Available from Google Books

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hyde, Douglas 1860 births 1949 deaths Academics of University College Dublin Alumni of Trinity College Dublin 19th-century Anglo-Irish people 20th-century Anglo-Irish people Celtic studies scholars Conradh na Gaeilge presidents Independent members of Seanad Éireann Irish Anglicans Irish folklorists Irish language activists Irish-language writers 19th-century Irish poets 20th-century Irish poets Members of the 1922 Seanad Members of the 2nd Seanad Nominated members of Seanad Éireann Patrons of the Gaelic Athletic Association People from Castlerea Scholars and academics from County Sligo Presidents of Ireland Scholars and academics from County Roscommon People from Frenchpark 20th-century presidents in Europe People on Irish postage stamps

president of Ireland

The president of Ireland () is the head of state of Republic of Ireland, Ireland and the supreme commander of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Irish Defence Forces. The presidency is a predominantly figurehead, ceremonial institution, serving as ...

from June 1938 to June 1945. He was a leading figure in the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival () was the late-nineteenth-century national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including folklore, mythology, sports, music, arts, etc.). Irish had diminished as a sp ...

, and the first president of the Gaelic League

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it eme ...

, one of the most influential cultural organisations in Ireland at the time.

Background

Hyde was born at Longford House in Castlerea,County Roscommon

County Roscommon () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is part of the province of Connacht and the Northern and Western Region. It is the List of Irish counties by area, 11th largest Irish county by area and Li ...

, while his mother, Elizabeth Hyde (née Oldfield; 1834–1886), was on a short visit. His father, Arthur Hyde, whose family was originally from Castlehyde near Fermoy

Fermoy () is a town on the Munster Blackwater, River Blackwater in east County Cork, Ireland. As of the 2022 census of Ireland, 2022 census, the town and environs had a population of approximately 6,700 people. It is located in the barony (Ir ...

, County Cork

County Cork () is the largest and the southernmost Counties of Ireland, county of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, named after the city of Cork (city), Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster ...

, was Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland (, ; , ) is a Christian church in Ireland, and an autonomy, autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the Christianity in Ireland, second-largest Christian church on the ...

rector of Kilmactranny, County Sligo

County Sligo ( , ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region and is part of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. Sligo is the administrative capital and largest town in ...

, from 1852 to 1867, and it was here that Hyde spent his early years. Arthur Hyde and Elizabeth Oldfield married in County Roscommon

County Roscommon () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is part of the province of Connacht and the Northern and Western Region. It is the List of Irish counties by area, 11th largest Irish county by area and Li ...

, in 1852, and had three other children: Arthur Hyde (1853–79 in County Leitrim

County Leitrim ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht and is part of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the village of Leitrim, County Leitr ...

), John Oldfield Hyde (1854–96 in County Dublin

County Dublin ( or ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland, and holds its capital city, Dublin. It is located on the island's east coast, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. Until 1994, County Dubli ...

), and Hugh Hyde (1856).

In 1867, his father was appointed

In 1867, his father was appointed prebendary

A prebendary is a member of the Catholic Church, Catholic or Anglicanism , Anglican clergy, a form of canon (priest) , canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in part ...

and rector of Tibohine, and the family moved to neighbouring Frenchpark, in County Roscommon. He was home-schooled by his father and his aunt due to a childhood illness. While a young man, he became fascinated with hearing the old people in the locality speak the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

. He was influenced in particular by the gamekeeper Séamus Hart and his friend's wife, Mrs. Connolly. Aged 14, Hyde was devastated when Hart died, and his interest in the Irish language—the first language he began to study in any detail, as his own undertaking—flagged for a while. However, he visited Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

several times and realised that there were groups of people, just like him, interested in Irish, a language looked down on at the time by many and seen as backward and old-fashioned.

Rejecting family pressure that, like past generations of Hydes, he would follow a career as an Anglican clergyman, Hyde instead became an academic. He entered Trinity College Dublin

Trinity College Dublin (), officially titled The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, and legally incorporated as Trinity College, the University of Dublin (TCD), is the sole constituent college of the Unive ...

, where he became fluent in French, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, German, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, and Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, graduating in 1884 as a moderator in modern literature. A medallist of the College Historical Society

The College Historical Society (CHS) – popularly referred to as The Hist – is a debating society at Trinity College Dublin. It was established within the college in 1770 and was inspired by the club formed by the philosopher Edmund ...

