Countee Cullen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

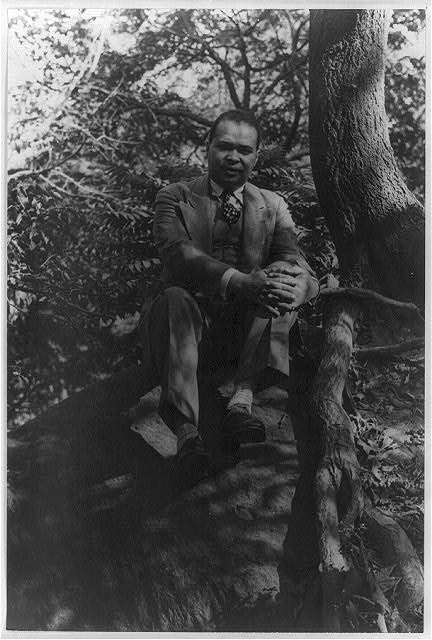

Countee Cullen (born Countee LeRoy Porter; May 30, 1903 – January 9, 1946) was an American poet, novelist, children's writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.

Cullen married Yolande Du Bois on April 9, 1928. She was the surviving child of

Cullen married Yolande Du Bois on April 9, 1928. She was the surviving child of

The Harlem Renaissance movement was centered in the cosmopolitan community of Harlem, in New York City, which had attracted talented migrants from across the country. During the 1920s, a fresh generation of African-American writers emerged, although a few were Harlem-born. Other leading figures included Alain Locke ('' The New Negro'', 1925),

The Harlem Renaissance movement was centered in the cosmopolitan community of Harlem, in New York City, which had attracted talented migrants from across the country. During the 1920s, a fresh generation of African-American writers emerged, although a few were Harlem-born. Other leading figures included Alain Locke ('' The New Negro'', 1925),

As well as writing books, Cullen promoted the work of other black writers. But by 1930 his reputation as a poet had waned. In 1932, his only novel was published, ''One Way to Heaven'', a social comedy of lower-class blacks and the bourgeoisie in New York City.

From 1934 until the end of his life, he taught English, French, and creative writing at

As well as writing books, Cullen promoted the work of other black writers. But by 1930 his reputation as a poet had waned. In 1932, his only novel was published, ''One Way to Heaven'', a social comedy of lower-class blacks and the bourgeoisie in New York City.

From 1934 until the end of his life, he taught English, French, and creative writing at

Countee Cullen: The Poetry FoundationCountee Cullen – Poets.org, from the Academy of Academic Poets: Countee CullenModern American Poetry: Countee Cullen"Poets of Cambridge U.S.A.: Countee Cullen"

Harvard Square Library, 2006.

''Color'' (1925) online pdf

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cullen, Countee 1903 births 1946 deaths 20th-century African-American writers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American poets 20th-century American LGBTQ people African-American male writers African-American novelists African-American poets American anthologists American bisexual writers American LGBTQ novelists American LGBTQ poets American male novelists American male poets Bisexual male writers Bisexual novelists Bisexual poets Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) DeWitt Clinton High School alumni Formalist poets Harlem Renaissance Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni African-American LGBTQ people LGBTQ people from New York (state) New York University alumni Novelists from New York (state)

Early life

Childhood

Countee LeRoy Porter was born on May 30, 1903, to Elizabeth Thomas Lucas. Due to a lack of records of his early childhood, historians have had difficulty identifying his birthplace.Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the List of United States ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, and Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

have been cited as possibilities. Although Cullen claimed to have been born in New York City, he also frequently referred to Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

, as his birthplace on legal applications. Cullen was brought to Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

at the age of nine by Amanda Porter, believed to be his paternal grandmother, who cared for him until her death in 1917.

Reverend Frederick A. Cullen, pastor of Salem Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself nationally. In 1939, th ...

