Communist Workers' Group (Russia) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Workers Group of the Russian Communist Party () was formed in 1923 to oppose the excessive power of bureaucrats and managers in the new soviet society and in the

Manifesto of the Workers’ Group of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

(February 1923), marxists.org {{Communist Party of the Soviet Union 1923 establishments in the Soviet Union 1930 establishments in the Soviet Union Communist parties in the Soviet Union

Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

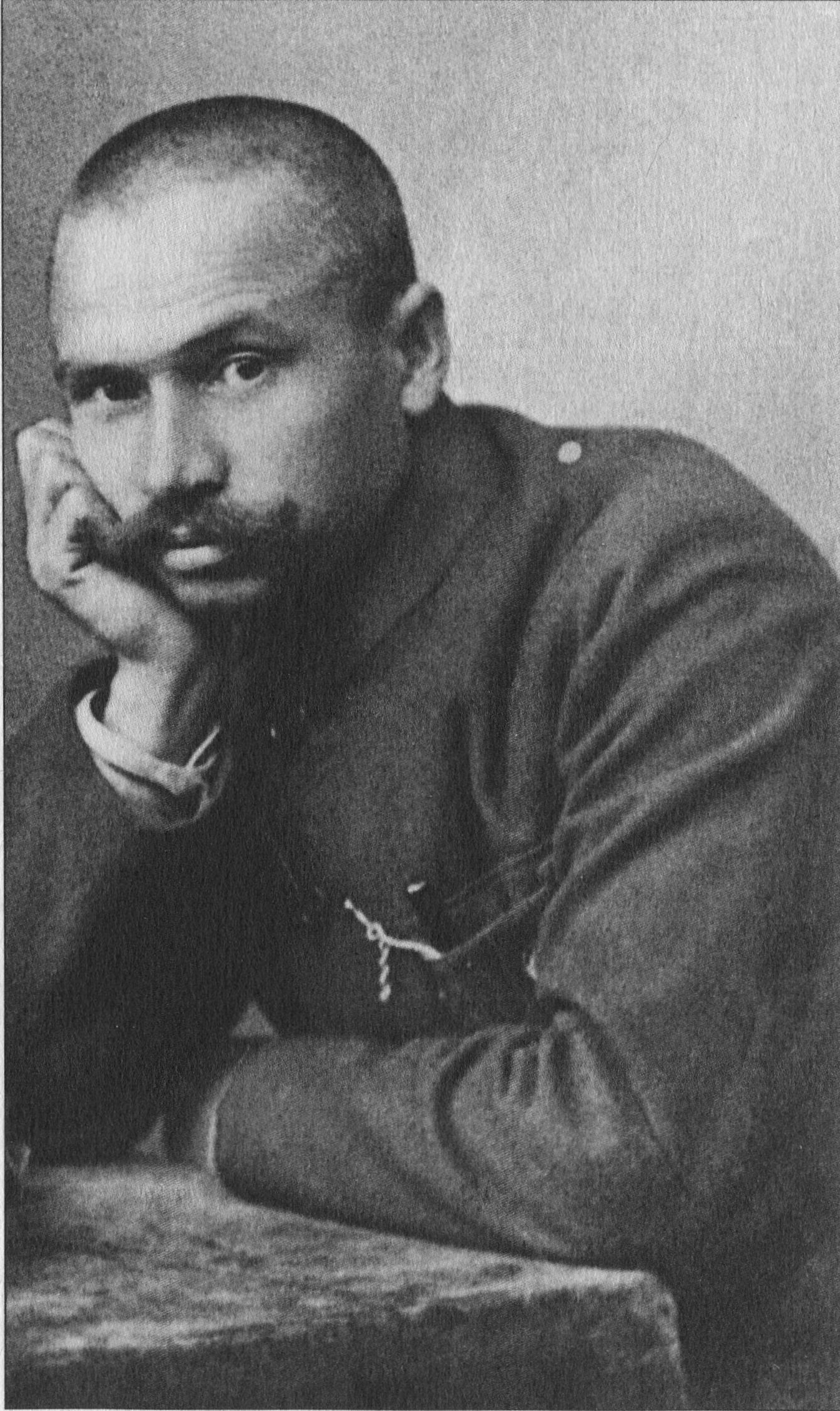

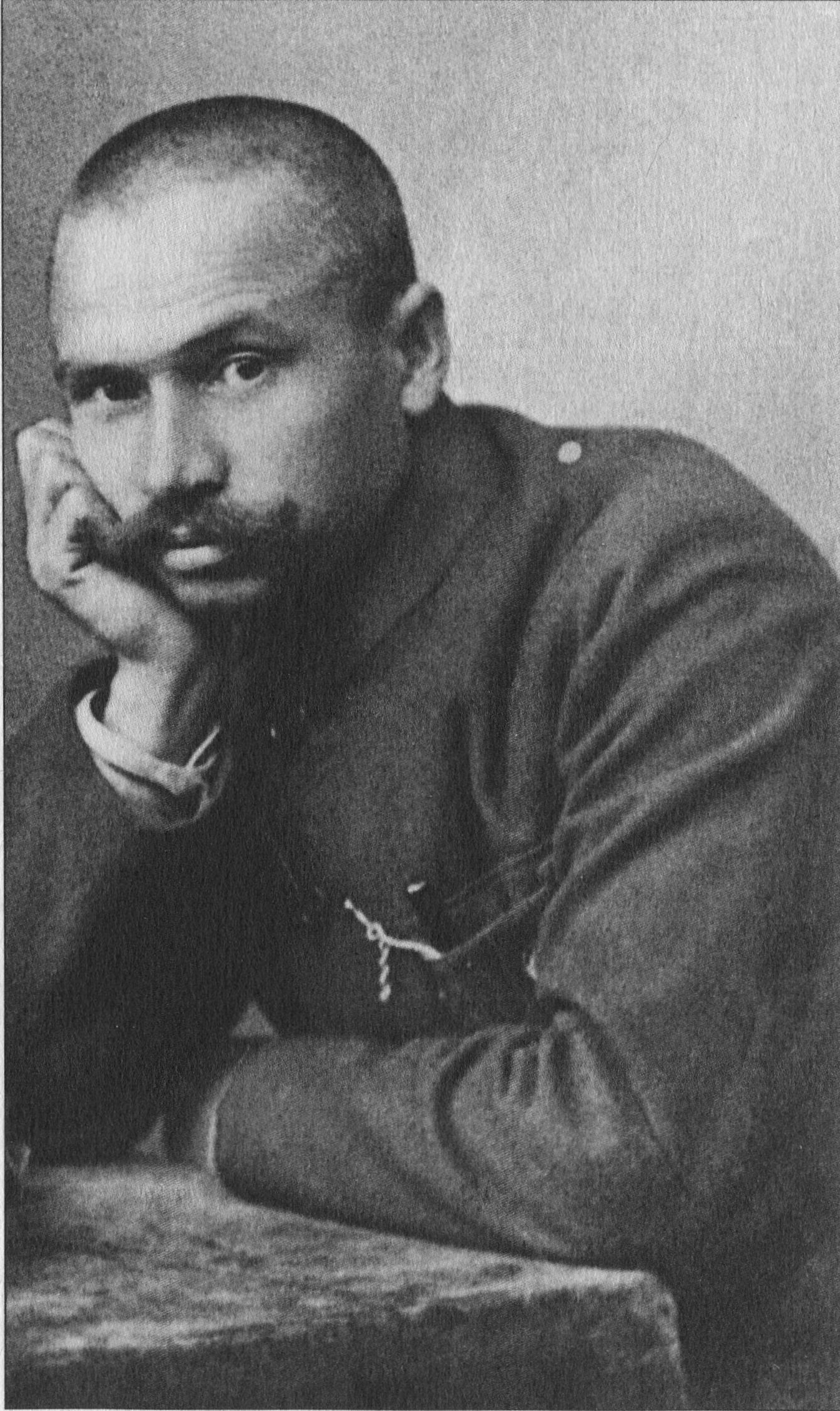

. Its leading member was Gavril Myasnikov

Gavril Ilyich Myasnikov (; February 25, 1889 – November 16, 1945), also transliterated as Gavriil Il'ich Miasnikov, was a Russian Communism, communist revolutionary, a metalworker from the Urals, and one of the first Bolsheviks to oppose and cr ...

.

The Workers Group defended that the Soviet state

The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was the executive and administrative organ of the highest body of state authority, the All-Union Supreme Soviet. It was formed on 30 December 1922 and abolished on 26 December 199 ...

and public enterprises should be run by soviets

The Soviet people () were the citizens and nationals of the Soviet Union. This demonym was presented in the ideology of the country as the "new historical unity of peoples of different nationalities" ().

Nationality policy in the Soviet Union ...

elected from the workplace and that the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

(NEP) was in danger of becoming a "New Exploitation of the Proletariat" if not controlled by the workers' democracy.

