Classical Liberal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the

''Fifty Years of American Idealism: 1865–1915''

short history of ''

branch

A branch, also called a ramus in botany, is a stem that grows off from another stem, or when structures like veins in leaves are divided into smaller veins.

History and etymology

In Old English, there are numerous words for branch, includ ...

of liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

that advocates free market

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

and laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

economics and civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

under the rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government

In political philosophy, limited government is the concept of a government limited in power. It is a key concept in the history of liberalism.Amy Gutmann, "How Limited Is Liberal Government" in Liberalism Without Illusions: Essays on Liberal ...

, economic freedom, political freedom

Political freedom (also known as political autonomy or political agency) is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies.Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?", ''Between Past and ...

and freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

. Classical liberalism, contrary to progressive branches like social liberalism

Social liberalism is a political philosophy and variety of liberalism that endorses social justice, social services, a mixed economy, and the expansion of civil and political rights, as opposed to classical liberalism which favors limited g ...

, looks more negatively on social policies

Some professionals and universities consider social policy a subset of public policy, while other practitioners characterize social policy and public policy to be two separate, competing approaches for the same public interest (similar to Compar ...

, tax

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to regulate and reduce negative externalities. Tax co ...

ation and the state involvement in the lives of individuals, and it advocates deregulation

Deregulation is the process of removing or reducing state regulations, typically in the economic sphere. It is the repeal of governmental regulation of the economy. It became common in advanced industrial economies in the 1970s and 1980s, as a ...

.

Until the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

and the rise of social liberalism, classical liberalism was called economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism ...

. Later, the term was applied as a retronym

A retronym is a newer name for something that differentiates it from something else that is newer, similar, or seen in everyday life; thus, avoiding confusion between the two.

Etymology

The term ''retronym'', a neologism composed of the combi ...

, to distinguish earlier 19th-century liberalism from social liberalism. By modern standards, in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, the bare term ''liberalism'' often means social or progressive liberalism, but in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, the bare term ''liberalism'' often means classical liberalism.

Classical liberalism gained full flowering in the early 18th century, building on ideas dating at least as far back as the 16th century, within the Iberian, French, British, and Central European contexts, and it was foundational to the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and "American Project" more broadly. Notable liberal individuals whose ideas contributed to classical liberalism include John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

,Steven M. Dworetz (1994). ''The Unvarnished Doctrine: Locke, Liberalism, and the American Revolution''. François Quesnay, Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste () is a male French name, originating with Saint John the Baptist, and sometimes shortened to Baptiste. The name may refer to any of the following:

Persons

* Charles XIV John of Sweden, born Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, was K ...

, Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

, Marquis de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French Philosophy, philosopher, Political economy, political economist, Politics, politician, and m ...

, Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

, Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, and David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist, politician, and member of Parliament. He is recognized as one of the most influential classical economists, alongside figures such as Thomas Malthus, Ada ...

. It drew on classical economics

Classical economics, also known as the classical school of economics, or classical political economy, is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. It includ ...

, especially the economic ideas espoused by Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

in Book One of ''The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', usually referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is a book by the Scottish people, Scottish economist and moral philosophy, moral philosopher Adam Smith; ...

'', and on a belief in natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

. In contemporary times, Murray Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School,Ronald Hamowy, ed., 2008, The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism', Cato Institute, Sage, , p. 62: "a leading economist of the Austri ...

, Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek (8 May 1899 – 23 March 1992) was an Austrian-born British academic and philosopher. He is known for his contributions to political economy, political philosophy and intellectual history. Hayek shared the 1974 Nobe ...

, Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and ...

, Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (; ; September 29, 1881 – October 10, 1973) was an Austrian-American political economist and philosopher of the Austrian school. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the social contributions of classical l ...

, Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell ( ; born June 30, 1930) is an American economist, economic historian, and social and political commentator. He is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. With widely published commentary and books—and as a guest on T ...

, Walter E. Williams, George Stigler

George Joseph Stigler (; January 17, 1911 – December 1, 1991) was an American economist. He was the 1982 laureate in Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and is considered a key leader of the Chicago school of economics.

Early life and e ...

, Larry Arnhart, Ronald Coase

Ronald Harry Coase (; 29 December 1910 – 2 September 2013) was a British economist and author. Coase was educated at the London School of Economics, where he was a member of the faculty until 1951. He was the Clifton R. Musser Professor of Eco ...

and James M. Buchanan are seen as the most prominent advocates of classical liberalism. However, other scholars have made reference to these contemporary thoughts as '' neoclassical liberalism'', distinguishing them from 18th-century classical liberalism.Mayne, Alan James (1999). ''From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigmss''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 124–125. .

In its defense of economic liberties, classical liberalism may be described as conservative or right wing

Right-wing politics is the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position b ...

