Cossack Raids on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cossack raids largely developed as a reaction to the

Cossacks launched raids both on the land and sea. Cossack cavalry often picked off wondering Tatars along the north

Cossacks launched raids both on the land and sea. Cossack cavalry often picked off wondering Tatars along the north

When exploring Crimea,

When exploring Crimea,

Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe

Between 1441 and 1774, the Crimean Khanate and the Nogai Horde conducted Slave raiding, slave raids throughout lands primarily controlled by History of Russia, Russia and Polish–Lithuanian union, Poland–Lithuania. Concentrated in Eastern E ...

, which began in 1441 and lasted until 1774. From onwards, the Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

(the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

of southern Ukraine

Southern Ukraine (, ) refers, generally, to the territories in the South of Ukraine.

The territory usually corresponds with the Soviet economical district, the Southern Economical District of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. The region ...

and the Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

of southern Russia

Southern Russia or the South of Russia ( rus, Юг России, p=juk rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a Colloquialism, colloquial term for the southernmost geographic portion of European Russia. The term is generally used to refer to the region of Russia's So ...

) conducted regular military offensives into the lands of the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

, the Nogai Horde

The Nogai Horde was a confederation founded by the Nogais that occupied the Pontic–Caspian steppe from about 1500 until they were pushed west by the Kalmyks and south by the Russians in the 17th century. The Mongol tribe called the Manghuds con ...

, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, where they would free enslaved Christians before returning home with a significant amount of plunder and Muslim slaves

Historically, slavery has been regulated, supported, or opposed on religious grounds.

In Judaism, Hebrew slaves were given a range of treatments and protections. They were to be treated as an extended family with certain protections, and they c ...

. Though difficult to calculate, the level of devastation caused by the Cossack raids is roughly estimated to have been on par with that of the Crimean–Nogai slave raids. According to History of Ruthenians

''History of Ruthenians or Little Russia'' () also known as ''History of the Rus' People'' is an anonymous historico-political treatise, most likely written at the break of the 18th and 19th centuries. It had a great influence on the formation ...

, Cossack raids during Sirko's era were a hundred times more devastating than Crimean–Nogai raids.

Background

The first raid of the Zaporozhian Cossacks was recorded on 1 August, 1492, which was an action against Tatars. During this period the Cossacks were less organised, with their raiding activities resembling those of "guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

" or "steppe sport", with back-and-forth raiding between Cossack and Tatar raiders. Being a Cossack during this period was "more an occupation than a social status", as described by Mykhailo Hrushevsky

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky (; – 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figures of the Ukrainian national revival of the early 20th century. Hrushevsky is ...

. This has first changed in the 1580s, when Cossacks begun to acquire higher social status in their respective states and transformed into regular military formations. From the 1580s and for half of the 17th century, Cossack raids became a major problem for the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

and Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

Cossack raiders were successful in numerous raids due to their efficient adaption of gunpowder weaponry, allowing them to match the Crimean

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrai ...

- Nogai raiders and Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

. Cossacks also made an efficient use of cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during t ...

. Though the Ottoman wars in Europe

A series of military conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and various European states took place from the Late Middle Ages up through the early 20th century. The earliest conflicts began during the Byzantine–Ottoman wars, waged in Anatolia in ...

had enabled their occupation of virtually all of southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well as adjacent regions and Archipelago, archipelagos. There are overlapping and conflicting definitions of t ...

, the Cossacks were not deterred and often pushed to attack deep inside Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, including the Ottoman capital city Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

. The sea raids of Zaporozhians only stopped in 1648, with the outbreak of Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

and formation of the Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate (; Cossack Hetmanate#Name, see other names), officially the Zaporozhian Host (; ), was a Ukrainian Cossacks, Cossack state. Its territory was located mostly in central Ukraine, as well as in parts of Belarus and southwest ...

, but Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

continued sea raiding till 1660s/1670s. By the 18th century, Cossack raids decreased in their intensity, fully ceasing only in 1774 with the end of Crimean-Nogai raids in Eastern Europe.