Its main activists were arrested in September 1923, and the group's activity was largely suppressed thereafter, although it continued to exist until the 1930s, inside prisons

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where people are imprisoned under the authority of the state, usually as punishment for various cr ...

and possibly also underground.

History

Background

In 1920,Gavril Myasnikov

Gavril Ilyich Myasnikov (; February 25, 1889 – November 16, 1945), also transliterated as Gavriil Il'ich Miasnikov, was a Russian Communism, communist revolutionary, a metalworker from the Urals, and one of the first Bolsheviks to oppose and cr ...

, then head of the Communist Party in Perm

Perm or PERM may refer to:

Places

* Perm, Russia, a city in Russia

**Permsky District, the district

**Perm Krai, a federal subject of Russia since 2005

**Perm Oblast, a former federal subject of Russia 1938–2005

** Perm Governorate, an administr ...

, in the Ural, began to express discontent with aspects of the evolution of the Soviet state, such as the progressive departure of the party leadership from the base militants, the growing number of non-workers in the party and in leading positions and the replacement of workers' control

Workers' control is participation in the management of factories and other commercial enterprises by the people who work there. It has been variously advocated by anarchists, socialists, communists, social democrats, distributists and Christi ...

by " one-man management" in nationalized industries. After the party's 9th Congress, Miasnikov began to openly publicize his criticisms, advocating a return to the program presented by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

in ''The State and Revolution

''The State and Revolution: The Marxist Doctrine of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution'' () is a book written by Vladimir Lenin and published in 1917 which describes his views on the role of the state in society, the ne ...

'': a radically democratic state without a centralized

Centralisation or centralization (American English) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning, decision-making, and framing strategies and policies, become concentrated within a particular ...

bureaucracy

Bureaucracy ( ) is a system of organization where laws or regulatory authority are implemented by civil servants or non-elected officials (most of the time). Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments ...

.

In the autumn of 1920, Miasnikov was transferred to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

, but he soon came into conflict with Grigori Zinoviev and was again sent to the Urals. In 1921, he published a manifesto critical of the party line, advocating an end to the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

, the management of industry by workers' councils

A workers' council, also called labour council, is a type of council in a workplace or a locality made up of workers or of temporary and instantly revocable delegates elected by the workers in a locality's workplaces. In such a system of poli ...

, and unrestricted freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

("from monarchists

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

to anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

"). The provincial party committee forbade him to defend his ideas in public meetings, but Miasnikov disobeyed, and after an exchange of letters with Lenin was expelled from the party in 1922.

The Workers Group

In 1923 Miasnikov (after having his request for readmission to the party rejected) organized the Workers Group, together with N.V. Kuznetsov (also expelled in 1922) and B.P. Moiseev. In February, the Group released its "manifesto", intending to influence the 11th Congress of the Communist Party, which was to be held in April. The text began to be smuggled around the Soviet Union, and by summer the Group had hundreds of adherents (about 300 inMoscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

alone), mostly workers, and many from the Workers' Opposition

The Workers' Opposition () was a faction of the Russian Communist Party that emerged in 1920 as a response to the perceived over-bureaucratisation that was occurring in Soviet Russia. They advocated for the transfer of national economic manage ...

.

Before the 12th Congress 12th Congress may refer to:

* 12th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (1982)

* 12th Congress of the Philippines (2001–2004)

* 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (1923)

* 12th National Congress of the Chines ...

, an anonymous document (most likely authored by Miasnikov) circulated calling for the party to adopt the ideas of the Workers Group manifesto, and for Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

, Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

to be excluded from the Central Committee; however, at the congress the Group's ideas were violently attacked by leading Bolshevik figures such as Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

, Karl Radek

Karl Berngardovich Radek (; 31 October 1885 – 19 May 1939) was a revolutionary and writer active in the Polish and German social democratic movements before World War I and a Communist International leader in the Soviet Union after the Russian ...

and Grigory Zinoviev himself (at that time Lenin was already incapacitated for health reasons), with Miasnikov being arrested shortly thereafter and, in effect, exiled to Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, where he contacted the Communist Workers' Party of Germany

The Communist Workers' Party of Germany (; KAPD) was an anti-parliamentarian and left communist party that was active in Germany during the Weimar Republic. It was founded in 1920 in Heidelberg as a split from the Communist Party of Germany (KP ...

(KAPD), who helped him disseminate the Workers Group manifesto.

