Banff National Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Banff National Park is Canada's oldest  The

The

Throughout its history, Banff National Park has been shaped by tension between conservationist and land exploitation interests. The park was established on November 25, 1885, as Banff Hot Springs Reserve, in response to conflicting claims over who discovered

Throughout its history, Banff National Park has been shaped by tension between conservationist and land exploitation interests. The park was established on November 25, 1885, as Banff Hot Springs Reserve, in response to conflicting claims over who discovered

The Stoney Nakoda

The Stoney Nakoda  In 1902, the park was expanded to cover , encompassing areas around Lake Louise, and the Bow,

In 1902, the park was expanded to cover , encompassing areas around Lake Louise, and the Bow,

In 1931, the

In 1931, the

Banff National Park is located in the Rocky Mountains on Alberta's western border with British Columbia in the

Banff National Park is located in the Rocky Mountains on Alberta's western border with British Columbia in the

Lake Louise, a hamlet located northwest of the town of Banff, is home to the landmark

Lake Louise, a hamlet located northwest of the town of Banff, is home to the landmark

The

The

The

The

Under the

Under the

Banff National Park spans three

Banff National Park spans three

The park has 56 recorded mammal species.

The park has 56 recorded mammal species.

Banff National Park is the most visited Alberta tourist destination and one of the most visited national parks in North America, with more than three million tourists annually. Tourism in Banff contributes an estimated billion annually to the

Banff National Park is the most visited Alberta tourist destination and one of the most visited national parks in North America, with more than three million tourists annually. Tourism in Banff contributes an estimated billion annually to the

Banff National Park is managed by

Banff National Park is managed by

The state of grizzly bear populations in Banff is seen as a proxy for ecological integrity. To keep bears away from humans, an electric fence was put up around the summer gondola and parking lot at Lake Louise in 2001. Bear-proof garbage cans, which do not allow bears to access their contents, help to deter them from human sites. The fruit of Buffaloberry bushes is eaten by bears, so the bushes have been removed in some areas where the risk of a bear–human encounter is high.

Aversive conditioning deters bears by modifying their behaviour. Deterrents such as noise makers and

The state of grizzly bear populations in Banff is seen as a proxy for ecological integrity. To keep bears away from humans, an electric fence was put up around the summer gondola and parking lot at Lake Louise in 2001. Bear-proof garbage cans, which do not allow bears to access their contents, help to deter them from human sites. The fruit of Buffaloberry bushes is eaten by bears, so the bushes have been removed in some areas where the risk of a bear–human encounter is high.

Aversive conditioning deters bears by modifying their behaviour. Deterrents such as noise makers and  In the mid-1980s gray wolves recolonized the Bow Valley in Banff National Park. They had been absent for 30 years due to systematic predator control hunting which began in 1850. Wolves filtered back to Banff and recolonized one zone of the Bow Valley in 1985 and another in 1991. A high level of human use surrounding a third zone at Banff townsite has deterred the wolves from that area. The wolves are important in controlling elk populations and improve the balance of the ecosystem. A routine park study to monitor the wolves in Banff has now grown into the Southern Rockies Canine Project – the largest wolf research project in North America. The estimated wolf population in Banff National Park and the surrounding areas is now 60–70 animals.

In the mid-1980s gray wolves recolonized the Bow Valley in Banff National Park. They had been absent for 30 years due to systematic predator control hunting which began in 1850. Wolves filtered back to Banff and recolonized one zone of the Bow Valley in 1985 and another in 1991. A high level of human use surrounding a third zone at Banff townsite has deterred the wolves from that area. The wolves are important in controlling elk populations and improve the balance of the ecosystem. A routine park study to monitor the wolves in Banff has now grown into the Southern Rockies Canine Project – the largest wolf research project in North America. The estimated wolf population in Banff National Park and the surrounding areas is now 60–70 animals.

The Trans-Canada Highway, passing through Banff, has been problematic, posing hazards for

The Trans-Canada Highway, passing through Banff, has been problematic, posing hazards for

In 1978, expansion of Sunshine Village ski resort was approved, with added parking, hotel expansion, and development of Goat's Eye Mountain. Implementation of this development proposal was delayed through the 1980s, while environmental assessments were conducted. In 1989, Sunshine Village withdrew its development proposal, in light of government reservations, and submitted a revised proposal in 1992. This plan was approved by the government, pending environmental review. Subsequently, the

In 1978, expansion of Sunshine Village ski resort was approved, with added parking, hotel expansion, and development of Goat's Eye Mountain. Implementation of this development proposal was delayed through the 1980s, while environmental assessments were conducted. In 1989, Sunshine Village withdrew its development proposal, in light of government reservations, and submitted a revised proposal in 1992. This plan was approved by the government, pending environmental review. Subsequently, the

While the ''National Parks Act'' and the 1988 amendment emphasize ecological integrity, in practice Banff has suffered from inconsistent application of the policies. In 1994, the Banff-Bow Valley Study was mandated by

While the ''National Parks Act'' and the 1988 amendment emphasize ecological integrity, in practice Banff has suffered from inconsistent application of the policies. In 1994, the Banff-Bow Valley Study was mandated by

national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

, established in 1885 as Rocky Mountains Park. Located in Alberta's Rocky Mountains, west of Calgary

Calgary ( ) is the largest city in the western Canadian province of Alberta and the largest metro area of the three Prairie Provinces. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806, makin ...

, Banff encompasses of mountainous terrain, with many glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s and ice field

An ice field (also spelled icefield) is a mass of interconnected valley glaciers (also called mountain glaciers or alpine glaciers) on a mountain mass with protruding rock ridges or summits. They are often found in the colder climates and highe ...

s, dense coniferous

Conifers are a group of cone-bearing seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single extant class, Pinopsida. All extant ...

forest, and alpine landscapes. The Icefields Parkway

Highway 93 is a north–south highway in Alberta, Canada. It is also known as the Banff-Windermere Parkway south of the Trans-Canada Highway ( Highway 1) and the Icefields Parkway north of the Trans-Canada Highway. It travels through ...

extends from Lake Louise, connecting to Jasper National Park

Jasper National Park is a national park in Alberta, Canada. It is the largest national park within Alberta's Rocky Mountains spanning . It was established as a national park in 1930 and declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984. Its locatio ...

in the north. Provincial forests and Yoho National Park

Yoho National Park ( ) is a National Parks of Canada, national park of Canada. It is located within the Canadian Rockies, Rocky Mountains along the western slope of the Continental Divide of the Americas in southeastern British Columbia, bordered ...

are neighbours to the west, while Kootenay National Park

Kootenay National Park is a national park of Canada located in southeastern British Columbia. The park consists of of the Canadian Rockies, including parts of the Kootenay and Park mountain ranges, the Kootenay River and the entirety of the Ve ...

is located to the south and Kananaskis Country

Kananaskis Country is a multi-use area west of Calgary, Alberta, Canada in the foothills and front ranges of the Canadian Rockies. The area is named for the Kananaskis River, which was named by John Palliser in 1858 after a Cree acquaintance. Cove ...

to the southeast. The main commercial centre of the park is the town of Banff, in the Bow River

The Bow River is a river in Alberta, Canada. It begins within the Canadian Rocky Mountains and winds through the Alberta foothills onto the prairies, where it meets the Oldman River, the two then forming the South Saskatchewan River. These w ...

valley.

