Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester 1857 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Art Treasures of Great Britain was an exhibition of fine art held in

1859. Many details in this article are taken from this comprehensive record of the exhibition. It remains the largest art exhibition to be held in the UK,Art Treasures in Manchester: 150 years on

Manchester Art Gallery possibly in the world,Art Treasures Exhibition Returns To Manchester After 150 Years

Culture24, 5 October 2007 with over 16,000 works on display. It attracted over 1.3 million visitors in the 142 days it was open, about four times the population of Manchester at that time, many of whom visited on organised railway excursions. Its selection and display of artworks had a formative influence on the public art collections that were then being established in the UK, such as the

Suzanne Fagence Cooper, ''Antiques'', June 2001

Manchester Art Gallery and subpages It was visited by French historian

/ref> Unlike these earlier exhibitions, the Manchester exhibition was restricted to works of art without any industrial or trade items on display.

''The Daily Telegraph'', 13 November 2007 The idea for an exhibition in Manchester was first expressed in a letter sent on 10 February 1856 by John Connellan Deane, son of Irish architect Sir

John J. Parkinson-Bailey, Manchester University Press, 2000, , pp.77–78 The design of the main structure has been attributed to Francis Fowke, who later designed the

Vol.3, Alexandra Bounia, Ashgate Publishing, 2002, , pp.8–13 Internally, the building included a large hall, with corrugated iron sides and vaults supported by iron columns, with space for an orchestra at one end and a large

The exhibition comprised over 16,000 works split into 10 categories: Pictures by Ancient Masters, Pictures by Modern Masters, British Portraits and Miniatures, Water Colour Drawings, Sketches and Original Drawings (Ancient), Engravings, Illustrations of Photography, Works of Oriental Art, Varied Objects of Oriental Art, and Sculpture. The collection included 5,000 paintings and drawings by "Modern Masters" such as Hogarth, Gainsborough,

The exhibition comprised over 16,000 works split into 10 categories: Pictures by Ancient Masters, Pictures by Modern Masters, British Portraits and Miniatures, Water Colour Drawings, Sketches and Original Drawings (Ancient), Engravings, Illustrations of Photography, Works of Oriental Art, Varied Objects of Oriental Art, and Sculpture. The collection included 5,000 paintings and drawings by "Modern Masters" such as Hogarth, Gainsborough,

''The Burlington Magazine'', Vol. 99, No. 656 (Nov. 1957), pp. 361–363

BBC Manchester, 19 March 2008 The exhibition was used as a model for the display of art in public galleries during the second half of the 19th century. Although the works displayed were returned to private collections, many found their way into public collections over the following decades, having usefully boosted their reputation by their appearance in Manchester. The National Portrait Gallery in London had been founded in 1856 and opened its doors to the public in 1858. Scharf was its first director, and arranged the displays in chronological order, as the Manchester exhibition had done. A second but smaller National Art Treasures Exhibition was held inArt, City Spectacle: Revisiting the 1857 Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition Junior Conference

, University of Manchester, 2007

Drawing of the Art Treasures Exhibition BuildingArt Treasures in Manchester: 150 years on — Part oneArt Treasures in Manchester: 150 years on — Part twoList of photographic exhibits

*John Peck

Catalogue of the art treasures of the United Kingdom: collected at Manchester in 1857

Internet Archive – online

CALDESI & MONTECCHI (ACTIVE 1857–67) Photographs of the "Gems of the Art Treasures Exhibition", Manchester

{{List of world's fairs in Ireland and Great Britain 1857 in England History of Manchester World's fairs in England Art exhibitions in the United Kingdom 1857 in art 19th century in Manchester Festivals established in 1857 1857 festivals Queen Victoria Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Culture in Trafford

Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, England, from 5 May to 17 October 1857.''Exhibition of art treasures of the United Kingdom, held at Manchester in 1857. Report of the executive committee''1859. Many details in this article are taken from this comprehensive record of the exhibition. It remains the largest art exhibition to be held in the UK,Art Treasures in Manchester: 150 years on

Manchester Art Gallery possibly in the world,Art Treasures Exhibition Returns To Manchester After 150 Years

Culture24, 5 October 2007 with over 16,000 works on display. It attracted over 1.3 million visitors in the 142 days it was open, about four times the population of Manchester at that time, many of whom visited on organised railway excursions. Its selection and display of artworks had a formative influence on the public art collections that were then being established in the UK, such as the

National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of more than 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current di ...

