Denmark–Norway on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

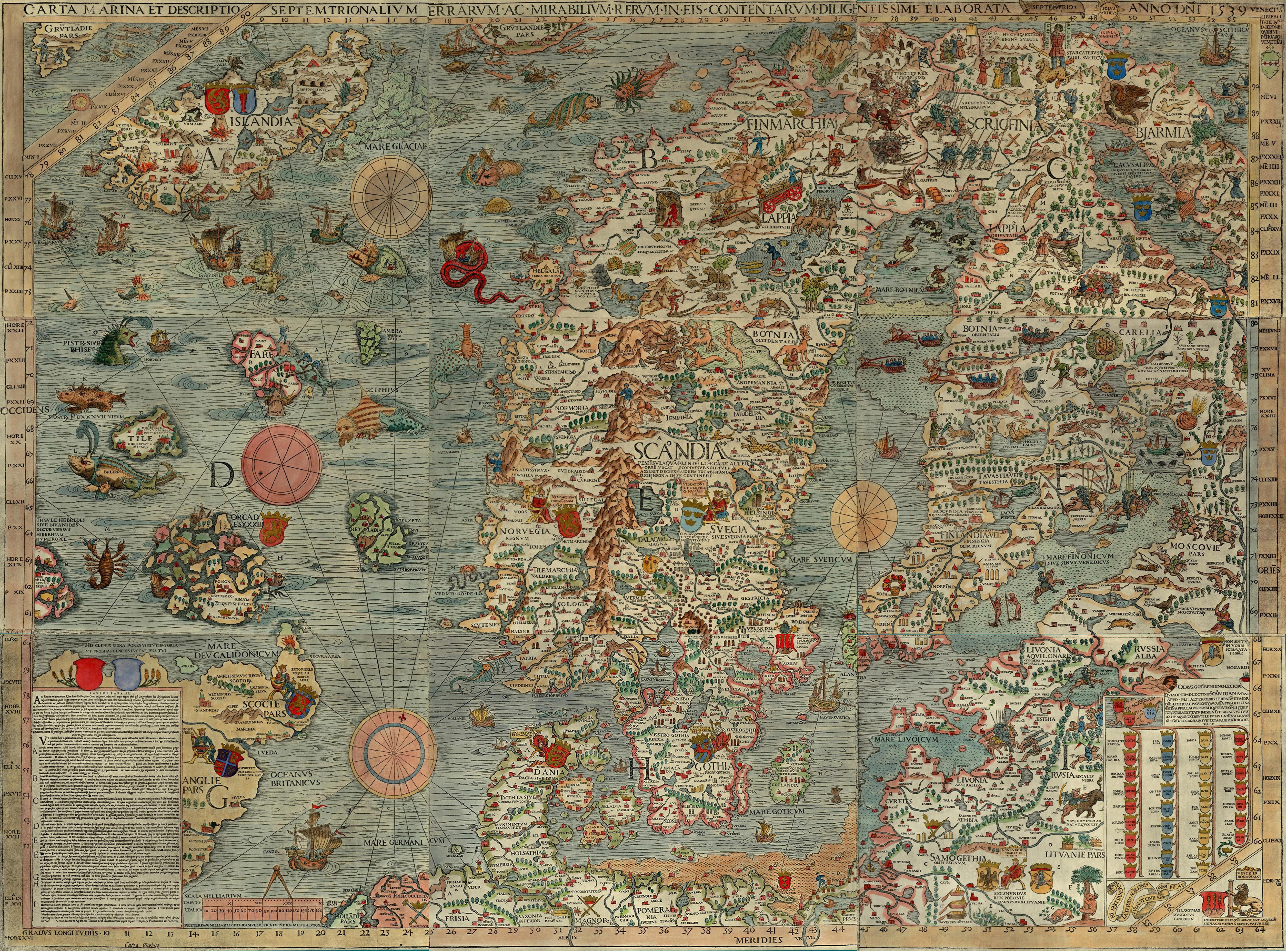

Denmark–Norway ( Danish and Norwegian: ) is a term for the 16th-to-19th-century multi-national and multi-lingual

