China–France relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

China–France relations, also known as Franco-Chinese relations or Sino-French relations, are the

A journal of the first French embassy to China, 1698-1700

/ref> Numerous French Jesuits were active in China during the 17th and 18th centuries:

French Catholic missionaries were active in China; they were funded by appeals in French churches for money. The Holy Childhood Association (L'Oeuvre de la Sainte Enfance) was a Catholic charity founded in 1843 to rescue Chinese children from infanticide. It was a target of Chinese anti-Christian protests notably in the

French Catholic missionaries were active in China; they were funded by appeals in French churches for money. The Holy Childhood Association (L'Oeuvre de la Sainte Enfance) was a Catholic charity founded in 1843 to rescue Chinese children from infanticide. It was a target of Chinese anti-Christian protests notably in the

In 1900, France was a major participant in the

In 1900, France was a major participant in the

File:Hôtel de Montesquiou, 20 rue Monsieur, Paris 7e.jpg, Embassy of China in Paris

File:Consulat-général-Chine-Saint-Denis.JPG, Consulate-General of China in Saint-Denis, Réunion

online

* Bonin, Hubert. French banks in Hong Kong (1860s-1950s): Challengers to British banks?" ''Groupement de Recherches Economiques et Sociales'' No. 2007-15. 2007. * Bunkar, Bhagwan Sahai. "Sino-French Diplomatic Relations: 1964-81" ''China Report'' (Feb 1984) 20#1 pp 41–52 * Césari, Laurent, & Denis Varaschin. ''Les Relations Franco-Chinoises au Vingtieme Siecle et Leurs Antecedents'' Sino-French relations in the 20th century and their antecedents"(2003) 290 pp. * Chesneaux, Jean, Marianne Bastid, and Marie-Claire Bergere. ''China from the Opium Wars to the 1911 Revolution'' (1976

Online

* Cabestan, Jean-Pierre. "Relations between France and China: towards a Paris-Beijing axis?." ''China: an international journal'' 4.2 (2006): 327–340

online

* Christiansen, Thomas, Emil Kirchner, and Uwe Wissenbach. ''The European Union and China'' (Macmillan International Higher Education, 2019). * Clyde, Paul Hibbert, and Burton F. Beers. ''The Far East: A History of Western Impacts and Eastern Responses, 1830-1975'' (1975)

online

* Cotterell, Arthur. ''Western Power in Asia: Its Slow Rise and Swift Fall, 1415 - 1999'' (2009) popular history

excerpt

* Eastman, Lloyd E. ''Throne and Mandarins: China's Search for a Policy during the Sino-French controversy, 1880-1885'' (Harvard University Press, 1967) * Gundry, Richard S. ed. ''China and Her Neighbours: France in Indo-China, Russia and China, India and Thibet'' (1893), magazine article

online

* Hughes, Alex. ''France/China: intercultural imaginings'' (2007

online

* Mancall, Mark. ''China at the center: 300 years of foreign policy'' (1984). passim. * Martin, Garret. "Playing the China Card? Revisiting France's Recognition of Communist China, 1963–1964." ''Journal of Cold War Studies'' 10.1 (2008): 52–80. * Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''International Relations of the Chinese Empire: The Period of Conflict: 1834-1860''. (1910

online

** Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''International Relations of the Chinese Empire: The Period of Submission: 1861–1893''. (1918

online

** Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''International Relations of the Chinese Empire: The Period of Subjection: 1894-1911'' (1918

online

* Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''The Trade and Administration of the Chinese Empire'' (1908

online

* Pieragastini, Steven. "State and Smuggling in Modern China: The Case of Guangzhouwan/Zhanjiang." ''Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review'' 7.1 (2018): 118–152

online

* Skocpol, Theda. "France, Russia, China: A structural analysis of social revolutions." ''Comparative Studies in Society and History'' 18.2 (1976): 175–210. * Upton, Emory. ''The Armies of Asia and Europe: Embracing Official Reports on the Armies of Japan, China, India, Persia, Italy, Russia, Austria, Germany, France, and England'' (1878)

Online

* Wellons, Patricia. "Sino‐French relations: Historical alliance vs. economic reality." ''Pacific Review'' 7.3 (1994): 341–348. * Weske, Simone. "The role of France and Germany in EU-China relations." ''CAP Working Paper'' (2007

online

* Young, Ernest. ''Ecclesiastical Colony: China's Catholic Church and the French Religious Protectorate, '' (Oxford UP, 2013)

interstate relations

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such a ...

between China and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

(Kingdom or later).

Note that the meaning of both "China" and "France" as entities has changed throughout history; this article will discuss what was commonly considered 'France' and 'China' at the time of the relationships in question. There have been many political, cultural and economic relationships between the two countries since the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. Rabban Bar Sauma

Rabban Bar Ṣawma ( Syriac language: , ; 1220January 1294), also known as Rabban Ṣawma or Rabban ÇaumaMantran, p. 298 (), was a Turkic Chinese ( Uyghur or possibly Ongud) monk turned diplomat of the "Nestorian" Church of the East in China. ...

from China visited France and met with King Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (french: Philippe le Bel), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre as Philip I from 1 ...

