The Cold War was a period of global

geopolitical

Geopolitics () is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of states: ''de facto'' independen ...

rivalry between the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

(US) and the

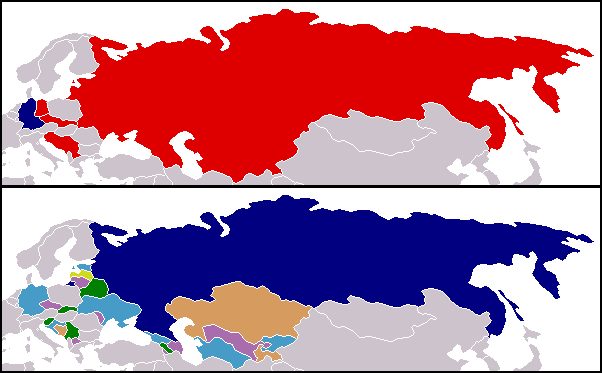

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

(USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist

Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Capitalist Bloc, the Freedom Bloc, the Free Bloc, and the American Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War (1947–1991). While ...

and communist

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

, which lasted from 1947 until the

dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

in 1991. The term ''

cold war

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

'' is used because there was no direct fighting between the two

superpower

Superpower describes a sovereign state or supranational union that holds a dominant position characterized by the ability to Sphere of influence, exert influence and Power projection, project power on a global scale. This is done through the comb ...

s, though each supported opposing sides in regional conflicts known as

proxy war

In political science, a proxy war is an armed conflict where at least one of the belligerents is directed or supported by an external third-party power. In the term ''proxy war'', a belligerent with external support is the ''proxy''; both bel ...

s. In addition to the struggle for ideological and economic influence and an

arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more State (polity), states to have superior armed forces, concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

in both conventional and

nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (thermonuclear weap ...

, the Cold War was expressed through technological rivalries such as the

Space Race

The Space Race (, ) was a 20th-century competition between the Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between t ...

,

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

,

propaganda campaign

White propaganda is propaganda that does not hide its origin or nature. It is the most common type of propaganda and is distinguished from black propaganda which disguises its origin to discredit an opposing cause.

It typically uses standard pu ...

s,

embargoes, and

sports diplomacy

Sport is a physical activity or game, often competitive and organized, that maintains or improves physical ability and skills. Sport may provide enjoyment to participants and entertainment to spectators. The number of participants in a par ...

.

After the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in 1945, during which the US and USSR had been allies, the USSR installed

satellite governments in its occupied territories in Eastern Europe and

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

by 1949, resulting in the political division of Europe (and Germany) by an "

Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

". The USSR tested

its first nuclear weapon in 1949, four years after their use by the US

at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and allied with the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, founded in 1949. The US declared the

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

of "

containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

" of communism in 1947, launched the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

in 1948 to assist Western Europe's economic recovery, and founded the

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

military alliance in 1949 (matched by the Soviet-led

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

in 1955). The

Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, roa ...

of 1948 to 1949 was an early confrontation, as was the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

of 1950 to 1953, which ended in a stalemate.

US involvement in regime change during the Cold War included support for

anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

and

right-wing dictatorship

A right-wing dictatorship, sometimes also referred to as a rightist dictatorship or right-wing authoritarianism, is an authoritarian or sometimes totalitarian regime following right-wing policies. Right-wing dictatorships are typically characteri ...

s and uprisings, while

Soviet involvement included the funding of

left-wing parties,

wars of independence, and dictatorships. As nearly all the colonial states underwent

decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

, many became

Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

battlefields of the Cold War. Both powers used economic aid in an attempt to win the loyalty of

non-aligned countries. The

Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution () was the military and political movement that overthrew the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, who had ruled Cuba from 1952 to 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, in which Batista overthrew ...

of 1959 installed the first communist regime in the Western Hemisphere, and in 1962, the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

began after deployments of US missiles in Europe and Soviet missiles in Cuba; it is widely considered

the closest the Cold War came to escalating into

nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a War, military conflict or prepared Policy, political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are Weapon of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conven ...

. Another major proxy conflict was the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

of 1955 to 1975, which ended in defeat for the US.

The USSR solidified its domination of Eastern Europe with its crushing of the

Hungarian Revolution in 1956 and the

Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

On 20–21 August 1968, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four fellow Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, and the Hungarian People's Republic. The ...

in 1968. Relations between the USSR and China broke down by 1961, with the

Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual worsening of relations between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the Cold War. This was primarily caused by divergences that arose from their ...

bringing the two states to the brink of war amid

a border conflict in 1969. In 1972,

the US initiated diplomatic contacts with China and the US and USSR signed a series of treaties limiting their nuclear arsenals during a period known as

détente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

. In 1979, the toppling of US-allied governments in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and

Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

and the outbreak of the

Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War took place in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from December 1979 to February 1989. Marking the beginning of the 46-year-long Afghan conflict, it saw the Soviet Union and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic o ...