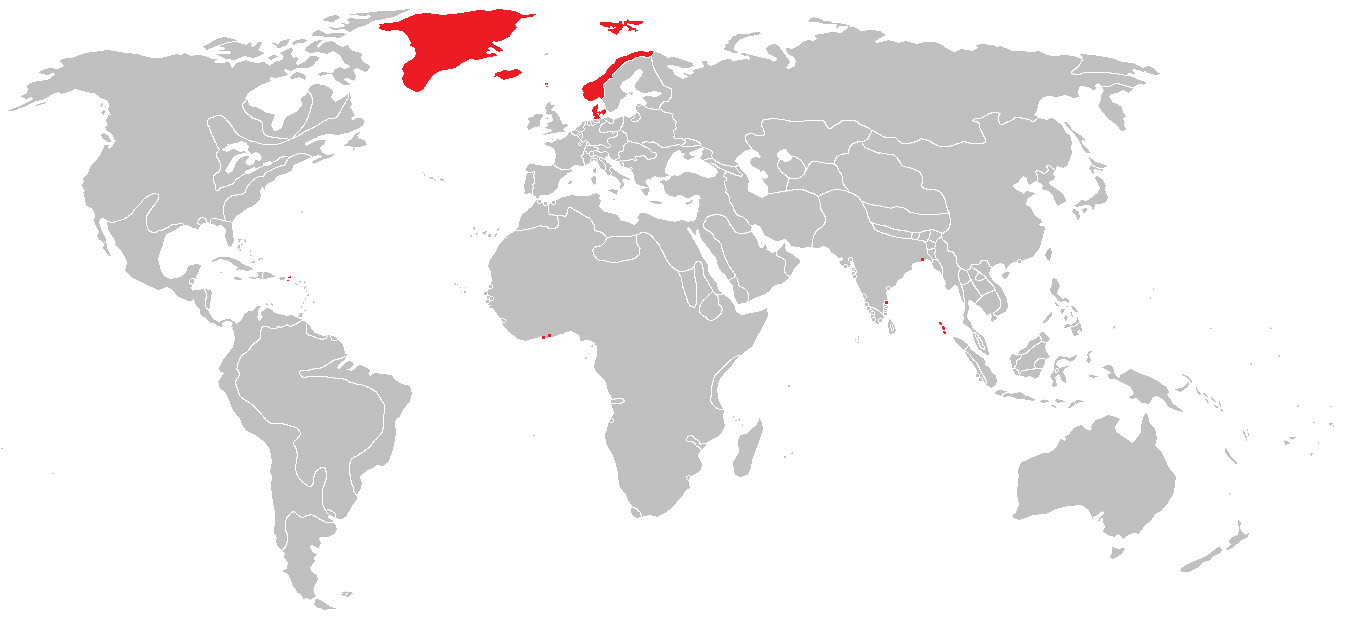

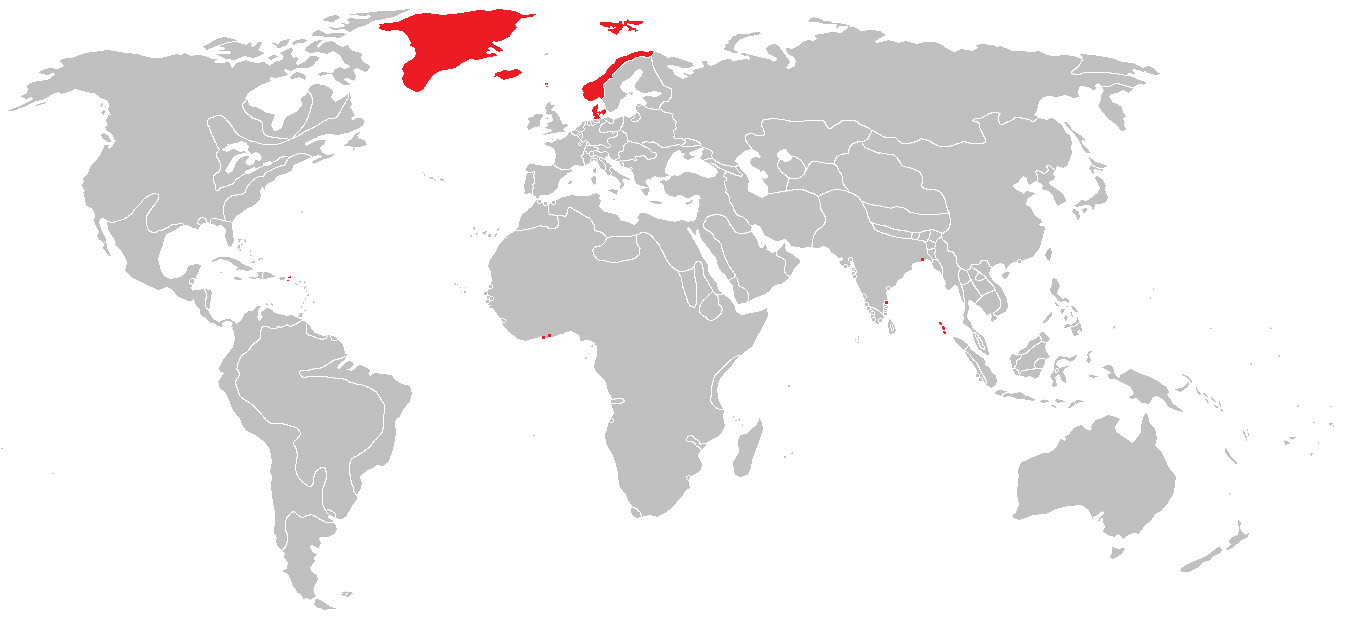

Throughout the time of Denmark–Norway, it continuously had possession over various overseas territories. At the earliest times this meant areas in

Throughout the time of Denmark–Norway, it continuously had possession over various overseas territories. At the earliest times this meant areas in

The three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden united in the

The three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden united in the

The

The

Because of Denmark–Norway's dominion over the Baltic Sea (''

Because of Denmark–Norway's dominion over the Baltic Sea (''

Sweden was very successful during the Thirty Years' War, while Denmark–Norway failed to make gains. Sweden saw an opportunity of a change of power in the region. Denmark–Norway had territory surrounding Sweden which appeared threatening, and the Sound Dues were a continuing irritation for the Swedes. In 1643 the Swedish Privy Council determined that the chances of a gain in territory for Sweden in an eventual war against Denmark–Norway would be good. Not long after this, Sweden invaded Denmark–Norway.

Denmark was poorly prepared for the war, and Norway was reluctant to attack Sweden, which left the Swedes in a good position.

The war ended as foreseen with a Swedish victory, and with the Treaty of Brömsebro in 1645, Denmark–Norway had to cede some of their territories, including Norwegian territories Jemtland, Herjedalen and Idre & Serna, and the Danish

Sweden was very successful during the Thirty Years' War, while Denmark–Norway failed to make gains. Sweden saw an opportunity of a change of power in the region. Denmark–Norway had territory surrounding Sweden which appeared threatening, and the Sound Dues were a continuing irritation for the Swedes. In 1643 the Swedish Privy Council determined that the chances of a gain in territory for Sweden in an eventual war against Denmark–Norway would be good. Not long after this, Sweden invaded Denmark–Norway.

Denmark was poorly prepared for the war, and Norway was reluctant to attack Sweden, which left the Swedes in a good position.

The war ended as foreseen with a Swedish victory, and with the Treaty of Brömsebro in 1645, Denmark–Norway had to cede some of their territories, including Norwegian territories Jemtland, Herjedalen and Idre & Serna, and the Danish

real union

Real union is a union of two or more states, which share some state institutions in contrast to personal unions; however, they are not as unified as states in a political union. It is a development from personal union and has historically been ...

Feldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, the Kingdom of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

(including the then Norwegian overseas possessions: the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

, Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

, Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, and other possessions), the Duchy of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig (; ; ; ; ; ) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been div ...

