Bills Of Attainder on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder, writ of attainder, or bill of pains and penalties) is an act of a

The

The

British Impeachment and Attainder

* ttp://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/data/constitution/article01/47.html Extended annotation at FindLaw* Mention of Attainder in the Federalist Papers by

Federalist 43Federalist 44

and by

Federalist 84

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bill Of Attainder Common law English legal terminology Legal history

legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and providing for a punishment, often without a trial. As with attainder

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

resulting from the normal judicial process, the effect of such a bill is to nullify the targeted person's civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

, most notably the right to own property (and thus pass it on to heirs), the right to a title of nobility, and, in at least the original usage, the right to life itself.

In the history of England

The territory today known as England became inhabited more than 800,000 years ago, as the discovery of stone tools and footprints at Happisburgh in Norfolk have indicated.; "Earliest footprints outside Africa discovered in Norfolk" (2014). BB ...

, the word "attainder

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

" refers to people who were declared "attainted", meaning that their civil rights were nullified: they could no longer own property or pass property to their family by will or testament. Attainted people would normally be punished by judicial execution, with the property left behind escheat

Escheat () is a common law doctrine that transfers the real property of a person who has died without heirs to the crown or state. It serves to ensure that property is not left in "limbo" without recognized ownership. It originally applied t ...

ed to the Crown or lord rather than being inherited by family. The first use of a bill of attainder was in 1321 against Hugh le Despenser, 1st Earl of Winchester and his son Hugh Despenser the Younger, Earl of Gloucester, who were both attainted for supporting King Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also known as Edward of Caernarfon or Caernarvon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir to the throne follo ...

. Bills of attainder passed in Parliament by Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

on 29 January 1542 resulted in the executions of a number of notable historical figures.

The use of these bills by Parliament eventually fell into disfavour due to the potential for abuse and the violation of several legal principles, most importantly the right to due process

Due process of law is application by the state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to a case so all legal rights that are owed to a person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual p ...

, the precept that a law should address a particular form of behaviour rather than a specific individual or group, and the separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

, since a bill of attainder is necessarily a judicial

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

matter. The last use of attainder was in 1798 against Lord Edward FitzGerald for leading the Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 (; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ''The Turn out'', ''The Hurries'', 1798 Rebellion) was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The m ...

. The House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

later passed the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820

The Pains and Penalties Bill 1820 was a bill introduced to the British Parliament in 1820, at the request of King George IV, which aimed to dissolve his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick, and deprive her of the title of queen.

George and Caroline ...

, which attempted to attaint Queen Caroline, but it was not considered by the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

. No bills of attainder have been passed since 1820 in the UK. Attainder remained a legal consequence of convictions in courts of law, but this ceased to be a part of punishment in 1870.

American dissatisfaction with British attainder laws resulted in their being prohibited in the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

in 1789. Bills of attainder are forbidden to both the federal government and the states, reflecting the importance that the Framers

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. While the convention was initially intended to revise the league of states and devise the first system of Federal government of the United States, fede ...

attached to this issue. Every state constitution also expressly forbids bills of attainder. The U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

has invalidated laws under the Attainder Clause on five occasions. Most common-law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prec ...

nations have prohibited bills of attainder, some explicitly and some implicitly.

Jurisdictions

Australia

TheConstitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia (also known as the Commonwealth Constitution) is the fundamental law that governs the political structure of Australia. It is a written constitution, which establishes the country as a Federation of Australia, ...

contains no specific provision permitting the Commonwealth Parliament to pass bills of attainder. The High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the apex court of the Australian legal system. It exercises original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified in the Constitution of Australia and supplementary legislation.

The High Court was establi ...

has ruled that federal bills of attainder are unconstitutional, because it is a violation of the separation of powers doctrine for any body to wield judicial power other than a Chapter III courtthat is, a body exercising power derived from Chapter III of the Constitution, the chapter providing for judicial power.... One of the core aspects of judicial power is the ability to make binding and authoritative decisions on questions of law, that is, issues relating to life, liberty or property... The wielding of judicial power by the legislative or executive branch includes the direct wielding of power and the indirect wielding of judicial power..

The state constitutions in Australia

State constitutions in Australia are the legal documents that establish and define the structure, powers, and functions of the six state governments in Australia.

