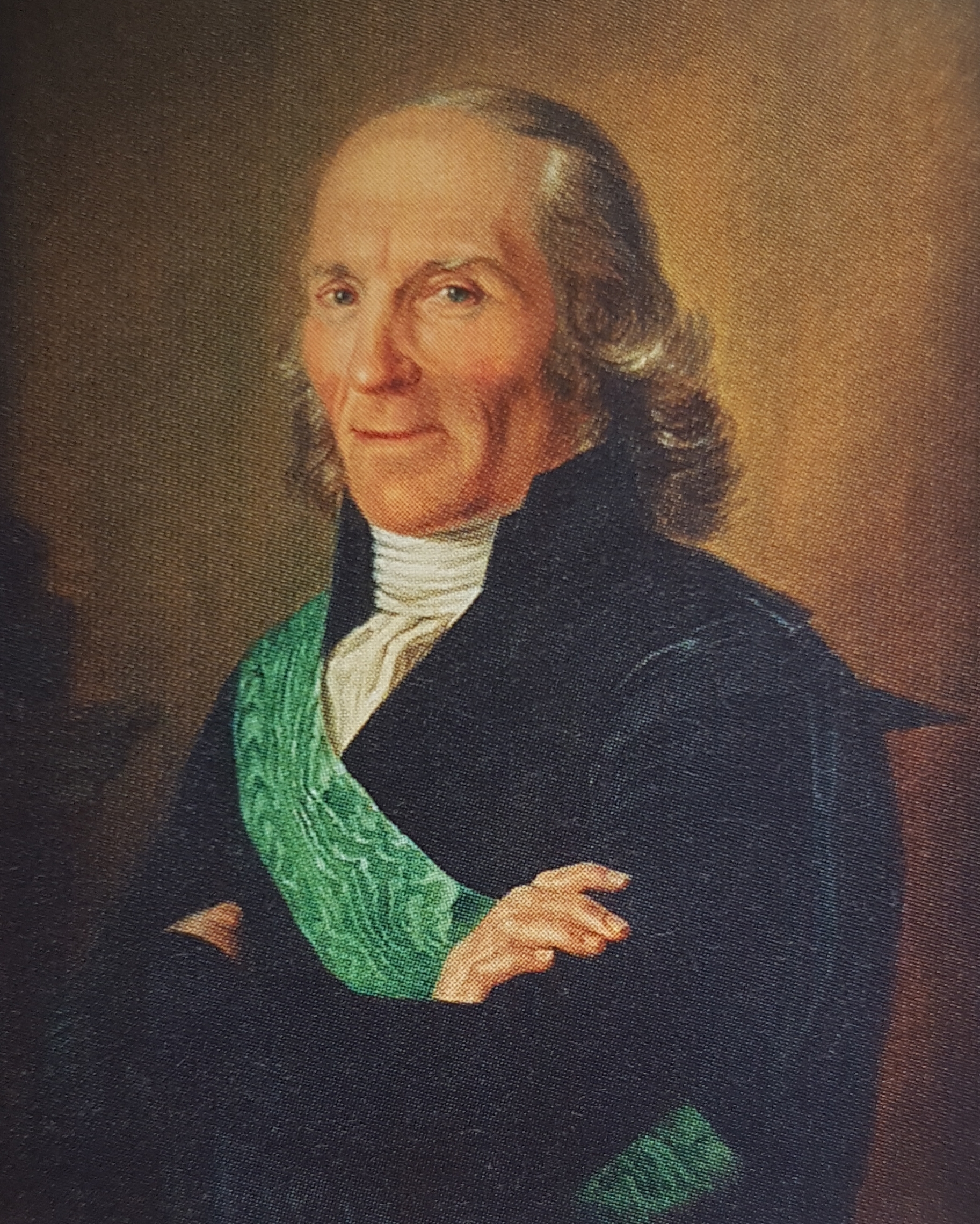

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707

– 10 January 1778), also known after

ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,

[ Blunt (2004), p. 171.] was a Swedish

biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

and

physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

who formalised

binomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

, the modern system of naming organisms. He is known as the "father of modern

taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

". Many of his writings were in Latin; his name is rendered in Latin as and, after his 1761 ennoblement, as .

Linnaeus was the son of a

curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are as ...

and was born in

Råshult, in the countryside of

Småland

Småland () is a historical Provinces of Sweden, province () in southern Sweden.

Småland borders Blekinge, Scania, Halland, Västergötland, Östergötland and the island Öland in the Baltic Sea. The name ''Småland'' literally means "small la ...

, southern

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

. He received most of his higher education at

Uppsala University

Uppsala University (UU) () is a public university, public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the List of universities in Sweden, oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in operation.

Initially fou ...

and began giving lectures in botany there in 1730. He lived abroad between 1735 and 1738, where he studied and also published the first edition of his ' in the Netherlands. He then returned to Sweden where he became professor of medicine and botany at Uppsala. In the 1740s, he was sent on several journeys through Sweden to find and classify plants and animals. In the 1750s and 1760s, he continued to collect and classify animals, plants, and minerals, while publishing several volumes. By the time of his death in 1778, he was one of the most acclaimed scientists in Europe.

Philosopher

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

sent him the message: "Tell him I know no greater man on Earth."

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

wrote: "With the exception of

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

, I know no one among the no longer living who has influenced me more strongly."

Swedish author

August Strindberg

Johan August Strindberg (; ; 22 January 184914 May 1912) was a Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist, and painter.Lane (1998), 1040. A prolific writer who often drew directly on his personal experience, Strindberg wrote more than 60 pla ...

wrote: "Linnaeus was in reality a poet who happened to become a naturalist."

Linnaeus has been called ' (Prince of Botanists) and "The

Pliny of the North". He is also considered one of the founders of modern

ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

.

In botany, the abbreviation L. is used to indicate Linnaeus as the authority for a species' name. In zoology, the abbreviation Linnaeus is generally used; the abbreviations L., Linnæus, and Linné are also used. In older publications, the abbreviation "Linn." is found. Linnaeus's remains constitute the

type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

for the species ''

Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

'' following the

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted Convention (norm), convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific name, scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the I ...

, since the sole specimen that he is known to have examined was himself.

[ICZN Chapter 16, Article 72.4.1.1]

– "For a nominal species or subspecies established before 2000, any evidence, published or unpublished, may be taken into account to determine what specimens constitute the type series." and Article 73.1.2 – "If the nominal species-group taxon is based on a single specimen, either so stated or implied in the original publication, that specimen is the holotype fixed by monotypy (see Recommendation 73F). If the taxon was established before 2000 evidence derived from outside the work itself may be taken into account rt. 72.4.1.1to help identify the specimen."

Early life

Childhood

Linnaeus was born in the village of

Råshult in

Småland

Småland () is a historical Provinces of Sweden, province () in southern Sweden.

Småland borders Blekinge, Scania, Halland, Västergötland, Östergötland and the island Öland in the Baltic Sea. The name ''Småland'' literally means "small la ...

, Sweden, on 23 May 1707. He was the first child of Nicolaus (Nils) Ingemarsson (who later adopted the family name Linnaeus) and Christina Brodersonia. His siblings were Anna Maria Linnæa, Sofia Juliana Linnæa, Samuel Linnæus (who would eventually succeed their father as

rector of Stenbrohult and write a manual on

beekeeping

Beekeeping (or apiculture, from ) is the maintenance of bee colonies, commonly in artificial beehives. Honey bees in the genus '' Apis'' are the most commonly kept species but other honey producing bees such as '' Melipona'' stingless bees are ...

),

and Emerentia Linnæa. His father taught him Latin as a small child.

One of a long line of peasants and priests, Nils was an amateur

botanist

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, a

Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

minister, and the

curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are as ...

of the small village of Stenbrohult in Småland. Christina was the daughter of the rector of Stenbrohult, Samuel Brodersonius.

A year after Linnaeus's birth, his grandfather Samuel Brodersonius died, and his father Nils became the rector of Stenbrohult. The family moved into the

rectory

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of a given religion, serving as both a home and a base for the occupant's ministry. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, p ...

from the curate's house.

Even in his early years, Linnaeus seemed to have a liking for plants, flowers in particular. Whenever he was upset, he was given a flower, which immediately calmed him. Nils spent much time in his garden and often showed flowers to Linnaeus and told him their names. Soon Linnaeus was given his own patch of earth where he could grow plants.

Carl's father was the first in his ancestry to adopt a permanent surname. Before that, ancestors had used the

patronymic

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (more specifically an avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor. It is the male equivalent of a matronymic.

Patronymics are used, b ...

naming system of Scandinavian countries: his father was named Ingemarsson after his father Ingemar Bengtsson. When Nils was admitted to the

Lund University

Lund University () is a Public university, public research university in Sweden and one of Northern Europe's oldest universities. The university is located in the city of Lund in the Swedish province of Scania. The university was officially foun ...

, he had to take on a family name. He adopted the Latinate name Linnæus after a giant

linden tree

''Tilia'' is a genus of about 30 species of trees or bushes, native throughout most of the temperateness, temperate Northern Hemisphere. The tree is known as linden for the European species, and basswood for North American species. In Great Bri ...

(or lime tree), ' in Swedish, that grew on the family homestead.

[ Blunt (2004), p. 12.] This name was spelled with the

æ ligature. When Carl was born, he was named Carl Linnæus, with his father's family name. The son also always spelled it with the æ ligature, both in handwritten documents and in publications.

[ Blunt (2004), p. 13.] Carl's patronymic would have been Nilsson, as in Carl Nilsson Linnæus.

Early education

Linnaeus's father began teaching him basic Latin, religion, and geography at an early age. When Linnaeus was seven, Nils decided to hire a tutor for him. The parents picked Johan Telander, a son of a local

yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of Serfdom, servants in an Peerage of England, English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in Kingdom of England, mid-1 ...

. Linnaeus did not like him, writing in his autobiography that Telander "was better calculated to extinguish a child's talents than develop them".

Two years after his tutoring had begun, he was sent to the Lower

Grammar School

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a Latin school, school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented Se ...

at

Växjö

Växjö () is a city and the seat of Växjö Municipality, Kronoberg County, Sweden. It had 71,282 inhabitants (2020) out of a Municipalities of Sweden, municipal population of 97,349 (2024). It is the administrative, cultural, and industrial ce ...

in 1717. Linnaeus rarely studied, often going to the countryside to look for plants. At some point, his father went to visit him and, after hearing critical assessments by his preceptors, he decided to put the youth as an apprentice to some honest cobbler. He reached the last year of the Lower School when he was fifteen, which was taught by the headmaster, Daniel Lannerus, who was interested in botany. Lannerus noticed Linnaeus's interest in botany and gave him the run of his garden.