. William of Rubruck

William of Rubruck ( nl, Willem van Rubroeck, la, Gulielmus de Rubruquis; ) was a Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer.

He is best known for his travels to various parts of the Middle East and Central Asia in the 13th century, including the ...

encountered the French silversmith Guillaume Bouchier in the Mongol city of Karakorum

Karakorum ( Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, ''Kharkhorum''; Mongolian Script:, ''Qaraqorum''; ) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan dynasty in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in t ...

.

Present-day relations are marked by both countries's respective regional powers

In international relations, since the late 20thcentury, the term "regional power" has been used for a sovereign state that exercises significant power within a given geographical region.Joachim Betz, Ian Taylor"The Rise of (New) Regional Pow ...

stature (in the EU for France and Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

for China), as well as their shared status as G20 economies, permanent members of the UN Security Council

The permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (also known as the Permanent Five, Big Five, or P5) are the five sovereign states to whom the UN Charter of 1945 grants a permanent seat on the UN Security Council: China, France, R ...

, and internationally recognized nuclear-weapon states. Key differences include the question of Democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

and Human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

.

Today, France adheres to the One China

The term One China may refer to one of the following:

* The One China principle is the position held by the People's Republic of China (PRC) that there is only one sovereign state under the name China, with the PRC serving as the sole legit ...

policy, where France recognized the People's Republic of China as the sole legitimate government of "China", as opposed to the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

, where it maintains unofficial relations.

The Chinese-French relationship was raised to the level of “global strategic partnership” in 2004. Strategic dialogue (last session from 23 to 24 January 2019), which began in 2001, deals with all areas of cooperation and aims to strengthen dialogue global issues, such as reform of global economic governance, climate change and regional crises.

Country comparison

History

17th and 18th centuries

In 1698-1700 CE first French embassy to China took place via sea route.Translated by S. Bannister, 1859A journal of the first French embassy to China, 1698-1700

/ref> Numerous French Jesuits were active in China during the 17th and 18th centuries:

Nicolas Trigault

Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628) was a Jesuit, and a missionary in China. He was also known by his latinised name Nicolaus Trigautius or Trigaultius, and his Chinese name Jin Nige ().

Life and work

Born in Douai (then part of the County of Fland ...

(1577–1629), Alexander de Rhodes

Alexandre de Rhodes (15 March 1593 – 5 November 1660) was an Avignonese Jesuit missionary and lexicographer who had a lasting impact on Christianity in Vietnam. He wrote the ''Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum'', the first trilingu ...

(1591–1660, active in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making it ...

), Jean-Baptiste Régis (1663–1738), Jean Denis Attiret

Jean Denis Attiret (, 31 July 1702 – 8 December 1768) was a French Jesuit painter and missionary to Qing China.

Early life

Attiret was born in Dole, France. He studied art in Rome and made himself a name as a portrait painter. While ...

(1702–1768), Michel Benoist

Michel Benoist (, 8 October 1715 in Dijon, France – 23 October 1774 in Beijing, China) was a Jesuit scientist who served for thirty years in the court of the Qianlong Emperor (1735 - 1796) during the Qing Dynasty, known for his architectura ...

(1715–1774), Joseph-Marie Amiot (1718–1793).

French Jesuits pressured the French king to send them to China with the aims of counterbalancing the influence of Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in Europe. The Jesuits sent by Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ve ...

were: Jean de Fontaney (1643–1710), Joachim Bouvet

Joachim Bouvet (, courtesy name: 明远) (July 18, 1656, in Le Mans – June 28, 1730, in Peking) was a French Jesuit who worked in China, and the leading member of the Figurist movement.

China

Bouvet came to China in 1687, as one of six Jesui ...

(1656-1730), Jean-François Gerbillon

Jean-François Gerbillon (4 June 1654, Verdun, France – 27 March 1707, Peking, China) was a French missionary who worked in China.

He entered the Society of Jesus, 5 Oct, 1670, and after completing the usual course of study taught grammar and ...

(1654–1707), Louis Le Comte Louis le Comte (1655–1728), also Louis-Daniel Lecomte, was a French Jesuit who participated in the 1687 French Jesuit mission to China under Jean de Fontaney. He arrived in China on 7 February 1688.

He returned to France in 1691 as Procurator ...

(1655–1728) and Claude de Visdelou (1656–1737). Returning to France, they noticed the similarity between Louis XIV of France and the Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 1654– 20 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, born Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1661 to ...

of China. Both were said to be servants of God, and to control their respective areas: France being the strongest country of Europe, and China being the strongest power in East Asia. Other biographical factors lead commentators to proclaim that Louis XIV and the Kangxi Emperor were protected by the same angel. (In childhood, they overcame the same illness; both reigned for a long time, with many conquests.)

