Challenger Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific program that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific program that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of

On its landmark journey circumnavigating the globe, 492 deep sea soundings, 133 bottom dredges, 151 open water trawls and 263 serial water temperature observations were taken. About 4,700 new species of marine life were discovered.

The scientific work was conducted by

On its landmark journey circumnavigating the globe, 492 deep sea soundings, 133 bottom dredges, 151 open water trawls and 263 serial water temperature observations were taken. About 4,700 new species of marine life were discovered.

The scientific work was conducted by  The first leg of the expedition took the ship from

The first leg of the expedition took the ship from  December 1873 to February 1874 was spent sailing on a roughly south-eastern track from the Cape of Good Hope to the parallel of 60 degrees south. The islands visited during this period were the

December 1873 to February 1874 was spent sailing on a roughly south-eastern track from the Cape of Good Hope to the parallel of 60 degrees south. The islands visited during this period were the  When the voyage resumed in June 1874, the route went east from Sydney to

When the voyage resumed in June 1874, the route went east from Sydney to  ''Challenger'' departed Japan in mid-June 1875, heading east across the Pacific to a point due north of the

''Challenger'' departed Japan in mid-June 1875, heading east across the Pacific to a point due north of the

One of the goals of the physical measurements for HMS Challenger was to be able to verify the hypothesis put forward by Carpenter on the link between temperature mapping and global ocean circulation in order to provide some answers on the phenomena involved in the major oceanic mixing. This study is a continuation of the preliminary exploratory missions of

One of the goals of the physical measurements for HMS Challenger was to be able to verify the hypothesis put forward by Carpenter on the link between temperature mapping and global ocean circulation in order to provide some answers on the phenomena involved in the major oceanic mixing. This study is a continuation of the preliminary exploratory missions of

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific program that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific program that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamic ...

. The expedition was named after the naval vessel that undertook the trip, .

The expedition, initiated by William Benjamin Carpenter

William Benjamin Carpenter CB FRS (29 October 1813 – 19 November 1885) was an English physician, invertebrate zoologist and physiologist. He was instrumental in the early stages of the unified University of London.

Life

Carpenter was born o ...

, was placed under the scientific supervision of Sir Charles Wyville Thomson—of the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

and Merchiston Castle School

Merchiston Castle School is an independent boarding school for boys in the suburb of Colinton in Edinburgh, Scotland. It has around 470 pupils and is open to boys between the ages of 7 and 18 as either boarding or day pupils; it was modelled ...

—assisted by five other scientists, including Sir John Murray, a secretary-artist and a photographer. The Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

obtained the use of ''Challenger'' from the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

and in 1872 modified the ship for scientific tasks, equipping it with separate laboratories for natural history and chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

. The expedition, led by Captain George Nares

Vice-Admiral Sir George Strong Nares (24 April 1831 – 15 January 1915) was a Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. He commanded the ''Challenger'' Expedition, and the British Arctic Expedition. He was highly thought of as a leader an ...

, sailed from Portsmouth, England

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dense ...

, on 21 December 1872. Other naval officers included Commander John Maclear

John Fiot Lee Pearse Maclear (27 June 1838 in Cape Town – 17 July 1907 in Niagara) was an admiral in the Royal Navy, known for his leadership in hydrography.

He is best known for being commander of during the ''Challenger'' Expedition (1 ...

. – pages 19 and 20 list the civilian staff and naval officers and crew, along with changes that took place during the voyage.

Under the scientific supervision of Thomson himself, the ship traveled approximately 68,890 nautical miles (79,280 miles; 127,580 kilometres) surveying and exploring. The result was the ''Report of the Scientific Results of the Exploring Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76'' which, among many other discoveries, catalogued over 4,000 previously unknown species. John Murray, who supervised the publication, described the report as "the greatest advance in the knowledge of our planet since the celebrated discoveries of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries". ''Challenger'' sailed close to Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

, but not within sight of it. However, it was the first scientific expedition to take pictures of icebergs.

