Anglo-Dutch Wars on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Anglo–Dutch Wars ( nl, Engels–Nederlandse Oorlogen) were a series of conflicts mainly fought between the

In 1648 the United Provinces concluded the Peace of Münster with Spain. Due to the division of powers in the

In 1648 the United Provinces concluded the Peace of Münster with Spain. Due to the division of powers in the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

and England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

(later Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

) from mid-17th to late 18th century. The first three wars occurred in the second half of the 17th century over trade and overseas colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

, while the fourth was fought a century later. Almost all the battles were naval engagements.

The English were successful in the first, while the Dutch were successful in the second and third clashes. However, by the time of the fourth war, the British Royal Navy had become the most powerful maritime force in the world.

There would be more battles in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, mainly won by the British, but these are generally considered to be separate conflicts.

Background

The English and the Dutch were both participants in the 16th-century European religious conflicts between the CatholicHabsburg Dynasty

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

and the opposing Protestant states. At the same time, as the Age of Exploration

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafari ...

dawned, the Dutch and English both sought profits overseas in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

.

Dutch Republic

In the early 1600s, the Dutch, while continuing to fight theEighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Refo ...

with the Catholic Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

, also began to carry out long-distance exploration by sea. The Dutch innovation in the trading of shares in a joint-stock company

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's capital stock, stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their share (finance), shares (certificates ...

allowed them to finance expeditions with stock subscriptions sold in the United Provinces and in London. They founded colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

in North America, India, and Indonesia (the Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

). They also enjoyed continued success in privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

ing – in 1628 Admiral Piet Heyn

Piet Pieterszoon Hein (25 November 1577 – 18 June 1629) was a Dutch admiral and privateer for the Dutch Republic during the Eighty Years' War. Hein was the first and the last to capture a large part of a Spanish treasure fleet which tra ...

became the only commander to successfully capture a large Spanish treasure fleet

The Spanish treasure fleet, or West Indies Fleet ( es, Flota de Indias, also called silver fleet or plate fleet; from the es, label=Spanish, plata meaning "silver"), was a convoy system of sea routes organized by the Spanish Empire from 1566 to ...

. With the many long voyages by Dutch East India

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock co ...

men, their society built an officer class and institutional knowledge that would later be replicated in England, principally by the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

.

By the middle of the 17th century, the Dutch joined the Portuguese as the main European traders in Asia. This coincided with the enormous growth of the Dutch merchant fleet, made possible by the cheap mass production of the fluyt

A fluyt (archaic Dutch: ''fluijt'' "flute"; ) is a Dutch type of sailing vessel originally designed by the shipwrights of Hoorn as a dedicated cargo vessel. Originating in the Dutch Republic in the 16th century, the vessel was designed to facilit ...

sailing ship types. Soon the Dutch had one of Europe's largest mercantile fleets, with more merchant ships than all other nations combined, and possessed a dominant position in the Baltic trade

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

.

In 1648 the United Provinces concluded the Peace of Münster with Spain. Due to the division of powers in the

In 1648 the United Provinces concluded the Peace of Münster with Spain. Due to the division of powers in the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

, the army and navy were the main base of power of the Stadtholder

In the Low Countries, ''stadtholder'' ( nl, stadhouder ) was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and H ...

, although the budget allocated to them was set by the States General The word States-General, or Estates-General, may refer to:

Currently in use

* Estates-General on the Situation and Future of the French Language in Quebec, the name of a commission set up by the government of Quebec on June 29, 2000

* States Gener ...

. With the arrival of peace, the States General decided to decommission most of the Dutch military. This led to conflict between the major Dutch cities and the new Stadtholder, William II of Orange

William II (27 May 1626 – 6 November 1650) was sovereign Prince of Orange and Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, Overijssel and Groningen in the United Provinces of the Netherlands from 14 March 1647 until his death three ...

, bringing the Republic to the brink of civil war. The Stadtholder's unexpected death in 1650 only added to the political tensions.

England

Tudor

In the 16th centuryElizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

built up her navy in order to carry out long-range "privateering" or piracy missions against the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

's global interests, exemplified by the attacks by Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (t ...

on Spanish merchant shipping and its harbours. Partly to provide a pretext for ongoing hostilities against Spain, Elizabeth assisted the Dutch Revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) (Historiography of the Eighty Years' War#Name and periodisation, c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and t ...