The

The Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

was instrumental in Banff's early years, building the Banff Springs Hotel

The Fairmont Banff Springs, formerly and commonly known as the Banff Springs Hotel, is a historic hotel located in Banff, Alberta, Canada. The entire town including the hotel, is situated in Banff National Park, a national park managed by Park ...

and Chateau Lake Louise

The Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise is a Fairmont hotel on the eastern shore of Lake Louise, near Banff, Alberta. The original hotel was gradually developed at the turn of the 20th century by the Canadian Pacific Railway and was thus "kin" to its ...

, and attracting tourists through extensive advertising. In the early 20th century, roads were built in Banff, at times by war internees from World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and through Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

-era public works projects. Since the 1960s, park accommodations have been open all year, with annual tourism visits to Banff increasing to over 5 million in the 1990s. Millions more pass through the park on the Trans-Canada Highway

The Trans-Canada Highway ( French: ; abbreviated as the TCH or T-Can) is a transcontinental federal–provincial highway system that travels through all ten provinces of Canada, from the Pacific Ocean on the west coast to the Atlantic Ocean o ...

. As Banff has over three million visitors annually, the health of its ecosystem has been threatened. In the mid-1990s, Parks Canada

Parks Canada (PC; french: Parcs Canada),Parks Canada is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Parks Canada Agency (). is the agency of the Government of Canada which manages the country's 48 National Parks, th ...

responded by initiating a two-year study which resulted in management recommendations and new policies that aim to preserve ecological integrity.

Banff National Park has a subarctic climate

The subarctic climate (also called subpolar climate, or boreal climate) is a climate with long, cold (often very cold) winters, and short, warm to cool summers. It is found on large landmasses, often away from the moderating effects of an ocean, ge ...

with three ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) or ecozone (ecological zone) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of l ...

s, including montane

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is a crucial f ...

, subalpine

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is a crucial f ...

, and alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National Pa ...

. The forests are dominated by Lodgepole pine

''Pinus contorta'', with the common names lodgepole pine and shore pine, and also known as twisted pine, and contorta pine, is a common tree in western North America. It is common near the ocean shore and in dry montane forests to the subalpine, ...

at lower elevations and Engelmann spruce

''Picea engelmannii'', with the common names Engelmann spruce, white spruce, mountain spruce, and silver spruce, is a species of spruce native to western North America. It is mostly a high-altitude mountain tree but also appears in watered canyon ...

in higher ones below the treeline, above which is primarily rocks and ice. Mammal species such as the grizzly bear

The grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos horribilis''), also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

In addition to the mainland grizzly (''Ursus arctos horri ...

, cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') is a large Felidae, cat native to the Americas. Its Species distribution, range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mamm ...

, wolverine

The wolverine (), (''Gulo gulo''; ''Gulo'' is Latin for "gluttony, glutton"), also referred to as the glutton, carcajou, or quickhatch (from East Cree, ''kwiihkwahaacheew''), is the largest land-dwelling species of the family Mustelidae. It is ...

, elk

The elk (''Cervus canadensis''), also known as the wapiti, is one of the largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. The common ...

, bighorn sheep

The bighorn sheep (''Ovis canadensis'') is a species of sheep native to North America. It is named for its large horns. A pair of horns might weigh up to ; the sheep typically weigh up to . Recent genetic testing indicates three distinct subspec ...

and moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult mal ...

are found, along with hundreds of bird species. Reptiles and amphibians are also found but only a limited number of species have been recorded. The mountains are formed from sedimentary rocks which were pushed east over newer rock strata, between 80 and 55 million years ago. Over the past few million years, glaciers have at times covered most of the park, but today are found only on the mountain slopes though they include the Columbia Icefield

The Columbia Icefield is the largest ice field in North America's Rocky Mountains. Located within the Canadian Rocky Mountains astride the Continental Divide along the border of British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, the ice field lies partly in ...

, the largest uninterrupted glacial mass in the Rockies. Erosion from water and ice have carved the mountains into their current shapes.

History

Throughout its history, Banff National Park has been shaped by tension between conservationist and land exploitation interests. The park was established on November 25, 1885, as Banff Hot Springs Reserve, in response to conflicting claims over who discovered

Throughout its history, Banff National Park has been shaped by tension between conservationist and land exploitation interests. The park was established on November 25, 1885, as Banff Hot Springs Reserve, in response to conflicting claims over who discovered hot springs

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

there and who had the right to develop the hot springs for commercial interests. The conservationists prevailed when Prime Minister John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

set aside the hot springs as a small protected reserve, which was later expanded to include Lake Louise and other areas extending north to the Columbia Icefield

The Columbia Icefield is the largest ice field in North America's Rocky Mountains. Located within the Canadian Rocky Mountains astride the Continental Divide along the border of British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, the ice field lies partly in ...

.

Indigenous peoples

Archaeological evidence found at Vermilion Lakes indicates the first human activity in Banff to 10,300 B.P. Prior to European contact, the area that is now Banff National Park was home to many Indigenous Peoples, including the Stoney Nakoda,Ktunaxa

The Kutenai ( ), also known as the Ktunaxa ( ; ), Ksanka ( ), Kootenay (in Canada) and Kootenai (in the United States), are an indigenous people of Canada and the United States. Kutenai bands live in southeastern British Columbia, northern ...

, Tsuut'ina, Kainaiwa, Piikani, Siksika

The Siksika Nation ( bla, Siksiká) is a First Nation in southern Alberta, Canada. The name ''Siksiká'' comes from the Blackfoot words ''sik'' (black) and ''iká'' (foot), with a connector ''s'' between the two words. The plural form of ''Siks ...

, and Plains Cree . Indigenous Peoples utilized the area to hunt, fish, trade, travel, survey and practice culture. Many areas within Banff National Park are still known by their Stoney Nakoda names such as Lake Minnewanka

Lake Minnewanka () ("Water of the Spirits" in Nakoda) is a glacial lake located in the eastern area of Banff National Park in Canada, about northeast of the Banff townsite. The lake is long and deep, making it the 2nd longest lake in the mou ...

and the Waputik Range

The Waputik Range lies west of the upper Bow Valley, east of Bath Creek, and south of Balfour Creek in the Canadian Rockies. "Waputik" means "white goat" in Stoney. The range was named in 1884 by George Mercer Dawson of the Geological Survey of ...

. Cave and Basin served as an important cultural and spiritual site for the Stoney Nakoda.

With the admission of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

to Canada on July 20, 1871, Canada agreed to build a transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

. Construction of the railroad began in 1875, with Kicking Horse Pass

Kicking Horse Pass (el. ) is a high mountain pass across the Continental Divide of the Americas of the Canadian Rockies on the Alberta–British Columbia border, and lying within Yoho and Banff national parks. Divide Creek forks onto both sid ...

chosen, over the more northerly Yellowhead Pass

The Yellowhead Pass is a mountain pass across the Continental Divide of the Americas in the Canadian Rockies. It is located on the provincial boundary between the Canadian provinces of Alberta and British Columbia, and lies within Jasper Nat ...

, as the route through the Canadian Rockies. Ten years later, on November 7, 1885, the last spike was driven in Craigellachie, British Columbia

Craigellachie (pronounced ) is a locality in British Columbia, located several kilometres to the west of the Eagle Pass summit between Sicamous and Revelstoke. Craigellachie is the site of a tourist stop on the Trans-Canada Highway between Salm ...

.

Rocky Mountains Park established

With conflicting claims over the discovery of hot springs in Banff, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald decided to set aside a small reserve of around the hot springs at Cave and Basin as a public park known as the ''Banff Hot Springs Reserve'' in 1885. Under the ''Rocky Mountains Park Act

The ''Rocky Mountains Park Act'' was enacted on June 23, 1887, by the Parliament of Canada, establishing Banff National Park which was then known as "Rocky Mountains Park". The act was modelled on the '' Yellowstone Park Act'' passed by the Un ...