He also introduced him to Johan Rothman, the state doctor of Småland and a teacher at

Katedralskolan (a

gymnasium) in Växjö. Also a botanist, Rothman broadened Linnaeus's interest in botany and helped him develop an interest in medicine. By the age of 17, Linnaeus had become well acquainted with the existing botanical literature. He remarks in his journal that he "read day and night, knowing like the back of my hand, Arvidh Månsson's ''Rydaholm Book of Herbs'', Tillandz's ''Flora Åboensis'',

Palmberg's ''Serta Florea Suecana'', Bromelii's ''Chloros Gothica'' and Rudbeckii's ''Hortus Upsaliensis''".

Linnaeus entered the Växjö Katedralskola in 1724, where he studied mainly

Greek,

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

,

theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, and

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, a curriculum designed for boys preparing for the priesthood. In the last year at the gymnasium, Linnaeus's father visited to ask the professors how his son's studies were progressing; to his dismay, most said that the boy would never become a scholar. Rothman believed otherwise, suggesting Linnaeus could have a future in medicine. The doctor offered to have Linnaeus live with his family in Växjö and to teach him

physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

and botany. Nils accepted this offer.

[ Blunt (2004), pp. 17–18.]

University studies

Lund

Rothman showed Linnaeus that botany was a serious subject. He taught Linnaeus to classify plants according to

Tournefort's system. Linnaeus was also taught about the sexual reproduction of plants, according to

Sébastien Vaillant.

In 1727, Linnaeus, age 21, enrolled in

Lund University

Lund University () is a Public university, public research university in Sweden and one of Northern Europe's oldest universities. The university is located in the city of Lund in the Swedish province of Scania. The university was officially foun ...

in

Skåne

Scania ( ), also known by its native name of Skåne (), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces () of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous w ...

. He was registered as ', the Latin form of his full name, which he also used later for his Latin publications.

Professor

Kilian Stobæus, natural scientist, physician and historian, offered Linnaeus tutoring and lodging, as well as the use of his library, which included many books about botany. He also gave the student free admission to his lectures. In his spare time, Linnaeus explored the flora of Skåne, together with students sharing the same interests.

Uppsala

In August 1728, Linnaeus decided to attend

Uppsala University

Uppsala University (UU) () is a public university, public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the List of universities in Sweden, oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in operation.

Initially fou ...

on the advice of Rothman, who believed it would be a better choice if Linnaeus wanted to study both medicine and botany. Rothman based this recommendation on the two professors who taught at the medical faculty at Uppsala:

Olof Rudbeck the Younger and

Lars Roberg. Although Rudbeck and Roberg had undoubtedly been good professors, by then they were older and not so interested in teaching. Rudbeck no longer gave public lectures, and had others stand in for him. The botany, zoology, pharmacology and anatomy lectures were not in their best state. In Uppsala, Linnaeus met a new benefactor,

Olof Celsius, who was a professor of theology and an amateur botanist. He received Linnaeus into his home and allowed him use of his library, which was one of the richest botanical libraries in Sweden.

In 1729, Linnaeus wrote a thesis, ' on

plant sexual reproduction. This attracted the attention of Rudbeck; in May 1730, he selected Linnaeus to give lectures at the University although the young man was only a second-year student. His lectures were popular, and Linnaeus often addressed an audience of 300 people. In June, Linnaeus moved from Celsius's house to Rudbeck's to become the tutor of the three youngest of his 24 children. His friendship with Celsius did not wane and they continued their botanical expeditions. Over that winter, Linnaeus began to doubt Tournefort's system of classification and decided to create one of his own. His plan was to divide the plants by the number of

stamen

The stamen (: stamina or stamens) is a part consisting of the male reproductive organs of a flower. Collectively, the stamens form the androecium., p. 10

Morphology and terminology

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filament ...

s and

pistil

Gynoecium (; ; : gynoecia) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl (botany), whorl of a flower; it consists ...

s. He began writing several books, which would later result in, for example, ' and '. He also produced a book on the plants grown in the

Uppsala Botanical Garden, '.

[ Blunt (2001), pp. 36–37.]

Rudbeck's former assistant,

Nils Rosén, returned to the University in March 1731 with a degree in medicine. Rosén started giving anatomy lectures and tried to take over Linnaeus's botany lectures, but Rudbeck prevented that. Until December, Rosén tutored Linnaeus privately in medicine. In December, Linnaeus had a "disagreement" with Rudbeck's wife and had to move out of his mentor's house; his relationship with Rudbeck did not appear to suffer. That Christmas, Linnaeus returned home to Stenbrohult to visit his parents for the first time in about three years. His mother had disapproved of his failing to become a priest, but she was pleased to learn he was teaching at the University.

Expedition to Lapland

During a visit with his parents, Linnaeus told them about his plan to travel to

Lapland; Rudbeck had made the journey in 1695, but the detailed results of his exploration were lost in a fire seven years afterwards. Linnaeus's hope was to find new plants, animals and possibly valuable minerals. He was also curious about the customs of the native

Sami people

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise ...

, reindeer-herding nomads who wandered Scandinavia's vast tundras. In April 1732, Linnaeus was awarded a grant from the

Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala for his journey.

Linnaeus began his expedition from Uppsala on 12 May 1732, just before he turned 25.

He travelled on foot and horse, bringing with him his journal, botanical and

ornithological manuscripts and sheets of paper for pressing plants. Near

Gävle

Gävle ( ; ) is a Urban areas in Sweden, city in Sweden, the seat of Gävle Municipality and the capital of Gävleborg County. It had 79,004 inhabitants in 2020, which makes it the List of cities in Sweden, 13th-most-populated city in Sweden. I ...

he found great quantities of ''Campanula serpyllifolia'', later known as ''

Linnaea borealis'', the twinflower that would become his favourite. He sometimes dismounted on the way to examine a flower or rock and was particularly interested in

moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular plant, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic phylum, division Bryophyta (, ) ''sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryo ...

es and

lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

s, the latter a main part of the diet of the

reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

, a common and economically important animal in Lapland.

Linnaeus travelled clockwise around the coast of the

Gulf of Bothnia

The Gulf of Bothnia (; ; ) is divided into the Bothnian Bay and the Bothnian Sea, and it is the northernmost arm of the Baltic Sea, between Finland's west coast ( East Bothnia) and the northern part of Sweden's east coast ( West Bothnia an ...

, making major inland incursions from

Umeå

Umeå ( , , , locally ; ; ; ; ) is a city in northeast Sweden. It is the seat of Umeå Municipality and the capital of Västerbotten County.

Situated on the Ume River, Umeå is the largest Urban areas in Sweden, locality in Norrland and the t ...

,

Luleå

Luleå ( , , locally ; ; ) is a Cities in Sweden, city on the coast of northern Sweden, and the County Administrative Boards of Sweden, capital of Norrbotten County, the northernmost county in Sweden. Luleå has 48,728 inhabitants in its urban ...

and

Tornio. He returned from his six-month-long, over expedition in October, having gathered and observed many plants, birds and rocks.

[ Broberg (2006), p. 29.] Although Lapland was a region with limited

biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variability of life, life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and Phylogenetics, phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distribut ...

, Linnaeus described about 100 previously unidentified plants. These became the basis of his book '. However, on the expedition to Lapland, Linnaeus used Latin names to describe organisms because he had not yet developed the binomial system.

In ' Linnaeus's ideas about

nomenclature

Nomenclature (, ) is a system of names or terms, or the rules for forming these terms in a particular field of arts or sciences. (The theoretical field studying nomenclature is sometimes referred to as ''onymology'' or ''taxonymy'' ). The principl ...

and

classification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

were first used in a practical way, making this the first proto-modern

Flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

.

The account covered 534 species, used the Linnaean classification system and included, for the described species, geographical distribution and taxonomic notes. It was

Augustin Pyramus de Candolle

Augustin Pyramus (or Pyrame) de Candolle (, , ; 4 February 17789 September 1841) was a Swiss people, Swiss botany, botanist. René Louiche Desfontaines launched de Candolle's botanical career by recommending him at a herbarium. Within a couple ...

who attributed Linnaeus with ' as the first example in the botanical genre of Flora writing. Botanical historian

E. L. Greene described ' as "the most classic and delightful" of Linnaeus's works.

[ Frodin (2001), p. 27.]

It was during this expedition that Linnaeus had a

flash of insight regarding the classification of mammals. Upon observing the lower jawbone of a horse at the side of a road he was travelling, Linnaeus remarked: "If I only knew how many teeth and of what kind every animal had, how many teats and where they were placed, I should perhaps be able to work out a perfectly natural system for the arrangement of all quadrupeds."

In 1734, Linnaeus led a small group of students to

Dalarna

Dalarna (; ), also referred to by the English exonyms Dalecarlia and the Dales, is a (historical province) in central Sweden.

Dalarna adjoins Härjedalen, Hälsingland, Gästrikland, Västmanland and Värmland. It is also bordered by Nor ...

. Funded by the Governor of Dalarna, the expedition was to catalogue known natural resources and discover new ones, but also to gather intelligence on Norwegian mining activities at

Røros.

Years in the Dutch Republic (1735–38)

Doctorate

His relations with Nils Rosén having worsened, Linnaeus accepted an invitation from Claes Sohlberg, son of a mining inspector, to spend the Christmas holiday in

Falun

Falun () is a city and the seat of Falun Municipality in Dalarna County, Sweden, with 37,291 inhabitants in 2010. It is also the capital of Dalarna County. Falun forms, together with Borlänge, a metropolitan area with just over 100,000 inhabit ...

, where Linnaeus was permitted to visit the mines.

In April 1735, at the suggestion of Sohlberg's father, Linnaeus and Sohlberg set out for the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

, where Linnaeus intended to study medicine at the

University of Harderwijk while tutoring Sohlberg in exchange for an annual salary. At the time, it was common for Swedes to pursue doctoral degrees in the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, then a highly revered place to study natural history.

