Code de l'indigĂŠnat on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Native code () was a diverse and fluctuating set of arbitrary laws and regulations which created in practice an inferior legal status for natives of French colonies from 1881 until 1944â1947.

The Native code was introduced by decree, in various forms and degrees of severity, to

, '' Human Rights League'' (LDH), March 6, 2005 - URL accessed on January 17, 2007 The 1865 decree was then modified by the 1870 CrĂŠmieux decrees, which granted full French nationality to Algerian Jews, followed in 1889 by ("foreigners"). The opposition was keen to give the same right to Muslims, but the French settlers did not want to equip the natives with rights equal to their own, primarily for demographic reasons. Moreover, it was at Algeria's request for an 1889 Act restoring the , French citizenship being awarded to anyone born in France, not being applied to Muslims. In 1881, the ''Code de l'IndigĂŠnat'' formalised ''de facto''

In Africa, were assigned to two separate court systems. After their creation by Governor-General Ernest Roume and Secretary General Martial Merlin in 1904, most legal matters were processed officially by the so-called ''customary courts''. They were courts convened by village or some other French-recognized native authority or were Muslim

In Africa, were assigned to two separate court systems. After their creation by Governor-General Ernest Roume and Secretary General Martial Merlin in 1904, most legal matters were processed officially by the so-called ''customary courts''. They were courts convened by village or some other French-recognized native authority or were Muslim

Le corps dâexception : questions Ă Sidi Mohammed Barkat

, mouvement-egalite.org, 14 June 2006 The loi Lamine Guèye of 7 April 1946 formally extended citizenship across the empire, indigènes included. Third, the law of 20 September 1947 eliminated the two-tier court system and mandated equal access to public employment. Applied in fact only very slowly, the abrogation of the ''code de l'indigÊnat'' did not become real during 1962, when most of the colonies had become independent and French law adopted the notion of double

''Le Corps d'exception: les artifices du pouvoir colonial et la destruction de la vie''

(Paris, Editions Amsterdam, 2005) propose, afin de rendre compte des massacres coloniaux de mai 1945 et d'octobre 1961, une analyse des dimensions juridiques, symboliques et politiques de l'indigĂŠnat. * Benton, Lauren: Colonial Law and Cultural Difference: "Jurisdictional Politics and the Formation of the Colonial State" in ''Comparative Studies in Society and History'', Vol. 41, No. 3 (Jul., 1999) * Crowder, Michael: ''West Africa Under Colonial Rule''. Northwestern Univ. Press. (1968) . . . * Julien, C. A.: "From the French Empire to the French Union". ''International Affairs'', Vol. 26, No. 4 (Oct. 1950), pp. 487â502. . . * Le Cour Grandmaison, Olivier

''De l'indigÊnat - Anatomie d'un monstre juridique : Le droit colonial en AlgÊrie et dans l'Empire français''

Zones, 2010 * Manière, Laurent

''Le code de l'indigÊnat en Afrique occidentale française et son application au Dahomey (1887-1946)''

Thèse de doctorat d'Histoire, UniversitĂŠ Paris 7-Denis diderot, 2007, 574 p. * Mortimer, Edward, ''France and the Africans, 1944â1960: A Political History'' (1970) * Thomas, Martin: ''The French Empire Between the Wars: Imperialism, Politics and Society''. Manchester University Press, (2005). . * Weil, Patrick, ''Qu'est-ce qu'un Français? : histoire de la nationalitĂŠ française depuis la RĂŠvolution'', Paris, Grasset, 2002 . . . {{DEFAULTSORT:Indigenat Legal history of France French colonial empire French West Africa French Equatorial Africa French Indochina Race and law Debt bondage

Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to AlgeriaâTunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to AlgeriaâLibya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

and Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; ; ; ; ) is a historical exonym and endonym, exonym for part of Vietnam, depending on the contexts, usually for Southern Vietnam. Sometimes it referred to the whole of Vietnam, but it was commonly used to refer t ...