(1581) against the Kingdom of Spain by signing the Treaty of Nonsuch

The Treaty of Nonsuch was signed on 10 August 1585 by Elizabeth I of England and the Dutch rebels fighting against Spanish rule. It was the first international treaty signed by what would become the Dutch Republic. It was signed at Nonsuch Palac ...

in 1585 with the new Dutch state of the United Provinces.

Stuart

After the death of Elizabeth, Anglo-Spanish relations began to improve under James the First, and the peace of 1604 ended most privateering actions (until the outbreak of the next Anglo-Spanish War during theThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

). Underfunding then led to neglect of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

.

Later, Catholic sympathiser Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until Execution of Charles I, his execution in 1649. He was born into the House of Stuart as the second son of King James VI of ...

made a number of secret agreements with Spain, directed against Dutch sea power. He also embarked on a major programme of naval reconstruction, enforcing ship money

Ship money was a tax of medieval origin levied intermittently in the Kingdom of England until the middle of the 17th century. Assessed typically on the inhabitants of coastal areas of England, it was one of several taxes that English monarchs co ...

to finance the building of such prestige vessels as . But fearful of endangering his relations with the powerful Dutch stadtholder

In the Low Countries, ''stadtholder'' ( nl, stadhouder ) was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and H ...

Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange

Frederick Henry ( nl, Frederik Hendrik; 29 January 1584 – 14 March 1647) was the sovereign prince of Orange and stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from 1625 until his death in 1647. In the last ...

, his assistance to Spain was limited in practice to allowing Habsburg troops on their way to Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.Downs anchorage off the town of

After some inconclusive minor fights the English were successful in the first major battle,

After some inconclusive minor fights the English were successful in the first major battle,

Soon the English navy was rebuilt. After the embarrassing events in the previous war, English public opinion was unenthusiastic about starting a new one. However, as he was bound by the secret

Soon the English navy was rebuilt. After the embarrassing events in the previous war, English public opinion was unenthusiastic about starting a new one. However, as he was bound by the secret

By 1707 the formal union between the Kingdoms of England and Scotland had taken place with the new and more powerful

By 1707 the formal union between the Kingdoms of England and Scotland had taken place with the new and more powerful

online

the fullest military history. * Kennedy, Paul M. ''The rise and fall of British naval mastery'' (1983) pp. 47–74. * Konstam, Angus, and Tony Bryan. ''Warships of the Anglo-Dutch Wars 1652–74'' (2011

excerpt and text search

* Levy, Jack S., and Salvatore Ali. "From commercial competition to strategic rivalry to war: The evolution of the Anglo-Dutch rivalry, 1609–52." in ''The dynamics of enduring rivalries'' (1998) pp. 29–63. * Messenger, Charles, ed. ''Reader's Guide to Military History'' (Routledge, 2013). pp. 19–21. * Ogg, David. ''England in the Reign of Charles II'' (2nd ed. 1936), pp. 283–321 (Second War); pp. 357–388. (Third War), Military emphasis. * Palmer, M. A. J. "The 'Military Revolution' Afloat: The Era of the Anglo-Dutch Wars and the Transition to Modern Warfare at Sea." ''War in history'' 4.2 (1997): pp. 123–149. * Padfeld, Peter. ''Tides of Empire: Decisive Naval Campaigns in the Rise of the West. Vol. 2 1654–1763.'' (1982). * Pincus, Steven C.A. ''Protestantism and Patriotism: Ideologies and the making of English foreign policy, 1650–1668'' (Cambridge UP, 2002). * Rommelse, Gijs "Prizes and Profits: Dutch Maritime Trade during the Second Anglo-Dutch War," ''International Journal of Maritime History'' (2007) 19#2 pp. 139–159. * Rommelse, Gijs. "The role of mercantilism in Anglo-Dutch political relations, 1650–74." ''Economic History Review'' 63#3 (2010) pp. 591–611.

