''Archæologia Britannica'' (from

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

: ''Antiquities of Britain''), the first volume of which was published in 1707, is a pioneering study of the

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages ( ) are a branch of the Indo-European language family, descended from the hypothetical Proto-Celtic language. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, following Paul-Yve ...

written by

Edward Lhuyd

Edward Lhuyd (1660– 30 June 1709), also known as Edward Lhwyd and by other spellings, was a Welsh scientist, geographer, historian and antiquary. He was the second Keeper of the University of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum, and published the firs ...

.

Following an extensive tour of

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

lasting more than four years, Lhuyd began work on ''Glossography'', the first volume of a planned four-volume set, ''Archæologia Britannica'', which combined innovative methods of historical linguistics, language comparison, and field research, to establish a genetic relationship between the Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Gaulish languages. After a significant delay, the ''Glossography'' was finally published in 1707.

Due to Lhuyd's early death at the age of 49, the last three volumes were never produced or published, and many of Lhuyd's manuscripts and research notes were later lost, destroyed in two separate fires. As the only completed volume, the ''Glossography'' itself is often referred to as ''Archæologia Britannica''.

Summary

Lhuyd's basic argument in ''Glossography'' is that languages develop from a parent language by various processes of

linguistic change, such as

transposition of sounds or syllables, acquisition of

loanwords

A loanword (also a loan word, loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language (the recipient or target language), through the process of borrowing. Borrowing is a metaphorical term t ...

,

mispronunciation

In linguistics, mispronunciation is the act of pronouncing a word incorrectly. Languages are pronounced in different ways by different people, depending on factors like the area they grew up in, their level of education, and their social class. ...

, and use of different

prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the stem of a word. Particularly in the study of languages, a prefix is also called a preformative, because it alters the form of the word to which it is affixed.

Prefixes, like other affixes, can b ...

es or

suffix

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns and adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can ca ...

es. For example, he notes that sounds in one language may

correspond to a different sound in another language, so for instance

in Greek, Latin, Welsh, and Irish is changed into

in the 'Teutonic' (i.e. Germanic) languages.

