Canterbury–York dispute on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Canterbury–York dispute was a long-running conflict between the archdioceses of Canterbury and

The dispute began under Lanfranc, who demanded oaths of obedience from not just the traditional suffragan bishops of Canterbury but also from the archbishop of York.Barlow ''English Church 1066–1154'' p. 33 This happened shortly after Lanfranc's own consecration, when King

The dispute began under Lanfranc, who demanded oaths of obedience from not just the traditional suffragan bishops of Canterbury but also from the archbishop of York.Barlow ''English Church 1066–1154'' p. 33 This happened shortly after Lanfranc's own consecration, when King

During

During

York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

in medieval England

England in the Middle Ages concerns the history of England during the Middle Ages, medieval period, from the end of the 5th century through to the start of the Early modern Britain, early modern period in 1485. When England emerged from the co ...

. It began shortly after the Norman Conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

and dragged on for many years. The main point of the dispute was over whether Canterbury would have jurisdiction, or primacy, over York. A number of archbishops of Canterbury attempted to secure professions of obedience from successive archbishops of York, but in the end they were unsuccessful. York fought the primacy by appealing to the kings of England as well as the papacy. In 1127, the dispute over the primacy was settled mainly in York's favour, for they did not have to submit to Canterbury. Later aspects of the dispute dealt with concerns over status and prestige.

Nature of the dispute

The main locus of the dispute was the attempt by post-Norman Conquest Archbishops of Canterbury to assert their primacy, or right to rule, over theprovince of York

The Province of York, or less formally the Northern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces making up the Church of England and consists of 14 dioceses which cover the northern third of England and the Isle of Man. York was elevated to ...

. Canterbury used texts to back up their claims, including Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

's major historical work the ''Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

The ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' (), written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the growth of Christianity. It was composed in Latin, and ...

'', which sometimes had the Canterbury archbishops claiming primacy over not just York, but the entire ecclesiastical hierarchy of the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

.Barlow ''English Church 1066–1154'' p. 31Bartlett ''England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings'' p. 92 It began under Lanfranc, the first Norman Archbishop of Canterbury, and ended up becoming a neverending dispute between the two sees over prestige and status. The historian David Carpenter says Lanfranc's actions "sucked his successors into a quagmire, and actually weakened rather than strengthened church discipline and the unity of the kingdom."Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 99 Carpenter further argues that "it became impossible in later centuries, thanks to disputes over status, for the two archbishops to appear in each others presence."

Feeding into the dispute were the two cathedral chapter

According to both Catholic and Anglican canon law, a cathedral chapter is a college of clerics ( chapter) formed to advise a bishop and, in the case of a vacancy of the episcopal see in some countries, to govern the diocese during the vacancy. In ...

s, who encouraged their respective archbishops to continue the struggle. An additional element was the fact that Canterbury had a monastic chapter, while York had secular clergy

In Christianity, the term secular clergy refers to deacons and priests who are not monastics or otherwise members of religious life. Secular priests (sometimes known as diocesan priests) are priests who commit themselves to a certain geograph ...

in the form of canons, interjecting a note of secular and monastic clerical rivalries into the dispute. Another problem that intertwined with the dispute was the investiture controversy

The Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest (, , ) was a conflict between church and state in medieval Europe, the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture), abbots of monasteri ...

in England, which was concurrent with the dispute and involved most of the same protagonists. The kings of England, who might have forced a decision, were more concerned with other matters, and were ambivalent about Canterbury's claims, which removed a potential way to resolve the dispute. At times, kings supported Canterbury's claims in order to keep the north of England from revolting, but this was balanced by the times that the kings were in quarrels with Canterbury.

The popes, who were often called upon to decide the issue, had their own concerns with granting a primacy, and did not wish to actually rule in Canterbury's favour. But the main driving forces behind the Canterbury position were Lanfranc and Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also known as (, ) after his birthplace and () after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher, and theologian of the Catholic Church, who served as Archbishop of Canterb ...

