Bacon’s Rebellion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion by

Despite most new members being sympathetic to Bacon's grievances, Governor Berkeley at first exerted control over the newly elected House of Burgesses. Berkeley first insisted upon the legislature taking care of Indian business, but a debate as to whether the House would ask for two Councillors to sit with the committee on Indian Affairs never came to a vote, and the Queen of the Pamunkeys demanded compensation for the former war in which her husband had been killed assisting the English as a precondition to furnishing warriors in this conflict, although ultimately the burgesses authorized an army of 1000 men. The recomposed House of Burgesses ultimately enacted a number of sweeping reforms, known as Bacon's Laws discussed below. However, by this time Bacon had escaped Jamestown, telling Berkeley that his own wife was ill, but soon placing himself at the head of a volunteer army in

Despite most new members being sympathetic to Bacon's grievances, Governor Berkeley at first exerted control over the newly elected House of Burgesses. Berkeley first insisted upon the legislature taking care of Indian business, but a debate as to whether the House would ask for two Councillors to sit with the committee on Indian Affairs never came to a vote, and the Queen of the Pamunkeys demanded compensation for the former war in which her husband had been killed assisting the English as a precondition to furnishing warriors in this conflict, although ultimately the burgesses authorized an army of 1000 men. The recomposed House of Burgesses ultimately enacted a number of sweeping reforms, known as Bacon's Laws discussed below. However, by this time Bacon had escaped Jamestown, telling Berkeley that his own wife was ill, but soon placing himself at the head of a volunteer army in

When Bacon's forces again reached Jamestown, it seemed impregnable, approachable only via a narrow isthmus defended by three heavy guns. Nonetheless, Bacon ordered a crude fortification constructed at the end of the isthmus, and when Berkeley's forces fired on the crude structure, sent out parties of horse troops to gather the wives of some of the governor's supporters. Thus, Elizabeth Page, Angelica Bray, Anna Ballard, Frances Thorpe and Elizabeth Bacon (wife of his senior cousin) were placed on the ramparts together with some Native American prisoners, to be endangered should firing resume. On September 15, some of Berkeley's troops sallied out, but without success, so Berkeley's Councillors advised abandoning the town. They spiked the guns, took stores aboard vessels and slipped down the river at night. Bacon's forces thus retook the town. However, Bacon also learned that his former follower,

When Bacon's forces again reached Jamestown, it seemed impregnable, approachable only via a narrow isthmus defended by three heavy guns. Nonetheless, Bacon ordered a crude fortification constructed at the end of the isthmus, and when Berkeley's forces fired on the crude structure, sent out parties of horse troops to gather the wives of some of the governor's supporters. Thus, Elizabeth Page, Angelica Bray, Anna Ballard, Frances Thorpe and Elizabeth Bacon (wife of his senior cousin) were placed on the ramparts together with some Native American prisoners, to be endangered should firing resume. On September 15, some of Berkeley's troops sallied out, but without success, so Berkeley's Councillors advised abandoning the town. They spiked the guns, took stores aboard vessels and slipped down the river at night. Bacon's forces thus retook the town. However, Bacon also learned that his former follower,

Although rebel forces were suppressed, the colony was in a deplorable condition, with many plantations deserted or plundered. The government lacked money, and the absence of labor had resulted in small harvests of both tobacco and grain. Nonetheless, at year's end, tobacco ships began to come in with supplies of clothing, cloth, medicines, and sundries.

Although rebel forces were suppressed, the colony was in a deplorable condition, with many plantations deserted or plundered. The government lacked money, and the absence of labor had resulted in small harvests of both tobacco and grain. Nonetheless, at year's end, tobacco ships began to come in with supplies of clothing, cloth, medicines, and sundries.

Colonial America: From Jamestown to Yorktown

', Macmillan, 2002, p. 63

In November 1676, Herbert Jeffreys was appointed by Charles II as a lieutenant governor of Virginia colony and arrived in Virginia in February 1677. During Bacon's Rebellion, Jeffreys was commander-in-chief of the regiment of six warships carrying over 1,100 troops, tasked with quelling and pacifying the rebellion upon their arrival. He served as leader of a three-member commission (alongside Sir John Berry and Francis Moryson) to inquire into the causes of discontent and political strife in the colony. The commission published a report for the King titled ''"A True Narrative of the Rise, Progresse, and Cessation of the late Rebellion in Virginia,"'' which provided an official report and history of the insurrection.

On 27 April 1677, with the support of the King, Jeffreys assumed the role of acting colonial governor following Bacon's Rebellion, succeeding Berkeley. Shortly after Jeffreys took over as acting governor, Berkeley angrily remarked that Jeffreys had an "irresistible desire to rule this country" and that his action could not be justified. He wrote to Jeffreys, "I believe that the inhabitants of this Colony will quickly find a difference between your management and mine."

As acting governor, Jeffreys was responsible for appeasing the remaining factions of resistance and reforming the colonial government to be once more under direct

In November 1676, Herbert Jeffreys was appointed by Charles II as a lieutenant governor of Virginia colony and arrived in Virginia in February 1677. During Bacon's Rebellion, Jeffreys was commander-in-chief of the regiment of six warships carrying over 1,100 troops, tasked with quelling and pacifying the rebellion upon their arrival. He served as leader of a three-member commission (alongside Sir John Berry and Francis Moryson) to inquire into the causes of discontent and political strife in the colony. The commission published a report for the King titled ''"A True Narrative of the Rise, Progresse, and Cessation of the late Rebellion in Virginia,"'' which provided an official report and history of the insurrection.

On 27 April 1677, with the support of the King, Jeffreys assumed the role of acting colonial governor following Bacon's Rebellion, succeeding Berkeley. Shortly after Jeffreys took over as acting governor, Berkeley angrily remarked that Jeffreys had an "irresistible desire to rule this country" and that his action could not be justified. He wrote to Jeffreys, "I believe that the inhabitants of this Colony will quickly find a difference between your management and mine."

As acting governor, Jeffreys was responsible for appeasing the remaining factions of resistance and reforming the colonial government to be once more under direct

The Invention of the White Race, Vol. 2: The Origins of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America.

' London: Verso (1997). * Billings, Warren M. "The Causes of Bacon's Rebellion: Some Suggestions," ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography,'' 1970, Vol. 78 Issue 4, pp. 409–435 * Cave, Alfred A. "Lethal Encounters: Englishmen and Indians in Colonial Virginia" (University of Nebraska Press, 2011) pp. 147–165 * Cullen, Joseph P. "Bacon's Rebellion," ''American History Illustrated,'' Dec 1968, Vol. 3 Issue 8, p. 4 ff., popular account. * Frantz, John B. ed. ''Bacon's Rebellion: Prologue to the Revolution?'' (1969), excerpts from primary and secondary source

online

* Morgan, Edmund S. (1975) ''American slavery, American freedom: the ordeal of colonial Virginia'' (1975) pp. 250–270. * Rice, James D. "Bacon's Rebellion in Indian Country," ''Journal of American History,'' vol. 101, no. 3 (Dec. 2014), pp. 726–750. * Tarter, Brent. "Bacon's Rebellion, the Grievances of the People, and the Political Culture of Seventeenth-Century Virginia," ''Virginia Magazine of History & Biography'' (2011) 119#1 pp 1–41. * * * Wertenbaker, Thomas Jefferson. ''Torchbearer of the Revolution: The Story of Bacon's Rebellion and its Leader'' (

Bacon's Rebellion

at ''

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

settler

A settler or a colonist is a person who establishes or joins a permanent presence that is separate to existing communities. The entity that a settler establishes is a Human settlement, settlement. A settler is called a pioneer if they are among ...

s that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon against Colonial Governor William Berkeley, after Berkeley refused Bacon's request to drive Native American Indians out of Virginia. Thousands of Virginians from all classes (including those in indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an " indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or s ...

) and races rose up in arms against Berkeley, chasing him from Jamestown and ultimately torching the settlement. The rebellion was first suppressed by a few armed merchant ships from London whose captains sided with Berkeley and the loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

.

