Chuvash language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chuvash ( , ; , , ) is a

According to Krueger (1961), the Chuvash vowel system is as follows (the precise IPA symbols are chosen based on his description since he uses a different transcription).

András Róna-Tas (1997) provides a somewhat different description, also with a partly idiosyncratic transcription. The following table is based on his version, with additional information from Petrov (2001). Again, the IPA symbols are not directly taken from the works so they could be inaccurate.

The vowels ӑ and ӗ are described as reduced, thereby differing in

According to Krueger (1961), the Chuvash vowel system is as follows (the precise IPA symbols are chosen based on his description since he uses a different transcription).

András Róna-Tas (1997) provides a somewhat different description, also with a partly idiosyncratic transcription. The following table is based on his version, with additional information from Petrov (2001). Again, the IPA symbols are not directly taken from the works so they could be inaccurate.

The vowels ӑ and ӗ are described as reduced, thereby differing in

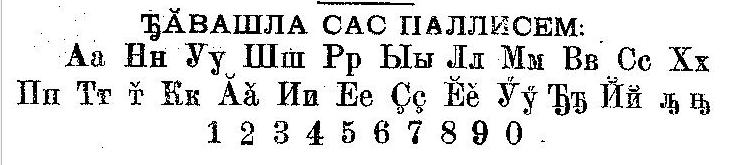

The modern Chuvash alphabet was devised in 1873 by school inspector Ivan Yakovlevich Yakovlev.

In 1938, the alphabet underwent significant modification which brought it to its current form.

The modern Chuvash alphabet was devised in 1873 by school inspector Ivan Yakovlevich Yakovlev.

In 1938, the alphabet underwent significant modification which brought it to its current form.

1. The Sun has two wives: Dawn and Afterglow (lit. "the Morning Glow" and "the Evening Glow").

2. Ир пулсан Хӗвел Ирхи Шуҫӑмран уйрӑлса каять

2. When it is morning, the Sun leaves Dawn

3. те яра кун тӑршшӗпе Каҫхи Шуҫӑм патнелле сулӑнать.

3. and during the whole day (he) moves towards Afterglow.

4. Ҫак икӗ мӑшӑрӗнчен унӑн ачасем:

4. From these two spouses of his, he has children:

5. Этем ятлӑ ывӑл тата Сывлӑм ятлӑ хӗр пур.

5. a son named Etem (Human) and a daughter named Syvlăm (Dew).

6. Этемпе Сывлӑм пӗррехинче Ҫӗр чӑмӑрӗ ҫинче тӗл пулнӑ та,

6. Etem and Syvlăm once met on the globe of the Earth,

7. пӗр-пӗрне юратса ҫемье чӑмӑртанӑ.

7. fell in love with each other and started a family.

8. Халь пурӑнакан этемсем ҫав мӑшӑрӑн тӑхӑмӗсем.

8. The humans who live today are the descendants of this couple.

"The phonetics of Chuvash stress: implications for phonology"

Proceedings of the XIV International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, 539–542. Berkeley: University of California. * Johanson, Lars & Éva Agnes Csató, ed. (1998). ''The Turkic languages''. London: Routledge. * * * * Johanson, Lars (2007). Chuvash. ''Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics''. Oxford:

Chuvash–Russian On-Line Dictionary

Chuvash English On-Line Dictionary

Chuvash People's Website

, also available in Chuvash, Esperanto and Russian (contains Chuvash literature)

''Nutshell Chuvash'', by András Róna-Tas

''Chuvash people and language'' by Éva Kincses Nagy, Istanbul Erasmus IP 1- 13. 2. 2007

''Chuvash manual online''

The Chuvash-Russian bilingual corpus

Translations of works by Alexander Pushkin into Chuvash

Chuvash literature blog

* [http://chuvash.org/content%2F3037-На%20чувашском%20конь%20еще%20не%20валялся....html Виталий Станьял: На чувашском конь еще не валялся...]

Виталий Станьял: Решение Совета Аксакалов ЧНК

* ttps://chuvash.org/news/17092.html Чӑваш чӗлхине Страсбургра хӳтӗлӗҫ

Тутарстанра чӗлхе пирки сӑмахларӗҫ

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20181026182747/https://www.idelreal.org/a/27902182.html Why don't Chuvash people speak Chuvash?

"As it is in the Chuvash Republic the Chuvash are not needed?!"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chuvash Language Agglutinative languages Chuvash people Languages of Russia Vowel-harmony languages Oghur languages Turkic languages

Turkic language

The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic langua ...

spoken in European Russia

European Russia is the western and most populated part of the Russia, Russian Federation. It is geographically situated in Europe, as opposed to the country's sparsely populated and vastly larger eastern part, Siberia, which is situated in Asia ...

, primarily in the Chuvash Republic

Chuvashia, officially known as Chuvash Republic — Chuvashia, is a republics of Russia, republic of Russia located in Eastern Europe. It is the homeland of the Chuvash people, a Turkic languages, Turkic ethnic group. Its capital city, capital i ...

and adjacent areas. It is the only surviving member of the Oghur branch of Turkic languages, one of the two principal branches of the Turkic family.

The writing system for the Chuvash language is based on the Cyrillic script

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic languages, Slavic, Turkic languages, Turkic, Mongolic languages, Mongolic, Uralic languages, Uralic, C ...

, employing all of the letters used in the Russian alphabet

The Russian alphabet (, or , more traditionally) is the script used to write the Russian language.

The modern Russian alphabet consists of 33 letters: twenty consonants (, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ), ten vowels (, , , , , , , , , ) ...

and adding four letters of its own: Ӑ, Ӗ, Ҫ and Ӳ.

Distribution

Chuvash is the native language of theChuvash people

The Chuvash people (, ; , ) also called Chuvash Tatars, are a Turkic ethnic group, a branch of the Oğurs, inhabiting an area stretching from the Idel-Ural region to Siberia.

Most of them live in the Russian republic of Chuvashia and the ...

and an official language of Chuvashia

Chuvashia, officially known as Chuvash Republic — Chuvashia, is a republics of Russia, republic of Russia located in Eastern Europe. It is the homeland of the Chuvash people, a Turkic languages, Turkic ethnic group. Its capital city, capital i ...

. There are contradictory numbers regarding the number of people able to speak Chuvash nowadays; some sources claim it is spoken by 1,640,000 persons in Russia and another 34,000 in other countries and that 86% of ethnic Chuvash and 8% of the people of other ethnicities living in Chuvashia claimed knowledge of Chuvash language during the 2002 census. However, other sources claim that the number of Chuvash speakers is on the decline, with a drop from 1 million speakers in 2010 to 700,000 in 2021; observers suggest this is due to Moscow having a lack of interest in preserving the language diversity in Russia. Although Chuvash is taught at schools and sometimes used in the media, it is considered endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching, inv ...

by the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

, because Russian dominates in most spheres of life and few children learning the language are likely to become active users.

A fairly significant production and publication of literature in Chuvash still continues. According to UNESCO's ''Index Translationum'', at least 202 books translated from Chuvash were published in other languages (mostly Russian) since ca. 1979. However, as with most other languages of the former USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, most of the translation activity took place before the dissolution of the USSR

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Dissolution'', a 2002 novel by Richard Lee Byers in the War of the Spider Queen series

* Dissolution (Sansom novel), ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), by C. J. Sansom, 2003

* Dissolution (Binge no ...

