Byzantine–Norman Wars on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Byzantine–Norman wars were a series of military conflicts between the

Following their successful conquest of Southern Italy, the Norman faction led by Robert Guiscard saw no reason to stop; Byzantium was decaying further still and looked ripe for conquest. Further pressing Norman motivation to invade was consistent support by the Byzantines for uprisings against Robert Guiscard. The Western edge of the Byzantine empire in particular was known for being a safe haven for rebel groups. When Alexios I Comnenus ascended to the throne of Byzantium, his early emergency reforms, such as requisitioning Church money—a previously unthinkable move—proved too little to stop the Normans.

Led by the formidable

Following their successful conquest of Southern Italy, the Norman faction led by Robert Guiscard saw no reason to stop; Byzantium was decaying further still and looked ripe for conquest. Further pressing Norman motivation to invade was consistent support by the Byzantines for uprisings against Robert Guiscard. The Western edge of the Byzantine empire in particular was known for being a safe haven for rebel groups. When Alexios I Comnenus ascended to the throne of Byzantium, his early emergency reforms, such as requisitioning Church money—a previously unthinkable move—proved too little to stop the Normans.

Led by the formidable

In 1147 the Byzantine empire under Manuel I Comnenus was faced with war by Roger II of Sicily, whose fleet had captured the Byzantine island of

In 1147 the Byzantine empire under Manuel I Comnenus was faced with war by Roger II of Sicily, whose fleet had captured the Byzantine island of

Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

and the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

fought from 1040 to 1186 involving the Norman-led Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

in the west, and the Principality of Antioch in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

. The last of the Norman invasions, though having incurred disaster upon the Romans by sacking Thessalonica in 1185, was eventually driven out and vanquished by 1186.

Norman conquest of Southern Italy

The Normans' initial military involvement in Southern Italy was on the side of theLombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

against the Byzantines. Eventually, some Normans, including the powerful de Hauteville brothers, served in the army of George Maniakes during the attempted Byzantine reconquest of Sicily, only to turn against their employers when the emirs proved difficult to conquer. By 1030, Rainulf became count of Aversa, marking the start of permanent Norman settlement in Italy. In 1042, William de Hauteville was made a count, taking Lombard prince Guaimar IV of Salerno

Guaimar IV (c. 1013 – 2, 3 or 4 June 1052) was Prince of Salerno (1027–1052), Duke of Amalfi (1039–1052), Duke of Gaeta (1040–1041), and Prince of Capua (1038–1047) in Southern Italy over the period from 1027 to 1052. ...

as his liege.Holmes 1988, p. 210 To further strengthen ties and legitimacy, Robert Guiscard

Robert Guiscard ( , ; – 17 July 1085), also referred to as Robert de Hauteville, was a Normans, Norman adventurer remembered for his Norman conquest of southern Italy, conquest of southern Italy and Sicily in the 11th century.

Robert was born ...

also married Lombard Princess Sikelgaita

Sikelgaita (also ''Sichelgaita'', ''Sigelgaita'', or ''Gaita'') (c. 1040 – 16 April 1090) was a Lombards, Lombard princess, the daughter of Prince Guaimar IV of Salerno and second wife of Duke Robert Guiscard of Apulia. Her heritage made her ...

in 1058. Following the death of Guaimar, the Normans were increasingly independent actors on the Southern Italian scene, which brought them into direct conflict with Byzantium.

During the time that the Normans had conquered Southern Italy, the Byzantine Empire was in a state of internal decay; the administration of the Empire had been wrecked, the efficient government institutions that provided Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus (; 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar Slayer (, ), was the senior Byzantine emperor from 976 to 1025. He and his brother Constantine VIII were crowned before their father Romanos II died in 963, but t ...

with a quarter of a million troops and adequate resources by taxation had collapsed within a period of three decades. Attempts by Isaac I Komnenos

Isaac I Komnenos or Comnenus (; – 1 June 1060) was Byzantine emperor from 1057 to 1059, the first reigning member of the Komnenian dynasty.