On the way, the pair stopped in

Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

, where they met the mayor, who proudly showed them a supposed wonder of nature in his possession: the

taxidermied remains of a seven-headed

hydra. Linnaeus quickly discovered the specimen was a

fake, cobbled together from the jaws and paws of weasels and the skins of snakes. The provenance of the hydra suggested to Linnaeus that it had been manufactured by monks to represent the

Beast of Revelation. Even at the risk of incurring the mayor's wrath, Linnaeus made his observations public, dashing the mayor's dreams of selling the hydra for an enormous sum. Linnaeus and Sohlberg were forced to flee from Hamburg.

[ Anderson (1997), pp. 60–61.]

Linnaeus began working towards his degree as soon as he reached

Harderwijk, a university known for awarding degrees in as little as a week.

He submitted a dissertation, written back in Sweden, entitled ''Dissertatio medica inauguralis in qua exhibetur hypothesis nova de febrium intermittentium causa'',

[That is, ''Inaugural thesis in medicine, in which a new hypothesis on the cause of intermittent fevers is presented''] in which he laid out his hypothesis that

malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

arose only in areas with clay-rich soils.

Although he failed to identify the true source of disease transmission, (i.e., the ''

Anopheles

''Anopheles'' () is a genus of mosquito first described by the German entomologist Johann Wilhelm Meigen, J. W. Meigen in 1818, and are known as nail mosquitoes and marsh mosquitoes. Many such mosquitoes are Disease vector, vectors of the paras ...

''

mosquito

Mosquitoes, the Culicidae, are a Family (biology), family of small Diptera, flies consisting of 3,600 species. The word ''mosquito'' (formed by ''Musca (fly), mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish and Portuguese for ''little fly''. Mos ...

), he did correctly predict that ''

Artemisia annua'' (

wormwood) would become a source of

antimalarial medications.

[

Within two weeks he had completed his oral and practical examinations and was awarded a doctoral degree.][ Blunt (2001), p. 94.]

That summer Linnaeus reunited with Peter Artedi, a friend from Uppsala with whom he had once made a pact that should either of the two predecease the other, the survivor would finish the decedent's work. Ten weeks later, Artedi drowned in the canals of Amsterdam

Amsterdam, capital of the Netherlands, has more than of ''grachten'' (canals), about 90 islands and 1,500 bridges. The three main canals (Herengracht, Prinsengracht and Keizersgracht), dug in the 17th century during the Dutch Golden Age, form co ...

, leaving behind an unfinished manuscript on the classification of fish.

Publishing of '

One of the first scientists Linnaeus met in the Netherlands was Johan Frederik Gronovius, to whom Linnaeus showed one of the several manuscripts he had brought with him from Sweden. The manuscript described a new system for classifying plants. When Gronovius saw it, he was very impressed, and offered to help pay for the printing. With an additional monetary contribution by the Scottish doctor Isaac Lawson, the manuscript was published as ' (1735).

Linnaeus became acquainted with one of the most respected physicians and botanists in the Netherlands, Herman Boerhaave

Herman Boerhaave (, 31 December 1668 – 23 September 1738Underwood, E. Ashworth. "Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years." ''The British Medical Journal'' 4, no. 5634 (1968): 820–25. .) was a Dutch chemist, botanist, Christian humanist, and ph ...

, who tried to convince Linnaeus to make a career there. Boerhaave offered him a journey to South Africa and America, but Linnaeus declined, stating he would not stand the heat. Instead, Boerhaave convinced Linnaeus that he should visit the botanist Johannes Burman. After his visit, Burman, impressed with his guest's knowledge, decided Linnaeus should stay with him during the winter. During his stay, Linnaeus helped Burman with his '. Burman also helped Linnaeus with the books on which he was working: ' and '.[ Blunt (2004), pp. 100–102.]

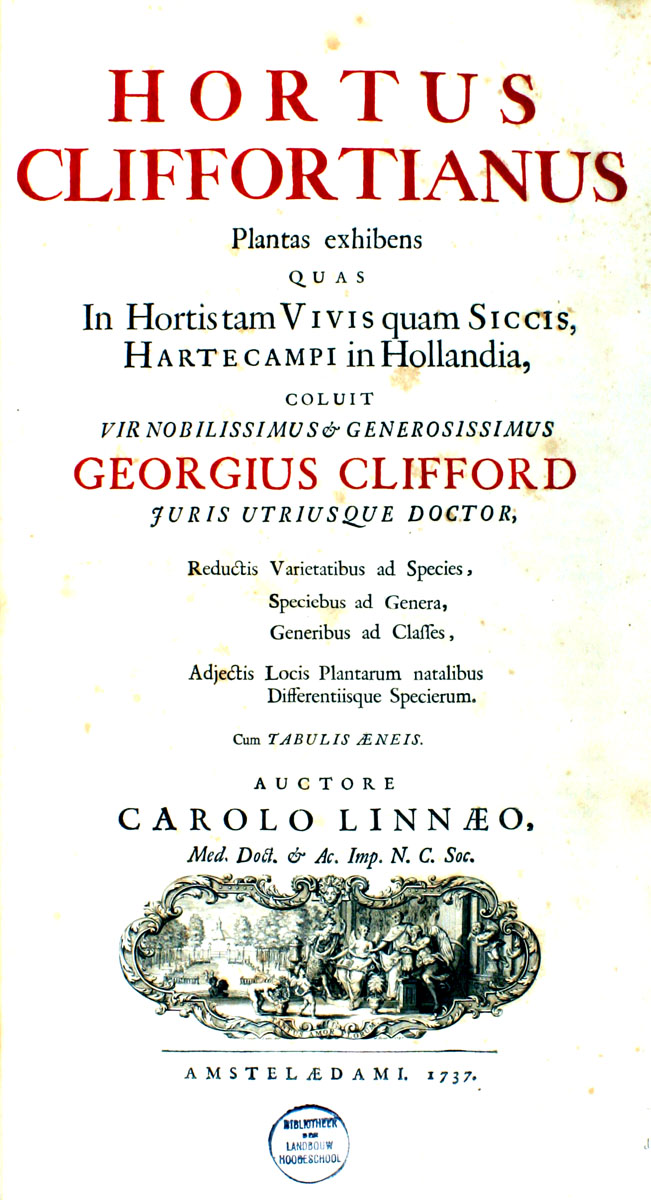

George Clifford, Philip Miller, and Johann Jacob Dillenius

In August 1735, during Linnaeus's stay with Burman, he met George Clifford III, a director of the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

and the owner of a rich botanical garden at the estate of Hartekamp in Heemstede

Heemstede () is a town and a municipality in the Western Netherlands, in the province of North Holland. In 2021, it had a population of 27,545. Located just south of the city of Haarlem on the border with South Holland, it is one of the richest ...

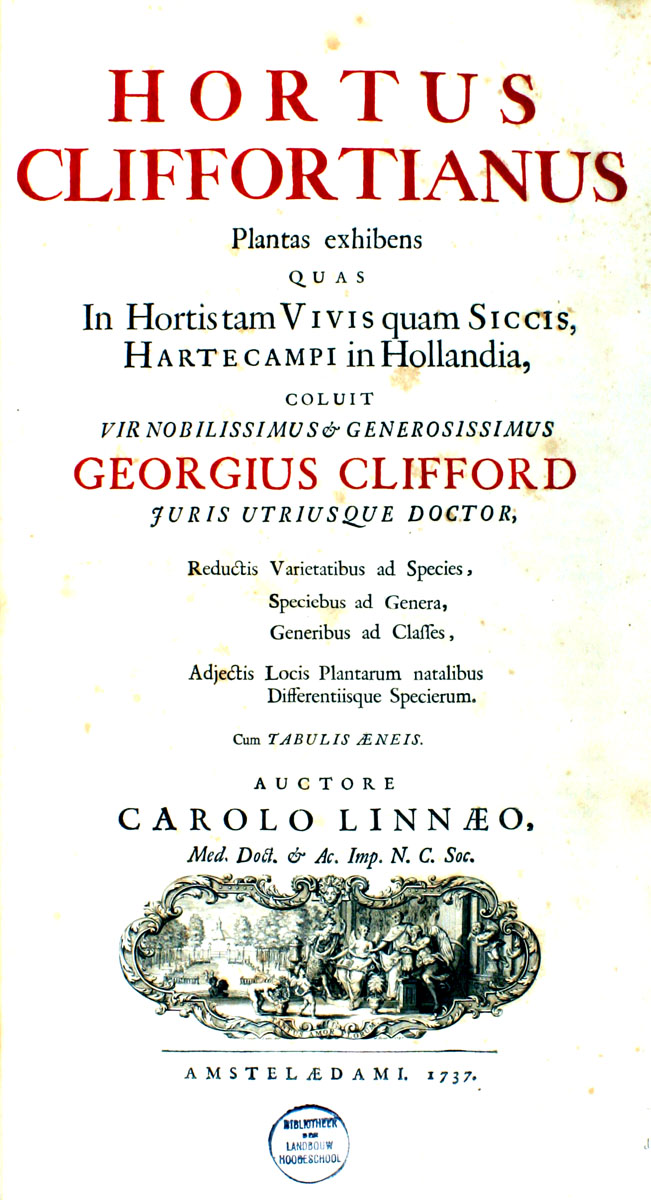

. Clifford was very impressed with Linnaeus's ability to classify plants, and invited him to become his physician and superintendent of his garden. Linnaeus had already agreed to stay with Burman over the winter, and could thus not accept immediately. However, Clifford offered to compensate Burman by offering him a copy of Sir Hans Sloane's ''Natural History of Jamaica'', a rare book, if he let Linnaeus stay with him, and Burman accepted. On 24 September 1735, Linnaeus moved to Hartekamp to become personal physician to Clifford, and curator of Clifford's herbarium. He was paid 1,000 florins a year, with free board and lodging. Though the agreement was only for a winter of that year, Linnaeus practically stayed there until 1738. It was here that he wrote a book ''Hortus Cliffortianus'', in the preface of which he described his experience as "the happiest time of my life". (A portion of Hartekamp was declared as public garden in April 1956 by the Heemstede local authority, and was named "Linnaeushof". It eventually became, as it is claimed, the biggest playground in Europe.)

In July 1736, Linnaeus travelled to England, at Clifford's expense. He went to London to visit Sir Hans Sloane, a collector of natural history, and to see his cabinet, as well as to visit the Chelsea Physic Garden

The Chelsea Physic Garden was established as the Apothecaries' Garden in London, England, in 1673 by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries to grow plants to be used as medicines. This four acre physic garden, the term here referring to the scie ...

and its keeper, Philip Miller

Philip Miller Royal Society, FRS (1691 – 18 December 1771) was an English botany, botanist and gardener of Scottish descent. Miller was chief gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden for nearly 50 years from 1722, and wrote the highly popular ...