, while in its defense of civil liberties, it has more in common with modern liberalism ( the left). Despite this, classical liberals tend to reject the right's higher tolerance for economic protectionism and the left's inclination for collective group rights

Individual rights, also known as natural rights, are rights held by individuals by virtue of being human. Some theists believe individual rights are bestowed by God. An individual right is a moral claim to freedom of action.

Group rights, also k ...

due to classical liberalism's central principle of individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

. Additionally, in the United States, classical liberalism is considered closely tied to, or synonymous with, American libertarianism.

Evolution of core beliefs

Core beliefs of classical liberals included new ideaswhich departed from both the olderconservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

idea of society as a family and from the later sociological

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociology was coined in ...

concept of society as a complex set of social network

A social network is a social structure consisting of a set of social actors (such as individuals or organizations), networks of Dyad (sociology), dyadic ties, and other Social relation, social interactions between actors. The social network per ...

s.

Classical liberals agreed with Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

that individuals created government to protect themselves from each other and to minimize conflict between individuals that would otherwise arise in a state of nature

In ethics, political philosophy, social contract theory, religion, and international law, the term state of nature describes the hypothetical way of life that existed before humans organised themselves into societies or civilisations. Philosoph ...

. These beliefs were complemented by a belief that financial incentive could best motivate labourers. This belief led to the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (4 & 5 Will. 4. c. 76) (PLAA) known widely as the New Poor Law, was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed by the British Whig Party, Whig government of Charles ...

, which limited the provision of social assistance, based on the idea that markets are the mechanism that most efficiently leads to wealth.

Drawing on ideas of Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, classical liberals believed that it was in the common interest that all individuals be able to secure their own economic self-interest. They were critical of what would come to be the idea of the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

as interfering in a free market

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

.Alan Ryan, "Liberalism", in ''A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy'', ed. Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1995), p. 293. Despite Smith's resolute recognition of the importance and value of labour and of labourers, classical liberals criticized labour's group rights

Individual rights, also known as natural rights, are rights held by individuals by virtue of being human. Some theists believe individual rights are bestowed by God. An individual right is a moral claim to freedom of action.

Group rights, also k ...

being pursued at the expense of individual rights

Individual rights, also known as natural rights, are rights held by individuals by virtue of being human. Some theists believe individual rights are bestowed by God. An individual right is a moral claim to freedom of action.

Group rights, also k ...

while accepting corporations' rights, which led to inequality of bargaining power

Inequality of bargaining power in law, economics and social sciences refers to a situation where one party to a bargain, contract or agreement, has more and better alternatives than the other party. This results in one party having greater power ...

. Classical liberals argued that individuals should be free to obtain work from the highest-paying employers, while the profit motive

In economics, the profit motive is the motivation of firms that operate so as to maximize their profits. Mainstream microeconomic theory posits that the ultimate goal of a business is "to make money" - not in the sense of increasing the firm ...

would ensure that products that people desired were produced at prices they would pay. In a free market, both labour and capital would receive the greatest possible reward, while production would be organized efficiently to meet consumer demand. Classical liberals argued for what they called a minimal state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

and government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

, limited to the following functions:

* Laws to protect citizens from wrongs committed against them by other citizens, which included protection of individual rights, private property, enforcement of contracts and common law.

* A common national defence to provide protection against foreign invaders.

* Public works and services that cannot be provided in a free market such as a stable currency, standard weights and measures and building and upkeep of roads, canals, harbours, railways, communications and postal services.

Classical liberals asserted that rights are of a negative nature and therefore stipulate that other individuals and governments are to refrain from interfering with the free market, opposing social liberals who assert that individuals have positive rights, such as the right to vote, the right to an education, the right to healthcare, and the right to a minimum wage. For society to guarantee positive rights, it requires taxation over and above the minimum needed to enforce negative rights. Kelly, D. (1998): ''A Life of One's Own: Individual Rights and the Welfare State'', Washington, DC: Cato Institute

The Cato Institute is an American libertarian think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C. It was founded in 1977 by Ed Crane, Murray Rothbard, and Charles Koch, chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Koch Industries.Koch ...

.

Core beliefs of classical liberals did not necessarily include democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

nor government by a majority vote by citizens because "there is nothing in the bare idea of majority rule to show that majorities will always respect the rights of property or maintain rule of law".Ryan, A. (1995): "Liberalism", In: Goodin, R. E. and Pettit, P., eds.: ''A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy'', Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, p. 293. For example, James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

argued for a constitutional republic with protections for individual liberty over a pure democracy, reasoning that in a pure democracy a "common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole ... and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party".

In the late 19th century, classical liberalism developed into neoclassical liberalism, which argued for government to be as small as possible to allow the exercise of individual freedom

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and ad ...

