Beowulf - Sae Geata on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Beowulf'' (; ) is an Old English poem, an

The events in the poem take place over the 5th and 6th centuries, and feature predominantly non-English characters. Some suggest that ''Beowulf'' was first composed in the 7th century at Rendlesham in

The events in the poem take place over the 5th and 6th centuries, and feature predominantly non-English characters. Some suggest that ''Beowulf'' was first composed in the 7th century at Rendlesham in

"Beowulf's Great Hall"

''

Beowulf returns home and eventually becomes king of his own people. One day, fifty years after Beowulf's battle with Grendel's mother, a

Beowulf returns home and eventually becomes king of his own people. One day, fifty years after Beowulf's battle with Grendel's mother, a

''Beowulf'' survived to modern times in a single manuscript, written in ink on

''Beowulf'' survived to modern times in a single manuscript, written in ink on

The scholar Roy Liuzza notes that the practice of oral poetry is by its nature invisible to history as evidence is in writing. Comparison with other bodies of verse such as Homer's, coupled with ethnographic observation of early 20th century performers, has provided a vision of how an Anglo-Saxon singer-poet or

The scholar Roy Liuzza notes that the practice of oral poetry is by its nature invisible to history as evidence is in writing. Comparison with other bodies of verse such as Homer's, coupled with ethnographic observation of early 20th century performers, has provided a vision of how an Anglo-Saxon singer-poet or

The Dynastic Drama of Beowulf

' (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2020)

"A Fine Old Tale of Adventure: Beowulf Told to the Children of the English Race, 1898–1908." Children's Literature Association Quarterly 38.4 (2013): 399–419

* * * * * * * * , an

II. Sigfrid

* * * * * * * * *

Full digital facsimile of the manuscript on the British Library's Digitised Manuscripts website

edited by Kevin Kiernan, 4th online edition (University of Kentucky/The British Library, 2015)

''Beowulf'' manuscript in The British Library's Online Gallery, with short summary and podcast

()

Annotated List of ''Beowulf'' Translations: The List – Arizonal Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies

()

(digitised from Elliott van Kirk Dobbie (ed.), ''Beowulf and Judith'', Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records, 4 (New York, 1953)) * {{Authority control 9th-century books Germanic heroic legends Influences on J. R. R. Tolkien Poems adapted into films Works set in Denmark Works set in Sweden

epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film defined by the spectacular presentation of human drama on a grandiose scale

Epic(s) ...

in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend

Germanic heroic legend () is the heroic literary tradition of the Germanic peoples, Germanic-speaking peoples, most of which originates or is set in the Migration Period (4th-6th centuries AD). Stories from this time period, to which others were ...

consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature

Old English literature refers to poetry (alliterative verse) and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th- ...

. The date of composition is a matter of contention among scholars; the only certain dating is for the manuscript, which was produced between 975 and 1025 AD. Scholars call the anonymous author the "''Beowulf'' poet".

The story is set in pagan Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

in the 5th and 6th centuries. Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ) is an Old English poetry, Old English poem, an Epic poetry, epic in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translat ...

, a hero of the Geats

The Geats ( ; ; ; ), sometimes called ''Geats#Goths, Goths'', were a large North Germanic peoples, North Germanic tribe who inhabited ("land of the Geats") in modern southern Sweden from antiquity until the Late Middle Ages. They are one of ...

, comes to the aid of Hrothgar

Hrothgar ( ; ) was a semi-legendary Danish king living around the early sixth century AD.

Hrothgar appears in the Anglo-Saxon epics ''Beowulf'' and '' Widsith'', in Norse sagas and poems, and in medieval Danish chronicles. In both Anglo-Saxon ...

, the king of the Danes

Danes (, ), or Danish people, are an ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

History

Early history

Denmark ...

, whose mead hall

Among the early Germanic peoples, a mead hall or feasting hall was a large building with a single room intended to receive guests and serve as a center of community social life. From the fifth century to the Early Middle Ages such a building was t ...

Heorot

Heorot (Old English 'hart, stag') is a mead-hall and major point of focus in the Anglo-Saxon poem ''Beowulf''. The hall serves as a seat of rule for King Hrothgar, a legendary Danish king. After the monster Grendel slaughters the inhabitants of ...

has been under attack by the monster Grendel

Grendel is a character in the Anglo-Saxon epic poem ''Beowulf'' (700–1000 AD). He is one of the poem's three antagonists (along with his mother and the dragon), all aligned in opposition against the protagonist Beowulf. He is referred to as b ...

for twelve years. After Beowulf slays him, Grendel's mother

Grendel's mother () is one of three antagonists in the anonymous Old English poem ''Beowulf'' (c. 700–1000 AD), the other two being Grendel and the dragon. Each antagonist reflects different negative aspects of both the hero Beowulf and the h ...

takes revenge and is in turn defeated. Victorious, Beowulf goes home to Geatland and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years later, Beowulf defeats a dragon

A dragon is a Magic (supernatural), magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but European dragon, dragons in Western cultures since the Hi ...

, but is mortally wounded in the battle. After his death, his attendants cremate his body and erect a barrow on a headland

A headland, also known as a head, is a coastal landform, a point of land usually high and often with a sheer drop, that extends into a body of water. It is a type of promontory. A headland of considerable size often is called a cape.Whittow, Jo ...

in his memory.

Scholars have debated whether ''Beowulf'' was transmitted orally, affecting its interpretation: if it was composed early, in pagan times, then the paganism is central and the Christian elements were added later, whereas if it was composed later, in writing, by a Christian, then the pagan elements could be decorative archaising; some scholars also hold an intermediate position.

''Beowulf'' is written mostly in the Late West Saxon dialect

West Saxon is the term applied to the two different dialects Early West Saxon and Late West Saxon with West Saxon being one of the four distinct regional dialects of Old English. The three others were Kentish, Mercian and Northumbrian (the l ...

of Old English, but many other dialectal forms are present, suggesting that the poem may have had a long and complex transmission throughout the dialect areas of England.

There has long been research into similarities with other traditions and accounts, including the Icelandic '' Grettis saga'', the Norse story of Hrolf Kraki and his bear-shapeshifting

In mythology, folklore and speculative fiction, shapeshifting is the ability to physically transform oneself through unnatural means. The idea of shapeshifting is found in the oldest forms of totemism and shamanism, as well as the oldest existen ...

servant Bodvar Bjarki, the international folktale the Bear's Son Tale, and the Irish folktale of the Hand and the Child. Persistent attempts have been made to link ''Beowulf'' to tales from Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

'' or Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

''. More definite are biblical parallels, with clear allusions to the books of Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of humankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Bo ...

, Exodus, and Daniel.

The poem survives in a single copy in the manuscript known as the Nowell Codex

The Nowell Codex is the second of two manuscripts comprising the bound volume Cotton MS Vitellius A XV, one of the four major Old English literature#Extant manuscripts, Old English poetic manuscripts. It is most famous as the manuscript containi ...

. It has no title in the original manuscript, but has become known by the name of the story's protagonist. In 1731, the manuscript was damaged by a fire that swept through Ashburnham House in London, which was housing Sir Robert Cotton's collection of medieval manuscripts. It survived, but the margins were charred, and some readings were lost. The Nowell Codex is housed in the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom. Based in London, it is one of the largest libraries in the world, with an estimated collection of between 170 and 200 million items from multiple countries. As a legal deposit li ...

