Charles Sanders Peirce on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

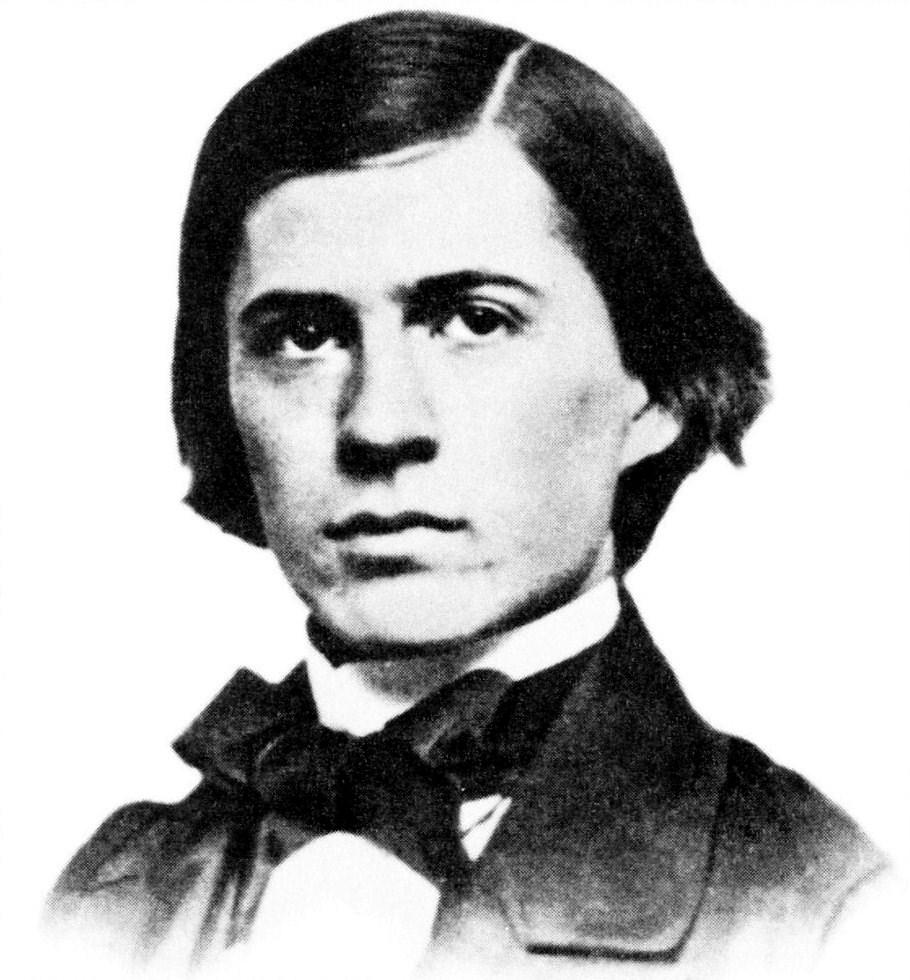

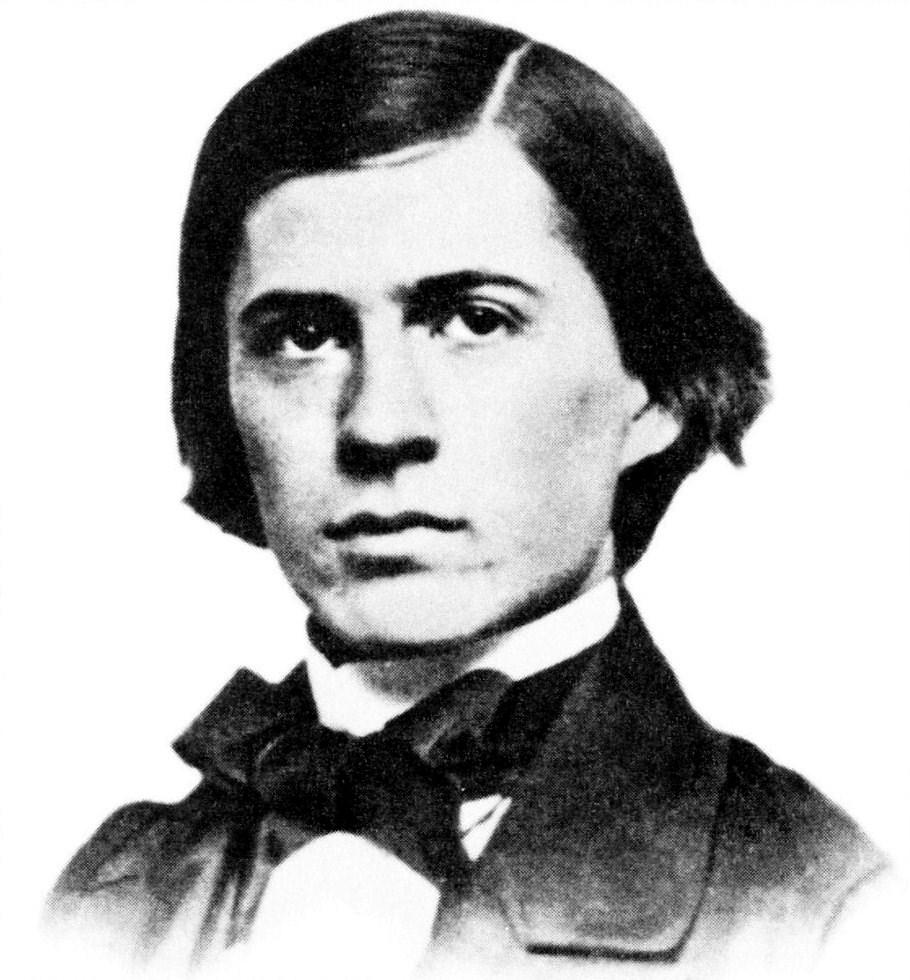

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher,

Peirce was born at 3 Phillips Place in

Peirce was born at 3 Phillips Place in

Charles Sanders Peirce

, ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' where he enjoyed his highly influential father's protection until the latter's death in 1880. That employment exempted Peirce from having to take part in the

(1994) The Life and Logical Contributions of O. H. Mitchell, Peirce's Gifted Student

/ref> several of whom were his graduate students.Houser, Nathan (1989),

, ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 4:xxxviii, find "Eighty-nine". Peirce's nontenured position at Hopkins was the only academic appointment he ever held. Brent documents something Peirce never suspected, namely that his efforts to obtain academic employment, grants, and scientific respectability were repeatedly frustrated by the covert opposition of a major Canadian-American scientist of the day,

In 1887, Peirce spent part of his inheritance from his parents to buy of rural land near

In 1887, Peirce spent part of his inheritance from his parents to buy of rural land near

Eprint

/ref> A. N. Whitehead, while reading some of Peirce's unpublished manuscripts soon after arriving at Harvard in 1924, was struck by how Peirce had anticipated his own "process" thinking. (On Peirce and process metaphysics, see Lowe 1964.)

Peirce Edition Project

(PEP), whose mission is to prepare a more complete critical chronological edition. Only seven volumes have appeared to date, but they cover the period from 1859 to 1892, when Peirce carried out much of his best-known work. ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 8 was published in November 2010; and work continues on ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 7, 9, and 11. In print and online. 1985: '' Historical Perspectives on Peirce's Logic of Science: A History of Science'', 2 volumes. Auspitz has said, "The extent of Peirce's immersion in the science of his day is evident in his reviews in the ''Nation'' ..and in his papers, grant applications, and publishers' prospectuses in the history and practice of science", referring latterly to ''Historical Perspectives''. Edited by Carolyn Eisele, back in print. 1992: '' Reasoning and the Logic of Things'' collects in one place Peirce's 1898 series of lectures invited by William James. Edited by Kenneth Laine Ketner, with commentary by

Peirce's most important work in pure mathematics was in logical and foundational areas. He also worked on linear algebra, Matrix (mathematics), matrices, various geometries, topology and Listing numbers, Bell numbers, Graph theory, graphs, the four-color problem, and the nature of continuity.

