Dartmouth, Massachusetts on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dartmouth (

Massachusett

The Massachusett are a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for "At the Great Hill," referring to the Blue Hills ...

: ) is a coastal town in Bristol County, Massachusetts

Bristol County is a county in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 579,200. The shire town is Taunton. Some governmental functions are performed by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, othe ...

, United States. Old Dartmouth was the first area of Southeastern Massachusetts to be settled by Europeans in 1652, primarily English. Dartmouth is part of New England's farm coast, which consists of a chain of historic coastal villages, vineyards, and farms. June 8, 2014, marked the 350th year of Dartmouth's incorporation as a town. It is also part of the Massachusetts South Coast.

The northern part of Dartmouth hosts the town's large commercial districts. The southern part of town abuts Buzzards Bay

Buzzards Bay is a bay of the Atlantic Ocean adjacent to the U.S. state of Massachusetts. It is approximately 28 miles (45 kilometers) long by 8 miles (12 kilometers) wide. It is a popular destination for fishing, boating, and tourism. Buzzards ...

, and there are several other waterways, including Lake Noquochoke, Cornell Pond, Slocums River, Shingle Island River and Paskamansett River. The town has several working farms and one vineyard, which is part of the Coastal Wine Tour. With a thriving agricultural heritage, the town and state have protected many of the working farms.

The southern part of Dartmouth borders Buzzards Bay

Buzzards Bay is a bay of the Atlantic Ocean adjacent to the U.S. state of Massachusetts. It is approximately 28 miles (45 kilometers) long by 8 miles (12 kilometers) wide. It is a popular destination for fishing, boating, and tourism. Buzzards ...

, where a lively fishing and boating community thrives; off its coast, the Elizabeth Islands

The Elizabeth Islands are a chain of over 20 small islands extending southwest from the southern coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts in the United States. They are located at the outer edge of Buzzards Bay, north of Martha's Vineyard, from whic ...

and Cuttyhunk can be seen. The New Bedford Yacht Club in Padanaram hosts a bi-annual regatta. It has been a destination for generations as a summer community. Notable affluent sections within South Dartmouth are Nonquitt, Round Hill, Barney's Joy, and Mishaum Point. As of the 2020 census, the year-round population of Dartmouth was 33,783.

Dartmouth is the third-largest town (by land area) in Massachusetts, after Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

and Middleborough. The distance from Dartmouth's northernmost border with Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

to Buzzards Bay

Buzzards Bay is a bay of the Atlantic Ocean adjacent to the U.S. state of Massachusetts. It is approximately 28 miles (45 kilometers) long by 8 miles (12 kilometers) wide. It is a popular destination for fishing, boating, and tourism. Buzzards ...

in the south is approximately . The villages of Hixville, Bliss Corner, Padanaram, Smith Mills, and Russells Mills are located within the town. Dartmouth shares borders with Westport to the west, Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

and Fall River to the north, Buzzards Bay

Buzzards Bay is a bay of the Atlantic Ocean adjacent to the U.S. state of Massachusetts. It is approximately 28 miles (45 kilometers) long by 8 miles (12 kilometers) wide. It is a popular destination for fishing, boating, and tourism. Buzzards ...

to the south, and New Bedford

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast (Massachusetts), South Coast region. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, New Bedford had a ...

to the east. Boat shuttles provide regular transportation daily to Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the U.S. state of Massachusetts, lying just south of Cape Cod. It is known for being a popular, affluent summer colony, and includes the smaller peninsula Chappaquiddick Isla ...

and Cuttyhunk Island.

The local weekly newspapers are ''The Dartmouth/Westport Chronicle and Dartmouth Week.'' The Portuguese municipality of Lagoa is twinned with the town; along with several other Massachusetts and Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

towns and cities around Bristol County.

Etymology

The origin of the name is considered to be named after Dartmouth, England. This could have been because Bartholomew Gosnold, the first European to explore the land, sailed to America on a ship from Dartmouth in England. It could have been also named Dartmouth to commemorate when the Pilgrims stopped in Dartmouth for ship repairs.History

Early colonial history

Before the 17th century, the lands that now constitute Dartmouth had been inhabited by theWampanoag

The Wampanoag, also rendered Wôpanâak, are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Northeastern Woodlands currently based in southeastern Massachusetts and forme ...

Native Americans, who were part of the Algonquian language family and had settlements throughout southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, including Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the U.S. state of Massachusetts, lying just south of Cape Cod. It is known for being a popular, affluent summer colony, and includes the smaller peninsula Chappaquiddick Isla ...

and Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck Island, Tuckernuck and Muskeget Island, Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and Co ...

. Their population is believed to have been about 12,000.

The Wampanoag

The Wampanoag, also rendered Wôpanâak, are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Northeastern Woodlands currently based in southeastern Massachusetts and forme ...

inhabited the area for up to a thousand years before European colonization, and their ancestors had been there longer. In John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1588 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and a leading figure in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the fir ...

's (1587–1649) journal, he wrote the name of Dartmouth's indigenous tribes as being the Nukkehkammes. The English explorer Bartholomew Gosnold in the ship ''Concord'' landed on Cuttyhunk Island on May 15, 1602, and explored the area before leaving and eventually settling in the Jamestown Colony

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James River, about southwest of present-day Williamsburg. It was established by the L ...

of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. Gosnolds explorations of the area took him to Round Hill, which he named Hap's Hill. Additionally he described the territories of Dartmouth as being covered in fields with flowers, beech

Beech (genus ''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to subtropical (accessory forest element) and temperate (as dominant element of Mesophyte, mesophytic forests) Eurasia and North America. There are 14 accepted ...

and cedar groves. He picked wild strawberries, and noticed deer. He also saw the Apponagansett River which runs through Padanaram Harbor, and the Acushnet River.

Settled sparsely by the natives, with the arrival of the pilgrims in Plymouth, the region gradually began to become of interest to the colonists, until a meeting was held to officially purchase the land.