, Harlem's largest congregation, and his wife, the former Carolyn Belle Mitchell, adopted the 15-year-old Countee Porter, although the adoption may not have been official. Frederick Cullen was a central figure in Countee's life, and acted as his father. The influential minister eventually became president of the Harlem chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

).

DeWitt Clinton High School

Cullen entered theDeWitt Clinton High School

DeWitt Clinton High School is a public high school located since 1929 in the Bronx borough of New York City. Opened in 1897 in Lower Manhattan as an all-boys school, it maintained that status for 86 years before becoming co-ed in 1983. From i ...

, then located in Hell's Kitchen

Hell's Kitchen, also known as Clinton, or Midtown West on real estate listings, is a neighborhood on the West Side of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, New York. It is considered to be bordered by 34th Street (or 41st Street) to the south, ...

.Perry: 4; cf. Shucard: 10. He excelled academically at the school and started writing poetry. He won a citywide poetry contest. At DeWitt, he was elected into the honor society, was editor of the weekly newspaper, and was elected vice-president of his graduating class. In January 1922, he graduated with honors in Latin, Greek, Mathematics, and French.

New York University, Harvard University and early publications

After graduating from high school, he attendedNew York University

New York University (NYU) is a private university, private research university in New York City, New York, United States. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded in 1832 by Albert Gallatin as a Nondenominational ...

(NYU). In 1923, at the Town Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

in New York City, he gave a speech to the League of Youth in which he said, “For we must be one thing or the other, an asset or a liability, the sinew in your wing to help you soar, or the chain to bind you to earth.” The speech was later printed in '' The Crisis'' (August 1923). Also in 1923, Cullen won second prize in the Witter Bynner National Competitions for Undergraduate Poetry, sponsored by the Poetry Society of America, for his book of poems titled, "The Ballad of the Brown Girl". Soon after, he was publishing poetry in national periodicals such as ''Harper's'', ''The Crisis'', ''Opportunity'', ''The Bookman'', and ''Poetry'', earning him a national reputation. The ensuing year, he again placed second in the contest, finally winning first prize in 1925. He competed in a poetry contest sponsored by ''Opportunity'' and came in second with "To One Who Say Me Nay", losing to Langston Hughes's " The Weary Blues". Cullen graduated from NYU in 1925 and was one of eleven students selected to Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

.

That same year, Cullen entered Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

to pursue a master's

A master's degree (from Latin ) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional prac ...

in English, and published ''Color'', his first collection of poems that later became a landmark of the Harlem Renaissance.Perry: 7. Written in a careful, traditional style, the work celebrated black beauty and deplored the effects of racism. The volume included "Heritage" and " Incident", probably his most famous poems. "Yet Do I Marvel", about racial identity and injustice, showed the literary influence of William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poetry, Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romanticism, Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Balla ...

and William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake has become a seminal figure in the history of the Romantic poetry, poetry and visual art of the Roma ...

, but its subject was far from the world of their Romantic sonnets. The poet accepts that there is God, and "God is good, well-meaning, kind", but he finds a contradiction in his own plight in a racist society: he is black and a poet. In 1926, Cullen graduated with a master's degreeShucard: 7. while also serving as the guest editor of a special "Negro Poets" issue of the poetry magazine, ''Palms''. The appointment led to ''Harper's'' inviting him to edit an anthology of Black poetry in 1927.

Sexuality

American writer Alain Locke helped Cullen come to terms with his sexuality. Locke wanted to introduce a new generation of African-American writers, such as Countee Cullen, to the reading public. Locke also sought to present the authentic natures of sex and sexuality through writing, creating a kind of relationship with those who felt the same. Locke introduced Cullen to gay-affirming material, such as the work ofEdward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rights and prison reform whilst advocating vegetarianism and taking a stance against vivise ...

, at a time when most gays were in the closet. In March 1923, Cullen wrote to Locke about Carpenter's work: "It opened up for me soul windows which had been closed; it threw a noble and evident light on what I had begun to believe, because of what the world believes, ignoble and unnatural".