Preparations

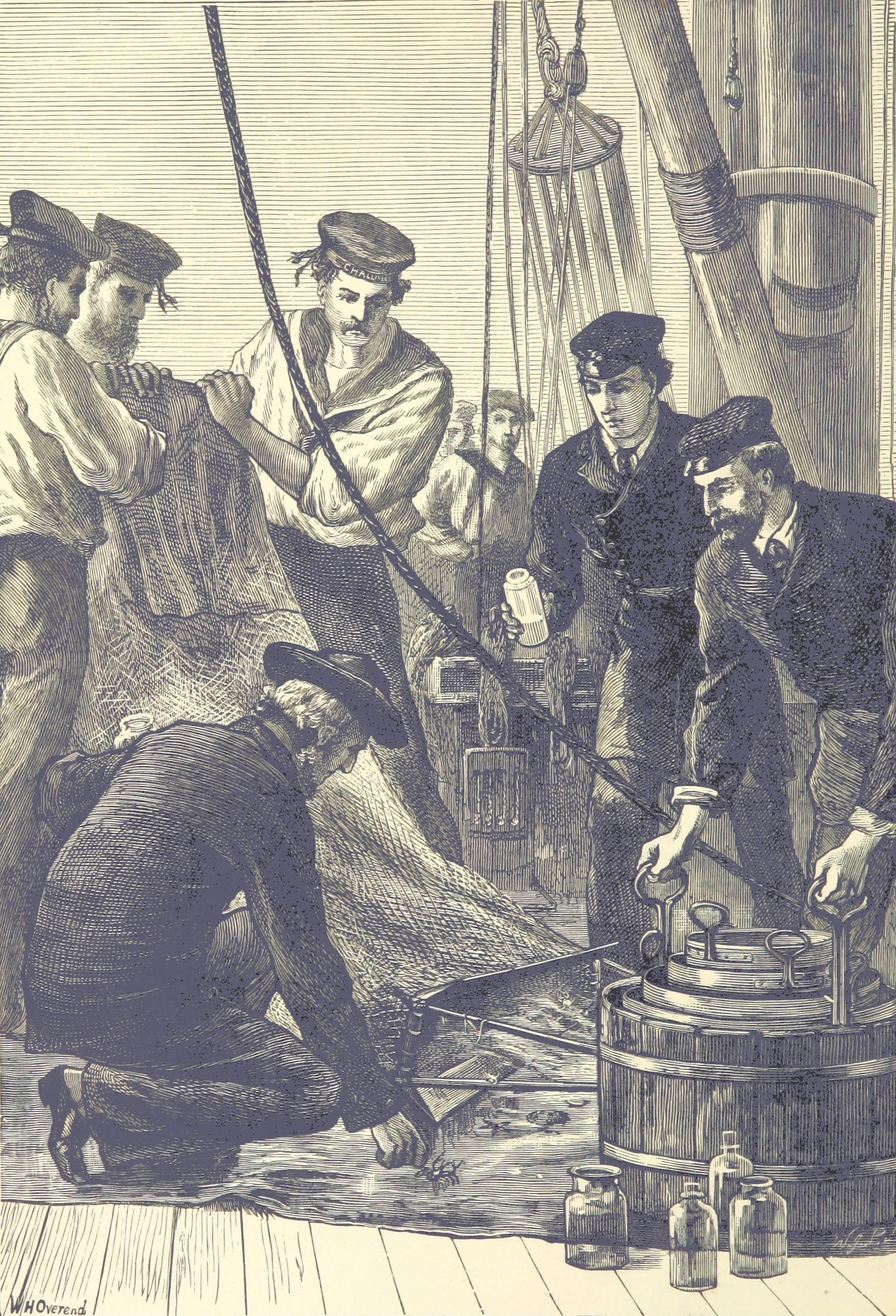

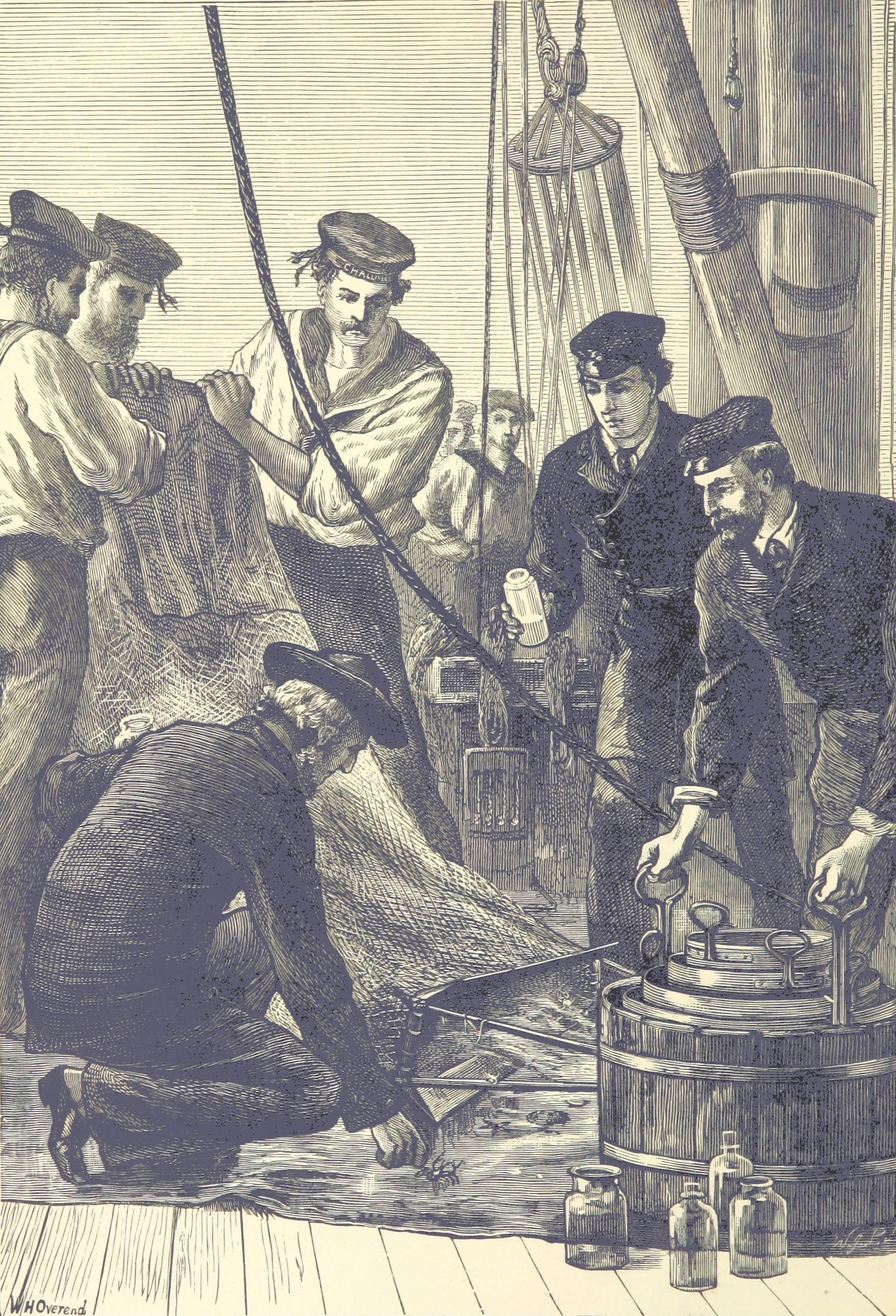

To enable it to probe the depths, 15 of ''Challenger'' 17 guns were removed and its spars reduced to make more space available. Laboratories, extra cabins and a specialdredging

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing da ...

platform were installed. ''Challenger'' used mainly sail power during the expedition; the steam engine was used only for dragging the dredge, station-keeping while taking soundings, and entering and leaving ports. It was loaded with specimen jars, filled with alcohol for preservation of samples, microscopes and chemical apparatus, trawls and dredges, thermometers, barometers, water sampling bottles, sounding leads, devices to collect sediment from the sea bed and great lengths of rope with which to suspend the equipment into the ocean depths.

Because of the novelty of the expedition, some of the equipment was invented or specially modified for the occasion. It carried of Italian hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

rope for sounding.

Expedition

On its landmark journey circumnavigating the globe, 492 deep sea soundings, 133 bottom dredges, 151 open water trawls and 263 serial water temperature observations were taken. About 4,700 new species of marine life were discovered.

The scientific work was conducted by

On its landmark journey circumnavigating the globe, 492 deep sea soundings, 133 bottom dredges, 151 open water trawls and 263 serial water temperature observations were taken. About 4,700 new species of marine life were discovered.

The scientific work was conducted by Wyville Thomson

Sir Charles Wyville Thomson (5 March 1830 – 10 March 1882) was a Scottish natural historian and marine zoologist. He served as the chief scientist on the Challenger expedition; his work there revolutionized oceanography and led to his knig ...

, John Murray, John Young Buchanan

John Young Buchanan FRSE FRS FCS (20 February 1844 – 16 October 1925) was a Scottish chemist, oceanographer and Arctic explorer. He was an important part of the Challenger Expedition.

Life

He was born in Partickhill, Glasgow on 20 February ...

