Badger, Shropshire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

File:Badger Dingle - sandstone outcrop.jpg, Sandstone outcrop with small caves, near the eastern end of the Upper Pool.

File:Badger Dingle - Upper Pool 01.jpg, View of the Upper Pool from its western end.

File:Badger Dingle - Upper Pool 02.jpg, Reflections of trees in the Upper pool, seen from the southern side.

File:Badger Dingle - Doric Temple 01.jpg, Reconstruction of the Doric Temple, originally commissioned by Isaac Browne, on the north side of the Dingle.

File:Badger Dingle - cascade 01.jpg, Cascades at the western end of the Upper Pool.

File:Badger Dingle - sandstone cliff.jpg, Weathered sandstone cliff on the north side of the Dingle.

File:Badger Dingle - ash tree root.jpg, Ash tree rooted in a sandstone outcrop on the northern lip of the Dingle.

File:Badger Dingle - upper bridge.jpg, Wooden bridge over the Snowdon Brook.

File:Badger Dingle - private bridge.jpg, Bridge providing private access to the Dingle over the Pattingham road.

Badger Parish Council website

* {{authority control Villages in Shropshire Civil parishes in Shropshire Tourist attractions in Shropshire Geology of Shropshire

Badger is a village and

A little later, in the early 12th century, under

A little later, in the early 12th century, under

Under the Kynnersleys, the manor again stayed in the same family for more than two centuries. An early challenge to their control came in the form of a royal appointment to the rectory. Since the dissolution of the monasteries,

Under the Kynnersleys, the manor again stayed in the same family for more than two centuries. An early challenge to their control came in the form of a royal appointment to the rectory. Since the dissolution of the monasteries,