Critics and historians have not reached consensus as to Cullen's sexuality, partly because Cullen was unsure of this himself. Cullen's first marriage, to Yolande Du Bois, experienced difficulties before ending in divorce. He subsequently had relationships with many different men, although each ended poorly. Each relationship had a sense of shame or secrecy, such as his relationship with Edward Atkinson. Cullen later married Ida Robertson while potentially in a relationship with Atkinson. Letters between Cullen and Atkinson suggest a romantic interest, although there is no concrete evidence that they were in a sexual relationship.

Relationships

Cullen married Yolande Du Bois on April 9, 1928. She was the surviving child of

Cullen married Yolande Du Bois on April 9, 1928. She was the surviving child of W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

and his first wife Nina Gomer Du Bois

Nina Gomer Du Bois (July 4, 1870 – July 26, 1950) was an American civil rights activist, Baháʼí Faith practitioner, and homemaker. She served on the executive committee of the Women's International Circle of Peace and Foreign Relations in 192 ...

, whose son had died as an infant. The two young people were said to have been introduced by Cullen's close friend Harold Jackman. They met in the summer of 1923 when both were in college: she was at Fisk University and he was at NYU. Cullen's parents owned a summer home in Pleasantville, New Jersey near the Jersey Shore, and Yolande and her family were likely also vacationing in the area when they first met.

While at Fisk, Yolande had had a romantic relationship with the jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

saxophonist

The saxophone (often referred to colloquially as the sax) is a type of Single-reed instrument, single-reed woodwind instrument with a conical body, usually made of brass. As with all single-reed instruments, sound is produced when a reed (mouthpi ...

Jimmie Lunceford

James Melvin Lunceford (June 6, 1902 – July 12, 1947) was an American jazz alto saxophonist and bandleader in the swing era.

Early life

Lunceford was born on a farm in the Evergreen community, west of the Tombigbee River, near Fulton, ...

. However, her father disapproved of Lunceford. The relationship ended after Yolande accepted her father's preference of a marriage to Cullen.

The wedding was the social event of the decade among the African-American elite. Cullen, along with W.E.B. Du Bois, planned the details of the wedding with little help from Yolande. Every detail of the wedding, including the rail car used for transportation and Cullen receiving the marriage license four days prior to the wedding day, was considered big news and was reported to the public by the African-American press. His father, Frederick A. Cullen, officiated at the wedding. The church was overcrowded, as 3,000 people came to witness the ceremony.

After the newly wedded couple had a short honeymoon, Cullen traveled to Paris with his guardian/father, Frederick Cullen, and best man Jackman. Yolande soon joined him there, but they had difficulties from the first. A few months after their wedding, Cullen wrote a letter to Yolande confessing his love for men. Yolande told her father and filed for divorce. Her father wrote separately to Cullen, saying that he thought Yolande's lack of sexual experience was the reason the marriage did not work out. The couple divorced in 1930 in Paris. The details were negotiated between Cullen and Yolande's father, as the wedding details had been.

With the exception of this marriage before a huge congregation, Cullen was a shy person. He was not flamboyant with any of his relationships. It was rumored that Cullen had developed a relationship with Jackman, "the handsomest man in Harlem", which contributed to Cullen and Yolande's divorce. The young, dashing Jackman was a school teacher and, thanks to his handsome visage, a prominent figure among Harlem's gay elite. According to Thomas Wirth, author of ''Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance, Selections from the Work of Richard Bruce Nugent'', there is no evidence that the men were lovers, despite newspaper stories and gossip suggesting the contrary. He married Ida Mae Roberson in 1940 and lived, apparently happily, with her until his death in 1946. In the early 1940s, they lived on Sugar Hill in West Harlem at the Garrison Apartments.