, Henry Nottidge Moseley

Henry Nottidge Moseley FRS (14 November 1844 – 10 November 1891) was a British naturalist who sailed on the global scientific expedition of HMS ''Challenger'' in 1872 through 1876.

Life

Moseley was born in Wandsworth, London, the son of Hen ...

, and Rudolf von Willemoes-Suhm. Frank Evers Bed was appointed prosector

A prosector is a person with the special task of preparing a dissection for demonstration, usually in medical schools or hospitals. Many important anatomists began their careers as prosectors working for lecturers and demonstrators in anatomy and p ...

. The official expedition artist was John James Wild

John James Wild (born Jean Jacques Wild; 1824 – 3 June 1900) was a Swiss linguist, oceanographer and a natural history illustrator and lithographer, whose images were noted for their precision and clarity. He participated in the Challenger exped ...

. As well as Nares and Maclear, others that were part of the naval crew included Pelham Aldrich

Admiral Pelham Aldrich, CVO (8 December 1844 – 12 November 1930) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer, who became Admiral Superintendent of Portsmouth Docks.

Biography

He was born in Mildenhall, Suffolk, the son of Dr. Pelham Aldrich and El ...

, George Granville Campbell, and Andrew Francis Balfour (one of the sons of Scottish botanist John Hutton Balfour

John Hutton Balfour (15 September 1808 – 11 February 1884) was a Scottish botanist. Balfour became a Professor of Botany, first at the University of Glasgow in 1841, moving to the University of Edinburgh and also becoming the 7th Regius Kee ...

). Also among the officers was Thomas Henry Tizard

Thomas Henry Tizard (1839 – 17 February 1924) was an English oceanographer, hydrographic surveyor, and navigator.

He was born in Weymouth, Dorset and educated at the Royal Hospital School, Greenwich, at that time noted for its advanced mathe ...

, who had carried out important hydrographic observations on previous voyages. Though he was not among the civilian scientific staff, Tizard would later help write the official account of the expedition, and also become a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

.

