Church Of The East on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Church of the East ( ) or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church, the Chaldean Church or the Nestorian Church, is one of three major branches of Eastern

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 11 November 2018. It was in the aftermath of the slightly later

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved January 28, 2010. and 30 metropolitan provinces. According to John Foster, in the 9th century there were 25 metropolitans including those in China and India. The Chinese provinces were lost in the 11th century, and in the subsequent centuries other exterior provinces went into decline as well. However, in the 13th century, during the Mongol Empire, the church added two new metropolitan provinces in

File:Museum für Indische Kunst Dahlem Berlin Mai 2006 061.jpg,

File:Sutras on the Origin of Origins of Ta-ch‘in Luminous Religion (detail).jpg, Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the Nestorian Schism had led many of Nestorius' supporters to relocate to the Sasanian Empire, mainly around the theological School of Nisibis. The Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the Dyophisites, a measure encouraged by the Zoroastrian ruling class. The church became increasingly Dyophisite in doctrine over the next decades, furthering the divide between Roman and Persian Christianity. In 484 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, convened the Synod of Beth Lapat where he publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor,

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the Nestorian Schism had led many of Nestorius' supporters to relocate to the Sasanian Empire, mainly around the theological School of Nisibis. The Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the Dyophisites, a measure encouraged by the Zoroastrian ruling class. The church became increasingly Dyophisite in doctrine over the next decades, furthering the divide between Roman and Persian Christianity. In 484 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, convened the Synod of Beth Lapat where he publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor,  Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centres in Nisibis,

Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centres in Nisibis,

After the Sasanian Empire was conquered by Muslim Arabs in 644, the newly established

After the Sasanian Empire was conquered by Muslim Arabs in 644, the newly established

After the split with the Western World and synthesis with Nestorianism, the Church of the East expanded rapidly due to missionary works during the medieval period. During the period between 500 and 1400 the geographical horizon of the Church of the East extended well beyond its heartland in present-day northern

After the split with the Western World and synthesis with Nestorianism, the Church of the East expanded rapidly due to missionary works during the medieval period. During the period between 500 and 1400 the geographical horizon of the Church of the East extended well beyond its heartland in present-day northern

Christianity reached China by 635, and its relics can still be seen in Chinese cities such as

Christianity reached China by 635, and its relics can still be seen in Chinese cities such as

The Church of the East enjoyed a final period of expansion under the

The Church of the East enjoyed a final period of expansion under the

/ref> The Church of the East "lived on only in the mountains of

/ref> (for Gazarta, Hesna d'Kifa, Amid,

Fred Aprim, "Assyria and Assyrians Since the 2003 US Occupation of Iraq"

/ref> and its patriarchate remained hereditary until the death in 1975 of Shimun XXI Eshai. Accordingly, Joachim Jakob remarks that the original Patriarchate of the Church of the East (the Eliya line) entered into union with Rome and continues down to today in the form of the Chaldean atholicChurch, while the original Patriarchate of the Chaldean Catholic Church (the Shimun line) continues today in the Assyrian Church of the East.

Nicene Christianity

Nicene Christianity includes those Christian denominations that adhere to the teaching of the Nicene Creed, which was formulated at the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325 and amended at the First Council of Constantinople in AD 381. It encompas ...

that arose from the Christological controversies in the 5th century and the 6th century, alongside that of Miaphysitism

Miaphysitism () is the Christological doctrine that holds Jesus, the Incarnate Word, is fully divine and fully human, in one nature ('' physis'', ). It is a position held by the Oriental Orthodox Churches. It differs from the Dyophysitism of ...

(which came to be known as the Oriental Orthodox Churches

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 50 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches adhere to the Nicene Christian tradition. Oriental Orthodoxy is ...

) and Chalcedonian Christianity

Chalcedonian Christianity is the branches of Christianity that accept and uphold theological resolutions of the Council of Chalcedon, the fourth ecumenical council, held in AD 451. Chalcedonian Christianity accepts the Christological Definiti ...

(from which Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

and Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

would arise).

Having its origins in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

during the time of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power centered in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe ...

, the Church of the East developed its own unique form of Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

and liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

. During the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

, a series of schisms

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

gave rise to rival patriarchate

Patriarchate (, ; , ''patriarcheîon'') is an ecclesiological term in Christianity, referring to the office and jurisdiction of a patriarch.

According to Christian tradition, three patriarchates—Rome, Antioch, and Alexandria—were establi ...

s, sometimes two, sometimes three. In the latter half of the 20th century, the traditionalist patriarchate of the church underwent a split into two rival patriarchates, namely the Assyrian Church of the East

The Assyrian Church of the East (ACOE), sometimes called the Church of the East and officially known as the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, is an Eastern Christianity, Eastern Syriac Christianity, Syriac Christian denomin ...

and the Ancient Church of the East

The Ancient Church of the East (ACE) is an Eastern Christian denomination. It branched from the Assyrian Church of the East in 1964, under the leadership of Mar Toma Darmo (d. 1969). It is one of three Assyrian Churches that claim continuit ...

, which continue to follow the traditional theology and liturgy of the mother church. The Chaldean Catholic Church

The Chaldean Catholic Church is an Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic Catholic particular churches and liturgical rites, particular church (''sui iuris'') in full communion with the Holy See and the rest of the Catholic Church, and is ...

based in Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

and the Syro-Malabar Church

The Syro-Malabar Church, also known as the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, is an Eastern Catholic church based in Kerala, India. It is a '' sui iuris'' (autonomous) particular church in full communion with the Holy See and the worldwide Cathol ...

in India are two Eastern Catholic churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

which also claim the heritage of the Church of the East.

Background

The Church of the East organized itself initially in the year 410 as thenational church

A national church is a Christian church associated with a specific ethnic group or nation state. The idea was notably discussed during the 19th century, during the emergence of modern nationalism.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in a draft discussing ...

of the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranian peoples, Iranians"), was an List of monarchs of Iran, Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, th ...

through the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon. In 424, it declared itself independent of the state church of the Roman Empire

In the year before the First Council of Constantinople in 381, Nicene Christianity, Nicean Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Theodosius I, emperor of the East, Gratian, emperor of the West, and Gratian's junior co-r ...

, which it calls the 'Church of the West'. The Church of the East was headed by the Catholicos-Patriarch of the East seated originally in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, continuing a line that, according to its tradition, stretched back to Thomas the Apostle

Thomas the Apostle (; , meaning 'the Twin'), also known as Didymus ( 'twin'), was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus according to the New Testament. Thomas is commonly known as "doubting Thomas" because he initially doubted the resurrection of ...

in the first century. Its liturgical rite is the East Syrian rite that employs the Liturgy of Addai and Mari.

