Chief Justice Of Hungary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The chief justiceFallenbüchl 1988, p. 147. ( hu, királyi személynök,Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 107. la, personalis praesentiae regiae in judiciis locumtenens,Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 29. german: Königliche Personalis) was the personal legal representative of the King of Hungary, who issued decrees of judicial character on behalf of the monarch authenticated with the royal seal, performed national notarial activities and played an important role in the organisation of lawyers training. Later the chief justice was the head of the Royal Court of Justice ( hu, Királyi Ítélőtábla, la, Tabula Regia Iudiciaria) and the Tribunal of the Chief Justice ( hu, személynöki szék, la, sedes personalitia), the highest legal forum of civil cases.

The office of ''personalis'' evolved since the early 15th century within the royal chancellery. In the beginning, the king was represented by the secret chancellor in the judiciary (''judge of personal presence'').Markó 2006, p. 336. The first known chief justice was Janus Pannonius, a Croato-Hungarian humanist poet who returned to Hungary after finishing studies at the University of Padua in 1458, the coronation year of Matthias Corvinus. Pannonius served as chief justice until 1459, when he was elected as the Bishop of Pécs. Until the 1464 reform, the complete list of chief justices is unknown. It is certain that Albert Vetési, Bishop of Veszprém held the office for a short time around 1460.

From the 1370s, during the reign of Louis I of Hungary, Louis I, the lord chancellor also had a judicial function. He became ''judge of special presence'' ( la, specialis presentia regia). This position was held by Roman Catholicism, Roman Catholic prelates, therefore the judicial function was performed by their deputies. Consequently, a dual judicial system existed in the Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867), Kingdom of Hungary until the administrative reform of 1464.Kubinyi 2004, p. 40. He merged the two courts ("special" and "personal judicatures") and established the institution of chief justice as a full-fledged judge to the head of the Royal Court. The chancellery was also unified and the new office of "lord- and vice-chancellor" lost all of its judicial functions.

The Tribunal of the Chief Justice also established where the so-called "towns of chief justice" ( hu, személynöki város) forwarded those appeals concerning litigations. The tribunal chaired by the chief justice functioned as appellate court for the "towns of Master of the treasury, treasurer" ( hu, tárnoki város) too. According to the ''Tripartitum'' (1514) five settlements were towns of chief justice: Székesfehérvár, Esztergom, Levoča, Lőcse (Levoča), Sabinov, Kisszeben (Sabinov) and Skalica, Szakolca (Skalica). The status meant some independence, so was sought after by the towns. The ''Quadripartitum'' (1551), which never came to force, also mentions the seven mining towns of Upper Hungary as towns of chief justice.

The office of ''personalis'' evolved since the early 15th century within the royal chancellery. In the beginning, the king was represented by the secret chancellor in the judiciary (''judge of personal presence'').Markó 2006, p. 336. The first known chief justice was Janus Pannonius, a Croato-Hungarian humanist poet who returned to Hungary after finishing studies at the University of Padua in 1458, the coronation year of Matthias Corvinus. Pannonius served as chief justice until 1459, when he was elected as the Bishop of Pécs. Until the 1464 reform, the complete list of chief justices is unknown. It is certain that Albert Vetési, Bishop of Veszprém held the office for a short time around 1460.

From the 1370s, during the reign of Louis I of Hungary, Louis I, the lord chancellor also had a judicial function. He became ''judge of special presence'' ( la, specialis presentia regia). This position was held by Roman Catholicism, Roman Catholic prelates, therefore the judicial function was performed by their deputies. Consequently, a dual judicial system existed in the Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867), Kingdom of Hungary until the administrative reform of 1464.Kubinyi 2004, p. 40. He merged the two courts ("special" and "personal judicatures") and established the institution of chief justice as a full-fledged judge to the head of the Royal Court. The chancellery was also unified and the new office of "lord- and vice-chancellor" lost all of its judicial functions.

The Tribunal of the Chief Justice also established where the so-called "towns of chief justice" ( hu, személynöki város) forwarded those appeals concerning litigations. The tribunal chaired by the chief justice functioned as appellate court for the "towns of Master of the treasury, treasurer" ( hu, tárnoki város) too. According to the ''Tripartitum'' (1514) five settlements were towns of chief justice: Székesfehérvár, Esztergom, Levoča, Lőcse (Levoča), Sabinov, Kisszeben (Sabinov) and Skalica, Szakolca (Skalica). The status meant some independence, so was sought after by the towns. The ''Quadripartitum'' (1551), which never came to force, also mentions the seven mining towns of Upper Hungary as towns of chief justice.

During the first decades the position was held by ecclesiastical dignitaries. Thomas Drági was the first secular office-holder between 1486 and 1490. There had been a growing demand to fill the position by secular jurists and professionals on a permanent basis. That finally occurred at the beginning of the 16th century when the Act IV of 1507 decreed that the office must be occupied by a secular person with legal practice. Despite the new law the influential and powerful cardinal Tamás Bakócz chose his prelate relatives for the office. The importance of the office of chief justice was made clear when Buda became the permanent residence of the Tribunal of the Chief Justice. The Act LV of 1514 also emphasized the appointment of secular office-holders. After that the secular and ecclesiastical elite agreed with each other and István Werbőczy, creator of the ''Tripartitum'' was appointed later in 1516.