National Maritime Museum

London. * Dutch

'The Seven Provinces'

is being rebuilt in the Dutch town of

Deal

A deal, or deals may refer to:

Places United States

* Deal, New Jersey, a borough

* Deal, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* Deal Lake, New Jersey

Elsewhere

* Deal Island (Tasmania), Australia

* Deal, Kent, a town in England

* Deal, ...

in Kent, Charles chose not to protect it against a Dutch attack; the resulting Battle of the Downs

The Battle of the Downs took place on 21 October 1639 (New Style), during the Eighty Years' War. A Spanish fleet, commanded by Admiral Antonio de Oquendo, was decisively defeated by a Dutch force under Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp. Vict ...

undermined both Spanish sea power and Charles's reputation in Spain.

Meanwhile, in the New World, naval forces from the Dutch New Netherlands

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva P ...

and the English Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

contested much of America's north-eastern seaboard.

Cromwell

The outbreak of theEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

in 1642 began a period in which England's naval position was severely weakened. Its navy was internally divided, though its officers tended to favour the parliamentary side; after the execution by public beheading of King Charles in 1649, however, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

was able to unite his country into the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

. He then revamped the navy by expanding the number of ships, promoting officers on merit rather than family connections, and cracking down on embezzlement by suppliers and dockyard staff, thereby positioning England to mount a global challenge to Dutch trade dominance.

The mood in England grew increasingly belligerent towards the Dutch. This partly stemmed from old perceived slights: the Dutch were considered to have shown themselves ungrateful for the aid they had received against the Spanish by growing stronger than their former English protectors; they caught most of the herring off the English east coast; they had driven the English out of the East Indies; and they vociferously appealed to the principle of free trade to circumvent taxation in the English colonies. There were also new points of conflict: with the decline of Spanish power at the end of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

in 1648, the colonial possessions of the Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the l ...

(already in the midst of Portuguese Restoration War

The Portuguese Restoration War ( pt, Guerra da Restauração) was the war between History of Portugal (1640–1777), Portugal and Habsburg Spain, Spain that began with the Portuguese revolution of 1640 and ended with the Treaty of Lisbon (1668), ...

) and perhaps even those of the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

itself were up for grabs.

Cromwell feared the influence of both the Orangist faction at home and English royalists exiled to the Republic; the Stadtholders had supported the Stuart monarchs—William II of Orange had married the daughter of Charles I of England in 1641—and they abhorred the trial and execution of Charles I.

Early in 1651 Cromwell tried to ease tensions by sending a delegation to The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

proposing that the Dutch Republic join the Commonwealth and assist the English in conquering most of Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' Spanish Empire, imperial era between 15th century, 15th ...

for its extremely valuable resources. This thinly-veiled attempt to end Dutch sovereignty by drawing it into a lopsided alliance with England in fact led to war: the ruling peace faction in the States of Holland The States of Holland and West Frisia ( nl, Staten van Holland en West-Friesland) were the representation of the two Estates (''standen'') to the court of the Count of Holland. After the United Provinces were formed — and there no longer was a c ...

was unable to formulate an answer to this unexpected offer and the pro-Stuart Orangists incited mobs to harass Cromwell's envoys. When the delegation returned home, the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

decided to pursue a policy of confrontation.

Wars

First war: 1652–1654

As a result of Cromwell's ambitious programme of naval expansion, at a time when the Dutch admiralty was selling off many of its own warships, the British came to possess a greater number of larger and more powerful purpose-built warships than did their rivals across the North Sea. However, the Dutch had many more cargo ships, together with lower freight rates, better financing and a wider range of manufactured goods to sell – although Dutch ships were blocked by the Spanish from operations in most of southern Europe, giving the English an advantage there. To protect its position in North America, in October 1651 the English Parliament passed the first of theNavigation Acts

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a long series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce between other countries and with its own colonies. The ...

, which mandated that all goods imported into England must be carried by English ships or vessels from the exporting countries, thus excluding (mostly Dutch) middlemen. This typical mercantilist

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduce ...

measure as such did not hurt the Dutch much as the English trade was relatively unimportant to them, but it was used by the many pirates operating from British territory as an ideal pretext to legally take any Dutch ship they encountered.

The Dutch responded to the growing intimidation by enlisting large numbers of armed merchantmen into their navy. The English, trying to revive an ancient right they perceived they had to be recognised as the 'lords of the seas', demanded that other ships strike their flags in salute to their ships, even in foreign ports. On 29 May 1652, Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp

Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp (also written as ''Maerten Tromp''; 23 April 1598 – 31 July 1653) was a Dutch army general and admiral in the Dutch navy.

