History

Native American settlement

Arlington County was inhabited by prehistoric Native American cultures from the arrival of the When John Smith made contact in 1608, Arlington was populated by the

When John Smith made contact in 1608, Arlington was populated by the Colonial era

Colonists began migrating from Jamestown and towards the Potomac River between 1646 and 1676, during which land After colonists depopulated the area in the aftermath of

After colonists depopulated the area in the aftermath of Revolutionary war and formation of federal district

The Stamp Act and In 1789, Virginia had offered to cede ten square miles or less and provide funding for the construction of public buildings. Congress accepted this as a part of the federal district, but specified that no public buildings would be erected in the Virginia section of the capital. Boundary stones were placed at one miles intervals along the borders of the district starting on April 15, 1791. The federal government and Congress moved to the new city of Washington within the District of Columbia in 1800; the Virginia section, which included Alexandria, became known as Alexandria County through the

In 1789, Virginia had offered to cede ten square miles or less and provide funding for the construction of public buildings. Congress accepted this as a part of the federal district, but specified that no public buildings would be erected in the Virginia section of the capital. Boundary stones were placed at one miles intervals along the borders of the district starting on April 15, 1791. The federal government and Congress moved to the new city of Washington within the District of Columbia in 1800; the Virginia section, which included Alexandria, became known as Alexandria County through the Antebellum period

In the early 19th century, the land outside of Alexandria, termed the "country part" of Alexandria County and representative of present-day Arlington, remained rural and dominated by several large plantations and smaller farms. Migration from northern states such as Enslaved