, and the Duchy of Holstein

The Duchy of Holstein (; ) was the northernmost state of the Holy Roman Empire, located in the present German state of Schleswig-Holstein. It originated when King Christian I of Denmark had his County of Holstein-Rendsburg elevated to a duchy ...

.Feldbæk 1998:21f, 125, 159ff, 281ff The state also claimed sovereignty over three historical peoples: Frisians

The Frisians () are an ethnic group indigenous to the German Bight, coastal regions of the Netherlands, north-western Germany and southern Denmark. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland an ...

, Gutes

The Gutes ( Old West Norse: ''Gotar'', Old Gutnish: ''Gutar'') were a North Germanic tribe inhabiting the island of Gotland. The ethnonym is related to that of the ''Goths'' (''Gutans''), and both names were originally Proto-Germanic *''Gutan ...

and Wends

Wends is a historical name for Slavs who inhabited present-day northeast Germany. It refers not to a homogeneous people, but to various people, tribes or groups depending on where and when it was used. In the modern day, communities identifying ...

.Feldbæk 1998:21 Denmark–Norway had several colonies, namely the Danish Gold Coast

The Danish Gold Coast ( or ''Dansk Guinea'') comprised the colonies that Denmark–Norway controlled in Africa as a part of the Gold Coast (region), Gold Coast (roughly present-day southeast Ghana), which is on the Gulf of Guinea. It was coloni ...

, Danish India

Danish India () was the name given to the forts and Factory (trading post), factories of Denmark (Denmark–Norway before 1814) in the Indian subcontinent, forming part of the Danish overseas colonies. Denmark–Norway held colonial possessions ...

(the Nicobar Islands

The Nicobar Islands are an archipelago, archipelagic island chain in the eastern Indian Ocean. They are located in Southeast Asia, northwest of Aceh on Sumatra, and separated from Thailand to the east by the Andaman Sea. Located southeast of t ...

, Serampore

Serampore (also called Serampur, Srirampur, Srirampore, Shreerampur, Shreerampore, Shrirampur or Shrirampore) is a city in Hooghly district in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is the headquarters of the Srirampore subdivision. It is a part ...

, Tharangambadi), and the Danish West Indies.Feldbæk 1998:23 The union was also known as the Dano-Norwegian Realm (''Det dansk-norske rige''), Twin Realms (''Tvillingerigerne'') or the Oldenburg Monarchy (''Oldenburg-monarkiet'').

The state's inhabitants were mainly Danes

Danes (, ), or Danish people, are an ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

History

Early history

Denmark ...

, Norwegians

Norwegians () are an ethnic group and nation native to Norway, where they form the vast majority of the population. They share a common culture and speak the Norwegian language. Norwegians are descended from the Norsemen, Norse of the Early ...

and Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

, and also included Faroese, Icelanders

Icelanders () are an ethnic group and nation who are native to the island country of Iceland. They speak Icelandic, a North Germanic language.

Icelanders established the country of Iceland in mid 930 CE when the (parliament) met for th ...

and Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

in the Norwegian overseas possessions, a Sami

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise ne ...

minority in northern Norway, as well as other indigenous peoples.Feldbæk 1998:96 The main cities of Denmark–Norway were Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

, Christiania (Oslo), Altona, Bergen

Bergen (, ) is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Vestland county on the Western Norway, west coast of Norway. Bergen is the list of towns and cities in Norway, second-largest city in Norway after the capital Oslo.

By May 20 ...

and Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; ), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros, and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2022, it had a population of 212,660. Trondheim is the third most populous municipality in Norway, and is ...

,Feldbæk 1998:66 and the primary official languages were Danish and German, but Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Sami and Greenlandic were also spoken locally.

In 1380, Olaf II of Denmark inherited the Kingdom of Norway, titled as Olaf IV, after the death of his father Haakon VI of Norway, who was married to Olaf's mother Margaret I. Margaret I was ruler of Norway from her son's death in 1387 until her own death in 1412. Denmark, Norway, and Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

established and formed the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden as designed by Queen Margaret I of Denmark, Margaret of Denmark. From 1397 to 1523, it joined under a single monarch the three kingdoms of Denmark, Sweden (then in ...

in 1397. Following Sweden's departure in 1523, the union was effectively dissolved. From 1536/1537, Denmark and Norway formed a personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

that would eventually develop into the 1660 integrated state called Denmark–Norway by modern historians, at the time sometimes referred to as the "Twin Kingdoms". Prior to 1660, Denmark–Norway was de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

a constitutional and elective monarchy

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by a monarch who is elected, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, ...

in which the King's power was somewhat limited; in that year it became one of the most stringent absolute monarchies in Europe.

The Dano-Norwegian union lasted until 1814, when the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel () or Peace of Kiel ( Swedish and or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the other side on 14 January 1814 ...

decreed that Norway (except for the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland) be ceded to Sweden. The treaty however was not recognised by Norway, which resisted the attempt in the 1814 Swedish–Norwegian War. Norway thereafter entered into a much looser personal union with Sweden until 1905, when that union was peacefully dissolved.

Usage and extent

The term "Kingdom of Denmark" is sometimes used incorrectly to include both countries in the period, since the political and economic power emanated from the Danish capital, Copenhagen. These term also cover the "royal territories" of the Oldenburgs as it was in 1460, but excluding the "ducal territories" ofSchleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig (; ; ; ; ; ) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been di ...

and Holstein

Holstein (; ; ; ; ) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider (river), Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost States of Germany, state of Germany.

Holstein once existed as the German County of Holstein (; 8 ...

. The administration used two official language

An official language is defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as, "the language or one of the languages that is accepted by a country's government, is taught in schools, used in the courts of law, etc." Depending on the decree, establishmen ...

s, Danish and German, and for several centuries both a Danish Chancellery () and German Chancellery () existed.

The term "Denmark–Norway" reflects the historical and legal roots of the union. It is adopted from the Oldenburg dynasty's official title. The kings always used the style "King of Denmark and Norway, the Wends

Wends is a historical name for Slavs who inhabited present-day northeast Germany. It refers not to a homogeneous people, but to various people, tribes or groups depending on where and when it was used. In the modern day, communities identifying ...

and the Goths

The Goths were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe. They were first reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 3rd century AD, living north of the Danube in what is ...

