Culex (Poem) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Appendix Vergiliana'' is a collection of poems traditionally ascribed as being the juvenilia (work written as a juvenile) of

Vergil's Epicureanism in his early poems

in "Vergil, Philodemus, and the Augustans" 2003: "Vergil's authorship of at least some of the poems in the Appendix is nowadays no longer contested. This is especially true of the Culex ... and also of a collection of short epigrams called the Catalepton." Many of the poems in the Appendix were considered works by Virgil in antiquity. However, recent studies suggest that the Appendix contains a diverse collection of minor poems by various authors from the 1st century AD. Scholars are almost unanimous in considering the works of the ''Appendix'' spurious, primarily on grounds of style, metrics, and vocabulary.

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

.Régine ChambertVergil's Epicureanism in his early poems

in "Vergil, Philodemus, and the Augustans" 2003: "Vergil's authorship of at least some of the poems in the Appendix is nowadays no longer contested. This is especially true of the Culex ... and also of a collection of short epigrams called the Catalepton." Many of the poems in the Appendix were considered works by Virgil in antiquity. However, recent studies suggest that the Appendix contains a diverse collection of minor poems by various authors from the 1st century AD. Scholars are almost unanimous in considering the works of the ''Appendix'' spurious, primarily on grounds of style, metrics, and vocabulary.

Composition

The collection most likely formed inLate Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English has ...

. The individual components are older: ancient authors considered the ''Culex'' to be a youthful work of Virgil's and the ''Ciris'' is ascribed to Virgil as early as Donatus' ''Vita.'' Quintilian quotes ''Catalepton'' 2 as the work of Virgil. The ''Elegiae in Maecenatem'' cannot possibly be by Virgil, as Maecenas died eleven years after Virgil in 8 BC. The poems are all probably by different authors, except for the ''Lydia'' and ''Dirae'' which may have a common author, and have been given various, nebulous dates within the 1st century AD. The ''Culex'' and the ''Ciris'' are thought to have been composed under the emperor Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

. Some of the poems may be attempts to pass works off under Virgil's name as pseudepigraphia, such as the ''Catalepton'', while others seem to be independent works that were subsumed into the collection like the ''Ciris'' which is influenced more by the late Republican neoterics than Virgil.

Contents

''Culex'' ("The Gnat")

This is a pastoral epyllion in 414 hexameters which evokes the world of Theocritus and employs epic conventions for comic effect in a parody. The poem opens with an address to the young Octavian, a promise of more poems, an invocation of Apollo, and a prayer for Octavian's success. The poet has apriamel A priamel is a literary and rhetorical device found throughout Western literature and beyond, and consisting of a series of listed alternatives that serve as Foil (literature), foils to the true subject of the poem, which is revealed in a climax. F ...

in which he rejects the Battle of the Gods and Giants and historical epic. It is noon, and a poor but happy shepherd, who lacks the refinements of classical luxury, is tending his flocks when he sees a grove of trees, a ''locus amoenus

''Locus amoenus'' (Latin for "pleasant place") is a literary topos involving an idealized place of safety or comfort. A ''locus amoenus'' is usually a beautiful, shady lawn or open woodland, or a group of idyllic islands, sometimes with conno ...

'', and lies down to rest. The mythical metamorphoses of the trees in the grove are described. As he sleeps, a snake approaches him and is ready to bite when a gnat lands on his eyes. Reflexively killing the gnat he awakes, sees the snake and kills it. That night, the gnat appears to the shepherd in a dream, laments its undeserved fate, and gives a long description of the underworld and the souls of the dead mythological heroes there, allowing it to digress. The gnat especially focuses on the story of Eurydice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the name ...

and the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and ha ...

. The gnat goes on to describe famous Roman heroes and then his audience before Minos to decide his fate. When he awakes, the shepherd constructs a heroon to the gnat in the grove and the poet has a flower-catalogue. The shepherd inscribes it with the inscription "Little gnat, to you deservedly the guard of the flock repays his funeral duty for your gift of life." The ''Culex'' cannot be one of Virgil's ''juvenilia'' because it alludes to the full body of his work; thus, it is usually dated to sometime during the reign of Tiberius. Moreover, Suetonius in his ''Lives of the Poets'' (18) writes, "the Culex... of his (Virgil's) was written when he might have been sixteen years old", so it is therefore possible that the extant version which has come down to us may be a later copy that had been modified. The poem has been variously interpreted as a charming epyllion or as an elaborate allegory in which the shepherd symbolizes Augustus and the gnat Marcellus.

''Ciris'' ("The Sea-Bird")

The ''Ciris'' is anepyllion

A sleeping Theseus.html" ;"title="Ariadne's abandonment by Theseus">Ariadne's abandonment by Theseus is the topic of an elaborate ecphrasis in Catullus 64, the most famous extant epyllion. (Roman copy of a 2nd-century BCE Greek original; :it:Vill ...

in 541 hexameters describing the myth of Nisus, the king of Megara and his daughter Scylla of Megara. The epyllion was a popular style of composition which seems to have developed in the Hellenistic age; surviving examples can be found in Theocritus and Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poetry, Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical h ...