Son of a ship's captain, Tromp spent much of his childhood at sea, including being capture ...

refused to show the respectful haste expected in lowering his flag to salute an encountered English fleet. This resulted in a skirmish, the Battle of Dover, after which the Commonwealth declared war on 10 July.

After some inconclusive minor fights the English were successful in the first major battle,

After some inconclusive minor fights the English were successful in the first major battle, General at Sea

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED On ...

Robert Blake Robert Blake may refer to:

Sportspeople

* Bob Blake (American football) (1885–1962), American football player

* Robbie Blake (born 1976), English footballer

* Bob Blake (ice hockey) (1914–2008), American ice hockey player

* Rob Blake (born 19 ...

defeating the Dutch Vice-Admiral Witte de With

Witte Corneliszoon de With (28 March 1599 – 8 November 1658) was a Dutch naval officer. He is noted for planning and participating in a number of naval battles during the Eighty Years War and the First Anglo-Dutch war.

Early life and chil ...

in the Battle of the Kentish Knock

The Battle of the Kentish Knock (or the Battle of the Zealand Approaches) was a naval battle between the fleets of the Dutch Republic and England, fought on 28 September 1652 (8 October Gregorian calendar), during the First Anglo-Dutch War near ...

in October 1652. Believing that the war was all but over, the English divided their forces and in December were routed by the fleet of Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp at the Battle of Dungeness

The naval Battle of Dungeness took place on 30 November 1652 (10 December in the Gregorian calendar) during the First Anglo-Dutch War near the cape of Dungeness in Kent.

Background

In September 1652 the government of the Commonwealth of En ...

in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

.

The Dutch were also victorious in March 1653, at the Battle of Leghorn

The naval Battle of Leghorn took place on 4 March 1653 (14 March Gregorian calendar),

during the First Anglo-Dutch War, near Leghorn (Livorno), Italy. It was a victory of a Dutch squadron under Commodore Johan van Galen over an English squadro ...

near Italy and had gained effective control of both the Mediterranean and the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. Blake, recovering from an injury, rethought, together with George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

, the whole system of naval tactics, and after the winter of 1653 used the line of battle

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

, first to drive the Dutch navy out of the English Channel in the Battle of Portland

The naval Battle of Portland, or Three Days' Battle took place during 18–20 February 1653 (28 February – 2 March 1653 (Gregorian calendar)), during the First Anglo-Dutch War, when the fleet of the Commonwealth of England under General at ...

and then out of the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

in the Battle of the Gabbard

The naval Battle of the Gabbard, also known as the Battle of Gabbard Bank, the Battle of the North Foreland or the Second Battle of Nieuwpoort took place on 2–3 June 1653 (12–13 June 1653 Gregorian calendar). during the First Anglo-Dutch War ...

. The Dutch were unable to effectively resist as the States General of the Netherlands

The States General of the Netherlands ( nl, Staten-Generaal ) is the supreme bicameral legislature of the Netherlands consisting of the Senate () and the House of Representatives (). Both chambers meet at the Binnenhof in The Hague.

The States ...

had not in time heeded the warnings of their admirals that much larger warships were needed.

In the final Battle of Scheveningen

The Battle of Scheveningen (also known as the Battle of Ter Heijde) was the final naval battle of the First Anglo-Dutch War. It took place on 31 July 1653 (10 August on the Gregorian calendar), between the fleets of the Commonwealth of Englan ...

on 10 August 1653, Tromp was killed, a blow to Dutch morale, but the English had to end their blockade of the Dutch coast. As both nations were by now exhausted and Cromwell had dissolved the warlike Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"Rump" n ...

, ongoing peace negotiations could be brought to fruition, albeit after many months of slow diplomatic exchanges.

The war ended on 5 April 1654, with the signing of the Treaty of Westminster (ratified by the States General on 8 May), but the commercial rivalry was not resolved, the English having failed to replace the Dutch as the world's dominant trade nation. The treaty contained a secret annex, the Act of Seclusion

The Act of Seclusion was an Act of the States of Holland, required by a secret annex in the Treaty of Westminster (1654) between the United Provinces and the Commonwealth of England in which William III, Prince of Orange, was excluded from the ...

