Council Of Vienne on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Council of Vienne was the fifteenth

The main item on the agenda of the Council not only cited the Order of Knights Templar itself, but also "its lands", which suggested that further seizures of property were proposed. Besides this, the agenda also invited archbishops and prelates to bring proposals for improvement in the life of the Church. Special notices were sent to the Templars directing them to send suitable (defenders) to the Council. The Grand Master

The main item on the agenda of the Council not only cited the Order of Knights Templar itself, but also "its lands", which suggested that further seizures of property were proposed. Besides this, the agenda also invited archbishops and prelates to bring proposals for improvement in the life of the Church. Special notices were sent to the Templars directing them to send suitable (defenders) to the Council. The Grand Master

''Catholic Encyclopedia''Council of Vienne

{{DEFAULTSORT:Council Of Vienne 1310s in France 1311 in Europe 1312 in Europe 1310s in religion Vienne Vienne Vienne Vienne, Isère Knights Templar Philip IV of France

ecumenical council

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote are ...

of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and met between 1311 and 1312 in Vienne, France. This occurred during the Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy (; ) was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon (at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire, now part of France) rather than in Rome (now the capital of ...

and was the only ecumenical council to be held in the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

(the previous 2 had been held in Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, which was under the Kingdom of Burgundy

Kingdom of Burgundy was a name given to various successive Monarchy, kingdoms centered in the historical region of Burgundy during the Middle Ages. The heartland of historical Burgundy correlates with the border area between France and Switze ...

). One of its principal acts was to withdraw papal support for the Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a Military order (religious society), military order of the Catholic Church, Catholic faith, and one of the most important military ord ...

at the instigation of Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. Jure uxoris, By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip&n ...

. The Council, unable to decide on a course of action, tabled the discussion. In March 1312 Philip arrived and pressured the Council and Clement to act. Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V (; – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his death, in April 1314. He is reme ...

passed papal bulls dissolving the Templar Order, confiscating their lands, and labeling them heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

.

Church reform was represented by the decision concerning the Franciscans

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest conte ...

, allowing abbots to decide how to interpret their Rule. The Beguines and Beghards

The Beguines () and the Beghards () were Christian lay religious orders that were active in Western Europe, particularly in the Low Countries, in the 13th–16th centuries. Their members lived in semi-monastic communities but did not take for ...

of Germany were condemned as heretics, while the council forbade marriage for clerics, concubinage, rape, fornication, adultery, and incest.

The council addressed the possibility of a crusade, hearing from James II of Aragon

James II (Catalan: ''Jaume II''; Aragonese: ''Chaime II;'' 10 April 1267 – 2 or 5 November 1327), called the Just, was the King of Aragon and Valencia and Count of Barcelona from 1291 to 1327. He was also the King of Sicily (as James I) f ...

and Henry II of Cyprus

Henry II (June 1270 – 31 March 1324) was the last crowned Kingdom of Jerusalem, King of Jerusalem (after the fall of Acre on 28 May 1291, this title became empty) and also ruled as Kingdom of Cyprus, King of Cyprus. He was of the Lusignan ...

, before deciding to assign Philip of France as its leader. It was through Philip's influence that Clement finally canonized Pietro Angelerio, taking care not to use his papal title Celestine V Celestine is a given name and a surname.

People Given name

* Pope Celestine I (died 432)

* Pope Celestine II (died 1144)

* Pope Celestine III (c. 1106–1198)

* Pope Celestine IV (died 1241)

* Pope Celestine V (1215–1296)

* Antipop ...

. The final act of the council was to establish university chairs for Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic languages.

Background

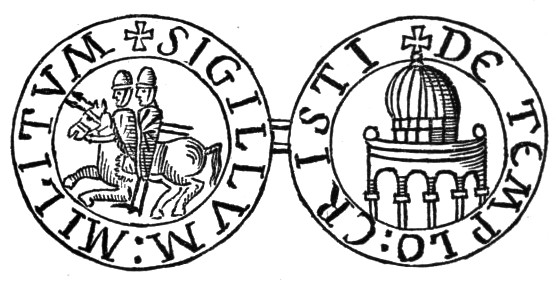

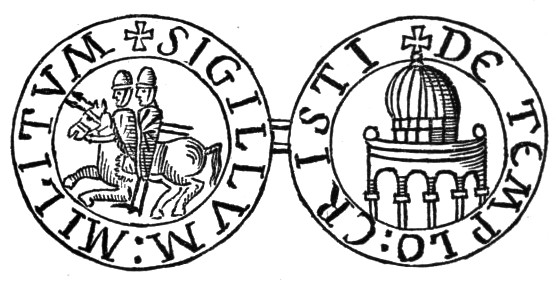

The Knights Templar were a military order founded in the twelfth century to ensure the safety ofpilgrim

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vocalize it as ...

s traveling to Jerusalem. In the following centuries the order grew in power and wealth. In the early 14th century, Philip IV of France urgently needed money to continue his war with England, and he accused the Grand Master of the Templars, Jacques De Molay

Jacques de Molay (; 1240–1250 – 11 or 18 March 1314), also spelled "Molai",Demurger, pp. 1–4. "So no conclusive decision can be reached, and we must stay in the realm of approximations, confining ourselves to placing Molay's date of birth ...