The original ship's complement included 21 officers and around 216 crew members. By the end of the voyage, this had been reduced to 144 due to deaths, desertions, personnel being left ashore due to illness, and planned departures.

''Challenger'' reached Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

in December 1874, at which point Nares and Aldrich left the ship to take part in the British Arctic Expedition

The British Arctic Expedition of 1875–1876, led by Sir George Strong Nares, was sent by the British Admiralty to attempt to reach the North Pole via Smith Sound.

Although the expedition failed to reach the North Pole, the coasts of Greenland a ...

. The new captain was Frank Tourle Thomson. The second-in-command, and the most senior officer present throughout the entire expedition, was Commander John Maclear

John Fiot Lee Pearse Maclear (27 June 1838 in Cape Town – 17 July 1907 in Niagara) was an admiral in the Royal Navy, known for his leadership in hydrography.

He is best known for being commander of during the ''Challenger'' Expedition (1 ...

. Willemoes-Suhm died and was buried at sea on the voyage to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

. Lords Campbell and Balfour left the ship in Valparaiso, Chile, after being promoted.

The first leg of the expedition took the ship from

The first leg of the expedition took the ship from Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

(December 1872) south to Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

(January 1873) and then on to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. The next stops were Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

and the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

(both February 1873). The period from February to July 1873 was spent crossing the Atlantic westwards from the Canary Islands to the Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands ( es, Islas Vírgenes) are an archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. They are geologically and biogeographically the easternmost part of the Greater Antilles, the northern islands belonging to the Puerto Rico Trench and St. Cro ...

, then heading north to Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

, east to the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

, back to Madeira, and then south to the Cape Verde Islands

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

. During this period, there was a detour in April and May 1873, sailing from Bermuda north to Halifax and back, crossing the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension the North Atlantic Current, North Atlantic Drift, is a warm and swift Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida a ...

twice with the reverse journey crossing further to the east.The account of the expedition route given here is based on the 40 official nautical charts produced by the expedition, available at: This also includes a map of the expedition route.

After leaving the Cape Verde Islands in August 1873, the expedition initially sailed south-east and then headed west to reach St Paul's Rocks. From here, the route went south across the equator to Fernando de Noronha

Fernando de Noronha () is an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, part of the State of Pernambuco, Brazil, and located off the Brazilian coast. It consists of 21 islands and islets, extending over an area of . Only the eponymous main island is inha ...

during September 1873, and onwards that same month to Bahia

Bahia ( , , ; meaning "bay") is one of the 26 Federative units of Brazil, states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast Region of the country. It is the fourth-largest Brazilian state by population (after São Paulo (sta ...

(now called Salvador) in Brazil. The period from September to October 1873 was spent crossing the Atlantic from Bahia to the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

, touching at Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha (), colloquially Tristan, is a remote group of volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is the most remote inhabited archipelago in the world, lying approximately from Cape Town in South Africa, from Saint Helena ...

on the way.

December 1873 to February 1874 was spent sailing on a roughly south-eastern track from the Cape of Good Hope to the parallel of 60 degrees south. The islands visited during this period were the

December 1873 to February 1874 was spent sailing on a roughly south-eastern track from the Cape of Good Hope to the parallel of 60 degrees south. The islands visited during this period were the Prince Edward Islands

The Prince Edward Islands are two small uninhabited islands in the sub-Antarctic Indian Ocean that are part of South Africa. The islands are named Marion Island (named after Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, 1724–1772) and Prince Edward Island ...

, the Crozet Islands, the Kerguelen Islands, and Heard Island

The Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI) is an Australian external territory comprising a volcanic group of mostly barren Antarctic islands, about two-thirds of the way from Madagascar to Antarctica. The group's overall size ...

. February 1874 was spent travelling south and then generally eastwards in the vicinity of the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. S ...

, with sightings of icebergs, pack ice and whales. The route then took the ship north-eastward and away from the ice regions in March 1874, with the expedition reaching Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

in Australia later that month. The journey eastward along the coast from Melbourne to Sydney took place in April 1874, passing by Wilsons Promontory

Wilsons Promontory, is a peninsula that forms the southernmost part of the Australian mainland, located in the state of Victoria.

South Point at is the southernmost tip of Wilsons Promontory and hence of mainland Australia. Located at nea ...

and Cape Howe

Cape Howe is a coastal headland in eastern Australia, forming the south-eastern end of the Black-Allan Line, a portion of the border between New South Wales and Victoria.

History

Cape Howe was named by Captain Cook when he passed it on 20 A ...

.

When the voyage resumed in June 1874, the route went east from Sydney to

When the voyage resumed in June 1874, the route went east from Sydney to Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

in New Zealand, followed by a large loop north into the Pacific calling at Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

and Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

, and then back westward to Cape York in Australia by the end of August. The ship arrived in New Zealand in late June and left in early July. Before reaching Wellington (on New Zealand's North Island), brief stops were made at Port Hardy (on d'Urville Island

D'Urville Island (), Māori language, Māori name ' ('red heavens look to the south'), is an island in the Marlborough Sounds along the northern coast of the South Island of New Zealand. It was named after the France, French List of explorers, ...

