Balkhash, Lake on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lake Balkhash, also spelt Lake Balqash (, , ), is a lake in southeastern

Balkhash lies in the deepest part of the vast Balkhash-Alakol depression, which was formed by a sloping trough between mountains of the

Balkhash lies in the deepest part of the vast Balkhash-Alakol depression, which was formed by a sloping trough between mountains of the

The minimal water level of recent decades (340.65 meters AOD) was in 1987, when the filling of Kapshagay Reservoir was completed. The level recovered to 342.5 m by January 2005, attributed to exceptional precipitation in the late 1990s.

The lake used to have a rich fauna, but since 1970,

The lake used to have a rich fauna, but since 1970,

In 2005, 3.3 million people lived in the basin of the Lake Balkhash, including residents of

In 2005, 3.3 million people lived in the basin of the Lake Balkhash, including residents of

In 1970, the 364-

In 1970, the 364-

There is a regular ship navigation through the lake, the mouth of the Ili River, and the Kapchagay Reservoir. The main piers are Burylbaytal and Burlitobe. The ships are relatively light due to the limiting depth in some parts of the lake; they are used mainly for catching fish and transporting fish and construction materials. The total length of the

There is a regular ship navigation through the lake, the mouth of the Ili River, and the Kapchagay Reservoir. The main piers are Burylbaytal and Burlitobe. The ships are relatively light due to the limiting depth in some parts of the lake; they are used mainly for catching fish and transporting fish and construction materials. The total length of the

Academics and government advisors fear major loss of

Another factor affecting the ecology of the Ili-Balkhash basin is

Academics and government advisors fear major loss of

Another factor affecting the ecology of the Ili-Balkhash basin is

Kazakh 'national treasure' under threat

United Nations Environmental Programme details on Lake Balkhash

RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty {{DEFAULTSORT:Balkhash Siberian Tiger Re-population Project Endorheic lakes of Asia

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

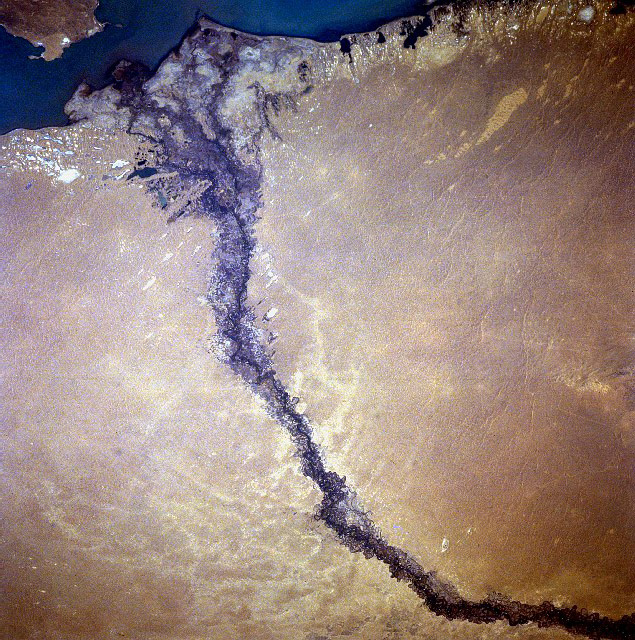

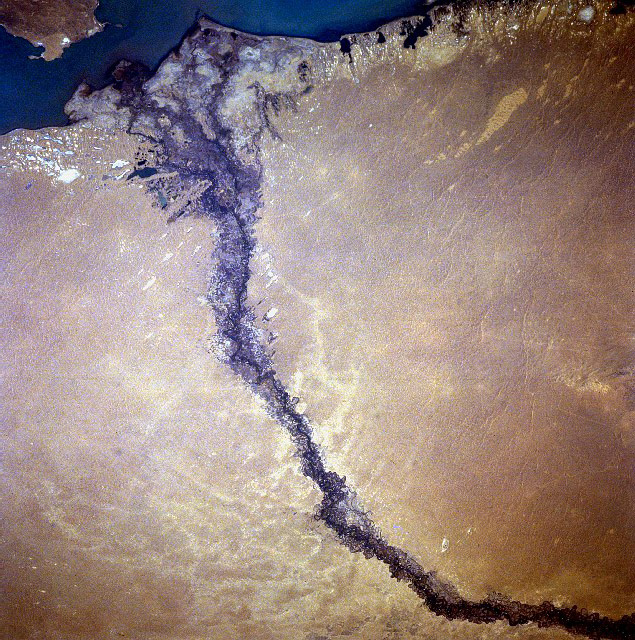

, one of the largest lakes in Asia and the 15th largest in the world. It is located in the eastern part of Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

and sits in the Balkhash-Alakol Basin

The Balkhash-Alakol Basin or Balkhash-Alakol Depression(; ), is a flat structural basin in southeastern Kazakhstan.endorheic

An endorheic basin ( ; also endoreic basin and endorreic basin) is a drainage basin that normally retains water and allows no outflow to other external bodies of water (e.g. rivers and oceans); instead, the water drainage flows into permanent ...

(closed) basin. The basin drains seven rivers, the primary of which is the Ili

Ili, ILI, Illi may refer to:

Abbreviations

* Indian Law Institute

* Influenza-like illness

* Intelligent Land Investments

* Intensive lifestyle intervention, a type of lifestyle medicine

* International Law Institute, a non-profit organization ...