Conflict and raids

The Cossack conflict with Tatars and Turks was often carried out in parallel with the Russian state. At the same time, these two acted independently of each other in the 16th century. Cossacks preferred an offensive doctrine, while in most cases the Russian state limited itself to passive defensive doctrine.Tatar raids

In early 16th century, Russian state reinforced Oka and Ugra rivers with fortifications and troops, but these were the only defensive measures at the time. The first Crimean raid on Russia took place in 1500–1503. In 1503, Tatars raidedChernigov

Chernihiv (, ; , ) is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within the oblast. Chernihiv's population is

The city was designated as a Hero City of Ukrain ...

, which Russian envoys complained about to the Khan. In 1527, Tatars reached as far as Oka and plundered Ryazan

Ryazan (, ; also Riazan) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Ryazan Oblast, Russia. The city is located on the banks of the Oka River in Central Russia, southeast of Moscow. As of the 2010 C ...

. During 1580–1590, Russian state built defensive fortresses along the southern line of Belgorod

Belgorod (, ) is a city that serves as the administrative center of Belgorod Oblast, Russia, located on the Seversky Donets River, approximately north of the border with Ukraine. It has a population of

It was founded in 1596 as a defensiv ...

, Voronezh

Voronezh ( ; , ) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on the Southeastern Railway, which connects wes ...

, Lebedyan

Lebedyan () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Lebedyansky District in Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, located on the upper Don River (Russia), Don River, northwest of Lipetsk, the administrative center ...

and other cities. However, during 1607–1618, Russia was weakened by turmoil. Tatars took the opportunity to plunder Bolkhov

Bolkhov () is a town and the administrative center of Bolkhovsky District in Oryol Oblast, Russia, located on the Nugr River ( Oka's tributary), from Oryol, the administrative center of the oblast. Population: 12,800 (1969); 20,703 (1897). ...

, Dankov

Dankov () is a town and the administrative center of Dankovsky District in Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, located on the Don River northwest of Lipetsk, the administrative center of the oblast. Population: It was previously known as ''Donkov''.

Histor ...

, Lebedyan, etc. Nearly all of these affected cities were covered by the "defensive line", but this didn't prevent Tatars from raiding them.

In 1632, 20,000 Tatars devastated Yelets

Yelets or Elets () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in Lipetsk Oblast, Russia, situated on the Bystraya Sosna River, which is a tributary of the Don River, Russia, Don. Population:

History

Yelets is the oldest center of the ...

, Karachyev, Livny

Livny (, ) is a town in Oryol Oblast, Russia. As of 2018, it had a population of 47,221. :ru:Ливны#cite note-2018AA-3

History

The town is believed to have originated in 1586 as Ust-Livny, a wooden fort on the bank of the Livenka River, ...

, along with other settlements. In 1633, another 20,000-strong Tatar army devastated Aleksin

Aleksin () is a town and the administrative center of Aleksinsky District in Tula Oblast, Russia, located northwest of Tula, the administrative center of the oblast. Population:

History

It was founded at the end of the 13th century and fir ...

, Kalugu, Kashir, and other towns along the Oka. Even Moskov which was on another side Oka was affected. In 1635, Russian state responded with construction "Belgorod defense line" which was 800km from the Vorskla tributary of the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

, to the Chelnova River. The construction only begun in 1646, taking over 10 years to complete. Tsar Alexis

Alexei Mikhailovich (, ; – ), also known as Alexis, was Tsar of all Russia from 1645 until his death in 1676. He was the second Russian tsar from the House of Romanov.

He was the first tsar to sign laws on his own authority and his council ...

expanded the defensive line to the Crimean border of Russia. Despite these measures, Tatar raiders were hardly deterred, abducting 150,000–200,000 people out of Russia in the first half of the 17th century. In addition, Russian state was forced to pay tribute to the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

every year, averaging 26,000 rubles yearly. Russia paid tribute of 1 million in half of the 17th century. This amount could be used to build 4 new cities by modern calculations.