) and Queen Charlotte Sound and ''Challenger'' passed through the Cook Strait

Cook Strait ( mi, Te Moana-o-Raukawa) separates the North and South Islands of New Zealand. The strait connects the Tasman Sea on the northwest with the South Pacific Ocean on the southeast. It is wide at its narrowest point,McLintock, A H, ...

to reach Wellington.

The route from Wellington to Tonga went along the east coast of New Zealand's North Island, and then north and east into the open Pacific, passing by the Kermadec Islands

The Kermadec Islands ( mi, Rangitāhua) are a subtropical island arc in the South Pacific Ocean northeast of New Zealand's North Island, and a similar distance southwest of Tonga. The islands are part of New Zealand. They are in total ar ...

en route to Tongatabu, the main island of the Tonga archipelago (then known as the Friendly Islands). The waters around the Fijian islands, a short distance to the north-west of Tonga, were surveyed during late July and early August 1874. The ship's course was then set westward, reaching Raine Island

Raine Island is a vegetated coral cay in total area situated on the outer edges of the Great Barrier Reef off north-eastern Australia. It lies approximately north-northwest of Cairns in Queensland, about east-north-east of Cape Grenville on ...

—on the outer edge of the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

—at the end of August and thence arriving at Cape York, at the tip of Australia's Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest unspoiled wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth’s last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupación ...

.

Over the following three months, from September to November 1874, the expedition visited several islands and island groups while sailing from Cape York to China and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

(then a British colony). The first part of the route passed north and west over the Arafura Sea

The Arafura Sea (or Arafuru Sea) lies west of the Pacific Ocean, overlying the continental shelf between Australia and Western New Guinea (also called Papua), which is the Indonesian part of the Island of New Guinea.

Geography

The Arafura Sea is ...

, with New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

to the north-east and the Australian mainland to the south-west. The first islands visited were the Aru Islands

The Aru Islands Regency ( id, Kabupaten Kepulauan Aru) is a group of about 95 low-lying islands in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia. It also forms a regency of Maluku Province, with a land area of . At the 2011 Census the Regency had a ...

, followed by the nearby Kai Islands

The Kai Islands (also Kei Islands) of Indonesia are a group of islands in the southeastern part of the Maluku Islands, located in the province of Maluku. The Moluccas have been known as the Spice Islands due to regionally specific plants such ...

. The ship then crossed the Banda Sea

The Banda Sea ( id, Laut Banda, pt, Mar de Banda, tet, Tasi Banda) is one of four seas that surround the Maluku Islands of Indonesia, connected to the Pacific Ocean, but surrounded by hundreds of islands, including Timor, as well as the Halma ...

touching at the Banda Islands

The Banda Islands ( id, Kepulauan Banda) are a volcanic group of ten small volcanic islands in the Banda Sea, about south of Seram Island and about east of Java, and constitute an administrative district (''kecamatan'') within the Central ...

, to reach Amboina (Ambon Island

Ambon Island is part of the Maluku Islands of Indonesia. The island has an area of and is mountainous, well watered, and fertile. Ambon Island consists of two territories: the city of Ambon, Maluku, Ambon to the south and various districts ('' ...

) in October 1874, and then continuing to Ternate Island

Ternate is a List of regencies and cities of Indonesia, city in the Indonesian province of North Maluku and an island in the Maluku Islands. It was the ''de facto'' provincial capital of North Maluku before Sofifi on the nearby coast of Halmahera b ...

. At the time, all these islands were part of Netherlands East-Indies and are since 1949 part of Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

.

From Ternate, the route went north-westward towards the Philippines, passing east of Celebes (Sulawesi

Sulawesi (), also known as Celebes (), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the world's eleventh-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Mindanao and the Sulu Ar ...

) into the Celebes Sea

The Celebes Sea, (; ms, Laut Sulawesi, id, Laut Sulawesi, fil, Dagat Selebes) or Sulawesi Sea, of the western Pacific Ocean is bordered on the north by the Sulu Archipelago and Sulu Sea and Mindanao Island of the Philippines, on the east b ...

. The expedition called at Samboangan ( Zamboanga) on Mindanao, and then Iloilo

Iloilo (), officially the Province of Iloilo ( hil, Kapuoran sang Iloilo; krj, Kapuoran kang Iloilo; tl, Lalawigan ng Iloilo), is a province in the Philippines located in the Western Visayas region. Its capital is the City of Iloilo, the ...

on the island of Panay, before navigating within the interior of the archipelago en route to the bay and harbour of Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

on the island of Luzon. The crossing north-westward from Manila to Hong Kong took place in November 1874.

After several weeks in Hong Kong, the expedition departed in early January 1875 to retrace their route south-east towards New Guinea. The first stop on this outward leg of the journey was Manila. From there, they continued on to Samboangan, but took a different route through the interior of the Philippines, this time touching at the island of Zebu

The zebu (; ''Bos indicus'' or ''Bos taurus indicus''), sometimes known in the plural as indicine cattle or humped cattle, is a species or subspecies of domestic cattle originating in the Indian sub-continent. Zebu are characterised by a fatty ...