Government forces led by Herbert Jeffreys arrived soon after and spent several years defeating pockets of resistance and reforming the colonial government to be once more under direct Crown control. While the rebellion did not succeed in the initial goal of driving the Native Americans from Virginia, it did result in Berkeley being recalled to England, where he died shortly thereafter.

Bacon's rebellion was the first rebellion in the North American colonies in which discontented frontiersmen took part. A somewhat similar uprising in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

involving John Coode and Josias Fendall

Josias Fendall( – ) was an English colonial administrator who served as the Proprietary Governor of Maryland. He was born in England, and came to the Province of Maryland. He was the progenitor of the Fendall family in America.

Biography E ...

took place in 1689. The alliance between European indentured servants and Africans

The ethnic groups of Africa number in the thousands, with each ethnicity generally having their own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. The ethnolinguistic groups include various Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Sahara ...

(a mix of indentured, enslaved, and Free Negroes) disturbed the colonial upper class. They responded by hardening the racial caste of slavery in an attempt to divide the two races from subsequent united uprisings with the passage of the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705

The Virginia Slave Codes of 1705 (formally entitled An act concerning Servants and Slaves), were a series of laws enacted by the Colony of Virginia's House of Burgesses in 1705 regulating the interactions between slaves and citizens of the crow ...

.

Prelude

Starting in the 1650s, when high tobacco prices encouraged both tobacco planting and immigration, colonists began cutting forests as well as trying to farm tobacco on land already cleared by Native Americans. Whereas decades earlier, Native Americans had been able to trade foodstuffs which they had grown and captured for trade goods, colonists had learned to farm grain and raise livestock for themselves; furs (caught and prepared by natives or frontiersmen) became the new primary trade good. Tensions arose because native croplands were not only attractive to the colonists' generally free-roving pigs (which damaged their crops), but easily switched to tobacco. Because colonists' farming methods drained fields of nutrients (both because of erosion and because fertilization was rarely practiced or effective for more than another century), new fields were constantly sought. Furthermore, more emigrants were surviving their indentures and thus wanted to establish themselves with their new skills as tobacco farmers. In Virginia'sNorthern Neck

The Northern Neck is the northernmost of three peninsulas (traditionally called "necks" in Virginia) on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay in the Commonwealth of Virginia (along with the Middle Peninsula and the Virginia Peninsula). The P ...

(a relatively undeveloped area in the watersheds of the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the enti ...

and Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

s between cleared and farmed land in southeastern Virginia and cleared and farmed land in eastern Maryland), rather than rent farmland from their former employers, freed indentured servants and other European immigrants began clearing and squatting on land that the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

had reserved for Native Americans since 1634. However, with the Restoration of the English monarchy

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state. This may refer to:

*Conservation and restoration of cultural property

**Audio restoration

**Conservation and restoration of immovable cultural property

**Film restoration

** Image ...

following the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, fewer people chose to emigrate from England to flee that internal conflict. Between the First Anglo-Dutch War

The First Anglo-Dutch War, or First Dutch War, was a naval conflict between the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Republic. Largely caused by disputes over trade, it began with English attacks on Dutch merchant shipping, but expanded to vast ...

and the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, began on 4 March 1665, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda (1667), Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667. It was one in a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars, naval wars between Kingdom of England, England and the D ...

, the Crown adopted Navigation Acts

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce with other countries and with its own colonies. The laws al ...

, in particular a new rule that tobacco grown in the colonies could be sold only to English merchants and shipped to England on English ships. Since much colonial tobacco was of low quality and usually sold to Dutch traders or to the Continental market, English merchants had an oversupply of tobacco by the mid-1600s, and its price plummeted. Thus, while the Dutch had paid three pence per pound for tobacco and a small planter could grow 1,000 pounds in a year, English traders would pay only a half penny per pound or less.

Virginia's governor, William Berkeley, had taken office and sailed to the colony shortly before the English Civil War began, and remained in office or with significant power for about 35 years. Berkeley had traveled back to England to fight (unsuccessfully) for King Charles before returning to the colony in 1645 after Natives had massacred settlers in 1644. He led military forces which captured the chief Opechancanough

Opechancanough ( ; – ) was a sachem (or paramount chief) of the Powhatan Confederacy in present-day Virginia from 1618 until his death. He had been a leader in the confederacy formed by his older brother Powhatan, from whom he inherited t ...

and suppressed the revolt. Berkeley also had a royal monopoly of the important beaver fur trade and charged fur traders in the interior a license fee for bringing furs which they or Native Americans gathered and which the traders then sold to Berkeley's company. Berkeley grew unpopular after the Dutch were defeated, in part because the tobacco boom had ended, as well as because of the conflict and more personal reasons. Like King Charles, Berkeley refused to call for legislative elections for more than a decade during the English Civil Wars (during part of which Puritan-leaning Richard Bennett, Edward Digges

Edward Digges (14 February 1620 – 15 March 1674/75) was an English barrister and colonist who became a premium tobacco planter and official in the Virginia colony. The son of the English politician Dudley Digges represented the colony before ...

and Samuel Mathews had replaced him as the colony's chief executive during the "Long Assembly"). He also issued large land grants to favorites (of 2,000, 10,000 or even 30,000 acres) and was extremely wealthy compared to small planters (owning Green Spring Plantation

Green Spring Plantation in James City County about west of Williamsburg, was the 17th century plantation of one of the most unpopular governors of Colonial Virginia in North America, Sir William Berkeley, and his wife, Frances Culpeper B ...

outside Jamestown, as well as 5 houses in the colonial capital which he mostly rented out, 400 cattle and 60 horses, as well as several hundred sheep, valuable household silver and nearly a thousand pounds sterling worth of grain in storage). Berkeley's favorites often commanded the local militia in various counties, as well as charging quitrent

Quit rent, quit-rent, or quitrent is a tax or land tax imposed on occupants of freehold or leased land in lieu of services to a higher landowning authority, usually a government or its assigns.

Under English feudal law, the payment of quit rent ...

s to smaller farmers who cleared and farmed the land on their vast estates. In 1662 Governor Berkeley warned English officials that the low tobacco prices did not even cover freight and customs charges, much less provide a subsistence income for small farmers, who grew discontent, and in 1667 several weather events caused the tobacco crop to fail. Nonetheless, after the Restoration of the monarchy, the king granted English-based favorites the Northern Neck Proprietary

The Northern Neck Proprietary – also called the Northern Neck land grant, Fairfax Proprietary, or Fairfax Grant – was a land grant first contrived by the exiled English King Charles II in 1649 and encompassing all the lands bounded by the Pot ...

and the right to 11 years' worth of quitrents in arrears (which seemed like additional taxes). Discontent had become widespread by 1670, when most landless taxpayers lost the right to vote for representatives in the House of Burgesses. One set of aggrieved petitioners met at Lawne's Creek parish church across from Jamestown in December 1673, and in 1674 two rebellions in Virginia failed for want of leaders.

Meanwhile, Susquehannock

The Susquehannock, also known as the Conestoga, Minquas, and Andaste, were an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian people who lived in the lower Susquehanna River watershed in what is now Pennsylvania. Their name means “people of the muddy river.”

T ...

peoples from Pennsylvania and northern Maryland had been displaced by the peoples aligned with the Iroquois Confederation

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of Native Americans and First Nations peopl ...

and moved south into Maryland (where they were initially welcomed) and Virginia. Secocowon (then known as Chicacoan), Doeg, Patawomeck

The Patawomeck are a Native American tribe based in Stafford County, Virginia, along the Potomac River. ''Patawomeck'' is another spelling of Potomac.

The Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia is a state-recognized tribe in Virginia that identif ...

and Rappahannock natives began moving into the Northern Neck region as they were displaced from Maryland as well as rapidly settling areas of eastern Virginia, and joined local tribes in defending their land and resources. In June 1666, Governor Berkeley told General Robert Smith of Rappahanock County that Native Americans in the colony's northern part could be destroyed, in order to provide a "great Terror and Example and Instruction to all other Indians", and that an expedition against them could be funded by enslaving the women and children and selling them outside the colony. Allowing enslavement of Indians for damages done to frontiersman had been permitted by the General Assembly in the case of John Powell of Northumberland County. Thus, soon colonists declared war on the nearby natives. By 1669, colonists had patented the land on the west of the Potomac as far north as My Lord's Island (now Theodore Roosevelt Island in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

). By 1670, they had driven most of the Doeg out of the Virginia colony and into Maryland, apart from those living beside the Nanzatico/Portobago in Caroline County, Virginia

Caroline County is a United States county located in the eastern part of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The northern boundary of the county borders on the Rappahannock River, notably at the historic town of Port Royal. The Caroline county se ...