Cossack raids

Cossacks launched raids both on the land and sea. Cossack cavalry often picked off wondering Tatars along the north

Cossacks launched raids both on the land and sea. Cossack cavalry often picked off wondering Tatars along the north Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

, while plundering Ottoman fortresses on the lower Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

, Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

and Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

. In 1516, Cossacks besieged Ottoman fortress of Akkerman. In 1524, Cossacks first attacked Crimea. In 1545, Cossacks attacked Ochakov

Ochakiv (, ), also known as Ochakov (; ; or, archaically, ) and Alektor (), is a small city in Mykolaiv Raion, Mykolaiv Oblast (region) of southern Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Ochakiv urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. ...

and looted its surroundings, capturing Ottoman delegation on the way.

From third quarter of the 16th century, Cossack influence risen in the Black Sea. Cossacks of Ataman Foka Pokatilo devastated Akkerman. In 1575, Ataman Bogdan launched a campaign into Crimea, as a response to Tatar attacks on Ukrainian lands. Bogdan later launched raids on Kozlov, Trebizond and Sinop. In 1587, Cossacks again devastated Kozlov Akkerman. Ottomans responded to Cossack raids by establishing Azov

Azov (, ), previously known as Azak ( Turki/ Kypchak: ),

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. The population is

History

Early settlements in the vici ...

and Ochakov

Ochakiv (, ), also known as Ochakov (; ; or, archaically, ) and Alektor (), is a small city in Mykolaiv Raion, Mykolaiv Oblast (region) of southern Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Ochakiv urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. ...

fortresses as a defense from Cossack raids. Kizil-Kermen, Tavan and Aslan fortresses were also constructed on the upper Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

and Don region. However, these small fortresses were inefficient in stopping the raiders, with Cossacks learning how to bypass them. The areas of Ochakov

Ochakiv (, ), also known as Ochakov (; ; or, archaically, ) and Alektor (), is a small city in Mykolaiv Raion, Mykolaiv Oblast (region) of southern Ukraine. It hosts the administration of Ochakiv urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. ...

, Tighina

Bender (, ) or Bendery (, ; ), also known as Tighina ( mo-Cyrl, Тигина, links=no), is a city within the internationally recognized borders of Moldova under ''de facto'' control of the unrecognized Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transn ...

, Akkerman and Islam-Kermen were raided by the Zaporozhian Cossacks 4-5 times annually. According to , Zaporozhians conducted over 40 raids, seizing 100,000 cattle, 17,000 horses and 360,000 in złotys during 1570–1580s.

Russian policy and Cossacks

The Russian state first begun assisting Cossacks underIvan IV

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia from 1547 until his death in 1584. ...

, providing them with military supplies. Despite this, Russian policy of trying to appease the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

didn't stop. This policy had no effect and Tatar raids continued, as the Crimean Khans were unwilling to negotiate, unlike their Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

and Swedish counterparts. At one point, the Russian state ordered Cossacks to stop raiding Tatars, with threats on cutting off financial and military support to Cossacks. However, Cossacks ignored these orders most of the time. In response, Russian state carried out their threats on cutting off support, even responding with economic embargo of the Sich

A sich (), was an administrative and military centre of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. The word ''sich'' derives from the Ukrainian verb , "to chop" – with the implication of clearing a forest for an encampment or of building a fortification with t ...

and Don region.

At some points, Russian state even got into armed confrontations with Cossacks, in order to appease the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

and Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. In early 1630, Russian state ordered Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

to stop raiding Tatars and Turks. Don Cossacks were disobedient to these orders and were willing to revolt. However, Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

had minimal connections with the Russian state during this time, acting more recklessly.