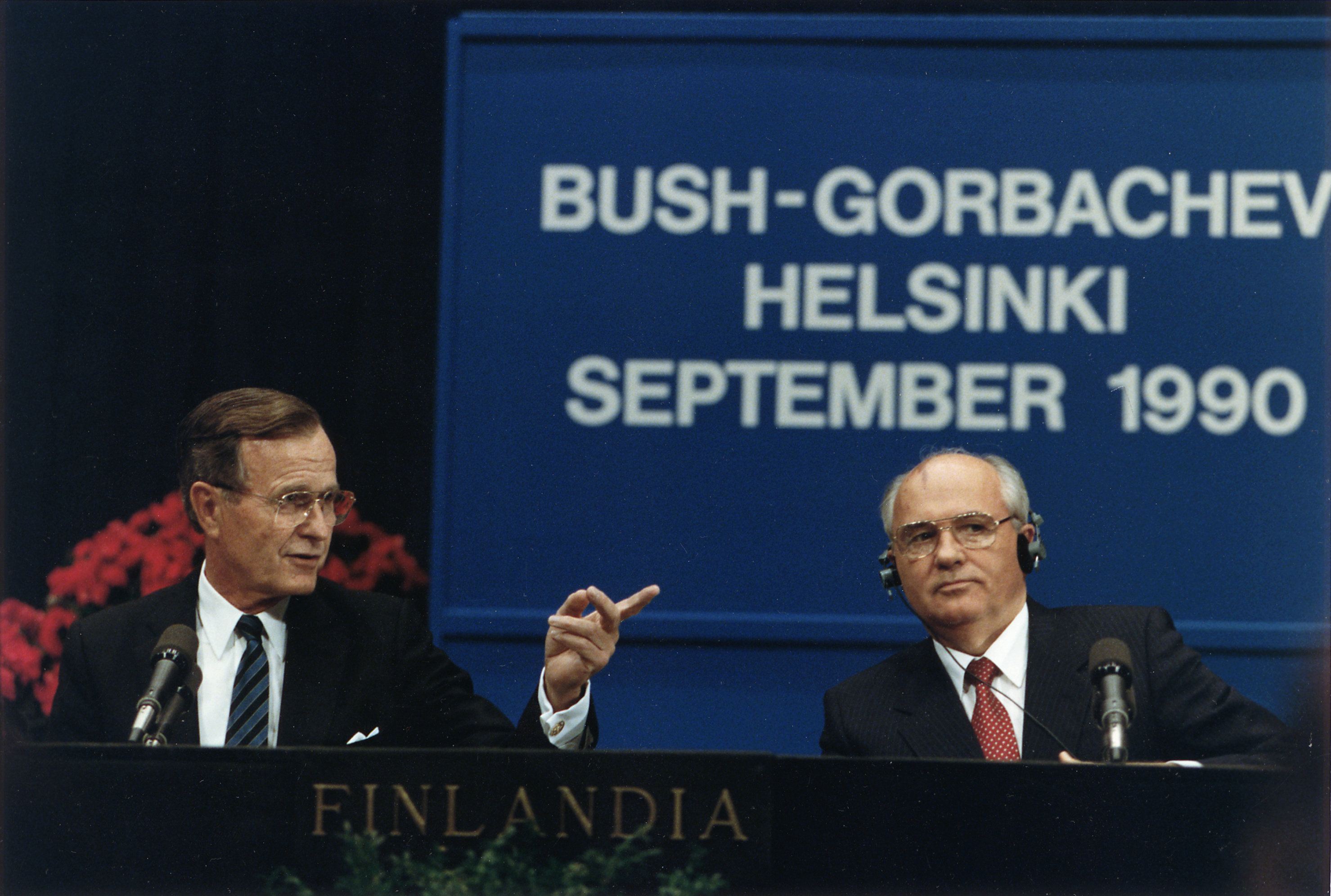

again raised tensions. In 1985,

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

became leader of the USSR and expanded political freedoms, which contributed to the

revolutions of 1989

The revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, were a revolutionary wave of liberal democracy movements that resulted in the collapse of most Communist state, Marxist–Leninist governments in the Eastern Bloc and other parts ...

in the Eastern Bloc and the

collapse of the USSR in 1991, ending the Cold War.

Terminology

Writer

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

used ''

cold war

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

'', as a general term, in his essay "You and the Atomic Bomb", published 19 October 1945. Contemplating a world living in the shadow of the threat of

nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a War, military conflict or prepared Policy, political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are Weapon of mass destruction, weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conven ...

, Orwell looked at

James Burnham

James Burnham (November 22, 1905 – July 28, 1987) was an American philosopher and political theorist. He chaired the New York University Department of Philosophy.

His first book was ''An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis'' (1931). Bur ...

's predictions of a polarized world, writing:

In ''

The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. First published in 1791, it is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.

In 1993 it was acquired by Guardian Media Group Limited, and operated as a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' ...

'' of 10 March 1946, Orwell wrote, "after the Moscow conference last December, Russia began to make a 'cold war' on Britain and the British Empire."

The first use of the term to describe the specific

post-war

A post-war or postwar period is the interval immediately following the end of a war. The term usually refers to a varying period of time after World War II, which ended in 1945. A post-war period can become an interwar period or interbellum, ...

geopolitical confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States came in a speech by

Bernard Baruch

Bernard Mannes Baruch (August 19, 1870 – June 20, 1965) was an American financier and statesman.

After amassing a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange, he impressed President Woodrow Wilson by managing the nation's economic mobilization in W ...

, an influential advisor to Democratic presidents, on 16 April 1947. The speech, written by journalist

Herbert Bayard Swope

Herbert Bayard Swope Sr. (; January 5, 1882 – June 20, 1958) was an American editor, journalist and intimate of the Algonquin Round Table. Swope spent most of his career at the ''New York World.'' He was the first and three-time recipient of t ...

, proclaimed, "we are today in the midst of a cold war." Newspaper columnist

Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter, and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of the Cold War, coining t ...

gave the term wide currency with his book ''The Cold War''. When asked in 1947 about the source of the term, Lippmann traced it to a French term from the 1930s, .