. In its most extreme form, neoclassical liberalism advocated social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

. Right-libertarianism

Right-libertarianism,Rothbard, Murray (1 March 1971)"The Left and Right Within Libertarianism". ''WIN: Peace and Freedom Through Nonviolent Action''. 7 (4): 6–10. Retrieved 14 January 2020.Goodway, David (2006). '' Anarchist Seeds Beneath the ...

is a modern form of neoclassical liberalism. However, Edwin Van de Haar states although classical liberal thought influenced libertarianism, there are significant differences between them. Classical liberalism refuses to give priority to liberty over order and therefore does not exhibit the hostility to the state which is the defining feature of libertarianism. As such, right-libertarians believe classical liberals do not have enough respect for individual property rights and lack sufficient trust in the free market

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

's workings and spontaneous order

Spontaneous order, also named self-organization in the hard sciences, is the spontaneous emergence of order out of seeming chaos. The term "self-organization" is more often used for physical changes and biological processes, while "spontaneous ...

leading to their support of a much larger state. Right-libertarians also disagree with classical liberals as being too supportive of central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, national bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the monetary policy of a country or monetary union. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central bank possesses a monopoly on increasing the mo ...

s and monetarist

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of policy-makers in controlling the amount of money in circulation. It gained prominence in the 1970s, but was mostly abandoned as a direct guidance to monetary ...

policies.

Typology of beliefs

Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek (8 May 1899 – 23 March 1992) was an Austrian-born British academic and philosopher. He is known for his contributions to political economy, political philosophy and intellectual history. Hayek shared the 1974 Nobe ...

identified two different traditions within classical liberalism, namely the British tradition and the French tradition:

* The British philosophers Bernard Mandeville

Bernard Mandeville, or Bernard de Mandeville (; 15 November 1670 – 21 January 1733), was an Anglo-Dutch philosopher, political economist, satirist, writer and physician. Born in Rotterdam, he lived most of his life in England and used English ...

, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

, Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

, Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, Adam Ferguson

Adam Ferguson, (Scottish Gaelic: ''Adhamh MacFhearghais''), also known as Ferguson of Raith (1 July N.S. /20 June O.S. 1723 – 22 February 1816), was a Scottish philosopher and historian of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Ferguson was sympath ...

, Josiah Tucker and William Paley

William Paley (July 174325 May 1805) was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian apologetics, Christian apologist, philosopher, and Utilitarianism, utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument ...

held beliefs in empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

, the common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

and in traditions and institutions which had spontaneously evolved but were imperfectly understood.

*The French philosophers Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

, Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

, Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre ferv ...

, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just

Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just (; 25 August 176710 Thermidor, Year II 8 July 1794, sometimes nicknamed the Archangel of Terror, was a French revolutionary, political philosopher, member and president of the National Convention, French ...

, Marquis de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French Philosophy, philosopher, Political economy, political economist, Politics, politician, and m ...

, the Encyclopedists and the Physiocrats

Physiocracy (; from the Greek for "government of nature") is an economic theory developed by a group of 18th-century Age of Enlightenment French economists. They believed that the wealth of nations derived solely from the value of "land agricult ...

believed in rationalism and sometimes showed hostility to tradition and religion.

Hayek conceded that the national labels did not exactly correspond to those belonging to each tradition since he saw the Frenchmen Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

, Benjamin Constant

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (25 October 1767 – 8 December 1830), or simply Benjamin Constant, was a Swiss and French political thinker, activist and writer on political theory and religion.

A committed republican from 1795, Constant ...

, Joseph De Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, diplomat, and magistrate. One of the forefathers of conservatism, Maistre advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immedi ...

and Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (29 July 180516 April 1859), was a French Aristocracy (class), aristocrat, diplomat, political philosopher, and historian. He is best known for his works ''Democracy in America'' (appearing in t ...

as belonging to the British tradition and the British Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

, Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

, Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer and pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the F ...

, Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English essayist, historian, and politician. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for ...

, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

as belonging to the French tradition. Hayek also rejected the label ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' as originating from the French tradition and alien to the beliefs of Hume and Smith.

Guido De Ruggiero also identified differences between "Montesquieu and Rousseau, the English and the democratic types of liberalism" and argued that there was a "profound contrast between the two Liberal systems". He claimed that the spirit of "authentic English Liberalism" had "built up its work piece by piece without ever destroying what had once been built, but basing upon it every new departure". This liberalism had "insensibly adapted ancient institutions to modern needs" and "instinctively recoiled from all abstract proclamations of principles and rights". Ruggiero claimed that this liberalism was challenged by what he called the "new Liberalism of France" that was characterised by egalitarianism and a "rationalistic consciousness".

In 1848, Francis Lieber

Francis Lieber (18 March 1798 – 2 October 1872) was a German-American jurist and political philosopher. He is best known for the Lieber Code, the first codification of the customary law and the laws of war for battlefield conduct, which serve ...

distinguished between what he called "Anglican and Gallican Liberty". Lieber asserted that "independence in the highest degree, compatible with safety and broad national guarantees of liberty, is the great aim of Anglican liberty, and self-reliance is the chief source from which it draws its strength". On the other hand, Gallican liberty "is sought in government ... . e French look for the highest degree of political civilisation in organisation, that is, in the highest degree of interference by public power".