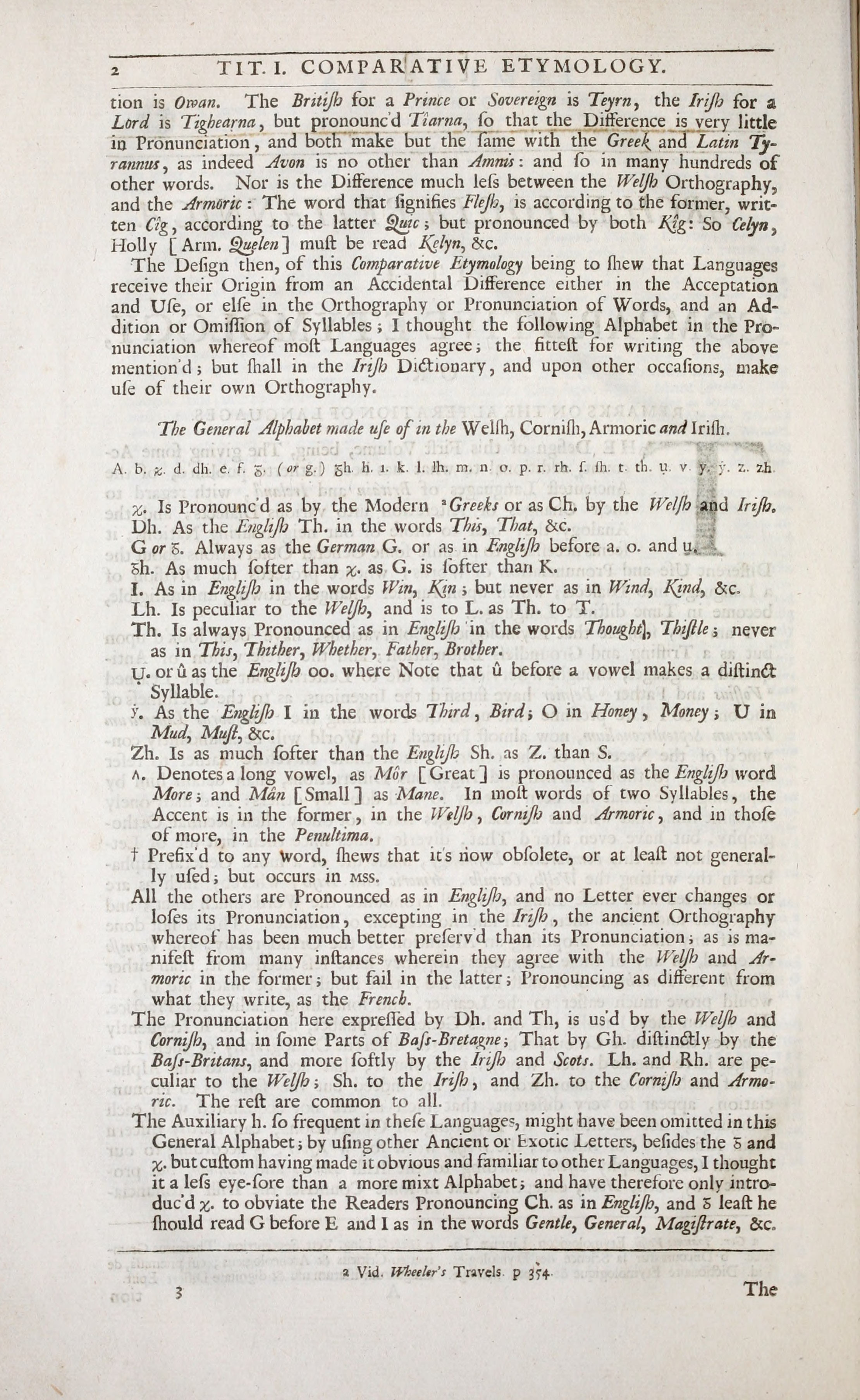

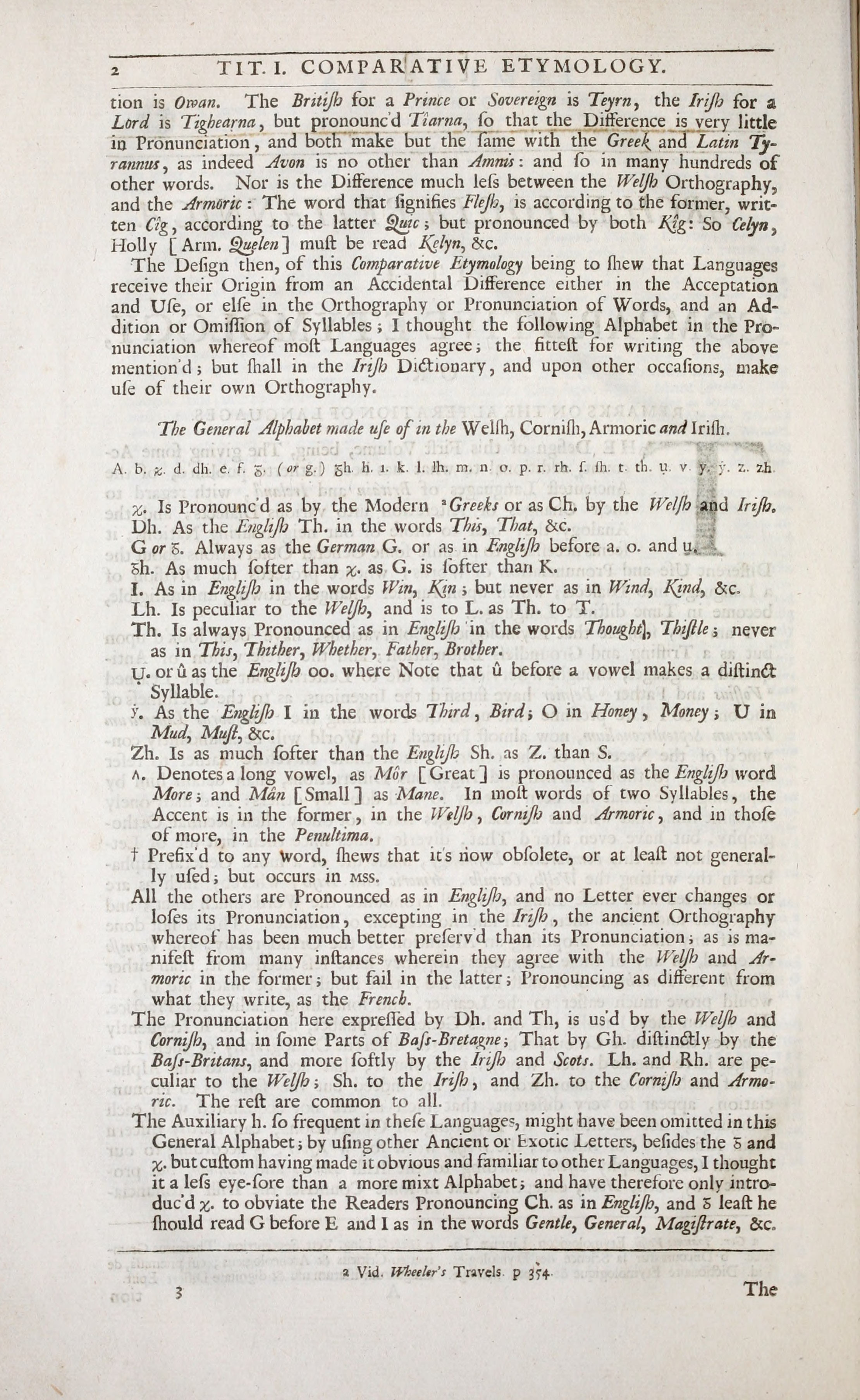

Lhuyd understood that different

orthographic conventions in different languages may hinder comparison, and introduces a ''General Alphabet'' to facilitate direct comparison between languages. His methodology allows a systematic study of

etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

, including a focus on regular sound changes, equivalence or similarity of meaning of

cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

Because language change can have radical effects on both the s ...

s, and shared

morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

, and emphasises that the basis of comparison should be the most basic parts of a language's core vocabulary.

Lhuyd realized that the Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Gaulish languages were closely related to each other, provided a number of phonetic correspondences that define the relationship between them, and proposed a genetic relationship between the

Goidelic

The Goidelic ( ) or Gaelic languages (; ; ) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from Ireland through the Isle o ...

and

Brittonic languages. Building on the earlier work of

George Buchanan

George Buchanan (; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth-century Scotland produced." His ideology of re ...

and

Paul-Yves Pezron, he categorized these languages as a ''Celtic'' language family sharing a common origin.

Lhuyd attempts to explain the linguistic differences in the Celtic languages using a model where Goidelic (or Q-Celtic) languages are first introduced to Britain and Ireland from

Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

, followed by a second, later migration, also from Gaul, of Brittonic (or P-Celtic) speakers, a model that

Barry Cunliffe

Sir Barrington Windsor Cunliffe (born 10 December 1939), usually known as Sir Barry Cunliffe, is a British archaeologist and academic. He was Professor of European Archaeology at the University of Oxford from 1972 to 2007. Since 2007, he has been ...

describes as being "broadly accepted and discussed by historical philologists over the last 300 years."

Background

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the identity of the

Greek ''Keltoi'', and Latin ''Celtae'' and ''Galli'', were discussed by scholars, with various national groups claiming descent from the ancient 'Celts' of antiquity, with no modern understanding of Celts as a linguistic group related to speakers of Brittonic or Goidelic languages. By the end of the sixteenth century, European intellectuals had begun to seriously debate whether Welsh and Irish, for example, were related languages.

Scaliger

The House of Della Scala, whose members were known as Scaligeri () or Scaligers (; from the Latinized ''de Scalis''), was the ruling family of Verona and mainland Veneto (except for Venice) from 1262 to 1387, for a total of 125 years.

History ...

had argued in the 1590s that these languages were unrelated.

George Buchanan

George Buchanan (; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth-century Scotland produced." His ideology of re ...

, on the other hand, had previously argued on philological grounds that the ancient Britons were Gaulish, and that Gaelic was also related to Gaulish, and he is often regarded as the first to recognize these languages as Celtic in the modern sense. Although several seventeenth-century writers supported this idea, the debate had not been conclusively resolved by the end of the seventeenth century.

In 1693, Edward Lhuyd, an antiquarian, naturalist, botanist, geographer, and philologist, and recently appointed Keeper of the

Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street in Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University ...

at the

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, was invited to contribute to the Welsh sections of

William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland that relates la ...

's ''Brittania'', a survey of Great Britain and Ireland. His work on this revision motivated him to begin his own

''magnum opus'', ''Archæologia Britannica'', an envisaged comparative study of the shared characteristics of the languages, archaeology, and culture of

Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

,

Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

,

Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

,

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, and

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

.

Following the publication of ''Britannia'' in 1695, Lhuyd published ''A Design of a British Dictionary, Historical & Geographical: with an Essay entitl'd Archæologia Britannica'', seeking subscribers to fund the research, fieldwork, and eventual publication of what was initially conceived as a multi-volume work, ''Archæologia Britannica or An Account of the Ancient Languages, Customs, and Monuments of the British Isles''. Following the successful publication of the ''Design'', Lhuyd printed a questionnaire, ''Parochial Queries'', three copies of which were distributed to every parish in Wales, providing Lhuyd with preliminary data with which to plan his fieldwork. The questionnaire asks for various types of information, including plants, minerals, stones, birds, quadrupeds, and the weather.

Tour of Celtic countries

With his assistants Robert Wynne, William Jones, and

David Parry, Lhuyd began his "great tour", lasting from 1697 to 1701. Lhuyd and his companions travelled Britain and Ireland for four years, studying and collecting manuscripts, ancient artefacts, and fossils, describing architecture and monuments, and recording local culture and spoken languages. The four-year long tour has been described as "made under the most difficult conditions of travel, and at great cost to

huyd'shealth and well-being."