The son of the general Manuel Erotikos Komnenos, he was orphaned at an early age, and w ...

and Romanos IV Diogenes

Romanos IV Diogenes (; – ) was Byzantine emperor from 1068 to 1071. Determined to halt the decline of the Byzantine military and to stop Turkish incursions into the empire, he is nevertheless best known for his defeat and capture in 1071 at ...

to reverse the situation proved unfruitful. The premature death of the former and the overthrow of the latter led to further collapse as the Normans consolidated their conquest of Sicily and Italy.

Reggio Calabria

Reggio di Calabria (; ), commonly and officially referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the List of cities in Italy, largest city in Calabria as well as the seat of the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria. As ...

, the capital of the tagma of Calabria, was captured by Robert Guiscard in 1060. At the time, the Byzantines held a few coastal towns in Apulia, including Bari, the capital of the catepanate of Italy. In 1067–68, they gave financial support to a rebellion against Guiscard. In 1068, the Normans besieged Otranto

Otranto (, , ; ; ; ; ) is a coastal town, port and ''comune'' in the province of Lecce (Apulia, Italy), in a fertile region once famous for its breed of horses. It is one of I Borghi più belli d'Italia ("The most beautiful villages of Italy").

...

; in the same year, they began the siege of Bari itself. After defeating the Byzantines in a series of battles in Apulia, and after two major attempts to relieve the city had failed, the city Bari surrendered in April 1071, ending the Byzantine presence in Southern Italy.

In 1079–80, the Byzantines again gave their support to a rebellion against Guiscard. This support came largely in the form of financing smaller Norman mercenary groups to assist in the rebellion

Over a thirty-year period (1061–1091), Norman factions also completed the initial Byzantine attempt to retake Sicily. However, it would not be until 1130 that both Sicily and Southern Italy were united into one kingdom, formalized by Roger II of Sicily

Roger II or Roger the Great (, , Greek language, Greek: Ρογέριος; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Kingdom of Sicily, Sicily and Kingdom of Africa, Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon, C ...

.

