Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of

autotrophic

An autotroph is an organism that can convert abiotic sources of energy into energy stored in organic compounds, which can be used by other organisms. Autotrophs produce complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) us ...

gram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the Crystal violet, crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelo ...

that can obtain

biological energy via

oxygenic photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metaboli ...

. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (

cyan

Cyan () is the color between blue and green on the visible spectrum of light. It is evoked by light with a predominant wavelength between 500 and 520 nm, between the wavelengths of green and blue.

In the subtractive color system, or CMYK c ...

) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteria's informal

common name

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism (also known as a vernacular name, English name, colloquial name, country name, popular name, or farmer's name) is a name that is based on the normal language of everyday life; and is often con ...

, blue-green algae.

Cyanobacteria are probably the most numerous

taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

to have ever existed on Earth and the first organisms known to have produced

oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

,

having appeared in the middle

Archean eon and apparently originated in a

freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include non-salty mi ...

or

terrestrial environment.

Their

photopigment

Photopigments are unstable pigments that undergo a chemical change when they absorb light. The term is generally applied to the non-protein chromophore Moiety (chemistry), moiety of photosensitive chromoproteins, such as the pigments involved in ph ...

s can absorb the red- and blue-spectrum frequencies of

sunlight

Sunlight is the portion of the electromagnetic radiation which is emitted by the Sun (i.e. solar radiation) and received by the Earth, in particular the visible spectrum, visible light perceptible to the human eye as well as invisible infrare ...

(thus reflecting a greenish color) to split

water molecules into

hydrogen ion

A hydrogen ion is created when a hydrogen atom loses or gains an electron. A positively charged hydrogen ion (or proton) can readily combine with other particles and therefore is only seen isolated when it is in a gaseous state or a nearly particl ...

s and oxygen. The hydrogen ions are used to react with

carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

to produce complex

organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s such as

carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s (a process known as

carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation, or сarbon assimilation, is the Biological process, process by which living organisms convert Total inorganic carbon, inorganic carbon (particularly carbon dioxide, ) to Organic compound, organic compounds. These o ...

), and the oxygen is released as a

byproduct

A by-product or byproduct is a secondary product derived from a production process, manufacturing process or chemical reaction; it is not the primary product or service being produced.

A by-product can be useful and marketable or it can be cons ...

. By continuously producing and releasing oxygen over billions of years, cyanobacteria are thought to have converted the

early Earth's anoxic,

weakly reducing prebiotic atmosphere

The prebiotic atmosphere is the second atmosphere present on Earth before today's biotic, oxygen-rich ''third atmosphere'', and after the ''first atmosphere'' (which was mainly water vapor and simple hydrides) of Earth's formation. The formation ...

, into an

oxidizing

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

one with free gaseous oxygen (which previously would have been immediately removed by various

surface

A surface, as the term is most generally used, is the outermost or uppermost layer of a physical object or space. It is the portion or region of the object that can first be perceived by an observer using the senses of sight and touch, and is ...

reductant

In chemistry, a reducing agent (also known as a reductant, reducer, or electron donor) is a chemical species that "donates" an electron to an (called the , , , or ).

Examples of substances that are common reducing agents include hydrogen, carbon ...

s), resulting in the

Great Oxidation Event

The Great Oxidation Event (GOE) or Great Oxygenation Event, also called the Oxygen Catastrophe, Oxygen Revolution, Oxygen Crisis or Oxygen Holocaust, was a time interval during the Earth's Paleoproterozoic era when the Earth's atmosphere an ...

and the "

rusting of the Earth" during the early

Proterozoic

The Proterozoic ( ) is the third of the four geologic eons of Earth's history, spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8 Mya, and is the longest eon of Earth's geologic time scale. It is preceded by the Archean and followed by the Phanerozo ...

,

dramatically changing the composition of life forms on Earth. The subsequent

adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the p ...

of early

single-celled organisms to survive in oxygenous environments likely had led to

endosymbiosis

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

between

anaerobe

An anaerobic organism or anaerobe is any organism that does not require molecular oxygen for growth. It may react negatively or even die if free oxygen is present. In contrast, an aerobic organism (aerobe) is an organism that requires an oxygenat ...

s and

aerobe

An aerobic organism or aerobe is an organism that can survive and grow in an oxygenated environment. The ability to exhibit aerobic respiration may yield benefits to the aerobic organism, as aerobic respiration yields more energy than anaerobic ...

s, and hence the evolution of

eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s during the

Paleoproterozoic

The Paleoproterozoic Era (also spelled Palaeoproterozoic) is the first of the three sub-divisions ( eras) of the Proterozoic eon, and also the longest era of the Earth's geological history, spanning from (2.5–1.6 Ga). It is further sub ...

.

Cyanobacteria use

photosynthetic pigment

A photosynthetic pigment (accessory pigment; chloroplast pigment; antenna pigment) is a pigment that is present in chloroplasts or photosynthetic bacteria and captures the light energy necessary for photosynthesis.

List of photosynthetic pigmen ...

s such as various forms of

chlorophyll

Chlorophyll is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words (, "pale green") and (, "leaf"). Chlorophyll allows plants to absorb energy ...

,

carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

s,

phycobilin

Phycobilins (from Greek: '' (phykos)'' meaning "alga", and from Latin: ''bilis'' meaning "bile") are light-capturing bilins found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of red algae, glaucophytes and some cryptomonads (though not in green a ...

s to convert the

photonic energy

Photon energy is the energy carried by a single photon. The amount of energy is directly proportional to the photon's electromagnetic frequency and thus, equivalently, is inversely proportional to the wavelength. The higher the photon's frequency, ...

in sunlight to

chemical energy

Chemical energy is the energy of chemical substances that is released when the substances undergo a chemical reaction and transform into other substances. Some examples of storage media of chemical energy include batteries, Schmidt-Rohr, K. (20 ...

. Unlike

heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

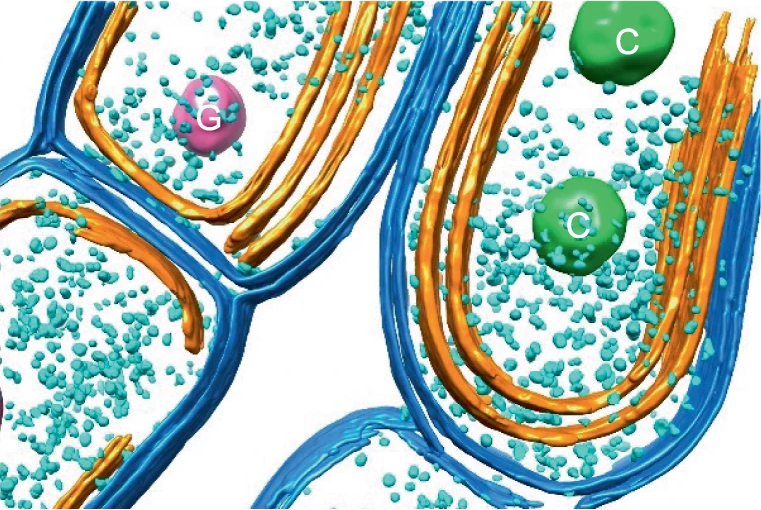

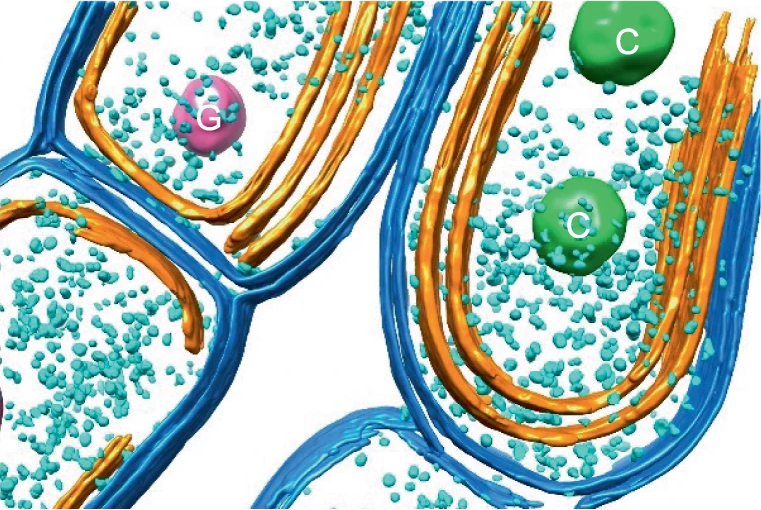

ic prokaryotes, cyanobacteria have

internal membranes. These are flattened sacs called

thylakoids where photosynthesis is performed.