: out of the 202 translations, 170 books were published in the USSR and just 17, in the post-1991 Russia (mostly, in the 1990s). A similar situation takes place with the translation of books from other languages (mostly Russian) into Chuvash (the total of 175 titles published since ca. 1979, but just 18 of them in post-1991 Russia).

Classification

Chuvash is the most distinctive of theTurkic languages

The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic langua ...

and cannot be understood by other Turkic speakers, whose languages have varying degrees of mutual intelligibility

In linguistics, mutual intelligibility is a relationship between different but related language varieties in which speakers of the different varieties can readily understand each other without prior familiarity or special effort. Mutual intelli ...

within their respective subgroups. Chuvash is classified, alongside the long-extinct Bulgar, as a member of the Oghuric branch of the Turkic language family, or equivalently, the sole surviving descendant of West Old Turkic. Since the surviving literary records for the non-Chuvash members of Oghuric ( Bulgar and possibly Khazar

The Khazars ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a nomadic Turkic people who, in the late 6th century CE, established a major commercial empire covering the southeastern section of modern European Russia, southern Ukraine, Crimea, an ...

) are scant, the exact position of Chuvash within the Oghuric family cannot be determined.

Despite grammatical similarity with the rest of Turkic language family, the presence of changes in Chuvash pronunciation (which are hard to reconcile with other members of the Turkic family) has led some scholars to see Chuvash as originating not from Proto-Turkic but from another proto-language spoken at the time of Proto-Turkic (in which case Chuvash and all the remaining Turkic languages would be part of a larger language family).

Italian historian and philologist Igor de Rachewiltz noted a significant distinction of the Chuvash language from other Turkic languages. According to him, the Chuvash language does not share certain common characteristics with Turkic languages to such a degree that some scholars consider Chuvash as an independent branch from Turkic and Mongolic. The Turkic classification of Chuvash was seen as a compromise solution for classification purposes.

The Oghuric branch is distinguished from the rest of the Turkic family (the Common Turkic languages

Common Turkic, or Shaz Turkic, is a taxon in some classifications of the Turkic languages that includes all of them except the Oghuric languages which had diverged earlier.

Classification

Lars Johanson, Lars Johanson's proposal contains the follo ...

) by two sound change

In historical linguistics, a sound change is a change in the pronunciation of a language. A sound change can involve the replacement of one speech sound (or, more generally, one phonetic feature value) by a different one (called phonetic chan ...

s: ''r'' corresponding to Common Turkic ''z'' and ''l'' corresponding to Common Turkic ''š''. The first scientific fieldwork description of Chuvash, by August Ahlqvist in 1856, allowed researchers to establish its proper affiliation.

Some scholars suggest Hunnish had strong ties with Chuvash and classify Chuvash as separate Hunno-Bulgar. However, such speculations are not based on proper linguistic evidence, since the language of the Huns is almost unknown except for a few attested words and personal names. Scholars generally consider Hunnish as unclassifiable. Chuvash is so divergent from the main body of Turkic languages that some scholars formerly considered Chuvash to be a Uralic language. Conversely, other scholars today regard it as an Oghuric language significantly influenced by the Finno-Ugric

Finno-Ugric () is a traditional linguistic grouping of all languages in the Uralic languages, Uralic language family except for the Samoyedic languages. Its once commonly accepted status as a subfamily of Uralic is based on criteria formulated in ...

languages.

The following sound changes and resulting sound correspondences are typical:Agyagási (2019: passim)

Most of the (non-allophonic) consonant changes listed in the table above are thought to date from the period before the Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic peoples, Turkic Nomad, semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region between the 5th and 7th centu ...

migrated to the Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

region in the 10th century; some notable exceptions are the ''č'' > ''ś'' shift and the final stage of the ''-d'' > ''-ð'' > ''-z'' > ''-r'' shift, which date from the following, Volga Bulgar period (between the 10th-century migration and the Mongol invasions of the 13th century). The vowel changes mostly occurred later, mainly during the Middle Chuvash period (between the invasions and the 17th century), except for the diphthongisation, which took place during the Volga Bulgar period. Many sound changes known from Chuvash can be observed in Turkic loanwords into Hungarian (from the pre-migration period) and in Volga Bulgar epitaphs or loanwords into languages of the Volga region (from the Volga Bulgar period). Nevertheless, these sources also indicate that there was significant dialectal variation within the Oguric-speaking population during both of these periods.

Comparison

In the 8-10th centuries in Central Asia, the ancient Turkic script (the Orkhon-Yenisei runic script) was used for writing in Turkic languages. Turkic epitaphs of 7-9th centuries AD were left by speakers of various dialects (table): * Often in the Chuvash language, the Common Turkic sounds of /j/ (''Oghuz''), /d/ (''Karluk''), /z/ (''Kipchak'') are replaced by /r/, example '' rhotacism'': Words for "leg" and "put" in various Turkic languages: j - languages (Oguz): ''ayaq, qoy-'' d - languages (Karluk): ''adaq, qod-'' z - languages (Kypchak): ''azaq, qoz-'' r - languages (Oghur): ''ura, hur- ( dial. ora, hor-)'' * Often in the Chuvash language, the Turkic sound /q/ is replaced by /x/, example ''hitaism'': Comparison table Сhitacism (Q > H) * The -h- sound disappears if it is the final sound of a syllable. ''Dudaq - Tuta - Lips'' instead of ''Tutah'' ''Ayaq - Ura - Leg'' instead of ''Urah'' ''Balıq - Pulă - Fish'' instead of ''Pulăh'' ''İnek'' - ''Ĕne - Cow'' instead of ''Ĕneh'' * Turkic sound -y- (''oguz'') and -j- (''kipchaks'') is replaced by chuvash -''ş''-, example: Words in Turkic languages: ''egg, snake, rain, house, earth'' Oguz: ''yumurta, yılan, yağmur, yurt, yer (''turk., azerb.'')'' Kipchaks: ''jumırtqa, jılan, jañğır, jurt, jer (''kyrgyz., kazakh.'')'' Chuvash: ''şămarta, şĕlen, şămăr, şurt, şĕr'' * The Turkic sound -ş- is replaced by the Chuvash -L-, example ''lambdaism'': Comparison table * In the field of vowels, we observe the following correspondences: the common Turkic -a- in the first syllable of the word in Chuvash correspond to -u- and -o-. Comparison table In modern times, in Chuvash remains, Tatar "kapka" ~ Chuvash "hapha" (gate), when there should be a "''hupha''" from the root "''hup - close''". * In the field of vowels, G. F. Miller observes another example when -u- is replaced by -wu- or -wă- Comparison table * The fricative -g- in some words in Chuvash corresponds to -v- Comparison table Ogur and Oguz It is well known that the '' Oghuz'' group of Turkic languages differs from the '' Kipchak'' in that the word “I” was pronounced by the Oghuz''es'' and Oghurs in ancient times by "''bä(n)"'', and the rest of the Turks - by "''män".'' There is such a difference in the modern Turkic languages of the Volga region: tat., bash. ''Min'', ogur/chuv. ''Epĕn'' (< *pen), turk. ''Ben'', eng. «''I am''»; tat., bash. ''Mең'', ogur/chuv. ''Piń,'' turk. ''Bin,'' eng. «thousand»; tat., bash. Milәş, ogur/chuv. Pileš, eng. «rowan»; tat. ''Мәçe'', ogur/chuv. ''Pĕşi, Pĕşuk,'' az. ''Pişik,'' eng. «cat»; ,Dialects