During the first decades the position was held by ecclesiastical dignitaries. Thomas Drági was the first secular office-holder between 1486 and 1490. There had been a growing demand to fill the position by secular jurists and professionals on a permanent basis. That finally occurred at the beginning of the 16th century when the Act IV of 1507 decreed that the office must be occupied by a secular person with legal practice. Despite the new law the influential and powerful cardinal Tamás Bakócz chose his prelate relatives for the office. The importance of the office of chief justice was made clear when Buda became the permanent residence of the Tribunal of the Chief Justice. The Act LV of 1514 also emphasized the appointment of secular office-holders. After that the secular and ecclesiastical elite agreed with each other and István Werbőczy, creator of the ''Tripartitum'' was appointed later in 1516.

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles III divided the Curia Regia into two courts in 1723: the ''Tabula Septemviralis'' (Court of the seven) and the ''Tabula Regia Iudiciaria'' (Royal Court of Justice). The latter functioned under the direction of the chief justice, in the case of prevention, of the elder Baron Court. The ''Tabula Regia Iudiciaria'' was constituted of two prelates, two Barons of the Court, two deputy judge advocates of the Kingdom: the vice Palatine, the deputy judge advocate of the Curia Regia, four protonotars, four assessors of the Kingdom, four assessors of the archdiocese, four adjunctive assessors.

The chief justice also had a political function: he became speaker of the occasionally convened lower house of the Diet of Hungary. During the Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867), Habsburg-dominated kingdom a customary law emerged whereby jurists to the office of chief justice were chosen from the Lesser nobility (Kingdom of Hungary), lesser nobility, however later sometimes Upper nobility (Kingdom of Hungary), aristocrats were also appointed to that position. The Tribunal of the Chief Justice was one of the positions used for the development, patronage and rise of a new aristocracy which was loyal to the House of Habsburg. For the new "official nobility" the position of chief justice was the springboard to obtain higher positions (mostly judge royal, president of the Hungarian Court Chamber, vice-chancellor).

János Zarka opened and presided over the last feudal Diet of 1848. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 the position became vacant. After the defeat of the War of Independence Francis Joseph I of Austria, Francis Joseph I applied neo-absolutist governance (''"Bach system"'') and integrated the Kingdom of Hungary to the Austrian Empire, Habsburg Empire. Due to the fall of the Bach system in 1861, the position of chief justice, among others, was revived again and István Melczer took the office. According to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 the judicial system had been converted and modernized; the chief justice lost all of its features and the position was officially discontinued.

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles III divided the Curia Regia into two courts in 1723: the ''Tabula Septemviralis'' (Court of the seven) and the ''Tabula Regia Iudiciaria'' (Royal Court of Justice). The latter functioned under the direction of the chief justice, in the case of prevention, of the elder Baron Court. The ''Tabula Regia Iudiciaria'' was constituted of two prelates, two Barons of the Court, two deputy judge advocates of the Kingdom: the vice Palatine, the deputy judge advocate of the Curia Regia, four protonotars, four assessors of the Kingdom, four assessors of the archdiocese, four adjunctive assessors.

The chief justice also had a political function: he became speaker of the occasionally convened lower house of the Diet of Hungary. During the Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867), Habsburg-dominated kingdom a customary law emerged whereby jurists to the office of chief justice were chosen from the Lesser nobility (Kingdom of Hungary), lesser nobility, however later sometimes Upper nobility (Kingdom of Hungary), aristocrats were also appointed to that position. The Tribunal of the Chief Justice was one of the positions used for the development, patronage and rise of a new aristocracy which was loyal to the House of Habsburg. For the new "official nobility" the position of chief justice was the springboard to obtain higher positions (mostly judge royal, president of the Hungarian Court Chamber, vice-chancellor).

János Zarka opened and presided over the last feudal Diet of 1848. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 the position became vacant. After the defeat of the War of Independence Francis Joseph I of Austria, Francis Joseph I applied neo-absolutist governance (''"Bach system"'') and integrated the Kingdom of Hungary to the Austrian Empire, Habsburg Empire. Due to the fall of the Bach system in 1861, the position of chief justice, among others, was revived again and István Melczer took the office. According to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 the judicial system had been converted and modernized; the chief justice lost all of its features and the position was officially discontinued.