, forbidding the infant Prince William III of Orange from becoming stadtholder of the province of Holland, which would prove to be a future cause of discontent. In 1653 the Dutch had started a major naval expansion programme, building sixty larger vessels, partly closing the qualitative gap with the English fleet. Cromwell, having started the war against Spain without Dutch help, during his rule avoided a new conflict with the Republic, even though the Dutch in the same period defeated his Portuguese and Swedish allies.

Second war: 1665–1667

After theEnglish Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to be ...

in 1660, Charles II tried through diplomatic means to make his nephew, Prince William III of Orange, stadtholder of the Republic. At the same time, Charles promoted a series of anti-Dutch mercantilist policies, which led to a surge of jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inte ...

in England, the country being, as Samuel Pepys put it, "mad for war".

English merchants and chartered companies—such as the East India Company, the Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa, and the Levant Company—calculated that global economic primacy could now be wrestled from the Dutch. They reckoned that a combination of naval battles and irregular privateering missions would cripple the Dutch Republic and force the States General to agree to a favourable peace. The plan was for English ships to be replenished, and sailors paid, with booty seized from captured Dutch merchant vessels returning from overseas.

In 1665 many Dutch ships were captured, and Dutch trade and industry were hurt. The English achieved several victories in battle, such as taking the Dutch colony of New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

(present day New York) by Charles' brother, the future James II; but there were also Dutch victories, such as the capture of the English flagship ''Prince Royal'' during the Four Days Battle