The linguistic landscape of the Chuvash language is quite homogeneous, and the differences between dialects are insignificant. Currently, the differences between dialects becoming more and more leveled out. Researchers distinguish three main dialects: * Upper dialect (Viryal) - upstream of the Sura, preserves the /o/ sound in words like ''ot'' "horse" * Middle dialect (mixed, transitional); * Lower dialect (Anatri) - downstream of the Sura, changes the /o/ sound to /u/ in words like ''ut'' "horse" The ''Malokarachinsky dialect'' is designated as occupying a separate position. The literary language is based on both the Lower and Upper dialects. Both Tatar and the neighbouringUralic languages

The Uralic languages ( ), sometimes called the Uralian languages ( ), are spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers ab ...

such as Mari have influenced the Chuvash language, as have Russian, Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

and Persian, which have all added many words to the Chuvash lexicon.

All dialects established to date have their own sub-dialects, which have their own exceptional features and peculiarities, thereby they are divided into even smaller dialect forms. The following dialect ramifications in the Chuvash language have been identified:

1) as part of the upper dialect, the subdialects are: a) Sundyrsky; b) Morgaussko-Yadrinsky; c) Krasnochetaysky; d) Cheboksary; e) Kalininsko-Alikovsky;

2) in the zone of the middle dialect: a) Malocivilsky; b) Urmarsky; c) civil-marposadsky;

3) in the zone of the grassroots dialect: a) Buin-Simbirsk; b) Nurlatsky (prichemshanye);

Phonetic differences:

a) All words of the Upper dialect (except exc. Kalinin-Alikov subgroup) in the initial syllable, instead of the "lower" sound -U- is used -O- for example:

In English: ''yes, six, found''

in Turi: ''por, olttă, toprăm''

in Anatri: ''pur, ulttă, tuprăm''

b) In the upper dialect in the Sundyr sub-dialect, instead of the sound -ü- (used in all other dialects), the sound -ö- is used, which is a correlative soft pair of the posterior -o-, for example:

in English: ''hut, back, broth''

in Turi: ''pӧrt, tӧrt, šӧrpe''

in Anatri: ''pürt, türt, šürpe''

с) In the upper dialect (in most sub-dialects) the loss of the sound -j- before the sonorant -l-, -n-, -r- and stop -t- is characterized, which in turn entails palatalization of these consonants, for example:

in English: ''russian woman, choose''

in Turi: ''mar'a, sul'l'a''

in Anatri: ''majra, sujla''

d) In the higher dialect (for most sub-dialects), gemination

In phonetics and phonology, gemination (; from Latin 'doubling', itself from '' gemini'' 'twins'), or consonant lengthening, is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct from ...

of intervocalic consonants is characteristic, as in the Finnish language, for example:

in English: ''shawl, drunk, crooked''

in Turi: ''tottăr, ĕssĕr, kokkăr''

in Anatri: ''tutăr, üsĕr, kukăr''

In general, gemination

In phonetics and phonology, gemination (; from Latin 'doubling', itself from '' gemini'' 'twins'), or consonant lengthening, is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct from ...

itself is the norm for the Chuvash language, since many historically root words in both dialects contain gemination, for example: ''anne (mather), atte (father), piççe (brother), appa (sister), kukka (uncle), pĕrre (one), ikkĕ (two), vişşĕ (three), tăvattă (four), pillĕk (five), ulttă (six), şiççĕ (seven), sakkăr (eight), tăhhăr (nine), vunnă (ten),'' etc. Some linguists are inclined to assume that this is the influence of the Volga Finns

The Volga Finns are a historical group of peoples living in the vicinity of the Volga, who speak Uralic languages. Their modern representatives are the Mari people, the Erzya and the Moksha (commonly grouped together as Mordvins) as well as ...

at the turn of the 7th century when the ancestors of the Chuvash moved to the Volga, there are those who disagree with this statement. In one of the subgroups of the Trans-Kama Chuvash, in the same words there is no gemination at all, for example, the word father is pronounced as Adi, and mother as Ani, their counting looks like this: ''pĕr, ik, viş, tvat, pül, ulta, şiç, sagăr, tăgăr, vun'' - but many scientists assume that this is a consequence of the influence of the Tatar language. They also have many words in the Tatar style, the word “hare - kuşana” (tat.kuyan) is “mulkaç” for everyone, “pancakes - kuymak” for the rest is ikerçĕ, “cat - pĕşi” for the rest is “saş”, etc.

e) In the middle and upper dialects there are rounded vowels -ă°-, -ĕ°- (pronounced with the lips rounded and slightly pulled forward), in the lower dialect this is not observed, here they correspond to the standard sounds -ă-, -ĕ-.

f) In the upper and lower dialects, consonantism is distinguished by the pronunciation of the affricate sound -ç-. Among the upper Chuvash and speakers of the middle dialect, the sound -ç- is almost no different from the pronunciation of the Russian affricate; in the lower dialect it is heard almost like a soft -ç-, as in the Tatar language.

Morphological differences:

a) In the upper dialect there are synharmonic variants of the plural affix ''-sam/-sem,'' and in the lower dialect only ''-sem'', for example:

in English: ''horses, sheep, meadows, cows, flowers''

in Turi: ''lašasam, surăhsam, şaramsam, ĕnesem, çeçeksem''

in Anatri: ''lašasem, surăhsem, şeremsem, ĕnesem, çeçeksem''

b) In the upper dialect (in most sub-dialects) the affix of the possessive case is ''-yăn (-yĕn)'', the dative case is ''-ya (-ye)'', while in the lower dialect ''-năn (-nĕn, -n), -na (-ne)'', For example:

in Turi: ''lašayăn, ĕneyĕn, lašaya, ĕneya, ĕneye''

in Anatri: ''lašan(ăn), ĕnen(ĕn), lašana, ĕnene''

c) in the upper dialect, affixes of belonging, with the exception of the 3rd person affix ''-i (-ĕ)'', have almost fallen out of use or are used extremely rarely. In the latter case, the 2nd person affix ''-u (-ü)'' of the upper dialect usually corresponds to ''-ă (-ĕ)'' in the lower dialect;

in English: ''your head, your daughter''

in Turi: ''san puşu, san hĕrü''

in Anatri: ''san puşă, san hĕrĕ''

There is also a mixed type

d) In the upper dialect, the gemination

In phonetics and phonology, gemination (; from Latin 'doubling', itself from '' gemini'' 'twins'), or consonant lengthening, is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct from ...

of the temporal index ''-t-'' and ''-p-'' is used in the affixes of the 2nd person plural of the verb of the present tense, for example:

in English: ''are you reading, we are going''

in Turi: ''esĕr vulattăr, epĕr pırappăr''

in Anatri: ''esir vulatăr, epir pırappăr''

The influence of Russian: ''we are going < epir pıratpăr''

There is also a mixed type, as already mentioned above.