.

Motives

Bacon's rebellion was motivated by bothclass

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

and ethnic

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

conflict.

On the one hand, the Rebellion featured a coalition of both black and white laborers, including women, against the Virginia aristocracy represented by Governor Berkeley.

At the same time, the primary policy disagreement between Bacon and Berkeley was in how to handle the Native American population, with Bacon favoring harsher measures. Berkeley believed that it would be useful to keep some as subjects, stating, "I would have preserved those Indians that I knew were hoeurly at our mercy to have beene our spies and intelligence to find out the more bloudy Ennimies", whereas Bacon found this approach too compassionate, stating, "Our Design s... to ruin and extirpate all Indians in General."

Rebellion

Native American raids

In July 1675, Doeg Indians inStafford County, Virginia

Stafford County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is approximately south of Washington, D.C. It is part of the Northern Virginia region, and the D.C area. It is one of the fastest-growing and highest-income counties in ...

, killed two settlers and destroyed fields of corn and cattle. The Stafford County militia tracked down the raiders, killing 10 Doeg in a cabin. Meanwhile, another militia, led by Colonel Mason and Captain George Brent

George Brent (born George Brendan Nolan; 15 March 1904 – 26 May 1979) was an Irish-American stage, film, and television actor. He is best remembered for the eleven films he made with Bette Davis, which included ''Jezebel'' and ''Dark Victory ...

, attacked a nearby cabin of the friendly Susquehannock

The Susquehannock, also known as the Conestoga, Minquas, and Andaste, were an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian people who lived in the lower Susquehanna River watershed in what is now Pennsylvania. Their name means “people of the muddy river.”

T ...

tribe and killed 14 of them. The attack ceased only when someone from the cabin managed to escape and confront Mason, telling him that they were not Doegs. On August 31, Virginia Governor William Berkeley proclaimed that the Susquehannock had been involved in the Stafford County attack with the Doeg. On September 26, 1,000 members of Maryland militia led by Major Thomas Trueman marched to the Susquehannock stronghold in Maryland. They were soon joined by Virginia militia led by Col. John Washington

John Washington (1633 – 1677) was an English-born merchant, planter, politician and military officer. Born in Tring, Hertfordshire, he subsequently immigrated to the English colony of Virginia and became a member of the planter class. In add ...

and Col. Isaac Allerton Jr.

Col. Isaac Allerton Jr. ( 1627/1630 – December 30, 1702) was planter, military officer, politician and merchant in colonial America. Like his father, he first traded in New England, and after his father's death, in Virginia. There, he served o ...

Trueman invited five Susquehannock chiefs to a parley. After the chiefs denied responsibility for the July attacks in Stafford County despite witnesses having noticed Susquehannocks wearing clothing of some murdered settlers, they were killed without trial and despite the parley promises as well as a medal of Lord Baltimore and paper pledge from a former Maryland governor produced by one of the chiefs. Although the tribesmen in the fort continued to resist despite their leaders' unexplained disappearance, many ultimately managed to escape with their wives and children. Maryland authorities impeached Major Trueman, and Governor Berkeley expressed outrage when he heard about the massacre.

In January 1676, Susquehannocks retaliated by attacking plantations, killing 60 settlers in Maryland and a further 36 in Virginia. Other tribes joined in, killing settlers, burning houses and fields and slaughtering livestock as far south as the James

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

and York River watersheds.Alfred A. Cave, ''Lethal Encounters: Englishmen and Indians in Colonial Virginia'' (University of Nebraska Press, 2011) pp. 148–161

Berkeley's forts and Bacon's raiders

After raids in Virginia in February 1676, Berkeley initially called up the Virginia militia under SirHenry Chicheley

Sir Henry Chicheley (b. 1614 or 1615 – d. February 5, 1683) was a Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, lieutenant governor of Colony of Virginia, Virginia Colony who also served as Acting Governor during multiple periods in the aftermath of Bacon ...

and Col. Goodrich to pursue the raiders but soon recalled that expedition and decided upon a defensive war. The House of Burgesses approved of Berkeley's plan to build and staff eight forts along the frontier with 500 men, provided for the enlistment of friendly natives, and prohibited selling firearms to "savages". When no militia deaths were reported in April and May, Berkeley proclaimed his plan a success, but Bacon's people complained that garrisons could not pursue raiders without the governor's express permission, and meanwhile outlying plantations were burned, livestock stolen, and settlers killed or taken captive. Frontier planters demanded the right to defend themselves. Bacon later attributed these actions to Berkeley's desire not to impede the beaver fur trade, but historians also note that militia were often unwilling to distinguish between friendly and unfriendly natives. Upset at Governor Berkeley's refusal to retaliate against the Native Americans' raids, farmers in Charles City County

Charles City County is a county located in the U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated southeast of Richmond and west of Jamestown. It is bounded on the south by the James River and on the east by the Chickahominy River.

The a ...

gathered near Merchant's Hope on the James River, the scene of a massacre in 1622

Events

January–May

* January 7 – The Holy Roman Empire and Transylvania sign the Peace of Nikolsburg.

* February 8 – King James I of England dissolves the Parliament of England, English Parliament.

* March 12 – ...

upon hearing rumors of a new raiding party. Nathaniel Bacon arrived with a quantity of brandy; after it was distributed, he was elected leader.

Against Berkeley's previous order, and as Bacon sought a commission to go and attack Indians, his armed militiamen crossed the Chickahominy River into New Kent County nominally seeking the Susquehannock warriors responsible for recent raids and so traveled first toward the Pamunkey

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is a federally recognized tribe of Pamunkey people in Virginia. They control the Pamunkey Indian Reservation in King William County, Virginia. Historically, they spoke the Pamunkey language.

They are one of 11 Native ...

lands, only to find the people had fled into Dragon Swamp. They then continued westward toward the Seneca Trail, a travel and trading path along the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

. Governor Berkeley was furious that Bacon's militia had driven the Pamunkeys into hiding and declared the action illegal and rebellious, notwithstanding Bacon's letter ordering payment of money he owed the governor and reiterating that he had no evil intentions against the government nor him. However, not finding Susquehannocks, Bacon's militiamen turned their back upon settlements and struck south until they came to the Roanoke River

The Roanoke River ( ) runs long through southern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the United States. A major river of the southeastern United States, it drains a largely rural area of the coastal plain from the eastern edge of the ...

and the Occaneechi

The Occaneechi are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands whose historical territory was in the Piedmont region of present-day North Carolina and Virginia.

In the 17th century they primarily lived on the large, long Occoneechee Island ...

people in May. After convincing Occaneechi warriors (and their Mannikin allies) to leave their villages and attack the Susquehannock to the west, Bacon and his men refused to pay for those services but instead demanded provisions and beaver pelts. Not receiving them, they murdered the Occaneechi chief and most of the Occaneechi men, women, and children, which ranged from 100 to 400 people, remaining at the villages, then plundered their larders before proceeding eastward back toward Jamestown.Wertenbaker pp. 19–20 Meanwhile, Berkeley had gathered about 300 men and led them to the falls of the James River (modern day Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

), but too late to intercept Bacon's forces. So, he issued another proclamation declaring Bacon and his followers as unlawful, mutinous and rebellious, and his wife issued her own proclamation that Bacon's promises to provide for his follower's wives and children only promoted vain hopes. Lady Berkeley declared that Bacon owed his trading partner William Byrd I

William Byrd I (1652 – December 4, 1704) was an English-born Virginia colonist and politician. He came from the Shadwell section of London, where his father John Bird (c. 1620–1677) was a goldsmith. His family's ancestral roots were in Chesh ...