Under Louis XIV's reign, the work of these French researchers sent by the King had a notable influence on Chinese sciences, but continued to be mere intellectual games, and not tools to improve the power of man over nature. Conversely, Chinese culture and style became fashionable in France, exemplified by the Chinoiserie

(, ; loanword from French ''chinoiserie'', from ''chinois'', "Chinese"; ) is the European interpretation and imitation of Chinese and other East Asian artistic traditions, especially in the decorative arts, garden design, architecture, literatu ...

fashion, and Louis XIV had the Trianon de Porcelaine built in Chinese style in 1670. France became the European center for Chinese porcelains, silks and lacquers and European imitations of these goods.

At the same time, the first ever known Chinese people came to France. Michel Sin

Michael Alphonsus Shen Fu-Tsung, SJ, also known as Michel Sin, Michel Chin-fo-tsoung, Shen Fo-tsung, or Shen Fuzong (, 1691),

arrived in Versaille in 1684 before continuing on to England. More notable was Arcadio Huang

Arcadio Huang (, born in Xinghua, modern Putian, in Fujian, 15 November 1679, died on 1 October 1716 in Paris)Mungello, p.125 was a Chinese Christian convert, brought to Paris by the Missions étrangères. He took a pioneering role in the teachi ...

, who crossed France in 1702, spent some time in Rome (as a result of the Chinese Rites controversy

The Chinese Rites controversy () was a dispute among Roman Catholic missionaries over the religiosity of Confucianism and Chinese rituals during the 17th and 18th centuries. The debate discussed whether Chinese ritual practices of honoring fa ...

), and returned to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

in 1704, where he was the "Chinese interpreter of the King" before he died in 1716. He started the first ever Chinese-French dictionary, and a Chinese grammar to help French and European researchers to understand and study Chinese, but died before finishing his work.

Paris-based geographers processed reports and cartographic material supplied by mostly French Jesuit teams traveling across the Qing Empire, and published a number of high-quality works, the most important of which was '' Description de la Chine et de la Tartarie Chinoise'' edited by Jean-Baptiste Du Halde (1736), with maps by Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville

Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville (; born in Paris 11 July 169728 January 1782) was a French geographer and cartographer who greatly improved the standards of map-making. D'Anville became cartographer to the king, who purchased his cartographic ...

.

In the 18th century, the French Jesuit priest Michel Benoist

Michel Benoist (, 8 October 1715 in Dijon, France – 23 October 1774 in Beijing, China) was a Jesuit scientist who served for thirty years in the court of the Qianlong Emperor (1735 - 1796) during the Qing Dynasty, known for his architectura ...

, together with Giuseppe Castiglione, helped the Qianlong Emperor

The Qianlong Emperor (25 September 17117 February 1799), also known by his temple name Emperor Gaozong of Qing, born Hongli, was the fifth Emperor of the Qing dynasty and the fourth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1735 ...

build a European-style area in the Old Summer Palace

The Old Summer Palace, also known as Yuanmingyuan () or Yuanmingyuan Park, originally called the Imperial Gardens (), and sometimes called the Winter Palace, was a complex of palaces and gardens in present-day Haidian District, Beijing, China. ...

(often associated with European-style palaces built of stone), to satisfy his taste for exotic buildings and objects. Jean Denis Attiret

Jean Denis Attiret (, 31 July 1702 – 8 December 1768) was a French Jesuit painter and missionary to Qing China.

Early life

Attiret was born in Dole, France. He studied art in Rome and made himself a name as a portrait painter. While ...

became a painter to the Qianlong Emperor. Joseph-Marie Amiot (1718–1793) also won the confidence of the emperor and spent the remainder of his life in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

. He was official translator of Western languages for the emperor, and the spiritual leader of the French mission in Peking.

19th century

Tianjin Massacre

The Tientsin Massacre (), was an attack on Christian missionaries and converts in the late 19th century during the late Qing dynasty. 60 people died in attacks on French Catholic priests and nuns. There was intense belligerence from French diploma ...

of 1870. Rioting sparked by false rumors of the killing of babies led to the death of a French consul and provoked a diplomatic crisis.

Relations between Qing China and France deteriorated in the European rush for markets and as European opinion of China deteriorated, the once admired empire would become the subject of unequal treaties and colonisation. In 1844, China and France concluded its first modern treaty, the Treaty of Whampoa, which demanded for France the same privileges extended to Britain. In 1860, the Summer Palace

The Summer Palace () is a vast ensemble of lakes, gardens and palaces in Beijing. It was an imperial garden in the Qing dynasty. Inside includes Longevity Hill () Kunming Lake and Seventeen Hole Bridge. It covers an expanse of , three-quarte ...

was sacked by Anglo-French troops and many precious artifacts found their way into French museums following the sack.

