Cy Oggins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Isaiah Oggins (also known as Ysai or Cy) (July 22, 1898 – 1947) was an American-born

The third of four children, Oggins was born 1898 in the mill town of

The third of four children, Oggins was born 1898 in the mill town of

As of August 26, 1926, when he applied for his U.S. passport, Oggins had joined the Soviet underground and was readying for his first overseas assignment, probably in Germany and France. In April 1928, his wife Nerma applied for her first U.S. passport. The couple departed from New York on May 5, 1928, for a villa in the Zehlendorf district of

As of August 26, 1926, when he applied for his U.S. passport, Oggins had joined the Soviet underground and was readying for his first overseas assignment, probably in Germany and France. In April 1928, his wife Nerma applied for her first U.S. passport. The couple departed from New York on May 5, 1928, for a villa in the Zehlendorf district of

On February 20, 1939, the Soviet

On February 20, 1939, the Soviet

In May 1947, it was decided to murder Oggins because the Soviets feared that if the spy were repatriated to the United States, as the US government had requested, he would defect and reveal Soviet secrets. By mid-summer, Oggins was taken to Laboratory Number One (the "Kamera"), where

In May 1947, it was decided to murder Oggins because the Soviets feared that if the spy were repatriated to the United States, as the US government had requested, he would defect and reveal Soviet secrets. By mid-summer, Oggins was taken to Laboratory Number One (the "Kamera"), where

On April 23, 1924, he married Nerma Berman (1898–1995), a

On April 23, 1924, he married Nerma Berman (1898–1995), a

The Lost Spy: An American in Stalin's Secret Service

{{DEFAULTSORT:Oggins, Isaiah 1898 births 1947 deaths American communists American communists of the Stalin era American defectors to the Soviet Union American people executed by the Soviet Union American people imprisoned in the Soviet Union American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent American spies for the Soviet Union Columbia College (New York) alumni Foreign Gulag detainees Jews executed by the Soviet Union Jewish socialists Norillag detainees People from Willimantic, Connecticut Executed people from Connecticut 20th-century executions of American people

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

and spy for the Soviet secret police

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

. After working in Europe and the Far East, Oggins was arrested, served eight years in the GULAG

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

detention system, and was summarily executed

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes includ ...

on the orders of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

.

Background

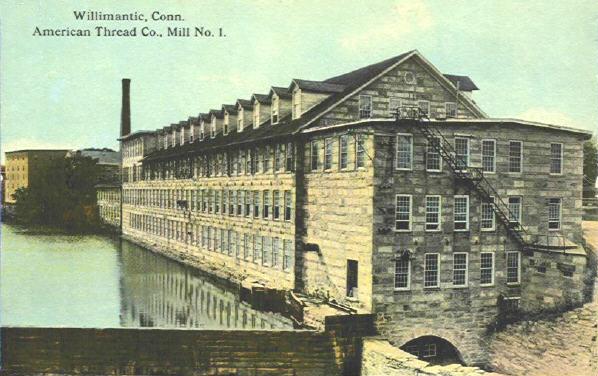

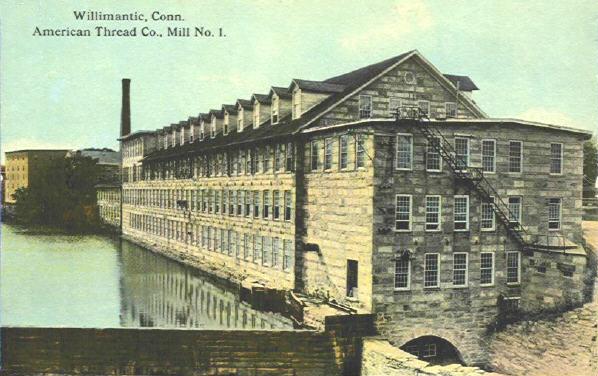

The third of four children, Oggins was born 1898 in the mill town of

The third of four children, Oggins was born 1898 in the mill town of Willimantic, Connecticut

Willimantic is a city located in the town of Windham in Windham County, Connecticut, United States. It is a former Census-designated place and borough, and is currently organized as one of two tax districts within the Town of Windham. Known as ...