Photoautotrophic eukaryotes such as

red algae

Red algae, or Rhodophyta (, ; ), make up one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae. The Rhodophyta comprises one of the largest Phylum, phyla of algae, containing over 7,000 recognized species within over 900 Genus, genera amidst ongoing taxon ...

,

green algae

The green algae (: green alga) are a group of chlorophyll-containing autotrophic eukaryotes consisting of the phylum Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister group that contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/ Streptophyta. The land plants ...

and

plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s perform photosynthesis in chlorophyllic

organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s that are thought to have their ancestry in cyanobacteria, acquired long ago via endosymbiosis. These

endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

cyanobacteria in eukaryotes then evolved and differentiated into specialized organelles such as

chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

s,

chromoplast

Chromoplasts are plastids, heterogeneous organelles responsible for pigment synthesis and storage in specific Photosynthesis, photosynthetic eukaryotes. It is thought (according to symbiogenesis) that like all other plastids including chloroplast ...

s,

etioplasts, and

leucoplasts, collectively known as

plastid

A plastid is a membrane-bound organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. Plastids are considered to be intracellular endosymbiotic cyanobacteria.

Examples of plastids include chloroplasts ...

s.

Sericytochromatia, the proposed name of the

paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

and most basal group, is the ancestor of both the non-photosynthetic group

Melainabacteria and the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, also called Oxyphotobacteria.

The cyanobacteria ''

Synechocystis'' and ''

Cyanothece'' are important model organisms with potential applications in biotechnology for

bioethanol production, food colorings, as a source of human and animal food, dietary supplements and raw materials. Cyanobacteria produce a range of toxins known as

cyanotoxins that can cause harmful health effects in humans and animals.

Overview

Cyanobacteria are a large and diverse phylum of

photosynthetic

Photosynthesis ( ) is a Biological system, system of biological processes by which Photoautotrophism, photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical ener ...

prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s. They are defined by their unique combination of

pigments

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly solubility, insoluble and reactivity (chemistry), chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored sub ...

and their ability to perform

oxygenic photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metaboli ...

. They often live in

colonial aggregates that can take on a multitude of forms.

Of particular interest are the

filamentous species, which often dominate the upper layers of

microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet or biofilm of microbial colonies, composed of mainly bacteria and/or archaea. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few surviv ...

s found in extreme environments such as

hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a Spring (hydrology), spring produced by the emergence of Geothermal activity, geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow ...

s,

hypersaline water, deserts and the polar regions,

but are also widely distributed in more mundane environments as well.

[ ] They are evolutionarily optimized for environmental conditions of low oxygen. Some species are

nitrogen-fixing

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular dinitrogen () is converted into ammonia (). It occurs both biologically and abiological nitrogen fixation, abiologically in chemical industry, chemical industries. Biological nitrogen ...

and live in a wide variety of moist soils and water, either freely or in a symbiotic relationship with plants or

lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

-forming

fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

(as in the lichen genus ''

Peltigera'').

Cyanobacteria are globally widespread photosynthetic prokaryotes and are major contributors to global

biogeochemical cycle

A biogeochemical cycle, or more generally a cycle of matter, is the movement and transformation of chemical elements and compounds between living organisms, the atmosphere, and the Earth's crust. Major biogeochemical cycles include the carbon cyc ...

s.

They are the only oxygenic photosynthetic prokaryotes, and prosper in diverse and extreme habitats. They are among the oldest organisms on Earth with fossil records dating back at least 2.1 billion years.