. He taught Miller about his new system of subdividing plants, as described in '. At first, Miller was reluctant to use the new binomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

, preferring instead the classifications of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (5 June 165628 December 1708) was a French botanist, notable as the first to make a clear definition of the concept of genus for plants. Botanist Charles Plumier was his pupil and accompanied him on his voyages.

Li ...

and John Ray. Nevertheless, Linnaeus applauded Miller's ''Gardeners Dictionary''. The conservative Miller actually retained in his dictionary a number of pre-Linnaean binomial signifiers discarded by Linnaeus but which have been retained by modern botanists. He only fully changed to the Linnaean system in the edition of '' The Gardeners Dictionary'' of 1768. Miller ultimately was impressed, and from then on started to arrange the garden according to Linnaeus's system.

Linnaeus also travelled to Oxford University to visit the botanist Johann Jacob Dillenius. He failed to make Dillenius publicly fully accept his new classification system, though the two men remained in correspondence for many years afterwards. Linnaeus dedicated his ''Critica Botanica'' to him, as "''opus botanicum quo absolutius mundus non-vidit''". Linnaeus would later name a genus of tropical tree Dillenia in his honour. He then returned to Hartekamp, bringing with him many specimens of rare plants. The next year, 1737, he published ', in which he described 935 genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

of plants, and shortly thereafter he supplemented it with ', with another sixty (''sexaginta'') genera.

His work at Hartekamp led to another book, ', a catalogue of the botanical holdings in the herbarium and botanical garden of Hartekamp. He wrote it in nine months (completed in July 1737), but it was not published until 1738.["If this is not Helen's '' Nepenthes'', it certainly will be for all botanists. What botanist would not be filled with admiration if, after a long journey, he should find this wonderful plant. In his astonishment past ills would be forgotten when beholding this admirable work of the Creator!" (translated from Latin by Harry Veitch)]

Linnaeus stayed with Clifford at Hartekamp until 18 October 1737 (new style), when he left the house to return to Sweden. Illness and the kindness of Dutch friends obliged him to stay some months longer in Holland. In May 1738, he set out for Sweden again. On the way home, he stayed in Paris for about a month, visiting botanists such as Antoine de Jussieu. After his return, Linnaeus never again left Sweden.[ Koerner (1999), p. 56.]

Return to Sweden

When Linnaeus returned to Sweden on 28 June 1738, he went to

When Linnaeus returned to Sweden on 28 June 1738, he went to Falun

Falun () is a city and the seat of Falun Municipality in Dalarna County, Sweden, with 37,291 inhabitants in 2010. It is also the capital of Dalarna County. Falun forms, together with Borlänge, a metropolitan area with just over 100,000 inhabit ...

, where he entered into an engagement to Sara Elisabeth Moræa. Three months later, he moved to Stockholm to find employment as a physician, and thus to make it possible to support a family.Praeses

''Praeses'' (Latin ''praesides'') is a Latin word meaning "placed before" or "at the head". In antiquity, notably under the Roman Dominate, it was used to refer to Roman governors; it continues to see some use for various modern positions.

...

of the academy by drawing of lots.

Because his finances had improved and were now sufficient to support a family, he received permission to marry his fiancée, Sara Elisabeth Moræa. Their wedding was held 26 June 1739. Seventeen months later, Sara gave birth to their first son, Carl. Two years later, a daughter, Elisabeth Christina, was born, and the subsequent year Sara gave birth to Sara Magdalena, who died when 15 days old. Sara and Linnaeus would later have four other children: Lovisa, Sara Christina, Johannes and Sophia.[

] In May 1741, Linnaeus was appointed Professor of Medicine at Uppsala University, first with responsibility for medicine-related matters. Soon, he changed place with the other Professor of Medicine, Nils Rosén, and thus was responsible for the Botanical Garden (which he would thoroughly reconstruct and expand), botany and

In May 1741, Linnaeus was appointed Professor of Medicine at Uppsala University, first with responsibility for medicine-related matters. Soon, he changed place with the other Professor of Medicine, Nils Rosén, and thus was responsible for the Botanical Garden (which he would thoroughly reconstruct and expand), botany and natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

, instead. In October that same year, his wife and nine-month-old son followed him to live in Uppsala.

Öland and Gotland

Ten days after he was appointed professor, he undertook an expedition to the island provinces of Öland and Gotland

Gotland (; ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a Provinces of Sweden, province/Counties of Sweden, county (Swedish län), Municipalities of Sweden, municipality, a ...

with six students from the university to look for plants useful in medicine. They stayed on Öland until 21 June, then sailed to Visby

Visby () is an urban areas in Sweden, urban area in Sweden and the seat of Gotland Municipality in Gotland County on the island of Gotland with 24,330 inhabitants . Visby is also the episcopal see for the Diocese of Visby. The Hanseatic League, ...

in Gotland. Linnaeus and the students stayed on Gotland for about a month, and then returned to Uppsala. During this expedition, they found 100 previously unrecorded plants. The observations from the expedition were later published in ', written in Swedish. Like ', it contained both zoological and botanical observations, as well as observations concerning the culture in Öland and Gotland.[ Koerner (1999), p. 115.]

During the summer of 1745, Linnaeus published two more books: ' and '. ' was a strictly botanical book, while ' was zoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

.[ ]Anders Celsius

Anders Celsius (; 27 November 170125 April 1744) was a Swedes, Swedish astronomer, physicist and mathematician. He was professor of astronomy at Uppsala University from 1730 to 1744, but traveled from 1732 to 1735 visiting notable observatories ...

had created the temperature scale named after him in 1742. Celsius's scale was originally inverted compared to the way it is used today, with water boiling at 0 °C and freezing at 100 °C. Linnaeus was the one who inverted the scale to its present usage, in 1745.

Västergötland

In the summer of 1746, Linnaeus was once again commissioned by the Government to carry out an expedition, this time to the Swedish province of Västergötland

Västergötland (), also known as West Gothland or the Latinized version Westrogothia in older literature, is one of the 25 traditional non-administrative provinces of Sweden (''landskap'' in Swedish), situated in the southwest of Sweden.

Vä ...

. He set out from Uppsala on 12 June and returned on 11 August. On the expedition his primary companion was Erik Gustaf Lidbeck, a student who had accompanied him on his previous journey. Linnaeus described his findings from the expedition in the book ', published the next year.Scania

Scania ( ), also known by its native name of Skåne (), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces () of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous w ...

. This journey was postponed, as Linnaeus felt too busy.[

In 1747, Linnaeus was given the title archiater, or chief physician, by the Swedish king Adolf Frederick—a mark of great respect. The same year he was elected member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin.

]

Scania

In the spring of 1749, Linnaeus could finally journey to Scania

Scania ( ), also known by its native name of Skåne (), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces () of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous w ...

, again commissioned by the government. With him he brought his student Olof Söderberg. On the way to Scania, he made his last visit to his brothers and sisters in Stenbrohult since his father had died the previous year. The expedition was similar to the previous journeys in most aspects, but this time he was also ordered to find the best place to grow walnut

A walnut is the edible seed of any tree of the genus '' Juglans'' (family Juglandaceae), particularly the Persian or English walnut, '' Juglans regia''. They are accessory fruit because the outer covering of the fruit is technically an i ...

and Swedish whitebeam trees; these trees were used by the military to make rifles. While there, they also visited the Ramlösa mineral spa, where he remarked on the quality of its ferruginous water. The journey was successful, and Linnaeus's observations were published the next year in '.[ Koerner (1999), p. 116.]

Rector of Uppsala University

In 1750, Linnaeus became rector of Uppsala University, starting a period where natural sciences were esteemed.

In 1750, Linnaeus became rector of Uppsala University, starting a period where natural sciences were esteemed.[ Perhaps the most important contribution he made during his time at Uppsala was to teach; many of his students travelled to various places in the world to collect botanical samples. Linnaeus called the best of these students his "apostles". His lectures were normally very popular and were often held in the Botanical Garden. He tried to teach the students to think for themselves and not trust anybody, not even him. Even more popular than the lectures were the botanical excursions made every Saturday during summer, where Linnaeus and his students explored the flora and fauna in the vicinity of Uppsala.

]

''Philosophia Botanica''

Linnaeus published '' Philosophia Botanica'' in 1751. The book contained a complete survey of the taxonomy system he had been using in his earlier works. It also contained information of how to keep a journal on travels and how to maintain a botanical garden.