, National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

.The Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester, 1857Suzanne Fagence Cooper, ''Antiques'', June 2001

Background

Manchester was a small provincial town in the medieval period, but by 1855 it was an industrial city with 95cotton mill

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Although some were driven ...

s and 1,724 warehouses.Art Treasures in detailManchester Art Gallery and subpages It was visited by French historian

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (29 July 180516 April 1859), was a French Aristocracy (class), aristocrat, diplomat, political philosopher, and historian. He is best known for his works ''Democracy in America'' (appearing in t ...

in 1835, who scathingly wrote:

A sort of black smoke covers the city ... From this foul drain, the greatest stream of human industry flows out to fertilise the world.Manchester gained city status in 1853, and the exhibition was financed by the city's increasingly affluent business grandees, who were motivated by a desire to demonstrate their cultural attainment, and inspired by the Paris International Exhibition in 1855, the Dublin Exhibition in 1853, and the

Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

in 1851. There had already been an "Exposition of British Industrial Art in Manchester" in 1845.Catalogue of the books in the Manchester free library: Reference department/ref> Unlike these earlier exhibitions, the Manchester exhibition was restricted to works of art without any industrial or trade items on display.

''The Daily Telegraph'', 13 November 2007 The idea for an exhibition in Manchester was first expressed in a letter sent on 10 February 1856 by John Connellan Deane, son of Irish architect Sir

Thomas Deane

Sir Thomas Deane ( Cork, 1792 – Dublin, 1871) was an Irish architect. He was the father of Sir Thomas Newenham Deane, and grandfather of Sir Thomas Manly Deane, who were also architects.

Life

Thomas Deane was born in Cork, the eldest son o ...

and a commissioner for the 1853 Dublin Exhibition, to Thomas Fairbairn

Sir Thomas Fairbairn, 2nd Baronet Deputy Lieutenant, DL (18 January 1823 – 12 August 1891) was an English industrialist and art collector.

Early life

Fairbairn was born in the Polygon in Ardwick, near the centre of Manchester. He was the thir ...

son of Manchester iron founder Sir William Fairbairn and a commissioner for the 1851 Great Exhibition. The concept quickly gained momentum: after an initial meeting on 26 March 1856, a guarantee fund of £74,000 was soon underwritten by around 100 contributors, and Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

and Prince Albert granted their patronage.

A General Committee established in May 1856, chaired by the Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire Lord Ellesmere (and, after his death in February 1857, by the Lord Overstone), assisted by an Executive Committee chaired by Fairbairn. Deane was appointed as General Commissioner, on an annual salary of £1,000. The committee took artistic advice from German art historian Gustav Waagen, who had published the first 3 volumes of his ''Treasures of Art in Great Britain'' in 1854. George Scharf was appointed as the exhibition's Art Secretary; he became secretary and director to the newly founded National Portrait Gallery in 1857.

Exhibition hall

The exhibition was held outside the city centre, on a three-acre site inOld Trafford

Old Trafford () is a football stadium in Old Trafford, Greater Manchester, England, and is the home of Manchester United. With a capacity of 74,197, it is the largest club football stadium (and second-largest football stadium overall after W ...

owned by Sir Humphrey de Trafford, Bt., which he had previously let as a cricket ground. Manchester Cricket Club surrendered its lease and moved a short distance to Old Trafford Cricket Ground

Old Trafford is a cricket ground in Old Trafford, Greater Manchester, England. It opened in 1857 as the home of Manchester Cricket Club and has been the home of Lancashire County Cricket Club since 1864. From 2013 onwards it has been known ...

. The site was conveniently adjacent to Manchester Botanical Garden and to the west of an existing railway line of the Manchester, South Junction and Altrincham Railway

The Manchester South Junction and Altrincham Railway (MSJ&AR) was a suburban railway which operated an route between Altrincham in Cheshire and Manchester London Road railway station (now Manchester Piccadilly station, Piccadilly) in Manches ...

. The railway company built a new station (now Old Trafford tram stop) which was used by thousands of visitors from the city and from further afield on organised excursions.