, the son of Simon Melamdovich (who changed his name to "Oggins" in America) and his wife Rena, both Jewish immigrants from the Abolnik shtetl

A shtetl or shtetel (; yi, שטעטל, translit=shtetl (singular); שטעטלעך, romanized: ''shtetlekh'' (plural)) is a Yiddish term for the small towns with predominantly Ashkenazi Jewish populations which existed in Eastern Europe before ...

near Kovno (Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Tra ...

), Lithuania. Oggins's parents arrived in New York in 1888. They had three other children.

Oggins entered Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manha ...

in February 1917 under current Jewish quota

A Jewish quota was a discriminatory racial quota designed to limit or deny access for Jews to various institutions. Such quotas were widespread in the 19th and 20th centuries in developed countries and frequently present in higher education, o ...

policies. Classmates included publishers Bennet Cerf

Bennett Alfred Cerf (May 25, 1898 – August 27, 1971) was an American writer, publisher, and co-founder of the American publishing firm Random House. Cerf was also known for his own compilations of jokes and puns, for regular personal appearanc ...

, Donald Klopfer

Donald Simon Klopfer (January 23, 1902 – May 30, 1986) was an American publisher, one of the founders of American publishing firm Random House, along with Bennett Cerf. Klopfer was the quiet inside businessman to Cerf's quite-visible and gregari ...

, and Richard Simon; historian Matthew Josephson

Matthew Josephson (February 15, 1899 – March 13, 1978) was an American journalist and author of works on nineteenth-century French literature and American political and business history of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Josephson popu ...

; novelist Louis Bromfield

Louis Bromfield (December 27, 1896 – March 18, 1956) was an American writer and conservationist. A bestselling novelist in the 1920s, he reinvented himself as a farmer in the late 1930s and became one of the earliest proponents of sustainab ...

, critic Kenneth Burke

Kenneth Duva Burke (May 5, 1897 – November 19, 1993) was an American literary theorist, as well as poet, essayist, and novelist, who wrote on 20th-century philosophy, aesthetics, criticism, and rhetorical theory. As a literary theorist, Bur ...

, and author William Slater Brown

William Slater Brown (November 13, 1896 – June 22, 1997) was an American novelist, biographer, and translator of French literature. Most notably, he was a friend of the poet E. E. Cummings and is best known as the character "B." in Cummi ...

. Professors included John Erskine, George Odell, Robert Livingston Schuyler, and Charles A. Beard

Charles Austin Beard (1874–1948) was an American historian and professor, who wrote primarily during the first half of the 20th century. A history professor at Columbia University, Beard's influence is primarily due to his publications in the f ...

. After receiving his B.A. in history, he began a doctorate in history while working at history reader there, then in a night school in the New York Public School system.

Career

In 1923, Oggins became aCommunist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

by joining the Workers Party of America

The Workers Party of America (WPA) was the name of the legal party organization used by the Communist Party USA from the last days of 1921 until the middle of 1929.

Background

As a legal political party, the Workers Party accepted affiliation fro ...

. The same year, he changed jobs to work for Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Univer ...

as a researcher.

Soviet underground espionage

Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

, Germany. They reported to Ignace Reiss

Ignace Reiss (1899 – 4 September 1937) – also known as "Ignace Poretsky,"

"Ignatz Reiss,"

"Ludwig,"

"Ludwik", "Hans Eberhardt,"

"Steff Brandt,"

Nathan Poreckij,

and "Walter Scott (an officer of the U.S. military intelligence)" ...

. Their job was to maintain a low profile and inhabit their residence, so that other Soviet agents could periodically use it as a safe house for various espionage related activities. To accomplish this mission, Cy and Nerma had to avoid any appearance of being interested in Communist politics; they had to avoid even reading Communist newspapers. Friend Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook (December 20, 1902 – July 12, 1989) was an American philosopher of pragmatism known for his contributions to the philosophy of history, the philosophy of education, political theory, and ethics. After embracing communism in his you ...

spotted Oggins in the Gendarmenmarkt

The Gendarmenmarkt ( en, Gut Market) is a square in Berlin and the site of an architectural ensemble including the Berlin concert hall and the French and German Churches. In the centre of the square stands a monumental statue of poet Fri ...

, as described in his autobiography ''Out of Step'' (1984). Oggins had to resist the temptation to have meetings with his old friend, although he did not always resist this temptation fully.

The Ogginses moved from Berlin to Paris in the Spring of 1930. In Neuilly-sur-Seine

Neuilly-sur-Seine (; literally 'Neuilly on Seine'), also known simply as Neuilly, is a commune in the department of Hauts-de-Seine in France, just west of Paris. Immediately adjacent to the city, the area is composed of mostly select residentia ...

