Bauhaus University, Weimar Alumni on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the , was a German

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the , was a German  The school existed in three German cities—

The school existed in three German cities—

Ideal and utilitarian in the international style system: subject and object in the design concept of the 20th century

// International Journal of Cultural Research, 4 (25), 72–80.

German architectural modernism was known as Neues Bauen. Beginning in June 1907,

German architectural modernism was known as Neues Bauen. Beginning in June 1907,

''Вхутемас''

/ref> Both schools were state-sponsored initiatives to merge traditional craft with modern technology, with a basic course in aesthetic principles, courses in

The school was founded by Walter Gropius in

The school was founded by Walter Gropius in  Gropius was not necessarily against

Gropius was not necessarily against

The Bauhaus had a major impact on art and architecture trends in Western Europe, Canada, the United States and

The Bauhaus had a major impact on art and architecture trends in Western Europe, Canada, the United States and

File:Bauhaus-Dessau Festsaal.jpg, A stage in the Festsaal, Dessau

File:Bauhaus-Dessau Festsaal Bühnenbeleuchtung.jpg, Ceiling with light fixtures for stage in the Festsaal, Dessau

File:Bauhaus-Dessau Wohnheim Balkone.jpg, Dormitory balconies in the residence, Dessau

File:Bauhaus-Dessau Fensterfront.JPG, Mechanically opened windows, Dessau

File:Mensa Bauhaus Dessau.PNG, The Mensa (

Bauhaus Everywhere

— Google Arts & Culture * * * * * * *

Collection: Artists of the Bauhaus

from the University of Michigan Museum of Art {{Authority control Bauhaus, Modernist architecture in Germany, 1919 establishments in Germany 1933 disestablishments in Germany Architecture in Germany Architecture schools Art movements Design schools in Germany Expressionist architecture German architectural styles Graphic design Industrial design Modernist architecture School buildings completed in 1926, Bauhaus, Dessau Visual arts education Walter Gropius buildings, Bauhaus Weimar culture World Heritage Sites in Germany

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the , was a German

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the , was a German art school

An art school is an educational institution with a primary focus on practice and related theory in the visual arts and design. This includes fine art – especially illustration, painting, contemporary art, sculpture, and graphic design. T ...

operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts

A craft or trade is a pastime or an occupation that requires particular skills and knowledge of skilled work. In a historical sense, particularly the Middle Ages and earlier, the term is usually applied to people occupied in small scale pr ...

and the fine arts

In European academic traditions, fine art (or, fine arts) is made primarily for aesthetics or creativity, creative expression, distinguishing it from popular art, decorative art or applied art, which also either serve some practical function ...

.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2009), , pp. 64–66 The school became famous for its approach to design

A design is the concept or proposal for an object, process, or system. The word ''design'' refers to something that is or has been intentionally created by a thinking agent, and is sometimes used to refer to the inherent nature of something ...

, which attempted to unify individual artistic vision with the principles of mass production

Mass production, also known as mass production, series production, series manufacture, or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines ...

and emphasis on function

Function or functionality may refer to:

Computing

* Function key, a type of key on computer keyboards

* Function model, a structured representation of processes in a system

* Function object or functor or functionoid, a concept of object-orie ...

.

The Bauhaus was founded by architect Walter Gropius

Walter Adolph Georg Gropius (; 18 May 1883 – 5 July 1969) was a German-born American architect and founder of the Bauhaus, Bauhaus School, who is widely regarded as one of the pioneering masters of modernist architecture. He was a founder of ...

in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

. It was grounded in the idea of creating a ''Gesamtkunstwerk

A ''Gesamtkunstwerk'' (, 'total work of art', 'ideal work of art', 'universal artwork', 'synthesis of the arts', 'comprehensive artwork', or 'all-embracing art form') is a work of art that makes use of all or many art forms or strives to do so. ...

'' ("comprehensive artwork") in which all the arts would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style later became one of the most influential currents in modern design, modernist architecture

Modern architecture, also called modernist architecture, or the modern movement, is an architectural architectural movement, movement and architectural style, style that was prominent in the 20th century, between the earlier Art Deco Architectu ...

, and architectural education. The Bauhaus movement had a profound influence on subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design

Industrial design is a process of design applied to physical Product (business), products that are to be manufactured by mass production. It is the creative act of determining and defining a product's form and features, which takes place in adva ...

, and typography

Typography is the art and technique of Typesetting, arranging type to make written language legibility, legible, readability, readable and beauty, appealing when displayed. The arrangement of type involves selecting typefaces, Point (typogra ...

. Staff at the Bauhaus included prominent artists such as Paul Klee

Paul Klee (; 18 December 1879 – 29 June 1940) was a Swiss-born German artist. His highly individual style was influenced by movements in art that included expressionism, cubism, and surrealism. Klee was a natural draftsman who experimented wi ...

, Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky ( – 13 December 1944) was a Russian painter and art theorist. Kandinsky is generally credited as one of the pioneers of abstract art, abstraction in western art. Born in Moscow, he spent his childhood in ...

, Gunta Stölzl

Gunta Stölzl (5 March 1897 – 22 April 1983) was a German textile artist who played a fundamental role in the development of the Bauhaus school's weaving workshop, where she created enormous change as it transitioned from individual pictoria ...

, and László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy (; ; born László Weisz; July 20, 1895 – November 24, 1946) was a Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian painter and photographer as well as a professor in the Bauhaus school. He was highly influenced by Constructivism (art), con ...

at various points.

The school existed in three German cities—

The school existed in three German cities—Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

, from 1919 to 1925; Dessau

Dessau is a district of the independent city of Dessau-Roßlau in Saxony-Anhalt at the confluence of the rivers Mulde and Elbe, in the ''States of Germany, Bundesland'' (Federal State) of Saxony-Anhalt. Until 1 July 2007, it was an independent ...

, from 1925 to 1932; and Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, from 1932 to 1933—under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius

Walter Adolph Georg Gropius (; 18 May 1883 – 5 July 1969) was a German-born American architect and founder of the Bauhaus, Bauhaus School, who is widely regarded as one of the pioneering masters of modernist architecture. He was a founder of ...

from 1919 to 1928; Hannes Meyer

Hans Emil "Hannes" Meyer (18 November 1889 – 19 July 1954) was a Swiss architect and second director of the Bauhaus Dessau from 1928 to 1930.

Early life

Meyer was born in Basel, Switzerland, trained as a mason, and practiced as an architect ...

from 1928 to 1930; and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe ( ; ; born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies; March 27, 1886August 17, 1969) was a German-American architect, academic, and interior designer. He was commonly referred to as Mies, his surname. He is regarded as one of the pionee ...

from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

regime, having been painted as a centre of communist intellectualism. Internationally, former key figures of Bauhaus were successful in the United States and became known as the ''avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

'' for the International Style

The International Style is a major architectural style and movement that began in western Europe in the 1920s and dominated modern architecture until the 1970s. It is defined by strict adherence to Functionalism (architecture), functional and Fo ...