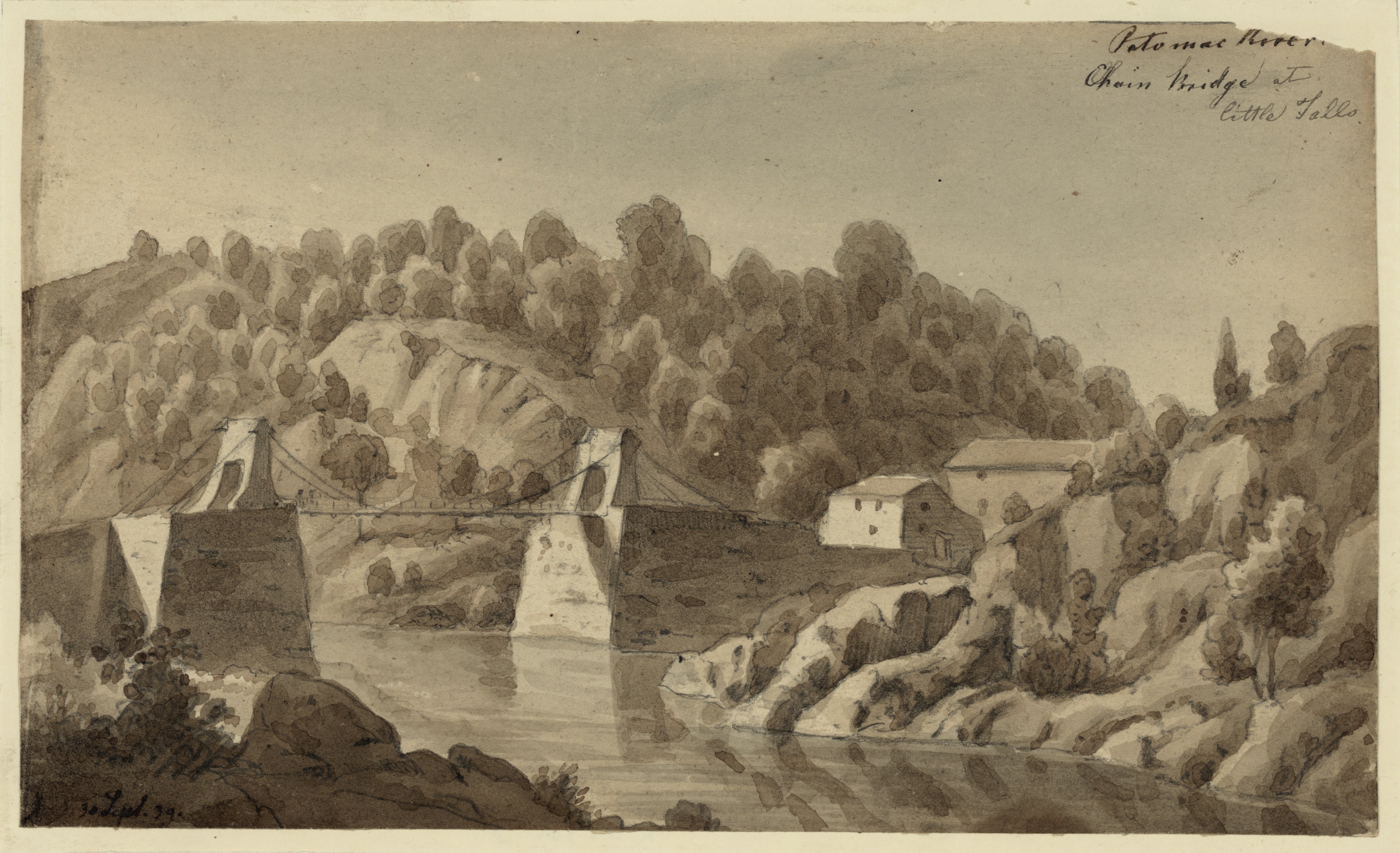

Enslaved  Major infrastructure, including the

Major infrastructure, including the Retrocession

The reintegration of Alexandria County into Virginia had been raised intermittently since the formation of the District, particularly by townspeople in Alexandria. Congressional debate of the issue began with discussion of the 1801 Organic Act and its implications, focusing on the lack of political rights afforded to District residents, who were not permitted to vote or have representation in Congress. Economic concerns relating to insufficient federal investment in infrastructure like the Alexandria Canal, which left Alexandria heavily indebted, motivated merchants and leaders in Alexandria to consider retrocession by the 1830s. The argument went that rejoining Virginia would bring financial relief to the municipal budget, greater support for economic development, restored political rights, and free Alexandria County from "antiquated" statutes Congress had inherited from older colonial laws and not updated.

Congress's failure to recharter banks in the District further frustrated Alexandria's business community, and in 1840 the Common Council of Alexandria convened a county-wide referendum on retrocession, with a majority voting in favor. After several years of lobbying by a committee of Alexandrians, the Virginia General Assembly introduced state legislation in July 1846 to accept Alexandria County back into Virginia territory if Congress agreed. Congress passed the Retrocession Act later that month that authorized the return of Alexandria County to Virginia pending another county referendum.

The referendum, held on September 1 and 2, passed with overwhelming support from Alexandrians, but was rejected by residents in the broader county; many in Alexandria County questioned the constitutionality of retrocession and felt marginalized by a movement that was primarily driven by Alexandria's business interests. George Washington Parke Custis, who had originally opposed retrocession due to concerns about the county's finances, changed sides after the Virginia General Assembly agreed to take on the debt incurred by the Alexandria Canal construction. Alexandria County was officially returned to Virginia on March 13, 1847, after the Virginia General Assembly passed the state's retrocession bill.