" ('). Denmark and Norway, sometimes referred to as the "Twin Realms" (') of Denmark–Norway, had separate legal codes and currencies, and mostly separate governing institutions. Following the introduction of absolutism in 1660, the centralisation of government meant a concentration of institutions in Copenhagen. Centralisation was supported in many parts of Norway, where the two-year attempt by Sweden to control Trøndelag

Trøndelag (; or is a county and coextensive with the Trøndelag region (also known as ''Midt-Norge'' or ''Midt-Noreg,'' "Mid-Norway") in the central part of Norway. It was created in 1687, then named Trondhjem County (); in 1804 the county was ...

had met strong local resistance and resulted in a complete failure for the Swedes and a devastation of the province. This allowed Norway to further secure itself militarily for the future through closer ties with the capital Copenhagen.

Colonies

Throughout the time of Denmark–Norway, it continuously had possession over various overseas territories. At the earliest times this meant areas in

Throughout the time of Denmark–Norway, it continuously had possession over various overseas territories. At the earliest times this meant areas in Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54th parallel north, 54°N, or may be based on other ge ...

and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

, for instance Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

and the Norwegian possessions of Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

and Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

.

From the 17th century, the kingdoms acquired colonies in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. At its height the empire was about 2,655,564.76 km2 (1,025,319 sq mi),Possessions of Denmark–Norway (as of 1800)

* Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

:

* Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

:

* Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; ; ; ; ; occasionally in English ''Sleswick-Holsatia'') is the Northern Germany, northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical Duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of S ...

:

* Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

:

* Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

:

* Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

:

* Danish India

Danish India () was the name given to the forts and Factory (trading post), factories of Denmark (Denmark–Norway before 1814) in the Indian subcontinent, forming part of the Danish overseas colonies. Denmark–Norway held colonial possessions ...

:

* Danish West Indies:

* Danish Gold Coast

The Danish Gold Coast ( or ''Dansk Guinea'') comprised the colonies that Denmark–Norway controlled in Africa as a part of the Gold Coast (region), Gold Coast (roughly present-day southeast Ghana), which is on the Gulf of Guinea. It was coloni ...

:

after the dissolution of the union, in 1814, all the overseas territories became a part of Denmark.

India

Denmark–Norway maintained numerous colonies from the 17th to 19th centuries over various parts around India. Colonies included the town of Tranquebar andSerampore

Serampore (also called Serampur, Srirampur, Srirampore, Shreerampur, Shreerampore, Shrirampur or Shrirampore) is a city in Hooghly district in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is the headquarters of the Srirampore subdivision. It is a part ...

. The last settlements Denmark had control over were sold to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

in 1845. Rights in the Nicobar Islands

The Nicobar Islands are an archipelago, archipelagic island chain in the eastern Indian Ocean. They are located in Southeast Asia, northwest of Aceh on Sumatra, and separated from Thailand to the east by the Andaman Sea. Located southeast of t ...

were sold in 1869.

Caribbean

Centred on theVirgin Islands

The Virgin Islands () are an archipelago between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and northeastern Caribbean Sea, geographically forming part of the Leeward Islands of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean, Caribbean islands or West Indie ...

, Denmark–Norway established the Danish West Indies. This colony was one of the longest-lived of Denmark, until it was sold to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in 1917. It became the U.S. Virgin Islands

The United States Virgin Islands, officially the Virgin Islands of the United States, are a group of Caribbean islands and a territory of the United States. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located ...

.

West Africa

In the Gold Coast region of West Africa, Denmark–Norway also over time had control over various colonies and forts. The last remaining forts were sold to theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

in 1850, from Denmark.

History

Origins of the Union

The three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden united in the

The three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden united in the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden as designed by Queen Margaret I of Denmark, Margaret of Denmark. From 1397 to 1523, it joined under a single monarch the three kingdoms of Denmark, Sweden (then in ...

in 1397. Sweden broke out of this union and re-entered it several times, until 1521, when Sweden finally left the Union, leaving Denmark–Norway (including overseas possessions in the North Atlantic and the island of Saaremaa in modern Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

). During the Count's Feud, where the Danish crown was contested between Protestant Oldenburg King Christian III and Catholic King Christian II, the relatively Catholic realm of Norway also wished to leave the union in the 1530s, but was unable to do so due to Denmark's superior military might. In 1537, Denmark invaded Norway, and annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

it. In doing so, Christian III removed Norway's equal status that was held during the Kalmar Union, and instead relegated Norway to a Danish puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its ord ...

in all but name.