'', enacted on June 23, 1887, the park was expanded to and named ''Rocky Mountains Park''. This was Canada's first national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

, and the third established in North America, after Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

and Mackinac National Park

Mackinac National Park was a United States national park that existed from 1875 to 1895 on Mackinac Island in northern Michigan, making it the second U.S. national park after Yellowstone National Park. The park was created in response to the gro ...

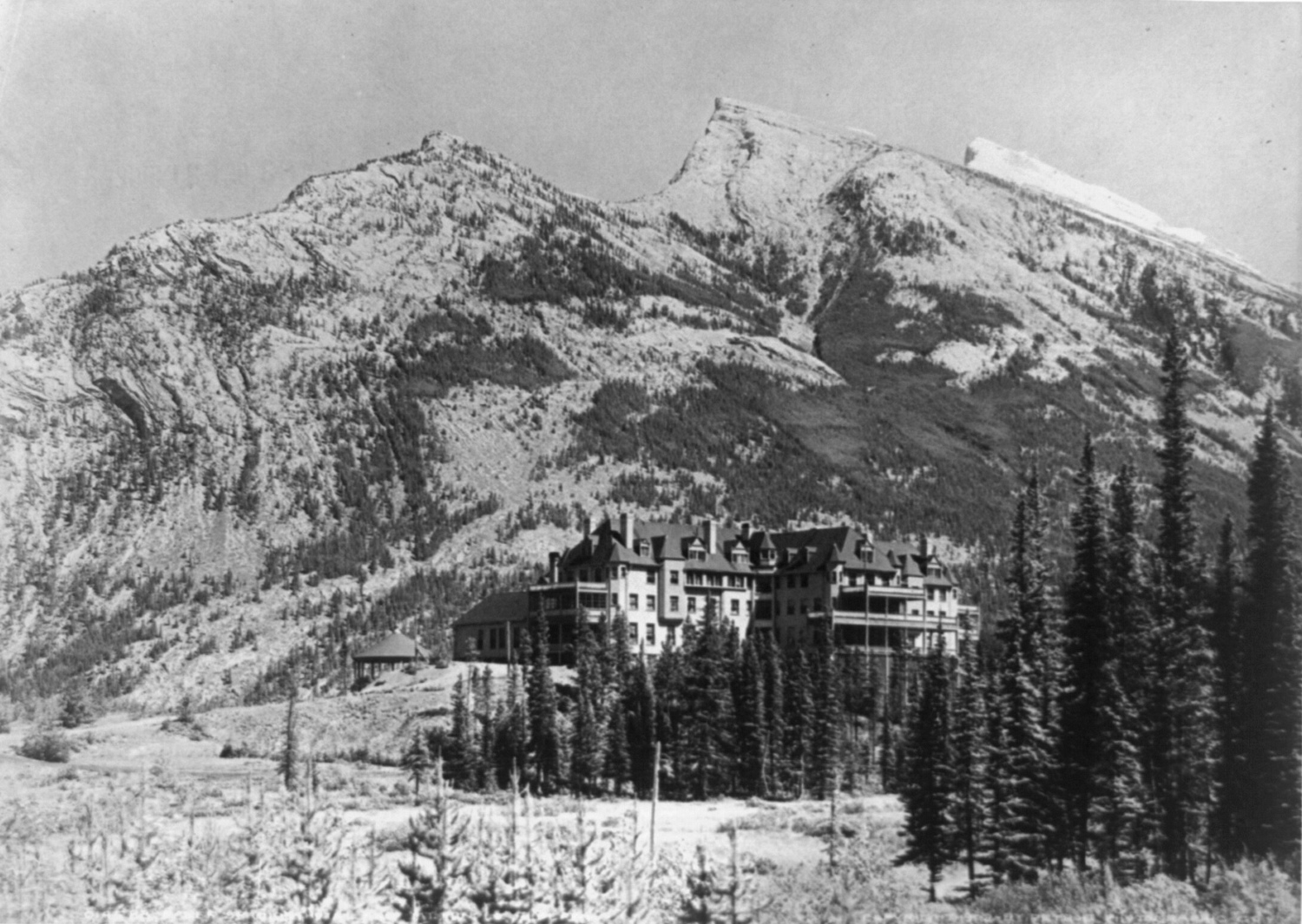

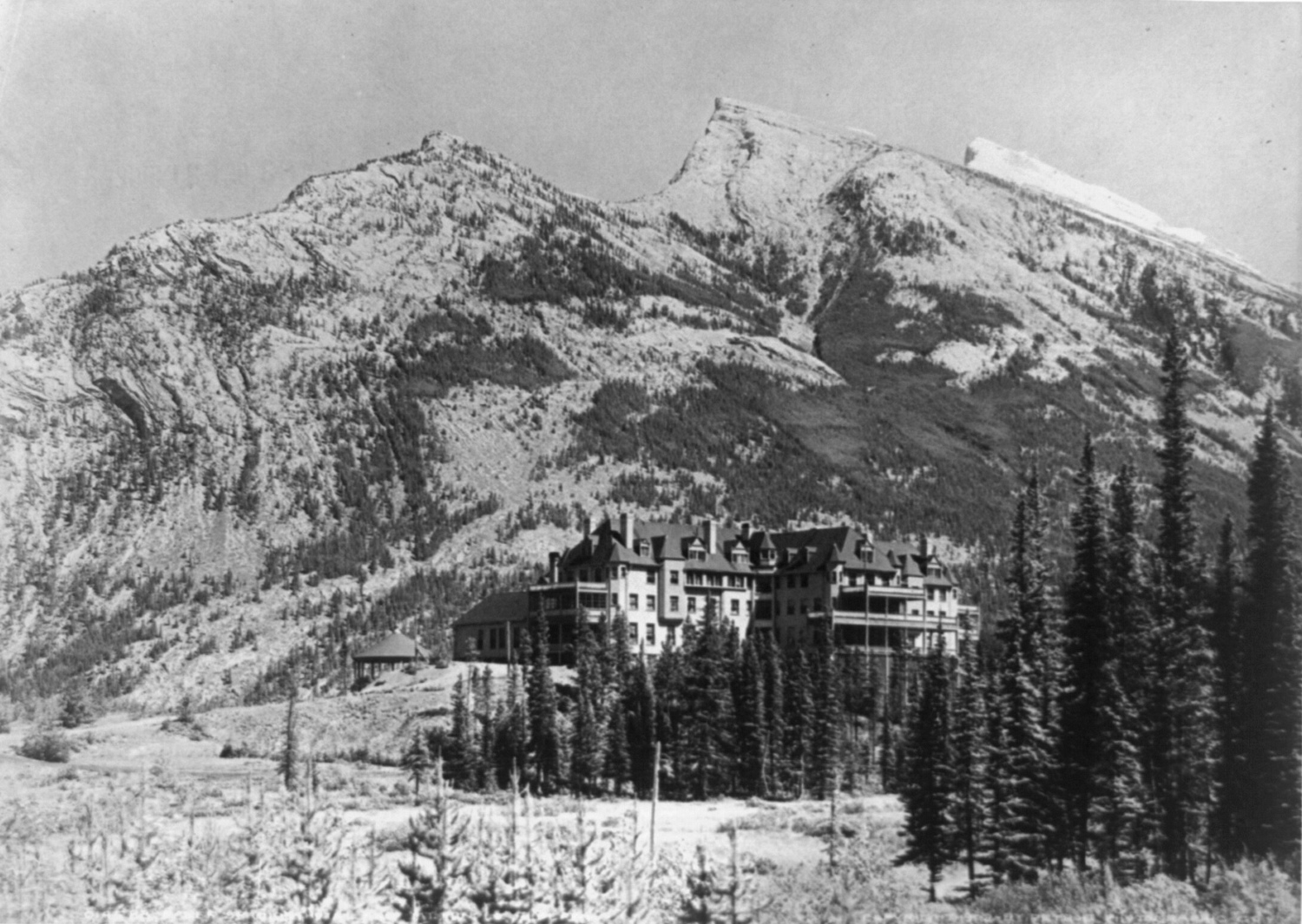

s. The Canadian Pacific Railway built the Banff Springs Hotel

The Fairmont Banff Springs, formerly and commonly known as the Banff Springs Hotel, is a historic hotel located in Banff, Alberta, Canada. The entire town including the hotel, is situated in Banff National Park, a national park managed by Park ...

and Lake Louise Chalet to attract tourists and increase the number of rail passengers.