The Church of the East, which was part of the Great Church

The term "Great Church" () is used in the historiography of early Christianity to mean the period of about 180 to 313, between that of primitive Christianity and that of the legalization of the Christian religion in the Roman Empire, correspond ...

, shared communion with those in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

until the Council of Ephesus

The Council of Ephesus was a council of Christian bishops convened in Ephesus (near present-day Selçuk in Turkey) in AD 431 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius II. This third ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church th ...

condemned Nestorius

Nestorius of Constantinople (; ; ) was an early Christian prelate who served as Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to 11 July 431. A Christian theologian from the Catechetical School of Antioch, several of his teachings in the fi ...

in 431. The Church of the East refused to condemn Nestorius and was therefore called the "Nestorian Church" by those of the Roman Imperial church. More recently, the "Nestorian" appellation has been called "a lamentable misnomer", and theologically incorrect by scholars.

The Church of the East's declaration in 424 of the independence of its head, the Patriarch of the East, preceded by seven years the 431 Council of Ephesus, which condemned Nestorius and declared that Mary, mother of Jesus

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

, can be described as Theotokos

''Theotokos'' ( Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are or (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations are "Mother of God" or "God-beare ...

"Mother of God." Two of the generally accepted ecumenical councils

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote are ...

were held earlier: the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea ( ; ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

This ec ...

, in which a Persian bishop took part, in 325, and the First Council of Constantinople

The First Council of Constantinople (; ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) in AD 381 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I. This second ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the ...

in 381. The Church of the East accepted the teaching of these two councils but ignored the 431 Council and those that followed, seeing them as concerning only the patriarchates of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

(Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

), all of which were for it "''Western'' Christianity."

Theologically, the Church of the East adopted the dyophysite doctrine of Theodore of Mopsuestia

Theodore of Mopsuestia (Greek: Θεοδώρος, c. 350 – 428) was a Christian theologian, and Bishop of Mopsuestia (as Theodore II) from 392 to 428 AD. He is also known as Theodore of Antioch, from the place of his birth and presbyterate. ...

that emphasised the "distinctiveness" of the divine and the human natures of Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

; this doctrine was misleadingly labelled as 'Nestorian' by its theological opponents.

Continuing as a ''dhimmi

' ( ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligation under ''s ...

'' community under the Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate () is a title given for the reigns of first caliphs (lit. "successors") — Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali collectively — believed to Political aspects of Islam, represent the perfect Islam and governance who led the ...

after the Muslim conquest of Persia

As part of the early Muslim conquests, which were initiated by Muhammad in 622, the Rashidun Caliphate conquered the Sasanian Empire between 632 and 654. This event led to the decline of Zoroastrianism, which had been the official religion of ...

(633–654), the Church of the East played a major role in the history of Christianity in Asia

Christianity in Asia has its roots in the very inception of Christianity, which originated from the life and teachings of Jesus in 1st-century Roman Judea. Christianity then spread through the missionary work of his apostles, first in the Le ...

. Between the 9th and 14th centuries, it represented the world's largest Christian denomination

A Christian denomination is a distinct Religion, religious body within Christianity that comprises all Church (congregation), church congregations of the same kind, identifiable by traits such as a name, particular history, organization, leadersh ...

in terms of geographical extent, and in the Middle Ages was one of the three major Christian powerhouses of Eurasia alongside Latin Catholicism and Greek Orthodoxy. It established dioceses

In Ecclesiastical polity, church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided Roman province, prov ...

and communities stretching from the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

and today's Iraq and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, to India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, the Mongol kingdoms and Turkic tribes in Central Asia, and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

during the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

(7th–9th centuries). In the 13th and 14th centuries, the church experienced a final period of expansion under the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

, where influential Church of the East clergy sat in the Mongol court.

Even before the Church of the East underwent a rapid decline in its field of expansion in Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

in the 14th century, it had already lost ground in its home territory. The decline is indicated by the shrinking list of active dioceses from over sixty in the early 11th century to only seven in the 14th century. In the aftermath of the division of the Mongol Empire

The division of the Mongol Empire began after Möngke Khan died in 1259 in the Siege of Diaoyucheng, siege of Diaoyu Castle with no declared successor, precipitating infighting between members of the Tolui family line for the title of khagan th ...

, the rising Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

and Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic Mongol leaderships pushed out the Church of the East and its followers in Central Asia. The Chinese Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

overthrew the Mongols (1368) and ejected Christians and other foreign influences from China, and many Mongols in Central Asia converted to Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

. The Muslim Turco-Mongol leader Timur

Timur, also known as Tamerlane (1320s17/18 February 1405), was a Turco-Mongol conqueror who founded the Timurid Empire in and around modern-day Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia, becoming the first ruler of the Timurid dynasty. An undefeat ...

(1336–1405) nearly eradicated the remaining Christians in the Middle East. Nestorian Christianity remained largely confined to communities in Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia constitutes the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the regio ...

and the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of the Malabar Coast

The Malabar Coast () is the southwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. It generally refers to the West Coast of India, western coastline of India stretching from Konkan to Kanyakumari. Geographically, it comprises one of the wettest regio ...

in the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

.

The Church faced a major schism in 1552 following the consecration of monk Yohannan Sulaqa by Pope Julius III in opposition to the reigning Catholicos-Patriarch Shimun VII, leading to the formation of the Chaldean Catholic Church

The Chaldean Catholic Church is an Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic Catholic particular churches and liturgical rites, particular church (''sui iuris'') in full communion with the Holy See and the rest of the Catholic Church, and is ...

. Divisions occurred within the two factions, but by 1830 two unified patriarchates and distinct churches remained: the traditionalist Assyrian Church of the East

The Assyrian Church of the East (ACOE), sometimes called the Church of the East and officially known as the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, is an Eastern Christianity, Eastern Syriac Christianity, Syriac Christian denomin ...

and the Chaldean Catholic Church. The Ancient Church of the East

The Ancient Church of the East (ACE) is an Eastern Christian denomination. It branched from the Assyrian Church of the East in 1964, under the leadership of Mar Toma Darmo (d. 1969). It is one of three Assyrian Churches that claim continuit ...

split from the traditionalist patriarchate in 1968. In 2017, the Chaldean Catholic Church had approximately 628,405 members and the Assyrian Church of the East had 323,300 to 380,000, while the Ancient Church of the East had 100,000.