. The White city of Tel Aviv

The White City (, ''Ha-Ir ha-Levana''; ''Al-Madinah al-Bayḍā’'') is a collection of over 4,000 buildings in Tel Aviv from the 1930s built in a unique form of the International Style (architecture), International Style, commonly known as Bau ...

to which numerous Jewish Bauhaus architects emigrated, has the highest concentration of the Bauhaus' international architecture in the world.

The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For example, the pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school

A private school or independent school is a school not administered or funded by the government, unlike a State school, public school. Private schools are schools that are not dependent upon national or local government to finance their fina ...

and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer

Hans Emil "Hannes" Meyer (18 November 1889 – 19 July 1954) was a Swiss architect and second director of the Bauhaus Dessau from 1928 to 1930.

Early life

Meyer was born in Basel, Switzerland, trained as a mason, and practiced as an architect ...

to attend it.

Terms and concepts

Several specific features are identified in the Bauhaus forms and shapes: simple geometric shapes like rectangles and spheres, without elaborate decorations. Buildings, furniture, and fonts often feature rounded corners, sometimes rounded walls, or curved chrome pipes. Some buildings are characterized by rectangular features, for example protruding balconies with flat, chunky railings facing the street, and long banks of windows. Some outlines can be defined as a tool for creating an ideal form, which is the basis of the architectural concept. Vasileva E. (2016Ideal and utilitarian in the international style system: subject and object in the design concept of the 20th century

// International Journal of Cultural Research, 4 (25), 72–80.

Bauhaus and German modernism

After Germany's defeat inWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and the establishment of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

, a renewed liberal spirit allowed an upsurge of radical experimentation in all the arts, which had been suppressed by the old regime. Many Germans of left-wing views were influenced by the cultural experimentation that followed the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

, such as constructivism

Constructivism may refer to:

Art and architecture

* Constructivism (art), an early 20th-century artistic movement that extols art as a practice for social purposes

* Constructivist architecture, an architectural movement in the Soviet Union in t ...

. Such influences can be overstated: Gropius did not share these radical views, and said that Bauhaus was entirely apolitical. Just as important was the influence of the 19th-century English designer William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

(1834–1896), who had argued that art should meet the needs of society and that there should be no distinction between form and function. Thus, the Bauhaus style, also known as the International Style

The International Style is a major architectural style and movement that began in western Europe in the 1920s and dominated modern architecture until the 1970s. It is defined by strict adherence to Functionalism (architecture), functional and Fo ...

, was marked by the absence of ornamentation and by harmony between the function of an object or a building and its design.

However, the most important influence on Bauhaus was modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

, a cultural movement whose origins lay as early as the 1880s, and which had already made its presence felt in Germany before the World War, despite the prevailing conservatism. The design innovations commonly associated with Gropius and the Bauhaus—the radically simplified forms, the rationality and functionality, and the idea that mass production

Mass production, also known as mass production, series production, series manufacture, or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines ...

was reconcilable with the individual artistic spirit—were already partly developed in Germany before the Bauhaus was founded. The German national designers' organization Deutscher Werkbund

The Deutscher Werkbund (; ) is a German association of artists, architects, designers and industrialists established in 1907. The ''Werkbund'' became an important element in the development of modern architecture and industrial design, parti ...

was formed in 1907 by Hermann Muthesius

Adam Gottlieb Hermann Muthesius (20 April 1861 – 29 October 1927), known as Hermann Muthesius, was a German architect, author and diplomat, perhaps best known for promoting many of the ideas of the English Arts and Crafts movement within German ...

to harness the new potentials of mass production, with a mind towards preserving Germany's economic competitiveness with England. In its first seven years, the Werkbund came to be regarded as the authoritative body on questions of design in Germany, and was copied in other countries. Many fundamental questions of craftsmanship versus mass production, the relationship of usefulness and beauty, the practical purpose of formal beauty in a commonplace object, and whether or not a single proper form could exist, were argued out among its 1,870 members (by 1914).

German architectural modernism was known as Neues Bauen. Beginning in June 1907,

German architectural modernism was known as Neues Bauen. Beginning in June 1907, Peter Behrens

Peter Behrens (14 April 1868 – 27 February 1940) was a leading Germany, German architect, graphic and industrial designer, best known for his early pioneering AEG turbine factory, AEG Turbine Hall in Berlin in 1909. He had a long career, desi ...

' pioneering industrial design

Industrial design is a process of design applied to physical Product (business), products that are to be manufactured by mass production. It is the creative act of determining and defining a product's form and features, which takes place in adva ...

work for the German electrical company AEG The initials AEG are used for or may refer to:

Common meanings

* AEG (German company)

; AEG) was a German producer of electrical equipment. It was established in 1883 by Emil Rathenau as the ''Deutsche Edison-Gesellschaft für angewandte El ...

successfully integrated art and mass production on a large scale. He designed consumer products, standardized parts, created clean-lined designs for the company's graphics, developed a consistent corporate identity, built the modernist landmark AEG Turbine Factory, and made full use of newly developed materials such as poured concrete and exposed steel. Behrens was a founding member of the Werkbund, and both Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer worked for him in this period.

The Bauhaus was founded at a time when the German zeitgeist

In 18th- and 19th-century German philosophy, a ''Zeitgeist'' (; ; capitalized in German) is an invisible agent, force, or daemon dominating the characteristics of a given epoch in world history. The term is usually associated with Georg W. F ...

had turned from emotional Expressionism

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

to the matter-of-fact New Objectivity

The New Objectivity (in ) was a movement in German art that arose during the 1920s as a reaction against German Expressionism, expressionism. The term was coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the director of the ''Kunsthalle Mannheim, Kunsthalle' ...

. An entire group of working architects, including Erich Mendelsohn

Erich Mendelsohn (); 21 March 1887 – 15 September 1953) was a German-British architect, known for his expressionist architecture in the 1920s, as well as for developing a dynamic functionalism in his projects for department stores and cinem ...

, Bruno Taut

Bruno Julius Florian Taut (4 May 1880 – 24 December 1938) was a renowned German architect, urban planner and author. He was active during the Weimar period and is known for his theoretical works as well as his building designs.

Early l ...

and Hans Poelzig

Hans Poelzig (30 April 1869 – 14 June 1936) was a German architect, painter and set designer.

Life

Poelzig was born in Berlin in 1869 to Countess Clara Henrietta Maria Poelzig while she was married to George Acland Ames, an Englishman. Uncert ...