in 1881, New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

and Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to MauritaniaâSenegal border, the north, Mali to MaliâSenegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

in 1887, AnnamâTonkin

Tonkin, also spelled Tongkin, Tonquin or Tongking, is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain '' ÄĂ ng NgoĂ i'' under Tráťnh lords' control, including both the ...

and Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

in 1897, Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

in 1898, Mayotte

Mayotte ( ; , ; , ; , ), officially the Department of Mayotte (), is an Overseas France, overseas Overseas departments and regions of France, department and region and single territorial collectivity of France. It is one of the Overseas departm ...

and Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

in 1901, French West Africa

French West Africa (, ) was a federation of eight French colonial empires#Second French colonial empire, French colonial territories in West Africa: Colonial Mauritania, Mauritania, French Senegal, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guin ...

in 1904, French Equatorial Africa in 1910, French Somaliland

French Somaliland (; ; ) was a French colony in the Horn of Africa. It existed between 1884 and 1967, at which became the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas. The Republic of Djibouti is its legal successor state.

History

French Somalil ...

in 1912, and the Mandates of Togo

Togo, officially the Togolese Republic, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to GhanaâTogo border, the west, Benin to BeninâTogo border, the east and Burkina Faso to Burkina FasoâTogo border, the north. It is one of the le ...

and Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon, is a country in Central Africa. It shares boundaries with Nigeria to the west and north, Chad to the northeast, the Central African Republic to the east, and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the R ...

in 1923 and 1924.

Under the term are often grouped other oppressive measures that were applied to the native population of the French empire, such as forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

, requisitions, capitation (head tax), etc.

Introduction in Algeria

The Native code () was created first to solve specific problems of administering Algeria during the early-to-mid-19th century. In 1685, the French royal ''Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by King Louis XIV, Louis XIV of France in 1685 defining the conditions of Slavery in France, slavery in the French colonial empire and served as the code for slavery conduct in the French colonies ...

'' decreed the treatment of subject peoples, but it was in Algeria during the 1830s and 1840s that the French government began actively to rule large subject populations. It quickly realised that it was impractical in areas without a French population, and French experiences with large groups of subject people had also convinced many that both direct rule and eventual assimilation were undesirable.

In 1830, Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to AlgeriaâTunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to AlgeriaâLibya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

became the first modern French colony. The treaty in which the Bey

Bey, also spelled as Baig, Bayg, Beigh, Beig, Bek, Baeg, Begh, or Beg, is a Turkic title for a chieftain, and a royal, aristocratic title traditionally applied to people with special lineages to the leaders or rulers of variously sized areas in ...

of Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

capitulated to France stipulated that France undertook not to infringe the freedom of people or their religion. The term was already in use in 1830 to describe locals who, whether Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

or Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

, were not considered French prior to the royal decree of 24 February 1834. However, they still did not have full citizenship.

A royal ordinance of 1845 created three types of administration in Algeria. In areas that Europeans comprised a substantial part of the population, the elected mayors and councils for self-governing "full exercise" communes (). In the "mixed" communes, where Muslims were a large majority, government was exercised by officials, most of whom were appointed but some elected. The governments included representatives of the (great chieftains) and a French administrator. The indigenous communes (), remote areas that were not adequately pacified, remained under the , direct rule by the military.

The first native code was implemented by the Algerian of 14 July 1865, under Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis NapolĂŠon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

, which changed the situation by allowing Algerian Jews and Muslims full citizenship on request. Its first article stipulated:

"Indigenous Muslims are French; however, they continue to be governed by Muslim law. They may be admitted to serve in the army or navy. They may be called to civil functions and jobs in Algeria. Upon request, they may be permitted to enjoy the rights of a French citizen; in this case, they are governed by the political and civil laws of France."That was intended to promote assimilation, but as few people were willing to abandon their religious values, it had the opposite effect. By 1870, fewer than 200 requests had been registered by Muslims and 152 by Jewish Algerians.le code de lâindigĂŠnat dans lâAlgĂŠrie coloniale

, '' Human Rights League'' (LDH), March 6, 2005 - URL accessed on January 17, 2007 The 1865 decree was then modified by the 1870 CrĂŠmieux decrees, which granted full French nationality to Algerian Jews, followed in 1889 by ("foreigners"). The opposition was keen to give the same right to Muslims, but the French settlers did not want to equip the natives with rights equal to their own, primarily for demographic reasons. Moreover, it was at Algeria's request for an 1889 Act restoring the , French citizenship being awarded to anyone born in France, not being applied to Muslims. In 1881, the ''Code de l'IndigĂŠnat'' formalised ''de facto''

discrimination

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, class, religion, or sex ...

by creating specific penalties for and by organising the seizure or appropriation of their lands.