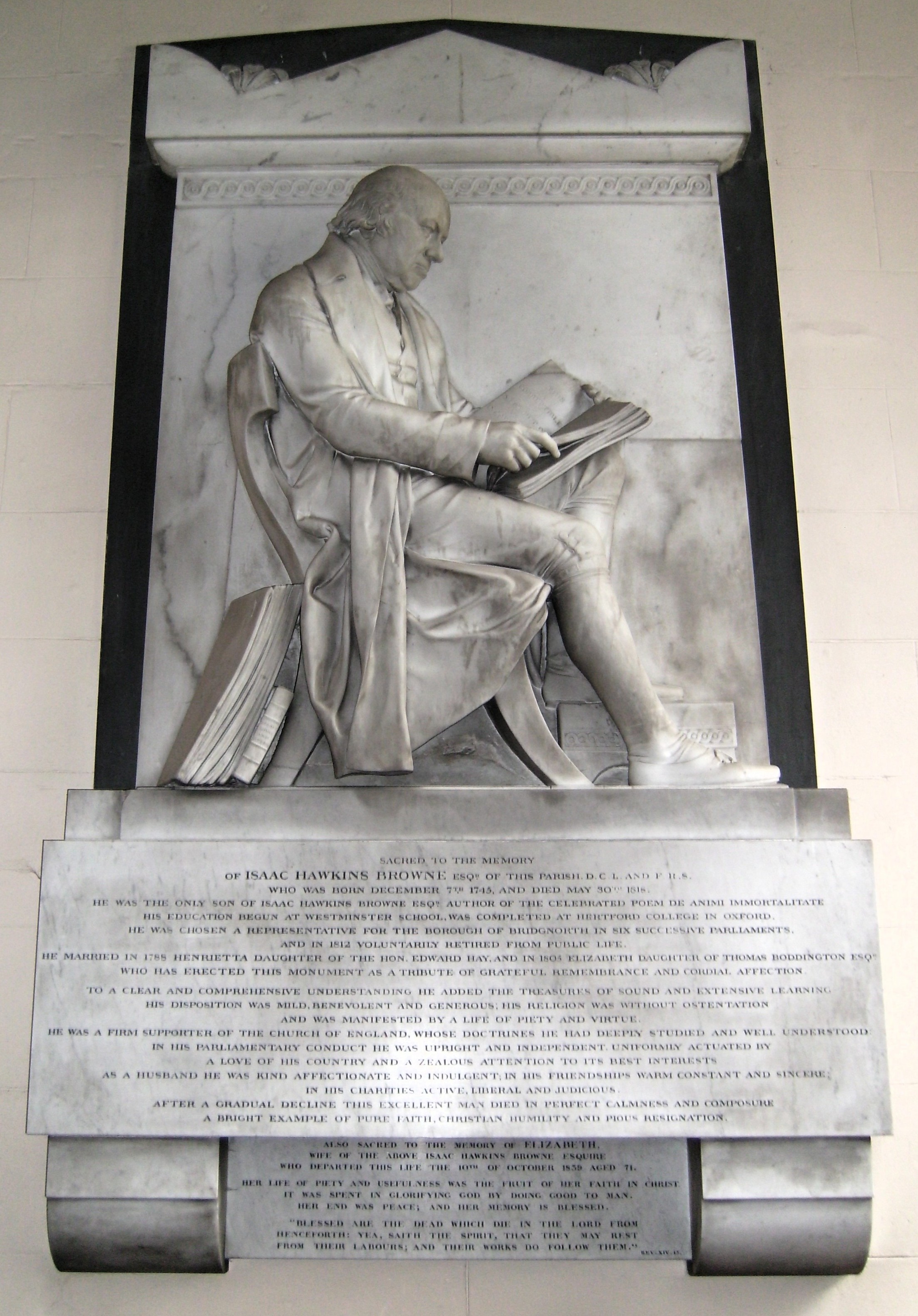

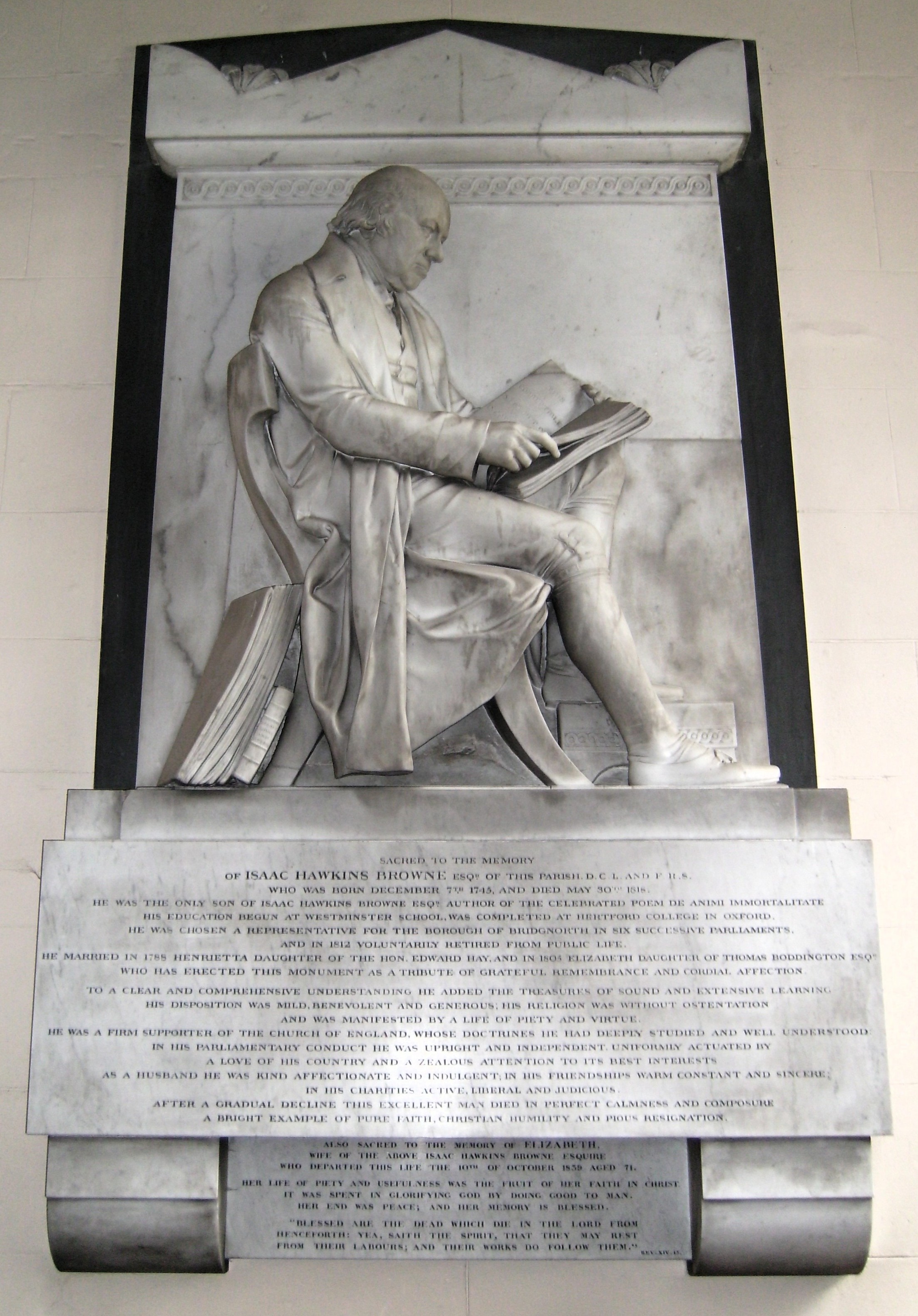

The buyer was Isaac Hawkins Browne, a

The buyer was Isaac Hawkins Browne, a

File:Badger church - exterior south east.JPG, General view of the church from the south east, showing the single pitched roof construction of