400 pounds sterling and his cousin Nathaniel Bacon Sr. 200 pounds sterling and that his own father had refused to honor his bills of exchange.

Returning to Jamestown

Upon returning to their lands inHenrico County

Henrico County , officially the County of Henrico, is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 334,389 making it the fifth-most populous county in Virginia. Henrico Coun ...

, Bacon's faction discovered that Berkeley had called for new elections to the House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses () was the lower house of the Virginia General Assembly from 1619 to 1776. It existed during the colonial history of the United States in the Colony of Virginia in what was then British America. From 1642 to 1776, the Hou ...

to better address the Native American raids and other matters. Ignoring the sheriff's reading of Berkeley's proclamation against Bacon, voters elected Bacon and his friend Capt. James Crews

James Crewes (or Crews) (1622 26 January 1677) was a British merchant who traded with the Virginia colony before emigrating there. He became a planter in Henrico County, Virginia, Henrico County and represented it for one session of the House o ...

to represent them in the House of Burgesses. However, when Bacon and 40 of his armed followers attempted to dock their sloop at Jamestown, they were fired on by the fort, and so disembarked under cover of darkness to consult with followers Richard Lawrence and William Drummond at a tavern. However, he was discovered returning to his sloop, chased upriver, and forced to surrender to Capt. Thomas Gardiner of the warship ''Adam and Eve''. Upon being taken to the Governor, Bacon behaved as a gentleman and was granted leniency—parole upon signing a paper promising to refrain from further disobedience to the government, then allowed to plead his submission before the Governor's Council.

Despite most new members being sympathetic to Bacon's grievances, Governor Berkeley at first exerted control over the newly elected House of Burgesses. Berkeley first insisted upon the legislature taking care of Indian business, but a debate as to whether the House would ask for two Councillors to sit with the committee on Indian Affairs never came to a vote, and the Queen of the Pamunkeys demanded compensation for the former war in which her husband had been killed assisting the English as a precondition to furnishing warriors in this conflict, although ultimately the burgesses authorized an army of 1000 men. The recomposed House of Burgesses ultimately enacted a number of sweeping reforms, known as Bacon's Laws discussed below. However, by this time Bacon had escaped Jamestown, telling Berkeley that his own wife was ill, but soon placing himself at the head of a volunteer army in

Despite most new members being sympathetic to Bacon's grievances, Governor Berkeley at first exerted control over the newly elected House of Burgesses. Berkeley first insisted upon the legislature taking care of Indian business, but a debate as to whether the House would ask for two Councillors to sit with the committee on Indian Affairs never came to a vote, and the Queen of the Pamunkeys demanded compensation for the former war in which her husband had been killed assisting the English as a precondition to furnishing warriors in this conflict, although ultimately the burgesses authorized an army of 1000 men. The recomposed House of Burgesses ultimately enacted a number of sweeping reforms, known as Bacon's Laws discussed below. However, by this time Bacon had escaped Jamestown, telling Berkeley that his own wife was ill, but soon placing himself at the head of a volunteer army in Henrico County

Henrico County , officially the County of Henrico, is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 334,389 making it the fifth-most populous county in Virginia. Henrico Coun ...

, where natives had renewed raids and killed 8 settlers, including wiping out families.Wertenbaker p. 26