Background and periodization

The roots of the Cold War can be traced to diplomatic and military tensions preceding World War II. The 1917

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

and the subsequent

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

, where Soviet Russia ceded vast territories to Germany, deepened distrust among the Western Allies. Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War further complicated relations, and although the Soviet Union later allied with Western powers to defeat

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, this cooperation was strained by mutual suspicions.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, disagreements about the future of Europe, particularly

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

, became central. The Soviet Union's establishment of communist regimes in the countries it had liberated from Nazi control—enforced by the presence of the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

—alarmed the US and UK. Western leaders saw this as Soviet expansionism, clashing with their vision of a democratic Europe. Economically, the divide was sharpened with the introduction of the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

in 1947, a US initiative to provide financial aid to rebuild Europe and prevent the spread of communism by stabilizing capitalist economies. The Soviet Union rejected the Marshall Plan, seeing it as an effort by the US to impose its influence on Europe. In response, the Soviet Union established

Comecon

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, often abbreviated as Comecon ( ) or CMEA, was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc#List of states, Easter ...

(Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) to foster economic cooperation among communist states.

The United States and its

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

an allies sought to strengthen their bonds and used the policy of

containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

against Soviet influence; they accomplished this most notably through the formation of

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

, which was essentially a defensive agreement in 1949. The Soviet Union countered with the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

in 1955, which had similar results with the Eastern Bloc. As by that time the Soviet Union already had an armed presence and political domination all over its eastern satellite states, the pact has been long considered superfluous. Although nominally a defensive alliance, the Warsaw Pact's primary function was to safeguard

Soviet hegemony over its

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

an satellites, with the pact's only direct military actions having been the invasions of its own member states to keep them from breaking away; in the 1960s, the pact evolved into a multilateral alliance, in which the non-Soviet Warsaw Pact members gained significant scope to pursue their own interests. In 1961, Soviet-allied

East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

constructed the

Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (, ) was a guarded concrete Separation barrier, barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and the East Germany, German Democratic Republic (GDR; East Germany). Construction of the B ...

to prevent the citizens of

East Berlin

East Berlin (; ) was the partially recognised capital city, capital of East Germany (GDR) from 1949 to 1990. From 1945, it was the Allied occupation zones in Germany, Soviet occupation sector of Berlin. The American, British, and French se ...

from fleeing to

West Berlin

West Berlin ( or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin from 1948 until 1990, during the Cold War. Although West Berlin lacked any sovereignty and was under military occupation until German reunification in 1 ...

, at the time part of United States-allied

West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

. Major crises of this phase included the

Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, roa ...

of 1948–1949, the

Chinese Communist Revolution

The Chinese Communist Revolution was a social revolution, social and political revolution in China that began in 1927 and culminated with the proclamation of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. The revolution was led by the Chinese C ...

of 1945–1949, the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

of 1950–1953, the

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 4 November 1956; ), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was an attempted countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the policies caused by ...

and the

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

of that same year, the

Berlin Crisis of 1961

The Berlin Crisis of 1961 () was the last major European political and military incident of the Cold War concerning the status of the German capital city, Berlin, and of History of Germany (1945–90), post–World War II Germany. The crisis cul ...

, the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

of 1962, and the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

of 1955–1975. Both superpowers competed for influence in

Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

and the

Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, and the decolonising states of

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

,

Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, and

Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

.

Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, this phase of the Cold War saw the

Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual worsening of relations between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the Cold War. This was primarily caused by divergences that arose from their ...

. Between China and the Soviet Union's complicated relations within the Communist sphere, leading to the

Sino-Soviet border conflict

The Sino-Soviet border conflict, also known as the Sino-Soviet crisis, was a seven-month undeclared military conflict between the Soviet Union and China in 1969, following the Sino-Soviet split. The most serious border clash, which brought th ...

, while France, a Western Bloc state, began to demand greater autonomy of action. The

Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

On 20–21 August 1968, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four fellow Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, and the Hungarian People's Republic. The ...

occurred to suppress the

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (; ) was a period of liberalization, political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected Secretary (title), First Secre ...

of 1968, while the United States experienced internal turmoil from the

civil rights movement and

opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War began in 1965 with demonstrations against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War, United States in the war. Over the next several years, these demonstrations grew ...

. In the 1960s–1970s, an international

peace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world pe ...

took root among citizens around the world. Movements against

nuclear weapons testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the performance of nuclear weapons and the effects of Nuclear explosion, their explosion. Nuclear testing is a sensitive political issue. Governments have often performed tests to si ...

and for

nuclear disarmament

Nuclear disarmament is the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons. Its end state can also be a nuclear-weapons-free world, in which nuclear weapons are completely eliminated. The term ''denuclearization'' is also used to describe the pro ...

took place, with large

anti-war protests. By the 1970s, both sides had started making allowances for peace and security, ushering in a period of

détente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

that saw the

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds of ...

and the

1972 visit by Richard Nixon to China that opened relations with China as a strategic counterweight to the Soviet Union. A number of self-proclaimed

Marxist–Leninist governments were formed in the second half of the 1970s in

developing countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed Secondary sector of the economy, industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. ...

, including

Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

,

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

,

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

,

Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

,

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

, and

Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

.

Détente collapsed at the end of the decade with the beginning of the

Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War took place in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from December 1979 to February 1989. Marking the beginning of the 46-year-long Afghan conflict, it saw the Soviet Union and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic o ...

in 1979. Beginning in the 1980s, this phase was another period of elevated tension. The

Reagan Doctrine led to increased diplomatic, military, and economic pressures on the Soviet Union, which at the time was undergoing the

Era of Stagnation

The "Era of Stagnation" (, or ) is a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in order to describe the negative way in which he viewed the economic, political, and social policies of the Soviet Union that began during the rule of Leonid Brezhnev (1964 ...

