Battle Of Ronas Voe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Ronas Voe was a naval engagement between the English

''

''

Captain Herbert (''Cambridge)'' was the first to receive his orders in a letter sent by the Royal Navy's Chief Secretary to the Admiralty Samuel Pepys. He stated the orders were "at the desire of the

Captain Herbert (''Cambridge)'' was the first to receive his orders in a letter sent by the Royal Navy's Chief Secretary to the Admiralty Samuel Pepys. He stated the orders were "at the desire of the

The battle is commonly reported to have occurred in February 1674, however the only known extant contemporary report of the battle indicates that it occurred on . This was one day after Pepys' original twenty day deadline for the completion of his orders sent to Captain Herbert, and 23 days after the signing of the Treaty of Westminster.

Upon their arrival, ''Cambridge'', ''Newcastle'' and ''Crown'' entered Ronas Voe, where a short, one-sided battle ensued. While a single

The battle is commonly reported to have occurred in February 1674, however the only known extant contemporary report of the battle indicates that it occurred on . This was one day after Pepys' original twenty day deadline for the completion of his orders sent to Captain Herbert, and 23 days after the signing of the Treaty of Westminster.

Upon their arrival, ''Cambridge'', ''Newcastle'' and ''Crown'' entered Ronas Voe, where a short, one-sided battle ensued. While a single

The site where the bodies of those killed in the battle were buried is known as the Hollanders' Knowe, and the site is marked by a small

The site where the bodies of those killed in the battle were buried is known as the Hollanders' Knowe, and the site is marked by a small