, turned away from fanciful experimentation and towards rational, functional, sometimes standardized building. Beyond the Bauhaus, many other significant German-speaking architects in the 1920s responded to the same aesthetic issues and material possibilities as the school. They also responded to the promise "to promote the object of assuring to every German a healthful habitation" written into the new Weimar Constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich (), usually known as the Weimar Constitution (), was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic era. The constitution created a federal semi-presidential republic with a parliament whose ...

(Article 155). Ernst May

Ernst Georg May (27 July 1886 – 11 September 1970) was a German architect and city planner.

May successfully applied urban design techniques to the city of Frankfurt am Main during the Weimar Republic period, and in 1930 less successful ...

, Bruno Taut and Martin Wagner, among others, built large housing blocks in Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

and Berlin. The acceptance of modernist design into everyday life was the subject of publicity campaigns, well-attended public exhibitions like the Weissenhof Estate

The Weissenhof Estate (German: ''Weißenhofsiedlung'') is a housing estate built for the 1927 ''Deutscher Werkbund'' exhibition in Stuttgart, Germany. It was an international showcase of modern architecture's aspiration to provide inexpensive, s ...

, films, and sometimes fierce public debate.

Bauhaus and Vkhutemas

The Vkhutemas, the Russian state art and technical school founded in 1920 inMoscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, has been compared to Bauhaus. Founded a year after the Bauhaus school, Vkhutemas has close parallels to the German Bauhaus in its intent, organization and scope. The two schools were the first to train artist-designers in a modern manner. ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia; Bolshaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya''''Вхутемас''

/ref> Both schools were state-sponsored initiatives to merge traditional craft with modern technology, with a basic course in aesthetic principles, courses in

color theory

Color theory, or more specifically traditional color theory, is a historical body of knowledge describing the behavior of colors, namely in color mixing, color contrast effects, color harmony, color schemes and color symbolism. Modern color th ...

, industrial design, and architecture. Vkhutemas was a larger school than the Bauhaus, but it was less publicised outside the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and consequently, is less familiar in the West

West is a cardinal direction or compass point.

West or The West may also refer to:

Geography and locations

Global context

* The Western world

* Western culture and Western civilization in general

* The Western Bloc, countries allied with NAT ...

.

With the internationalism of modern architecture and design, there were many exchanges between the Vkhutemas and the Bauhaus. The second Bauhaus director Hannes Meyer attempted to organise an exchange between the two schools, while Hinnerk Scheper of the Bauhaus collaborated with various Vkhutein members on the use of colour in architecture. In addition, El Lissitzky

El Lissitzky (, born Lazar Markovich Lissitzky , ; – 30 December 1941), was a Soviet Jewish artist, active as a painter, illustrator, designer, printmaker, photographer, and architect. He was an important figure of the Russian avant-garde, h ...

's book ''Russia: an Architecture for World Revolution'' published in German in 1930 featured several illustrations of Vkhutemas/Vkhutein projects there.

History of the Bauhaus

Weimar

The school was founded by Walter Gropius in

The school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

on 1 April 1919, as a merger of the Grand Ducal Saxon Academy of Fine Art and the Grand Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts for a newly affiliated architecture department. Its roots lay in the arts and crafts school founded by the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach () was a German state, created as a duchy in 1809 by the merger of the Ernestine duchies of Saxe-Weimar and Saxe-Eisenach, which had been in personal union since 1741. It was raised to a grand duchy in 1815 by resolution of ...

in 1906, and directed by Belgian Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau ( ; ; ), Jugendstil and Sezessionstil in German, is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. It was often inspired by natural forms such as the sinuous curves of plants and ...

architect Henry van de Velde

Henry Clemens van de Velde (; 3 April 1863 – 15 October 1957) was a Belgian painter, architect, interior designer, and art theorist. Together with Victor Horta and Paul Hankar, he is considered one of the founders of Art Nouveau in Belgium ...

. When van de Velde was forced to resign in 1915 because he was Belgian, he suggested Gropius, Hermann Obrist

Hermann Obrist (23 May 1862 at Kilchberg (near Zürich), Switzerland – 26 February 1927, Munich, Germany) was a Swiss sculptor of the Jugendstil and Art Nouveau movement. He studied Botany and History in his youth; the influence of those sub ...

, and August Endell

August Endell (April 12, 1871 – April 13, 1925) was a designer, writer, teacher, and German architect. He was one of the founders of the Jugendstil movement, the German counterpart of Art Nouveau. His first marriage was with Baroness Elsa, Els ...

as possible successors. In 1919, after delays caused by World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and a lengthy debate over who should head the institution and the socio-economic meanings of a reconciliation of the fine art

In European academic traditions, fine art (or, fine arts) is made primarily for aesthetics or creative expression, distinguishing it from popular art, decorative art or applied art, which also either serve some practical function (such as ...

s and the applied art

The applied arts are all the arts that apply design and decoration to everyday and essentially practical objects in order to make them aesthetically pleasing."Applied art" in ''The Oxford Dictionary of Art''. Online edition. Oxford Univ ...

s (an issue which remained a defining one throughout the school's existence), Gropius was made the director of a new institution integrating the two called the Bauhaus. In the pamphlet for an April 1919 exhibition entitled ''Exhibition of Unknown Architects'', Gropius, still very much under the influence of William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

and the British Arts and Crafts Movement

The Arts and Crafts movement was an international trend in the decorative and fine arts that developed earliest and most fully in the British Isles and subsequently spread across the British Empire and to the rest of Europe and America.

Initiat ...

, proclaimed his goal as being "to create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist." Gropius's neologism

In linguistics, a neologism (; also known as a coinage) is any newly formed word, term, or phrase that has achieved popular or institutional recognition and is becoming accepted into mainstream language. Most definitively, a word can be considered ...

''Bauhaus'' references both building and the Bauhütte, a premodern guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

of stonemasons. The early intention was for the Bauhaus to be a combined architecture school, crafts school, and academy of the arts. Swiss painter Johannes Itten

Johannes Itten (11 November 1888 – 25 March 1967) was a Swiss expressionist painter, designer, teacher, writer and theorist associated with the Bauhaus (''Staatliches Bauhaus'') school. Together with German-American painter Lyonel Feining ...

, German-American painter Lyonel Feininger

Lyonel Charles Adrian Feininger (; July 17, 1871January 13, 1956) was a German-American painter, and a leading exponent of Expressionism. He also worked as a caricaturist and comic strip artist. He was born and grew up in New York City. In 1887 h ...

, and German sculptor Gerhard Marcks

Gerhard Marcks (18 February 1889 – 13 November 1981) was a German artist, known primarily as a sculptor, but who is also known for his drawings, woodcuts, lithographs and ceramics.

Early life

Marcks was born in Berlin, where, at the age of 18, ...

, along with Gropius, comprised the faculty of the Bauhaus in 1919. By the following year their ranks had grown to include German painter, sculptor, and designer Oskar Schlemmer

Oskar Schlemmer (; 4 September 1888 – 13 April 1943) was a German painter, sculptor, designer and choreographer associated with the Bauhaus school.