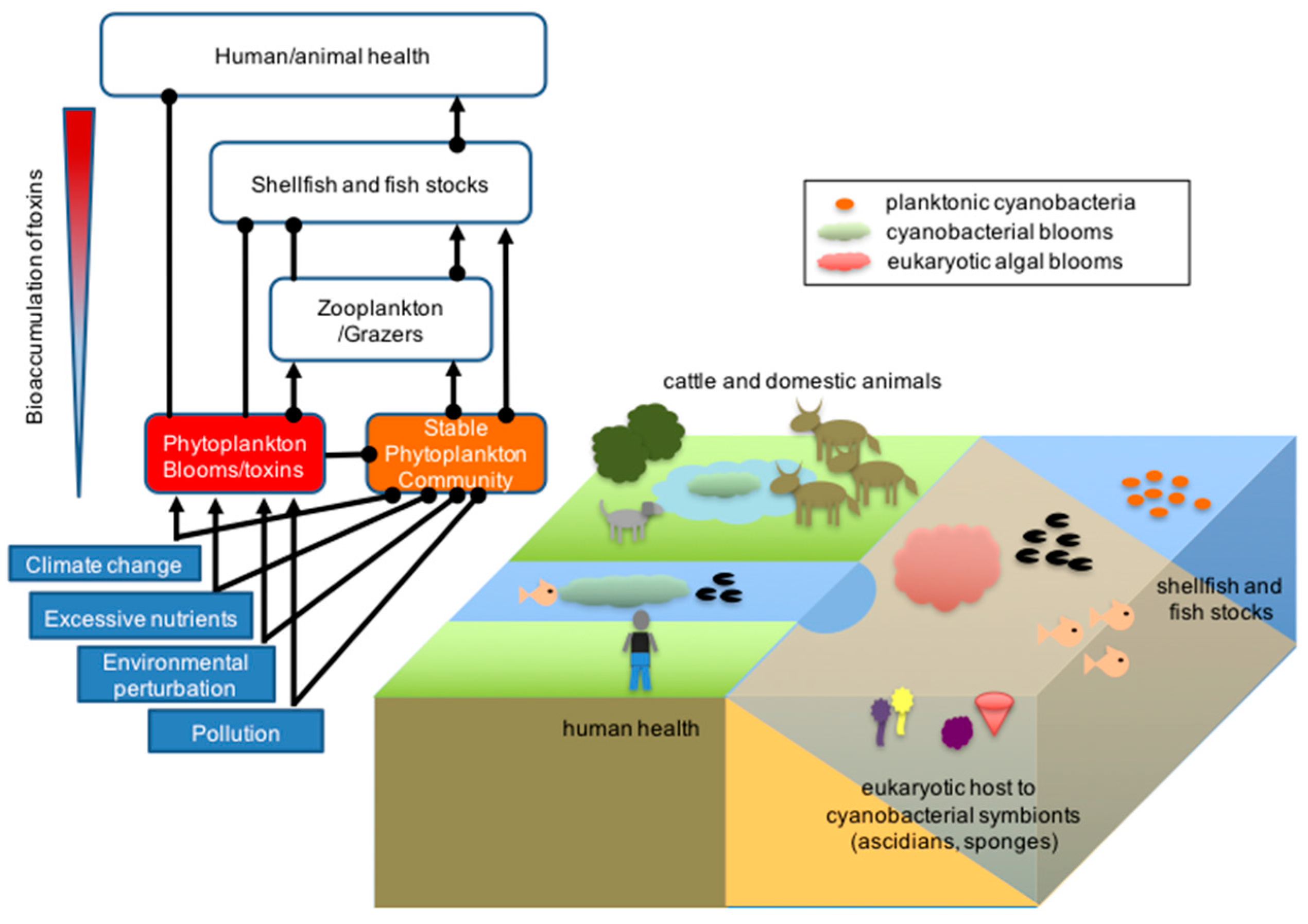

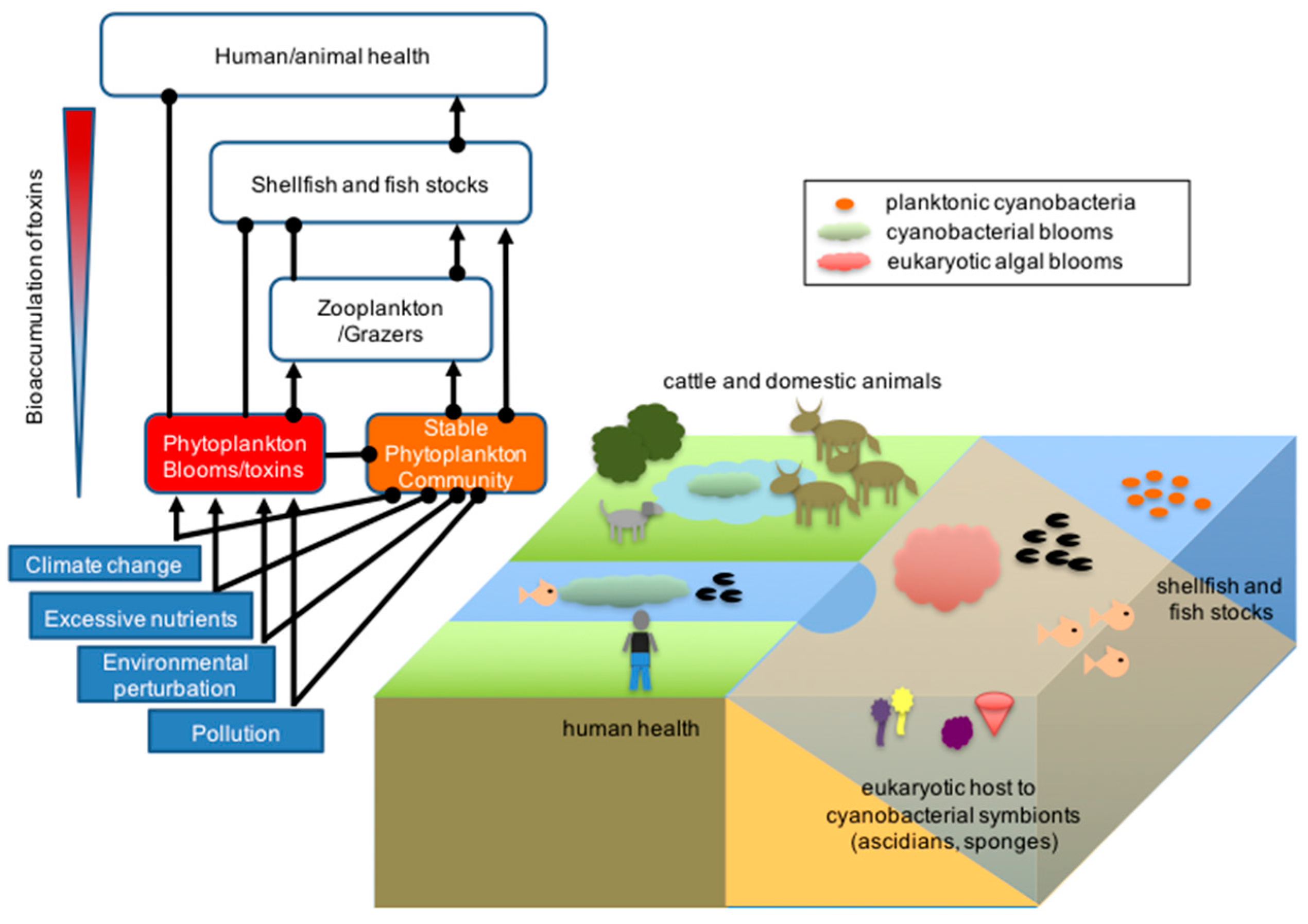

Since then, cyanobacteria have been essential players in the Earth's ecosystems. Planktonic cyanobacteria are a fundamental component of

marine food webs and are major contributors to global

carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

and

nitrogen fluxes. Some cyanobacteria form

harmful algal bloom

A harmful algal bloom (HAB), or excessive algae growth, sometimes called a red tide in marine environments, is an algal bloom that causes negative impacts to other organisms by production of natural algae-produced toxins, water deoxygenation, ...

s causing the disruption of aquatic ecosystem services and intoxication of wildlife and humans by the production of powerful toxins (

cyanotoxin

Cyanotoxins are toxins produced by cyanobacteria (also known as blue-green algae). Cyanobacteria are found almost everywhere, but particularly in lakes and in the ocean where, under high concentration of phosphorus conditions, they reproduce exp ...

s) such as

microcystins,

saxitoxin

Saxitoxin (STX) is a potent neurotoxin and the best-known paralytic shellfish toxin. Ingestion of saxitoxin by humans, usually by consumption of shellfish contaminated by toxic algal blooms, is responsible for the illness known as paralytic she ...

, and

cylindrospermopsin.

Nowadays, cyanobacterial blooms pose a serious threat to aquatic environments and public health, and are increasing in frequency and magnitude globally.

Cyanobacteria are ubiquitous in marine environments and play important roles as

primary producer

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Work ...

s. They are part of the marine

phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

, which currently contributes almost half of the Earth's total primary production. About 25% of the global marine primary production is contributed by cyanobacteria.

Within the cyanobacteria, only a few lineages colonized the open ocean: ''

Crocosphaera'' and relatives,

cyanobacterium UCYN-A, ''

Trichodesmium'', as well as ''

Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosyn ...

'' and ''

Synechococcus''.

From these lineages, nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria are particularly important because they exert a control on

primary productivity

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Works

* ...

and the

export of organic carbon to the deep ocean,

by converting nitrogen gas into ammonium, which is later used to make amino acids and proteins. Marine

picocyanobacteria (''

Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosyn ...

'' and ''

Synechococcus'') numerically dominate most phytoplankton assemblages in modern oceans, contributing importantly to primary productivity.

While some planktonic cyanobacteria are unicellular and free living cells (e.g., ''Crocosphaera'', ''Prochlorococcus'', ''Synechococcus''); others have established symbiotic relationships with

haptophyte algae, such as

coccolithophore

Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single-celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingdom ...

s.

Amongst the filamentous forms, ''Trichodesmium'' are free-living and form aggregates. However, filamentous heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria (e.g., ''

Richelia

''Richelia'' is a genus of Nitrogen fixation, nitrogen-fixing, Filamentous bacteria, filamentous, heterocystous and cyanobacteria. It contains the single species ''Richelia intracellularis''. They exist as both free-living organisms as well as Sy ...

'', ''

Calothrix'') are found in association with

diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s such as ''Hemiaulus'', ''Rhizosolenia'' and ''

Chaetoceros

''Chaetoceros'' is a genus of diatoms in the family Chaetocerotaceae, first described by the German naturalist C. G. Ehrenberg in 1844. Species of this genus are mostly found in marine habitats, but a few species exist in freshwater. It is ...

''.

Marine cyanobacteria include the smallest known photosynthetic organisms. The smallest of all, ''

Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosyn ...

'', is just 0.5 to 0.8 micrometres across. In terms of numbers of individuals, ''Prochlorococcus'' is possibly the most plentiful genus on Earth: a single millilitre of surface seawater can contain 100,000 cells of this genus or more. Worldwide there are estimated to be several

octillion (10

27, a billion billion billion) individuals. ''Prochlorococcus'' is ubiquitous between latitudes 40°N and 40°S, and dominates in the

oligotroph

An oligotroph is an organism that can live in an environment that offers very low levels of nutrients. They may be contrasted with copiotrophs, which prefer nutritionally rich environments. Oligotrophs are characterized by slow growth, low rates o ...

ic (nutrient-poor) regions of the oceans.

The bacterium accounts for about 20% of the oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere.