. The poet begins his hundred line prologue by invoking the Muses and Sophia

Sophia means "wisdom" in Greek. It may refer to:

*Sophia (wisdom)

*Sophia (Gnosticism)

*Sophia (given name)

Places

*Niulakita or Sophia, an island of Tuvalu

*Sophia, Georgetown, a ward of Georgetown, Guyana

*Sophia, North Carolina, an unincorpor ...

, despite the fact that he is an Epicurean

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings b ...

, and describes his poem as a gift to Messalla like the robe given to Minerva in the Panathenaia. The poet differentiates the Scylla of his poem from the sea-monster Scylla and describes the monster's birth and metamorphosis. He starts by describing Minos' siege of Megara and the lock of purple hair on the head of Nisus which protected the city. While playing ball, Scylla is shot by Cupid and falls madly in love with Minos. As a prize for Minos, she tries to cut the lock of her father, but her nurse, Carme, asks Scylla why she is upset. After Scylla tells her she is in love with Minos, Carme says that Minos earlier had killed her daughter Britomartis and convinces Scylla to go to bed. In the morning, Scylla tries to talk Nisus into making peace with Minos, and the nurse brews a magical potion, but nothing works and Scylla cuts off the lock. The city falls and Scylla, lamenting Minos' refusal to marry her, is taken prisoner on the Cretan ships which sail around Attica. The poet describes her metamorphosis in detail; by the pitying Amphitrite she is transformed into the ''ciris'' bird, supposedly from the Greek ''keirein'' ("cut"). Jupiter transforms Nisus into a sea-eagle, which pursues the ''ciris'' like Scorpio pursues Orion. Based on composition, the poem must be placed after Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the ...

and before the 2nd century. A Tiberian date seems likely for its composition.

''Copa'' ("The Barmaid")

This poem in 38 elegiac couplets describes the song of the barmaid Syrisca. She describes a lush, pastoral setting and a picnic laid out in the grass and invites an unnamed man to spend time with her, stop thinking about the future, and live for the present.''Moretum'' ("The Pesto")

The ''Moretum'' in 124 hexameter lines describes the preparation by the poor farmer Simylus of a meal. The poem is in the tradition ofHellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

poetry about the poor and their diet and has a precedent in Callimachus' ''Hecale

In Greek mythology, Hecale ( grc-gre, Ἑκάλη ''Hekálē'') was an old woman who offered succor to Theseus on his way to capture the Marathonian Bull.

Mythology

On the way to Marathon to capture the Bull, Theseus sought shelter from a st ...

'' and poems that describe ''theoxeny''. Waking before dawn, he starts the fire, grinds grain as he sings and talks to his African slave Scybale, and starts baking. His garden and its products are described. Simylus fashions from garlic, cheese, and herbs the '' moretum,'' a type of pesto, eats, and goes out to plow. The poem is notable for its use of the phrase " e pluribus unus".

''Dirae'' ("Curses")

This poem in 103 hexameter lines is a series of curses by a dispossessed farmer on the veteran who has usurped his land. The tradition of curse poetry goes back to the works of Archilochus andHipponax

Hipponax ( grc, Ἱππῶναξ; ''gen''. Ἱππώνακτος; fl. late 6th century BC), of Ephesus and later Clazomenae, was an Ancient Greek iambic poet who composed verses depicting the vulgar side of life in Ionian society. He was celebrat ...

. The poem may have connections to the Hellenistic ''Arae'' of Euphorion of Chalcis, but it is also very much in the pastoral tradition of Theocritus and the '' Eclogues''. The poem opens pastorally by addressing Battarus, a friend whose farm has also been confiscated and describing the actions of the soldier called Lycurgus. First the speaker curses the plants on the farm with bareness and then asks the forests to burn before Lycurgus destroys them with his axe. He then prays to Neptune for a flood to destroy the farm and for the land to turn into a swamp. The poem ends with a farewell to his farm and his lover, Lydia.

''Lydia'' ("Lydia")

This hexameter lament in 80 lines was connected to the ''Dirae'' because of the mention of Lydia in that poem but is probably an independent piece. It also has a pastoral setting and is in the tradition of Theocritus' amatory idylls and Latin love elegy. It begins with the poet saying he envies the countryside which Lydia inhabits and describes his pain at his separation from her. He looks to the animal world and the astronomical world with their amorous pairings and feels despair at the passing of the golden age. He describes the love of Jupiter and Juno, Venus and Adonis, and Aurora. He ends with the impossible wish to have been born in a better age.