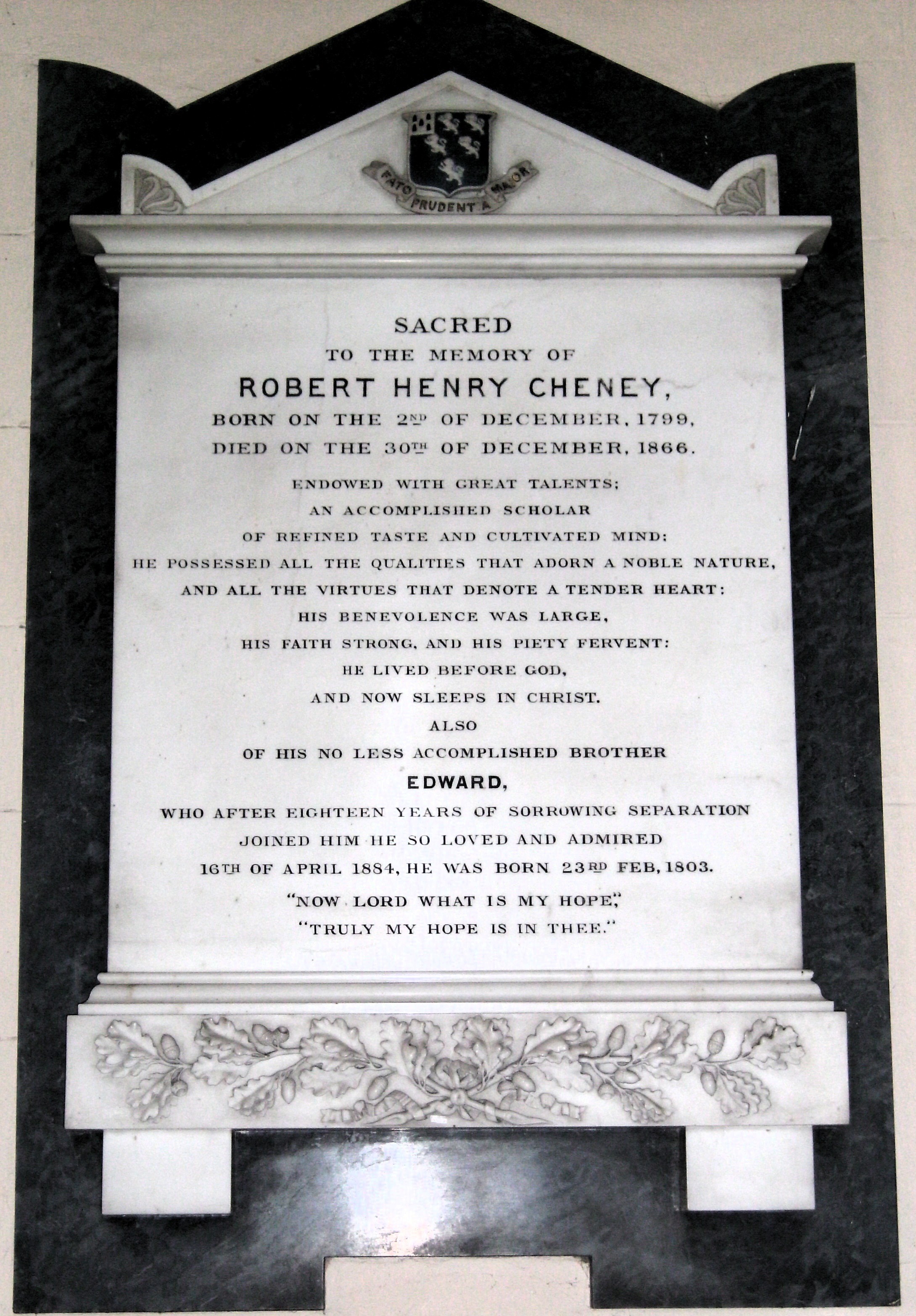

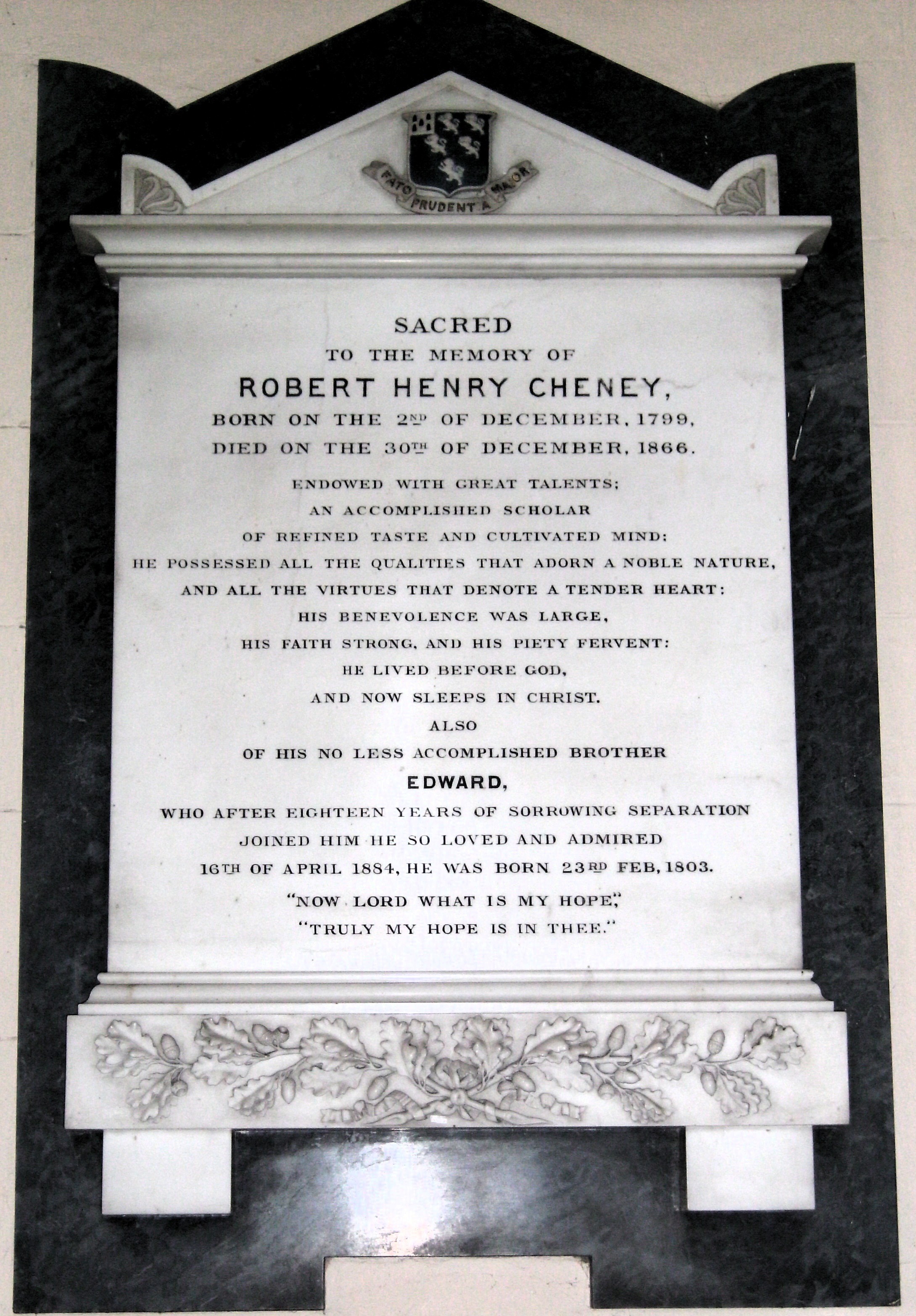

When Edward died in 1884, Badger became the property of their nephew, Alfred Capel Cure of Blake Hall, Ongar, perhaps the most colourful of Badger's lords. Capel Cure was a hero of the

When Edward died in 1884, Badger became the property of their nephew, Alfred Capel Cure of Blake Hall, Ongar, perhaps the most colourful of Badger's lords. Capel Cure was a hero of the

File:Badger church - Harriet Cheney memorial.jpg, Memorial to Harriet Cheney, by John Gibson. Harriet was the mother of R.H. Cheney, to whom Browne left the manor.

File:Badger church - Harriet Margaret Cheney memorial.jpg, Memorial to Harriet Margaret Pigot, née Cheney, by John Gibson. She was R.H. Cheney's sister, and married Robert Pigot. The Pigots, a military and political dynasty, had their seat at

. A notable example of civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government. Civil parishes can trace their origin to the ancient system of parishes, w ...

in Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, England, about six miles north-east of Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the United Kingd ...

. The parish had a population of 134 according to the 2001 census, falling to 126 at the 2011 census.

Badger Parish is at grid map reference SO 768 995. The boundaries of the parish contain the village of Badger, one side of Badger Dingle, and Badger Heath

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and is characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a coole ...

Farm. It is approximately 2.7 km at its widest point.

The village and its surroundings, particularly the Dingle, are considered a visitor attraction. In their present form they owe much to deliberate planning and landscaping in the 18th century.

Etymology

''Badger'' has its origin in theOld English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

language of the Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

. It has no connection with the mammal, spelled similarly: as late as the 1870s, the alternative spelling ''Bagsore'' was current. The late Margaret Gelling

Margaret Joy Gelling, (''née'' Midgley; 29 November 1924 – 24 April 2009) was an English toponymist, known for her extensive studies of English place-names. She served as President of the English Place-Name Society from 1986 to 1998, and ...

