Brian O'Rourke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Brian O'Rourke (; c. 1540 – 1591) was first king and then lord of West Bréifne in the west of Ireland from 1566 until his execution in 1591. He reigned during the later stages of the

Under the government of Perrot's successor as Lord Deputy, Sir William Fitzwilliam, pressure was increased on the territories bordering the province of

Under the government of Perrot's successor as Lord Deputy, Sir William Fitzwilliam, pressure was increased on the territories bordering the province of

O'Rourke was transferred to the

O'Rourke was transferred to the

Annals of the Four Masters, Vol. 6. 1591.1

/ref> reads: He remains an influential figure in the struggle of Irish lords against English expansionism in the 16th century, and was an early precursor to the generation of Irish nobles who would combat the English in the Nine Years War, which heralded the end of Gaelic Ireland. O'Rourke remains one of the most common surnames within

Tudor conquest of Ireland

Ireland was conquered by the Tudor monarchs of England in the 16th century. The Anglo-Normans had Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, conquered swathes of Ireland in the late 12th century, bringing it under Lordship of Ireland, English rule. In t ...

and his rule was marked by English encroachments on his lands. Despite being knighted by the English in 1585, he would later be proclaimed a rebel and forced to flee his kingdom in 1590. He travelled to Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

in early 1591 seeking assistance from King James VI, however, he was to become the first man extradited

In an extradition, one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdic ...

within Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

on allegations of crimes committed in Ireland and was sentenced to death in London in November 1591.

Early life

O'Rourke was a member of one ofGaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

's foremost dynasties, and was remarked upon as a handsome and unusually learned and well-educated Gaelic lord. The clan's territory was centred on the banks of Lough Gill

Lough Gill () is a freshwater lough (lake) mainly situated in County Sligo, but partly in County Leitrim, in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Lough Gill provides the setting for William Butler Yeats' poem "The Lake Isle of Innisfree".

Location a ...

and in the area of Dromahair in West Bréifne in the west of Ireland. Foundations of the O'Rourke tower house

A tower house is a particular type of stone structure, built for defensive purposes as well as habitation. Tower houses began to appear in the Middle Ages, especially in mountainous or limited access areas, to command and defend strategic points ...

within its bawn

A bawn is the defensive wall surrounding an Irish tower house. It is the anglicised version of the Irish word ''bábhún'' (sometimes spelt ''badhún''), possibly meaning "cattle-stronghold" or "cattle-enclosure".See alternative traditional s ...

wall and circular moat can be seen today at Parke's Castle, close to Dromahair.

He assumed leadership of his Irish clan

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century. A clan (or in Irish, plural ) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives; howe ...

in the mid-1560s having assassinated his elder brothers, but his territory of West Bréifne on the border of Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

soon came under the administration of the newly created Presidency of Connacht

Connacht or Connaught ( ; or ), is the smallest of the four provinces of Ireland, situated in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, C ...

.

Although the English knighted O'Rourke, in time they became unsettled by him. The English Lord Deputy, Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586) was an English soldier, politician and Lord Deputy of Ireland.

Background

He was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst (1482 – 11 February 1553) and Anne Pakenham (1511 – 22 Oc ...

, described him in 1575 as the proudest man he had dealt with in Ireland. Similarly, the Lord President of Connaught

The Lord President of Connaught was a military leader with wide-ranging powers, reaching into the civil sphere, in the English government of Connacht, Connaught in Ireland, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The office was created in 1569 ...

, Sir Nicholas Malby

Sir Nicholas Malby (1530?–1584) was an English soldier active in Ireland, Lord President of Connaught from 1579 to 1581.

Life

He was born probably about 1530. In 1556 his name appears in a list of persons willing to take part in the plantatio ...

, put him down as, "''the proudest man this day living on the earth''". A decade later, Sir Edward Waterhouse thought of him as, "''being somewhat learned but of an insolent and proud nature and no further obedient than is constrained by her Majesty's forces''".

Connacht

O'Rourke was willing to deal with the government, and in an agreement concluded with Malby in 1577 he recognised the sovereignty of the Irish crown underElizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

. But his allegiance was called in question within two years, during the Second Desmond Rebellion

The Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–1583) was the more widespread and bloody of the two Desmond Rebellions in Ireland launched by the FitzGerald Dynasty of County Desmond, Desmond in Munster against English rule. The second rebellion began in ...

in Munster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

, when he rose out in defiance of the Connacht presidency. It was suspected his actions were induced by an involvement with the Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

family of the Dillons in adjacent Meath, who were engaged in an effort to spread their influence and possessions in the northern midlands, rather than by outright collusion in the rebel Geraldine cause. A further factor was almost certainly the August 1579 torture and execution of his son, Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

Friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

Conn Ó Ruairc, by Tudor Army troops outside the city walls of Kilmallock

Kilmallock () is a town in south County Limerick, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, near the border with County Cork, 30 km south of Limerick city. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King John's Castle (Kilmallock), King's Castle (or K ...

under orders from Sir William Drury. Both Friar Conn and his companion in death, Bishop Pádraig Ó hÉilí, were Beatified

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the ...

in 1992 by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

, along with 15 other Irish Catholic Martyrs.