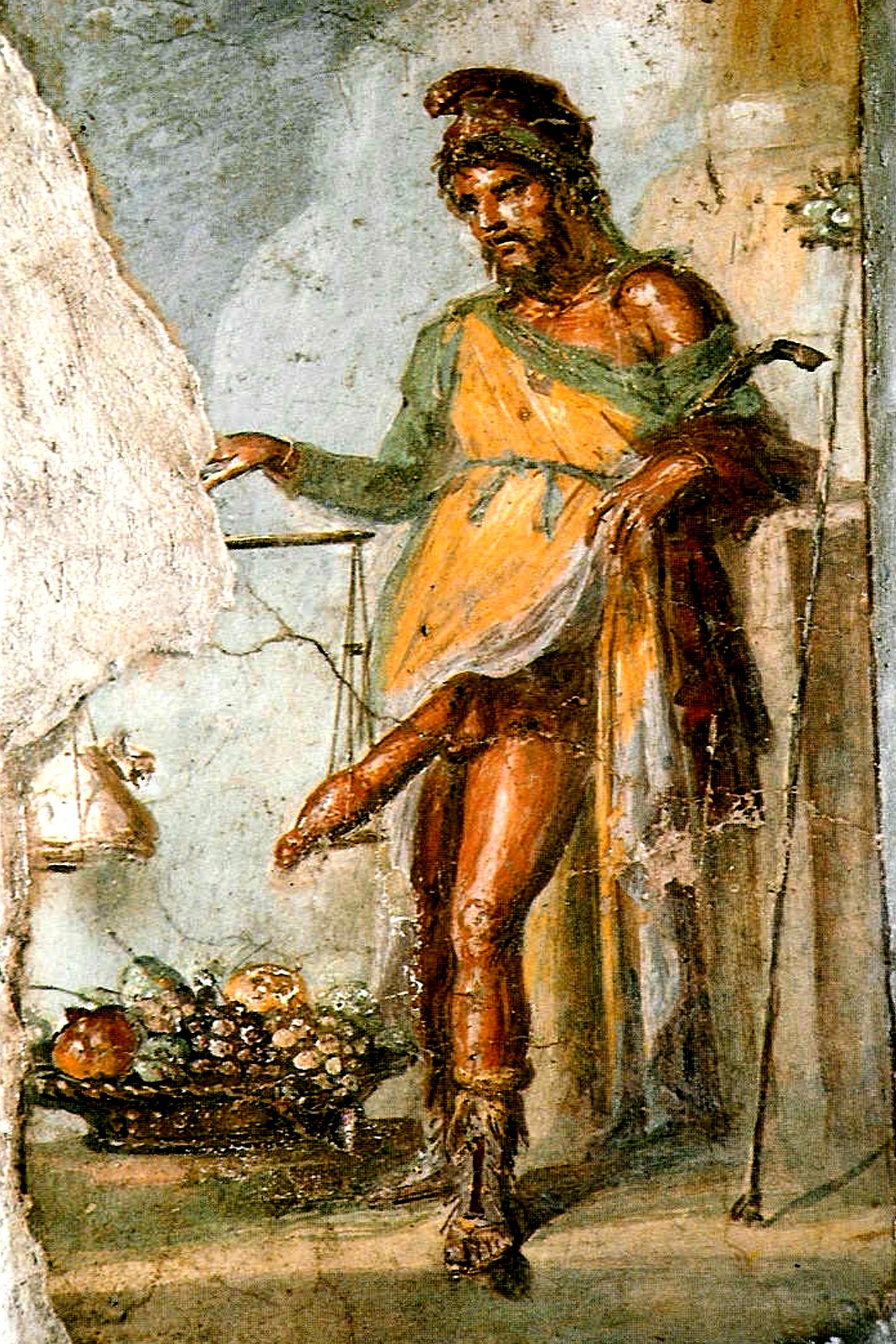

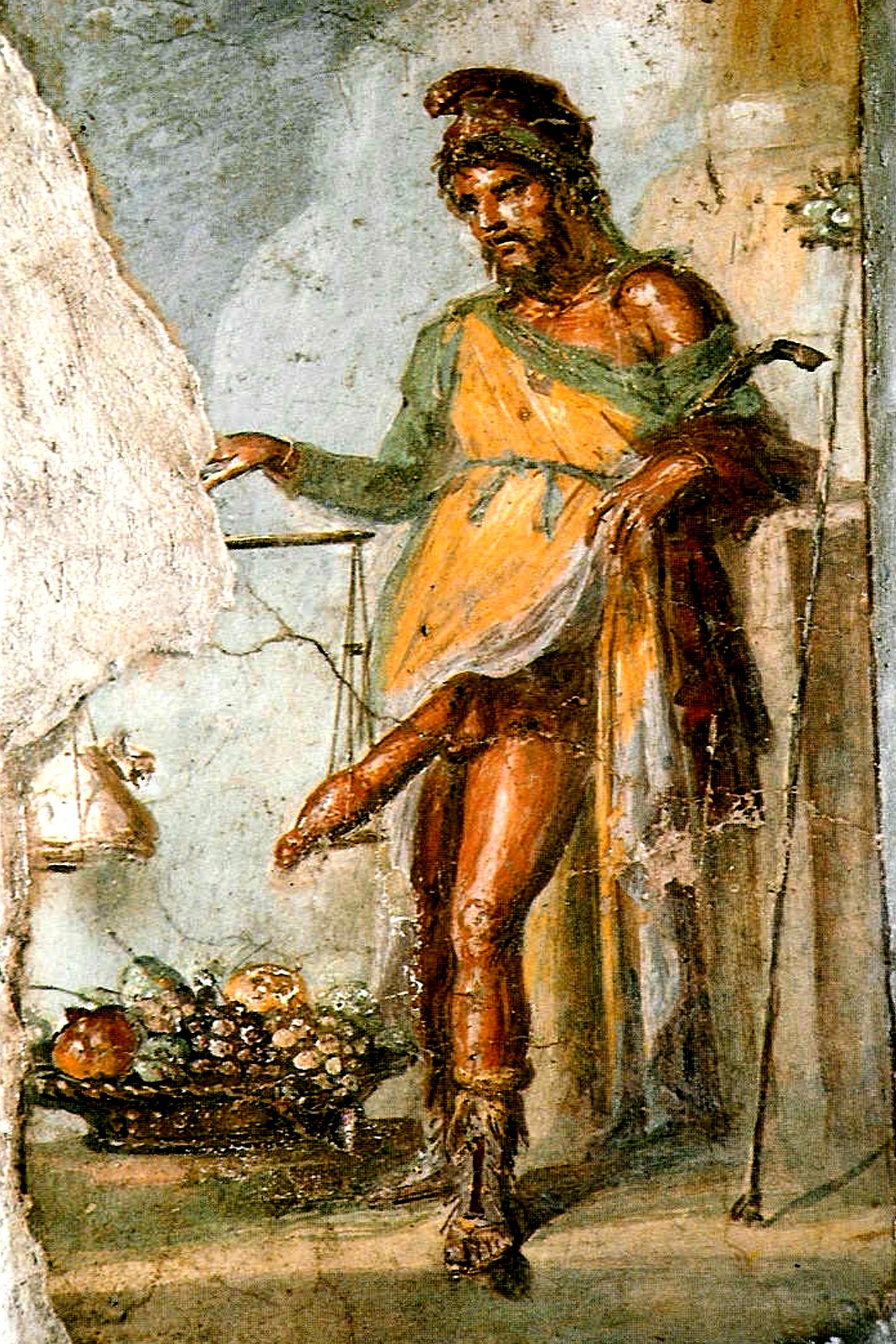

''Priapea'' ("Priapus Poems")

This is a collection of three poems, each in a different meter, with the god Priapus as the speaker. ''Priapea'' are a traditional subgenre of Greek poetry and are primarily found in Greek epigrams. A notable piece of Priapic poetry can be found in Theocritus 13 and Roman examples can be found in Horace and Tibullus as well as the 80 epigrams of the Carmina Priapea. The first poem in two elegiac couplets is a mock-inscription in which the god describes the setting of his statue at different seasons and his dislike of winter and fear of being made into firewood. The second poem is in 21 iambic trimeters. Priapus addresses a passer-by, describes how he protects and nourishes the farm through the seasons, and demands respect, as his wooden phallus can double as a club. The third poem is composed of 21 lines in Priapean metre (– x – u u – u – , – x – u u – x). In it, the Priapus statue addresses a group of boys who want to rob the farm. He describes his protection of the farm and the worship the owners give it. He ends by telling the boys to rob a neighbor's farm whose Priapus is careless.''Catalepton'' ("Trifles")