e) In the upper dialect, the affix of the possibility of verbs ''-ay (-ey)'', due to contraction, monophtongized to ''-i'':

in English: ''Couldn't tell, couldn't find out''

in Turi: ''kalimarăm, pĕlimarăm, pĕlimerĕm''

in Anatri: ''kalaymarăm, pĕleymerĕm''

f) In the upper dialect, the synharmonic variant of the interrogative particle ''-i'' is common, in the dialects of the lower dialect, variants ''-a (-e)'' are used:

in English: ''Have you left? Do you know?''

in Turi: ''esĕ kayrăn-i? esĕ pĕletĕn-i / es pĕletni?''

in Anatri: ''esĕ kayrăn-a? esĕ pĕletĕn-e? es pĕletnĕ?''

g) in the upper dialect, individual phrases turn into a complex word by shortening (contraction):

in English: apple tree, frying pan handle, earring, monkey, belt

in Turi: ''ulmuşşi (olmaşşi), şatmari, hălhanki, upăte, pişĕhe''

in Anatri: ''ulma yıvăşşi / yıvăşĕ'', ''şatma avri, hălha şakki (ear pendant), upa-etem (bear-man), pilĕk şihhi (lower back tie)''

Syntactic differences:

a) In the upper dialect (in most dialects), the adverbial participle ''-sa (-se)'' performs the function of a simple predicate, which is not allowed in the middle and lower dialects:

in English: ''I wrote''

in Turi: ''Ep şırsa''

in Anatri: ''Epĕ şırtăm''

b) In the upper dialect, analytical constructions are used instead of the lower synthetic one:

in English: ''Go to lunch, It says in the newspaper''

in Turi: ''Apat şima kilĕr, Kaşiť şinçe şırnă''

in Anatri: ''Apata kilĕr, Xaşatra şırnă''

There is also a mixed type.

Other lexical differences:

Another feature between the upper and lower dialects:

in English: ''We, you''

in Turi: ''Epĕr, Esĕr''

in Anatri: ''Epir, Esir''

There are also those grassroots Chuvash (living in Kama

''Kama'' (Sanskrit: काम, ) is the concept of pleasure, enjoyment and desire in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. It can also refer to "desire, wish, longing" in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, and Sikh literature.Monier Williamsका� ...

) with a biting dialect who use the riding version of Epĕr, Esĕr. It has been established that the correct historical form is the pronunciation of ''Epĕr, Esĕr'', A comparison with the Tatar Turkic languages, which are close to the Chuvash language, determined historical justice.

Ep / Epĕ - I, Epĕ+r - We

Es / Esĕ - You, Esĕ+r - You

Affixes -ĕr/-ăr are converted from singular to plural:

Epĕ şitrĕm - Ep+ĕr şitrĕm+ĕr / I got there - We've reached it

Epĕ şırtăt - Ep+ĕr şırtăm+ăr / I wrote - we wrote

Ham vularăm - Ham+ăr vularăm+ăr / I read it - we read it

There is no "+ir" suffix in the Chuvash language so this is a big mistake. No one says "kiltĕm+ir", vularăm+ir", çitrĕm+ir". Don't say "Hamir turăm+ir". There is a dialect with pronunciation "Ep+ĕr+ĕn" - instead of "Pir+ĕn" (our), and "Es+ĕr+ĕn" - instead of "Sir+ĕn" (your) on this we can assume that their pronunciation was historical, because the structure is more correct, but because of what evolution it transformed into "pirĕn/sirĕn".

Ep+ĕr pĕr+le - We are one

Es+ĕr ik+sĕr - The two of you

There are also very different words.

The dispute over the literary language

The modern Chuvash literary language was formed on the basis of a grassroots dialect, before this period an old literary language based on an upper dialect was in use. There are linguists who believe that the mother tongue was still the riding dialect of the Chuvash, when now it is considered to be the primary grassroots dialect. Their arguments are based on certain factors:

1) the migration of the Chuvash in the post-Horde period was from north to south, and not vice versa, the further they moved away from the root region towards the south and east, the more their language was subject to changes. Russian language was strongly influenced by the Kipchak languages (steppe raids), and after the settlement of Simbirsk by Russian people (at that time a very large city, much larger than Cheboksary), the dialect of the grassroots Chuvash in the area of Buinsk was strongly influenced by the Russian language, which is easily provable, all the most ancient records of the Chuvash language made by different travelers, such as G. F. Miller and others, contain words only of the upper-level dialect and not one of the lower-level. .

2) The U-dialect of the grassroots Chuvash has undergone influence from the Northern Kipchak vowel raising, whereas the O-dialect has preserved the Common Turkic vowels.

3) One of the rules says that the sound -T- standing at the end of a borrowed word in Chuvash falls out, for example: ''friend - dust - tus, cross - krest - hĕres...'' The auslaut is not pronounced in oral speech, it disappears in the position after the consonant (the latter in this case is replaced by a soft �: ''vlast' ~ vlaş, vedomost' - vetămăş, volost' - vulăs, pakost' - pakăş, sançast' - sançaş, oblast' - oblaş.'' In addition, the affixal is not pronounced orally and in certain verb forms established as a literary language: ''pulmast' < ulmaş~ It doesn't happen,'' the correct historical form: "''pulmas".'' As well ''kurmast' < urmaş~ He doesn't see it,'' the correct historical form: "kurmas". As well ''kilmest' < ilmeş~ It doesn't come,'' the correct historical form: "''kilmes"''. The historically correct affix is "-mas/-mes", instead of "-mast'/-mest' ", which appeared as a result of the influence of the Russian language. As is known, the form with the ending ''-st and ''-st'' is not peculiar to the Chuvash language by its nature, which means it is a late influence of the Russian language on the dialect of the lower Chuvash. Affixes: -mes/-mas, -mep/-map, -men/-man.

4) In most dialects, palatalizes only when it is preceded by the front vowels: ''kileť, pereť, ükeť, kĕteť.'' If is preceded by the back vowels, it doesn't palatalize: ''yurat, kalat, urat, păhat, kayat''. In the grassroots dialect, all the end T's soften.

5) A simple shortened address in the literary language has become unacceptable, only respectful treatment has been left with the correct pronunciation: Instead of "Es yuratan" - "Esĕ yuratatăn" - "do you love". "Ep pırap" - "Epĕ pıratăp" - "I'm coming".

6) Instead of the supreme dialect "Kaya''pp''ăr - we go away, Uta''pp''ăr - we come, Vula''pp''ăr - we read", it is customary to write and speak in a grassroots dialect subject to Russification: " Kaya''tp''ăr, Uta''tp''ăr, Vula''tp''ăr".

*There is also a mixed type, where all variants of the case are used at once, this is especially noticeable in those settlements that arose at the turn of the 17th-20th centuries, such villages created by combining speakers of upper and lower dialects gave birth to a more universal dialect where both options were used .

Phonology

Consonants

The consonants are the following (the corresponding Cyrillic letters are in brackets): The stops,sibilant

Sibilants (from 'hissing') are fricative and affricate consonants of higher amplitude and pitch, made by directing a stream of air with the tongue towards the teeth. Examples of sibilants are the consonants at the beginning of the English w ...

s and affricate

An affricate is a consonant that begins as a stop and releases as a fricative, generally with the same place of articulation (most often coronal). It is often difficult to decide if a stop and fricative form a single phoneme or a consonant pai ...

s are voiceless

In linguistics, voicelessness is the property of sounds being pronounced without the larynx vibrating. Phonologically, it is a type of phonation, which contrasts with other states of the larynx, but some object that the word phonation implies v ...

and fortes but become lenes (sounding similar to voiced

Voice or voicing is a term used in phonetics and phonology to characterize speech sounds (usually consonants). Speech sounds can be described as either voiceless (otherwise known as ''unvoiced'') or voiced.