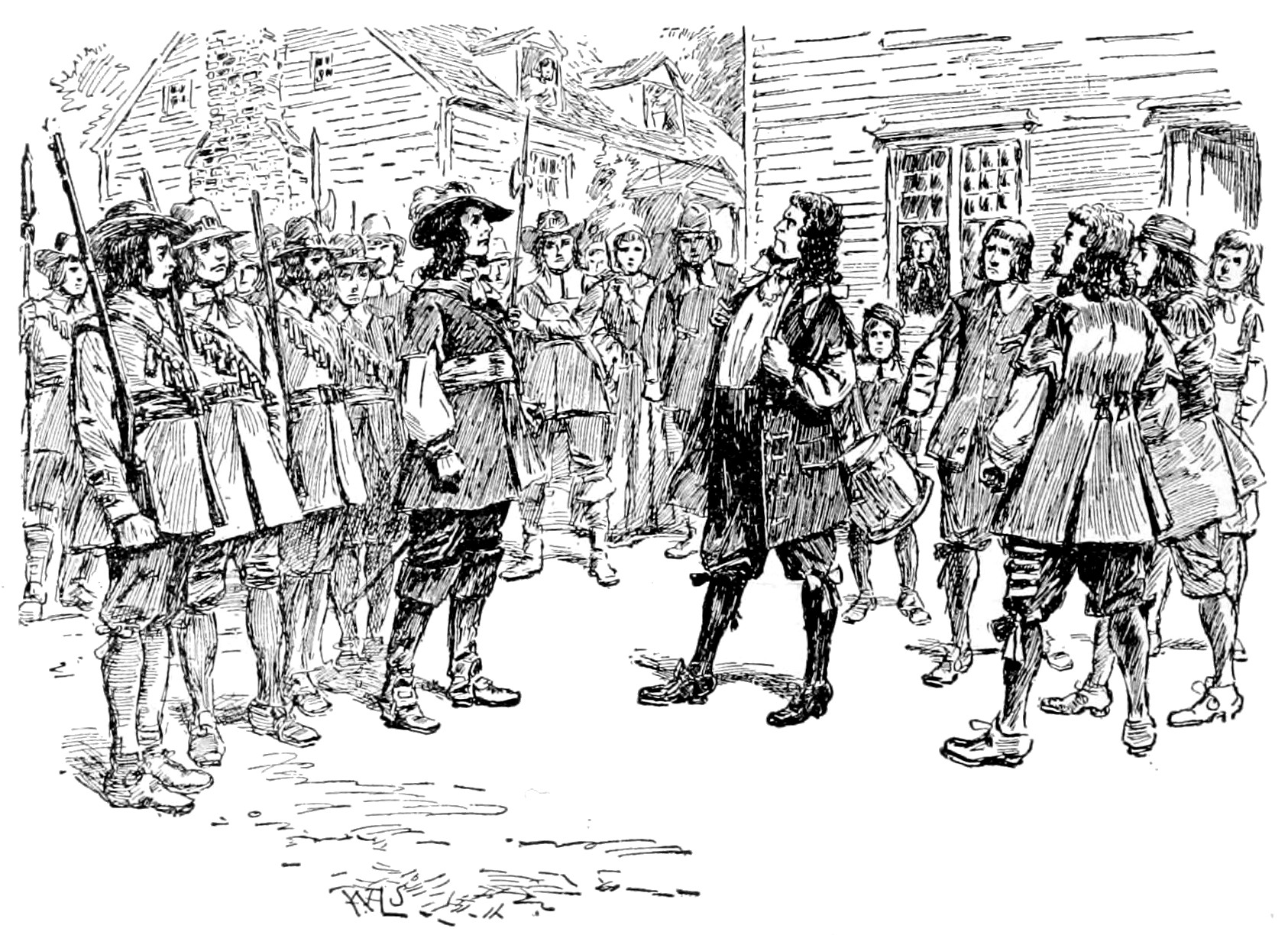

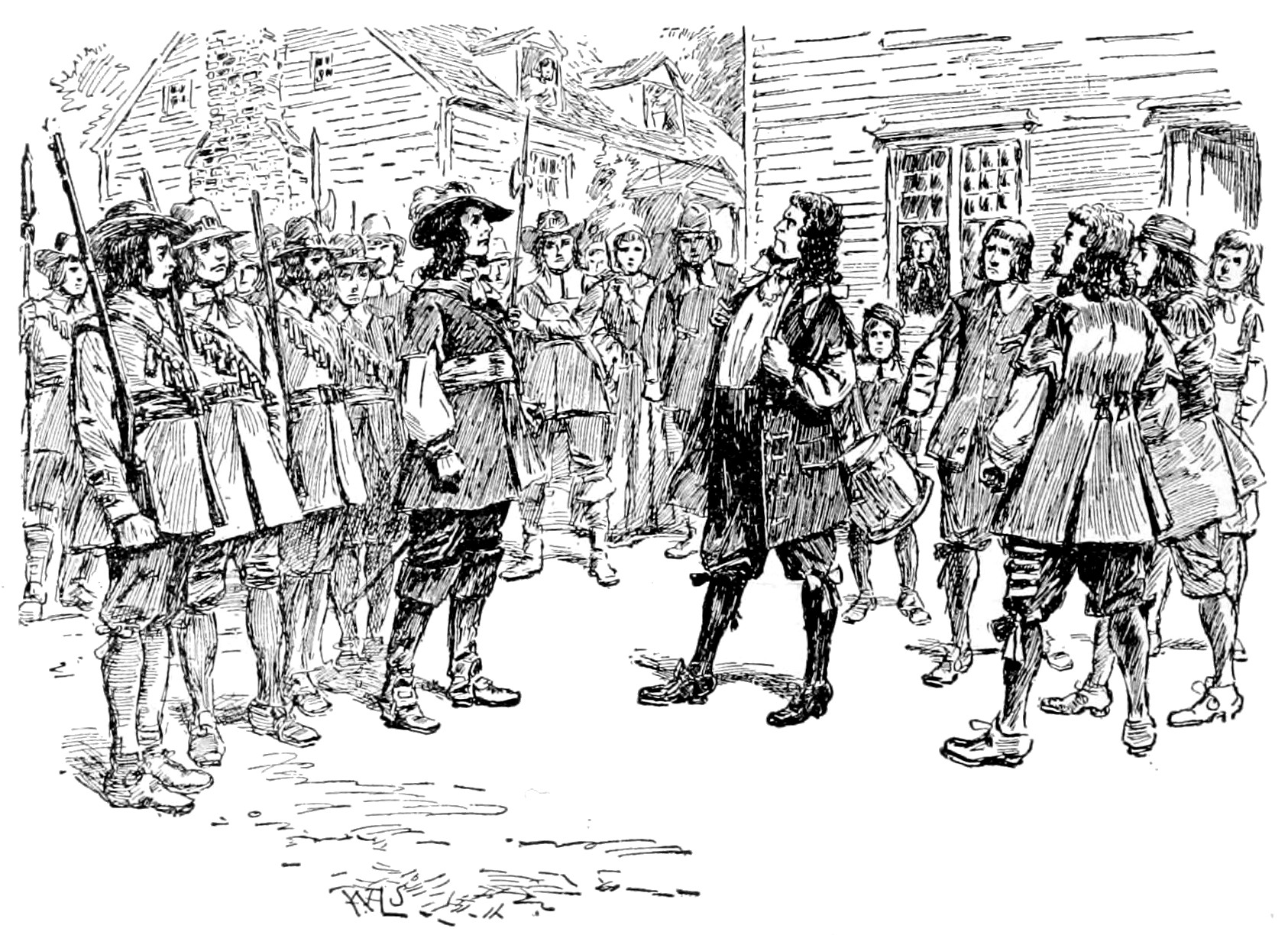

Bacon returned to Jamestown with hundreds of enraged followers demanding "no levies" (meaning no additional taxes nor military conscription). Bacon demanded a military commission to lead forces against the Indians, as well as blank commissions for his officers. Governor Berkeley, however, initially refused to yield to the pressure, rushing out to meet Bacon in the street and declaring him a traitor. When Bacon had his men take aim at Berkeley, he responded by "baring his breast" and told Bacon to shoot him. Seeing that the governor would not be moved, Bacon then had his men take aim at the burgesses viewing the street spectacle from the windows of nearby houses. When the burgesses invited Bacon into their Long Room, the governor yielded and signed the military commissions, as well as wrote the King justifying Bacon's conduct. The assembly in Bacon's absence had also rushed through "Bacon's Laws", possibly drafted by Lawrence and Drummond, or by Thomas Blayton (whom Edward Hill later called "Bacon's great engine" in the assembly). Although repealed by the burgesses in the 1677 session, they limited the governor's powers, set certain fees for governmental actions, made it illegal for one person to hold more than one important county office at one time (the offices being sheriff, clerk of court, surveyor and escheator) and restored suffrage to landless freemen (including in taxes levied by county courts and vestries).

Rival recruiting attempts and the "Declaration of the People"

In late July, Bacon completed preparations for his Indian campaign, including enlisting officers and armed bands from many counties, which were to meet at the falls of the James River. Bacon addressed seven hundred gathered horse and six hundred gathered foot troops, took the oath of allegiance and expected to march the next day, only to learn that Philip Ludwell and Robert Beverley were recruiting other troops on behalf of Governor Berkeley in Gloucester County to their rear, alleging that Bacon's commission was illegal because it had been procured by force, but the troops refused to gather for the governor upon learning they were to oppose the popular hero Bacon. On July 30, 1676, Bacon and his army issued the " Declaration of the People". The declaration criticized Berkeley's administration in detail. It leveled several accusations against Berkeley: # that "upon specious pretense of public works eraised great unjust taxes upon the commonality"; # that he advanced favorites to high public offices; # that he monopolized the beaver trade with the Native Americans; # that he was pro-Native American. Berkeley then followed Robert Beverley's advice and fled across Chesapeake Bay to Accomack County on Virginia's Eastern Shore. Chicheley promised to meet him shortly thereafter, but was captured. Bacon and his followers established a camp at Middle Plantation (modernWilliamsburg

Williamsburg may refer to:

Places

*Colonial Williamsburg, a living-history museum and private foundation in Virginia

*Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighborhood in New York City

*Williamsburg, former name of Kernville (former town), California

*Williams ...

) and issued a proclamation declaring Berkeley, Chicheley, Ludwell, Beverley and others traitors, as well as threatened to confiscate their estates unless they surrendered within four days. Bacon also summoned all the leading planters to a conference. Seventy assembled and 69 took three oaths: (1) that they would join with him against the Indians, (2) that they would arrest anyone trying to raise troops against him, and (3) (with demurrers) that they would oppose any English troops sent to Virginia until Bacon could plead his case before the King. Among the oath's signers were burgesses or councillors Thomas Swan Thomas Swan may refer to:

* Thomas Swan (company), a chemicals company in England

* Thomas Walter Swan (1877–1975), U.S. Court of Appeals judge

* Thomas Swan (abolitionist) (1795–1857), British abolitionist Baptist minister

See also

* Thom ...

, John Page, Philip Lightfoot and Thomas Ballard

Colonel Thomas Ballard (1630/31 – March 24, 1689/90) was a prominent Colony of Virginia, colonial Virginia landowner and politician who played a role in Bacon's Rebellion. He served on the Governor's Council 1670–79 and was List of Sp ...

. Meanwhile, Bacon's father, Thomas Bacon, was pleading with the King to pardon his son, presenting "The Virginians' Plea".

Bacon then led his army through upper Gloucester and Middlesex Counties against the Pamunkey, finding a village in the swamps and capturing 45 prisoners (although the queen of the Pamunkeys escaped) as well as stores of wampum, skins, fur and English goods. Meanwhile, on August 1, Bacon's followers Giles Bland and William Carver captured a ship 'Rebecca" commanded by Captain Larrimore and refitted her with guns, although two other ships escaped. Bland and Carver and 250 men with three ships then attempted to block the mouth of the James River, but ended up anchoring off Accomac, where Captain Larrimore sent a message to Governor Berkeley about serving with his crew under duress, so Philip Ludwell and two boats of soldiers sailed out and recaptured the ship. Berkeley then embarked 200 men on two ships and six or seven sloops and returned to the Western Sore, sailing up the James River toward Jamestown, where Bacon's garrison fled without firing a shot.