Lhuyd's methodology included collection of primary data from native speakers, such as asking speakers to translate terms into their native languages.

North Wales (1696)

Lhuyd here initially conducted research from April to October of this year. Initial funding from subscribers allowed Lhuyd to go on a six-month tour. In June, Lhuyd met with

Richard Richardson, with whom he studied botany in

Snowdonia

Snowdonia, or Eryri (), is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in North Wales. It contains all 15 mountains in Wales Welsh 3000s, over 3000 feet high, including the country's highest, Snowdon (), which i ...

. Lhuyd also studied manuscripts at

Bangor and

Hengwrt

was a mansion near Dolgellau in Meirionnydd, Gwynedd. It lay in the parish of Llanelltyd near the confluence of the Afon Mawddach, River Mawddach and :cy:Afon Wnion, River Wnion, near Cymer Abbey. With medieval origins, it was rebuilt or remodel ...

, and visited eight or nine counties in total.

Wales (1697–1699)

Having trained others to take on his duties at Oxford and collected some funding, Lhuyd, along with his three assistants, began his tour in May 1697, travelling through Gloucestershire and the Forest of Dean, and reaching Chepstow on 13 May.

After three months, Lhuyd arrived at

Cowbridge

Cowbridge () is a market town in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, approximately west of the centre of Cardiff.

The Cowbridge with Llanblethian community and civil parish elect a town council.

A Cowbridge electoral ward exists for elections to ...

, where he spent two months copying a manuscript. Lhuyd spent a total of one year in south Wales, then travelled to Cardigan, then to Hereford in August 1698. Lhuyd obtained a Welsh-Latin dictionary and hunted fossils while in Wales.

On account of their research activities during their travels in Wales, Lhuyd and his assistants were suspected of being Jacobite spies, conjurers, or tax collectors by suspicious locals. Despite this,

Robert Gunther

Robert William Theodore Gunther (23 August 1869 – 9 March 1940) was a historian of science, zoologist, and founder of the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.

Gunther's father, Albert Günther, was Keeper of Zoology at the British Mus ...

states that his numerous connections in Wales made him a "welcome enquirer everywhere."

Ireland and Scotland (1699–1700)

From Wales, Lhuyd and his team reached Ireland in July or August 1699, landing in

Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, then travelled to

Antrim and visited

Newgrange

Newgrange () is a prehistoric monument in County Meath in Ireland, placed on a rise overlooking the River Boyne, west of the town of Drogheda. It is an exceptionally grand passage tomb built during the Neolithic Period, around 3100 BC, makin ...

and the

Giant's Causeway

The Giant's Causeway () is an area of approximately 40,000 interlocking basalt columns, the result of an ancient volcano, volcanic fissure eruption, part of the North Atlantic Igneous Province active in the region during the Paleogene period. ...

. They then took the ferry to

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

in late September or October, before returning to northern Ireland by boat in January 1700, visiting

Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

,

Connaught

Connacht or Connaught ( ; or ), is the smallest of the four provinces of Ireland, situated in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms ( Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine ...

, and

Munster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

, arriving in

Killarney

Killarney ( ; , meaning 'church of sloes') is a town in County Kerry, southwestern Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is on the northeastern shore of Lough Leane, part of Killarney National Park, and is home to St Mary's Cathedral, Killar ...

in July.

In the

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands (; , ) is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Scottish Lowlands, Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Scots language, Lowland Scots language replaced Scottish Gae ...

, Lhuyd recorded "the Highland Tongue" (

Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

) from native speakers, and also describes some small ancient glass charms he found. Lhuyd remarks in a letter that he learned very little Irish from the natives, learning most of that language from books.

According to Lhuyd, he was obliged to leave Ireland sooner than intended because of the "

Tories

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The T ...

of Kil-Arni."

Cornwall (1700–1701)

Probably directly from Ireland, or perhaps via Wales, Lhuyd arrived in Cornwall in August 1700. In Cornwall, Lhuyd was able to gather information about the Cornish language by listening to native speakers, especially the parish of

St. Just, from local antiquarians such as

Nicholas Boson and

John Keigwin, and from three manuscripts he was able to study,

Pascon agan Arluth, the

Ordinalia

The are three medieval mystery plays dating to the late fourteenth century, written primarily in Middle Cornish, with stage directions in Latin. The three plays are (The Origin of the World, also known as , 2,846 lines), (The Passion of Chris ...

, and

Gwreans an Bys. Lhuyd's team also produced sketches and plans of antiquities and ancient monuments, including

Boskednan stone circle

Boskednan stone circle () is a partially restored prehistoric stone circle near Boskednan, around northwest of the town of Penzance in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The megalithic monument is traditionally known as the Nine Maidens or Nine Stones ...

and

Chûn Castle

Chûn Castle is a large Iron Age hillfort (ringfort) near Penzance in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The fort was built about 2,500 years ago, and fell into disuse until the early centuries AD when it was possibly re-occupied to protect the ...

.

According to

Thomas Tonkin

Thomas Tonkin (1678–1742) was a Cornish landowner and historian.

Early life

He was born at Trevaunance, St Agnes, Cornwall, and baptised in its parish church on 26 September 1678, was the eldest son of Hugh Tonkin (1652–1711), vice-warden o ...

's account, Lhuyd and his assistants were arrested as suspected thieves, and brought in front of a

justice of the peace, who then released them. Lhuyd and his team visited many places in Cornwall, including

Penzance

Penzance ( ; ) is a town, civil parish and port in the Penwith district of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is the westernmost major town in Cornwall and is about west-southwest of Plymouth and west-southwest of London. Situated in the ...

, Lambriggan, and

Falmouth.

John Keigwin's reaction to Lhuyd's arrival in

Mousehole

Mousehole () is a village and fishing port in Cornwall, England, UK. It is approximately south of Penzance on the shore of Mount's Bay. The village is in the civil parish of Penzance. An islet called St Clement's Isle lies about offshore fro ...

is satirized in

Alan Kent's

Anglo-Cornish dialect play, ''Dreaming in Cornish'':

Brittany (1701)

From Falmouth, Lhuyd arrived in

Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo language, Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany (administrative region), Brittany.

The Fortification, walled city on the English Channel coast had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth ...

,

Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

in January 1701. Here, Lhuyd was able to procure two seventeen-century Breton dictionaries, one of which he could only obtain in exchange for his own copy of Davies' dictionary.

In Brittany, Lhuyd and his companions were jailed on suspicion of being English spies. According to Lhuyd, after arousing the suspicion of locals, his letters and documents were seized, his pockets searched, and he was imprisoned at

Brest Castle for 18 days. After authorities found nothing treasonous in the seized documents, they were released, but then forced to leave the kingdom, as war "was already declar'd against the Empire, the Dutch, and the English." He eventually returned to England in March.

Itinerary

Proposed volumes

As originally conceived in ''Design'', Lhuyd intended ''Archæologia Britannica'' to be divided into four volumes:

*Volume I: "A comparison of the modern Welsh with other European languages", particularly Greek, Latin, Irish, Cornish, and Armorican (Breton).