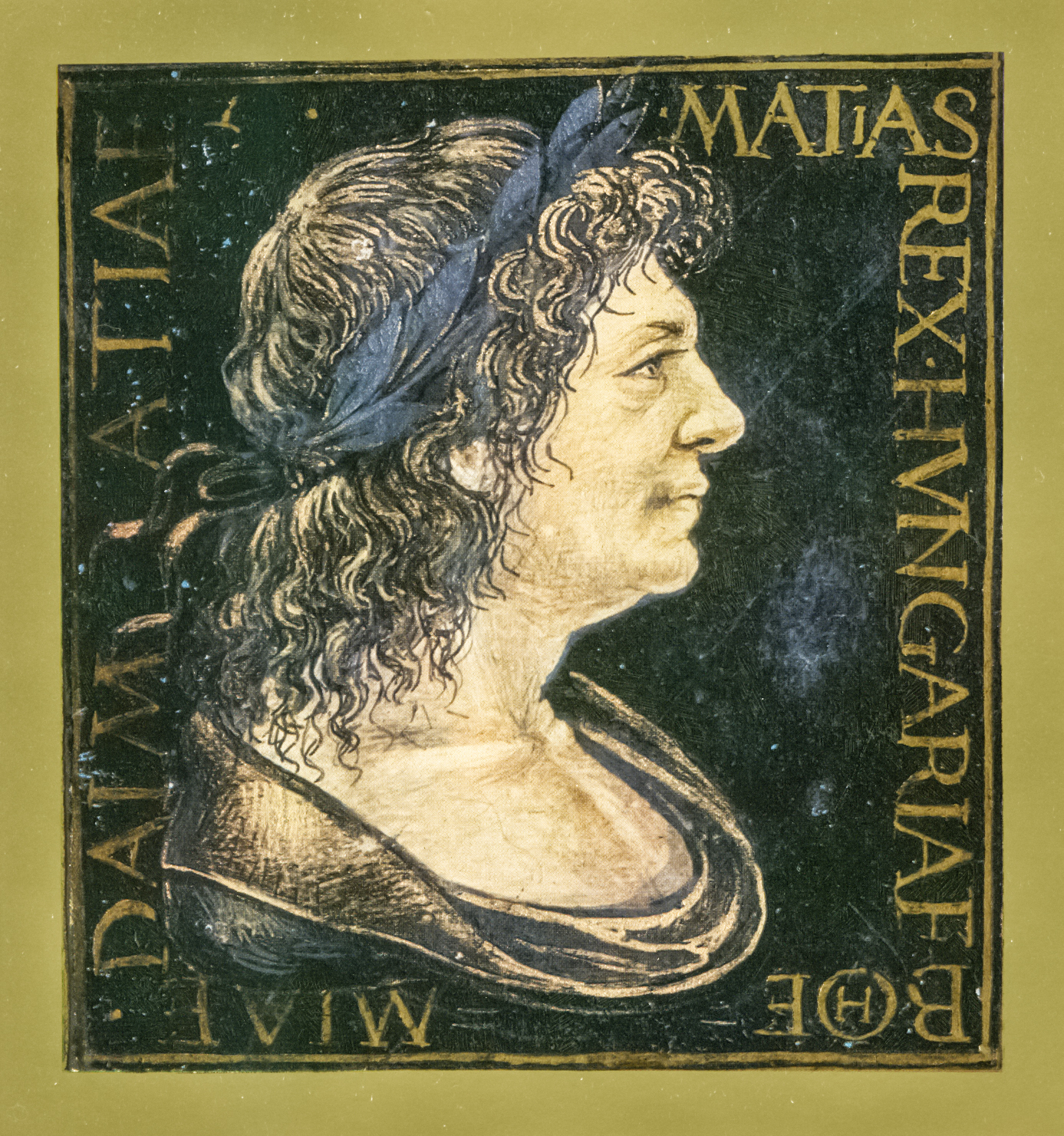

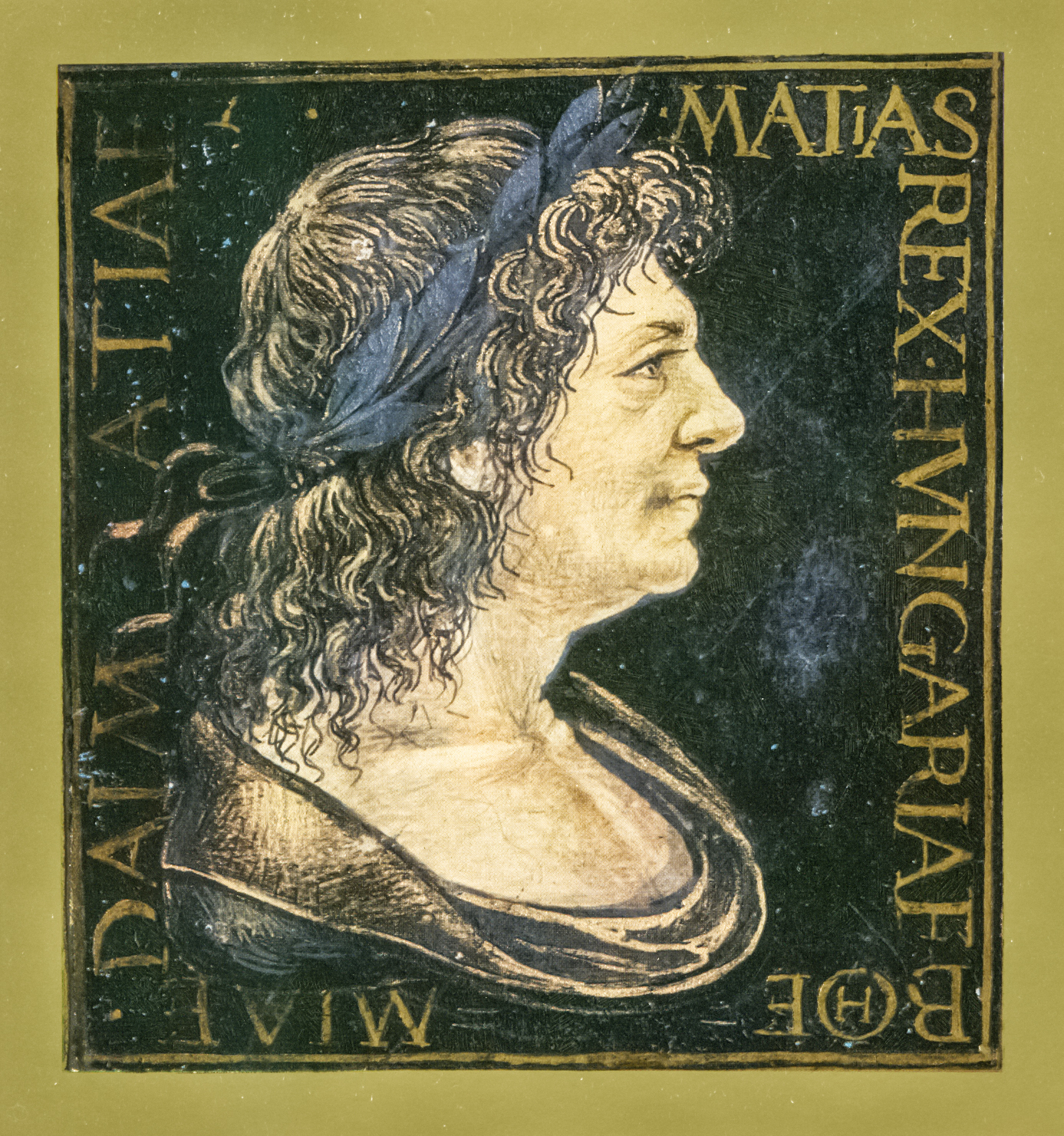

, Thomas Drági

, Matthias Corvinus

, first secular chief justice;Matucsinai was also secular when he held the office of chief justice, however later became a Roman Catholic prelate. Kubinyi 2000, p. 19. ''Drági Compendium''

, Kubinyi 2000, p. 19.Markó 2006, p. 337.

, -

, 1490–1494

,

, Thomas Drági

, Matthias Corvinus

, first secular chief justice;Matucsinai was also secular when he held the office of chief justice, however later became a Roman Catholic prelate. Kubinyi 2000, p. 19. ''Drági Compendium''

, Kubinyi 2000, p. 19.Markó 2006, p. 337.

, -

, 1490–1494

,  , Stephanus Crispus

, Stephanus Crispus

(Stephen Fodor) , Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II , nephew of Urban Nagylucsei; also Roman Catholic Diocese of Syrmia, bishop of Syrmia (1490–1494) , Véber 2009, p. 102.Bónis 1971, p. 334. , - , 1495–1501 , , Domokos Kálmáncsehi

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, also Roman Catholic Diocese of Oradea Mare, bishop of Várad (1495–1501); ''Breviarium'' (1481)

, Kubinyi 1957, p. 30.

, -

, 1502–1503

,

, Domokos Kálmáncsehi

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, also Roman Catholic Diocese of Oradea Mare, bishop of Várad (1495–1501); ''Breviarium'' (1481)

, Kubinyi 1957, p. 30.

, -

, 1502–1503

,  , Lucas Szegedi

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, bishop of Bosnia (1490–1493), treasurer (1490–1492), bishop of Zagreb (1500–1510)