Second Opium war

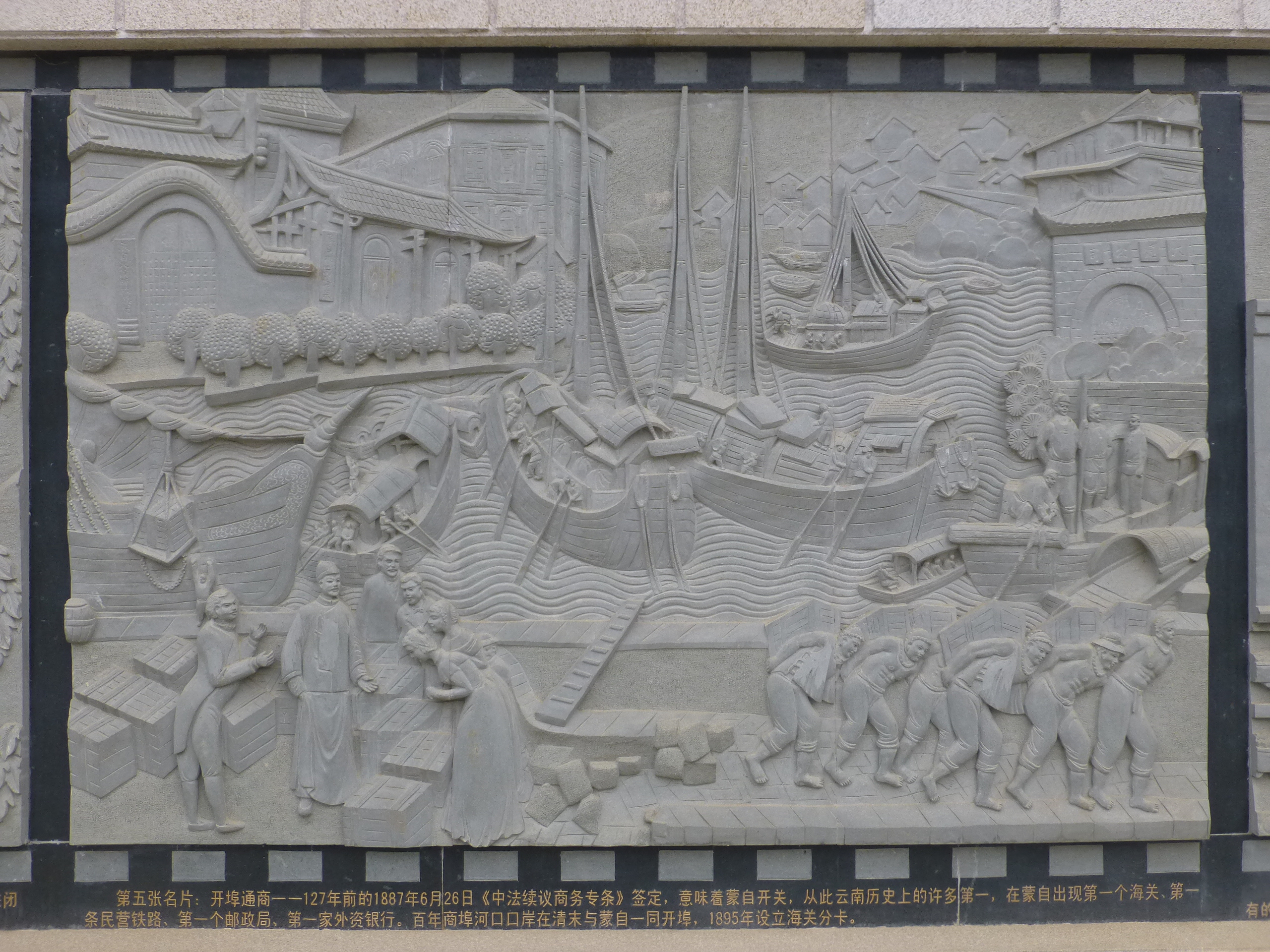

Sino-French war, 1884-1885

For centuries China had claimed the Indo-China territory to its south as a tributary state, but France began a series of invasions, turning French Indochina into its own colony. France and China clashed over control of Annam. The result was a conflict in 1884–85. The undeclared war was militarily a stalemate, but it recognize that France had control of Annam and Indochina was no longer a tributary of China. The main political result was that the war strengthened the control ofEmpress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi ( ; mnc, Tsysi taiheo; formerly Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Empress Dowager T'zu-hsi; 29 November 1835 – 15 November 1908), of the Manchu people, Manchu Nara (clan)#Yehe Nara, Yehe Nara clan, was a Chinese nob ...

over the Chinese government, giving her the chance to block modernization programs needed by the Chinese military. The war was unpopular in France and it brought down the government of Prime Minister Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry (; 5 April 183217 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885. He ...

. Historian Lloyd Eastman concluded in 1967:

:The Chinese, although fettered by outmoded techniques and shortages of supplies, had fought the French to a stalemate. China lost, it is true, its claim to sovereignty over Vietnam, and that country remained under French dominance until 1954. But the French had been denied an indemnity; railroad construction had been averted; and imperial control of the southern boundaries of the rich natural resources lying within those boundaries had not been broken. In short, China was not much changed by the war.