.

The poem was first transcribed in 1786; some verses were first translated into modern English in 1805, and nine complete translations were made in the 19th century, including those by John Mitchell Kemble and William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

.

After 1900, hundreds of translations, whether into prose, rhyming verse, or alliterative verse were made, some relatively faithful, some archaising, some attempting to domesticate the work. Among the best-known modern translations are those of Edwin Morgan, Burton Raffel, Michael J. Alexander, Roy Liuzza, and Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish Irish poetry, poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Among his best-known works is ''Death of a Naturalist'' (1966), his first m ...

. The difficulty of translating ''Beowulf'' has been explored by scholars including J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

(in his essay " On Translating ''Beowulf''), who worked on a verse and a prose translation of his own.

Historical background

East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

, as the Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two Anglo-Saxon cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near Woodbridge, Suffolk, England. Archaeology, Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when an undisturbed ship burial containing a wea ...

ship-burial shows close connections with Scandinavia, and the East Anglian royal dynasty, the Wuffingas, may have been descendants of the Geatish Wulfings. Others have associated this poem with the court of King Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

or with the court of King Cnut the Great

Cnut ( ; ; – 12 November 1035), also known as Canute and with the epithet the Great, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway from 1028 until his death in 1035. The three kingdoms united under Cnut's rul ...

.

The poem blends fictional, legendary, mythic and historical elements. Although Beowulf himself is not mentioned in any other Old English manuscript, many of the other figures named in ''Beowulf'' appear in Scandinavian sources. This concerns not only individuals (e.g., Healfdene, Hroðgar

Hrothgar ( ; ) was a semi-legendary Danish king living around the early sixth century AD.

Hrothgar appears in the Anglo-Saxon epics ''Beowulf'' and ''Widsith'', in Norse sagas and poems, and in medieval Danish chronicles. In both Anglo-Saxon an ...

, Halga

Halga, '' Helgi'', ''Helghe'' or ''Helgo'' was a legendary Danish king living in the early 6th century. His name would in his own language (Proto-Norse) have been *''Hailaga'' (dedicated to the gods).

Scholars generally agree that he appears in ...

, Hroðulf, Eadgils

Eadgils, ''Adils'', ''Aðils'', ''Adillus'', ''Aðísl at Uppsölum'', ''Athisl'', ''Athislus'' or ''Adhel'' was a semi-legendary king of Sweden, who is estimated to have lived during the 6th century.

''Beowulf'' and Old Norse sources present ...

and Ohthere

Ohthere, also Ohtere (Old Norse: ''Óttarr vendilkráka'', ''Vendelcrow''; in modern Swedish ''Ottar Vendelkråka''), was a semi-legendary king of Sweden of the house of Yngling, Scylfings, who is said to have lived during the Germanic Heroic Ag ...

), but also clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

(e.g., Scyldings, Scylfings and Wulfings) and certain events (e.g., the battle between Eadgils and Onela). The raid by King Hygelac

Hygelac (; ; ; or ''Hugilaicus''; died 516 or 521) was a king of the Geats according to the poem ''Beowulf''. It is Hygelac's presence in the poem which has allowed scholars to tentatively date the setting of the poem as well as to infer tha ...

into Frisia

Frisia () is a Cross-border region, cross-border Cultural area, cultural region in Northwestern Europe. Stretching along the Wadden Sea, it encompasses the north of the Netherlands and parts of northwestern Germany. Wider definitions of "Frisia" ...

is mentioned by Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (born ; 30 November – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours during the Merovingian period and is known as the "father of French history". He was a prelate in the Merovingian kingdom, encom ...

in his ''History of the Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

'' and can be dated to around 521.

The majority view appears to be that figures such as King Hrothgar and the Scyldings in ''Beowulf'' are based on historical people from 6th-century Scandinavia. Like the ''Finnesburg Fragment

The "Finnesburg Fragment" (also "Finnsburh Fragment") is a portion of an Old English heroic poem in alliterative verse about a fight in which Hnæf and his 60 retainers are besieged at "Finn's fort" and attempt to hold off their attackers. The su ...

'' and several shorter surviving poems, ''Beowulf'' has consequently been used as a source of information about Scandinavian figures such as Eadgils and Hygelac, and about continental Germanic figures such as Offa

Offa ( 29 July 796 AD) was King of Mercia, a kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death in 796. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa, Offa came to the throne after a period of civil war following the assassination of ...

, king of the continental Angles. However, one scholar, Roy Liuzza, feels that the poem is "frustratingly ambivalent", neither myth nor folktale, but is set "against a complex background of legendary history ... on a roughly recognizable map of Scandinavia", and comments that the Geats of the poem may correspond with the Gautar (of modern Götaland

Götaland (; also '' Gothia'', ''Gothland'', ''Gothenland'' or ''Gautland'') is one of three lands of Sweden and comprises ten provinces. Geographically it is located in the south of Sweden, bounded to the north by Svealand, with the deep wo ...

).

Nineteenth-century archaeological evidence may confirm elements of the ''Beowulf'' story. Eadgils was buried at Uppsala (Gamla Uppsala

Gamla Uppsala (, ''Old Uppsala'') is a parish and a village outside Uppsala in Sweden. It had 17,973 inhabitants in 2016.

As early as the 3rd century AD and the 4th century AD and onwards, it was an important religious, economic and political c ...

, Sweden) according to Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson ( ; ; 1179 – 22 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was elected twice as lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of th ...

. When the western mound (to the left in the photo) was excavated in 1874, the finds showed that a powerful man was buried in a large barrow, , on a bear skin with two dogs and rich grave offerings. The eastern mound was excavated in 1854, and contained the remains of a woman, or a woman and a young man. The middle barrow has not been excavated.

In Denmark, recent (1986–88, 2004–05)Niles, John D."Beowulf's Great Hall"

''

History Today

''History Today'' is a history magazine. Published monthly in London since January 1951, it presents authoritative history to as wide a public as possible. The magazine covers all periods and geographical regions and publishes articles of tradit ...

'', October 2006, 56 (10), pp. 40–44 archaeological excavations at Lejre

Lejre is a railway town in the northwestern part of the island of Zealand (Denmark), Zealand in eastern Denmark. It has a population of 3,165 (1 January 2024) inhabitants.

, where Scandinavian tradition located the seat of the Scyldings, Heorot

Heorot (Old English 'hart, stag') is a mead-hall and major point of focus in the Anglo-Saxon poem ''Beowulf''. The hall serves as a seat of rule for King Hrothgar, a legendary Danish king. After the monster Grendel slaughters the inhabitants of ...

, have revealed that a hall was built in the mid-6th century, matching the period described in ''Beowulf'', some centuries before the poem was composed. Three halls, each about long, were found during the excavation.

Summary

The protagonistBeowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ) is an Old English poetry, Old English poem, an Epic poetry, epic in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translat ...

, a hero of the Geats

The Geats ( ; ; ; ), sometimes called ''Geats#Goths, Goths'', were a large North Germanic peoples, North Germanic tribe who inhabited ("land of the Geats") in modern southern Sweden from antiquity until the Late Middle Ages. They are one of ...

, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, king of the Danes

Danes (, ), or Danish people, are an ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

History

Early history

Denmark ...