, Markó 2006, p. 343.Kubinyi 1957, p. 32.

, -

, 1503–1512

,

, Lucas Szegedi

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, bishop of Bosnia (1490–1493), treasurer (1490–1492), bishop of Zagreb (1500–1510)

, Markó 2006, p. 343.Kubinyi 1957, p. 32.

, -

, 1503–1512

,  , István Erdődy

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, brother of Tamás Bakócz; remained in office despite Act IV of 1507; also Roman Catholic Diocese of Syrmia, bishop of Syrmia (1503–1505) and Roman Catholic Diocese of Nitra, bishop of Nyitra (1505–1512)

,

, -

, 1513–1514

,

, István Erdődy

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, brother of Tamás Bakócz; remained in office despite Act IV of 1507; also Roman Catholic Diocese of Syrmia, bishop of Syrmia (1503–1505) and Roman Catholic Diocese of Nitra, bishop of Nyitra (1505–1512)

,

, -

, 1513–1514

,  , János Erdődy (chief justice), János Erdődy

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, nephew of Tamás Bakócz; appointed despite Act IV of 1507; also Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Zagreb, bishop of Zagreb (1512–1518); resigned

, Bónis 1971, pp. 319–320.

, -

, 1516–1525

,

, János Erdődy (chief justice), János Erdődy

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, nephew of Tamás Bakócz; appointed despite Act IV of 1507; also Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Zagreb, bishop of Zagreb (1512–1518); resigned

, Bónis 1971, pp. 319–320.

