Caenorhabditis elegans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent

''C.elegans'' is unsegmented,

''C.elegans'' is unsegmented,

In relation to lipid metabolism, ''C.elegans'' does not have any specialized adipose tissues, a

In relation to lipid metabolism, ''C.elegans'' does not have any specialized adipose tissues, a  There are 302 neurons in ''C.elegans,'' approximately one-third of all the somatic cells in the whole body. Many neurons contain dendrites which extend from the cell to receive neurotransmitters or other signals, and a

There are 302 neurons in ''C.elegans,'' approximately one-third of all the somatic cells in the whole body. Many neurons contain dendrites which extend from the cell to receive neurotransmitters or other signals, and a

The sperm of ''C. elegans'' is amoeboid, lacking

The sperm of ''C. elegans'' is amoeboid, lacking

Under environmental conditions favourable for

Under environmental conditions favourable for

''C. elegans'' can also use different species of

Nematodes can survive

''C. elegans'', as other nematodes, can be eaten by predator nematodes and other omnivores, including some insects. The Orsay virus is a virus that affects ''C. elegans'', as well as the Caenorhabditis elegans Cer1 virus and the Caenorhabditis elegans Cer13 virus. ; Interactions with fungi Wild isolates of ''Caenorhabditis elegans'' are regularly found with infections by

''C. elegans'' was the first multicellular organism to have its whole genome sequenced. The sequence was published in 1998, although some small gaps were present; the last gap was finished by October 2002. In the run up to the whole genome the ''C. elegans'' Sequencing Consortium/''C. elegans'' Genome Project released several partial scans including Wilson et al. 1994.

''C. elegans'' was the first multicellular organism to have its whole genome sequenced. The sequence was published in 1998, although some small gaps were present; the last gap was finished by October 2002. In the run up to the whole genome the ''C. elegans'' Sequencing Consortium/''C. elegans'' Genome Project released several partial scans including Wilson et al. 1994.

As of 2014, ''C. elegans'' is the most basal species in the 'Elegans' group (10 species) of the 'Elegans' supergroup (17 species) in phylogenetic studies. It forms a branch of its own distinct to any other species of the group.

Tc1 transposon is a DNA transposon active in ''C. elegans''.

As of 2014, ''C. elegans'' is the most basal species in the 'Elegans' group (10 species) of the 'Elegans' supergroup (17 species) in phylogenetic studies. It forms a branch of its own distinct to any other species of the group.

Tc1 transposon is a DNA transposon active in ''C. elegans''.

WormBase

– an extensive online database covering the biology and genomics of ''C. elegans'' and other nematodes

WormAtlas

– online database on all aspects of ''C. elegans'' anatomy with detailed explanations and high-quality images

WormBook

– online review of ''C. elegans'' biology

– another genome database for ''C. elegans'', maintained at the NCBI

''C. elegans'' II

– a free online textbook.

WormWeb Neural Network

– an online tool for visualizing and navigating the connectome of ''C. elegans''

– a visual introduction to ''C. elegans'' *

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' at eppo.int

( EPPO code CAEOEL) * {{Authority control Nematodes described in 1900 Articles containing video clips Animal models in neuroscience

nematode

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (h ...

about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of its genus. The name is a blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''rhabditis'' (rod-like) and Latin ''elegans'' (elegant). In 1900, Maupas initially named it '' Rhabditides elegans.'' Osche placed it in the subgenus

In biology, a subgenus ( subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the ge ...

''Caenorhabditis'' in 1952, and in 1955, Dougherty raised ''Caenorhabditis'' to the status of genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

.

''C. elegans'' is an unsegmented pseudocoelomate and lacks respiratory or circulatory systems. Most of these nematodes are hermaphrodite

A hermaphrodite () is a sexually reproducing organism that produces both male and female gametes. Animal species in which individuals are either male or female are gonochoric, which is the opposite of hermaphroditic.

The individuals of many ...

s and a few are males. Males have specialised tails for mating that include spicules.

In 1963, Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner (13 January 1927 – 5 April 2019) was a South African biologist. In 2002, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with H. Robert Horvitz and Sir John E. Sulston. Brenner made significant contributions to wo ...

proposed research into ''C. elegans,'' primarily in the area of neuronal development. In 1974, he began research into the molecular and developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of Regeneration (biology), regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and di ...

of ''C. elegans'', which has since been extensively used as a model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

. It was the first multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell (biology), cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, Embryophyte, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organism ...

to have its whole genome sequenced, and in 2019 it was the first organism to have its connectome

A connectome () is a comprehensive map of neural connections in the brain, and may be thought of as its " wiring diagram". These maps are available in varying levels of detail. A functional connectome shows connections between various brain ...

(neuronal "wiring diagram") completed.

four Nobel prizes have been won for work done on ''C. elegans.''

Anatomy

''C.elegans'' is unsegmented,

''C.elegans'' is unsegmented, vermiform

Vermes (" vermin/vermes") is an obsolete taxon used by Carl Linnaeus and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck for non-arthropod invertebrate animals.

Linnaeus

In Linnaeus's ''Systema Naturae'', the Vermes had the rank of class, occupying the 6th (and last) ...

, and bilaterally symmetrical. It has a cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

(a strong outer covering, as an exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

), four main epidermal cords, and a fluid-filled pseudocoelom (body cavity). It also has some of the same organ systems as larger animals. About one in a thousand individuals is male and the rest are hermaphrodites. The basic anatomy of ''C.elegans'' includes a mouth, pharynx

The pharynx (: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the human mouth, mouth and nasal cavity, and above the esophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs respectively). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates ...

, intestine, gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a Heterocrine gland, mixed gland and sex organ that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gon ...