History

Great Britain

Frenchphysiocracy

Physiocracy (; from the Greek for "government of nature") is an economic theory developed by a group of 18th-century Age of Enlightenment French economists. They believed that the wealth of nations derived solely from the value of "land agricult ...

heavily influenced British classical liberalism, which traces its roots to the Whigs and Radicals

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

. Whiggery had become a dominant ideology following the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

of 1688 and was associated with supporting the British Parliament, upholding the rule of law, defending landed property

In real estate, a landed property or landed estate is a property that generates income for the owner (typically a member of the gentry) without the owner having to do the actual work of the estate.

In medieval Western Europe, there were two compe ...

and sometimes included freedom of the press and freedom of speech. The origins of rights were seen as being in an ancient constitution

The ancient constitution of England was a 17th-century political theory about the common law, and the antiquity of the House of Commons, used at the time in particular to oppose the royal prerogative. It was developed initially by Sir Edward Coke, ...

existing from time immemorial

Time immemorial () is a phrase meaning time extending beyond the reach of memory, record, or tradition, indefinitely ancient, "ancient beyond memory or record". The phrase is used in legally significant contexts as well as in common parlance.

...

. Custom rather than as natural rights

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', ''fundamental rights ...

justified these rights. Whigs believed that executive power had to be constrained. While they supported limited suffrage, they saw voting as a privilege rather than as a right. However, there was no consistency in Whig ideology and diverse writers including John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

, Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

and Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

were all influential among Whigs, although none of them were universally accepted.

From the 1790s to the 1820s, British radicals concentrated on parliamentary and electoral reform, emphasising natural rights and popular sovereignty. Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer and pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the F ...

and Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

adapted the language of Locke to the ideology of radicalism. The radicals saw parliamentary reform as a first step toward dealing with their many grievances, including the treatment of Protestant Dissenters, the slave trade, high prices, and high taxes. There was greater unity among classical liberals than there had been among Whigs. Classical liberals were committed to individualism, liberty, and equal rights, as well as some other important tenants of leftism, since classical liberalism was introduced in the late 18th century as a leftist movement. They believed these goals required a free economy with minimal government interference. Some elements of Whiggery were uncomfortable with the commercial nature of classical liberalism. These elements became associated with conservatism.

