Buchenwald Slave Laborers Liberation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Buchenwald (; 'beech forest') was a German

The ''

The '' The camp, designed to hold 8,000 prisoners, was intended to replace several smaller concentration camps nearby, including Bad Sulza, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg. Compared to these camps, Buchenwald had a greater potential to profit the SS because the nearby clay deposits could be made into bricks by the forced labor of prisoners. The first prisoners arrived on 15 July 1937, and had to clear the area of trees and build the camp's structures. By September, the population had risen to 2,400 following transfers from Bad Sulza, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg.

On the camp's main gate, the motto ''

The camp, designed to hold 8,000 prisoners, was intended to replace several smaller concentration camps nearby, including Bad Sulza, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg. Compared to these camps, Buchenwald had a greater potential to profit the SS because the nearby clay deposits could be made into bricks by the forced labor of prisoners. The first prisoners arrived on 15 July 1937, and had to clear the area of trees and build the camp's structures. By September, the population had risen to 2,400 following transfers from Bad Sulza, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg.

On the camp's main gate, the motto ''

A primary cause of death was illness due to harsh camp conditions. Like all concentration camps, prisoners at Buchenwald were deliberately kept in a state of

A primary cause of death was illness due to harsh camp conditions. Like all concentration camps, prisoners at Buchenwald were deliberately kept in a state of

In April 1945 an Alsos Mission team was searching for a German nuclear physicist near Weimar, eastern Germany. Taking a side road through woods to avoid German forces, they struck a ghastly smell from a clearing, and saw a barbed wire enclosure with a few pathetic figures and piles of corpses. Before continuing their mission they broke secrecy protocol to radio a request for the Army to send medical help. A group of survivors had just taken control of the camp from the few remaining Nazi guards. The four-man team was under linguist Hugh Montgomery and included Corporal Rick Carrier. Montgomery recalled the survivors made a final request: ''Please give the guards to us, and we’ll take care of them ..... And I’m sure they did''. Montgomery later joined the CIA, and took part in Operation Gold in Berlin.

On 4 April 1945 the U.S. 89th Infantry Division overran Ohrdruf, a subcamp of Buchenwald.

Buchenwald was partially evacuated by the Germans from 6 to 11 April 1945. In the days before the arrival of the American army, thousands of the prisoners were forcibly evacuated

on foot.

Thanks in large part to the efforts of Polish engineer (and

In April 1945 an Alsos Mission team was searching for a German nuclear physicist near Weimar, eastern Germany. Taking a side road through woods to avoid German forces, they struck a ghastly smell from a clearing, and saw a barbed wire enclosure with a few pathetic figures and piles of corpses. Before continuing their mission they broke secrecy protocol to radio a request for the Army to send medical help. A group of survivors had just taken control of the camp from the few remaining Nazi guards. The four-man team was under linguist Hugh Montgomery and included Corporal Rick Carrier. Montgomery recalled the survivors made a final request: ''Please give the guards to us, and we’ll take care of them ..... And I’m sure they did''. Montgomery later joined the CIA, and took part in Operation Gold in Berlin.

On 4 April 1945 the U.S. 89th Infantry Division overran Ohrdruf, a subcamp of Buchenwald.

Buchenwald was partially evacuated by the Germans from 6 to 11 April 1945. In the days before the arrival of the American army, thousands of the prisoners were forcibly evacuated

on foot.

Thanks in large part to the efforts of Polish engineer (and  According to Teofil Witek, a fellow Polish prisoner who witnessed the transmissions, Damazyn fainted after receiving the message.

As American forces closed in, Gestapo headquarters at Weimar telephoned the camp administration to announce that it was sending explosives to blow up any evidence of the camp, including its inmates. The Gestapo did not know that the administrators had already fled. A prisoner answered the phone and informed headquarters that explosives would not be needed, as the camp had already been blown up, which was not true.

A detachment of troops of the U.S. 9th Armored Infantry Battalion, from the 6th Armored Division, part of the U.S. Third Army, and under the command of

According to Teofil Witek, a fellow Polish prisoner who witnessed the transmissions, Damazyn fainted after receiving the message.

As American forces closed in, Gestapo headquarters at Weimar telephoned the camp administration to announce that it was sending explosives to blow up any evidence of the camp, including its inmates. The Gestapo did not know that the administrators had already fled. A prisoner answered the phone and informed headquarters that explosives would not be needed, as the camp had already been blown up, which was not true.

A detachment of troops of the U.S. 9th Armored Infantry Battalion, from the 6th Armored Division, part of the U.S. Third Army, and under the command of

Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1983 edition

* * * * * * * * * *Tillack-Graf, Anne-Kathleen (2012). ''Erinnerungspolitik der DDR. Dargestellt an der Berichterstattung der Tageszeitung "Neues Deutschland" über die Nationalen Mahn- und Gedenkstätten Buchenwald, Ravensbrück und Sachsenhausen.'' Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main. ISBN 978-3-631-63678-7. * * *

Survivors, academics recall dark episode in Germany's postwar history

Deutsche Welle, 16 February 2010.

Guide to the Concentration Camps Collection

Leo Baeck Institute, New York City 2013. Includes extensive reports on Buchenwald collected by the Allied forces shortly after liberating the camp in April 1945.

Holocaust Buchenwald Concentration Camp Uncovered (1945) , British Pathé

on YouTube {{DEFAULTSORT:Buchenwald Concentration Camp Buchenwald concentration camp, 1937 establishments in Germany Buildings and structures in Weimar Museums in Thuringia Monuments and memorials to the victims of Nazism World War II museums in Germany 1950 disestablishments in Germany

Nazi concentration camp

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps (), including subcamp (SS), subcamps on its own territory and in parts of German-occupied Europe.

The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately af ...

established on Ettersberg hill near Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within the Altreich (Old Reich) territories. Many actual or suspected communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

s were among the first internees.

Prisoners came from all over Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, and included Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

, and other Slavs

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and ...

, the mentally ill, and physically disabled, political prisoners, Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

People, characters, figures, names

* Roma or Romani people, an ethnic group living mostly in Europe and the Americas.

* Roma called Roy, ancient Egyptian High Priest of Amun

* Roma (footballer, born 1979), born ''Paul ...

, Freemasons

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, and prisoners of war. There were also ordinary criminals and those perceived as sexual deviants by the Nazi regime. All prisoners worked primarily as forced labor in local armaments factories. The insufficient food and poor conditions, as well as deliberate executions, led to 56,545 deaths at Buchenwald of the 280,000 prisoners who passed through the camp and its 139 subcamps.

The camp gained notoriety when it was liberated by the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

in April 1945; Allied commander Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

visited one of its subcamps.