, and collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

ous cuticle. Like all nematodes, they have neither a circulatory nor a respiratory system. The four bands of muscles that run the length of the body are connected to a neural system that allows the muscles to move the animal's body only as dorsal bending or ventral bending, but not left or right, except for the head, where the four muscle quadrants are wired independently from one another. When a wave of dorsal/ventral muscle contractions proceeds from the back to the front of the animal, the animal is propelled backwards. When a wave of contractions is initiated at the front and proceeds posteriorly along the body, the animal is propelled forwards. Because of this dorsal/ventral bias in body bends, any normal living, moving individual tends to lie on either its left side or its right side when observed crossing a horizontal surface. A set of ridges on the lateral sides of the body cuticle, the alae, is believed to give the animal added traction during these bending motions.

pancreas

The pancreas (plural pancreases, or pancreata) is an Organ (anatomy), organ of the Digestion, digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdominal cavity, abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a ...

, a liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

, or even blood to deliver nutrients compared to mammals. Neutral lipids are instead stored in the intestine, epidermis, and embryos. The epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

corresponds to the mammalian adipocytes by being the main triglyceride

A triglyceride (from '' tri-'' and '' glyceride''; also TG, triacylglycerol, TAG, or triacylglyceride) is an ester derived from glycerol and three fatty acids.

Triglycerides are the main constituents of body fat in humans and other vertebrates ...

depot.

The pharynx is a muscular food pump in the head of ''C.elegans'', which is triangular in cross-section. This grinds food and transports it directly to the intestine. A set of "valve cells" connects the pharynx to the intestine, but how this valve operates is not understood. After digestion, the contents of the intestine are released via the rectum, as is the case with all other nematodes. No direct connection exists between the pharynx and the excretory canal, which functions in the release of liquid urine.

Males have a single-lobed gonad, a vas deferens

The vas deferens (: vasa deferentia), ductus deferens (: ductūs deferentes), or sperm duct is part of the male reproductive system of many vertebrates. In mammals, spermatozoa are produced in the seminiferous tubules and flow into the epididyma ...

, and a tail specialized for mating, which incorporates spicules. Hermaphrodites have two ovaries

The ovary () is a gonad in the female reproductive system that produces ova; when released, an ovum travels through the fallopian tube/oviduct into the uterus. There is an ovary on the left and the right side of the body. The ovaries are endocr ...

, oviducts, and spermatheca

The spermatheca (pronounced : spermathecae ), also called ''receptaculum seminis'' (: ''receptacula seminis''), is an organ of the female reproductive tract in insects, e.g. ants, bees, some molluscs, Oligochaeta worms and certain other in ...

, and a single uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', : uteri or uteruses) or womb () is the hollow organ, organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans, that accommodates the embryonic development, embryonic and prenatal development, f ...

.

process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

* Business process, activities that produce a specific s ...

that extends to the nerve ring (the "brain") for a synaptic connection with other neurons. ''C.elegans'' has excitatory cholinergic and inhibitory GABAergic motor neurons which connect with body wall muscles to regulate movement. In addition, these neurons and other neurons such as interneurons use a variety of neurotransmitters to control behaviors.

Gut granules

Numerous gut granules are present in the intestine of ''C.elegans'', the functions of which are still not fully known, as are many other aspects of this nematode, despite the many years that it has been studied. These gut granules are found in all of the Rhabditida orders. They are very similar to lysosomes in that they feature an acidic interior and the capacity forendocytosis

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which Chemical substance, substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a Vesicle (biology and chem ...

, but they are considerably larger, reinforcing the view of their being storage organelles.

A particular feature of the granules is that when they are observed under ultraviolet light, they react by emitting an intense blue fluorescence

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of photoluminescence, the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with colore ...

. Another phenomenon seen is termed 'death fluorescence'. As the worms die, a dramatic burst of blue fluorescence is emitted. This death fluorescence typically takes place in an anterior to posterior wave that moves along the intestine, and is seen in both young and old worms, whether subjected to lethal injury or peacefully dying of old age.

Many theories have been posited on the functions of the gut granules, with earlier ones being eliminated by later findings. They are thought to store zinc as one of their functions. Recent chemical analysis has identified the blue fluorescent material they contain as a glycosylated form of anthranilic acid (AA). The need for the large amounts of AA the many gut granules contain is questioned. One possibility is that the AA is antibacterial and used in defense against invading pathogens. Another possibility is that the granules provide photoprotection; the bursts of AA fluorescence entail the conversion of damaging UV light to relatively harmless visible light. This is seen as a possible link to the melanin–containing melanosomes.

Reproduction

The hermaphroditic worm is considered to be a specialized form of self-fertile female, as its soma is female. The hermaphroditic germline produces male gametes first, and lays eggs through its uterus after internal fertilization. Hermaphrodites produce all theirsperm

Sperm (: sperm or sperms) is the male reproductive Cell (biology), cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm ...

in the L4 stage (150 sperm cells per gonadal arm) and then produce only oocytes. The hermaphroditic gonad acts as an ovotestis with sperm cells being stored in the same area of the gonad as the oocytes until the first oocyte pushes the sperm into the spermatheca

The spermatheca (pronounced : spermathecae ), also called ''receptaculum seminis'' (: ''receptacula seminis''), is an organ of the female reproductive tract in insects, e.g. ants, bees, some molluscs, Oligochaeta worms and certain other in ...

(a chamber wherein the oocytes become fertilized by the sperm).

The male can inseminate the hermaphrodite, which will preferentially use male sperm (both types of sperm are stored in the spermatheca).

The sperm of ''C. elegans'' is amoeboid, lacking

The sperm of ''C. elegans'' is amoeboid, lacking flagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

and acrosomes. When self-inseminated, the wild-type worm lays about 300 eggs. When inseminated by a male, the number of progeny can exceed 1,000. Hermaphrodites do not typically mate with other hermaphrodites. At 20 °C, the laboratory strain of ''C. elegans'' (N2) has an average lifespan around 2–3 weeks and a generation time of 3 to 4 days.

''C. elegans'' has five pairs of autosome

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosomes ...

s and one pair of sex chromosome

Sex chromosomes (also referred to as allosomes, heterotypical chromosome, gonosomes, heterochromosomes, or idiochromosomes) are chromosomes that

carry the genes that determine the sex of an individual. The human sex chromosomes are a typical pair ...

s. Sex in ''C. elegans'' is based on an X0 sex-determination system. Hermaphrodites of ''C. elegans'' have a matched pair of sex chromosomes (XX); the rare males have only one sex chromosome (X0).