, whose great hall, Heorot

Heorot (Old English 'hart, stag') is a mead-hall and major point of focus in the Anglo-Saxon poem ''Beowulf''. The hall serves as a seat of rule for King Hrothgar, a legendary Danish king. After the monster Grendel slaughters the inhabitants of ...

, is plagued by the monster Grendel

Grendel is a character in the Anglo-Saxon epic poem ''Beowulf'' (700–1000 AD). He is one of the poem's three antagonists (along with his mother and the dragon), all aligned in opposition against the protagonist Beowulf. He is referred to as b ...

. Beowulf kills Grendel with his bare hands, then kills Grendel's mother

Grendel's mother () is one of three antagonists in the anonymous Old English poem ''Beowulf'' (c. 700–1000 AD), the other two being Grendel and the dragon. Each antagonist reflects different negative aspects of both the hero Beowulf and the h ...

with a giant's sword that he found in her lair.

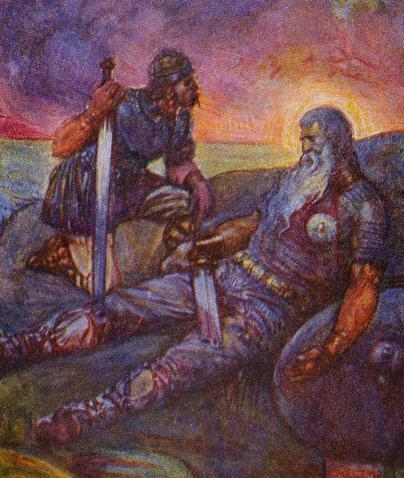

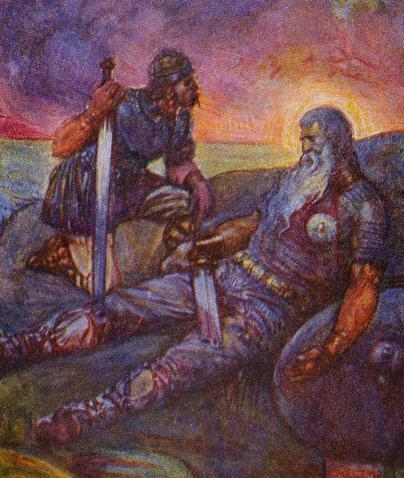

Later in his life, Beowulf becomes king of the Geats, and finds his realm terrorised by a dragon

A dragon is a Magic (supernatural), magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but European dragon, dragons in Western cultures since the Hi ...

, some of whose treasure had been stolen from his hoard in a burial mound. He attacks the dragon with the help of his ''thegn

In later Anglo-Saxon England, a thegn or thane (Latin minister) was an aristocrat who ranked at the third level in lay society, below the king and ealdormen. He had to be a substantial landowner. Thanage refers to the tenure by which lands were ...

s'' or servants, but they do not succeed. Beowulf decides to follow the dragon to its lair at Earnanæs, but only his young Swedish relative Wiglaf

Wiglaf ( Proto-Norse: *'' Wīga laibaz'', meaning "battle remainder"; ) is a character in the Anglo-Saxon epic poem ''Beowulf''. He is the son of Weohstan, a Swede of the Wægmunding clan who had entered the service of Beowulf, king of the G ...

, whose name means "remnant of valour", dares to join him. Beowulf finally slays the dragon, but is mortally wounded in the struggle. He is cremated and a burial mound by the sea is erected in his honour.

''Beowulf'' is considered an epic poem in that the main character is a hero who travels great distances to prove his strength at impossible odds against supernatural demons and beasts. The poem begins ''in medias res

A narrative work beginning ''in medias res'' (, "into the middle of things") opens in the chronological middle of the plot, rather than at the beginning (cf. '' ab ovo'', '' ab initio''). Often, exposition is initially bypassed, instead filled i ...

'' or simply, "in the middle of things", a characteristic of the epics of antiquity. Although the poem begins with Beowulf's arrival, Grendel's attacks have been ongoing. An elaborate history of characters and their lineages is spoken of, as well as their interactions with each other, debts owed and repaid, and deeds of valour. The warriors form a brotherhood linked by loyalty to their lord. The poem begins and ends with funerals: at the beginning of the poem for Scyld Scefing and at the end for Beowulf.

The poem is tightly structured. E. Carrigan shows the symmetry of its design in a model of its major components, with for instance the account of the killing of Grendel matching that of the killing of the dragon, the glory of the Danes matching the accounts of the Danish and Geatish courts. Other analyses are possible as well; Gale Owen-Crocker, for instance, sees the poem as structured by the four funerals it describes. For J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

, the primary division in the poem was between young and old Beowulf.

First battle: Grendel

''Beowulf'' begins with the story ofHrothgar

Hrothgar ( ; ) was a semi-legendary Danish king living around the early sixth century AD.

Hrothgar appears in the Anglo-Saxon epics ''Beowulf'' and '' Widsith'', in Norse sagas and poems, and in medieval Danish chronicles. In both Anglo-Saxon ...

, who constructed the great hall, Heorot, for himself and his warriors. In it, he, his wife Wealhtheow

Wealhtheow (also rendered Wealhþēow or Wealthow; ) is a queen of the Danes in the Old English poem ''Beowulf'', first introduced in line 612.

Character overview

Wealhtheow is of the Wulfing clan, Queen of the Danes (Germanic tribe), Danes. Sh ...

, and his warriors spend their time singing and celebrating. Grendel, a troll

A troll is a being in Nordic folklore, including Norse mythology. In Old Norse sources, beings described as trolls dwell in isolated areas of rocks, mountains, or caves, live together in small family units, and are rarely helpful to human bei ...

-like monster said to be descended from the biblical Cain

Cain is a biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He was a farmer who gave an offering of his crops to God. How ...

, is pained by the sounds of joy. Grendel attacks the hall and devours many of Hrothgar's warriors while they sleep. Hrothgar and his people, helpless against Grendel, abandon Heorot.

Beowulf, a young warrior from Geatland, hears of Hrothgar's troubles and with his king's permission leaves his homeland to assist Hrothgar.

Beowulf and his men spend the night in Heorot. Beowulf refuses to use any weapon because he holds himself to be Grendel's equal. When Grendel enters the hall and kills one of Beowulf's men, Beowulf, who has been feigning sleep, leaps up to clench Grendel's hand. Grendel and Beowulf battle each other violently. Beowulf's retainers draw their swords and rush to his aid, but their blades cannot pierce Grendel's skin. Finally, Beowulf tears Grendel's arm from his body at the shoulder. Fatally hurt, Grendel flees to his home in the marshes, where he dies. Beowulf displays "the whole of Grendel's shoulder and arm, his awesome grasp" for all to see at Heorot. This display fuelled Grendel's mother's anger in revenge.

Second battle: Grendel's mother

The next night, after celebrating Grendel's defeat, Hrothgar and his men sleep in Heorot. Grendel's mother, angry that her son has been killed, sets out to get revenge. "Beowulf was elsewhere. Earlier, after the award of treasure, The Geat had been given another lodging"; his assistance would be absent in this attack. Grendel's mother violently kills Æschere, who is Hrothgar's most loyal advisor, and escapes, later putting his head outside her lair. Hrothgar, Beowulf, and their men track Grendel's mother to her lair under a lake.Unferth

In the Old English epic poem ''Beowulf'', Unferth or Hunferth is a thegn (a retainer, servant) of the Danish lord Hrothgar. He appears five times in the poem — four times by the name 'Hunferð' (at lines 499, 530, 1165 and 1488) and once by ...