Old Dartmouth

On March 7, 1652, English colonists met with the native tribe and purchased Old Dartmouth—a region of that now contains the modern cities and towns of Dartmouth, Acushnet,New Bedford

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast (Massachusetts), South Coast region. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, New Bedford had a ...

, Fairhaven, and Westport—in a treaty between the Wampanoag—represented by Chief Ousamequin (Massasoit

Massasoit Sachem ( ) or Ousamequin (1661)"Native People" (page), "Massasoit (Ousamequin) Sachem" (section),''MayflowerFamilies.com'', web pag was the sachem or leader of the Wampanoag confederacy. ''Massasoit'' means ''Great Sachem''. Although ...

) and his son Wamsutta—and high-ranking "Purchasers" and "Old Comers" from Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes spelled Plimouth) was the first permanent English colony in New England from 1620 and the third permanent English colony in America, after Newfoundland and the Jamestown Colony. It was settled by the passengers on t ...

: John Winslow, William Bradford, Myles Standish

Myles Standish ( – October 3, 1656) was an English military officer and colonist. He was hired as military adviser for Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts, United States by the Pilgrims (Plymouth Colony), Pilgrims. Standish accompan ...

, Thomas Southworth, and John Cooke. John Cooke had come to America as a passenger on the Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English sailing ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, reac ...

, a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

Minister, he was forced to leave Plymouth due to religious views that differed from the rest of the Plymouth Colony. He would settle in Old Dartmouth.

30 yards of cloth, eight moose skins, fifteen axes, fifteen hoes, fifteen pair of breeches, eight blankets, two kettles, one cloak, £2 in wampum, eight pair of stockings, eight pair shoes, one iron pot and 10 shillings in another commoditie icWhile the Europeans considered themselves full owners of the land through the transaction, the Wampanoag have disputed this claim because the concept of exclusive land ownership—in contrast with hunting, fishing, and farming rights—was a foreign concept to them. According to the European interpretation of the deed, in one year, all Natives previously living on the land would have to leave. This led to a lengthy land dispute as the deed did not define boundary lines, and merely referred to the ceded land as, "that land called Dartmouth" and the younger son of

Massasoit

Massasoit Sachem ( ) or Ousamequin (1661)"Native People" (page), "Massasoit (Ousamequin) Sachem" (section),''MayflowerFamilies.com'', web pag was the sachem or leader of the Wampanoag confederacy. ''Massasoit'' means ''Great Sachem''. Although ...

, Metacomet

Metacomet (c. 1638 in Massachusetts – August 12, 1676), also known as Pometacom, Metacom, and by his adopted English name King Philip,Metacomet

Metacomet (c. 1638 in Massachusetts – August 12, 1676), also known as Pometacom, Metacom, and by his adopted English name King Philip, While the Europeans considered themselves full owners of the land through the transaction, the Wampanoag disputed this claim because the concept of land ownership—in contrast with hunting, fishing, and farming rights—was a foreign concept to them.

The town was purchased by 34 people from the Plymouth Colony, but most of the purchasers never lived in Dartmouth. Only ten families came to reside in Dartmouth. Those ten families were the Cooks, Delanos, Francis', Hicks', Howlands, Jennys, Kemptons, Mortons, Samsons, and Soules.

Members of the

Members of the

The rising European population and increasing demand for land led the colonists' relationship with the indigenous inhabitants of New England to deteriorate. European encroachment and disregard for the terms of the Old Dartmouth Purchase led to

The rising European population and increasing demand for land led the colonists' relationship with the indigenous inhabitants of New England to deteriorate. European encroachment and disregard for the terms of the Old Dartmouth Purchase led to

In the years before the

In the years before the

''Old'' Dartmouth, as well as writing about his maladies while serving in the South, and morale among the troops, before sending his regards to his family in Dartmouth. Nahum Nickelson was another resident of Dartmouth who served in the Civil War. He enlisted in the 35th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment as a drummer in March 1864. He trained for five weeks in Boston Harbor before taking a transport ship to

The Watuppa Branch railroad started to serve Dartmouth in 1875.

During the late 19th century its coastline became a summer resort area for wealthy members of New England society.

The Watuppa Branch railroad started to serve Dartmouth in 1875.

During the late 19th century its coastline became a summer resort area for wealthy members of New England society.

" Bristol County Sheriff's Office. Retrieved on January 30, 2012. "400 Faunce Corner Road, Dartmouth, MA 0274" and "Bristol County House Of Correction and Jail 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747" and "Bristol County Sheriff's Office Women's Center 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747" and "C. Carlos Carreiro Immigration Detention Center: 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747"

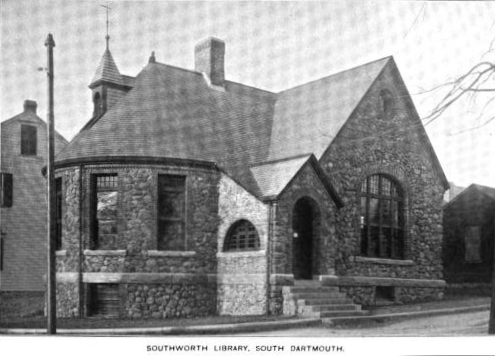

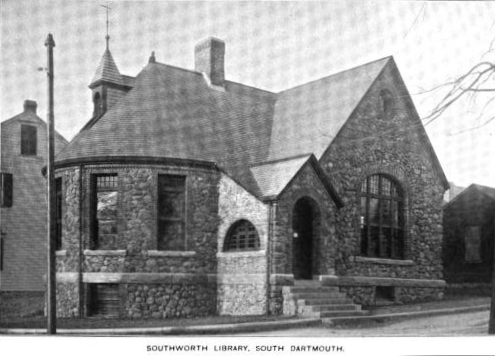

Dartmouth established public library services in 1895. Today there are two libraries, the Southworth (Main) Library in South Dartmouth, and the Dartmouth Public Library—North Branch. The Southworth Library is part of the Sails Library Network, and shares a name with an older library. The older library, also called Southworth, was founded in 1878, by the pastor of the Congregational Church of South Dartmouth. The location of the Old Southworth library was purchased in 1888, and dedicated in 1890, due to funds from John Haywood Southworth—who furnished the library with 2,500 books in memory of his father. At the time the library required the purchase of a 50 cent library card to borrow books. The library was acquired by the town of Dartmouth in 1927. The building lacked space to contain books by 1958, and in April 1967 it was voted upon to build a new library with $515,000 on Dartmouth Street. In fiscal year 2008, the town of Dartmouth spent 1.5% ($865,864) of its budget on its public libraries—approximately $25 per person. Additionally, the Dartmouth Free Public library existed in Russells Mills, moving to various locations throughout the area—catering mostly to children at the local schools there.