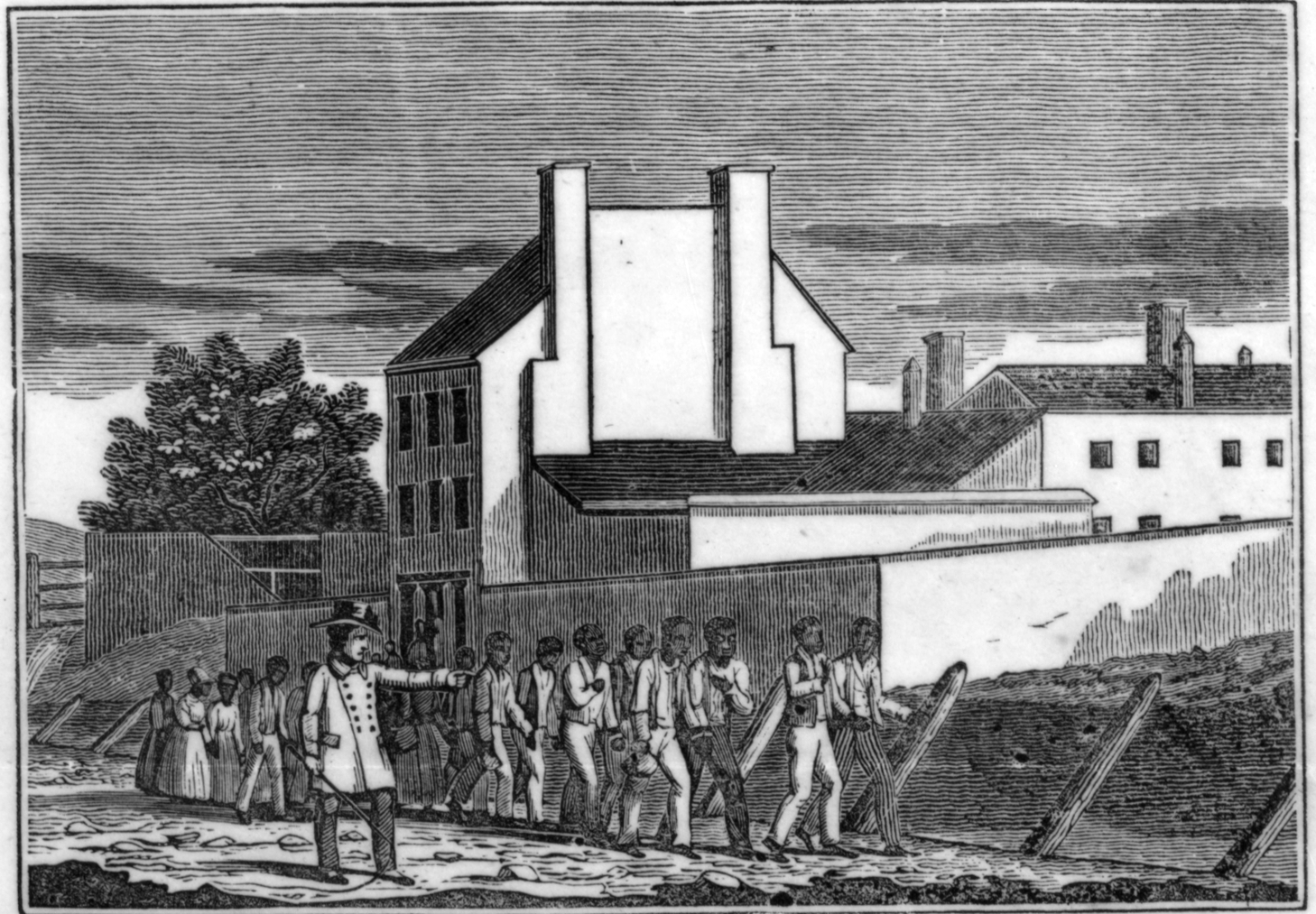

Beyond the freeholding whites in Alexandria County who were able to participate in the referendum, Alexandria County's free black community was also opposed to retrocession, as they anticipated the

The reintegration of Alexandria County into Virginia had been raised intermittently since the formation of the District, particularly by townspeople in Alexandria. Congressional debate of the issue began with discussion of the 1801 Organic Act and its implications, focusing on the lack of political rights afforded to District residents, who were not permitted to vote or have representation in Congress. Economic concerns relating to insufficient federal investment in infrastructure like the Alexandria Canal, which left Alexandria heavily indebted, motivated merchants and leaders in Alexandria to consider retrocession by the 1830s. The argument went that rejoining Virginia would bring financial relief to the municipal budget, greater support for economic development, restored political rights, and free Alexandria County from "antiquated" statutes Congress had inherited from older colonial laws and not updated.

Congress's failure to recharter banks in the District further frustrated Alexandria's business community, and in 1840 the Common Council of Alexandria convened a county-wide referendum on retrocession, with a majority voting in favor. After several years of lobbying by a committee of Alexandrians, the Virginia General Assembly introduced state legislation in July 1846 to accept Alexandria County back into Virginia territory if Congress agreed. Congress passed the Retrocession Act later that month that authorized the return of Alexandria County to Virginia pending another county referendum.

The referendum, held on September 1 and 2, passed with overwhelming support from Alexandrians, but was rejected by residents in the broader county; many in Alexandria County questioned the constitutionality of retrocession and felt marginalized by a movement that was primarily driven by Alexandria's business interests. George Washington Parke Custis, who had originally opposed retrocession due to concerns about the county's finances, changed sides after the Virginia General Assembly agreed to take on the debt incurred by the Alexandria Canal construction. Alexandria County was officially returned to Virginia on March 13, 1847, after the Virginia General Assembly passed the state's retrocession bill.

Beyond the freeholding whites in Alexandria County who were able to participate in the referendum, Alexandria County's free black community was also opposed to retrocession, as they anticipated the  While not mentioned prominently in contemporary debates about retrocession, modern historians and other figures have since argued that the future of slavery in Alexandria and Virginia more broadly was a significant factor. Growing

While not mentioned prominently in contemporary debates about retrocession, modern historians and other figures have since argued that the future of slavery in Alexandria and Virginia more broadly was a significant factor. Growing Civil War

The "country part" of Alexandria County leaned strongly Unionist, as indicated by the results of the May 23, 1861 vote held on the ratification of Virginia'sUnion occupation

The proximity of Alexandria County to Washington, as well as the direct lines of sight it offered to important landmarks, necessitated the construction of defenses to protect the capital.Joseph K. Mansfield

Joseph King Fenno Mansfield (December 22, 1803 – September 18, 1862) was a career United States Army officer and civil engineer. He served as a Union general in the American Civil War and was mortally wounded at the Battle of Antietam.

Early ...

The proximity of Alexandria County to Washington, as well as the direct lines of sight it offered to important landmarks, necessitated the construction of defenses to protect the capital.Joseph K. Mansfield

Joseph King Fenno Mansfield (December 22, 1803 – September 18, 1862) was a career United States Army officer and civil engineer. He served as a Union general in the American Civil War and was mortally wounded at the Battle of Antietam.