The Franco-Algerian philosopher Sidi Mohammed Barkat described the legal limbo: "Not really inclusion nor in fact exclusion, but the indefinite hanging on for some future inclusion". He argued that the legal limbo allowed the French to treat the colonised as a less-than-human ''mass'', but still subject to a humanising mission. They would become fully human only when they had cast off all the features that the French would use to define them as part of the mass of the .

In practical terms, by continuing the fiction that the "indigenous is French", the ''Code de l'IndigĂŠnat'' enabled French authorities to subject a large alien population to their rule by legal separation and a practice of indirect institutions to supplement a tiny French governing force.

Expanding empire: 1887â1904

While the grew from circumstances of the colonial rule of North Africa, it was in sub-Saharan Africa and Indochina that the code became formalised. As French rule expanded during the "Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

", the government found itself nominal ruler of some 50 million people with only a tiny retinue of French officials. The Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884â1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

specified that territory seized must be ruled actively, or other powers were welcome to seize it. The was the method by which France ruled all its territories in Africa, Guiana

The Guianas, also spelled Guyanas or Guayanas, are a geographical region in north-eastern South America. Strictly, the term refers to the three Guianas: Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, formerly British, Dutch, and French Guiana respectiv ...

, New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

and Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

without having to extend the rights of Frenchmen to the people who lived there.

The protectorates (Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

and Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to AlgeriaâMorocc ...

for example) were not affected by the regime.Camille Bonora-Waisman, ''France and the Algerian Conflict: Issues in Democracy and Political Stability, 1988â1995'', Ashgate Publishing, 2003, p. 3.

In practice: Africa 1887â1946

Punishment

The was free to impose summary punishment under any of 34 (later 12) headings of infractions specified by the code, ranging from murder to 'disrespect' of France, its symbols, or functionaries. Punishment could range from fines, to 15 days in prison or immediate execution. The statute stated that all punishments must be signed by the colonial governor, but that was almost always done after the fact. Corporal punishment was outlawed, but still used regularly. Although these powers were periodically reformed, in practice they became arbitrary and frequently used. More than 1,500 infractions reported officially were punished by the in Moyen Congo in 1908â1909 alone.Taxes and forced labour

Along with the punishments were a set of methods for extracting value from colonial subjects. In Africa, they included the ''corvĂŠe

CorvĂŠe () is a form of unpaid forced labour that is intermittent in nature, lasting for limited periods of time, typically only a certain number of days' work each year. Statute labour is a corvĂŠe imposed by a state (polity), state for the ...

'' (forced labour for specific projects), ''Prestation'' (taxes paid in forced labor), ''Head Tax'' (often arbitrary monetary taxes, food and property requisitioning, market taxes), and the ''Blood Tax'' (forced conscription to the native Tirailleur

A tirailleur (), in the Napoleonic era, was a type of light infantry trained to skirmish ahead of the main columns. Later, the term "''tirailleur''" was used by the French Army as a designation for indigenous infantry recruited in the French c ...

units). Many major projects in French West Africa

French West Africa (, ) was a federation of eight French colonial empires#Second French colonial empire, French colonial territories in West Africa: Colonial Mauritania, Mauritania, French Senegal, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guin ...

in this period were performed by forced labour, including work on roads and mines and in fields of private companies.

Demands for taxes and forced labour varied according to the local , and in some areas, forced contract labour continued as a staple of the colonial economy, such as if private enterprises could not attract sufficient workers or for projects of colonial officials. In the interwar period, the demand for forced labour increased massively. Even the most well-intentioned officials often believed in 'forced modernization' (supposing that 'progress' would result only from coercion), and French-created 'chiefs' also enjoyed tremendous coercive power. That resulted in enrichment for chiefs and the French, and harsh conditions for African labourers.