He worked on applied mathematics in economics, engineering, and map projections (such as the Peirce quincuncial projection), and was especially active in probability and statistics.Arthur W. Burks, Burks, Arthur W., "Review: Charles S. Peirce, ''The new elements of mathematics''", ''Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society'' v. 84, n. 5 (1978)

Peirce's most important work in pure mathematics was in logical and foundational areas. He also worked on linear algebra, Matrix (mathematics), matrices, various geometries, topology and Listing numbers, Bell numbers, Graph theory, graphs, the four-color problem, and the nature of continuity.

He worked on applied mathematics in economics, engineering, and map projections (such as the Peirce quincuncial projection), and was especially active in probability and statistics.Arthur W. Burks, Burks, Arthur W., "Review: Charles S. Peirce, ''The new elements of mathematics''", ''Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society'' v. 84, n. 5 (1978)

pp. 913–18 (PDF)

;Discoveries Peirce made a number of striking discoveries in formal logic and foundational mathematics, nearly all of which came to be appreciated only long after he died: In 1860 he suggested a cardinal arithmetic for infinite numbers, years before any work by Georg Cantor (who completed Georg Cantor#Teacher and researcher, his dissertation in 1867) and without access to Bernard Bolzano's 1851 (posthumous) ''Paradoxien des Unendlichen''.

In 1880–1881 he showed how Boolean algebra (logic), Boolean algebra could be done via a Functional completeness, repeated sufficient single binary operation (logical NOR), anticipating Henry M. Sheffer by 33 years. (See also De Morgan's Laws.)

In 1881 he set out the Peano axioms, axiomatization of natural number arithmetic, a few years before Richard Dedekind and Giuseppe Peano. In the same paper Peirce gave, years before Dedekind, the first purely cardinal definition of a finite set in the sense now known as "Dedekind-finite", and implied by the same stroke an important formal definition of an infinite set (Dedekind-infinite), as a Set (mathematics), set that can be put into a one-to-one correspondence with one of its proper subsets.

In 1885Peirce (1885), "On the Algebra of Logic: A Contribution to the Philosophy of Notation", ''American Journal of Mathematics'' 7, two parts, first part published 1885, pp

180–202

(see Houser i

in "Introduction" in ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 4). Presented, National Academy of Sciences, Newport, RI, October 14–17, 1884 (see ''The Essential Peirce'', 1

. 1885 is the year usually given for this work. Reprinted ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 3.359–403, ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 5:162–90, ''The Essential Peirce'', 1:225–28, in part. he distinguished between first-order and second-order quantification. In the same paper he set out what can be read as the first (primitive) axiomatic set theory, anticipating Zermelo by about two decades (Brady 2000,Brady, Geraldine (2000), ''From Peirce to Skolem: A Neglected Chapter in the History of Logic'', North-Holland/Elsevier Science BV, Amsterdam, Netherlands. pp. 132–33). In 1886, he saw that Boolean calculations could be carried out via electrical switches, anticipating Claude Shannon by more than 50 years. By the later 1890s he was devising existential graphs, a diagrammatic notation for the predicate calculus. Based on them are John F. Sowa's conceptual graphs and Sun-Joo Shin's diagrammatic reasoning.

;''The New Elements of Mathematics''

Peirce wrote drafts for an introductory textbook, with the working title ''The New Elements of Mathematics'', that presented mathematics from an original standpoint. Those drafts and many other of his previously unpublished mathematical manuscripts finally appeared in ''The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S. Peirce'' (1976), edited by mathematician

By the later 1890s he was devising existential graphs, a diagrammatic notation for the predicate calculus. Based on them are John F. Sowa's conceptual graphs and Sun-Joo Shin's diagrammatic reasoning.

;''The New Elements of Mathematics''

Peirce wrote drafts for an introductory textbook, with the working title ''The New Elements of Mathematics'', that presented mathematics from an original standpoint. Those drafts and many other of his previously unpublished mathematical manuscripts finally appeared in ''The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S. Peirce'' (1976), edited by mathematician

Excerpt with article's last five pages

documented that Frege's work on the logic of quantifiers had little influence on his contemporaries, although it was published four years before the work of Peirce and his student Oscar Howard Mitchell. Putnam found that mathematicians and logicians learned about the logic of quantifiers through the independent work of Peirce and Mitchell, particularly through Peirce's "On the Algebra of Logic: A Contribution to the Philosophy of Notation" (1885), published in the premier American mathematical journal of the day, and cited by Peano and Schröder, among others, who ignored Frege. They also adopted and modified Peirce's notations, typographical variants of those now used. Peirce apparently was ignorant of Frege's work, despite their overlapping achievements in logic,

Peirce was a working scientist for 30 years, and arguably was a professional philosopher only during the five years he lectured at Johns Hopkins. He learned philosophy mainly by reading, each day, a few pages of Immanuel Kant's ''Critique of Pure Reason'', in the original German, while a Harvard undergraduate. His writings bear on a wide array of disciplines, including mathematics,

Peirce was a working scientist for 30 years, and arguably was a professional philosopher only during the five years he lectured at Johns Hopkins. He learned philosophy mainly by reading, each day, a few pages of Immanuel Kant's ''Critique of Pure Reason'', in the original German, while a Harvard undergraduate. His writings bear on a wide array of disciplines, including mathematics,

Eprint

, placed by the ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', editors directly after "F.R.L." (1899, ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 1.135–40). and pragmatism commits one to anti-nominalist belief in the reality of the general (CP 5.453–57). For Peirce, First Philosophy, which he also called cenoscopy, is less basic than mathematics and more basic than the special sciences (of nature and mind). It studies positive phenomena in general, phenomena available to any person at any waking moment, and does not settle questions by resorting to special experiences.Peirce (1903), ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 1.180–202 and (1906) "The Basis of Pragmaticism", ''The Essential Peirce'', 2:372–73, see

Philosophy

at ''Commens Digital Companion to C.S. Peirce''. He Classification of the sciences (Peirce), divided such philosophy into (1) phenomenology (which he also called phaneroscopy or categorics), (2) normative sciences (esthetics, ethics, and logic), and (3) metaphysics; his views on them are discussed in order below.

Eprint

/ref> and as "the art of devising methods of research".Peirce (1882), "Introductory Lecture on the Study of Logic" delivered September 1882, ''Johns Hopkins University Circulars'', v. 2, n. 19, pp

11–12

(via Google), November 1882. Reprinted (''The Essential Peirce'', 1:210–14; ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 4:378–82; ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 7.59–76). The definition of logic quoted by Peirce is by Peter of Spain (author), Peter of Spain. More generally, as inference, "logic is rooted in the social principle", since inference depends on a standpoint that, in a sense, is unlimited. Peirce called (with no sense of deprecation) "mathematics of logic" much of the kind of thing which, in current research and applications, is called simply "logic". He was productive in both (philosophical) logic and logic's mathematics, which were connected deeply in his work and thought. Peirce argued that logic is formal semiotic: the formal study of signs in the broadest sense, not only signs that are artificial, linguistic, or symbolic, but also signs that are semblances or are indexical such as reactions. Peirce held that "all this universe is perfused with signs, if it is not composed exclusively of signs", along with their representational and inferential relations. He argued that, since all thought takes time, all thought is in signsPeirce, (1868), "Questions concerning certain Faculties claimed for Man", ''Journal of Speculative Philosophy'' v. 2, n. 2

pp. 103–14

On thought in signs, see p. 112. Reprinted ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 5.213–63 (on thought in signs, see 253), ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 2:193–211, ''The Essential Peirce'', 2:11–27. ''Arisbe'

and sign processes ("semiosis") such as the inquiry process. He Classification of the sciences (Peirce), divided logic into: (1) speculative grammar, or stechiology, on how signs can be meaningful and, in relation to that, what kinds of signs there are, how they combine, and how some embody or incorporate others; (2) logical critic, or logic proper, on the modes of inference; and (3) speculative or universal rhetoric, or methodeutic, the philosophical theory of inquiry, including pragmatism.