, bringing most of the riparian

A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. In some regions, the terms riparian woodland, riparian forest, riparian buffer zone, riparian corridor, and riparian strip are used to characterize a ripar ...

inflow; others, such as the Karatal, bring surface and subsurface flow

Subsurface flow, in hydrology, is the flow of water beneath Earth's surface as part of the water cycle.

In the water cycle, when precipitation falls on the Earth's land, some of the water flows on the surface forming streams and rivers. The rema ...

. The Ili is fed by precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls from clouds due to gravitational pull. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, rain and snow mixed ("sleet" in Commonwe ...

, largely vernal snowmelt, from the mountains of China's Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

region.

The lake currently covers about . However, like the Aral Sea

The Aral Sea () was an endorheic lake lying between Kazakhstan to its north and Uzbekistan to its south, which began shrinking in the 1960s and had largely dried up into desert by the 2010s. It was in the Aktobe and Kyzylorda regions of Kazakhst ...

, it is shrinking due to diversion and extraction of water from its feeders. The lake has a narrow, quite central, strait

A strait is a water body connecting two seas or water basins. The surface water is, for the most part, at the same elevation on both sides and flows through the strait in both directions, even though the topography generally constricts the ...

. The lake's western part is fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salt (chemistry), salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include ...

and its eastern half is saline

Saline may refer to:

Salt-related

* Saline (medicine), a liquid with salt content to match the human body

* Saline water, non-medicinal salt water

* Saline, a historical term (especially American) for a salt works or saltern

Places United States ...

. The eastern part is on average 1.7 times deeper than the west. The largest shore city is named Balkhash and has about 66,000 inhabitants. Main local economic activities include mining, ore processing and fishing.

There is concern about the lake's shallowing due to desertification

Desertification is a type of gradual land degradation of Soil fertility, fertile land into arid desert due to a combination of natural processes and human activities.

The immediate cause of desertification is the loss of most vegetation. This i ...

of microclimate

A microclimate (or micro-climate) is a local set of atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric conditions that differ from those in the surrounding areas, often slightly but sometimes substantially. The term may refer to areas as small as a few square m ...

s and water extraction for multiplied industrial output. Moreover, the impacts of climate change may also negatively affect the lake and its ecosystems.

History and naming

The present name of the lake originates from the word "balkas" ofTatar

Tatar may refer to:

Peoples

* Tatars, an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar"

* Volga Tatars, a people from the Volga-Ural region of western Russia

* Crimean Tatars, a people from the Crimea peninsula by the B ...

, Kazakh and Southern Altai language

Southern Altai (also known as Oirot, Oyrot, Altai and Altai proper) is a Turkic language spoken in the Altai Republic, a federal subject of Russia located in Southern Siberia on the border with Mongolia and China. The language has some mutual i ...

s which means " tussocks in a swamp".

From as early as 103 BC up until the 8th century, the Balkhash polity surrounding the lake, whose Chinese name was ''Yibohai'' 夷播海, was known to the Chinese

Chinese may refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people identified with China, through nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**Han Chinese, East Asian ethnic group native to China.

**'' Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic ...

as 布谷/布庫/布蘇 "Bugu/Buku/Busu." From the 8th century on, the land to the south of the lake, between it and the Tian Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

mountains, was known in Turkic as ''Jetisu'' "Seven Rivers" ('' Semirechye'' in Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

). It was a land where the nomadic Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic of Turkey

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic lang ...

and Mongols

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China ( Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family o ...

of the steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

mingled cultures with the settled peoples of Central Asia.

Beginning in 1759, the lake marked the northwesternmost limit of Qing

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

suzerainty as recognized by the Qing and Russians. In 1864, the lake and its neighboring area were ceded to the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

under the Treaty of Tarbagatai

The Treaty of Tarbagatai () or Treaty of Chuguchak () of was a border protocol between Qing dynasty, Qing China and the Russian Empire that defined most of the western extent of their border in central Asia, between Outer Mongolia and the Khanate ...

. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in 1991, the lake became part of Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

.

The origin of the lake

Balkhash lies in the deepest part of the vast Balkhash-Alakol depression, which was formed by a sloping trough between mountains of the

Balkhash lies in the deepest part of the vast Balkhash-Alakol depression, which was formed by a sloping trough between mountains of the Alpine orogeny

The Alpine orogeny, sometimes referred to as the Alpide orogeny, is an orogenic phase in the Late Mesozoic and the current Cenozoic which has formed the mountain ranges of the Alpide belt.

Cause

The Alpine orogeny was caused by the African c ...

and the older Kazakhstan Block during the Neogene

The Neogene ( ,) is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period million years ago. It is the second period of th ...

and Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), as well as the current and most recent of the twelve periods of the ...

. Rapid erosion of the Tian Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

has meant the depression subsequently filled with sand river sediments in what is geologically a very short timespan. The basin is a part of Dzungarian Alatau

The Dzungarian Alatau (, ''Züüngaryn Alatau''; ; , ''Jetısu Alatauy''; , ''Dzhungarskiy Alatau'') is a mountain range that lies on the boundary of the Dzungaria region of China and the Jetisu, Zhetysu region of Kazakhstan. It has a length of ...

, which also contains lakes Sasykkol, Alakol and Aibi. These lakes are remnants of an ancient sea which once covered the entire Balkhash-Alakol depression, but was not connected with the Aral–Caspian Depression.