In the meantime, in the Soviet Union, the Group was being organized, under the leadership of Moiseev (from now on replaced by I. Makh) and Kuznetsov, and on June 5, 1923, organized a conference in Moscow and elected a Bureau. The Working Group followed a double line of action, since on the one hand its main leaders had been expelled from the Communist Party and the group was beginning to function as a clandestine alternative party, but on the other hand continued to regard itself as a faction of the Communist Party, trying to act as much as possible within it. The Workers' Group militants could be: a) Communist Party militants; b) former militants expelled from the Communist Party for political reasons; c) if they were not affiliated with any party, they were advised to join the Communist Party.

In August and September there was a wave of strikes in Moscow and other cities, apparently spontaneous and without links with opposition groups; the Workers Group planned to seize the occasion and call a general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

and a workers' demonstration (which would be led by a portrait of Lenin), but in September it was the target of widespread repression by the party leadership and the secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

(OGPU

The Joint State Political Directorate ( rus, Объединённое государственное политическое управление, p=ɐbjɪdʲɪˈnʲɵn(ː)əjə ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əjə pəlʲɪˈtʲitɕɪskəjə ʊprɐˈv ...

), with its leaders having been imprisoned, their literature confiscated and their workplaces closed.

Repression and disappearance

After the arrests, twelve members of the Workers Group were expelled from the Communist Party and several others were reprimanded. Miasnikov returned to the Soviet Union at the end of 1923 (having been promised he would be set free) and was immediately arrested, being internally exiled in 1927 toYerevan

Yerevan ( , , ; ; sometimes spelled Erevan) is the capital and largest city of Armenia, as well as one of the world's List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerev ...

, Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

(he would flee the country in 1928, but returned in 1944 to only be arrested in January 1945, and executed in November of the same year).

According to the historian Paul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was an American historian specializing in the 19th and early 20th-century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his ...

, in 1924 the Workers Group had been effectively dismembered; however, according to Ian Hebbes the group would have continued to clandestinely produce manifestos and pamphlets until 1929, and continued to exist until the early 1930s Among Hebbes' sources is the French publication ''L'Ouvrier communiste'', which claimed in 1930 (according to information from Miasnikov, then in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

) that in 1929, in the USSR, activists were accused of being linked to the Workers Group (namely of distributing their newspaper, ''Путь рабочих к власти'' - ) continued to be arrested and expelled from the Communist Party. Also according to the Soviet police interrogation of Miasnikov in 1945, the Workers' Group was still functioning in 1928, and Miasnikov would have frequent meetings in Yerevan with envoys from the group's Central Bureau (it would have even been the Bureau to decide Miasnikov's flight from the USSR, following the illegal publication of his pamphlet ''What is the Workers' State'').

Program

The Workers Group considered that a new oligarchy was being formed, made up of senior Party leaders, company directors, etc. and defended: * the election ofworkers' councils

A workers' council, also called labour council, is a type of council in a workplace or a locality made up of workers or of temporary and instantly revocable delegates elected by the workers in a locality's workplaces. In such a system of poli ...

in all nationalized factories and their participation in management;

* the election of company directors, union leaders and central authorities by the congresses of workers' councils;

* freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

for all manual workers;

* the role of trade unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

in private companies

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in their respective listed markets. Instead, the company's stock is ...

in their function of controlling their managers, namely ensuring compliance with labor laws

Labour laws (also spelled as labor laws), labour code or employment laws are those that mediate the relationship between workers, employing entities, trade unions, and the government. Collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship be ...

and paying taxes;

* autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

and internal democracy in the communist parties of the various nationalities of the Soviet Union;

* the abolition of the Council of People's Commissars

The Council of People's Commissars (CPC) (), commonly known as the ''Sovnarkom'' (), were the highest executive (government), executive authorities of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), the Soviet Union (USSR), and the Sovi ...

and the assignment of its functions to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee () was (June – November 1917) a permanent body formed by the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (held from June 16 to July 7, 1917 in Petrograd), then became the ...

;

* at the international level, refusal of the Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

strategy of alliances

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

with the parties of the Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

and the " 2+1⁄2 International".

Attitude towards the NEP

Although authors likePaul Avrich

Paul Avrich (August 4, 1931 – February 16, 2006) was an American historian specializing in the 19th and early 20th-century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his ...

or John Marot affirmed that the Workers Group considered New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

(NEP) as the "New Exploitation of the Proletariat", which, in its manifesto, defended that the NEP was inevitable given the economic backwardness of the Russia, which, particularly in agriculture, would be heavily dependent on small producers. The expression "New Exploitation of the Proletariat" is referred to as something the NEP was at risk of becoming if not controlled by "proletarian democracy", as it favored the emergence of a privileged group. References that the group presented the NEP as a "new exploitation" seem to have had their origin in the book ''Rabochaia gruppa ("Miasnikovshchina")'', by Vladimir Gordeevich Sorin, published in 1924 and representing the official position of the Communist Party on the faction.