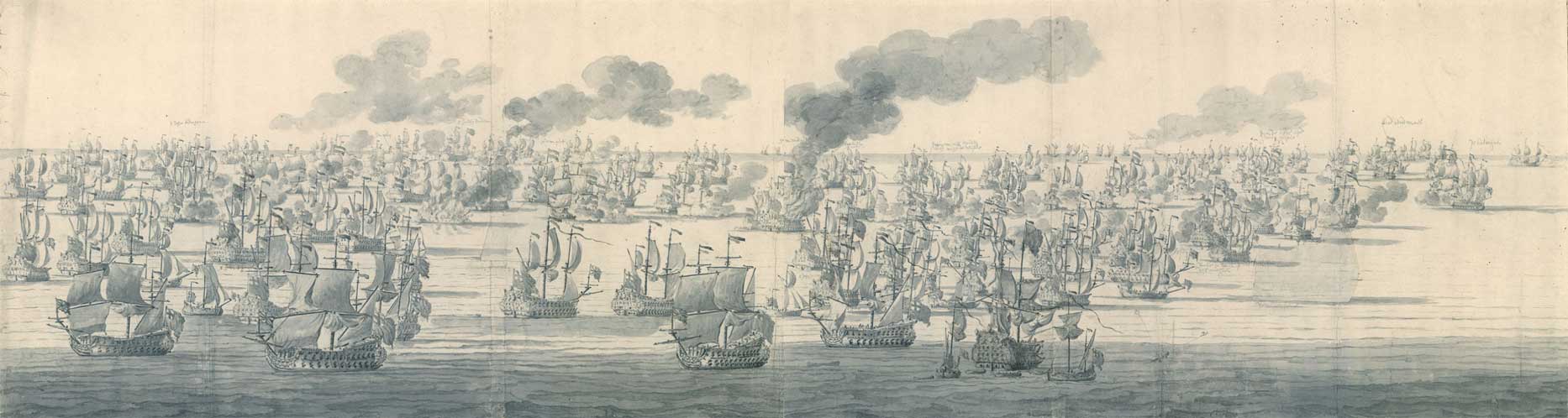

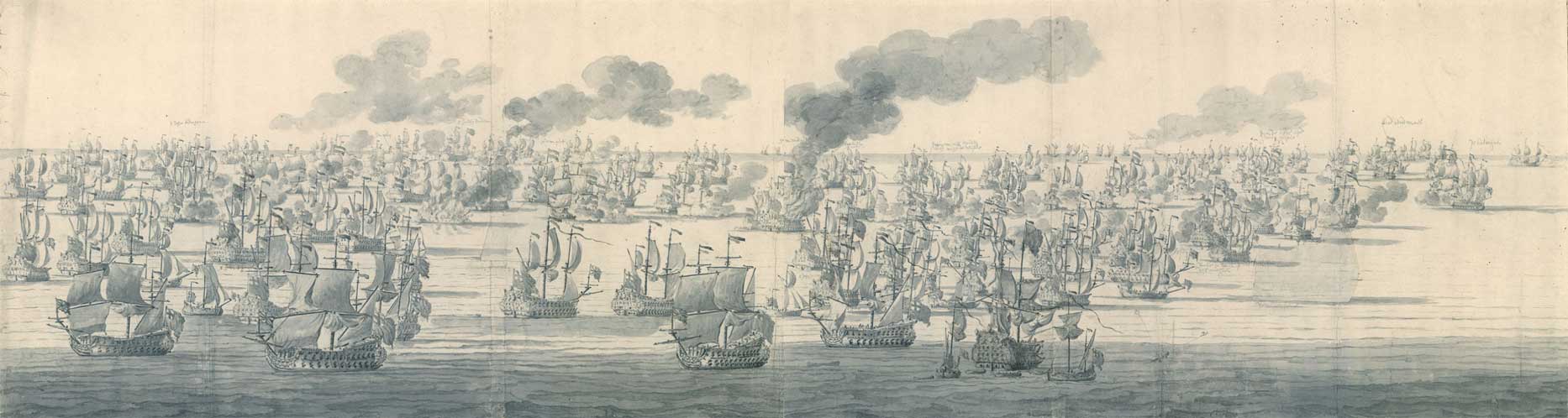

The Four Days' Battle, also known as the Four Days' Fight in some English sources and as Vierdaagse Zeeslag in Dutch, was a naval battle of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Fought from 1 June to 4 June 1666 in the Julian or Old Style calendar that w ...

—the subject of a famous painting by Willem van de Velde

Willem van de Velde the Elder (1610/11 – 13 December 1693) was a Dutch Golden Age seascape painter, who produced many precise drawings of ships and ink paintings of fleets, but later learned to use oil paints like his son.

Biography

Wi ...

.

Dutch maritime trade recovered from 1666, while the English war effort and her economy suffered when the country was ravaged by plague and much of the trading heart of the capital was burnt to the ground by the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

(which was generally interpreted in the Dutch Republic as divine retribution for Holmes's Bonfire

Holmes's Bonfire was a raid on the Vlie estuary in the Netherlands, executed by the English Fleet during the Second Anglo-Dutch War on 19 and 20 August 1666 New Style (9 and 10 August Old Style). The attack, named after the commander of the land ...

).

A surprise attack in June 1667, the Raid on the Medway

The Raid on the Medway, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War in June 1667, was a successful attack conducted by the Dutch navy on English warships laid up in the fleet anchorages off Chatham Dockyard and Gillingham in the county of Kent. At t ...

, on the English fleet in its home port arguably won the war for the Dutch; it is considered to be one of the most humiliating defeats in British military history. A flotilla of ships led by Admiral de Ruyter sailed up the Thames Estuary, broke through the defences guarding Chatham Harbour, set fire to ships of the English fleet moored there, and towed away and the Royal Charles

''Royal Charles'' was an 80-gun first-rate three-decker ship of the line of the English Navy. She was built by Peter Pett and launched at Woolwich Dockyard in 1655, for the navy of the Commonwealth of England. She was originally called ''Na ...

, the pride of the English fleet. Also in June 1667, the Dutch sailed a vessel from New Amsterdam into what is now Hampton Roads, Virginia, destroying a British ship in the harbour and attacking its fort.

The hammerblow at Chatham had a major psychological impact throughout England. This, together with the cost of the war and the extravagant spending of Charles's court, produced a rebellious atmosphere in London. Charles ordered the English envoys at Breda to sign a peace quickly with the Dutch, as he feared an open revolt against him.

Third war: 1672–1674

Soon the English navy was rebuilt. After the embarrassing events in the previous war, English public opinion was unenthusiastic about starting a new one. However, as he was bound by the secret

Soon the English navy was rebuilt. After the embarrassing events in the previous war, English public opinion was unenthusiastic about starting a new one. However, as he was bound by the secret Treaty of Dover

The Treaty of Dover, also known as the Secret Treaty of Dover, was a treaty between England and France signed at Dover on 1 June 1670. It required that Charles II of England would convert to the Roman Catholic Church at some future date and th ...