, both of whom enjoyed immense prestige in the church and thus it was not easy for the papacy to rule against them or their position. Once Anselm was out of office, however, the popes began to side more often with York, and generally strived to avoid making any final judgement.

Under the Norman kings

Under Lanfranc

The dispute began under Lanfranc, who demanded oaths of obedience from not just the traditional suffragan bishops of Canterbury but also from the archbishop of York.Barlow ''English Church 1066–1154'' p. 33 This happened shortly after Lanfranc's own consecration, when King

The dispute began under Lanfranc, who demanded oaths of obedience from not just the traditional suffragan bishops of Canterbury but also from the archbishop of York.Barlow ''English Church 1066–1154'' p. 33 This happened shortly after Lanfranc's own consecration, when King William I of England

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was ...

then proposed that Lanfranc consecrate the new archbishop of York, Thomas of Bayeux. Lanfranc demanded that Thomas swear to obey Lanfranc as Thomas' primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

before the consecration could take place, and Thomas refused, but he eventually gave way, and made a profession. However, the exact form that this oath took was disputed, with Canterbury claiming it was without conditions, and York claiming that it was only a personal submission to Lanfranc, and did not involve the actual offices of Canterbury and York. When both Thomas and Lanfranc visited Rome in 1071, Thomas brought up the primacy issue again, and for good measure tacked on a claim to three of Canterbury's suffragan dioceses, Lichfield

Lichfield () is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated south-east of the county town of Stafford, north-east of Walsall, north-west of ...

, Dorchester, and Worcester. Pope Alexander II

Pope Alexander II (1010/1015 – 21 April 1073), born Anselm of Baggio, was the head of the Roman Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1061 to his death in 1073. Born in Milan, Anselm was deeply involved in the Pataria reform mo ...

sent the issue back to England, to be settled at a council convened by the papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

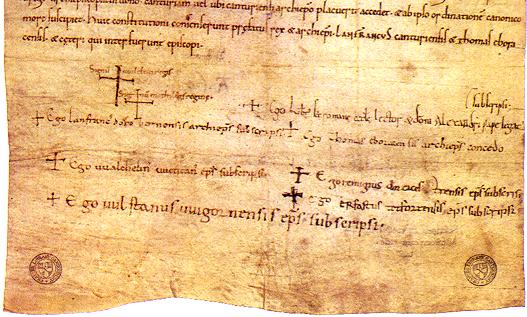

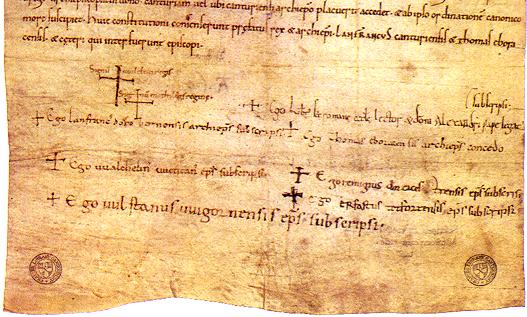

. This council took place at Winchester in April 1072, and Lanfranc was victorious on both the primacy issue as well as the dioceses.Blumenthal ''Investiture Controversy'' p. 151 The victory was drawn up in the Accord of Winchester, to which those present affixed their names.Stenton ''Anglo-Saxon England'' pp. 664–665 However, papal confirmation of the decision did not extend to Lanfranc's successors,Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 169–170 and in fact was never a complete confirmation of the rulings of the council.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 321–323 Lanfranc enjoyed the support of King William I at this council.Barlow ''English Church 1066–1154'' p. 61 Thomas was compensated with authority over the Scottish bishops, which was an attempt to give York enough suffragans to allow the archbishops of York to be consecrated without the help of Canterbury. An archiepiscopal consecration required three bishops, and after York's claims to Lichfield, Dorchester, and Worcester were denied, York only had one suffragan, the Diocese of Durham

The diocese of Durham is a diocese of the Church of England in North East England. The boundaries of the diocese are the historic boundaries of County Durham, meaning it includes the part of Tyne and Wear south of the River Tyne and contemporary ...