Burning of Jamestown, further raids, courts martial and Bacon's death

When Bacon's forces again reached Jamestown, it seemed impregnable, approachable only via a narrow isthmus defended by three heavy guns. Nonetheless, Bacon ordered a crude fortification constructed at the end of the isthmus, and when Berkeley's forces fired on the crude structure, sent out parties of horse troops to gather the wives of some of the governor's supporters. Thus, Elizabeth Page, Angelica Bray, Anna Ballard, Frances Thorpe and Elizabeth Bacon (wife of his senior cousin) were placed on the ramparts together with some Native American prisoners, to be endangered should firing resume. On September 15, some of Berkeley's troops sallied out, but without success, so Berkeley's Councillors advised abandoning the town. They spiked the guns, took stores aboard vessels and slipped down the river at night. Bacon's forces thus retook the town. However, Bacon also learned that his former follower,

When Bacon's forces again reached Jamestown, it seemed impregnable, approachable only via a narrow isthmus defended by three heavy guns. Nonetheless, Bacon ordered a crude fortification constructed at the end of the isthmus, and when Berkeley's forces fired on the crude structure, sent out parties of horse troops to gather the wives of some of the governor's supporters. Thus, Elizabeth Page, Angelica Bray, Anna Ballard, Frances Thorpe and Elizabeth Bacon (wife of his senior cousin) were placed on the ramparts together with some Native American prisoners, to be endangered should firing resume. On September 15, some of Berkeley's troops sallied out, but without success, so Berkeley's Councillors advised abandoning the town. They spiked the guns, took stores aboard vessels and slipped down the river at night. Bacon's forces thus retook the town. However, Bacon also learned that his former follower, Giles Brent

Giles may refer to:

People

* Giles (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Giles (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

* Saint Giles (650–710), Christian hermit saint

* Giles of Assisi (c. 1190–1 ...

had raised an army in the northern counties and was marching south to attack Bacon and his men. Thus, Bacon, Lawrence, Drummond and others decided to torch Jamestown, the colony's capital, on September 19.

After Bacon's followers torched the capital and left their encampment at Berkeley's Green Spring Plantation

Green Spring Plantation in James City County about west of Williamsburg, was the 17th century plantation of one of the most unpopular governors of Colonial Virginia in North America, Sir William Berkeley, and his wife, Frances Culpeper B ...

outside Jamestown, the main body traveled east to Yorktown. They then crossed the York River and encamped in Gloucester County at Warner Hall, home of the speaker of the House of Burgesses, Augustine Warner Jr. However, the Gloucester troops balked at further oaths. This disappointed Bacon, so he arrested Rev. James Wadding, who had tried to dissuade the people from subscribing. Bacon also set up courts martial to try some of this opponents, or exchange them for Carver and Bland, but only executed one deserter.

Bacon also sent Captain George Farlow (formerly one of Cromwell's men) and 40 soldiers to capture Governor Berkeley at the plantation of council member John Custis in Accomack County on Virginia's Eastern Shore, but the raid failed, and Farloe was captured and hanged. Nor was a manifesto to the people of the Eastern Shore effective. Thus, Bacon issued orders that the estates of the governor and his friends be ransacked to supply his army. Taking cattle, sheep, hogs, Indian corn and household furnishings, Bacon's soldiers seemed to plunder both friend and foe, eroding his support. Bacon made his final headquarters at the house of Major Thomas Pate, in Gloucester County a few miles east of West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

, but fell ill of dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

and after calling in Rev. Wadding for last rites, died on October 26, 1676. His body was never found; upon being exhumed on Berkeley's orders, the casket contained only stones.

Suppression

Bacon and his rebels never encountered a Crown force consisting of 1,000 English Army troops led by Colonel Herbert Jeffreys transported by aRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

squadron under the command of Thomas Larimore sent to aid Berkeley. Neither Lawrence nor Drummond had military experience, and Giles Bland who had such experience was already Berkeley's prisoner, having been captured along with Carver during the failed kidnapping attempt. Thus, the remaining rebels elected John Ingram, Bacon's second in command but a saddler by trade, as their leader. However, he faced daunting problems in feeding his men, as well as the militarily strategic need to cover hundreds of thousands of acres of land with many vulnerable areas.

The rebellion did not last long after that. Ingram kept his main force at the head of the York River, with small garrisons at strategic points—including Governor Berkeley's residence at Green Spring and Major Arthur Allen's across the James River (at what came to be called Bacon's Castle though Bacon had never lived there), as well as Colonel West's house near West Point, Councillor Bacon's house at King's Creek and Yorktown (both on the York River) as well as Col. John Washington's house in Westmoreland County to the north. Berkeley launched a series of successful amphibious attacks across the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

and defeated the small pockets of insurgents spread across Tidewater Virginia

Tidewater is a region in the Atlantic Plains of the United States located east of the Atlantic Seaboard fall line (the natural border where the tidewater meets with the Piedmont region) and north of the Deep South. The term "tidewater" can be ...

. Major Beverley captured Captain Thomas Hansford and his Yorktown garrison, then returned to capture Major Edmund Cheesemen and Capt. Thomas Wilford.

However, Berkeley's forces also suffered losses. A planned surprise raid on the York River garrison at King's Creek ended with the death of its leader, Capt. Hubert Farril. Major Lawrence Smith had gathered loyalists in Gloucester county, but when they faced Ingram's forces, Major Bristow offered single combat in the medieval style, and the loyalists' rank and file laid down their arms and went home. Another large force gathered in Middlesex County but dispersed after Ingram sent out Gregory Wakelett and a body of horse troops. Thus, Berkeley's plan to close in on Ingram from the south of the York River, while other loyalists attacked from the north and east failed miserably.

In November 1676, the Royal Navy arrived. Thomas Grantham, captain of the ship ''Concord'' cruised the York River, despite pleas from Lawrence about the people having been grievously oppressed and requests to remain neutral. Grantham tried to persuade Berkeley to use meekness, which Berkeley soon used to good effect, but insisted that the pardons not be allowed to Lawrence and Drummond. Grantham then went up the York River to the Pate house at West Point, and used cunning and force to disarm the rebels there. Ingram yielded the West Point garrison with 300 men, four great guns and many small arms, then Grantham tricked his way into the rebel garrison at John West's house with a barrel of brandy and promises of pardon. However, after surrendering the post with 3 cannon, 500 muskets and fowling pieces and 1000 pounds of bullets, and once they were safely in the hold, he turned the ship's guns on them and disarmed the rebels.Wertenbaker p. 50 Berkeley invited Ingram and Langston to dine with him on shipboard, after their surrender at Tindall's Point, after the men had toasted the King and governor, they were allowed to disperse. Then to secure the submission of Gregory Wakelett's cavalry, Berkeley offered not only a pardon, but part of the wampum Bacon's former men had taken from the Indians.

Lawrence, Whaley and three others fled westward, risking torture at the hands of natives rather than fall into the governor's control. They were last seen pushing through the snow on the extreme frontier, and may have died of hunger and exposure, or found refuge in some other colony. Drummond was found hiding in Chickahominy Swamp.

Aftermath

Although rebel forces were suppressed, the colony was in a deplorable condition, with many plantations deserted or plundered. The government lacked money, and the absence of labor had resulted in small harvests of both tobacco and grain. Nonetheless, at year's end, tobacco ships began to come in with supplies of clothing, cloth, medicines, and sundries.

Although rebel forces were suppressed, the colony was in a deplorable condition, with many plantations deserted or plundered. The government lacked money, and the absence of labor had resulted in small harvests of both tobacco and grain. Nonetheless, at year's end, tobacco ships began to come in with supplies of clothing, cloth, medicines, and sundries.