Early ...Military engagements

Throughout the war, Alexandria County only saw minor skirmishes between Union and Confederate forces. Confederate parties began engaging in guerrilla tactics against Union outposts in early June 1861, including a minor clash at Arlington Mill on June 2. The most significant battle took place in August 1861 at Ball's Crossroads, when Confederates stationed atArlington Cemetery and Freedman's Village

Congress's June 1862 enactment of an assessment of taxes owed by Southern property owners, and subsequent enforcement of tax collection, resulted in the Lee family owing $92.07 on Arlington plantation.Reconstruction through 1900

Years of occupation by Union troops left Alexandria County's economy in poor condition after the war; thousands of acres of farms and woodland had been destroyed. Local landowners who applied for compensation through the Changes in municipal governance in Virginia's 1870 Constitution required that all counties be divided into three or more districts, excluding any cities with a population greater than 5,000. This administratively separated Alexandria from the rest of the county and divided Alexandria County into the Arlington, Jefferson, and Washington Districts, with each having its own elected offices, public schools, and other facilities. The

Changes in municipal governance in Virginia's 1870 Constitution required that all counties be divided into three or more districts, excluding any cities with a population greater than 5,000. This administratively separated Alexandria from the rest of the county and divided Alexandria County into the Arlington, Jefferson, and Washington Districts, with each having its own elected offices, public schools, and other facilities. The  While this constituency was initially associated with the Republican Party, the rise of Virginia's Conservative Party, which opposed black suffrage and other Reconstruction-era reforms, eventually led to the Republicans abandoning their commitments to racial equality. Dissatisfied black voters, as well as white working class communities associated with the

While this constituency was initially associated with the Republican Party, the rise of Virginia's Conservative Party, which opposed black suffrage and other Reconstruction-era reforms, eventually led to the Republicans abandoning their commitments to racial equality. Dissatisfied black voters, as well as white working class communities associated with the 20th century suburbanization and Jim Crow segregation

In the first several decades of the 20th century, Alexandria County, officially renamed to Arlington County after the Arlington estate in 1920, rapidly developed into a commuter suburb of Washington. The ten-year period between 1900 and 1910 saw the creation of 70 new communities and subdivisions. Community organizations were established in these neighborhoods to advocate for their residents. During this period, the City of Alexandria succeeded in annexing significant portions of Arlington's southern area in 1915 and 1929; further annexations were prevented by the General Assembly in 1930. Developers and political figures such asNew Deal through Civil Rights

Beginning in the

The entry of the U.S. into

The entry of the U.S. into Arrival of Metrorail through present

Arlington County experienced decelerated population growth starting in 1960 as a result of continued migration of residents out to newer suburbs in Fairfax County and

After extended negotiations, the County Board convinced the

After extended negotiations, the County Board convinced the  The opening of the Metro stimulated another period of rapid growth. As planned, the corridor between Rosslyn and Ballston experienced revitalization driven by Mixed-use development, mixed-used, Transit-oriented development, transit-oriented development. Other areas near Blue line stations, such as Pentagon City, also became urbanized with numerous office complexes and retail centers like the Fashion Centre at Pentagon City, Pentagon City Mall that opened in 1989. As a result, Arlington increasingly transitioned away from being solely a commuter suburb of Washington and towards becoming an edge city with business and commercial districts.

In recent years, Arlington's highly educated workforce, proximity to Washington, and financial incentives offered by the government have encouraged multinational corporations, including

The opening of the Metro stimulated another period of rapid growth. As planned, the corridor between Rosslyn and Ballston experienced revitalization driven by Mixed-use development, mixed-used, Transit-oriented development, transit-oriented development. Other areas near Blue line stations, such as Pentagon City, also became urbanized with numerous office complexes and retail centers like the Fashion Centre at Pentagon City, Pentagon City Mall that opened in 1989. As a result, Arlington increasingly transitioned away from being solely a commuter suburb of Washington and towards becoming an edge city with business and commercial districts.