C.D. Young & Co, of London and Edinburgh – already engaged as builders of the new art museum in South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

(which later became the V&A) – were appointed as contractors to build a temporary iron-and-glass structure similar to the Crystal Palace in London, long and wide, with one central barrel vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

wide with a wide hip vault on either side roofing a wide central gallery running the length of the building, and narrower barrel vaults wide to either side, all crossed by a transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

towards the western end.''Manchester: an architectural history''John J. Parkinson-Bailey, Manchester University Press, 2000, , pp.77–78 The design of the main structure has been attributed to Francis Fowke, who later designed the

Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in London, and an ornamental brick entrance at the eastern end was designed by local architect Edward Salomons. The materials used included of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

, of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

, of glass and 1.5 million bricks.''The collector's voice: critical readings in the practice of collecting''Vol.3, Alexandra Bounia, Ashgate Publishing, 2002, , pp.8–13 Internally, the building included a large hall, with corrugated iron sides and vaults supported by iron columns, with space for an orchestra at one end and a large

pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurised air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a Musical keyboard, keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single tone and pitch, the pipes are provide ...

by Kirtland and Jardine. Each column bore the exhibition's monogram: "ATE". The hall was subdivided internally by partitions, creating separate galleries. The interior was lined with wood panels covered with calico. Most internal decoration was done by John Gregory Crace of London. A wide gallery ran around the transept at an upper level. The central third of each vault was glazed, providing ample diffuse light. In the summer, the glazing in the picture galleries was shaded with calico to prevent damage to the artworks, and firemen played water on the roof as a form of rudimentary air conditioning when the interior temperature exceeded . Young & Co's original quote of £24,500 proved over-optimistic, and cost overruns pushed the final bill up to £37,461.

Over the entrance was inscribed the first line of John Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tub ...

's '' Endymion'': "A thing of beauty is a joy for ever." By the exit was a line from Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

's Prologue to Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison (1 May 1672 – 17 May 1719) was an English essayist, poet, playwright, and politician. He was the eldest son of Lancelot Addison. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend Richard Steele, with w ...

's '' Cato'': "To wake the soul by tender strokes of art."

The hall also included two public refreshment rooms, First Class and Second Class, later supplemented by a tent outside, and a separate royal reception room. Following his visit, American author Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

wrote that, in the Second Class refreshment room:

John Bull and his female may be seen in full gulp and guzzle, swallowing vast quantities of cold boiled beef, thoroughly moistened with porter or bitter