*Volume II: A comparison of the customs and traditions of the Britons with those of other nations. According to the Welsh preface of volume I, this was intended to be a "Dictionary of history of ye Kings, Princes, Ancient nobility, ye Towns, Castles Churches and Saints and of all other very remarkable men and places, of ye British nation, mention'd in ancient records"

*Volume III: "An account of all such monuments now remaining in Wales as are presumed to be British; and either older or not much later than the Roman Conquest."

*Volume IV: "An Account of the Roman antiquities there and others of later Date, during the Government of the British Princes; together with Copies of all the Inscriptions of any considerable Antiquity."

On account of Lhuyd’s early death, only the first volume, ''Glossography'', was eventually published.

Publication

''Glossography'' was completed in November 1703, at which time it was delivered to the printer. It was not published until 1707, however, due to a lack of suitable

movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable Sort (typesetting), components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric charac ...

for the complex orthography used in the volume, which consisted of an extended Latin alphabet combined with a variety of diacritics, meaning only one compositor could perform the task.

Contents

The names of the subscribers towards the author's travels; as also of those who were pleased to contribute without subscribing

Lhuyd lists here subscribers and financial contributors, mostly clergy, lawyers, physicians, clerics, and gentry. In addition to providing financial support, Lhuyd's subscribers had also been encouraged to contribute research material.

To the right honourable Sr Thomas Mansel of Margam

Lhuyd describes the incompleteness of the work, his fatigue after five years' travels, and his experiences gathering information for AB. He expresses his hope that the book will provide a clearer understanding of the ancient languages of Britain and Ireland, and thanks

Mansel for his generosity and promotion of scholarship in general.

Preface

In the English language preface, Lhuyd explains his motivation for publishing the Glossography before the other volumes, and summarizes the contents. This chapter also contains prose and poetry in praise of the volume in Welsh, Irish, and Latin by other scholars.

''At y Kymry''

In this chapter, a Welsh-language preface, Lhuyd writes that, after writing Irish and Cornish prefaces, he feels obliged to address the Welsh in "our mother tongue". Lhuyd mentions his unusual orthography, stating that, as others are free to choose their own orthography, so he asks the same freedom to use his, pointing out the benefits of being able to transcribe multiple languages in a single spelling system, using single letters for each sound, and compatibility with old manuscripts.

Lhuyd then apologises for the time it has taken to produce the first volume, stating that he did not initially intend to travel for so long or in so much detail, or to write such a large essay.

Lhuyd outlines his migration model for the Celtic settlement of Britain:

Title I: Comparative etymology. Or remarks on the alteration of languages

This title examines lexical and phonological correspondences in different languages, as well as semantic changes. In total this title consists of 24 linguistic observations, which Lhuyd later divides into 10 classes in a "summary of etymology". Lhuyd attaches special emphasis to this part of the volume, and accordingly places it at the beginning of the work.

He explains that it "consists wholly of Parallel Observations relating to the Origin of Dialects, the affinity of the British with other languages, and their correspondence to one another. What I aim'd at therein, was the shewing by a collection of examples methodized, that etymology is not, as a great many, till they have considered it with some application, are apt to be perswaded, a speculation merely groundless or conjectural."

Class I

Synopsis:

In "Observation I", for instance, he gives as an example, meaning 'fist' in Welsh and Irish, but 'hand' in Cornish and Breton.

Class II

Synopsis:

In "Observation II", he notes the many words in the

Old Cornish Vocabulary (OCV) that are no longer understood by the Cornish, but still used by the Welsh. † 'a hermit' from the OCV is listed with an obelus as one example.

Class III

Synopsis:

"Observation III" includes examples of

metathesis, such as Welsh , Cornish 'to buy'.

Class IV

"Transposition of Compounds."

In "Observation IV", Lhuyd describes transposition of compounds, such as Welsh 'squint-eyed' and Cornish , which "be but their corrupt pronunciation of the same word, transpos'd."

Class V

Syunopsis:

"Observation V" describes how initial vowels may be added to the beginning of words. "Observation VI" describes how

vowel

A vowel is a speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract, forming the nucleus of a syllable. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness a ...

s may be added to words internally. "Observation VII" gives examples of

labials inserted into words. "Observation VIII" gives examples of

palatals

Palatals are consonants articulated with the body of the tongue raised against the hard palate (the middle part of the roof of the mouth). Consonants with the tip of the tongue curled back against the palate are called retroflex.

Characteristi ...

inserted into words. "Observation IX" describes the addition of "lingual mutes" in various positions. "Observation X" describes the addition of

liquids

Liquid is a state of matter with a definite volume but no fixed shape. Liquids adapt to the shape of their container and are nearly incompressible, maintaining their volume even under pressure. The density of a liquid is usually close to th ...

.

Class VI

"Letters Omitted ... This has happen'd after the same manner

s class V"

In "Observation XI", Lhuyd describes

apheresis

Apheresis ( ἀφαίρεσις (''aphairesis'', "a taking away")) is a medical technology in which the blood of a person is passed through an apparatus that separates one particular constituent and returns the remainder to the circulation. ...

,

syncope, and

apocope

In phonology, apocope () is the omission (elision) or loss of a sound or sounds at the end of a word. While it most commonly refers to the loss of a final vowel, it can also describe the deletion of final consonants or even entire syllables.

...

, where vowels are lost initially, internally, and in word-final positions, respectively. "Observation XII" through "Observation XVI" describe how various classes of

consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract, except for the h sound, which is pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Examples are and pronou ...

al sounds are "omitted".

Class VII

Synopsis:

"Observation XI" gives numerous examples, including Breton ⟨⟩, an otter, contrasting with Welsh ⟨⟩.

Class VIII

Synopsis:

"Observation XVII" contrasts word endings in Welsh, Cornish, Breton, and Irish. The many examples given include Welsh 'snow', at variance with Cornish and Breton ; and Welsh 'name', in contrast with Irish .

Class IX

Synopsis:

In "Observation XVIII", Lhuyd goes into some detail describing vowel variations in cognate words in the Celtic languages. These are defined as ''classical'' (change of letters into the same class, or the same organ of pronunciation), ''idiomatal'' (when, from observation, at least five or six examples of primitive words show a letter of one class in one language changing into a letter of another class in another language), and ''accidental'' (similar to the previous type, but infrequent).

"Observation XIX", focusing on the

labial consonant

Labial consonants are consonants in which one or both lips are the active articulator. The two common labial articulations are bilabials, articulated using both lips, and labiodentals, articulated with the lower lip against the upper teeth, b ...

s /p/, /b/, /f/, /v/, and /m/, describes

lenition

In linguistics, lenition is a sound change that alters consonants, making them "weaker" in some way. The word ''lenition'' itself means "softening" or "weakening" (from Latin 'weak'). Lenition can happen both synchronically (within a language ...