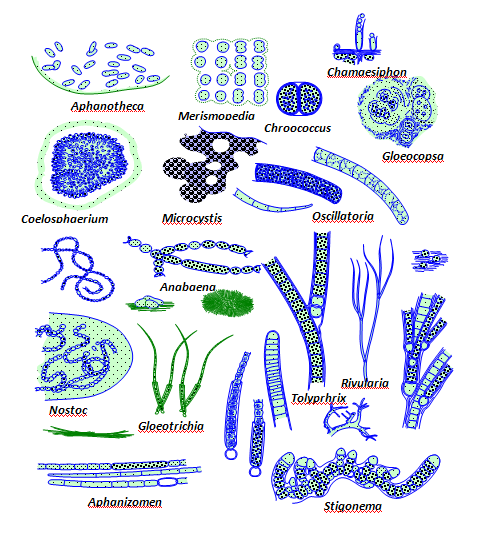

Morphology

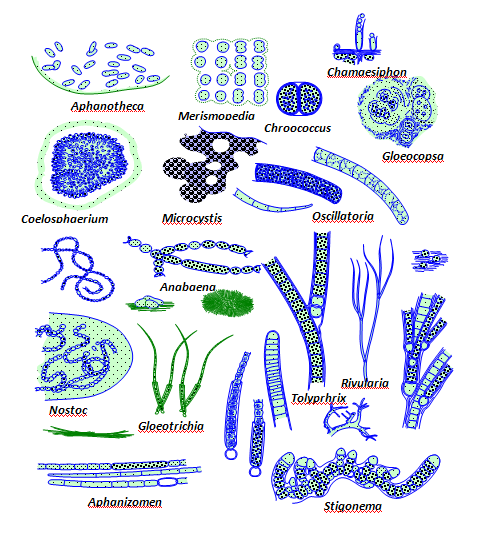

Cyanobacteria are variable in morphology, ranging from

unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

and

filamentous to

colonial forms. Filamentous forms exhibit functional cell differentiation such as

heterocysts (for nitrogen fixation),

akinetes (resting stage cells), and

hormogonia (reproductive, motile filaments). These, together with the intercellular connections they possess, are considered the first signs of multicellularity.

Many cyanobacteria form motile filaments of cells, called

hormogonia, that travel away from the main biomass to bud and form new colonies elsewhere. The cells in a hormogonium are often thinner than in the vegetative state, and the cells on either end of the motile chain may be tapered. To break away from the parent colony, a hormogonium often must tear apart a weaker cell in a filament, called a necridium.

Some filamentous species can differentiate into several different

cell types:

* Vegetative cells – the normal, photosynthetic cells that are formed under favorable growing conditions

*

Akinete

An akinete is an enveloped, thick-walled, non-motile, dormant cell (biology), cell formed by both cyanobacteria and algae. Cyanobacterial akinetes are mainly formed by filamentous, heterocyst-forming members under the order Nostocales and Stigone ...

s – climate-resistant spores that may form when environmental conditions become harsh

* Thick-walled

heterocysts

Heterocysts or heterocytes are specialized nitrogen-fixing cells formed during nitrogen starvation by some filamentous cyanobacteria, such as ''Nostoc'', ''Cylindrospermum'', and '' Anabaena''. They fix nitrogen from dinitrogen (N2) in the air ...

– which contain the enzyme

nitrogenase vital for

nitrogen fixation

Nitrogen fixation is a chemical process by which molecular dinitrogen () is converted into ammonia (). It occurs both biologically and abiological nitrogen fixation, abiologically in chemical industry, chemical industries. Biological nitrogen ...

in an anaerobic environment due to its sensitivity to oxygen.

Each individual cell (each single cyanobacterium) typically has a thick, gelatinous

cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

. They lack

flagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

, but hormogonia of some species can move about by

gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

along surfaces. Many of the multicellular filamentous forms of ''

Oscillatoria

''Oscillatoria'' is a genus of filamentous cyanobacteria. It is often found in freshwater environments. Its name refers to the oscillating motion of its filaments as they slide against each other to position the colony to face a light source. ...

'' are capable of a waving motion; the filament oscillates back and forth. In water columns, some cyanobacteria float by forming

gas vesicles, as in

archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

. These vesicles are not

organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s as such. They are not bounded by

lipid membranes, but by a protein sheath.

Nitrogen fixation

Some cyanobacteria can fix atmospheric

nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

in anaerobic conditions by means of specialized cells called

heterocysts.

Heterocysts may also form under the appropriate environmental conditions (anoxic) when fixed nitrogen is scarce. Heterocyst-forming species are specialized for nitrogen fixation and are able to fix nitrogen gas into

ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

(),

nitrites () or

nitrates

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are soluble in water. An example of an insol ...

(), which can be absorbed by plants and converted to protein and nucleic acids (atmospheric nitrogen is not

bioavailable

In pharmacology, bioavailability is a subcategory of absorption and is the fraction (%) of an administered drug that reaches the systemic circulation.

By definition, when a medication is administered intravenously, its bioavailability is 100%. H ...

to plants, except for those having endosymbiotic

nitrogen-fixing bacteria, especially the family

Fabaceae

Fabaceae () or Leguminosae,[International Code of Nomen ...](_blank)

, among

others). Nitrogen fixation commonly occurs on a cycle of nitrogen fixation during the night because photosynthesis can inhibit nitrogen fixation.

Free-living cyanobacteria are present in the water of

rice paddies, and cyanobacteria can be found growing as

epiphyte

An epiphyte is a plant or plant-like organism that grows on the surface of another plant and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, water (in marine environments) or from debris accumulating around it. The plants on which epiphyt ...

s on the surfaces of the green alga, ''

Chara'', where they may fix nitrogen. Cyanobacteria such as ''

Anabaena'' (a symbiont of the aquatic fern ''

Azolla'') can provide rice plantations with

biofertilizer.

Photosynthesis

Carbon fixation

The

thylakoids of cyanobacteria use the energy of

sunlight

Sunlight is the portion of the electromagnetic radiation which is emitted by the Sun (i.e. solar radiation) and received by the Earth, in particular the visible spectrum, visible light perceptible to the human eye as well as invisible infrare ...

to drive

photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

, a process where the energy of light is used to synthesize

organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s from carbon dioxide. Because they are aquatic organisms, they typically employ several strategies which are collectively known as a " concentrating mechanism" to aid in the acquisition of inorganic carbon ( or

bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial bioche ...

). Among the more specific strategies is the widespread prevalence of the bacterial microcompartments known as

carboxysome

Carboxysomes are bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) consisting of polyhedral protein shells filled with the enzymes ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase ( RuBisCO)—the predominant enzyme in carbon fixation and the rate limiting ...

s,

which co-operate with active transporters of CO

2 and bicarbonate, in order to accumulate bicarbonate into the cytoplasm of the cell. Carboxysomes are

icosahedral structures composed of hexameric shell proteins that assemble into cage-like structures that can be several hundreds of nanometres in diameter. It is believed that these structures tether the -fixing enzyme,

RuBisCO

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, commonly known by the abbreviations RuBisCo, rubisco, RuBPCase, or RuBPco, is an enzyme () involved in the light-independent (or "dark") part of photosynthesis, including the carbon fixation by wh ...

, to the interior of the shell, as well as the enzyme

carbonic anhydrase

The carbonic anhydrases (or carbonate dehydratases) () form a family of enzymes that catalyst, catalyze the interconversion between carbon dioxide and water and the Dissociation (chemistry), dissociated ions of carbonic acid (i.e. bicarbonate a ...

, using

metabolic channeling to enhance the local concentrations and thus increase the efficiency of the RuBisCO enzyme.

Electron transport

In contrast to

purple bacteria and other bacteria performing

anoxygenic photosynthesis

Anoxygenic photosynthesis is a special form of photosynthesis used by some bacteria and archaea, which differs from the better known oxygenic photosynthesis in plants in the reductant used (e.g. hydrogen sulfide instead of water) and the byproduc ...

, thylakoid membranes of cyanobacteria are not continuous with the plasma membrane but are separate compartments.

The photosynthetic machinery is embedded in the

thylakoid

Thylakoids are membrane-bound compartments inside chloroplasts and cyanobacterium, cyanobacteria. They are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Thylakoids consist of a #Membrane, thylakoid membrane surrounding a #Lumen, ...

membranes, with

phycobilisome

Phycobilisomes are light-harvesting antennae that transmit the energy of harvested photons to photosystem II and photosystem I in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of red algae and glaucophytes. They were lost during the evolution of the ...

s acting as

light-harvesting antennae attached to the membrane, giving the green pigmentation observed (with wavelengths from 450 nm to 660 nm) in most cyanobacteria.

While most of the high-energy

electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s derived from water are used by the cyanobacterial cells for their own needs, a fraction of these electrons may be donated to the external environment via

electrogenic activity.

[

]

Respiration

Respiration in cyanobacteria can occur in the thylakoid membrane alongside photosynthesis,

with their photosynthetic

electron transport

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules which transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples this ...

sharing the same compartment as the components of respiratory electron transport. While the goal of photosynthesis is to store energy by building carbohydrates from CO

2, respiration is the reverse of this, with carbohydrates turned back into CO

2 accompanying energy release.