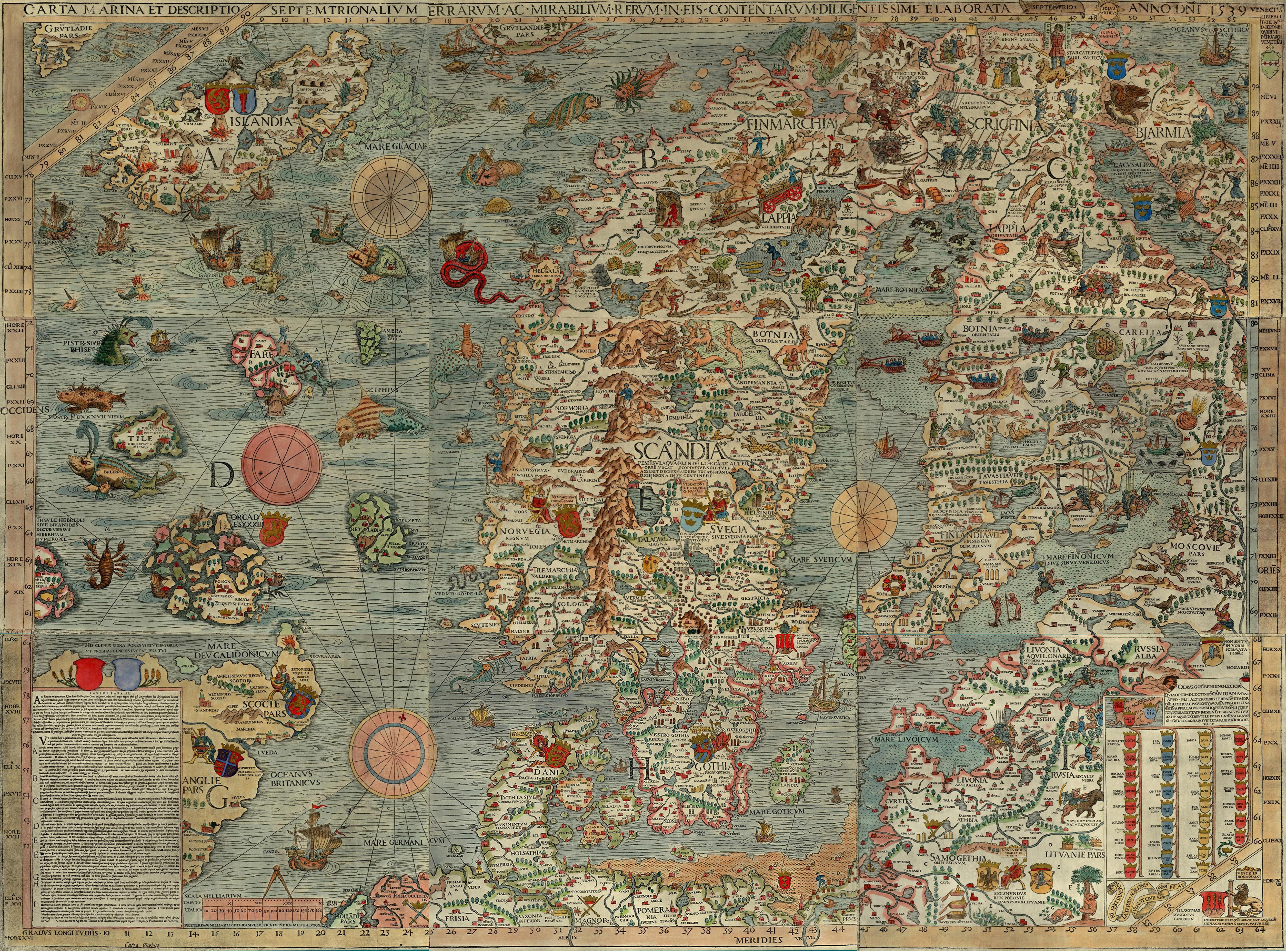

Baltic Ambitions

The

The Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

was one of the most lucrative trade spots in Europe. The German Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

used to be the dominant party in the region, but the slow collapse of the League allowed for Denmark–Norway to begin enforcing their control in the area. Denmark–Norway had a powerful navy, and with their control over the Oresund were able to enforce the Sound Tolls, a tax on passing ships. These tolls made up two thirds of Denmark-Norway’s state income, allowing kings such as Christian IV to become extremely rich.

Denmark–Norway also sought to expand into the eastern Baltic Sea. They controlled the island of Gotland

Gotland (; ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a Provinces of Sweden, province/Counties of Sweden, county (Swedish län), Municipalities of Sweden, municipality, a ...

, which was a major trading post, and using his wealth, King Frederick II purchased the island of Osel in 1560. Denmark–Norway fiercely guarded their hegemony, destroying any new competitors in the Baltic. When Poland-Lithuania attempted to build a navy in 1571, the Danish-Norwegian fleet destroyed or captured much of the Polish fleet in the Battle of Hel

The Battle of Hel (, literally "the Defense of Hel") was a World War II engagement fought from 1 September to 2 October 1939 on the Hel Peninsula, of the Baltic Sea coast, between invading German forces and defending Polish units during the Ge ...

.

Northern Seven Years' War

Christian III, who had relied on Swedish aid in the Count's Feud, kept peaceful relations with Sweden throughout his reign. However, Frederick II was quite hostile towards the Swedes. Another major factor in the war were Sweden's goals inLivonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

. Both Denmark and Sweden, along with Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, sought to control the previously Hanseatic region, as it was extremely important in controlling the Baltic Sea. When Denmark purchased Osel, Duke Magnus, brother of King Frederick II was granted control of the island. Magnus attempted to claim himself King of Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, but he was kicked out by the Russian army. The Estonians, who were fearful of the Russians, contacted King Eric XIV of Sweden for protection. Sweden then annexed Estonia, securing the region under their rule.

After Eric introduced blockades in an attempt to hinder trade with Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

(Sweden and Russia were disputing over Estonia), Lübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

joined Denmark–Norway in a war alliance. Attempts at diplomacy were made, but neither party was particularly interested in peace. When Frederick II included the traditionally Swedish insignia of three crowns into his own coat of arms, the Swedes interpreted this as a Danish claim over Sweden. In response, Erik XIV of Sweden (reigned 1560–1568) added the insignia of Norway and Denmark to his own coat of arms.

Denmark–Norway then carried out some naval attacks on Sweden, which effectively started the war. After seven years of fighting, the conflict concluded in 1570 with a ''status quo ante bellum

The term is a Latin phrase meaning 'the situation as it existed before the war'.

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When used as such, it means that no ...

''.

Kalmar War

Because of Denmark–Norway's dominion over the Baltic Sea (''

Because of Denmark–Norway's dominion over the Baltic Sea (''dominium maris baltici

The establishment of a , . ("Baltic Sea dominion") was one of the primary political aims of the Kingdom of Denmark, Danish and Kingdom of Sweden, Swedish kingdoms in the Late Middle Ages, late medieval and Early Modern era, early modern eras. Th ...

'') and the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

, Sweden had the intention of avoiding paying Denmark's Sound Toll. Swedish king Charles IX's way of accomplishing this was to try to set up a new trade route through Lapland and northern Norway. In 1607 Charles IX declared himself "King of the Lapps in Nordland", and started collecting taxes in Norwegian territory.