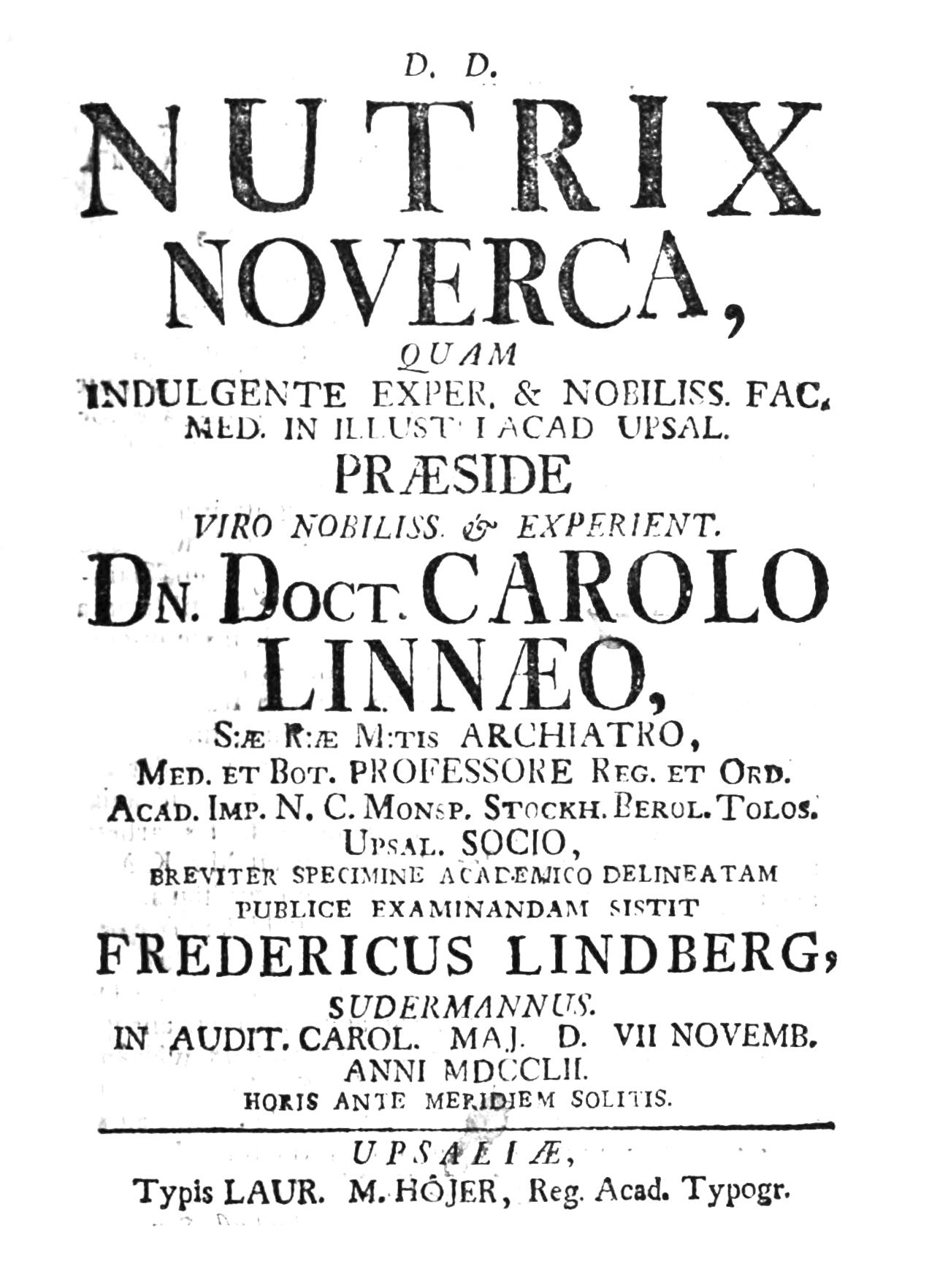

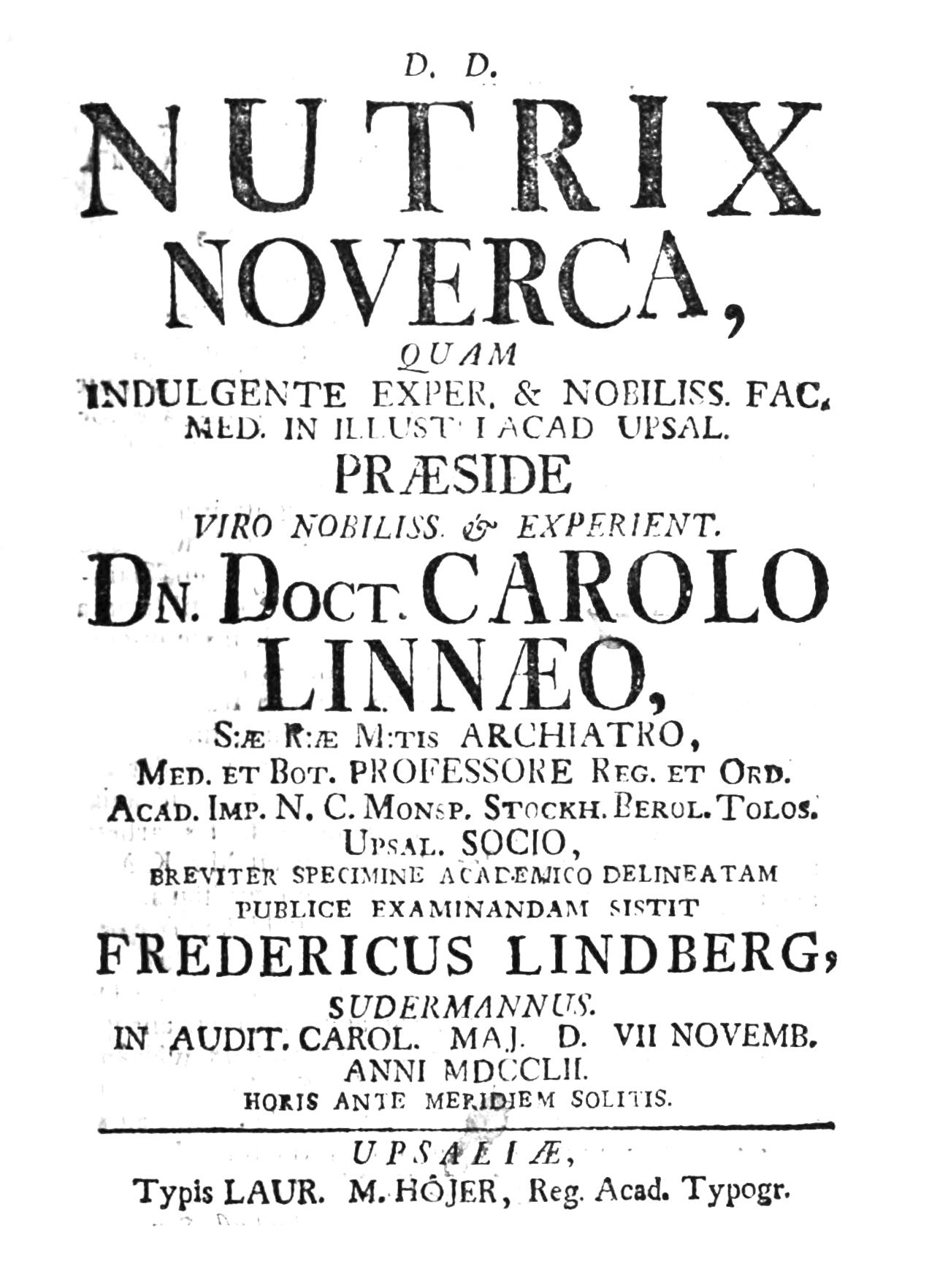

''Nutrix Noverca''

During Linnaeus's time it was normal for upper class women to have

During Linnaeus's time it was normal for upper class women to have wet nurse

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeding, breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, if she is unable to nurse the child herself sufficiently or chooses not to do so. Wet-nursed children may be known a ...

s for their babies. Linnaeus joined an ongoing campaign to end this practice in Sweden and promote breast-feeding by mothers. In 1752 Linnaeus published a thesis along with Frederick Lindberg, a physician student, based on their experiences. In the tradition of the period, this dissertation was essentially an idea of the presiding reviewer (''prases'') expounded upon by the student. Linnaeus's dissertation was translated into French by J. E. Gilibert in 1770 as . Linnaeus suggested that children might absorb the personality of their wet nurse through the milk. He admired the child care practices of the Lapps

''Species Plantarum''

Linnaeus published ''Species Plantarum'', the work which is now internationally accepted as the starting point of modern botanical nomenclature

Botanical nomenclature is the formal, scientific naming of plants. It is related to, but distinct from taxonomy (biology), taxonomy. Plant taxonomy is concerned with grouping and classifying plants; Botany, botanical nomenclature then provides na ...

, in 1753.[ Stace (1991)]

p. 24

The first volume was issued on 24 May, the second volume followed on 16 August of the same year. The book contained 1,200 pages and was published in two volumes; it described over 7,300 species.[ Gribbin & Gribbin (2008), p. 47.] The same year the king dubbed him knight of the Order of the Polar Star, the first civilian in Sweden to become a knight in this order. He was then seldom seen not wearing the order's insignia.

Ennoblement

Linnaeus felt Uppsala was too noisy and unhealthy, so he bought two farms in 1758: Hammarby and Sävja. The next year, he bought a neighbouring farm, Edeby. He spent the summers with his family at Hammarby; initially it only had a small one-storey house, but in 1762 a new, larger main building was added.

Linnaeus felt Uppsala was too noisy and unhealthy, so he bought two farms in 1758: Hammarby and Sävja. The next year, he bought a neighbouring farm, Edeby. He spent the summers with his family at Hammarby; initially it only had a small one-storey house, but in 1762 a new, larger main building was added.zoological nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its formal author, t ...

, the equivalent of '.nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

in 1757, but he was not ennobled until 1761. With his ennoblement, he took the name Carl von Linné (Latinised as ), 'Linné' being a shortened and gallicised version of 'Linnæus', and the German nobiliary particle ' von' signifying his ennoblement.coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon f ...

prominently features a twinflower, one of Linnaeus's favourite plants; it was given the scientific name ''Linnaea borealis'' in his honour by Gronovius. The shield in the coat of arms is divided into thirds: red, black and green for the three kingdoms of nature (animal, mineral and vegetable) in Linnaean classification; in the centre is an egg "to denote Nature, which is continued and perpetuated ''in ovo''". At the bottom is a phrase in Latin, borrowed from the Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

, which reads "''Famam extendere factis''": we extend our fame by our deeds. Linnaeus inscribed this personal motto in books that were given to him by friends.

After his ennoblement, Linnaeus continued teaching and writing. In total, he presided at 186 PhD ceremonies, with many of the dissertations written by himself. His reputation had spread over the world, and he corresponded with many different people. For example, Catherine II of Russia sent him seeds from her country. He also corresponded with Giovanni Antonio Scopoli

Giovanni Antonio Scopoli (sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Johannes Antonius Scopolius) (3 June 1723 – 8 May 1788) was an Italians, Italian physician and natural history, naturalist. His biographer Otto Guglia named him the "first ...

, "the Linnaeus of the Austrian Empire", who was a doctor and a botanist in Idrija, Duchy of Carniola

The Duchy of Carniola (, , ) was an imperial estate of the Holy Roman Empire, established under House of Habsburg, Habsburg rule on the territory of the former East Frankish March of Carniola in 1364. A hereditary land of the Habsburg monarc ...

(nowadays Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

). Scopoli communicated all of his research, findings, and descriptions (for example of the olm and the dormouse, two little animals hitherto unknown to Linnaeus). Linnaeus greatly respected Scopoli and showed great interest in his work. He named a solanaceous genus, '' Scopolia'', the source of scopolamine, after him, but because of the great distance between them, they never met.