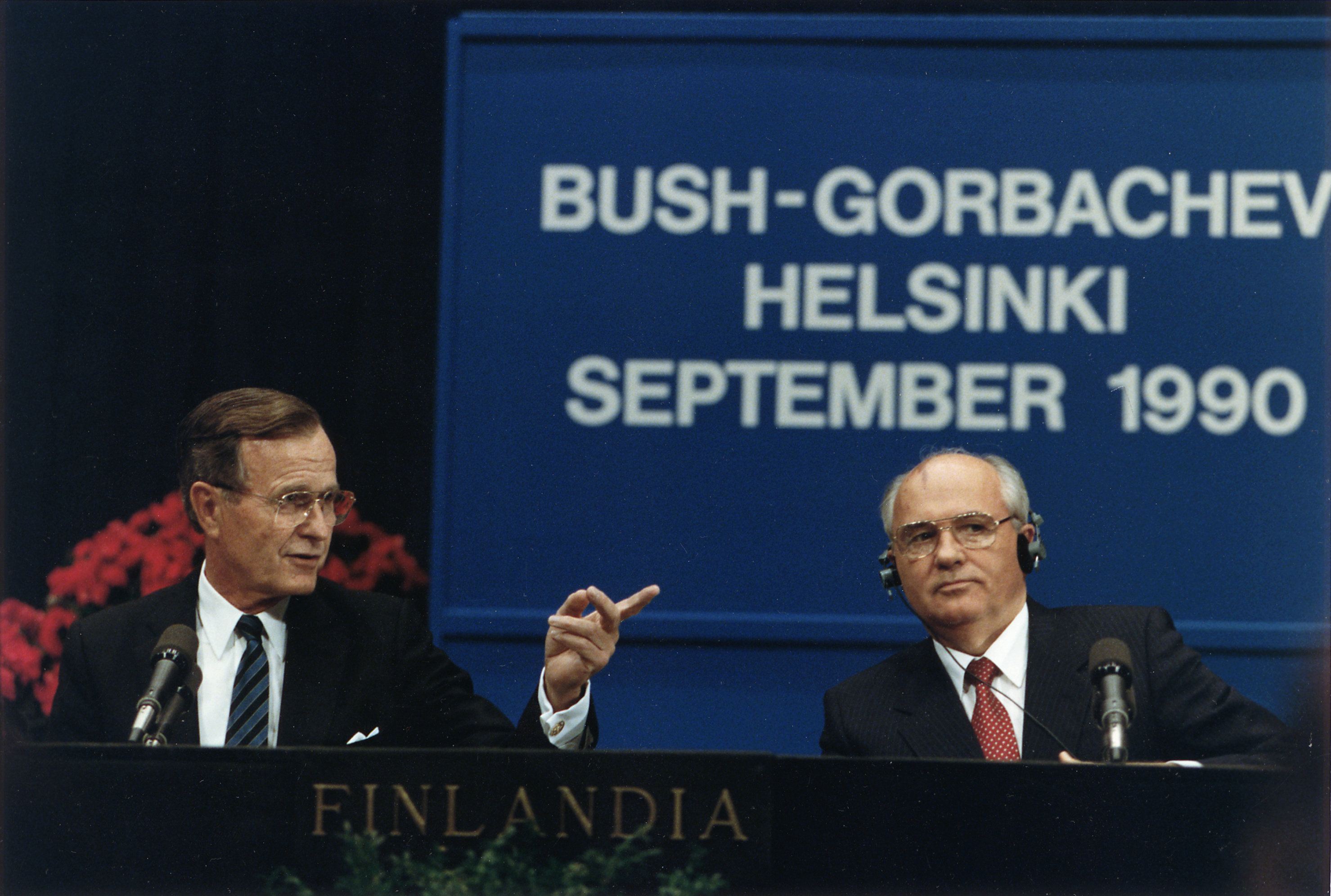

. This phase saw the new Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

introducing the liberalizing reforms of ''

glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

'' ("openness") and ''

perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

'' ("reorganization") and ending Soviet involvement in Afghanistan in 1989. Pressures for national sovereignty grew stronger in Eastern Europe, and Gorbachev refused to further support the Communist governments militarily.

The fall of the

Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

after the

Pan-European Picnic

The Pan-European Picnic (; ; ; ) was a peace demonstration held on the Austro- Hungarian border near Sopron, Hungary on 19 August 1989. The opening of the border gate between Austria and Hungary at the Pan-European Picnic was an event in the ...

and the

Revolutions of 1989

The revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, were a revolutionary wave of liberal democracy movements that resulted in the collapse of most Communist state, Marxist–Leninist governments in the Eastern Bloc and other parts ...

, which represented a peaceful revolutionary wave with the exception of the

Romanian revolution

The Romanian revolution () was a period of violent Civil disorder, civil unrest in Socialist Republic of Romania, Romania during December 1989 as a part of the revolutions of 1989 that occurred in several countries around the world, primarily ...

and the

Afghan Civil War (1989–1992)

The Afghan Civil War of 1989–1992 (Pashto: له ۱۹۸۹ څخه تر ۱۹۹۲ پوري د افغانستان کورنۍ جګړه) took place between the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan and the end of the Soviet–Afghan War on 15 February 1 ...