In 1897, France seized Kwangchow Wan, (Guangzhouwan

The Leased Territory of Guangzhouwan, officially the , was a territory on the coast of Zhanjiang in China leased to France and administered by French Indochina. The capital of the territory was Fort-Bayard, present-day Zhanjiang.

The Japan ...

) as a treaty port, and took its own concession in the treaty port of Shanghai. Kwangchow Wan was leased by China to France for 99 years (or until 1997, as the British did in Hong Kong's New Territories), according to the Treaty of 12 April 1898, on 27 May as ''Territoire de Kouang-Tchéou-Wan'', to counter the growing commercial power of British Hong Kong and was effectively placed under the authority of the French Resident Superior in Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain '' Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, inclu ...

(itself under the Governor General of French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

, also in Hanoi); the French Resident was represented locally by Administrators.Olson 1991: 349

Railway construction

20th century

Eight-Nation Alliance

The Eight-Nation Alliance was a multinational military coalition that invaded northern China in 1900 with the stated aim of relieving the foreign legations in Beijing, then besieged by the popular Boxer militia, who were determined to remove f ...

which invaded China to put down the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, b ...

. In the early 20th century Chinese students began to come to France. Li Shizeng

Li Shizeng (; 29 May 1881 – 30 September 1973), born Li Yuying, was an educator, promoter of anarchist doctrines, political activist, and member of the Chinese Nationalist Party in early Republican China.

After coming to Paris in 1902, Li to ...

, Zhang Renjie

Zhang Renjie (Chang Jen-chieh 19 September 1877 − 3 September 1950), born Zhang Jingjiang, was a political figure and financial entrepreneur in the Republic of China. He studied and worked in France in the early 1900s, where he became an early C ...

, Wu Zhihui, and Cai Yuanpei

Cai Yuanpei (; 1868–1940) was a Chinese philosopher and politician who was an influential figure in the history of Chinese modern education. He made contributions to education reform with his own education ideology. He was the president of Pek ...

formed an anarchist group which became the basis for the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement. Zhang started a gallery which imported Chinese art, and the dealer C.T. Loo

Ching Tsai Loo, commonly known as C. T. Loo (; 1February 1880August15, 1957), was a controversial art dealer of Chinese origin who maintained galleries in Paris and New York and supplied important pieces for collectors and American museums by i ...

developed his Paris gallery into an international center.

In 1905-1907 Japan made overtures on China to enlarge its sphere of influence to include Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its c ...

. Japan was trying to obtain French loans and also avoid the Open Door Policy

The Open Door Policy () is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy wa ...

. Paris provided loans on condition that Japan respect the Open Door and not violate China's territorial integrity. In the French-Japanese Entente of 1907, Paris secured Japan's recognition of the special interests France possessed in “the regions of the Chinese Empire adjacent to the territories” where they had “the rights of sovereignty, protection or occupation,” which meant the French colonial possessions in southeast Asia as well as the French spheres of influence in three provinces in southern China—Yunnan, Guangxi, and Guangdong. In return, the French recognized Japan's spheres of influence in Korea, South Manchuria, and Inner Mongolia.

The French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 194 ...

recognized the establishment of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

and established diplomatic relations on 7October 1913. After the outbreak of war, the French government recruited Chinese workers to work in French factories. Li Shizeng and his friends organized the Société Franco-Chinoise d'Education (華法教育會 HuaFa jiaoyuhui) in 1916. Many worker-students who came to France after the war became high level members of the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

. These included Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 January 1976. Zhou served under Chairman Ma ...

and Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. Aft ...

. The Institut Franco Chinoise de Lyon (1921—1951) promoted cultural exchanges.

During World War II, Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exil ...

and China fought as allied powers against the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

of Germany, Italy and Japan. After the invasion of France in 1940, although the newly formed Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the Fascism, fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of ...

was an ally of Germany, it continued to recognize the Kuomintang government of Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

—which had to flee to Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Cou ...

in the Chinese interior after the fall of Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

in 1937—rather than the Japanese-sponsored Reorganized National Government of China

The Wang Jingwei regime or the Wang Ching-wei regime is the common name of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China ( zh , t = 中華民國國民政府 , p = Zhōnghuá Mínguó Guómín Zhèngfǔ ), the government of the pup ...

under Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

. French diplomats in China remained accredited to the government in Chongqing.

On 18 August 1945 in Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Cou ...

, while the Japanese were still occupying Kwangchow Wan following the surrender, a French diplomat from the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

and Kuo Chang Wu, Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China, signed the ''Convention between the Provisional Government of the French Republic and the National Government of China for the retrocession of the Leased Territory of Kouang-Tchéou-Wan''. Almost immediately after the last Japanese occupation troops had left the territory in late September, representatives of the French and the Chinese governments went to Fort-Bayard to proceed to the transfer of authority; the French flag was lowered for the last time on 20 November 1945.