Dartmouth established public library services in 1895. Today there are two libraries, the Southworth (Main) Library in South Dartmouth, and the Dartmouth Public Library—North Branch. The Southworth Library is part of the Sails Library Network, and shares a name with an older library. The older library, also called Southworth, was founded in 1878, by the pastor of the Congregational Church of South Dartmouth. The location of the Old Southworth library was purchased in 1888, and dedicated in 1890, due to funds from John Haywood Southworth—who furnished the library with 2,500 books in memory of his father. At the time the library required the purchase of a 50 cent library card to borrow books. The library was acquired by the town of Dartmouth in 1927. The building lacked space to contain books by 1958, and in April 1967 it was voted upon to build a new library with $515,000 on Dartmouth Street. In fiscal year 2008, the town of Dartmouth spent 1.5% ($865,864) of its budget on its public libraries—approximately $25 per person. Additionally, the Dartmouth Free Public library existed in Russells Mills, moving to various locations throughout the area—catering mostly to children at the local schools there.

Dartmouth is governed by a single school department whose headquarters are in the former Bush Street School in Padanaram. The school department has been experiencing many changes in the past decade, with the opening of a new high school, and the moving of the former Middle School to the High School. The town currently has four elementary schools, Joseph P. DeMello, George H. Potter, James M. Quinn, and Andrew B. Cushman. The town has one middle school (located in the 1955-vintage High School building) next to the Town Hall, and one high school, the new Dartmouth High School, which opened in 2002 in the southern part of town. Its colors are Dartmouth green and white, and its fight song is "Glory to Dartmouth;" unlike the college, however, the school still uses the "Indians" nickname, with a stylized brave's head in profile as the logo which represents the Eastern Woodland Natives that first inhabited the area.

In addition to DHS, students may also attend Greater New Bedford Regional Vocational-Technical High School or Bristol County Agricultural High School. The town is also home to private schools including Bishop Stang, and Friends Academy.

Since the 1960s, Dartmouth has been home to the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth campus, located on Old Westport Road, just southwest of the Smith Mills section of town. The campus was the result of the unification of the Bradford Durfee College of Technology in Fall River and the New Bedford Institute of Textiles and Technology in New Bedford in 1962 to form the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute. The campus itself was begun in 1964 and its unique

Dartmouth is governed by a single school department whose headquarters are in the former Bush Street School in Padanaram. The school department has been experiencing many changes in the past decade, with the opening of a new high school, and the moving of the former Middle School to the High School. The town currently has four elementary schools, Joseph P. DeMello, George H. Potter, James M. Quinn, and Andrew B. Cushman. The town has one middle school (located in the 1955-vintage High School building) next to the Town Hall, and one high school, the new Dartmouth High School, which opened in 2002 in the southern part of town. Its colors are Dartmouth green and white, and its fight song is "Glory to Dartmouth;" unlike the college, however, the school still uses the "Indians" nickname, with a stylized brave's head in profile as the logo which represents the Eastern Woodland Natives that first inhabited the area.

In addition to DHS, students may also attend Greater New Bedford Regional Vocational-Technical High School or Bristol County Agricultural High School. The town is also home to private schools including Bishop Stang, and Friends Academy.

Since the 1960s, Dartmouth has been home to the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth campus, located on Old Westport Road, just southwest of the Smith Mills section of town. The campus was the result of the unification of the Bradford Durfee College of Technology in Fall River and the New Bedford Institute of Textiles and Technology in New Bedford in 1962 to form the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute. The campus itself was begun in 1964 and its unique

Town of Dartmouth official website

{{Authority control 1650 establishments in Plymouth Colony Populated coastal places in Massachusetts Populated places established in 1650 Providence metropolitan area Towns in Bristol County, Massachusetts Towns in Massachusetts

Quakers

Members of the

Members of the Religious Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

, also known as Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

, were among the early European settlers on the South Coast. They had faced persecution in the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

communities of Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes spelled Plimouth) was the first permanent English colony in New England from 1620 and the third permanent English colony in America, after Newfoundland and the Jamestown Colony. It was settled by the passengers on t ...

and Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

; the latter banned the Quakers in 1656–1657. When the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

annexed the Plymouth Colony in 1691, Quakers already represented a majority of the population of Old Dartmouth. In 1699, with the support of Peleg Slocum, the Quakers built their first meeting house

A meeting house (also spelled meetinghouse or meeting-house) is a building where religious and sometimes private meetings take place.

Terminology

Nonconformist (Protestantism), Nonconformist Protestant denominations distinguish between a:

* chu ...

in Old Dartmouth, where the Apponegansett Meeting House is now located.

At first, the Old Dartmouth territory was devoid of major town centers, and instead had isolated farms and small, decentralized villages, such as Russells' Mills. One reason for this is that the inhabitants enjoyed their independence from the Plymouth Colony and they did not want to have a large enough population for the Plymouth court to appoint them a minister. There are still Quaker meeting houses in Dartmouth, including the Smith Neck Meeting House, the Allens Neck Meeting House, and the Apponegansett Meeting House, which is on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

.