In 1923, he was hired as Master of Form at the Bauhaus theatre workshop, after working at the ...

who headed the theatre workshop, and Swiss painter Paul Klee

Paul Klee (; 18 December 1879 – 29 June 1940) was a Swiss-born German artist. His highly individual style was influenced by movements in art that included expressionism, cubism, and surrealism. Klee was a natural draftsman who experimented wi ...

, joined in 1922 by Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky ( – 13 December 1944) was a Russian painter and art theorist. Kandinsky is generally credited as one of the pioneers of abstract art, abstraction in western art. Born in Moscow, he spent his childhood in ...

. The first major joint project completed by the Bauhaus was the Sommerfeld House

The Sommerfeld House, constructed between 1920 and 1921, was the first major joint project completed by the Bauhaus school. The house was built in Berlin as a villa for Adolf Sommerfeld who was a building contractor, lumbermill owner, and real-es ...

, which was built between 1920 and 1921. A tumultuous year at the Bauhaus, 1922 also saw the move of Dutch painter Theo van Doesburg

Theo van Doesburg (; born Christian Emil Marie Küpper; 30 August 1883 – 7 March 1931) was a Dutch painter, writer, poet and architect. He is best known as the founder and leader of De Stijl. He married three times.

Personal life

Theo van Do ...

to Weimar to promote ''De Stijl

De Stijl (, ; 'The Style') was a Dutch art movement founded in 1917 by a group of artists and architects based in Leiden (Theo van Doesburg, Jacobus Oud, J.J.P. Oud), Voorburg (Vilmos Huszár, Jan Wils) and Laren, North Holland, Laren (Piet Mo ...

'' ("The Style"), and a visit to the Bauhaus by Russian Constructivist artist and architect El Lissitzky

El Lissitzky (, born Lazar Markovich Lissitzky , ; – 30 December 1941), was a Soviet Jewish artist, active as a painter, illustrator, designer, printmaker, photographer, and architect. He was an important figure of the Russian avant-garde, h ...

.

From 1919 to 1922 the school was shaped by the pedagogical and aesthetic ideas of Johannes Itten

Johannes Itten (11 November 1888 – 25 March 1967) was a Swiss expressionist painter, designer, teacher, writer and theorist associated with the Bauhaus (''Staatliches Bauhaus'') school. Together with German-American painter Lyonel Feining ...

, who taught the ''Vorkurs'' or "preliminary course" that was the introduction to the ideas of the Bauhaus. Itten was heavily influenced in his teaching by the ideas of Franz Cižek

Franz Cižek (12 June 1865 – 17 December 1946) was an Austrian genre and portrait painter, who was a teacher and reformer of art education. He began the Child Art Movement in Vienna, opening the Juvenile Art Class in 1897.

Life

Franz Cižek wa ...

and Friedrich Wilhelm August Fröbel Friedrich may refer to:

Names

*Friedrich (given name), people with the given name ''Friedrich''

*Friedrich (surname), people with the surname ''Friedrich''

Other

*Friedrich (board game), a board game about Frederick the Great and the Seven Years' ...

. He was also influenced in respect to aesthetics by the work of the Der Blaue Reiter

''Der Blaue Reiter'' (''The Blue Rider'') was a group of artists and a designation by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc for their exhibition and publication activities, in which both artists acted as sole editors in the almanac of the same name ...

group in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

, as well as the work of Austrian Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka

Oskar Kokoschka (1 March 1886 – 22 February 1980) was an Austrian artist, poet, playwright and teacher, best known for his intense expressionistic portraits and landscapes, as well as his theories on vision that influenced the Viennese Expre ...

. The influence of German Expressionism

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

favoured by Itten was analogous in some ways to the fine arts side of the ongoing debate. This influence culminated with the addition of Der Blaue Reiter

''Der Blaue Reiter'' (''The Blue Rider'') was a group of artists and a designation by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc for their exhibition and publication activities, in which both artists acted as sole editors in the almanac of the same name ...

founding member Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky ( – 13 December 1944) was a Russian painter and art theorist. Kandinsky is generally credited as one of the pioneers of abstract art, abstraction in western art. Born in Moscow, he spent his childhood in ...

to the faculty and ended when Itten resigned in late 1923. Itten was replaced by the Hungarian designer László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy (; ; born László Weisz; July 20, 1895 – November 24, 1946) was a Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian painter and photographer as well as a professor in the Bauhaus school. He was highly influenced by Constructivism (art), con ...

, who rewrote the ''Vorkurs'' with a leaning towards the New Objectivity favoured by Gropius, which was analogous in some ways to the applied arts side of the debate. Although this shift was an important one, it did not represent a radical break from the past so much as a small step in a broader, more gradual socio-economic movement that had been going on at least since 1907, when van de Velde had argued for a craft basis for design while Hermann Muthesius

Adam Gottlieb Hermann Muthesius (20 April 1861 – 29 October 1927), known as Hermann Muthesius, was a German architect, author and diplomat, perhaps best known for promoting many of the ideas of the English Arts and Crafts movement within German ...

had begun implementing industrial prototypes.

Gropius was not necessarily against

Gropius was not necessarily against Expressionism

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

, and in the same 1919 pamphlet proclaiming this "new guild of craftsmen, without the class snobbery", described "painting and sculpture rising to heaven out of the hands of a million craftsmen, the crystal symbol of the new faith of the future." By 1923, however, Gropius was no longer evoking images of soaring Romanesque cathedrals and the craft-driven aesthetic of the "Völkisch movement

The ''Völkisch'' movement ( , , also called Völkism) was a Pan-Germanism, Pan-German Ethnic nationalism, ethno-nationalist movement active from the late 19th century through the dissolution of the Nazi Germany, Third Reich in 1945, with remn ...

", instead declaring "we want an architecture adapted to our world of machines, radios and fast cars." Gropius argued that a new period of history had begun with the end of the war. He wanted to create a new architectural style to reflect this new era. His style in architecture and consumer goods was to be functional, cheap and consistent with mass production. To these ends, Gropius wanted to reunite art and craft to arrive at high-end functional products with artistic merit. The Bauhaus issued a magazine called ''Bauhaus

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the , was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined Decorative arts, crafts and the fine arts.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., ...

'' and a series of books called "Bauhausbücher". Since the Weimar Republic lacked the number of raw materials available to the United States and Great Britain, it had to rely on the proficiency of a skilled labour force and an ability to export innovative and high-quality goods. Therefore, designers were needed and so was a new type of art education. The school's philosophy stated that the artist should be trained to work with the industry.