Cyanobacteria appear to separate these two processes with their plasma membrane containing only components of the respiratory chain, while the thylakoid membrane hosts an interlinked respiratory and photosynthetic electron transport chain.

Cyanobacteria use electrons from

succinate dehydrogenase

Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) or succinate-coenzyme Q reductase (SQR) or respiratory complex II is an enzyme complex, found in many bacterial cells and in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes. It is the only enzyme that participates ...

rather than from

NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require N ...

for respiration.

Cyanobacteria only respire during the night (or in the dark) because the facilities used for electron transport are used in reverse for photosynthesis while in the light.

Electron transport chain

Many cyanobacteria are able to reduce nitrogen and carbon dioxide under

aerobic conditions (using different methods to circumvent the deleterious effect of dioxygen on

nitrogenases), a fact that may be responsible for their evolutionary and ecological success. The water-oxidizing photosynthesis is accomplished by coupling the activity of

photosystem

Photosystems are functional and structural units of protein complexes involved in photosynthesis. Together they carry out the primary photochemistry of photosynthesis: the absorption of light and the transfer of energy and electrons. Photosystems ...

(PS) II and I (

Z-scheme). In contrast to

green sulfur bacteria which only use one photosystem, the use of water as an electron donor is energetically demanding, requiring two photosystems.

Attached to the thylakoid membrane,

phycobilisome

Phycobilisomes are light-harvesting antennae that transmit the energy of harvested photons to photosystem II and photosystem I in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of red algae and glaucophytes. They were lost during the evolution of the ...

s act as

light-harvesting antennae for the photosystems. The phycobilisome components (

phycobiliprotein

Phycobiliproteins are water-soluble proteins present in cyanobacteria and certain algae (rhodophytes, cryptomonads, glaucocystophytes). They capture light energy, which is then passed on to chlorophylls during photosynthesis. Phycobiliproteins are ...

s) are responsible for the blue-green pigmentation of most cyanobacteria. The variations on this theme are due mainly to

carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

s and

phycoerythrin

Phycoerythrin (PE) is a red protein-pigment complex from the light-harvesting phycobiliprotein family, present in cyanobacteria, red algae and Cryptomonad, cryptophytes, accessory to the main chlorophyll pigments responsible for photosynthesis.The ...

s that give the cells their red-brownish coloration. In some cyanobacteria, the color of light influences the composition of the phycobilisomes. In green light, the cells accumulate more phycoerythrin, which absorbs green light, whereas in red light they produce more

phycocyanin

Phycocyanin is a pigment-protein complex from the light-harvesting phycobiliprotein family, along with allophycocyanin and phycoerythrin. It is an accessory pigment to chlorophyll. All phycobiliproteins are water-soluble, so they cannot exist ...

which absorbs red. Thus, these bacteria can change from brick-red to bright blue-green depending on whether they are exposed to green light or to red light. This process of "complementary chromatic adaptation" is a way for the cells to maximize the use of available light for photosynthesis.

A few genera lack phycobilisomes and have

chlorophyll b

}

Chlorophyll ''b'' is a form of chlorophyll. Chlorophyll ''b'' helps in photosynthesis by absorbing light energy. It is more soluble than chlorophyll ''a'' in polar solvents because of its carbonyl group. Its color is green, and it primarily ...

instead (''

Prochloron

''Prochloron'' (from the Greek ''pro'' (before) and the Greek ''chloros'' (green) ) is a genus of unicellular oxygenic photosynthetic prokaryotes commonly found as an extracellular symbiont on coral reefs, particularly in didemnid ascidians (sea ...

'', ''

Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosyn ...

'', ''Prochlorothrix''). These were originally grouped together as the

prochlorophytes or chloroxybacteria, but appear to have developed in several different lines of cyanobacteria. For this reason, they are now considered as part of the cyanobacterial group.

Metabolism

In general, photosynthesis in cyanobacteria uses water as an

electron donor

In chemistry, an electron donor is a chemical entity that transfers electrons to another compound. It is a reducing agent that, by virtue of its donating electrons, is itself oxidized in the process. An obsolete definition equated an electron dono ...

and produces

oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

as a byproduct, though some may also use

hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

a process which occurs among other photosynthetic bacteria such as the

purple sulfur bacteria

The purple sulfur bacteria (PSB) are part of a group of Pseudomonadota capable of photosynthesis, collectively referred to as purple bacteria. They are anaerobic or microaerophilic, and are often found in stratified water environments includi ...

.

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

is reduced to form

carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s via the

Calvin cycle

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

. The large amounts of oxygen in the atmosphere are considered to have been first created by the activities of ancient cyanobacteria.

They are often found as

symbiont

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

s with a number of other groups of organisms such as fungi (lichens),

coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

s,

pteridophyte

A pteridophyte is a vascular plant (with xylem and phloem) that reproduces by means of spores. Because pteridophytes produce neither flowers nor seeds, they are sometimes referred to as " cryptogams", meaning that their means of reproduction is ...

s (''

Azolla''),

angiosperm

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (). The term angiosperm is derived from the Greek words (; 'container, vessel') and (; 'seed'), meaning that the seeds are enclosed within a fruit ...

s (''

Gunnera''), etc. The carbon metabolism of cyanobacteria include the incomplete

Krebs cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-CoA oxidation. The e ...

, the

pentose phosphate pathway

The pentose phosphate pathway (also called the phosphogluconate pathway and the hexose monophosphate shunt or HMP shunt) is a metabolic pathway parallel to glycolysis. It generates NADPH and pentoses (five-carbon sugars) as well as ribose 5-ph ...

, and

glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvic acid, pyruvate and, in most organisms, occurs in the liquid part of cells (the cytosol). The Thermodynamic free energy, free energy released in this process is used to form ...

.

There are some groups capable of

heterotrophic

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

growth,

while others are

parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The ent ...

, causing diseases in invertebrates or algae (e.g., the

black band disease).

Ecology

Cyanobacteria can be found in almost every terrestrial and

aquatic habitat –

ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Indian, Southern Ocean ...

s,

fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salt (chemistry), salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include ...

, damp soil, temporarily moistened rocks in

desert

A desert is a landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions create unique biomes and ecosystems. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About one-third of the la ...

s, bare rock and soil, and even

Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

rocks. They can occur as

planktonic

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in water (or air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they pro ...

cells or form

phototrophic biofilms. They are found inside stones and shells (in

endolithic ecosystems). A few are

endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

s in

lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

s, plants, various

protist

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancest ...

s, or

sponges

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and ar ...

and provide energy for the

host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

* Host Island, in the Wilhelm Archipelago, Antarctica

People

* ...

. Some live in the fur of

sloth

Sloths are a Neotropical realm, Neotropical group of xenarthran mammals constituting the suborder Folivora, including the extant Arboreal locomotion, arboreal tree sloths and extinct terrestrial ground sloths. Noted for their slowness of move ...

s, providing a form of

camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

.

Aquatic cyanobacteria are known for their extensive and highly visible

blooms that can form in both

freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include non-salty mi ...

and marine environments. The blooms can have the appearance of blue-green paint or scum. These blooms can be

toxic

Toxicity is the degree to which a chemical substance or a particular mixture of substances can damage an organism. Toxicity can refer to the effect on a whole organism, such as an animal, bacterium, or plant, as well as the effect on a subst ...

, and frequently lead to the closure of recreational waters when spotted.

Marine bacteriophages are significant

parasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The en ...

of unicellular marine cyanobacteria.

Cyanobacterial growth is favoured in ponds and lakes where waters are calm and have little turbulent mixing.

Their lifecycles are disrupted when the water naturally or artificially mixes from churning currents caused by the flowing water of streams or the churning water of fountains. For this reason blooms of cyanobacteria seldom occur in rivers unless the water is flowing slowly. Growth is also favoured at higher temperatures which enable ''

Microcystis'' species to outcompete

diatoms

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

and

green algae

The green algae (: green alga) are a group of chlorophyll-containing autotrophic eukaryotes consisting of the phylum Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister group that contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/ Streptophyta. The land plants ...

, and potentially allow development of toxins.