pp. 140–57

Reprinted ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 5.264–317, ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 2:211–42, ''The Essential Peirce'', 1:28–55. ''Arisbe'

Peirce, "Grounds of Validity of the Laws of Logic: Further Consequences of Four Incapacities", ''Journal of Speculative Philosophy'' v. II, n. 4

pp. 193–208

Reprinted ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 5.318–57, ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 2:242–72 (''Peirce Edition Project''

, ''The Essential Peirce'', 1:56–82. Peirce rejected mere verbal or hyperbolic doubt and first or ultimate principles, and argued that we have (as he numbered them): # No power of Introspection. All knowledge of the internal world comes by hypothetical reasoning from known external facts. # No power of Intuition (cognition without logical determination by previous cognitions). No cognitive stage is absolutely first in a process. All mental action has the form of inference. # No power of thinking without signs. A cognition must be interpreted in a subsequent cognition in order to be a cognition at all. # No conception of the absolutely incognizable. (The above sense of the term "intuition" is almost Kant's, said Peirce. It differs from the current looser sense that encompasses instinctive or anyway half-conscious inference.) Peirce argued that those incapacities imply the reality of the general and of the continuous, the validity of the modes of reasoning, and the falsity of philosophical René Descartes, Cartesianism (#Against Cartesianism, see below). Peirce rejected the conception (usually ascribed to Kant) of the unknowable thing-in-itself and later said that to "dismiss make-believes" is a prerequisite for pragmatism.

here

at peirce-l's Lyris archive. Note: Ransdell's quotes from ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 8.178–79 are also in ''The Essential Peirce'', 2:493–94, which gives their date as 1909; and his quote from ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 8.183 is also in ''The Essential Peirce'', 2:495–96, which gives its date as 1909. with the object, in which the object is found or from which it is recalled, as when a sign consists in a chance semblance of an absent object. Peirce used the word "determine" not in a strictly deterministic sense, but in a sense of "specializes", ''bestimmt'',Peirce, letter to William James, dated 1909, see ''The Essential Peirce'', 2:492. involving variable amount, like an influence.See

, collected by Robert Marty (U. of Perpignan, France). Peirce came to define representation and interpretation in terms of (triadic) determination. The object determines the sign to determine another sign—the interpretant—to be related to the object ''as the sign is related to the object'', hence the interpretant, fulfilling its function as sign of the object, determines a further interpretant sign. The process is logically structured to perpetuate itself, and is definitive of sign, object, and interpretant in general.

Dynamical Object

at ''Commens Digital Companion to C.S. Peirce''. All of those are special or partial objects. The object most accurately is the universe of discourse to which the partial or special object belongs. For instance, a perturbation of Pluto's orbit is a sign about Pluto but ultimately not only about Pluto. An object either (i) is ''immediate'' to a sign and is the object as represented in the sign or (ii) is a ''dynamic'' object, the object as it really is, on which the immediate object is founded "as on bedrock". # An ''interpretant'' (or ''interpretant sign'') is a sign's meaning or ramification as formed into a kind of idea or effect, an interpretation, human or otherwise. An interpretant is a sign (a) of the object and (b) of the interpretant's "predecessor" (the interpreted sign) as a sign of the same object. An interpretant either (i) is ''immediate'' to a sign and is a kind of quality or possibility such as a word's usual meaning, or (ii) is a ''dynamic'' interpretant, such as a state of agitation, or (iii) is a ''final'' or ''normal'' interpretant, a sum of the lessons which a sufficiently considered sign ''would'' have as effects on practice, and with which an actual interpretant may at most coincide. Some of the understanding needed by the mind depends on familiarity with the object. To know what a given sign denotes, the mind needs some experience of that sign's object, experience outside of, and collateral to, that sign or sign system. In that context Peirce speaks of collateral experience, collateral observation, collateral acquaintance, all in much the same terms.

''Commens Digital Companion to C.S. Peirce''

This typology classifies every sign according to the sign's own phenomenological category—the qualisign is a quality, a possibility, a "First"; the sinsign is a reaction or resistance, a singular object, an actual event or fact, a "Second"; and the legisign is a habit, a rule, a representational relation, a "Third". II. ''Icon, index, symbol'': This typology, the best known one, classifies every sign according to the category of the sign's way of denoting its object—the icon (also called semblance or likeness) by a quality of its own, the index by factual connection to its object, and the symbol by a habit or rule for its interpretant. III. ''Rheme, dicisign, argument'' (also called ''sumisign, dicisign, suadisign,'' also ''seme, pheme, delome,'' and regarded as very broadened versions of the traditional ''term, proposition, argument''): This typology classifies every sign according to the category which the interpretant attributes to the sign's way of denoting its object—the rheme, for example a term, is a sign interpreted to represent its object in respect of quality; the dicisign, for example a proposition, is a sign interpreted to represent its object in respect of fact; and the argument is a sign interpreted to represent its object in respect of habit or law. This is the culminating typology of the three, where the sign is understood as a structural element of inference. Every sign belongs to one class or another within (I) ''and'' within (II) ''and'' within (III). Thus each of the three typologies is a three-valued parameter for every sign. The three parameters are not independent of each other; many co-classifications are absent, for reasons pertaining to the lack of either habit-taking or singular reaction in a quality, and the lack of habit-taking in a singular reaction. The result is not 27 but instead ten classes of signs fully specified at this level of analysis.

''Case:'' These beans are beans from this bag.

''Result:'' These beans are white. Induction. ''Case:'' These beans are [randomly selected] from this bag.

''Result:'' These beans are white.

''Rule:'' All the beans from this bag are white. Hypothesis (Abduction). ''Rule:'' All the beans from this bag are white.

''Result:'' These beans [oddly] are white.

''Case:'' These beans are from this bag. Peirce 1883 in "A Theory of Probable Inference" ('' Studies in Logic'') equated hypothetical inference with the induction of characters of objects (as he had done in effect before). Eventually dissatisfied, by 1900 he distinguished them once and for all and also wrote that he now took the syllogistic forms and the doctrine of logical extension and comprehension as being less basic than he had thought. In 1903 he presented the following logical form for abductive inference: The logical form does not also cover induction, since induction neither depends on surprise nor proposes a new idea for its conclusion. Induction seeks facts to test a hypothesis; abduction seeks a hypothesis to account for facts. "Deduction proves that something ''must'' be; Induction shows that something ''actually is'' operative; Abduction merely suggests that something ''may be''." Peirce did not remain quite convinced that one logical form covers all abduction. In his methodeutic or theory of inquiry (see below), he portrayed abduction as an economic initiative to further inference and study, and portrayed all three modes as clarified by their coordination in essential roles in inquiry: hypothetical explanation, deductive prediction, inductive testing.