In recent years, Arlington's highly educated workforce, proximity to Washington, and financial incentives offered by the government have encouraged multinational corporations, including Geography

Arlington County is located in theGeology and terrain

Arlington County exists on a fall line between the Appalachian Piedmont (United States), Piedmont and the Atlantic Plain, Atlantic Coastal Plain. The fall line between these geologic provinces follows Interstate 66 between Rosslyn and Four Mile Run, and cuts south to the county border around U.S. Route 50. Arlington's Piedmont terrain is characterized by highly Erosion, eroded rolling Hill, hills; the county's highest prominence, Minor's Hill, is in this area and rises 451 Foot (unit), feet above sea level. The Coastal Plain is generally flat. Arlington is drained by Four Mile Run, Pimmit Run, and other small Stream, streams that all flow into the Potomac River. Some of these waterways have deep Valley, valleys that have been cut by erosion.Climate

Arlington County has a humid subtropical climate that is characterized by hot, humid summers, mild to moderately cold winters. Based on climate data captured at the National Weather Service's Reagan National Airport station, regional seasonal extremes vary from average lows of in January to average highs of in July. Annual precipitation averages at 41.82 inches, with an average low of 2.86 inches in January and average high of 4.33 inches in July. Average annual snowfall is 13.7 inches, with most occurring in February.

Arlington County has a humid subtropical climate that is characterized by hot, humid summers, mild to moderately cold winters. Based on climate data captured at the National Weather Service's Reagan National Airport station, regional seasonal extremes vary from average lows of in January to average highs of in July. Annual precipitation averages at 41.82 inches, with an average low of 2.86 inches in January and average high of 4.33 inches in July. Average annual snowfall is 13.7 inches, with most occurring in February.

Urban landscape

Since the opening of Metro service in the 1970s, Arlington County has become heavily urbanized; the local government has actively encouraged this via its smart growth, "Bull's Eye" urban planning model, where high density, mixed-use development is promoted within walking distance of Metro stations. County planners have termed neighborhoods within the corridors as "urban villages", where each is intended to have unique amenities and characteristics. These areas are rated highly for their walkability, access to public transit, and environmental sustainability, which align with design principles formulated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1996.

Arlington has attempted to address its environmental degradation, particularly in its watershed, which has been partially restored over the past several decades to improve local water quality and provide habitats for local wildlife. Past projects have included the installation of Living shoreline, living shorelines populated with native plants, removal of invasive vegetation along the lower Four Mile Run, and the conversion of Detention basin, stormwater catchment ponds into wetland habitats. These projects have provided enhanced habitats for Arlington's many native mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. Native fish that inhabit Arlington's waterways include American eel, Eastern blacknose dace, and White sucker; invasive species like Northern snakehead, snakehead and Common carp, carp are also present. The county government actively monitors the water quality and ecosystem of its watershed via a series of stream monitoring stations.

Since the opening of Metro service in the 1970s, Arlington County has become heavily urbanized; the local government has actively encouraged this via its smart growth, "Bull's Eye" urban planning model, where high density, mixed-use development is promoted within walking distance of Metro stations. County planners have termed neighborhoods within the corridors as "urban villages", where each is intended to have unique amenities and characteristics. These areas are rated highly for their walkability, access to public transit, and environmental sustainability, which align with design principles formulated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1996.

Arlington has attempted to address its environmental degradation, particularly in its watershed, which has been partially restored over the past several decades to improve local water quality and provide habitats for local wildlife. Past projects have included the installation of Living shoreline, living shorelines populated with native plants, removal of invasive vegetation along the lower Four Mile Run, and the conversion of Detention basin, stormwater catchment ponds into wetland habitats. These projects have provided enhanced habitats for Arlington's many native mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. Native fish that inhabit Arlington's waterways include American eel, Eastern blacknose dace, and White sucker; invasive species like Northern snakehead, snakehead and Common carp, carp are also present. The county government actively monitors the water quality and ecosystem of its watershed via a series of stream monitoring stations.

Demographics

The 2020 Census found that Arlington County's total population had reached 238,643, which represents growth of 14.9% since the 2010 Census. Arlington's population increase was 9.7% of growth experienced throughout the Northern Virginia region, and 4.9% in Virginia overall. Arlington continued to become more racially and ethnically diverse, with Arlington's Non-Hispanic White population growing 5%, but falling to 58.52% of the total population from 64.04% in 2010. Arlington's Asian population grew by 37.8% - the most of any single-racial group - during this period, and reached a population share of 11.41%. Those that identified as multi-racial or another race not listed in the census had the highest growth rates among all groups. Arlington had a total of 119,085 housing units, representing an increase of 13,681 units from 2010. According to American Community Survey, American Community Survey's 2023 estimates, Arlington's median age is 35.7, with 12.4% of individuals being above 65. Adults aged between 25 and 29 are the largest age bracket and make up 12.8% of the total population. 77.7% of the population has attained a bachelor's degree or higher; 42% of residents have a Master's or professional degree. 21.7% of Arlington's population is foreign-born; 48.4% of this segment are non-U.S. citizens. Married couple family households make up 36.7% of households; 44% of residents have never married.Government