Based on environmental trends, models and observations suggest cyanobacteria will likely increase their dominance in aquatic environments. This can lead to serious consequences, particularly the contamination of sources of

drinking water

Drinking water or potable water is water that is safe for ingestion, either when drunk directly in liquid form or consumed indirectly through food preparation. It is often (but not always) supplied through taps, in which case it is also calle ...

. Researchers including

Linda Lawton at

Robert Gordon University

Robert Gordon University, commonly called RGU (), is a public university in the city of Aberdeen, Scotland. It became a university in 1992, and originated from an educational institution founded in the 18th century by Robert Gordon (philanthrop ...

, have developed techniques to study these. Cyanobacteria can interfere with

water treatment

Water treatment is any process that improves the quality of water to make it appropriate for a specific end-use. The end use may be drinking, industrial water supply, irrigation, river flow maintenance, water recreation or many other uses, ...

in various ways, primarily by plugging filters (often large beds of sand and similar media) and by producing

cyanotoxin

Cyanotoxins are toxins produced by cyanobacteria (also known as blue-green algae). Cyanobacteria are found almost everywhere, but particularly in lakes and in the ocean where, under high concentration of phosphorus conditions, they reproduce exp ...

s, which have the potential to cause serious illness if consumed. Consequences may also lie within fisheries and waste management practices. Anthropogenic

eutrophication

Eutrophication is a general term describing a process in which nutrients accumulate in a body of water, resulting in an increased growth of organisms that may deplete the oxygen in the water; ie. the process of too many plants growing on the s ...

, rising temperatures, vertical stratification and increased

atmospheric carbon dioxide are contributors to cyanobacteria increasing dominance of aquatic ecosystems.

Cyanobacteria have been found to play an important role in terrestrial habitats and organism communities. It has been widely reported that cyanobacteria

soil crusts help to stabilize soil to prevent

erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as Surface runoff, water flow or wind) that removes soil, Rock (geology), rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust#Crust, Earth's crust and then sediment transport, tran ...

and retain water. An example of a cyanobacterial species that does so is ''Microcoleus vaginatus''. ''M. vaginatus'' stabilizes soil using a

polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

sheath that binds to sand particles and absorbs water. ''M. vaginatus'' also makes a significant contribution to the cohesion of

biological soil crust.

Some of these organisms contribute significantly to global ecology and the

oxygen cycle

The oxygen cycle refers to the various movements of oxygen through the Earth's atmosphere (air), biosphere (flora and fauna), hydrosphere (water bodies and glaciers) and the lithosphere (the Earth's crust). The oxygen cycle demonstrates how free ...

. The tiny marine cyanobacterium ''

Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosyn ...

'' was discovered in 1986 and accounts for more than half of the photosynthesis of the open ocean.

Circadian rhythm

A circadian rhythm (), or circadian cycle, is a natural oscillation that repeats roughly every 24 hours. Circadian rhythms can refer to any process that originates within an organism (i.e., Endogeny (biology), endogenous) and responds to the env ...

s were once thought to only exist in eukaryotic cells but many cyanobacteria display a

bacterial circadian rhythm.

"Cyanobacteria are arguably the most successful group of microorganisms

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen microbial life was suspected from antiquity, with an early attestation in ...

on earth. They are the most genetically diverse; they occupy a broad range of habitats across all latitudes, widespread in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems, and they are found in the most extreme niches such as hot springs, salt works, and hypersaline bays. Photoautotrophic, oxygen-producing cyanobacteria created the conditions in the planet's early atmosphere that directed the evolution of aerobic metabolism and eukaryotic photosynthesis. Cyanobacteria fulfill vital ecological functions in the world's oceans, being important contributors to global carbon and nitrogen budgets." – Stewart and Falconer

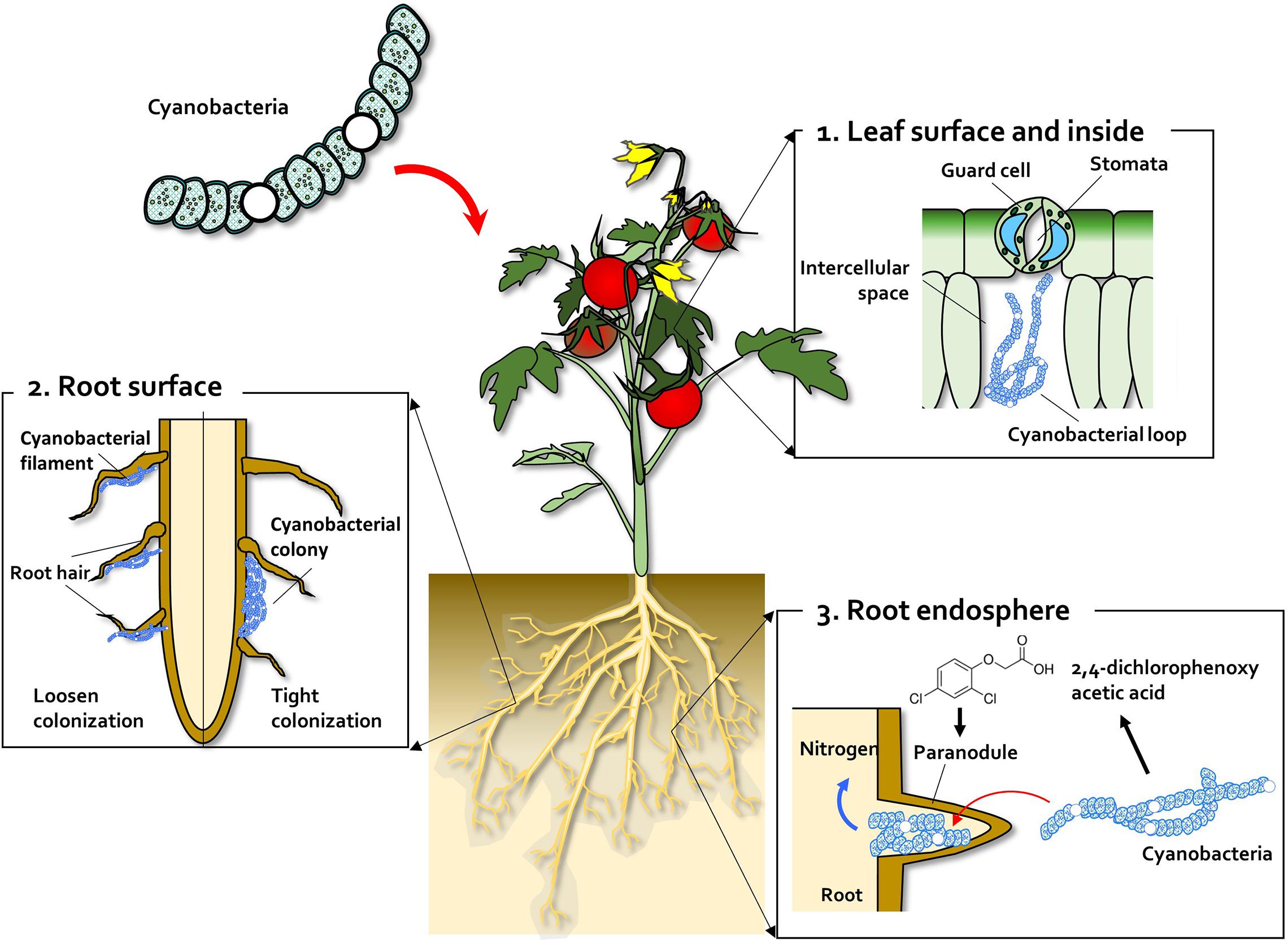

Cyanobionts

Some cyanobacteria, the so-called

cyanobionts (cyanobacterial symbionts), have a

symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

relationship with other organisms, both unicellular and multicellular.