Sex determination

''C. elegans'' are mostly hermaphroditic organisms, producing both sperms and oocytes. Males do occur in the population in a rate of approximately 1 in 200 hermaphrodites, but the two sexes are highly differentiated. Males differ from their hermaphroditic counterparts in that they are smaller and can be identified through the shape of their tail. ''C.elegans'' reproduce through a process called androdioecy. This means that they can reproduce in two ways: either through self-fertilization in hermaphrodites or through hermaphrodites breeding with males. Males are produced through non-disjunction of the X chromosomes during meiosis. The worms that reproduce through self-fertilization are at risk for high linkage disequilibrium, which leads to lower genetic diversity in populations and an increase in accumulation of deleterious alleles. In ''C. elegans'', somatic sex determination is attributed to the '' tra-1'' gene. The ''tra-1'' is a gene within the TRA-1 transcription factor sex determination pathway that is regulated post-transcriptionally and works by promoting female development. In hermaphrodites (XX), there are high levels of ''tra-1'' activity, which produces the female reproductive system and inhibits male development. At a certain time in their life cycle, one day before adulthood, hermaphrodites can be identified through the addition of a vulva near their tail. In males (XO), there are low levels of ''tra-1'' activity, resulting in a male reproductive system. Recent research has shown that there are three other genes, ''fem-1, fem-2, and fem-3,'' that negatively regulate the TRA-1 pathway and act as the final determiner of sex in ''C. elegans''.Evolution

The sex determination system in ''C. elegans'' is a topic that has been of interest to scientists for years. Since they are used as a model organism, any information discovered about the way their sex determination system might have evolved could further the same evolutionary biology research in other organisms. After almost 30 years of research, scientists have begun to put together the pieces in the evolution of such a system. What they have discovered is that there is a complex pathway involved that has several layers of regulation. The closely related organism '' Caenorhabditis briggsae'' has been studied extensively and its whole genome sequence has helped put together the missing pieces in the evolution of ''C. elegans'' sex determination. It has been discovered that two genes have assimilated, leading to the proteins XOL-1 and MIX-1 having an effect on sex determination in ''C. elegans'' as well. Mutations in the XOL-1 pathway leads to feminization in ''C. elegans .'' The ''mix-1'' gene is known to hypoactivate the X chromosome and regulates the morphology of the male tail in ''C. elegans.'' Looking at the nematode as a whole, the male and hermaphrodite sex likely evolved from parallel evolution. Parallel evolution is defined as similar traits evolving from an ancestor in similar conditions; simply put, the two species evolve in similar ways over time. An example of this would bemarsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

and placental mammals. Scientists have also hypothesized that hermaphrodite asexual reproduction, or "selfing", could have evolved convergently by studying species similar to ''C. elegans'' Other studies on the sex determination evolution suggest that genes involving sperm evolve at the faster rate than female genes. However, sperm genes on the X chromosome have reduced evolution rates. Sperm genes have short coding sequences, high codon bias, and disproportionate representation among orphan genes. These characteristics of sperm genes may be the reason for their high rates of evolution and may also suggest how sperm genes evolved out of hermaphrodite worms. Overall, scientists have a general idea of the sex determination pathway in ''C. elegans'', however, the evolution of how this pathway came to be is not yet well defined.

Development

Embryonic development

The fertilized zygote undergoes rotational holoblastic cleavage. Sperm entry into the oocyte commences formation of an anterior-posterior axis. The sperm microtubule organizing center directs the movement of the sperm pronucleus to the future posterior pole of the embryo, while also inciting the movement of PAR proteins, a group of cytoplasmic determination factors, to their proper respective locations. As a result of the difference in PAR protein distribution, the first cell division is highly asymmetric. ''C. elegans''embryogenesis

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male ...

is among the best understood examples of asymmetric cell division.

All cells of the germline arise from a single primordial germ cell, called the ''P4'' cell, established early in embryogenesis

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male ...

. This primordial cell divides to generate two germline precursors that do not divide further until after hatching.

Axis formation

The resulting daughter cells of the first cell division are called the AB cell (containing PAR-6 and PAR-3) and the P1 cell (containing PAR-1 and PAR-2). A second cell division produces the ABp and ABa cells from the AB cell, and the EMS and P2 cells from the P1 cell. This division establishes the dorsal-ventral axis, with the ABp cell forming the dorsal side and the EMS cell marking the ventral side. Through Wnt signaling, the P2 cell instructs the EMS cell to divide along the anterior-posterior axis. Through Notch signaling, the P2 cell differentially specifies the ABp and ABa cells, which further defines the dorsal-ventral axis. The left-right axis also becomes apparent early in embryogenesis, although it is unclear exactly when specifically the axis is determined. However, most theories of the L-R axis development involve some kind of differences in cells derived from the AB cell.Gastrulation

Gastrulation occurs after the embryo reaches the 24-cell stage. ''C. elegans'' are a species ofprotostome

Protostomia () is the clade of animals once thought to be characterized by the formation of the organism's mouth before its anus during embryonic development. This nature has since been discovered to be extremely variable among Protostomia's memb ...

s, so the blastopore eventually forms the mouth. Involution into the blastopore begins with movement of the endoderm

Endoderm is the innermost of the three primary germ layers in the very early embryo. The other two layers are the ectoderm (outside layer) and mesoderm (middle layer). Cells migrating inward along the archenteron form the inner layer of the gastr ...

cells and subsequent formation of the gut, followed by the P4 germline precursor, and finally the mesoderm

The mesoderm is the middle layer of the three germ layers that develops during gastrulation in the very early development of the embryo of most animals. The outer layer is the ectoderm, and the inner layer is the endoderm.Langman's Medical ...

cells, including the cells that eventually form the pharynx. Gastrulation ends when epiboly of the hypoblasts closes the blastopore.

Post-embryonic development

reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – "offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. There are two forms of reproduction: Asexual reproduction, asexual and Sexual ...