Jackman's diaries, letters, and outstanding collections of memorabilia are held in depositories across the country, such as the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University

The Tulane University of Louisiana (commonly referred to as Tulane University) is a private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by a cohort of medical doctors, it b ...

in New Orleans and Clark Atlanta University

Clark Atlanta University (CAU or Clark Atlanta) is a private, Methodist, historically black research university in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It was founded on September19, 1865, as Atlanta University, it was the first HBCU in the South ...

in Atlanta, Georgia. At Cullen's death, Jackman requested that his collection in Georgia be renamed, from the Harold Jackman Collection to the Countee Cullen Memorial Collection, in honor of his friend. After Jackman died of cancer in 1961, the collection at Clark Atlanta University was renamed as the Cullen-Jackman Collection to honor them both.

Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance movement was centered in the cosmopolitan community of Harlem, in New York City, which had attracted talented migrants from across the country. During the 1920s, a fresh generation of African-American writers emerged, although a few were Harlem-born. Other leading figures included Alain Locke ('' The New Negro'', 1925),

The Harlem Renaissance movement was centered in the cosmopolitan community of Harlem, in New York City, which had attracted talented migrants from across the country. During the 1920s, a fresh generation of African-American writers emerged, although a few were Harlem-born. Other leading figures included Alain Locke ('' The New Negro'', 1925), James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871June 26, 1938) was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ...

(''Black Manhattan'', 1930), Claude McKay

Festus Claudius "Claude" McKay OJ (September 15, 1890See Wayne F. Cooper, ''Claude McKay, Rebel Sojourner In The Harlem Renaissance'' (New York, Schocken, 1987) p. 377 n. 19. As Cooper's authoritative biography explains, McKay's family predate ...

('' Home to Harlem'', 1928), Langston Hughes (''The Weary Blues'', 1926), Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (January 7, 1891 – January 28, 1960) was an American writer, anthropologist, folklorist, and documentary filmmaker. She portrayed racial struggles in the early-20th-century American South and published research on Hoodoo ...

('' Jonah's Gourd Vine'', 1934), Wallace Thurman (''Harlem: A Melodrama of Negro Life'', 1929), Jean Toomer (''Cane

Cane or caning may refer to:

*Walking stick, or walking cane, a device used primarily to aid walking

* Assistive cane, a walking stick used as a mobility aid for better balance

* White cane, a mobility or safety device used by blind or visually i ...

'', 1923) and Arna Bontemps

Arna Wendell Bontemps ( ) (October 13, 1902 – June 4, 1973) was an American poet, novelist and librarian, and a noted member of the Harlem Renaissance.

Early life

Bontemps was born in 1902 in Alexandria, Louisiana, into a Louisiana Creole peopl ...

(''Black Thunder'', 1935). Writers benefited from newly available grants and scholarships, and were supported by such established white writers as Carl Van Vechten

Carl Van Vechten (; June 17, 1880December 21, 1964) was an American writer and Fine-art photography, artistic photographer who was a patron of the Harlem Renaissance and the literary estate, literary executor of Gertrude Stein. He gained fame ...

.

The Harlem Renaissance was influenced by a movement called ''Négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, mainly developed by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians in the Africa ...

'', which represents "the discovery of black values and the Negro’s awareness of his situation". Cullen saw Negritude as an awakening of a race consciousness and black modernism that flowed into Harlem. Cullen's poetry "Heritage" and "Dark Tower" reflect ideas of the Negritude movement. These poems examine African roots and intertwine them with a fresh aspect of African-American life.

Cullen's work intersects with the Harlem community and such prominent figures of the Renaissance as Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American Jazz piano, jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous Big band, jazz orchestra from 1924 through the rest of his life.

Born and raised in Washington, D ...

and poet and playwright Langston Hughes. Ellington admired Cullen for confronting a history of oppression and shaping a new voice of “great achievement over fearful odds”. Cullen maintained close friendships with two other prominent writers, Hughes and Alain Locke. However, Hughes critiqued Cullen, albeit indirectly, and other Harlem Renaissance writers, for the “desire to run away spiritually from heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offi ...

race”. Hughes condemned “the desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of American standardization, and to be as little Negro and as much American as possible.” Though Hughes critiqued Cullen, he still admired his work and noted the significance of his writing.