718

(via ''Internet Archive'' ) in ''Popular Science Monthly'', v. 12, pp. 705–18. Reprinted in ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 2.669–93, ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 3:290–305, ''The Essential Peirce'', 1:155–69, elsewhere. Peirce argued that even to argue against the independence and discoverability of truth and the real is to presuppose that there is, about that very question under argument, a truth with just such independence and discoverability. Peirce said that a conception's meaning consists in "Pragmatic maxim#2, all general modes of rational conduct" implied by "acceptance" of the conception—that is, if one were to accept, first of all, the conception as true, then what could one conceive to be consequent general modes of rational conduct by all who accept the conception as true?—the whole of such consequent general modes is the whole meaning. His pragmatism does not equate a conception's meaning, its intellectual purport, with the conceived benefit or cost of the conception itself, like a meme (or, say, propaganda), outside the perspective of its being true, nor, since a conception is general, is its meaning equated with any definite set of actual consequences or upshots corroborating or undermining the conception or its worth. His pragmatism also bears no resemblance to "vulgar" pragmatism, which misleadingly connotes a ruthless and Machiavellian search for mercenary or political advantage. Instead the pragmatic maxim is the heart of his pragmatism as a method of experimentational mental Pragmatic maxim#6, reflection arriving at conceptions in terms of conceivable confirmatory and disconfirmatory circumstances—a method hospitable to the formation of explanatory hypotheses, and conducive to the use and improvement of verification. Peirce's pragmatism, as method and theory of definitions and conceptual clearness, is part of his theory of inquiry, which he variously called speculative, general, formal or universal rhetoric or simply methodeutic.Se

rhetoric definitions

at ''Commens Digital Companion to C.S. Peirce''. He applied his pragmatism as a method throughout his work.

The Fixation of Belief

(1877), Peirce gives his take on the psychological origin and aim of inquiry. On his view, individuals are motivated to inquiry by desire to escape the feelings of anxiety and unease which Peirce takes to be characteristic of the state of doubt. Doubt is described by Peirce as an "uneasy and dissatisfied state from which we struggle to free ourselves and pass into the state of belief." Peirce uses words like “irritation” to describe the experience of being in doubt and to explain why he thinks we find such experiences to be motivating. The irritating feeling of doubt is appeased, Peirce says, through our efforts to achieve a settled state of satisfaction with what we land on as our answer to the question which led to that doubt in the first place. This settled state, namely, belief, is described by Peirce as “a calm and satisfactory state which we do not wish to avoid.” Our efforts to achieve the satisfaction of belief, by whichever methods we may pursue, are what Peirce calls “inquiry”. Four methods which Peirce describes as having been actually pursued throughout the history of thought are summarized below in the section after next.

Memoir 27

of Peirce's application to the Carnegie Institution: The hypothesis, being insecure, needs to have practical implications leading at least to mental tests and, in science, lending themselves to scientific tests. A simple but unlikely guess, if not costly to test for falsity, may belong first in line for testing. A guess is intrinsically worth testing if it has plausibility or reasoned objective probability, while Subjective probability, subjective likelihood, though reasoned, can be misleadingly seductive. Guesses can be selected for trial strategically, for their caution (for which Peirce gave as example the game of Twenty Questions), breadth, or incomplexity. One can discover only that which would be revealed through their sufficient experience anyway, and so the point is to expedite it; economy of research demands the leap, so to speak, of abduction and governs its art. 2. phase. Two stages: :i. Explication. Not clearly premised, but a deductive analysis of the hypothesis so as to render its parts as clear as possible. :ii. Demonstration: Deductive Argumentation, Euclidean in procedure. Explicit deduction of consequences of the hypothesis as predictions about evidence to be found. Corollary, Corollarial or, if needed, Theorematic. 3. phase. Evaluation of the hypothesis, inferring from observational or experimental tests of its deduced consequences. The long-run validity of the rule of induction is deducible from the principle (presuppositional to reasoning in general) that the real "is only the object of the final opinion to which sufficient investigation would lead"; in other words, anything excluding such a process would never be real. Induction involving the ongoing accumulation of evidence follows "a method which, sufficiently persisted in", will "diminish the error below any predesignate degree". Three stages: :i. Classification. Not clearly premised, but an inductive classing of objects of experience under general ideas. :ii. Probation: direct Inductive Argumentation. Crude or Gradual in procedure. Crude Induction, founded on experience in one mass (CP 2.759), presumes that future experience on a question will not differ utterly from all past experience (CP 2.756). Gradual Induction makes a new estimate of the proportion of truth in the hypothesis after each test, and is Qualitative or Quantitative. Qualitative Gradual Induction depends on estimating the relative evident weights of the various qualities of the subject class under investigation (CP 2.759; see also ''Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'', 7.114–20). Quantitative Gradual Induction depends on how often, in a fair sample of instances of ''S'', ''S'' is found actually accompanied by ''P'' that was predicted for ''S'' (CP 2.758). It depends on measurements, or statistics, or counting. :iii. Sentential Induction. "...which, by Inductive reasonings, appraises the different Probations singly, then their combinations, then makes self-appraisal of these very appraisals themselves, and passes final judgment on the whole result".

Eprint

, reprinted in part as "The Concept of God" in ''Philosophical Writings of Peirce'', J. Buchler, ed., 1940, pp. 375–78: In "s:A Neglected Argument for the Reality of God, A Neglected Argument for the Reality of God" (1908), Peirce sketches, for God's reality, an argument to a hypothesis of God as the Necessary Being, a hypothesis which he describes in terms of how it would tend to develop and become compelling in musement and inquiry by a normal person who is led, by the hypothesis, to consider as being purposed the features of the worlds of ideas, brute facts, and evolving habits (for example scientific progress), such that the thought of such purposefulness will "stand or fall with the hypothesis"; meanwhile, according to Peirce, the hypothesis, in supposing an "infinitely incomprehensible" being, starts off at odds with its own nature as a purportively true conception, and so, no matter how much the hypothesis grows, it both (A) inevitably regards itself as partly true, partly vague, and as continuing to define itself without limit, and (B) inevitably has God appearing likewise vague but growing, though God as the Necessary Being is not vague or growing; but the hypothesis will hold it to be ''more'' false to say the opposite, that God is purposeless. Peirce also argued that the will is free and (see Synechism) that there is at least an attenuated kind of immortality.

Arisbe: The Peirce Gateway

Joseph Ransdell, ed. Over 100 online writings by Peirce as of November 24, 2010, with annotations. Hundreds of online papers on Peirce. The peirce-l e-forum. Much else.

Center for Applied Semiotics (CAS)

(1998–2003), Donald Cunningham & Jean Umiker-Sebeok, Indiana U. * and previously et al., Pontifical Catholic U. of (PUC-SP), Brazil. In Portuguese, some English.

Commens Digital Companion to C.S. Peirce

Mats Bergman, Sami Paavola, & , formerl

Includes Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms with Peirce's definitions, often many per term across the decades, and the Digital Encyclopedia of Charles S. Peirce (#DECSP, old edition still at old website).

Peirce

Carlo Sini, Rossella Fabbrichesi, et al., U. of Milan, Italy. In Italian and English. Part o

Pragma

Charles S. Peirce Foundation

Co-sponsoring the 2014 Peirce International Centennial Congress (100th anniversary of Peirce's death).

Charles S. Peirce Society

br>

'. Quarterly journal of Peirce studies since spring 1965

of all issues.

Charles S. Peirce Studies

Brian Kariger, ed. *

Collegium for the Advanced Study of Picture Act and Embodiment

The Peirce Archive. Humboldt U, Berlin, Germany. Cataloguing Peirce's innumerable drawings & graphic materials

More info

(Prof. Aud Sissel Hoel).

Digital Encyclopedia of Charles S. Peirce

now at UFJF

& Ricardo Gudwin

at Unicamp

, eds., Universidade Estadual de Campinas, U. of , Brazil, in English. 84 authors listed, 51 papers online & more listed, as of January 31, 2009. Newer edition now at #CDPT, ''Commens Digital Companion to C.S. Peirce''.

Existential Graphs

Jay Zeman, ed., U. of Florida. Has 4 Peirce texts. * , ed., U. of Navarra, Spain. Big study site, Peirce & others in Spanish & English, bibliography, more.