, Charles II was obliged to assist Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

in his attack on the Dutch Republic in the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

. When the French army was halted by the Hollandic Water Line

The Dutch Waterline ( nl, Hollandsche Waterlinie, modern spelling: ''Hollandse Waterlinie'') was a series of water-based defences conceived by Maurice of Nassau in the early 17th century, and realised by his half brother Frederick Henry. Combine ...

(a defence system involving strategic flooding), an attempt was made to invade The Republic by sea. De Ruyter gained four strategic victories against the Anglo-French fleet and prevented invasion.

After these failures the English parliament forced Charles to make peace.

Fourth war: 1780–1784

The Dutch successful invasion of Britain placing William III of Orange-Nassau on the English throne as co-ruler with his wifeMary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

, called in British history the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688, ended the 17th century conflict between the Dutch Republic and Britain. This proved to be a pyrrhic victory

A Pyrrhic victory ( ) is a victory that inflicts such a devastating toll on the victor that it is tantamount to defeat. Such a victory negates any true sense of achievement or damages long-term progress.

The phrase originates from a quote from P ...

for the Dutch cause. William's main concern had been getting the English on the same side as the Dutch in their competition against France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. After becoming the British monarch, he granted many privileges to the British Royal Navy in order to ensure their loyalty and cooperation. William ordered that any Anglo-Dutch fleet be under English command, with the Dutch navy having 60% of the strength of the English.

By 1707 the formal union between the Kingdoms of England and Scotland had taken place with the new and more powerful

By 1707 the formal union between the Kingdoms of England and Scotland had taken place with the new and more powerful Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

being governed by the London-based Parliament. This new British state increasingly became the dominant military and economic force. The Dutch merchant elite began to use London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

as a new operational base and Dutch economic growth slowed. From about 1720 Dutch wealth ceased to grow at all; around 1780 the per capita gross national product

The gross national income (GNI), previously known as gross national product (GNP), is the total domestic and foreign output claimed by residents of a country, consisting of gross domestic product (GDP), plus factor incomes earned by foreign ...

of the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

surpassed that of the Dutch. Whereas in the 17th century the commercial success of the Dutch had inspired English jealousy and admiration, in the late 18th century the growth of British power, and the concurrent loss of Amsterdam's preeminence, led to Dutch resentment.

When the Dutch Republic began to support the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

that rebelled in 1775 against the British Crown, the fourth war broke out. The war made the Dutch Republic in turn fatally vulnerable to the French and led to regime change. The Dutch navy was much weakened, having only about twenty ships of the line, so there were no large fleet battles. The British tried to reduce the Republic to the status of a British protectorate, using Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n military pressure and gaining factual control over the Dutch colonies, with those conquered during the war given back at war's end. The Dutch then still held some key positions in the European trade with Asia, such as the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

and Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site si ...

. The war had sparked a new round of Dutch ship building (95 warships in the last quarter of the 18th century), but the British kept their absolute numerical superiority by doubling their fleet during the same period.

Later wars

In theFrench Revolutionary

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are consider ...

and Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

of 1793–1815, France reduced the Netherlands to a satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotope ...

and finally annexed the country in 1810. In 1797 the Dutch fleet was defeated by the British in the Battle of Camperdown

The Battle of Camperdown (known in Dutch as the ''Zeeslag bij Kamperduin'') was a major naval action fought on 11 October 1797, between the British North Sea Fleet under Admiral Adam Duncan and a Batavian Navy (Dutch) fleet under Vice-Admiral ...

. France considered both the extant Dutch fleet and the large Dutch shipbuilding capacity very important assets, but after the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...

gave up its attempt to match the British fleet, despite a strong Dutch lobby to this effect. After the incorporation of the Netherlands in the French Empire in 1810, Britain finished seizing all the Dutch colonies. With the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 (also known as the Convention of London; nl, Verdrag van Londen) was signed by the United Kingdom and the Netherlands in London on 13 August 1814.

The treaty restored most of the territories in Java that B ...

, Britain returned all those colonies to the new Kingdom of the Netherlands

, national_anthem = )

, image_map = Kingdom of the Netherlands (orthographic projection).svg

, map_width = 250px

, image_map2 = File:KonDerNed-10-10-10.png

, map_caption2 = Map of the four constituent countries shown to scale

, capital = ...