, hatched larvae

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect developmental biology, development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typical ...

develop through four larval stages - L1, L2, L3, and L4 - in just 3 days at 20 °C. When conditions are stressed, as in food insufficiency, excessive population density or high temperature, ''C. elegans'' can enter an alternative third larval stage, L2d, called the dauer stage (''Dauer'' is German for permanent). A specific dauer pheromone regulates entry into the dauer state. This pheromone is composed of similar derivatives of the 3,6-dideoxy sugar, ascarylose. Ascarosides, named after the ascarylose base, are involved in many sex-specific and social behaviors. In this way, they constitute a chemical language that ''C. elegans'' uses to modulate various phenotypes. Dauer larvae are stress-resistant; they are thin and their mouths are sealed with a characteristic dauer cuticle and cannot take in food. They can remain in this stage for a few months. The stage ends when conditions improve favour further growth of the larva, now moulting into the L4 stage, even though the gonad development is arrested at the L2 stage.

Each stage transition is punctuated by a molt of the worm's transparent cuticle. Transitions through these stages are controlled by genes of the heterochronic pathway, an evolutionarily conserved set of regulatory factors. Many heterochronic genes code for microRNA

Micro ribonucleic acid (microRNA, miRNA, μRNA) are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules containing 21–23 nucleotides. Found in plants, animals, and even some viruses, miRNAs are involved in RNA silencing and post-transcr ...

s, which repress the expression of heterochronic transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription (genetics), transcription of genetics, genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding t ...

s and other heterochronic miRNAs. miRNAs were originally discovered in ''C. elegans.'' Important developmental events controlled by heterochronic genes include the division and eventual syncitial fusion of the hypodermic seam cells, and their subsequent secretion of the alae in young adults. It is believed that the heterochronic pathway represents an evolutionarily conserved predecessor to circadian clocks.

Some nematodes have a fixed, genetically determined number of cells, a phenomenon known as eutely. The adult ''C. elegans'' hermaphrodite has 959 somatic cells and the male has 1033 cells, although it has been suggested that the number of their intestinal cells can increase by one to three in response to gut microbes experienced by mothers. Much of the literature describes the cell number in males as 1031, but the discovery of a pair of left and right MCM neurons increased the number by two in 2015. The number of cells does not change after cell division ceases at the end of the larval period, and subsequent growth is due solely to an increase in the size of individual cells.

Ecology

The different '' Caenorhabditis'' species occupy various nutrient- and bacteria-rich environments. They feed on the bacteria that develop in decaying organic matter ( microbivory). They possess chemosensory receptors which enable the detection of bacteria and bacterial-secreted metabolites (such as iron siderophores), so that they can migrate towards their bacterial prey. Soil lacks enough organic matter to support self-sustaining populations. ''C. elegans'' can survive on a diet of a variety of bacteria, but its wild ecology is largely unknown. Most laboratory strains were taken from artificial environments such as gardens and compost piles. More recently, ''C. elegans'' has been found to thrive in other kinds of organic matter, particularly rotting fruit. ''C. elegans'' can also ingest pollutants, especially tiny nanoplastics, which could enable the association with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, resulting in the dissemination of nanoplastics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria by ''C. elegans'' across the soil.''C. elegans'' can also use different species of

yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

, including ''Cryptococcus laurentii

''Papiliotrema laurentii'' (synonym ''Cryptococcus laurentii'') is a species of fungus in the family (biology), family Rhynchogastremaceae. It is typically isolated in its yeast state.

In its yeast state, it is a rare human pathogen, able to pro ...

'' and '' C. kuetzingii'', as sole sources of food. Although a bacterivore, ''C. elegans'' can be killed by a number of pathogenic bacteria, including human pathogens such as ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posi ...

'', ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Aerobic organism, aerobic–facultative anaerobe, facultatively anaerobic, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped bacteria, bacterium that can c ...

'', '' Salmonella enterica'' or '' Enterococcus faecalis''. Pathogenic bacteria can also form biofilms, whose sticky exopolymer matrix could impede ''C. elegans'' motility and cloaks bacterial quorum sensing chemoattractants from predator detection.

Invertebrates such as millipede

Millipedes (originating from the Latin , "thousand", and , "foot") are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derive ...

s, insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, isopod

Isopoda is an Order (biology), order of crustaceans. Members of this group are called isopods and include both Aquatic animal, aquatic species and Terrestrial animal, terrestrial species such as woodlice. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons ...

s, and gastropod

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and fro ...

s can transport dauer larvae to various suitable locations. The larvae have also been seen to feed on their hosts when they die.

Nematodes can survive

desiccation

Desiccation is the state of extreme dryness, or the process of extreme drying. A desiccant is a hygroscopic (attracts and holds water) substance that induces or sustains such a state in its local vicinity in a moderately sealed container. The ...

, and in ''C. elegans'', the mechanism for this capability has been demonstrated to be late embryogenesis abundant proteins.

''C. elegans'', as other nematodes, can be eaten by predator nematodes and other omnivores, including some insects. The Orsay virus is a virus that affects ''C. elegans'', as well as the Caenorhabditis elegans Cer1 virus and the Caenorhabditis elegans Cer13 virus. ; Interactions with fungi Wild isolates of ''Caenorhabditis elegans'' are regularly found with infections by

Microsporidia

Microsporidia are a group of spore-forming unicellular parasites. These spores contain an extrusion apparatus that has a coiled polar tube ending in an anchoring disc at the apical part of the spore.Franzen, C. (2005). How do Microsporidia inva ...

fungi. One such species, '' Nematocida parisii'', replicates in the intestines of ''C. elegans''.

'' Arthrobotrys oligospora'' is the model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

for interactions between fungi and nematodes. It is the most common and widespread nematode capturing fungus.

Use as a model organism

In 1963,Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner (13 January 1927 – 5 April 2019) was a South African biologist. In 2002, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with H. Robert Horvitz and Sir John E. Sulston. Brenner made significant contributions to wo ...

proposed using ''C. elegans'' as a model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

for the investigation primarily of neural development in animals. It is one of the simplest organisms with a nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

. The neurons do not fire action potentials

An action potential (also known as a nerve impulse or "spike" when in a neuron) is a series of quick changes in voltage across a cell membrane. An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell rapidly rises and falls. ...