King Philip's War

The rising European population and increasing demand for land led the colonists' relationship with the indigenous inhabitants of New England to deteriorate. European encroachment and disregard for the terms of the Old Dartmouth Purchase led to

The rising European population and increasing demand for land led the colonists' relationship with the indigenous inhabitants of New England to deteriorate. European encroachment and disregard for the terms of the Old Dartmouth Purchase led to King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1678 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodland ...

in 1675. In this conflict, Wampanoag

The Wampanoag, also rendered Wôpanâak, are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Northeastern Woodlands currently based in southeastern Massachusetts and forme ...

tribesmen, allied with the Narragansett and the Nipmuc

The Nipmuc or Nipmuck people are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who historically spoke an Eastern Algonquian languages, Eastern Algonquian language, probably the Loup language. Their historic territory Nippenet, meaning 'the f ...

, raided Old Dartmouth and other European settlements in the area. Europeans in Old Dartmouth garrisoned in sturdier homes—John Russell's garrison in Padanaram, John Cooke's home in Fairhaven, and a third garrison on Palmer Island.

Revolutionary War

One of the minutemen signalled byPaul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, military officer and industrialist who played a major role during the opening months of the American Revolutionary War in Massachusetts, ...

spread the alarm of the approaching British forces into Dartmouth, after moving through Acushnet, Fairhaven, and Bedford Village. Three companies of Dartmouth Minutemen

Minutemen were members of the organized New England colonial militia companies trained in weaponry, tactics, and military strategies during the American Revolutionary War. They were known for being ready at a minute's notice, hence the name. Min ...

were marched out of the town on April 21, 1775, by Captain Thomas Kempton to a military camp in Roxbury, joining 20,000 other soldiers. Prior to the war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

Kempton had been a whaler in New Bedford

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast (Massachusetts), South Coast region. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, New Bedford had a ...

. The additional two Dartmouth companies were led by Captain's Dillingham and Egery. The last Dartmouth town meeting called in the name of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

occurred in February 1776. Also in 1776, and again in 1779, Dartmouth voters where called upon to sit on the Committee of Correspondence, Safety and Inspection, with the job of looking for individuals performing treasonous acts—and to report them to the War Council. Dartmouth had two companies of soldiers in the 18th Regiment of the Bunker Hill Army. No Dartmouth troops were ever again ordered north following March 17, 1776.

In 1778 the village of Padanaram was raided by British troops as part of Grey's raid. The village was then known as Akin's Landing, and following Elihu Akin driving three Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

out of the village in September 1778, British raiding parties burned down most of the village, focusing on Akin's properties. The raiders targeted Akin specifically because he had expelled the Loyalists from Dartmouth. They forced Akin to move to his only remaining property, a small home on Potters Hill—the Elihu Akin house. Elihu never financially recovered from the attack and died poor, he lived at the house until he died in 1794. Fixing the damage to the town from the raid cost £105,960 in 1778. Which is roughly equivalent to nine million dollars in today's money. In honor of Elihu, and to commemorate his earlier shipbuilding, the village of Padanaram was called Akin's Wharf for 20 years after the war.

In 1793 Davolls General Store was established in the Russells Mills area.

Civil War

Prewar years

In the years before the

In the years before the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, in the early 1840s, Dartmouth launched a whaling vessel owned by Sanford and Sherman, had a bowling Alley burn down, as well as hosting an Abstinence rally with some shops refusing to sell Rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is often aged in barrels of oak. Rum originated in the Caribbean in the 17th century, but today it is produced i ...

and cider. In 1855, the town was home to one cotton mill

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Although some were driven ...

, three salt works, one factory that made railroad car

A railroad car, railcar (American English, American and Canadian English), railway wagon, railway carriage, railway truck, railwagon, railcarriage or railtruck (British English and International Union of Railways, UIC), also called a tra ...

s, sleighs, wagons, and coaches, two tanneries, seven shoemakers, and five shingle mills, as well as launching one ship. The town had an abundance of livestock, including over a thousand sheep and cows. 850 swine. 428 oxen. As well as 4102 acres of English hay, and 712 acres of Indian corn

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native Americans ...

.

1861

The first town meeting in Dartmouth related to the Civil War was held on May 16, 1861, and contained a preamble about the towns stance on the war. At the onset of the Civil War, the first troops to be sent toWashington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

in Massachusetts were called by telegram on April 15, 1861, by Senator Henry Wilson. The Dartmouth men enlisted in the first call to arms were enlisted in the 18th, 33rd, 38th, and 40th regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, military service, service, or administrative corps, specialisation.

In Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of l ...

s.

1862

According to the New Bedford Republican Standard, on September 4, 1862, Dartmouth fulfilled its part in the quota sent fromWashington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

Which called for 20 companies, three full regiments, and four regiments of militia to be brought from Massachusetts. The fighting force was meant to be made up of the strongest companies in the state. Dartmouth had eight men in the 18th Regiment, twelve men in the 38th Regiment, and one in both the 33rd and 40th.

In 1862, the town of Dartmouth voted to pay volunteers for the war. William Francis Bartlett stopped in Dartmouth after being wounded at the Siege of Yorktown

The siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown and the surrender at Yorktown, was the final battle of the American Revolutionary War. It was won decisively by the Continental Army, led by George Washington, with support from the Ma ...

. Several Dartmouth soldiers were at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

. George Lawton, Leander Collins, Robert H. Dunham, Frederick Smith, Joseph Head, Abraham R. Cowen, and John Smith were all present at the battle. They served in the 8th Battery MVM, the 16th, and 18th Regiment MVI, and the light artillery. In the New Bedford Republican Standards August 18, 182 issue it was reported that a Dartmouth town meeting voted to pay a $200 bounty to nine-month volunteers. In the month following the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

, many Dartmouth men joined the 3rd regiment of infantry in the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. They completed training at Camp Joe Hooker in Lakeville before leaving for Boston on October 22, 1862. They then embarked on the Merrimac and Mississippi for New Bern, North Carolina

New Bern, formerly Newbern, is a city in Craven County, North Carolina, United States, and its county seat. It had a population of 31,291 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is located at the confluence of the Neuse River, Neuse a ...

. Dartmouth then proceeded to fulfil its second quota, sending 20 men to Company F, and three to company G. At the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army, Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Major general ( ...