, a specialist in Midland toponyms

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for a proper nam ...

, formerly based at the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university in Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingham (founded in 1825 as ...

separates it into two separate elements:

:*The first element in the name, ''Bæcg'', is an Anglo-Saxon personal name – perhaps one of the Angles

Angles most commonly refers to:

*Angles (tribe), a Germanic-speaking people that took their name from the Angeln cultural region in Germany

*Angle, a geometric figure formed by two rays meeting at a common point

Angles may also refer to:

Places ...

who came to settle in the evolving kingdom of Mercia

Mercia (, was one of the principal kingdoms founded at the end of Sub-Roman Britain; the area was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlan ...

, and shared with Beckbury.

:*The second element, ''ofer'' signifies a hill spur. In a detailed discussion of this latter term, Gelling admits that it is a conjectural reconstruction of a word that never occurs separately, but is a common part of place-names, with the main concentration being in Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Shropshire and Herefordshire. It has often been construed simply as a hill or ridge, but Gelling's detailed examination of sites suggests a more precise significance: that the place is on or close to a long, narrow ridge, perhaps jutting from a larger ridge. At Badger, "the settlement lies to the E. of an appropriate hill-spur.". There is indeed a spur, rising up behind Badger Farm, with a slope to the south-east enfolding the village and running down to the Dingle, while the western slope descends to the River Worfe.

History

Medieval origins

As its name suggests, the origins of the village of Badger seem to lie in theAnglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

period. The first real evidence comes from the Domesday

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

survey of 1086, which compared the situation at that point with that before the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

. The entry translates:

:"Osbern, son of Richard, holds BADGER from Earl Roger, and Robert from him.

:Bruning held it; he was a free man.

:1/2 hide which pays tax. Land for 2 ploughs. In lordship 1 plough; 4 smallholders with 1 plough. Woodland for fattening 30 pigs.

:The value was 7s; now 10s."

This indicates the pre-Conquest Anglo-Saxon owner was Bruning, who got 10s. a year from it. It had since fallen in value, like most northern and Midland villages, and belonged to Roger de Montgomerie, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury

Roger de Montgomery (died 1094), also known as Roger the Great, was the first Earl of Shrewsbury, and Earl of Arundel, in Sussex. His father was Roger de Montgomery, seigneur of Montgomery, a member of the House of Montgomery, and was probably ...

. Osbern fitz Richard, baron of Richard's Castle

Richard's Castle is a village, castle and two civil parishes on the border of the counties of Herefordshire and Shropshire in England. The Herefordshire part of the parish had a population of 250 at the 2011 United Kingdom census, 2011 census, ...

, was one of Roger's vassals and held it as a fief

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

. However, he let it to someone called Robert.

To the four smallholders or bordar

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

s, their families must be added, but the population was obviously very small. A hide

Hide or hides may refer to:

Common uses

* Hide (skin), the cured skin of an animal

* Bird hide, a structure for observing birds and other wildlife without causing disturbance

* Gamekeeper's hide or hunting hide or hunting blind, a structure to hi ...

had been a unit of area, but by this stage it was simply a way of expressing liability to tax. Half a hide is a very small assessment. Badger was a long way down the territorial scale, its manor run by a man two levels below the regional magnate, Earl Roger.

A little later, in the early 12th century, under

A little later, in the early 12th century, under Henry I Henry I or Henri I may refer to:

:''In chronological order''

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry ...

, Earl Roger's son, Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, prais ...

, lost his earldom and the barons of Richard's Castle are at the top of the pyramid (beneath the king, of course). The history of the lordship is rather convoluted, but by the end of the 12th century, the immediate overlord was the Prior

The term prior may refer to:

* Prior (ecclesiastical), the head of a priory (monastery)

* Prior convictions, the life history and previous convictions of a suspect or defendant in a criminal case

* Prior probability, in Bayesian statistics

* Prio ...

of Wenlock.

The history of the actual occupiers or "terre tenants" of the manor is a little less complicated. William de Badger was the tenant in the mid-12th century, and he sold up to one Philip, who is soon also known as de Badger. After that it passed from father to son for nearly two centuries, until 1349, and stayed within the same family until 1402, when Alice, widow of John de Badger, died without issue. Thereafter there was a complex situation of shares in the manor held by members of the Elmbridge family, until Dorothy Kynnersley née Elmbridge conveyed it to her son, Thomas Kynnersley, in 1560.

The medieval village was probably surrounded by open fields, although there is no direct evidence of them until the 17th century, on the eve of their enclosure

Enclosure or inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land", enclosing it, and by doing so depriving commoners of their traditional rights of access and usage. Agreements to enc ...

. At that point the fields were called Batch and Middle fields and Uppsfield. It was surrounded by woods to the west and north and heathland

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and is characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a coole ...

to the east. The layout was probably very similar to the modern pattern. The church, rectory and hall form a group, and the rest of the village is strung along the road to the south of them.

The village probably acquired a church and a priest in the mid-12th century. By 1246, the living was known as a rectory

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of a given religion, serving as both a home and a base for the occupant's ministry. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, p ...

. The lord of the manor, that is the terre tenant, had the right to nominate his choice of priest to the Prior of Wenlock, although he had to pay the prior 3s. 4d. a year for the right. However, Wenlock was a Cluniac

Cluny Abbey (; , formerly also ''Cluni'' or ''Clugny''; ) is a former Order of Saint Benedict, Benedictine monastery in Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, France. It was dedicated to Saint Peter, Saints Peter and Saint Paul, Paul.

The abbey was constructed ...

house and so classed as an alien priory

Alien priories were religious establishments in England, such as monasteries and convents, which were under the control of another religious house outside England. Usually the Motherhouse, mother-house was in France.Coredon ''Dictionary of Mediev ...

, the daughter house of an abbey in France. Hence it was constantly seized by the Crown during the Hundred Years War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of England and France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy of Aquitaine and was triggered by a c ...

, so nominations were actually sent to the Crown for most of the 14th century. Because of the Wenlock connection, Badger and the neighbouring parish of Beckbury formed an exclave of the Diocese of Hereford

The Diocese of Hereford is a Church of England diocese based in Hereford, covering Herefordshire, southern Shropshire and a few parishes within Worcestershire in England, and a few parishes within Powys and Monmouthshire in Wales. The cathedral i ...