Weimar was in the German state of Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

, and the Bauhaus school received state support from the Social Democrat

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

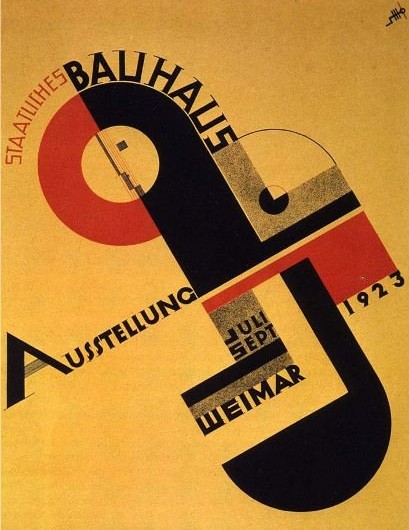

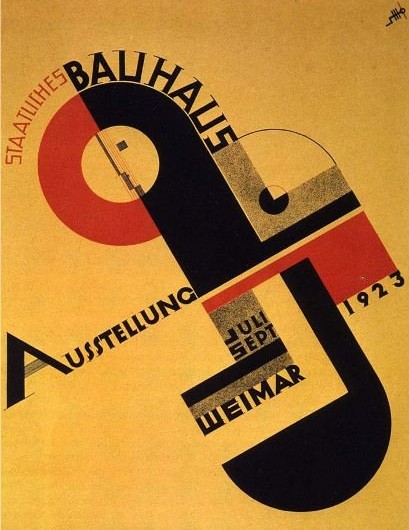

-controlled Thuringian state government. The school in Weimar experienced political pressure from conservative circles in Thuringian politics, increasingly so after 1923 as political tension rose. One condition placed on the Bauhaus in this new political environment was the exhibition of work undertaken at the school. This condition was met in 1923 with the Bauhaus' exhibition of the experimental Haus am Horn

The Haus am Horn is a domestic house in Weimar, Germany, designed by Georg Muche. It was built for the Bauhaus ''Werkschau'' (English: ''Work show'') exhibition which ran from July to September 1923. It was the first building based on Bauhaus de ...

. The Ministry of Education placed the staff on six-month contracts and cut the school's funding in half. The Bauhaus issued a press release on 26 December 1924, setting the closure of the school for the end of March 1925. At this point it had already been looking for alternative sources of funding. After the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, a school of industrial design with teachers and staff less antagonistic to the conservative political regime remained in Weimar. This school was eventually known as the Technical University of Architecture and Civil Engineering, and in 1996 changed its name to Bauhaus-University Weimar

The Bauhaus-Universität Weimar is a university located in Weimar, Germany, and specializes in the artistic and technical fields. Established in 1860 as the Great Ducal Saxon Art School, it gained collegiate status on 3 June 1910. In 1919 the s ...

.

Dessau

The Bauhaus moved toDessau

Dessau is a district of the independent city of Dessau-Roßlau in Saxony-Anhalt at the confluence of the rivers Mulde and Elbe, in the ''States of Germany, Bundesland'' (Federal State) of Saxony-Anhalt. Until 1 July 2007, it was an independent ...

in 1925 and new facilities there were inaugurated in late 1926. Gropius's design for the Dessau facilities was a return to the futuristic Gropius of 1914 that had more in common with the International style

The International Style is a major architectural style and movement that began in western Europe in the 1920s and dominated modern architecture until the 1970s. It is defined by strict adherence to Functionalism (architecture), functional and Fo ...

lines of the Fagus Factory

The Fagus Factory ( German: ''Fagus Fabrik'' or ''Fagus Werk''), a shoe last factory in Alfeld on the Leine, Lower Saxony, Germany, is an important example of early modern architecture. Commissioned by owner Carl Benscheidt who wanted a radical ...

than the stripped down Neo-classical of the Werkbund pavilion or the '' Völkisch'' Sommerfeld House. During the Dessau years, there was a remarkable change in direction for the school. According to Elaine Hoffman, Gropius had approached the Dutch architect Mart Stam

Mart Stam (August 5, 1899 – February 21, 1986) was a Dutch architect, urban planner, and furniture designer. Stam was extraordinarily well-connected, and his career intersects with important moments in the history of 20th-century Euro ...

to run the newly founded architecture program, and when Stam declined the position, Gropius turned to Stam's friend and colleague in the ABC group, Hannes Meyer.

Meyer became director when Gropius resigned in February 1928, and brought the Bauhaus its two most significant building commissions, both of which still exist: five apartment buildings in the city of Dessau, and the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (ADGB Trade Union School) in Bernau bei Berlin

Bernau bei Berlin (English ''Bernau by Berlin'', commonly named Bernau) is a town in the Barnim district in Brandenburg in eastern Germany, located about northeast of Berlin.

History

Archaeological excavations of Mesolithic-era sites indicate th ...

. Meyer favoured measurements and calculations in his presentations to clients, along with the use of off-the-shelf architectural components to reduce costs. This approach proved attractive to potential clients. The school turned its first profit under his leadership in 1929.

But Meyer also generated a great deal of conflict. As a radical functionalist, he had no patience with the aesthetic program and forced the resignations of Herbert Bayer

Herbert Bayer (April 5, 1900 – September 30, 1985) was an Austrian and American graphic designer, painter, photographer, sculptor, art director, environmental and interior designer, and architect. He was instrumental in the development of the ...

, Marcel Breuer

Marcel Lajos Breuer ( ; 21 May 1902 – 1 July 1981) was a Hungarian-American modernist architect and furniture designer. He moved to the United States in 1937 and became a naturalized American citizen in 1944.

At the Bauhaus he designed the Was ...

, and other long-time instructors. Even though Meyer shifted the orientation of the school further to the left than it had been under Gropius, he didn't want the school to become a tool of left-wing party politics. He prevented the formation of a student communist cell, and in the increasingly dangerous political atmosphere, this became a threat to the existence of the Dessau school. Dessau mayor Fritz Hesse fired him in the summer of 1930. The Dessau city council attempted to convince Gropius to return as head of the school, but Gropius instead suggested Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe ( ; ; born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies; March 27, 1886August 17, 1969) was a German-American architect, academic, and interior designer. He was commonly referred to as Mies, his surname. He is regarded as one of the pionee ...

. Mies was appointed in 1930 and immediately interviewed each student, dismissing those that he deemed uncommitted. He halted the school's manufacture of goods so that the school could focus on teaching, and appointed no new faculty other than his close confidant Lilly Reich

Lilly Reich (16 June 1885 – 14 December 1947) was a German designer specializing in textiles, furniture, interiors, and exhibition spaces. She was a close collaborator with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for more than ten years during the Weimar pe ...

. By 1931, the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

was becoming more influential in German politics. When it gained control of the Dessau city council, it moved to close the school.