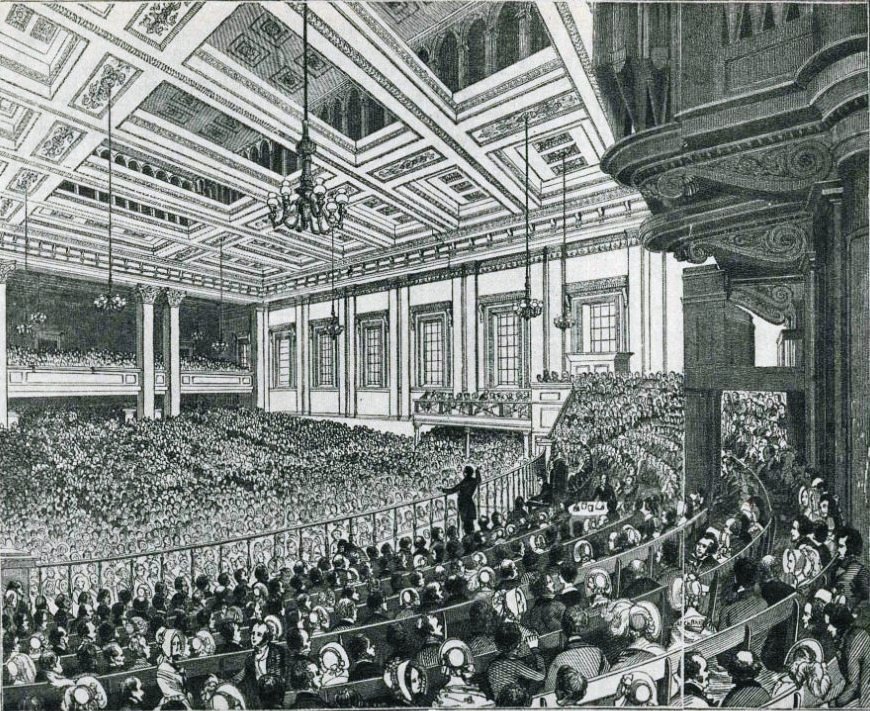

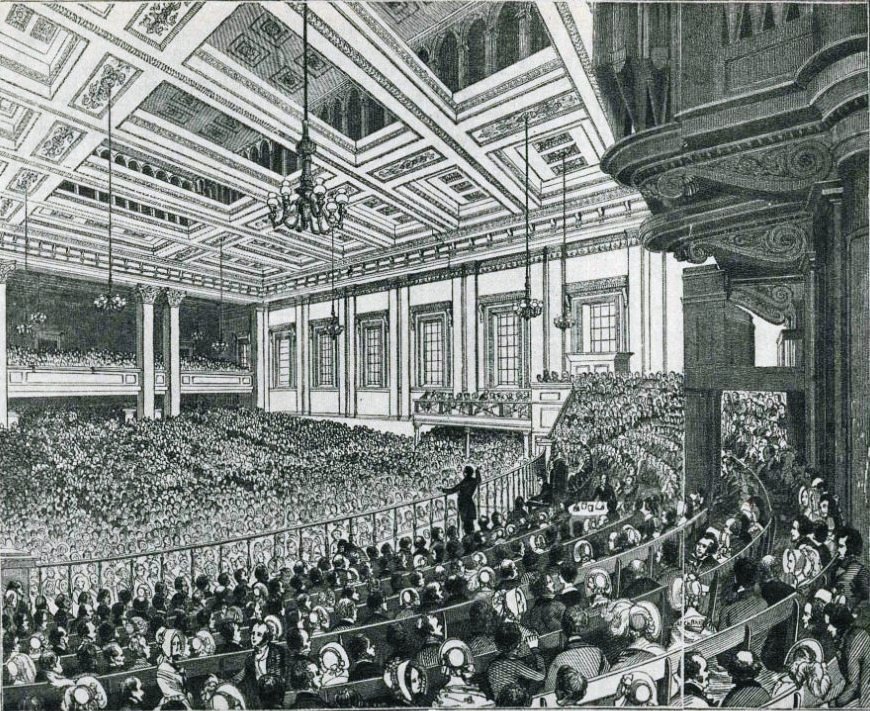

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 ( 10 Geo. 4. c. 7), also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that removed the sacramental tests that barred Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom f ...

, the Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the Reform Act 1832, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. 4. c. 45), enacted by the Whig government of Pri ...

and the repeal of the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

in 1846. The Anti-Corn Law League brought together a coalition of liberal and radical groups in support of free trade under the leadership of Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden (3 June 1804 – 2 April 1865) was an English Radicals (UK), Radical and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician, manufacturing, manufacturer, and a campaigner for free trade and peace. He was associated with the Anti–Corn Law L ...

and John Bright

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade policies.

A Quaker, Bright is most famous for battling the Corn La ...

, who opposed aristocratic privilege, militarism, and public expenditure and believed that the backbone of Great Britain was the yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of Serfdom, servants in an Peerage of England, English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in Kingdom of England, mid-1 ...

farmer. Their policies of low public expenditure and low taxation were adopted by William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he was Prime Minister ...

when he became Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

and later Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

. Classical liberalism was often associated with religious dissent and nonconformism

Nonconformity or nonconformism may refer to:

Culture and society

* Insubordination, the act of willfully disobeying an order of one's superior

*Dissent, a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or entity

** ...

.

Although classical liberals aspired to a minimum of state activity, they accepted the principle of government intervention

A market intervention is a policy or measure that modifies or interferes with a market, typically done in the form of state action, but also by philanthropic and political-action groups. Market interventions can be done for a number of reas ...

in the economy from the early 19th century on, with passage of the Factory Acts

The Factory Acts were a series of acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom beginning in 1802 to regulate and improve the conditions of industrial employment.

The early acts concentrated on regulating the hours of work and moral wel ...

. From around 1840 to 1860, ''laissez-faire'' advocates of the Manchester School and writers in ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British newspaper published weekly in printed magazine format and daily on Electronic publishing, digital platforms. It publishes stories on topics that include economics, business, geopolitics, technology and culture. M ...

'' were confident that their early victories would lead to a period of expanding economic and personal liberty and world peace, but would face reversals as government intervention and activity continued to expand from the 1850s. Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

and James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote '' The History of Britis ...

, although advocates of ''laissez-faire'', non-intervention in foreign affairs, and individual liberty, believed that social institutions could be rationally redesigned through the principles of utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

. The Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

rejected classical liberalism altogether and advocated Tory democracy. By the 1870s, Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

and other classical liberals concluded that historical development was turning against them. By the First World War, the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

had largely abandoned classical liberal principles.

The changing economic and social conditions of the 19th century led to a division between neo-classical and social (or welfare) liberals, who while agreeing on the importance of individual liberty differed on the role of the state. Neo-classical liberals, who called themselves "true liberals", saw Locke's '' Second Treatise'' as the best guide and emphasised "limited government" while social liberals supported government regulation and the welfare state. Herbert Spencer in Britain and William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and neoclassical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University, where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology and bec ...

were the leading neo-classical liberal theorists of the 19th century. The evolution from classical to social/welfare liberalism is for example reflected in Britain in the evolution of the thought of John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

.