Description as Nestorian

Nestorianism

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinary, doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian t ...

is a Christological

In Christianity, Christology is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Different denominations have different opinions on questions such as whether Jesus was human, divine, or both, and as a messiah what his role would be in the freeing of ...

doctrine that emphasises the distinction between the human and divine natures of Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

. It was attributed to Nestorius

Nestorius of Constantinople (; ; ) was an early Christian prelate who served as Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to 11 July 431. A Christian theologian from the Catechetical School of Antioch, several of his teachings in the fi ...

, Patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox Church. The ecumenical patriarch is regarded as ...

from 428 to 431, whose doctrine represented the culmination of a philosophical current developed by scholars at the School of Antioch

The Catechetical School of Antioch was one of the two major Christian centers of the study of biblical exegesis and theology during Late Antiquity; the other was the Catechetical School of Alexandria, School of Alexandria. This group was known by ...

, most notably Nestorius's mentor Theodore of Mopsuestia

Theodore of Mopsuestia (Greek: Θεοδώρος, c. 350 – 428) was a Christian theologian, and Bishop of Mopsuestia (as Theodore II) from 392 to 428 AD. He is also known as Theodore of Antioch, from the place of his birth and presbyterate. ...

, and stirred controversy when Nestorius publicly challenged the use of the title ''Theotokos

''Theotokos'' ( Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are or (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations are "Mother of God" or "God-beare ...

'' (literally, "Bearer of God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

") for Mary, mother of Jesus

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

, suggesting that the title denied Christ's full humanity. He argued that Jesus had two loosely joined natures, the divine Logos

''Logos'' (, ; ) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric, as well as religion (notably Logos (Christianity), Christianity); among its connotations is that of a rationality, rational form of discourse that relies on inducti ...

and the human Jesus, and proposed '' Christotokos'' (literally, "Bearer of the Christ") as a more suitable alternative title. His statements drew criticism from other prominent churchmen, particularly from Cyril

Cyril (also Cyrillus or Cyryl) is a masculine given name. It is derived from the Greek language, Greek name (''Kýrillos''), meaning 'lordly, masterful', which in turn derives from Greek (''kýrios'') 'lord'. There are various variant forms of t ...

, Patriarch of Alexandria

The Patriarch of Alexandria is the archbishop of Alexandria, Egypt. Historically, this office has included the designation "pope" (etymologically "Father", like "Abbot").

The Alexandrian episcopate was revered as one of the three major epi ...

, who had a leading part in the Council of Ephesus

The Council of Ephesus was a council of Christian bishops convened in Ephesus (near present-day Selçuk in Turkey) in AD 431 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius II. This third ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church th ...

of 431, which condemned Nestorius for heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

and deposed him as Patriarch.

After 431, state authorities in the Roman Empire suppressed Nestorianism, a reason for Christians under Persian rule to favour it and so allay suspicion that their loyalty lay with the hostile Christian-ruled empire."Nestorius"''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 11 November 2018. It was in the aftermath of the slightly later

Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; ) was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bithynia (modern-day Kadıköy, Istanbul, Turkey) from 8 Oct ...

(451) that the Church of the East formulated a distinctive theology. The first such formulation was adopted at the Synod of Beth Lapat in 484. This was developed further in the early seventh century, when in an at first successful war against the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

the Sasanid Persian Empire incorporated broad territories populated by West Syrians, many of whom were supporters of the Miaphysite

Miaphysitism () is the Christological doctrine that holds Jesus, the Incarnate Word, is fully divine and fully human, in one nature (''physis'', ). It is a position held by the Oriental Orthodox Churches. It differs from the Dyophysitism of the ...

theology of Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 50 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches adhere to the Nicene Christian tradition. Oriental Orthodoxy is ...

which its opponents term "Monophysitism" ( Eutychianism), the theological view most opposed to Nestorianism. They received support from Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; and ''Khosrau''), commonly known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian King of Kings (Shahanshah) of Iran, ruling from 590 ...

, influenced by his wife Shirin. Shirin was a member of the Church of East, but later joined the miaphysite church of Antioch.

Drawing inspiration from Theodore of Mopsuestia

Theodore of Mopsuestia (Greek: Θεοδώρος, c. 350 – 428) was a Christian theologian, and Bishop of Mopsuestia (as Theodore II) from 392 to 428 AD. He is also known as Theodore of Antioch, from the place of his birth and presbyterate. ...

, Babai the Great (551−628) expounded, especially in his ''Book of Union'', what became the normative Christology

In Christianity, Christology is a branch of Christian theology, theology that concerns Jesus. Different denominations have different opinions on questions such as whether Jesus was human, divine, or both, and as a messiah what his role would b ...

of the Church of the East. He affirmed that the two (a Syriac term, plural of ''qnoma'', not corresponding precisely to Greek φύσις or οὐσία or ὑπόστασις) of Christ are unmixed but eternally united in his single (from Greek πρόσωπον ''prosopon

Prosopon is a theological term used in Christian theology as designation for the concept of a God in Christianity, divine personhood#Christianity, person. The term has a particular significance in Christian triadology (study of the Trinity), and a ...

'' "mask, character, person"). As happened also with the Greek terms φύσις (''physis

Physis (; ; pl. physeis, φύσεις) is a Greek philosophical, theological, and scientific term, usually translated into English—according to its Latin translation "natura"—as "nature". The term originated in ancient Greek philosophy, a ...

'') and ὐπόστασις ('' hypostasis''), these Syriac words were sometimes taken to mean something other than what was intended; in particular "two " was interpreted as "two individuals". Previously, the Church of the East accepted a certain fluidity of expressions, always within a dyophysite

Dyophysitism (; from Greek δύο ''dyo'', "two" and φύσις ''physis'', "nature") is the Christological position that Jesus Christ is in two distinct, inseparable natures: divine and human. It is accepted by the majority of Christian denomin ...

theology, but with Babai's assembly of 612, which canonically sanctioned the "two in Christ" formula, a final christological distinction was created between the Church of the East and the "western" Chalcedonian churches.

The justice of imputing Nestorianism to Nestorius

Nestorius of Constantinople (; ; ) was an early Christian prelate who served as Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to 11 July 431. A Christian theologian from the Catechetical School of Antioch, several of his teachings in the fi ...