During the Cold War era, 1947–1991, France first established diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China in 1964. France played a minor role in the Korean War. In the 1950s, communist insurgents based in China repeatedly invaded and attacked French facilities in Indochina. After a major defeat by the Vietnamese communists at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, France pulled out and turned North Vietnam over to the Communists. By exiting Southeast Asia, France avoided confrontations with China. However, the Cultural Revolution sparked violence against French diplomats in China, and relationships cooled. The powerful French Communist Party generally supported the Soviet Union in the Sino-Soviet split and China had therefore a very weak base of support inside France, apart from some militant students.

Cold War relations

After theChinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

(19271950) and the establishment of the new communist-led People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, sli ...

(PRC) on 1 October 1949, the French Fourth Republic

The French Fourth Republic (french: Quatrième république française) was the republican government of France from 27 October 1946 to 4 October 1958, governed by the fourth republican constitution. It was in many ways a revival of the Third Re ...

government did not recognize the PRC. Instead, France maintained relations with the Republic of China on Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northe ...

. However, by 1964 France and the PRC had re-established ambassadorial level diplomatic relations. This was precipitated by Charles de Gaulle's official recognition of the PRC. Before the Chinese Civil War, Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. Aft ...

had completed his studies in Paris prior to ascending to power in China.

Post-Cold War

This state of relations would not last, however. During the 1990s, France and the PRC repeatedly clashed as a result of the PRC'sOne China Policy

The term One China may refer to one of the following:

* The One China principle is the position held by the People's Republic of China (PRC) that there is only one sovereign state under the name China, with the PRC serving as the sole legit ...

. France sold weapons to Taiwan, angering the Beijing government. This resulted in the temporary closure of the French Consulate-General in Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong ...

. France eventually agreed to prohibit local companies from selling arms to Taiwan, and diplomatic relations resumed in 1994. Since then, the two countries have exchanged a number of state visits. Today, Sino-French relations are primarily economic. Bilateral trade reached new high levels in 2000. Cultural ties between the two countries are less well represented, though France is making an effort to improve this disparity. France has expanded its research facilities dealing with Chinese history, culture, and current affairs. Organizations associated with the International Liaison Department of the Chinese Communist Party

The International Department of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (ID; ), better known as the International Liaison Department (ILD), is an agency under the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in charge of establi ...

maintain links with French parliamentarians.

In 2018 China made accusations against France after a French naval vessel transited the Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a -wide strait separating the island of Taiwan and continental Asia. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

The Taiwan Strait is itself ...

.

2008 rifts

In 2008, Sino-French relations took a downturn in the wake of the 2008 Summer Olympics torch relay. As torchbearers passed through Paris, activists fighting for Tibetan independence and human rights repeatedly attempted to disrupt, hinder or halt the procession. The Chinese government hinted that Sino-French friendship could be affected while Chinese protesters organized boycotts of the French-owned retail chainCarrefour

Carrefour () is a French multinational retail and wholesaling corporation headquartered in Massy, France. The eighth-largest retailer in the world by revenue, it operates a chain of hypermarkets, groceries stores and convenience stores, wh ...

in major Chinese cities including Kunming

Kunming (; ), also known as Yunnan-Fu, is the capital and largest city of Yunnan province, China. It is the political, economic, communications and cultural centre of the province as well as the seat of the provincial government. The headqua ...

, Hefei

Hefei (; ) is the capital and largest city of Anhui Province, People's Republic of China. A prefecture-level city, it is the political, economic, and cultural center of Anhui. Its population was 9,369,881 as of the 2020 census and its built-up ( ...

and Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city a ...

. Hundreds of people also joined anti-French rallies in those cities and Beijing. Both governments attempted to calm relations after the demonstrations. French President Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul Stéphane Sarközy de Nagy-Bocsa (; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012.

Born in Paris, he is of Hungarian, Greek Jewish, and French origin. Mayor of Neuilly-sur-Sei ...

wrote a letter of support and sympathy to Jin Jing, a Chinese athlete who had carried the Olympic torch. Chinese leader Hu Jintao

Hu Jintao (born 21 December 1942) is a Chinese politician who served as the 16–17th general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 2002 to 2012, the 6th president of the People's Republic of China (PRC) from 2003 to 2013, an ...

subsequently sent a special envoy to France to help strengthen relations.

However, relations again soured after President Sarkozy met the Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current Dal ...

in Poland in 2009. Chinese Premier

The premier of the State Council of the People's Republic of China, commonly called the premier of China and sometimes also referred to as the prime minister, is the head of government of China and leader of the State Council. The premier is ...

Wen Jiabao

Wen Jiabao (born 15 September 1942) is a retired Chinese politician who served as the Premier of the State Council from 2003 to 2013. In his capacity as head of government, Wen was regarded as the leading figure behind China's economic polic ...

omitted France in his tour of Europe in response, his assistant foreign minister saying of the rift "The one who tied the knot should be the one who unties it." French Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin

Jean-Pierre Raffarin (; born 3 August 1948) is a French politician who served as Prime Minister of France from 6 May 2002 to 31 May 2005.