, a warrior who had earlier challenged him, presents Beowulf with his sword Hrunting. After stipulating a number of conditions to Hrothgar in case of his death (including the taking in of his kinsmen and the inheritance by Unferth of Beowulf's estate), Beowulf jumps into the lake and, while harassed by water monsters, gets to the bottom, where he finds a cavern. Grendel's mother pulls him in, and she and Beowulf engage in fierce combat.

At first, Grendel's mother prevails, and Hrunting proves incapable of hurting her; she throws Beowulf to the ground and, sitting astride him, tries to kill him with a short sword, but Beowulf is saved by his armour. Beowulf spots another sword, hanging on the wall and apparently made for giants, and cuts her head off with it. Travelling further into Grendel's mother's lair, Beowulf discovers Grendel's corpse and severs his head with the sword. Its blade melts because of the monster's "hot blood", leaving only the hilt. Beowulf swims back up to the edge of the lake where his men wait. Carrying the hilt of the sword and Grendel's head, he presents them to Hrothgar upon his return to Heorot. Hrothgar gives Beowulf many gifts, including the sword Nægling, his family's heirloom. The events prompt a long reflection by the king, sometimes referred to as "Hrothgar's sermon", in which he urges Beowulf to be wary of pride and to reward his thegns.

Final battle: The dragon

Beowulf returns home and eventually becomes king of his own people. One day, fifty years after Beowulf's battle with Grendel's mother, a

Beowulf returns home and eventually becomes king of his own people. One day, fifty years after Beowulf's battle with Grendel's mother, a slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

steals a golden cup from the lair of a dragon at Earnanæs. When the dragon sees that the cup has been stolen, it leaves its cave in a rage, burning everything in sight. Beowulf and his warriors come to fight the dragon, but Beowulf tells his men that he will fight the dragon alone and that they should wait on the barrow. Beowulf descends to do battle with the dragon, but finds himself outmatched. His men, upon seeing this and fearing for their lives, retreat into the woods. However, one of his men, Wiglaf, in great distress at Beowulf's plight, comes to his aid. The two slay the dragon, but Beowulf is mortally wounded. After Beowulf dies, Wiglaf remains by his side, grief-stricken. When the rest of the men finally return, Wiglaf bitterly admonishes them, blaming their cowardice for Beowulf's death. Beowulf is ritually burned on a great pyre in Geatland while his people wail and mourn him, fearing that without him, the Geats are defenceless against attacks from surrounding tribes. Afterwards, a barrow, visible from the sea, is built in his memory.

Digressions

The poem contains many apparent digressions from the main story. These were found troublesome by early ''Beowulf'' scholars such as Frederick Klaeber, who wrote that they "interrupt the story", W. W. Lawrence, who stated that they "clog the action and distract attention from it", and W. P. Ker who found some "irrelevant ... possibly ... interpolations". More recent scholars from Adrien Bonjour onwards note that the digressions can all be explained as introductions or comparisons with elements of the main story; for instance, Beowulf's swimming home across the sea from Frisia carrying thirty sets of armour emphasises his heroic strength. The digressions can be divided into four groups, namely the Scyld narrative at the start; many descriptions of the Geats, including the Swedish–Geatish wars, the "Lay of the Last Survivor" in the style of another Old English poem, " The Wanderer", and Beowulf's dealings with the Geats such as his verbal contest with Unferth and his swimming duel with Breca, and the tale of Sigemund and the dragon; history and legend, including the fight at Finnsburg and the tale of Freawaru and Ingeld; and biblical tales such as thecreation myth

A creation myth or cosmogonic myth is a type of cosmogony, a symbolic narrative of how the world began and how people first came to inhabit it., "Creation myths are symbolic stories describing how the universe and its inhabitants came to be. Cre ...

and Cain

Cain is a biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He was a farmer who gave an offering of his crops to God. How ...

as ancestor of all monsters. The digressions provide a powerful impression of historical depth, imitated by Tolkien in ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high fantasy novel written by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's book ''The Hobbit'' but eventually d ...

'', a work that embodies many other elements from the poem.

Authorship and date

The dating of ''Beowulf'' has attracted considerable scholarly attention; opinion differs as to whether it was first written in the 8th century, whether it was nearly contemporary with its 11th-century manuscript, and whether a proto-version (possibly a version of the " Bear's Son Tale") was orally transmitted before being transcribed in its present form.Albert Lord

Albert Bates Lord (15 September 1912 – 29 July 1991) was a professor of Slavic and comparative literature at Harvard, Harvard University who carried on Milman Parry's research on epic poetry after Parry's death.

Early life

Lord was born in Bos ...

felt strongly that the manuscript represents the transcription of a performance, though likely taken at more than one sitting. J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

believed that the poem retains too genuine a memory of Anglo-Saxon paganism

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, or Anglo-Saxon polytheism refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the Anglo-Saxons between t ...

to have been composed more than a few generations after the completion of the Christianisation of England around AD 700, and Tolkien's conviction that the poem dates to the 8th century has been defended by scholars including Tom Shippey

Thomas Alan Shippey (born 9 September 1943) is a British medievalist, a retired scholar of Middle and Old English literature as well as of modern fantasy and science fiction. He is considered one of the world's leading academic experts on the ...

, Leonard Neidorf

Leonard Neidorf (born ) is an American Philology, philologist who is Distinguished Professor of English language, English at Shenzhen University. Neidorf specializes in the study of Old English literature, Old English and Middle English literatur ...

, Rafael J. Pascual, and Robert D. Fulk. An analysis of several Old English poems by a team including Neidorf suggests that ''Beowulf'' is the work of a single author, though other scholars disagree.

The claim to an early 11th-century date depends in part on scholars who argue that, rather than the transcription of a tale from the oral tradition by an earlier literate monk, ''Beowulf'' reflects an original interpretation of an earlier version of the story by the manuscript's two scribes. On the other hand, some scholars argue that linguistic, palaeographical (handwriting), metrical (poetic structure), and onomastic

Onomastics (or onomatology in older texts) is the study of proper names, including their etymology, history, and use.

An ''alethonym'' ('true name') or an ''orthonym'' ('real name') is the proper name of the object in question, the object of onom ...

(naming) considerations align to support a date of composition in the first half of the 8th century; in particular, the poem's apparent observation of etymological vowel-length distinctions in unstressed syllables (described by Kaluza's law) has been thought to demonstrate a date of composition prior to the earlier ninth century. However, scholars disagree about whether the metrical phenomena described by Kaluza's law prove an early date of composition or are evidence of a longer prehistory of the ''Beowulf'' metre; B. R. Hutcheson, for instance, does not believe Kaluza's law can be used to date the poem, while claiming that "the weight of all the evidence Fulk presents in his book tells strongly in favour of an eighth-century date."

From an analysis of creative genealogy and ethnicity, Craig R. Davis suggests a composition date in the AD 890s, when King Alfred of England had secured the submission of Guthrum

Guthrum (, – c. 890) was King of East Anglia in the late 9th century. Originally a native of Denmark, he was one of the leaders of the "Great Summer Army" that arrived in Reading during April 871 to join forces with the Great Heathen Army, wh ...