, whom the Church of the East venerated as a saint, is disputed. David Wilmshurst states that for centuries "the word 'Nestorian' was used both as a term of abuse by those who disapproved of the traditional East Syrian theology, as a term of pride by many of its defenders ..and as a neutral and convenient descriptive term by others. Nowadays it is generally felt that the term carries a stigma". Sebastian P. Brock says: "The association between the Church of the East and Nestorius is of a very tenuous nature, and to continue to call that church 'Nestorian' is, from a historical point of view, totally misleading and incorrect – quite apart from being highly offensive and a breach of ecumenical good manners".

Apart from its religious meaning, the word "Nestorian" has also been used in an ethnic sense, as shown by the phrase "Catholic Nestorians".

In his 1996 article, "The 'Nestorian' Church: a lamentable misnomer", published in the '' Bulletin of the John Rylands Library'', Sebastian Brock, a Fellow of the British Academy

Fellowship of the British Academy (post-nominal letters FBA) is an award granted by the British Academy to leading academics for their distinction in the humanities and social sciences. The categories are:

# Fellows – scholars resident in t ...

, lamented the fact that "the term 'Nestorian Church' has become the standard designation for the ancient oriental church which in the past called itself 'The Church of the East', but which today prefers a fuller title 'The Assyrian Church of the East'. Such a designation is not only discourteous to modern members of this venerable church, but also − as this paper aims to show − both inappropriate and misleading".

Organisation and structure

At the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410, the Church of the East was declared to have at its head the bishop of the Persian capital Seleucia-Ctesiphon, who in the acts of the council was referred to as the Grand or Major Metropolitan, and who soon afterward was called the Catholicos of the East. Later, the title ofPatriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Roman Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and ...

was used.

The Church of the East had, like other churches, an ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

clergy in the three traditional orders of bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

, priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

(or presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros'', which means elder or senior, although many in Christian antiquity understood ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning as overseer ...

), and deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions.

Major Christian denominations, such as the Cathol ...

. Also like other churches, it had an episcopal polity

An episcopal polity is a hierarchical form of church governance in which the chief local authorities are called bishops. The word "bishop" here is derived via the British Latin and Vulgar Latin term ''*ebiscopus''/''*biscopus'', . It is the ...

: organisation by diocese

In Ecclesiastical polity, church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided Roman province, prov ...

s, each headed by a bishop and made up of several individual parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

communities overseen by priests. Dioceses were organised into provinces

A province is an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outside Italy. The term ''provi ...

under the authority of a metropolitan bishop

In Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan (alternative obsolete form: metropolite), is held by the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a Metropolis (reli ...

. The office of metropolitan bishop was an important one, coming with additional duties and powers; canonically, only metropolitans could consecrate

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects ( ...

a patriarch. The Patriarch also has the charge of the Province of the Patriarch.

For most of its history the church had six or so Interior Provinces. In 410, these were listed in the hierarchical order of: Seleucia-Ctesiphon (central Iraq), Beth Lapat (western Iran), Nisibis

Nusaybin () is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Mardin Province, Turkey. Its area is 1,079 km2, and its population is 115,586 (2022). The city is populated by Kurds of different tribal affiliation.

Nusaybin is separated ...

(on the border between Turkey and Iraq), Prat de Maishan (Basra, southern Iraq), Arbela (Erbil, North Iraq), and Karka de Beth Slokh (Kirkuk, northeastern Iraq). In addition it had an increasing number of Exterior Provinces further afield within the Sasanian Empire and soon also beyond the empire's borders. By the 10th century, the church had between 20"Nestorian"''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved January 28, 2010. and 30 metropolitan provinces. According to John Foster, in the 9th century there were 25 metropolitans including those in China and India. The Chinese provinces were lost in the 11th century, and in the subsequent centuries other exterior provinces went into decline as well. However, in the 13th century, during the Mongol Empire, the church added two new metropolitan provinces in

North China

North China () is a list of regions of China, geographical region of the People's Republic of China, consisting of five province-level divisions of China, provincial-level administrative divisions, namely the direct-administered municipalities ...

, one being Tangut, the other Katai and Ong.

Scriptures

ThePeshitta

The Peshitta ( ''or'' ') is the standard Syriac edition of the Bible for Syriac Christian churches and traditions that follow the liturgies of the Syriac Rites.

The Peshitta is originally and traditionally written in the Classical Syriac d ...

, in some cases lightly revised and with missing books added, is the standard Syriac Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition: the Syriac Orthodox Church

The Syriac Orthodox Church (), also informally known as the Jacobite Church, is an Oriental Orthodox Christian denomination, denomination that originates from the Church of Antioch. The church currently has around 4-5 million followers. The ch ...

, the Syrian Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East

The Assyrian Church of the East (ACOE), sometimes called the Church of the East and officially known as the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, is an Eastern Christianity, Eastern Syriac Christianity, Syriac Christian denomin ...

, the Ancient Church of the East

The Ancient Church of the East (ACE) is an Eastern Christian denomination. It branched from the Assyrian Church of the East in 1964, under the leadership of Mar Toma Darmo (d. 1969). It is one of three Assyrian Churches that claim continuit ...

, the Chaldean Catholic Church

The Chaldean Catholic Church is an Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic Catholic particular churches and liturgical rites, particular church (''sui iuris'') in full communion with the Holy See and the rest of the Catholic Church, and is ...

, the Maronites

Maronites (; ) are a Syriac Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant (particularly Lebanon) whose members belong to the Maronite Church. The largest concentration has traditionally resided near Mount ...

, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

The Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (MOSC) also known as the Indian Orthodox Church (IOC) or simply as the Malankara Church, is an Autocephaly, autocephalous Oriental Orthodox Churches, Oriental Orthodox church headquartered in #Catholicate ...

, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

The Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

of the Peshitta

The Peshitta ( ''or'' ') is the standard Syriac edition of the Bible for Syriac Christian churches and traditions that follow the liturgies of the Syriac Rites.

The Peshitta is originally and traditionally written in the Classical Syriac d ...

was translated from Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, although the date and circumstances of this are not entirely clear. The translators may have been Syriac-speaking Jews or early Jewish converts to Christianity. The translation may have been done separately for different texts, and the whole work was probably done by the second century. Most of the deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament are found in the Syriac, and the Wisdom of Sirach is held to have been translated from the Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

and not from the Septuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

.

The New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

of the Peshitta

The Peshitta ( ''or'' ') is the standard Syriac edition of the Bible for Syriac Christian churches and traditions that follow the liturgies of the Syriac Rites.

The Peshitta is originally and traditionally written in the Classical Syriac d ...