Assessment

The inefficiency of Russian doctrine against Tatar raids was attributed to wrong strategy, which sought to appease the raiders and only limited itself to defensive actions, combined with defenses being incapable of stopping the raiders nor inflicting heavy losses on them. Tatar raiders could only be restrained through offensive actions, which were only carried out by the Cossacks on frequent basis. Cossacks didn't limit their actions to passive defense. They've become both the inhabitants and defenders in border areas. Cossacks organised defenses which were efficient in repelling Tatar attacks and responded to losses inflicted by Tatars with retaliatory attacks. In this regard, Cossack doctrine was more efficient in dealing with Tatar raids.Sea raids

Piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

was rare, until Cossacks begun to conduct sea raids. Until the mid-16th century, Ottoman superiority in the sea was undisputed. However, this has changed with frequent sea raids of the Cossacks after 1550s. Ottoman officials viewed the beginning of Cossack sea raiding with a massive concern, as outbreak of banditry

Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, kidnapping, and murder, ...

in the Black Sea. However, Cossacks were a lot more organised unlike petty bandits. Cossacks were capable adapting to harsh frontier conditions and utilize the environment to their use, allowing them to harass an Empire as large as the Ottomans. In addition, Cossack society attracted diverse sets of individuals, from escaped serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

to mercenaries and dissenters of neighbouring Empires, which found an ungoverned Wild Fields

The Wild Fields is a historical term used in the Polish–Lithuanian documents of the 16th to 18th centuries to refer to the Pontic steppe in the territory of present-day Eastern and Southern Ukraine and Western Russia, north of the Black Sea ...

appealing.

For the Cossacks, sea raiding was part of their economic incentive. Cossacks developed a sort of "water culture" due to their location of living near the rivers, combined with their boats named chaikas, which surprisingly resembled upgraded viking ships

Viking ships were marine vessels of unique structure, used in Scandinavia throughout the Middle Ages.

The boat-types were quite varied, depending on what the ship was intended for, but they were generally characterized as being slender and flexi ...

. Cossacks could call up to 300 chaikas for a campaign, which had a higher mobility than Ottoman ships. Cossacks on their chaikas were active in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

.

French military engineer Vasseur de Beauplan provided his account of Cossack sailing:

Impact of sea raids

The need to counter Cossack sea raids, even if it wasn't a complete success, made Ottomans pull a significant amount of their naval forces out of theMediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, weakening their influence. Cossack sea raids also had an economic impact, discouraging trade on Ottoman shore due to risk of Cossack attacks. As explorer Evliya Celebi noted, rural population of Sinop was unwilling to engage in agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

, as they believed their harvest was going to get destroyed during Cossack attacks.

In long-term, Cossack raids had demonstrated that the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, which had conquered southeast Europe centuries prior, wasn't invincible and their era of influence over European affairs was coming to an end. Both European and Ottoman chronicler descriptions of the devastation caused by Cossack sea raids resembled those of Gothic sea attacks on the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

in the 5th century.

Impact

Crimean Khanate and Nogai Horde

When exploring Crimea,

When exploring Crimea, Evliya Çelebi

Dervish Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi (), was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman explorer who travelled through his home country during its cultural zenith as well as neighboring lands. He travelled for over 40 years, rec ...

noted the signs of significant depopulation of many Crimean towns and villages, which he attributed to Cossack raids. In addition to devastation of Tatar lands, Cossack raids also had a deterring effect on Tatar raiders, limiting their ability to devastate Ukrainian lands. Apart from all the demographic, military and economic effects, Cossack raiding also had a psychological effect on the Tatar population, especially during the era of Cossack leader Ivan Sirko

Ivan Dmytrovych Sirko ( – August 11, 1680) was a Zaporozhian Cossack military leader, Koshovyi Otaman of the Zaporozhian Host and putative co-author of the famous semi-legendary Cossack letter to the Ottoman sultan that inspired the major p ...

. Polish chronicler Wespazjan Kochowski noted the following attitude of Tatars surrounding Sirko in Crimea:

Ottoman Empire

Cossack raids inflicted colossal economic losses on theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, resulting in decline of its military power. The Zaporozhian raids during 1672–1674 had the most impactful psychological effect on Turks. Among the most influential Ottoman Sultans reportedly admitted that thinking about Cossacks gave him difficulty sleeping during night.