From August 1945 to March 1950, the camp was used by the Soviet occupation authorities as an internment camp, NKVD special camp Nr. 2, where 28,455 prisoners were held and 7,127 of whom died. Today the remains of Buchenwald serve as a memorial and permanent exhibition and museum.

Establishment

The ''

The ''Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (; ; SS; also stylised with SS runes as ''ᛋᛋ'') was a major paramilitary organisation under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe during World War II.

It beg ...

'' (SS) established Buchenwald concentration camp at the beginning of July 1937. The camp was to be named Ettersberg, after the hill in Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

upon whose north slope the camp was established. The proposed name was deemed inappropriate because it carried associations with several important figures in German culture, especially Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

who had lived in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

. Instead the camp was to be named Buchenwald, in reference to the beech

Beech (genus ''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to subtropical (accessory forest element) and temperate (as dominant element of Mesophyte, mesophytic forests) Eurasia and North America. There are 14 accepted ...

forest in the area. However, Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

researcher James E. Young wrote that SS leaders chose the site of the camp precisely to erase the cultural legacy of the area. After the area of the camp was cleared of trees, only one large oak remained, supposedly one of Goethe's Oaks.

The camp, designed to hold 8,000 prisoners, was intended to replace several smaller concentration camps nearby, including Bad Sulza, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg. Compared to these camps, Buchenwald had a greater potential to profit the SS because the nearby clay deposits could be made into bricks by the forced labor of prisoners. The first prisoners arrived on 15 July 1937, and had to clear the area of trees and build the camp's structures. By September, the population had risen to 2,400 following transfers from Bad Sulza, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg.

On the camp's main gate, the motto ''

The camp, designed to hold 8,000 prisoners, was intended to replace several smaller concentration camps nearby, including Bad Sulza, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg. Compared to these camps, Buchenwald had a greater potential to profit the SS because the nearby clay deposits could be made into bricks by the forced labor of prisoners. The first prisoners arrived on 15 July 1937, and had to clear the area of trees and build the camp's structures. By September, the population had risen to 2,400 following transfers from Bad Sulza, Sachsenburg, and Lichtenburg.

On the camp's main gate, the motto ''Jedem das Seine

"'" () is the literal German translation of the Latin phrase '' suum cuique'', meaning "to each his own" or "to each what he deserves".

During World War II the phrase was contemptuously used by the Nazis as a motto displayed over the entrance o ...

'' (English: "To each what he deserves"), was inscribed. The SS interpreted this to mean the "master race

The master race ( ) is a pseudoscientific concept in Nazi ideology, in which the putative Aryan race is deemed the pinnacle of human racial hierarchy. Members were referred to as ''master humans'' ( ).

The Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg b ...

" had a right to humiliate and destroy others. It was designed by Buchenwald prisoner and Bauhaus

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the , was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined Decorative arts, crafts and the fine arts.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., ...

architect Franz Ehrlich, who used a Bauhaus typeface for it, even though Bauhaus was seen as degenerate art by the National Socialists

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

and was prohibited. This defiance however went unnoticed by the SS.

Command structure

Organization

Buchenwald's first commandant was SS-'' Obersturmbannführer'' Karl-Otto Koch, who ran the camp from 1 August 1937 to July 1941. His second wife,Ilse Koch

Ilse Koch (22 September 1906 – 1 September 1967) was a German war criminal who committed atrocities while her husband Karl-Otto Koch was commandant at Buchenwald concentration camp, Buchenwald. Though Ilse Koch had no official position in the N ...

, became notorious as ''Die Hexe von Buchenwald'' ("the witch of Buchenwald") for her cruelty and brutality. In February 1940 Koch had an indoor riding hall built by the prisoners who died by the dozen due to the harsh conditions of the construction site. The hall was built inside the camp, near the canteen, so that Ilse Koch could often be seen riding in the morning to the beat of the prisoner orchestra. Koch himself was eventually imprisoned at Buchenwald by the Nazi authorities for incitement to murder. The charges were lodged by Prince Waldeck and Morgen

A Morgen (Mg) is a historical, but still occasionally used, German unit of area used in agriculture. Officially, it is no longer in use, having been supplanted by the hectare. While today it is approximately equivalent to the Prussian ''morgen' ...

, to which were later added charges of corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense that is undertaken by a person or an organization that is entrusted in a position of authority to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's gain. Corruption may involve activities ...

, embezzlement

Embezzlement (from Anglo-Norman, from Old French ''besillier'' ("to torment, etc."), of unknown origin) is a type of financial crime, usually involving theft of money from a business or employer. It often involves a trusted individual taking ...

, black market

A black market is a Secrecy, clandestine Market (economics), market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality, or is not compliant with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the set of goods and services who ...

dealings, and exploitation of the camp workers for personal gain. Other camp officials were charged, including Ilse Koch. The trial resulted in Karl Koch being sentenced to death for disgracing both himself and the SS; he was executed by firing squad on 5 April 1945, one week before American troops arrived. Ilse Koch

Ilse Koch (22 September 1906 – 1 September 1967) was a German war criminal who committed atrocities while her husband Karl-Otto Koch was commandant at Buchenwald concentration camp, Buchenwald. Though Ilse Koch had no official position in the N ...

was acquitted by the SS court and released. However, she was rearrested by American occupation authorities in June 1945, and chosen as one of 31 Buchenwald defendants to stand trial before a Military Commission Court at Dachau. The life sentence imposed by the Dachau court was reduced to four years upon review. Upon her release from U.S. custody in October 1949, she was arrested by West German authorities, tried at Augsburg, and again sentenced to life imprisonment; she committed suicide in Aichach (Bavaria) prison in September 1967. The second commandant of the camp, between 1942 and 1945, was Hermann Pister (1942–1945). He was tried in 1947 (Dachau Trials

The Dachau trials, also known as the Dachau Military Tribunal, handled the prosecution of almost every war criminal captured in the U.S. military zones in Allied-occupied Germany and in Allied-occupied Austria, and the prosecutions of military ...

) and sentenced to death, but on 28 September 1948 he died in Landsberg Prison

Landsberg Prison is a prison in the town of Landsberg am Lech in the southwest of the German state of Bavaria, about west-southwest of Munich and south of Augsburg. It is best known as the prison where Adolf Hitler was held in 1924, after the ...

of a heart attack.

Female prisoners and overseers

The number of women held in Buchenwald was somewhere between 500 and 1,000. The first female inmates were twenty political prisoners who were accompanied by a female SS guard (''Aufseherin''); these women were brought to Buchenwald from Ravensbrück in 1941 and forced into sexual slavery at the camp'sbrothel

A brothel, strumpet house, bordello, bawdy house, ranch, house of ill repute, house of ill fame, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in Human sexual activity, sexual activity with prostitutes. For legal or cultural reasons, establis ...