, of corruption and heresy. On 13 October 1307 Philip had all French Templars arrested, charged with heresy, and tortured until they allegedly confessed to their charges. These forced admissions released Philip from his obligation to repay loans obtained from the Templars and allowed him to confiscate the Templars' assets in France.

The arrests of the Knights Templar, coupled with the defiance of the Colonna cardinals and Philip IV against Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII (; born Benedetto Caetani; – 11 October 1303) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 until his death in 1303. The Caetani, Caetani family was of baronial origin with connections t ...

, convinced Clement V to call a general council. Though the site of Vienne was criticised for its lack of neutrality (being under the control of Philip), Clement nevertheless chose it as the site for the council.

Council

Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V (; – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his death, in April 1314. He is reme ...

convened the Council by issuing the bulls and on 12 August 1308.

The opening of the Council was delayed, giving time to the Templars to arrive so they could answer the charges put against them, and was not convened until 16 October 1311. The was sent to nearly 500 clerics, prelates, masters of militant Orders, and priors. The attendees consisted of twenty cardinals, four patriarchs, about one hundred archbishops and bishops, plus several abbots and priors. The great princes, including the rulers of Sicily, Hungary, Bohemia, Cyprus, and Scandinavia, as well as the kings of France, England, and the Iberian peninsula, had been invited. No king appeared, except Philip IV who arrived the following spring to pressure the council against the Templars.

Knights Templar

The main item on the agenda of the Council not only cited the Order of Knights Templar itself, but also "its lands", which suggested that further seizures of property were proposed. Besides this, the agenda also invited archbishops and prelates to bring proposals for improvement in the life of the Church. Special notices were sent to the Templars directing them to send suitable (defenders) to the Council. The Grand Master

The main item on the agenda of the Council not only cited the Order of Knights Templar itself, but also "its lands", which suggested that further seizures of property were proposed. Besides this, the agenda also invited archbishops and prelates to bring proposals for improvement in the life of the Church. Special notices were sent to the Templars directing them to send suitable (defenders) to the Council. The Grand Master Jacques de Molay

Jacques de Molay (; 1240–1250 – 11 or 18 March 1314), also spelled "Molai",Demurger, pp. 1–4. "So no conclusive decision can be reached, and we must stay in the realm of approximations, confining ourselves to placing Molay's date of birth ...

and others were also commanded to appear in person. Molay, however, was already imprisoned in Paris and trials of other Templars were already in progress.

The Council began with a majority of the cardinals and nearly all the members of the Council being of the opinion that the Order of Knights Templar should be granted the right to defend itself. Furthermore, they believed that no proof collected up to then was sufficient to convict the order of the heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

of which Philip accused it. The discussion of Knights Templar was then put on hold.

In February 1312 envoys from the Philip IV negotiated with the Pope, without consulting the Council, and Philip held an assembly in Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

to put further pressure on the Pope and the Council on the topic of the Templars. Philip IV then went to Vienne on 20 March. Clement was forced to adopt the expedient of suppressing the Order of Knights Templar, not by legal methods (''de jure''), but on the grounds of the general welfare of the Church and by Apostolic ordinance (). The Pope then presented to the commission of cardinals (for their approval) the bull to suppress the Templars in (''A voice from on high''), dated 22 March 1312.

The Council, to placate Philip IV of France, condemned the Templars, delivering their wealth in France to him. Delegates for King James II of Aragon insisted the Templar property in Aragon be given to the Order of Calatrava. The bulls of 2 May and of 16 May confiscated Templar property. The fate of the Templars themselves was decided by the bull of 6 May. In the bulls (18 Dec 1312), (31 Dec 1312) and (13 Jan 1313), Clement V dealt with further aspects of the Templars' property.

Church reform

The Council instituted into canon law the ecclesiastical tradition of forbidding clerical marriages. Included in this were punishments for concubinage, rape, fornication, adultery, and incest. Any cleric who broke canon law was deposed, and their marriages ruled invalid.Franciscan rule

Prior to the Council, Ubertino da Casale, formerly a friar atSanta Croce, Florence

The ( Italian for 'Basilica of the Holy Cross') is a minor basilica and the principal Franciscan church of Florence, Italy. It is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce, about 800 metres southeast of the Duomo, on what was once marshland beyond ...

, protested that only a few brethren were following the Rule of Saint Francis

Francis of Assisi founded three orders and gave each of them a special rule. Here, only the rule of the first order is discussed, i.e., that of the Order of Friars Minor.