, part of the Celtic grammatical mutation system (for example Welsh 'head' becoming 'his head'). Lhuyd also notes the equivalence of Welsh ⟨p⟩ with Irish ⟨c⟩ or ⟨k⟩, with examples including Welsh 'four' and Irish , and also notes that ⟨p⟩ is a rare letter in Irish, apart from loanwords. "Observation XX" through "Observation XXII" catalogue a large number of sound correspondences of various types between cognate words, including in the Celtic languages, but also in Latin, Greek, and other languages.

Class X

"Forreign words introduced by Conquest or borrow'd from those Nations with whom we have Trade and Commerce."

In "Observation XXIII", Lhuyd notes the large number of Latin words in the Welsh, Cornish, and Breton vocabularies. He remarks that "part were doubtless brought hither by the first inhabitants; long before the Romans were a distinct people." From this supposed period, Lhuyd suggests basic vocabulary such as Welsh , Latin 'land'. Lhuyd goes on to suggest that more advanced vocabulary came from the period of

Roman occupation of Britain

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of ''Britannia'' after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Julius Caesa ...

. A pair of examples he provides is Welsh and Latin , 'slave'.

In "Observation XXIV", Lhuyd describes how compounds or phrases may be translated from one language to another, or: "Words Deriv'd From One Common Origin as to Signification Tho' of No Affinity in Sound." He gives examples including Welsh 'butterfly', equivalent to Cornish , and Scottish Gaelic .

Title II: A comparative vocabulary of the original languages of Britain and Ireland

This title consists of a vocabulary arranged alphabetically with Latin headwords glossed with Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx translation equivalents, written in the phonetic transcription system devised by Lhuyd and introduced in the previous title.

Title III: An Armoric grammar by Julian Manoir, Jesuit

This title is a translation by

Moses Williams of the Breton grammar originally written in French by

Julian Maunoir

Julien Maunoir (1 October 1606 – 28 January 1683) (also Julian; ), was a French-born Jesuit priest known as the "Apostle of Brittany". He was beatified in 1951 by Pope Pius XII and is commemorated by the Catholic Church on 29 January and 2 Jul ...

.

Chapter I: Writing and pronunciation

Following a description of the benefits of spelling words according to how they are pronounced, this chapter goes into some detail regarding pronunciation of letters and the meaning of diacritics.

Chapter II: Nouns

This chapter describes the "Armoric" (Breton)

definite

In linguistics, definiteness is a semantic feature of noun phrases that distinguishes between referents or senses that are identifiable in a given context (definite noun phrases) and those that are not (indefinite noun phrases). The prototypical ...

and

indefinite article

In grammar, an article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the ...

s. There follows a description of the lack of grammatical

declension

In linguistics, declension (verb: ''to decline'') is the changing of the form of a word, generally to express its syntactic function in the sentence by way of an inflection. Declension may apply to nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, and det ...

in "Armoric", and a synopsis of the various plural noun endings.

Having given the most common plural endings, Section 7, "Heteroclites", lists nouns which form their plurals by vowel change, removal of singulative suffixes, or other less common ways.

The chapter then gives an overview of adjectives, and the lack of declension for number, except for certain pronouns. It then describes how regular comparatives and superlatives are formed, noting certain exceptions.

Chapter III: Pronouns

Pronouns are given in the nominative, genitive, dative, and accusative case.

Chapter IV: Verbs

The verbs 'to be' and 'to have' are described, as well as their use as

auxiliaries

Auxiliaries are combat support, support personnel that assist the military or police but are organised differently from regular army, regular forces. Auxiliary may be military volunteers undertaking support functions or performing certain duties ...

, and grammatical tense and moods.

There follows a section of active, passive, and irregular verb tables, conjugated for tense and mood.

Chapter V: Participles, adverbs, and prepositions

This chapter covers active and passive participles.

Some examples of Breton adverb usage are given, such as 'the wisest of all'.

A selection of common prepositions, including 'from', 'with', and 'without' are given, with their usage described in the next chapter.

Chapter VI: Syntax

The grammar describes "Armoric" sentence structure. Nominal sentences, for instance 'I love', are described. Impersonal verbs with no nominative case before them, for example 'It rains', are also given.

The grammar notes that adjectives follow the noun they describe in Breton. Correct usage of possessive pronouns is described. The grammar describes how "nouns of number" take singular nouns, for example 'two men'.

The section concludes with summaries of a number of different constructions, and a synopsis of the Breton mutation system.

Title IV: An Armoric vocabulary by Julian Manoir, Jesuit

This title, also by Lhuyd’s assistant Moses Williams, translates Julian Maunoir's Breton wordlist.

Title V: Some Welch words omitted in Dr Davies's Dictionary

Supplement to

John Davies's Welsh dictionary, .

Title VI: A Cornish grammar

Lhuyd writes a preface in the Cornish language. He begins by apologising for the grammar to follow, being neither born in Cornwall nor having stayed there for more than four months. He states that the inhabitants of Cornwall could produce the grammar better than himself. He expresses the hope that "this poor work" might cause somebody else to produce something better. He explains how he acquired his knowledge of the Cornish language; from the inhabitants of the west of Cornwall, particularly in St. Just; by the help of gentlemen antiquaries, who provided him with Cornish words; and from three manuscripts given him by the Bishop of Exeter,

Sir Jonathan Trelawney, from which he says he got "the best part" of his knowledge. He describes his discovery that the manuscript labelled was, in fact, a Cornish vocabulary.

Lhuyd describes changes in Cornish pronunciation over time based on the manuscripts he has studied, such as the development of pre-occlusion in the contemporary Cornish language, where they now "put the letter ''b'', before the letter ''m''", and "the letter ''d'', before the letter ''n''", palatalization of Old Cornish /t/ and /d/, and various other phonological features which distinguish Cornish from Welsh. Lhuyd expresses his view that Cornish is closer to Breton dialects than Welsh, which he suggests is due to Breton migration into Cornwall.

Chapter I: Of the letters

This section reintroduces Lhuyd's "General Alphabet", with some additions specifically for the Cornish language.

Lhuyd then provides a discussion of the ancient manuscripts he is aware of, along with a synopsis of the orthographic variations and his interpretation of the relationship of the written word to the pronunciation in these documents.

This is followed by a synopsis of the changes in the initial consonants of words in certain grammatical contexts, a feature of the Cornish

mutation system.

Lhuyd then notes some of the sound changes from earlier Cornish to the Cornish at the time; , the change of , as he writes in his "General Alphabet", or as written by medieval Cornish scribes, to , the change of most Old Cornish orthographic to later Cornish orthographic , which he notes is now pronounced /z/, and the development of /t/ to /tʃ/ (the sound of ''ch'' in English ''church'') in a few words.

Lhuyd also gives some examples of vowel insertion, for instance † is now pronounced as . He also describes the development of pre-occlusion, where /b/ is inserted before a "middle" (medial) /m/ to give /bm/, and similarly /d/ is inserted before a "middle" /n/ to give /dn/.