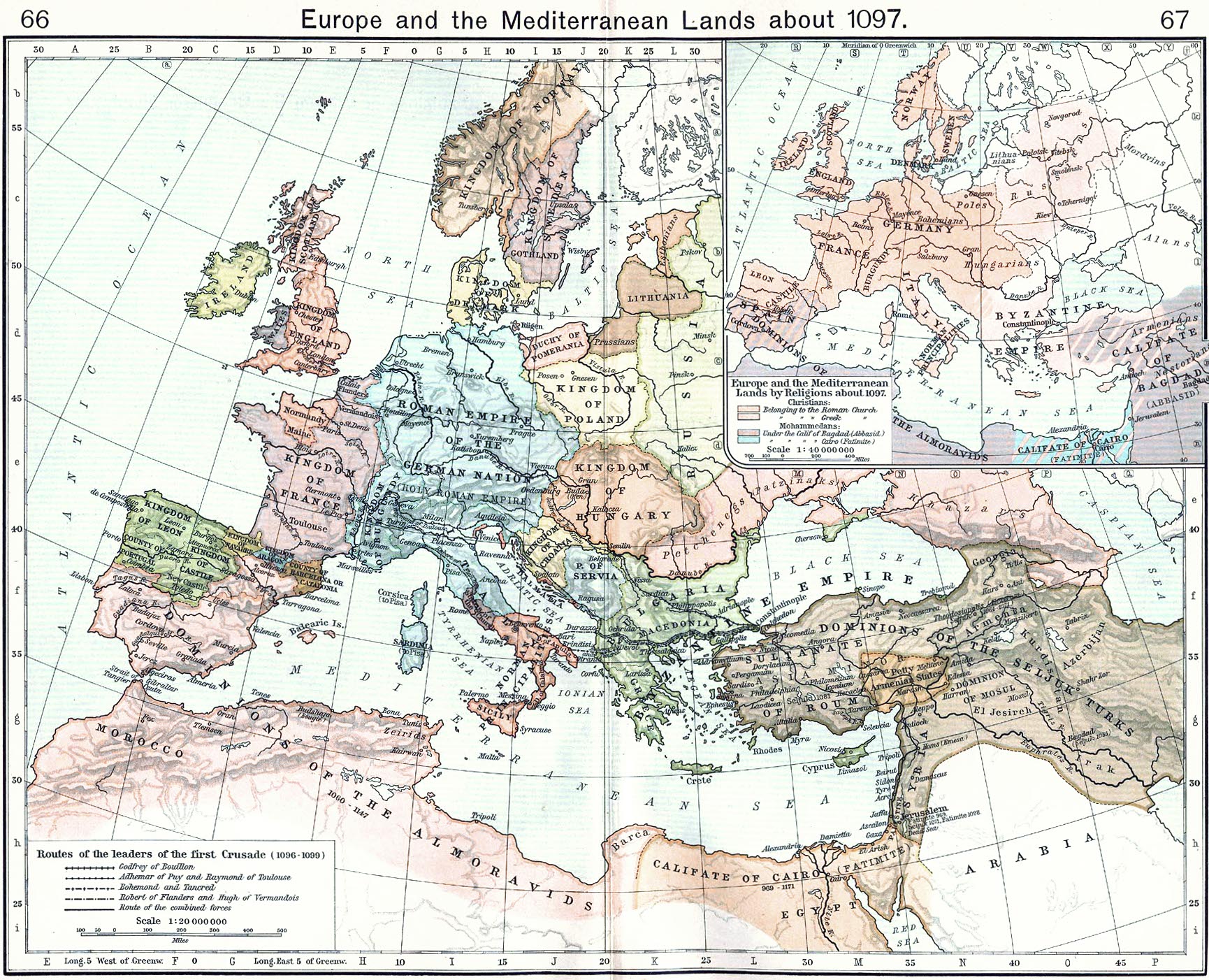

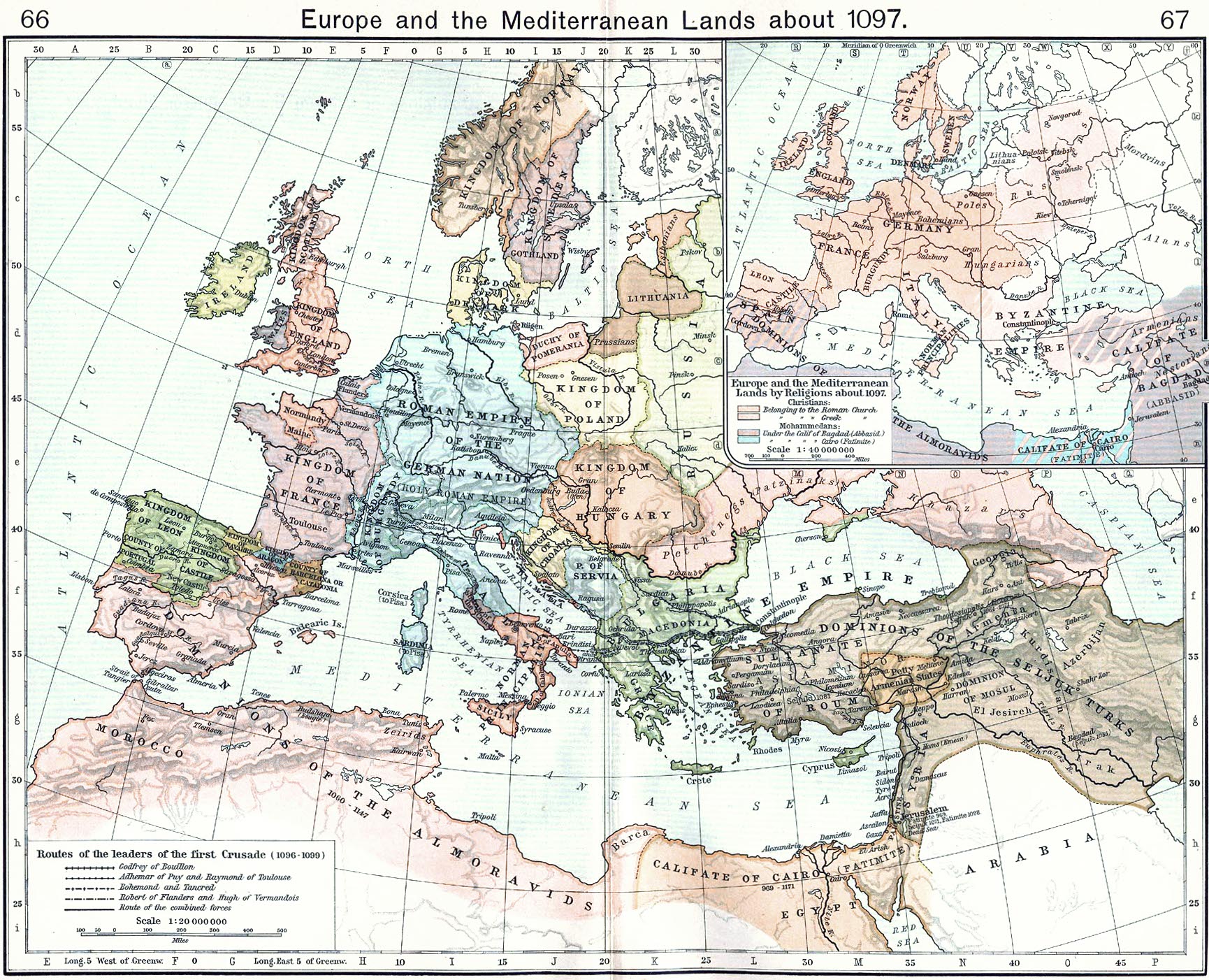

First Norman invasion of the Balkans (1081–1085)

Following their successful conquest of Southern Italy, the Norman faction led by Robert Guiscard saw no reason to stop; Byzantium was decaying further still and looked ripe for conquest. Further pressing Norman motivation to invade was consistent support by the Byzantines for uprisings against Robert Guiscard. The Western edge of the Byzantine empire in particular was known for being a safe haven for rebel groups. When Alexios I Comnenus ascended to the throne of Byzantium, his early emergency reforms, such as requisitioning Church money—a previously unthinkable move—proved too little to stop the Normans.

Led by the formidable

Following their successful conquest of Southern Italy, the Norman faction led by Robert Guiscard saw no reason to stop; Byzantium was decaying further still and looked ripe for conquest. Further pressing Norman motivation to invade was consistent support by the Byzantines for uprisings against Robert Guiscard. The Western edge of the Byzantine empire in particular was known for being a safe haven for rebel groups. When Alexios I Comnenus ascended to the throne of Byzantium, his early emergency reforms, such as requisitioning Church money—a previously unthinkable move—proved too little to stop the Normans.

Led by the formidable Robert Guiscard

Robert Guiscard ( , ; – 17 July 1085), also referred to as Robert de Hauteville, was a Normans, Norman adventurer remembered for his Norman conquest of southern Italy, conquest of southern Italy and Sicily in the 11th century.

Robert was born ...

and his son Bohemund of Taranto (later, Bohemund I of Antioch), and aided by the naval forces of their ally, the Croatian king Demetrius Zvonimir, Norman forces landed at Dyrrhacium, and put it under siege. Alexios marched to relieve the city, and engaged the Normans on October 18, 1081. The Varangians were placed as a vanguard, but were lured by retreating Normans and destroyed. The main line of the Romans engaged the Normans, but their morale was shaky from witnessing the annihilation of the Varangians, and they were unskilled compared to the veteran Normans. Before long, they broke and were routed. Alexios himself barely managed to escape. Dyrrachium, in the long term, would prove to be as crushing a defeat as Manzikert for the Empire. (see Battle of Dyrrhachium). The Normans would soon take Dyrrhachium and Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, The Normans continued to take cities around Dyrrhachium, marching to and taking Castoria, and preparing to launch a attack at the second city of the empire, Thessaloncia.