The Stoney Nakoda

The Stoney Nakoda First Nation

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

were removed from Banff National Park between the years 1890 and 1920. The park was designed to appeal to sportsmen, and tourists. The exclusionary policy met the goals of sports hunting, tourism, and game conservation, as well as of those attempting to "civilize" the First Nations of the area.

Early on, Banff was popular with wealthy European and American tourists, the former of which arrived in Canada via trans-Atlantic luxury liner and continued westward on the railroad. Some visitors participated in mountaineering activities, often hiring local guides. Guides Jim and Bill Brewster founded one of the first outfitters in Banff. From 1906, the Alpine Club of Canada

The Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) is an amateur athletic association with its national office in Canmore, Alberta that has been a focal point for Canadian mountaineering since its founding in 1906. The club was co-founded by Arthur Oliver Wheeler ...

organized climbs, hikes and camps in the park.

By 1911, Banff was accessible by automobile from Calgary. Beginning in 1916, the Brewsters offered motorcoach tours of Banff. In 1920, access to Lake Louise by road was available, and the Banff-Windermere Road opened in 1923 to connect Banff with British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

.

In 1902, the park was expanded to cover , encompassing areas around Lake Louise, and the Bow,

In 1902, the park was expanded to cover , encompassing areas around Lake Louise, and the Bow, Red Deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or hart, and a female is called a hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, and parts of wes ...

, Kananaskis, and Spray

Spray or spraying commonly refer to:

* Spray (liquid drop)

** Aerosol spray

** Blood spray

** Hair spray

** Nasal spray

** Pepper spray

** PAVA spray

** Road spray or tire spray, road debris kicked up from a vehicle tire

** Sea spray, refers to ...

rivers. Bowing to pressure from grazing and logging

Logging is the process of cutting, processing, and moving trees to a location for transport. It may include skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or logs onto trucks or skeleton cars.

Logging is the beginning of a supply chain ...

interests, the size of the park was reduced in 1911 to , eliminating many eastern foothills areas from the park. Park boundaries changed several more times up until 1930, when the area of Banff was fixed at , with the passage of the '' National Parks Act''. The ''Act'', which took effect May 30, 1930, also renamed the park ''Banff National Park'', named for the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

station, which in turn was named after the Banffshire

Banffshire ; sco, Coontie o Banffshire; gd, Siorrachd Bhanbh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. The county town is Banff, although the largest settlement is Buckie to the west. It borders the Moray ...

region in Scotland. With the construction of a new east gate in 1933, Alberta transferred to the park. This, along with other minor changes in the park boundaries in 1949, set the area of the park at .

Coal mining

In 1877, theFirst Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

of the area signed Treaty 7

Treaty 7 is an agreement between the Crown and several, mainly Blackfoot, First Nation band governments in what is today the southern portion of Alberta. The idea of developing treaties for Blackfoot lands was brought to Blackfoot chief Crowfo ...

, which gave Canada rights to explore the land for resources. At the beginning of the 20th century, coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

was mined near Lake Minnewanka

Lake Minnewanka () ("Water of the Spirits" in Nakoda) is a glacial lake located in the eastern area of Banff National Park in Canada, about northeast of the Banff townsite. The lake is long and deep, making it the 2nd longest lake in the mou ...

in Banff. For a brief period, a mine operated at Anthracite but was shut down in 1904. The Bankhead mine, at Cascade Mountain, was operated by the Canadian Pacific Railway from 1903 to 1922. In 1926, the town was dismantled, with many buildings moved to the town of Banff and elsewhere.

Internment and work camps

DuringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, immigrant

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

s from Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

were sent to Banff to work in internment camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

s. The main camp was located at Castle Mountain

Castle Mountain ( bla, Miistukskoowa) is a mountain located within Banff National Park in the Canadian Rockies, approximately halfway between Banff and Lake Louise. It is the easternmost mountain of the Main Ranges in the Bow Valley and sits ...

, and was moved to Cave and Basin during winter. Much early infrastructure and road construction was done by men of various Slavic origins although Ukrainians constituted a majority of those held in Banff. Historical plaques and a statue erected by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

__NOTOC__

The Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association (UCCLA) (french: L'Association ukrainienne-canadienne des droits civils (''AU-CDC'')) is a Ukrainian organization in Canada. Established in 1986 after the Civil Liberties Commission (aff ...

commemorate those interned at Castle Mountain, and at Cave and Basin National Historic Site where an interpretive pavilion dealing with Canada's first national internment operations opened in September 2013.

In 1931, the

In 1931, the Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown ...

enacted the ''Unemployment and Farm Relief Act

The ''Unemployment and Farm Relief Act'' - ''An Act to confer certain powers upon the Governor in Council in respect to unemployment and farm relief, and the maintenance of peace, order and good government in Canada,'' (french: Loi remédiant au ...

'' which provided public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and constructed by the government, for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, sc ...

projects in the national parks

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. In Banff, workers constructed a new bathhouse and pool at Upper Hot Springs, to supplement Cave and Basin. Other projects involved road building in the park, tasks around the Banff townsite and construction of a highway connecting Banff and Jasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases,Kostov, R. I. 2010. Review on the mineralogical systematics of jasper and related rocks. – Archaeometry Workshop, 7, 3, 209-213PDF/ref> ...

. In 1934, the'' Public Works Construction Act'' was passed, providing continued funding for the public works projects. New projects included construction of a new registration facility at Banff's east gate and construction of an administrative building in Banff. By 1940, the Icefields Parkway reached the Columbia Icefield area of Banff and connected Banff and Jasper. Most of the infrastructure present in the national park dates from public work projects enacted during the Great Depression.

Alternative service

Alternative civilian service, also called alternative services, civilian service, non-military service, and substitute service, is a form of national service performed in lieu of military conscription for various reasons, such as conscientious ...

camps for conscientious objector

A conscientious objector (often shortened to conchie) is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion. The term has also been extended to object ...

s were set up in Banff during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, with camps located at Lake Louise, Stoney Creek, and Healy Creek. These camps were largely populated by Mennonites

Mennonites are groups of Anabaptist Christian church communities of denominations. The name is derived from the founder of the movement, Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland. Through his writings about Reformed Christianity during the Radic ...

from Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

.

Winter tourism

Winter tourism in Banff began in February 1917, with the first Banff Winter Carnival. It was marketed to a regional middle class audience, and became the centerpiece of local boosters aiming to attract visitors, which were a low priority for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The carnival featured a large ice palace, which in 1917 was built by World War I internees. Carnival events includedcross-country skiing

Cross-country skiing is a form of skiing where skiers rely on their own locomotion to move across snow-covered terrain, rather than using ski lifts or other forms of assistance. Cross-country skiing is widely practiced as a sport and recreation ...