The chapter closes with description of vowel loss, and the loss of certain consonants, such as initial /g/, in specific contexts.

Chapter II: Some further Directions for Reading old British Manuscripts

There is a further guide to reading ancient manuscripts, in which Lhuyd discusses how particles with grammatical function are often joined to other words in old Welsh and Cornish documents.

Lhuyd then describes the orthography of the

Juvencus Manuscript

The Juvencus Manuscript (Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, MS Ff. 4.42; ) is one of the main surviving sources of Old Welsh. Unlike much Old Welsh, which is attested in manuscripts from later periods and in partially updated form, the Welsh ...

. Apparently, after being allowed in to the library at Cambridge to view the manuscript in 1702, Lhuyd took a penknife to Juvencus folios 25 and 26 and stole them, leaving knife marks on adjacent folios. The folios were eventually restored to the manuscript after being found among Lhuyd's personal possessions after his death.

This is followed by a small glossary of obsolete or obscure Welsh words from the 13th and 14th centuries, with English-translation equivalents.

There follows a discussion on the differences between Welsh dialects, and between Welsh, Cornish, and Breton.

Chapter III: Of the articles and Nouns

Lhuyd describes the Cornish definite and indefinite articles, and certain prepositions which can be joined to the definite article. This is followed by a synopsis of noun plural endings, abstract noun suffixes, agent noun suffixes, feminine noun suffixes, masculine and feminine grammatical genders, and lenition of feminine nouns after the definite article. Lhuyd then enumerates the most common plural suffixes, along with some nouns that form plurals by vowel change, with numerous examples.

Chapter IV: Of the Pronoun

In this chapter, Lhuyd describes Cornish personal, possessive, relative, interrogative, and demonstrative pronouns.

Chapter V: Of the Verb

Lhuyd begins this chapter by enumerating the various regular terminations of "infinitives". He then describes the main auxiliary verbs in Cornish, 'to be' 'to do', and 'to will'. Lhuyd describes how tenses of other verbs are formed using these auxiliaries combined with verbal particles. This is followed by a description of the formation of active and passive verbs, then a few irregular or defective verbs.

Chapter VI: Of the Participle

Lhuyd notes that there is no participle of the present tense in Cornish, and so instead uses the "infinitive" with the particle prefixed.

He describes the

preterperfect tense of verbs, being formed by addition of the suffix , sometimes with vowel affection.

Chapter VII: Of the Adverb and Interjection

Lhuyd describes the formation of adverbs with the particle or before an adjective, corresponding to English '-ly', so for example the adjective 'wise' can become an adverb, 'wisely'. Numerous other adverbs are here listed, categorized by their function, including adverbs of affirming, assembling, choosing, comparison, demonstration, denying, doubting, explication, number, place, quality, quantity, and time. Also, a limited number of interjections are given.

Chapter VIII: Of the Conjunction

Various Cornish conjunctions are listed, categorized by functions including copulative, conditional, discretive, disjunctive, causal, exceptive, adversative, and elective.

Chapter IX: Of the Preposition

Having previously discussed prepositions inflected for person, Lhuyd here discusses a number of independent prepositions. He also describes various prefixes, including 'over-', the reflexive prefix 'self-', and the negating prefix 'without; sans-; -less'.