, -

, 1516–1525

,  , István Werbőczy

, Louis II of Hungary, Louis II

, creator of the ''Tripartitum'' (1514); later Palatine of Hungary, palatine (1525–1526), chancellor for John Zápolya, John I (1526–1540)

, Markó 2006, p. 259.

, -

, 1525–1527

,

, István Werbőczy

, Louis II of Hungary, Louis II

, creator of the ''Tripartitum'' (1514); later Palatine of Hungary, palatine (1525–1526), chancellor for John Zápolya, John I (1526–1540)

, Markó 2006, p. 259.

, -

, 1525–1527

,  , Miklós Thuróczy

, Louis II of Hungary, Louis II

, Miklós Thuróczy

, Louis II of Hungary, Louis II

Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand I

John Zápolya, John I , also master of judgement for judge royal (1525–1527); he supported Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand I after the battle of Mohács (1526) , Markó 2006, p. 344.

A magyar királyi udvar tisztségviselői a középkorban

' ("Officials of the Hungarian royal court in the Middle Ages"). Rubicon, 1996/1–2. * Bónis, György (1971). ''A jogtudó értelmiség a Mohács előtti Magyarországon'' ("Hungarian intelligentsia having legal expertise in the period before the battle of Mohács"). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest. * Fraknói, Vilmos (1899).

Werbőczi István (1458–1541)

'. Magyar Történeti Életrajzok, Magyar Történelmi Társulat, Budapest. * Gergely, András (2000). ''The Hungarian State.Thousand years in Europe''. Korona Publishing House, Budapest. * Fallenbüchl, Zoltán (1988). ''Magyarország főméltóságai'' ("High Dignitaries in Hungary"). Maecenas Könyvkiadó. . * Horváth, Gyula Csaba (2011):

A 18. századi magyar főméltóságok családi kapcsolati hálózata

'. * Kubinyi, András (1957). "A kincstári személyzet a XV. század második felében." ''Tanulmányok Budapest Múltjából''. Vol. 12. (1957). 25–49. * Kubinyi, András (2000). "Vitéz János és Janus Pannonius politikája Mátyás uralkodása idején" ("The Politics of János Vitéz and Janus Pannonius During the Reign of King Matthias"). In: Bartók, István – Jankovits, László – Kecskeméti, Gábor (ed.). ''Humanista műveltség Pannóniában''. Művészetek Háza, University of Pécs. * Kubinyi, András (2004). "Adatok a Mátyás-kori királyi kancellária és az 1464. évi kancelláriai reform történetéhez." ''Publicationes Universitatis Miskolciensis Sectio Philosophica''. Vol. 9. No. 1. (2004). 25–58. * Markó, László (2006). ''A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig: Életrajzi Lexikon'' ("Great Officers of State in Hungary from King Saint Stephen to Our Days: A Biographical Encyclopedia"). 2nd edition, Helikon Kiadó. * Szende, Katalin (1999). "Was there a bourgeoisie in medieval Hungary?" In: Nagy, Balázs – Sebők, Marcell (ed.). ''... The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways...'' Central European University Press. Cloth. * Véber, János (2009). ''Két korszak határán, Váradi Péter pályaképe és írói életműve''. Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Ph.D. thesis.

1486. évi LXVIII. törvénycikk

*

1492. évi XLII. törvénycikk

*

1507. évi IV. törvénycikk

*

1514. évi LV. törvénycikk

*

1608. évi (k. e.) III. törvénycikk

*

1609. évi LXX. törvénycikk

*

1751. évi VI. törvénycikk

* {{in lang, hu}

1764/65. évi V. törvénycikk

National Archives of Hungary (MOL) – Judicial Archives (13th century – 1869)

Chief justices of Hungary, Legal history of Hungary 1464 establishments in Europe 1867 disestablishments in Europe

Origins

The office of ''personalis'' evolved since the early 15th century within the royal chancellery. In the beginning, the king was represented by the secret chancellor in the judiciary (''judge of personal presence'').Markó 2006, p. 336. The first known chief justice was Janus Pannonius, a Croato-Hungarian humanist poet who returned to Hungary after finishing studies at the University of Padua in 1458, the coronation year of Matthias Corvinus. Pannonius served as chief justice until 1459, when he was elected as the Bishop of Pécs. Until the 1464 reform, the complete list of chief justices is unknown. It is certain that Albert Vetési, Bishop of Veszprém held the office for a short time around 1460.

From the 1370s, during the reign of Louis I of Hungary, Louis I, the lord chancellor also had a judicial function. He became ''judge of special presence'' ( la, specialis presentia regia). This position was held by Roman Catholicism, Roman Catholic prelates, therefore the judicial function was performed by their deputies. Consequently, a dual judicial system existed in the Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867), Kingdom of Hungary until the administrative reform of 1464.Kubinyi 2004, p. 40. He merged the two courts ("special" and "personal judicatures") and established the institution of chief justice as a full-fledged judge to the head of the Royal Court. The chancellery was also unified and the new office of "lord- and vice-chancellor" lost all of its judicial functions.