Sir Richard Bingham took up the presidency of Connacht in 1584, when Sir John Perrot was appointed lord deputy of Ireland. Ó Ruairc immediately complained of harassment by the new president in the spring and summer of that year, and in September Bingham was ordered by his superior in Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

to temporise and refrain from making expeditions into Bréifne. Although part of the province of Connacht

Connacht or Connaught ( ; or ), is the smallest of the four provinces of Ireland, situated in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, C ...

, the territory was not subject to a Crown sheriff, and O'Rourke was happy to preserve his freedom of action. He did maintain relations with the Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

government by his attendance at the opening of parliament in 1585, where he was noted to have dressed all in black in the company of his strikingly beautiful wife.

In preparation for the Composition of Connacht, whereby the lords of that province were to enter an agreement with the government to regularise their standing, O'Rourke surrendered his lordship in 1585. He was thus due to receive a regrant of his lands by knight-service

Knight-service was a form of feudal land tenure under which a knight held a fief or estate of land termed a knight's fee (''fee'' being synonymous with ''fief'') from an overlord conditional on him as a tenant performing military service for his ...

in return for a chief horse and an engraved gold token to be presented to the lord deputy each year at midsummer. It seemed a balanced compromise, but O'Rourke declined to accept the letters patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

and never regarded his terms as binding.

By May 1586 the tension with the president had mounted, and O'Rourke brought charges against him before the council at Dublin, which were dismissed as vexatious. Bingham believed that Perrot had been behind this attempt on his authority, but there was little he could do before his recall to England for service in the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

in 1587; upon the president's departure (he was to return within a year), Perrot slashed O'Rourke's annual composition dues and, while permitting him to levy certain illegal exactions, appointed the Lord of West Bréifne sheriff of Leitrim for a term of two years.

Rebellion

O'Rourke remained unhappy with English interference in his territories, and he was also content to be described as a leading Catholic lord. After Perrot's departure, he assisted at least eighty survivors of theSpanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

– including Francisco de Cuellar – to depart the country in the winter of 1588, and was regarded as friendly to future receptions of Spanish forces. Although not proclaimed as a rebel, he put up a forcible resistance to the presidency – again under Binghams's command – and would not be bridled.

O'Rourke's demands against the government grew with the violence on the borders of West Bréifne. In peace talks in 1589, he did accept the terms of a Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, parti ...

tribute that had been agreed upon by his grandfather, but resisted the composition terms of 1585 and refused to allow the formation of a Crown administration in the new County Leitrim

County Leitrim ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht and is part of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the village of Leitrim, County Leitr ...

. Instead, he sought appointment as seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

under the direct authority of the Dublin government, leaving him independent of Bingham. He also sought safe possession of his lands, safe conduct for life, and a guarantee of freedom from harassment by the president's forces of any merchants entering his territory. In return, the only pledge he was willing to give was his word. A member of the Dublin council, Sir Robert Dillon of the County Meath

County Meath ( ; or simply , ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. It is bordered by County Dublin to the southeast, County ...

family, advised him to stay out – intimating that O'Rourke would be taken into custody if he came in and submitted to crown authority – and O'Rourke declined the government's offers.

Flight and extradition

Under the government of Perrot's successor as Lord Deputy, Sir William Fitzwilliam, pressure was increased on the territories bordering the province of

Under the government of Perrot's successor as Lord Deputy, Sir William Fitzwilliam, pressure was increased on the territories bordering the province of Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

. Thus, in the spring of 1590, Bingham's forces occupied west Breifne and O'Rourke fled; later that year the adjacent territory of County Monaghan

County Monaghan ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is part of Border Region, Border strategic planning area of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town ...

was seized by the Crown after the execution at law of the resident lord, Hugh Roe MacMahon.

O'Rourke fetched up in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

in February 1591, with "six fair Irish hobbies and four great dogs to be presented to the king". He was seeking not only asylum but also the opportunity to recruit mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

to contest the occupation of his territories. In consultation with the English ambassador Robert Bowes, King James VI denied him an audience, and Queen Elizabeth (relying on the Treaty of Berwick (1586)) made a strong request for the delivery of O'Rourke into her custody.

The matter was put to the Scottish Privy Council

The Privy Council of Scotland ( — 1 May 1708) was a body that advised the Scottish monarch. During its existence, the Privy Council of Scotland was essentially considered as the government of the Kingdom of Scotland, and was seen as the most ...