.Brett ''English Church'' p. 15

Why exactly Lanfranc decided to press forward claims to a judicial primacy over York is unclear. Some historians, including Frank Barlow have speculated that it was because Thomas was a disciple of Odo of Bayeux

Odo of Bayeux (died 1097) was a Norman nobleman who was a bishop of Bayeux in Normandy and was made Earl of Kent in England following the Norman Conquest. He was the maternal half-brother of duke, and later king, William the Conqueror, and w ...

, one of Lanfranc's rivals in the English church. Another possibility was that Lanfranc desired to assert authority over the northern province of Britain in order to aid the reforming efforts Lanfranc was attempting. Lanfranc was surely influenced by his cathedral chapter at Canterbury, who may have desired to recover their honours after the problems encountered in Lanfranc's predecessor Stigand's archiepiscopate. York had never had a primacy, and based its arguments on the general principle that primacies were erroneous. While Canterbury in the Anglo-Saxon era had been more prestigious than York, it had never in fact had a judicial primacy. Another influence was probably Lanfranc's monastic background, with Lanfranc feeling that the ecclesiastical structure should mirror the monastic absolute obedience to a superior. However, a main influence was probably the so-called ''False Decretals

Pseudo-Isidore is the conventional name for the unknown Carolingian Empire, Carolingian-era author (or authors) behind an extensive corpus of influential forgery, forgeries. Pseudo-Isidore's main object was to provide accused bishops with an arra ...

'', a collection of decrees and canons from the ninth century, which mentioned primates as the equivalent of patriarchs and placed them between the pope and the metropolitan bishops in the hierarchy.Delivré "Foundations of Primatial Claims" ''Journal of Ecclesiastical History'' pp. 384–386

When Lanfranc attempted to find documentary proof to rebut York's refusal, it was discovered that no explicit statement of such a primacy existed. This involved the use of letters of Pope Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory I (; ; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great (; ), was the 64th Bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 until his death on 12 March 604. He is known for instituting the first recorded large-scale mission from Rom ...

, which were repeated in Bede's ''Historia'', but a complication was that Gregory's plan for the Gregorian mission

The Gregorian missionJones "Gregorian Mission" ''Speculum'' p. 335 or Augustinian missionMcGowan "Introduction to the Corpus" ''Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature'' p. 17 was a Christian mission sent by Pope Pope Gregory I, Gregory the Great ...

had specified that the southern province would be based at London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, not Canterbury. There was documentary evidence from the papacy that stated that Canterbury had a primacy over the island, but these dated from before York had been raised to an archbishopric. During the Council of Winchester in 1072, papal letters were produced which may or may not have been forgeries. A biographer of Lanfranc, Margaret Gibson, argues that they already existed before Lanfranc used them. Another historian, Richard Southern, holds that the statements relating to primacy were inserted into legitimate papal letters after Lanfranc's day. Most historians agree that Lanfranc did not have anything to do with the forgeries, however they came about.

King William I supported Lanfranc in this dispute, probably because he felt that it was important that his kingdom be represented by one ecclesiastical province, and this would best be accomplished by supporting the primacy of Canterbury. Before conquering England, William had ruled the duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between Charles the Simple, King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a r ...

, which corresponded to the archdiocese of Rouen

The Archdiocese of Rouen (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Rothomagensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Rouen'') is a Latin Church archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. As one of the fifteen Archbishops of France, the Archbishop of Rouen's ecclesi ...

, and the simplicity of control which this allowed the dukes of Normandy probably was a strong factor in William's support of Canterbury's claims. Another concern was that in 1070–1072, the north of England, where York was located, was still imperfectly pacified, and allowing York independence might lead to York crowning another king.