, overthrew almost all of the Marxist–Leninist regimes of the Eastern Bloc. The

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

itself lost control in the country and was banned following the

1991 Soviet coup attempt

The 1991 Soviet coup attempt, also known as the August Coup, was a failed attempt by hardliners of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) to Coup d'état, forcibly seize control of the country from Mikhail Gorbachev, who was President ...

that August. This in turn led to the formal

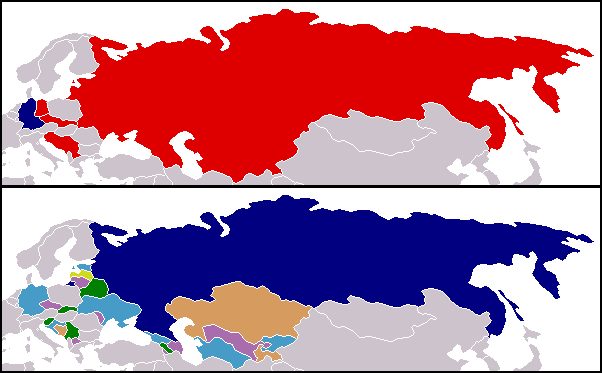

dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

in December 1991 and the collapse of Communist governments across much of Africa and Asia. The

Russian Federation

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

became the Soviet Union's successor state, while many of the other republics emerged as fully independent

post-Soviet states

The post-Soviet states, also referred to as the former Soviet Union or the former Soviet republics, are the independent sovereign states that emerged/re-emerged from the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Prior to their independence, they ...

.

The United States was left as the world's sole superpower.

Containment, Truman Doctrine, Korean War (1947–1953)

Iron Curtain, Iran, Turkey, Greece, and Poland

In February 1946,

George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

's "

Long Telegram" from Moscow to Washington helped to articulate the US government's increasingly hard line against the Soviets, which would become the basis for US strategy toward the Soviet Union. The telegram galvanized a policy debate that would eventually shape the

Truman administration

Harry S. Truman's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 33rd president of the United States began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been Vice President ...

's Soviet policy. Washington's opposition to the Soviets accumulated after broken promises by Stalin and

Molotov concerning Europe and Iran. Following the World War II

Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran

The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran, also known as the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Persia, was the joint invasion of the neutral Imperial State of Iran by the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union in August 1941. The two powers announced that they w ...

, the country was occupied by the Red Army in the far north and the British in the south. Iran was used by the United States and British to supply the Soviet Union, and the Allies agreed to withdraw from Iran within six months after the cessation of hostilities. However, when this deadline came, the Soviets remained in Iran under the guise of the

Azerbaijan People's Government

The Azerbaijan People's Government (; ) was a short-lived unrecognized secessionist state in northern Iran from November 1945 to December 1946. Like the unrecognized Republic of Mahabad, it was a puppet state of the Soviet Union. Established i ...

and

Kurdish Republic of Mahabad

The Republic of Mahabad, also referred to as the Republic of Kurdistan (; ), was a short-lived Kurdish self-governing unrecognized state in present-day Iran, from 22 January to 15 December 1946. The Republic of Mahabad, a puppet state of the ...

. On 5 March, former British prime minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "

Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

" speech calling for an Anglo-American alliance against the Soviets, whom he accused of establishing an "iron curtain" dividing Europe.

A week later, on 13 March, Stalin responded vigorously to the speech, saying Churchill could be compared to

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

insofar as he advocated the racial superiority of

English-speaking nations so that they could satisfy their hunger for world domination, and that such a declaration was "a call for war on the USSR." The Soviet leader also dismissed the accusation that the USSR was exerting increasing control over the countries lying in its sphere. He argued that there was nothing surprising in "the fact that the Soviet Union, anxious for its future safety,

astrying to see to it that governments loyal in their attitude to the Soviet Union should exist in these countries."

Soviet territorial demands to Turkey regarding the Dardanelles in the

Turkish Straits crisis

The Turkish Straits crisis was a Cold War-era territorial conflict between the Soviet Union and Turkey. Turkey had remained officially Neutral powers during World War II, neutral throughout most of the Second World War. After the war ended, Turk ...

and Black Sea

border disputes were also a major factor in increasing tensions. In September, the Soviet side produced the

Novikov telegram, sent by the Soviet ambassador to the US but commissioned and "co-authored" by

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov (; – 8 November 1986) was a Soviet politician, diplomat, and revolutionary who was a leading figure in the government of the Soviet Union from the 1920s to the 1950s, as one of Joseph Stalin's closest allies. ...

; it portrayed the US as being in the grip of monopoly capitalists who were building up military capability "to prepare the conditions for winning world supremacy in a new war". On 6 September 1946,

James F. Byrnes delivered a

speech

Speech is the use of the human voice as a medium for language. Spoken language combines vowel and consonant sounds to form units of meaning like words, which belong to a language's lexicon. There are many different intentional speech acts, suc ...

in Germany repudiating the

Morgenthau Plan

The Morgenthau Plan was a proposal to weaken Germany following World War II by eliminating its arms industry and removing or destroying other key industries basic to military strength. This included the removal or destruction of all industria ...

(a proposal to partition and de-industrialize post-war Germany) and warning the Soviets that the US intended to maintain a military presence in Europe indefinitely. As Byrnes stated a month later, "The nub of our program was to win the German people ... it was a battle between us and Russia over minds ..." In December, the Soviets agreed to withdraw from Iran after persistent US pressure, an early success of containment policy.

By 1947, US president

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

was outraged by the perceived resistance of the Soviet Union to American demands in Iran, Turkey, and Greece, as well as Soviet rejection of the

Baruch Plan

The Baruch Plan was a proposal put forward by the United States government on 14 June 1946 to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC) during its first meeting. Bernard Baruch wrote the bulk of the proposal, based on the March 1946 Ac ...

on nuclear weapons. In February 1947, the British government announced that it could no longer afford to finance the

Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

in

its civil war against Communist-led insurgents. In the same month, Stalin conducted the rigged

1947 Polish legislative election

Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on 19 January 1947,Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1491 the first since World War II. According to the official results, the Democratic Bloc (Poland), D ...

which constituted an open breach of the

Yalta Agreement. The

US government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, execut ...

responded by adopting a policy of

containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

, with the goal of stopping the spread of

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

. Truman delivered a speech calling for the allocation of $400 million to intervene in the war and unveiled the

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

, which framed the conflict as a contest between free peoples and

totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

regimes. American policymakers accused the Soviet Union of conspiring against the Greek royalists in an effort to

expand Soviet influence even though Stalin had told the Communist Party to cooperate with the British-backed government.