Local government

Since 1930, Arlington County has been governed by a board of supervisors that appoint a County executive, County Manager, the latter of which oversees the county's everyday operations, as well as its departments and offices that provide administrative and regulatory services. Each of the board's five members are elected at-large and serving staggered 4-year terms. Since 2023, Primary election, primary elections for county board seats have been conducted via Ranked-choice voting in the United States, ranked choice voting. Board members elect a chair, who serves as the official head of county government, and vice-chair at annual organizational meetings held every January. The elected board chair and vice-chair share the same duties and responsibilities of their peers, and do not possess the power to veto motions. The board oversees various elements of county administration, including general policy, land use and zoning, tax rates, the issuance of proclamations, and the making of appointments to citizen advisory groups. The board also represents Arlington County at regional, state, and national forums and commissions. Other elected county officials include the school board and five constitutional officers, which consist of the Court clerk, County Clerk of the Circuit Court, Commissioner of the Revenue, District attorney, Commonwealth's Attorney, Sheriff, and Treasurer.State and federal representation

In Virginia's General Assembly, Arlington County is represented by three members of the Virginia House of Delegates, House of Delegates from the Virginia's 1st House of Delegates district, 1st, Virginia's 2nd House of Delegates district, 2nd, and Virginia's 3rd House of Delegates district, 3rd Districts, and two members of the Virginia Senate, Senate from Districts Virginia's 39th Senate district, 39 and Virginia's 40th Senate district, 40. Members of the House of Delegates and Senate serve two-year and four-year terms, respectively. In the lower chamber of the United States Congress, U.S. Congress, Arlington is part of Virginia's 8th congressional district of the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, which is represented by a single Representative elected every two years. Don Beyer, a Democrat, has served in this position since 2015. Virginia's two members in the United States Senate, Senate are elected on six-year terms. These positions have been occupied by Democratic Senators Mark Warner since 2009 and Tim Kaine since 2013.Politics

Historically a conservative Southern Democratic constituency, Arlington County has been liberal Democratic stronghold since the 1980s; a Republican candidate has not won Arlington in state or federal elections since 1981. The Democratic Party has also mostly held Arlington's local elected offices over the last several decades; the election of John Vihstadt, a Republican who ran as an independent, to the county board in November 2014 represented the first non-Democrat to win a county board general election since 1983. The demographic growth seen in Arlington and the broader Northern Virginia region, which is generally affiliated with the Democratic Party, has shifted Virginia's political orientation; largely as a consequence of its more diverse, urbanized regions, it has voted for the Democratic presidential nominee since 2008. Issues that have defined Arlington County politics in recent years have focused on how to manage rising costs of living and the county's housing supply, which has brought into debate the future of single-family zoning laws and community density, as well as lack of affordable housing options for residents. This has been expressed in the controversy surrounding the county board’s EHO housing policy. Also featured in recent elections has been Arlington's elevated office vacancy rates in the post-pandemic era, which have impacted revenue from commercial properties and increased the tax burden of residents for public services.Economy

Employers and workforce

Arlington County's economy is primarily Service economy, service-based, with a majority of its estimated 221,200 workers employed in professional services, technology companies, and federal, state, and municipal government in 2025; public employees made up around 20% of the workforce. Many private companies with a presence in Arlington serve various government agencies in Washington as Government contractor, contractors, including Deloitte, Booz Allen Hamilton, and Accenture. Large Arms industry, defense and Aerospace manufacturer, aerospace corporations such as 70% of all jobs in Arlington are within in the county's "planning corridors", which include Rosslyn-Ballston, Richmond Highway, Columbia Pike, and Langston Boulevard; most of Arlington's jobs are located in the Rosslyn-Ballston area. These districts are also home to Arlington's largest retail facilities, such as the Fashion Center at Pentagon City and Ballston Quarter. Work from home arrangements, which spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, continue to persist in the post-pandemic era, with 31.5% of workers working full time from their place of residence in 2023. This has contributed to Arlington's office vacancy rate, which rose to 24.2% in the fourth quarter of 2024 from 14.6% in 2020.

Arlington's unemployment rate, which rose to 4.3% during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, has been consistently under the average for the Washington metropolitan area since at least 2015. High levels of employment in the public sector has made Arlington vulnerable to cuts in federal government spending; this has been particularly acute in the Second presidency of Donald Trump, second Trump Administration, during which Arlington's unemployment rate rose to 3.3% in May 2025 as a result of broad spending cuts, 2025 United States federal mass layoffs, layoffs, and contract cancellations across numerous government agencies.

70% of all jobs in Arlington are within in the county's "planning corridors", which include Rosslyn-Ballston, Richmond Highway, Columbia Pike, and Langston Boulevard; most of Arlington's jobs are located in the Rosslyn-Ballston area. These districts are also home to Arlington's largest retail facilities, such as the Fashion Center at Pentagon City and Ballston Quarter. Work from home arrangements, which spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, continue to persist in the post-pandemic era, with 31.5% of workers working full time from their place of residence in 2023. This has contributed to Arlington's office vacancy rate, which rose to 24.2% in the fourth quarter of 2024 from 14.6% in 2020.