Denmark–Norway and King Christian IV protested against the Swedish actions, as they had no intentions of letting another independent trade route open; Christian IV also had an intent of forcing Sweden to rejoin its union with Denmark–Norway. In 1611 Denmark–Norway finally invaded Sweden with 6,000 men and took the city of Kalmar. On 20 January 1613, the Treaty of Knäred was signed, in which Norway's land route from Sweden was regained by incorporating Lapland into Norway, and Swedish payment of the Älvsborg Ransom for two fortresses which Denmark–Norway had taken in the war. However, Sweden achieved an exemption from the Sound Toll.

Aftermath of the Älvsborg Ransom

The great ransom paid by Sweden (called the Älvsborg Ransom) was used by Christian IV, among many other things, to found the cities ofGlückstadt

Glückstadt (; ) is a town in the Steinburg district of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is located on the right bank of the Lower Elbe at the confluence of the small Rhin river, about northwest of Altona. Glückstadt is part of the Hamburg ...

, Christiania (refounded after a fire), Christianshavn, Christianstad and Christianssand. He also founded the Danish East India Company

The Danish East India Company () refers to two separate Danish-Norwegian chartered company, chartered companies. The first company operated between 1616 and 1650. The second company existed between 1670 and 1729, however, in 1730 it was re-founde ...

which led to the establishment of numerous Danish colonies in India. The remainder of the money was added to Christian's already massive personal treasury.

Thirty Years' War

Not long after the Kalmar war, Denmark–Norway became involved in another greater war, in which they fought together with the mainly north German and other Protestant states against the Catholic states led by German Catholic League. The recent defeat of the Protestant League in both the Palatinate andBohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

n Campaigns, the Protestant nations of the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, and the Lower Saxon Circle

The Lower Saxon Circle () was an Imperial Circle of the Holy Roman Empire. It covered much of the territory of the medieval Duchy of Saxony (except for Westphalia), and was originally called the Saxon Circle () before later being better differen ...

, along with France, the latter of which aiming to weaken the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

, promised to fund Denmark's operations if Christian IV decided to intervene on behalf of the Protestants. With the money provided by the aforementioned states, along with his own personal fortune, Christian could hire a large army of mercenaries.

Christian IV long sought to become the leader of the north German Lutheran states. He also had interests in gaining ecclesiastical posts in Northern Germany, such as the Prince-Bishopric of Verden. However, during the Battle of Lutter

The Battle of Lutter (German language, German: ''Lutter am Barenberge'') took place on 27 August 1626 during the Thirty Years' War, south of Salzgitter, in Lower Saxony. A combined Danish-German force led by Christian IV of Denmark was defeated ...

in 1626, Denmark faced a crushing defeat. This led to most of the German Protestant states ceasing their support for Christian IV. After another defeat at the Battle of Wolgast and following the Treaty of Lübeck in 1629, which forbade Denmark–Norway from future intervening in German affairs, Denmark–Norways's participation in the war came to an end.

Torstenson War

Sweden was very successful during the Thirty Years' War, while Denmark–Norway failed to make gains. Sweden saw an opportunity of a change of power in the region. Denmark–Norway had territory surrounding Sweden which appeared threatening, and the Sound Dues were a continuing irritation for the Swedes. In 1643 the Swedish Privy Council determined that the chances of a gain in territory for Sweden in an eventual war against Denmark–Norway would be good. Not long after this, Sweden invaded Denmark–Norway.

Denmark was poorly prepared for the war, and Norway was reluctant to attack Sweden, which left the Swedes in a good position.

The war ended as foreseen with a Swedish victory, and with the Treaty of Brömsebro in 1645, Denmark–Norway had to cede some of their territories, including Norwegian territories Jemtland, Herjedalen and Idre & Serna, and the Danish

Sweden was very successful during the Thirty Years' War, while Denmark–Norway failed to make gains. Sweden saw an opportunity of a change of power in the region. Denmark–Norway had territory surrounding Sweden which appeared threatening, and the Sound Dues were a continuing irritation for the Swedes. In 1643 the Swedish Privy Council determined that the chances of a gain in territory for Sweden in an eventual war against Denmark–Norway would be good. Not long after this, Sweden invaded Denmark–Norway.

Denmark was poorly prepared for the war, and Norway was reluctant to attack Sweden, which left the Swedes in a good position.

The war ended as foreseen with a Swedish victory, and with the Treaty of Brömsebro in 1645, Denmark–Norway had to cede some of their territories, including Norwegian territories Jemtland, Herjedalen and Idre & Serna, and the Danish Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

islands of Gotland

Gotland (; ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a Provinces of Sweden, province/Counties of Sweden, county (Swedish län), Municipalities of Sweden, municipality, a ...

and Ösel. Thus the Thirty Years' War facilitated rise of Sweden as a great power, while it marked the start of decline for Denmark–Norway.

Second Northern Wars

The Dano-Swedish War (1657–1658), a part of the Second Northern War, was one of the most devastating wars for the Dano-Norwegian kingdom. After a huge loss in the war, Denmark–Norway was forced in theTreaty of Roskilde

The Treaty of Roskilde was negotiated at Høje Taastrup Church and was concluded on 26 February ( OS) or 8 March 1658 ( NS) during the Second Northern War between Frederick III of Denmark–Norway and Karl X Gustav of Sweden in the Danish ci ...

to give Sweden a quarter of its territory. This included Norwegian province of Trøndelag

Trøndelag (; or is a county and coextensive with the Trøndelag region (also known as ''Midt-Norge'' or ''Midt-Noreg,'' "Mid-Norway") in the central part of Norway. It was created in 1687, then named Trondhjem County (); in 1804 the county was ...

and Båhuslen, all remaining Danish provinces on the Swedish mainland, and the island of Bornholm

Bornholm () is a List of islands of Denmark, Danish island in the Baltic Sea, to the east of the rest of Denmark, south of Sweden, northeast of Germany and north of Poland.

Strategically located, Bornholm has been fought over for centuries. I ...

.

However, two years later, in 1660, there was a follow-up treaty, the Treaty of Copenhagen, which gave Trøndelag and Bornholm back to Denmark–Norway.