Alexios, desperatly looking for a way to save his empire, took drastic diplomatic action. He hoped to make the Holy Roman Emperor assault the Papal States, the Normans' nominal suzerain since 1080, in order to force Guiscard to march to the pope's aid. He enhanced his offer by bribing the German king Henry IV with 360,000 gold pieces to attack the Normans as well as the papacy in Italy, which forced Guiscard to concentrate on his defenses at home in 1083–1084, and he sailed home with the majority of his force, leaving Bohemond in command of the remaining normans in the Balkans. He also secured the alliance of Henry, Count of Monte Sant'Angelo, who controlled the Gargano Peninsula and dated his charters by Alexios' reign.

Bohemond began his campaign with vigor. Instead of marching against Thessaloncia, like his father had planned, Bohemond marched south to Ioannina, the capital of Epirus. The city quickly surrendered, while Alexios had regrouped since Dyrrhachium, and, having mustered a new army, rode to retake the city. Sometime in summer 1082, Alexios and Bohemond met outside of Ioannina. Numbers are unknown, but it is estimated that Alexios slightly outnumbered the Normans. Alexios had hoped to lure Bohemond into a frontal charge, where he could then flank the Normans. However, Bohemond instead ordered his knights to charge from the flanks, surprising the Romans, who quickly routed, with most of the infantry slaughtered. Alexios fled once more to Thessalonica, where he levied a new army, paying for them mainly with Orthodox treasures from churches. Bohemond, meanwhile, continued to march south, where he besieged Arta. However, unlike Ioannina, Arta held out. Alexios once again marched to relieve the besieged cities, forcing Bohemond to lift the siege to meet Alexios' army. Before the battle, Alexios placed stakes to impale the Norman's horses, but Bohemond again outflanked the emperor with his knights, crushing Alexios' army once more. The Romans, fully demoralized from several defeats, withdrew almost instantly once they became flanked, and the front line infantry was again surrounded and slaughtered. However, unlike Dyrrhachium and Ioannina, the Romans did not fully rout, and Alexios managed to restore order among his men, and retreat. Bohemond, pressing his advantage, did not renew the siege, but instead marched north, subduing Skopje before marching back to Castoria for the winter. However, the young Norman had grown confident in his army after his victories, and, instead of wintering in warm beds, decided to besiege Larissa, the regional capital.

It was already early November by the time Bohemond reached the city and put it under siege. The cities defense was led by Leo Cephalas, a veteran solider, and completely loyal to Alexios. Cephalas held out for six months through a grueling winter, but by spring, supplies were running out, and the city began to starve. However, during the winter, the stubborn emperor had been rallying yet another army, including 7000 Turkish mercenaries from the Sultanate of Rum, and in spring, he marched towards Larissa. He also sent agents to sow dissent within the Norman camp, accusing high ranking officers of treason, which undermined Bohemonds authority. Alexios reached the city in late spring, and spent several weeks drilling his men, and planning his attack. Alexios knew that his unskilled army had no chance in open battle against Bohemonds veteran, capable force, as shown at Ioannina and Arta. Instead, he used locals to teach his commanders about every detail of the land, and planned a ambush.

In July 1083, Alexios made his move. He sent the majority of his army in full view of the Normans, daring them to attack. Bohemond formed up for battle, and charged. However, the imperial army retreated, leading the Normans into the trap. Soon, the Normans, who were still chasing the imperial army, were attacked from the flank by Alexios's skirmishers and Turks. Here, Bohemond became separated from the majority of his army, as Count Brienne, one of Bohemond's commanders, peeled off his knights to attack his harassers. However, this would prove to be a disaster. The Count's heavily armored knights could not keep up with Alexios's Turks, and unable to engage their enemy, they were decimated by Turkish arrows. Brienne lost most of his force, and routed. Meanwhile, Bohemond ordered his troops to retreat back to the siege camp, wary of being outflanked. Back at the camp, he was met with the shattered remains of Brienne's forces. The next morning, the Romans, now vastly outnumbering their foes, attacked Bohemonds siege camp. Bohemond, learning from Brienne's mistakes, ordered his forces to not pursue the enemies. Alexios, instead of attacking directly, used his Turks once again to harass the Normans. Bohemond ordered his men to dismount and form a shield wall to protect themselves from the missle fire. After several hours of this harassment, arrows felling many, the Normans finally broke, and retreated back west, to Trikala. Alexios did not pursue.