The Tribunal of the Chief Justice also established where the so-called "towns of chief justice" ( hu, személynöki város) forwarded those appeals concerning litigations. The tribunal chaired by the chief justice functioned as appellate court for the "towns of Master of the treasury, treasurer" ( hu, tárnoki város) too. According to the ''Tripartitum'' (1514) five settlements were towns of chief justice: Székesfehérvár, Esztergom, Levoča, Lőcse (Levoča), Sabinov, Kisszeben (Sabinov) and Skalica, Szakolca (Skalica). The status meant some independence, so was sought after by the towns. The ''Quadripartitum'' (1551), which never came to force, also mentions the seven mining towns of Upper Hungary as towns of chief justice.

The office of ''personalis'' evolved since the early 15th century within the royal chancellery. In the beginning, the king was represented by the secret chancellor in the judiciary (''judge of personal presence'').Markó 2006, p. 336. The first known chief justice was Janus Pannonius, a Croato-Hungarian humanist poet who returned to Hungary after finishing studies at the University of Padua in 1458, the coronation year of Matthias Corvinus. Pannonius served as chief justice until 1459, when he was elected as the Bishop of Pécs. Until the 1464 reform, the complete list of chief justices is unknown. It is certain that Albert Vetési, Bishop of Veszprém held the office for a short time around 1460.

From the 1370s, during the reign of Louis I of Hungary, Louis I, the lord chancellor also had a judicial function. He became ''judge of special presence'' ( la, specialis presentia regia). This position was held by Roman Catholicism, Roman Catholic prelates, therefore the judicial function was performed by their deputies. Consequently, a dual judicial system existed in the Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867), Kingdom of Hungary until the administrative reform of 1464.Kubinyi 2004, p. 40. He merged the two courts ("special" and "personal judicatures") and established the institution of chief justice as a full-fledged judge to the head of the Royal Court. The chancellery was also unified and the new office of "lord- and vice-chancellor" lost all of its judicial functions.

The Tribunal of the Chief Justice also established where the so-called "towns of chief justice" ( hu, személynöki város) forwarded those appeals concerning litigations. The tribunal chaired by the chief justice functioned as appellate court for the "towns of Master of the treasury, treasurer" ( hu, tárnoki város) too. According to the ''Tripartitum'' (1514) five settlements were towns of chief justice: Székesfehérvár, Esztergom, Levoča, Lőcse (Levoča), Sabinov, Kisszeben (Sabinov) and Skalica, Szakolca (Skalica). The status meant some independence, so was sought after by the towns. The ''Quadripartitum'' (1551), which never came to force, also mentions the seven mining towns of Upper Hungary as towns of chief justice.

Functions and development

The Act LXVIII of 1486 listed the chief justice among the "ordinary judges" beside the Palatine of Hungary, palatine and the judge royal. The chief justice also served as keeper of the monarch's judicial seal. In contrast, the secret chancellor assumed his role in the arbitration only on special occasions. The ordinary judges were able to make judgements on any matter and also could appoint deputies and masters of judgement. In practice, this meant that the judicial power decoupled itself from the executive branch (the king). The Act XLII of 1492 (during the reign of Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II) also confirmed these authorities. During the first decades the position was held by ecclesiastical dignitaries. Thomas Drági was the first secular office-holder between 1486 and 1490. There had been a growing demand to fill the position by secular jurists and professionals on a permanent basis. That finally occurred at the beginning of the 16th century when the Act IV of 1507 decreed that the office must be occupied by a secular person with legal practice. Despite the new law the influential and powerful cardinal Tamás Bakócz chose his prelate relatives for the office. The importance of the office of chief justice was made clear when Buda became the permanent residence of the Tribunal of the Chief Justice. The Act LV of 1514 also emphasized the appointment of secular office-holders. After that the secular and ecclesiastical elite agreed with each other and István Werbőczy, creator of the ''Tripartitum'' was appointed later in 1516.

During the first decades the position was held by ecclesiastical dignitaries. Thomas Drági was the first secular office-holder between 1486 and 1490. There had been a growing demand to fill the position by secular jurists and professionals on a permanent basis. That finally occurred at the beginning of the 16th century when the Act IV of 1507 decreed that the office must be occupied by a secular person with legal practice. Despite the new law the influential and powerful cardinal Tamás Bakócz chose his prelate relatives for the office. The importance of the office of chief justice was made clear when Buda became the permanent residence of the Tribunal of the Chief Justice. The Act LV of 1514 also emphasized the appointment of secular office-holders. After that the secular and ecclesiastical elite agreed with each other and István Werbőczy, creator of the ''Tripartitum'' was appointed later in 1516.

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles III divided the Curia Regia into two courts in 1723: the ''Tabula Septemviralis'' (Court of the seven) and the ''Tabula Regia Iudiciaria'' (Royal Court of Justice). The latter functioned under the direction of the chief justice, in the case of prevention, of the elder Baron Court. The ''Tabula Regia Iudiciaria'' was constituted of two prelates, two Barons of the Court, two deputy judge advocates of the Kingdom: the vice Palatine, the deputy judge advocate of the Curia Regia, four protonotars, four assessors of the Kingdom, four assessors of the archdiocese, four adjunctive assessors.