Plantations, forestry operations and salt mines in Senegal continued to be operated by forced labour, mandated by the local commandant and provided by official chiefs until the 1940s. Forced agricultural production was common in Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

from the 19th century until the Second World War, mandated sometimes by the central French government (rubber until 1920, rice during the Second World War), sometimes for profit (the cotton plantations of Compagnie Française d'Afrique Occidentale and Unilever

Unilever PLC () is a British multinational consumer packaged goods company headquartered in London, England. It was founded on 2 September 1929 following the merger of Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie with British soap maker Lever B ...

), and sometimes on the personal whim of the local commandant, such as one official's attempt to introduce cotton into the Guinean highlands. Unlike the Congo Free State

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large Sovereign state, state and absolute monarchy in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium, King Leopold II, the const ...

, infamous for its 19th-century forced rubber cultivation by private fiat, the French government administration was bound legally to provide labour for its rubber concessionaires in French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa (, or AEF) was a federation of French colonial territories in Equatorial Africa which consisted of Gabon, French Congo, Ubangi-Shari, and Chad. It existed from 1910 to 1958 and its administration was based in Brazzav ...

and settler-owned cotton plantations in CĂ´te d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as CĂ´te d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of CĂ´te d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest city and ...

.

Native governance

In addition, native sub-officials, such as the appointed local chiefs, made use of forced labour, compulsory crops and taxes in kind at their discretion. As the enforcers of the , they were also partly beneficiaries. Still, they themselves were very much subject to French authority when the French chose to exercise it. It was only in 1924 that were exempted from the , and if they showed insubordination or disloyalty, they could still, like all Africans, be imprisoned for as many as ten years for 'political offences' by French officials, subject to a signature of the Minister of Colonies.Courts

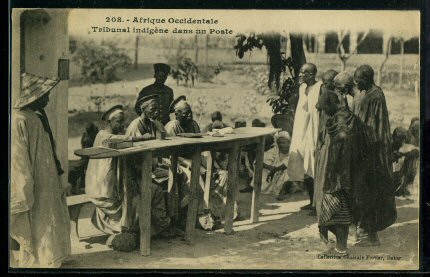

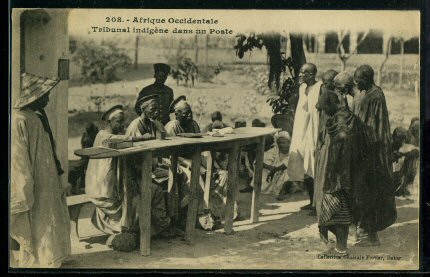

In Africa, were assigned to two separate court systems. After their creation by Governor-General Ernest Roume and Secretary General Martial Merlin in 1904, most legal matters were processed officially by the so-called ''customary courts''. They were courts convened by village or some other French-recognized native authority or were Muslim

In Africa, were assigned to two separate court systems. After their creation by Governor-General Ernest Roume and Secretary General Martial Merlin in 1904, most legal matters were processed officially by the so-called ''customary courts''. They were courts convened by village or some other French-recognized native authority or were Muslim Sharia

Sharia, SharÄŤ'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharÄŤĘżah'' ...

courts. While Muslim courts had some real local relevance behind them, the French history of chief-creation was to replace traditional chiefs with Africans who would be dependent upon the French. Consequently, customary courts often served simply to increase the power of official chiefs. What was deemed customary differed from to , with the Commandant relying upon his native subofficials to interpret and formalize oral traditions of which the French had little knowledge. Civil cases that came to the attention of the French officials were tried by an administrator-judge in a for which the administrator-judge was an appointed African notable (other than local chief).

Matters deemed especially serious by the French officials or matters for which the colonial power had any interest were handled by a French administrator-judge. All criminal cases were handled by a directed by the (the lowest post held by caucasians) with the assistance of two local notables and two caucasian officials or (in practice) anyone whom the administrator-judge chose. They could be appealed to the , where the administrator-judge was the local and was not bound to heed the advice of even his own appointed assistants. Beyond that, there was no functioning appeals process though in theory, the colonies' governor had to sign off on all decisions that imposed punishments greater than those allowed for summary sentences. Historians examining the court records have found that governors were asked for approval after the fact and in all but a minuscule number of cases signed off on whatever their commandants decided.