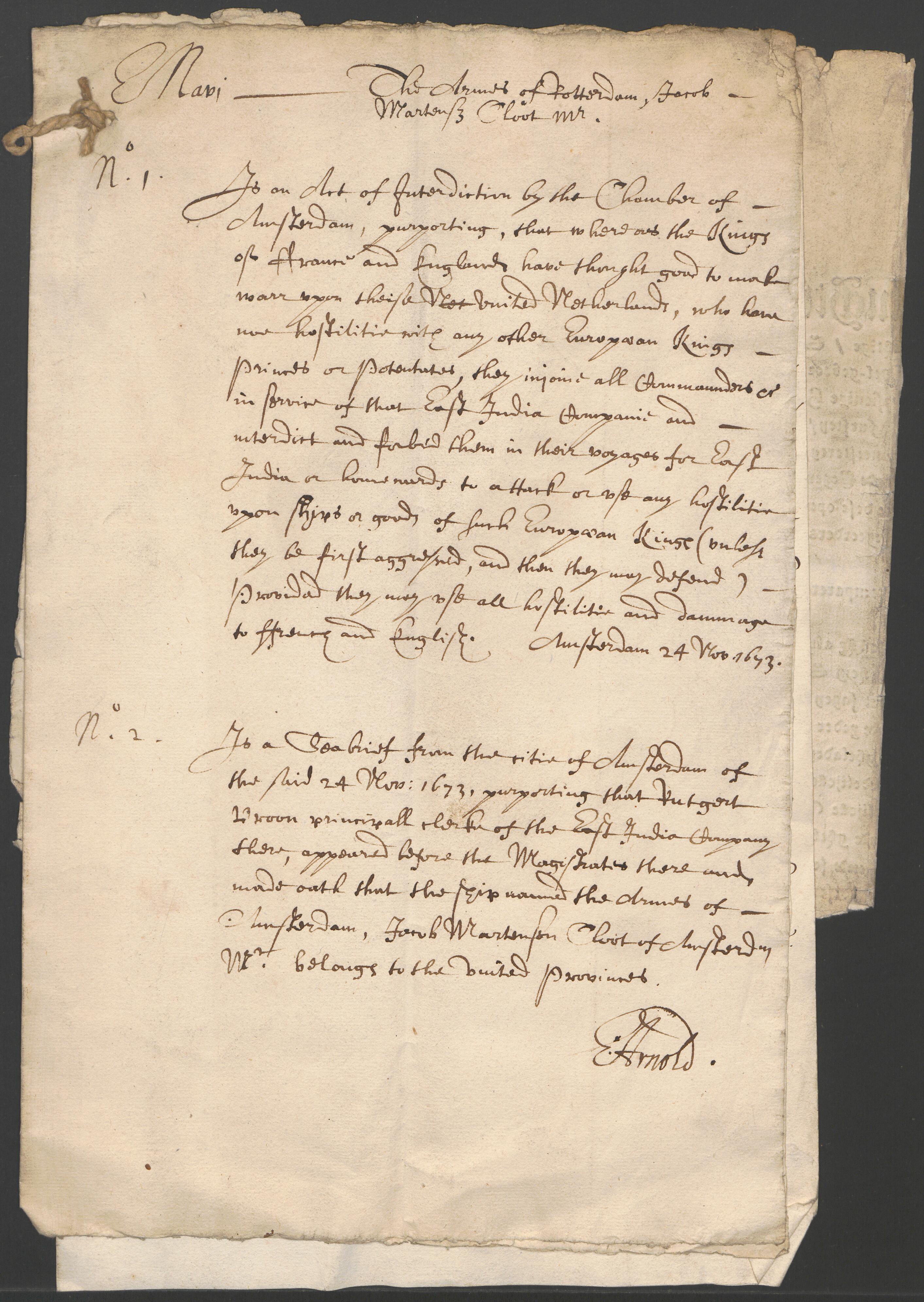

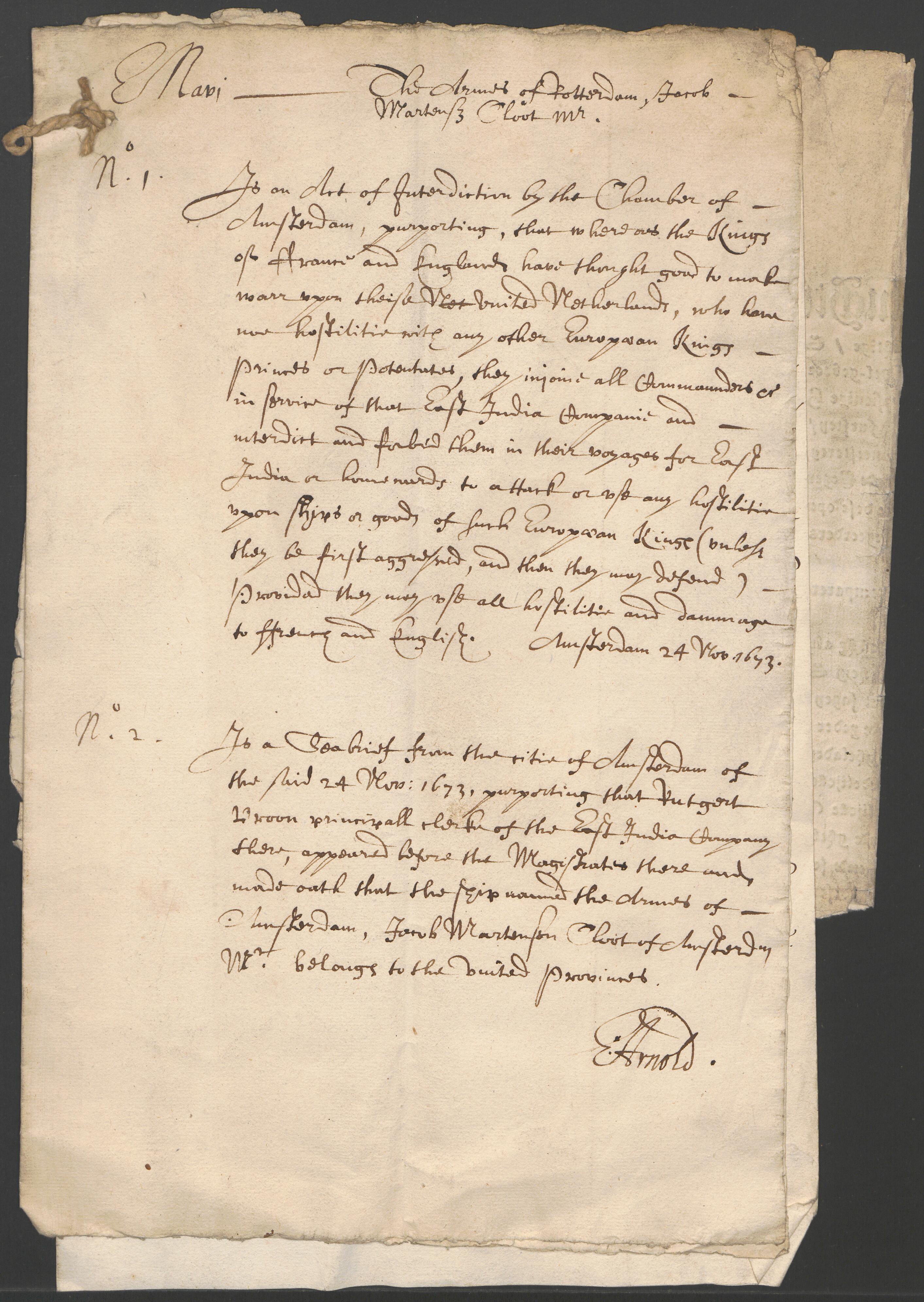

Dutch Prize Papers

– Archive of papers aboard ''Wapen van Rotterdam'' when it was captured. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ronas Voe, Battle Of History of Shetland Conflicts in 1674 Naval battles of the Third Anglo-Dutch War Maritime incidents in 1674 Battles involving England Battles involving the Dutch East India Company Dutch East India Company Battles involving the Dutch Republic Naval battles involving England 17th century in Shetland 1674 in Scotland Northmavine

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

and the Dutch East India

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock co ...

ship ''Wapen van Rotterdam

''Wapen van Rotterdam'' was a Dutch East India Company East Indiaman that was built in 1666 for the Rotterdam Chamber of the VOC, and was operated from 1667, twice travelling to the Indies, until its capture by the English Royal Navy's frigat ...

'' on 14 March 1674 in Ronas Voe, Shetland as part of the Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo-Dutch War ( nl, Derde Engels-Nederlandse Oorlog), 27 March 1672 to 19 February 1674, was a naval conflict between the Dutch Republic and England, in alliance with France. It is considered a subsidiary of the wider 1672 to 1678 ...

. Having occurred 23 days after the signing of the Treaty of Westminster, it is likely to have been the final battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

Shortly after embarking on a journey towards the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

with trade goods and a company of soldiers, extreme weather conditions caused ''Wapen van Rotterdam'' to lose its masts and rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally aircraft, air or watercraft, water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to ...

and it was forced to take shelter in Ronas Voe for a number of months. A whistleblower

A whistleblower (also written as whistle-blower or whistle blower) is a person, often an employee, who reveals information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe or fraudulent. Whi ...

in Shetland informed the English authorities of the ship's presence, and in response three Royal Navy men-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed w ...

and a dogger were dispatched to capture the ship. After a short battle, the ship was captured and taken back to England as a prize of war

A prize of war is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle, typically at sea. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 19th centuries. Basis in inte ...

.

An unknown number of up to 300 of the ship's crew were killed in the battle and were buried nearby in Heylor. A modern memorial to the Dutch crew is erected where they are believed to be buried, bearing the inscription "The Hollanders' Graves".

Background

''

''Wapen van Rotterdam

''Wapen van Rotterdam'' was a Dutch East India Company East Indiaman that was built in 1666 for the Rotterdam Chamber of the VOC, and was operated from 1667, twice travelling to the Indies, until its capture by the English Royal Navy's frigat ...