Enunciation of the Truman Doctrine marked the beginning of a US bipartisan defense and foreign policy consensus between

Republicans and

Democrats focused on containment and

deterrence that weakened during and after the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, but ultimately persisted thereafter. Moderate and conservative parties in Europe, as well as social democrats, gave virtually unconditional support to the Western alliance, while

European and

American Communists

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, ...

, financed by the

KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

and involved in its intelligence operations, adhered to Moscow's line, although dissent began to appear after 1956. Other critiques of the consensus policy came from

anti-Vietnam War activists, the

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nucl ...

, and the

anti-nuclear movement

The Anti-nuclear war movement is a new social movements, social movement that opposes various nuclear technology, nuclear technologies. Some direct action groups, environmental movements, and professional organisations have identified them ...

.

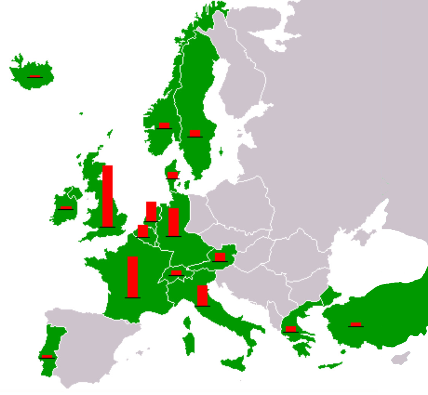

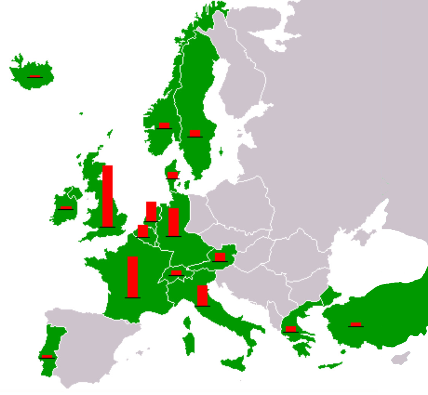

Marshall Plan, Czechoslovak coup and formation of two German states

In early 1947, France, Britain and the United States unsuccessfully attempted to reach an agreement with the Soviet Union for a plan envisioning an economically self-sufficient Germany, including a detailed accounting of the industrial plants, goods and infrastructure already taken by the Soviets. In June 1947, in accordance with the

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

, the United States enacted the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

, a pledge of economic assistance for all European countries willing to participate. Under the plan, which President Harry S. Truman signed on 3 April 1948, the US government gave to Western European countries over $13 billion (equivalent to $189 billion in 2016). Later, the program led to the creation of the

OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; , OCDE) is an international organization, intergovernmental organization with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and international trade, wor ...

.

The plan's aim was to rebuild the democratic and economic systems of Europe and to counter perceived threats to the

European balance of power, such as communist parties seizing control. The plan also stated that European prosperity was contingent upon German economic recovery. One month later, Truman signed the

National Security Act of 1947

The National Security Act of 1947 (Act of Congress, Pub.L.]80-253 61 United States Statutes at Large, Stat.]495 enacted July 26, 1947) was a law enacting major restructuring of the Federal government of the United States, United States governmen ...

, creating a unified

United States Department of Defense, Department of Defense, the

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

(CIA), and the

National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

(NSC). These would become the main bureaucracies for US defense policy in the Cold War.

Stalin believed economic integration with the West would allow

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

countries to escape Soviet control, and that the US was trying to buy a pro-US re-alignment of Europe. Stalin therefore prevented Eastern Bloc nations from receiving Marshall Plan aid. The Soviet Union's alternative to the Marshall Plan, which was purported to involve Soviet subsidies and trade with central and eastern Europe, became known as the

Molotov Plan

The Molotov Plan was the system created by the Soviet Union in order to provide aid to rebuild the countries in Eastern Europe that were politically and economically aligned to the Soviet Union. It was called the "Brother Plan" in the Soviet Unio ...

(later institutionalized in January 1949 as the

Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, often abbreviated as Comecon ( ) or CMEA, was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc along with a number of ...

). Stalin was also fearful of a reconstituted Germany; his vision of a post-war Germany did not include the ability to rearm or pose any kind of threat to the Soviet Union.

In early 1948, Czech Communists executed a

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

in

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

(resulting in the formation of the

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, (Czech language, Czech and Slovak language, Slovak: ''Československá socialistická republika'', ČSSR) known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic (''Československá republika)'', Fourth Czecho ...

), the only Eastern Bloc state that the Soviets had permitted to retain democratic structures. The public brutality of the coup shocked Western powers more than any event up to that point and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to the Marshall Plan in the United States Congress.

In an immediate aftermath of the crisis, the

London Six-Power Conference

The London Six-Power Conference in 1948 was held between the three Western occupation forces in Germany after the World War II (United States, Britain and France) and the Benelux countries. The aim of the conference was to pave the way for Germ ...

was held, resulting in the

Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

boycott of the Allied Control Council and its incapacitation, an event marking the beginning of the full-blown Cold War, as well as ending any hopes at the time for a single German government and leading to formation in 1949 of the

Federal Republic of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen constituent states have a total population of over 84 ...

and

German Democratic Republic

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

.