The chief justice also had a political function: he became speaker of the occasionally convened lower house of the Diet of Hungary. During the Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867), Habsburg-dominated kingdom a customary law emerged whereby jurists to the office of chief justice were chosen from the Lesser nobility (Kingdom of Hungary), lesser nobility, however later sometimes Upper nobility (Kingdom of Hungary), aristocrats were also appointed to that position. The Tribunal of the Chief Justice was one of the positions used for the development, patronage and rise of a new aristocracy which was loyal to the House of Habsburg. For the new "official nobility" the position of chief justice was the springboard to obtain higher positions (mostly judge royal, president of the Hungarian Court Chamber, vice-chancellor).

János Zarka opened and presided over the last feudal Diet of 1848. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 the position became vacant. After the defeat of the War of Independence Francis Joseph I of Austria, Francis Joseph I applied neo-absolutist governance (''"Bach system"'') and integrated the Kingdom of Hungary to the Austrian Empire, Habsburg Empire. Due to the fall of the Bach system in 1861, the position of chief justice, among others, was revived again and István Melczer took the office. According to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 the judicial system had been converted and modernized; the chief justice lost all of its features and the position was officially discontinued.

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles III divided the Curia Regia into two courts in 1723: the ''Tabula Septemviralis'' (Court of the seven) and the ''Tabula Regia Iudiciaria'' (Royal Court of Justice). The latter functioned under the direction of the chief justice, in the case of prevention, of the elder Baron Court. The ''Tabula Regia Iudiciaria'' was constituted of two prelates, two Barons of the Court, two deputy judge advocates of the Kingdom: the vice Palatine, the deputy judge advocate of the Curia Regia, four protonotars, four assessors of the Kingdom, four assessors of the archdiocese, four adjunctive assessors.

The chief justice also had a political function: he became speaker of the occasionally convened lower house of the Diet of Hungary. During the Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867), Habsburg-dominated kingdom a customary law emerged whereby jurists to the office of chief justice were chosen from the Lesser nobility (Kingdom of Hungary), lesser nobility, however later sometimes Upper nobility (Kingdom of Hungary), aristocrats were also appointed to that position. The Tribunal of the Chief Justice was one of the positions used for the development, patronage and rise of a new aristocracy which was loyal to the House of Habsburg. For the new "official nobility" the position of chief justice was the springboard to obtain higher positions (mostly judge royal, president of the Hungarian Court Chamber, vice-chancellor).

János Zarka opened and presided over the last feudal Diet of 1848. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 the position became vacant. After the defeat of the War of Independence Francis Joseph I of Austria, Francis Joseph I applied neo-absolutist governance (''"Bach system"'') and integrated the Kingdom of Hungary to the Austrian Empire, Habsburg Empire. Due to the fall of the Bach system in 1861, the position of chief justice, among others, was revived again and István Melczer took the office. According to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 the judicial system had been converted and modernized; the chief justice lost all of its features and the position was officially discontinued.

List of known chief justices

Kingdom of Hungary (1000–1538)

}; also List of bishops and archbishops of Olomouc, bishop of Olomouc (1484–1490) , Markó 2006, p. 309.Bónis 1971, p. 19. , - , 1486–1490 , , Thomas Drági

, Matthias Corvinus

, first secular chief justice;Matucsinai was also secular when he held the office of chief justice, however later became a Roman Catholic prelate. Kubinyi 2000, p. 19. ''Drági Compendium''

, Kubinyi 2000, p. 19.Markó 2006, p. 337.

, -

, 1490–1494

,

, Thomas Drági

, Matthias Corvinus

, first secular chief justice;Matucsinai was also secular when he held the office of chief justice, however later became a Roman Catholic prelate. Kubinyi 2000, p. 19. ''Drági Compendium''

, Kubinyi 2000, p. 19.Markó 2006, p. 337.

, -

, 1490–1494

,  , Stephanus Crispus

, Stephanus Crispus(Stephen Fodor) , Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II , nephew of Urban Nagylucsei; also Roman Catholic Diocese of Syrmia, bishop of Syrmia (1490–1494) , Véber 2009, p. 102.Bónis 1971, p. 334. , - , 1495–1501 ,

, Domokos Kálmáncsehi

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, also Roman Catholic Diocese of Oradea Mare, bishop of Várad (1495–1501); ''Breviarium'' (1481)

, Kubinyi 1957, p. 30.

, -

, 1502–1503

,

, Domokos Kálmáncsehi

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, also Roman Catholic Diocese of Oradea Mare, bishop of Várad (1495–1501); ''Breviarium'' (1481)

, Kubinyi 1957, p. 30.

, -

, 1502–1503

,  , Lucas Szegedi

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, bishop of Bosnia (1490–1493), treasurer (1490–1492), bishop of Zagreb (1500–1510)

, Markó 2006, p. 343.Kubinyi 1957, p. 32.

, -

, 1503–1512

,

, Lucas Szegedi

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, bishop of Bosnia (1490–1493), treasurer (1490–1492), bishop of Zagreb (1500–1510)

, Markó 2006, p. 343.Kubinyi 1957, p. 32.