. The SS later fired the SS woman on duty in the brothel for corruption; her position was taken over by "brothel mothers" as ordered by SS chief Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and military leader who was the 4th of the (Protection Squadron; SS), a leading member of the Nazi Party, and one of the most powerful p ...

.

The majority of women prisoners, however, arrived in 1944 and 1945 from other camps, mainly Auschwitz

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschw ...

, Ravensbrück, and Bergen Belsen

Bergen-Belsen (), or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in what is today Lower Saxony in northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen near Celle. Originally established as a prisoner of war camp, in 1943, parts of it became a concentr ...

. Only one barracks was set aside for them; this was overseen by the female block leader (''Blockführerin'') Franziska Hoengesberg, who came from Essen when it was evacuated. All the women prisoners were later shipped out to one of Buchenwald's many female satellite camps in Sömmerda

Sömmerda () is a town near Erfurt in Thuringia, Germany, on the Unstrut river. It is the capital of the Sömmerda (district), district of Sömmerda.

History

Archeological digs in the area that is now Sömmerda, formerly Leubingen, have uncove ...

, Buttelstedt

Buttelstedt is a town and a former municipality in the Weimarer Land district, in Thuringia, Germany. It is situated 11 km north of Weimar. Since 1 January 2019, it is part of the municipality Am Ettersberg.

History

Within the German Empir ...

, Mühlhausen

Mühlhausen () is a town in the north-west of Thuringia, Germany, north of Niederdorla, the country's Central Germany (geography)#Geographical centre, geographical centre, north-west of Erfurt, east of Kassel and south-east of Göttingen ...

, Gotha

Gotha () is the fifth-largest city in Thuringia, Germany, west of Erfurt and east of Eisenach with a population of 44,000. The city is the capital of the district of Gotha and was also a residence of the Ernestine Wettins from 1640 until the ...

, Gelsenkirchen

Gelsenkirchen (, , ; ) is the List of cities in Germany by population, 25th-most populous city of Germany and the 11th-most populous in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia with 262,528 (2016) inhabitants. On the Emscher, Emscher River (a tribu ...

, Essen

Essen () is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and Dortmund, as well as ...

, Lippstadt

Lippstadt () is a town in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is the largest town within the district of Soest. Lippstadt is situated about 60 kilometres east of Dortmund, 40 kilometres south of Bielefeld and 30 kilometres west of Paderborn.

Geo ...

, Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

, Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; ) is the Capital city, capital of the Germany, German States of Germany, state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is on the Elbe river.

Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archbishopric of Mag ...

, and Penig, to name a few. No female guards were permanently stationed at Buchenwald.

Contrary to popular opinion, the notorious "Bitch of Buchenwald" Ilse Koch

Ilse Koch (22 September 1906 – 1 September 1967) was a German war criminal who committed atrocities while her husband Karl-Otto Koch was commandant at Buchenwald concentration camp, Buchenwald. Though Ilse Koch had no official position in the N ...

never served in any official capacity at the camp, nor ever acted as guard. In total, however, more than 530 women served as guards in the vast Buchenwald system of subcamps and external commands across Germany. Only 22 women served/trained in Buchenwald, compared to over 15,500 men.

Subcamps

About 136 subcamps and satellite commandos belonged to Buchenwald concentration camp. In 1942, the SS began to use its forced labor supply for armaments production. Because it was more economical to rent out prisoners to private firms, subcamps were set up near factories which had a demand for prisoner labor. Private firms paid the SS between 4 and 6Reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛ︁ℳ︁; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, and in the American, British and French occupied zones of Germany, until 20 June 1948. The Reichsmark was then replace ...

s per day per prisoner, resulting in an estimated 95,758,843 Reichsmarks in revenue for the SS between June 1943 and February 1945. So the subcamps of Buchenwald were mainly used for armament production and other fabrications and are considered labour camps. Conditions were worse than at the main camp, with prisoners provided insufficient food and inadequate shelter.

Allied POWs

Although it was highly unusual for German authorities to send Western Allied POWs to concentration camps, Buchenwald held a group of 168 aviators for two months. These men were from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Jamaica. They all arrived at Buchenwald on 20 August 1944. All these airmen were in aircraft that had crashed inoccupied France

The Military Administration in France (; ) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called ' was established in June 19 ...

. Two explanations are given for them being sent to a concentration camp: first, that they had managed to make contact with the French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

, some were disguised as civilians, and they were carrying false papers when caught; they were therefore categorized by the Germans as spies, which meant their rights under the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, The original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are international humanitarian laws consisting of four treaties and three additional protocols that establish international legal standards for humanitarian t ...

were not respected. The second explanation is that they had been categorised as '' Terrorflieger'' ("terror aviators"). The aviators were initially held in Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

prisons and headquarters in France. In April or August 1944, they and other Gestapo prisoners were packed into covered goods wagon

A covered goods wagon or covered goods van (United Kingdom) is a railway goods wagon which is designed for the transportation of moisture-susceptible goods and therefore fully enclosed by sides and a fixed roof. They are often referred to simply ...

s and sent to Buchenwald. The journey took five days, during which they received very little food or water.