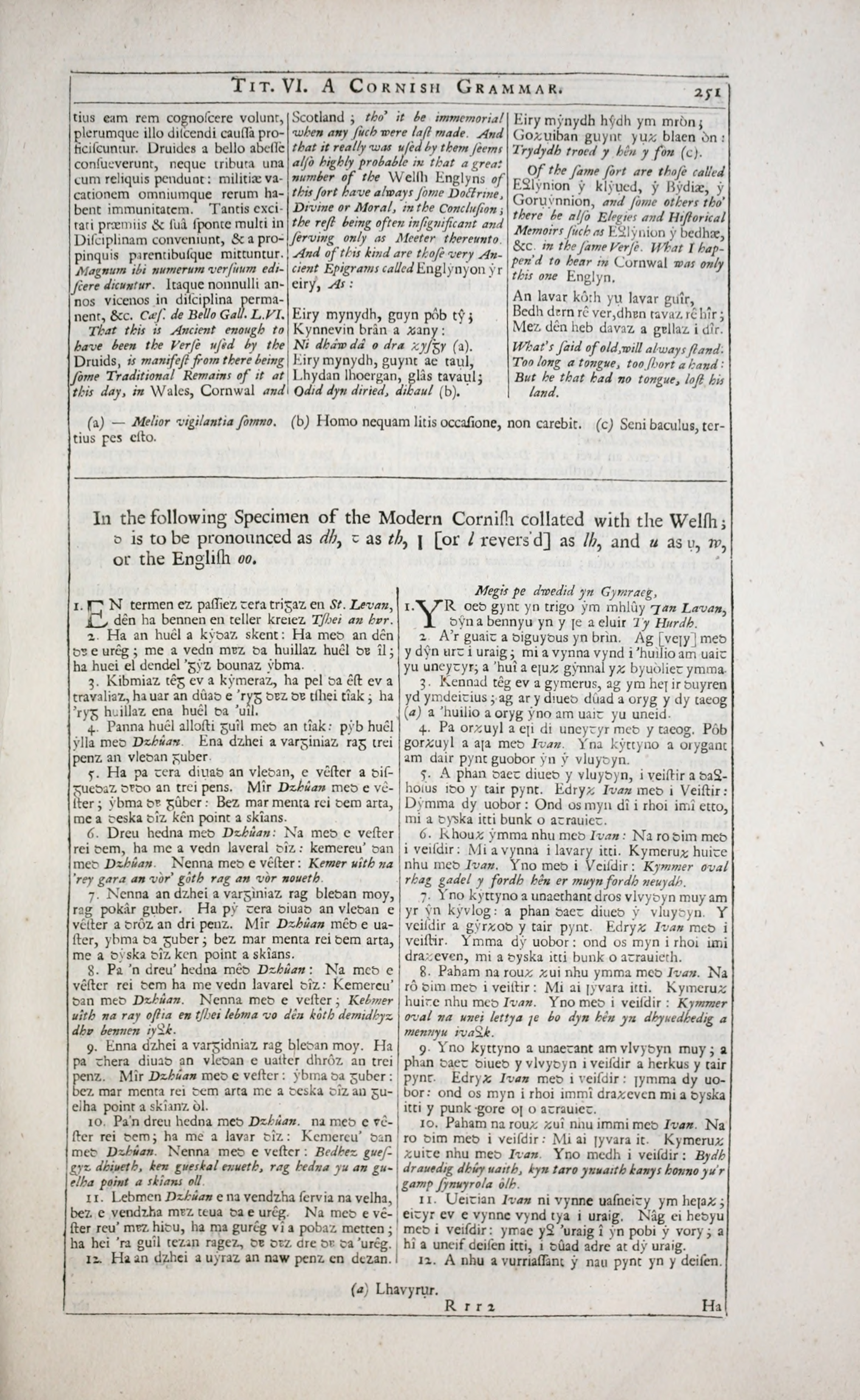

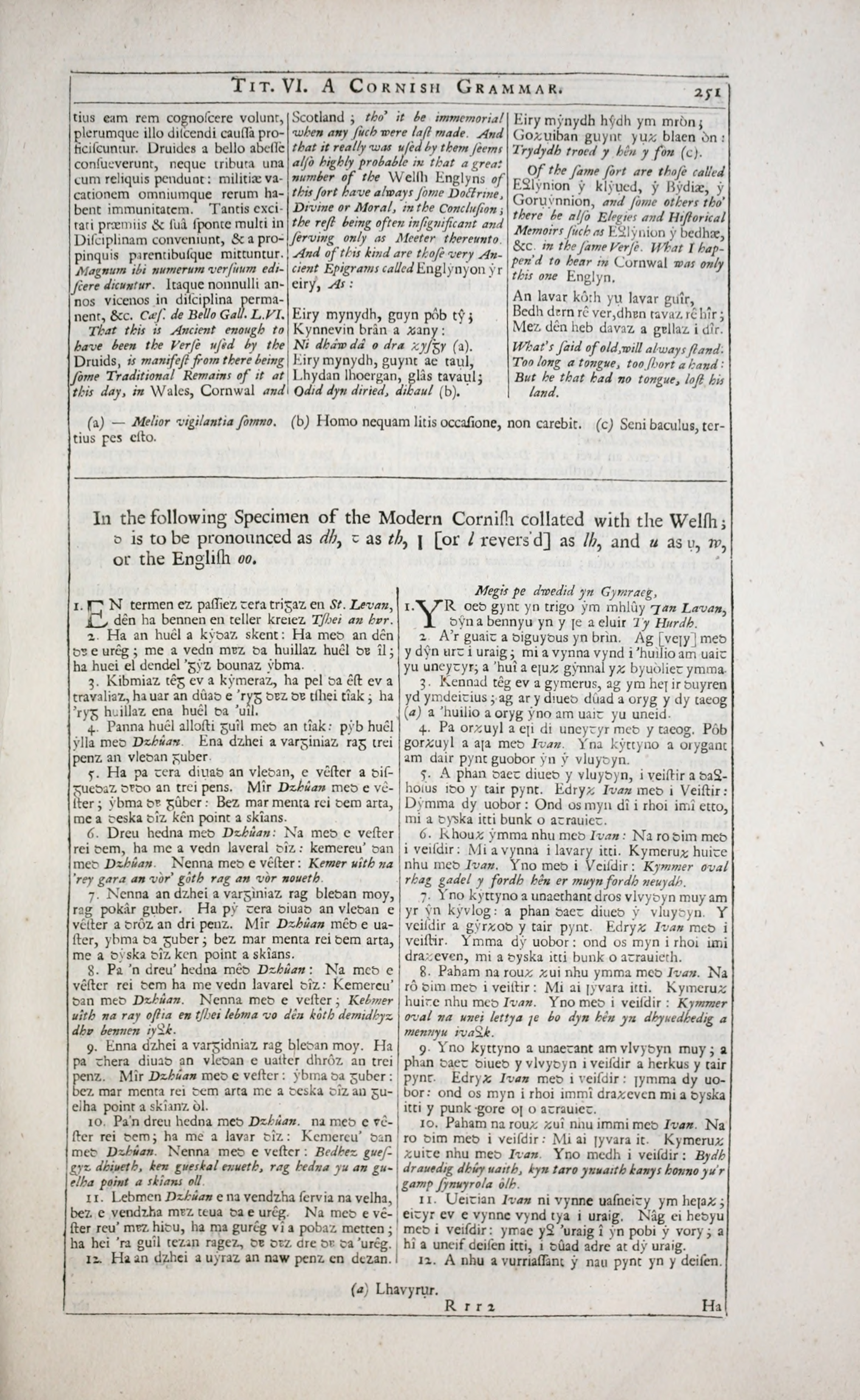

Chapter X: Some Proprieties of Phrase with some Notes omitted in the Foregoing Chapters, and a Specimen of the modern Cornish Collated with the Welsh

Lhuyd describes some Cornish idioms, as well as certain peculiarities of Cornish syntax and lexicon.

He also talks about the , a traditional Cornish and Welsh short verse form. He speculates that this may have been the ancient verse form used by the

druid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking priestly class in ancient Celtic cultures. The druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no wr ...

s. He includes the only he heard while in Cornwall, along with a loose translation:

This chapter includes a complete transcription of the only surviving Cornish-language folk tale, 'John of the House of the Ram'.

Lhuyd lists the parishes in west Cornwall where people were still speaking Cornish.

Title VII: ''Antiqua Britanniae lingua scriptorum quae non impressa sunt, Catalogus''

A catalogue and evaluation of medieval "British" (Welsh) manuscripts.

Title VIII: An essay towards a British etymologicon

Written by David Parry, one of Lhuyd's assistants, this title features a section with English headwords, followed by a wordlist of Latin

lemmata,

glossed

A gloss is a brief notation, especially a marginalia, marginal or interlinear gloss, interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text or in the reader's language if that is different.

A collec ...

with basic vocabulary from various European languages.

Title IX: A brief introduction to the Irish or ancient Scotish language

Based mainly on the first printed grammar of the Irish language by , with some additions.

Title X: ''Focloir Gaoidheilige-Shagsonach no Bearladoir Scot-Samhuil'': An Irish–English dictionary

A dictionary consisting of more than ten thousand

lemmata. Numerous Irish texts and dictionaries, including 's , was used to compile this title.

Postliminary sections

Finally, the book concludes with an index, abbreviations, and a list of

errata

An erratum or corrigendum (: errata, corrigenda) (comes from ) is a correction of a published text. Generally, publishers issue an erratum for a production error (i.e., an error introduced during the publishing process) and a corrigendum for an a ...

.

Reception

Criticism of Lhuyd's ''Glossography'' began even before publication, leading Lhuyd to defend his work in the introduction. He remarks that his detractors suggested that no more than "half a dozen" or "half a score" would be interested in such a work. Lhuyd responds that an impartial critic would have to admit that there must be at least three or four hundred who would be interested.

The gentry of Wales were unimpressed, perhaps partly due to Lhuyd's orthography, which diverged greatly from the Welsh orthography of the time, and the intelligentsia of Paris were disappointed that the volume was not written in Latin. Additionally, the ''Glossography'' was a financial failure.

On the other hand, ''Glossography'' received praise and appreciation from contemporary English and Celtic scholars.

George Hickes George Hickes may refer to:

* George Hickes (divine) (1642–1715), English divine and scholar

* George Hickes (Manitoba politician) (born 1946), Canadian politician

* George Hickes (Nunavut politician) (born 1968/69), Canadian politician, son of t ...

, in a letter to Lhuyd, wrote that "so I doubt not but it will be very satisfactory to all men, who have a genius for antiquity, and the more learned and judicious they are, the more they will approve it, and be pleased with it."