, they watched White Russians, Trotskyites

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a re ...

including Trotsky's Paris-based son, Lev Sedov

Lev Lvovich Sedov (russian: Лев Львович Седов, also known as Leon Sedov; 24 February 1906 – 16 February 1938) was the first son of the Russian communist leader Leon Trotsky and his second wife Natalia Sedova. He was born when his ...

, and the family of Michael Feodorovich Romanov. After exposure of '' l'affaire Switz'' (1933–1934, involving Robert Gordon Switz

Robert Gordon Switz (born 1904) was a "wealthy American who converted to communism"

and served as spy for Soviet Military Intelligence ("GRU").

Background

Robert Gordon Switz was born in 1904 in East Orange, New Jersey, the son of Theodore Sw ...

, Lydia Stahl

Lydia Stahl (1885-?) was a Russian-born secret agent who worked for Soviet Military Intelligence in New York and Paris in the 1920s and 1930s.

Early life

Lydia Stahl was born Lydia Chkalova in Rostov-on-Don, Russian Empire, in 1885.

Personal lif ...

, and Arvid Jacobson

Arvid Werner Jacobson (November 12, 1904 – April 1, 1976) was a Finnish-American communist who spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s.

Biography

Jacobson's parents were Finnish immigrants from Lapua, Ostrobotnia. Jacobson was born in Covingto ...

), the Ogginses left Paris (September 1934) and returned to the States with their young son Robin (b. 1931). After a brief stint in New York, they left for San Francisco. Leaving his wife and child behind, Cy Oggins set off for China in September 1935, where he served through 1937.

In Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

, Oggins reported to Grace and Manny Granich (brother of Mike Gold

Michael Gold (April 12, 1894 – May 14, 1967) was the pen-name of Jewish American writer Itzok Isaac Granich. A lifelong communist, Gold was a novelist and literary critic. His semi-autobiographical novel '' Jews Without Money'' (1930) was a bes ...

). In 1936, he worked in Dairen

Dalian () is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China. Located on th ...

during the Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese in ...

and traveled to Harbin. He reported to Charles Emile Martin (AKA George Wilmer, Lorenz, Laurenz, Dubois—born Matus Steinberg

Matus can be both a given name and surname. Common variants include Matúš, Matuš, and Matůš. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

;Matus

* Matus Bisnovat (1905–1977), Soviet aircraft and missile designer

* Matus Tomko (born 1978 ...

of Belgorod-Dnestrovsky

Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi ( uk, Бі́лгород-Дністро́вський, Bílhorod-Dnistróvskyy, ; ro, Cetatea Albă), historically known as Akkerman ( tr, Akkerman) or #Nomenclature, under different names, is a List of cities in Ukraine ...

) and wife Elsa Marie Martin (AKA Joanna Wilmer, Lora, Laura). (Martin later served in the Red Orchestra, spying on Nazi Germany.) By October 1937, the Martins and Ogginses fled separately after Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

attacked Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym "Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East ( Outer ...

in July.

Oggins rejoined his wife and son in Paris in February 1938, only to leave again in May. Nerma Berman Oggins left Paris with their son in September 1939 and returned to New York. (The State Department believes he was stationed in France in 1937–1938.)

GULAG

On February 20, 1939, the Soviet

On February 20, 1939, the Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

arrested Oggins at the Hotel Moskva and took him to the Lubyanka, accusing him of being a traitor. His case received a hearing on January 5, 1940. Ten days later, he received a sentence of eight years.

On the next day, Oggins shipped out to Norillag

Norillag, Norilsk Corrective Labor Camp (russian: Норильлаг, Норильстрой, Норильский ИТЛ) was a gulag labor camp set by Norilsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia and headquartered there. It existed from June 25, 1935 to Aug ...

, where fellow inmates included Jacques Rossi

Jacques Rossi (10 October 1909, Wrocław – 30 June 2004, Paris) was a Polish-French writer and polyglot. Rossi was best known for his books on the Gulag.

Early life

He was born as Franz Xaver Heyman and was the son of architect Martin (Mar ...