Professional career

The social, cultural, and artistic explosion known as the Harlem Renaissance was the first time in American history that a large body of literary, art and musical work was contributed by African-American writers and artists. Cullen was at the epicenter of this new-found surge in literature. He considered poetry to be raceless. However, his poem "The Black Christ" took on a racial theme, exploring a black youth convicted of a crime he did not commit. "But shortly after in the early 1930s, his work was almost completely reeof racial subject matter. His poetry instead focused on idyllic beauty and other classic romantic subjects." Cullen worked as assistant editor for ''Opportunity'' magazine, where his column, "The Dark Tower", increased his literary reputation. Cullen's poetry collections ''The Ballad of the Brown Girl'' (1927) and ''Copper Sun'' (1927) explored similar themes as ''Color'', but they were not so well received. Cullen'sGuggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are Grant (money), grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, endowed by the late Simon Guggenheim, Simon and Olga Hirsh Guggenheim. These awards are bestowed upon indiv ...

of 1928 enabled him to study and write abroad.

Between the years 1928 and 1934, Cullen traveled back and forth between France and the United States. By 1929 Cullen had published four volumes of poetry. The title poem of ''The Black Christ and Other Poems'' (1929) was criticized for its use of Christian religious imagery; Cullen compared the lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of i ...

of a black man to the crucifixion of Jesus.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

Junior High School

Middle school, also known as intermediate school, junior high school, junior secondary school, or lower secondary school, is an educational stage between primary school and secondary school.

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, middle school includes ...

in New York City. During this period, he also wrote two works for young readers: ''The Lost Zoo'' (1940), poems about the animals who were killed in the Flood

A flood is an overflow of water (list of non-water floods, or rarely other fluids) that submerges land that is usually dry. In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Floods are of significant con ...

, and ''My Lives and How I Lost Them'', an autobiography of his cat. Along with Herman W. Porter, Cullen also provided guidance to a young James Baldwin during his time at the school.

In the last years of his life, Cullen wrote mostly for the theatre. He worked with Arna Bontemps to adapt Bontemps's 1931 novel ''God Sends Sunday'' as the musical '' St. Louis Woman'' (1946, published in 1971). Its score was composed by Harold Arlen

Harold Arlen (born Hyman Arluck; February 15, 1905 – April 23, 1986) was an American composer of popular music, who composed over 500 songs, a number of which have become known worldwide. In addition to composing the songs for the 1939 film ' ...

and Johnny Mercer

John Herndon Mercer (November 18, 1909 – June 25, 1976) was an American lyricist, songwriter, and singer, as well as a record label executive who co-founded Capitol Records with music industry businessmen Buddy DeSylva and Wallichs Music Cit ...

, both white. The Broadway musical, set in a poor black neighborhood of St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

, was criticized by black intellectuals for creating a negative image of black Americans. In another stretch, Cullen translated the Greek tragedy ''Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; ; ) is the daughter of Aeëtes, King Aeëtes of Colchis. Medea is known in most stories as a sorceress, an accomplished "wiktionary:φαρμακεία, pharmakeía" (medicinal magic), and is often depicted as a high- ...

'' by Euripides

Euripides () was a Greek tragedy, tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to ...

, which was published in 1935 as ''The Medea and Some Poems'', with a collection of sonnets and short lyrics.

Several years later, Cullen died from high blood pressure and uremic poisoning on January 9, 1946, aged 42. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

.

Honors

The Countee Cullen Library, a Harlem branch location of theNew York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second-largest public library in the United States behind the Library of Congress a ...

, was named in his honor. In 2013, he was inducted into the New York Writers Hall of Fame.