Description

All the rivers of this region that carry their waters from high mountains flow into Lake Balkhash, however, none of them flows out. The major ones are:Ili

Ili, ILI, Illi may refer to:

Abbreviations

* Indian Law Institute

* Influenza-like illness

* Intelligent Land Investments

* Intensive lifestyle intervention, a type of lifestyle medicine

* International Law Institute, a non-profit organization ...

, Aksu and Karatal. River Tokrau flows from the north, but its waters get lost in the sands before reaching the lakeshore. The lake is divided into two parts by the Saryesik peninsula (which means "Yellow Door" in the Kazakh language). These two parts are connected by the Uzynaral strait

A strait is a water body connecting two seas or water basins. The surface water is, for the most part, at the same elevation on both sides and flows through the strait in both directions, even though the topography generally constricts the ...

. In ancient times Balkhash was much larger and many lakes in the area were part of it, such as Zhalanashkol

Lake Zhalanashkol (, literally "Bare Lake", or "Exposed Lake"; ) is a freshwater lake in the eastern part of Kazakhstan, on the border of Almaty Province (Alakol District) and East Kazakhstan Province (Urzhar District). It is the smallest out of ...

, Itishpes, Alakol and Sasykkol. Even farther back it was a sea, stretching all the way to the Dzungarian Alatau

The Dzungarian Alatau (, ''Züüngaryn Alatau''; ; , ''Jetısu Alatauy''; , ''Dzhungarskiy Alatau'') is a mountain range that lies on the boundary of the Dzungaria region of China and the Jetisu, Zhetysu region of Kazakhstan. It has a length of ...

.

As recently as 1910 the lake was considerably larger with an estimated area of 23,464 km2. By 1946 this had shrunk by a nearly third, to 15,730km2.

Relief

The lake has a surface area of about 16,400km2 (2000), making it the largest lake wholly in Kazakhstan. Its surface is about 340 m above sea level. It has a gentle curve (sickle

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting or reaping grain crops, or cutting Succulent plant, succulent forage chiefly for feedi ...

) shape yet with jagged shorelines. Its length is about 600 km and the width varies from 9–19km in the eastern part to 74km in the western part. Saryesik Peninsula, near the middle of the lake, hydrographically divides it into two very different lakes. The western lake covers 58% of the surface area but only 46% of the volume. It is thus relatively shallow, quiet and filled with freshwater. The eastern lake is much deeper and saltier. These parts are connected by the Uzynaral Strait ( – "long island") – 3.5km wide and about 6 metres deep.

The lake includes several small basins. In the western part, are two depressions 7–11 meters deep. One extends from the western coast (near Tasaral Island) to Cape Korzhyntubek, whereas the second lies south from the Gulf Bertys, which is the deepest part of the "half". The average depth of the eastern basin is 16 m and the maximum depth is 26 m.

The average depth of the lake is 5.8 metres, and the total volume of water is about 112km3.

The western and northern shores of the lake are high (20–30 m) and rocky; they are composed of such Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

rocks as porphyry

Porphyry (; , ''Porphyrios'' "purple-clad") may refer to:

Geology

* Porphyry (geology), an igneous rock with large crystals in a fine-grained matrix, often purple, and prestigious Roman sculpture material

* Shoksha porphyry, quartzite of purple c ...

, tuff

Tuff is a type of rock made of volcanic ash ejected from a vent during a volcanic eruption. Following ejection and deposition, the ash is lithified into a solid rock. Rock that contains greater than 75% ash is considered tuff, while rock co ...

, granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

, schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock generally derived from fine-grained sedimentary rock, like shale. It shows pronounced ''schistosity'' (named for the rock). This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a l ...

and limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

and keep traces of ancient terraces. The southern shores near the Gulf Karashagan and Ili River are low (1–2 m) and sandy. They are often flooded and therefore contain numerous water pools. Occasional hills are present with the height of 5–10 m. The coastline

A coast (coastline, shoreline, seashore) is the land next to the sea or the line that forms the boundary between the land and the ocean or a lake. Coasts are influenced by the topography of the surrounding landscape and by aquatic erosion, su ...

is very curvy and dissected by numerous bays and coves. The large bays of the western part are: Saryshagan, Kashkanteniz, Karakamys, Shempek (the southern pole of the lake), and Balakashkan Ahmetsu, and those in the eastern part are: Guzkol, Balyktykol, Kukuna, Karashigan. The eastern part also includes peninsulas Baygabyl, Balay, Shaukar, Kentubek and Korzhintobe.

The lake contains 43 islands with a total area of 66km2; however, new islands are being formed due to the lowering of water level, and the area of the existing ones is increasing. The islands of the western part include Tasaral and Basaral (the largest), as well as Ortaaral, Ayakaral and Olzhabekaral. The eastern islands include Ozynaral, Ultarakty, Korzhyn and Algazy.

Feeding the lake and the water level

The Balkhash-Alakol Basin covers 512,000 km2, and its average surface water runoff is 27.76km3/year, of which 11.5km3 comes from China. Thedrainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land in which all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, ...

of the lake is about 413,000km2; with 15% in the north-west of Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

in China and a negligible part from mountains along the Kyrgyz-Kazakh border. Lake Balkhash thus takes 86% of water inflow from Balkhash-Alakol basin.