Victims

Causes of death

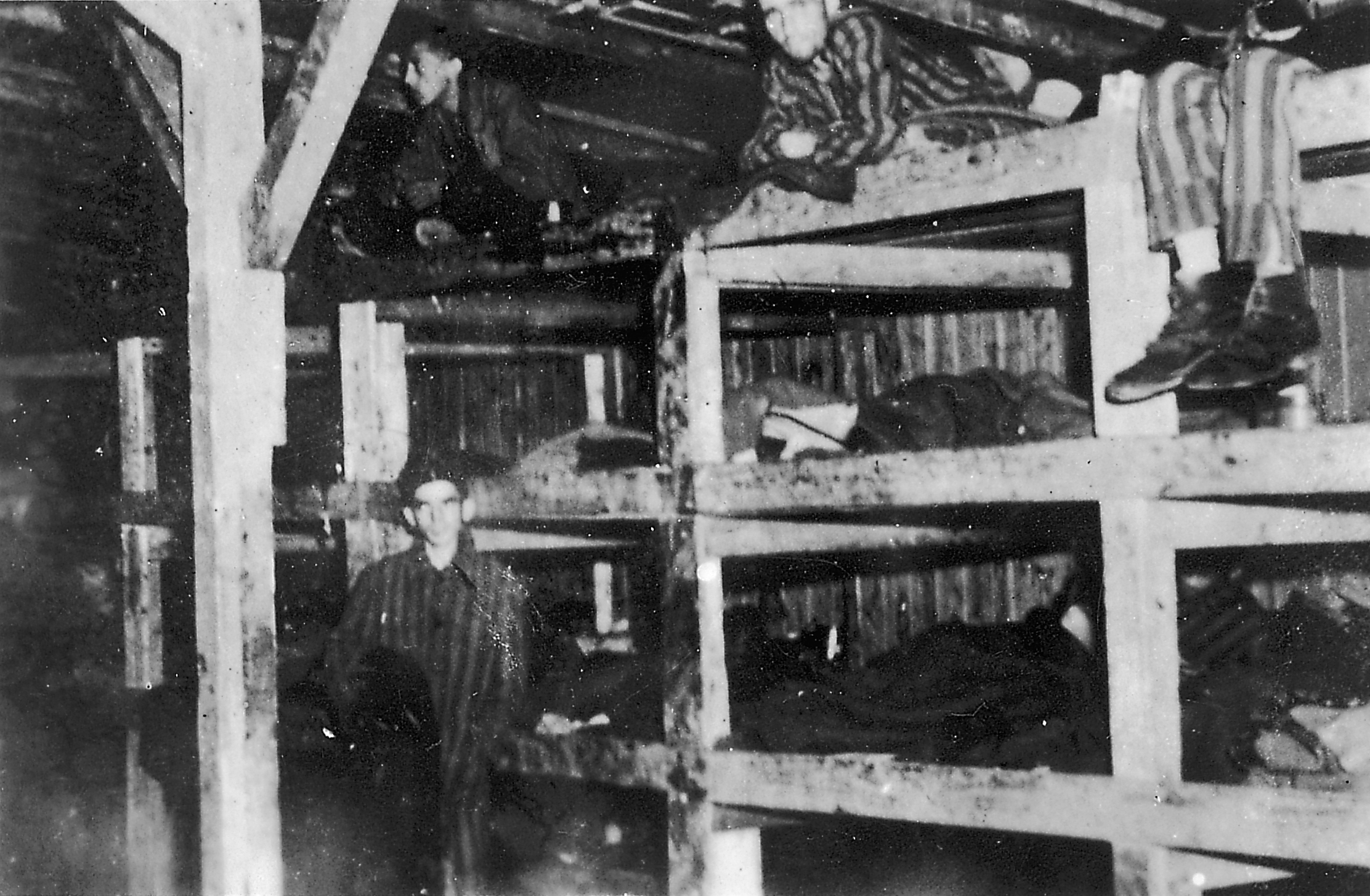

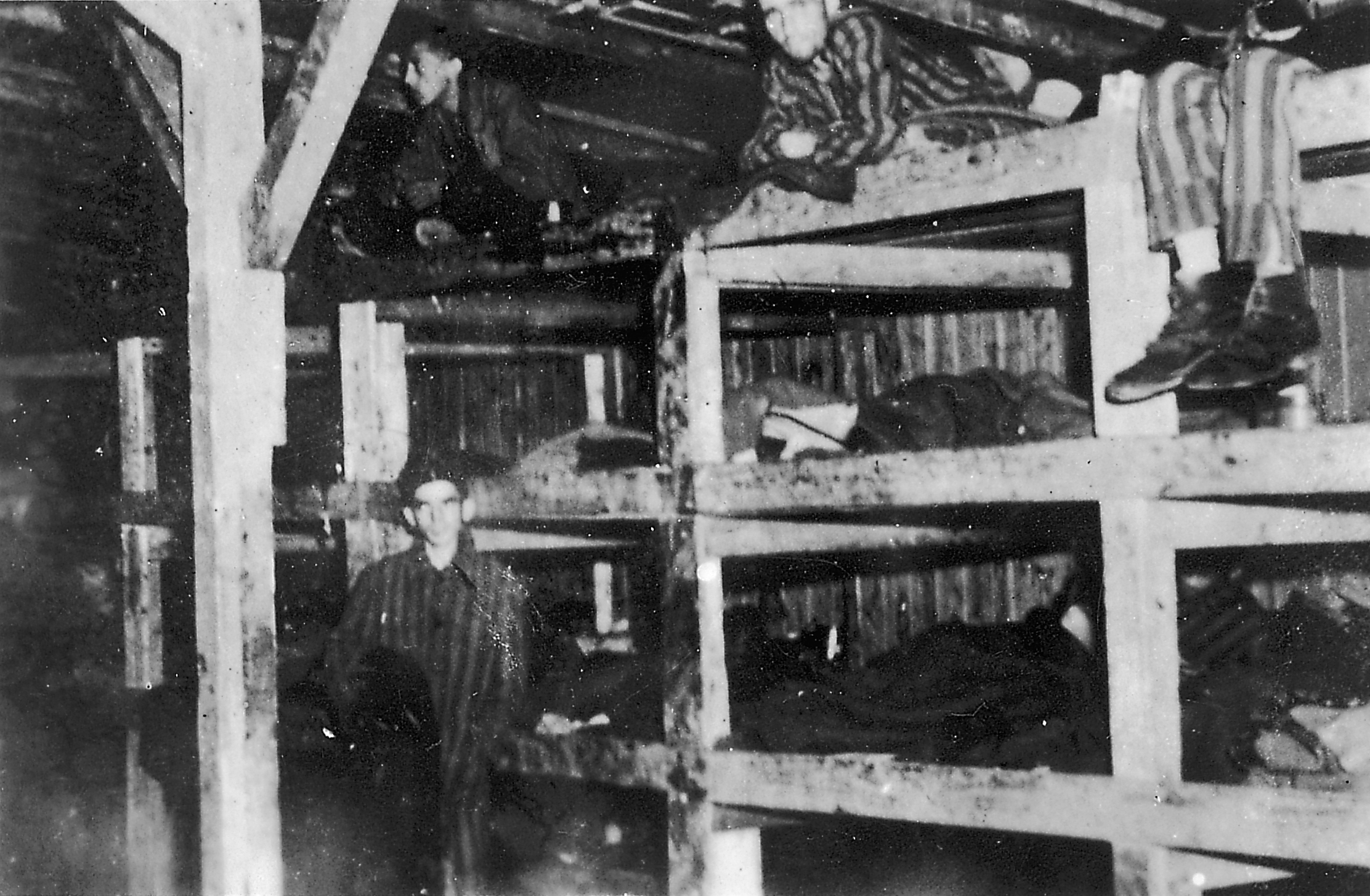

A primary cause of death was illness due to harsh camp conditions. Like all concentration camps, prisoners at Buchenwald were deliberately kept in a state of

A primary cause of death was illness due to harsh camp conditions. Like all concentration camps, prisoners at Buchenwald were deliberately kept in a state of starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

, many while performing grueling forced labor, making consequent illnesses prevalent. Malnourished and suffering from disease, many were literally "worked to death" under the ''Vernichtung durch Arbeit'' policy ( extermination through labor), as inmates only had the choice between slave labor or inevitable execution. Many inmates were killed by human experimentation

Human subject research is systematic, scientific investigation that can be either interventional (a "trial") or observational (no "test article") and involves human beings as research subjects, commonly known as test subjects. Human subject r ...

or fell victim to arbitrary acts perpetrated by the SS guards. Other prisoners were simply murdered, primarily by shooting and hanging. As part of Action 14f13

Action 14f13, also called '' Sonderbehandlung'' (special treatment) 14f13 and Aktion 14f13, was a campaign by Nazi Germany to murder Nazi concentration camp prisoners. As part of the campaign, also called ''invalid'' or ''prisoner euthanasia'', t ...