He resigned after France's rejection of the referendum on the European Union draft constitution. Howeve ...

was quoted in ''Le Monde

''Le Monde'' (; ) is a French daily afternoon newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average circulation of 323,039 copies per issue in 2009, about 40,000 of which were sold abroad. It has had its own website si ...

'' as saying that France had no intention of "encourag ngTibetan separatism".

Human rights

Hong Kong

In June 2020, France openly opposed theHong Kong national security law

The Hong Kong national security law, officially the Law of the People's Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, is a piece of national security legislation concerning Hong Kong. I ...

.

Xinjiang

In March 2021, European Union leaders imposed sanctions on various Chinese Communist Party officials. China responded by sanctioning various French politicians such as Raphael GlucksmannTaiwan

In 2021, French senator Alain Richard announced a visit to Taiwan. The Chinese embassy initially sent him letters requesting him to stop. After he refused to reconsider his trip, the Chinese embassy began Tweeting aggressive insults and threats against him and various other pro-Taiwan lawmakers and experts. The Chinese ambassador was summoned to underscore the unacceptable nature of the threats.2019 trade deals

At a time when China–U.S. economic relations were deeply troubled, with atrade war

A trade war is an economic conflict often resulting from extreme protectionism in which states raise or create tariffs or other trade barriers against each other in response to trade barriers created by the other party. If tariffs are the exclu ...

underway, French President Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France since 2017 French presidential election, 2017. ''Ex officio'', he is also one of the two Co-Princes of Andorra. Prior to his presidency, M ...

and Chinese paramount leader

Paramount leader () is an informal term for the most important political figure in the People's Republic of China (PRC). The paramount leader typically controls the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People's Liberation Army (PLA), often hol ...

Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping ( ; ; ; born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has served as the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), and thus as the paramount leader of China, ...

signed a series of large-scale trade agreements in late March 2019 which covered many sectors over a period of years. The centerpiece was a €30 billion purchase of airplanes from Airbus

Airbus SE (; ; ; ) is a European multinational aerospace corporation. Airbus designs, manufactures and sells civil and military aerospace products worldwide and manufactures aircraft throughout the world. The company has three divisions: '' ...

. It came at a time when the leading American firm, Boeing

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and ...

, saw its entire fleet of new 737 MAX passenger planes grounded worldwide. Going well beyond aviation, the new trade agreement covered French exports of chicken, a French-built offshore wind farm in China, and a Franco-Chinese cooperation fund, as well as billions of Euros of co-financing between BNP Paribas

BNP Paribas is a French international banking group, founded in 2000 from the merger between Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP, "National Bank of Paris") and Paribas, formerly known as the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas. The full name of the gro ...

and the Bank of China

The Bank of China (BOC; ) is a Chinese majority state-owned commercial bank headquartered in Beijing and the fourth largest bank in the world.

The Bank of China was founded in 1912 by the Republican government as China's central bank, repl ...

. Other plans included billions of euros to be spent on modernizing Chinese factories, as well as new ship building.

Public opinion

Survey published in 2020 by the Pew Research Center found that 70% of French had an unfavourable view of China.Tourism

In 2018, around 2.1 million Chinese tourists visited France. A 2014 poll indicated that Chinese tourists considered France to be the most welcoming nation in Europe.Resident diplomatic missions

* China has an embassy inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

, consulates-general in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

, Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fran ...

, Saint-Denis and Strasbourg, and a consulate in Papeete

Papeete ( Tahitian: ''Papeete'', pronounced ) is the capital city of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of the French Republic in the Pacific Ocean. The commune of Papeete is located on the island of Tahiti, in the administrative subdivisi ...

.

* France has an embassy in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

and consulates-general in Chengdu

Chengdu (, ; simplified Chinese: 成都; pinyin: ''Chéngdū''; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: ), alternatively romanized as Chengtu, is a sub-provincial city which serves as the capital of the Chinese provin ...

, Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong ...

, Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

, Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

, Shenyang and Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city a ...

.

Education

French international schools in Mainland China include: *Lycée Français International Charles de Gaulle de Pékin

The Lycée Français International Charles de Gaulle de Pékin (LFIPékin; ) is a French international school in Chaoyang District, Beijing. It has primary, junior high school (''collège'') and sixth-form/senior high school (''lycée'') levels. ...

(Beijing)

* Lycée Français de Shanghai

* Wuhan French International School

Wuhan French International School (french: Ecole Française Internationale de Wuhan, EFIW; ) is a French international school in Wuhan, China. It is adjacent to Jianghan University, in Hanyang District. It directly teaches ''toute petite section' ...

* École Française Internationale de Canton (Guangzhou)

Shekou International School in Shenzhen has a section for primary school students using the French system.

There is also a French international school in Hong Kong: French International School of Hong Kong

French International School "Victor Segalen" of Hong Kong (FIS in English, french: Lycée français international Victor-Segalen; LFI; ) is a French international school in Hong Kong. It is the only accredited French school in Hong Kong (lin ...

.

There is also a bilingual Chinese-French school aimed at Chinese children, École expérimentale franco-chinoise de Pékin (北京中法实验学校), which is converted from the former Wenquan No. 2 Middle School, in Haidian District, Beijing.