The Ili accounts for 73–80% of the inflow: 12.3km3/year or 23km3 per year. The river rises in a very long, narrow, high sided valley lined by the Tian Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

mountains and is mainly fed by glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

. These have a sporadic degree of relief precipitation

Orography is the study of the topographic relief of mountains, and can more broadly include hills, and any part of a region's elevated terrain. Orography (also known as ''oreography'', ''orology,'' or ''oreology'') falls within the broader dis ...

, their predominant type. Inflow is often greatest and most regulated during the glacial melting season: June to July. The river forms a quite narrow delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet

* D (NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta"), the fourth letter in the Latin alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* Delta Air Lines, a major US carrier ...

of 8,000km2 that serves as an multi-year accumulator type of regulator.

The eastern part of the lake is fed by the rivers Karatal, Aksu and Lepsy, as well as by groundwater

Groundwater is the water present beneath Earth's surface in rock and Pore space in soil, soil pore spaces and in the fractures of stratum, rock formations. About 30 percent of all readily available fresh water in the world is groundwater. A unit ...

. The Karatal rises on the slopes of Dzungarian Alatau

The Dzungarian Alatau (, ''Züüngaryn Alatau''; ; , ''Jetısu Alatauy''; , ''Dzhungarskiy Alatau'') is a mountain range that lies on the boundary of the Dzungaria region of China and the Jetisu, Zhetysu region of Kazakhstan. It has a length of ...

and is the second-largest inflow. The Ayaguz, which fed the east half until 1950, seldom reaches Lake Balkhash.

The western half's inflow averages 1.15km3 greater, per year.

The area and volume vary due to long-term and short-term fluctuations in water level. Long-term fluctuations had an amplitude of 12–14 metres. Since the year 0 CE they saw minimal water between the 5th and 10th centuries; and maximal between the 13th and 18th centuries. In the early 20th century and between 1958 and 1969, the lake swelled to cover about 18,000km2. In drought

A drought is a period of drier-than-normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, ...

s such as the late 1900s, 1930s and 1940s, the lake shrank to about 16,000 km2 having a drop in level of about 3 metres. In 1946, the lake's surface area was 15,730km2 (volume 82.7km3). Since the late 1900s, the lake has been shrinking due to the diversion of the rivers supplying it. For example, Kapshagay Hydroelectric Power Plant

The Kapshagay Hydroelectric Power Plant (, ''Qapshaǵaı sý elektr stantsııasy''; , earlier Капчагайская ГЭС) is a hydroelectricity power plant on the Ili River in Almaty Province of Kazakhstan. Constructed between 1965 and 19 ...

was built on the Ili in 1970. Filling the associated Kapshagay Reservoir

Kapchagay (, ) or Qapshaghay Reservoir (, ), also known as the Qapshaghay Bogeni Reservoir and sometimes referred to as Lake Kapchagay, is a major reservoir in Almaty Region in southeastern Kazakhstan, approximately north of Almaty. The long lak ...

disbalanced the lake, worsening water quality, especially in the eastern part. Between 1970 and 1987, the water level fell by 2.2 metres, the volume reduced by 30 km3 and salinity in the west half was increasing. Projects were proposed to slow down the changes, such as by splitting the lake in two with a dam, called off as the Soviet Union saw recession, democratisation and secession.

Water composition

Balkhash is a semi-saline lake. Chemical composition strongly depends on the hydrographic features of the reservoir. Water in the west half is nearly fresh, with the content oftotal dissolved solids

Total dissolved solids (TDS) is a measure of the dissolved solids, dissolved combined content of all inorganic compound, inorganic and organic compound, organic substances present in a liquid in molecule, molecular, ionized, or micro-granular (so ...

about 0.74 g/L, and cloudy (visibility: 1 metre); it is used for drinking and industry. The east half has less silt in suspension (visibility: 5.5 metres) but resembles oceanic sea water in salinity, with concentration of 3.5–6 g/L. The average salinity of the lake is 2.94 g/L. Long-term (1931–70) average precipitation of salts in the lake is 7.53 million tonnes and the reserves of dissolved salts are about 312 million tonnes. The water in the western part has a yellow-gray tint, and in the eastern part the color varies from bluish to emerald-blue.

Climate

The climate of the lake area iscontinental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' (album), an album by Saint Etienne

* Continen ...

. The average mean temperature is about 24 °C with highs in July and the average mean temperature is −14°C in January. Average precipitation is 131mm per year and the relative humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, dew, or fog t ...

is about 60%. Wind, dry climate and high summer temperatures result in high evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the Interface (chemistry), surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. A high concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evapora ...

rate – 950 mm in cold and up to 1200mm in dry years. Wind has average speed of 4.5–4.8m/s and blows mainly southward in the western part and to the south-west in the eastern part. The wind induces waves up to 2–3.5 m in height and steady clockwise currents in the western part.

There are 110–130 sunny days per year with the average irradiance

In radiometry, irradiance is the radiant flux ''received'' by a ''surface'' per unit area. The SI unit of irradiance is the watt per square metre (symbol W⋅m−2 or W/m2). The CGS unit erg per square centimetre per second (erg⋅cm−2⋅s−1) ...

of 15.9 MJ/m2 per day. Water temperature at the surface of the lake varies from 0 °C in December to 28 °C in July. The average annual temperature is 10°C in the western and 9°C in the eastern parts of the lake. The lake freezes every year between November and early April, and the melting is delayed by some 10–15 days in the eastern part.

Flora and fauna

The shores of the lake contain individualwillow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, of the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 350 species (plus numerous hybrids) of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions.