The ''Catalepton'' is a collection of fifteen or sixteen poems in various meters. The first elegiac poem is addressed to Tucca and describes the poet's separation from his lover. The second makes fun of a fellow writer for his obsession with Attic dialect. The third elegiac piece is a description of a successful eastern general who fell from power. Poem 4 in elegiacs is on the poet's friendship and admiration for Octavius Musa. Poem 5 describes a poet's giving up of rhetorical study to learn philosophy with Siro. The elegiac sixth poem criticizes Noctuinus and his father-in-law for some scandal with a girl. Poem 7 in elegiacs talks about love and plays with Greek words in Latin poetry. The eighth elegiac poem addresses the farm of Siro as being dear to the poet as his Mantuan and Cremonan estates. Poem 9 is a long elegiac piece which is an encomium to Messalla describing the poet's pastoral poetry, praising Messalla's wife, Sulpicia, and recounting his military achievements. Poem 10 is a parody of Catullus 4 and describes the career of the old muleteer Sabinus. The elegiac poem 11 is a mock lament for the drunken Octavius Musa. Poem 12 makes fun of Noctuinus for his two lovers. Poem 13 is in iambics and attacks a certain Lucienus or Luccius for his love affairs and seedy living. Poem 13a is an elegiac epitaph on an unknown scholar. Poem 14 is an elegiac prayer to Venus to help him complete the ''Aeneid'' and a promise to pay his vows to her. The final poem is an elegiac epigram for Virgil's tomb signed by Varius. Scholarly support for a Virgilian authorship of the Catalepton remains significant.''Elegiae in Maecenatem'' ("Elegies for Maecenas")