Works exhibited

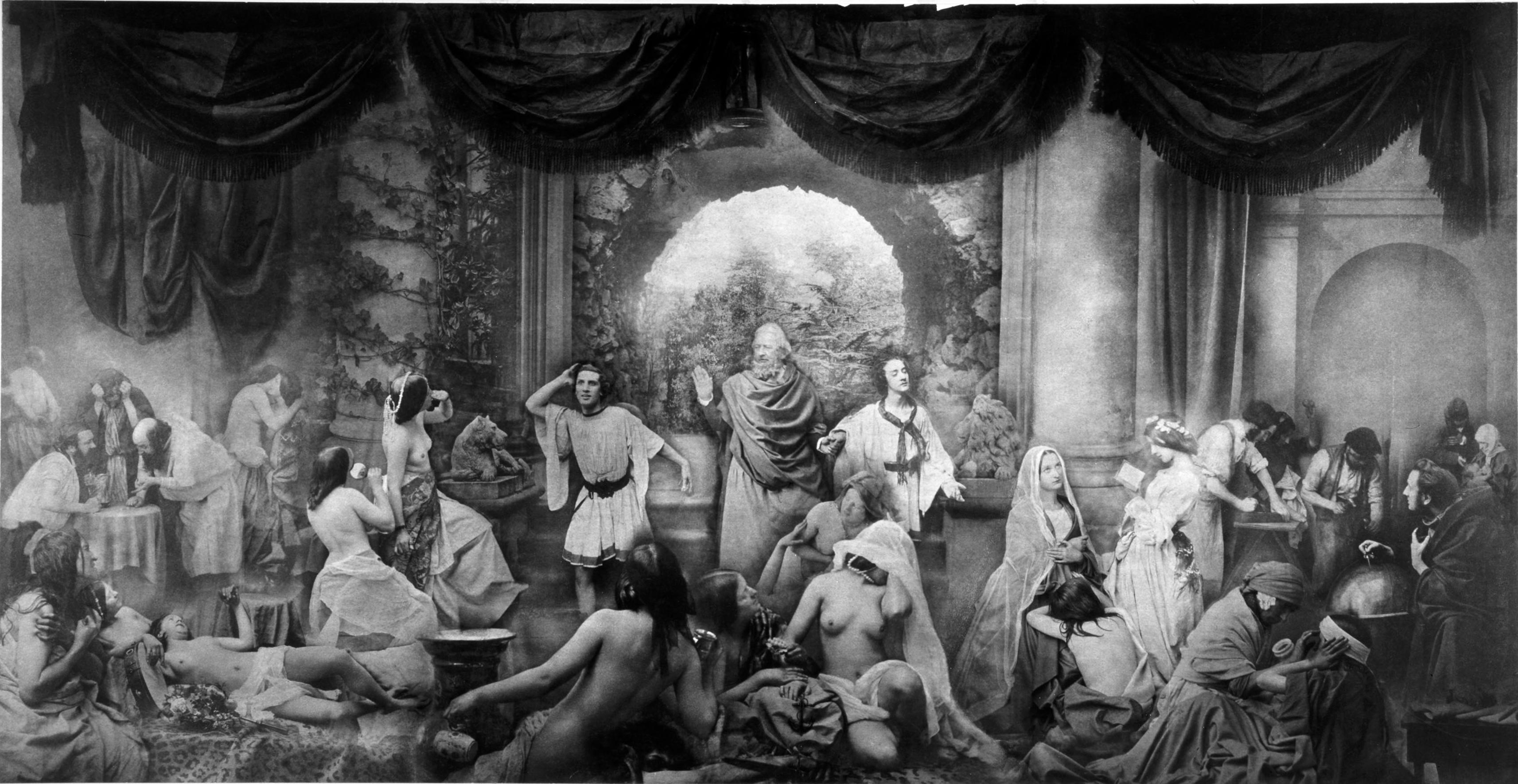

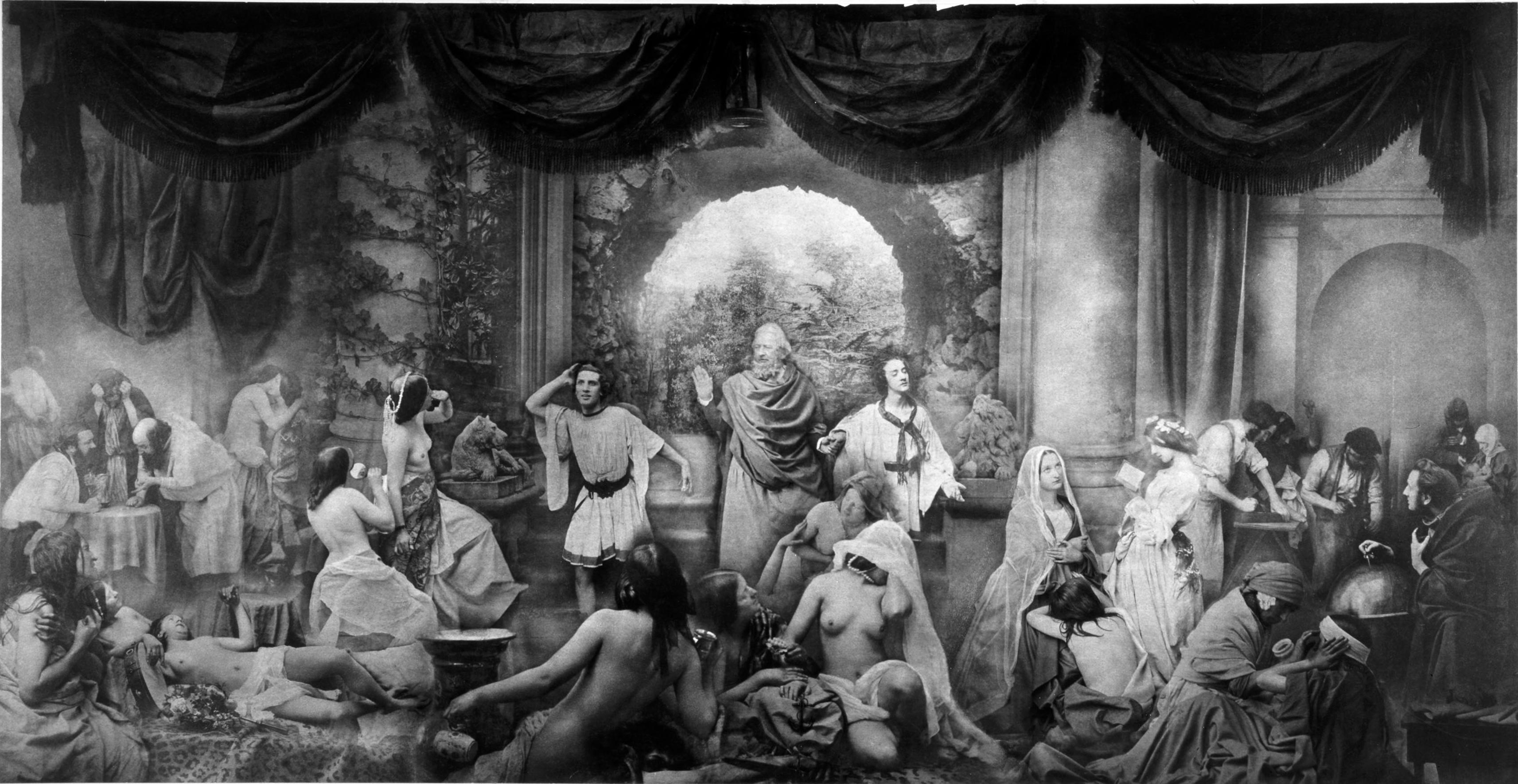

The exhibition comprised over 16,000 works split into 10 categories: Pictures by Ancient Masters, Pictures by Modern Masters, British Portraits and Miniatures, Water Colour Drawings, Sketches and Original Drawings (Ancient), Engravings, Illustrations of Photography, Works of Oriental Art, Varied Objects of Oriental Art, and Sculpture. The collection included 5,000 paintings and drawings by "Modern Masters" such as Hogarth, Gainsborough,

The exhibition comprised over 16,000 works split into 10 categories: Pictures by Ancient Masters, Pictures by Modern Masters, British Portraits and Miniatures, Water Colour Drawings, Sketches and Original Drawings (Ancient), Engravings, Illustrations of Photography, Works of Oriental Art, Varied Objects of Oriental Art, and Sculpture. The collection included 5,000 paintings and drawings by "Modern Masters" such as Hogarth, Gainsborough, Turner

Turner may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Turner (surname), a common surname, including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Turner (given name), a list of people with the given name

*One who uses a lathe for tur ...

, Constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. ''Constable'' is commonly the rank of an officer within a police service. Other peo ...

, and the Pre-Raphaelite

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), later known as the Pre-Raphaelites, was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, ...

s, and 1,000 works by European Old Master

In art history, "Old Master" (or "old master")Old Masters De ...

s, including Rubens

Sir Peter Paul Rubens ( ; ; 28 June 1577 – 30 May 1640) was a Flemish artist and diplomat. He is considered the most influential artist of the Flemish Baroque tradition. Rubens' highly charged compositions reference erudite aspects of clas ...

, Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), now generally known in English as Raphael ( , ), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. List of paintings by Raphael, His work is admired for its cl ...

, Titian

Tiziano Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian Renaissance painter, the most important artist of Renaissance Venetian painting. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno.

Ti ...

and Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (; ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), mononymously known as Rembrandt was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker, and Drawing, draughtsman. He is generally considered one of the greatest visual artists in ...

; several hundred sculptures; photographs, including Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

images by James Robertson and the photographic tableau ''Two Ways of Life'' by Oscar Gustave Rejlander; and other works of decorative arts, such as Wedgwood

Wedgwood is an English China (material), fine china, porcelain and luxury accessories manufacturer that was founded on 1 May 1759 by the potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood and was first incorporated in 1895 as Josiah Wedgwood and Sons L ...

china, Sèvres

Sèvres (, ) is a French Communes of France, commune in the southwestern suburbs of Paris. It is located from the Kilometre zero, centre of Paris, in the Hauts-de-Seine department of the Île-de-France region. The commune, which had a populatio ...

and Meissen porcelain

Meissen porcelain or Meissen china was the first Europe, European hard-paste porcelain. Early experiments were done in 1708 by Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus. After his death that October, Johann Friedrich Böttger continued von Tschirnhaus's ...