, ski jumping

Ski jumping is a winter sport in which competitors aim to achieve the farthest jump after sliding down on their skis from a specially designed curved ramp. Along with jump length, competitor's aerial style and other factors also affect the final ...

, curling

Curling is a sport in which players slide stones on a sheet of ice toward a target area which is segmented into four concentric circles. It is related to bowls, boules, and shuffleboard. Two teams, each with four players, take turns sliding ...

, snowshoe

Snowshoes are specialized outdoor gear for walking over snow. Their large footprint spreads the user's weight out and allows them to travel largely on top of rather than through snow. Adjustable bindings attach them to appropriate winter footwe ...

, and skijoring

Skijoring (pronounced ) (Skijouring in British English) is a winter sport in which a person on skis is pulled by a horse, a dog (or dogs), another animal, or a motor vehicle. The name is derived from the Norwegian word ''skikjøring'', meaning "s ...

. In the 1930s, the first downhill ski

A ski is a narrow strip of semi-rigid material worn underfoot to glide over snow. Substantially longer than wide and characteristically employed in pairs, skis are attached to ski boots with ski bindings, with either a free, lockable, or partial ...

resort, Sunshine Village

Banff Sunshine Village (formerly Sunshine Village) is a ski resort in western Canada, located on the Continental Divide of the Canadian Rockies within Banff National Park in Alberta and Mt Assiniboine Provincial Park in British Columbia. It is on ...

, was developed by the Brewsters. Mount Norquay

Mt. Norquay is a mountain and ski resort in Banff National Park, Canada that lies directly northwest of the Town of Banff. The regular ski season starts early December and ends mid-April. Mount Norquay is one of three major ski resorts located i ...

ski area was also developed during the 1930s, with the first chair lift

An elevated passenger ropeway, or chairlift, is a type of aerial lift, which consists of a continuously circulating steel wire rope loop strung between two end terminals and usually over intermediate towers, carrying a series of chairs. They ...

installed there in 1948.

Since 1968, when the Banff Springs Hotel was winterized, Banff has been a year-round destination. In the 1950s, the Trans-Canada Highway was constructed, providing another transportation corridor through the Bow Valley, making the park more accessible.

Canada launched several bids to host the Winter Olympics

The Winter Olympic Games (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques d'hiver) is a major international multi-sport event held once every four years for sports practiced on snow and ice. The first Winter Olympic Games, the 1924 Winter Olympics, were h ...

in Banff, with the first bid for the 1964 Winter Olympics

The 1964 Winter Olympics, officially known as the IX Olympic Winter Games (german: IX. Olympische Winterspiele) and commonly known as Innsbruck 1964 ( bar, Innschbruck 1964, label=Austro-Bavarian), was a winter multi-sport event which was celebr ...

, which were eventually awarded to Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; bar, Innschbruck, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian ) is the capital of Tyrol (state), Tyrol and the List of cities and towns in Austria, fifth-largest city in Austria. On the Inn (river), River Inn, at its junction with the ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. Canada narrowly lost a second bid, for the 1968 Winter Olympics

The 1968 Winter Olympics, officially known as the X Olympic Winter Games (french: Les Xes Jeux olympiques d'hiver), were a winter multi-sport event held from 6 to 18 February 1968 in Grenoble, France. Thirty-seven countries participated. Frenchm ...

, which were awarded to Grenoble

lat, Gratianopolis

, commune status = Prefecture and commune

, image = Panorama grenoble.png

, image size =

, caption = From upper left: Panorama of the city, Grenoble’s cable cars, place Saint- ...

, France. Once again, Banff launched a bid to host the 1972 Winter Olympics

The 1972 Winter Olympics, officially the and commonly known as Sapporo 1972 ( ja, 札幌1972), was a winter multi-sport event held from February 3 to 13, 1972, in Sapporo, Japan. It was the first Winter Olympic Games to take place outside Europe ...

, with plans to hold the Olympics at Lake Louise. The 1972 bid was controversial, as environmental lobby groups strongly opposed the bid, which had sponsorship from Imperial Oil

Imperial Oil Limited (French: ''Compagnie Pétrolière Impériale Ltée'') is a Canadian petroleum company. It is Canada's second-biggest integrated oil company. It is majority owned by American oil company ExxonMobil with around 69.6 percent ...

. Bowing to pressure, Jean Chrétien

Joseph Jacques Jean Chrétien (; born January 11, 1934) is a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 20th prime minister of Canada from 1993 to 2003.

Born and raised in Shawinigan Falls, Quebec, Chrétien is a law graduate from Uni ...

, then the Minister of Environment, the government department responsible for Parks Canada, withdrew support for the bid, which was eventually lost to Sapporo

( ain, サッ・ポロ・ペッ, Satporopet, lit=Dry, Great River) is a city in Japan. It is the largest city north of Tokyo and the largest city on Hokkaido, the northernmost main island of the country. It ranks as the fifth most populous city ...

, Japan. When nearby Calgary

Calgary ( ) is the largest city in the western Canadian province of Alberta and the largest metro area of the three Prairie Provinces. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806, makin ...

hosted the 1988 Winter Olympics

The 1988 Winter Olympics, officially known as the XV Olympic Winter Games (french: XVes Jeux olympiques d'hiver) and commonly known as Calgary 1988 ( bla, Mohkínsstsisi 1988; sto, Wîchîspa Oyade 1988 or ; cr, Otôskwanihk 1998/; srs, Guts� ...

, the cross-country ski events were held at the Canmore Nordic Centre Provincial Park at Canmore, Alberta

Canmore is a town in Alberta, Canada, located approximately west of Calgary near the southeast boundary of Banff National Park. It is located in the Bow Valley within Alberta's Rocky Mountains. The town shares a border with Kananaskis Country ...

, located just outside the eastern gates of Banff National Park on the Trans-Canada Highway

The Trans-Canada Highway ( French: ; abbreviated as the TCH or T-Can) is a transcontinental federal–provincial highway system that travels through all ten provinces of Canada, from the Pacific Ocean on the west coast to the Atlantic Ocean o ...

.

Conservation

Since the original Rocky Mountains Park Act, subsequent acts and policies placed greater emphasis on conservation. With public sentiment tending towards environmentalism,Parks Canada

Parks Canada (PC; french: Parcs Canada),Parks Canada is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Parks Canada Agency (). is the agency of the Government of Canada which manages the country's 48 National Parks, th ...

issued major new policy in 1979, which emphasized conservation. The ''National Parks Act'' was amended in 1988, which made preserving ecological integrity

Planetary boundaries is a concept highlighting human-caused perturbations of Earth systems making them relevant in a way not accommodated by the environmental boundaries separating the three ages within the Holocene epoch. Crossing a planetary ...

the first priority in all park management decisions. The ''Act'' also required each park to produce a management plan, with greater public participation.

In 1984, Banff was declared a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

, Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site

The Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site is located in the Canadian Rockies. It consists of seven contiguous parks including four national parks:

* Banff

*Jasper

*Kootenay

* Yoho

and three British Columbia provincial parks:

*Hamber ...

, together with the other national and provincial park

Ischigualasto Provincial Park

A provincial park (or territorial park) is a park administered by one of the provinces of a country, as opposed to a national park. They are similar to state parks in other countries. They are typically open to the ...

s that form the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks

The Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site is located in the Canadian Rockies. It consists of seven contiguous parks including four national parks:

* Banff

*Jasper

* Kootenay

* Yoho

and three British Columbia provincial parks:

* Hamb ...