In 1949

Events

January

* January 1 – A United Nations-sponsored ceasefire brings an end to the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947. The war results in a stalemate and the division of Kashmir, which still continues as of 2025

* January 2 – Luis ...

the anthology

In book publishing, an anthology is a collection of literary works chosen by the compiler; it may be a collection of plays, poems, short stories, songs, or related fiction/non-fiction excerpts by different authors. There are also thematic and g ...

radio drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

''Destination Freedom

''Destination Freedom'' was a series of weekly radio programs that was produced by WMAQ in Chicago. The first set ran from 1948 to 1950 and it presented the biographical histories of prominent African Americans such as George Washington Carver ...

'', written by Richard Durham, recapped parts of his life.

Literary influences

Due to Cullen's mixed identity, he developed an aesthetic that embraced both black and white cultures. He was a firm believer that poetry surpassed race and that it could be used to bring the races closer together. Although race was a recurring theme in his works, Cullen wanted to be known as a poet not strictly defined by race. Cullen developed his Eurocentric style of writing from his exposure to Graeco-Roman Classics and English Literature, work he was exposed to while attending universities like New York University and Harvard. In his collection of poems ''To the Three for Whom the Book'' Cullen uses Greek methodology to explore race and identity and writes aboutMedusa

In Greek mythology, Medusa (; ), also called Gorgo () or the Gorgon, was one of the three Gorgons. Medusa is generally described as a woman with living snakes in place of hair; her appearance was so hideous that anyone who looked upon her wa ...

, Theseus

Theseus (, ; ) was a divine hero in Greek mythology, famous for slaying the Minotaur. The myths surrounding Theseus, his journeys, exploits, and friends, have provided material for storytelling throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes desc ...

, Phasiphae, and the Minotaur

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur (, ''Mīnṓtauros''), also known as Asterion, is a mythical creature portrayed during classical antiquity with the head and tail of a bull and the body of a man or, as described by Roman poet Ovid, a being "par ...

. Although continuing to develop themes of race and identity in his work, Cullen found artistic inspiration in ancient Greek and Roman literature.

Cullen was also influenced by the Romantics and studied subjects of love, romance, and religion. John Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tub ...

and Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American lyric poetry, lyrical poet and playwright. Millay was a renowned social figure and noted Feminism, feminist in New York City during the Roaring Twenties and beyond. ...

both influenced Cullen's style of writing. In '' Caroling Dusk,'' an anthology edited by Cullen, he expands on his belief of using a Eurocentric style of writing. He writes: "As heretical as it may sound, there is the probability that Negro poets, dependent as they are on the English language, may have more to gain from the rich background of English and American poetry than from the nebulous atavistic yearnings towards an African inheritance." Cullen believed that African-American poets should work within the English conventions of poetry to prove to white Americans that African Americans could participate in these classic traditions. He believed using a more traditional style of writing poetry would allow African Americans to build bridges between the black and white communities.

Major works

''Color''

''Color

Color (or colour in English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though co ...

'' is Countee Cullen's first published book and color is "in every sense its prevailing characteristic." Cullen discusses heavy topics regarding race and the distance of one's heritage from their motherland and how it is lost. It has been said that his poems fall into a variety of categories: those that with no mention were made of color. Secondly, the poems that circled around the consciousness of African Americans and how being a "Negro in a day like this" in America is very cruel. Through Cullen's writing, readers can view his own subjectivity of his inner workings and how he viewed the Negro soul and mind. He discusses the psychology of African Americans in his writings and gives an extra dimension that forces the reader to see a harsh reality of Americas past time. "Heritage" is one of Countee Cullen's best-known poems published in this book. Although it is published in Color, it originally appeared in ''The Survey'', March 1, 1925. Count Cullen wrote "Heritage" during a time when African-American artists were dreaming of Africa. During the Harlem Renaissance, Cullen, Hughes, and other poets were using their creative energy trying fuse Africa into the narrative of their African-American lives. In "Heritage", Cullen grapples with the separation of his African culture and history created by the institution of slavery. To Cullen, Africa was not a place of which he had personal knowledge. It was a place that he knew through someone else's description, passed down through generations. Africa was a place of heritage. Throughout the poem, he struggles with the cost of the cultural conversion and religious conversion of his ancestors when they were away "torn from Africa".