Most species are known ...

trees and riparian forest

A riparian forest or riparian woodland is a forested or wooded area of land adjacent to a body of water such as a river, stream, pond, lake, marshland, estuary, canal, Sink (geography), sink, or reservoir. Due to the broad nature of the definitio ...

s, mostly composed of various species of ''Populus

''Populus'' is a genus of 25–30 species of deciduous flowering plants in the family Salicaceae, native to most of the Northern Hemisphere. English names variously applied to different species include poplar (), aspen, and cottonwood.

The we ...

''. Plants include common reed

''Phragmites australis'', known as the common reed, is a species of flowering plant in the grass family Poaceae. It is a wetland grass that can grow up to tall and has a cosmopolitan distribution worldwide.

Description

''Phragmites australis' ...

(''Phragmites australis''), lesser Indian reed mace (''Typha

''Typha'' is a genus of about 30 species of monocotyledonous flowering plants in the family Typhaceae. These plants have a variety of common names, in British English as bulrushStreeter D, Hart-Davies C, Hardcastle A, Cole F, Harper L. 2009. ' ...

angustata '') and several species of cane

Cane or caning may refer to:

*Walking stick, or walking cane, a device used primarily to aid walking

* Assistive cane, a walking stick used as a mobility aid for better balance

* White cane, a mobility or safety device used by blind or visually i ...

– '' Schoenoplectus littoralis'', '' S. lacustris'' and endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

'' S. kasachstanicus''. Under water grow two types of ''Myriophyllum

''Myriophyllum'' (water milfoil) is a genus of about 69 species of freshwater aquatic plants, with a cosmopolitan distribution. The centre of diversity for ''Myriophyllum'' is Australia with 43 recognized species (37 endemic).

These submersed aq ...

'' – spiked ('' M. spicatum'') and whorled ('' M. verticillatum''); several kinds of ''Potamogeton

''Potamogeton'' is a genus of aquatic, mostly freshwater, plants of the family Potamogetonaceae. Most are known by the common name pondweed, although many unrelated plants may be called pondweed, such as Canadian pondweed (''Elodea canadensis' ...

'' – shining ('' P. lucens''), perfoliate ('' P. perfoliatus''), kinky ('' P. crispus''), fennel ('' P. pectinatus'') and '' P. macrocarpus''; as well as common bladderwort (''Utricularia vulgaris

''Utricularia vulgaris'' (greater bladderwort or common bladderwort) is an aquatic species of bladderwort found in Asia and Europe. The plant is free-floating and does not put down roots. Stems can attain lengths of over one metre in a single g ...

''), rigid hornwort (''Ceratophyllum demersum

''Ceratophyllum demersum'', commonly known as hornwort (a common name shared with the unrelated Anthocerotophyta), rigid hornwort, coontail, or coon's tail, is a species of flowering plant in the genus ''Ceratophyllum''. It is a submerged, free-f ...

'') and two species of ''Najas

''Najas'', the water-nymphs or naiads, is a genus of aquatic plants. It is cosmopolitan in distribution, first described for modern science by Linnaeus in 1753. Until 1997, it was rarely placed in the Hydrocharitaceae,Angiosperm Phylogeny Group ...

''. Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

, the concentration of which was 1.127 g/L in 1985, is represented by numerous species of algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

.

biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variability of life, life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and Phylogenetics, phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distribut ...

began to decline due to deterioration of water quality. Before then, there were abundant shellfish

Shellfish, in colloquial and fisheries usage, are exoskeleton-bearing Aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrates used as Human food, food, including various species of Mollusca, molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish ...

, crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s, chironomidae

Chironomidae , commonly known as non-biting midges or chironomids , are a family of Nematoceran flies with a global distribution. They are closely related to the families Ceratopogonidae, Simuliidae, and Thaumaleidae. Although many chironomid ...

and oligochaeta

Oligochaeta () is a subclass of soft-bodied animals in the phylum Annelida, which is made up of many types of aquatic and terrestrial worms, including all of the various earthworms. Specifically, oligochaetes comprise the terrestrial megadril ...

, as well as zooplankton

Zooplankton are the heterotrophic component of the planktonic community (the " zoo-" prefix comes from ), having to consume other organisms to thrive. Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents. Consequent ...

(concentration 1.87 g/L in 1985), especially in the western part. The lake hosted about 20 species of fish, 6 of which were native: Ili marinka (''Schizothorax pseudoaksaiensis''), Balkhash marinka (''S. argentatus''), Balkhash perch

The Balkhash perch (''Perca schrenkii'') is a species of perch endemic to the Lake Balkhash and Lake Alakol watershed system, which lies mainly in Kazakhstan. It is similar to the other two species of perch, and grows to a comparable size, but ha ...

(''Perca schrenkii''), '' Triplophysa strauchii'', '' T. labiata'' and Balkhash minnow (''Rhynchocypris poljakowii''). Other fish species were alien: common carp

The common carp (''Cyprinus carpio''), also known as European carp, Eurasian carp, or simply carp, is a widespread freshwater fish of eutrophic waters in lakes and large rivers in Europe and Asia.Fishbase''Cyprinus carpio'' Linnaeus, 1758/ref>Ark ...

(''Cyprinus carpio''), spine

Spine or spinal may refer to:

Science Biology

* Spinal column, also known as the backbone

* Dendritic spine, a small membranous protrusion from a neuron's dendrite

* Thorns, spines, and prickles, needle-like structures in plants

* Spine (zoology), ...