Helena Vieira, writing for the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), established in 1895, is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. The school specialises in the social sciences. Founded ...

, argued that classical liberalism "may contradict some fundamental democratic principles as they are inconsistent with the ''principle of unanimity'' (also known as the '' Pareto Principle'') – the idea that if everyone in society prefers a policy A to a policy B, then the former should be adopted."

Ottoman Empire

TheOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

had liberal free trade policies by the 18th century, with origins in capitulations of the Ottoman Empire

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire were contracts between the Ottoman Empire and several other Christian powers, particularly France. Turkish capitulations, or Ahidnâmes were generally bilateral acts whereby definite arrangements were enter ...

, dating back to the first commercial treaties signed with France in 1536 and taken further with capitulations in 1673, in 1740 which lowered duties

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; , past participle of ; , whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may arise from a system of ethics or morality, e ...

to only 3% for imports and exports and in 1790. Ottoman free trade policies were praised by British economists advocating free trade such as J. R. McCulloch in his ''Dictionary of Commerce'' (1834) but criticized by British politicians opposing free trade such as Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, who cited the Ottoman Empire as "an instance of the injury done by unrestrained competition" in the 1846 Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

debate, arguing that it destroyed what had been "some of the finest manufactures of the world" in 1812.

United States

In the United States, liberalism took a strong root because it had little opposition to its ideals, whereas in Europe liberalism was opposed by many reactionary or feudal interests such as the nobility; the aristocracy, including army officers; the landed gentry; and the established church.Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

adopted many of the ideals of liberalism, but in the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

changed Locke's "life, liberty and property" to the more socially liberal

Social liberalism is a political philosophy and variety of liberalism that endorses social justice, social services, a mixed economy, and the expansion of civil and political rights, as opposed to classical liberalism which favors limited g ...

"Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness

"Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness" is a well-known phrase from the United States Declaration of Independence. Scanned image of the Jefferson's "original Rough draught" of the Declaration of Independence, written in June 1776, includin ...

". As the United States grew, industry became a larger and larger part of American life; and during the term of its first populist

Populism is a contested concept used to refer to a variety of political stances that emphasize the idea of the " common people" and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite. It is frequently associated with anti-establis ...

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

, Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, economic questions came to the forefront. The economic ideas of the Jacksonian era were almost universally the ideas of classical liberalism. Freedom, according to classical liberals, was maximised when the government took a "hands off" attitude toward the economy. Historian Kathleen G. Donohue argues:

the center of classical liberal theory n Europewas the idea of ''laissez-faire''. To the vast majority of American classical liberals, however, ''laissez-faire'' did not mean no government intervention at all. On the contrary, they were more than willing to see government provide tariffs, railroad subsidies, and internal improvements, all of which benefited producers. What they condemned was intervention on behalf of consumers.''

The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'' magazine espoused liberalism every week starting in 1865 under the influential editor Edwin Lawrence Godkin

Edwin Lawrence Godkin (2 October 183121 May 1902) was an American journalist and newspaper editor. He founded ''The Nation'' and was the editor-in-chief of the ''New York Evening Post'' from 1883 to 1899.Eric Fettman, "Godkin, E.L." in Stephen ...

(1831–1902). The ideas of classical liberalism remained essentially unchallenged until a series of depressions, thought to be impossible according to the tenets of classical economics

Classical economics, also known as the classical school of economics, or classical political economy, is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. It includ ...

, led to economic hardship from which the voters demanded relief. In the words of William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

, " You shall not crucify this nation on a cross of gold". Classical liberalism remained the orthodox belief among American businessmen until the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.Eric Voegelin, Mary Algozin, and Keith Algozin, "Liberalism and Its History", ''Review of Politics'' 36, no. 4 (1974): 504–520. . The Great Depression in the United States

In the United States, the Great Depression began with the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 and then spread worldwide. The nadir came in 1931–1933, and recovery came in 1940. The stock market crash marked the beginning of a decade of high u ...

saw a sea change in liberalism, with priority shifting from the producers to consumers. Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

represented the dominance of modern liberalism in politics for decades. In the words of Arthur Schlesinger Jr.:

Alan Wolfe

Alan Wolfe (born 1942) is an American political science, political scientist and a sociologist on the faculty of Boston College who serves as director of the Boisi Center for Religion and American Public Life. He is also a member of the Advisor ...

summarizes the viewpoint that there is a continuous liberal understanding that includes both Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

and John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

:

The view that modern liberalism is a continuation of classical liberalism is controversial and disputed by many. James Kurth, Robert E. Lerner, John Micklethwait, Adrian Wooldridge

Adrian Wooldridge (born 1959) is an author and columnist. He is the Global Business Columnist at Bloomberg Opinion.