Each state constitution preceded the federal Constitution of Australia as the con ...

contain few limitations on government power. Bills of attainder are considered permissible because there is no entrenched separation of powers at the state level. However, section 77 of the Constitution of Australia permits state courts to be invested with Commonwealth jurisdiction, and any state law that renders a state court unable to function as a Chapter III court is unconstitutional. The states cannot structure their legal systems to prevent them from being subject to the Australian Constitution.

An important distinction is that laws seeking to direct judicial power (e.g. must make orders) are unconstitutional, but laws that concern mandatory sentencing, rules of evidence, non-punitive imprisonment, or tests, are constitutional.

State parliaments are, however, free to prohibit parole boards from granting parole to specific prisoners. For instance, sections 74AA and 74AB of the Corrections Act 1986 in Victoria significantly restrict the ability of the parole board to grant parole to Julian Knight or Craig Minogue. These have been upheld by the High Court of Australia and are distinguished from bills of attainder since the original sentence (life imprisonment) stands; the only change is the administration of parole.

Canada

In two cases of attempts to pass bills (in 1984 for Clifford Olson and in 1995 for Karla Homolka) to inflict a judicial penalty on a specific person, the speakers of theHouse

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air c ...

and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, respectively, have ruled that Canadian parliamentary practice does not permit bills of attainder or bills of pains and penalties.

United Kingdom

English law

The word "attainder

In English criminal law, attainder was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary titles, but ...

" is part of English common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

. Under English law, a criminal condemned for a serious crime, whether treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

or felony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "''félonie''") to describe an offense that r ...

(but not misdemeanour

A misdemeanor (American English, spelled misdemeanour elsewhere) is any "lesser" criminal act in some common law legal systems. Misdemeanors are generally punished less severely than more serious felonies, but theoretically more so than admi ...

, which referred to less serious crimes), could be declared "attainted", meaning that his civil rights were nullified: he could no longer own property or pass property to his family by will or testament. His property could consequently revert to the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

or to the mesne lord

A mesne lord () was a lord in the feudal system who had vassals who held land from him, but who was himself the vassal of a higher lord. Owing to ''Quia Emptores'', the concept of a mesne lordship technically still exists today: the partitionin ...

. Any peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes Life peer, non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted Imperial, royal and noble ranks, noble ranks.

Peerages include:

A ...

titles would also revert to the Crown. The convicted person would normally be punished by judicial executionwhen a person committed a capital crime and was put to death for it, the property left behind escheat

Escheat () is a common law doctrine that transfers the real property of a person who has died without heirs to the crown or state. It serves to ensure that property is not left in "limbo" without recognized ownership. It originally applied t ...

ed to the Crown or lord rather than being inherited by family. Attainder functioned more or less as the revocation of the feudal chain of privilege and all rights and properties thus granted.

Due to mandatory sentencing

Mandatory sentencing requires that people convicted of certain crimes serve a predefined term of imprisonment, removing the discretion of judges to take issues such as extenuating circumstances and a person's likelihood of rehabilitation into co ...

, the due process of the courts provided limited flexibility to deal with the various circumstances of offenders. The property of criminals caught alive and put to death because of a guilty plea or jury conviction on a not guilty plea could be forfeited, as could the property of those who escaped justice and were outlawed; but the property of offenders who died before trial, except those killed during the commission of crimes (who fell foul of the law relating to '' felo de se''), could not be forfeited, nor could the property of offenders who refused to plead and who were tortured to death through '' peine forte et dure''.

On the other hand, when a legal conviction did take place, confiscation and "corruption of blood" sometimes appeared unduly harsh for the surviving family. In some cases (at least regarding the peerage) the Crown would eventually re-grant the convicted peer's lands and titles to his heir. It was also possible, as political fortunes turned, for a bill of attainder to be reversed. This sometimes occurred long after the convicted person was executed.

Unlike the mandatory sentences of the courts, acts of Parliament provided considerable latitude in suiting the punishment to the particular conditions of the offender's family. Parliament could also impose non-capital punishments without involving courts; such bills are called bills of pains and penalties.