, Venetian glass, Limoges enamel

Limoges enamel has been produced at Limoges, in south-western France, over several centuries up to the present. There are two periods when it was of European importance. From the 12th century to 1370 there was a large industry producing metal o ...

s, ivories, tapestries, furniture, tableware and armour. The Committee bought the collection of Jules Soulages of Toulouse, founder of the Société Archéologique du Midi de la France for £13,500 to form the core of the collection of medieval and Renaissance decorative arts. The collection had previously been exhibited at Marlborough House

Marlborough House, a Grade I listed mansion on The Mall in St James's, City of Westminster, London, is the headquarters of the Commonwealth of Nations and the seat of the Commonwealth Secretariat. It is adjacent to St James's Palace.

The ...

in London with a view to being acquired for the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), but the Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry; in a business context, corporate treasury.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be ...

refused to fund the purchase. They were later acquired by the V&A.

The works were organised chronologically, to demonstrate the development of art, with works from northern Europe on one wall contrasted with contemporaneous works from southern Europe on the facing wall. Although the collection included works from Europe and the Orient, it had a clear emphasis on British works.

Most public British collections were in a nascent state, so most of the works were borrowed from 700 private collections. Many had never been exhibited in public before. The exhibition included the '' Madonna and Child with Saint John and the Angels'' which had only recently been attributed to Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6March 147518February 1564), known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspir ...

. The display of this unfinished work caused much excitement, and it is still known as the ''Manchester Madonna''. The French art critic Théophile Thoré commented that:'Art Treasures' Exhibition, 1857''The Burlington Magazine'', Vol. 99, No. 656 (Nov. 1957), pp. 361–363

''La collection de Manchester vaut à peu près leNot all private owners responded positively to the committee's entreaties to lend their works of art. William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire reportedly declined, replying contemptuously: What in the world do you want with art in Manchester? Why can't you stick to your cotton spinning?Louvre The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...'' ("Manchester's collection is worth almost as much as the Louvre's").

Visitors

The exhibition was opened by Prince Albert on 5 May 1857, in mourning following the death ofPrincess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh

Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh (25 April 1776 – 30 April 1857) was the eleventh child and fourth daughter of King George III and his consort Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

She married her first cousin, Prince William Fr ...

only a few days before, on 30 April. The exhibition was visited ceremonially by Queen Victoria on 29 June, during her second visit to Manchester, and then by the Queen and her entourage privately on 30 June. The exhibition ran until 17 October 1857, but was closed on Wednesday 7 October 1857 to mark a "day of humiliation" on account of the ongoing Indian Mutiny.

Season tickets were sold in advance for 2 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

(including admission on the two state ceremonial occasions) or 1 guinea (without). During the first 10 days, and on Thursdays, daily admission was half a crown; on other days, admission was reduced to 1 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

. An experiment in reducing admission to sixpence after 2 pm on Saturdays – to encourage working class visitors – did not noticeably increase revenue and was abandoned.

The exhibition attracted more than 1.3 million visitors – about four times the population of Manchester in 1857. Prominent visitors included the King of Belgium, the Queen of the Netherlands, Louis Napoleon, Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

, the 2nd Duke of Wellington, Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

, Alfred Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (; 6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of ...

, Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during th ...

, Elizabeth Gaskell

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (''née'' Stevenson; 29 September 1810 – 12 November 1865), often referred to as Mrs Gaskell, was an English novelist, biographer, and short story writer. Her novels offer detailed studies of Victorian era, Victoria ...

, John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

, Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

, and Maria Mitchell

Maria Mitchell ( ; August 1, 1818 – June 28, 1889) was an American astronomer, librarian, naturalist, and educator. In 1847, she discovered a comet named 1847 VI (modern designation C/1847 T1) that was later known as " Miss Mitchell's Comet ...

. Titus Salt commissioned three trains to transport 2,600 of his factory workers from Saltaire

Saltaire is a Victorian model village near Shipley, West Yorkshire, England, situated between the River Aire, the railway, and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Salts Mill and the houses were built by Titus Salt between 1851 and 1871 to allo ...

to visit on Saturday 19 September. Many other railway excursions were organised, mostly from the towns and cities around Manchester, but also Shrewsbury, Preston, Leeds, Grimsby, Nottingham, and Lincoln. Thomas Cook

Thomas Cook (22 November 1808 – 18 July 1892) was the founder of the travel agency Thomas Cook & Son. He was born into a poor family in Derbyshire and left school at the age of ten to start work as a gardener's boy. He served an appren ...

had arranged excursions to the Great Exhibition in 1851 and the Paris Exhibition in 1855, and this time he organised "moonlight" excursions from Newcastle

Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England, United Kingdom

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England, United Kingdom

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area ...