The term, however, is used to refe ...

) in intervocalic position and after liquid

Liquid is a state of matter with a definite volume but no fixed shape. Liquids adapt to the shape of their container and are nearly incompressible, maintaining their volume even under pressure. The density of a liquid is usually close to th ...

s, nasals and semi-vowel

In phonetics and phonology, a semivowel, glide or semiconsonant is a sound that is phonetically similar to a vowel sound but functions as the syllable boundary, rather than as the nucleus of a syllable. Examples of semivowels in English are ''y' ...

s. Аннепе sounds like ''annebe'', but кушакпа sounds like ''kuzhakpa''. However, geminate consonant

In phonetics and phonology, gemination (; from Latin 'doubling', itself from '' gemini'' 'twins'), or consonant lengthening, is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct from ...

s do not undergo this lenition. Furthermore, the voiced consonants occurring in Russian are used in modern Russian-language loans. Consonants also become palatalized before and after front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned approximately as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction th ...

s. However, some words like пульчӑклӑ "dirty", present palatalized consonants without preceding or succeeding front vowels, and should be understood that such are actually phonemic:

* can have a voiced allophone of .

Vowels

According to Krueger (1961), the Chuvash vowel system is as follows (the precise IPA symbols are chosen based on his description since he uses a different transcription).

András Róna-Tas (1997) provides a somewhat different description, also with a partly idiosyncratic transcription. The following table is based on his version, with additional information from Petrov (2001). Again, the IPA symbols are not directly taken from the works so they could be inaccurate.

The vowels ӑ and ӗ are described as reduced, thereby differing in

According to Krueger (1961), the Chuvash vowel system is as follows (the precise IPA symbols are chosen based on his description since he uses a different transcription).

András Róna-Tas (1997) provides a somewhat different description, also with a partly idiosyncratic transcription. The following table is based on his version, with additional information from Petrov (2001). Again, the IPA symbols are not directly taken from the works so they could be inaccurate.

The vowels ӑ and ӗ are described as reduced, thereby differing in quantity

Quantity or amount is a property that can exist as a multitude or magnitude, which illustrate discontinuity and continuity. Quantities can be compared in terms of "more", "less", or "equal", or by assigning a numerical value multiple of a u ...

from the rest. In unstressed positions, they often resemble a schwa or tend to be dropped altogether in fast speech. At times, especially when stressed, they may be somewhat rounded and sound similar to and .

Additionally, (о) occurs in loanwords from Russian where the syllable is stressed in Russian.

Word accent

The usual rule given in grammars of Chuvash is that the last full (non-reduced) vowel of the word is stressed; if there are no full vowels, the first vowel is stressed. Reduced vowels that precede or follow a stressed full vowel are extremely short and non-prominent. One scholar, Dobrovolsky, however, hypothesises that there is in fact no stress in disyllabic words in which both vowels are reduced.Morphonology

Vowel harmony

Vowel harmony

In phonology, vowel harmony is a phonological rule in which the vowels of a given domain – typically a phonological word – must share certain distinctive features (thus "in harmony"). Vowel harmony is typically long distance, meaning tha ...

is the principle by which a native Chuvash word generally incorporates either exclusively back or hard vowels (а, ӑ, у, ы) and exclusively front or soft vowels (е, ӗ, ӳ, и). As such, a Chuvash suffix such as -тен means either -тан or -тен, whichever promotes vowel harmony; a notation such as -тпӗр means either -тпӑр, -тпӗр, again with vowel harmony constituting the deciding factor.

Chuvash has two classes of vowels: ''front'' and ''back'' (see the table above). Vowel harmony states that words may not contain both front and back vowels. Therefore, most grammatical suffixes come in front and back forms, e.g. Шупашкарта, "in Cheboksary" but килте, "at home".

Two vowels cannot occur in succession.

=Exceptions

= Vowel harmony does not apply for some invariant suffixes such as the plural ending -сем and the 3rd person (possessive or verbal) ending -ӗ, which only have a front version. It also does not occur in loanwords and in a few native Chuvash words (such as анне "mother"). In such words suffixes harmonize with the final vowel; thus Аннепе "with the mother". Compound words are considered separate words with respect to vowel harmony: vowels do not have to harmonize between members of the compound (so forms like сӗтел, пукан "furniture" are permissible).Other processes

The consonant т often alternates with ч before ӗ from original *''i'' (ят 'name' - ячӗ 'his name'). There is also an alternation between т (after consonants) and р (after vowels): тетел 'fishing net (nom.)' - dative тетел-те, but пулӑ 'fish (nom.)' - dative пулӑ-ра.Róna-Tas (1997: 4) Consonants In the Chuvash orthography, the fortis and lenis consonants are not differentiated, because their changes are very straightforward. Therefore, only voiceless consonants are written. Voicing also occurs on word boundaries:Writing systems

Official

Letters in bold are solely used in loanwords.Latin alphabet

Latin alphabet used by Chuvash people living in the USA and Europe, used for the convenience of writing Chuvash words: Examples of written text: Transliteration of the Chuvash alphabet1873–1938

Previous systems

The most ancient writing system, known as the Old Turkic alphabet, disappeared after theVolga Bulgars

Volga Bulgaria or Volga–Kama Bulgaria (sometimes referred to as the Volga Bulgar Emirate) was a historical Bulgar state that existed between the 9th and 13th centuries around the confluence of the Volga and Kama River, in what is now Europea ...

converted to Islam. Later, the Arabic script

The Arabic script is the writing system used for Arabic (Arabic alphabet) and several other languages of Asia and Africa. It is the second-most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world (after the Latin script), the second-most widel ...

was adopted. After the Mongol invasion

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire, the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), which by 1260 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastati ...

, writing degraded. After Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

's reforms Chuvash elites disappeared, blacksmiths and some other crafts were prohibited for non-Russian nations, the Chuvash were educated in Russian, while writing in runes recurred with simple folk.

Grammar

As characteristic of all Turkic languages, Chuvash is anagglutinative language

An agglutinative language is a type of language that primarily forms words by stringing together morphemes (word parts)—each typically representing a single grammatical meaning—without significant modification to their forms ( agglutinations) ...

and as such, has an abundance of suffix

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns and adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can ca ...

es but no native prefixes or prepositions, apart from the partly reduplicative intensive

In grammar, an intensive word form is one which denotes stronger, more forceful, or more concentrated action relative to the root on which the intensive is built. Intensives are usually lexical formations, but there may be a regular process for for ...

prefix, such as in: - ''white'', - ''snow-white'', - ''black'', - ''jet black'', - ''flat'', - ''absolutely flat'', - ''full'', - ''chock full'' (compare to Turkish - ''white'', ''snow-white'', - ''black'', - ''jet black'', - ''flat'', - ''absolutely flat'', - ''full'', - ''chock full''). One word can have many suffixes, which can also be used to create new words like creating a verb from a noun or a noun from a verbal root. See Vocabulary

A vocabulary (also known as a lexicon) is a set of words, typically the set in a language or the set known to an individual. The word ''vocabulary'' originated from the Latin , meaning "a word, name". It forms an essential component of languag ...

below. It can also indicate the grammatical function of the word.