, which readily ordered – in the face of some objections – the arrest and delivery to English crown forces of the rebel Irish lord. Elizabeth's councillors had explicitly held out the prospect of clemency for O'Rourke, and certain Scots councillors agreed to the extradition, in the supposed expectation that his life would be spared. The expectation was to be disappointed, an experience the king himself suffered in the years afterwards, when extradition requests for followers of the Earl of Bothwell were denied by the English.

O'Rourke was arrested in Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, where the townsmen sought a stay on his delivery into custody, fearing for their Irish trade. The denial of their request caused an outcry, and the king's officers John Carmichael and William Stewart of Blantyre were cursed as "Queen Elizabeth's knights" with the allegation that the Scottish king had been bought with English angels

An angel is a spiritual (without a physical body), heavenly, or supernatural being, usually humanoid with bird-like wings, often depicted as a messenger or intermediary between God (the transcendent) and humanity (the profane) in variou ...

(a reference to the pension the king received from England). Several of O'Rourke's creditors feared that his debts would go unpaid, but the English ambassador made a contribution of £47. O'Rourke was removed from Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

in the afternoon of 3 April 1591 in the midst of a riot. Two ships on the west coast were looted, and, after some crews had been killed by Irishmen in protest at O'Rourke's treatment, guards had to be mounted on all vessels sailing to Ireland.

Trial and execution

O'Rourke was transferred to the

O'Rourke was transferred to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

, where he was kept in close custody as the legal argument began. Although treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

trials in the Tudor period had more to do with political theatre than the administration of justice, the matter was not a foregone conclusion: there was a serious question over whether O'Rourke could be tried in England for treason committed in Ireland. The judges delivered a mixed, preliminary opinion, that the trial could go ahead under a treason statute enacted under King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

.

Meanwhile, articles had been framed at Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

against O'Rourke with the reluctant aid of Bingham (curiously, he complained of being bullied into his testimony), and there was also an indictment laid by a jury in Sligo

Sligo ( ; , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of 20,608 in 2022, it is the county's largest urban centre (constituting 2 ...

. These matters were transferred to England, where the grand jury of Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

found evidence of various offences of treason, the most substantial of which concerned the assistance given to Armada survivors, the attempt to raise mercenaries in Scotland, and various armed raids made by O'Rourke into counties Sligo

Sligo ( ; , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of 20,608 in 2022, it is the county's largest urban centre (constituting 2 ...

and Roscommon

Roscommon (; ; ) is the county town and the largest town in County Roscommon in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is roughly in the centre of Ireland, near the meeting of the N60 road (Ireland), N60, N61 road (Ireland), N61 and N63 road (Irelan ...

. There was one further charge that related to an odd incident in 1589, when a representation of the Queen (whether a wood carving or painting is not known) was said to have been tied to a horse's tail at O'Rourke's command and dragged in the mud. This was referred to as the ''treason of the image'', but it has been suggested that it was merely an ancient new year's ritual, deliberately misconstrued for the benefit of the indictment process.

O'Rourke was arraigned on 28 October 1591 and the indictment was translated for him into Irish by a native speaker. One observer said he declined to plead, but the record states that a plea of not guilty was entered (probably at the direction of the court). The defendant was asked how he wished to be tried and answered that he would submit to trial by jury if he were given a week to examine the evidence, then allowed a good legal advocate, and only if the Queen herself sat in judgment. The judge declined these requests and explained that the jury would try him anyway. O'Rourke responded, "''If they thought good, let it be so''". The trial proceeded and O'Rourke was convicted and sentenced to death.

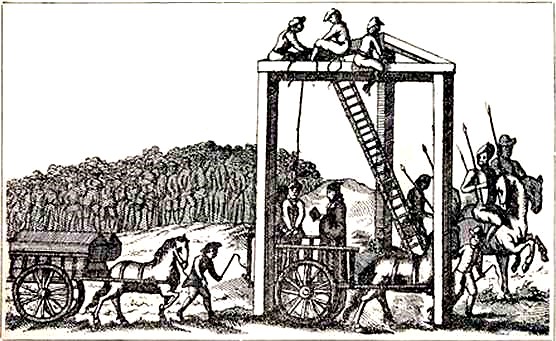

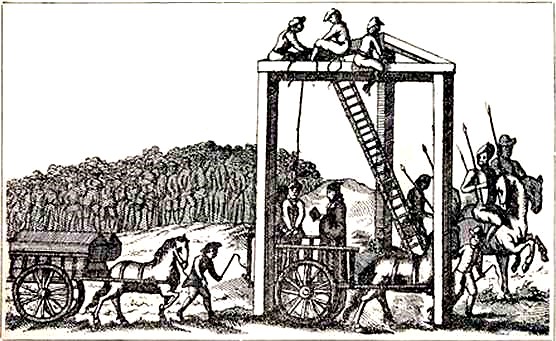

On 3 November 1591, O'Rourke was drawn to Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in London, Middlesex, England, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone. Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne ...