Arlington's unemployment rate, which rose to 4.3% during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, has been consistently under the average for the Washington metropolitan area since at least 2015. High levels of employment in the public sector has made Arlington vulnerable to cuts in federal government spending; this has been particularly acute in the Second presidency of Donald Trump, second Trump Administration, during which Arlington's unemployment rate rose to 3.3% in May 2025 as a result of broad spending cuts, 2025 United States federal mass layoffs, layoffs, and contract cancellations across numerous government agencies.

Income and housing

With a mean annual income estimated at $114,097, Arlington is one of the wealthiest municipalities in the United States; 31.3% of households had an annual income of $200,000 or more. Arlington's wealth is not equally distributed geographically or by racial background and tends to be concentrated in its wealthier northern neighborhoods that have a higher share of white households. Arlington's southern areas, which have greater racial and ethnic diversity and a higher population of immigrant families, have lower incomes and higher levels of poverty. This has been attributed to the county's historical underinvestment in the infrastructure and economy of southern Arlington, which is the location of several of Arlington's formerly segregated, historically black neighborhoods. Overall, 7.3% of Arlington residents were below the national poverty level in 2023. Arlington had an estimated total of 126,540 housing units in 2025, representing 6.3% growth since 2020. 73% of its housing supply consists of multifamily apartments or condos. The average rent in 2024 was $2,549; Homelessness in Arlington has been trending upwards since 2021; as of 2025, there were 271 homeless individuals, which represented a 12% increase from 2024.Landmarks

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is an American military cemetery established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Confederate States of America, Confederate GeneralThe Pentagon

The Pentagon in Arlington is the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense. It was dedicated on January 15, 1943, and it is the world's second-largest office building. Although it is located in Arlington County, the United States Postal Service requires that "Washington, D.C." be used as the place name in mail addressed to the six ZIP codes assigned to The Pentagon.

The building is pentagon-shaped and houses about 24,000 military and civilian employees and about 3,000 non-defense support personnel. It has five floors and each floor has five ring corridors. The Pentagon's principal law enforcement arm is the United States Pentagon Police, the agency that protects the Pentagon and various other DoD jurisdictions throughout the National Capital Region.

Built during World War II, the Pentagon is the world's largest low-rise office building with of corridors, yet it takes only seven minutes to walk between its furthest two points.

It was built from of sand and gravel dredged from the nearby

The Pentagon in Arlington is the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense. It was dedicated on January 15, 1943, and it is the world's second-largest office building. Although it is located in Arlington County, the United States Postal Service requires that "Washington, D.C." be used as the place name in mail addressed to the six ZIP codes assigned to The Pentagon.

The building is pentagon-shaped and houses about 24,000 military and civilian employees and about 3,000 non-defense support personnel. It has five floors and each floor has five ring corridors. The Pentagon's principal law enforcement arm is the United States Pentagon Police, the agency that protects the Pentagon and various other DoD jurisdictions throughout the National Capital Region.

Built during World War II, the Pentagon is the world's largest low-rise office building with of corridors, yet it takes only seven minutes to walk between its furthest two points.

It was built from of sand and gravel dredged from the nearby Transportation

Streets and roads

Arlington forms part of the region's core transportation network. The county is traversed by two Interstate Highway System, interstate highways: Interstate 66, I-66 in the northern part of the county and Interstate 395 (District of Columbia-Virginia), I-395 in the eastern part, both with high-occupancy vehicle lane, HOV lanes or restrictions. In addition, the county is served by the George Washington Memorial Parkway. In total, Arlington County maintains of roads. The street names in Arlington generally follow a unified countywide convention. The north–south streets are generally alphabetical, starting with one-syllable names, then two-, three- and four-syllable names. The first alphabetical street is Ball Street. The last is Arizona. Many east–west streets are numbered. Route 50 divides Arlington County. Streets are generally labeled North above Route 50, and South below. Arlington has more than of on-street and paved off-road bicycle trails. Off-road trails travel along thePublic transport

Forty percent of Virginia's transit trips begin or end in Arlington, with the vast majority originating fromOther

Capital Bikeshare, a bicycle sharing system, began operations in September 2010 with 14 rental locations primarily around

Capital Bikeshare, a bicycle sharing system, began operations in September 2010 with 14 rental locations primarily around Education

Primary and secondary education

Arlington Public Schools operates the county's public K-12 education system of 22 elementary schools, six middle schools, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Dorothy Hamm Middle School, Dorothy Hamm Middle School, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Gunston Middle School, Gunston Middle School, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Kenmore Middle School, Kenmore Middle School, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Swanson Middle School, Swanson Middle School, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Thomas Jefferson Middle School, Thomas Jefferson Middle School, and Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Williamsburg Middle School, Williamsburg Middle School, and three public high schools, Wakefield High School (Arlington County, Virginia), Wakefield High School, Washington-Liberty High School, and Yorktown High School (Arlington County, Virginia), Yorktown High School. H-B Woodlawn and Arlington Tech are alternative public schools. Arlington County spends about half of its local revenues on education. For the FY2013 budget, 83 percent of funding was from local revenues, and 12 percent from the state. Per pupil expenditures are expected to average $18,700, well above its neighbors, Fairfax County ($13,600) and Montgomery County ($14,900).