Final years

Linnaeus was relieved of his duties in the Royal Swedish Academy of Science in 1763, but continued his work there as usual for more than ten years after.[ In 1769 he was elected to the ]American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

for his work. He stepped down as rector at Uppsala University in December 1772, mostly due to his declining health.[ Blunt (2004), p. 245.]

Linnaeus's last years were troubled by illness. He had had a disease called the Uppsala fever in 1764, but survived due to the care of Rosén. He developed sciatica

Sciatica is pain going down the leg from the lower back. This pain may go down the back, outside, or front of the leg. Onset is often sudden following activities such as heavy lifting, though gradual onset may also occur. The pain is often desc ...

in 1773, and the next year, he had a stroke which partially paralysed him. He had a second stroke in 1776, losing the use of his right side and leaving him bereft of his memory; while still able to admire his own writings, he could not recognise himself as their author.

In December 1777, he had another stroke which greatly weakened him, and eventually led to his death on 10 January 1778 in Hammarby.Uppsala Cathedral

Uppsala Cathedral () is a cathedral located between the University Hall (Uppsala University), University Hall of Uppsala University and the Fyris river in the centre of Uppsala, Sweden. A church of the Church of Sweden, the national church, in t ...

on 22 January.[ Anderson (1997), pp. 104–106.]

His library and collections were left to his widow Sara and their children. Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

, an eminent botanist, wished to purchase the collection, but his son Carl refused the offer and instead moved the collection to Uppsala. In 1783 Carl died and Sara inherited the collection, having outlived both her husband and son. She tried to sell it to Banks, but he was no longer interested; instead an acquaintance of his agreed to buy the collection. The acquaintance was a 24-year-old medical student, James Edward Smith, who bought the whole collection: 14,000 plants, 3,198 insects, 1,564 shells, about 3,000 letters and 1,600 books. Smith founded the Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript a ...

five years later.

Apostles

During Linnaeus's time as Professor and Rector of Uppsala University, he taught many devoted students, 17 of whom he called "apostles". They were the most promising, most committed students, and all of them made botanical expeditions to various places in the world, often with his help. The amount of this help varied; sometimes he used his influence as Rector to grant his apostles a scholarship or a place on an expedition. To most of the apostles he gave instructions of what to look for on their journeys. Abroad, the apostles collected and organised new plants, animals and minerals according to Linnaeus's system. Most of them also gave some of their collection to Linnaeus when their journey was finished. Thanks to these students, the Linnaean system of taxonomy spread through the world without Linnaeus ever having to travel outside Sweden after his return from Holland. The British botanist William T. Stearn notes, without Linnaeus's new system, it would not have been possible for the apostles to collect and organise so many new specimens.

During Linnaeus's time as Professor and Rector of Uppsala University, he taught many devoted students, 17 of whom he called "apostles". They were the most promising, most committed students, and all of them made botanical expeditions to various places in the world, often with his help. The amount of this help varied; sometimes he used his influence as Rector to grant his apostles a scholarship or a place on an expedition. To most of the apostles he gave instructions of what to look for on their journeys. Abroad, the apostles collected and organised new plants, animals and minerals according to Linnaeus's system. Most of them also gave some of their collection to Linnaeus when their journey was finished. Thanks to these students, the Linnaean system of taxonomy spread through the world without Linnaeus ever having to travel outside Sweden after his return from Holland. The British botanist William T. Stearn notes, without Linnaeus's new system, it would not have been possible for the apostles to collect and organise so many new specimens.[ Blunt (2004), pp. 184–185.] Many of the apostles died during their expeditions.

Early expeditions

Christopher Tärnström, the first apostle and a 43-year-old pastor with a wife and children, made his journey in 1746. He boarded a Swedish East India Company ship headed for China. Tärnström never reached his destination, dying of a tropical fever on Côn Sơn Island the same year. Tärnström's widow blamed Linnaeus for making her children fatherless, causing Linnaeus to prefer sending out younger, unmarried students after Tärnström. Six other apostles later died on their expeditions, including Pehr Forsskål and Pehr Löfling.

Cook expeditions and Japan

Daniel Solander was living in Linnaeus's house during his time as a student in Uppsala. Linnaeus was very fond of him, promising Solander his eldest daughter's hand in marriage. On Linnaeus's recommendation, Solander travelled to England in 1760, where he met the English botanist Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

. With Banks, Solander joined James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

on his expedition to Oceania on the '' Endeavour'' in 1768–71. Solander was not the only apostle to journey with James Cook; Anders Sparrman followed on the '' Resolution'' in 1772–75 bound for, among other places, Oceania and South America. Sparrman made many other expeditions, one of them to South Africa.

Perhaps the most famous and successful apostle was Carl Peter Thunberg

Carl Peter Thunberg, also known as Karl Peter von Thunberg, Carl Pehr Thunberg, or Carl Per Thunberg (11 November 1743 – 8 August 1828), was a Sweden, Swedish Natural history, naturalist and an Apostles of Linnaeus, "apostle" of Carl Linnaeus ...

, who embarked on a nine-year expedition in 1770. He stayed in South Africa for three years, then travelled to Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. All foreigners in Japan were forced to stay on the island of Dejima outside Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

, so it was thus hard for Thunberg to study the flora. He did, however, manage to persuade some of the translators to bring him different plants, and he also found plants in the gardens of Dejima. He returned to Sweden in 1779, one year after Linnaeus's death.

Major publications

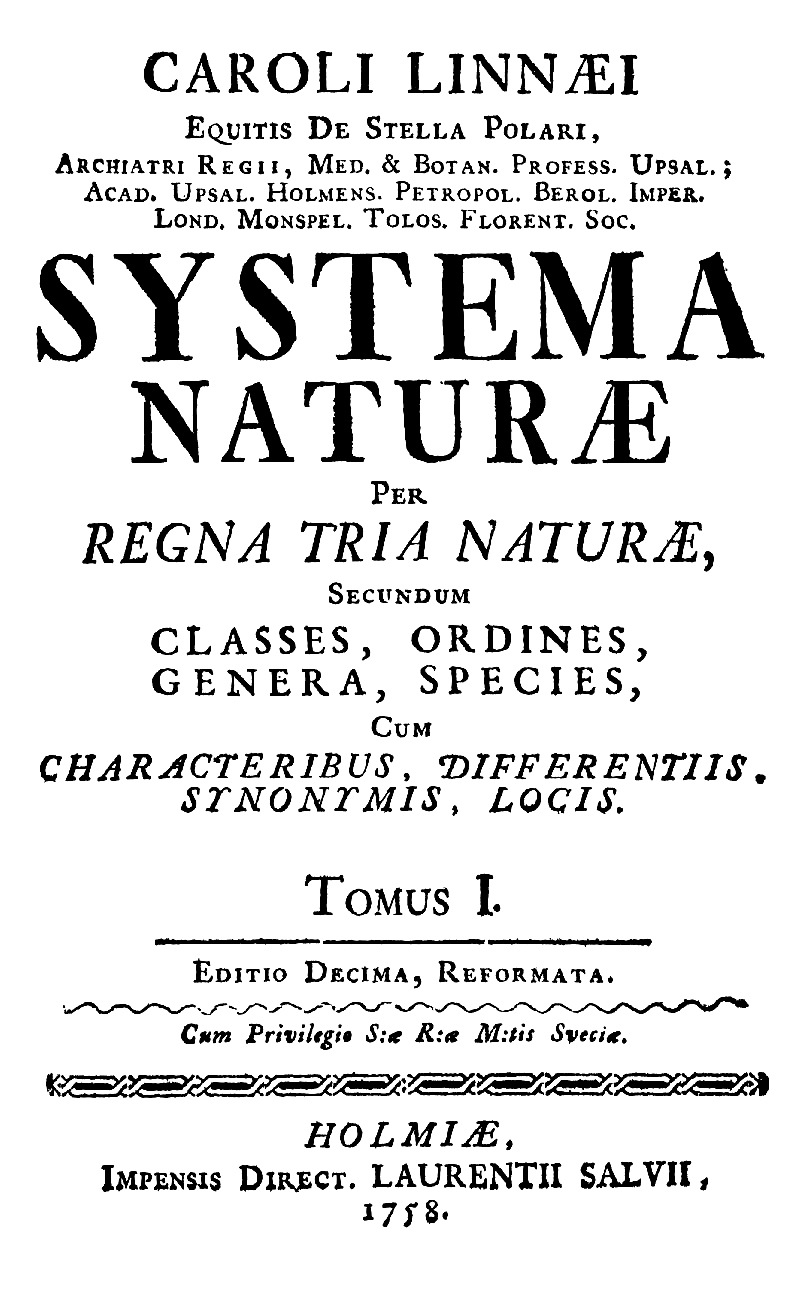

''Systema Naturae''