Nominals

Nouns

Chuvash nouns decline in number and case and also take suffixes indicating the person of a possessor. The suffixes are placed in the order possession - number - case. There are six noun cases in the Chuvash declension system: In the suffixes where the first consonant varies between р- and т-, the allomorphs beginning in т- are used after stems ending in the dental sonorants -р, -л and -н. The allomorphs beginning in р- occur under all other circumstances. The dative-accusative allomorph beginning in н- is mostly used after stems ending in vowels, except in -и, -у, and -ӑ/-ӗ, whereas the one consisting only of a vowel is used after stems ending in consonants. The nominative is used instead of the dative-accusative to express indefinite or general objects, e.g. утӑ типӗт 'to dry hay'. It can also be used instead of the genitive to express a possessor, so that the combination gets a generalised compound-like meaning (лаша пӳҫӗ 'a horse head' vs лашан пӳҫӗ 'the horse's head'); with both nominative and genitive, however, the possessed noun has a possessive suffix (see below). In the genitive and dative-accusative cases, some nouns ending in -у and -ӳ were changed to -ӑв and -ӗв (ҫыру → ҫырӑван, ҫырӑва, but ҫырура; пӳ → пӗвен, пӗве, but пӳре). In nouns ending in -ӑ, the last vowel simply deletes and may cause the last consonant to geminate (пулӑ 'fish' > пуллан). Nouns ending in consonants sometimes also geminate the last letter (ҫын 'man' → ҫыннан). There are also some rarer cases, such as: * Terminative– antessive (to), formed by adding -(ч)чен * relic of distributive, formed by adding -серен: кунсерен "daily, every day", килсерен "per house", килмессерен "every time one comes" * Semblative (as), formed by adding пек to pronouns in genitive or objective case (ман пек, "like me", сан пек, "like you", ун пек, "like him, that way", пирӗн пек, "like us", сирӗн пек, "like you all", хам пек, "like myself", хӑвӑн пек, "like yourself", кун пек, "like this"); adding -ла, -ле to nouns (этемле, "humanlike", ленинла, "like Lenin") * Postfix: ха (ha); adding -шкал, -шкел to nouns in the dative (actually a postposition, but the result is spelt as one word: унашкал 'like that'). Taking кун (day) as an example: Possession is expressed by means of constructions based on verbs meaning "to exist" and "not to exist" ("пур" and "ҫук"). For example, to say, "The cat had no shoes": : : which literally translates as "cat-of foot-cover(of)-plural-his non-existent-was." The possessive suffixes are as follows (ignoring vowel harmony): Stem-final vowels are deleted when the vowel-initial suffixes (-у, -и, -ӑр) are added to them. The 3rd person allomorph -ӗ is added to stems ending in consonants, whereas -и is used with stems ending in vowels. There is also another postvocalic variant -шӗ, which is used only in designations of family relationships: аппа 'elder sister' > аппа-шӗ. Furthermore, the noun атте 'father' is irregularly declined in possessive forms: When case endings are added to the possessive suffixes, some changes may occur: the vowels comprising the 2nd and 3rd singular possessive suffixes are dropped before the dative-accusative suffix: (ывӑл-у-на 'to your son', ывӑл-ӗ-нe 'to his son' > ывӑлна, ывӑлнe), whereas a -н- is inserted between them and the locative and ablative suffixes: ывӑл-у-н-та 'in/at your son', ывӑл-ӗ-н-чен 'from his son'.Adjectives

Adjectives do not agree with the nouns they modify, but may receive nominal case endings when standing alone, without a noun. The comparative suffix is -рах/-рех, or -тарах/терех after stems ending in -р or, optionally, other sonorant consonants. The superlative is formed by encliticising or procliticising the particles чи or чӑн to the adjective in the positive degree. A special past tense form meaning '(subject) was A' is formed by adding the suffix -(ч)чӗ. Another notable feature is the formation of intensive forms via complete or partial reduplication: кǎтра 'curly' - кǎп-кǎтра 'completely curly'.The 'separating' form

Both nouns and adjectives, declined or not, may take special 'separating' forms in -и (causing gemination when added to reduced vowel stems and, in nouns, when added to consonant-final stems) and -скер. The meaning of the form in -и is, roughly, 'the one of them that is X', while the form in -скер may be rendered as '(while) being X'. For example, пӳлӗм-р(е)-и-сем 'those of them who are in the room'. The same suffixes may form the equivalent of dependent clauses: ачисем килте-скер-ӗн мӗн хуйхӑрмалли пур унӑн? 'If his children (are) at home, what does he have to be sad about?', йӗркеллӗ çынн-и курӑнать 'You (can) see that he is a decent person', эсӗ килт(e)-и савӑнтарать (lit. 'That you are at home, pleases one').Pronouns

The personal pronouns exhibit partly suppletive allomorphy between the nominative and oblique stems; case endings are added to the latter: Demonstratives are ку 'this', çак 'this' (only for a known object), çав 'that' (for a somewhat remote object), леш 'that' (for a remote object), хай 'that' (the above-mentioned). There is a separate reflexive originally consisting of the stem in х- and personal possessive suffixes: Interrogatives are кам 'who', мӗн 'what', хаш/хӑшӗ 'which'. Negative pronouns are formed by adding the prefix ни- to the interrogatives: никам, ним(ӗн), etc. Indefinite pronouns use the prefix та-: такам etc. Totality is expressed by пур 'all', пӗтӗм 'whole', харпӑр 'every'. Among the pronominal adverbs that are not productively formed from the demonstratives, notable ones are the interrogatives хăçан 'when' and ăçта 'where'.Verbs

Chuvash verbs exhibit person and can be made negative or impotential; they can also be made potential. Finally, Chuvash verbs exhibit various distinctions of tense, mood and aspect: a verb can be progressive, necessitative, aorist, future, inferential, present, past, conditional, imperative or optative. The sequence of verbal suffixes is as follows: voice - iterativity - potentiality - negation - tense/gerund/participle - personal suffix.Павлов (2017: 251)Finite verb forms

The personal endings of the verb are mostly as follows (abstracting from vowel harmony): The 1st person allomorph containing -п- is found in the present and future tenses, the one containing -м- is found in other forms. The 3rd singular is absent in the future and in the present tenses, but causes palatalisation of the preceding consonant in the latter. The vowel-final allomorph of the 3rd plural -ҫӗ is used in the present. The imperative has somewhat more deviant endings in some of its forms: To these imperative verb forms, one may add particles expressing insistence (-сам) or, conversely, softness (-ччӗ) and politeness (-ах). The main tense markers are: The consonant -т of the present tense marker assimilates to the 3rd plural personal ending: -ҫҫĕ. The past tense allomorph -р- is used after vowels, while -т- is used after consonants. The simple past tense is used only for witnesses events, whereas retold events are expressed using the past participle suffix -н(ӑ) (see below). In addition to the iterative past, there is also an aspectual iterative suffix -кала- expressing repetitive action. There are also modal markers, which do not combine with tense markers and hence have sometimes been described as tenses of their own: The concessive suffix -ин is added after the personal endings, but in the 2nd singular and plural, a -с- suffix is added ''before'' them: кур-ӑ-сӑн(-ин) 'alright, see it'. If the particle -ччӗ is added, the meaning becomes optative. Potentiality is expressed with the suffix -(а)й 'be able to'. The negative is expressed by a suffix inserted before the tense and modal markers. It contains -м- and mostly has the form -м(а)-, but -мас- in the present and -мӑ- in the future. The imperative uses the proclitic particle ан instead (or, optionally, an enclitic мар in the 1st person). A change of valency to a passive-reflexive 'voice' may be effected by the addition of the suffixes -ӑл- and -ӑн-, but the process is not productive and the choice of suffix is not predictable. Still, if both occur with the same stem, -ӑл- is passive and -ӑн- is reflexive. A ' reciprocal voice' form is produced by the suffixes -ӑш and -ӑҫ. There are twocausative

In linguistics, a causative (abbreviated ) is a valency-increasing operationPayne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 173–186. that indicates that a subject either ...

suffixes - a non-productive -ат/ар/ӑт and a productive -(т)тар (the single consonant allomorph occurring after monosyllabic stems).