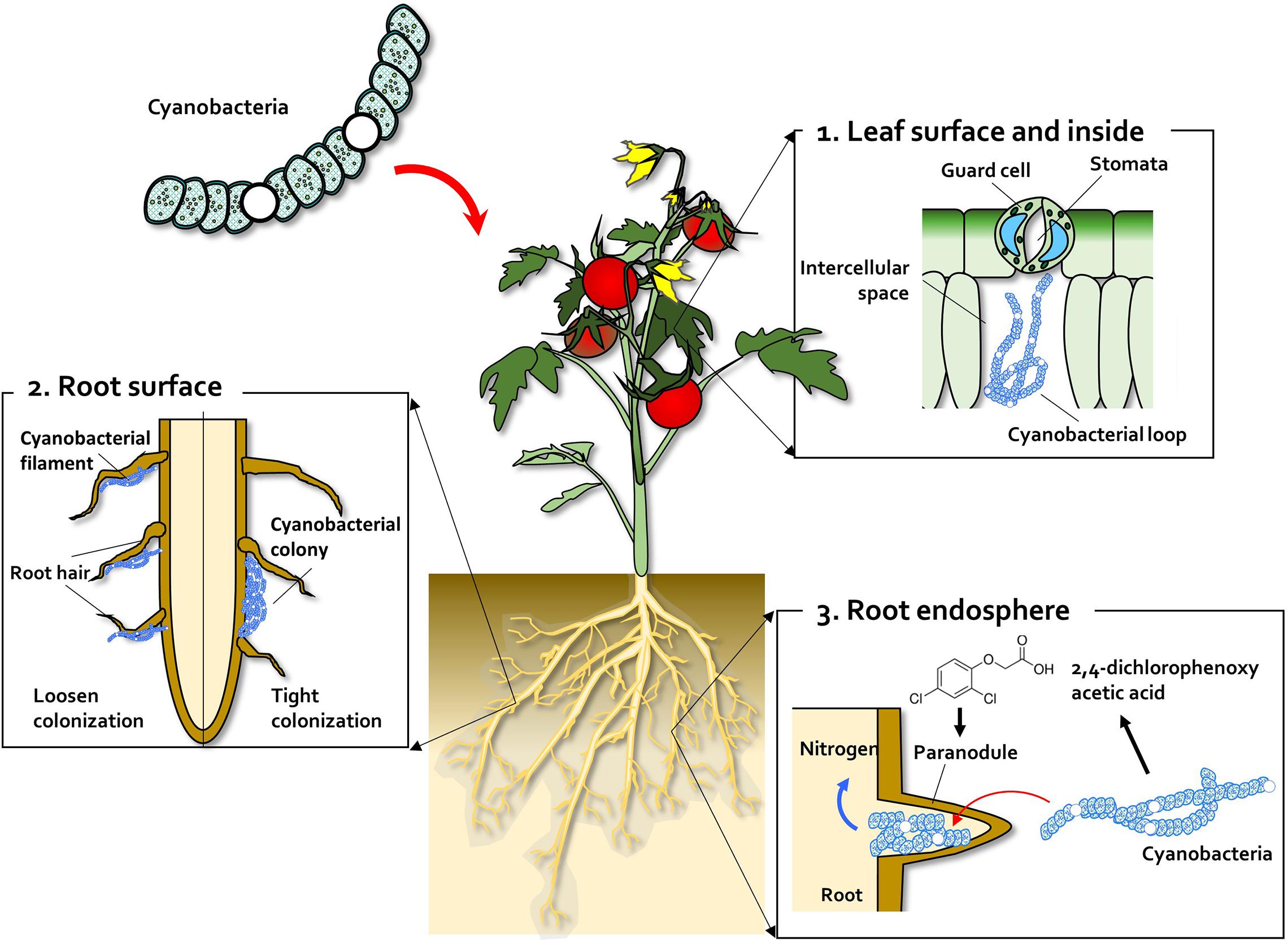

As illustrated on the right, there are many examples of cyanobacteria interacting

symbiotically with

land plant

The embryophytes () are a clade of plants, also known as Embryophyta (Plantae ''sensu strictissimo'') () or land plants. They are the most familiar group of photoautotrophs that make up the vegetation on Earth's dry lands and wetlands. Embryophyt ...

s.

Cyanobacteria can enter the plant through the

stomata

In botany, a stoma (: stomata, from Greek ''στόμα'', "mouth"), also called a stomate (: stomates), is a pore found in the epidermis of leaves, stems, and other organs, that controls the rate of gas exchange between the internal air spa ...

and colonize the intercellular space, forming loops and intracellular coils. ''

Anabaena'' spp. colonize the roots of wheat and cotton plants.

''

Calothrix'' sp. has also been found on the root system of wheat.

Monocot

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, (Lilianae ''sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are flowering plants whose seeds contain only one Embryo#Plant embryos, embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. A monocot taxon has been in use for several decades, but ...

s, such as wheat and rice, have been colonised by ''

Nostoc

''Nostoc'', also known as star jelly, troll's butter, spit of moon, fallen star, witch's butter (not to be confused with the fungi commonly known as witches' butter), and witch's jelly, is the most common genus of cyanobacteria found in a variety ...

'' spp.,

In 1991, Ganther and others isolated diverse

heterocystous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria, including ''Nostoc'', ''Anabaena'' and ''

Cylindrospermum

''Cylindrospermum'' is a genus of filamentous cyanobacteria found in terrestrial and aquatic environments. In terrestrial ecosystems, ''Cylindrospermum'' is found in soils, and in aquatic ones, it commonly grows as part of the periphyton on aqua ...

'', from plant root and soil. Assessment of wheat seedling roots revealed two types of association patterns: loose colonization of root hair by ''Anabaena'' and tight colonization of the root surface within a restricted zone by ''Nostoc''.

The relationships between

cyanobionts (cyanobacterial symbionts) and protistan hosts are particularly noteworthy, as some nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria (

diazotroph

Diazotrophs are organisms capable of nitrogen fixation, i.e. converting the relatively inert diatomic nitrogen (N2) in Earth's atmosphere into bioavailable compound forms such as ammonia. Diazotrophs are typically microorganisms such as bacteria ...

s) play an important role in

primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through ...

, especially in nitrogen-limited

oligotrophic

An oligotroph is an organism that can live in an environment that offers very low levels of nutrients. They may be contrasted with copiotrophs, which prefer nutritionally rich environments. Oligotrophs are characterized by slow growth, low rates o ...

oceans. Cyanobacteria, mostly

pico-

A metric prefix is a unit prefix that precedes a basic unit of measure to indicate a multiple or submultiple of the unit. All metric prefixes used today are decadic. Each prefix has a unique symbol that is prepended to any unit symbol. The pre ...

sized ''

Synechococcus'' and ''

Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosyn ...

'', are ubiquitously distributed and are the most abundant photosynthetic organisms on Earth, accounting for a quarter of all carbon fixed in marine ecosystems.

In contrast to free-living marine cyanobacteria, some cyanobionts are known to be responsible for nitrogen fixation rather than carbon fixation in the host. However, the physiological functions of most cyanobionts remain unknown. Cyanobionts have been found in numerous protist groups, including

dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s,

tintinnids,

radiolarians,

amoebae

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; : amoebas (less commonly, amebas) or amoebae (amebae) ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and r ...

,

diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s, and

haptophytes. Among these cyanobionts, little is known regarding the nature (e.g., genetic diversity, host or cyanobiont specificity, and cyanobiont seasonality) of the symbiosis involved, particularly in relation to dinoflagellate host.

Collective behaviour

Some cyanobacteria – even single-celled ones – show striking collective behaviours and form colonies (or

blooms) that can float on water and have important ecological roles. For instance, billions of years ago, communities of marine

Paleoproterozoic

The Paleoproterozoic Era (also spelled Palaeoproterozoic) is the first of the three sub-divisions ( eras) of the Proterozoic eon, and also the longest era of the Earth's geological history, spanning from (2.5–1.6 Ga). It is further sub ...

cyanobacteria could have helped create the

biosphere

The biosphere (), also called the ecosphere (), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be termed the zone of life on the Earth. The biosphere (which is technically a spherical shell) is virtually a closed system with regard to mat ...

as we know it by burying carbon compounds and allowing the initial build-up of oxygen in the atmosphere. On the other hand,

toxic cyanobacterial blooms are an increasing issue for society, as their toxins can be harmful to animals.

Extreme blooms can also deplete water of oxygen and reduce the penetration of sunlight and visibility, thereby compromising the feeding and mating behaviour of light-reliant species.

As shown in the diagram on the right, bacteria can stay in suspension as individual cells, adhere collectively to surfaces to form biofilms, passively sediment, or flocculate to form suspended aggregates. Cyanobacteria are able to produce sulphated

polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s (yellow haze surrounding clumps of cells) that enable them to form floating aggregates. In 2021, Maeda et al. discovered that oxygen produced by cyanobacteria becomes trapped in the network of polysaccharides and cells, enabling the microorganisms to form buoyant blooms.