Thomas claimed that when Lanfranc died in 1089, Thomas' profession lapsed, and during the long vacancy at Canterbury that followed on Lanfranc's death, Thomas performed most of the archiepiscopal functions in England.Barlow ''English Church 1066–1154'' pp. 39–42

Under Anselm

When Anselm was appointed to Canterbury, after a long vacancy that lasted from 1089 to 1093, the only flareup of the dispute was a dispute at Anselm's consecration on 4 December 1093 over the exact title that would be employed in the ceremony. The dispute centered on the title that would be confirmed on Anselm, and although it was settled quickly, the exact title used is unknown, as the two main sources of information differ. Eadmer, Anselm's biographer and a Canterbury partisan, proclaims that the title agreed upon was "Primate of all Britain".Hugh the Chanter

Hugh Sottovagina (died c. 1140), often referred to as Hugh the Chanter or Hugh the Chantor, was a historian for York Minster during the 12th century and was probably an archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the E ...

, a chronicler from York and a partisan of York, claims the title used was "Metropolitan of Canterbury".Vaughn ''Anselm of Bec'' p. 148 Until the ascension of King Henry I in 1100, Anselm was much more occupied with other disputes with King William II.Barlow ''William Rufus'' p. 308

It was during Anselm's archiepiscopate that the primacy dispute became central to Anselm's plans. Eadmer made the dispute central to his work, the ''Historia Novorum''. Likewise, Hugh the Chanter, made the primacy dispute one of the central themes of his work ''History of the Church of York''.Hollister ''Henry I'' pp. 13–14

In 1102, Pope Paschal II

Pope Paschal II (; 1050 1055 – 21 January 1118), born Raniero Raineri di Bleda, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 August 1099 to his death in 1118. A monk of the Abbey of Cluny, he was creat ...

, in the midst of the Investiture controversy, tried to smooth over the problems about investiture

Investiture (from the Latin preposition ''in'' and verb ''vestire'', "dress" from ''vestis'' "robe") is a formal installation or ceremony that a person undergoes, often related to membership in Christian religious institutes as well as Christian kn ...

by granting Anselm a primacy, but only to Anselm himself, not to his successors. Nor did the grant explicitly mention York as being subject to Canterbury.Vaughn ''Anselm of Bec'' p. 242 Anselm then held a council in September 1102 at Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, which was attended by Gerard

Gerard is a masculine forename of Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic origin, variations of which exist in many Germanic and Romance languages. Like many other Germanic name, early Germanic names, it is dithematic, consisting of two meaningful ...

, the new archbishop of York. According to Hugh the Chanter, when the seats for the bishops were arranged, Anselm's was set higher than Gerard's, which led Gerard to kick over chairs and refuse to be seated until his own chair was exactly as high as Anselm's.Vaughn ''Anselm of Bec'' pp. 246–247 Late in 1102, the pope wrote to Gerard, admonishing him and ordering him to make the oath to Anselm.Vaughn ''Anselm of Bec'' pp. 255–256

Gerard died in May 1108, and his successor was nominated within six days. Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, however, delayed going to Canterbury to be consecrated, under pressure from his cathedral chapter and knowing that since Anselm was in poor health, he might be able to outlast Anselm. Thomas told Anselm that his cathedral chapter had forbidden him to make any oath of obedience, and this was confirmed by the canons themselves, who wrote to Anselm confirming Thomas' account. Although Anselm died before Thomas' had submitted, one of the last letters Anselm wrote ordered Thomas not to seek consecration until he had made the required profession. After Anselm's death, the king then pressured Thomas to submit a written profession, which he eventually did. The actual document has disappeared, and as always, Eadmer and Hugh the Chanter disagree on the exact wording, with Eadmer claiming it was made to Canterbury and any successor archbishops, and Hugh claiming that Thomas qualified the oath by making it clear that it could not impede the rights of the Church of York.Vaughn ''Anselm of Bec'' pp. 334–349

Dispute under Thurstan

During the archbishopric of Thurstan, theArchbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

between 1114 and 1140, the dispute flared up and Thurstan appealed to the papacy over the issue, with Canterbury under Ralph d'Escures