, leader of a division of the Great Heathen Army

The Great Heathen Army, also known as the Viking Great Army,Hadley. "The Winter Camp of the Viking Great Army, AD 872–3, Torksey, Lincolnshire", ''Antiquaries Journal''. 96, pp. 23–67 was a coalition of Scandinavian warriors who invaded ...

of the Danes, and of Aethelred, ealdorman of Mercia. In this thesis, the trend of appropriating Gothic royal ancestry, established in Francia

The Kingdom of the Franks (), also known as the Frankish Kingdom, or just Francia, was the largest History of the Roman Empire, post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks, Frankish Merovingian dynasty, Merovingi ...

during Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

's reign, influenced the Anglian kingdoms of Britain to attribute to themselves a Geatish

The Geats ( ; ; ; ), sometimes called ''Geats#Goths, Goths'', were a large North Germanic peoples, North Germanic tribe who inhabited ("land of the Geats") in modern southern Sweden from antiquity until the Late Middle Ages. They are one of ...

descent. The composition of ''Beowulf'' was the fruit of the later adaptation of this trend in Alfred's policy of asserting authority over the '' Angelcynn'', in which Scyldic descent was attributed to the West-Saxon royal pedigree. This date of composition largely agrees with Lapidge's positing of a West-Saxon exemplar .

The location of the poem's composition is intensely disputed. In 1914, F.W. Moorman, the first professor of English Language at University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is a public research university in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It was established in 1874 as the Yorkshire College of Science. In 1884, it merged with the Leeds School of Medicine (established 1831) and was renamed Y ...

, claimed that ''Beowulf'' was composed in Yorkshire, but E. Talbot Donaldson claims that it was probably composed during the first half of the eighth century, and that the writer was a native of what was then called West Mercia, located in the Western Midlands of England. However, the late tenth-century manuscript, "which alone preserves the poem", originated in the kingdom of the West Saxons — as it is more commonly known.

Manuscript

''Beowulf'' survived to modern times in a single manuscript, written in ink on

''Beowulf'' survived to modern times in a single manuscript, written in ink on parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared Tanning (leather), untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves and goats. It has been used as a writing medium in West Asia and Europe for more than two millennia. By AD 400 ...

, later damaged by fire. The manuscript measures .

Provenance

The poem is known only from a single manuscript, estimated to date from around 975–1025, in which it appears with other works. The manuscript therefore dates either to the reign ofÆthelred the Unready

Æthelred II (,Different spellings of this king's name most commonly found in modern texts are "Ethelred" and "Æthelred" (or "Aethelred"), the latter being closer to the original Old English form . Compare the modern dialect word . ; ; 966 � ...

, characterised by strife with the Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard

Sweyn Forkbeard ( ; ; 17 April 963 – 3 February 1014) was King of Denmark from 986 until his death, King of England for five weeks from December 1013 until his death, and King of Norway from 999/1000 until 1014. He was the father of King Ha ...

, or to the beginning of the reign of Sweyn's son Cnut the Great

Cnut ( ; ; – 12 November 1035), also known as Canute and with the epithet the Great, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway from 1028 until his death in 1035. The three kingdoms united under Cnut's rul ...

from 1016. The ''Beowulf'' manuscript is known as the Nowell Codex, gaining its name from 16th-century scholar Laurence Nowell

Laurence (or Lawrence) Nowell (1530 – ) was an English antiquarian, cartographer and pioneering scholar of the Old English language and literature.

Life

Laurence Nowell was born in 1530 in Whalley, Lancashire, the second son of Alexander N ...

. The official designation is "British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom. Based in London, it is one of the largest libraries in the world, with an estimated collection of between 170 and 200 million items from multiple countries. As a legal deposit li ...

, Cotton Vitellius A.XV" because it was one of Sir Robert Bruce Cotton's holdings in the Cotton library

The Cotton or Cottonian library is a collection of manuscripts that came into the hands of the antiquarian and bibliophile Sir Robert Bruce Cotton MP (1571–1631). The collection of books and materials Sir Robert held was one of the three "foun ...

in the middle of the 17th century. Many private antiquarians and book collectors, such as Sir Robert Cotton, used their own library classification

A library classification is a system used within a library to organize materials, including books, sound and video recordings, electronic materials, etc., both on shelves and in catalogs and indexes. Each item is typically assigned a call number ...

systems. "Cotton Vitellius A.XV" translates as: the 15th book from the left on shelf A (the top shelf) of the bookcase with the bust of Roman Emperor Vitellius

Aulus Vitellius ( ; ; 24 September 1520 December 69) was Roman emperor for eight months, from 19 April to 20 December AD 69. Vitellius became emperor following the quick succession of the previous emperors Galba and Otho, in a year of civil wa ...

standing on top of it, in Cotton's collection. Kevin Kiernan argues that Nowell most likely acquired it through William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 15204 August 1598), was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Elizabeth I, Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (England), Secretary of State (1550–1553 and ...

, in 1563, when Nowell entered Cecil's household as a tutor

Tutoring is private academic help, usually provided by an expert teacher; someone with deep knowledge or defined expertise in a particular subject or set of subjects.

A tutor, formally also called an academic tutor, is a person who provides assis ...

to his ward, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604), was an English peerage, peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after ...

.

The earliest extant reference to the first foliation of the Nowell Codex was made sometime between 1628 and 1650 by Franciscus Junius (the younger). The ownership of the codex before Nowell remains a mystery.

The Reverend Thomas Smith (1638–1710) and Humfrey Wanley

Humfrey Wanley (21 March 1672 – 6 July 1726) was an English librarian, palaeographer and scholar of Old English, employed by manuscript collectors such as Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, Robert and Edward Harley, 2nd Earl ...

(1672–1726) both catalogued the Cotton library (in which the Nowell Codex was held). Smith's catalogue appeared in 1696, and Wanley's in 1705. The ''Beowulf'' manuscript itself is identified by name for the first time in an exchange of letters in 1700 between George Hickes, Wanley's assistant, and Wanley. In the letter to Wanley, Hickes responds to an apparent charge against Smith, made by Wanley, that Smith had failed to mention the ''Beowulf'' script when cataloguing Cotton MS. Vitellius A. XV. Hickes replies to Wanley "I can find nothing yet of Beowulph." Kiernan theorised that Smith failed to mention the ''Beowulf'' manuscript because of his reliance on previous catalogues or because either he had no idea how to describe it or because it was temporarily out of the codex.

The manuscript passed to Crown ownership in 1702, on the death of its then owner, Sir John Cotton, who had inherited it from his grandfather, Robert Cotton. It suffered damage in a fire at Ashburnham House in 1731, in which around a quarter of the manuscripts bequeathed by Cotton were destroyed. Since then, parts of the manuscript have crumbled along with many of the letters. Rebinding efforts, though saving the manuscript from much degeneration, have nonetheless covered up other letters of the poem, causing further loss. Kiernan, in preparing his electronic edition of the manuscript, used fibre-optic backlighting and ultraviolet lighting to reveal letters in the manuscript lost from binding, erasure, or ink blotting.