Helsinki Peirce Research Center

(HPRC), Ahti-Veikko Pietarinen et al., U. of Helsinki.

His Glassy Essence

Autobiographical Peirce. Kenneth Laine Ketner.

Institute for Studies in Pragmaticism

Kenneth Laine Ketner, Clyde Hendrick, et al., Texas Tech U. Peirce's life and works.

International Research Group on Abductive Inference

et al., eds., U., Frankfurt, Germany. Uses frames. Click on link at bottom of its home page for English. Moved to University of Gießen, U. of Gießen, Germany

home page

not in English but see Artikel section there.

(1974–2003) – , U. of , France.

Minute Semeiotic

, U. of , Brazil. English, Portuguese.

Peirce

at ''Signo: Theoretical Semiotics on the Web'', Louis Hébert, director, supported by U. of Québec. Theory, application, exercises of Peirce'

Semiotics

an

Esthetics

English, French.

Peirce Edition Project (PEP)

Indiana U.–Purdue U. Indianapolis (IUPUI). André De Tienne, Nathan Houser, et al. Editors of the ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'' (W) and ''The Essential Peirce'' (EP) v. 2. Many study aids such as the Robin Catalog of Peirce's manuscripts & letters and:

Biographical introductions t

an

b

readable online.PEP's branch at

Working on ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 7: Peirce's work on the ''Century Dictionary''

Definition of the week

Peirce's Existential Graphs

Frithjof Dau, Germany

Peirce Research Group

Department of Philosophy "Piero Martinetti" – University of Milan, Italy.

Pragmatism Cybrary

David Hildebrand & John Shook.

(late 1990s), Germany). See ''Peirce Project Newsletter'' v. 3, n. 1

p. 13

wit

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Peirce, Charles Sanders Charles Sanders Peirce, 1839 births 1914 deaths 19th-century American mathematicians 19th-century American philosophers 20th-century American mathematicians 20th-century American philosophers American Episcopalians American logicians American semioticians American statisticians Analytic philosophers Anglican philosophers Communication scholars Critical theorists Epistemologists Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences alumni Idealists Johns Hopkins University faculty Lattice theorists Logicians Mathematicians from Massachusetts Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Metaphysicians Modal logicians The Nation (U.S. magazine) people Ontologists Panpsychism People from Cambridge, Massachusetts Philosophers from Massachusetts Philosophers from Pennsylvania Philosophers of education Philosophers of language Philosophers of mathematics Philosophers of mind Philosophers of science Philosophical theists Pragmatists Semioticians

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

ian, mathematician and scientist who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that considers words and thought as tools and instruments for prediction, problem solving, and action, and rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. ...

".

Educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for thirty years, Peirce made major contributions to logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

, a subject that, for him, encompassed much of what is now called epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

and the philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultim ...

. He saw logic as the formal branch of semiotics

Semiotics (also called semiotic studies) is the systematic study of sign processes ( semiosis) and meaning making. Semiosis is any activity, conduct, or process that involves signs, where a sign is defined as anything that communicates something ...

, of which he is a founder, which foreshadowed the debate among logical positivists

Logical positivism, later called logical empiricism, and both of which together are also known as neopositivism, is a movement in Western philosophy whose central thesis was the verification principle (also known as the verifiability criterion o ...

and proponents of philosophy of language

In analytic philosophy, philosophy of language investigates the nature of language and the relations between language, language users, and the world. Investigations may include inquiry into the nature of meaning, intentionality, reference, ...

that dominated 20th-century Western philosophy. Additionally, he defined the concept of abductive reasoning

Abductive reasoning (also called abduction,For example: abductive inference, or retroduction) is a form of logical inference formulated and advanced by American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce beginning in the last third of the 19th century ...

, as well as rigorously formulated mathematical induction

Mathematical induction is a method for proving that a statement ''P''(''n'') is true for every natural number ''n'', that is, that the infinitely many cases ''P''(0), ''P''(1), ''P''(2), ''P''(3), ... all hold. Informal metaphors help ...

and deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning is the mental process of drawing deductive inferences. An inference is deductively valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, i.e. if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be fals ...

. As early as 1886, he saw that logical operations could be carried out by electrical switching circuits. The same idea was used decades later to produce digital computers. See Also

In 1934, the philosopher Paul Weiss called Peirce "the most original and versatile of American philosophers and America's greatest logician".

Life

Peirce was born at 3 Phillips Place in

Peirce was born at 3 Phillips Place in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

. He was the son of Sarah Hunt Mills and Benjamin Peirce

Benjamin Peirce (; April 4, 1809 – October 6, 1880) was an American mathematician who taught at Harvard University for approximately 50 years. He made contributions to celestial mechanics, statistics, number theory, algebra, and the philoso ...

, himself a professor of astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and mathematics at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. At age 12, Charles read his older brother's copy of Richard Whately

Richard Whately (1 February 1787 – 8 October 1863) was an English academic, rhetorician, logician, philosopher, economist, and theologian who also served as a reforming Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin. He was a leading Broad Churchman ...

's ''Elements of Logic'', then the leading English-language text on the subject. So began his lifelong fascination with logic and reasoning. He went on to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree and a Master of Arts degree (1862) from Harvard. In 1863 the Lawrence Scientific School

The Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) is the engineering school within Harvard University's Faculty of Arts and Sciences, offering degrees in engineering and applied sciences to graduate students admitted ...

awarded him a Bachelor of Science degree, Harvard's first ''summa cum laude'' chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

degree. His academic record was otherwise undistinguished. At Harvard, he began lifelong friendships with Francis Ellingwood Abbot

Francis Ellingwood Abbot (November 6, 1836 – October 23, 1903) was an American philosopher and theologian who sought to reconstruct theology in accord with scientific method.

His lifelong romance with his wife Katharine Fearing Loring form ...

, Chauncey Wright

Chauncey Wright (September 10, 1830 – September 12, 1875) was an American philosopher and mathematician, who was an influential early defender of Darwinism and an important influence on American pragmatists such as Charles Sanders Peirce and Wil ...

, and William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

. One of his Harvard instructors, Charles William Eliot

Charles William Eliot (March 20, 1834 – August 22, 1926) was an American academic who was president of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909the longest term of any Harvard president. A member of the prominent Eliot family of Boston, he transfo ...

, formed an unfavorable opinion of Peirce. This proved fateful, because Eliot, while President of Harvard (1869–1909—a period encompassing nearly all of Peirce's working life), repeatedly vetoed Peirce's employment at the university.

Peirce suffered from his late teens onward from a nervous condition then known as "facial neuralgia", which would today be diagnosed as trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN or TGN), also called Fothergill disease, tic douloureux, or trifacial neuralgia is a long-term pain disorder that affects the trigeminal nerve, the nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as ...

. His biographer, Joseph Brent, says that when in the throes of its pain "he was, at first, almost stupefied, and then aloof, cold, depressed, extremely suspicious, impatient of the slightest crossing, and subject to violent outbursts of temper". Its consequences may have led to the social isolation of his later life.

Early employment

Between 1859 and 1891, Peirce was intermittently employed in various scientific capacities by theUnited States Coast Survey

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

and its successor, the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey (abbreviated USC&GS), known from 1807 to 1836 as the Survey of the Coast and from 1836 until 1878 as the United States Coast Survey, was the first scientific agency of the United States Government. It ...

,Burch, Robert (2001, 2010),Charles Sanders Peirce

, ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' where he enjoyed his highly influential father's protection until the latter's death in 1880. That employment exempted Peirce from having to take part in the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

; it would have been very awkward for him to do so, as the Boston Brahmin

The Boston Brahmins or Boston elite are members of Boston's traditional upper class. They are often associated with Harvard University; Anglicanism; and traditional Anglo-American customs and clothing. Descendants of the earliest English colonis ...