Ralph d'Escures (also known as RadulfEadmer. ''Eadmer’s History of Recent Events in England = Historia Novorum in Anglia''. Translated by Geoffrey Bosanquet. London: Cresset Press, 1964.) (died 20 October 1122) was a medieval abbot of Séez ...

countering with information from Bede as well as forged documents. The papacy did not necessarily believe the forgeries, but the dispute rumbled on for a number of years.Loyn ''English Church'' p. 110 Shortly after Thurstan's election in 1114, Ralph refused to consecrate Thurstan unless Ralph received a written, not just oral, profession of obedience.Hollister ''Henry I'' p. 235 Thurstan refused to do so, and assured his cathedral chapter that he would not submit to Canterbury. York based its claim on the fact that no metropolitan bishop or archbishop could swear allegiance to anyone but the pope, a position guaranteed to gain support from the papacy. King Henry, however, refused permission for Thurstan to appeal to the papacy, which left the dispute in limbo for two years. Henry does not seem to have cared about who won the dispute, and Henry may have delayed hoping that Ralph and Thurstan would reach a compromise which would keep Henry from having to alienate either of them.

Pressure mounted, however, and Henry called a council in the spring of 1116, and Henry ordered that when Thurstan arrived at the council, he must swear to obey Canterbury. If Thurstan would not do so, Henry threatened to depose him from office. But, on his way to the council, Thurstan received a letter from the pope, ordering Thurstan's consecration without any profession. Although Thurstan did not reveal that the pope had ordered his consecration, he continued to refuse to make a profession, and resigned his see in the presence of the king and the council. But, the papacy, the York cathedral chapter, and even King Henry still considered Thurstan the archbishop-elect. In 1117, Ralph attempted to visit Pope Paschal II about the dispute, but was unable to actually meet the pope, and only secured a vague letter confirming Canterbury's past privileges, but since the exact privileges weren't specified, the letter was useless.Hollister ''Henry I'' pp. 241–244

Both Ralph and Thurstan attended the Council of Reims in 1119, convened by Pope Calixtus II in October. Although Canterbury sources state that Thurstan promised King Henry he would refuse consecration while at the council, Yorkish sources deny that any such promise was made. Calixtus promptly consecrated Thurstan at the start of the council, which angered Henry and led the king to exile Thurstan from England and Normandy. Although the pope and king met and negotiated Thurstan's status in November 1119, nothing came of this, and Calixtus in March 1120 gave Thurstan two papal bulls, one an exemption for York from Canterbury's claims, titled ''Caritatis Bonun'',Cheney "Some Observations" ''Journal of Ecclesiastical History'' p. 429 and the other a threat of interdict on England if Thurstan was not allowed to return to York. After some diplomatic efforts, Thurstan was allowed back into the king's favour and his office returned to him.Hollister ''Henry I'' pp. 269–273 Calixtus' bulls also allowed any future Archbishops of York to be consecrated by their suffragans if the Archbishop of Canterbury refused.Delivré "Foundations of Primatial Claims" ''Journal of Ecclesiastical History'' pp. 387–388

In 1123, William of Corbeil, recently elected Archbishop of Canterbury, refused consecration by Thurstan unless Thurstan would incorporate into the ceremony an admission that Canterbury was primate of Britain. When Thurstan refused, William was consecrated by three of his own bishops.Hollister ''Henry I'' pp. 288–289 William then traveled to Rome to secure confirmation of his election, which was disputed. Thurstan also traveled to Rome, as both archbishops had been summoned to attend a papal council, which both arrived too late to attend. Thurstan arrived shortly before William. While there, William and his advisors presented documents to the papal curia which they insisted proved Canterbury's primacy. However, the cardinals and the curia found the documents to be forgeries.Robinson ''Papacy'' pp. 103–104 What persuaded the cardinals was the absence of papal bulls from the nine documents produced, which the Canterbury delegation tried to explain away by saying the bulls had "wasted away or were lost". Hugh the Chanter, a medieval chronicler of York, stated that when the cardinals heard that explanation, they laughed and ridiculed the documents "saying how miraculous it was that lead should waste away or be lost and parchment should survive".Quoted in Robinson ''Papacy'' p. 189 Hugh goes on to record that the attempts by the Canterbury party to secure their objective by bribery likewise failed.Robinson ''Papacy'' p. 263