Life and career

Wooldridge was educated at Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied modern history and was awarded a fellowsh ...

and several other political scholars have argued that classical liberalism still exists today, but in the form of American conservatism

Conservatism in the United States is one of two major political ideologies in the United States, with the other being liberalism. Traditional American conservatism is characterized by a belief in individualism, traditionalism, capitalism, ...

. According to Deepak Lal

Deepak Kumar Lal (1940 – 30 April 2020) was an Indian-born British liberal economist, author, professor and consultant.http://www.econ.ucla.edu/Lal/cv2004.pdf Best known for his 1983 book, The Poverty of “Development Economics", Lal was ...

, only in the United States does classical liberalism continue to be a significant political force through American conservatism. American libertarians

In the United States, libertarianism is a political philosophy promoting individual liberty. According to common meanings of Conservatism in the United States, conservatism and Modern liberalism in the United States, liberalism in the United S ...

also claim to be the true continuation of the classical liberal tradition.

Tadd Wilson, writing for the libertarian Foundation for Economic Education

The Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) is an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative, Libertarianism in the United States, libertarian economics, economic think tank. Founded in 1946 in New York City, FEE is now headquartere ...

, noted that "Many on the left and right criticize classical liberals for focusing purely on economics and politics to the neglect of a vital issue: culture."

Intellectual sources

John Locke

Central to classical liberal ideology was their interpretation ofJohn Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

's '' Second Treatise of Government'' and '' A Letter Concerning Toleration'', which had been written as a defence of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Although these writings were considered too radical at the time for Britain's new rulers, Whigs, radicals and supporters of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

later came to cite them. However, much of later liberal thought was absent in Locke's writings or scarcely mentioned and his writings have been subject to various interpretations. For example, there is little mention of constitutionalism

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional to ...

, the separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

and limited government

In political philosophy, limited government is the concept of a government limited in power. It is a key concept in the history of liberalism.Amy Gutmann, "How Limited Is Liberal Government" in Liberalism Without Illusions: Essays on Liberal ...

.

James L. Richardson identified five central themes in Locke's writing:

* Individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

* Consent

* Rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

and government as trustee

* Significance of property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, re ...

* Religious toleration

Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, ...

Although Locke did not develop a theory of natural rights, he envisioned individuals in the state of nature as being free and equal. The individual, rather than the community or institutions, was the point of reference. Locke believed that individuals had given consent to government and therefore authority derived from the people rather than from above. This belief would influence later revolutionary movements.

As a trustee, government was expected to serve the interests of the people, not the rulers; and rulers were expected to follow the laws enacted by legislatures. Locke also held that the main purpose of men uniting into commonwealths and governments was for the preservation of their property. Despite the ambiguity of Locke's definition of property, which limited property to "as much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of", this principle held great appeal to individuals possessed of great wealth.

Locke held that the individual had the right to follow his own religious beliefs and that the state should not impose a religion against Dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

s, but there were limitations. No tolerance should be shown for atheists

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

, who were seen as amoral, or to Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

, who were seen as owing allegiance to the Pope over their own national government.

Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

's ''The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', usually referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is a book by the Scottish people, Scottish economist and moral philosophy, moral philosopher Adam Smith; ...

'', published in 1776, was to provide most of the ideas of economics, at least until the publication of John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

's ''Principles of Political Economy

''Principles of Political Economy'' (1848) by John Stuart Mill was one of the most important economics or political economy textbooks of the mid-nineteenth century. It was revised until its seventh edition in 1871, shortly before Mill's death ...

'' in 1848. Smith addressed the motivation for economic activity, the causes of prices and the distribution of wealth and the policies the state should follow to maximise wealth.

Smith wrote that as long as supply, demand, prices and competition were left free of government regulation, the pursuit of material self-interest, rather than altruism, would maximise the wealth of a society through profit-driven production of goods and services. An "invisible hand

The invisible hand is a metaphor inspired by the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith that describes the incentives which free markets sometimes create for self-interested people to accidentally act in the public interest, even ...

" directed individuals and firms to work toward the public good as an unintended consequence of efforts to maximise their own gain. This provided a moral justification for the accumulation of wealth, which had previously been viewed by some as sinful.

He assumed that workers could be paid wages as low as was necessary for their survival, which was later transformed by David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist, politician, and member of Parliament. He is recognized as one of the most influential classical economists, alongside figures such as Thomas Malthus, Ada ...

and Thomas Robert Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

into the "iron law of wages

The iron law of wages is a proposed law of economics that asserts that real wages always tend, in the long run, toward the minimum wage necessary to sustain the life of the worker. The theory was first named by Ferdinand Lassalle in the mid-n ...

". His main emphasis was on the benefit of free internal and international trade, which he thought could increase wealth through specialisation in production. He also opposed restrictive trade preferences, state grants of monopolies and employers' organisations and trade unions. Government should be limited to defence, public works and the administration of justice, financed by taxes based on income.