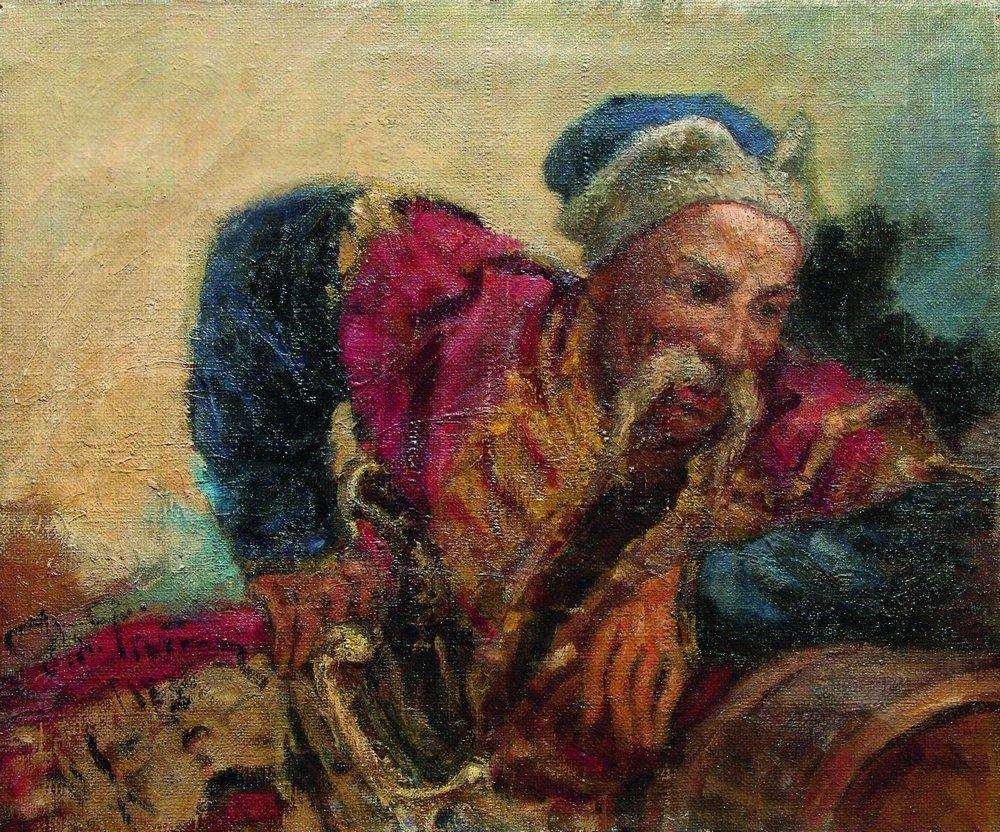

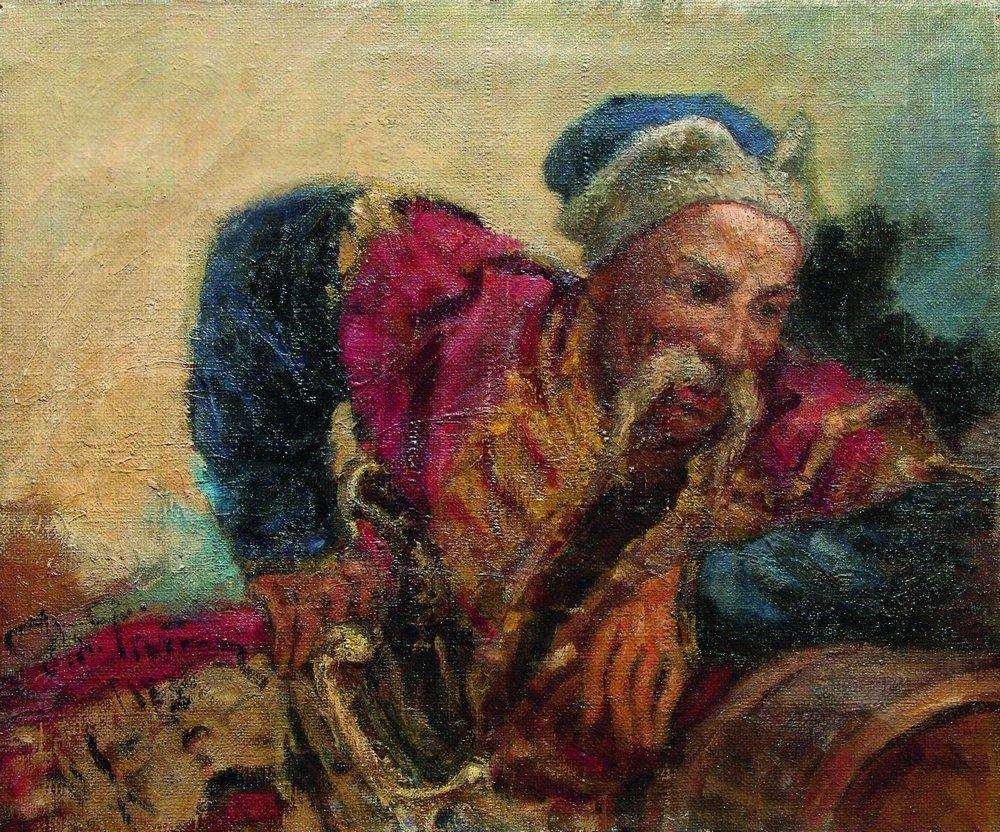

In 1675, Sultan Mehmed IV demanded the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

led by Ivan Sirko

Ivan Dmytrovych Sirko ( – August 11, 1680) was a Zaporozhian Cossack military leader, Koshovyi Otaman of the Zaporozhian Host and putative co-author of the famous semi-legendary Cossack letter to the Ottoman sultan that inspired the major p ...

to submit to the Ottoman rule. To which, Cossacks responded with a semi-legendary letter full of profanities and insults. This inspired most popular painting in Ukrainian-Russian history, Ilya Repin

Ilya Yefimovich Repin ( – 29 September 1930) was a Russian painter, born in what is today Ukraine. He became one of the most renowned artists in Russian Empire, Russia in the 19th century. His major works include ''Barge Haulers on the Volga' ...

's '' Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks''.

Europe

TheZaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

have proven to be more adaptable in comparison to their Tatar counterpart, with their popularity growing in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. In the 16th century, Chevalier commented on them: "there was no warrior better fitted to outfight a Tatar than a Zaporozhian". Ottoman Sultans often sent complaints to the neighbouring states about Zaporozhian attacks, but the rulers of these states declared they have no association with them. Tatars and Turks at times inflict considerable losses on them. In 1593, Tatars