, with the exception of the Cape, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, and part of Dutch Guyana.

Some historians count the wars between Britain and the Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic ( nl, Bataafse Republiek; french: République Batave) was the successor state to the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 and ended on 5 June 1806, with the accession of Louis Bona ...

and the Kingdom of Holland

The Kingdom of Holland ( nl, Holland (contemporary), (modern); french: Royaume de Hollande) was created by Napoleon Bonaparte, overthrowing the Batavian Republic in March 1806 in order to better control the Netherlands. Since becoming Empero ...

during the Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislative ...

as the Fifth and Sixth Anglo-Dutch wars.

See also

*British military history

The military history of the United Kingdom covers the period from the creation of the united Kingdom of Great Britain, with the political union of England and Scotland in 1707, to the present day.

From the 18th century onwards, with the expansio ...

* Dutch military history

* Netherlands–United Kingdom relations

The Netherlands and the United Kingdom have a strong political and economic partnership.

Over forty Dutch towns and cities are twinned with British towns and cities. Both English and Dutch are West Germanic languages, with West Frisian, a min ...

Notes

Further reading

* Boxer, Charles Ralph. ''The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century'' (1974) * Bruijn, Jaap R. ''The Dutch navy of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries'' (U of South Carolina Press, 1993). * Geyl, Pieter. ''Orange & Stuart 1641–1672'' (1969) * Hainsworth, D. R., et al. ''The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652–1674'' (1998) * Israel, Jonathan Ie. ''The Dutch Republic: its rise, greatness and fall, 1477–1806'' (1995), pp. 713–726, 766–776, 796–806. The Dutch political perspective. * Jones, James Rees. ''The Anglo-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century'' (1996online

the fullest military history. * Kennedy, Paul M. ''The rise and fall of British naval mastery'' (1983) pp. 47–74. * Konstam, Angus, and Tony Bryan. ''Warships of the Anglo-Dutch Wars 1652–74'' (2011

excerpt and text search

* Levy, Jack S., and Salvatore Ali. "From commercial competition to strategic rivalry to war: The evolution of the Anglo-Dutch rivalry, 1609–52." in ''The dynamics of enduring rivalries'' (1998) pp. 29–63. * Messenger, Charles, ed. ''Reader's Guide to Military History'' (Routledge, 2013). pp. 19–21. * Ogg, David. ''England in the Reign of Charles II'' (2nd ed. 1936), pp. 283–321 (Second War); pp. 357–388. (Third War), Military emphasis. * Palmer, M. A. J. "The 'Military Revolution' Afloat: The Era of the Anglo-Dutch Wars and the Transition to Modern Warfare at Sea." ''War in history'' 4.2 (1997): pp. 123–149. * Padfeld, Peter. ''Tides of Empire: Decisive Naval Campaigns in the Rise of the West. Vol. 2 1654–1763.'' (1982). * Pincus, Steven C.A. ''Protestantism and Patriotism: Ideologies and the making of English foreign policy, 1650–1668'' (Cambridge UP, 2002). * Rommelse, Gijs "Prizes and Profits: Dutch Maritime Trade during the Second Anglo-Dutch War," ''International Journal of Maritime History'' (2007) 19#2 pp. 139–159. * Rommelse, Gijs. "The role of mercantilism in Anglo-Dutch political relations, 1650–74." ''Economic History Review'' 63#3 (2010) pp. 591–611.

External links

* .National Maritime Museum

London. * Dutch

Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Michiel de Ruyter

Michiel Adriaenszoon de Ruyter (; 24 March 1607 – 29 April 1676) was a Dutch admiral. Widely celebrated and regarded as one of the most skilled admirals in history, De Ruyter is arguably most famous for his achievements with the Dutch N ...

s' flagshi'The Seven Provinces'

is being rebuilt in the Dutch town of

Lelystad

Lelystad () is a municipality and a city in the centre of the Netherlands, and it is the capital of the province of Flevoland. The city, built on reclaimed land, was founded in 1967 and was named after Cornelis Lely, who engineered the Afsluitdi ...

.

* .

{{Authority control

Geopolitical rivalry

Military history of the Thirteen Colonies