Berlin

In late 1932, Mies rented a derelict factory in Berlin (Birkbusch Street 49) to use as the new Bauhaus with his own money. The students and faculty rehabilitated the building, painting the interior white. The school operated for ten months without further interference from the Nazi Party. In 1933, theGestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

closed down the Berlin school. Mies protested the decision, eventually speaking to the head of the Gestapo, who agreed to allow the school to re-open. However, shortly after receiving a letter permitting the opening of the Bauhaus, Mies and the other faculty agreed to voluntarily shut down the school.

Although neither the Nazi Party nor Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had a cohesive architectural policy before they came to power in 1933, Nazi writers like Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a German prominent politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and convicted war criminal who served as Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor ...

and Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

had already labelled the Bauhaus "un-German" and criticized its modernist styles, deliberately generating public controversy over issues like flat roofs. Increasingly through the early 1930s, they characterized the Bauhaus as a front for communists and social liberals. Indeed, when Meyer was fired in 1930, a number of communist students loyal to him moved to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

Even before the Nazis came to power, political pressure on Bauhaus had increased. The Nazi movement, from nearly the start, denounced the Bauhaus for its " degenerate art", and the Nazi regime was determined to crack down on what it saw as the foreign, probably Jewish, influences of "cosmopolitan modernism". Despite Gropius's protestations that as a war veteran and a patriot his work had no subversive political intent, the Berlin Bauhaus was pressured to close in April 1933.

Under the Nazi regime, about twenty Bauhauslers are known to have been killed in prison or concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

. Some emigrated, while others adapted and participated in propaganda exhibitions and design fairs, produced photographic and graphic works such as magazine covers, movie posters, and designed furniture, carpets, household objects and even busts of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. Of 119 teaching staff emigrated between 1933 and 1938. Of the students who were enrolled when Hitler came to power in 1933, approximately 900 are thought to have remained in Germany. Of those, 188 joined the National Socialist Party (170 men and 18 women), 14 were part of the brown shirts

The (; SA; or 'Storm Troopers') was the original paramilitary organisation under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party of Germany. It played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power, Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and early 1930s. I ...

, 12 joined the SS, and one was involved in the design of the crematoria at Auschwitz.

Mies emigrated to the United States to assume the directorship of the School of Architecture at the Armour Institute (now Illinois Institute of Technology

The Illinois Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Illinois Tech and IIT, is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the m ...

) in Chicago, and to seek building commissions. The simple engineering-oriented functionalism of stripped-down modernism, however, did lead to some Bauhaus influences living on in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. When Hitler's chief engineer, Fritz Todt

Fritz Todt (; 4 September 1891 – 8 February 1942) was a German construction engineer and senior figure of the Nazi Party. He was the founder of '' Organisation Todt'' (OT), a military-engineering organisation that supplied German industry w ...

, began opening the new autobahn

The (; German , ) is the federal controlled-access highway system in Germany. The official term is (abbreviated ''BAB''), which translates as 'federal motorway'. The literal meaning of the word is 'Federal Auto(mobile) Track'.

Much of t ...

s (highways) in 1935, many of the bridges and service stations were "bold examples of modernism", and among those submitting designs was Mies van der Rohe. Emigrants did succeed, however, in spreading the concepts of the Bauhaus to other countries, including the "New Bauhaus" of Chicago:

Architectural output

The paradox of the early Bauhaus was that, although its manifesto proclaimed that the aim of all creative activity was building, the school did not offer classes in architecture until 1927. During the years under Gropius (1919–1927), he and his partner Adolf Meyer observed no real distinction between the output of his architectural office and the school. The built output of Bauhaus architecture in these years is the output of Gropius: the Sommerfeld house in Berlin, the Otte house in Berlin, the Auerbach house inJena

Jena (; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Germany and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 in ...

, and the competition design for the Chicago Tribune Tower, which brought the school much attention. The definitive 1926 Bauhaus building in Dessau is also attributed to Gropius. Apart from contributions to the 1923 Haus am Horn

The Haus am Horn is a domestic house in Weimar, Germany, designed by Georg Muche. It was built for the Bauhaus ''Werkschau'' (English: ''Work show'') exhibition which ran from July to September 1923. It was the first building based on Bauhaus de ...

, student architectural work amounted to un-built projects, interior finishes, and craft work like cabinets, chairs and pottery.

In the next two years under Meyer, the architectural focus shifted away from aesthetics and towards functionality. There were major commissions: one from the city of Dessau for five tightly designed "Laubenganghäuser" (apartment buildings with balcony access), which are still in use today, and another for the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (ADGB Trade Union School) in Bernau bei Berlin

Bernau bei Berlin (English ''Bernau by Berlin'', commonly named Bernau) is a town in the Barnim district in Brandenburg in eastern Germany, located about northeast of Berlin.

History

Archaeological excavations of Mesolithic-era sites indicate th ...

. Meyer's approach was to research users' needs and scientifically develop the design solution. He intended to place emphasis on Gropius' objective analysis of the properties determining an object's use value, known as ''Wesensforschung''. Gropius believed that it was possible to design exemplary products of universal validity that should be standardized.

Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe ( ; ; born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies; March 27, 1886August 17, 1969) was a German-American architect, academic, and interior designer. He was commonly referred to as Mies, his surname. He is regarded as one of the pionee ...

repudiated Meyer's politics, his supporters, and his architectural approach. As opposed to Gropius's "study of essentials", and Meyer's research into user requirements, Mies advocated a "spatial implementation of intellectual decisions", which effectively meant an adoption of his own aesthetics. Neither Mies van der Rohe nor his Bauhaus students saw any projects built during the 1930s.

The Bauhaus movement was not focused on developing worker housing. Only two projects, the apartment building project in Dessau and the Törten row housing fall into the worker housing category. It was the Bauhaus contemporaries Bruno Taut

Bruno Julius Florian Taut (4 May 1880 – 24 December 1938) was a renowned German architect, urban planner and author. He was active during the Weimar period and is known for his theoretical works as well as his building designs.

Early l ...

, Hans Poelzig

Hans Poelzig (30 April 1869 – 14 June 1936) was a German architect, painter and set designer.

Life

Poelzig was born in Berlin in 1869 to Countess Clara Henrietta Maria Poelzig while she was married to George Acland Ames, an Englishman. Uncert ...

and particularly Ernst May

Ernst Georg May (27 July 1886 – 11 September 1970) was a German architect and city planner.

May successfully applied urban design techniques to the city of Frankfurt am Main during the Weimar Republic period, and in 1930 less successful ...

, as the city architects of Berlin, Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

and Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

respectively, who are rightfully credited with the thousands of socially progressive housing units built in Weimar Germany

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

. The housing Taut built in south-west Berlin during the 1920s, close to the U-Bahn stop Onkel Toms Hütte

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' () is a 1965 German film directed by Géza von Radványi. The film was entered into the 4th Moscow International Film Festival. It is based on the novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin''.

In the early spring of 1977, the film was reis ...