. From Samboangan the ship diverged from the inward route, this time passing south of Mindanao—in early-February 1875.

''Challenger'' then headed east into the open sea, before turning to the south-east and making landfall at Humboldt Bay (now Yos Sudarso Bay

Yos Sudarso Bay ( id, Teluk Yos Sudarso), known as Humboldt Bay from 1827 to 1968, is a small bay on the north coast of New Guinea, about 50 kilometers west of the border between Indonesia's province of Papua and the country of Papua New Guinea. ...

) on the north coast of New Guinea. By March 1875, the expedition had reached the Admiralty Islands

The Admiralty Islands are an archipelago group of 18 islands in the Bismarck Archipelago, to the north of New Guinea in the South Pacific Ocean. These are also sometimes called the Manus Islands, after the largest island.

These rainforest-co ...

north-east of New Guinea. The final stage of the voyage on this side of the Pacific was a long journey across the open ocean to the north, passing mostly west of the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

and the Mariana Islands, reaching port in Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

, Japan, in April 1875.

''Challenger'' departed Japan in mid-June 1875, heading east across the Pacific to a point due north of the

''Challenger'' departed Japan in mid-June 1875, heading east across the Pacific to a point due north of the Sandwich Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Ku ...

(Hawaii), and then turning south, making landfall at the end of July at Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

on the Hawaiian island of Oahu

Oahu () (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Oʻahu'' ()), also known as "The Gathering place#Island of Oʻahu as The Gathering Place, Gathering Place", is the third-largest of the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to roughly one million people—over t ...

. A couple of weeks later, in mid-August, the ship departed south-eastward, anchoring at Hilo Bay

Hilo Bay is a large bay located on the eastern coast of the island of Hawaii.

Description

The modern town of Hilo, Hawaii overlooks Hilo Bay, located at .

North of the bay runs the Hamakua Coast on the slopes of Mauna Kea, and south of the ba ...

off Hawaii's Big Island, before continuing to the south and reaching Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

in mid-September.

The expedition left Tahiti in early October, swinging to the west and south of the Tubuai Islands

The Austral Islands (french: Îles Australes, officially ''Archipel des Australes;'' ty, Tuha'a Pae) are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas country of the French Republic in the South Pacific. Geographically, ...

and then heading to the south-east before turning east towards the South American coast. The route touched at the Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands ( es, Archipiélago Juan Fernández) are a sparsely inhabited series of islands in the South Pacific Ocean reliant on tourism and fishing. Situated off the coast of Chile, they are composed of three main volcanic i ...

in mid-November 1875, with ''Challenger'' reaching the port of Valparaiso in Chile a few days later. The next stage of the journey commenced the following month, with the route taking the ship south-westward back out into the Pacific, past the Juan Fernández Islands, before turning to the south-east and back towards South America, reaching Port Otway in the Gulf of Penas The Gulf of Penas (''Golfo de Penas'' in Spanish, meaning "gulf of distress") is a body of water located south of the Taitao Peninsula, Chile.

Geography

It is open to the westerly storms of the Pacific Ocean, but it affords entrance to several nat ...

on 31 December 1875.

Most of January 1876 was spent navigating around the southern tip of South America, surveying and touching at many of the bays and islands of the Patagonian archipelago, the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

, and Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

. Locations visited here include Hale Cove, Gray Harbour, Port Grappler, Tom Bay, all in the vicinity of Wellington Island; Puerta Bueno, near Hanover Island

Hanover Island (Spanish: ''Isla Hanover'') is an island in the Magallanes Region. It is separated from the Chatham Island by the Esteban Channel, Guías Narrows and Inocentes Channel.

Literature

In popular fiction, a fictionalized version of ...

; Isthmus Bay, near the Queen Adelaide Archipelago

Queen Adelaide Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago Reina Adelaida) is an island group in Zona Austral, the extreme south of Chile. It belongs to the Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena Region.

The major islands in the group are Pacheco Island, Contrer ...

; and Port Churruca, near Santa Ines Island.

The final stops, before heading out into the Atlantic, were Port Famine, Sandy Point, and Elizabeth Island. ''Challenger'' reached the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

towards the end of January, calling at Port Stanley

Stanley (; also known as Port Stanley) is the capital city of the Falkland Islands. It is located on the island of East Falkland, on a north-facing slope in one of the wettest parts of the islands. At the 2016 census, the city had a popula ...

and then continuing northward, reaching Montevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

in Uruguay in mid-February 1876. The ship left Montevideo at the end of February, heading first due east and then due north, arriving at Ascension Island at the end of March 1876.

The period from early- to mid-April was spent sailing from Ascension Island to the Cape Verde Islands. From here, the route taken in late April and early May 1876 was a westward loop to the north out into the mid-Atlantic, eventually turning due east towards Europe to touch land at Vigo

Vigo ( , , , ) is a city and Municipalities in Spain, municipality in the province of Pontevedra, within the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest of the Iberian Penins ...

in Spain towards the end of May. The final stage of the voyage took the ship and its crew north-eastward from Vigo, skirting the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

to make landfall in England. ''Challenger'' returned to Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, on 24 May 1876, having spent 713 days out of the intervening 1,250 at sea.