, which originally excluded certain disputed books ( Second Epistle of Peter, Second Epistle of John

The Second Epistle of John is a book of the New Testament attributed to John the Evangelist, traditionally thought to be the author of the other two epistles of John, and the Gospel of John (though this is disputed). Most modern scholars beli ...

, Third Epistle of John

The Third Epistle of John is the third-to-last book of the New Testament and the Christian Bible as a whole, and attributed to John the Evangelist, traditionally thought to be the author of the Gospel of John and the other two epistles of John ...

, Epistle of Jude

The Epistle of Jude is the penultimate book of the New Testament and of the Christianity, Christian Bible. The Epistle of Jude claims authorship by Jude the Apostle, Jude, identified as a servant of Jesus and brother of James (and possibly Jesu ...

, Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

), had become the standard by the early 5th century.

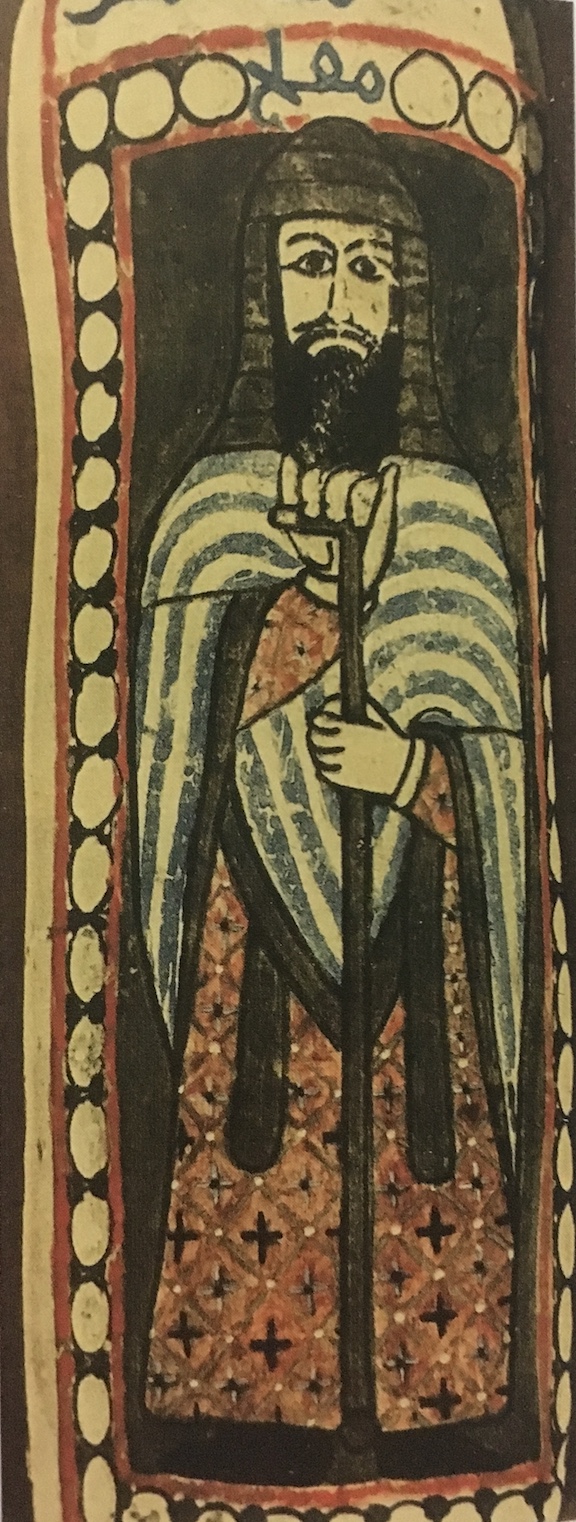

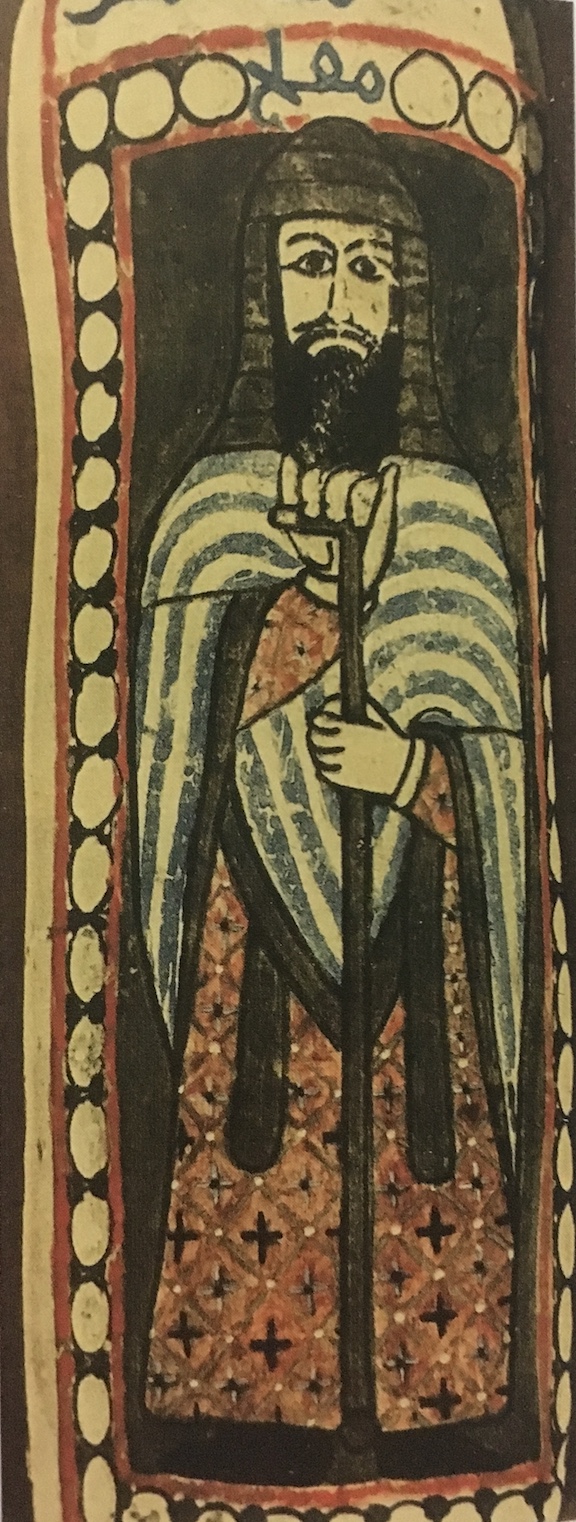

Iconography

It was often said in the 19th century that the Church of the East was opposed to religious images of any kind. The cult of the image was never as strong in the Syriac Churches as it was in the Byzantine Church, but they were indeed present in the tradition of the Church of the East. Opposition to religious images eventually became the norm due to the rise of Islam in the region, which forbade any type of depictions of Saints and biblical prophets. As such, the Church was forced to get rid of icons. There is both literary and archaeological evidence for the presence of images in the church. Writing in 1248 fromSamarkand

Samarkand ( ; Uzbek language, Uzbek and Tajik language, Tajik: Самарқанд / Samarqand, ) is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central As ...