, is still occupied.

Impact

The Bauhaus had a major impact on art and architecture trends in Western Europe, Canada, the United States and

The Bauhaus had a major impact on art and architecture trends in Western Europe, Canada, the United States and Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

in the decades following its demise, as many of the artists involved fled, or were exiled by the Nazi regime. In 1996, four of the major sites associated with Bauhaus in Germany were inscribed on the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

World Heritage List

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural heritag ...

(with two more added in 2017).

In 1928, the Hungarian painter Alexander Bortnyik founded a school of design in Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

called Műhely, which means "the studio".Gaston Diehl, ''Vasarely'', New York: Crown, 1972, p. 12 Located on the seventh floor of a house on Nagymezo Street, it was meant to be the Hungarian equivalent to the Bauhaus. The literature sometimes refers to it—in an oversimplified manner—as "the Budapest Bauhaus". Bortnyik was a great admirer of László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy (; ; born László Weisz; July 20, 1895 – November 24, 1946) was a Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian painter and photographer as well as a professor in the Bauhaus school. He was highly influenced by Constructivism (art), con ...

and had met Walter Gropius in Weimar between 1923 and 1925. Moholy-Nagy himself taught at the Műhely. Victor Vasarely

Victor Vasarely (; born Győző Vásárhelyi, ; 9 April 1906 – 15 March 1997) was a Hungarian-French artist, who is widely accepted as a "grandfather" and leader of the Op art movement.

His work titled ''Zebra'', created in 1937, i ...

, a pioneer of op art

Op art, short for optical art, is a style of visual art that uses distorted or manipulated geometrical patterns, often to create optical illusions. It began in the early 20th century, and was especially popular from the 1960s on, the term "Op ...

, studied at this school before establishing in Paris in 1930.

Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer

Marcel Lajos Breuer ( ; 21 May 1902 – 1 July 1981) was a Hungarian-American modernist architect and furniture designer. He moved to the United States in 1937 and became a naturalized American citizen in 1944.

At the Bauhaus he designed the Was ...

, and Moholy-Nagy re-assembled in Britain during the mid-1930s and lived and worked in the Isokon

The London-based Isokon firm was founded in 1929 by the English entrepreneur Jack Pritchard and the Canadian architect Wells Coates to design and construct modernist houses and flats, and furniture and fittings for them. Originally called Wells ...

housing development in Lawn Road in London before the war caught up with them. Gropius and Breuer went on to teach at the Harvard Graduate School of Design

The Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) is the graduate school of design at Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It offers master's and doctoral programs in architecture, landscape architecture, urba ...

and worked together before their professional split. Their collaboration produced, among other projects, the Aluminum City Terrace in New Kensington, Pennsylvania and the Alan I W Frank House

The Alan I W Frank House is a private residence in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, designed by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and partner Marcel Breuer, two of the pioneering masters of 20th-century architecture and design. This spacious, multi-level re ...

in Pittsburgh. The Harvard School was enormously influential in America in the late 1920s and early 1930s, producing such students as Philip Johnson

Philip Cortelyou Johnson (July 8, 1906 – January 25, 2005) was an American architect who designed modern and postmodern architecture. Among his best-known designs are his modernist Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut; the postmodern 550 ...

, I. M. Pei

Ieoh Ming Pei

– website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners ( ; ; April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was ...

, – website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners ( ; ; April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was ...

Lawrence Halprin

Lawrence Halprin (July 1, 1916 – October 25, 2009) was an American landscape architect, designer, and teacher.

Beginning his career in the San Francisco Bay Area, California, in 1949, Halprin often collaborated with a local circle of modernist ...

and Paul Rudolph, among many others.

In the late 1930s, Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe ( ; ; born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies; March 27, 1886August 17, 1969) was a German-American architect, academic, and interior designer. He was commonly referred to as Mies, his surname. He is regarded as one of the pionee ...

re-settled in Chicago, enjoyed the sponsorship of the influential Philip Johnson

Philip Cortelyou Johnson (July 8, 1906 – January 25, 2005) was an American architect who designed modern and postmodern architecture. Among his best-known designs are his modernist Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut; the postmodern 550 ...

, and became one of the world's pre-eminent architects. Moholy-Nagy also went to Chicago and founded the New Bauhaus

The Institute of Design (ID) is a graduate school of the Illinois Institute of Technology, a private university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. The Institute of Design was founded in 1937 as "The New Bauhaus" by László Moholy-Nagy, a Ba ...

school under the sponsorship of industrialist and philanthropist Walter Paepcke

Walter Paepcke (June 29, 1896 – April 13, 1960) was an American businessman and philanthropist who was prominent in the mid-20th century. A longtime executive of the Chicago-based Container Corporation of America, Paepcke is best noted for his f ...

. This school became the Institute of Design, part of the Illinois Institute of Technology

The Illinois Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Illinois Tech and IIT, is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the m ...

. Printmaker and painter Werner Drewes

Werner Drewes (1899–1985) was a painter, printmaker, and art teacher. Considered to be one of the founding fathers of American abstraction, he was one of the first artists to introduce concepts of the Bauhaus school within the United States. ...

was also largely responsible for bringing the Bauhaus aesthetic to America and taught at both Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

and Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) is a private research university in St. Louis, Missouri, United States. Founded in 1853 by a group of civic leaders and named for George Washington, the university spans 355 acres across its Danforth ...

. Herbert Bayer

Herbert Bayer (April 5, 1900 – September 30, 1985) was an Austrian and American graphic designer, painter, photographer, sculptor, art director, environmental and interior designer, and architect. He was instrumental in the development of the ...

, sponsored by Paepcke, moved to Aspen

Aspen is a common name for certain tree species in the Populus sect. Populus, of the ''Populus'' (poplar) genus.

Species

These species are called aspens:

* ''Populus adenopoda'' – Chinese aspen (China, south of ''P. tremula'')

* ''Populus da ...

, Colorado in support of Paepcke's Aspen projects at the Aspen Institute

The Aspen Institute is an international nonprofit organization founded in 1949 as the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. It is headquartered in Washington, D.C., but also has a campus in Aspen, Colorado, its original home.

Its stated miss ...

. In 1953, Max Bill

Max Bill (22 December 1908 – 9 December 1994) was a Swiss architect, artist, painter, typeface designer, industrial designer and graphic designer.

Early life and education

Bill was born in Winterthur. After an apprenticeship as a silversmit ...

, together with Inge Aicher-Scholl

Inge is a given name in various Germanic language-speaking cultures. In Swedish and Norwegian, it is mostly used as a masculine, but less often also as a feminine name, sometimes as a short form of Ingeborg, while in Danish, Estonian, Frisian, Ge ...

and Otl Aicher

Otto "Otl" Aicher (; 13 May 1922 – 1 September 1991) was a German graphic designer and typographer. Aicher co-founded and taught at the influential Ulm School of Design. He is known for having led the design team of the 1972 Summer Olympics ...