Scientific objectives

TheRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

stated the voyage's scientific goals were:

# To investigate the physical conditions of the deep sea in the great ocean basins—as far as the neighborhood of the Great Southern Ice Barrier—in regard to depth, temperature, circulation, specific gravity

Relative density, or specific gravity, is the ratio of the density (mass of a unit volume) of a substance to the density of a given reference material. Specific gravity for liquids is nearly always measured with respect to water (molecule), wa ...

and penetration of light.

# To determine the chemical composition of seawater at various depths from the surface to the bottom, the organic matter in solution and the particles in suspension.

# To ascertain the physical and chemical character of deep-sea deposits and the sources of these deposits.

# To investigate the distribution of organic life at different depths and on the deep seafloor.

One of the goals of the physical measurements for HMS Challenger was to be able to verify the hypothesis put forward by Carpenter on the link between temperature mapping and global ocean circulation in order to provide some answers on the phenomena involved in the major oceanic mixing. This study is a continuation of the preliminary exploratory missions of

One of the goals of the physical measurements for HMS Challenger was to be able to verify the hypothesis put forward by Carpenter on the link between temperature mapping and global ocean circulation in order to provide some answers on the phenomena involved in the major oceanic mixing. This study is a continuation of the preliminary exploratory missions of HMS Lightning (1823)

HMS ''Lightning'', launched in 1823, was a paddle steamer, one of the first steam-powered ships on the Navy List. She served initially as a packet ship, but was later converted into an oceanographic survey vessel.

In 1835 ''Lightning'' was su ...

and HMS Porcupine (1844)

HMS ''Porcupine'' was a Royal Navy 3-gun wooden paddle steamer. It was built in Deptford Dockyard in 1844 and served as a survey ship. It was first employed in the survey of the Thames Estuary by Captain Frederick Bullock.

In 1847, in common w ...

. These results are important for Carpenter because his explanation differed from that of another renowned oceanographer at the time, the American Matthew Fontaine Maury

Matthew Fontaine Maury (January 14, 1806February 1, 1873) was an American oceanographer and naval officer, serving the United States and then joining the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

He was nicknamed "Pathfinder of the Seas" and i ...

. All these results of physical measurements were synthesized by John James Wild

John James Wild (born Jean Jacques Wild; 1824 – 3 June 1900) was a Swiss linguist, oceanographer and a natural history illustrator and lithographer, whose images were noted for their precision and clarity. He participated in the Challenger exped ...

(i.e. the expedition's secretary-artist) in his doctoral thesis at the University of Zurich.

A second important issue concerning the collection of different kinds of physical data on the ocean floor was the laying of submarine telegraph cables. Many transoceanic cables were being laid in the 1860s and 1870s and their efficient laying and operation were matters of great strategic and commercial importance.

At each of the 360 stations the crew measured the bottom depth, temperature at different depths, observed weather and surface ocean conditions, and collected seafloor, water, and biota samples. ''Challenger'' crew used methods that were developed in prior small-scale expeditions to make observations. To measure depth, they would lower a line with a weight attached to it until it reached the sea floor. The line was marked in intervals with flags denoting depth. Because of this, the depth measurements from ''Challenger'' were, at best, accurate to the nearest demarcation. The sinker often had a small container attached to it that would allow for the collection of bottom sediment samples.

The crew used a variety of dredges and trawl

Trawling is a method of fishing that involves pulling a fishing net through the water behind one or more boats. The net used for trawling is called a trawl. This principle requires netting bags which are towed through water to catch different speci ...

s to collect biological samples. The dredges consisted of metal nets attached to a wooden plank and dragged across the sea floor. Mop heads attached to the wooden plank would sweep across the sea floor and release organisms from the ocean bottom to be caught in the nets. Trawls were large metal nets towed behind the ship to collect organisms at different depths of water. Upon the retrieval of a dredge or trawl, ''Challenger'' crew would sort, rinse, and store the specimens for examination upon return. The specimens were often preserved in either brine or alcohol.

The primary thermometer used throughout the ''Challenger'' expedition was the Miller–Casella thermometer, which contained two markers within a curved mercury tube to record the maximum and minimum temperature through which the instrument traveled. Several of these thermometers would be lowered at various depths for recording. However, this design assumed that the water closer to the surface of the ocean was always warmer than that below. During the voyage, ''Challenger''s crew tested the reversing thermometer

Unlike most conventional mercury (element), mercury thermometers, a reversing thermometer is able to record a given temperature to be viewed at a later time. If the thermometer is flipped upside down, the current temperature will be shown until it ...