'' was an East Indiaman

East Indiaman was a general name for any sailing ship operating under charter or licence to any of the East India trading companies of the major European trading powers of the 17th through the 19th centuries. The term is used to refer to vesse ...

with a capacity of 1,124 tons and between 60 and 70 guns

A gun is a ranged weapon designed to use a shooting tube (gun barrel) to launch projectiles. The projectiles are typically solid, but can also be pressurized liquid (e.g. in water guns/cannons, spray guns for painting or pressure washing, ...

. On 16 December 1673, it departed the Texel

Texel (; Texels dialect: ) is a municipality and an island with a population of 13,643 in North Holland, Netherlands. It is the largest and most populated island of the West Frisian Islands in the Wadden Sea. The island is situated north of Den ...

bound for the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

with both trade goods and a company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of people, whether Natural person, natural, Legal person, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common p ...

of soldiers from the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

's private army

A private army (or private military) is a military or paramilitary force consisting of armed combatants who owe their allegiance to a private person, group, or organization, rather than a nation or state.

History

Private armies may form when ...

, along with an army captain

The army rank of captain (from the French ) is a commissioned officer rank historically corresponding to the command of a company of soldiers. The rank is also used by some air forces and marine forces. Today, a captain is typically either t ...

. The ship itself was captained by Jacob Martens Cloet.

To avoid conflict with the English (with whom, due to the Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo-Dutch War ( nl, Derde Engels-Nederlandse Oorlog), 27 March 1672 to 19 February 1674, was a naval conflict between the Dutch Republic and England, in alliance with France. It is considered a subsidiary of the wider 1672 to 1678 ...

, the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

were at war), rather than passing through the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

, the ship was directed northwards where the plan would be to sail around the north of the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

(known as "going north about", which was commonly practised by Dutch East India

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock co ...

ships at that time), before heading southwards again. Due to the extreme weather conditions in its journey northwards, the ship lost its masts and rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally aircraft, air or watercraft, water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to ...

, and southerly winds prevented the ship from being able to pass through either the Pentland Firth

The Pentland Firth ( gd, An Caol Arcach, meaning the Orcadian Strait) is a strait which separates the Orkney Islands from Caithness in the north of Scotland. Despite the name, it is not a firth.

Etymology

The name is presumed to be a corruption ...

or the Fair Isle Channel, so the ship was (probably with considerable difficulty) taken into Ronas Voe in the north-west of Northmavine

Northmavine or Northmaven ( non, Norðan Mæfeið, meaning ‘the land north of the Mavis Grind’) is a peninsula in northwest Mainland Shetland in Scotland. The peninsula has historically formed the civil parish Northmavine. The modern Northmav ...

, Mainland

Mainland is defined as "relating to or forming the main part of a country or continent, not including the islands around it egardless of status under territorial jurisdiction by an entity" The term is often politically, economically and/or dem ...

, Shetland to shelter until the weather improved, and to allow the ship to be repaired. The '' voe'' (Shetland dialect

Shetland dialect (also variously known as Shetlandic; broad or auld Shetland or Shaetlan; and referred to as Modern Shetlandic Scots (MSS) by some linguists) is a dialect of Insular Scots spoken in Shetland, an archipelago to the north of mai ...

for an inlet

An inlet is a (usually long and narrow) indentation of a shoreline, such as a small arm, bay, sound, fjord, lagoon or marsh, that leads to an enclosed larger body of water such as a lake, estuary, gulf or marginal sea.

Overview

In marine geogra ...

or fjord

In physical geography, a fjord or fiord () is a long, narrow inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Alaska, Antarctica, British Columbia, Chile, Denmark, Germany, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Ice ...

) forms a crescent

A crescent shape (, ) is a symbol or emblem used to represent the lunar phase in the first quarter (the "sickle moon"), or by extension a symbol representing the Moon itself.