Bohemond managed to restore control of his forces at Trikala. However, Alexios went all in to subdue the norman threat. Having already sown dissent within the Norman forces prior to Larissa, Alexios bribed many soldiers handsomely to desert Bohemond. Bohemond found he could not compete with the emperor in terms of bribes, as Alexios had the wealth of the entire Eastern Roman Empire (ERE), while Bohemond was alone in enemy territory. Bohemond, fearing complete mutiny, was forced to sail back to Italy, abandoning all the gains he had made in the Balkans. Despite the several great victories Bohemond had won, in the end, it had only taken one defeat to doom his cause. In the next years, Roman armies, with the help of the Venetians, retook all the land Bohemond had taken.

The Norman danger ended for the time being with the death of Robert Guiscard in 1085, combined with a Byzantine victory and crucial Venetian aid that allowed the Byzantines to retake the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. Alexios had to grant the Venetians, privileges to assure their support, something that eventually led to them controlling a substantial amount of the empire's financial sector.

Rebellion of Antioch (1104–1140)

During the time of theFirst Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

, the Byzantines were able to utilize, to some extent, Norman mercenaries to defeat the Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; , ''Saljuqian'',) alternatively spelled as Saljuqids or Seljuk Turks, was an Oghuz Turks, Oghuz Turkic, Sunni Muslim dynasty that gradually became Persianate society, Persianate and contributed to Turco-Persi ...

in numerous battles. These Norman mercenaries were instrumental in the capture of multiple cities. It is speculated that, in exchange for an oath of loyalty, Alexios promised land around the city of Antioch to Bohemond in order to create a buffer vassal state and simultaneously keep Bohemond away from Italy. However, when Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

fell the Normans refused to hand it over, although in time Byzantine domination was established. Out of fear that this signaled Byzantine intentions to reconquer Southern Italy and remove his suzerainty over the Normans, Pope Innocent II

Pope Innocent II (; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as Pope was controversial, and the first eight years o ...

declared the emperor excommunicated, and threatened any Latin Christian who served in his army with the same consequence. With the death of John Comnenus the Norman Principality of Antioch rebelled once again, invading Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

(which would also rebel), and sacking much of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

. The quick and energetic response of Manuel Komnenus allowed the Byzantines to extract an even more favorable ''modus vivendi

''Modus vivendi'' (plural ''modi vivendi'') is a Latin phrase that means "mode of living" or " way of life". In international relations, it often is used to mean an arrangement or agreement that allows conflicting parties to coexist in peace. In ...

'' with Antioch (in 1145 being forced to provide Byzantium with a contingent of troops and allow a Byzantine garrison in the city). However, the city was given guarantees of protection against Turkic attack and Nur ad-Din Zangi

Nūr al-Dīn Maḥmūd Zengī (; February 1118 – 15 May 1174), commonly known as Nur ad-Din (lit. 'Light of the Faith' in Arabic), was a Turkoman (ethnonym), Turkoman member of the Zengid dynasty, who ruled the Syria (region), Syrian province ...

abstained from attacking the northern parts of the Crusader states as a result.