It is thought that specific protein fibres known as

pili (represented as lines radiating from the cells) may act as an additional way to link cells to each other or onto surfaces. Some cyanobacteria also use sophisticated intracellular

gas vesicles as floatation aids.

The diagram on the left above shows a proposed model of microbial distribution, spatial organization, carbon and O

2 cycling in clumps and adjacent areas. (a) Clumps contain denser cyanobacterial filaments and heterotrophic microbes. The initial differences in density depend on cyanobacterial motility and can be established over short timescales. Darker blue color outside of the clump indicates higher oxygen concentrations in areas adjacent to clumps. Oxic media increase the reversal frequencies of any filaments that begin to leave the clumps, thereby reducing the net migration away from the clump. This enables the persistence of the initial clumps over short timescales; (b) Spatial coupling between photosynthesis and respiration in clumps. Oxygen produced by cyanobacteria diffuses into the overlying medium or is used for aerobic respiration.

Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) diffuses into the clump from the overlying medium and is also produced within the clump by respiration. In oxic solutions, high O

2 concentrations reduce the efficiency of CO

2 fixation and result in the excretion of glycolate. Under these conditions, clumping can be beneficial to cyanobacteria if it stimulates the retention of carbon and the assimilation of inorganic carbon by cyanobacteria within clumps. This effect appears to promote the accumulation of

particulate organic carbon (cells, sheaths and heterotrophic organisms) in clumps.

It has been unclear why and how cyanobacteria form communities. Aggregation must divert resources away from the core business of making more cyanobacteria, as it generally involves the production of copious quantities of extracellular material. In addition, cells in the centre of dense aggregates can also suffer from both shading and shortage of nutrients.

So, what advantage does this communal life bring for cyanobacteria?

New insights into how cyanobacteria form blooms have come from a 2021 study on the cyanobacterium ''

Synechocystis''. These use a set of genes that regulate the production and export of sulphated

polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s, chains of sugar molecules modified with

sulphate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ...

groups that can often be found in marine algae and animal tissue. Many bacteria generate extracellular polysaccharides, but sulphated ones have only been seen in cyanobacteria. In ''Synechocystis'' these sulphated polysaccharide help the cyanobacterium form buoyant aggregates by trapping oxygen bubbles in the slimy web of cells and polysaccharides.

Previous studies on ''Synechocystis'' have shown

type IV pili, which decorate the surface of cyanobacteria, also play a role in forming blooms.

These retractable and adhesive protein fibres are important for motility, adhesion to substrates and DNA uptake. The formation of blooms may require both type IV pili and Synechan – for example, the pili may help to export the polysaccharide outside the cell. Indeed, the activity of these protein fibres may be connected to the production of extracellular polysaccharides in filamentous cyanobacteria.

A more obvious answer would be that pili help to build the aggregates by binding the cells with each other or with the extracellular polysaccharide. As with other kinds of bacteria, certain components of the pili may allow cyanobacteria from the same species to recognise each other and make initial contacts, which are then stabilised by building a mass of extracellular polysaccharide.

The bubble flotation mechanism identified by Maeda et al. joins a range of known strategies that enable cyanobacteria to control their buoyancy, such as using gas vesicles or accumulating carbohydrate ballasts. Type IV pili on their own could also control the position of marine cyanobacteria in the water column by regulating viscous drag. Extracellular polysaccharide appears to be a multipurpose asset for cyanobacteria, from floatation device to food storage, defence mechanism and mobility aid.

Cellular death

One of the most critical processes determining cyanobacterial eco-physiology is

cellular death. Evidence supports the existence of controlled cellular demise in cyanobacteria, and various forms of cell death have been described as a response to biotic and abiotic stresses. However, cell death research in cyanobacteria is a relatively young field and understanding of the underlying mechanisms and molecular machinery underpinning this fundamental process remains largely elusive.

However, reports on cell death of marine and freshwater cyanobacteria indicate this process has major implications for the ecology of microbial communities/

Different forms of cell demise have been observed in cyanobacteria under several stressful conditions,

and cell death has been suggested to play a key role in developmental processes, such as

akinete

An akinete is an enveloped, thick-walled, non-motile, dormant cell (biology), cell formed by both cyanobacteria and algae. Cyanobacterial akinetes are mainly formed by filamentous, heterocyst-forming members under the order Nostocales and Stigone ...

and

heterocyst differentiation, as well as strategy for population survival.

Cyanophages

Cyanophages are viruses that infect cyanobacteria. Cyanophages can be found in both freshwater and marine environments. Marine and freshwater cyanophages have

icosahedral heads, which contain double-stranded DNA, attached to a tail by connector proteins.

The size of the head and tail vary among species of cyanophages.

Cyanophages, like other

bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

s, rely on

Brownian motion

Brownian motion is the random motion of particles suspended in a medium (a liquid or a gas). The traditional mathematical formulation of Brownian motion is that of the Wiener process, which is often called Brownian motion, even in mathematical ...

to collide with bacteria, and then use receptor binding proteins to recognize cell surface proteins, which leads to adherence. Viruses with contractile tails then rely on receptors found on their tails to recognize highly conserved proteins on the surface of the host cell.

Cyanophages infect a wide range of cyanobacteria and are key regulators of the cyanobacterial populations in aquatic environments, and may aid in the prevention of cyanobacterial blooms in freshwater and marine ecosystems. These blooms can pose a danger to humans and other animals, particularly in

eutrophic freshwater lakes. Infection by these viruses is highly prevalent in cells belonging to ''

Synechococcus'' spp. in marine environments, where up to 5% of cells belonging to marine cyanobacterial cells have been reported to contain mature phage particles.

The first cyanophage,

LPP-1, was discovered in 1963.

Cyanophages are classified within the

bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

families ''

Myoviridae'' (e.g.

AS-1,

N-1), ''

Podoviridae'' (e.g. LPP-1) and ''

Siphoviridae'' (e.g.

S-1).

Movement

It has long been known that

filamentous cyanobacteria perform surface motions, and that these movements result from

type IV pili.

Additionally, ''

Synechococcus'', a marine cyanobacteria, is known to swim at a speed of 25 μm/s by a mechanism different to that of bacterial flagella. Formation of waves on the cyanobacteria surface is thought to push surrounding water backwards.

[ ] Cells are known to be

motile

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently using metabolic energy. This biological concept encompasses movement at various levels, from whole organisms to cells and subcellular components.

Motility is observed in animals, mi ...

by a gliding method and a novel uncharacterized, non-phototactic swimming method that does not involve flagellar motion.

Many species of cyanobacteria are capable of gliding.

Gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

is a form of cell movement that differs from crawling or swimming in that it does not rely on any obvious external organ or change in cell shape and it occurs only in the presence of a

substrate. Gliding in filamentous cyanobacteria appears to be powered by a "slime jet" mechanism, in which the cells extrude a gel that expands quickly as it hydrates providing a propulsion force, although some

unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

cyanobacteria use

type IV pili for gliding.

Cyanobacteria have strict light requirements. Too little light can result in insufficient energy production, and in some species may cause the cells to resort to heterotrophic respiration.

Too much light can inhibit the cells, decrease photosynthesis efficiency and cause damage by bleaching. UV radiation is especially deadly for cyanobacteria, with normal solar levels being significantly detrimental for these microorganisms in some cases.

Filamentous cyanobacteria that live in microbial mats often migrate vertically and horizontally within the mat in order to find an optimal niche that balances their light requirements for photosynthesis against their sensitivity to photodamage. For example, the filamentous cyanobacteria ''

Oscillatoria

''Oscillatoria'' is a genus of filamentous cyanobacteria. It is often found in freshwater environments. Its name refers to the oscillating motion of its filaments as they slide against each other to position the colony to face a light source. ...

'' sp. and ''

Spirulina subsalsa'' found in the hypersaline benthic mats of

Guerrero Negro, Mexico migrate downwards into the lower layers during the day in order to escape the intense sunlight and then rise to the surface at dusk. In contrast, the population of ''Microcoleus chthonoplastes'' found in hypersaline mats in