, which could measure temperature at specified depths. Afterwards, this type of thermometer was used extensively until the second half of the 20th century. After the return of the Challenger, C.W. Thomson asked Peter Tait (physicist)

Peter Guthrie Tait FRSE (28 April 1831 – 4 July 1901) was a Scottish mathematical physicist and early pioneer in thermodynamics. He is best known for the mathematical physics textbook '' Treatise on Natural Philosophy'', which he co-wrote w ...

to solve a thorny and important question: to evaluate the error in the measurement of the temperature of deep waters caused by the high pressures to which the thermometers were subjected. Tait solved this question and continued his work with a more fundamental study on the compressibility of liquids leading to his famous Tait equation

In fluid mechanics, the Tait equation is an equation of state, used to relate liquid density to hydrostatic pressure. The equation was originally published by Peter Guthrie Tait in 1888 in the form

:

\frac = \frac

where P is the hydrostatic ...

. William Dittmar of Glasgow University established the composition of seawater. Murray and Alphonse François Renard

Alphonse Francois Renard (27 September 18429 July 1903), Belgian geologist and petrographer, was born at Ronse, in East Flanders, on 27 September 1842. He was educated for the church of Rome, and from 1866 to 1869 he was superintendent at the ...

mapped oceanic sediments.

Sir Thomson believed, as did many adherents of the then-recent theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variatio ...

, that the deep sea would be home to "living fossils

A living fossil is an extant taxon that cosmetically resembles related species known only from the fossil record. To be considered a living fossil, the fossil species must be old relative to the time of origin of the extant clade. Living fossi ...

" long extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

in shallower waters, examples of " missing links". They believed that the conditions of constant cold temperature, darkness, and lack of currents, waves, or seismic

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

events provided such a stable environment that evolution would slow or stop entirely. Louis Agassiz believed that in the deeps "we should expect to find representatives of earlier geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other E ...

periods." Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

stated that he expected to see "zoological

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and dis ...

antiquities which in the tranquil and little changed depths of the ocean have escaped the causes of destruction at work in the shallows and represent the predominant population of a past age." Nothing of the sort came to pass, however; though a few organisms previously regarded as extinct were found and cataloged among the many new discoveries, the harvest was typical of what might be found in exploring any equivalent extent of new territory. Furthermore, in the process of preserving specimens in alcohol, chemist John Young Buchanan and Sir Thomson realized that he had inadvertently debunked Huxley's prior report of '' Bathybius haeckelii'', an acellular

Non-cellular life, or acellular life is life that exists without a cellular structure for at least part of its life cycle. Historically, most (descriptive) definitions of life postulated that an organism must be composed of one or more cells, ...

protoplasm covering the sea bottoms, which was purported to be the link between non-living matter and living cells. The net effect was a setback for the proponents of evolution.

Challenger Deep

On 23 March 1875, at sample station number 225 located in the southwest Pacific Ocean between Guam and Palau, the crew recorded a sounding of deep, which was confirmed by an additional sounding. As shown by later expeditions using modern equipment, this area represents the southern end of theMariana Trench

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deepest oceanic trench on Earth. It is crescent-shaped and measures about in length and in width. The maximum known ...

and is one of the deepest known places on the ocean floor.

Modern soundings to have since been found near the site of the ''Challenger''s original sounding. ''Challenger''s discovery of this depth was a key finding of the expedition in broadening oceanographic knowledge about the ocean's depth and extent and now bears the vessel's name, the Challenger Deep

The Challenger Deep is the deepest-known point of the seabed of Earth, with a depth of by direct measurement from deep-diving submersibles, remotely operated underwater vehicles and benthic landers, and (sometimes) slightly more by sonar bathym ...

.

The expedition also verified the existence of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge extending from the southern hemisphere to the northern one.

Legacy

Findings from the ''Challenger'' expedition continued to be published until 1895, nineteen years after the completion of its journey, by the Challenger Office, Edinburgh, established for that purpose. The report contained 50 volumes and was over 29,500 pages in length. Specimens brought back by ''Challenger'' were distributed to the world's foremost experts for examination, which greatly increased the expenses and time required to finalize the report. The report and specimens are currently held at the British Natural History Museum and the report has been made available online. Some specimens, many of which were the first discovered of their kind, are still examined by scientists today. A large number of scientists worked on categorising the material brought back from the expedition including the palaeontologist Gabriel Warton Lee.George Albert Boulenger

George Albert Boulenger (19 October 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a Belgian-British zoologist who described and gave scientific names to over 2,000 new animal species, chiefly fish, reptiles, and amphibians. Boulenger was also an active botani ...

, herpetologist at the Natural History Museum, named a species of lizard, '' Saproscincus challengeri'', after ''Challenger''.

Before the ''Challenger'' voyage, oceanography had been mainly speculative. As the first true oceanographic cruise, the ''Challenger'' expedition laid the groundwork for an entire academic and research discipline. "''Challenger''" was applied to such varied phenomena as the Challenger Society for Marine Science, the oceanographic and marine geological survey ship , and the Space Shuttle ''Challenger''.

References

Further reading

General * * * * * Primary reports, accounts, and letters * * * * * * * Secondary literature * * * * * * * * * * Collections and archives * * *External links

* {{Authority control 1870s in Antarctica 1872 in science 1873 in science 1874 in science 1875 in science 1876 in science Expeditions from the United Kingdom Exploration Oceanographic expeditions Royal Society