, Private Joseph Head, a machinist, Frederick Smith, a seaman, and Frederick H. Russell—all from Dartmouth—were injured. Isaac S. Barker, a carpenter, was killed.

1863

On March 3, 1863, the town voted to raise $5,000 for monthly payments of aid for families of volunteers. Acting Master James Taylor of theironclad warship

An ironclad was a steam-propelled warship protected by steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. The firs ...

USS Keokuk arrived at his Dartmouth home on April 21, 1863. He looked "as if he had suffered anything but defeat," after the Keokuk attacked Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a historical Coastal defense and fortification#Sea forts, sea fort located near Charleston, South Carolina. Constructed on an artificial island at the entrance of Charleston Harbor in 1829, the fort was built in response to the W ...

and was riddled with bullet holes. Dartmouth soldiers also fought at the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was a three-day battle in the American Civil War, which was fought between the Union and Confederate armies between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, won by the Union, ...

. Three soldiers served in the 1st Regiment MVI, one in the 16th, and 33rd, and six in the 18th.

David Lewis Gifford was a Union Army soldier from Dartmouth, who received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

. He enlisted in December 1863, at age 1— as a member of the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment. Following the steamer the USS ''Boston'' running aground on an Oyster bed

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but no ...

, leaving 400 individuals within range of Confederate artillery. Gifford and four other men—led by George W. Brush

George Washington Brush (October 4, 1842 – November 18, 1927) was an American soldier, dentist, physician and politician. He served as a captain of a black company in the 34th Infantry Regiment U.S. Colored Troops in the Union Army during the ...

—manned a small boat and ferried stranded soldiers to a safe area.

1864

In April 1864, the people of Dartmouth voted to raise money to fill the quota of men for the service. At theBattle of Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 18 ...

, Bradford Little from Dartmouth was wounded, and Edwin C. Tripp from Dartmouth died at the Battle of Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses ...

. Three Dartmouth men were wounded at the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the siege of Petersburg, it was not a c ...

. Thos. C Lapham wrote to his uncle on Chase Road in Dartmouth from General Hospital Number One in Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Murfreesboro is a city in Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Its population was 165,430 according to the 2023 census estimate, up from 108,755 residents certified in 2010 United States census, 2010. Murfreesboro i ...

on January 20, 1864. He described the cold weather in what he called Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in Northern Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Washington, D.C., D.C. The city's population of 159,467 at the 2020 ...

, where he joined the Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General (C ...

and the battles in Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. He was mustered out in July 1865. Once returning to Dartmouth, he built a home and would eventually be rewarded the Boston Cane, which was awarded to the oldest living resident in Dartmouth, and would be buried in the Padanaram cemetery, where he used to be a caretaker. Private Humphrey R. Davis (a seaman from Dartmouth) died in May 1864 as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

in Andersonville Prison

The Andersonville National Historic Site, located near Andersonville, Georgia, preserves the former Andersonville Prison (also known as Camp Sumter), a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp during the final fourteen months of the American Civil Wa ...

. During the 1864 United States presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 8, 1864, near the end of the American Civil War. Incumbent President Abraham Lincoln of the National Union Party (United States), National Uni ...

, 384 people in Dartmouth voted to reelect Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

.

Modern history

The Watuppa Branch railroad started to serve Dartmouth in 1875.

During the late 19th century its coastline became a summer resort area for wealthy members of New England society.

The Watuppa Branch railroad started to serve Dartmouth in 1875.

During the late 19th century its coastline became a summer resort area for wealthy members of New England society.

Lincoln Park

Lincoln Park is a park along Lake Michigan on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois. Named after US president Abraham Lincoln, it is the city's largest public park and stretches for from Grand Avenue (500 N), on the south, to near Ardmore Avenu ...

was established in 1894 by the Union Street Railway Co. of New Bedford, and became an amusement park in the mid-20th century with rides such as the wooden roller coaster

A wooden roller coaster is a type of roller coaster classified by its wooden track, which consists of running rails made of flat steel strips mounted on laminated wood. The support structure is also typically made of wood, but may also be ...

The Comet.

Round Hill was the site of early-to-mid 20th century research into the uses of radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

and microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequency, frequencies between 300&n ...

s for aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' include fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air aircraft such as h ...

and communication

Communication is commonly defined as the transmission of information. Its precise definition is disputed and there are disagreements about whether Intention, unintentional or failed transmissions are included and whether communication not onl ...

by MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of modern technology and sc ...

scientists, including physicist Robert J. Van de Graaff

Robert Jemison Van de Graaff (December 20, 1901 – January 16, 1967) was an American physicist, noted for his design and construction of high-voltage Van de Graaff generators. He spent most of his career in the Massachusetts Institute of Tech ...

. There in 1933 he built the world's largest air-insulated Van de Graaff generator (now located at the Museum of Science (Boston)). It is also the site of the Green Mansion, the estate of "Colonel" Edward Howland Robinson Green, a colorful character who was son of the even more colorful and wildly eccentric Hetty Green.

In 1936, the Colonel died. The estate fell into disrepair as litigation over his vast fortune continued for eight years between his widow and his sister. Finally, the court ruled that Mrs. Hetty Sylvia Wilks, the Colonel's sister, was the sole beneficiary. In 1948, she bequeathed the entire estate to MIT, which used it for microwave and laser experiments. The giant antenna, which was a landmark to sailors on Buzzards Bay, was erected on top of a 50,000-gallon water tank. Although efforts were made to preserve the structure, it deteriorated and was demolished on November 19, 2007.

Another antenna was erected next to the mansion and used in the development of the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System. MIT continued to use Round Hill through 1964. It was sold to the Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded in 1540 ...

of New England and was used as a retreat house. The upper floors were divided into 64 individual rooms. The main floor was fitted with a chapel, a library, and meeting rooms.

In 1970 the Jesuits sold the land and buildings to Gratia R. Montgomery. In 1981, Mrs. Montgomery sold most of the land to a group of developers who have worked to preserve the history, grandeur and natural environment. The property is now a gated, mostly summer residential community on the water featuring a nine-hole golf course.