, and do not express any voltage-gated sodium channels. In the hermaphrodite, this system comprises 302 neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

s the pattern of which has been comprehensively mapped,

in what is known as a connectome

A connectome () is a comprehensive map of neural connections in the brain, and may be thought of as its " wiring diagram". These maps are available in varying levels of detail. A functional connectome shows connections between various brain ...

, and shown to be a small-world network

A small-world network is a graph characterized by a high clustering coefficient and low distances. In an example of the social network, high clustering implies the high probability that two friends of one person are friends themselves. The l ...

.

Research has explored the neural and molecular mechanisms that control several behaviors of ''C. elegans'', including chemotaxis

Chemotaxis (from ''chemical substance, chemo-'' + ''taxis'') is the movement of an organism or entity in response to a chemical stimulus. Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell organism, single-cell or multicellular organisms direct thei ...

, thermotaxis

Thermotaxis is a behavior in which an organism directs its locomotion up or down a gradient of temperature. Thermotaxis is a behavior that organisms navigate on depending on the temperature. ''“Thermo”'' means heat and or the temperature and ...

, mechanotransduction, learning

Learning is the process of acquiring new understanding, knowledge, behaviors, skills, value (personal and cultural), values, Attitude (psychology), attitudes, and preferences. The ability to learn is possessed by humans, non-human animals, and ...

, memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembe ...

, and mating behaviour. In 2019 the connectome of the male was published using a technique distinct from that used for the hermaphrodite. The same paper used the new technique to redo the hermaphrodite connectome, finding 1,500 new synapses.

It has been used as a model organism to study molecular mechanisms in metabolic diseases.

Brenner also chose it as it is easy to grow in bulk populations, and convenient for genetic analysis. It is a multicellular

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell (biology), cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, Embryophyte, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organism ...

eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

organism, yet simple enough to be studied in great detail. The transparency of ''C. elegans'' facilitates the study of cellular differentiation

Cellular differentiation is the process in which a stem cell changes from one type to a differentiated one. Usually, the cell changes to a more specialized type. Differentiation happens multiple times during the development of a multicellula ...

and other developmental processes in the intact organism. The spicules in the male clearly distinguish males from females. Strains are cheap to breed and can be frozen. When subsequently thawed, they remain viable, allowing long-term storage. Maintenance is easy when compared to other multicellular model organisms. A few hundred nematodes can be kept on a single agar plate

An agar plate is a Petri dish that contains a growth medium solidified with agar, used to Microbiological culture, culture microorganisms. Sometimes selective compounds are added to influence growth, such as antibiotics.

Individual microorganism ...

and suitable growth medium. Brenner described the use of a mutant of ''E. coli'' – OP50. OP50 is a uracil

Uracil () (nucleoside#List of nucleosides and corresponding nucleobases, symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleotide bases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via ...

-requiring organism and its deficiency in the plate prevents the overgrowth of bacteria which would obscure the worms. The use of OP50 does not demand any major laboratory safety measures, since it is non-pathogenic and easily grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) media overnight.

Cell lineage mapping

The developmental fate of every single somatic cell (959 in the adult hermaphrodite; 1031 in the adult male) has been mapped. These patterns of cell lineage are largely invariant between individuals, whereas in mammals, cell development is more dependent on cellular cues from the embryo. As mentioned previously, the first cell divisions of earlyembryogenesis

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male ...

in ''C. elegans'' are among the best understood examples of asymmetric cell divisions, and the worm is a very popular model system for studying developmental biology.

Programmed cell death

Programmed cell death (apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

) eliminates many additional cells (131 in the hermaphrodite, most of which would otherwise become neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

s); this "apoptotic predictability" has contributed to the elucidation of some apoptotic genes. Cell death-promoting genes and a single cell-death inhibitor have been identified.

RNA interference and gene silencing

RNA interference

RNA interference (RNAi) is a biological process in which RNA molecules are involved in sequence-specific suppression of gene expression by double-stranded RNA, through translational or transcriptional repression. Historically, RNAi was known by ...

(RNAi) is a relatively straightforward method of disrupting the function of specific genes. Silencing the function of a gene can sometimes allow a researcher to infer its possible function. The nematode can be soaked in, injected with, or fed with genetically transformed bacteria that express

Express, The Expresss or EXPRESS may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Film

* ''Express: Aisle to Glory'', a 1998 comedy short film featuring Kal Penn

* ''The Express: The Ernie Davis Story'', a 2008 film starring Dennis Quaid

* The Expre ...

the double-stranded RNA of interest, the sequence of which complements the sequence of the gene that the researcher wishes to disable.

RNAi has emerged as a powerful tool in the study of functional genomics. ''C. elegans'' has been used to analyse gene functions and claim the promise of future findings in the systematic genetic interactions.

Environmental RNAi uptake is much worse in other species of worms in the genus ''Caenorhabditis''. Although injecting RNA into the body cavity of the animal induces gene silencing in most species, only ''C. elegans'' and a few other distantly related nematodes can take up RNA from the bacteria they eat for RNAi. This ability has been mapped down to a single gene, ''sid-2'', which, when inserted as a transgene

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

in other species, allows them to take up RNA for RNAi as ''C. elegans'' does.