. On the scaffold Miler Magrath, Archbishop of Cashel

The Archbishop of Cashel () was an archiepiscopal title which took its name after the town of Cashel, County Tipperary in Ireland. Following the Reformation, there had been parallel apostolic successions to the title: one in the Catholic Church ...

, sought the repentance of the condemned man's sins. In response, he was abused by O'Rourke with jibes over his uncertain faith and credit and dismissed as a man of depraved life who had broken his vow by abjuring the rule of the Franciscans

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest conte ...

. O'Rourke then suffered execution of sentence by hanging and quartering.

In his essay on ''Customs'', Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

refers to an Irish rebel hanged in London, who requested that the sentence be carried out, not with a rope halter, but with a willow – a common instrument amongst the Irish: it is probable that O'Rourke was the rebel referred to.

Legacy

O'Rourke's experience as a rebel Irish lord is not remarkable in itself. What is remarkable is the combination used in his downfall: first, the campaign conducted under Fitzwilliam to bring pressure to bear on the borders of Ulster; and then the co-operation of the Scots king with the English, resulting in the firstextradition

In an extradition, one Jurisdiction (area), jurisdiction delivers a person Suspect, accused or Conviction, convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforc ...

within Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

and a trial for treason committed "''beyond the seas''". Evidence of his treason was used in the trial of Perrot later in the year, which also resulted in a conviction, and the subsequent pursuit of an aggressive policy against the lords of Ulster led to the outbreak of the Nine Years War. In the end, O'Rourke had fallen prey to forces that were moving to establish a new polity in Britain, of which James VI became the first monarch little more than a decade later.

His eulogy, as recorded in the Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' () or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' () are chronicles of Middle Ages, medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Genesis flood narrative, Deluge, dated as 2,242 Anno Mundi, years after crea ...

,/ref> reads: He remains an influential figure in the struggle of Irish lords against English expansionism in the 16th century, and was an early precursor to the generation of Irish nobles who would combat the English in the Nine Years War, which heralded the end of Gaelic Ireland. O'Rourke remains one of the most common surnames within

County Leitrim

County Leitrim ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht and is part of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the village of Leitrim, County Leitr ...

to this day. As a homage to the legacy of the historic kings of West Breifne

The Kingdom of West Breifne (Irish: ''Breifne Ua Ruairc'') or Breifne O'Rourke was a historic kingdom of Ireland that existed from 1256 to 1605, located in the area that is now County Leitrim. It took its present boundaries in 1583 when West Br ...

, the county's coat of arms features the defaced crest of the O'Rourke clan.

Family

Brian O'Rourke had at least six known children - Eóghan, Brian Óg,Tadhg

Tadhg, also Taḋg ( , ), (pronunciations given for the name ''Tadhg'' separately from those for the slang/pejorative ''Teague''.) commonly anglicized as Taig, "Taig" or "Teague", is an Irish language, Irish and Scottish Gaelic masculine name t ...

, Art, Eogan and Mary.

O'Rourke's first two children were by Annalby O'Crean. She is described as being the wife of a Sligo merchant and it is not known whether she and Brian were ever officially married. They had two known children - Eóghan, born in 1562, and Brian Óg, born in 1568.

Brian's first recorded marriage was to Lady Mary Burke (a daughter of the second Earl of Clanricarde). They had three known children - Tadhg, born in 1576, and two other sons named Art and Eogan. O'Rourke and Burke separated sometime prior to 1585 but were never formally divorced. Tadhg, and possibly their other children, continued to live with their mother in County Galway

County Galway ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region, taking up the south of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. The county population was 276,451 at the 20 ...

following the separation.

O'Rourke later married Elenora, daughter of James FitzGerald, 14th Earl of Desmond and they had a daughter, Mary, who married Sir Hugh O'Conor, O'Conor Don. They later separated and Elenora remarried. She died in the spring of 1589. Based on accounts from Francisco de Cuellar who spent the Autumn of 1588 at O'Rourke's castle, Brian appears to have remarried once more, his wife being described by de Cuellar as "''beautiful in the extreme''".

References

Bibliography

* * * * *''Dictionary of National Biography'' 60 vols. (London, 2004). {{DEFAULTSORT:ORourke, Brian 1540s births 1591 deaths 16th-century Irish monarchs Executed people from County Leitrim People extradited to England Irish knights Irish lords People executed under Elizabeth I by hanging, drawing and quartering People executed under the Tudors for treason against England People from County Leitrim People of Elizabethan Ireland People extradited from Scotland People from Dromahair Year of birth uncertain