, prisoners deemed too weak or sick to work were sent to Sonnenstein Killing Facility, where they were murdered with carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

gas.

Walter Gerhard Martin Sommer was an SS-''Hauptscharführer

__NOTOC__

''Hauptscharführer'' ( ) was a Nazi paramilitary rank which was used by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) between the years of 1934 and 1945. The rank was the highest enlisted rank of the SS, with the exception of the special Waffen-SS ran ...

'' who served as a guard at the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald. Known as the "Hangman of Buchenwald", he was considered a depraved sadist who reportedly ordered Otto Neururer and Mathias Spanlang, two Austrian priests, to be crucified upside-down. Sommer was especially infamous for hanging prisoners from trees by their wrists, which had been tied behind their backs (a torture technique known as strappado

The strappado, also known as corda, is a form of torture in which the victim's hands are tied behind their back and the victim is suspended by a rope attached to the wrists, typically resulting in dislocated shoulders. Weights may be added to ...

) in the "singing forest", so named because of the screams which emanated from this wooded area.

Summary execution

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

s of Soviet POWs were also carried out at Buchenwald. At least 1,000 men were selected in 1941–42 by a task force of three Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

officers and sent to the camp for immediate liquidation by a gunshot to the back of the neck, the infamous ''Genickschuss''.

The camp was also a site of large-scale trials for vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

s against epidemic typhus

Epidemic typhus, also known as louse-borne typhus, is a form of typhus so named because the disease often causes epidemics following wars and natural disasters where civil life is disrupted. Epidemic typhus is spread to people through contact wit ...

in 1942 and 1943. In all 729 inmates were used as test subjects, of whom 154 died. Other "experimentation" occurred at Buchenwald on a smaller scale. One such experiment aimed at determining the precise fatal dose of a poison of the alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

group; according to the testimony of one doctor, four Soviet POWs were administered the poison, and when it proved not to be fatal they were "strangled in the crematorium" and subsequently "dissected". Among various other experiments was one which, in order to test the effectiveness of a balm for wounds from incendiary bomb

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires. They may destroy structures or sensitive equipment using fire, and sometimes operate as anti-personnel weaponry. Incendiarie ...

s, involved inflicting "very severe" white phosphorus

White phosphorus, yellow phosphorus, or simply tetraphosphorus (P4) is an allotrope of phosphorus. It is a translucent waxy solid that quickly yellows in light (due to its photochemical conversion into red phosphorus), and impure white phospho ...

burns on inmates. When challenged at trial over the nature of this testing, and particularly over the fact that the testing was designed in some cases to cause death and only to measure the time which elapsed until death was caused, one Nazi doctor's defence was that, although a doctor, he was a "legally appointed executioner".

Number of deaths

The SS left behind accounts of the number of prisoners and people coming to and leaving the camp, categorizing those leaving them by release, transfer, or death. These accounts are one of the sources of estimates for the number of deaths in Buchenwald. According to SS documents, 33,462 died. These documents were not, however, necessarily accurate: Among those executed before 1944, many were listed as "transferred to the Gestapo". Furthermore, from 1941, Soviet POWs were executed in mass killings. Arriving prisoners selected for execution were not entered into the camp register and therefore were not among the 33,462 dead listed. One former Buchenwald prisoner, Armin Walter, calculated the number of executions by the number of shootings in the spine at the base of the head. His job at Buchenwald was to set up and care for a radio installation at the facility where people were executed; he counted the numbers, which arrived by telex, and hid the information. He says that 8,483 Soviet prisoners of war were shot in this manner. According to the same source, the total number of deaths at Buchenwald is estimated at 56,545. This number is the sum of: * Deaths according to material left behind by the SS: 33,462 * Executions by shooting: 8,483 * Executions by hanging (estimate): 1,100 * Deaths during evacuation transports (estimate): 13,500 This total (56,545) corresponds to a death rate of 24 percent, assuming that the number of persons passing through the camp according to documents left by the SS, 240,000 prisoners, is accurate.Liberation

In April 1945 an Alsos Mission team was searching for a German nuclear physicist near Weimar, eastern Germany. Taking a side road through woods to avoid German forces, they struck a ghastly smell from a clearing, and saw a barbed wire enclosure with a few pathetic figures and piles of corpses. Before continuing their mission they broke secrecy protocol to radio a request for the Army to send medical help. A group of survivors had just taken control of the camp from the few remaining Nazi guards. The four-man team was under linguist Hugh Montgomery and included Corporal Rick Carrier. Montgomery recalled the survivors made a final request: ''Please give the guards to us, and we’ll take care of them ..... And I’m sure they did''. Montgomery later joined the CIA, and took part in Operation Gold in Berlin.

On 4 April 1945 the U.S. 89th Infantry Division overran Ohrdruf, a subcamp of Buchenwald.

Buchenwald was partially evacuated by the Germans from 6 to 11 April 1945. In the days before the arrival of the American army, thousands of the prisoners were forcibly evacuated

on foot.

Thanks in large part to the efforts of Polish engineer (and

In April 1945 an Alsos Mission team was searching for a German nuclear physicist near Weimar, eastern Germany. Taking a side road through woods to avoid German forces, they struck a ghastly smell from a clearing, and saw a barbed wire enclosure with a few pathetic figures and piles of corpses. Before continuing their mission they broke secrecy protocol to radio a request for the Army to send medical help. A group of survivors had just taken control of the camp from the few remaining Nazi guards. The four-man team was under linguist Hugh Montgomery and included Corporal Rick Carrier. Montgomery recalled the survivors made a final request: ''Please give the guards to us, and we’ll take care of them ..... And I’m sure they did''. Montgomery later joined the CIA, and took part in Operation Gold in Berlin.

On 4 April 1945 the U.S. 89th Infantry Division overran Ohrdruf, a subcamp of Buchenwald.

Buchenwald was partially evacuated by the Germans from 6 to 11 April 1945. In the days before the arrival of the American army, thousands of the prisoners were forcibly evacuated

on foot.