The twin policies of the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan led to billions in economic and military aid for Western Europe, Greece, and Turkey. With the US assistance, the Greek military

won its civil war. Under the leadership of

Alcide De Gasperi

Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi (; 3 April 1881 – 19 August 1954) was an Italian politician and statesman who founded the Christian Democracy party and served as prime minister of Italy in eight successive coalition governments from 1945 t ...

the Italian

Christian Democrats defeated the powerful

Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

–

Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

alliance in the

elections of 1948.

Outside of Europe, the United States also began to express interest in the development of many other countries, so that they would not fall under the sway of Eastern Bloc communism. In his January 1949 inaugural address, Truman declared for the first time in U.S. history that

international development

International development or global development is a broad concept denoting the idea that societies and countries have differing levels of economic development, economic or human development (economics), human development on an international sca ...

would be a key part of U.S. foreign policy. The resulting program later became known as the

Point Four Program

The Point Four Program was a technical assistance program for "developing countries" announced by United States President Harry S. Truman in his inaugural address on January 20, 1949. It took its name from the fact that it was the fourth foreig ...

because it was the fourth point raised in his address.

Espionage

All major powers engaged in espionage, using a great variety of spies,

double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

s,

moles, and new technologies such as the tapping of telephone cables. The Soviet

KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

("Committee for State Security"), the bureau responsible for foreign espionage and internal surveillance, was famous for its effectiveness. The most famous Soviet operation involved its

atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Cold W ...

that delivered crucial information from the United States'

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, leading the USSR to detonate its first nuclear weapon in 1949, four years after the American detonation and much sooner than expected. A massive network of informants throughout the Soviet Union was used to monitor dissent from official Soviet politics and morals. Although to an extent

disinformation

Disinformation is misleading content deliberately spread to deceive people, or to secure economic or political gain and which may cause public harm. Disinformation is an orchestrated adversarial activity in which actors employ strategic dece ...

had always existed, the term itself was invented, and the strategy formalized by a

black propaganda

Black propaganda is a form of propaganda intended to create the impression that it was created by those it is supposed to discredit. Black propaganda contrasts with gray propaganda, which does not identify its source, as well as white propagan ...

department of the Soviet KGB.

Based on the amount of top-secret Cold War archival information that has been released, historian

Raymond L. Garthoff

Raymond Leonard "Ray" Garthoff (born March 26, 1929) is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a specialist on arms control, intelligence, the Cold War, NATO, and the former Soviet Union. He is a former United States Ambassadors to Bulga ...

concludes there probably was parity in the quantity and quality of secret information obtained by each side. However, the Soviets probably had an advantage in terms of

HUMINT

Human intelligence (HUMINT, pronounced ) is intelligence-gathering by means of human sources and interpersonal communication. It is distinct from more technical intelligence-gathering disciplines, such as signals intelligence (SIGINT), imager ...

(human intelligence or interpersonal espionage) and "sometimes in its reach into high policy circles." In terms of decisive impact, however, he concludes:

We also can now have high confidence in the judgment that there were no successful "moles" at the political decision-making level on either side. Similarly, there is no evidence, on either side, of any major political or military decision that was prematurely discovered through espionage and thwarted by the other side. There also is no evidence of any major political or military decision that was crucially influenced (much less generated) by an agent of the other side.

According to historian Robert L. Benson, "Washington's forte was

'signals' intelligencethe procurement and analysis of coded foreign messages," leading to the

Venona project or Venona intercepts, which monitored the communications of Soviet intelligence agents.

Moynihan wrote that the Venona project contained "overwhelming proof of the activities of Soviet spy networks in America, complete with names, dates, places, and deeds." The Venona project was kept highly secret even from policymakers until the

Moynihan Commission in 1995. Despite this, the decryption project had already been betrayed and dispatched to the USSR by

Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963, he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring that had divulged British secr ...

and

Bill Weisband

William Weisband, Sr. (August 28, 1908 – May 14, 1967) was a Ukrainian-American Codebreaking, cryptanalyst and NKVD agent (code name 'LINK'), best known for his role in revealing U.S. decryptions of Soviet Union, Soviet diplomatic and intelli ...

in 1946, as was discovered by the US by 1950. Nonetheless, the Soviets had to keep their discovery of the program secret, too, and continued leaking their own information, some of which was still useful to the American program. According to Moynihan, even President Truman may not have been fully informed of Venona, which may have left him unaware of the extent of Soviet espionage.

Clandestine

atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Cold W ...

from the Soviet Union, who infiltrated the

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

during WWII, played a major role in increasing tensions that led to the Cold War.

In addition to usual espionage, the Western agencies paid special attention to debriefing

Eastern Bloc defectors.

Edward Jay Epstein describes that the CIA understood that the KGB used "provocations", or fake defections, as a trick to embarrass Western intelligence and establish Soviet double agents. As a result, from 1959 to 1973, the CIA required that East Bloc defectors went through a counterintelligence investigation before being recruited as a source of intelligence.

During the late 1970s and 1980s, the KGB perfected its use of espionage to sway and distort diplomacy.

Active measures

Active measures () is a term used to describe political warfare conducted by the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. The term, which dates back to the 1920s, includes operations such as espionage, propaganda, sabotage and assassination, b ...

were "clandestine operations designed to further Soviet foreign policy goals," consisting of disinformation, forgeries, leaks to foreign media, and the channeling of aid to militant groups. Retired KGB Major General

Oleg Kalugin

Oleg Danilovich Kalugin (; born 6 September 1934) is a former KGB general (stripped of his rank and awards by a Russian Court decision in 2002). He was during a time, head of KGB political operations in the United States and later a critic of ...

described active measures as "the heart and soul of

Soviet intelligence."

During the

Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual worsening of relations between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the Cold War. This was primarily caused by divergences that arose from their ...

, "spy wars" also occurred between the USSR and PRC.