, he was elected its president in 1931. His passion for the language revival of Irish, which was already in severe decline, led him to help found the Gaelic League

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it eme ...

, or in Irish, , in 1893.

Hyde married German-born but British-raised Lucy Kurtz in 1893. The couple had two daughters, Nuala and Úna.

Conradh na Gaeilge/Gaelic League

Hyde joined the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language around 1880, and between 1879 and 1884, he published more than a hundred pieces of Irish verse under thepen name

A pen name or nom-de-plume is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen name may be used to make the author's na ...

().

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

, Michael Collins and Ernest Blythe), became politicised through their involvement in Conradh na Gaeilge. Hyde filled out the 1911 census form in Irish.

Uncomfortable with the growing politicisation of the movement, Hyde resigned the presidency in 1915. He was succeeded by the League's co-founder Eoin MacNeill

Eoin MacNeill (; born John McNeill; 15 May 1867 – 15 October 1945) was an Irish scholar, Irish language enthusiast, Gaelic revivalist, nationalist, and politician who served as Minister for Education from 1922 to 1925, Ceann Comhairle of D ...

.

Senator

Hyde had no association with

Hyde had no association with Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

and the independence movement. He was elected to Seanad Éireann

Seanad Éireann ( ; ; "Senate of Ireland") is the senate of the Oireachtas (the Irish legislature), which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann (defined as the house of representatives).

It is commonly called the Seanad or ...

, the upper house of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

's Oireachtas

The Oireachtas ( ; ), sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the Bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of the president of Ireland and the two houses of the Oireachtas (): a house ...

(parliament), at a by-election on 4 February 1925, replacing Sir Hutcheson Poë.

In the 1925 Seanad election, Hyde placed 28th of the 78 candidates, with 19 seats available. The Catholic Truth Society opposed him for his Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and publicised his supposed support for divorce. Historians have suggested that the CTS campaign was ineffective, and that Irish-language advocates performed poorly, with all those endorsed by the Gaelic League losing.

He returned to academia as Professor of Irish at University College Dublin

University College Dublin (), commonly referred to as UCD, is a public research university in Dublin, Ireland, and a collegiate university, member institution of the National University of Ireland. With 38,417 students, it is Ireland's largest ...

, where one of his students was future Attorney General of Ireland, Chief Justice of Ireland

The chief justice of Ireland () is the president of the Supreme Court of Ireland. The chief justice is the highest judicial office and the most senior judge in the Republic of Ireland. The role includes several constitutional and administrativ ...

and President of Ireland

The president of Ireland () is the head of state of Republic of Ireland, Ireland and the supreme commander of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Irish Defence Forces. The presidency is a predominantly figurehead, ceremonial institution, serving as ...

, Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh

Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh (; 12 February 1911 – 21 March 1978) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician, judge and barrister who served as the president of Ireland from December 1974 to October 1976.

His birth name was registered in English as ' ...

.

President of Ireland

Nomination

In April 1938, by now retired from academia, Hyde was plucked from retirement byTaoiseach

The Taoiseach (, ) is the head of government or prime minister of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the President of Ireland upon nomination by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

and again appointed to Seanad Éireann

Seanad Éireann ( ; ; "Senate of Ireland") is the senate of the Oireachtas (the Irish legislature), which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann (defined as the house of representatives).

It is commonly called the Seanad or ...

. Again his tenure proved short, even shorter than before; however, this time it was because Hyde was chosen, after inter-party negotiations—following an initial suggestion by Fine Gael

Fine Gael ( ; ; ) is a centre-right, liberal-conservative, Christian democratic political party in Ireland. Fine Gael is currently the third-largest party in the Republic of Ireland in terms of members of Dáil Éireann. The party had a member ...

—to be the first President of Ireland, to which office he was elected unopposed. He was selected for a number of reasons:

*Both the Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera, and the Leader of the Opposition, W. T. Cosgrave, admired him.

*Both wanted a President with universal prestige to lend credibility to the new office, especially since the new 1937 Constitution made it unclear whether the President or the British monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British con ...

was the official head of state.

*Both wanted to purge the humiliation that had occurred when Hyde lost his Senate seat in 1925.

*Both wanted a President who would prove there was no danger that the holder of the office would become an authoritarian dictator, a widespread fear when the new constitution was being discussed in 1937.

*Both wanted to pay tribute to Hyde's role in promoting the Irish language.