See also

* China–European Union relations *History of Chinese foreign policy

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), has full diplomatic relations with 178 out of the other 193 United Nations member states, Cook Islands, Niue and the State of Palestine. Since 2019, China has had the most diplomatic mis ...

* Foreign relations of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), has full diplomatic relations with 178 out of the other 193 United Nations member states, Cook Islands, Niue and the State of Palestine. Since 2019, China has had the most diplomatic m ...

** Foreign relations of imperial China : ''For the later history after 1800 see History of foreign relations of China.''

The foreign relations of Imperial China from the Qin dynasty until the Qing dynasty encompassed many situations as the fortunes of dynasties rose and fell. Chinese c ...

* China Policy Institute

The China Policy Institute (CPI) is a research centre in the School of Politics and International Relations, University of Nottingham, that is focused on various aspects of contemporary China. It has a remit to disseminate policy relevant insights ...

* Historical Museum of French-Chinese Friendship

Montargis () is a commune in the Loiret department, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

Montargis is the seventh most populous commune in the Loiret, after Orléans and its suburbs. It is near a large forest, and contains light industry and farming, ...

References

References

*Further reading

* Becker, Bert. "France and the Gulf of Tonkin region: Shipping markets and political interventions in south China in the 1890s." ''Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review'' 4.2 (2015): 560–600online

* Bonin, Hubert. French banks in Hong Kong (1860s-1950s): Challengers to British banks?" ''Groupement de Recherches Economiques et Sociales'' No. 2007-15. 2007. * Bunkar, Bhagwan Sahai. "Sino-French Diplomatic Relations: 1964-81" ''China Report'' (Feb 1984) 20#1 pp 41–52 * Césari, Laurent, & Denis Varaschin. ''Les Relations Franco-Chinoises au Vingtieme Siecle et Leurs Antecedents'' Sino-French relations in the 20th century and their antecedents"(2003) 290 pp. * Chesneaux, Jean, Marianne Bastid, and Marie-Claire Bergere. ''China from the Opium Wars to the 1911 Revolution'' (1976

Online

* Cabestan, Jean-Pierre. "Relations between France and China: towards a Paris-Beijing axis?." ''China: an international journal'' 4.2 (2006): 327–340

online

* Christiansen, Thomas, Emil Kirchner, and Uwe Wissenbach. ''The European Union and China'' (Macmillan International Higher Education, 2019). * Clyde, Paul Hibbert, and Burton F. Beers. ''The Far East: A History of Western Impacts and Eastern Responses, 1830-1975'' (1975)

online

* Cotterell, Arthur. ''Western Power in Asia: Its Slow Rise and Swift Fall, 1415 - 1999'' (2009) popular history

excerpt

* Eastman, Lloyd E. ''Throne and Mandarins: China's Search for a Policy during the Sino-French controversy, 1880-1885'' (Harvard University Press, 1967) * Gundry, Richard S. ed. ''China and Her Neighbours: France in Indo-China, Russia and China, India and Thibet'' (1893), magazine article

online

* Hughes, Alex. ''France/China: intercultural imaginings'' (2007

online

* Mancall, Mark. ''China at the center: 300 years of foreign policy'' (1984). passim. * Martin, Garret. "Playing the China Card? Revisiting France's Recognition of Communist China, 1963–1964." ''Journal of Cold War Studies'' 10.1 (2008): 52–80. * Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''International Relations of the Chinese Empire: The Period of Conflict: 1834-1860''. (1910

online

** Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''International Relations of the Chinese Empire: The Period of Submission: 1861–1893''. (1918

online

** Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''International Relations of the Chinese Empire: The Period of Subjection: 1894-1911'' (1918

online

* Morse, Hosea Ballou. ''The Trade and Administration of the Chinese Empire'' (1908

online

* Pieragastini, Steven. "State and Smuggling in Modern China: The Case of Guangzhouwan/Zhanjiang." ''Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review'' 7.1 (2018): 118–152

online

* Skocpol, Theda. "France, Russia, China: A structural analysis of social revolutions." ''Comparative Studies in Society and History'' 18.2 (1976): 175–210. * Upton, Emory. ''The Armies of Asia and Europe: Embracing Official Reports on the Armies of Japan, China, India, Persia, Italy, Russia, Austria, Germany, France, and England'' (1878)

Online

* Wellons, Patricia. "Sino‐French relations: Historical alliance vs. economic reality." ''Pacific Review'' 7.3 (1994): 341–348. * Weske, Simone. "The role of France and Germany in EU-China relations." ''CAP Working Paper'' (2007

online

* Young, Ernest. ''Ecclesiastical Colony: China's Catholic Church and the French Religious Protectorate, '' (Oxford UP, 2013)

Sciences-Po

, motto_lang = fr

, mottoeng = Roots of the Future

, type = Public research university''Grande école''

, established =

, founder = Émile Boutmy

, accreditation ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:China-France relations

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

Bilateral relations of France