Those Africans who had obtained the status of French citizens (''ĂvoluĂŠ

In the Belgian colonial empire, Belgian and French colonial empires, an (, 'evolved one' or 'developed one') was an African who had been Europeanised through education and cultural assimilation, assimilation and had accepted European values and ...

'') or those born into the Four Communes of Senegal () were subject to a small French court system, operating under the Code Napoleon

The Napoleonic Code (), officially the Civil Code of the French (; simply referred to as ), is the French civil code established during the French Consulate in 1804 and still in force in France, although heavily and frequently amended since it ...

as practiced in France. The lack of an adversarial system

The adversarial system (also adversary system, accusatorial system, or accusatory system) is a legal system used in the common law countries where two advocates represent their parties' case or position before an impartial person or group of peopl ...

(in French law, the judge is also the prosecutor) may have worked in France but was hardly trusted by educated Africans. That may explain why French Africans' demand for access (promoted by politician Lamine Guèye Lamine Gueye may refer to:

* Amadou Lamine-Guèye (1891â1968), Senegalese politician

* Lamine Guèye (skier) (born 1960), Senegalese skier

* Lamine Gueye (footballer) (born 1998), Senegalese footballer

* Stade Lamine Guèye, multi-use stadium ...

) to both local and French courts was so strong and why so few who managed to meet the requirements of citizenship chose to pursue it but abandoned themselves to French justice.

Even were not free from summary law. During 1908, most African voters in Saint-Louis were eliminated from the rolls, and in the ''Decree of 1912'', the government said that only who complied with the rigorous demands of those seeking French citizenship from the outside would be able to exercise French rights. Even then, were subject to customary and arbitrary law if they stepped outside the Four Communes. It was only through a protracted battle by Senegalese Deputy Blaise Diagne and his help recruiting thousands of Africans to fight in World War I that legal and voting rights were restored to even the with the Loi Blaise Diagne of 29 September 1916.

Becoming French

Resistance

Resistance, while common, was usually indirect. Huge population shifts occurred in France's African colonies, especially when large conscription or forced labour drives were implemented by particularly-zealous officials and when many African slaves were emancipated by the French authorities following French conquest. Whole villages fled during the roadbuilding campaign during the 1920s and the 1930s, and colonial officials gradually relaxed the use of forced labour. Rober Delavignette, a former colonial official, documented the mass movement of some 100,000 Mossi people from Upper Volta to Gold Coast to escape forced labor, while the investigative journalistAlbert Londres

Albert Londres (1 November 1884 â 16 May 1932) was a French journalist and writer. One of the inventors of investigative journalism, Londres not only reported news but created it, and reported it from a personal perspective. He criticized abu ...

claims that the figures were closer to 600,000 fleeing to Gold Coast and 2 million fleeing to Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

.

IndigĂŠnat regime in Algeria

In practice, the IndigĂŠnat regime put in place from 1830 clearly appeared to be a favour done to the vanquished Algerians. They were not bound to respect French laws or French jurisdiction. They followed Qur'anic justice served according to Qur'anic custom until the abolishment of the IndigĂŠnat regime in 1945. To be admitted to full French citizenship, when that is possible, the Muslim had to renounce Qur'anic law and promise to follow the law of the Republic. There were important differences such as on polygamy, arranged marriage, divorce, and inequality between man and woman in matters. In 1874, a list of infractions punishable by French justice is made on the IndigĂŠnat on matters such as an unauthorised meeting or disrespectful act. In 1860s, the IndigĂŠnat regime was being debated. NapolĂŠon III dreamed of an Arab Kingdom in Algeria, which was very unpopular for French settlers. After the Empire fell, the Republic tried to simplify naturalisation procedures and even a mass naturalisation, but that provoked massive outrage from settlers. The local authorities also dragged their feet to complicate the task of Muslums wanting to naturalise. That caused between 1865 and 1915 only 2396 Muslims in Algeria to naturalise. The indigenous got a limited vote and participated notably in Muslim electoral colleges for municipal councils and had a minority of seats. However, the Muslim population was often the majority. Muslims were a fifth of the council until 1919, when they became a third. After theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 â 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Law of 4 February 1919 reformed the procedure for full naturalisation. That reform disappointed the Muslims, and only 1204 of them in Algeria naturalised from 1919 to 1930. Lyautey, followed the negotiations with the settlers, noted, "I consider the situation incurable. The French farming settlers have a full Gerry mentality, with the same theories on inferior races worth exploiting without mercy. They have no humanity or intelligence." (Weil Patrick, ''Qu'est-ce qu'un Français'', Paris, Grasset, 2002, p. 241)