Thanks in large part to the efforts of Polish engineer (and short-wave

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using radio frequencies in the shortwave bands (SW). There is no official definition of the band range, but it always includes all of the high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30 MHz (appr ...

radio-amateur, his pre-war callsign was SP2BD) Gwidon Damazyn, an inmate since March 1941, a secret short-wave transmitter and small generator were built and hidden in the prisoners' movie room. On 8 April at noon, Damazyn and Russian prisoner Konstantin Ivanovich Leonov sent the Morse code

Morse code is a telecommunications method which Character encoding, encodes Written language, text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code i ...

message prepared by leaders of the prisoners' underground resistance (supposedly Walter Bartel and Harry Kuhn):

The text was repeated several times in English, German, and Russian. Damazyn sent the English and German transmissions, while Leonov sent the Russian version. Three minutes after the last transmission sent by Damazyn, the headquarters of the U.S. Third Army responded:

According to Teofil Witek, a fellow Polish prisoner who witnessed the transmissions, Damazyn fainted after receiving the message.

As American forces closed in, Gestapo headquarters at Weimar telephoned the camp administration to announce that it was sending explosives to blow up any evidence of the camp, including its inmates. The Gestapo did not know that the administrators had already fled. A prisoner answered the phone and informed headquarters that explosives would not be needed, as the camp had already been blown up, which was not true.

A detachment of troops of the U.S. 9th Armored Infantry Battalion, from the 6th Armored Division, part of the U.S. Third Army, and under the command of

According to Teofil Witek, a fellow Polish prisoner who witnessed the transmissions, Damazyn fainted after receiving the message.

As American forces closed in, Gestapo headquarters at Weimar telephoned the camp administration to announce that it was sending explosives to blow up any evidence of the camp, including its inmates. The Gestapo did not know that the administrators had already fled. A prisoner answered the phone and informed headquarters that explosives would not be needed, as the camp had already been blown up, which was not true.

A detachment of troops of the U.S. 9th Armored Infantry Battalion, from the 6th Armored Division, part of the U.S. Third Army, and under the command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