In 1980 Sunrise Bakery and Coffee Shop opened its first store in Dartmouth.

The town appeared in national news in 2013 when Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, then a university student at Dartmouth, participated in the Boston Marathon bombing

The Boston Marathon bombing, sometimes referred to as simply the Boston bombing, was an Islamist domestic terrorist attack that took place during the 117th annual Boston Marathon on April 15, 2013. Brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarna ...

.

Geography

According to theUnited States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau, officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the Federal statistical system, U.S. federal statistical system, responsible for producing data about the American people and American economy, econ ...

, the town has a total area of , of which is land and or, 37.53%, is water. It is the third largest town by area in Massachusetts.

The town is accessible by I-195 and US 6

U.S. Route 6 (US 6) or U.S. Highway 6 (US 6), also called the Grand Army of the Republic Highway, honoring the Grand Army of the Republic, American Civil War veterans association, is a main route of the United States Numbere ...

, which run parallel to each other through the northern-main business part of town from New Bedford to Westport on an east-west axis within a mile or two apart from one another.

Dartmouth includes the Southeastern Massachusetts Bioreserve that extends from Fall River into many protected forests of North Dartmouth in the Collins Corner, Faunce Corner, and Hixville sections of town. The Southeastern Massachusetts Bioreserve extends its protected forest lands into the Freetown-Fall River State Forest and beyond.

Numerous rivers flow north-south in Dartmouth, such as the Copicut River, Shingle Island River, Paskamanset River, Slocums River, Destruction Brook, and Little River. Dartmouth is divided into two primary sections: North Dartmouth (USPS

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or simply the Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal serv ...

ZIP code 02747) and South Dartmouth (USPS ZIP code 02748).

The town is bordered by Westport to the west, New Bedford

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast (Massachusetts), South Coast region. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, New Bedford had a ...

to the east, Fall River and Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

to the north, and Buzzards Bay

Buzzards Bay is a bay of the Atlantic Ocean adjacent to the U.S. state of Massachusetts. It is approximately 28 miles (45 kilometers) long by 8 miles (12 kilometers) wide. It is a popular destination for fishing, boating, and tourism. Buzzards ...

and the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

to the south.

The highest point in the town is near its northwestern corner, where the elevation rises to over above sea level north of Old Fall River Road.

Ecology and natural resource management

The Lloyd Center for Environmental Studies, located in South Dartmouth, is a non-profit organization that provides educational programs on aquatic environments in southeastern New England. It is across the mouth of the Slocums River from Demarest Lloyd State Park, a popular state beach known for its shallow waters. The Dartmouth Natural Resource Trust in Dartmouth, is anon-profit

A nonprofit organization (NPO), also known as a nonbusiness entity, nonprofit institution, not-for-profit organization, or simply a nonprofit, is a non-governmental (private) legal entity organized and operated for a collective, public, or so ...

land trust

Land trusts are nonprofit organizations which own and manage land, and sometimes waters. There are three common types of land trust, distinguished from one another by the ways in which they are legally structured and by the purposes for which th ...

incorporated in 1971 working to preserve and protect Dartmouth's natural resources. The trust has protected 5,400 acres of land since 1971 and owns 1,800 acres in Dartmouth as of 2020, including 35 miles of hiking trails, and ocean and river walks. The DNRT is accredited through the Land Trust Accreditation Commission, an independent program of the Land Trust Alliance. The Trust organizes such activities as photography tours, summer outdoor yoga series, bird watching, and plant identification. Its summer evening Barn Bash and winter fundraising auction are held annually. Since 1999, nearly 20 Boy Scouts from four troops have completed Eagle Scout projects through the DNRT. The Trust's headquarters building is located on the former Helfand Farm.

Transportation

Highway

Route 140 and Route 24 are located just outside Dartmouth's borders in New Bedford and Fall River, respectively, and both provide access toBoston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

and points north of the area. Route 177 begins just over Dartmouth's border with Westport, running west into Rhode Island and providing a link between the Newport-area (Tiverton, Little Compton, and Aquidneck Island) with the Fall River/New Bedford area. I-195 and US 6

U.S. Route 6 (US 6) or U.S. Highway 6 (US 6), also called the Grand Army of the Republic Highway, honoring the Grand Army of the Republic, American Civil War veterans association, is a main route of the United States Numbere ...

pass directly through Dartmouth, and also offer connections to the aforementioned three Massachusetts routes; the former provides access to Route 140, while the latter can be used to access Route 24 and Route 177.

Both Tiverton, RI and Little Compton, RI are geographically part of Massachusetts, lacking direct interstate highway connections with the rest of Rhode Island. Instead, smaller routes connect to the area (RI 138, MA/RI 24, RI 177/MA 177, and MA 81, and MA 88). Route 24 lies an average of 15 to 20 miles away in Tiverton, RI and Little Compton, RI, Route 177 and Route 140 and Route 24 are based upon old Indian routes and trails.

Bus

Public transportation in Dartmouth is primarily provided by the Southeastern Regional Transit Authority, which provides direct bus services between several points in Dartmouth and to the adjacent cities of New Bedford and Fall River. Transfers at either terminus offer connections to T.F. Green Airport via Plymouth & Brockton Street Railway and various locales in Rhode Island via Peter Pan Bus; the latter company also offers connections from New Bedford to Cape Cod and Boston. Direct daily bus service from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth toTaunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England. It is a market town and has a Minster (church), minster church. Its population in 2011 was 64,621. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century priory, monastic foundation, owned by the ...

and Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

was formerly offered via DATTCO buses; this service was cut back to only one express round-trip every Friday in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

.

Water

Despite its border along Buzzard's Bay, Dartmouth does not have any major water-based transport. However, the adjacent cities of Fall River and New Bedford offer several indirect ferry connections, with routes to Newport and Block Island from the former and Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and Cuttyhunk from the latter.Rail

The nearestMBTA Commuter Rail

The MBTA Commuter Rail system serves as the commuter rail arm of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority's (MBTA's) transportation coverage of Greater Boston in the United States. Trains run over of track on 12 lines to 142 stations. It ...

stations are and , both in New Bedford. The Massachusetts Coastal Railroad operates freight service through Dartmouth on the North Dartmouth Industrial Track ( Watuppa Branch).