. He became known there as "The Professor". Nerma Berman Oggins requested the U.S. Department of State to investigate her husband's disappearance. On April 15, 1942, the US Department of State indicated to the US embassy in Moscow "It is possible that he gginshas been acting for years as an agent of a foreign power or of an international revolutionary organization. Nevertheless it is believed that in view of his American citizenship and of the Soviet agreement in 1933 to inform this Government of the arrest of American citizens, the failure to report his detention should not be ignored." On June 30, 1942, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

had the following telegram sent to the US ambassador in Moscow: Washington, June 30, 1942—11 p.m.On December 8, 1942, Oggins received visits from American diplomats at the

327. Your 538, June 16, 1 p.m. Please take up this case informally with the Soviet authorities and since Oggins is an American citizen request permission for an American Foreign Service Officer to visit him as provided for in the 1933 agreement, or that Oggins be allowed to appear at the Embassy.

Without at this time giving emphasis to the failure of the Soviet authorities, from the standpoint of commitments of the Soviet Government, to notify the Embassy of Oggins’ arrest, you may, however, express some surprise at such failure and may mention that your Government hopes that steps will be taken to prevent failures of a similar nature from taking place in the future.

The Department is concerned as to the disposition made of Oggins’ passport.

Butyrka

Butyrskaya prison ( rus, Бутырская тюрьма, r= Butýrskaya tyurmá), usually known simply as Butyrka ( rus, Бутырка, p=bʊˈtɨrkə), is a prison in the Tverskoy District of central Moscow, Russia. In Imperial Russia it ...

prison in Moscow. By May 1943, the Soviets reneged on his release.

During his time in the GULAG, Oggins' wife and son pled with US Secretary George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S ...

to help gain his release.

Death

In May 1947, it was decided to murder Oggins because the Soviets feared that if the spy were repatriated to the United States, as the US government had requested, he would defect and reveal Soviet secrets. By mid-summer, Oggins was taken to Laboratory Number One (the "Kamera"), where

In May 1947, it was decided to murder Oggins because the Soviets feared that if the spy were repatriated to the United States, as the US government had requested, he would defect and reveal Soviet secrets. By mid-summer, Oggins was taken to Laboratory Number One (the "Kamera"), where Grigory Mairanovsky

Grigory Moiseevich Mairanovsky (russian: Григо́рий Моисе́евич Майрано́вский, 1899, Batumi – 1964) was a Soviet biochemist and poison developer.

Career

Mairanovsky was born to a Jewish family in Batumi in 189 ...

injected him with the poison curare

Curare ( /kʊˈrɑːri/ or /kjʊˈrɑːri/; ''koo-rah-ree'' or ''kyoo-rah-ree'') is a common name for various alkaloid arrow poisons originating from plant extracts. Used as a paralyzing agent by indigenous peoples in Central and Sout ...

, which takes 10–15 minutes to kill. A death certificate claimed Oggins had died of "sclerosis" and had received burial in a Jewish cemetery in Penza

Penza ( rus, Пе́нза, p=ˈpʲɛnzə) is the largest city and administrative center of Penza Oblast, Russia. It is located on the Sura River, southeast of Moscow. As of the 2010 Census, Penza had a population of 517,311, making it the 38th-l ...

.

Aftermath

FBI investigation

AnFBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

investigation into the Oggins affair commenced in March 1943. After the defection of Igor Gouzenko

Igor Sergeyevich Gouzenko (russian: Игорь Сергеевич Гузенко ; January 26, 1919 – June 25, 1982) was a cipher clerk for the Soviet embassy to Canada in Ottawa, Ontario, and a lieutenant of the GRU (Main Intelligence Direc ...

, the name "Oggins" arose again in 1945–1946.

On February 10, 1949, FBI investigators questioned Esther Shemitz

Esther Shemitz (June 25, 1900August 16, 1986), also known as "Esther Chambers" and "Mrs. Whittaker Chambers," was an American painter and illustrator who, as wife of ex-Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers, provided testimony that "helped substantiate" h ...

, wife of Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938) ...

, about the Ogginses, as Esther Chambers and Nerma Oggins had both attended the Rand School

The Rand School of Social Science was formed in 1906 in New York City by adherents of the Socialist Party of America. The school aimed to provide a broad education to workers, imparting a politicizing class-consciousness, and additionally served a ...

and had worked at the ILGWU

The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), whose members were employed in the women's clothing industry, was once one of the largest labor unions in the United States, one of the first U.S. unions to have a primarily female membe ...

and ''The World Tomorrow'' magazine.