Royal absolutist state

Over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Rigsraad (''High Council'') of Denmark became weak. In 1660, it was abolished (the NorwegianRiksråd

Riksrådet (in Norwegian and Swedish) or Rigsrådet (in Danish or English: the Council of the Realm and the Council of the State – sometimes translated as the "Privy Council") is the name of the councils of the Scandinavian countries that ...

had not met since Denmark annexed Norway in 1537).

Norway kept its separate laws and some institutions, such as a royal Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

, and separate coinage and army. Norway also had its own royal standard

In heraldry and vexillology, a heraldic flag is a flag containing coat of arms, coats of arms, heraldic badges, or other devices used for personal identification.

Heraldic flags include banners, standards, pennons and their variants, gonfalons, ...

flag until 1748, after that the Dannebrog became the only official merchant flag in the union. Denmark–Norway became an absolutist state and Denmark a hereditary monarchy

A hereditary monarchy is a form of government and succession of power in which the throne passes from one member of a ruling family to another member of the same family. A series of rulers from the same family would constitute a dynasty. It is ...

, as Norway ''de jure'' had been since 1537. These changes were confirmed in the '' Leges regiae'' signed on 14 November 1665, stipulating that all power lay in the hands of the king, who was only responsible to God.

In Denmark, the kings also began stripping rights from the Danish nobility. The Danish and Norwegian nobility saw a population decline during the 1500s, which allowed the Crown to seize more land for itself. The growing wealth of the Danish-Norwegian kings due to the Oresund allowed them fight wars without consent from the nobility and Danish Rigsraad, meaning that Danish-Norwegian kings slowly gained more and more absolute authority over time.

Scanian War

Denmark had lost its provinces in Scania after the Treaty of Roskilde and was always eager to retrieve them, but as Sweden had grown into a great power it would not be an easy task. However, Christian V saw an opportunity when Sweden got involved in theFranco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, 1672 to 1678, was primarily fought by Kingdom of France, France and the Dutch Republic, with both sides backed at different times by a variety of allies. Related conflicts include the 1672 to 1674 Third Anglo-Dutch War and ...

, and after some hesitation Denmark–Norway invaded Sweden in 1675.

Although the Danish-Norwegian assault began as a great success, the Swedes led by 19-year-old Charles XI counter-attacked and took back the land that was being occupied. The war was concluded with the French dictating peace, with no permanent gains or losses to either of the countries.

French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

During theFrench Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

, Denmark–Norway initially attempted to remain neutral and continue to trade with both France and Britain, though when it entered the Second League of Armed Neutrality the British considered this to be a hostile action and defeated a Danish fleet off Copenhagen in 1801. Six years later during the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, the British sent an expedition which besieged and occupied Copenhagen. Britain also captured most of the Dano-Norwegian navy, incorporating most of their prizes into the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and destroying the rest. The Dano-Norwegian navy was caught unprepared for any military operation and the British found their ships still in dock after the winter season. The Dano-Norwegians were more concerned about preserving their continued neutrality and the entire Dano-Norwegian army was therefore gathered at Danevirke

The Danevirke or Danework (modern Danish language, Danish spelling: ''Dannevirke''; in Old Norse language, Old Norse: ''Danavirki'', in German language, German: ''Danewerk'', literally meaning ''Earthworks (archaeology), earthwork of the Danes'') ...

in the event of a French attack, leaving much of Denmark undefended. The British attack led the Dano-Norwegians into an alliance with France, although without a fleet they could do little.

Denmark–Norway was defeated and had to cede the Kingdom of Norway to the King of Sweden at the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel () or Peace of Kiel ( Swedish and or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the other side on 14 January 1814 ...

. Norway's overseas possessions were kept by Denmark. But the Norwegians objected to the terms of this treaty, and a constitutional assembly declared Norwegian independence on 17 May 1814 and elected the Crown Prince Christian Frederik as king of independent Norway. Following a Swedish invasion, Norway was forced to accept a personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

between Sweden and Norway, but retained its liberal constitution and separate institutions, except for the foreign service. The union was dissolved in 1905.

Culture

Differences between Denmark and Norway

After 1660, Denmark–Norway consisted of five formally separate parts (the Kingdom ofDenmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, the Kingdom of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, the Duchy of Holstein

The Duchy of Holstein (; ) was the northernmost state of the Holy Roman Empire, located in the present German state of Schleswig-Holstein. It originated when King Christian I of Denmark had his County of Holstein-Rendsburg elevated to a duchy ...

, the Duchy of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig (; ; ; ; ; ) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been div ...

and the County of Oldenburg

The County of Oldenburg () was a county of the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1448 Christian I of Denmark (of the House of Oldenburg), Count of Oldenburg became King of Denmark, and later King of Norway and King of Sweden. One of his grandsons, Adolf, ...

). Norway had its separate laws and some institutions, and separate coinage and army. Culturally and politically Denmark became dominant. While Denmark remained a largely agricultural society, Norway was industrialized from the 16th century and had a highly export-driven economy; Norway's shipping, timber and mining industries made Norway "the developed and industrialized part of Denmark-Norway" and an economic equal of Denmark.

Denmark and Norway complemented each other and had a significant internal trade, with Norway relying on Danish agricultural products and Denmark relying on Norway's timber and metals. Norway was also the more egalitarian part of the twin kingdoms; in Norway the King (i.e. the state) owned much of the land, while Denmark was dominated by large noble landowners. Denmark had a serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

-like institution known as ''Stavnsbånd

The Stavnsbånd was a serfdom-like institution introduced in Denmark in 1733 in accordance with the wishes of estate (land), estate owners and the military. It bonded men between the ages of 14 and 36 to live on the estate where they were born. It ...

'' which restricted men to the estates they were born on; all farmers in Norway on the other hand were free, could settle anywhere and were on average more affluent than Danish farmers. For many Danish people who had the possibility to leave Denmark proper, such as merchants and civil servants, Norway was seen as an attractive country of opportunities. The same was the case for the Norwegians, and many Norwegians migrated to Denmark, like the famous author Ludvig Holberg

Ludvig Holberg, Baron of Holberg (3 December 1684 – 28 January 1754) was a writer, essayist, philosopher, historian and playwright born in Bergen, Norway, during the time of the Denmark–Norway, Dano–Norwegian dual monarchy. He was infl ...