Cell division and cell cycle

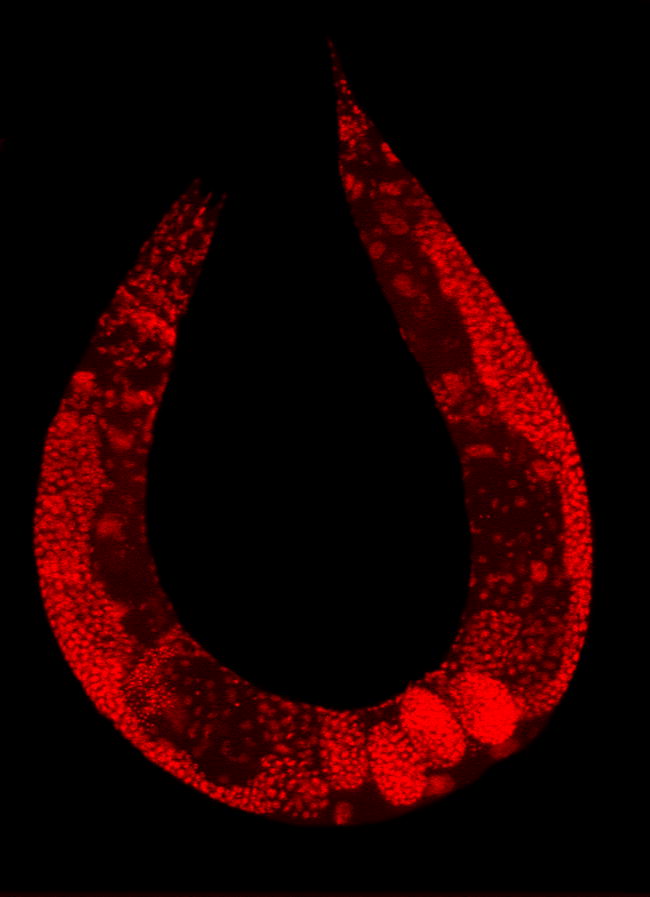

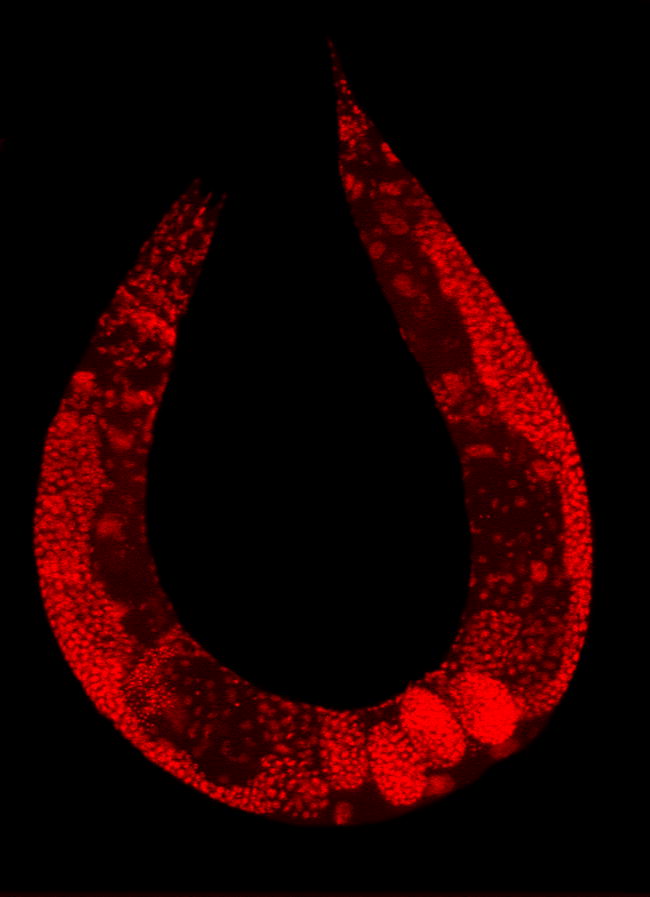

Research intomeiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

has been considerably simplified since every germ cell nucleus is at the same given position as it moves down the gonad, so is at the same stage in meiosis. In an early phase of meiosis, the oocytes become extremely resistant to radiation and this resistance depends on expression of genes ''rad51'' and ''atm'' that have key roles in recombinational repair. Gene '' mre-11'' also plays a crucial role in recombinational repair of DNA damage during meiosis. Furthermore, during meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

in ''C. elegans'' the tumor suppressor BRCA1/BRC-1 and the structural maintenance of chromosomes SMC5/ SMC6 protein complex interact to promote high fidelity repair of DNA double-strand breaks.

A study of the frequency of outcrossing in natural populations showed that selfing is the predominant mode of reproduction in ''C. elegans'', but that infrequent outcrossing events occur at a rate around 1%. Meioses that result in selfing are unlikely to contribute significantly to beneficial genetic variability, but these meioses may provide the adaptive benefit of recombinational repair of DNA damages that arise, especially under stressful conditions.

Drug abuse and addiction

Nicotine dependence can also be studied using ''C. elegans'' because it exhibits behavioral responses to nicotine that parallel those of mammals. These responses include acute response, tolerance, withdrawal, and sensitization.Biological databases

As for most model organisms, scientists that work in the field curate a dedicated online database and WormBase is that for ''C. elegans''. The WormBase attempts to collate all published information on ''C. elegans'' and other related nematodes. Information on ''C. elegans'' is included with data on other model organisms in the Alliance of Genome Resources.Ageing

''C. elegans'' has been a model organism for research intoageing

Ageing (or aging in American English) is the process of becoming older until death. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi; whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biol ...

; for example, the inhibition of an insulin-like growth factor

The insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) are proteins with high sequence similarity to insulin. IGFs are part of a complex system that cells use to communicate with their physiologic environment. This complex system (often referred to as the IGF ...

signaling pathway has been shown to increase adult lifespan threefold; while glucose feeding promotes oxidative stress and reduces adult lifespan by a half. Similarly, induced degradation of an insulin/IGF-1 receptor late in life extended life expectancy of worms dramatically.

Long-lived mutant

In biology, and especially in genetics, a mutant is an organism or a new genetic character arising or resulting from an instance of mutation, which is generally an alteration of the DNA sequence of the genome or chromosome of an organism. It i ...

s of ''C. elegans'' were demonstrated to be resistant to oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal ...

and UV light. These long-lived mutants had a higher DNA repair

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell (biology), cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is cons ...

capability than wild-type ''C. elegans''. Knockdown of the nucleotide excision repair gene Xpa-1 increased sensitivity to UV and reduced the life span of the long-lived mutants. These findings indicate that DNA repair capability underlies longevity. Consistent with the idea that oxidative DNA damage causes aging, it was found that in ''C. elegans'', exosome-mediated delivery of superoxide dismutase (SOD) reduces the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and significantly extends lifespan, i.e. delays aging under normal, as well as hostile conditions.

The capacity to repair DNA damage by the process of nucleotide excision repair declines with age.