Origin and contents of the rule

Origin

Whether St. Francis wrote several ...

. These brethren were called spirituals. Upon arrival at the Council, the spirituals, defended by Ubertino of Casale, faced opposition from those that ran the Franciscan order.

At the final session of the council, Clement issued the papal bull reinforcing the previous bull, , which left decisions regarding behaviour and accumulation of wine and grain to the abbot in charge of that monastery.

Disbanding the Beguines

In 1312, the Council and Clement's papal bull, , condemned theBeguines and Beghards

The Beguines () and the Beghards () were Christian lay religious orders that were active in Western Europe, particularly in the Low Countries, in the 13th–16th centuries. Their members lived in semi-monastic communities but did not take for ...

movement, a group of laymen and laywomen that lived in semi-monastic communities, as heretical. According to the Council, members of this movement were deemed heretics because of their antinomian heresy of the "Free Spirit". Following the Council's decision, there were instances where Beghards and Beguines were burned as heretics.

Crusade and Philip IV's vow

A crusade was also discussed as part of the Council. The delegates of theKing of Aragon

This is a list of the kings and queens of Aragon. The Kingdom of Aragon was created sometime between 950 and 1035 when the County of Aragon, which had been acquired by the Kingdom of Navarre in the tenth century, was separated from Navarre in ...

wanted to attack the Muslim city of Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

. In response, the papal vice-chancellor suggested to the Aragonese delegates that the Catalans, now located in Thebes and Athens, should march through the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, also known as Cilician Armenia, Lesser Armenia, Little Armenia or New Armenia, and formerly known as the Armenian Principality of Cilicia, was an Armenian state formed during the High Middle Ages by Armenian ...

to attack the Muslims in the Holy Land. Henry II of Cyprus

Henry II (June 1270 – 31 March 1324) was the last crowned Kingdom of Jerusalem, King of Jerusalem (after the fall of Acre on 28 May 1291, this title became empty) and also ruled as Kingdom of Cyprus, King of Cyprus. He was of the Lusignan ...

' envoys suggested a naval blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are ...

to coincide with an invasion of Egypt.

On 3 April 1312, Philip IV vowed to the council to go on crusade within the next six years. Clement, however, insisted the crusade begin within one year and assigned Philip as its leader. Philip died 29 November 1314, but the crusading tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in money, cash, cheques or v ...

instituted by the church had been spent by the reign of Charles IV of France

Charles IV (18/19 June 1294 – 1 February 1328), called the Fair (''le Bel'') in France and the Bald (''el Calvo'') in Navarre, was the last king of the direct line of the House of Capet, List of French monarchs, King of France and List of Nav ...

.

University chairs

The Council decreed the establishment ofchairs

A chair is a type of seat, typically designed for one person and consisting of one or more legs, a flat or slightly angled seat and a back-rest. It may be made of wood, metal, or synthetic materials, and may be padded or Upholstery, upholstered ...

(professorships) of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

at the Universities of Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

, Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

and Salamanca

Salamanca () is a Municipality of Spain, municipality and city in Spain, capital of the Province of Salamanca, province of the same name, located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is located in the Campo Charro comarca, in the ...

, although the chairs of Arabic were not actually set up. The delegates from Aragon pushed for the creation of an adequate place to teach different languages so as to preach the Gospel to every man.

Canonization of Peter di Murrone

The issue of Pope Celestine V's (Pietro Angelerio) sainthood was brought to the Council. There was division on his canonisation amongst the cardinals; the Colonna contingent voted for his canonization while the Caetera group voted against. Clement assigned a commission of prelates from outside the papal curia to investigate the issue. Clement was still hesitant to canonize Angelerio after the report was completed, until Philip IV's influence forced the issue. Clement waited two years to canonize Pietro Angelerio. Clement used his given name as saint, rather than his papal name of Celestine V refusing to fully surrender to Capetian influence.Aftermath

The Council ended on 6 May 1312. A Parisian chronicler, John of Saint-Victor, stated, "It was said by many that the council was created for the purpose of extorting money." The French ascendancy into the highest echelons of the Church hierarchy became very obvious at the Council. According to the Friedberg edition of the all of Clement's decrees were made at the Council of Vienne.John XXII

Pope John XXII (, , ; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death, in December 1334. He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected by the Conclave of ...

's prefatory letter, however, states Clement combined decrees drafted before and after the meeting at Vienne. In 1312, in anticipation of a revised version of the Council being drafted at the time, Clement ordered that copies of the Vienne decrees that were then in circulation be recalled or burned. The final draft was approved in March 1314, but Clement's death interrupted the distribution of the new copies.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * 262 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

''Catholic Encyclopedia''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Council Of Vienne 1310s in France 1311 in Europe 1312 in Europe 1310s in religion Vienne Vienne Vienne Vienne, Isère Knights Templar Philip IV of France