– an anomaly that persisted until 1905, when it was transferred to the Diocese of Lichfield

The Diocese of Lichfield is a Church of England diocese in the Province of Canterbury, England. The bishop's seat is located in the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint Chad in the city of Lichfield. The diocese covers of seve ...

. Several of the early incumbents seem to have been sons of the lord of the manor or of the lords of Beckbury. The rector lived on tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in money, cash, cheques or v ...

s and Easter offerings, and also had an area of glebe

A glebe (, also known as church furlong, rectory manor or parson's close(s)) is an area of land within an ecclesiastical parish used to support a parish priest. The land may be owned by the church, or its profits may be reserved to the church. ...

land and, for some centuries, the rent of a house inhabited by the Blakemans.

Early modern Badger

Under the Kynnersleys, the manor again stayed in the same family for more than two centuries. An early challenge to their control came in the form of a royal appointment to the rectory. Since the dissolution of the monasteries,

Under the Kynnersleys, the manor again stayed in the same family for more than two centuries. An early challenge to their control came in the form of a royal appointment to the rectory. Since the dissolution of the monasteries, advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, a ...

or the right to present an incumbent had technically belonged to the Crown, but the old arrangement, by which the lord of the manor made the initial nomination, still held. Indeed, the Elmbridges and the Kynnersleys alike had continued to pay their annual dues to preserve it. In 1614, James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

* James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334� ...

presented Richard Froysall to the rectory, without consulting the lord of the manor, Francis Kynnersley. Francis fought back. First he tried to stop Froysall entering the church and ordered the parishioners not to attend. Then he cut off economic support, seizing Froysall's tithes and planting trees on the glebe. He swore he would cut off Froysall's head and throw it in Badger Pool. He managed to get the rector imprisoned at Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is sited on the River Severn, northwest of Wolverhampton, west of Telford, southeast of Wrexham and north of Hereford. At the 2021 United ...

. However, Froysall apparently had some supporters, and they made off with some of Francis's oxen.

Francis seems to have done enough to vindicate his claims. The Kynnersley lords slowly crept up the social scale, serving their locality in various capacities. Thomas Kynnersley was High Sheriff of Staffordshire

This is a list of the sheriffs and high sheriffs of Staffordshire.

The sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. The sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most of the responsibilities as ...

and later High Sheriff of Shropshire

This is a list of sheriffs and high sheriffs of Shropshire

The high sheriff, sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. Formerly the high sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most of t ...

under the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

, and his grandson John was High Sheriff of Shropshire under George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George of Beltan (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

. Around 1719, John Kynnersley demolished the old timber-framed manor house and built a new hall, a substantial but unpretentious building with six ground floor rooms, just to the north of the old site.

Starting in 1662, the whole agricultural organisation of Badger was transformed. Firstly a large part of the east of the parish was hived off as a separate estate: Badger Heath, which for more than a century was farmed by the Taylor family, before being sold to the Greens in 1796. Then a large area of common land

Common land is collective land (sometimes only open to those whose nation governs the land) in which all persons have certain common rights, such as to allow their livestock to graze upon it, to collect wood, or to cut turf for fuel.

A person ...

was divided up among the cultivators. Some time after this the open field system was abandoned and the land enclosed

Enclosure or inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land", enclosing it, and by doing so depriving commoners of their traditional rights of access and usage. Agreements to enc ...

. Heathland was cleared and ploughed up: by 1748, even the Heath estate was half arable and had only 3% heathland. This set the pattern which has persisted to this day. Despite concentration of holdings, Badger's landscape remains mainly one of farms, predominantly arable but with considerable pasturage.

The population of Badger evidently remained small. In the mid-17th century the adult population seems to have been less than 50. With such a small population, most of the rectors decided they need devote only a small part of their time to the parish. In most cases, they chose to live elsewhere and combined Badger with other posts of greater profit. Thomas Hartshorn was rector from 1759 to 1780. For most of that time he also held two prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the choir ...

s under the peculiar jurisdiction of St. Peter's Collegiate Church, Wolverhampton

St Peter's Collegiate Church is located in central Wolverhampton, England. For many centuries it was a Chapel Royal, chapel royal and from 1480 a royal peculiar, independent of the Diocese of Lichfield and even the Province of Canterbury. The ...

: Hatherton, near Cannock

Cannock () is a town in the Cannock Chase district in the county of Staffordshire, England. It had a population of 29,018. Cannock is not far from the towns of Walsall, Burntwood, Stafford and Telford. The cities of Lichfield and Wolverhampton ...

and Monmore, near Wolverhampton.

John Kynnersley died without issue and passed the manor to his unmarried brother, Clement, who died in 1758. It then passed to his nephew, also called Clement, of Loxley. Both Clements had their own property near Uttoxeter

Uttoxeter ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in the East Staffordshire borough of Staffordshire, England. It is near to the Derbyshire county border.

The town is from Burton upon Trent via the A50 and the A38, from Stafford via the A51 ...

and neither lived in Badger. They rented the manor house to an ironmaster, William Ferriday. So, for many years, both the lords of the manor and the rectors were absentees, rarely seen in the village. The second Clement decided to sell Badger in 1774.

Making of the modern village

The buyer was Isaac Hawkins Browne, a

The buyer was Isaac Hawkins Browne, a Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

industrialist and a Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

politician. Returning from the Grand Tour, Browne set about living the life of a country gentleman on his Shropshire estates at Badger and at Malinslee, near Dawley

Dawley ( ) is a former mining town and civil parish in the borough of Telford and Wrekin, Shropshire, England. It was originally proposed be the main centre of the 'Dawley New Town' plan in 1963, however it was decided in 1968 to name the new ...

. He worked on his father's writings, helping to get his poetry recognised. Browne ingratiated himself with the local gentry, serving as High Sheriff for 1783 and as member of parliament for the pocket borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act of 1832, which had a very small electo ...

of Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the United Kingd ...

, a fiefdom of the Whitmore family of Dudmaston Hall

Dudmaston Hall is a 17th-century country house in the care of the National Trust in the Severn Valley, Shropshire, England.

Dudmaston Hall is located near the village of Quatt, a few miles south of the market town of Bridgnorth, just off the ...

from 1784 until 1812.

Browne spent heavily on the Hall. Between 1779 and 1783, he had it greatly extended, to a design by James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the Neoclassicism, neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy of Arts in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to ...