, leaving at midnight and returning late that evening.

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Karl Marx Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

about the exhibition: "Everyone up here is an art lover just now and the talk is all of the pictures at the exhibition".

To entertain the visitors, Charles Hallé was asked to organise an orchestra to perform a daily concert, in addition to a daily organ recital. After the exhibition closed, he continued running the orchestra, which became the Hallé Orchestra. A temporary "Art Treasure Hotel" housed some visitors overnight, and others were directed to local boarding houses.

The exhibition gave rise to several different publications. The committee published a 234-page catalogue, a series of "Handbooks" by type of object, and an illustrated weekly periodical "The Art Treasures Examiner". An apparently satirical book by "Tennyson Longfellow Smith" of "Poems inspired by Certain Pictures at the Art Treasures Exhibition" was illustrated with caricatures. A 16-page booklet was titled the "What to see, and Where to see it: The Operative's Guide to the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition" (an "operative" was the operator of a machine, as in a mill).

Sales of season tickets raised more than £20,000, added to daily admission fees amounting to nearly £61,000. Another £8,111 was raised by selling over 160,000 catalogues, plus £239 from selling concert programmes. Almost £1,500 came from the charges for safe-keeping of personal effects at the cloakroom, and £3,346 from the refreshments contract.

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Karl Marx Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

Aftermath

From gross receipts of £110,588 9s. 8d., the exhibition made a small profit of £304 14s. 4d, a good result compared to the crippling £20,000 loss made by the Dublin Exhibition, which ruined its organiser William Dargan. The railway that transported visitors to the site did even better, making a profit of about £50,000. After the exhibition ended, the exhibited works were returned to their owners, and the temporary building and its contents were auctioned. Glass display cases were bought by the new museums under construction in South Kensington. The building was entirely demolished by November 1858. Having cost over £37,000 in all, the materials comprising the building sold for little more than £7,000; internal fittings and decorations that cost £18,581 sold for £2,836. The site became part of Manchester Botanical Gardens, and was used to hold a Royal Jubilee Exhibition in 1887, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Queen Victoria's accession to the throne. The gardens closed in 1907, becoming White City Pleasure Gardens in 1907 and near the present-day White City Retail Park.The greatest art show ever?BBC Manchester, 19 March 2008 The exhibition was used as a model for the display of art in public galleries during the second half of the 19th century. Although the works displayed were returned to private collections, many found their way into public collections over the following decades, having usefully boosted their reputation by their appearance in Manchester. The National Portrait Gallery in London had been founded in 1856 and opened its doors to the public in 1858. Scharf was its first director, and arranged the displays in chronological order, as the Manchester exhibition had done. A second but smaller National Art Treasures Exhibition was held in

Folkestone

Folkestone ( ) is a coastal town on the English Channel, in Kent, south-east England. The town lies on the southern edge of the North Downs at a valley between two cliffs. It was an important harbour, shipping port, and fashionable coastal res ...

in May – October 1886. A large exhibition of paintings was held in Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the common la ...

, an industrial part of the East End of London, from 1872, designed specifically to attract working-class visitors. This was in what is now the V&A Museum of Childhood, using prefabricated buildings moved from South Kensington.

An exhibition was held at Manchester Art Gallery

Manchester Art Gallery, formerly Manchester City Art Gallery, is a publicly owned art museum on Mosley Street in Manchester city centre, England. The main gallery premises were built for a learned society in 1823 and today its collection occupi ...

in 2007–08 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Art Treasures Exhibition, and a conference was held at the University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The University of Manchester is c ...

in November 2007., University of Manchester, 2007

References

External links

Drawing of the Art Treasures Exhibition Building

*John Peck

Catalogue of the art treasures of the United Kingdom: collected at Manchester in 1857

Internet Archive – online

CALDESI & MONTECCHI (ACTIVE 1857–67) Photographs of the "Gems of the Art Treasures Exhibition", Manchester

{{List of world's fairs in Ireland and Great Britain 1857 in England History of Manchester World's fairs in England Art exhibitions in the United Kingdom 1857 in art 19th century in Manchester Festivals established in 1857 1857 festivals Queen Victoria Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Culture in Trafford