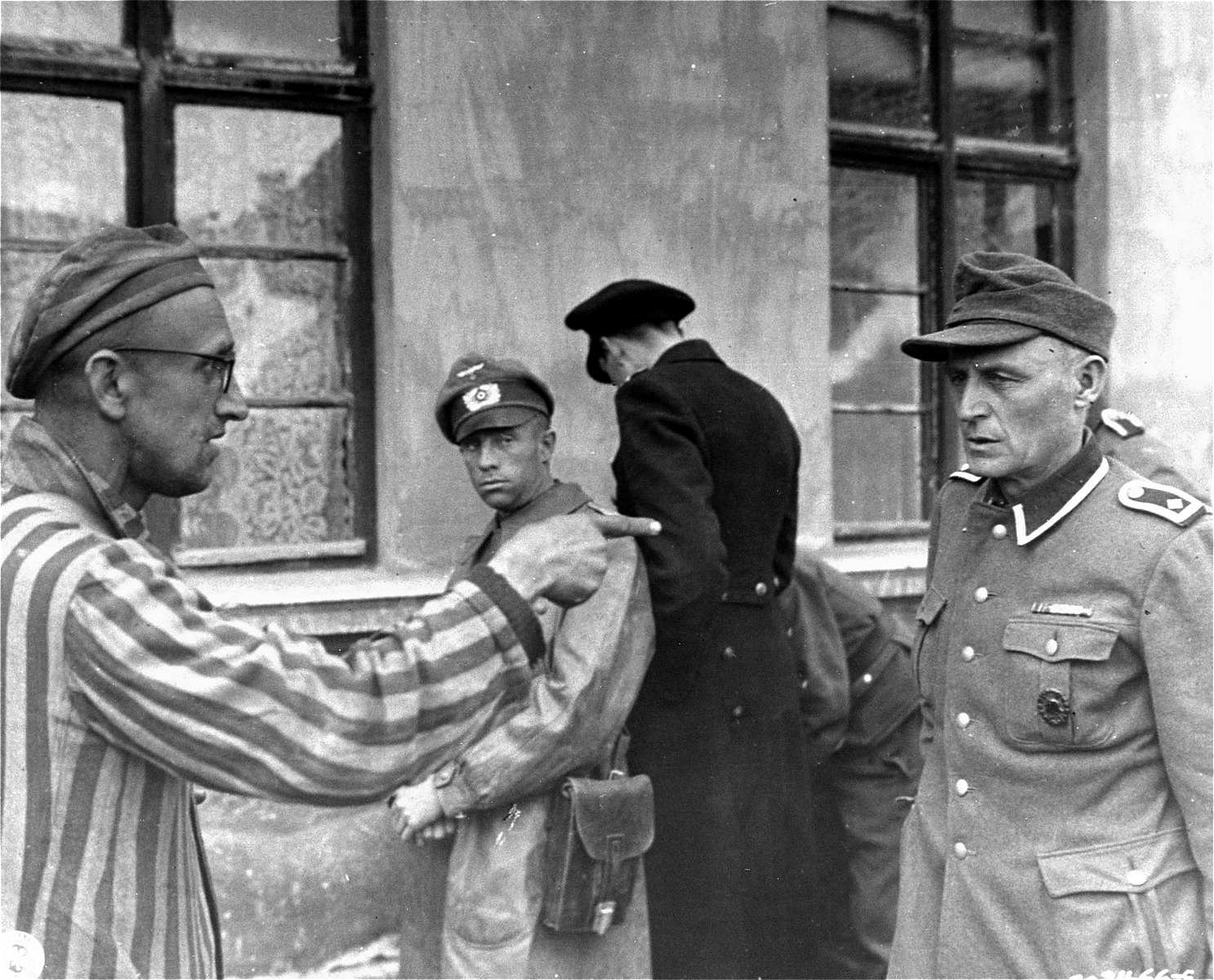

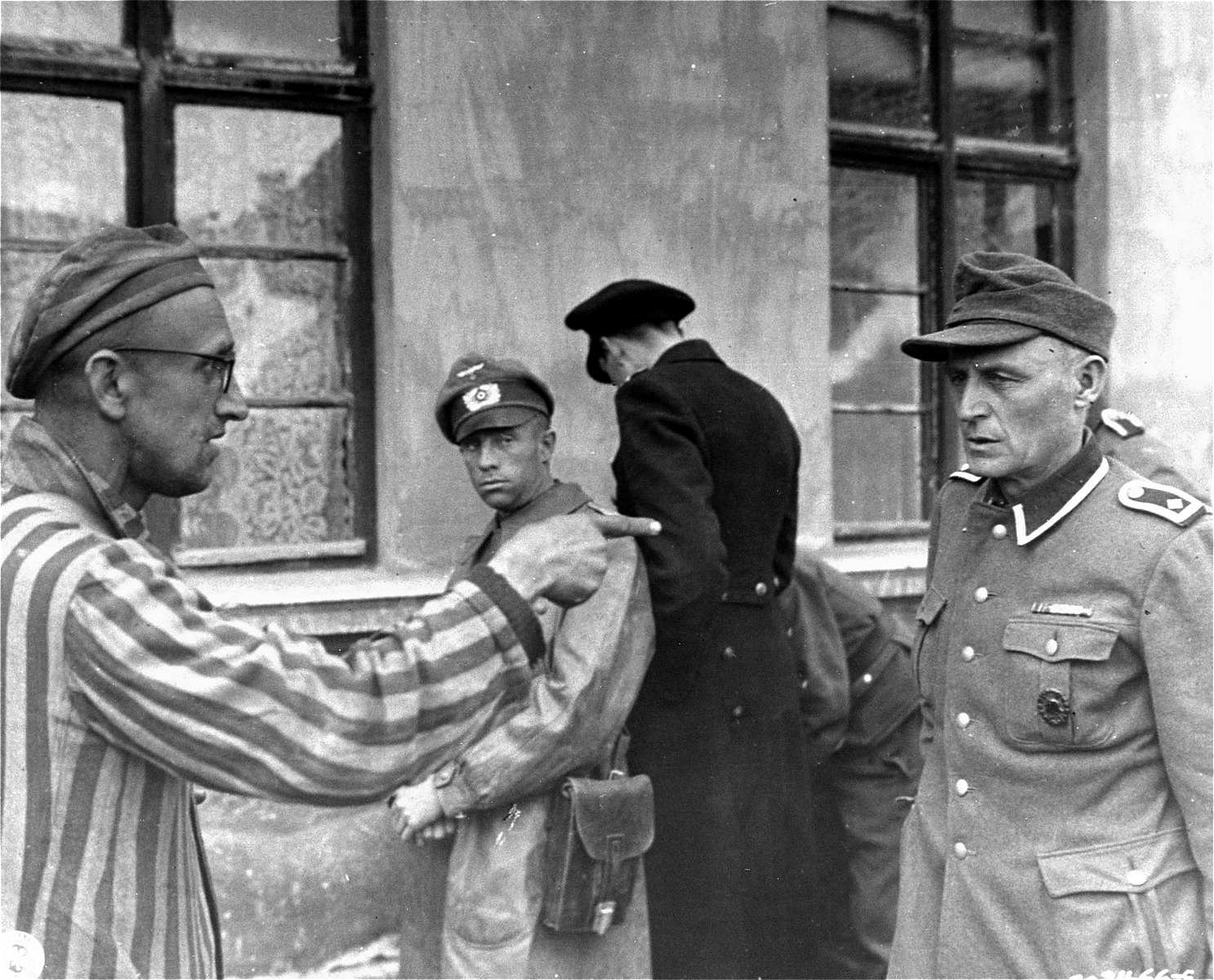

Frederic Keffer, arrived at Buchenwald on 11 April 1945 at 3:15 p.m. (now the permanent time of the clock at the entrance gate). The soldiers were given a hero's welcome, with the emaciated survivors finding the strength to toss some liberators into the air in celebration.

Later in the day, elements of the U.S. 83rd Infantry Division overran Langenstein, one of a number of smaller camps comprising the Buchenwald complex. There, the division liberated over 21,000 prisoners, ordered the mayor of Langenstein to send food and water to the camp, and hurried medical supplies forward from the 20th Field Hospital.

Third Army Headquarters sent elements of the 80th Infantry Division to take control of the camp on the morning of Thursday 12 April 1945. Several journalists arrived on the same day, perhaps with the 80th, including Edward R. Murrow

Edward Roscoe Murrow (born Egbert Roscoe Murrow; April 25, 1908 – April 27, 1965) was an American Broadcast journalism, broadcast journalist and war correspondent. He first gained prominence during World War II with a series of live radio broa ...

, whose radio report of his arrival and reception was broadcast on CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS (an abbreviation of its original name, Columbia Broadcasting System), is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainme ...

and became one of his most famous:

Civilian tour

After Patton toured the camp, he ordered the mayor of Weimar to bring 1,000 citizens to Buchenwald; these were to be predominantly men of military age from the middle and upper classes. The Germans had to walk roundtrip under armed American guard and were shown the crematorium and other evidence of Nazi atrocities. The Americans wanted to ensure that the German people would take responsibility for Nazi crimes, instead of dismissing them asatrocity propaganda

Atrocity propaganda is the spreading of information about the crimes committed by an enemy, which can be factual, but often includes or features deliberate fabrications or exaggerations. This can involve photographs, videos, illustrations, interv ...

. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower also invited two groups of Americans to tour the camp in mid-April 1945; journalists and editors from some of the principal U.S. publications, and then a dozen members of the Congress from both the House and the Senate, led by Senate Majority Leader Alben W. Barkley.

War correspondent Osmar White reported that above the crematorium door was a verse beginning 'Worms shall not devour me, but flames consume this body. I always loved the heat and light…'.

Aftermath

Buchenwald trial

Thirty SS perpetrators at Buchenwald were tried before a US military tribunal in 1947, includingHigher SS and Police Leader

The title of SS and Police Leader (') designated a senior Nazi Party official who commanded various components of the SS and the German uniformed police ('' Ordnungspolizei''), before and during World War II in the German Reich proper and in the ...

Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck und Pyrmont, who oversaw the SS district that Buchenwald was located in, and many of the doctors responsible for Nazi human experimentation. Almost all of the defendants were convicted, and 22 were sentenced to death. However, only nine death sentences were carried out, and by the mid-1950s, all perpetrators had been freed except for Ilse Koch

Ilse Koch (22 September 1906 – 1 September 1967) was a German war criminal who committed atrocities while her husband Karl-Otto Koch was commandant at Buchenwald concentration camp, Buchenwald. Though Ilse Koch had no official position in the N ...

, who was tried by a West German

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republic after its capital c ...

court and given a life sentence. Additional perpetrators were tried before German courts during the 1960s.

The site

Between August 1945 and 1 March 1950, Buchenwald was the site of NKVD special camp Nr. 2, where theSoviet secret police

There were a succession of Soviet secret police agencies over time. The Okhrana was abolished by the Provisional government after the first revolution of 1917, and the first secret police after the October Revolution, created by Vladimir Leni ...

imprisoned former Nazis and anti-communist dissidents. According to Soviet records, 28,455 people were detained, 7,113 of whom died. After the NKVD camp closed, much of the camp was razed, while signs were erected to provide a Soviet interpretation of the camp's legacy. The first monument to victims was erected by Buchenwald inmates days after the initial liberation. It was made of wood and only intended to be temporary. A second monument to commemorate the dead was erected in 1958 by the German Democratic Republic

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

(GDR) government near the mass graves. It was inaugurated on 14 September 1958 by GDR Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl

Otto Emil Franz Grotewohl (; 11 March 1894 – 21 September 1964) was a German politician who served as the first prime minister of the German Democratic Republic (GDR/East Germany) from its founding in October 1949 until his death in Septembe ...