Relationship with other opposition factions

Miasnikov was a "Left Communist

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices held by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they regard ...

" in 1918; later had contacts with the Workers Opposition

The Workers' Opposition () was a faction of the Russian Communist Party that emerged in 1920 as a response to the perceived over-bureaucratisation that was occurring in Soviet Russia. They advocated for the transfer of national economic manage ...

, but without having formally integrated into it, and was one of the subscribers (along with former members of the Workers Opposition, such as Alexander Shliapnikov

Alexander Gavrilovich Shliapnikov (; August 30, 1885 – September 2, 1937) was a Russian communist revolutionary, metalworker, and trade union leader. He is best remembered as a memoirist of the October Revolution of 1917 and as the leader of th ...

and Alexandra Kollontai

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai (; , ; – 9 March 1952) was a Russian revolutionary, politician, diplomat and Marxist theoretician. Serving as the People's Commissar for Welfare in Vladimir Lenin's government in 1917–1918, she was a highl ...

) of the "Charter of the 22", drafted in 1922 advocating more internal democracy and freedom of opinion within the party. In addition, a large part of the militancy of the Workers Group came from the Workers' Opposition, and Kollontai was even invited to participate in a demonstration organized by the group.

The Workers Group manifesto has a critical attitude towards two other opposition groups of the same time: the Democratic Centralists

Democratic centralism is the organisational principle of most communist parties, in which decisions are made by a process of vigorous and open debate amongst party membership, and are subsequently binding upon all members of the party. The con ...

and the Workers' Truth, accusing the former of only being concerned with democracy within the party and not for the proletariat, and the latter of actually accepting and promoting the restoration of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

.

Later, the Workers' Group approached some of the other factions: in August 1928, the Workers' Group held a conference in Moscow where it approved an appeal to the "Group of 15" (a faction derived from the Group of Democratic Centralism) and to the remnants of the Workers' Opposition to adopt a common program, and where a proposal of statutes for a "Workers' Communist Party" was discussed bringing together the Workers' Group and the Group of 15. In the 1930s, in the Vorkuta labor camp, it was constituted a "Federation of Left Communists" bringing together prisoners from the Workers' Group, Democratic Centralists and some Trotskyists

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as a ...

.

Already in exile, Miasnikov established links with Trotsky (who had attacked him in the early 1920s, but who in the meantime came to defend very similar positions regarding internal party democracy and the strategy of the Communist International, albeit in disagreement with regard to the nature of the Soviet Union, which for Trotsky continued to be a "workers' state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. This article is about states that refer to themselves as socialist states, and not specifically abo ...

", while Miasnikov considered it to be "State Capitalist

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes business and commercial economic activity and where the means of production are nationalized as state-owned enterprises (including the processes of capital accumulation, ce ...

").

International alignment

The Workers' Group was linked to theCommunist Workers' Party of Germany

The Communist Workers' Party of Germany (; KAPD) was an anti-parliamentarian and left communist party that was active in Germany during the Weimar Republic. It was founded in 1920 in Heidelberg as a split from the Communist Party of Germany (KP ...

(KAPD) and the Communist Workers' International

The Communist Workers' International (, KAI) or Fourth Communist International was a council communist international. It was founded around the ''Manifesto of the Fourth Communist International'', published by the Communist Workers' Party of ...

(KAI); but it would later break with the KAI for refusing any united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

with the parties of the Communist International, in counterpoint to the Workers Group's line of continuing to work within the Soviet Communist Party.

Around 1930, Miasnikov, in exile, and the Workers' Group (so far as it still existed as an organization) were associated with the "Communist Workers' Groups" in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and with their newspaper ''L'Ouvrier Communiste'', a dissident group of Bordigism

Amadeo Bordiga (13 June 1889 – 25 July 1970) was an Italian Marxist theorist. A revolutionary socialist, Bordiga was the founder of the Communist Party of Italy (PCdI), a member of the Communist International (Comintern), and later a leading ...

however ideologically aligned with the German and Dutch tradition of the Communist left

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices held by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they regard ...

.

References

Bibliography

* * * *External links

Manifesto of the Workers’ Group of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

(February 1923), marxists.org {{Communist Party of the Soviet Union 1923 establishments in the Soviet Union 1930 establishments in the Soviet Union Communist parties in the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

Council communist organizations

Factions in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Left communism in the Soviet Union

Left communist organizations

Soviet opposition groups