Dissolution

Some elements of the were reformed over time. The formal right of caucasian civilians to exercise summary punishment was eliminated by the decree of 15 November 1924. This decree reduced the headings by which subjects could be summarily punished to 24, which was later further reduced to 12. Maximum fines decreased from 25 francs to 15, and summary imprisonment was capped at five days. In practice, though, summary punishment continued at the discretion of local authorities. In French-controlled Cameroon, during 1935 there were 32,858 prison sentences for these 'administrative' offenses, compared to 3,512 for common law offenses. Head taxes had been increasing well above inflation from the First World War right through to the economic crisis of the 1930s and reached their high point during the Second World War, but it was decolonisation which saw a real drop in taxes paid without representation. Gradually, the ''corvĂŠe

CorvĂŠe () is a form of unpaid forced labour that is intermittent in nature, lasting for limited periods of time, typically only a certain number of days' work each year. Statute labour is a corvĂŠe imposed by a state (polity), state for the ...

'' system was reformed because of international criticism and popular resistance. In French West Africa

French West Africa (, ) was a federation of eight French colonial empires#Second French colonial empire, French colonial territories in West Africa: Colonial Mauritania, Mauritania, French Senegal, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guin ...

, the had been formalised by the local decree of 25 November 1912. Duration and conditions varied, but as of 1926, all able-bodied men were required to work for no longer than eight days at a stint in Senegal, ten in Guinea and twelve in Soudan and Mauritania. Workers were supposed to be provided with food if they were working more than 5 km from home, but that was often ignored. In 1930, the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, The original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are international humanitarian laws consisting of four treaties and three additional protocols that establish international legal standards for humanitarian t ...

outlawed the , but France substituted a work tax () by the French West Africa decree of 12 September 1930 in which able-bodied men were assessed a high monetary tax, which they could pay via forced labor.

Political moves

It was, in fact, political processes that doomed the system. The Popular Front government in the decrees of 11 March and 20 March 1937 created the first labor regulations on work contracts and the creation of trade unions, but they remained largely unenforced until the late 1940s. The journalism ofAndrĂŠ Gide

AndrĂŠ Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 â 19 February 1951) was a French writer and author whose writings spanned a wide variety of styles and topics. He was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Gide's career ranged from his begi ...

and Albert Londres

Albert Londres (1 November 1884 â 16 May 1932) was a French journalist and writer. One of the inventors of investigative journalism, Londres not only reported news but created it, and reported it from a personal perspective. He criticized abu ...

, the political pressure of the French left and groups like the League for Human Rights and Popular Aid put pressure on the colonial system, but it was the promises made at the Brazzaville Conference

The Brazzaville Conference () was a meeting of prominent Free French leaders held in January 1944 in Brazzaville, the capital of French Equatorial Africa, during World War II.

After the Fall of France to Nazi Germany, the collaborationist ...

of 1944, the crucial role of the colonies for the Free French

Free France () was a resistance government

claiming to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third French Republic, Third Republic during World War II. Led by General , Free France was established as a gover ...

during the Second World War and the looming Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam, and alternatively internationally as the French-Indochina War) was fought between France and Viáťt Minh ( Democratic Rep ...

and the Malagasy Uprising

The Malagasy Uprising (; ) was a Malagasy nationalist rebellion against French colonial rule in Madagascar, lasting from March 1947 to February 1949. Starting in late 1945, Madagascar's first French National Assembly deputies, Joseph Raseta, ...

that all made the new Fourth Republic reorient France to decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

. The declaration at Brazzaville, more revolutionary for its discussion of the issue rather than any formal process, declared the "progressive suppression" of the code de l'indigĂŠnat but only after the end of the war.