Writing

The ''Beowulf'' manuscript was transcribed from an original by two scribes, one of whom wrote the prose at the beginning of the manuscript and the first 1939 lines, before breaking off in mid-sentence. The first scribe made a point of carefully regularizing the spelling of the original document into the common West Saxon, removing any archaic or dialectical features. The second scribe, who wrote the remainder, with a difference in handwriting noticeable after line 1939, seems to have written more vigorously and with less interest. As a result, the second scribe's script retains more archaic dialectic features, which allow modern scholars to ascribe the poem a cultural context. While both scribes appear to have proofread their work, there are nevertheless many errors. The second scribe was ultimately the more conservative copyist as he did not modify the spelling of the text as he wrote, but copied what he saw in front of him. In the way that it is currently bound, the ''Beowulf'' manuscript is followed by the Old English poem ''Judith

The Book of Judith is a deuterocanonical book included in the Septuagint and the Catholic Church, Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Christian Old Testament of the Bible but Development of the Hebrew Bible canon, excluded from the ...

''. ''Judith'' was written by the same scribe that completed ''Beowulf'', as evidenced by similar writing style. Wormholes found in the last leaves of the ''Beowulf'' manuscript that are absent in the ''Judith'' manuscript suggest that at one point ''Beowulf'' ended the volume. The rubbed appearance of some leaves suggests that the manuscript stood on a shelf unbound, as was the case with other Old English manuscripts. Knowledge of books held in the library at Malmesbury Abbey

Malmesbury Abbey, at Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England, is a former Benedictine abbey dedicated to Saint Peter and Paul the Apostle, Saint Paul. It was one of the few English religious houses with a continuous history from the 7th century throug ...

and available as source works, as well as the identification of certain words particular to the local dialect found in the text, suggest that the transcription may have taken place there.

Performance

The scholar Roy Liuzza notes that the practice of oral poetry is by its nature invisible to history as evidence is in writing. Comparison with other bodies of verse such as Homer's, coupled with ethnographic observation of early 20th century performers, has provided a vision of how an Anglo-Saxon singer-poet or

The scholar Roy Liuzza notes that the practice of oral poetry is by its nature invisible to history as evidence is in writing. Comparison with other bodies of verse such as Homer's, coupled with ethnographic observation of early 20th century performers, has provided a vision of how an Anglo-Saxon singer-poet or scop

A ( or ) was a poet as represented in Old English poetry. The scop is the Old English counterpart of the Old Norse ', with the important difference that "skald" was applied to historical persons, and scop is used, for the most part, to designat ...

may have practised. The resulting model is that performance was based on traditional stories and a repertoire of word formulae that fitted the traditional metre. The scop moved through the scenes, such as putting on armour or crossing the sea, each one improvised at each telling with differing combinations of the stock phrases, while the basic story and style remained the same. Liuzza notes that ''Beowulf'' itself describes the technique of a court poet in assembling materials, in lines 867–874 in his translation, "full of grand stories, mindful of songs ... found other words truly bound together; ... to recite with skill the adventure of Beowulf, adeptly tell a tall tale, and (''wordum wrixlan'') weave his words." The poem further mentions (lines 1065–1068) that "the harp was touched, tales often told, when Hrothgar's scop was set to recite among the mead tables his hall-entertainment".

Debate over oral tradition

The question of whether ''Beowulf'' was passed down throughoral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

prior to its present manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has ...

form has been the subject of much debate, and involves more than simply the issue of its composition. Rather, given the implications of the theory of oral-formulaic composition and oral tradition, the question concerns how the poem is to be understood, and what sorts of interpretations are legitimate. In his landmark 1960 work, '' The Singer of Tales'', Albert Lord, citing the work of Francis Peabody Magoun and others, considered it proven that ''Beowulf'' was composed orally. Later scholars have not all been convinced; they agree that "themes" like "arming the hero" or the "hero on the beach" do exist across Germanic works. Some scholars conclude that Anglo-Saxon poetry is a mix of oral-formulaic and literate patterns. Larry Benson proposed that Germanic literature contains "kernels of tradition" which ''Beowulf'' expands upon.Foley, John M. ''Oral-Formulaic Theory and Research: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography''. New York: Garland, 1985. p. 126 Ann Watts argued against the imperfect application of one theory to two different traditions: traditional, Homeric, oral-formulaic poetry and Anglo-Saxon poetry. Thomas Gardner agreed with Watts, arguing that the ''Beowulf'' text is too varied to be completely constructed from set formulae and themes. John Miles Foley wrote that comparative work must observe the particularities of a given tradition; in his view, there was a fluid continuum from traditionality to textuality.

Editions, translations, and adaptations

Editions

Many editions of the Old English text of ''Beowulf'' have been published; this section lists the most influential. The Icelandic scholar Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin made the first transcriptions of the ''Beowulf''-manuscript in 1786, working as part of a Danish government historical research commission. He had a copy made by a professional copyist who knew no Old English (and was therefore in some ways more likely to make transcription errors, but in other ways more likely to copy exactly what he saw), and then made a copy himself. Since that time, the manuscript has crumbled further, making these transcripts prized witnesses to the text. While the recovery of at least 2000 letters can be attributed to them, their accuracy has been called into question, and the extent to which the manuscript was actually more readable in Thorkelin's time is uncertain. Thorkelin used these transcriptions as the basis for the first complete edition of ''Beowulf'', in Latin. In 1922, Frederick Klaeber, a German philologist who worked at the University of Minnesota, published his edition of the poem, '' Beowulf and The Fight at Finnsburg''; it became the "central source used by graduate students for the study of the poem and by scholars and teachers as the basis of their translations." The edition included an extensive glossary of Old English terms. His third edition was published in 1936, with the last version in his lifetime being a revised reprint in 1950. Klaeber's text was re-presented with new introductory material, notes, and glosses, in a fourth edition in 2008. Another widely used edition is Elliott Van Kirk Dobbie's, published in 1953 in the Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records series. The British Library, meanwhile, took a prominent role in supporting Kevin Kiernan's '' Electronic Beowulf''; the first edition appeared in 1999, and the fourth in 2014.Translations and adaptations

The tightly interwoven structure of Old English poetry makes translating ''Beowulf'' a severe technical challenge. Despite this, a great number of translations and adaptations are available, in poetry and prose. Andy Orchard, in ''A Critical Companion to Beowulf'', lists 33 "representative" translations in his bibliography, while theArizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies

The Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies (ACMRS) was established in 1981, by the Arizona Board of Regents as a state-wide, tri-university research unit that bridges the intellectual communities at Arizona State University, Northern ...

published Marijane Osborn's annotated list of over 300 translations and adaptations in 2003. ''Beowulf'' has been translated many times in verse and in prose, and adapted for stage and screen. By 2020, the Beowulf's Afterlives Bibliographic Database listed some 688 translations and other versions of the poem. ''Beowulf'' has been translated into at least 38 other languages.

In 1805, the historian Sharon Turner

Sharon Turner (24 September 1768 – 13 February 1847) was an English historian.

Life

Turner was born in Pentonville, the eldest son of William and Ann Turner of Yorkshire, who had settled in London upon marrying. He left school at fifteen to ...

translated selected verses into modern English

Modern English, sometimes called New English (NE) or present-day English (PDE) as opposed to Middle and Old English, is the form of the English language that has been spoken since the Great Vowel Shift in England

England is a Count ...

. This was followed in 1814 by John Josias Conybeare who published an edition "in English paraphrase and Latin verse translation." N. F. S. Grundtvig reviewed Thorkelin's edition in 1815 and created the first complete verse translation in Danish in 1820. In 1837, John Mitchell Kemble created an important literal translation in English. In 1895, William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

and A. J. Wyatt published the ninth English translation.