''C. elegans'' exposed to 5mM lithium chloride

Lithium chloride is a chemical compound with the formula Li Cl. The salt is a typical ionic compound (with certain covalent characteristics), although the small size of the Li+ ion gives rise to properties not seen for other alkali metal chlorid ...

(LiCl) showed lengthened life spans. When exposed to 10ÎĽM LiCl, reduced mortality was observed, but not with 1ÎĽM.

''C. elegans'' has been instrumental in the identification of the functions of genes implicated in Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems wit ...

, such as presenilin. Moreover, extensive research on ''C. elegans'' has identified RNA-binding proteins as essential factors during germline and early embryonic development.

Telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes (see #Sequences, Sequences). Telomeres are a widespread genetic feature most commonly found in eukaryotes. In ...

s, the length of which have been shown to correlate with increased lifespan and delayed onset of senescence

Senescence () or biological aging is the gradual deterioration of Function (biology), functional characteristics in living organisms. Whole organism senescence involves an increase in mortality rate, death rates or a decrease in fecundity with ...

in a multitude of organisms, from ''C. elegans'' to humans, show an interesting behaviour in ''C. elegans.'' While ''C. elegans'' maintains its telomeres in a canonical way similar to other eukaryotes, in contrast ''Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (an insect of the Order (biology), order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the "vinegar fly", "pomace fly" ...

'' is noteworthy in its use of retrotransposon

Retrotransposons (also called Class I transposable elements) are mobile elements which move in the host genome by converting their transcribed RNA into DNA through reverse transcription. Thus, they differ from Class II transposable elements, or ...

s to maintain its telomeres, during knock-out of the catalytic subunit of the telomerase (''trt-1'') ''C. elegans'' can gain the ability of alternative telomere lengthening (ALT). ''C. elegans'' was the first eukaryote to gain ALT functionality after knock-out of the canonical telomerase pathway. ALT is also observed in about 10-15% of all clinical cancers. Thus ''C. elegans'' is a prime candidate for ALT research. Bayat et al. showed the paradoxical shortening of telomeres during '' trt-1'' over-expression which lead to near sterility while the worms even exhibited a slight increase in lifespan, despite shortened telomeres.

Sleep

''C. elegans'' is notable in animal sleep studies as the most primitive organism to display sleep-like states. In ''C. elegans'', a lethargus phase occurs shortly before each moult. ''C. elegans'' has also been demonstrated to sleep after exposure to physical stress, including heat shock, UV radiation, and bacterial toxins.Sensory biology

While the worm has no eyes, it has been found to be sensitive to light due to a third type of light-sensitive animal photoreceptor protein, LITE-1, which is 10 to 100 times more efficient at absorbing light than the other two types of photopigments ( opsins and cryptochromes) found in the animal kingdom. ''C. elegans'' is remarkably adept at tolerating acceleration. It can withstand 400,000 g's, according to geneticists at the University of SĂŁo Paulo in Brazil. In an experiment, 96% of them were still alive without adverse effects after an hour in an ultracentrifuge.Drug library screening

Having a small size and short life cycle, C. elegans is one of the few organisms that can enable in vivo high throughput screening (HTS) platforms for the evaluation of chemical libraries of drugs and toxins in a multicellular organism. Orthologous phenotypes observable in C. elegans for human diseases have the potential to enable profiling of drug library profiling that can inform potential repurposing of existing approved drugs for therapeutic indications in humans.Spaceflight research

''C. elegans'' made news when specimens were discovered to have survived the Space Shuttle ''Columbia'' disaster in February 2003. Later, in January 2009, live samples of ''C. elegans'' from theUniversity of Nottingham

The University of Nottingham is a public research university in Nottingham, England. It was founded as University College Nottingham in 1881, and was granted a royal charter in 1948.

Nottingham's main campus (University Park Campus, Nottingh ...

were announced to be spending two weeks on the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is a large space station that was Assembly of the International Space Station, assembled and is maintained in low Earth orbit by a collaboration of five space agencies and their contractors: NASA (United ...

that October, in a space research project to explore the effects of zero gravity

Weightlessness is the complete or near-complete absence of the sensation of weight, i.e., zero apparent weight. It is also termed zero g-force, or zero-g (named after the g-force) or, incorrectly, zero gravity.

Weight is a measurement of the fo ...

on muscle development and physiology. The research was primarily about genetic basis of muscle atrophy, which relates to spaceflight

Spaceflight (or space flight) is an application of astronautics to fly objects, usually spacecraft, into or through outer space, either with or without humans on board. Most spaceflight is uncrewed and conducted mainly with spacecraft such ...

or being bed-ridden, geriatric, or diabetic. Descendants of the worms aboard Columbia in 2003 were launched into space on ''Endeavour'' for the STS-134

STS-134 (ISS assembly sequence, ISS assembly flight ULF6) was the penultimate mission of NASA's Space Shuttle program and the 25th and last spaceflight of . This flight delivered the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer and an ExPRESS Logistics Carrier ...

mission. Additional experiments on muscle dystrophy during spaceflight were carried on board the ISS starting in 2018. It was shown that the genes affecting muscles attachment were expressed less in space. However, it has yet to be seen if this affects muscle strength.

Genetics

Genome

''C. elegans'' was the first multicellular organism to have its whole genome sequenced. The sequence was published in 1998, although some small gaps were present; the last gap was finished by October 2002. In the run up to the whole genome the ''C. elegans'' Sequencing Consortium/''C. elegans'' Genome Project released several partial scans including Wilson et al. 1994.

''C. elegans'' was the first multicellular organism to have its whole genome sequenced. The sequence was published in 1998, although some small gaps were present; the last gap was finished by October 2002. In the run up to the whole genome the ''C. elegans'' Sequencing Consortium/''C. elegans'' Genome Project released several partial scans including Wilson et al. 1994.