Arlington has an elected five-person school board whose members are elected to four-year terms. Virginia law does not permit political parties to place school board candidates on the ballot.

Through an agreement with Fairfax County Public Schools approved by the school board in 1999, up to 26 students residing in Arlington per grade level may be enrolled at the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Fairfax, Virginia, Fairfax at a cost to Arlington of approximately $8,000 per student. For the first time in 2006, more students (36) were offered admission in the selective high school than allowed by the previously established enrollment cap.

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Arlington helps provide Catholic education in northern Virginia, with early learning centers, elementary and middle schools at the parish level. Bishop Denis J. O'Connell High School is the diocese's Catholic high school within Arlington County.

Arlington Public Schools operates the county's public K-12 education system of 22 elementary schools, six middle schools, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Dorothy Hamm Middle School, Dorothy Hamm Middle School, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Gunston Middle School, Gunston Middle School, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Kenmore Middle School, Kenmore Middle School, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Swanson Middle School, Swanson Middle School, Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Thomas Jefferson Middle School, Thomas Jefferson Middle School, and Middle Schools of Arlington County, Virginia#Williamsburg Middle School, Williamsburg Middle School, and three public high schools, Wakefield High School (Arlington County, Virginia), Wakefield High School, Washington-Liberty High School, and Yorktown High School (Arlington County, Virginia), Yorktown High School. H-B Woodlawn and Arlington Tech are alternative public schools. Arlington County spends about half of its local revenues on education. For the FY2013 budget, 83 percent of funding was from local revenues, and 12 percent from the state. Per pupil expenditures are expected to average $18,700, well above its neighbors, Fairfax County ($13,600) and Montgomery County ($14,900).

Arlington has an elected five-person school board whose members are elected to four-year terms. Virginia law does not permit political parties to place school board candidates on the ballot.

Through an agreement with Fairfax County Public Schools approved by the school board in 1999, up to 26 students residing in Arlington per grade level may be enrolled at the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Fairfax, Virginia, Fairfax at a cost to Arlington of approximately $8,000 per student. For the first time in 2006, more students (36) were offered admission in the selective high school than allowed by the previously established enrollment cap.

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Arlington helps provide Catholic education in northern Virginia, with early learning centers, elementary and middle schools at the parish level. Bishop Denis J. O'Connell High School is the diocese's Catholic high school within Arlington County.

Colleges and universities

Sister cities

Arlington Sister City Association (ASCA) is a nonprofit organization affiliated with Arlington County, Virginia. ASCA works to enhance and promote the region's international profile and foster productive exchanges in education, commerce, culture and the arts through a series of activities. Established in 1993, ASCA supports and coordinates the activities of Arlington County's five sister cities: * Aachen, Germany * Coyoacán, Coyoacán (Mexico City), Mexico * Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine * Reims, France * San Miguel, El Salvador, San Miguel, El SalvadorNotable people

Notable individuals who reside or who have resided in Arlington County include: *Patch Adams, social activist and physician *Aldrich Ames, Soviet Union, Soviet double agent *Warren Beatty, actor *Sandra Bullock, actress *Katie Couric, television journalist *Roberta Flack, musician *John Glenn, former United States Senate, U.S. Senator and Mercury-Atlas 6 astronaut *Al Gore, 45th Vice President of the United States, U.S. vice president in the Presidency of Bill Clinton, Clinton administration *Grace Hopper, United States Navy, U.S. Navy rear admiral *See also

* Arlington Hall * Arlington Independent Media * List of federal agencies in Northern Virginia * List of neighborhoods in Arlington, Virginia * List of people from Washington, D.C. * List of tallest buildings in Arlington, Virginia * National Register of Historic Places listings in Arlington County, VirginiaNotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Arlington Historical Society

Project DAPS

– an online archive of primary sources related to School Desegregation in Arlington.

Why is it Named Arlington?

- history of the county's name {{Authority control Arlington County, Virginia, 1801 establishments in Virginia History of the District of Columbia Northern Virginia counties Populated places established in 1801 Virginia counties Virginia counties on the Potomac River Washington metropolitan area