In 1909, Francis Barton Gummere's full translation in "English imitative metre" was published, and was used as the text of Gareth Hinds's 2007 graphic novel based on ''Beowulf''. In 1975, John Porter published the first complete verse translation of the poem entirely accompanied by facing-page Old English. Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish Irish poetry, poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Among his best-known works is ''Death of a Naturalist'' (1966), his first m ...

's 1999 translation of the poem ('' Beowulf: A New Verse Translation'', called "Heaneywulf" by the ''Beowulf'' translator Howell Chickering and many others) was both praised and criticised. The US publication was commissioned by W. W. Norton & Company, and was included in the ''Norton Anthology of English Literature''. Many retellings of ''Beowulf'' for children appeared in the 20th century.

In 2000 (2nd edition 2013), Liuzza published his own version of ''Beowulf'' in a parallel text with the Old English, with his analysis of the poem's historical, oral, religious and linguistic contexts. R. D. Fulk, of Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a state university system, system of Public university, public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana. The system has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration o ...

, published a facing-page edition and translation of the entire Nowell Codex

The Nowell Codex is the second of two manuscripts comprising the bound volume Cotton MS Vitellius A XV, one of the four major Old English literature#Extant manuscripts, Old English poetic manuscripts. It is most famous as the manuscript containi ...

manuscript in 2010. Hugh Magennis's 2011 ''Translating Beowulf: Modern Versions in English Verse'' discusses the challenges and history of translating the poem, as well as the question of how to approach its poetry, and discusses several post-1950 verse translations, paying special attention to those of Edwin Morgan, Burton Raffel, Michael J. Alexander, and Seamus Heaney. Translating ''Beowulf'' is one of the subjects of the 2012 publication ''Beowulf at Kalamazoo'', containing a section with 10 essays on translation, and a section with 22 reviews of Heaney's translation, some of which compare Heaney's work with Liuzza's. Tolkien's long-awaited prose translation (edited by his son Christopher

Christopher is the English language, English version of a Europe-wide name derived from the Greek language, Greek name Χριστόφορος (''Christophoros'' or ''Christoforos''). The constituent parts are Χριστός (''Christós''), "Jesus ...

) was published in 2014 as '' Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary''. The book includes Tolkien's own retelling of the story of Beowulf in his tale ''Sellic Spell'', but not his incomplete and unpublished verse translation. '' The Mere Wife'', by Maria Dahvana Headley, was published in 2018. It relocates the action to a wealthy community in 20th-century America and is told primarily from the point of view of Grendel's mother. In 2020, Headley published a translation in which the opening "Hwæt!" is rendered "Bro!"; this translation subsequently won the Hugo Award for Best Related Work

The Hugo Award for Best Related Work is one of the Hugo Awards given each year for primarily non-fiction works related to science fiction or fantasy, published or translated into English during the previous calendar year. The Hugo Awards have bee ...

.

Sources and analogues

Neither identified sources nor analogues for ''Beowulf'' can be definitively proven, but many conjectures have been made. These are important in helping historians understand the ''Beowulf'' manuscript, as possible source-texts or influences would suggest time-frames of composition, geographic boundaries within which it could be composed, or range (both spatial and temporal) of influence (i.e. when it was "popular" and where its "popularity" took it). The poem has been related to Scandinavian, Celtic, and international folkloric sources.Scandinavian parallels and sources

19th-century studies proposed that ''Beowulf'' was translated from a lost original Scandinavian work; surviving Scandinavian works have continued to be studied as possible sources. In 1886 Gregor Sarrazin suggested that anOld Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

original version of ''Beowulf'' must have existed, but in 1914 Carl Wilhelm von Sydow claimed that ''Beowulf'' is fundamentally Christian and was written at a time when any Norse tale would have most likely been pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

. Another proposal was a parallel with the '' Grettis Saga'', but in 1998, Magnús Fjalldal challenged that, stating that tangential similarities were being overemphasised as analogies. The story of Hrolf Kraki and his servant, the legendary bear-shapeshifter

In mythology, folklore and speculative fiction, shapeshifting is the ability to physically transform oneself through unnatural means. The idea of shapeshifting is found in the oldest forms of totemism and shamanism, as well as the oldest exist ...

Bodvar Bjarki, has also been suggested as a possible parallel; he survives in '' Hrólfs saga kraka'' and Saxo's ''Gesta Danorum

("Deeds of the Danes") is a patriotic work of Danish history, by the 12th-century author Saxo Grammaticus ("Saxo the Literate", literally "the Grammarian"). It is the most ambitious literary undertaking of medieval Denmark and is an essentia ...

'', while Hrolf Kraki, one of the Scyldings, appears as "Hrothulf" in ''Beowulf''. New Scandinavian analogues to ''Beowulf'' continue to be proposed regularly, with Hrólfs saga Gautrekssonar being the most recently adduced text.

International folktale sources

(1910) wrote a thesis that the first part of ''Beowulf'' (the Grendel Story) incorporated preexisting folktale material, and that the folktale in question was of the Bear's Son Tale (''Bärensohnmärchen'') type, which has surviving examples all over the world. This tale type was later catalogued as international folktale type 301 in the ATU Index, now formally entitled "The Three Stolen Princesses" type in Hans Uther's catalogue, although the "Bear's Son" is still used in Beowulf criticism, if not so much in folkloristic circles. However, although this folkloristic approach was seen as a step in the right direction, "The Bear's Son" tale has later been regarded by many as not a close enough parallel to be a viable choice. Later, Peter A. Jorgensen, looking for a more concise frame of reference, coined a "two-troll tradition" that covers both ''Beowulf'' and ''Grettis saga'': "a Norse 'ecotype

Ecotypes are organisms which belong to the same species but possess different phenotypical features as a result of environmental factors such as elevation, climate and predation. Ecotypes can be seen in wide geographical distributions and may event ...

' in which a hero enters a cave and kills two giants, usually of different sexes"; this has emerged as a more attractive folk tale parallel, according to a 1998 assessment by Andersson.

The epic's similarity to the Irish folktale "The Hand and the Child" was noted in 1899 by Albert S. Cook, and others even earlier. In 1914, the Swedish folklorist Carl Wilhelm von Sydow made a strong argument for parallelism with "The Hand and the Child", because the folktale type demonstrated a "monstrous arm" motif that corresponded with Beowulf's wrenching off Grendel's arm. No such correspondence could be perceived in the Bear's Son Tale or in the ''Grettis saga''.

James Carney and Martin Puhvel agree with this "Hand and the Child" contextualisation. Puhvel supported the "Hand and the Child" theory through such motifs as (in Andersson's words) "the more powerful giant mother, the mysterious light in the cave, the melting of the sword in blood, the phenomenon of battle rage, swimming prowess, combat with water monsters, underwater adventures, and the bear-hug style of wrestling."

In the Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () is a collection of the earliest Welsh prose stories, compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, created –1410, as well as a few earlier frag ...

, Teyrnon discovers the otherworldly boy child Pryderi, the principal character of the cycle, after cutting off the arm of a monstrous beast which is stealing foals from his stables. The medievalist R. Mark Scowcroft notes that the tearing off of the monster's arm without a weapon is found only in ''Beowulf'' and fifteen of the Irish variants of the tale; he identifies twelve parallels between the tale and ''Beowulf''.