Size and gene content

The ''C. elegans'' genome is about 100 millionbase pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s long and consists of six pairs of chromosomes in hermaphrodites or five pairs of autosomes with XO chromosome in male ''C. elegans'' and a mitochondrial genome. Its gene density is about one gene per five kilo-base pairs. Intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e., a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gen ...

s make up 26% and intergenic regions 47% of the genome. Many genes are arranged in clusters and how many of these are operons is unclear. ''C. elegans'' and other nematodes are among the few eukaryotes currently known to have operons; these include trypanosomes, flatworms (notably the trematode

Trematoda is a Class (biology), class of flatworms known as trematodes, and commonly as flukes. They are obligate parasite, obligate Endoparasites, internal parasites with a complex biological life cycle, life cycle requiring at least two Host ( ...

'' Schistosoma mansoni''), and a primitive chordate tunicate '' Oikopleura dioica''. Many more organisms are likely to be shown to have these operons.

The genome contains an estimated 20,470 protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

-coding gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s. About 35% of ''C. elegans'' genes have human homologs. Remarkably, human genes have been shown repeatedly to replace their ''C. elegans'' homologs when introduced into ''C. elegans''. Conversely, many ''C. elegans'' genes can function similarly to mammalian genes.

The number of known RNA genes in the genome has increased greatly due to the 2006 discovery of a new class called '' 21U-RNA'' genes, and the genome is now believed to contain more than 16,000 RNA genes, up from as few as 1,300 in 2005.

Scientific curators continue to appraise the set of known genes; new gene models continue to be added and incorrect ones modified or removed.

The reference ''C. elegans'' genome sequence continues to change as new evidence reveals errors in the original sequencing. Most changes are minor, adding or removing only a few base pairs of DNA. For example, the WS202 release of WormBase (April 2009) added two base pairs to the genome sequence. Sometimes, more extensive changes are made as noted in the WS197 release of December 2008, which added a region of over 4,300 bp to the sequence.

The ''C. elegans'' Genome Project's Wilson et al. 1994 found CelVav and a von Willebrand factor A domain and with Wilson et al. 1998 provides the first credible evidence for an aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) homolog outside of vertebrates. 2

Related genomes

In 2003, the genome sequence of the related nematode '' C. briggsae'' was also determined, allowing researchers to study thecomparative genomics

Comparative genomics is a branch of biological research that examines genome sequences across a spectrum of species, spanning from humans and mice to a diverse array of organisms from bacteria to chimpanzees. This large-scale holistic approach c ...

of these two organisms. The genome sequences of more nematodes from the same genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

e.g., '' C. remanei'', '' C. japonica'' and '' C. brenneri'' (named after Brenner), have also been studied using the shotgun sequencing technique. These sequences have now been completed.

Other genetic studies

As of 2014, ''C. elegans'' is the most basal species in the 'Elegans' group (10 species) of the 'Elegans' supergroup (17 species) in phylogenetic studies. It forms a branch of its own distinct to any other species of the group.

Tc1 transposon is a DNA transposon active in ''C. elegans''.

As of 2014, ''C. elegans'' is the most basal species in the 'Elegans' group (10 species) of the 'Elegans' supergroup (17 species) in phylogenetic studies. It forms a branch of its own distinct to any other species of the group.

Tc1 transposon is a DNA transposon active in ''C. elegans''.

Scientific community

Several scientists have won theNobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

for scientific discoveries made working with ''C. elegans''. It was awarded in 2002 to Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner (13 January 1927 – 5 April 2019) was a South African biologist. In 2002, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with H. Robert Horvitz and Sir John E. Sulston. Brenner made significant contributions to wo ...

, H. Robert Horvitz, and John Sulston for their work on the genetics of organ development and programmed cell death

Programmed cell death (PCD) sometimes referred to as cell, or cellular suicide is the death of a cell (biology), cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy. PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usual ...

, in 2006 to Andrew Fire and Craig C. Mello for their discovery of RNA interference

RNA interference (RNAi) is a biological process in which RNA molecules are involved in sequence-specific suppression of gene expression by double-stranded RNA, through translational or transcriptional repression. Historically, RNAi was known by ...

, and in 2024 to Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun for their discovery of microRNA

Micro ribonucleic acid (microRNA, miRNA, μRNA) are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules containing 21–23 nucleotides. Found in plants, animals, and even some viruses, miRNAs are involved in RNA silencing and post-transcr ...

and its role in gene regulation.

In 2008, Martin Chalfie

Martin Lee Chalfie (born January 15, 1947) is an American scientist. He is University Professor at Columbia University. He shared the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Osamu Shimomura and Roger Y. Tsien "for the discovery and develop ...

shared a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on green fluorescent protein; some of the research involved the use of ''C. elegans''.

Many scientists who research ''C. elegans ''closely connect to Sydney Brenner, with whom almost all research in this field began in the 1970s; they have worked as either a postdoctoral

A postdoctoral fellow, postdoctoral researcher, or simply postdoc, is a person professionally conducting research after the completion of their doctoral studies (typically a PhD). Postdocs most commonly, but not always, have a temporary acade ...

or a postgraduate researcher in Brenner's lab or in the lab of someone who previously worked with Brenner. Most who worked in his lab later established their own worm research labs, thereby creating a fairly well-documented "lineage" of ''C. elegans'' scientists, which was recorded into the WormBase database in some detail at the 2003 International Worm Meeting.

See also

* Animal testing on invertebrates *Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the emission of light during a chemiluminescence reaction by living organisms. Bioluminescence occurs in multifarious organisms ranging from marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some Fungus, fungi, microorgani ...

* Eileen Southgate

* Intronerator

* OpenWorm

* WormBook

References

Further reading

* * *External links

* Brenner S (2002) Nature's Gift to Science. In. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2002/brenner-lecture.pdf (also Horvitz and Sulston lectures)WormBase

– an extensive online database covering the biology and genomics of ''C. elegans'' and other nematodes

WormAtlas

– online database on all aspects of ''C. elegans'' anatomy with detailed explanations and high-quality images

WormBook

– online review of ''C. elegans'' biology

– another genome database for ''C. elegans'', maintained at the NCBI

''C. elegans'' II

– a free online textbook.

WormWeb Neural Network

– an online tool for visualizing and navigating the connectome of ''C. elegans''

– a visual introduction to ''C. elegans'' *

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' at eppo.int

( EPPO code CAEOEL) * {{Authority control Nematodes described in 1900 Articles containing video clips Animal models in neuroscience