Bills of attainder were sometimes criticised as a convenient way for the king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

to convict subjects of crimes and confiscate their property without the bother of a trial – and without the need for a conviction or indeed any evidence at all. It was however relevant to the custom of the Middle Ages, where all lands and titles were granted by a king in his role as the "fount of honour

The fount of honour () is a person, who, by virtue of their official position, has the exclusive right of conferring legitimate titles of nobility and orders of chivalry on other persons.

Origin

During the High Middle Ages, European knights ...

". Anything granted by the king's wish could be taken away by him. This weakened over time as personal rights became legally established.

The first use of a bill of attainder was in 1321 against Hugh le Despenser, 1st Earl of Winchester and his son Hugh Despenser the Younger, Earl of Gloucester. They were both attainted for supporting King Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also known as Edward of Caernarfon or Caernarvon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir to the throne follo ...

during his struggle with the queen

Queen most commonly refers to:

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a kingdom

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen (band), a British rock band

Queen or QUEEN may also refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Q ...

and baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often Hereditary title, hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than ...

s.

In England, those executed subject to attainders include George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence (1478); Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; – 28 July 1540) was an English statesman and lawyer who served as List of English chief ministers, chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false cha ...

(1540); Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury (1540); Catherine Howard (1542); Thomas, Lord Seymour (1549); Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford (1641); Archbishop William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I of England, Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Caroline era#Religion, Charles I's religious re ...

of Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

(1645); and James Scott, Duke of Monmouth. In the 1541 case of Catherine Howard, King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

was the first monarch to delegate royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

, to avoid having to assent personally to the execution of his wife.

After defeating Richard III

Richard III (2 October 1452 – 22 August 1485) was King of England from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the Plantagenet dynasty and its cadet branch the House of York. His defeat and death at the Battle of Boswor ...

and replacing him on the throne of England following the Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field ( ) was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of House of Lancaster, Lancaster and House of York, York that extended across England in the latter half ...

, Henry VII had Parliament pass a bill of attainder against his predecessor. It is noteworthy that this bill made no mention of the Princes in the Tower

The Princes in the Tower refers to the mystery of the fate of the deposed King Edward V of England and his younger brother Prince Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, heirs to the throne of King Edward IV of England. The brothers were the only ...

, although it does declare him guilty of "shedding of Infants blood".

Although deceased by the time of the Restoration, the regicides John Bradshaw, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton (baptised 3 November 1611; died 26 November 1651) was an English general in the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and a son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell. He died of disease outside Limerick in November 165 ...

, and Thomas Pride were served with a bill of attainder on 15 May 1660 backdated to 1 January 1649 ( NS). After the committee stages, the bill passed both the Houses of Lords and Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons ...

and was engrossed on 4 December 1660. This was followed with a resolution that passed both Houses on the same day:

In 1685, when the Duke of Monmouth

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

landed in West England and started a rebellion in an effort to overthrow his uncle, the recently enthroned James II, Parliament passed a bill of attainder against him. After the Battle of Sedgemoor

The Battle of Sedgemoor was the last and decisive engagement between forces loyal to James II and rebels led by the Duke of Monmouth during the Monmouth rebellion, fought on 6 July 1685, and took place at Westonzoyland near Bridgwater in S ...

, this made it possible for King James to have the captured Monmouth put summarily to death. Though legal, this was regarded by many as an arbitrary and ruthless act.

In 1753, the Jacobite leader Archibald Cameron of Lochiel was summarily put to death on the basis of a seven-year-old bill of attainder, rather than being put on trial for his recent subversive activities in Scotland. This aroused some protests in British public opinion at the time, including from people with no Jacobite sympathies.

The last use of attainder was in 1798 against Lord Edward FitzGerald for leading the Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 (; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ''The Turn out'', ''The Hurries'', 1798 Rebellion) was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The m ...

.

The Great Act of Attainder

In 1688, KingJames II of England

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1 ...