There are, furthermore, various periphrastic constructions using the non-finite verb forms, mostly featuring predicative use of the participles (see below).

Non-finite verb forms

Some of the non-finite verb forms are: I. Attributive participles # Present participle: -акан (вӗренекен 'studying' or 'being studied'); the negative form is the same as that of the past participle (see below); # Past participle: -н(ӑ) (курнӑ 'which has seen' or 'which has been seen'); the final vowel disappears in the negative (курман) # Future participle: -ас (каяс 'who will go') # Present participle expressing a permanent characteristic: -ан (вӗҫен 'flying') # Present participle expressing pretence: -анҫи, -иш # Necessitative participle: -малла (пулмалла 'who must become'); the negative is formed by adding the enclitic мар # Satisfaction participle: -малӑх (вуламалӑх 'which is enough to be read') # Potentiality participle: -и (ути 'which can go')Róna-Tas (1997: 5) The suffix -и may be added to participles to form a verbal noun: ҫыр-нӑ; 'written' > ҫыр-н-и 'writing'. II. Adverbial participles (converb

In theoretical linguistics, a converb ( abbreviated ) is a nonfinite verb form that serves to express adverbial subordination: notions like 'when', 'because', 'after' and 'while'. Other terms that have been used to refer to converbs include ''adv ...

s)

# -са (default: doing, having done, while about to do') (-сар after a negative suffix)

# -а 'doing Y' (the verb form is usually reduplicated)

# -нӑҫем(-ен) 'the more the subject does Y':

# -уҫӑн 'while doing Y'

# -сан 'having done Y', 'if the subject does Y'

# -нӑранпа 'after/since having done Y'

# -массерен 'whenever the subject does Y'

# -иччен 'before/until doing Y'

III. Infinitives

The suffixes -ма and -машкӑн form infinitives.

There are many verbal periphrastic constructions using the non-finite forms, including:

# a habitual past using the present participle and expressing periodicity (эпĕ вулакан-ччĕ, lit. 'I was reading ne);

# an alternative pluperfect using the past participle (эпĕ чĕннĕ-ччĕ, lit. 'I asone that had called'; negated by using the negatively conjugated participle эпĕ чĕнмен-ччĕ);

# a general present equal to the present participle (эпĕ ҫыракан, lit. 'I m awriting ne; negated with the enclitic мар),

# an alternative future expressing certainty and equal to the future participle (эпĕ илес 'I mone who will get'; negated with an encliticised ҫук),

# a necessitative future using the necessitative participle (ман/эпĕ тарант(ар)малла 'I mone who must feed'; negated with мар),

# a second desiderative future expressing a wish and using the converb in -сан (эпĕ ҫĕнтерсен-ччĕ, 'I wish I'd win'),

# another desiderative form expressing a wish for the future and using the future participle followed by -чĕ (эпĕ пĕлес-чĕ 'I wish/hope I know', negated by мар with an encliticised -ччĕ).

Word order

Word order in Chuvash is generally subject–object–verb. Modifiers (adjectives and genitives) precede their heads in nominal phrases, too. The language uses postpositions, often originating from case-declined nouns, but the governed noun is usually in the nominative, e.g. тĕп çи-не 'onto (the surface of) the ground' (even though a governed ''pronoun'' tends to be in the genitive). Yes/no-questions are formed with an encliticised interrogative particle -и. The language often uses verb phrases that are formed by combining the adverbial participle in -са and certain common verbs such as пыр 'go', çӳре 'be going', кай 'go (away from the speaker)', кил 'go (towards the speaker)', ил 'take', кала 'say', тăр 'stand', юл 'stay', яр 'let go'; e.g. кĕрсe кай 'go entering > enter', тухса кай 'go exiting > leave'.Vocabulary

Numerals

The number system is decimal. The numbers from one to ten are: * 1 – pĕrre ''(пӗрре)'', pĕr ''(пӗр)'' * 2 – ikkĕ ''(иккӗ),'' ikĕ ''(икӗ)'', ik ''(ик)'' * 3 – wişşĕ ''(виҫҫӗ)'', wişĕ ''(виҫӗ)'', wiş ''(виҫ)'' * 4 – tăwattă ''(тӑваттӑ'') tvată ''(тватӑ)'', tăwat ''(тӑват),'' tvat ''(тват)'' * 5 – pillĕk ''(пиллӗк)'', pilĕk ''(пилӗк),'' pil ''(пил)'' * 6 – ulttă ''(улттӑ)'', , ultă ''(ултӑ)'', , ult ''(улт)'', / * 7 – şiççĕ ''(ҫиччӗ)'', , şiçĕ ''(ҫичӗ)'', , şiç ''(ҫич)'', * 8 – sakkăr ''(саккӑр)'', , sakăr ''(сакӑр)'', * 9 – tăhhăr ''(тӑххӑр)'', tăhăr ''(тӑхӑр)'' * 10 – wunnă ''(вуннӑ)'', wun ''(вун)'' The teens are formed by juxtaposing the word 'ten' and the corresponding single digit: * 11 – wun pĕr ''(вун пӗр)'' * 12 – wun ikkĕ ''(вун иккӗ)'', wun ikĕ ''(вун икӗ)'', wun ik ''(вун ик)'' * 13 – wun vişşĕ ''(вун виҫҫӗ)'', wun vişĕ ''(вун виҫӗ)'', wun viş ''(вун виҫ)'' * 14 – wun tăwattă ''(вун тӑваттӑ)'', wun tvată ''(вун тватӑ)'', wun tvat ''(вун тват)'' * 15 – wun pillĕk ''(вун пиллӗк)'', wun pilĕk ''(вун пилӗк)'', wun pil ''(вун пил)'' * 16 – wun ulttă ''(вун улттӑ)'', wun ultă ''(вун ултӑ)'', wun ult ''(вун улт)'' * 17 – wun şiççĕ ''(вун ҫиччӗ)'', wun şiçĕ ''(вун ҫичӗ)'', wun şiç ''(вун ҫич)'' * 18 – wun sakkăr ''(вун саккӑр)'', wun sakăr ''(вун сакӑр)'' * 19 – wun tăhhăr ''(вун тӑххӑр)'', wun tăhăr ''(вун тӑхӑр)'' The tens are formed in somewhat different ways: from 20 to 50, they exhibit suppletion; 60 and 70 have a suffix -мӑл together with stem changes; while 80 and 90 juxtapose the corresponding single digit and the word 'ten'. * 20 – şirĕm ''(ҫирӗм)'' * 30 – wătăr ''(вӑтӑр)'' * 40 – hĕrĕh ''(хӗрӗх)'' * 50 – allă ''(аллӑ)'', ală ''(алă)'', al ''(ал)'' * 60 – utmăl ''(утмӑл)'' * 70 – şitmĕl ''(ҫитмӗл)'' * 80 – sakăr wunnă ''(сакӑр вуннӑ)'', sakăr wun ''(сакӑр вун)'' * 90 – tăhăr wunnă ''(тӑхӑр вуннӑ)'', tăhăr wun ''(тӑхӑр вун)'' Further multiples of ten are: * 100 – şĕr ''(ҫĕр)'' * 1000 – pin ''(пин)'' * Example: - sakăr şĕr wătăr tvată pin te ik şĕr wătăr ulttă ''(сакӑр ҫӗр вӑтӑр тӑватӑ пин те ик ҫӗр вӑтӑр улттӑ)'', Ordinal numerals are formed with the suffix -mĕš (''-мӗш)'', e.g. pĕrremĕš ''(пӗррӗмӗш)'' 'first', ikkĕmĕš ''(иккӗмӗш)'' 'second'. There are also alternate ordinal numerals formed with the suffix -ӑм/-ĕм, which are used only for days, nights and years and only for the numbers from three to seven, e.g. wişĕm ''(виҫӗм)'' 'third', tvatăm ''(тватӑм)'', pilĕm ''(пилӗм)'', ultăm ''(ултӑм)'', şiçĕm ''(ҫичӗм)'', wunăm ''(вунӑм)''.Word formation