, with a museum, library, and conservatory, elaborate plasterwork by Joseph Rose, and paintings by Robert Smirke. Browne then turned his attention to the landscape. However, it was in his work on the landscape that Browne made his biggest and most permanent mark on the appearance of the village and its surroundings. He had the dell along the Batch Brook, on the south edge of the village, improved to a plan by William Emes

William Emes (1729 or 1730–13 March 1803) was an English landscape gardener.

Biography

Details of his early life are not known but in 1756 he was appointed head gardener to Sir Nathaniel Curzon at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire. He left this post ...

and probably his pupil, John Webb. This reshaped Badger Dingle was a notable example of the picturesque

Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in ''Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year ...

style in landscaping. It had two miles of walks, with a walk linking it to Badger Hall from its east end, cascades created by damming the brook, a "temple" and other architectural features. It seems that the pools in the village itself, which drain into the Dingle, were enlarged and reshaped at this time.

Browne was a generous landlord and employer, instituting coal allowances for the villagers and help for the poor. It was probably he who initiated and financed the main village school: this was paid for by the lords of the manor and provided primary education for the village children and others, until 1933.

Browne was also keen to ensure that the parish was better served spiritually. None of the rectors had actually lived in the parish for at least a century and communion was celebrated only four or five times a year. This was an issue that clearly troubled Browne for many years: one of his rare parliamentary speeches was in favour of compelling absent clergy to pay for replacement curates. Dr. James Chelsum, a minor scholar, was the rector from 1780. He contrived to combine his benefice at Badger with the rectory of Droxford

Droxford ( Drokensford) is a village in Hampshire, England.

Geography

The village is clustered with slight ribbon development along its main, north–south, undulating road. It is entirely on the lower half of the western slopes of the Meon ...

in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

from 1782, and a chaplaincy at Lathbury in Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (, abbreviated ''Bucks'') is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-east, Hertfordshir ...

. Although Browne must initially have trusted Chelsum, he clearly became disenchanted and arranged for his departure in 1795. Chelsum retained his other benefices until he died insane in 1801. In Chelsum's place Browne nominated William Smith, who proved a conscientious minister for 42 years. Smith was never absent from the parish for more than two weeks in the whole of his incumbency. Browne must have valued Smith greatly, as he bequeathed him the right to nominate his own successor. In the event, Smith sold the right back to Browne's widow in 1820 for £1200.

Brown's first wife was Henrietta Hay, daughter of Edward Hay, a career diplomat, and granddaughter of George Hay, 8th Earl of Kinnoull

George Henry Hay, 8th Earl of Kinnoull (23 June 1689 – 28 July 1758), styled as Viscount Dupplin from 1709 to 1719, was a British people, British peer, Tories (British political party), Tory politician, and diplomat.

Biography

He was the eld ...

. In 1802 she died and, the following year, he married Elizabeth, daughter of Thomas Boddington, a notorious apologist for the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

. When he died in 1818, he left a lifetime's interest in the hall to his wife, who lived for another 21 years. She continued Brown's benefactions, making sure the school continued. She also contributed the greater part of the cost of rebuilding the parish church, dedicated to St. Giles. In 1833, work began on the rebuilding, to a design by Francis Halley of Shifnal. The chancel and nave were reconstructed without division, under a single pitched roof, while a tower stood at the western end, above the entrance. The old materials were used where possible, although more sandstone was quarried on the estate to complete the work. Five years later, a new rectory completed the rebuilding. However, when William Smith died in 1837, Elizabeth nominated a relative, Thomas F. Boddington, as his successor. He lived for at least part of his incumbency at Shifnal

Shifnal () is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire, England, about east of Telford, 17 miles (27 km) east of Shrewsbury and 13 miles (20 km) west-northwest of Wolverhampton. It is near the M54 motorway and A5 (road), A5 road ...

.

chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

and nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

.

File:Badger church - interior 01.jpg, Interior of the church from the western end of the nave.

File:Badger church - exterior west.JPG, The west tower and porch

A porch (; , ) is a room or gallery located in front of an entrance to a building. A porch is placed in front of the façade of a building it commands, and forms a low front. Alternatively, it may be a vestibule (architecture), vestibule (a s ...

.

File:Badger church - exterior west tower.jpg, The west tower. It was this that gave most cause for concern before the rebuilding.

File:Badger church - exterior east.jpg, View of the church from the east, showing Capel Cures' north chapel to the right.

File:Badger church - north Chapel.jpg, The north chapel, dominated by the Browne memorial, but built for Alfred Capel Cure. The screen dates from the 15th century, and was moved and cut to fit its present location.

Decline and recovery

After the death of Browne's wife in 1839, the estate passed to Robert Henry Cheney, his nephew. Cheney was awatercolourist

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin 'water'), is a painting method"Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to the S ...

, specialising in architectural and landscape subjects, and he became a noted pioneer photographer

A photographer (the Greek φῶς (''phos''), meaning "light", and γραφή (''graphê''), meaning "drawing, writing", together meaning "drawing with light") is a person who uses a camera to make photographs.

Duties and types of photograp ...

. He opened the Dingle to visitors for the first time and groups of working people began to travel out from the industrial towns to walk in it. He died childless in 1866 and left the estate to his brother Edward.

When Edward died in 1884, Badger became the property of their nephew, Alfred Capel Cure of Blake Hall, Ongar, perhaps the most colourful of Badger's lords. Capel Cure was a hero of the

When Edward died in 1884, Badger became the property of their nephew, Alfred Capel Cure of Blake Hall, Ongar, perhaps the most colourful of Badger's lords. Capel Cure was a hero of the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, wounded at the assault on the Redan

Redan (a French language, French word for "projection", "salient") is a feature of fortifications. It is a work in a V-shaped Salients, re-entrants and pockets, salient angle towards an expected attack. It can be made from earthworks or other ...

in 1855. He had been introduced to photography by his uncle and pursued it enthusiastically, also specialising in architectural subjects. His work as a pioneer photographer is significant enough to have justified exhibitions in MoMA, New York and elsewhere although it goes un-noted on his memorial. He had a private family chapel added to the north side of the church. After holding Badger for 12 years, he was killed while trying to dynamite tree stumps on one of his other estates. The estate remained in the Capel Cure family until after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

The population of Badger grew throughout the first half of the 19th century. From 88 in 1801, it reached 123 in 1811, 132 in 1821, and 142 in 1831. The census of 1831 provided the first and only summary how the men of the parish were employed. Of the 37 adult males, 25 or more than two-thirds, were agricultural labourers and four were farmers. The remainder consisted of four in retail of handicrafts, one professional (perhaps the rector), a couple of servants and one other. So agriculture accounted directly for the great majority of the working men, and almost everyone depended on it at least indirectly.