The small political representation from the colonies after the war made ending the indigĂŠnat as a primary goal even though the men were drawn from the ĂvoluĂŠ

In the Belgian colonial empire, Belgian and French colonial empires, an (, 'evolved one' or 'developed one') was an African who had been Europeanised through education and cultural assimilation, assimilation and had accepted European values and ...

class of full French citizens. The passage of the loi Lamine Guèye rwas the culmination of this process, and repealed the courts and labour laws of the IndigÊnat.

Legally, the IndigÊnat was dismantled in three phases. The ordinance of 7 May 1944 suppressed the summary punishment statutes, and offered citizenship to those who met certain criteria and would surrender their rights to native or Muslim courts. The citizenship was labeled : their (even-future) children would still be subject to the IndigÊnat., mouvement-egalite.org, 14 June 2006 The loi Lamine Guèye of 7 April 1946 formally extended citizenship across the empire, indigènes included. Third, the law of 20 September 1947 eliminated the two-tier court system and mandated equal access to public employment. Applied in fact only very slowly, the abrogation of the ''code de l'indigÊnat'' did not become real during 1962, when most of the colonies had become independent and French law adopted the notion of double

jus soli

''Jus soli'' ( or , ), meaning 'right of soil', is the right of anyone born in the territory of a state to nationality or citizenship. ''Jus soli'' was part of the English common law, in contrast to ''jus sanguinis'' ('right of blood') ass ...

. Thus, any children of colonial parents born in French-ruled territory became French citizens. All others were by then full citizens of their respective nations.

Full voting representation and full French legal, labour, and property rights were never offered to the entire sujet class. The Loi Cadre of 1956 extended more rights, including consultative 'legislatures' for the colonies within the French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was ''de jure'' the end of the "indigenous" () status of Frenc ...

. Within three years, this was replaced by the referendum on the French Community

The French Community () was the constitutional organization set up in October 1958 between France and its remaining African colonies, then in the process of decolonization. It replaced the French Union, which had reorganized the colonial em ...

in which colonies could vote for independence The First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam, and alternatively internationally as the French-Indochina War) was fought between French Fourth Republic, France and Viáť ...

resulted in independence for the different regions of French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China), officially known as the Indochinese Union and after 1941 as the Indochinese Federation, was a group of French dependent territories in Southeast Asia from 1887 to 1954. It was initial ...

. The Algerian War

The Algerian War (also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence) ''; '' (and sometimes in Algeria as the ''War of 1 November'') was an armed conflict between France and the Algerian National Liberation Front (Algeri ...

and the French Fifth Republic

The Fifth Republic () is France's current republic, republican system of government. It was established on 4 October 1958 by Charles de Gaulle under the Constitution of France, Constitution of the Fifth Republic..

The Fifth Republic emerged fr ...

of 1958 resulted in independence for most of the rest of empire in 1959 to 1962. The Comoros

The Comoros, officially the Union of the Comoros, is an archipelagic country made up of three islands in Southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city is Moroni, ...

Islands (except Mayotte

Mayotte ( ; , ; , ; , ), officially the Department of Mayotte (), is an Overseas France, overseas Overseas departments and regions of France, department and region and single territorial collectivity of France. It is one of the Overseas departm ...

) and Djibouti

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area ...

gained independence during the 1970s. Those parts of the empire that remained (Mayotte, New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

and French Guiana

French Guiana, or Guyane in French, is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France located on the northern coast of South America in the Guianas and the West Indies. Bordered by Suriname to the west ...

) became legally parts of France and only then was the category of French subject ended.

See also

*ArmÊe indigène

The Indigenous Army (; ), also known as the Army of Saint-Domingue () was the name bestowed to the coalition of anti-slavery men and women who fought in the Haitian Revolution in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Encompassing both black slaves, and ...