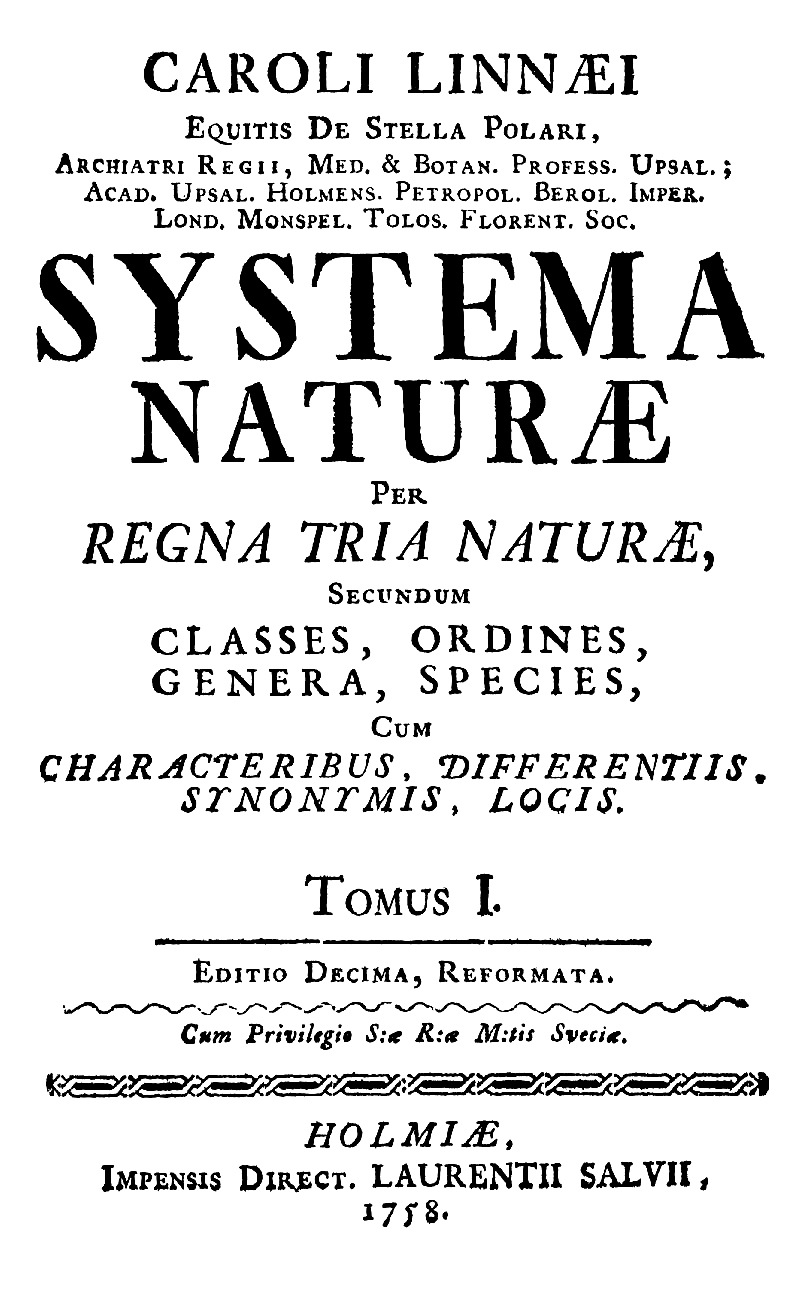

The first edition of ' was printed in the Netherlands in 1735. It was a twelve-page work. By the time it reached its 10th edition in 1758, it classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. People from all over the world sent their specimens to Linnaeus to be included. By the time he started work on the 12th edition, Linnaeus needed a new invention—the

The first edition of ' was printed in the Netherlands in 1735. It was a twelve-page work. By the time it reached its 10th edition in 1758, it classified 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. People from all over the world sent their specimens to Linnaeus to be included. By the time he started work on the 12th edition, Linnaeus needed a new invention—the index card

An index card (or record card in British English and system cards in Australian English) consists of card stock (heavy paper) cut to a standard size, used for recording and storing small amounts of discrete data. A collection of such cards ei ...

—to track classifications.

In ''Systema Naturae'', the unwieldy names mostly used at the time, such as "'", were supplemented with concise and now familiar "binomials", composed of the generic name, followed by a specific epithet—in the case given, '' Physalis angulata''. These binomials could serve as a label to refer to the species. Higher taxa were constructed and arranged in a simple and orderly manner. Although the system, now known as binomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

, was partially developed by the Bauhin brothers (see Gaspard Bauhin

Gaspard Bauhin or Caspar Bauhin (; 17 January 1560 – 5 December 1624), was a Switzerland, Swiss botanist whose ''Pinax theatri botanici'' (1623) described thousands of plants and classified them in a manner that draws comparisons to the later ...

and Johann Bauhin) almost 200 years earlier, Linnaeus was the first to use it consistently throughout the work, including in monospecific genera, and may be said to have popularised it within the scientific community.

After the decline in Linnaeus's health in the early 1770s, publication of editions of ''Systema Naturae'' went in two different directions. Another Swedish scientist, Johan Andreas Murray, issued the ''Regnum Vegetabile'' section separately in 1774 as the ''Systema Vegetabilium'', rather confusingly labelled the 13th edition. Meanwhile, a 13th edition of the entire ''Systema'' appeared in parts between 1788 and 1793 under the editorship of Johann Friedrich Gmelin

Johann Friedrich Gmelin (8 August 1748 – 1 November 1804) was a German natural history, naturalist, chemist, botanist, entomologist, herpetologist, and malacologist.

Education

Johann Friedrich Gmelin was born as the eldest son of Philipp F ...

. It was through the ''Systema Vegetabilium'' that Linnaeus's work became widely known in England, following its translation from the Latin by the Lichfield Botanical Society as ''A System of Vegetables'' (1783–1785).

''Orbis eruditi judicium de Caroli Linnaei MD scriptis''

('Opinion of the learned world on the writings of Carl Linnaeus, Doctor') Published in 1740, this small octavo-sized pamphlet was presented to the State Library of New South Wales by the Linnean Society of NSW in 2018. This is considered among the rarest of all the writings of Linnaeus, and crucial to his career, securing him his appointment to a professorship of medicine at Uppsala University. From this position he laid the groundwork for his radical new theory of classifying and naming organisms for which he was considered the founder of modern taxonomy.

'

' (or, more fully, ') was first published in 1753, as a two-volume work. Its prime importance is perhaps that it is the primary starting point of plant nomenclature as it exists today.

'

' was first published in 1737, delineating plant genera. Around 10 editions were published, not all of them by Linnaeus himself; the most important is the 1754 fifth edition. In it Linnaeus divided the plant Kingdom into 24 classes. One, Cryptogamia, included all the plants with concealed reproductive parts (algae, fungi, mosses and liverworts and ferns).

'

' (1751) was a summary of Linnaeus's thinking on plant classification and nomenclature, and an elaboration of the work he had previously published in ' (1736) and ' (1737). Other publications forming part of his plan to reform the foundations of botany include his ' and ': all were printed in Holland (as were ' (1737) and ' (1735)), the ''Philosophia'' being simultaneously released in Stockholm.

Collections

At the end of his lifetime the Linnean collection in Uppsala

Uppsala ( ; ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the capital of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inhabitants in 2019.

Loc ...

was considered one of the finest collections of natural history objects in Sweden. Next to his own collection he had also built up a museum for the university of Uppsala, which was supplied by material donated by Carl Gyllenborg

Count Carl Gyllenborg (7 March 1679 – 9 December 1746) was a Swedish statesman and author.

Biography

He was born in Stockholm, the son of Count Jacob Gyllenborg (1648–1701). His father was a Member of Parliament and of the Royal Council, wh ...

(in 1744–1745), crown-prince Adolf Fredrik (in 1745), Erik Petreus (in 1746), Claes Grill (in 1746), Magnus Lagerström (in 1748 and 1750) and Jonas Alströmer (in 1749). The relation between the museum and the private collection was not formalised and the steady flow of material from Linnean pupils were incorporated to the private collection rather than to the museum.[Wallin, L. 2001.](_blank)

Catalogue of type specimens. 4. Linnaean specimens. – pp. 1–128. Uppsala. (Uppsala University, Museum of Evolution, Zoology Section). Linnaeus felt his work was reflecting the harmony of nature and he said in 1754 "the earth is then nothing else but a museum of the all-wise creator's masterpieces, divided into three chambers". He had turned his own estate into a microcosm of that 'world museum'.

In April 1766 parts of the town were destroyed by a fire and the Linnean private collection was subsequently moved to a barn outside the town, and shortly afterwards to a single-room stone building close to his country house at Hammarby near Uppsala. This resulted in a physical separation between the two collections; the museum collection remained in the botanical garden of the university. Some material which needed special care (alcohol specimens) or ample storage space was moved from the private collection to the museum.

In Hammarby the Linnean private collections suffered seriously from damp and the depredations by mice and insects. Carl von Linné's son (Carl Linnaeus) inherited the collections in 1778 and retained them until his own death in 1783. Shortly after Carl von Linné's death his son confirmed that mice had caused "horrible damage" to the plants and that also moths and mould had caused considerable damage.[Dance, S.P. 1967. Report on the Linnaean shell collection. – Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London 178 (1): 1–24, Pl. 1–10.] He tried to rescue them from the neglect they had suffered during his father's later years, and also added further specimens. This last activity however reduced rather than augmented the scientific value of the original material.

In 1784 the young medical student James Edward Smith purchased the entire specimen collection, library, manuscripts, and correspondence of Carl Linnaeus from his widow and daughter and transferred the collections to London. Not all material in Linné's private collection was transported to England. Thirty-three fish specimens preserved in alcohol were not sent and were later lost.

In London Smith tended to neglect the zoological parts of the collection; he added some specimens and also gave some specimens away. Over the following centuries the Linnean collection in London suffered enormously at the hands of scientists who studied the collection, and in the process disturbed the original arrangement and labels, added specimens that did not belong to the original series and withdrew precious original type material.Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

, and is today housed in the Swedish Museum of Natural History at Stockholm. The dry material was transferred to Uppsala.

System of taxonomy

The establishment of universally accepted conventions for the naming of organisms was Linnaeus's main contribution to taxonomy—his work marks the starting point of consistent use of binomial nomenclature.[ Reveal & Pringle (1993), pp. 160–161.] During the 18th century expansion of natural history knowledge, Linnaeus also developed what became known as the ''Linnaean taxonomy''; the system of scientific classification

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

now widely used in the biological sciences

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, origin, evolution, and distribution of ...

. A previous zoologist Rumphius (1627–1702) had more or less approximated the Linnaean system and his material contributed to the later development of the binomial scientific classification by Linnaeus.

The Linnaean system classified nature within a nested hierarchy, starting with three kingdoms. Kingdoms were divided into classes and they, in turn, into orders, and thence into genera (''singular:'' genus), which were divided into species (''singular:'' species). Below the rank of species he sometimes recognised taxa of a lower (unnamed) rank; these have since acquired standardised names such as ''variety'' in botany and ''subspecies'' in zoology. Modern taxonomy includes a rank of family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

between order and genus and a rank of phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

between kingdom and class that were not present in Linnaeus's original system.[ Davis & Heywood (1973), p. 17.]

Linnaeus's groupings were based upon shared physical characteristics, and not based upon differences.DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. The ...

, unavailable in Linnaeus's time, has proven to be a tool of considerable utility for classifying living organisms and establishing their evolutionary relationships), the fundamental principle remains sound.