(VII of Scotland), driven off by the ascent of William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 1662 – 28 December 1694) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland with her husband, King William III and II, from 1689 until her death in 1694. Sh ...

in the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

, came to Ireland with the sole purpose of reclaiming his throne. After his arrival, the Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland () was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until the end of 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two chambers: the Irish Hou ...

assembled a list of names in 1689 of those reported to have been disloyal to him, eventually tallying between two and three thousand, in a bill of attainder. Those on the list were to report to Dublin for sentencing. One man, Lord Mountjoy, was in the Bastille

The Bastille (, ) was a fortress in Paris, known as the Bastille Saint-Antoine. It played an important role in the internal conflicts of France and for most of its history was used as a state prison by the kings of France. It was stormed by a ...

at the time and was told by the Irish Parliament that he must break out of his cell and make it back to Ireland for his punishment, or face the grisly process of being drawn and quartered. The parliament became known in the 1800s as the "Patriot Parliament

Patriot Parliament is the name commonly used for the Irish Parliament session called by King James II during the Williamite War in Ireland which lasted from 1688 to 1691. The first since 1666, it held only one session, which lasted from 7 May ...

".

Later defenders of the Patriot Parliament pointed out that the ensuing " Williamite Settlement forfeitures" of the 1690s named an even larger number of Jacobite suspects, most of whom had been attainted by 1699.

Private bills

In theWestminster system

The Westminster system, or Westminster model, is a type of parliamentary system, parliamentary government that incorporates a series of Parliamentary procedure, procedures for operating a legislature, first developed in England. Key aspects of ...

(and especially in the United Kingdom), a similar concept is covered by the term "private bill" (a bill which upon passage becomes a private Act). Note however that "private bill" is a general term referring to a proposal for legislation applying to a specific person; it is only a bill of attainder if it punishes them; private bills have been used in some Commonwealth countries to effect divorce. Other traditional uses of private bills include chartering corporations, changing the charters of existing corporations, granting monopolies, approving of public infrastructure and seizure of property for those, as well as enclosure of commons and similar redistributions of property. Those types of private bills operate to take away private property and rights from certain individuals, but are usually not called "bill of pains and penalties". Unlike the latter, Acts appropriating property with compensation are constitutionally uncontroversial as a form of compulsory purchase.

The last United Kingdom bill called a "Pains and Penalties Bill" was the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820

The Pains and Penalties Bill 1820 was a bill introduced to the British Parliament in 1820, at the request of King George IV, which aimed to dissolve his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick, and deprive her of the title of queen.

George and Caroline ...

and was passed by the House of Lords in 1820, but not considered by the House of Commons; it sought to divorce Queen Caroline from King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

and adjust her titles and property accordingly, on grounds of her alleged adultery, as did many private bills dealing with divorces of private persons.

No bills of attainder have been passed since 1820 in the UK. Attainder as such remained a legal consequence of convictions in courts of law, but this ceased to be a part of punishment in 1870.

World War II

Previously secret British War Cabinet papers released on 1 January 2006 have shown that, as early as December 1942, the War Cabinet had discussed their policy for the punishment of the leadingAxis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

officials if captured. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

had then advocated a policy of summary execution

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

with the use of an act of attainder to circumvent legal obstacles. He was dissuaded by Richard Law, a junior minister at the Foreign Office, who pointed out that the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

still favoured trials.

United States

Colonial era

Bills of attainder were used throughout the 18th century in England, and were applied toBritish colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by England, and then Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English and later British Empire. There was usually a governor to represent the Crown, appointed by the British monarch on ...

as well. However, at least one American state, New York, used a 1779 bill of attainder to confiscate the property of British loyalists (called Tories) as both a penalty for their political sympathies and means of funding the rebellion. American dissatisfaction with British attainder laws resulted in their being prohibited in the U.S. Constitution ratified in 1787.