Classical sources

Attempts to find classical orLate Latin

Late Latin is the scholarly name for the form of Literary Latin of late antiquity.Roberts (1996), p. 537. English dictionary definitions of Late Latin date this period from the 3rd to 6th centuries CE, and continuing into the 7th century in ...

influence or analogue in ''Beowulf'' are almost exclusively linked with Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

'' or Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

''. In 1926, Albert S. Cook suggested a Homeric connection due to equivalent formulas, metonymies, and analogous voyages. In 1930, James A. Work supported the Homeric influence, stating that the encounter between Beowulf and Unferth

In the Old English epic poem ''Beowulf'', Unferth or Hunferth is a thegn (a retainer, servant) of the Danish lord Hrothgar. He appears five times in the poem — four times by the name 'Hunferð' (at lines 499, 530, 1165 and 1488) and once by ...

was parallel to the encounter between Odysseus and Euryalus

Euryalus (; ) refers to the Euryalus fortress, the main citadel of Ancient Syracuse, and to several different characters from Greek mythology and classical literature:

Classical mythology

*Euryalus, named on sixth and fifth century BC pottery as ...

in Books 7–8 of the ''Odyssey,'' even to the point of both characters giving the hero the same gift of a sword upon being proven wrong in their initial assessment of the hero's prowess. This theory of Homer's influence on ''Beowulf'' remained very prevalent in the 1920s, but started to die out in the following decade when a handful of critics stated that the two works were merely "comparative literature", although Greek was known in late 7th century England: Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

states that Theodore of Tarsus, a Greek, was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

in 668, and he taught Greek. Several English scholars and churchmen are described by Bede as being fluent in Greek due to being taught by him; Bede claims to be fluent in Greek himself.

Frederick Klaeber, among others, argued for a connection between ''Beowulf'' and Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

near the start of the 20th century, claiming that the very act of writing a secular epic in a Germanic world represents Virgilian influence. Virgil was seen as the pinnacle of Latin literature, and Latin was the dominant literary language of England at the time, therefore making Virgilian influence highly likely. Similarly, in 1971, Alistair Campbell stated that the apologue technique used in ''Beowulf'' is so rare in epic poetry aside from Virgil that the poet who composed ''Beowulf'' could not have written the poem in such a manner without first coming across Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's writings.

Biblical influences

It cannot be denied that Biblical parallels occur in the text, whether seen as a pagan work with "Christian colouring" added by scribes or as a "Christian historical novel, with selected bits of paganism deliberately laid on as 'local colour'", as Margaret E. Goldsmith did in "The Christian Theme of ''Beowulf''". ''Beowulf'' echoes theBook of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

, the Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from ; ''Šəmōṯ'', 'Names'; ) is the second book of the Bible. It is the first part of the narrative of the Exodus, the origin myth of the Israelites, in which they leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through the strength of ...

, and the Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a 2nd-century BC biblical apocalypse with a 6th-century BC setting. It is ostensibly a narrative detailing the experiences and Prophecy, prophetic visions of Daniel, a Jewish Babylonian captivity, exile in Babylon ...

in its references to the Genesis creation narrative

The Genesis creation narrative is the creation myth of both Judaism and Christianity, told in the book of Genesis chapters 1 and 2. While the Jewish and Christian tradition is that the account is one comprehensive story, modern scholars of ...

, the story of Cain and Abel

In the biblical Book of Genesis, Cain and Abel are the first two sons of Adam and Eve. Cain, the firstborn, was a farmer, and his brother Abel was a shepherd. The brothers made sacrifices, each from his own fields, to God. God had regard for Ab ...

, Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

and the flood

A flood is an overflow of water (list of non-water floods, or rarely other fluids) that submerges land that is usually dry. In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Floods are of significant con ...

, the Devil

A devil is the mythical personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conce ...

, Hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location or state in the afterlife in which souls are subjected to punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history sometimes depict hells as eternal destinations, such as Christianity and I ...

, and the Last Judgment

The Last Judgment is a concept found across the Abrahamic religions and the '' Frashokereti'' of Zoroastrianism.

Christianity considers the Second Coming of Jesus Christ to entail the final judgment by God of all people who have ever lived, res ...

.

Dialect

''Beowulf'' predominantly uses theWest Saxon dialect

West Saxon is the term applied to the two different dialects Early West Saxon and Late West Saxon with West Saxon being one of the four distinct regional dialects of Old English. The three others were Kentish, Mercian and Northumbrian (the l ...

of Old English, like other Old English poems copied at the time. However, it also uses many other linguistic forms; this leads some scholars to believe that it has endured a long and complicated transmission through all the main dialect areas. It retains a complicated mix of Mercian, Northumbrian, Early West Saxon, Anglian, Kentish and Late West Saxon dialectical forms.

Form and metre

Old English poets typically usedalliterative verse

In meter (poetry), prosody, alliterative verse is a form of poetry, verse that uses alliteration as the principal device to indicate the underlying Metre (poetry), metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly s ...

, a form of verse in which the first half of the line (the a-verse) is linked to the second half (the b-verse) through similarity in initial sound. That the line consists of two halves is clearly indicated by the caesura

300px, An example of a caesura in modern western music notation

A caesura (, . caesuras or caesurae; Latin for "cutting"), also written cæsura and cesura, is a metrical pause or break in a verse where one phrase ends and another phrase beg ...

: (l. 4). This verse form maps stressed and unstressed syllables onto abstract entities known as metrical positions. There is no fixed number of beats per line: the first one cited has three () whereas the second has two ().

The poet had a choice of formulae to assist in fulfilling the alliteration scheme. These were memorised phrases that conveyed a general and commonly-occurring meaning that fitted neatly into a half-line of the chanted poem. Examples are line 8's ("waxed under welkin", i.e. "he grew up under the heavens"), line 11's ("pay tribute"), line 13's ("young in the yards", i.e. "young in the courts"), and line 14's ("as a comfort to his people").

Kenning

A kenning ( Icelandic: ) is a figure of speech, a figuratively-phrased compound term that is used in place of a simple single-word noun. For instance, the Old English kenning () means , as does ().

A kenning has two parts: a base-word (a ...

s are a significant technique in ''Beowulf''. They are evocative poetic descriptions of everyday things, often created to fill the alliterative requirements of the metre. For example, a poet might call the sea the "swan's riding"; a king might be called a "ring-giver". The poem contains many kennings, and the device is typical of much of classic poetry in Old English, which is heavily formulaic.

Interpretation and criticism

The history of modern ''Beowulf'' criticism is often said to begin with Tolkien, author and Merton Professor of Anglo-Saxon at theUniversity of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, who in his 1936 lecture to the British Academy

The British Academy for the Promotion of Historical, Philosophical and Philological Studies is the United Kingdom's national academy for the humanities and the social sciences.

It was established in 1902 and received its royal charter in the sa ...

criticised his contemporaries' excessive interest in its historical implications. He noted in '' Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics'' that as a result the poem's literary value had been largely overlooked, and argued that the poem "is in fact so interesting as poetry, in places poetry so powerful, that this quite overshadows the historical content..." Tolkien argued that the poem is not an epic; that, while no conventional term exactly fits, the nearest would be elegy

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

; and that its focus is the concluding dirge