Peirces sympathized with the Confederacy. At the Survey, he worked mainly in geodesy

Geodesy ( ) is the Earth science of accurately measuring and understanding Earth's figure (geometric shape and size), orientation in space, and gravity. The field also incorporates studies of how these properties change over time and equivale ...

and gravimetry

Gravimetry is the measurement of the strength of a gravitational field. Gravimetry may be used when either the magnitude of a gravitational field or the properties of matter responsible for its creation are of interest.

Units of measurement

Gr ...

, refining the use of pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward the ...

s to determine small local variations in the Earth's gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

. He was elected a resident fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

in January 1867. The Survey sent him to Europe five times, first in 1871 as part of a group sent to observe a solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six month ...

. There, he sought out Augustus De Morgan, William Stanley Jevons

William Stanley Jevons (; 1 September 183513 August 1882) was an English economist and logician.

Irving Fisher described Jevons's book ''A General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy'' (1862) as the start of the mathematical method in ec ...

, and William Kingdon Clifford

William Kingdon Clifford (4 May 18453 March 1879) was an English mathematician and philosopher. Building on the work of Hermann Grassmann, he introduced what is now termed geometric algebra, a special case of the Clifford algebra named in his ...

, British mathematicians and logicians whose turn of mind resembled his own. From 1869 to 1872, he was employed as an assistant in Harvard's astronomical observatory, doing important work on determining the brightness of star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by its gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked ...

s and the shape of the Milky Way

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes our Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked eye ...

.Moore, Edward C., and Robin, Richard S., eds., (1964), ''Studies in the Philosophy of Charles Sanders Peirce, Second Series'', Amherst: U. of Massachusetts Press. On Peirce the astronomer, see Lenzen's chapter. On April 20, 1877, he was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

. Also in 1877, he proposed measuring the meter as so many wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tro ...

s of light of a certain frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

, the kind of definition employed from 1960 to 1983.

During the 1880s, Peirce's indifference to bureaucratic detail waxed while his Survey work's quality and timeliness waned. Peirce took years to write reports that he should have completed in months. Meanwhile, he wrote entries, ultimately thousands, during 1883–1909 on philosophy, logic, science, and other subjects for the encyclopedic ''Century Dictionary

''The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia'' is one of the largest encyclopedic dictionaries of the English language. In its day it was compared favorably with the ''Oxford English Dictionary,'' and frequently consulted for more factual informati ...

''. In 1885, an investigation by the Allison

Allison may refer to:

People

* Allison (given name)

* Allison (surname) (includes a list of people with this name)

* Eugene Allison Smith (1922-1980), American politician and farmer

Companies

* Allison Engine Company, American aircraft engine ...

Commission exonerated Peirce, but led to the dismissal of Superintendent Julius Hilgard and several other Coast Survey employees for misuse of public funds. In 1891, Peirce resigned from the Coast Survey at Superintendent Thomas Corwin Mendenhall

Thomas Corwin Mendenhall (October 4, 1841 – March 23, 1924) was an American autodidact physicist and meteorologist. He was the first professor hired at Ohio State University in 1873 and the superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Surve ...

's request.

Johns Hopkins University

In 1879, Peirce was appointed lecturer in logic atJohns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

, which had strong departments in areas that interested him, such as philosophy ( Royce and Dewey completed their Ph.D.s at Hopkins), psychology (taught by G. Stanley Hall

Granville Stanley Hall (February 1, 1846 – April 24, 1924) was a pioneering American psychologist and educator. His interests focused on human life span development and evolutionary theory. Hall was the first president of the American Psy ...

and studied by Joseph Jastrow

Joseph Jastrow (January 30, 1863 – January 8, 1944) was a Polish-born American psychologist, noted for inventions in experimental psychology, design of experiments, and psychophysics. He also worked on the phenomena of optical illusions, ...

, who coauthored a landmark empirical study with Peirce), and mathematics (taught by J. J. Sylvester, who came to admire Peirce's work on mathematics and logic). His '' Studies in Logic by Members of the Johns Hopkins University'' (1883) contained works by himself and Allan Marquand

Allan Marquand (; December 10, 1853 – September 24, 1924) was an art historian at Princeton University and a curator of the Princeton University Art Museum.

Early life

Marquand was born on December 10, 1853 in New York City. He was a son of ...

, Christine Ladd, Benjamin Ives Gilman

Benjamin Ives Gilman (1852–1933) was notable as the Secretary of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts from 1893 to 1925. Beginning with the museum as a curator and librarian, he held a variety of positions during this time. As Secretary, he focused ...

, and Oscar Howard Mitchell,Randall R. Diper(1994) The Life and Logical Contributions of O. H. Mitchell, Peirce's Gifted Student

/ref> several of whom were his graduate students.Houser, Nathan (1989),

, ''Writings of Charles S. Peirce'', 4:xxxviii, find "Eighty-nine". Peirce's nontenured position at Hopkins was the only academic appointment he ever held. Brent documents something Peirce never suspected, namely that his efforts to obtain academic employment, grants, and scientific respectability were repeatedly frustrated by the covert opposition of a major Canadian-American scientist of the day,

Simon Newcomb

Simon Newcomb (March 12, 1835 – July 11, 1909) was a Canadian–American astronomer, applied mathematician, and autodidactic polymath. He served as Professor of Mathematics in the United States Navy and at Johns Hopkins University. Born in Nov ...

. Peirce's efforts may also have been hampered by what Brent characterizes as "his difficult personality". In contrast, Keith Devlin

Keith J. Devlin (born 16 March 1947) is a British mathematician and popular science writer. Since 1987 he has lived in the United States. He has dual British-American citizenship.

believes that Peirce's work was too far ahead of his time to be appreciated by the academic establishment of the day and that this played a large role in his inability to obtain a tenured position.

Peirce's personal life undoubtedly worked against his professional success. After his first wife, Harriet Melusina Fay ("Zina"), left him in 1875, Peirce, while still legally married, became involved with Juliette, whose last name, given variously as Froissy and Pourtalai, and nationality (she spoke French) remains uncertain. When his divorce from Zina became final in 1883, he married Juliette. That year, Newcomb pointed out to a Johns Hopkins trustee that Peirce, while a Hopkins employee, had lived and traveled with a woman to whom he was not married; the ensuing scandal led to his dismissal in January 1884. Over the years Peirce sought academic employment at various universities without success. He had no children by either marriage.

Poverty

In 1887, Peirce spent part of his inheritance from his parents to buy of rural land near

In 1887, Peirce spent part of his inheritance from his parents to buy of rural land near Milford, Pennsylvania

Milford is a borough in Pike County, Pennsylvania and the county seat. Its population was 1,103 at the 2020 census. Located on the upper Delaware River, Milford is part of the New York metropolitan area.

History

The area along the Delaware Ri ...

, which never yielded an economic return. There he had an 1854 farmhouse remodeled to his design. The Peirces named the property " Arisbe". There they lived with few interruptions for the rest of their lives, Charles writing prolifically, much of it unpublished to this day (see Works

Works may refer to:

People

* Caddy Works (1896–1982), American college sports coach

* Samuel Works (c. 1781–1868), New York politician

Albums

* '' ''Works'' (Pink Floyd album)'', a Pink Floyd album from 1983

* ''Works'', a Gary Burton album ...

). Living beyond their means soon led to grave financial and legal difficulties. He spent much of his last two decades unable to afford heat in winter and subsisting on old bread donated by the local baker. Unable to afford new stationery, he wrote on the verso

' is the "right" or "front" side and ''verso'' is the "left" or "back" side when text is written or printed on a leaf of paper () in a bound item such as a codex, book, broadsheet, or pamphlet.