Second Norman invasion of the Balkans (1147–1149)

Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

and plundered Thebes and Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

. However, despite being distracted by a Cuman

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Rus' chronicles, as " ...

attack in the Balkans, in 1148 Manuel enlisted the alliance of Conrad III of Germany, and the help of the Venetians, who quickly defeated Roger with their powerful fleet.Rowe 1959, p.118. In ca.1148, the political situation in the Balkans was divided by two sides, one being the alliance of the Byzantines and Venice, the other the Normans and Hungarians. The Normans were sure of the danger that the battlefield would move from the Balkans to their area in Italy. The Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

, Hungarians and Normans exchanged envoys, being in the interest of the Normans to stop Manuel's plans to recover Italy. In 1149, Manuel recovered Corfu and prepared to take the offensive against the Normans, while Roger II sent George of Antioch with a fleet of 40 ships to pillage Constantinople's suburbs. Manuel had already agreed with Conrad on a joint invasion and partition of southern Italy and Sicily. The renewal of the German alliance remained the principal orientation of Manuel's foreign policy for the rest of his reign, despite the gradual divergence of interests between the two empires after Conrad's death. However, while Manuel was in Valona planning the offensive across the Adriatic, the Serbs revolted, posing a danger to the Byzantine Adriatic bases.

Manuel I's intervention in Southern Italy (1155–1156)

The death of Roger in February 1154, who was succeeded by William I, combined with the widespread rebellions against the rule of the new King inSicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

, the presence of Apulian refugees at the Byzantine court, and Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (; ), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death in 1190. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on 4 March 1152 and crowned in Aachen on 9 March 115 ...

's (Conrad's successor) failure to deal with the Normans encouraged Manuel to take advantage of the multiple instabilities that existed in the Italian peninsula. He sent Michael Palaiologos and John Doukas, both of whom held the high imperial rank of '' sebastos'', with Byzantine troops, 10 Byzantine ships, and large quantities of gold to Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

(1155). The two generals were instructed to enlist the support of Frederick Barbarossa, since he was hostile to the Normans of Sicily and was south of the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

at the time, but he declined because his demoralised army longed to get back north of the Alps as soon as possible. Nevertheless, with the help of disaffected local barons including Count Robert of Loritello, Manuel's expedition achieved astonishingly rapid progress as the whole of Southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

rose up in rebellion against the Sicilian Crown, and the untried William I. There followed a string of spectacular successes as numerous strongholds yielded either to force or the lure of gold.

William and his army landed on the peninsula and destroyed the Greek fleet (4 ships) and army at Brindisi on May 28, 1156 and recovered Bari. Pope Adrian IV came to terms at Benevento

Benevento ( ; , ; ) is a city and (municipality) of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the Sabato (r ...

on June 18, 1156 where he and William signed the Treaty of Benevento, abandoning the rebels and confirming William as king. During the summer of 1157, he sent a fleet of 164 ships carrying 10,000 men to sack Euboea and Almira. In 1158 William made peace with the Romans.Cinnamo, pp. 170, 16–175, 19.

Third Norman invasion of the Balkans (1185–1186)

Although the last invasions and last large scale conflict between the two powers lasted less than two years, the third Norman invasions came closer still to takingConstantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. Then Byzantine Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos

Andronikos I Komnenos (; – 12 September 1185), Latinized as Andronicus I Comnenus, was Byzantine emperor from 1183 to 1185. A nephew of John II Komnenos (1118–1143), Andronikos rose to fame in the reign of his cousin Manuel I Komne ...

had allowed the Normans to go relatively unchecked towards Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area) and the capital city, capital of the geographic reg ...

. While David Komnenos had made some preparations in anticipation of the encroaching Normans, such as ordering reinforcement of the cities walls' and assigning four divisions to the cities' defense, these precautions proved insufficient. Only one of the four divisions actually engaged the Normans, resulting in the city being captured with relative ease by Norman forces. Upon gaining control of the city Norman forces sacked Thessalonica. The following panic resulted in a revolt placing Isaac II Angelos

Isaac II Angelos or Angelus (; September 1156 – 28 January 1204) was Byzantine Emperor from 1185 to 1195, and co-Emperor with his son Alexios IV Angelos from 1203 to 1204. In a 1185 revolt against the Emperor Andronikos Komnenos, Isaac ...

on the throne. In the aftermath of the fall of Andronikos, a reinforced Byzantine field army under Alexios Branas decisively defeated the Normans at the Battle of Demetritzes. Following this battle Thessalonica was speedily recovered and the Normans were pushed back to Italy. The exception was the County palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos

The County Palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos existed from 1185 to 1479 as part of the Kingdom of Sicily. The title and the right to rule the Ionian islands of Cephalonia and Zakynthos was originally given to Margaritus of Brindisi for his serv ...