Smith's economics was carried into practice in the nineteenth century with the lowering of tariffs in the 1820s, the repeal of the Poor Relief Act

Poor Relief Act (with its variations) is a stock short title used in the United Kingdom for legislation relating to poor relief.

List

*The Poor Relief Act 1601

*The Poor Relief Act 1662

*The Poor Relief Act 1691

The Poor Relief (Ireland) Acts 183 ...

that had restricted the mobility of labour in 1834 and the end of the rule of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

over India in 1858.

Classical economics

In addition to Smith's legacy,Say's law

In classical economics, Say's law, or the law of markets, is the claim that the production of a product creates demand for another product by providing something of value which can be exchanged for that other product. So, production is the source ...

, Thomas Robert Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

' theories of population and David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist, politician, and member of Parliament. He is recognized as one of the most influential classical economists, alongside figures such as Thomas Malthus, Ada ...

's iron law of wages

The iron law of wages is a proposed law of economics that asserts that real wages always tend, in the long run, toward the minimum wage necessary to sustain the life of the worker. The theory was first named by Ferdinand Lassalle in the mid-n ...

became central doctrines of classical economics

Classical economics, also known as the classical school of economics, or classical political economy, is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. It includ ...

. The pessimistic nature of these theories provided a basis for criticism of capitalism by its opponents and helped perpetuate the tradition of calling economics the " dismal science".

Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste () is a male French name, originating with Saint John the Baptist, and sometimes shortened to Baptiste. The name may refer to any of the following:

Persons

* Charles XIV John of Sweden, born Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, was K ...

was a French economist who introduced Smith's economic theories into France and whose commentaries on Smith were read in both France and Britain. Say challenged Smith's labour theory of value

The labor theory of value (LTV) is a theory of value that argues that the exchange value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of " socially necessary labor" required to produce it. The contrasting system is typically known as ...

, believing that prices were determined by utility and also emphasised the critical role of the entrepreneur in the economy. However, neither of those observations became accepted by British economists at the time. His most important contribution to economic thinking was Say's law, which was interpreted by classical economists that there could be no overproduction

In economics, overproduction, oversupply, excess of supply, or glut refers to excess of supply over demand of products being offered to the market. This leads to lower prices and/or unsold goods along with the possibility of unemployment.

T ...

in a market and that there would always be a balance between supply and demand. This general belief influenced government policies until the 1930s. Following this law, since the economic cycle was seen as self-correcting, government did not intervene during periods of economic hardship because it was seen as futile.

Malthus wrote two books, ''An Essay on the Principle of Population

The book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'' was first published anonymously in 1798, but the author was soon identified as Thomas Robert Malthus. The book warned of future difficulties, on an interpretation of the population increasing ...

'' (published in 1798) and ''Principles of Political Economy

''Principles of Political Economy'' (1848) by John Stuart Mill was one of the most important economics or political economy textbooks of the mid-nineteenth century. It was revised until its seventh edition in 1871, shortly before Mill's death ...

'' (published in 1820). The second book which was a rebuttal of Say's law had little influence on contemporary economists. However, his first book became a major influence on classical liberalism. In that book, Malthus claimed that population growth would outstrip food production because population grew geometrically while food production grew arithmetically. As people were provided with food, they would reproduce until their growth outstripped the food supply. Nature would then provide a check to growth in the forms of vice and misery. No gains in income could prevent this and any welfare for the poor would be self-defeating. The poor were in fact responsible for their own problems which could have been avoided through self-restraint.

Ricardo, who was an admirer of Smith, covered many of the same topics, but while Smith drew conclusions from broadly empirical observations he used deduction, drawing conclusions by reasoning from basic assumptions. While Ricardo accepted Smith's labour theory of value

The labor theory of value (LTV) is a theory of value that argues that the exchange value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of " socially necessary labor" required to produce it. The contrasting system is typically known as ...

, he acknowledged that utility could influence the price of some rare items. Rents on agricultural land were seen as the production that was surplus to the subsistence required by the tenants. Wages were seen as the amount required for workers' subsistence and to maintain current population levels. According to his iron law of wages, wages could never rise beyond subsistence levels. Ricardo explained profits as a return on capital, which itself was the product of labour, but a conclusion many drew from his theory was that profit was a surplus appropriated by capitalists

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by a n ...

to which they were not entitled.

Utilitarianism

The central concept ofutilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

, which was developed by Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

, was that public policy should seek to provide "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". While this could be interpreted as a justification for state action to reduce poverty, it was used by classical liberals to justify inaction with the argument that the net benefit to all individuals would be higher.

Utilitarianism provided British governments with the political justification to implement economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism ...

, which was to dominate economic policy from the 1830s. Although utilitarianism prompted legislative and administrative reform and John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

's later writings on the subject foreshadowed the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

, it was mainly used as a justification for ''laissez-faire''.

Political economy