. Inside the camp, there is a stainless steel monument on the spot where the first, temporary monument stood. Its surface is maintained at , the temperature of human skin, all year round.

The three National Memorials of the GDR, built next to or on the sites of the former concentration camps Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, and Ravensbrück, played a central role in the GDR's remembrance policy under Erich Honecker

Erich Ernst Paul Honecker (; 25 August 1912 – 29 May 1994) was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1971 until shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. He held the post ...

. They were controlled by the Ministry of Culture and thus by the government. According to their statute, these memorials served as places of identification and legitimisation of the GDR. The political instrumentalisation of these memorials, especially for the current needs of the GDR, became particularly clear during the major celebrations of the liberation of the concentration camps, as historian Anne-Kathleen Tillack-Graf analysis in her thesis about the official party newspaper .

Today the Buchenwald camp site serves as a Holocaust memorial. It has a museum with permanent exhibitions about the history of the camp. It is managed by Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation, which also looks after the camp memorial at Mittelbau-Dora

Mittelbau-Dora (also Dora-Mittelbau and Nordhausen-Dora) was a Nazi concentration camp located near Nordhausen in Thuringia, Germany. It was established in late summer 1943 as a subcamp of Buchenwald concentration camp, supplying slave labour f ...

.

Literature

Survivors who have written about their camp experiences includeJorge Semprún

Jorge Semprún Maura (; 10 December 1923 – 7 June 2011) was a Spanish writer and politician who lived in France most of his life and wrote primarily in French. From 1953 to 1962, during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, Semprún lived cla ...

, who in ''Quel beau dimanche!'' describes conversations involving Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

and Léon Blum

André Léon Blum (; 9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister of France. As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of socialist l ...

, and Ernst Wiechert, whose ''Der Totenwald'' was written in 1939 but not published until 1945, and which likewise involved Goethe. Scholars have investigated how camp inmates used art to help deal with their circumstances, and according to Theodor Ziolkowski

Theodore Ziolkowski (September 30, 1932 – December 5, 2020) was a scholar in the fields of German studies and comparative literature. He coined the term "Fifth gospel (genre), fifth gospel genre".

Early life

Theodore J. Ziolkowski was born on ...

writers often did so by turning to Goethe. Artist Léon Delarbre sketched, besides other scenes of camp life, the Goethe Oak, under which he used to sit and write. One of the few prisoners who escaped from the camp, the Belgian Edmond Vandievoet, recounted his experiences in a book whose English title is "I escaped from a Nazi Death Camp" ditions Jourdan, 2015 In his work ''Night

Night, or nighttime, is the period of darkness when the Sun is below the horizon. Sunlight illuminates one side of the Earth, leaving the other in darkness. The opposite of nighttime is daytime. Earth's rotation causes the appearance of ...

'', Elie Wiesel

Eliezer "Elie" Wiesel (September 30, 1928 – July 2, 2016) was a Romanian-born American writer, professor, political activist, List of Nobel Peace Prize laureates#1980, Nobel laureate, and Holocaust survivor. He authored Elie Wiesel bibliogra ...

talks about his stay in Buchenwald, including his father's death. Jacques Lusseyran, a leader in the underground resistance to the German occupation of France, was eventually sent to Buchenwald after being arrested, and described his time there in his autobiography.

Visit from President Obama and Chancellor Merkel

On 5 June 2009U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

and German Chancellor Angela Merkel

Angela Dorothea Merkel (; ; born 17 July 1954) is a German retired politician who served as Chancellor of Germany from 2005 to 2021. She is the only woman to have held the office. She was Leader of the Opposition from 2002 to 2005 and Leade ...

visited Buchenwald after a tour of Dresden Castle and Dresden Frauenkirche, Church of Our Lady. During the visit they were accompanied by Elie Wiesel

Eliezer "Elie" Wiesel (September 30, 1928 – July 2, 2016) was a Romanian-born American writer, professor, political activist, List of Nobel Peace Prize laureates#1980, Nobel laureate, and Holocaust survivor. He authored Elie Wiesel bibliogra ...

and Bertrand Herz, both survivors of the camp. , the director of the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation and honorary professor of University of Jena, guided the four guests through the remainder of the site of the camp. During the visit Wiesel, who together with Herz were sent to the Little camp as 16-year-old boys, said, "if these trees could talk." His statement marked the irony about the beauty of the landscape and the horrors that took place within the camp. President Obama mentioned during his visit that he had heard stories as a child from his great uncle, who was part of the 89th Division (United States), 89th Infantry Division, the first Americans to reach the camp at Ohrdruf, one of Buchenwald's satellites. Obama was the first sitting US President to visit the Buchenwald concentration camp.

See also

* Buchenwald Resistance * List of subcamps of Buchenwald * Number of deaths in Buchenwald * Ohrdruf forced labor camp * Persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses in Nazi Germany * ''The Boys of Buchenwald'' * List of prisoners of BuchenwaldReferences

Sources *Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, 1983 edition

* * * * * * * * * *Tillack-Graf, Anne-Kathleen (2012). ''Erinnerungspolitik der DDR. Dargestellt an der Berichterstattung der Tageszeitung "Neues Deutschland" über die Nationalen Mahn- und Gedenkstätten Buchenwald, Ravensbrück und Sachsenhausen.'' Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main. ISBN 978-3-631-63678-7. * * *

Further reading

* Knigge, Volkhard und Ritscher, Bodo: ''Totenbuch. Speziallager Buchenwald 1945–1950'', Weimar: Stiftung Gedenkstätten Buchenwald und Mittelbau Dora, 2003. * Tillack-Graf, Anne-Kathleen: ''Erinnerungspolitik der DDR. Dargestellt an der Berichterstattung der Tageszeitung "Neues Deutschland" über die Nationalen Mahn- und Gedenkstätten Buchenwald, Ravensbrück und Sachsenhausen.'' Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-631-63678-7.External links

* * Hardy GraupnerSurvivors, academics recall dark episode in Germany's postwar history

Deutsche Welle, 16 February 2010.

Guide to the Concentration Camps Collection

Leo Baeck Institute, New York City 2013. Includes extensive reports on Buchenwald collected by the Allied forces shortly after liberating the camp in April 1945.

Holocaust Buchenwald Concentration Camp Uncovered (1945) , British Pathé

on YouTube {{DEFAULTSORT:Buchenwald Concentration Camp Buchenwald concentration camp, 1937 establishments in Germany Buildings and structures in Weimar Museums in Thuringia Monuments and memorials to the victims of Nazism World War II museums in Germany 1950 disestablishments in Germany