.

Languages

* Danish – officially recognized, dominant language, used by most of the unions nobility, was also church language in Denmark, Norway, Greenland, the Faroe Islands and parts of Schleswig. *High German

The High German languages (, i.e. ''High German dialects''), or simply High German ( ) – not to be confused with Standard High German which is commonly also called "High German" – comprise the varieties of German spoken south of the Ben ...

– officially recognized, used by a minority of the nobility, and church language in Holstein and parts of Schleswig.

* Low German

Low German is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language variety, language spoken mainly in Northern Germany and the northeastern Netherlands. The dialect of Plautdietsch is also spoken in the Russian Mennonite diaspora worldwide. "Low" ...

– not officially recognized, the main spoken language in Holstein and parts of Schleswig. Spoken to some degree mostly by Hanseatic traders In Bergen.

* Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

– commonly used in foreign relations, and popular as a second language among some of the nobility.

* Norwegian – not officially recognized, mostly used as a spoken language in Norway.

* Icelandic – recognized as a church language in Iceland after the Reformation, used as a spoken and written language in Iceland.

* Faroese – not officially recognized, mostly used as a spoken language on the Faroe Islands.

* Sámi languages

The Sámi languages ( ), also rendered in English language, English as Sami and Saami, are a group of Uralic languages spoken by the Indigenous Sámi peoples in Northern Europe (in parts of northern Finland, Norway, Sweden, and extreme northwest ...

– not officially recognized, spoken by Sami people in Norway.

* Greenlandic – not officially recognized, spoken by Greenlandic Inuit

The Greenlandic Inuit or sometimes simply the Greenlandic are an ethnic group and nation Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous to Greenland, where they constitute the largest ethnic population. They share a common #History, ancestry, ...

.

* North Frisian – not officially recognized, mostly used as a spoken language in some parts of Schleswig.

Religion

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

had been a religious movement in Denmark ever since the reign of Christian II. Though the country remained Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

during the reign of Frederick I, and in Norway it was not a big movement at that time. But the victory in the Count's Feud secured Denmark under the Protestant King Christian III, and in 1537 he also secured Norway, creating the union between the two kingdoms.

In the following years, Denmark–Norway was among the countries to follow Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

after the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

, and thus established Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

Protestantism as official religion in place of Roman Catholicism. Lutheran Protestantism prevailed through the union's life span. The Church of Denmark

The Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Denmark or National Church ( , or unofficially ; ), sometimes called the Church of Denmark, is the established, state-supported church in Denmark. The supreme secular authority of the church is composed of ...

and the Church of Norway

The Church of Norway (, , , ) is an Lutheranism, evangelical Lutheran denomination of Protestant Christianity and by far the largest Christian church in Norway. Christianity became the state religion of Norway around 1020, and was established a ...

was founded during this time as well. The introduction of Lutheranism in Denmark-Norway was also a political move. Due to the creation of state churches, the king had the authority to seize church properties, levy his own church tithes, and stop paying taxes to the Papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

. This helped in Denmark-Norway's absolutism and increased the wealth of its kings.

There was one other religious "reformation" in the kingdoms during the rule of Christian VI, a follower of Pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life.

Although the movement is ali ...

. The period from 1735 until his death in 1746 has been nicknamed "the State Pietism", as new laws and regulations were established in favor of Pietism. Though Pietism did not last for a substantial time, numerous new small pietistic resurrections occurred over the next 200 years. In the end, Pietism was never firmly established as a lasting religious grouping, but policies enacted by the "pietist king" affects citizens of Denmark, Norway and Iceland to this day, like the Holiday Peace Act.

Legacy

Although the Dano–Norwegian union was generally viewed favourably in Denmark and Norway at the time of its dissolution in 1814, some 19th-century Norwegian writers disparaged the union as a "400-year night". Some modern historians describe the idea of a "400-year night" as a myth that was created as a rhetorical device in the struggle against the Swedish–Norwegian union, inspired by 19th-century national-romanticist ideas. Since the late 19th century the Danish–Norwegian union was increasingly viewed in a more nuanced and favourable light in Norway with a stronger focus on empirical research, and historians have highlighted that the Norwegian economy thrived and that Norway was one of the world's wealthiest countries during the entire period of union with Denmark. Historians have also pointed out that Norway was a separate state, with its own army, legal system and other institutions, with significant autonomy in its internal affairs, and that it was primarily governed by a local elite of civil servants who identified as Norwegian, albeit in the name of the "Danish" King. Norwegians were also well represented in the military, civil service and business elites of Denmark–Norway, and in the administration of the colonies in the Caribbean and elsewhere. Norway benefited militarily from the combined strength of Denmark–Norway in the wars with Sweden and economically from its trade relationship with Denmark in which Norwegian industry enjoyed a legal monopoly in Denmark while Denmark supplied Norway with agricultural products.See also

*Kingdom of Norway (1814)

In 1814, the Kingdom of Norway made a brief and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to regain its independence. While Norway had always legally been a separate kingdom, since the 16th century it had shared a monarch with Denmark; Norway was a subo ...

* Military history of Denmark

* Military history of Norway

* Possessions of Norway

* Union between Sweden and Norway

Sweden and Norway or Sweden–Norway (; ), officially the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, and known as the United Kingdoms, was a personal union of the separate kingdoms of Sweden and Norway under a common monarch and common foreign pol ...

* Dano-Norwegian

Dano-Norwegian (Danish language, Danish and ) was a Koine language, koiné/mixed language that evolved among the urban elite in Norwegian cities during the later years of the union between the Denmark–Norway, Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway (1 ...

language

Notes

Notelist

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Denmark-Norway Denmark–Norway relations Monarchy of Denmark Monarchy of Norway 1536 establishments in Europe 1537 establishments in Europe 1660 establishments in Europe 16th century in Denmark 16th century in Norway 17th century in Denmark 17th century in Norway 18th century in Denmark 18th century in Norway 19th century in Denmark 19th century in Norway States and territories disestablished in 1814 Personal unions Real unions Former monarchies Former state unions Former monarchies of Europe