Pope Honorius II made a judgment in York's favour in 1126, having found the documents and case presented by Canterbury to be unconvincing.Duggan "From the Conquest to the Death of John" ''English Church and the Papacy'' pp. 98–99 In the winter of 1126–1127, an attempt at compromise was made, with Canterbury agreeing to give jurisdiction over the sees of Chester, Bangor and St Asaph to York in return for the submission of York to Canterbury. This foundered when William of Corbeil arrived at Rome and told the pope that he had not agreed to the surrender of St Asaph. This was the last attempt by William to secure an oath from Thurstan,Brett ''English Church'' pp. 46–47 for a compromise in the primacy dispute was made, with William of Corbeil receiving a papal legateship, which effectively gave him the powers of the primacy without the papacy actually having to concede a primacy to Canterbury.Barlow ''English Church 1066–1154'' p. 44 This legateship covered not only England, but Scotland as well.Robinson ''Papacy'' pp. 173–174

A small flare-up in 1127 happened when William of Corbeil objected to Thurstan having his episcopal cross carried in processions in front of Thurstan while Thurstan was in Canterbury's province. William also objected to Thurstan participating in the ceremonial crownings of the king at the royal court. Thurstan appealed to Rome, and Honorius wrote a scathing letter to William declaring that if the reports from Thurstan were true, William would be punished for his actions. Thurstan then traveled to Rome, where he secured new rulings from the papacy. One gave the seniority between the two British archbishops to whichever had been consecrated first. Another ruling allowed the Archbishops of York to have their crosses carried in Canterbury's province.Bethell "William of Corbeil" ''Journal of Ecclesiastical History'' pp. 156–157

Legacy of the first dispute

The main import of the first dispute was the increase in appeals to the papacy to solve the problem. This was part of a general trend to seek support and resolution at the papacy instead of in the royal courts, a trend that grew through the reigns of William II and Henry I.Brett ''English Church'' p. 50 Also important was the impetus that the disputes gave to efforts by both York and Canterbury to assert their jurisdiction over Scotland, Wales and Ireland.Brett ''English Church'' p. 52 After the settlement of the profession issue, the dispute turned to other, lesser matters such as how the respective chairs of the two archbishops would be arranged when they were together and the right of either to carry their episcopal cross in the others' province.Under Stephen

Under Stephen, the dispute arose briefly at the Council of Reims of 1148.Theobald of Bec

Theobald of Bec ( c. 1090 – 18 April 1161) was a Norman archbishop of Canterbury from 1139 to 1161. His exact birth date is unknown. Some time in the late 11th or early 12th century Theobald became a monk at the Abbey of Bec, r ...

, who was Archbishop of Canterbury for most of Stephen's reign, attended the council, and when Henry Murdac, just recently elected to York, did not arrive, Theobald claimed the primacy over York at one of the early council sessions. However, as Murdac was a Cistercian, as was Pope Eugene III, who had called the council, nothing further was done about Canterbury's claim. Eugene postponed any decision until Murdac was established in his see.Saltman ''Theobald'' pp. 141–142

Most of the time, however, Theobald was not concerned with reopening the dispute, as demonstrated when he consecrated Roger de Pont L'Evêque, newly elected to York in 1154. Theobald, at Roger's request, performed the consecration as papal legate, and not as archbishop, thus side-stepping the question of a profession of obedience.Saltman ''Theobald'' p. 123

Disputes under Henry II

Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then as Archbishop of Canterbury fr ...

's archiepiscopate, the dispute flared up again, with the added complication of an attempt by Gilbert Foliot

Gilbert Foliot (Wiktionary:circa, c. 1110 – 18 February 1187) was a medieval English monk and prelate, successively Abbot of Gloucester, Bishop of Hereford and Bishop of London. Born to an ecclesiastical family, he became a monk at C ...