burnt Tomakivka Sich while the Cossacks were away. However, Zaporozhian Host again proven their adaptability, as they had no problems with recruitment and building new fleet in a short period of time, only having issues with finding horses. Pope Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII (; ; 24 February 1536 – 3 March 1605), born Ippolito Aldobrandini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 January 1592 to his death in March 1605.

Born in Fano, Papal States to a prominen ...

, even Habsburg Emperors and Polish Kings recognised their efficiency in fighting Ottomans, seeking them as allies. Tsar Feodor I described Zaporozhian Cossacks to the Austrian delegation as: "good fighters, but cruel and treacherous".

Italian Dominican missionary Emidio Portelli d’Ascoli noted about the brutality of Cossack raids:

French military engineer Vasseur de Beauplan expressed the same sentiment:

Incomplete list of Cossack raids

This is an incomplete list of Cossack raids.References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *{{Cite web , first=Михаил , last=Ивануц , title=К вопросу об участии казаков в боевых действиях по осаде и обороне укрепленных пунктов в XVI в. , url=http://dspace.nbuv.gov.ua/handle/123456789/40604 , publisher=Нові дослідження пам’яток козацької доби в Україні: Зб. наук , year=2012 , language=ru Wars involving the Ottoman Empire Crimean Khanate Cossacks Zaporozhian Cossacks History of Ukraine History of Russia Military history of Ukraine Military history of Zaporizhzhia Military history of Russia