The population rose steadily to a peak of 178 in 1861. After that, like most agricultural villages in the region, it suffered a prolonged decline. By 1901 it was down to 140, and in 1951 it stood at precisely its 1801 level of 88. The cause is not hard to explain. Agriculture, the only significant employer in the parish, required less and less labour. The Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in Panic of 1873, 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1899, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been e ...

hit the countryside around 1874, forcing farmers to reduce their output or sell at a loss. Thereafter, even relatively good times did nothing to raise employment, as farm amalgamations, improved crops and techniques, and mechanisation reduced the need for labour.

With the decline in population, a number of important village institutions found the going difficult. At the school Emma Grainger was mistress from 1891. She and Francis Capel Cure, the school's patron, died 1933. The school closed and thereafter, village children went to school in Beckbury or Worfield

Worfield is a village and civil parish in Shropshire in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands, England. It is northwest of London and west of Wolverhampton. It is north of Bridgnorth and southeast of Telford. The parish, which includes th ...

.

In 1952, the long-serving Rev. Archibald Dix retired and the parish was effectively amalgamated with Beckbury. Later amalgamations made it part of a benefice of six parishes. Archibald Dix died about a year after his retirement. His daughter, Margaret Dix MD FRCS, bought the rectory and lived in it until her death in 1992. She was distinguished surgeon at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery

The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (informally the National Hospital or Queen Square) is a neurological hospital in Queen Square, London. It is part of the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. It was the f ...

, and is one of the eponyms of the Dix–Hallpike test for a benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a disorder arising from a problem in the inner ear. Symptoms are repeated, brief periods of vertigo with movement, characterized by a spinning sensation upon changes in the position of the head.

* ...

. She bequeathed the house for Christian purposes within the diocese. After considerable debate, it was taken on by the Cornelius Trust, an evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

military charity, and run as a holiday home, until being sold for a private residence in 2005.

At about the same time as the ecclesiastical parish was amalgamated, the much decayed Hall and estate were sold to John Swire and Sons, a huge property, finance shipping and airline conglomerate, in whose hands it remains. Sir Adrian Swire is lord of the manor. Much of the Hall was demolished in 1953. A utility building and gatehouse was re-christened Badger Hall and survives to this day: even this is sufficiently grand to give the impression to visitors that the original Hall still exists.

However, the 1950s marked a turning point. With the increasing availability of motor cars, villages like Badger have become much more attractive places to live. The number of houses in the parish had been falling slowly, with the decline in population. Now new houses were built and the post-War village has approximately doubled in size. Obviously, this has meant a considerable change in character from a working village to a mainly residential community. Despite the growth and changes in its role, the village retains a good deal of its old and picturesque

Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in ''Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year ...

appearance, which makes it a visitor attraction still.

Geography

Location and boundaries

The village of Badger is located in the angle created by the confluence of theRiver Worfe

The River Worfe is a river in Shropshire, England. The name Worfe is said to derive from the Old English meaning to wander (or meander) which the river is notable for in its middle section. Mapping indicates that the river begins at Cosford Brid ...

, also known as the Cosford Brook, and one of its tributaries, known as the Batch, the Heath or the Snowdon Brook. The Snowdon Brook approximately defines the eastern and southern borders of the parish, and the western boundary runs close to the River Worfe: presumably the streams were the exact boundaries before deliberate diversion, as well as natural shift, moved their courses slightly. The Worfe and the Snowdon drain part of the much larger River Severn

The River Severn (, ), at long, is the longest river in Great Britain. It is also the river with the most voluminous flow of water by far in all of England and Wales, with an average flow rate of at Apperley, Gloucestershire. It rises in t ...

catchment: the Worfe flows south and then west to join the Severn from its left, just above Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the United Kingd ...

.

The village is at about 65m above sea level, but the spur to the west, which probably gives the village its name, rises to about 95m. It is about halfway along the southern edge of the parish, which is about 2.5 km east to west, and 2 km north to south, an area of 374 hectares or 924 acres.

Geology

The village and the area to its north stand on Upper MottledSandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

, a Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

deposit found in many parts of the West Midlands. This has been used extensively for building in the village, including St. Giles church. It is very evident in the Dingle, along the Snowdon Brook, where there are outcrops, cliffs and caves, artfully exposed and enhanced in the 18th century landscaping of the valley. The eastern side of the parish lies on boulder clay

Boulder clay is an unsorted agglomeration of clastic sediment that is unstratified and structureless and contains gravel of various sizes, shapes, and compositions distributed at random in a fine-grained matrix. The fine-grained matrix consists o ...

, sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is usually defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural ...

and gravel

Gravel () is a loose aggregation of rock fragments. Gravel occurs naturally on Earth as a result of sedimentation, sedimentary and erosion, erosive geological processes; it is also produced in large quantities commercially as crushed stone.

Gr ...

, or till

image:Geschiebemergel.JPG, Closeup of glacial till. Note that the larger grains (pebbles and gravel) in the till are completely surrounded by the matrix of finer material (silt and sand), and this characteristic, known as ''matrix support'', is d ...

, glacial deposits from the ice ages

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and Gre ...

.

Communications

The village has always relied on road communications. Historically, the most important road ran south from Beckbury and turned sharply at Badger to run east toPattingham

Pattingham is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Pattingham and Patshull, in the South Staffordshire district, in the county of Staffordshire, England, near the county boundary with Shropshire. Pattingham is seven miles we ...

. This has now been reshaped so that the priority lies with traffic turning south to Stableford

Stableford is a scoring system used in the sport of golf. Rather than counting the total number of strokes taken, as in regular stroke play, it involves scoring points based on the number of strokes taken at each hole. Unlike traditional scorin ...

, where the minor road joins a B-road connecting Telford

Telford () is a town in the Telford and Wrekin borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in Shropshire, England. The wider borough covers the town, its suburbs and surrounding towns and villages. The town is close to the county's eastern b ...

with the Black Country

The Black Country is an area of England's West Midlands. It is mainly urban, covering most of the Dudley and Sandwell metropolitan boroughs, with the Metropolitan Borough of Walsall and the City of Wolverhampton. The road between Wolverhampto ...