, an Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

n official records visiting a local church and seeing an image of Christ and the Magi. John of Cora (), Latin bishop of Sultaniya in Persia, writing about 1330 of the East Syrians in Khanbaliq

Khanbaliq (; , ''Qaɣan balɣasu'') or Dadu of Yuan (; , ''Dayidu'') was the Historical capitals of China, winter capital of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty in what is now Beijing, the capital of China today. It was located at the center of modern ...

says that they had 'very beautiful and orderly churches with crosses and images in honour of God and of the saints'. Apart from the references, a painting of a Christian figure discovered by Aurel Stein

Sir Marc Aurel Stein,

(; 26 November 1862 – 26 October 1943) was a Hungarian-born British archaeologist, primarily known for his explorations and archaeological discoveries in Central Asia. He was also a professor at Indian universities.

...

at the Library Cave of the Mogao Caves in 1908 is probably a representation of Jesus Christ.

An illustrated 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta

The Peshitta ( ''or'' ') is the standard Syriac edition of the Bible for Syriac Christian churches and traditions that follow the liturgies of the Syriac Rites.

The Peshitta is originally and traditionally written in the Classical Syriac d ...

Gospel book written in Estrangela from northern Mesopotamia or Tur Abdin

Tur Abdin (; ; ; or ) is a hilly region situated in southeast Turkey, including the eastern half of the Mardin Province, and Şırnak Province west of the Tigris, on the Syria–Turkey border, border with Syria and famed since Late Antiquity for ...

, currently in the State Library of Berlin, proves that in the 13th century the Church of the East was not yet aniconic. The Nestorian Evangelion preserved in the contains an illustration depicting Jesus Christ in the circle of a ringed cross surrounded by four angels. Three Syriac manuscripts from early 19th century or earlierthey were published in a compilation titled '' The Book of Protection'' by Hermann Gollancz in 1912contain some illustrations of no great artistic worth that show that use of images continued.

A life-size male stucco figure discovered in a late-6th-century Nestorian church in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, beneath which were found the remains of an earlier church, also shows that the Church of the East used figurative representations.

Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is the Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Its name originates from the palm bran ...

procession of Nestorian clergy in a 7th- or 8th-century wall painting from the Nestorian church at Karakhoja, Chinese Turkestan.

File:Mogao Christian painting (original version).jpg, Mogao Christian painting, a late-9th-century silk painting preserved in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

.

File:Nestorian Peshitta Gospel – Feast of the Discovery of the Cross.jpg, Feast of the Discovery of the Cross, from a 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela, preserved in the SBB.

File:Nestorian Peshitta Gospel – Announcement of Jesus’ Resurrection.jpg, An angel

An angel is a spiritual (without a physical body), heavenly, or supernatural being, usually humanoid with bird-like wings, often depicted as a messenger or intermediary between God (the transcendent) and humanity (the profane) in variou ...

announces the resurrection of Christ

The resurrection of Jesus () is Christian belief that God raised Jesus from the dead on the third day after his crucifixion, starting—or restoring—his exalted life as Christ and Lord. According to the New Testament writing, Jesus w ...

to Mary and Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene (sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine) was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to crucifixion of Jesus, his cr ...

, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

File:Nestorian Peshitta Gospel – Pentecost.jpg, The Twelve Apostles

In Christian theology and ecclesiology, the apostles, particularly the Twelve Apostles (also known as the Twelve Disciples or simply the Twelve), were the primary disciples of Jesus according to the New Testament. During the life and minist ...

are gathered around Peter at Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christianity, Christian holiday which takes place on the 49th day (50th day when inclusive counting is used) after Easter Day, Easter. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spiri ...

, from the Nestorian Peshitta Gospel.

File:Cruz de la Iglesia del Oriente («nestoriana»).jpg, Illustration from the Nestorian Evangelion, a Syriac gospel manuscript preserved in the BnF.

File:Four Evangelists, Church of the East.jpg, Portraits of the Four Evangelists

In Christian tradition, the Four Evangelists are Matthew the Apostle, Matthew, Mark the Evangelist, Mark, Luke the Evangelist, Luke, and John the Evangelist, John, the authors attributed with the creation of the four canonical Gospel accounts ...

, from a gospel lectionary according to the Nestorian use. Mosul

Mosul ( ; , , ; ; ; ) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. It is the second largest city in Iraq overall after the capital Baghdad. Situated on the banks of Tigris, the city encloses the ruins of the ...

, Timurid Empire

The Timurid Empire was a late medieval, culturally Persianate, Turco-Mongol empire that dominated Greater Iran in the early 15th century, comprising modern-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, much of Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and parts of co ...

, 1499.

File:Entry of Jesus Christ into Jerusalem, with a Female Figure in T'ang Costume, Chotscho, Sinkiang.jpg, Drawing of a rider ( Entry into Jerusalem), a lost wall painting from the Nestorian church at Karakhoja, 9th century.

File:Nestorian Christian Statuette.jpg, Nestorian Christian statuette probably from Imperial China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, a bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a person who has attained, or is striving towards, '' bodhi'' ('awakening', 'enlightenment') or Buddhahood. Often, the term specifically refers to a person who forgoes or delays personal nirvana or ''bodhi'' in ...

-like figurine seated on a cross, probably Mongol dynasty (1271–1368).

File:Piatto con decorazione di castello assediato, arg, samirechye, da bolshoe-anikovskaya, IX-X sec su orig del l'VIII sec.JPG, Anikova Plate, showing the Siege of Jericho. It was probably made in and for a Sogdia

Sogdia () or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also a province of the Achaemen ...

n Nestorian Christian community located in Semirechye. 9th–10th century.

File:Dish with biblical scenes, Church of the East, line drawing.jpg, The Grigorovskoye Plate: Paten

A paten or diskos is a small plate used for the celebration of the Eucharist (as in a mass). It is generally used during the liturgy itself, while the reserved sacrament are stored in the tabernacle in a ciborium.