, for the mountain landscapes containing mountain peaks, glaciers, lakes, waterfalls, canyon

A canyon (from ; archaic British English spelling: ''cañon''), or gorge, is a deep cleft between escarpments or cliffs resulting from weathering and the erosion, erosive activity of a river over geologic time scales. Rivers have a natural tenden ...

s and limestone caves as well as fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

beds. With this designation came added obligations for conservation.

During the 1980s, Parks Canada moved to privatize many park services such as golf courses, and added user fees for use of other facilities and services to help deal with budget cuts. In 1990, the town of Banff was incorporated, giving local residents more say regarding any proposed developments.

In the 1990s, development plans for the park, including expansion at Sunshine Village, were under fire with lawsuits filed by Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society

The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) (french: la Société pour la nature et les parcs du Canada (SNAP)) was founded in 1963 to help protect Canada's wilderness.

Overview

CPAWS was initially known as the National and Provincial Pa ...

(CPAWS). In the mid-1990s, the Banff-Bow Valley Study was initiated to find ways to better address environmental concerns, and issues relating to development in the park.

Geography

Banff National Park is located in the Rocky Mountains on Alberta's western border with British Columbia in the

Banff National Park is located in the Rocky Mountains on Alberta's western border with British Columbia in the Alberta Mountain forests

The Alberta Mountain forests are a temperate coniferous forests ecoregion of Western Canada, as defined by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) categorization system.

Setting

This ecoregion covers the grand Rocky Mountains of Alberta including the east ...

ecoregion. By road, the town of Banff is west of Calgary and southwest of Edmonton

Edmonton ( ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Alberta. Edmonton is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Alberta's central region. The city ancho ...

. Jasper National Park borders Banff National Park to the north, while Yoho National Park

Yoho National Park ( ) is a National Parks of Canada, national park of Canada. It is located within the Canadian Rockies, Rocky Mountains along the western slope of the Continental Divide of the Americas in southeastern British Columbia, bordered ...

is to the west and Kootenay National Park

Kootenay National Park is a national park of Canada located in southeastern British Columbia. The park consists of of the Canadian Rockies, including parts of the Kootenay and Park mountain ranges, the Kootenay River and the entirety of the Ve ...

is to the south. Kananaskis Country

Kananaskis Country is a multi-use area west of Calgary, Alberta, Canada in the foothills and front ranges of the Canadian Rockies. The area is named for the Kananaskis River, which was named by John Palliser in 1858 after a Cree acquaintance. Cove ...

, which includes Bow Valley Wildland Provincial Park, Spray Valley Provincial Park

Spray Valley Provincial Park is a provincial park located east of the Rocky Mountains, along the Spray River in western Alberta, Canada.

The park is part of the Kananaskis Country park system (along with Bluerock Wildland Provincial Park, Bow Va ...

, and Peter Lougheed Provincial Park

Peter Lougheed Provincial Park is a provincial park located in Alberta, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the A ...

, is located to the south and east of Banff.

The Trans-Canada Highway

The Trans-Canada Highway ( French: ; abbreviated as the TCH or T-Can) is a transcontinental federal–provincial highway system that travels through all ten provinces of Canada, from the Pacific Ocean on the west coast to the Atlantic Ocean o ...

passes through Banff National Park, from the eastern boundary near Canmore, through the towns of Banff and Lake Louise, and into Yoho National Park in British Columbia. The Banff townsite is the main commercial centre in the national park. The village of Lake Louise is located at the junction of the Trans-Canada Highway and the Icefields Parkway, which extends north to the Jasper townsite.

Banff

Banff, established in 1885, is the main commercial centre in Banff National Park, as well as a centre for cultural activities. Banff is home to several cultural institutions, including theBanff Centre

Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, formerly known as The Banff Centre (and previously The Banff Centre for Continuing Education), located in Banff, Alberta, was established in 1933 as the Banff School of Drama. It was granted full autonomy as ...

, the Whyte Museum, the Buffalo Nations Luxton Museum, Cave and Basin National Historic Site

The Cave and Basin National Historic Site of Canada is located in the town of Banff, Alberta, within the Canadian Rocky Mountains, at the site of natural thermal mineral springs around which Canada's first national park, Banff National Park, w ...

, and several art galleries

An art gallery is a room or a building in which visual art is displayed. In Western cultures from the mid-15th century, a gallery was any long, narrow covered passage along a wall, first used in the sense of a place for art in the 1590s. The lon ...

. Throughout its history, Banff has hosted many annual events, including Banff Indian Days which began in 1889, and the Banff Winter Carnival. Since 1976, The Banff Centre has organized the Banff Mountain Film Festival The Banff Centre Mountain Film Festival is an international film competition and annual presentation of films and documentaries about mountain culture, sports, environment and adventure & exploration. It was launched in 1976 as ''The Banff Festival ...

. In 1990, Banff incorporated as a town of Alberta, though still subject to the ''National Parks Act'' and federal authority in regards to planning and development. In its 2014 census, the town of Banff had a permanent population of 8,421 as well as 965 non-permanent residents for a total population of 9,386. The Bow River flows through the town of Banff, with the Bow Falls

Bow Falls is a major waterfall on the Bow River, Alberta just before the junction of it and the Spray River. They are located near the Banff Springs Hotel and golf course on the left-hand side of River Road.

The falls are within walking distance ...

located on the outskirts of town.

Lake Louise

Lake Louise, a hamlet located northwest of the town of Banff, is home to the landmark

Lake Louise, a hamlet located northwest of the town of Banff, is home to the landmark Chateau Lake Louise

The Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise is a Fairmont hotel on the eastern shore of Lake Louise, near Banff, Alberta. The original hotel was gradually developed at the turn of the 20th century by the Canadian Pacific Railway and was thus "kin" to its ...

at the edge of Lake Louise. Located from Lake Louise, Moraine Lake

Moraine Lake is a glacially fed lake in Banff National Park, outside the hamlet of Lake Louise, Alberta, Canada. It is situated in the Valley of the Ten Peaks, at an elevation of approximately . The lake has a surface area of .

The lake, bein ...

provides a scenic vista of the Valley of the Ten Peaks

Valley of the Ten Peaks (french: Vallée des Dix Pics) is a valley in Banff National Park in Alberta, Canada, which is crowned by ten notable peaks and also includes Moraine Lake. The valley can be reached by following the Moraine Lake road near ...

. This scene was pictured on the back of the $20 Canadian banknote, in the 1969–1979 ("Scenes of Canada") series. The Lake Louise Mountain Resort

The Lake Louise Ski Resort & Summer Gondola is a ski resort in western Canada, located in Banff National Park near the village of Lake Louise, Alberta. Located west of Banff, Lake Louise is one of three major ski resorts within Banff National P ...

is also located near the village. Lake Louise is one of the most visited lakes in the world and is framed to the southwest by the Mount Victoria Glacier.

Icefields Parkway

The Icefields Parkway is a road connecting Lake Louise to Jasper, Alberta. The Parkway originates at Lake Louise, and extends north up the Bow Valley, pastHector Lake

Hector Lake is a small glacial lake in western Alberta, Canada. It is located on the Bow River, in the Waputik Range of the Canadian Rockies.

It is named after James Hector, a geologist and naturalist with the Palliser Expedition.

The ...

, which is the largest natural lake in the park. Other scenic lakes near the parkway include Bow Lake, and Peyto Lake

Peyto Lake ( ) is a glacier-fed lake in Banff National Park in the Canadian Rockies. The lake itself is near the Icefields Parkway. It was named for Bill Peyto, an early trail guide and trapper in the Banff area.