''The Black Christ''

''The Black Christ'' was a collection of poems published at the height of Cullen's career in 1929. The poems examine the relationship of faith and justice among African Americans. In some of the poems, Cullen equates the suffering of Christ in his crucifixion and the suffering of African Americans. This collection poems captures Cullen's idealistic aesthetic of race pride and religious skepticism. ''The Black Christ'' also takes a close look at the racial violence in America during the 1920s. By the time Cullen published this book of poetry, the concept of the Black Messiah was prevalent in other African-American writers such as Langston Hughes, Claude Mackay, and Jean Toomer.''Copper Sun''

''Copper Sun'' is a collection of poetry published in New York in 1927. The collection examines the sense of love, particularly a love or unity between white and black people. In some poems, love is ominous and leads to death. However, in general, the love extends not only to people but to natural elements such as plants, trees, etc. Many of the poems also link the concept of love to a Christian background. Yet, Cullen was also attracted to something both pagan as well as Christian. in one of his poems "One Day We Played a Game", the theme of love appears. The speaker calls: First love! First love!' I urged". (The poem portrays love as necessary to continue in life and that it is basic to life as the corner stone or the fundamental of building home.) Similarly, in "Love's Way", Cullen's poem portrays a love that shares and unifies the world. The poem suggests that "love is not demanding, all, itself/ Withholding aught; love's is nobler way/ of courtesy" . In the poem, the speaker contends that "Love rehabilitates unto the end." Love fixes itself, regrows, and heals.''The Medea and Some Poems''

Poetry collections

*''Color'', Harper & Brothers, 1925; Ayer, 1993, (includes the poems "Incident", "Near White", "Heritage", and others), illustrations by Charles Cullen *''Copper Sun'', Harper & Brothers, 1927 *''The Ballad of the Brown Girl'', Harper & Brothers, 1927, illustrations by Charles Cullen *''The Black Christ and Other Poems'', Harper & Brothers, 1929, illustrations by Charles Cullen *''The Medea and Some Poems'' (1935) *''On These I Stand: An Anthology of the Best Poems of Countee Cullen'', Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1947 * Gerald Lyn Early (ed.), ''My Soul's High Song: The Collected Writings of Countee Cullen'', Doubleday, 1991, *''Countee Cullen: Collected Poems'', Library of America, 2013,Prose

*''One Way to Heaven'' (1931) *''The Lost Zoo'', Harper & Brothers, 1940; Modern Curriculum Press, 1991, *''My Lives and How I Lost Them'', Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1942Drama

*''St. Louis Woman'' (1946)As editor

* ''Caroling Dusk: An Anthology of Verse by Black Poets of the Twenties: Anthology of Black Verse''. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1927.See also

*African-American literature

African American literature is the body of literature produced in the United States by writers of African descent. Phillis Wheatley was an enslaved African woman who became the first African American to publish a book of poetry, which was publis ...

* Harlem Renaissance

References

Further reading

* * * *External links

* * * *Countee Cullen: The Poetry Foundation

Harvard Square Library, 2006.

''Color'' (1925) online pdf

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cullen, Countee 1903 births 1946 deaths 20th-century African-American writers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American poets 20th-century American LGBTQ people African-American male writers African-American novelists African-American poets American anthologists American bisexual writers American LGBTQ novelists American LGBTQ poets American male novelists American male poets Bisexual male writers Bisexual novelists Bisexual poets Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) DeWitt Clinton High School alumni Formalist poets Harlem Renaissance Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni African-American LGBTQ people LGBTQ people from New York (state) New York University alumni Novelists from New York (state)