Etymology

The terms are shortened from Latin ...

side of old manuscripts. An outstanding warrant for assault and unpaid debts led to his being a fugitive in New York City for a while. Several people, including his brother James Mills Peirce

James Mills Peirce (May 1, 1834 – March 21, 1906) was an American mathematician and educator. He taught at Harvard University for almost 50 years.

Early life and family

He was the eldest son of Sarah Hunt (Mills) Peirce and Benjamin Peirce (18 ...

and his neighbors, relatives of Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

, settled his debts and paid his property taxes and mortgage.

Peirce did some scientific and engineering consulting and wrote much for meager pay, mainly encyclopedic dictionary entries, and reviews for ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'' (with whose editor, Wendell Phillips Garrison

Wendell Phillips Garrison (June 4, 1840 – February 27, 1907) was an American editor and author.

Early life

Garrison was born on June 4, 1840 at Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. He was the third son of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison ...

, he became friendly). He did translations for the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

, at its director Samuel Langley's instigation. Peirce also did substantial mathematical calculations for Langley's research on powered flight. Hoping to make money, Peirce tried inventing. He began but did not complete several books. In 1888, President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

appointed him to the Assay Commission.

From 1890 on, he had a friend and admirer in Judge Francis C. Russell of Chicago, who introduced Peirce to editor Paul Carus

Paul Carus (; 18 July 1852 – 11 February 1919) was a German-American author, editor, a student of comparative religion

and owner Edward C. Hegeler of the pioneering American philosophy journal ''The Monist

''The Monist: An International Quarterly Journal of General Philosophical Inquiry'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal in the field of philosophy. It was established in October 1890 by American publisher Edward C. Hegeler.

History

Init ...

'', which eventually published at least 14 articles by Peirce. He wrote many texts in James Mark Baldwin

James Mark Baldwin (January 12, 1861, Columbia, South Carolina – November 8, 1934, Paris) was an American philosopher and psychologist who was educated at Princeton under the supervision of Scottish philosopher James McCosh and who was one o ...

's '' Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology'' (1901–1905); half of those credited to him appear to have been written actually by Christine Ladd-Franklin

Christine Ladd-Franklin (December 1, 1847 – March 5, 1930) was an American psychologist, logician, and mathematician.

Early life and education

Christine Ladd, sometimes known by her nickname "Kitty", was born on December 1, 1847, in Winds ...

under his supervision. He applied in 1902 to the newly formed Carnegie Institution

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. Th ...

for a grant to write a systematic book describing his life's work. The application was doomed; his nemesis, Newcomb, served on the Carnegie Institution executive committee, and its president had been president of Johns Hopkins at the time of Peirce's dismissal.

The one who did the most to help Peirce in these desperate times was his old friend William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

, dedicating his ''Will to Believe'' (1897) to Peirce, and arranging for Peirce to be paid to give two series of lectures at or near Harvard (1898 and 1903). Most important, each year from 1907 until James's death in 1910, James wrote to his friends in the Boston intelligentsia to request financial aid for Peirce; the fund continued even after James died. Peirce reciprocated by designating James's eldest son as his heir should Juliette predecease him. It has been believed that this was also why Peirce used "Santiago" ("St. James" in English) as a middle name, but he appeared in print as early as 1890 as Charles Santiago Peirce. (See Charles Santiago Sanders Peirce

Charles Santiago Sanders Peirce was the adopted name of Charles Sanders Peirce (September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914), an American philosopher, logician, mathematician, and scientist. Peirce's name appeared in print as "Charles Santiago Pei ...

for discussion and references).

Peirce died destitute in Milford, Pennsylvania

Milford is a borough in Pike County, Pennsylvania and the county seat. Its population was 1,103 at the 2020 census. Located on the upper Delaware River, Milford is part of the New York metropolitan area.

History

The area along the Delaware Ri ...

, twenty years before his widow. Juliette Peirce kept the urn with Peirce's ashes at Arisbe. In 1934, Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

arranged for Juliette's burial in Milford Cemetery. The urn with Peirce's ashes was interred with Juliette.

Slavery, the American Civil War, and racism

Peirce grew up in a home where white supremacy was taken for granted, and Southern slavery was considered natural. Until the outbreak of the Civil War, his father described himself as asecessionist

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics lea ...

, but after the outbreak of the war, this stopped and he became a Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

partisan, providing donations to the Sanitary Commission

The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was a private relief agency created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the United States Army (Federal / Northern / Union Army) during the American Civil W ...

, the leading Northern war charity. No members of the Peirce family volunteered or enlisted. Peirce shared his father's views and liked to use the following syllogism

A syllogism ( grc-gre, συλλογισμός, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

...

to illustrate the unreliability of traditional forms of logic, if one doesn't keep the meaning of the words, phrases, and sentences consistent throughout an argument:

All Men are equal in their political rights. Negroes are Men. Therefore, negroes are equal in political rights to whites.

Reception

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

(1959) wrote "Beyond doubt ..he was one of the most original minds of the later nineteenth century and certainly the greatest American thinker ever". Russell and Whitehead's ''Principia Mathematica

The ''Principia Mathematica'' (often abbreviated ''PM'') is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics written by mathematician–philosophers Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1913. ...

'', published from 1910 to 1913, does not mention Peirce (Peirce's work was not widely known until later).Anellis, Irving H. (1995), "Peirce Rustled, Russell Pierced: How Charles Peirce and Bertrand Russell Viewed Each Other's Work in Logic, and an Assessment of Russell's Accuracy and Role in the Historiography of Logic", ''Modern Logic'' 5, 270–328. ''Arisbe'Eprint

/ref> A. N. Whitehead, while reading some of Peirce's unpublished manuscripts soon after arriving at Harvard in 1924, was struck by how Peirce had anticipated his own "process" thinking. (On Peirce and process metaphysics, see Lowe 1964.)

Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the cl ...

viewed Peirce as "one of the greatest philosophers of all times". Yet Peirce's achievements were not immediately recognized. His imposing contemporaries William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

and Josiah Royce

Josiah Royce (; November 20, 1855 – September 14, 1916) was an American objective idealist philosopher and the founder of American idealism. His philosophical ideas included his version of personalism, defense of absolutism, idealism and his ...

admired him and Cassius Jackson Keyser

Cassius Jackson Keyser (15 May 1862 – 8 May 1947) was an American mathematician of pronounced philosophical inclinations.

Life

Keyser's initial higher education was at North West Ohio Normal School (now Ohio Northern University), then became ...

, at Columbia and C. K. Ogden

Charles Kay Ogden (; 1 June 1889 – 20 March 1957) was an English linguist, philosopher, and writer. Described as a polymath but also an Eccentricity (behavior), eccentric and Emic and etic, outsider, he took part in many ventures related to li ...

, wrote about Peirce with respect but to no immediate effect.

The first scholar to give Peirce his considered professional attention was Royce's student Morris Raphael Cohen

Morris Raphael Cohen ( be, Мо́рыс Рафаэ́ль Ко́эн; July 25, 1880 – January 28, 1947) was an American philosopher, lawyer, and legal scholar who united pragmatism with logical positivism and linguistic analysis. This union coale ...

, the editor of an anthology of Peirce's writings entitled '' Chance, Love, and Logic'' (1923), and the author of the first bibliography of Peirce's scattered writings. John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

studied under Peirce at Johns Hopkins. From 1916 onward, Dewey's writings repeatedly mention Peirce with deference. His 1938 ''Logic: The Theory of Inquiry'' is much influenced by Peirce. The publication of the first six volumes of ''Collected Papers'' (1931–1935), the most important event to date in Peirce studies and one that Cohen made possible by raising the needed funds, did not prompt an outpouring of secondary studies. The editors of those volumes, Charles Hartshorne

Charles Hartshorne (; June 5, 1897 – October 9, 2000) was an American philosopher who concentrated primarily on the philosophy of religion and metaphysics, but also contributed to ornithology. He developed the neoclassical idea of God and ...

and Paul Weiss, did not become Peirce specialists. Early landmarks of the secondary literature include the monographs by Buchler (1939), Feibleman (1946), and Goudge (1950), the 1941 PhD thesis by Arthur W. Burks

Arthur Walter Burks (October 13, 1915 – May 14, 2008) was an American mathematician who worked in the 1940s as a senior engineer on the project that contributed to the design of the ENIAC, the first general-purpose electronic digital computer. ...