, the Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

, to have his see raised to an archbishopric, basing his case on the old Gregorian plan for London to be the seat of the southern province. Foliot was an opponent of Becket's, and this fed into the dispute, as well as Becket's legateships, which specifically excluded York. When Roger de Pont L'Evêque, the Archbishop of York, crowned Henry the Young King

Henry the Young King (28 February 1155 – 11 June 1183) was the eldest son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine to survive childhood. In 1170, he became titular King of England, Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and Maine. Henry th ...

in 1170, this was a furthering of the dispute, as it was Canterbury's privilege to crown the kings of England.

The first sign of the revival of the dispute was at the Council of Tours, called in 1163 by Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a Papal election, ...

. While there, Roger and Becket disputed over the placement of their seats in the council. Roger argued, that based on Gregory the Great's plan that primacy should go to the archbishop who had been consecrated first, he had the right to the more honourable placement at the council. Eventually, Alexander placed them both on equal terms,Barlow ''Thomas Becket'' pp. 84–86 but not before the council spent three days listening to the claims and counter-claims, as well as Roger relating the whole history of the dispute.Bartlett ''England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings'' p. 394 In 1164 Alexander gave Roger a papal legateship, but excluded Becket from its jurisdiction. The pope did, however, decline to declare that Canterbury had a primacy in England.Barlow ''Thomas Becket'' p. 106 Alexander on 8 April 1166 confirmed Canterbury's primacy, but this became less important than the grant of a legateship on 24 April to Becket. This grant, though, did not cover the diocese of York, which was specifically prohibited.Barlow ''Thomas Becket'' p. 145

During the reign of Henry II, the dispute took a new form, concerning the right of either archbishop to carry their archiepiscopal cross throughout the kingdom, not just in their own province. During the vacancy between the death of Theobald of Bec and the appointment of Becket, Roger had secured papal permission to carry his cross anywhere in England. As the Becket controversy

The Becket controversy or Becket dispute was the quarrel between Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket and King Henry II of England from 1163 to 1170.Bartlett ''England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings'' pp. 401–402 The controversy culminated ...

grew, however, Alexander asked Roger to forbear from doing so, in order to stop the wrangling that had arisen from Roger's doing so. Later, Alexander revoked the privilege, claiming it had been given in error.Warren ''Henry II'' p. 503

Disputes under Richard I

The dispute continued betweenHubert Walter

Hubert Walter ( – 13 July 1205) was an influential royal adviser in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries in the positions of Chief Justiciar of England, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor. As chancellor, Walter be ...

and Geoffrey, respectively Archbishop of Canterbury and Archbishop of York, during the reign of Richard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199), known as Richard the Lionheart or Richard Cœur de Lion () because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior, was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ru ...

, when both archbishops had their archiepiscopal crosses carried before themselves in the others diocese, prompting angry recriminations. Eventually, both prelates attempted to secure a settlement from Richard in their favour, but Richard declined, stating that this was an issue that needed to be settled by the papacy. However, no firm settlement was made until the 14th century.Young ''Hubert Walter'' pp. 88–89

Role of the papacy

The papacy, while continuing to grant legateships to the archbishops of Canterbury, began after 1162 to specifically exclude the legateships from covering the province of York. The only exception from the later half of the 12th century was the legateship of Hubert Walter in 1195, which covered all of England. This exception, however, was more due toPope Celestine III

Pope Celestine III (; c. 1105 – 8 January 1198), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 March or 10 April 1191 to his death in 1198. He had a tense relationship with several monarchs, including Emperor ...

's dislike of Geoffrey, the archbishop of York at the time.

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Canterbury-York dispute 11th-century Catholicism 12th-century Catholicism 11th century in England 12th century in England Christianity in medieval England Thomas Becket Diocese of Canterbury Diocese of York Henry the Young King Richard I of England