Human taxonomy

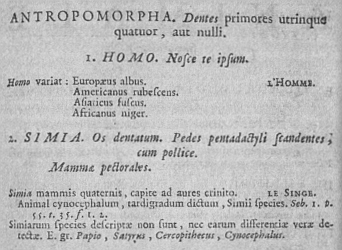

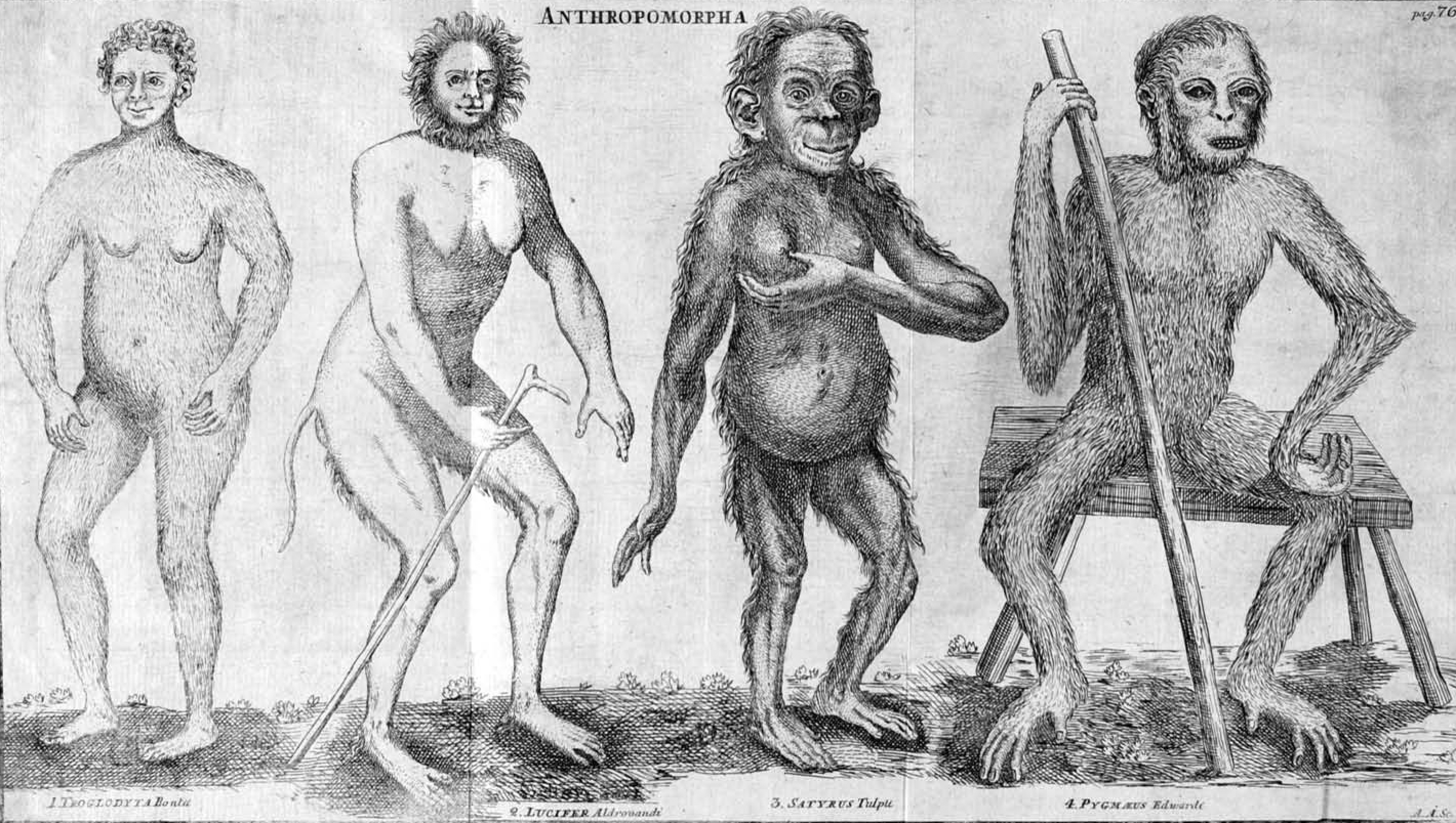

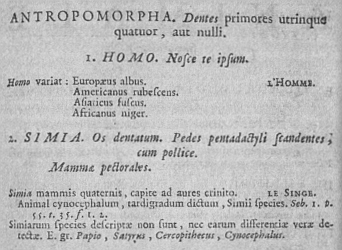

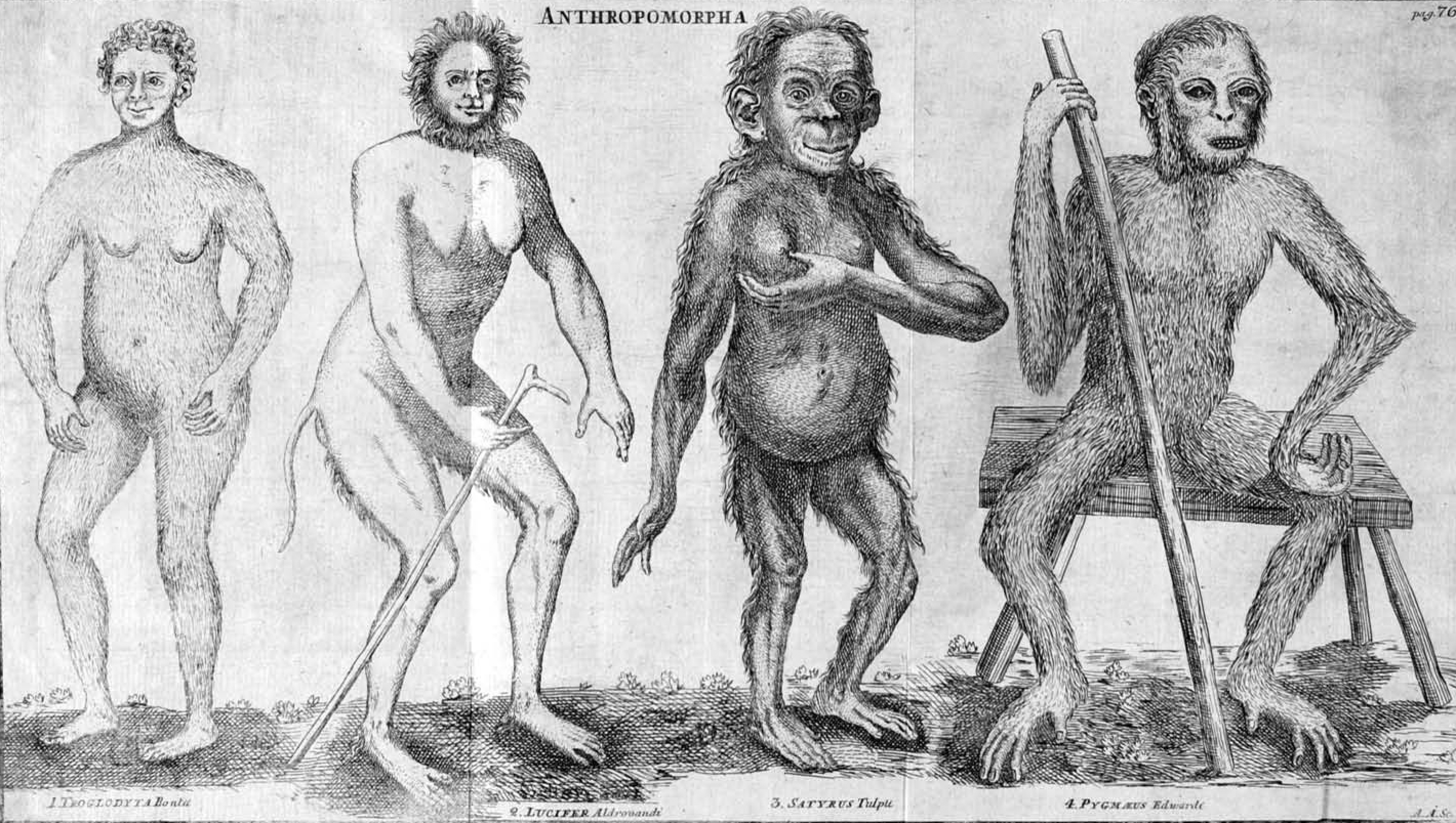

Linnaeus's system of taxonomy was especially noted as the first to include humans (''Homo

''Homo'' () is a genus of great ape (family Hominidae) that emerged from the genus ''Australopithecus'' and encompasses only a single extant species, ''Homo sapiens'' (modern humans), along with a number of extinct species (collectively called ...

'') taxonomically grouped with apes ('' Simia''), under the header of '' Anthropomorpha''.

German biologist Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

speaking in 1907 noted this as the "most important sign of Linnaeus's genius".

Linnaeus classified humans among the primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

s beginning with the first edition of '. During his time at Hartekamp, he had the opportunity to examine several monkey

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes. Thus monkeys, in that sense, co ...

s and noted similarities between them and man. He pointed out both species basically have the same anatomy; except for speech, he found no other differences.[ Frängsmyr ''et al.'' (1983), p. 167, quotes Linnaeus explaining the real difference would necessarily be absent from his classification system, as it was not a morphological characteristic: ''"I well know what a splendidly great difference there is etweena man and a ''bestia'' iterally, "beast"; that is, a non-human animalwhen I look at them from a point of view of ]morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

. Man is the animal which the Creator has seen fit to honor with such a magnificent mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...

and has condescended to adopt as his favorite and for which he has prepared a nobler life"''. See als

books.google.com

in which Linnaeus cites the significant capacity to reason as the distinguishing characteristic of humans. Thus he placed man and monkeys under the same category, ''Anthropomorpha'', meaning "manlike". This classification received criticism from other biologists such as Johan Gottschalk Wallerius, Jacob Theodor Klein and Johann Georg Gmelin on the ground that it is illogical to describe man as human-like. In a letter to Gmelin from 1747, Linnaeus replied:

The theological concerns were twofold: first, putting man at the same level as monkeys or apes would lower the spiritually higher position that man was assumed to have in the

The theological concerns were twofold: first, putting man at the same level as monkeys or apes would lower the spiritually higher position that man was assumed to have in the great chain of being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, Human, humans, Animal, animals and Plant, plants to ...

, and second, because the Bible says man was created in the image of God

The "image of God" (; ; ) is a concept and theological doctrine in Judaism and Christianity. It is a foundational aspect of Judeo-Christian belief with regard to the fundamental understanding of human nature. It stems from the primary text in Gen ...

( theomorphism), if monkeys/apes and humans were not distinctly and separately designed, that would mean monkeys and apes were created in the image of God as well. This was something many could not accept. The conflict between world view

A worldview (also world-view) or is said to be the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and point of view. However, when two parties view the s ...

s that was caused by asserting man was a type of animal would simmer for a century until the much greater, and still ongoing, creation–evolution controversy began in earnest with the publication of ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

in 1859.