The ''Elegiae'' are two poems on the death of Maecenas (8 BC) in elegiac couplets whose ascription to Virgil (70-19 BC) is impossible. It has been conjectured by Scaliger that they are the work of an Albinovanus Pedo, who is also responsible for the ''Consolatio ad Liviam''. They were formerly transmitted as one long poem. The first poem opens with the author saying he has just written a lament for a young man, perhaps Drusus who died in 9 BC. The poet describes his first meeting with Maecenas introduced byLollius

Marcus LolliusHazel, ''Who's Who in the Roman World'', p.171 perhaps with the cognomen PaulinusSeneca).Seneca, Letter 114 Maecenas' life spent on culture rather than war is praised, as is his service at Actium; a long mythological section compares Maecenas to

"The Poems of the Appendix Vergiliana."

''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'' 53:5-34. * Frank, T. 1920. "Vergil's Apprenticeship. I." ''Classical Philology'' 15.1: 23–38. * Peirano, Irene. 2012. ''The Rhetoric of the Roman Fake: Latin Pseudepigrapha in Context.'' Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. * Reeve, Michael D. 1976. "The Textual Tradition of the Appendix Vergiliana. ''Maia'' 28.3: 233–254. Culex *Barrett, A. A. 1970. "The Authorship of the Culex: An Evaluation of the Evidence." ''Latomus'' 29.2 : 348–362. *Barrett, A. A. 1970. "The Catalogue of Trees in the Culex." ''Classical World'' 63.7: 230–232. *Barrett, A. A. 1976. "The Poet's Intentions in the Culex." ''Latomus'' 35.3 : 567–574. *Barrett, A. A. 1968. ''The Poetry of the Culex.'' Toronto: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. *Barrett, A. A. 1970. "The Topography of the Gnat's Descent". ''Classical Journal'' 65.6 : 255–257. *Chambert, Régine. 2004. "Vergil's Epicureanism in his Early Poems." In ''Vergil, Philodemus, and the Augustans'' Edited by David Armstrong, 43–60. Austin: University of Texas Press *Drew, D. L. 1925. ''Culex. Sources and Their Bearing on the Problem of Authorship.'' Oxford : Blackwell. *Ellis, R. 1882

"On the Culex and Other Poems of the Appendix Vergiliana"

''The American Journal of Philology'', Vol. 3, No. 11 (1882), pp. 271–284. *Fordyce C. J. 1932. "Octavius in the Culex." ''Classical Philology.'' 27.2: 174-174. *Fraenkel, Ed. 1952. "The Culex." ''Journal of Roman Studies'' 42.1-2: 1–9. *Jacobson, Howard. 2004

"The Date of ''Culex''."