. The First Series of the Ordnance Survey shows that until Victorian times a road also used to run across the Dingle directly to Ackleton, but this has dwindled into a footpath

A footpath (also pedestrian way, walking trail, nature trail) is a type of thoroughfare that is intended for use only by pedestrians and not other forms of traffic such as Motor vehicle, motorized vehicles, bicycles and horseback, horses. They ...

.

Government

The parish of Badger is part of theunitary authority

A unitary authority is a type of local government, local authority in New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Unitary authorities are responsible for all local government functions within its area or performing additional functions that elsewhere are ...

of Shropshire Council

Shropshire Council, known between 1980 and 2009 as Shropshire County Council and prior to 1980 as Salop County Council, is the Local government in England, local authority for the non-metropolitan county of Shropshire (district), Shropshire in t ...

. This was formed by the merger of several existing district councils with Shropshire County Council

Shropshire Council, known between 1980 and 2009 as Shropshire County Council and prior to 1980 as Salop County Council, is the local authority for the non-metropolitan county of Shropshire in the West Midlands region of England. Since 2009 it h ...

.

Before the merger, Badger was part of Bridgnorth District

Bridgnorth District was a local government district in Shropshire, England, from 1974 to 2009. Its council was based in the town of Bridgnorth. The district also included the towns of Much Wenlock, Shifnal and Broseley and the villages of Albrig ...

from 1974 to 2009, in a two-tier system with the County Council

A county council is the elected administrative body governing an area known as a county. This term has slightly different meanings in different countries.

Australia

In the Australian state of New South Wales, county councils are special purpose ...

as the top tier. Previously it had been part of Shifnal Rural District

{{no footnotes, date=February 2020

Shifnal was a rural district in Shropshire, England from 1894 to 1974.

It was created from the Shifnal rural sanitary district by the Local Government Act 1894. Until 1934 it also administered two parishes i ...

since 1894.

There is also a parish council. This has a long history and originated in the old parish vestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government of a parish in England, Wales and some English colony, English colonies. At their height, the vestries were the only form of local government in many places and spen ...

, although civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civility, orderly behavior and politeness

*Civic virtue, the cultivation of habits important for the success of a society

*Civil (journalism)

''The Colorado Sun'' is an online news outlet based in Denver, Colorado. It lau ...

and ecclesiastical functions were separated in the Victorian period. Today it has five elected members.

Features

Interesting or attractive features around the village today include:The village pools

There are actually four pools in the village, but two are particularly prominent to the visitor: the Church Pool and the Town Pool. The pools are the result of damming a small stream running down to the Snowdon Brook in the Dingle. They reached approximately their present state in the late 18th century, as a result of the landscaping commissioned by Isaac Hawkins Browne and devised byWilliam Emes

William Emes (1729 or 1730–13 March 1803) was an English landscape gardener.

Biography

Details of his early life are not known but in 1756 he was appointed head gardener to Sir Nathaniel Curzon at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire. He left this post ...

, but they had been a central feature of the village for centuries before, as evinced by Francis Kynnersley's threat to throw the rector into the pond in 1614.

St. Giles' parish church

The parish church is a small but good example ofGothic Revival architecture

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an Architectural style, architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half ...

. Rebuilt from 1833, using the original site and materials as far as possible, it contains a notable selection of funerary art, including work by Francis Leggatt Chantrey

Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey (7 April 1781 – 25 November 1841) was an English sculptor. He became the leading portrait sculptor in Regency era Britain, producing busts and statues of many notable figures of the time. Chantrey's most notable w ...

, John Flaxman

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British sculptor and draughtsman, and a leading figure in British and European Neoclassicism. Early in his career, he worked as a modeller for Josiah Wedgwood's pottery. He spent several yea ...

and John Gibson. Location: .

Patshull Hall

Patshull Hall is a substantial Georgian mansion house situated near Pattingham in Staffordshire, England. It is a Grade I listed building and by repute is one of the largest listed buildings in the county.

History

The Hall was built to designs ...

, east of Badger.

File:Badger church - Green memorial.jpg, Memorial to the Greens of Badger Heath. They contributed a considerable £100 to the rebuilding of the church in 1833–34.

File:Badger church - Emma Grainger.jpg, Memorial to the long-serving teacher, Emma Grainger, whose death signalled the end of the school.

File:Badger church - Dix window.jpg, The Dix Window. Margaret Dix, daughter of the last rector, was a neuro-otologist. The Aramaic word ephphatha

There exists a consensus among scholars that Jesus, Jesus of Nazareth spoke the Aramaic, Aramaic language. Aramaic was the common language of Judaea (Roman province), Roman Judaea, and was thus also spoken by Jesus' disciples. The villages of Na ...

is that attributed to Jesus when healing a deaf and dumb man.

Badger Dingle

Badger Dingle is listed Grade II inHistoric England

Historic England (officially the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England) is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. It is tasked with prot ...

's Register of Parks and Gardens #REDIRECT Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England #REDIRECT Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England

{{R from move ...

{{R from move ...picturesque

Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in ''Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year ...

landscape architecture

Landscape architecture is the design of outdoor areas, landmarks, and structures to achieve environmental, social-behavioural, or aesthetic outcomes. It involves the systematic design and general engineering of various structures for constructio ...

, this narrow valley to the south of the village was opened to the public in 1851. Although it has undergone periods of decay, it is now fairly accessible, with paths easily passable in dry weather and a new bridge above the Upper Pool making circular walks feasible. The best entrances are opposite the village cemetery. Badger Dingle is believed to be the original for "Badgwick Dingle" mentioned in the ''Blandings'' novels of P.G. Wodehouse

Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse ( ; 15 October 1881 – 14 February 1975) was an English writer and one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century. His creations include the feather-brained Bertie Wooster and his sagacious valet, Je ...

, whose family during his youth lived at nearby Stableford in Worfield

Worfield is a village and civil parish in Shropshire in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands, England. It is northwest of London and west of Wolverhampton. It is north of Bridgnorth and southeast of Telford. The parish, which includes th ...

parish. Location: .

See also

* List of civil parishes in Shropshire * Listed buildings in Badger, ShropshireReferences

External links

Badger Parish Council website

* {{authority control Villages in Shropshire Civil parishes in Shropshire Tourist attractions in Shropshire Geology of Shropshire