, which remained in the hands of the Norman admiral Margaritus of Brindisi

Margaritus of Brindisi (also Margarito; Italian language, Italian: ''Margaritone'', Greek language, Greek: ''Megareites'' or ''Margaritoni'' �αργαριτώνη c. 1149 – 1197), called "the new Neptune", was the last great ''ammiratus ...

and his successors until it fell to the Turks in 1479.

Aftermath

With the Normans unable to take the Balkans, they turned their attention to European affairs. The Byzantines meanwhile had not possessed the will or the resources for any Italian invasion since the days of Manuel Comnenus. After the third invasion, the survival of the Empire became more important to the Byzantines than a mere province on the other side of theAdriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

. The death of William II, who was without an heir, threw the kingdom into instability and upheaval, and by 1194 the Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynast ...

had taken power, themselves being replaced in 1266 by the Angevins.Davis-Secord 2017, p.215. The successive Sicilian rulers would eventually continue the Norman policy of domination over post-Byzantine states in the Ionian Sea and Greece, attempting to assert suzerainty over Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, finally conquered in 1260, the County palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos

The County Palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos existed from 1185 to 1479 as part of the Kingdom of Sicily. The title and the right to rule the Ionian islands of Cephalonia and Zakynthos was originally given to Margaritus of Brindisi for his serv ...

, the Despotate of Epirus

The Despotate of Epirus () was one of the Greek Rump state, successor states of the Byzantine Empire established in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 by a branch of the Angelos dynasty. It claimed to be the legitimate successor of the ...

and other territories.

Citations

General and cited sources

Primary

* Anna Comnena, translated by E. R. A. Sewter (1969). ''The Alexiad''. London: Penguin Books. .Secondary

* * * Charanis, Peter. (1952). "Aims of the Medieval Crusades and How They Were Viewed by Byzantium." ''Church History'', Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 123–134. * Davis-Secord, Sarah. (2017). "Sicily at the Center of the Mediterranean". ''Where Three Worlds Met: Sicily in the Early Medieval Mediterranean''. Cornell University Press. . * * *Christopher Gravett

Christopher Gravett is an assistant curator of armour at the Tower Armouries specialising in the arms and armour of the medieval world.

Gravett has written a number of books and acts as an advisor for film and television projects.

Selected work ...

and David Nicolle

David C. Nicolle (born 4 April 1944) is a British historian specialising in the military history of the Middle Ages, with a particular interest in the Middle East. Life

David Nicolle worked for BBC Arabic before getting his MA at SOAS, Univers ...

(2006). ''The Normans: Warrior Knights and Their Castles''. Oxford: Osprey. .

* John Haldon (2000). ''The Byzantine Wars''. The Mill: Tempest. .

* Holmes, George. (1988). ''The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe''. Oxford University Press. .

* Richard Holmes (1988). ''The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations That Changed the Course of History''. Middlesex: Penguin. .

* Loud, G. A. (1999). "Coinage, Wealth, and Plunder in the Age of Robert Guiscard". ''The English Historical Review''. Vol. 114, No. 458, pp. 815–843.

*

*

* McQueen, William B. "Relations Between the Normans and Byzantium 1071–1112". ''Byzantion'', vol. 56, 1986, pp. 427–476. . Accessed 22 Apr. 2020.

*

*

* Rowe, John Gordon. (1959). "The Papacy and the Greeks (1122–1153)". ''Church History''. Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 115–130.

* Shepard, Jonathan. (1973). "The English and Byzantium: A Study of Their Role in the Byzantine Army in the Later Eleventh Century". ''Traditio'', Vol. 29. pp. 53–92.

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Byzantine-Norman wars

11th century in the Byzantine Empire

12th century in the Byzantine Empire

11th-century conflicts

12th-century conflicts

Wars involving the Holy Roman Empire