''Phoenix'' 58.3–4: 345–347. *Kearey, T. 2018. "(Mis)reading the Gnat: Truth and Deception in the Pseudo-Virgilian Culex." ''Ramus'' 47.2: 174–196. *Kennedy, D. F. 1982. "Gallus and the Culex." ''Classical Quarterly'' 32: 371–389. *Most, Glenn. 1987. "The Virgilian Culex." In ''Homo Viator: Classical Essays for John Bramble.'' Edited by Bramble, J. C., Michael Whitby, Philip R Hardie, and Mary Whitby, 199–209. *Ross, D. O. 1975. "The Culex and Moretum as Post-Augustan Literary Parodies." ''Harvard Studies in Classical Philology'' 79: 235–263. *Walker L. V. 1929. "Vergil's Descriptive Art." ''Classical Journal'' 24.9: 666–679. Ciris *Connors, Catherine. 1991. "Simultaneous Hunting and Herding at Ciris 297–300." ''The Classical Quarterly'' 41.2: 556–559. *Gorman, Vanessa B. 1995. "Vergilian Models for the Characterization of Scylla in the Ciris." ''Vergilius'' 41: 35–48. *Kayachev, Boris. 2016. "Allusion and Allegory: Studies in the Ciris." ''Beiträge zur Altertumskunde 346.'' Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. *Knox, P. E. 1983. "Cinna, the Ciris, and Ovid." ''Classical Philology'' 78.4, 309–311. * Lyne, R. O. A. M. 1978. ''Ciris. A Poem Attributed to Vergil.'' Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. *Lyne, R. 1971. "The Dating of the Ciris." ''The Classical Quarterly'' 21.1: 233–253. *Richardson L., Jr. 1944. ''Poetical Theory in Republican Rome. An Analytical Discussion of the Shorter Narrative Poems Written in Latin during the First Century B. C.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. *Steele, R. B. 1930. "The Authorship of the Ciris." ''The American Journal of Philology'' 51.2: 148–184. Copa *Cutolo Paolo. 1990. "The Genre of the Copa." ''ARCA: Classical and Medieval Texts, Papers, and Monographs'' 29: 115–119. * Drew, D. 1923. "The Copa." ''The Classical Quarterly'' 17.2: 73–81. * Drabkin, I. 1930. ''The Copa: An Investigation of the Problem of Date and Authorship, with Notes On Some Passages of the Poem''. Geneva, N.Y.: The W.F. Humphrey Press. *Goodyear F. R. D. 1977. "The Copa. A Text and Commentary." ''Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies'' 24: 117–131. *Grant, Mark. 2001. "The "Copa:" Poetry, Youth, and the Roman Bar." ''Proceedings of the Virgil Society'' 24: 121-134. * Henderson, John. 2002. "Corny Copa: The Motel Muse." In ''Cultivating the Muse: Struggles for Power and Inspiration in Classical Literature.'' Edited by Effrosini Spentzou and Don Fowler, 253–278. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. * McCracken, G. 1932. "The Originality of the "Copa"." ''The Classical Journal'' 28.2: 124-127. *Rosivach, Vincent J. 1996. "The Sociology of the Copa." ''Latomus'' 55.3: 605–614. *Tarrant Richard J. 1992. "Nights at the Copa: Observations on Language and Date." ''Harvard Studies in Classical Philology'' 94: 331–347. Moretum *Douglas, F. L. 1929. "A Study of the Moretum." Syracuse: Syracuse University. * Fitzgerald, William. 1996. "Labor and Laborer in Latin Poetry: The Case of the Moretum." ''Arethusa'' 29.3: 389–418. *Horsfall, Nicholas. 2001. "The "Moretum" Decomposed." ''Classica et Medioevalia'' 52: 303–317. *Kenney E. J. 1984. ''Moretum. The Ploughman's Lunch, A Poem Ascribed to Virgil.'' Bristol: Bristol Classical Press. *Rosivach, Vincent J. 1994. "Humbler Fare in the Moretum." NECN 22: 57–59. *Ross, D. O. 1975. "The Culex and Moretum as Post-Augustan Literary Parodies." ''Harvard Studies in Classical Philology'' 79: 235–263 Dirae * Breed, Brian W. 2012. "The Pseudo-Vergilian Dirae and the Earliest Responses to Vergilian Pastoral." ''Trends in Classics'' 4.1: 3–28. * Fraenkel, E. 1966. "The Dirae." ''The Journal of Roman Studies'' 56: 142-155 *Goodyear, F. R. D. 1971. "The Dirae." ''Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society'' 17: 30–43. * Mackie, C. 1992." Vergil's Dirae, South Italy, and Etruria." ''Phoenix'' 46.4: 352–361. *T homas, Richard F. 1988. "Exhausted Oats ( erg.Dirae 15)?" ''The American Journal of Philology'' 109.1: 69-70 * van der Graaf, Cornelis. 1945. ''The Dirae: With Translation and an Investigation of its Authorship.'' Leiden: Brill. Catalepton * Carlson, Gregory I. and Ernst A. Schmidt. 1971. “From and Transformation in Vergil's Catalepton.” ''The American Journal of Philology'' 92.2: 252–265. * Holzberg, N. 2004. "Impersonating Young Virgil: The Author of the Catalepton and His Libellus." ''Materiali E Discussioni per L'analisi Dei Testi Classici'' 52: 29–40. *Kajanto, I. 1975. "Who was Sabinus Ille ? A Reinterpretation of Catalepton 10." ''Arctos''9 : 47–55. * Khan, H. 1967. "The Humor of Catullus, Carm. 4, and the Theme of Virgil, Catalepton 10." ''The American Journal of Philology'' 88.2: 163-172 * Radford, R. 1923. "The Language of the Pseudo-Vergilian Catalepton with Especial Reference to Its Ovidian Characteristics." ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'' 54: 168–186. *Reeve, M. D. 1975. "The Textual Tradition of Aetna, Ciris and Catalepton." ''Maia'' 27: 231–247. *Richardson, L. 1972. "Catullus 4 and Catalepton 10 Again." ''The American Journal of Philology'' 93.1: 215–222. *Richmond, J. A. 1974. "The Archetype of the Priapea and Catalepton." ''Hermes'' 102: 300–304. *Schoonhoven, H. 1983. The Panegyricus Messallae. Date and relation with Catalepton 9. ''Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt'' 30.3 : 1681–1707. * Syme, R. 1958. "Sabinus the Muleteer." ''Latomus'' 17.1: 73–80.

Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum's ''Appendix Vergiliana'': Links to Latin texts and English translations

''Appendix Vergiliana'': The Minor Poems of Vergil in English translation by Joseph J. Mooney

Works in the Appendix Vergiliana at Perseus Digital Library

{{Authority control Poetry by Virgil Latin poems Appendix Vergiliana 1st-century BC Latin books

Bacchus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; grc, wikt:Διόνυσος, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstas ...

and describes the labors of Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted th ...

and his service to Omphale. The death is compared to the loss of Hesperus and Tithonus and ends with a prayer that the earth rest lightly on him. The second poem was separated by Scaliger and is far shorter, encompassing the dying words of Maecenas. First he wishes he had died before Drusus and then prays that he be remembered, that the Romans remain loyal to Augustus, that he have an heir, and that Augustus be divinized by Venus.

Notes

Bibliography

Overviews * Duckworth, G. E. 1966. "Studies in Latin Hexameter Poetry." ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'' 97: 67–113. * Fairclough, H. 1922"The Poems of the Appendix Vergiliana."

''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'' 53:5-34. * Frank, T. 1920. "Vergil's Apprenticeship. I." ''Classical Philology'' 15.1: 23–38. * Peirano, Irene. 2012. ''The Rhetoric of the Roman Fake: Latin Pseudepigrapha in Context.'' Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. * Reeve, Michael D. 1976. "The Textual Tradition of the Appendix Vergiliana. ''Maia'' 28.3: 233–254. Culex *Barrett, A. A. 1970. "The Authorship of the Culex: An Evaluation of the Evidence." ''Latomus'' 29.2 : 348–362. *Barrett, A. A. 1970. "The Catalogue of Trees in the Culex." ''Classical World'' 63.7: 230–232. *Barrett, A. A. 1976. "The Poet's Intentions in the Culex." ''Latomus'' 35.3 : 567–574. *Barrett, A. A. 1968. ''The Poetry of the Culex.'' Toronto: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. *Barrett, A. A. 1970. "The Topography of the Gnat's Descent". ''Classical Journal'' 65.6 : 255–257. *Chambert, Régine. 2004. "Vergil's Epicureanism in his Early Poems." In ''Vergil, Philodemus, and the Augustans'' Edited by David Armstrong, 43–60. Austin: University of Texas Press *Drew, D. L. 1925. ''Culex. Sources and Their Bearing on the Problem of Authorship.'' Oxford : Blackwell. *Ellis, R. 1882

"On the Culex and Other Poems of the Appendix Vergiliana"

''The American Journal of Philology'', Vol. 3, No. 11 (1882), pp. 271–284. *Fordyce C. J. 1932. "Octavius in the Culex." ''Classical Philology.'' 27.2: 174-174. *Fraenkel, Ed. 1952. "The Culex." ''Journal of Roman Studies'' 42.1-2: 1–9. *Jacobson, Howard. 2004

"The Date of ''Culex''."