Constitutional bans

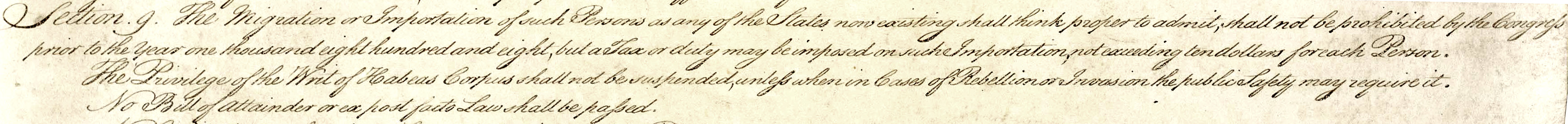

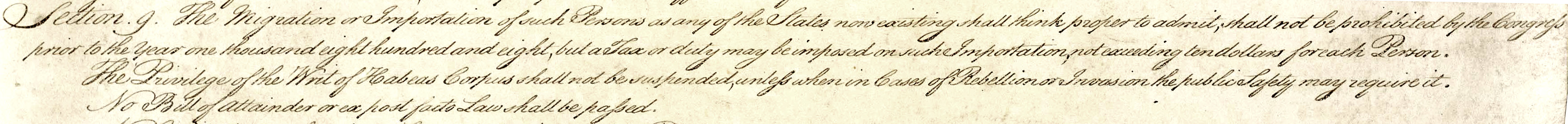

The

The United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

forbids legislative bills of attainder: in federal law under Article I, Section 9, Clause 3 ("No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed"), and in state law under Article I, Section 10. The fact that they were banned even under state law reflects the importance that the Framers

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. While the convention was initially intended to revise the league of states and devise the first system of Federal government of the United States, fede ...

attached to this issue.

Within the U.S. Constitution, the clauses forbidding attainder laws serve two purposes. First, they reinforce the separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

by forbidding the legislature to perform judicial

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

or executive functions, as a bill of attainder necessarily does. Second, they embody the concept of due process

Due process of law is application by the state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to a case so all legal rights that are owed to a person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual p ...

, which is reinforced by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

Every state constitution also expressly forbids bills of attainder. For example, Wisconsin's constitution Article I, Section 12 reads:

In contrast, the Texas Constitution omits the clause that applies to heirs. It is unclear whether a law that called for heirs to be deprived of their estate would be constitutional in Texas.

Supreme Court cases

TheU.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

has invalidated laws under the Attainder Clause on five occasions.

Two of the Supreme Court's first decisions on the meaning of the bill of attainder clause came after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. In ''Ex parte Garland

''Ex parte Garland'', 71 U.S. (4 Wall.) 333 (1867), was an important United States Supreme Court case involving the disbarment of former Confederate officials.

Background

In January 1865, the US Congress passed a law that effectively disbarred ...

'', 71 U.S. 333 (1866), the court struck down a federal law requiring attorneys practising in federal court to swear that they had not supported the rebellion. In '' Cummings v. Missouri'', 71 U.S. 277 (1867), the Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

Constitution required anyone seeking a professional's license from the state to swear they had not supported the rebellion. The Supreme Court overturned the law and the constitutional provision, arguing that the people already admitted to practice were subject to penalty without judicial trial. The lack of judicial trial was the critical affront to the Constitution, the Court said.

Two decades later, however, the Court upheld similar laws. In '' Hawker v. New York'', 170 U.S. 189 (1898), a state law barred convicted felons from practising medicine. In '' Dent v. West Virginia'', 129 U.S. 114 (1889), a West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

state law imposed a new requirement that practising physicians had to have graduated from a licensed medical school or they would be forced to surrender their license. The Court upheld both laws because, it said, the laws were narrowly tailored to focus on an individual's qualifications to practice medicine.Johnson, Theodore. ''The Second Amendment ControversyExplained.'' 2d ed. Indianapolis: iUniverse, 2002, p. 334. That was not true in ''Garland'' or ''Cummings''."Beyond Process: A Substantive Rationale for the Bill of Attainder Clause". ''Virginia Law Review''. 70:475 (April 1984), pp. 481-483.

The Court changed its "bill of attainder test" in 1946. In '' United States v. Lovett'', 328 U.S. 303 (1946), the Court confronted a federal law that named three people as subversive and excluded them from federal employment. Previously, the Court had held that lack of judicial trial and the narrow way in which the law rationally achieved its goals were the only tests of a bill of attainder. But the ''Lovett'' Court said that a bill of attainder 1) specifically identified the people to be punished; 2) imposed punishment; and 3) did so without benefit of judicial trial. As all three prongs of the bill of attainder test were met in ''Lovett'', the court held that a Congressional statute that bars particular individuals from government employment qualifies as punishment prohibited by the bill of attainder clause.

The Taft–Hartley Act

The Labor Management Relations Act, 1947, better known as the Taft–Hartley Act, is a Law of the United States, United States federal law that restricts the activities and power of trade union, labor unions. It was enacted by the 80th United S ...