, Oriental bream (''Abramis brama orientalis''), Aral barbel

The Aral barbel (''Luciobarbus brachycephalus'') is a species of ray-finned fish in the genus '' Luciobarbus''. It is found in the Aral basin, Chu drainage and southern and western Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland b ...

(''Luciobarbus brachycephalus''), Siberian dace

The Siberian dace (''Leuciscus baicalensis'') is a species of freshwater ray-finned fish belonging to the family Leuciscidae. This fish is found in Siberian rivers draining to the Arctic Ocean, from the Ob to the Kolyma in the east, as well as in ...

(''Leuciscus baicalensis''), tench

The tench or doctor fish (''Tinca tinca'') is a freshwater, fresh- and brackish water, brackish-water fish of the order Cypriniformes found throughout Eurasia from Western Europe including Great Britain, Britain and Ireland east into Asia as far ...

(''Tinca tinca''), European perch

The European perch (''Perca fluviatilis''), also known as the common perch, redfin perch, big-scaled redfin, English perch, Euro perch, Eurasian perch, Eurasian river perch, Hatch, poor man's rockfish or in Anglophone parts of Europe, simply the ...

(''Perca fluviatilis''), wels catfish

The wels catfish ( or ; ''Silurus glanis''), also called sheatfish or just wels, is a large species of catfish native to wide areas of central, southern, and eastern Europe, in the basins of the Baltic, Black and Caspian Seas. It has been intro ...

(''Silurus glanis''), osman (''Diptychus

''Diptychus'' is a genus of freshwater ray-finned fish belonging to the family Cyprinidae, the family which includes the carps, barbs and related fishes. This genus is classified within the subfamily Schizothoracinae, the snow barbels. The two s ...

''), Prussian carp

The Prussian carp, silver Prussian carp or Gibel carp (''Carassius gibelio'') is a member of the family Cyprinidae, which includes many other fish, such as the common carp, goldfish, and the smaller minnows. It is a medium-sized cyprinid, and d ...

(''Carassius gibelio'') and others. The fishery was focused on carp, perch, asp (''Leuciscus aspius'') and bream.

Abundant and dense reeds in the southern part of the lake, especially in the delta of the Ili River, served as a haven for birds and animals. Changes in the water level led to the degradation of the delta – since 1970, its area decreased from 3,046 to 1,876km2, reducing wetlands and riparian forests which were inhabited by birds and animals. Land development, application of pesticides

Pesticides are substances that are used to pest control, control pest (organism), pests. They include herbicides, insecticides, nematicides, fungicides, and many others (see table). The most common of these are herbicides, which account for a ...

, overgrazing and deforestation also contributed to the decrease in biodiversity. Of the 342 species of vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s, 22 are endangered and are listed in the Red Book of Kazakhstan. Forests of the Ili delta were inhabited by the rare (now probably extinct) Caspian tiger

The Caspian tiger was a '' Panthera tigris tigris'' population native to eastern Turkey, northern Iran, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus around the Caspian Sea, Central Asia to northern Afghanistan and the Xinjiang region in western China. Until the Midd ...

and its prey, wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

. Around the 1940s, Canadian muskrat

The muskrat or common muskrat (''Ondatra zibethicus'') is a medium-sized semiaquatic rodent native to North America and an introduced species in parts of Europe, Asia, and South America.

The muskrat is found in wetlands over various climates ...

was brought to the Ili delta; it quickly acclimatized, feeding on ''Typha

''Typha'' is a genus of about 30 species of monocotyledonous flowering plants in the family Typhaceae. These plants have a variety of common names, in British English as bulrushStreeter D, Hart-Davies C, Hardcastle A, Cole F, Harper L. 2009. ' ...

'', and was trapped for fur, up to 1 million animals per year. However, recent changes in the water level destroyed its habitat, bringing the fur industry to a halt.

Balkhash is also the habitat of 120 types of bird, including cormorant

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed, but in 2021 the International Ornithologists' Union (IOU) ado ...

s, marbled teal

The marbled duck or marbled teal (''Marmaronetta angustirostris'') is a medium-sized species of duck from southern Europe, northern Africa, and western and central Asia. The scientific name, ''Marmaronetta angustirostris'', comes from the Greek ' ...

, pheasant

Pheasants ( ) are birds of several genera within the family Phasianidae in the order Galliformes. Although they can be found all over the world in introduced (and captive) populations, the pheasant genera's native range is restricted to Eura ...

s, golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird of pr ...

and great egret

The great egret (''Ardea alba''), also known as the common egret, large egret, great white egret, or great white heron, is a large, widely distributed egret. The four subspecies are found in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and southern Europe. R ...

; 12 of those are endangered, including great white pelican

The great white pelican (''Pelecanus onocrotalus'') also known as the eastern white pelican, rosy pelican or simply white pelican is a bird in the pelican family. It breeds from southeastern Europe through Asia and Africa, in swamps and shallow ...

, Dalmatian pelican

The Dalmatian pelican (''Pelecanus crispus''), also known as the curly-headed pelican, is the largest member of the pelican family and among the heaviest flying birds in the world. With a wingspan typically ranging between 2.7 and 3.2 meters (8.9� ...