Demographics

Government

Local government

Since 1928, Dartmouth has been governed by arepresentative town meeting

A representative town meeting, also called "limited town meeting", is a form of municipal legislature particularly common in Connecticut and Massachusetts, and permitted in Maine, Vermont and New Hampshire.

Representative town meetings function ...

, its legislative body, and Select Board

The select board or board of selectmen is commonly the executive arm of the government of New England towns in the United States. The board typically consists of three or five members, with or without staggered terms. Three is the most common num ...

, its executive body. Prior to 1928, the town was governed by an open town meeting. The Town Hall is located in the former Poole School, which also served as Dartmouth High School for several years. The town is patrolled by a central police department, located near Smith Mills on the site of the former Job S. Gidley School. There are five fire stations in the town divided among three fire districts, all of which are paid-call departments. There are two post offices (North Dartmouth, under the 02747 ZIP Code, and South Dartmouth, under the 02748 ZIP Code).

County government

The Bristol County Sheriff's Office maintains its administrative headquarters and operates several jail facilities in the Dartmouth Complex in North Dartmouth in Dartmouth. Jail facilities in the Dartmouth Complex include the Bristol County House Of Correction and Jail, the Bristol County Sheriff's Office Women's Center, and the C. Carlos Carreiro Immigration Detention Center.Facilities" Bristol County Sheriff's Office. Retrieved on January 30, 2012. "400 Faunce Corner Road, Dartmouth, MA 0274" and "Bristol County House Of Correction and Jail 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747" and "Bristol County Sheriff's Office Women's Center 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747" and "C. Carlos Carreiro Immigration Detention Center: 400 Faunce Corner Road North Dartmouth, MA 02747"

State & national government

Dartmouth is located in the Ninth Bristol state representative district, which includes all of Dartmouth as well as parts of Freetown, Lakeville, and New Bedford. The current state representative is Christopher Markey. The town is represented by Mark Montigny in the state senate in the Second Bristol and Plymouth district, which includes the city of New Bedford and the towns of Acushnet, Dartmouth, Fairhaven, and Mattapoisett. Dartmouth is the home of the Third Barracks of Troop D of the Massachusetts State Police, which relocated in 2006 from Route 6 to just north of the retail center of town on Faunce Corner Road. On the national level, the town is part of Massachusetts Congressional District 9, which is represented by William R. Keating. The state's junior (Class I) Senator isEd Markey

Edward John Markey (born July 11, 1946) is an American politician serving as the Seniority in the United States Senate, junior United States Senate, United States senator from the state of Massachusetts, a seat he has held since 2013. A member of ...

and the state's senior (Class II) Senator, is Elizabeth Warren

Elizabeth Ann Warren (née Herring; born June 22, 1949) is an American politician and former law professor who is the Seniority in the United States Senate, senior United States senator from the state of Massachusetts, serving since 2013. A mem ...

.

Libraries

Dartmouth established public library services in 1895. Today there are two libraries, the Southworth (Main) Library in South Dartmouth, and the Dartmouth Public Library—North Branch. The Southworth Library is part of the Sails Library Network, and shares a name with an older library. The older library, also called Southworth, was founded in 1878, by the pastor of the Congregational Church of South Dartmouth. The location of the Old Southworth library was purchased in 1888, and dedicated in 1890, due to funds from John Haywood Southworth—who furnished the library with 2,500 books in memory of his father. At the time the library required the purchase of a 50 cent library card to borrow books. The library was acquired by the town of Dartmouth in 1927. The building lacked space to contain books by 1958, and in April 1967 it was voted upon to build a new library with $515,000 on Dartmouth Street. In fiscal year 2008, the town of Dartmouth spent 1.5% ($865,864) of its budget on its public libraries—approximately $25 per person. Additionally, the Dartmouth Free Public library existed in Russells Mills, moving to various locations throughout the area—catering mostly to children at the local schools there.

Dartmouth established public library services in 1895. Today there are two libraries, the Southworth (Main) Library in South Dartmouth, and the Dartmouth Public Library—North Branch. The Southworth Library is part of the Sails Library Network, and shares a name with an older library. The older library, also called Southworth, was founded in 1878, by the pastor of the Congregational Church of South Dartmouth. The location of the Old Southworth library was purchased in 1888, and dedicated in 1890, due to funds from John Haywood Southworth—who furnished the library with 2,500 books in memory of his father. At the time the library required the purchase of a 50 cent library card to borrow books. The library was acquired by the town of Dartmouth in 1927. The building lacked space to contain books by 1958, and in April 1967 it was voted upon to build a new library with $515,000 on Dartmouth Street. In fiscal year 2008, the town of Dartmouth spent 1.5% ($865,864) of its budget on its public libraries—approximately $25 per person. Additionally, the Dartmouth Free Public library existed in Russells Mills, moving to various locations throughout the area—catering mostly to children at the local schools there.

Education

Dartmouth is governed by a single school department whose headquarters are in the former Bush Street School in Padanaram. The school department has been experiencing many changes in the past decade, with the opening of a new high school, and the moving of the former Middle School to the High School. The town currently has four elementary schools, Joseph P. DeMello, George H. Potter, James M. Quinn, and Andrew B. Cushman. The town has one middle school (located in the 1955-vintage High School building) next to the Town Hall, and one high school, the new Dartmouth High School, which opened in 2002 in the southern part of town. Its colors are Dartmouth green and white, and its fight song is "Glory to Dartmouth;" unlike the college, however, the school still uses the "Indians" nickname, with a stylized brave's head in profile as the logo which represents the Eastern Woodland Natives that first inhabited the area.

In addition to DHS, students may also attend Greater New Bedford Regional Vocational-Technical High School or Bristol County Agricultural High School. The town is also home to private schools including Bishop Stang, and Friends Academy.