(who went on to edit volumes 7 and 8), and the studies edited by Wiener and Young (1952). The Charles S. Peirce Society

The Charles S. Peirce Society (CSPS) is an American organization which purpose is to enhance "study of and communication about the work of Charles S. Peirce and its ongoing influence in the many fields of intellectual endeavor to which he contribu ...

was founded in 1946. Its ''Transactions'', an academic quarterly specializing in Peirce's pragmatism and American philosophy has appeared since 1965. (See Phillips 2014, 62 for discussion of Peirce and Dewey relative to transactionalism

Transactionalism is a pragmatic philosophical approach to how we are known, maintain health and relationships, and satisfy our goals for money and career through ambitious ecologies. It involves the study and accurate thinking required to plan a ...

.)

By 1943 such was Peirce's reputation, in the US at least, that ''Webster's Biographical Dictionary'' said that Peirce was "now regarded as the most original thinker and greatest logician of his time".

In 1949, while doing unrelated archival work, the historian of mathematics Carolyn Eisele

Carolyn Eisele (June 13, 1902 – January 15, 2000) was an American mathematician and history of mathematics, historian of mathematics known as an expert on the works of Charles Sanders Peirce....

Education and career

Eisele was born on June ...

(1902–2000) chanced on an autograph letter by Peirce. So began her forty years of research on Peirce, “the mathematician and scientist,” culminating in Eisele (1976, 1979, 1985). Beginning around 1960, the philosopher and historian of ideas

Intellectual history (also the history of ideas) is the study of the history of human thought and of intellectuals, people who conceptualize, discuss, write about, and concern themselves with ideas. The investigative premise of intellectual histor ...

Max Fisch (1900–1995) emerged as an authority on Peirce (Fisch, 1986).Fisch, Max (1986), ''Peirce, Semeiotic, and Pragmatism'', Kenneth Laine Ketner and Christian J. W. Kloesel, eds., Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana U. Press. He includes many of his relevant articles in a survey (Fisch 1986: 422–48) of the impact of Peirce's thought through 1983.

Peirce has gained an international following, marked by university research centers devoted to Peirce studies and pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that considers words and thought as tools and instruments for prediction, problem solving, and action, and rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. ...

in Brazil ( CeneP/CIEP), Finland ( HPRC and ), Germany ( Wirth's group, Hoffman's and Otte's group, and Deuser's and Härle's group), France ( L'I.R.S.C.E.), Spain ( GEP), and Italy ( CSP). His writings have been translated into several languages, including German, French, Finnish, Spanish, and Swedish. Since 1950, there have been French, Italian, Spanish, British, and Brazilian Peirce scholars of note. For many years, the North American philosophy department most devoted to Peirce was the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution ...

, thanks in part to the leadership of Thomas Goudge and David Savan. In recent years, U.S. Peirce scholars have clustered at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th st ...

, home of the Peirce Edition Project (PEP) –, and Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State or PSU) is a Public university, public Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related Land-grant university, land-grant research university with campuses and facilities throughout Pennsylvan ...

.

In recent years, Peirce's trichotomy of signs is exploited by a growing number of practitioners for marketing and design tasks.

John Deely

John Deely (April 26, 1942 – January 7, 2017) was an American philosopher and semiotician. He was a professor of philosophy at Saint Vincent College and Seminary in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Prior to this, he held the Rudman Chair of Grad ...

writes that Peirce was the last of the "moderns" and "first of the postmoderns". He lauds Peirce's doctrine of signs as a contribution to the dawn of the Postmodern

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or mode of discourseNuyen, A.T., 1992. The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194. characterized by skepticism toward the " grand narratives" of moderni ...

epoch. Dewey additionally comments that "Peirce stands...in a position analogous to the position occupied by Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman pr ...

as last of the Western Fathers

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fath ...

and first of the medievals".

Works

Peirce's reputation rests largely on academic papers published in American scientific and scholarly journals such as ''Proceedings of theAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

'', the ''Journal of Speculative Philosophy'', ''The Monist

''The Monist: An International Quarterly Journal of General Philosophical Inquiry'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal in the field of philosophy. It was established in October 1890 by American publisher Edward C. Hegeler.

History

Init ...

'', ''Popular Science

''Popular Science'' (also known as ''PopSci'') is an American digital magazine carrying popular science content, which refers to articles for the general reader on science and technology subjects. ''Popular Science'' has won over 58 awards, incl ...

Monthly'', the ''American Journal of Mathematics

The ''American Journal of Mathematics'' is a bimonthly mathematics journal published by the Johns Hopkins University Press.

History

The ''American Journal of Mathematics'' is the oldest continuously published mathematical journal in the United ...

'', ''Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

'', ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'', and others. See Articles by Peirce, published in his lifetime for an extensive list with links to them online. The only full-length book (neither extract nor pamphlet) that Peirce authored and saw published in his lifetime was '' Photometric Researches'' (1878), a 181-page monograph on the applications of spectrographic methods to astronomy. While at Johns Hopkins, he edited '' Studies in Logic'' (1883), containing chapters by himself and his graduate students

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and str ...

. Besides lectures during his years (1879–1884) as lecturer in Logic at Johns Hopkins, he gave at least nine series of lectures, many now published; see Lectures by Peirce.

After Peirce's death, Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

obtained from Peirce's widow the papers found in his study, but did not microfilm them until 1964. Only after Richard Robin (1967) catalogued this ''Nachlass

''Nachlass'' (, older spelling ''Nachlaß'') is a German word, used in academia to describe the collection of manuscripts, notes, correspondence, and so on left behind when a scholar dies. The word is a compound in German: ''nach'' means "after ...

'' did it become clear that Peirce had left approximately 1,650 unpublished manuscripts, totaling over 100,000 pages, mostly still unpublished except on microfilm. On the vicissitudes of Peirce's papers, see Houser (1989). Reportedly the papers remain in unsatisfactory condition.

The first published anthology of Peirce's articles was the one-volume '' Chance, Love and Logic: Philosophical Essays'', edited by Morris Raphael Cohen

Morris Raphael Cohen ( be, Мо́рыс Рафаэ́ль Ко́эн; July 25, 1880 – January 28, 1947) was an American philosopher, lawyer, and legal scholar who united pragmatism with logical positivism and linguistic analysis. This union coale ...

, 1923, still in print. Other one-volume anthologies were published in 1940, 1957, 1958, 1972, 1994, and 2009, most still in print. The main posthumous editions of Peirce's works in their long trek to light, often multi-volume, and some still in print, have included:

1931–1958: '' Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce'' (CP), 8 volumes, includes many published works, along with a selection of previously unpublished work and a smattering of his correspondence. This long-time standard edition drawn from Peirce's work from the 1860s to 1913 remains the most comprehensive survey of his prolific output from 1893 to 1913. It is organized thematically, but texts (including lecture series) are often split up across volumes, while texts from various stages in Peirce's development are often combined, requiring frequent visits to editors' notes. Edited (1–6) by Charles Hartshorne

Charles Hartshorne (; June 5, 1897 – October 9, 2000) was an American philosopher who concentrated primarily on the philosophy of religion and metaphysics, but also contributed to ornithology. He developed the neoclassical idea of God and ...