Western usage

In many Wes ...

with biblical scenes in medallions, counterclockwise from bottom left: women

A woman is an adult female human. Before adulthood, a female child or adolescent is referred to as a girl.

Typically, women are of the female sex and inherit a pair of X chromosomes, one from each parent, and women with functional u ...

at the empty tomb

The empty tomb is the Christian tradition that the tomb of Jesus was found empty after his crucifixion. The canonical gospels each describe the visit of women to Jesus' tomb. Although Jesus' body had been laid out in the tomb after crucifixi ...

, the crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

, and the Ascension. Semirechye, 9th–10th century.

Luoyang

Luoyang ( zh, s=洛阳, t=洛陽, p=Luòyáng) is a city located in the confluence area of the Luo River and the Yellow River in the west of Henan province, China. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zheng ...

. 9th century.

File:Sutras on the Origin of Origins of Ta-ch‘in Luminous Religion (detail-L).jpg, Detail of the rubbing of the Nestorian pillar of Luoyang, discovered in Luoyang. 9th century.

Early history

Although the East Syriac Christian community traced their history to the 1st century AD, the Church of the East first achieved official state recognition from the Sasanian Empire in the 4th century with the accession ofYazdegerd I

Yazdegerd I (also spelled Yazdgerd and Yazdgird; ) was the Sasanian King of Kings () of Iran from 399 to 420. A son of Shapur III (), he succeeded his brother Bahram IV () after the latter's assassination.

Yazdegerd I's largely-uneventful reig ...

(reigned 399–420) to the throne of the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranian peoples, Iranians"), was an List of monarchs of Iran, Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, th ...

. The policies of the Sasanian Empire, which encouraged syncretic forms of Christianity, greatly influenced the Church of the East.

The early Church had branches that took inspiration from Neo-Platonism, other Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

ern religions like Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

, and other forms of Christianity.

In 410, the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, held at the Sasanian capital, allowed the church's leading bishops to elect a formal Catholicos (leader). Catholicos Isaac

Isaac ( ; ; ; ; ; ) is one of the three patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith. Isaac first appears in the Torah, in wh ...

was required both to lead the Assyrian Christian community and to answer on its behalf to the Sasanian emperor.

Under pressure from the Sasanian Emperor, the Church of the East sought to increasingly distance itself from the Pentarchy

Pentarchy (, ) was a model of Church organization formulated in the laws of Emperor Justinian I () of the Roman Empire. In this model, the Christian Church is governed by the heads (patriarchs) of the five major episcopal sees of the Roman Em ...

(at the time being known as the church of the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

). Therefore, in 424, the bishops of the Sasanian Empire met in council under the leadership of Catholicos Dadishoʿ (421–456) and determined that they would not, henceforth, refer disciplinary or theological problems to any external power, and especially not to any bishop or church council in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

.

Thus, the Mesopotamian churches did not send representatives to the various church councils attended by representatives of the "Western Church

Western Christianity is one of two subdivisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholic C ...

". Accordingly, the leaders of the Church of the East did not feel bound by any decisions of what came to be regarded as Roman Imperial Councils. Despite this, the Creed and Canons of the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea ( ; ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

This ec ...

of 325, affirming the full divinity of Christ, were formally accepted at the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410. The church's understanding of the term hypostasis differs from the definition of the term offered at the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; ) was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bithynia (modern-day Kadıköy, Istanbul, Turkey) from 8 Oct ...

of 451. For this reason, the Assyrian Church has never approved the Chalcedonian definition

The Chalcedonian Definition (also called the Chalcedonian Creed or the Definition of Chalcedon) is the declaration of the dyophysitism of Hypostatic union, Christ's nature, adopted at the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451. Chalcedon was an Early cen ...

.

The theological controversy that followed the Council of Ephesus

The Council of Ephesus was a council of Christian bishops convened in Ephesus (near present-day Selçuk in Turkey) in AD 431 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius II. This third ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church th ...

in 431 proved a turning point in the Christian Church's history. The Council condemned as heretical the Christology of Nestorius

Nestorius of Constantinople (; ; ) was an early Christian prelate who served as Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to 11 July 431. A Christian theologian from the Catechetical School of Antioch, several of his teachings in the fi ...

, whose reluctance to accord the Virgin Mary the title ''Theotokos

''Theotokos'' ( Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are or (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations are "Mother of God" or "God-beare ...

'' "God-bearer, Mother of God" was taken as evidence that he believed two separate persons (as opposed to two united natures) to be present within Christ.

The Sasanian Emperor, hostile to the Byzantines, saw the opportunity to ensure the loyalty of his Christian subjects and lent support to the Nestorian Schism. The Emperor took steps to cement the primacy of the Nestorian party within the Assyrian Church of the East, granting its members his protection, and executing the pro-Roman Catholicos Babowai in 484, replacing him with the Nestorian Bishop of Nisibis

Nusaybin () is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Mardin Province, Turkey. Its area is 1,079 km2, and its population is 115,586 (2022). The city is populated by Kurds of different tribal affiliation.

Nusaybin is separated ...

, Barsauma. The Catholicos-Patriarch Babai (497–503) confirmed the association of the Assyrian Church with Nestorianism.

Parthian and Sasanian periods

Christians were already forming communities inMesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

as early as the 1st century under the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power centered in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe ...

. In 266, the area was annexed by the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranian peoples, Iranians"), was an List of monarchs of Iran, Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, th ...

(becoming the province of Asōristān

Asoristan ( ''Asōristān'', ''Āsūristān'') was the name of the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian province of Assyria and Babylonia from 226 to 637.

Name

The Parthian language, Parthian name ''Asōristān'' (; also spelled ''Asoristan'', ''Asurista ...

), and there were significant Christian communities in Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia constitutes the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the regio ...

, Elam

Elam () was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of modern-day southern Iraq. The modern name ''Elam'' stems fr ...

, and Fars. The Church of the East traced its origins ultimately to the evangelical activity of Thaddeus of Edessa

According to Eastern Christian tradition, Addai of Edessa ( Syriac: ܡܪܝ ܐܕܝ, Mar Addai or Mor Aday sometimes Latinized Addeus) or Thaddeus of Edessa was one of the seventy disciples of Jesus.

Life

Based on various Eastern Christian ...

, Mari and Thomas the Apostle

Thomas the Apostle (; , meaning 'the Twin'), also known as Didymus ( 'twin'), was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus according to the New Testament. Thomas is commonly known as "doubting Thomas" because he initially doubted the resurrection of ...