In Hinduism, Lord Shiva is often shown wearing a crescent moon on his ...

shape around Ronas Hill

Ronas Hill (or Rönies Hill) is a hill in Shetland, Scotland. It is classed as a Marilyn, and is the highest point in the Shetland Islands at an elevation of . A Neolithic chambered cairn is located near the summit.

Location

Ronas Hill (, meani ...

, which would have allowed the ship to lie sheltered regardless of the direction of the wind. A combination of prevailing southerly winds, and, presumably, a scarcity of suitable wood available in Shetland at that time to replace its masts prevented the ship from continuing its journey, and as such it remained in Ronas Voe until March 1674.

During their stay, the crew of the ship would have most likely traded Dutch goods such as Hollands gin and tobacco (and perhaps also goods on the ship originally destined for the Dutch East Indies) with the Shetlanders, in exchange for local foodstuffs available at that time, such as kale

Kale (), or leaf cabbage, belongs to a group of cabbage (''Brassica oleracea'') cultivars grown for their edible leaves, although some are used as ornamentals. Kale plants have green or purple leaves, and the central leaves do not form a head ...

, meal

A meal is an eating occasion that takes place at a certain time and includes consumption of food. The names used for specific meals in English vary, depending on the speaker's culture, the time of day, or the size of the meal.

Although they ca ...

and mutton

Lamb, hogget, and mutton, generically sheep meat, are the meat of domestic sheep, ''Ovis aries''. A sheep in its first year is a lamb and its meat is also lamb. The meat from sheep in their second year is hogget. Older sheep meat is mutton. Gen ...

– either fresh or reestit. The Shetlanders probably would have had quite a lot in common with the Dutch. The native language of the local Shetlanders at that time would have been Norn

Norn may refer to:

*Norn language, an extinct North Germanic language that was spoken in Northern Isles of Scotland

*Norns, beings from Norse mythology

*Norn Iron, the local pronunciation of Northern Ireland

* Norn iron works, an old industrial c ...

, though English would have been understood and used fluently by most. Many Shetlanders (of both the affluent and Commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

s) were also fluent in Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, despite never having never left Shetland, due to the amount of trade done by Dutch ships in Shetland's ports.

From 1603, the Kingdoms of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

had all shared the same monarch with the Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns ( gd, Aonadh nan Crùintean; sco, Union o the Crouns) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas dip ...

, who by 1674 was Charles II. As such, Scotland was actively involved in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, despite not being included in the conflict's name. Shetland, being a part of the Kingdom of Scotland, was therefore at war with the Dutch, however the local Shetland residents of Heylor and adjacent areas in direct contact with the Dutch may not have been aware of the conflict, and would not have considered the visitors as "enemies". A letter must have been sent by someone with an understanding of the political situation (most likely a laird

Laird () is the owner of a large, long-established Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a baron and above a gentleman. This rank was held only by those lairds holding official recognition in ...

, minister, merchant, or some other member of the gentry in Shetland) to inform the authorities of the Dutch ship's presence, and that it could not proceed due to it losing its masts and rudder. As a result, a total of four Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

ships – HMS ''Cambridge'', captained by Arthur Herbert (later the Earl of Torrington); HMS ''Newcastle'', captained by John Wetwang (later Sir John Wetwang); HMS ''Crown'', captained by Richard Carter; and ''Dove

Columbidae () is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with short necks and short slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. They primarily ...

'', captained by Abraham Hyatt – were ordered to set sail for Shetland and to capture the ship.

Call to arms

Captain Herbert (''Cambridge)'' was the first to receive his orders in a letter sent by the Royal Navy's Chief Secretary to the Admiralty Samuel Pepys. He stated the orders were "at the desire of the

Captain Herbert (''Cambridge)'' was the first to receive his orders in a letter sent by the Royal Navy's Chief Secretary to the Admiralty Samuel Pepys. He stated the orders were "at the desire of the Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Monarchs and their consorts are usually styled ''Majesty''.

When used as a direct form of address, spoken or written, it takes ...