Trials and executions

Executions continued for several months. Berkeley acknowledged executing 13 rebels. While his headquarters remained on the Eastern Shore, Berkeley condemned many rebels and executed five. Hansford pleaded that he be shot as a soldier not hanged like a dog, and protested his loyalty as he stood on the scaffold. Major Cheeseman died in prison, though his wife pleaded that she be hung in his place. Farloe produced his military commission and was told that it authorized fighting only against Indians, not the Governor, and so was also executed, as were Carver, Wilford, and John Johnson. The 71-year-old governor Berkeley returned to the burned capital and his looted Green Spring home at the end of January 1677. His wife described theirGreen Spring Plantation

Green Spring Plantation in James City County about west of Williamsburg, was the 17th century plantation of one of the most unpopular governors of Colonial Virginia in North America, Sir William Berkeley, and his wife, Frances Culpeper B ...

in a letter to her cousin:

It looked like one of those the boys pull down atThomas Young, James Wilson ("Harris" per Berkeley), Henry Page and Thomas Hall were executed on January 12, 1677. Then William Drummond and John Baptista (the latter not mentioned by Berkeley) were tried at Middle Plantation (Williamsburg) not far from Green Spring and executed on January 20. James Crewes, William Cookson and John Digbie ("Darby" being named as a former servant in Berkeley's list) were tried at Jamestown and hanged on January 24.Wertenbaker p. 52 However, despite receiving orders to return to England, Berkeley delayed his departure for several months, during which he presided over additional trials, apparently disregarding the clemency suggested by the royal representatives. Bacon's wealthy landowning followers returned their loyalty to the Virginia government after Bacon's death. Some former rebels of lower classes were ordered to make public apologies, and many were fined or ordered to pay court costs. The childless, elderly Governor's seizing property of several (but not all) rebels for the colony provoked considerable unrest and dissatisfaction. However, whereas in the initial trials many of the accused were denied counsel, such were present in several of the later trials. Berkeley in particular grew displeased with his former King's Counsel, William Sherwood for defending former rebels. Former customs collector Giles Bland and Anthony Arnold were executed on March 8, then John Isles and Richard Pomfrey on March 15 and John Whitson and William Scarburgh on March 16. Scholars differ as to the number of men executed, although roughly double the number in Berkeley's report. One scholar counted 25 executionsJohn Harold Sprinkle, Jr., Loyalists and Baconians: the participants in Bacon's Rebellion, 1676–1677 (William & Mary 1992) available at W&M ScholarWorks another states 23 men were executed by hanging.Geiter, Mary K., William Arthur Speck,Shrovetide Shrovetide is the Christian liturgical period prior to the start of Lent that begins on Shrove Saturday and ends at the close of Shrove Tuesday. The season focuses on examination of conscience and repentance before the Lenten fast. It includes ..., and was almost as much to repair as if it had been new to build, and no sign that ever there had been a fence around it...

Colonial America: From Jamestown to Yorktown

', Macmillan, 2002, p. 63

Royal commission and Berkeley's death

Meanwhile, after an investigative committee returned its report to King Charles II, Berkeley was relieved of the governorship and recalled to England. According to one historian, "Because the tobacco trade generated a crown revenue of about £5–£10 per laboring man, King Charles II wanted no rebellion to distract the colonists from raising the crop." Charles II was reported to have commented, "That old fool has put to death more people in that naked country than I did here for the murder of my father." No record of the king's comments have been found, and the origin of the story appears to have been colonial legend that arose at least 30 years after the events. The king prided himself on the clemency he had shown to his father's enemies. Berkeley left his wife, Frances Berkeley, in Virginia and returned to England. She sent a letter to let him know that the current governor was making a bet that the king would refuse to receive him. However, William Berkeley died in July 1677, shortly after he landed in England.Resolution by Herbert Jeffreys

In November 1676, Herbert Jeffreys was appointed by Charles II as a lieutenant governor of Virginia colony and arrived in Virginia in February 1677. During Bacon's Rebellion, Jeffreys was commander-in-chief of the regiment of six warships carrying over 1,100 troops, tasked with quelling and pacifying the rebellion upon their arrival. He served as leader of a three-member commission (alongside Sir John Berry and Francis Moryson) to inquire into the causes of discontent and political strife in the colony. The commission published a report for the King titled ''"A True Narrative of the Rise, Progresse, and Cessation of the late Rebellion in Virginia,"'' which provided an official report and history of the insurrection.

On 27 April 1677, with the support of the King, Jeffreys assumed the role of acting colonial governor following Bacon's Rebellion, succeeding Berkeley. Shortly after Jeffreys took over as acting governor, Berkeley angrily remarked that Jeffreys had an "irresistible desire to rule this country" and that his action could not be justified. He wrote to Jeffreys, "I believe that the inhabitants of this Colony will quickly find a difference between your management and mine."

As acting governor, Jeffreys was responsible for appeasing the remaining factions of resistance and reforming the colonial government to be once more under direct

In November 1676, Herbert Jeffreys was appointed by Charles II as a lieutenant governor of Virginia colony and arrived in Virginia in February 1677. During Bacon's Rebellion, Jeffreys was commander-in-chief of the regiment of six warships carrying over 1,100 troops, tasked with quelling and pacifying the rebellion upon their arrival. He served as leader of a three-member commission (alongside Sir John Berry and Francis Moryson) to inquire into the causes of discontent and political strife in the colony. The commission published a report for the King titled ''"A True Narrative of the Rise, Progresse, and Cessation of the late Rebellion in Virginia,"'' which provided an official report and history of the insurrection.

On 27 April 1677, with the support of the King, Jeffreys assumed the role of acting colonial governor following Bacon's Rebellion, succeeding Berkeley. Shortly after Jeffreys took over as acting governor, Berkeley angrily remarked that Jeffreys had an "irresistible desire to rule this country" and that his action could not be justified. He wrote to Jeffreys, "I believe that the inhabitants of this Colony will quickly find a difference between your management and mine."

As acting governor, Jeffreys was responsible for appeasing the remaining factions of resistance and reforming the colonial government to be once more under direct Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, parti ...

control. Jeffreys presided over the Treaty of 1677, the formal peace treaty between the Crown and representatives from various Virginia Native American tribes that was signed on 28 May 1677. In October 1677, Jeffreys persuaded the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, and the first elected legislative assembly in the New World. It was established on July 30, ...

to pass an act of amnesty for all of the participants in Bacon's Rebellion, and levied fines against any citizen of the colony that called another a "traitor" or "rebel." Jeffreys led efforts to rebuild and restore the state house and colonial capital of Jamestown which had been burned and looted during the rebellion.

Historical disagreements

In order for the Virginia elite to maintain the loyalty of the common planters in order to avert future rebellions, one historian commented, they "needed to lead, rather than oppose, wars meant to dispossess and destroy frontier Indians." He elaborated that this bonded the elite to the common planter in wars against Indians, their common enemy, and enabled the elites to appease free whites with land. Taylor writes, "To give servants greater hope for the future, in 1705 the assembly revived the headright system by promising each freedman fifty acres of land, a promise that obliged the government to continue taking land from the Indians." Bacon promised his army tax breaks, predetermined wages, and freedom fromindenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

s, "so long as they should serve under his colors." Indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or ser ...

both black and white had joined the frontier rebellion. Seeing them united in a cause alarmed the ruling class. Historians believe the rebellion hastened the hardening of racial lines associated with slavery, as a way for planters and the colony to control some of the poor. For example, historian Eric Foner

Eric Foner (; born February 7, 1943) is an American historian. He writes extensively on American political history, the history of freedom, the early history of the Republican Party, African American biography, the American Civil War, Reconstr ...

writes, "The fear of civil war among whites frightened Virginia's ruling elite, who took steps to consolidate power and improve their image: for example, restoration of property qualifications for voting, reducing taxes, and adoption of a more aggressive American Indian policy." Some of these measures, by appeasing the poor white population, may have had the purpose of inhibiting any future unification with the enslaved black population.

Historiography

In 1676,Ann Cotton

Ann Lesley Cotton OBE (born 1950) is a Welsh entrepreneur and philanthropist who was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2006 Queen's New Year Honours List. The honour was in recognition of her services to education of youn ...

wrote a personal account of Bacon's Rebellion. Her account was in the form of a letter written in 1676 and published in its original form in 1804 in the '' Richmond Enquirer'' under the title, ''An account of our late troubles in Virginia''. The following year, the same paper published ''The Beginning, Progress, and Conclusion of Bacon's Rebellion'', which former participant Thomas Mathew wrote in 1704 (the year before his death), and which had been acquired for President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, who gave his former mentor George Wythe

George Wythe (; 1726 – June 8, 1806) was an American academic, scholar, and judge who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. The first of the seven Signing of the United States Declaration of Independence, signatories of the ...

permission to have it published.