, Eurasian spoonbill

The Eurasian spoonbill (''Platalea leucorodia''), or common spoonbill, is a wading bird of the ibis and spoonbill family Threskiornithidae, native to Europe, Africa and Asia. The species is partially migratory with the more northerly breeding popu ...

, whooper swan

The whooper swan ( /ˈhuːpə(ɹ) swɒn/ "hooper swan"; ''Cygnus cygnus''), also known as the common swan, is a large northern hemisphere swan. It is the Eurasian counterpart of the North American trumpeter swan, and the type species for the genu ...

and white-tailed eagle

The white-tailed eagle (''Haliaeetus albicilla''), sometimes known as the 'sea eagle', is a large bird of prey, widely distributed across temperate Eurasia. Like all eagles, it is a member of the family Accipitridae (or accipitrids) which also ...

.

Cities and economy

In 2005, 3.3 million people lived in the basin of the Lake Balkhash, including residents of

In 2005, 3.3 million people lived in the basin of the Lake Balkhash, including residents of Almaty

Almaty, formerly Alma-Ata, is the List of most populous cities in Kazakhstan, largest city in Kazakhstan, with a population exceeding two million residents within its metropolitan area. Located in the foothills of the Trans-Ili Alatau mountains ...

– the largest city of Kazakhstan. The largest city on the lake is Balkhash with 66,724 inhabitants (2010). It is on the northern shore and has a prominent mining and metallurgy plant. A large copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

deposit was discovered in the area in 1928–1930 and is being developed in the villages north of the lake. Part of the motorway between Bishkek

Bishkek, formerly known as Pishpek (until 1926), and then Frunze (1926–1991), is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Kyrgyzstan. Bishkek is also the administrative centre of the Chüy Region. Bishkek is situated near the Kazakhstan ...

and Karaganda

Karaganda (, ; ), also known as Karagandy (, ; ; ) (also sometimes romanized as Qaraghandy), is a major city in central Kazakhstan and the capital of the Karaganda Region. It is the fifth most populous city in the country, with a population o ...

runs along the western shore of the lake. The western shore also hosts military installations built during the Soviet era, such as radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

missile warning systems. The southern shore is almost unpopulated and has only a few villages. The nature and wild life of the lake attract tourists, and there are several resorts on the lake. In 2021, Lake Balkhash was selected as one of the top 10 tourist destinations in the country of Kazakhstan.

Fishing

The economic importance of the lake is mostly in its fishing industry. Systematic breeding of fish began in 1930; the annual catch was 20 thousand tonnes in 1952, it increased to 30 thousands in the 1960s and included up to 70% of valuable species. However, by the 1990s production fell to 6,600 tonnes per year with only 49 tonnes of valuable breeds. The decline is attributed to several factors, including the halt of reproduction programs,poaching

Poaching is the illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights.

Poaching was once performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and to supplement meager diets. It was set against the huntin ...

and decline in water level and quality.

Energy projects

megawatt

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of Power (physics), power or radiant flux in the International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantification (science), quantify the rate of Work ...

Kapshagay Hydroelectric Power Plant

The Kapshagay Hydroelectric Power Plant (, ''Qapshaǵaı sý elektr stantsııasy''; , earlier Капчагайская ГЭС) is a hydroelectricity power plant on the Ili River in Almaty Province of Kazakhstan. Constructed between 1965 and 19 ...

was built on the Ili River, drawing water out of the new Kapshagay Reservoir

Kapchagay (, ) or Qapshaghay Reservoir (, ), also known as the Qapshaghay Bogeni Reservoir and sometimes referred to as Lake Kapchagay, is a major reservoir in Almaty Region in southeastern Kazakhstan, approximately north of Almaty. The long lak ...

for irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering of plants) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has bee ...

. Ili's water is also extensively used upstream, in the Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

province of China, for the cultivation of cotton. Currently, there is a project for an additional counter-regulatory dam 23km downstream from the Kapchagay. The associated 49.5-MW Kerbulak Hydroelectric Power Plant will partially solve the problem of providing electricity to the southern areas of Kazakhstan and will serve as a buffer for daily and weekly fluctuations in the water level of the Ili River.

Energy supply to the south-eastern part of Kazakhstan is an old problem, with numerous solutions proposed in the past. Proposals to build power plants on Balkhash in the late 1970s and 1980s stalled, and the initiative to erect a nuclear plant

A nuclear power plant (NPP), also known as a nuclear power station (NPS), nuclear generating station (NGS) or atomic power station (APS) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power s ...

near the village Ulken met strong opposition from environmentalists and residents. Therefore, in 2008, the Kazakh government reconsidered and announced building of a Balkhash Thermal Power Plant

A thermal power station, also known as a thermal power plant, is a type of power station in which the heat energy generated from various fuel sources (e.g., coal, natural gas, nuclear fuel, etc.) is converted to electrical energy. The heat ...

.

However, in 2024 following a referendum, it was resolved to build a nuclear power plant.

Navigation

There is a regular ship navigation through the lake, the mouth of the Ili River, and the Kapchagay Reservoir. The main piers are Burylbaytal and Burlitobe. The ships are relatively light due to the limiting depth in some parts of the lake; they are used mainly for catching fish and transporting fish and construction materials. The total length of the

There is a regular ship navigation through the lake, the mouth of the Ili River, and the Kapchagay Reservoir. The main piers are Burylbaytal and Burlitobe. The ships are relatively light due to the limiting depth in some parts of the lake; they are used mainly for catching fish and transporting fish and construction materials. The total length of the waterway

A waterway is any Navigability, navigable body of water. Broad distinctions are useful to avoid ambiguity, and disambiguation will be of varying importance depending on the nuance of the equivalent word in other ways. A first distinction is ...

is 978km, and the navigation period is 210 days/year.