Cominform and the Tito–Stalin Split

In September 1947, the Soviets created

Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist–Leninist communist parties in Europe which existed from 1947 to 1956. Formed in the wake of the dissolution ...

to impose orthodoxy within the international communist movement and tighten political control over Soviet

satellites

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scientif ...

through coordination of communist parties in the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

. Cominform faced an embarrassing setback the following June, when the

Tito–Stalin split

The Tito–Stalin split or the Soviet–Yugoslav split was the culmination of a conflict between the political leaderships of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, under Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin, respectively, in the years following World W ...

obliged its members to expel

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, which remained communist but adopted a

non-aligned position and began accepting financial aid from the US.

Besides Berlin, the status of the city of

Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

was at issue. Until the break between Tito and Stalin, the Western powers and the Eastern bloc faced each other uncompromisingly. In addition to capitalism and communism, Italians and Slovenes, monarchists and republicans as well as war winners and losers often faced each other irreconcilably. The neutral buffer state

Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste was an independent territory in Southern Europe between Italy and SFR Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia, facing the north part of the Adriatic Sea, under United Nations Security Council Resolution 16, direct responsibility of ...

, founded in 1947 with the United Nations, was split up and dissolved in 1954 and 1975, also because of the détente between the West and Tito.

Berlin Blockade

The US and Britain merged their western German occupation zones into "

Bizone" (1 January 1947, later "Trizone" with the addition of France's zone, April 1949). As part of the economic rebuilding of Germany, in early 1948, representatives of a number of Western European governments and the United States announced an agreement for a merger of western German areas into a federal governmental system. In addition, in accordance with the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

, they began to re-industrialize and rebuild the West German economy, including the introduction of a new

Deutsche Mark

The Deutsche Mark (; "German mark (currency), mark"), abbreviated "DM" or "D-Mark" (), was the official currency of West Germany from 1948 until 1990 and later of unified Germany from 1990 until the adoption of the euro in 2002. In English, it ...

currency to replace the old

Reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛ︁ℳ︁; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, and in the American, British and French occupied zones of Germany, until 20 June 1948. The Reichsmark was then replace ...

currency that the Soviets had debased. The US had secretly decided that a unified and neutral Germany was undesirable, with

Walter Bedell Smith

General (United States), General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forc ...

telling General Eisenhower "in spite of our announced position, we really do not want nor intend to accept German unification on any terms that the Russians might agree to, even though they seem to meet most of our requirements."

Shortly thereafter, Stalin instituted the Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May 1949), one of the first major crises of the Cold War, preventing Western supplies from reaching West Germany's exclave of

West Berlin

West Berlin ( or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin from 1948 until 1990, during the Cold War. Although West Berlin lacked any sovereignty and was under military occupation until German reunification in 1 ...

. The United States (primarily), Britain, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and several other countries began the massive "Berlin airlift", supplying West Berlin with provisions despite Soviet threats.

The Soviets mounted a public relations campaign against the policy change. Once again, the East Berlin communists attempted to disrupt the

Berlin municipal elections, which were held on 5 December 1948 and produced a turnout of 86% and an overwhelming victory for the non-communist parties. The results effectively divided the city into East and West, the latter comprising US, British and French sectors. 300,000 Berliners demonstrated and urged the international airlift to continue, and US Air Force pilot

Gail Halvorsen

Colonel Gail Seymour Halvorsen (October 10, 1920 – February 16, 2022) was a senior officer and command pilot in the United States Air Force. He rose to fame for dropping candy to German children during the Berlin Airlift from 1948 to 1949, ...

created "

Operation Vittles

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, roa ...

", which supplied candy to German children. The Airlift was as much a logistical as a political and psychological success for the West; it firmly linked West Berlin to the United States. In May 1949, Stalin lifted the blockade.

In 1952, Stalin repeatedly

proposed a plan to unify East and West Germany under a single government chosen in elections supervised by the United Nations, if the new Germany were to stay out of Western military alliances, but this proposal was turned down by the Western powers. Some sources dispute the sincerity of the proposal.

Beginnings of NATO and Radio Free Europe

Britain, France, the United States, Canada and eight other western European countries signed the

North Atlantic Treaty

The North Atlantic Treaty, also known as the Washington Treaty, forms the legal basis of, and is implemented by, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The treaty was signed in Washington, D.C., on 4 April 1949.

Background

The treat ...

of April 1949, establishing the

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental transnational military alliance of 32 member states—30 European and 2 North American. Established in the aftermat ...

(NATO). That August, the

first Soviet atomic device was detonated in

Semipalatinsk,

Kazakh SSR. Following Soviet refusals to participate in a German rebuilding effort set forth by western European countries in 1948, the US, Britain and France spearheaded the establishment of the

Federal Republic of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen constituent states have a total population of over 84 ...

from the

three Western zones of occupation in April 1949. The Soviet Union proclaimed

its zone of occupation in Germany the

German Democratic Republic

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

that October.

Media in the

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

was an

organ of the state, completely reliant on and subservient to the communist party. Radio and television organizations were state-owned, while print media was usually owned by political organizations, mostly by the local communist party. Soviet radio broadcasts used Marxist rhetoric to attack capitalism, emphasizing themes of labor exploitation, imperialism and war-mongering.

Along with the broadcasts of the

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

and the

Voice of America

Voice of America (VOA or VoA) is an international broadcasting network funded by the federal government of the United States that by law has editorial independence from the government. It is the largest and oldest of the American internation ...

to Central and Eastern Europe, a major propaganda effort began in 1949 was

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) is a media organization broadcasting news and analyses in 27 languages to 23 countries across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. Headquartered in Prague since 1995, RFE/RL ...