Some notable suffixes are: -ҫӑ for agent nouns, -лӑх for abstract and instrumental nouns, -ӑш, less commonly, for abstract nouns from certain adjectives, -у (after consonants) or -v (after vowels) for action nouns, -ла, -ал, -ар, and -н for denominal verbs. The valency changing suffixes and the gerunds were mentioned in the verbal morphology section above. Diminutives may be formed with multiple suffixes such as -ашка, -(к)ка, -лчӑ, -ак/ӑк, -ача.Sample text

1. Хӗвелӗн икӗ арӑм: Ирхи Шуҫӑмпа Каҫхи Шуҫӑм.Сатур, Улатимĕр. 2011. Çăлтăр çӳлти тӳпере / Звезда на небе. Шупашкар (a book on Chuvash myths, legends and customs)1. The Sun has two wives: Dawn and Afterglow (lit. "the Morning Glow" and "the Evening Glow").

2. Ир пулсан Хӗвел Ирхи Шуҫӑмран уйрӑлса каять

2. When it is morning, the Sun leaves Dawn

3. те яра кун тӑршшӗпе Каҫхи Шуҫӑм патнелле сулӑнать.

3. and during the whole day (he) moves towards Afterglow.

4. Ҫак икӗ мӑшӑрӗнчен унӑн ачасем:

4. From these two spouses of his, he has children:

5. Этем ятлӑ ывӑл тата Сывлӑм ятлӑ хӗр пур.

5. a son named Etem (Human) and a daughter named Syvlăm (Dew).

6. Этемпе Сывлӑм пӗррехинче Ҫӗр чӑмӑрӗ ҫинче тӗл пулнӑ та,

6. Etem and Syvlăm once met on the globe of the Earth,

7. пӗр-пӗрне юратса ҫемье чӑмӑртанӑ.

7. fell in love with each other and started a family.

8. Халь пурӑнакан этемсем ҫав мӑшӑрӑн тӑхӑмӗсем.

8. The humans who live today are the descendants of this couple.

See also

* Chuvash literature *Bulgar language

Bulgar (also known as Bulghar, Bolgar, or Bolghar) is the extinct Oghur Turkic language spoken by the Bulgars.

The name is derived from the Bulgars, a tribal association that established the Bulgar state known as Old Great Bulgaria in the mi ...

* Cyrillic script

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic languages, Slavic, Turkic languages, Turkic, Mongolic languages, Mongolic, Uralic languages, Uralic, C ...

* Oghur languages

The Oghuric, Onoguric or Oguric languages (also known as Bulgar, Bulgharic, Bolgar, Pre-Proto-Bulgaric or Lir-Turkic and r-Turkic) are a branch of the Turkic language family. The only extant member of the group is the Chuvash language. The firs ...

* Turkic Avar language

* Turkic languages

The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic langua ...

* Ivan Yakovlev

Notes

References

;Specific ;General * Agyagási, Klára. ''Chuvash Historical Phonetics: An Areal Linguistic Study. With an Appendix on the Role of Proto-Mari in the History of Chuvash Vocalism''. 1st ed. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh4zh9k. * * Dobrovolsky, Michael (1999)"The phonetics of Chuvash stress: implications for phonology"

Proceedings of the XIV International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, 539–542. Berkeley: University of California. * Johanson, Lars & Éva Agnes Csató, ed. (1998). ''The Turkic languages''. London: Routledge. * * * * Johanson, Lars (2007). Chuvash. ''Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics''. Oxford:

Elsevier

Elsevier ( ) is a Dutch academic publishing company specializing in scientific, technical, and medical content. Its products include journals such as ''The Lancet'', ''Cell (journal), Cell'', the ScienceDirect collection of electronic journals, ...

.

*

*

* Павлов, И. П. (2017). Современный чувашский язык. Чебоксары.

*

* Róna-Tas, András (2007). "Nutshell Chuvash" (PDF). ''Erasmus Mundus Intensive Program Turkic languages and cultures in Europe (TLCE)''. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2011.

*

Further reading

* Krueger, John R. "Remarks on the Chuvash Language: Past, Present and Future". In: ''Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Soviet National Languages: Their Past, Present and Future''. Edited by Isabelle T. Kreindler. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, 1985. pp. 265–274. *External links

Resources

Chuvash–Russian On-Line Dictionary

Chuvash English On-Line Dictionary

Chuvash People's Website

, also available in Chuvash, Esperanto and Russian (contains Chuvash literature)

''Nutshell Chuvash'', by András Róna-Tas

''Chuvash people and language'' by Éva Kincses Nagy, Istanbul Erasmus IP 1- 13. 2. 2007

''Chuvash manual online''

The Chuvash-Russian bilingual corpus

Translations of works by Alexander Pushkin into Chuvash

Chuvash literature blog

News and opinion articles

* [http://chuvash.org/content%2F3037-На%20чувашском%20конь%20еще%20не%20валялся....html Виталий Станьял: На чувашском конь еще не валялся...]

Виталий Станьял: Решение Совета Аксакалов ЧНК

* ttps://chuvash.org/news/17092.html Чӑваш чӗлхине Страсбургра хӳтӗлӗҫ

Тутарстанра чӗлхе пирки сӑмахларӗҫ

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20181026182747/https://www.idelreal.org/a/27902182.html Why don't Chuvash people speak Chuvash?

"As it is in the Chuvash Republic the Chuvash are not needed?!"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chuvash Language Agglutinative languages Chuvash people Languages of Russia Vowel-harmony languages Oghur languages Turkic languages