Navigation on the Lake Balkhash originated in 1931 with the arrival of two steamers and three barges. By 1996, up to 120,000 tonnes of building materials, 3,500 tonnes of ore, 45 tonnes of fish, 20 tonnes of melons and 3,500 passengers were transported on Balkhash (per year). During 2004 there were 1000 passengers and 43 tonnes of fish.

In 2004, the local fleets consisted of 87 vessels, including 7 passenger ships, 14 cargo barges and 15 tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, suc ...

s. The government projected that 2012 would see in the Ili-Balkhash basin 233,000 tonnes of construction materials, at least 550,000 tonnes of

livestock, fertiliser and foodstuffs and at least 53 tonnes of fish. Development of eco-tourism is expected to increase the passengers to 6,000 people per year.

Environmental and political issues

ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s in the lake. Unabashed industrial extraction would likely emulate the environmental disaster

An environmental disaster or ecological disaster is defined as a catastrophic event regarding the natural environment that is due to human activity.Jared M. Diamond, '' Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed'', 2005 This point distingu ...

at the Aral Sea

The Aral Sea () was an endorheic lake lying between Kazakhstan to its north and Uzbekistan to its south, which began shrinking in the 1960s and had largely dried up into desert by the 2010s. It was in the Aktobe and Kyzylorda regions of Kazakhst ...

. Since 1970, the 39 km3 outflow of water to fill the Kapchagay Reservoir led to a 66% fall in inflow from the Ili. The concomitant decrease the lake's level was about 15.6 cm/year, much greater than the natural decline of 1908–1946 (9.2 cm/year). The shallowing is acute in the western "half". From 1972 until 2001, a small salt lake Alakol, 8km south of Balkhash, had practically disappeared and the southern part of the lake lost about 150km2 of water surface. Of the 16 existing lake systems around the lake only five remain. The desertification

Desertification is a type of gradual land degradation of Soil fertility, fertile land into arid desert due to a combination of natural processes and human activities.

The immediate cause of desertification is the loss of most vegetation. This i ...

process involved about of the basin. Salt dust is blown away from the dried areas, contributing to the generation of Asian dust storm

A dust storm, also called a sandstorm, is a meteorological phenomenon common in arid and semi-arid regions. Dust storms arise when a gust front or other strong wind blows loose sand and dirt from a dry surface. Fine particles are transpo ...

s, increase the soil salinity

Soil salinity is the salt (chemistry), salt content in the soil; the process of increasing the salt content is known as salinization (also called salination in American and British English spelling differences, American English). Salts occur nat ...

and adversely influencing the climate. Increasing formation of silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension (chemistry), suspension with water. Silt usually ...

in the river's delta further reduces the inflow of water to the lake.

emissions

Emission may refer to:

Chemical products

* Emission of air pollutants, notably:

** Flue gas, gas exiting to the atmosphere via a flue

** Exhaust gas, flue gas generated by fuel combustion

** Emission of greenhouse gases, which absorb and emit rad ...

due to mining and metallurgical processes, mostly at the Balkhash Mining and Metallurgy Plant operated by Kazakhmys

Kazakhmys Group is a vertically integrated holding company whose key assets are concentrated in the mining industry and non-ferrous metallurgy. It was established and registered in the form of a joint-stock company in August 1997. On 14 January ...

. In the early 1990s, the emission level was 280–320 thousand tonnes per year, depositing 76 tonnes of copper, 68 tonnes of zinc and 66 tonnes of lead on the surface of the lake. Since then, emissions have almost doubled. Contaminants are also brought from the dump sites by the dust storms

A dust storm, also called a sandstorm, is a meteorological phenomenon common in arid and semi-arid regions. Dust storms arise when a gust front or other strong wind blows loose sand and dirt from a dry surface. Fine particles are transported ...

.

In 2000, a major conference, Balkhash 2000, brought together environmental scientists from different countries, as well as representatives of business and government. The conference adopted a resolution and appeal to the government of Kazakhstan

The Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan (, ''Qazaqstan Respublikasynyñ Ükımetı'') is the collegial body that exercises Executive branch, executive power in the Kazakhstan, Republic of Kazakhstan; The government heads the system of execu ...

and international organizations, suggesting new ways of managing the ecosystems of Alakol and Balkhash basins. At the 2005 International Environmental Forum devoted to Lake Balkhash, Kazakhmys announced that by 2006 it will restructure its processes, thereby reducing emissions by 80–90%.

Contamination of Balkhash originates not only locally, but is also brought by inflow of polluted water from China. China also consumes 14.5km3 of water per year from the Ili River, with a planned increase of 3.6 times that. The current rate of the increase is 0.5–4km3/year. In 2007, the Kazakhstan government proposed a price reduction for sales of Kazakh products to China in exchange for reduction of water consumption from Ili River, but the offer was declined by China.

See also

* Balkhash – the city at Lake Balkhash * Korzhin IslandReferences

External links

*Kazakh 'national treasure' under threat

United Nations Environmental Programme details on Lake Balkhash

RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty {{DEFAULTSORT:Balkhash Siberian Tiger Re-population Project Endorheic lakes of Asia