Since the 1960s, Dartmouth has been home to the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth campus, located on Old Westport Road, just southwest of the Smith Mills section of town. The campus was the result of the unification of the Bradford Durfee College of Technology in Fall River and the New Bedford Institute of Textiles and Technology in New Bedford in 1962 to form the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute. The campus itself was begun in 1964 and its unique

Dartmouth is governed by a single school department whose headquarters are in the former Bush Street School in Padanaram. The school department has been experiencing many changes in the past decade, with the opening of a new high school, and the moving of the former Middle School to the High School. The town currently has four elementary schools, Joseph P. DeMello, George H. Potter, James M. Quinn, and Andrew B. Cushman. The town has one middle school (located in the 1955-vintage High School building) next to the Town Hall, and one high school, the new Dartmouth High School, which opened in 2002 in the southern part of town. Its colors are Dartmouth green and white, and its fight song is "Glory to Dartmouth;" unlike the college, however, the school still uses the "Indians" nickname, with a stylized brave's head in profile as the logo which represents the Eastern Woodland Natives that first inhabited the area.

In addition to DHS, students may also attend Greater New Bedford Regional Vocational-Technical High School or Bristol County Agricultural High School. The town is also home to private schools including Bishop Stang, and Friends Academy.

Since the 1960s, Dartmouth has been home to the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth campus, located on Old Westport Road, just southwest of the Smith Mills section of town. The campus was the result of the unification of the Bradford Durfee College of Technology in Fall River and the New Bedford Institute of Textiles and Technology in New Bedford in 1962 to form the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute. The campus itself was begun in 1964 and its unique Brutalist

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that emerged during the 1950s in the United Kingdom, among the reconstruction projects of the post-war era. Brutalist buildings are characterised by minimalist constructions that showcase the b ...

design was created by Paul Rudolph, then the head of Yale's School of Architecture. From 1969 until its inclusion into the University of Massachusetts

The University of Massachusetts is the Public university, public university system of the Massachusetts, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The university system includes six campuses (Amherst, Boston, Dartmouth, University of Massachusetts Lowell ...

system in 1991, the school was known as Southeastern Massachusetts University, reflecting the school's expansion into liberal arts. The campus has expanded over the years to its current size, with several sub-centers located in Fall River and New Bedford.

Culture

Notable artists associated with Dartmouth include Beatrice Chanler, Dwight William Tryon, Ernest Ludvig Ipsen, and Pete Souza.Dartmouth Community Band

The Dartmouth Community Band was established in 1974. The band plays regular summer concerts in Apponagansett Park as a part of the Dartmouth Parks and Rec. Summer Concert Series.Notable people

* Frederic Vaughan Abbot (1858–1928), U.S. Army brigadier general (summer resident) * Naseer Aruri (1934–2015), internationally recognized scholar-activist and expert on Middle East politics, U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East and human rights * Andrea Campbell (born 1982), Massachusetts attorney general * Ezekiel Cornell (1732–1800), member of Continental Congress 1780–1782 * Henry H. Crapo (1804–1869), 14thGovernor of Michigan

The governor of Michigan is the head of government of the U.S. state of Michigan. The current governor is Gretchen Whitmer, a member of the Democratic Party, who was inaugurated on January 1, 2019, as the state's 49th governor. She was re-ele ...

* William W. Crapo (1830–1926, U.S. House Representative representing Massachusetts' 1st District

* David Lewis Gifford (1844–1904), U.S Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

recipient, regarding his service during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

* Arthur Golden (born 1956), author, ''Memoirs of a Geisha'' (summer resident)

* Edward Howland Robinson Green (1868–1936), a businessman

* Edith Ellen Greenwood (born 1920), the first female recipient of the Soldier's Medal

* Huda Kattan (born 1983), CEO of Huda Beauty

* Téa Leoni (born 1966), film and television actress (summer resident)

* Arthur Lynch (born 1990), former football tight end for the Miami Dolphins

The Miami Dolphins are a professional American football team based in the Miami metropolitan area. The Dolphins compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member of the American Football Conference (AFC) AFC East, East division. The team ...

* Lewis Lee Millett Sr., recipient of Congressional Medal of Honor (Korean War)

* Brian Rose (born in 1976), a former Major League Baseball player

* Philip Sheridan (1831–1888), Union general in the American Civil War who died at his summer home in Nonquitt

* Peleg Slocum (1654–1733), Quaker and proprietor of Dartmouth

* Pete Souza (born 1954), former Chief Official White House Photographer (2009–2017), grew up in Dartmouth

* Jordan Todman (born 1990), was a football running back for six NFL teams

* Bernard Trafford (1871–1942), football player for Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

and chairman of First National Bank of Boston

* Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and self-identified socialist. Tucker was the editor and publisher of the American individualist anarchist periodical ''Liberty'' (1881–19 ...

(1854–1939), individualist, anarchist and egoist; English translator of the works of Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (; 25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner (; ), was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is oft ...

* Donald Eugene Webb (1931–1999), longest fugitive on the FBI's Most Wanted List

The FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives is a most wanted list maintained by the United States's Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The list arose from a conversation held in late 1949 between J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI, and William ...

and prime suspect in the murder of a Pennsylvania police chief who made headlines in 2017 when his remains were discovered buried in his wife's backyard.

In popular culture

* '' The Terror Factor'', a 2007 horror comedy film, is set in Dartmouth.See also

* Dartmouth, England *Dartmouth, Nova Scotia

Dartmouth ( ) (Scottish Gaelic, Scottish-Gaelic: Baile nan Loch) is a Urban area, built-up community of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Halifax Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia, Canada. Located on the eastern shore of Halifax Harbour, Dartmouth has 101 ...

References

Further reading

* *External links

Town of Dartmouth official website

{{Authority control 1650 establishments in Plymouth Colony Populated coastal places in Massachusetts Populated places established in 1650 Providence metropolitan area Towns in Bristol County, Massachusetts Towns in Massachusetts