''Phoenix'' 58.3–4: 345–347. *Kearey, T. 2018. "(Mis)reading the Gnat: Truth and Deception in the Pseudo-Virgilian Culex." ''Ramus'' 47.2: 174–196. *Kennedy, D. F. 1982. "Gallus and the Culex." ''Classical Quarterly'' 32: 371–389. *Most, Glenn. 1987. "The Virgilian Culex." In ''Homo Viator: Classical Essays for John Bramble.'' Edited by Bramble, J. C., Michael Whitby, Philip R Hardie, and Mary Whitby, 199–209. *Ross, D. O. 1975. "The Culex and Moretum as Post-Augustan Literary Parodies." ''Harvard Studies in Classical Philology'' 79: 235–263. *Walker L. V. 1929. "Vergil's Descriptive Art." ''Classical Journal'' 24.9: 666–679. Ciris *Connors, Catherine. 1991. "Simultaneous Hunting and Herding at Ciris 297–300." ''The Classical Quarterly'' 41.2: 556–559. *Gorman, Vanessa B. 1995. "Vergilian Models for the Characterization of Scylla in the Ciris." ''Vergilius'' 41: 35–48. *Kayachev, Boris. 2016. "Allusion and Allegory: Studies in the Ciris." ''Beiträge zur Altertumskunde 346.'' Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. *Knox, P. E. 1983. "Cinna, the Ciris, and Ovid." ''Classical Philology'' 78.4, 309–311. * Lyne, R. O. A. M. 1978. ''Ciris. A Poem Attributed to Vergil.'' Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. *Lyne, R. 1971. "The Dating of the Ciris." ''The Classical Quarterly'' 21.1: 233–253. *Richardson L., Jr. 1944. ''Poetical Theory in Republican Rome. An Analytical Discussion of the Shorter Narrative Poems Written in Latin during the First Century B. C.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. *Steele, R. B. 1930. "The Authorship of the Ciris." ''The American Journal of Philology'' 51.2: 148–184. Copa *Cutolo Paolo. 1990. "The Genre of the Copa." ''ARCA: Classical and Medieval Texts, Papers, and Monographs'' 29: 115–119. * Drew, D. 1923. "The Copa." ''The Classical Quarterly'' 17.2: 73–81. * Drabkin, I. 1930. ''The Copa: An Investigation of the Problem of Date and Authorship, with Notes On Some Passages of the Poem''. Geneva, N.Y.: The W.F. Humphrey Press. *Goodyear F. R. D. 1977. "The Copa. A Text and Commentary." ''Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies'' 24: 117–131. *Grant, Mark. 2001. "The "Copa:" Poetry, Youth, and the Roman Bar." ''Proceedings of the Virgil Society'' 24: 121-134. * Henderson, John. 2002. "Corny Copa: The Motel Muse." In ''Cultivating the Muse: Struggles for Power and Inspiration in Classical Literature.'' Edited by Effrosini Spentzou and Don Fowler, 253–278. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. * McCracken, G. 1932. "The Originality of the "Copa"." ''The Classical Journal'' 28.2: 124-127. *Rosivach, Vincent J. 1996. "The Sociology of the Copa." ''Latomus'' 55.3: 605–614. *Tarrant Richard J. 1992. "Nights at the Copa: Observations on Language and Date." ''Harvard Studies in Classical Philology'' 94: 331–347. Moretum *Douglas, F. L. 1929. "A Study of the Moretum." Syracuse: Syracuse University. * Fitzgerald, William. 1996. "Labor and Laborer in Latin Poetry: The Case of the Moretum." ''Arethusa'' 29.3: 389–418. *Horsfall, Nicholas. 2001. "The "Moretum" Decomposed." ''Classica et Medioevalia'' 52: 303–317. *Kenney E. J. 1984. ''Moretum. The Ploughman's Lunch, A Poem Ascribed to Virgil.'' Bristol: Bristol Classical Press. *Rosivach, Vincent J. 1994. "Humbler Fare in the Moretum." NECN 22: 57–59. *Ross, D. O. 1975. "The Culex and Moretum as Post-Augustan Literary Parodies." ''Harvard Studies in Classical Philology'' 79: 235–263 Dirae * Breed, Brian W. 2012. "The Pseudo-Vergilian Dirae and the Earliest Responses to Vergilian Pastoral." ''Trends in Classics'' 4.1: 3–28. * Fraenkel, E. 1966. "The Dirae." ''The Journal of Roman Studies'' 56: 142-155 *Goodyear, F. R. D. 1971. "The Dirae." ''Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society'' 17: 30–43. * Mackie, C. 1992." Vergil's Dirae, South Italy, and Etruria." ''Phoenix'' 46.4: 352–361. *T homas, Richard F. 1988. "Exhausted Oats ( erg.Dirae 15)?" ''The American Journal of Philology'' 109.1: 69-70 * van der Graaf, Cornelis. 1945. ''The Dirae: With Translation and an Investigation of its Authorship.'' Leiden: Brill. Catalepton * Carlson, Gregory I. and Ernst A. Schmidt. 1971. “From and Transformation in Vergil's Catalepton.” ''The American Journal of Philology'' 92.2: 252–265. * Holzberg, N. 2004. "Impersonating Young Virgil: The Author of the Catalepton and His Libellus." ''Materiali E Discussioni per L'analisi Dei Testi Classici'' 52: 29–40. *Kajanto, I. 1975. "Who was Sabinus Ille ? A Reinterpretation of Catalepton 10." ''Arctos''9 : 47–55. * Khan, H. 1967. "The Humor of Catullus, Carm. 4, and the Theme of Virgil, Catalepton 10." ''The American Journal of Philology'' 88.2: 163-172 * Radford, R. 1923. "The Language of the Pseudo-Vergilian Catalepton with Especial Reference to Its Ovidian Characteristics." ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'' 54: 168–186. *Reeve, M. D. 1975. "The Textual Tradition of Aetna, Ciris and Catalepton." ''Maia'' 27: 231–247. *Richardson, L. 1972. "Catullus 4 and Catalepton 10 Again." ''The American Journal of Philology'' 93.1: 215–222. *Richmond, J. A. 1974. "The Archetype of the Priapea and Catalepton." ''Hermes'' 102: 300–304. *Schoonhoven, H. 1983. The Panegyricus Messallae. Date and relation with Catalepton 9. ''Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt'' 30.3 : 1681–1707. * Syme, R. 1958. "Sabinus the Muleteer." ''Latomus'' 17.1: 73–80.

External links

Corpus Scriptorum Latinorum's ''Appendix Vergiliana'': Links to Latin texts and English translations

''Appendix Vergiliana'': The Minor Poems of Vergil in English translation by Joseph J. Mooney

Works in the Appendix Vergiliana at Perseus Digital Library

{{Authority control Poetry by Virgil Latin poems Appendix Vergiliana 1st-century BC Latin books