*Both wanted to choose a non-Catholic to disprove the assertion that the State was a " confessional state", although on 11 May 1937 Seán MacEntee, the Fianna Fáil Minister of Finance, had described the 1937 Constitution in Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( ; , ) is the lower house and principal chamber of the Oireachtas, which also includes the president of Ireland and a senate called Seanad Éireann.Article 15.1.2° of the Constitution of Ireland reads: "The Oireachtas shall co ...

as "the Constitution of a Catholic State".

Inauguration

Hyde was inaugurated as the first President of Ireland, on 26 June 1938. ''

Hyde was inaugurated as the first President of Ireland, on 26 June 1938. ''The Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It was launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is Ireland's leading n ...

'' reported it as follows:

Hyde set a precedent by reciting the Presidential Declaration of Office in Irish. His recitation, in Roscommon Irish, is one of a few recordings of a dialect of which Hyde was one of the last speakers. Upon inauguration, he moved into the long-vacant ''Viceregal Lodge'' in Phoenix Park

The Phoenix Park () is a large urban park in Dublin, Ireland, lying west of the city centre, north of the River Liffey. Its perimeter wall encloses of recreational space. It includes large areas of grassland and tree-lined avenues, and since ...

, since known as Áras an Uachtaráin

(; "Residence of the President"), formerly the Viceregal Lodge, is the List of official residences, official residence and principal workplace of the President of Ireland.

It is located off Chesterfield Avenue in the Phoenix Park in Dublin, ...

.

Hyde's selection and inauguration received worldwide media attention and was covered by newspapers in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina, and even Egypt.Brian Murphy in the Irish Independent; 1 October 2016 ''Hyde, Hitler and why our first president fascinated press around the world'' Hitler "ordered" the Berlin newspapers "to splash" on the Irish presidential installation ceremony. However, the British government ignored the event. The Northern Ireland Finance Minister, J. M. Andrews, described Hyde's inauguration as a "slight on the King" and "a deplorable tragedy".

Presidency

Despite being placed in a position to shape the office of the presidency via precedent, Hyde by and large opted for a quiet, conservative interpretation of the office. His age and health obligated him to schedule periods of rest throughout his days, and his lack of political experience caused him to defer to his advisers on questions of policy and discretionary powers, especially to his Secretary, Michael McDunphy. On 13 November 1938, just months after Hyde's inauguration, Hyde attended an international soccer match between Ireland andPoland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

at Dalymount Park

Dalymount Park (Irish language, Irish: ''Páirc Chnocán Uí Dhálaigh'') is a Association football, football stadium in Phibsborough on the Northside Dublin, Northside of Dublin, Republic of Ireland, Ireland.

It is the home of Bohemian F.C., ...

in Dublin. This was seen as breaching the GAA's ban on 'foreign games' and he was subsequently removed as patron of the GAA, an honour he had held since 1902.

After a massive stroke in April 1940, plans were made for his lying-in-state and a state funeral. However, Hyde survived, albeit paralysed and having to use a wheelchair.

Although the role of the President of Ireland is largely ceremonial, the president has the authority under the Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland (, ) is the constitution, fundamental law of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. It guarantees certain fundamental rights, along with a popularly elected non-executi ...

to refuse to grant a dissolution of the Dáil where the Taoiseach has ceased to retain the support of a majority of the Dáil. The president is also the guardian of the constitution and may refer legislation to the Supreme Court before signing it into law.

On 31 July 1943, the Irish postal service release a set of postage stamps valued at ½ and 2½ pence bearing a portrait of Hyde to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Gaelic League

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it eme ...

.

Hyde was confronted with a crisis in 1944 when de Valera's government unexpectedly collapsed in a vote on the Transport Bill. De Valera asked Hyde for a dissolution of the Dáil. If a dissolution is granted, a general election is proclaimed to fill the seats thereby vacated. This means that for four to six weeks until the new Dáil assembled, there is no Dáil. Fearing this gap might facilitate an invasion during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, during which no parliament could be called upon to act, the Oireachtas enactethe General Elections (Emergency Powers) Act 1943

legislation under the emergency provisions of Article 28.3.3°), which allowed an election to be called separate from a dissolution, with the Dáil only being dissolved just before new Dáil would assemble. This ensured the gap between Dála (plural of Dáil) would be too short to cause a vacuum in major decision-making. Under the Act, the President could "refuse to proclaim a general election on the advice of a Taoiseach who had ceased to retain the support of a majority in Dáil Éireann". Hyde had that option but, after considering it with his senior advisor Michael McDunphy, he granted the dissolution. Hyde twice used his prerogative under Article 26 of the Constitution, having consulted the