. Leadership and structure remained disorganised until 315 when Papa bar Aggai (310–329), bishop of Seleucia

Seleucia (; ), also known as or or Seleucia ad Tigrim, was a major Mesopotamian city, located on the west bank of the Tigris River within the present-day Baghdad Governorate in Iraq. It was founded around 305 BC by Seleucus I Nicator as th ...

-Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon ( ; , ''Tyspwn'' or ''Tysfwn''; ; , ; Thomas A. Carlson et al., “Ctesiphon — ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified July 28, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/58.) was an ancient city in modern Iraq, on the eastern ba ...

, imposed the primacy of his see over the other Mesopotamian and Persian bishoprics which were grouped together under the Catholicate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon; Papa took the title of Catholicos, or universal leader. This position received an additional title in 410, becoming Catholicos and Patriarch of the East.

These early Christian communities in Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars were reinforced in the 4th and 5th centuries by large-scale deportations of Christians from the eastern Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. However, the Persian Church faced several severe persecutions, notably during the reign of Shapur II

Shapur II ( , 309–379), also known as Shapur the Great, was the tenth King of Kings (List of monarchs of the Sasanian Empire, Shahanshah) of Sasanian Iran. He took the title at birth and held it until his death at age 70, making him the List ...

(339–379), from the Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, Zoroaster ( ). Among the wo ...

majority who accused it of Roman leanings. Shapur II attempted to dismantle the catholicate's structure and put to death some of the clergy including the catholicoi Simeon bar Sabba'e (341), Shahdost (342), and Barba'shmin Barbaʿshmin, also called Barbasceminus, was a fourth-century bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, primate of the Church of the East, and martyr. He succeeded Shahdost as bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 343, during the great persecution of Shapur II, an ...

(346). Afterward, the office of Catholicos lay vacant nearly 20 years (346–363). In 363, under the terms of a peace treaty, Nisibis was ceded to the Persians, causing Ephrem the Syrian

Ephrem the Syrian (; ), also known as Ephraem the Deacon, Ephrem of Edessa or Aprem of Nisibis, (Syriac: ܡܪܝ ܐܦܪܝܡ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ — ''Mâr Aphrêm Sûryâyâ)'' was a prominent Christian theology, Christian theologian and Christian literat ...

, accompanied by a number of teachers, to leave the School of Nisibis for Edessa

Edessa (; ) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, in what is now Urfa or Şanlıurfa, Turkey. It was founded during the Hellenistic period by Macedonian general and self proclaimed king Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Sel ...

still in Roman territory. The church grew considerably during the Sasanian period, but the pressure of persecution led the Catholicos, Dadisho I, in 424 to convene the Council of Markabta of the Arabs and declare the Catholicate independent from "the western Fathers".

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the Nestorian Schism had led many of Nestorius' supporters to relocate to the Sasanian Empire, mainly around the theological School of Nisibis. The Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the Dyophisites, a measure encouraged by the Zoroastrian ruling class. The church became increasingly Dyophisite in doctrine over the next decades, furthering the divide between Roman and Persian Christianity. In 484 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, convened the Synod of Beth Lapat where he publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor,

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the Nestorian Schism had led many of Nestorius' supporters to relocate to the Sasanian Empire, mainly around the theological School of Nisibis. The Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the Dyophisites, a measure encouraged by the Zoroastrian ruling class. The church became increasingly Dyophisite in doctrine over the next decades, furthering the divide between Roman and Persian Christianity. In 484 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, convened the Synod of Beth Lapat where he publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor, Theodore of Mopsuestia

Theodore of Mopsuestia (Greek: Θεοδώρος, c. 350 – 428) was a Christian theologian, and Bishop of Mopsuestia (as Theodore II) from 392 to 428 AD. He is also known as Theodore of Antioch, from the place of his birth and presbyterate. ...

, as a spiritual authority. In 489, when the School of Edessa

The School of Edessa () was a Christian theology, Christian theological school of great importance to the Syriac language, Syriac-speaking world. It had been founded as long ago as the 2nd century by the kings of the Abgarid dynasty, Abgar dynasty. ...

in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

was closed by Byzantine Emperor Zeno

Zeno may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the given name

* Zeno (surname)

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 B ...

for its Nestorian teachings, the school relocated to its original home of Nisibis, becoming again the School of Nisibis, leading to a wave of Nestorian immigration into the Sasanian Empire. The Patriarch of the East Mar Babai I

Babai, also Babaeus, was Catholicos of Seleucia-Ctesiphon and Patriarch of the Church of the East from 497 to 503. Under his leadership, the Church in Sasanian Empire (Persia) became increasingly aligned with the Nestorianism, Nestorian movement ...

(497–502) reiterated and expanded upon his predecessors' esteem for Theodore, solidifying the church's adoption of Dyophisitism.

Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centres in Nisibis,

Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centres in Nisibis, Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon ( ; , ''Tyspwn'' or ''Tysfwn''; ; , ; Thomas A. Carlson et al., “Ctesiphon — ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified July 28, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/58.) was an ancient city in modern Iraq, on the eastern ba ...

, and Gundeshapur

Gundeshapur (, ''Weh-Andiōk-Ŝābuhr''; New Persian: , ''Gondēshāpūr'') was the intellectual centre of the Sassanid Empire and the home of the Academy of Gundeshapur, founded by Sassanid Emperor Shapur I. Gundeshapur was home to a teaching hos ...

, and several metropolitan see

Metropolitan may refer to:

Areas and governance (secular and ecclesiastical)

* Metropolitan archdiocese, the jurisdiction of a metropolitan archbishop

** Metropolitan bishop or archbishop, leader of an ecclesiastical "mother see"

* Metropolitan ...

s, the Church of the East began to branch out beyond the Sasanian Empire. However, through the 6th century the church was frequently beset with internal strife and persecution from the Zoroastrians. The infighting led to a schism, which lasted from 521 until around 539, when the issues were resolved. However, immediately afterward Byzantine-Persian conflict led to a renewed persecution of the church by the Sasanian emperor Khosrau I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; ), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ("the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 531 to 579. He was the son and successor of Kavad I ().

Inheriting a rei ...

; this ended in 545. The church survived these trials under the guidance of Patriarch Aba I, who had converted to Christianity from Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zoroaster, Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, ...

.

By the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 6th, the area occupied by the Church of the East included "all the countries to the east and those immediately to the west of the Euphrates", including the Sasanian Empire, the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

, with minor presence in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

, Socotra