(enacted in 1947) sought to ban political strikes by Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

-dominated labour unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

by requiring all elected labour leaders to take an oath that they were not and had never been members of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

, and that they did not advocate violent overthrow of the U.S. government. It also made it a crime for members of the Communist Party to serve on executive boards of labour unions. In '' American Communications Association v. Douds'', 339 U.S. 382 (1950), the Supreme Court had said that the requirement for the oath was not a bill of attainder because: 1) anyone could avoid punishment by disavowing the Communist Party, and 2) it focused on a future act (overthrow of the government) and not a past one.Welsh, Jane. "The Bill of Attainder Clause: An Unqualified Guarantee of Process". ''Brooklyn Law Review''. 50:77 (Fall 1983), p. 97. Reflecting current fears, the Court commented in ''Douds'' on approving the specific focus on Communists by noting what a threat communism was. The Court had added an "escape clause" test to determining whether a law was a bill of attainder.

In '' United States v. Brown'', 381 U.S. 437 (1965), the Court invalidated the section of the statute that criminalized a former communist serving on a union's executive board. Clearly, the Act had focused on past behaviour and had specified a specific class of people to be punished. Many legal scholars assumed that the ''Brown'' case effectively, if not explicitly, overruled ''Douds''. The Court did not apply the punishment prong of the ''Douds'' test, leaving legal scholars confused as to whether the Court still intended it to apply.

The Supreme Court emphasized the narrowness and rationality of bills of attainder in '' Nixon v. Administrator of General Services'', 433 U.S. 425 (1977). During the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the Presidency of Richard Nixon, administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Resignation of Richard Nixon, Nix ...

, in 1974 Congress passed the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act, which required the General Services Administration

The General Services Administration (GSA) is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States government established in 1949 to help manage and support the basic functioning of federal agencies. G ...

to confiscate former President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

's presidential papers to prevent their destruction, screen out those which contained national security and other issues which might prevent their publication, and release the remainder of the papers to the public as fast as possible. The Supreme Court upheld the law in ''Nixon'', arguing that specificity alone did not invalidate the act because the President constituted a "class of one".Stark, Jack. ''Prohibited Government Acts: A Reference Guide to the United States Constitution''. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2002, pp. 79–80. Thus, specificity was constitutional if it was rationally related to the class identified. The Court modified its punishment test, concluding that only those laws which historically offended the bill of attainder clause were invalid. The Court also found it significant that Nixon was compensated for the loss of his papers, which alleviated the punishment.Stark, ''Prohibited Government Acts: A Reference Guide to the United States Constitution'', 2002, p. 75. The Court modified the punishment prong by holding that punishment could survive scrutiny if rationally related to other, nonpunitive goals. Finally, the Court concluded that the legislation must not be intended to punish; legislation enacted for otherwise legitimate purposes could be saved so long as punishment was a side-effect rather than the main purpose of the law.

Lower court cases

A number of cases which raised the bill of attainder issue did not reach or have not reached the Supreme Court, but were considered by lower courts. In 1990, in the wake of theExxon Valdez oil spill

The ''Exxon Valdez'' oil spill was a major environmental disaster that occurred in Alaska's Prince William Sound on March 24, 1989. The spill occurred when ''Exxon Valdez'', an oil supertanker owned by Exxon Shipping Company, bound for Long Be ...

, Congress enacted the Oil Pollution Act to consolidate various oil spill and oil pollution statutes into a single unified law, and to provide for a statutory regime for handling oil spill cleanup. This law was challenged as a bill of attainder by the shipping division of ExxonMobil

Exxon Mobil Corporation ( ) is an American multinational List of oil exploration and production companies, oil and gas corporation headquartered in Spring, Texas, a suburb of Houston. Founded as the Successors of Standard Oil, largest direct s ...

.

In 2003, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (in case citations, D.C. Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. It has the smallest geographical jurisdiction of any of the U.S. courts of appeals, ...

struck down the Elizabeth Morgan Act as a bill of attainder.

After the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

passed a resolution in late 2009 barring the community organising group Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now

The Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN) is a left-wing community-based organization that advocates for low- and moderate-income families by working on neighborhood safety, voter registration, health care, affordable hou ...