Joint Russian–American investigation

In early 1992, the U.S. and Russia formed the U.S.–Russia Joint Commission on POW/MIAs. Overseeing the investigation wasDmitri Volkogonov

Dmitri Antonovich Volkogonov (russian: Дми́трий Анто́нович Волкого́нов; 22 March 1928 – 6 December 1995) was a Soviet and Russian historian and colonel general who was head of the Soviet military's psychological warf ...

. On September 23, 1992, Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

handed an Oggins case dossier to American diplomat Malcolm Toon

Malcolm Toon (July 4, 1916 – February 12, 2009) was an American diplomat who served as a Foreign Service Officer in Moscow in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, during the Cold War, ultimately becoming the ambassador to the Soviet Union.

Life

Toon ...

: Oggins had been liquidated on Stalin's orders.

''The Lost Spy''

In 2008, Andrew Meier, formerly Moscow bureau chief for ''TIME

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, t ...

'' magazine, published a biography of Oggins called ''The Lost Spy''. The book resulted from a decade of investigative research into the mysterious circumstances of Oggins' imprisonment and death. It included documentation from Soviet, American, and Swiss archives

Requests to FSB

Oggins' son has continued to ask for information about his father's death from Soviet successor agencies like the RussianFederal Security Service

The Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (FSB) RF; rus, Федеральная служба безопасности Российской Федерации (ФСБ России), Federal'naya sluzhba bezopasnosti Rossiyskoy Feder ...

(generally known by its Russian acronym "FSB").

Personal life

On April 23, 1924, he married Nerma Berman (1898–1995), a

On April 23, 1924, he married Nerma Berman (1898–1995), a Rand School

The Rand School of Social Science was formed in 1906 in New York City by adherents of the Socialist Party of America. The school aimed to provide a broad education to workers, imparting a politicizing class-consciousness, and additionally served a ...

student and Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

activist, born in the Skapiskis shtetl (also near Kovno). She became secretary of the New York division of the National Defense Committee of the Rand School for Red Scare victims Scott Nearing

Scott Nearing (August 6, 1883 – August 24, 1983) was an American Political radicalism, radical economist, educator, writer, political activist, pacifist, vegetarian and advocate of simple living.

Biography

Early years

Nearing was born in Mor ...

and other professors.

The Oggins had one son, Robin, born 1931.

Nerma Berman Oggins drifted from job to job and lived in the New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

area. She retired in 1965 and lived for a time in the Lower East Side

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets.

Traditionally ...

at the Henry Street Settlement

The Henry Street Settlement is a not-for-profit social service agency in the Lower East Side neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City that provides social services, arts programs and health care services to New Yorkers of all ages. It was founde ...

. She later moved to Vestal, New York

Vestal is a town within Broome County in the Southern Tier of New York, United States, and lies between the Susquehanna River and the Pennsylvania border. As of the 2020 census, the population was 29,110.

Vestal is on the southern border of the ...

to be near her son. She died in Vestal on January 27, 1995.

See also

* The Lost Spy: An American in Stalin's Secret Service *Ignace Reiss

Ignace Reiss (1899 – 4 September 1937) – also known as "Ignace Poretsky,"

"Ignatz Reiss,"

"Ludwig,"

"Ludwik", "Hans Eberhardt,"

"Steff Brandt,"

Nathan Poreckij,

and "Walter Scott (an officer of the U.S. military intelligence)" ...

* Robert Gordon Switz

Robert Gordon Switz (born 1904) was a "wealthy American who converted to communism"

and served as spy for Soviet Military Intelligence ("GRU").

Background

Robert Gordon Switz was born in 1904 in East Orange, New Jersey, the son of Theodore Sw ...

* Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938) ...

* Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook (December 20, 1902 – July 12, 1989) was an American philosopher of pragmatism known for his contributions to the philosophy of history, the philosophy of education, political theory, and ethics. After embracing communism in his you ...

References

External links

The Lost Spy: An American in Stalin's Secret Service

{{DEFAULTSORT:Oggins, Isaiah 1898 births 1947 deaths American communists American communists of the Stalin era American defectors to the Soviet Union American people executed by the Soviet Union American people imprisoned in the Soviet Union American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent American spies for the Soviet Union Columbia College (New York) alumni Foreign Gulag detainees Jews executed by the Soviet Union Jewish socialists Norillag detainees People from Willimantic, Connecticut Executed people from Connecticut 20th-century executions of American people