Council of State

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

, to refer a Bill or part of a Bill to the Supreme Court, for the court's decision on whether the Bill or part referred is repugnant to the Constitution (so that the Bill in question cannot be signed into law). On the first occasion, the court held that the Bill referred – Offences Against the State (Amendment) Bill 1940 – was not repugnant to the Constitution. In response to the second reference, the Court decided that the particular provision referred to – section 4 of the School Attendance Bill 1942 – was repugnant to the Constitution. Because of Article 34.3.3° of the Constitution, the constitutional validity of the Offences Against the State (Amendment) Act, 1940 cannot be challenged in any court, since the Bill which became that Act was found by the Supreme Court not to be repugnant in the context of an Article 26 reference.

One of Hyde's last presidential acts was a visit to the German Ambassador Eduard Hempel, on 3 May 1945, to offer his formal condolences on the death of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler, chancellor and dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, committed suicide via a gunshot to the head on 30 April 1945 in the in Berlin after it became clear that Germany would lose the Battle of Berlin, which led to the e ...

. The visit remained a secret until 2005.

Retirement and death

Hyde left office on 25 June 1945, opting not to nominate himself for a second term. Owing to his ill-health he did not return to his Roscommon home, ''Ratra'', empty since the death of his wife early in his term. He moved into the former residence of the Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant, on the grounds of Áras an Uachtaráin, which he renamed '' Little Ratra'', where he lived out the remaining four years of his life. He died at 10pm on 12 July 1949, aged 89.Announcement of death, ''The Irish Times'', 13 July 1949State funeral

As a former President of Ireland, Hyde was accorded astate funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements o ...

. As he was a member of the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland (, ; , ) is a Christian church in Ireland, and an autonomy, autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the Christianity in Ireland, second-largest Christian church on the ...

, his funeral service took place in Dublin's Church of Ireland St. Patrick's Cathedral. However, contemporary rules of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland prohibited its members from attending services in non-Catholic churches. As a result, all but one member of the Catholic cabinet, Noël Browne

Noël Christopher Browne (20 December 1915 – 21 May 1997) was an Irish politician who served as Minister for Health (Ireland), Minister for Health from 1948 to 1951 and Leader of the National Progressive Democrats from 1958 to 1963. He was a ...

, remained outside the cathedral grounds while the funeral service took place. They then joined the cortège when his coffin left the cathedral. Éamon de Valera, by now Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

, also did not attend. He was represented instead by a senior Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil ( ; ; meaning "Soldiers of Destiny" or "Warriors of Fál"), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party (), is a centre to centre-right political party in Ireland.

Founded as a republican party in 1926 by Éamon de ...

figure who was a member of the Church of Ireland, Erskine H. Childers, a future President of Ireland himself. Hyde was buried in Frenchpark, County Roscommon at Portahard Church, (where he had spent most of his childhood life) beside his wife Lucy, his daughter Nuala, his sister Annette, his mother Elizabeth, and his father Arthur.

In memoriam

References

External links

Biography at Áras an Uachtaráin website

*Dunleavy, Janet Egleson and Gareth W. Dunleavy. ''Douglas Hyde: A Maker of Modern Ireland''. Berkeley et al.: Univ. of California Press, 1991

Available from eScholarship

*Hyde, Douglas. ''The Love Songs of Connacht: Being the Fourth Chapter of the Songs of Connacht''. Dundrum, Ireland: Dun Emer Press, 1904

Available from Google Books

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hyde, Douglas 1860 births 1949 deaths Academics of University College Dublin Alumni of Trinity College Dublin 19th-century Anglo-Irish people 20th-century Anglo-Irish people Celtic studies scholars Conradh na Gaeilge presidents Independent members of Seanad Éireann Irish Anglicans Irish folklorists Irish language activists Irish-language writers 19th-century Irish poets 20th-century Irish poets Members of the 1922 Seanad Members of the 2nd Seanad Nominated members of Seanad Éireann Patrons of the Gaelic Athletic Association People from Castlerea Scholars and academics from County Sligo Presidents of Ireland Scholars and academics from County Roscommon People from Frenchpark 20th-century presidents in Europe People on Irish postage stamps