, founded the Ulm School of Design

The Ulm School of Design () was a college of design based in Ulm, Germany. It was founded in 1953 by Inge Aicher-Scholl, Otl Aicher and Max Bill, the latter being first rector of the school and a former student at the Bauhaus. The HfG quickl ...

(German: Hochschule für Gestaltung – HfG Ulm) in Ulm, Germany, a design school in the tradition of the Bauhaus. The school is notable for its inclusion of semiotics

Semiotics ( ) is the systematic study of sign processes and the communication of meaning. In semiotics, a sign is defined as anything that communicates intentional and unintentional meaning or feelings to the sign's interpreter.

Semiosis is a ...

as a field of study. The school closed in 1968, but the "Ulm Model" concept continues to influence international design education. Another series of projects at the school were the Bauhaus typefaces, mostly realized in the decades afterward.

The influence of the Bauhaus on design education was significant. One of the main objectives of the Bauhaus was to unify art, craft, and technology, and this approach was incorporated into the curriculum of the Bauhaus. The structure of the Bauhaus ''Vorkurs'' (preliminary course) reflected a pragmatic approach to integrating theory and application. In their first year, students learnt the basic elements and principles of design and colour theory, and experimented with a range of materials and processes.Itten, J. (1963). ''Design and Form: The Basic Course at the Bauhaus and Later'' (Revised edition, 1975). New York: John Wiley & Sons. This approach to design education became a common feature of architectural and design school in many countries. For example, the Shillito Design School in Sydney stands as a unique link between Australia and the Bauhaus. The colour and design syllabus of the Shillito Design School was firmly underpinned by the theories and ideologies of the Bauhaus. Its first year foundational course mimicked the ''Vorkurs'' and focused on the elements and principles of design plus colour theory and application. The founder of the school, Phyllis Shillito, which opened in 1962 and closed in 1980, firmly believed that "A student who has mastered the basic principles of design, can design anything from a dress to a kitchen stove". In Britain, largely under the influence of painter and teacher William Johnstone, Basic Design, a Bauhaus-influenced art foundation course, was introduced at Camberwell School of Art and the Central School of Art and Design, whence it spread to all art schools in the country, becoming universal by the early 1960s.

One of the most important contributions of the Bauhaus is in the field of modern furniture

Modern furniture refers to furniture produced from the late 19th century through the present that is influenced by modernism. Post-World War II ideals of cutting excess, commodification, and practicality of materials in design heavily influence ...

design. The characteristic Cantilever chair and Wassily Chair

The Wassily Chair, also known as the Model B3 chair, was designed by Marcel Breuer in 1925–1926 while he was the head of the cabinet-making workshop at the Bauhaus, in Dessau, Germany.

Despite popular belief, the chair was not designed sp ...

designed by Marcel Breuer

Marcel Lajos Breuer ( ; 21 May 1902 – 1 July 1981) was a Hungarian-American modernist architect and furniture designer. He moved to the United States in 1937 and became a naturalized American citizen in 1944.

At the Bauhaus he designed the Was ...

are two examples. (Breuer eventually lost a legal battle in Germany with Dutch architect/designer Mart Stam

Mart Stam (August 5, 1899 – February 21, 1986) was a Dutch architect, urban planner, and furniture designer. Stam was extraordinarily well-connected, and his career intersects with important moments in the history of 20th-century Euro ...

over patent rights to the cantilever chair design. Although Stam had worked on the design of the Bauhaus's 1923 exhibit in Weimar, and guest-lectured at the Bauhaus later in the 1920s, he was not formally associated with the school, and he and Breuer had worked independently on the cantilever concept, leading to the patent dispute.) The most profitable product of the Bauhaus was its wallpaper.

The physical plant at Dessau survived World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and was operated as a design school with some architectural facilities by the German Democratic Republic

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

. This included live stage productions in the Bauhaus theater under the name of ''Bauhausbühne'' ("Bauhaus Stage"). After German reunification

German reunification () was the process of re-establishing Germany as a single sovereign state, which began on 9 November 1989 and culminated on 3 October 1990 with the dissolution of the East Germany, German Democratic Republic and the int ...

, a reorganized school continued in the same building, with no essential continuity with the Bauhaus under Gropius in the early 1920s. In 1979 Bauhaus-Dessau College started to organize postgraduate programs with participants from all over the world. This effort has been supported by the Bauhaus-Dessau Foundation which was founded in 1974 as a public institution.

Later evaluation of the Bauhaus design credo was critical of its flawed recognition of the human element, an acknowledgment of "the dated, unattractive aspects of the Bauhaus as a projection of utopia marked by mechanistic views of human nature…Home hygiene without home atmosphere."

Subsequent examples which have continued the philosophy of the Bauhaus include Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College was a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Black Mountain, North Carolina. It was founded in 1933 by John Andrew Rice, Theodore Dreier, and several others. The coll ...

, Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm and Domaine de Boisbuchet.

The White City

The White City (Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

: העיר הלבנה), refers to a collection of over 4,000 buildings built in the Bauhaus or International Style

The International Style is a major architectural style and movement that began in western Europe in the 1920s and dominated modern architecture until the 1970s. It is defined by strict adherence to Functionalism (architecture), functional and Fo ...

in Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( or , ; ), sometimes rendered as Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and usually referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the Gush Dan metropolitan area of Israel. Located on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline and with a popula ...

from the 1930s by German Jewish

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321 CE, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish commu ...

architects who emigrated to the British Mandate of Palestine after the rise of the Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

. Tel Aviv has the largest number of buildings in the Bauhaus/International Style of any city in the world. Preservation, documentation, and exhibitions have brought attention to Tel Aviv's collection of 1930s architecture. In 2003, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

) proclaimed Tel Aviv's ''White City'' a World Cultural Heritage site, as "an outstanding example of new town planning and architecture in the early 20th century." The citation recognized the unique adaptation of modern international architectural trends to the cultural, climatic, and local traditions of the city. Bauhaus Center Tel Aviv organizes regular architectural tours of the city, and the Bauhaus Foundation offers Bauhaus exhibits.

Sotsmisto in Zaporizhzhia

Sotsmisto, a residential neighborhood built in 1930s inZaporizhzhia

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. It is the Capital city, administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, was strongly influenced by Bauhaus. This neighborhood was among the first Soviet projects of a functional part of a modernized industrial city, and demonstrates the impact of Bauhaus on the development of early Soviet architecture as a whole.

Centenary

As the centenary of the founding of Bauhaus, several events, festivals, and exhibitions were held around the world in 2019. The international opening festival at theBerlin Academy of the Arts

The Prussian Academy of Arts () was a state arts academy first established in 1694 by prince-elector Frederick III of Brandenburg in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List ...