The lake is formed in a valley of ...

s, both north of Hector Lake. The Parkway then crosses Bow Summit (), and follows the Mistaya River to Saskatchewan Crossing, where it converges with the Howse and North Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows eventual ...

. Bow Summit is the highest elevation crossed by a public road in Canada.

The North Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows eventual ...

flows east from Saskatchewan Crossing, out of Banff, into what is known as David Thompson Country, and onto Edmonton. The David Thompson Highway #redirectAlberta Highway 11

David Thompson Highway #redirectAlberta Highway 11

Alberta Provincial Highway No. 11, commonly referred to as Highway 11 and officially named the David Thompson Highway, is a provincial highway in central A ...

follows the North Saskatchewan River, past the man-made Abraham Lake

Abraham Lake, also known as Lake Abraham, is an artificial lake and Alberta's largest reservoir. It is located in the " Kootenay Plains area of the Canadian Rockies' front range", on the North Saskatchewan River in western Alberta, Canada.

Descr ...

, and through David Thompson Country.

North of Saskatchewan Crossing, the Icefields Parkway follows the North Saskatchewan River up to the Columbia Icefield

The Columbia Icefield is the largest ice field in North America's Rocky Mountains. Located within the Canadian Rocky Mountains astride the Continental Divide along the border of British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, the ice field lies partly in ...

. The Parkway crosses into Jasper National Park at Sunwapta Pass at in elevation, and continues on from there to the Jasper townsite.

Geology

The

The Canadian Rockies

The Canadian Rockies (french: Rocheuses canadiennes) or Canadian Rocky Mountains, comprising both the Alberta Rockies and the British Columbian Rockies, is the Canadian segment of the North American Rocky Mountains. It is the easternmost part ...

consist of several northwest–southeast trending ranges. Two main mountain ranges are within the park, each consisting of numerous subranges. The western border of the park follows the crest of the Main Ranges (also known as the ''Park Ranges''), which is also the continental divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

. The Main Ranges in Banff National Park include from north to south, the Waputik, Bow and Blue Range

The Blue Range is a mountain range of the Canadian Rockies, located on the Continental Divide of the Americas, Continental Divide in Banff National Park, Canada. The range was so named on account of its blueish colour when viewed from afar. Mount ...

s. The high peaks west of Lake Louise are part of the Bow Range. The eastern border of the park includes all of the Front Ranges

The Front Ranges are a group of mountain ranges in the Canadian Rockies of eastern British Columbia and western Alberta, Canada. It is lowest and the easternmost of the three main subranges of the Continental Ranges, located east of the Bull and ...

consisting of from north to south, the Palliser, Sawback and Sundance Range

The Sundance Range is a mountain range in the Canadian Rockies, south of the town of Banff. It is located on the Continental Divide, which forms the boundary between British Columbia and Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces ...

s. The Banff townsite is located in the Front Ranges. Just outside of the park to the east lie the foothills that extend from Canmore at the eastern entrance of the park eastward into the Great Plains. Well west of the park, the Western Ranges of the Rockies pass through Yoho and Kootenay National Parks. Though the tallest peak entirely within the park is Mount Forbes

Mount Forbes is the seventh tallest mountain in the Canadian Rockies and the tallest within the boundaries of Banff National Park. It is located in southwestern Alberta, southwest of the Saskatchewan River Crossing in Banff. The mountain was ...

at , Mount Assiniboine

Mount Assiniboine, also known as Assiniboine Mountain, is a pyramidal peak mountain located on the Great Divide, on the British Columbia/Alberta border in Canada.

At , it is the highest peak in the Southern Continental Ranges of the Canadian Ro ...

on the Banff-Mount Assiniboine Provincial Park

Mount Assiniboine Provincial Park is a provincial park in British Columbia, Canada, located around Mount Assiniboine.

History

The park was established 1922. Some of the more recent history that is explorable within the park include Wheeler's Won ...

border is slightly higher at .

The Canadian Rockies are composed of sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

, including shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especial ...

, sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

, dolomite Dolomite may refer to:

*Dolomite (mineral), a carbonate mineral

*Dolomite (rock), also known as dolostone, a sedimentary carbonate rock

*Dolomite, Alabama, United States, an unincorporated community

*Dolomite, California, United States, an unincor ...

and limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

. The vast majority of geologic formation

A geological formation, or simply formation, is a body of rock having a consistent set of physical characteristics ( lithology) that distinguishes it from adjacent bodies of rock, and which occupies a particular position in the layers of rock exp ...

s in Banff range in age from Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of the ...

to the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

periods (600–145 m.y.a.). However, rocks as young as the lower Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

(145–66 m.y.a.) can be found near the east entrance and on Cascade Mountain above the Banff townsite. These sedimentary rocks formed at the bottom of shallow seas between 600 and 175 m.y.a. and were pushed east during the Laramide orogeny

The Laramide orogeny was a time period of mountain building in western North America, which started in the Late Cretaceous, 70 to 80 million years ago, and ended 35 to 55 million years ago. The exact duration and ages of beginning and end of the o ...

. Mountain building in Banff National Park ended approximately 55 m.y.a.

The Canadian Rockies may have risen up to approximately 70 m.y.a. Once mountain formation ceased, erosion carved the mountains into their present rugged shape. The erosion was first due to water, then was greatly accelerated by the Quaternary glaciation

The Quaternary glaciation, also known as the Pleistocene glaciation, is an alternating series of glacial and interglacial periods during the Quaternary period that began 2.58 Ma (million years ago) and is ongoing. Although geologists describe ...

2.5 million years ago. Glacial landform

Glacial landforms are landforms created by the action of glaciers. Most of today's glacial landforms were created by the movement of large ice sheets during the Quaternary glaciations. Some areas, like Fennoscandia and the southern Andes, have ...

s dominate Banff's geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or n ...

, with examples of all classic glacial forms, including cirque

A (; from the Latin word ') is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic , meaning a pot or cauldron) and (; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landform ...

s, arête

An arête ( ) is a narrow ridge of rock which separates two valleys. It is typically formed when two glaciers erode parallel U-shaped valleys. Arêtes can also form when two glacial cirques erode headwards towards one another, although frequen ...

s, hanging valley

A valley is an elongated low area often running between hills or mountains, which will typically contain a river or stream running from one end to the other. Most valleys are formed by erosion of the land surface by rivers or streams ove ...

s, moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris (regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice shee ...

s, and U-shaped valley

U-shaped valleys, also called trough valleys or glacial troughs, are formed by the process of glaciation. They are characteristic of mountain glaciation in particular. They have a characteristic U shape in cross-section, with steep, straight s ...

s. The pre-existing structure left over from mountain-building strongly guided glacial erosion: mountains in Banff include complex, irregular, anticlinal Anticlinal may refer to:

*Anticline, in structural geology, an anticline is a fold that is convex up and has its oldest beds at its core.

*Anticlinal, in stereochemistry, a torsion angle between 90° to 150°, and –90° to –150°; see Alkane_st ...

, synclinal, castellate, dogtooth, and sawback mountains.

Many of the mountain ranges trend northwest to southeast, with sedimentary layering dipping down to the west at 40–60 degrees. This leads to dip slope

A dip slope is a topographic (geomorphic) surface which slopes in the same direction, and often by the same amount, as the true dip or apparent dip of the underlying strata.Jackson, JA, J Mehl and K Neuendorf (2005) ''Glossary of Geology.'' Ame ...

landforms, with generally steeper east and north faces, and trellis drainage, where rivers and old glacial valleys followed the weaker layers in the rocks as they were relatively easily weathered and eroded.