Historians question whether the rebellion by Bacon against Berkeley in 1676 had any lasting significance for the more-successful American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

a century later. The most idolizing portrait of Bacon is found in ''Torchbearer of the Revolution'' (1940) by Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker, which one scholar in 2011 called "one of the worst books on Virginia that a reputable scholarly historian ever published." The central area of debate is Bacon's controversial character and complex disposition, as illustrated by Wilcomb E. Washburn's ''The Governor and the Rebel'' (1957). Rather than singing Bacon's praises and chastising Berkeley's tyranny, Washburn found the roots of the rebellion in the colonists' intolerable demand to "authorize the slaughter and dispossession of the innocent as well as the guilty."

More nuanced approaches on Berkeley's supposed tyranny or mismanagement entertained specialist historians throughout the middle of the twentieth century, leading to a diversification of factors responsible for Virginia's contemporary instability. Wesley Frank Craven in the 1968 publication, ''The Colonies in Transition'', argues that Berkeley's greatest failings took place during the revolt, near the end of his life. Bernard Bailyn

Bernard Bailyn (September 10, 1922 – August 7, 2020) was an American historian, author, and academic specializing in U.S. Colonial and Revolutionary-era History. He was a professor at Harvard University from 1953. Bailyn won the Pulitzer Pr ...

pushed the novel thesis that it was a question of access to resources, a failure to fully transplant Old World society to New.

Edmund S. Morgan

Edmund Sears Morgan (January 17, 1916 – July 8, 2013) was an American historian and an authority on early American history. He was the Sterling Professor of History at Yale University, where he taught from 1955 to 1986. He specialized in Americ ...

's 1975 classic, '' American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia'', connected the calamity of Bacon's Rebellion, namely the potential for lower-class revolt, with the colony's transition over to slavery, saying, "But for those with eyes to see, there was an obvious lesson in the rebellion. Resentment of an alien race might be more powerful than resentment of an upper class. Virginians did not immediately grasp it. It would sink in as time went on."

James Rice's 2012 narrative, ''Tales from a Revolution: Bacon's Rebellion and the Transformation of Early America'', whose emphasis on Bacon's flaws echoes ''The Governor and the Rebel'', integrates the rebellion into a larger story emphasizing the actions of multiple Native Americans, as well as placing it in the context of politics in Europe. In this telling, the climax of Bacon's Rebellion comes with the "Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

" of 1688/89.

Legacy

According to theHistoric Jamestown

Historic Jamestown is the cultural heritage site that was the location of the 1607 James Fort and the later 17th-century town of Jamestown in America. It is located on Jamestown Island, on the James River at Jamestown, Virginia, and opera ...

e website, "For many years, historians considered the Virginia Rebellion of 1676 to be the first stirring of revolutionary sentiment in orth Orth can refer to:

Places

* Orth, Minnesota, an unincorporated community in Nore Township, Minnesota, United States

* Orth an der Donau, a town in Gänserndorf, Lower Austria, Austria

* Orth House, a historic house in Winnetka, Illinois, United ...

America, which culminated in the American Revolution almost exactly one hundred years later. However, in the past few decades, based on findings from a more distant viewpoint, historians have come to understand Bacon's Rebellion as a power struggle between two stubborn, selfish leaders rather than a glorious fight against tyranny."

Nonetheless, many in the early United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, including Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, saw Bacon as a patriot and believed that Bacon's Rebellion truly was a prelude to the later American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

against the control of the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

. This understanding of the conflict was reflected in 20th-century commemorations, including a memorial window in Colonial Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg is a living-history museum and private foundation presenting a part of the historic district in Williamsburg, Virginia. Its historic area includes several hundred restored or recreated buildings from the 18th century, wh ...

and a prominent tablet in the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two houses of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-numbe ...

chamber of the State Capitol

A capitol, or seat of government, is the building or complex of buildings from which a government such as that of a U.S. state, the District of Columbia, or the organized territories of the United States, exercises its authority. Although m ...

in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

, which recalls Bacon as "A great Patriot Leader of the Virginia People who died while defending their rights October 26, 1676." Subsequent to the rebellion, the Virginia colonial legislature enacted the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705

The Virginia Slave Codes of 1705 (formally entitled An act concerning Servants and Slaves), were a series of laws enacted by the Colony of Virginia's House of Burgesses in 1705 regulating the interactions between slaves and citizens of the crow ...

, which created several strict laws upon people of African background. Additionally, the codes were intended to socially segregate the white and black races.

Use of jimsonweed

Jimsonweed is adeliriant

Deliriants are a subclass of hallucinogen. The term was coined in the early 1980s to distinguish these drugs from psychedelics such as LSD and dissociatives such as ketamine, due to their primary effect of causing delirium, as opposed to th ...

plant that was first documented by a Virginian colonist named Robert Beverly. Robert Beverley reported, in his 1705 book on the history of Virginia, that some soldiers who had been dispatched to Jamestown to quell Bacon's Rebellion gathered and ate leaves of ''Datura stramonium

''Datura stramonium'', known by the common names thornapple, jimsonweed (jimson weed), or devil's trumpet, is a poisonous flowering plant in the ''Datureae, Daturae'' Tribe (botany), tribe of the nightshade family Solanaceae. Its likely origi ...

'' and spent eleven days acting in bizarre and foolish ways before recovering. After recovery from the plant the soldiers claimed to not remember anything from the past 11 days. This led to the plant being known as Jamestown weed, and later jimsonweed.

Although described as a "cooler" by Robert Beverley, effects can be close to schizophrenia and dissociative disorder, explaining why soldiers acted irrationally, or "went crazy" for days.

See also

* Cockacoeske, Pamunkey chief *Queen Ann (Pamunkey chief)

Queen Ann (–1723) appears in Virginia records between 1706 and 1718 as ruler of the Pamunkey tribe of Virginia. Ann continued her predecessors' efforts to keep peace with the colony of Virginia.

She became the leader of her tribe after Quee ...

* Bacon's Castle

* Culpeper's Rebellion

References

Further reading

* Allen, Theodore W.The Invention of the White Race, Vol. 2: The Origins of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America.

' London: Verso (1997). * Billings, Warren M. "The Causes of Bacon's Rebellion: Some Suggestions," ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography,'' 1970, Vol. 78 Issue 4, pp. 409–435 * Cave, Alfred A. "Lethal Encounters: Englishmen and Indians in Colonial Virginia" (University of Nebraska Press, 2011) pp. 147–165 * Cullen, Joseph P. "Bacon's Rebellion," ''American History Illustrated,'' Dec 1968, Vol. 3 Issue 8, p. 4 ff., popular account. * Frantz, John B. ed. ''Bacon's Rebellion: Prologue to the Revolution?'' (1969), excerpts from primary and secondary source

online

* Morgan, Edmund S. (1975) ''American slavery, American freedom: the ordeal of colonial Virginia'' (1975) pp. 250–270. * Rice, James D. "Bacon's Rebellion in Indian Country," ''Journal of American History,'' vol. 101, no. 3 (Dec. 2014), pp. 726–750. * Tarter, Brent. "Bacon's Rebellion, the Grievances of the People, and the Political Culture of Seventeenth-Century Virginia," ''Virginia Magazine of History & Biography'' (2011) 119#1 pp 1–41. * * * Wertenbaker, Thomas Jefferson. ''Torchbearer of the Revolution: The Story of Bacon's Rebellion and its Leader'' (

Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financial ...

, 1940)

* Washburn, Wilcomb E. ''The Governor and the Rebel: A History of Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia'' (University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1957), a standard scholarly historyPrimary sources

* Wiseman, Samuel. ''Book of Record: The Official Account of Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia, 1676–1677'' (2006)External links

* *Bacon's Rebellion

at ''

Encyclopedia Virginia Virginia Humanities (VH), formerly the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, is a humanities council whose stated mission is to develop the civic, cultural, and intellectual life of the Commonwealth of Virginia by creating learning opportunities f ...

''

{{Authority control

Conflicts in 1676

1676 in the Thirteen Colonies

Anti-Indigenous racism in Virginia

Rebellions against the British Empire

Colony of Virginia

Military history of the Thirteen Colonies

Colonial American and Indian wars

Native American history of Virginia

17th-century rebellions

1676 in the Colony of Virginia

Jamestown, Virginia

Slave rebellions in North America

Events that led to courts-martial