* Assimilation (French colonial)

Assimilation was a major ideological component of French colonialism during the 19th and 20th centuries. The French government promoted the concept of cultural assimilation to colonial subjects in the French colonial empire, claiming that by adop ...

* Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by King Louis XIV, Louis XIV of France in 1685 defining the conditions of Slavery in France, slavery in the French colonial empire and served as the code for slavery conduct in the French colonies ...

(1689)

* DĂŠcret CrĂŠmieux

* ĂvoluĂŠ

In the Belgian colonial empire, Belgian and French colonial empires, an (, 'evolved one' or 'developed one') was an African who had been Europeanised through education and cultural assimilation, assimilation and had accepted European values and ...

s

* French citizenship and identity

* French Colonial Empire

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas Colony, colonies, protectorates, and League of Nations mandate, mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "Firs ...

* French nationality law

French nationality law is historically based on the principles of ''jus soli'' (Latin for "right of soil") and ''jus sanguinis'', (Latin for "right of blood") according to Ernest Renan's definition, in opposition to the German definition of na ...

* French rule in Algeria

French Algeria ( until 1839, then afterwards; unofficially ; ), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of Algerian history when the country was a colony and later an integral part of France. French rule lasted until the end of the Alg ...

* French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was ''de jure'' the end of the "indigenous" () status of Frenc ...

* Indirect rule

Indirect rule was a system of public administration, governance used by imperial powers to control parts of their empires. This was particularly used by colonial empires like the British Empire to control their possessions in Colonisation of Afri ...

* Indygenat

''Indygenat'' or ' naturalization' in the PolishâLithuanian Commonwealth was the grant of nobility to foreign nobles. To grant ''indygenat'', a foreign noble had to submit proof of their service to the Republic, together with proof of nobility i ...

, recognition of foreign noble

A noble is a member of the nobility.

Noble may also refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Noble Glacier, King George Island

* Noble Nunatak, Marie Byrd Land

* Noble Peak, Wiencke Island

* Noble Rocks, Graham Land

Australia

* Noble Island, Gr ...

status in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

* Loi Cadre (1956 Overseas Reform Act)

References

;Notes ;CitationsFurther reading

* Barkat, Sidi Mohamed''Le Corps d'exception: les artifices du pouvoir colonial et la destruction de la vie''

(Paris, Editions Amsterdam, 2005) propose, afin de rendre compte des massacres coloniaux de mai 1945 et d'octobre 1961, une analyse des dimensions juridiques, symboliques et politiques de l'indigĂŠnat. * Benton, Lauren: Colonial Law and Cultural Difference: "Jurisdictional Politics and the Formation of the Colonial State" in ''Comparative Studies in Society and History'', Vol. 41, No. 3 (Jul., 1999) * Crowder, Michael: ''West Africa Under Colonial Rule''. Northwestern Univ. Press. (1968) . . . * Julien, C. A.: "From the French Empire to the French Union". ''International Affairs'', Vol. 26, No. 4 (Oct. 1950), pp. 487â502. . . * Le Cour Grandmaison, Olivier

''De l'indigÊnat - Anatomie d'un monstre juridique : Le droit colonial en AlgÊrie et dans l'Empire français''

Zones, 2010 * Manière, Laurent

''Le code de l'indigÊnat en Afrique occidentale française et son application au Dahomey (1887-1946)''

Thèse de doctorat d'Histoire, UniversitĂŠ Paris 7-Denis diderot, 2007, 574 p. * Mortimer, Edward, ''France and the Africans, 1944â1960: A Political History'' (1970) * Thomas, Martin: ''The French Empire Between the Wars: Imperialism, Politics and Society''. Manchester University Press, (2005). . * Weil, Patrick, ''Qu'est-ce qu'un Français? : histoire de la nationalitĂŠ française depuis la RĂŠvolution'', Paris, Grasset, 2002 . . . {{DEFAULTSORT:Indigenat Legal history of France French colonial empire French West Africa French Equatorial Africa French Indochina Race and law Debt bondage