", and stressed that the orders were to be carried out swiftly, as the Treaty of Westminster concluding the war was expected to be published within eight days, and any subsequent hostilities were to last no longer than twelve days. The Treaty of Westminster had in fact been signed two days prior to this letter being sent, and was ratified in England the day before the letter was sent.

The following day letters were sent to both Captains Wetwang (''Newcastle)'' and Carter (''Crown'') enclosing the same orders. Pepys also wrote again to Captain Herbert (''Cambridge'') to convey he had arranged for a pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

knowledgeable of Shetland's coast to be sent to him, as well as to inform him that ''Crown'' and ''Dove'' would accompany his ship.

On Captain Herbert (''Cambridge'') wrote to Pepys to inform him that neither the pilot nor ''Dove'' had yet arrived. Pepys replied on to say he had sent instruction to hasten the pilot, and had enquired into ''Dove''Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-west and Clacton-on- ...

wrote to Pepys to inform him that ''Cambridge'' and ''Crown'' had passed by on their way to Shetland. The same day, Pepys replied to a letter from Carter (''Crown'') to inform him that his five weeks' supply of victuals

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or fungal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ing ...

were enough to support his crew until their return from Shetland.

On , ''Dove'' was wrecked on the coast of Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

on the journey northwards, leaving the three remaining ships to continue towards Shetland.

Battle

The battle is commonly reported to have occurred in February 1674, however the only known extant contemporary report of the battle indicates that it occurred on . This was one day after Pepys' original twenty day deadline for the completion of his orders sent to Captain Herbert, and 23 days after the signing of the Treaty of Westminster.

Upon their arrival, ''Cambridge'', ''Newcastle'' and ''Crown'' entered Ronas Voe, where a short, one-sided battle ensued. While a single

The battle is commonly reported to have occurred in February 1674, however the only known extant contemporary report of the battle indicates that it occurred on . This was one day after Pepys' original twenty day deadline for the completion of his orders sent to Captain Herbert, and 23 days after the signing of the Treaty of Westminster.

Upon their arrival, ''Cambridge'', ''Newcastle'' and ''Crown'' entered Ronas Voe, where a short, one-sided battle ensued. While a single East Indiaman

East Indiaman was a general name for any sailing ship operating under charter or licence to any of the East India trading companies of the major European trading powers of the 17th through the 19th centuries. The term is used to refer to vesse ...

might have stood a chance, however small, against three much more manoeuvrable men-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed w ...

on open seas, in the confined space of Ronas Voe and most likely still without replacement masts (evidenced by the fact the ship had not left Ronas Voe), ''Wapen van Rotterdam'' was completely outmatched.

It is recorded that ''Newcastle'' captured ''Wapen van Rotterdam'', and it was taken back to England as a prize of war

A prize of war is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle, typically at sea. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 19th centuries. Basis in inte ...

. A contemporary Dutch newspaper reported that while 400 crew were originally on board ''Wapen van Rotterdam'', later only 100 prisoners were being transported by ''Crown,'' suggesting up to 300 crew may have been killed, although additional prisoners might have been transported on the other English ships. Those killed in the battle were buried nearby in Heylor. Both Cloet and the army captain survived the battle and were taken back to England with the rest of the surviving crew.

Aftermath

''Crown'' took aboard one hundred Dutch prisoners. When the ship returned to England, it experienced extremely bad weather (in which it was reported that 10 valuable ships betweenGreat Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

and Winterton-on-Sea

Winterton-on-Sea is a village and civil parish on the North Sea coast of the English county of Norfolk. It is north of Great Yarmouth and east of Norwich.Ordnance Survey (2002). ''OS Explorer Map 252 - Norfolk Coast East''. .

The civil parish ...

had to be stranded, some of which were destroyed) and was unable to land before it reached Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

on . Samuel Pepys wrote to Captain Carter (''Crown'') on , telling him "His Majesty

Majesty (abbreviated HM for His Majesty or Her Majesty, oral address Your Majesty; from the Latin ''maiestas'', meaning "greatness") is used as a manner of address by many monarchs, usually kings or queens. Where used, the style outranks the st ...

and his Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Monarchs and their consorts are usually styled ''Majesty''.