Classic examples are found at the Banff townsite proper: Mount Rundle

Mount Rundle is a mountain in Canada's Banff National Park overlooking the towns of Banff and Canmore, Alberta. The Cree name was ''Waskahigan Watchi'' or house mountain.

In 1858 John Palliser renamed the mountain after Reverend Robert Rundle ...

is a classic dip slope mountain. Just to the north of the Banff townsite, Castle Mountain

Castle Mountain ( bla, Miistukskoowa) is a mountain located within Banff National Park in the Canadian Rockies, approximately halfway between Banff and Lake Louise. It is the easternmost mountain of the Main Ranges in the Bow Valley and sits ...

is composed of numerous Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized C with bar, Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million ...

age rock formations. The uppermost section of the peak consists of relatively harder dolomite from the Eldon Formation. Below that lies the less dense shales of the Stephen Formation

The Stephen Formation is a geologic formation exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia and Alberta, on the western edge of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. It consists of shale, thin-bedded limestone, and siltstone that was deposite ...

and the lowest exposed cliffs are limestones of the Cathedral Formation. Dogtooth mountains, such as Mount Louis

Mount Louis is a mountain summit located in southeast Banff National Park in Alberta, Canada. It is part of the Sawback Range which is a subset of the Canadian Rockies.

The mountain was named in 1886 after Louis B. Stewart who surveyed in the ...

, exhibit sharp, jagged slopes. The Sawback Range, which consists of nearly vertical dipping sedimentary layers, has been eroded by cross gullies

A gully is a landform created by running water, mass movement, or commonly a combination of both eroding sharply into soil or other relatively erodible material, typically on a hillside or in river floodplains or terraces. Gullies resemble lar ...

. The erosion of these almost vertical layers of rock strata in the Sawback Range has resulted in formations that appear like the teeth on a saw blade. Erosion and deposition of higher elevation rock layers has resulted in scree

Scree is a collection of broken rock fragments at the base of a cliff or other steep rocky mass that has accumulated through periodic rockfall. Landforms associated with these materials are often called talus deposits. Talus deposits typically ha ...

deposits at the lowest elevations of many of the mountains.

Glaciers and icefields

Banff National Park has numerous large glaciers and icefields, 100 of which can be observed from theIcefields Parkway

Highway 93 is a north–south highway in Alberta, Canada. It is also known as the Banff-Windermere Parkway south of the Trans-Canada Highway ( Highway 1) and the Icefields Parkway north of the Trans-Canada Highway. It travels through ...

. Small cirque glacier

A cirque glacier is formed in a cirque, a bowl-shaped depression on the side of or near mountains. Snow and ice accumulation in corries often occurs as the result of avalanching from higher surrounding slopes.

If a cirque glacier advances far enou ...

s are fairly common in the Main Ranges, situated in depressions on the side of many mountains. As with the majority of mountain glaciers around the world, the glaciers in Banff are retreating. While Peyto Glacier

__NOTOC__

The Peyto Glacier is situated in the Canadian Rockies in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada, approximately northwest of the town of Banff, and can be accessed from the Icefields Parkway. Geography

Peyto Glacier is an outflow glac ...

is one of the longest continuously studied glaciers in the world, with research extending back to the 1970s, most of the glaciers of the Canadian Rockies have only been scientifically evaluated since the late 1990s. Glaciologist

Glaciology (; ) is the scientific study of glaciers, or more generally ice and natural phenomena that involve ice.

Glaciology is an interdisciplinary Earth science that integrates geophysics, geology, physical geography, geomorphology, climato ...

s are now researching the glaciers in the park more thoroughly, and have been analyzing the impact that reduced glacier ice may have on water supplies to streams and rivers. Estimates are that 150 glaciers disappeared in the Canadian Rockies (areas both inside and outside Banff National Park) between the years 1920 and 1985. Another 150 glaciers disappeared between 1985 and 2005, indicating that the retreat and disappearance of glaciers is accelerating. In Banff National Park alone, in 1985 there were 365 glaciers but by 2005, 29 glaciers had disappeared. The total glaciated area dropped from in that time period.

The largest glaciated areas include the Waputik and Wapta Icefield

The Wapta Icefield is located on the Continental Divide in the Waputik Mountains of the Canadian Rockies, in the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. The icefield is shared by Banff and Yoho National Parks and numerous outlet glaciers exte ...

s, which both lie on the Banff-Yoho National Park border. Wapta Icefield covers approximately in area. Outlets of Wapta Icefield on the Banff side of the continental divide include Peyto, Bow, and Vulture Glaciers. Bow Glacier retreated an estimated between the years 1850 and 1953, and since that period, there has been further retreat which has left a newly formed lake at the terminal moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris (regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice shee ...

. Peyto Glacier has lost 70 percent of its volume since record keeping began and has retreated approximately since 1880; the glacier is at risk of disappearing entirely within the next 30 to 40 years.

The

The Columbia Icefield

The Columbia Icefield is the largest ice field in North America's Rocky Mountains. Located within the Canadian Rocky Mountains astride the Continental Divide along the border of British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, the ice field lies partly in ...

, at the northern end of Banff, straddles the Banff and Jasper National Park border and extends into British Columbia. Snow Dome, in the Columbia Icefield is a hydrological apex of North America, with water flowing via outlet glaciers to the Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic Oceans. Saskatchewan Glacier, which is approximately in length and in area, is the major outlet of the Columbia Icefield that flows into Banff National Park. Between the years 1893 and 1953, Saskatchewan Glacier had retreated a distance of , with the rate of retreat between the years 1948 and 1953 averaging per year. Overall, the glaciers of the Canadian Rockies lost 25 percent of their mass during the 20th century.

Climate

Under the

Under the Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

, the park has a subarctic climate

The subarctic climate (also called subpolar climate, or boreal climate) is a climate with long, cold (often very cold) winters, and short, warm to cool summers. It is found on large landmasses, often away from the moderating effects of an ocean, ge ...

(''Dfc'') with cold, snowy winters, and mild summers. The climate is influenced by altitude with lower temperatures generally found at higher elevations. Located on the eastern side of the Continental Divide, Banff National Park receives of precipitation annually. This is considerably less than in Yoho National Park on the western side of the divide in British Columbia, where is received at Wapta Lake

Wapta Lake is a glacial lake in Yoho National Park in the Canadian Rockies of eastern British Columbia, Canada.

Wapta Lake is formed from Cataract Brook and Blue Creek in Yoho National Park, and is the source of the Kicking Horse River.

The Trans ...

and at Boulder Creek annually. Being influenced by altitude, snowfall is also greater at higher elevations. As such, of snow falls on average each year in the Banff townsite, while falls in Lake Louise, which is located at a higher altitude.

During winter months, temperatures in Banff are moderated, compared to other areas of central and northern Alberta, due to Chinook wind

Chinook winds, or simply Chinooks, are two types of prevailing warm, generally westerly winds in western North America: Coastal Chinooks and interior Chinooks. The coastal Chinooks are persistent seasonal, wet, southwesterly winds blowing in from ...

s and other influences from British Columbia. The mean low temperature during January is , and the mean high temperature is for the town of Banff. However, temperatures can drop below with wind chill values dropping below . Weather conditions during summer months are warm, with high temperatures during July averaging , and daily low temperatures averaging , leading to a large diurnal range owing to the relative dryness of the air.

Ecology

Ecoregions

Banff National Park spans three

Banff National Park spans three ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) or ecozone (ecological zone) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of l ...

s, including montane

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is a crucial f ...

, subalpine

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is a crucial f ...

, and alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range