, -

, 1503–1512

,  , István Erdődy

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, brother of Tamás Bakócz; remained in office despite Act IV of 1507; also Roman Catholic Diocese of Syrmia, bishop of Syrmia (1503–1505) and Roman Catholic Diocese of Nitra, bishop of Nyitra (1505–1512)

,

, -

, 1513–1514

,

, István Erdődy

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, brother of Tamás Bakócz; remained in office despite Act IV of 1507; also Roman Catholic Diocese of Syrmia, bishop of Syrmia (1503–1505) and Roman Catholic Diocese of Nitra, bishop of Nyitra (1505–1512)

,

, -

, 1513–1514

,  , János Erdődy (chief justice), János Erdődy

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, nephew of Tamás Bakócz; appointed despite Act IV of 1507; also Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Zagreb, bishop of Zagreb (1512–1518); resigned

, Bónis 1971, pp. 319–320.

, -

, 1516–1525

,

, János Erdődy (chief justice), János Erdődy

, Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, Vladislaus II

, nephew of Tamás Bakócz; appointed despite Act IV of 1507; also Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Zagreb, bishop of Zagreb (1512–1518); resigned

, Bónis 1971, pp. 319–320.

, -

, 1516–1525

,  , István Werbőczy

, Louis II of Hungary, Louis II

, creator of the ''Tripartitum'' (1514); later Palatine of Hungary, palatine (1525–1526), chancellor for John Zápolya, John I (1526–1540)

, Markó 2006, p. 259.

, -

, 1525–1527

,

, István Werbőczy

, Louis II of Hungary, Louis II

, creator of the ''Tripartitum'' (1514); later Palatine of Hungary, palatine (1525–1526), chancellor for John Zápolya, John I (1526–1540)

, Markó 2006, p. 259.

, -

, 1525–1527

,  , Miklós Thuróczy

, Louis II of Hungary, Louis II

, Miklós Thuróczy

, Louis II of Hungary, Louis IIFerdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand I

John Zápolya, John I , also master of judgement for judge royal (1525–1527); he supported Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand I after the battle of Mohács (1526) , Markó 2006, p. 344.

Hungarian Civil War (1526–1538)

Kingdom of Hungary (1538–1867)

16–17th century

18–19th century

See also

* Judge royal * Curia RegiaFootnotes

References

* Bertényi, Iván (1996).A magyar királyi udvar tisztségviselői a középkorban

' ("Officials of the Hungarian royal court in the Middle Ages"). Rubicon, 1996/1–2. * Bónis, György (1971). ''A jogtudó értelmiség a Mohács előtti Magyarországon'' ("Hungarian intelligentsia having legal expertise in the period before the battle of Mohács"). Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest. * Fraknói, Vilmos (1899).

Werbőczi István (1458–1541)

'. Magyar Történeti Életrajzok, Magyar Történelmi Társulat, Budapest. * Gergely, András (2000). ''The Hungarian State.Thousand years in Europe''. Korona Publishing House, Budapest. * Fallenbüchl, Zoltán (1988). ''Magyarország főméltóságai'' ("High Dignitaries in Hungary"). Maecenas Könyvkiadó. . * Horváth, Gyula Csaba (2011):

A 18. századi magyar főméltóságok családi kapcsolati hálózata

'. * Kubinyi, András (1957). "A kincstári személyzet a XV. század második felében." ''Tanulmányok Budapest Múltjából''. Vol. 12. (1957). 25–49. * Kubinyi, András (2000). "Vitéz János és Janus Pannonius politikája Mátyás uralkodása idején" ("The Politics of János Vitéz and Janus Pannonius During the Reign of King Matthias"). In: Bartók, István – Jankovits, László – Kecskeméti, Gábor (ed.). ''Humanista műveltség Pannóniában''. Művészetek Háza, University of Pécs. * Kubinyi, András (2004). "Adatok a Mátyás-kori királyi kancellária és az 1464. évi kancelláriai reform történetéhez." ''Publicationes Universitatis Miskolciensis Sectio Philosophica''. Vol. 9. No. 1. (2004). 25–58. * Markó, László (2006). ''A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig: Életrajzi Lexikon'' ("Great Officers of State in Hungary from King Saint Stephen to Our Days: A Biographical Encyclopedia"). 2nd edition, Helikon Kiadó. * Szende, Katalin (1999). "Was there a bourgeoisie in medieval Hungary?" In: Nagy, Balázs – Sebők, Marcell (ed.). ''... The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways...'' Central European University Press. Cloth. * Véber, János (2009). ''Két korszak határán, Váradi Péter pályaképe és írói életműve''. Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Ph.D. thesis.

Laws and rules

*1486. évi LXVIII. törvénycikk

*

1492. évi XLII. törvénycikk

*

1507. évi IV. törvénycikk

*

1514. évi LV. törvénycikk

*

1608. évi (k. e.) III. törvénycikk

*

1609. évi LXX. törvénycikk

*

1751. évi VI. törvénycikk

* {{in lang, hu}

1764/65. évi V. törvénycikk

External links

National Archives of Hungary (MOL) – Judicial Archives (13th century – 1869)

Chief justices of Hungary, Legal history of Hungary 1464 establishments in Europe 1867 disestablishments in Europe