When used as a direct form of address, spoken or written, it takes ...

are well pleased with his account of the good success of the ''Cambridge'' and ''Newcastle''." The ships returned to the Downs by . Pepys wrote to Captain Herbert (''Cambridge)'' on and passed on that the Lords had commented, "Long may the civility which you mention of the Dutch to his Majesty's ships continue."

Captain Wetwang directed the Dutch ship to Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-west and Clacton-on- ...

on en route to the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

. The remaining Dutch crew were put ashore in Harwich, after which Cloet and the army captain set sail back to the Dutch Republic in a packet boat

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

. Before departing, the Dutch captains valued ''Wapen van Rotterdam'' (and presumably also the trade goods on board) at approximately £50,000 – . In June the same year, the Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

Arthur Annesley asked the Principal Commissioners of Prizes and the Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in ...

to award Captain Wetwang £500 – – for his capture of the ship and its safe return to the Thames. This prize was to be funded from the sale of the goods aboard the ship, or if the value raised was insufficient to fund this prize, the Privy Seal instructed the Lord High Treasurer "to find out some other proper way for payment thereof, as a free gift."

Letters carried by ''Wapen van Rotterdam'' were captured, and still survive in the English admiralty archives. They were partly published in 2014.

Goods put up for sale

On , many of the goods aboard the ship were put up for sale at theEast India House

East India House was the London headquarters of the East India Company, from which much of British India was governed until the British government took control of the Company's possessions in India in 1858. It was located in Leadenhall Street ...

, City of London:

Remaining goods

Those goods still remaining on the ship following the sale, along with the sails and cables not offered for sale were catalogued and stored at his Majesties stores inWoolwich Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard (formally H.M. Dockyard, Woolwich, also known as The King's Yard, Woolwich) was an English Royal Navy Dockyard, naval dockyard along the river Thames at Woolwich in north-west Kent, where many ships were built from the early 1 ...

by :

Fate of ''Wapen van Rotterdam''

''Wapen van Rotterdam'' was renamed HMS ''Arms of Rotterdam'' and was refitted as an unarmedhulk

The Hulk is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in the debut issue of ''The Incredible Hulk (comic book), The Incredible Hulk' ...

. In 1703 ''Arms of Rotterdam'' was broken down in Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

.

The Hollanders' Graves

The site where the bodies of those killed in the battle were buried is known as the Hollanders' Knowe, and the site is marked by a small

The site where the bodies of those killed in the battle were buried is known as the Hollanders' Knowe, and the site is marked by a small granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

cairn

A cairn is a man-made pile (or stack) of stones raised for a purpose, usually as a marker or as a burial mound. The word ''cairn'' comes from the gd, càrn (plural ).

Cairns have been and are used for a broad variety of purposes. In prehis ...

with a plaque

Plaque may refer to:

Commemorations or awards

* Commemorative plaque, a plate or tablet fixed to a wall to mark an event, person, etc.

* Memorial Plaque (medallion), issued to next-of-kin of dead British military personnel after World War I

* Pla ...

that reads "The Hollanders' Graves". These are likely to be the first War grave

A war grave is a burial place for members of the armed forces or civilians who died during military campaigns or operations.

Definition

The term "war grave" does not only apply to graves: ships sunk during wartime are often considered to b ...

s recorded in Shetland.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Dutch Prize Papers

– Archive of papers aboard ''Wapen van Rotterdam'' when it was captured. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ronas Voe, Battle Of History of Shetland Conflicts in 1674 Naval battles of the Third Anglo-Dutch War Maritime incidents in 1674 Battles involving England Battles involving the Dutch East India Company Dutch East India Company Battles involving the Dutch Republic Naval battles involving England 17th century in Shetland 1674 in Scotland Northmavine