(ACORN) from receiving federal funding, the group sued the U.S. government. Another, broader bill, the Defund ACORN Act, was enacted by Congress later that year. In March 2010, a federal district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district. Each district covers one U.S. state or a portion of a state. There is at least one feder ...

declared the funding ban an unconstitutional bill of attainder. On 13 August 2010, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (in case citations, 2d Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. Its territory covers the states of Connecticut, New York (state), New York, and Vermont, and it has ap ...

reversed and remanded on the grounds that only 10 percent of ACORN's funding was federal and that did not constitute "punishment".

Possible cases

There is argument over whether the Palm Sunday Compromise in the Terri Schiavo case was a bill of attainder. Some analysts considered a proposed Congressional bill to confiscate 90 percent of the bonus money paid to executives at federally rescued investment bankAmerican International Group

American International Group, Inc. (AIG) is an American multinational finance and insurance corporation with operations in more than 80 countries and jurisdictions. As of 2023, AIG employed 25,200 people. The company operates through three core ...

a bill of attainder, although disagreement exists on the issue. The bill was not passed by Congress.

In 2009, the city of Portland, Oregon

Portland ( ) is the List of cities in Oregon, most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon, located in the Pacific Northwest region. Situated close to northwest Oregon at the confluence of the Willamette River, Willamette and Columbia River, ...

's attempt to prosecute more severely those on a "secret list" of 350 individuals deemed by police to have committed "liveability crimes" in certain neighbourhoods was challenged as an unconstitutional bill of attainder.

In 2011, the House voted to defund Planned Parenthood

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. (PPFA), or simply Planned Parenthood, is an American nonprofit organization

. Democratic Representative Jerry Nadler called that vote a bill of attainder, saying it was unconstitutional as such because the legislation was targeting a specific group.

In January 2017, the House reinstated the Holman Rule, a procedural rule that enables lawmakers to reduce the pay of an individual federal worker down to $1. It was once again removed at the beginning of the 116th United States Congress

The 116th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate, Senate and the United States House of Representati ...

in January 2019, after Democrats had taken control of the chamber.

On November 5, 2019, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in ''Allen v. Cooper''. On March 23, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of North Carolina and struck down the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act

The Copyright Remedy Clarification Act (CRCA) is a United States copyright law that attempted to abrogate sovereign immunity of states for copyright infringement. The CRCA amended 17 USC 511(a):

Unconstitutionality

The CRCA has been struck ...

, which Congress passed in 1989 to attempt to curb such infringements of copyright by states, in '' Allen v. Cooper''.

After the ruling Nautilus Productions, the plaintiff in ''Allen v. Cooper'', filed a motion for reconsideration in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina. On August 18, 2021, Judge Terrence Boyle granted the motion for reconsideration which North Carolina promptly appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. The 4th Circuit denied the state's motion on October 14, 2022. Nautilus then filed their second amended complaint on February 8, 2023, alleging 5th and 14th Amendment violations of Nautilus' constitutional rights, additional copyright violations, and claiming that North Carolina's " Blackbeard's Law", N.C. Gen Stat §121-25(b), represents a Bill of Attainder. Eight years after the passage of "Blackbeard's Law", on June 30, 2023, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper signed a bill repealing the law.

President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

's executive orders targeting specific law firms, such as the executive order on March 6, 2025 entitled "Addressing Risks from Perkins Coie LLP", have been criticized as being essentially bills of attainder. Perkins Coie's suit against the Department of Justice argues that the order "shares all the essential features of a bill of attainder."

See also

* ''Ex post facto'' law, which retroactively changes the legal consequences of actions committed prior to its enactment * '' Lettres de cachet'', used by French kings to have people imprisoned without trial *Spot zoning

Spot or SPOT may refer to:

Places

* Spot, North Carolina, a community in the United States

* The Spot, New South Wales, a locality in Sydney, Australia

* South Pole Traverse, sometimes called the South Pole Overland Traverse

People

* Spot Col ...

, the arbitrary application or removal of zoning restrictions from a specific parcel of land

Notes

References

External links

British tradition

British Impeachment and Attainder

American tradition

* ttp://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/data/constitution/article01/47.html Extended annotation at FindLaw* Mention of Attainder in the Federalist Papers by

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

iFederalist 43

and by

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

iFederalist 84

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bill Of Attainder Common law English legal terminology Legal history