Modern linguists regard ''Archæologia Britannica'' as a pioneering work in the fields of linguistics and Celtic studies.

David Quinn describes the work as "far ahead of its time", "sufficiently original to be the pioneer European work on the comparative philology of the Celtic languages", and "one of the bases on which the scientific study of Celtic philology was re-laid a century and a half later." Bivens describes it as an important contribution to the field which attempted to systematize phonological change in Celtic languages.

Alexandra Walsham

Alexandra Marie Walsham (born 4 January 1966) is an English-Australian academic historian. She specialises in early modern Britain and in the impact of the Protestant and Catholic reformations. Since 2010, she has been Professor of Modern Hist ...

describes it as a "scholarly landmark which first recognized the family relationship between the various Celtic languages". According to the Evans and Roberts edition, ''Glossography'' "gave etymology a rational basis in the conceptual framework of the seventeenth-century scientific thought and thereby set the comparative method on firmer ground". Stammerjohann describes it as "remarkable for its scope and its erudition" and a "monumental work" which exerted a "profound but covert influence on comparative philology in the 19th century", but also states that "the fanciful celtomania which became prevalent in the 18th century appears to have diminished its impact on the scientific study of language".

''Glossography'' has been described as "bringing together a whole set of lexicographal achievements". It included the first comparative glossary of the Celtic languages, the first Breton-English and Irish-English dictionaries ever printed, the first description of the dialects of Scottish Gaelic to be printed, and the first time any Manx appeared in print. Additionally it provides the only description of the traditional pronunciation of the Cornish language.

''Archæologia Britannica'' is notable for Lhuyd's use of a system of phonetic transcription, allowing easier comparison of possible cognates between languages, as well as for introducing specific criteria for establishing that two languages are related.

Lyle Campbell

Lyle Richard Campbell (born October 22, 1942) is an American scholar and linguist known for his studies of indigenous American languages, especially those of Central America, and on historical linguistics in general. Campbell is professor emeri ...

and

William Poser

William J. Poser is a Canadian- American linguist who is known for his extensive work with the historical linguistics of Native American languages, especially those of the Athabascan family.

He got his B.A. from Harvard in 1979 and his Ph.D. from ...

have praised Lhuyd's use of sound correspondence evidence in the book (including correspondences which are unsystematic), his comparison of multiple Indo-European languages, his extensive collection of cognates, his description of sound changes, and his opinion that regular sound correspondences, and not chance similarities, are good evidence that languages are genetically related. They note that Lhuyd partially identified

Grimm's law

Grimm's law, also known as the First Germanic Consonant Shift or First Germanic Sound Shift, is a set of sound laws describing the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) stop consonants as they developed in Proto-Germanic in the first millennium BC, first d ...

, before the work of

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He formulated Grimm's law of linguistics, and was the co-author of the ''Deutsch ...

and

Rasmus Rask

Rasmus Kristian Rask (; born Rasmus Christian Nielsen Rasch; 22 November 1787 – 14 November 1832) was a Danish linguist and philologist. He wrote several grammars and worked on comparative phonology and morphology. Rask traveled extensively ...

, and produced more sophisticated work than the later work of

William Jones.

Lhuyd in ''Archæologia Britannica'' established that the language of the was Cornish rather than Welsh, as had been previously thought. Walsham states that the included Cornish grammar and vocabulary "helped to lay foundations for the initiatives of

Thomas Tonkin

Thomas Tonkin (1678–1742) was a Cornish landowner and historian.

Early life

He was born at Trevaunance, St Agnes, Cornwall, and baptised in its parish church on 26 September 1678, was the eldest son of Hugh Tonkin (1652–1711), vice-warden o ...

and

Richard Polwhele

Richard Polwhele (6 January 1760 – 12 March 1838) was a Cornish clergyman, poet and historian of Cornwall and Devon.

Biography

Richard Polwhele's ancestors long held the manor of Treworgan, 4 3/4 miles south-east of Truro in Cornwall, w ...

and

Jenner's revival efforts."

Epilogue

Lhuyd died prematurely just two years after the publication of the ''Glossography'' in 1709, in his room at the Ashmolean Museum. His understudy, David Parry, having developed a drinking problem, died five years later in 1714. Lhuyd's manuscripts were sold by the University of Oxford in 1713 for £80, the amount of Lhuyd’s debts, to

Sir Thomas Sebright. Most of the manuscripts were then auctioned by

Sotheby's

Sotheby's ( ) is a British-founded multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine art, fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, an ...

in 1807 and subsequently destroyed in two separate fires.

Notes

References

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

Archæologia Britannica (1707) at Archive.orgEarly science in Oxford vol. XIV: Life and letters of Edward Lhwyd at Archive.orgPrying into every hole and corner : Edward Lhuyd in Cornwall in 1700 at Archive.org

Linguistics

Celtic languages

Academic works about linguistics

Grammar

Language comparison

{{DEFAULTSORT:Archæologia Britannica

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the identity of the Greek ''Keltoi'', and Latin ''Celtae'' and ''Galli'', were discussed by scholars, with various national groups claiming descent from the ancient 'Celts' of antiquity, with no modern understanding of Celts as a linguistic group related to speakers of Brittonic or Goidelic languages. By the end of the sixteenth century, European intellectuals had begun to seriously debate whether Welsh and Irish, for example, were related languages.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the identity of the Greek ''Keltoi'', and Latin ''Celtae'' and ''Galli'', were discussed by scholars, with various national groups claiming descent from the ancient 'Celts' of antiquity, with no modern understanding of Celts as a linguistic group related to speakers of Brittonic or Goidelic languages. By the end of the sixteenth century, European intellectuals had begun to seriously debate whether Welsh and Irish, for example, were related languages.  In 1693, Edward Lhuyd, an antiquarian, naturalist, botanist, geographer, and philologist, and recently appointed Keeper of the

In 1693, Edward Lhuyd, an antiquarian, naturalist, botanist, geographer, and philologist, and recently appointed Keeper of the  Having trained others to take on his duties at Oxford and collected some funding, Lhuyd, along with his three assistants, began his tour in May 1697, travelling through Gloucestershire and the Forest of Dean, and reaching Chepstow on 13 May.

After three months, Lhuyd arrived at

Having trained others to take on his duties at Oxford and collected some funding, Lhuyd, along with his three assistants, began his tour in May 1697, travelling through Gloucestershire and the Forest of Dean, and reaching Chepstow on 13 May.

After three months, Lhuyd arrived at  This title examines lexical and phonological correspondences in different languages, as well as semantic changes. In total this title consists of 24 linguistic observations, which Lhuyd later divides into 10 classes in a "summary of etymology". Lhuyd attaches special emphasis to this part of the volume, and accordingly places it at the beginning of the work.

He explains that it "consists wholly of Parallel Observations relating to the Origin of Dialects, the affinity of the British with other languages, and their correspondence to one another. What I aim'd at therein, was the shewing by a collection of examples methodized, that etymology is not, as a great many, till they have considered it with some application, are apt to be perswaded, a speculation merely groundless or conjectural."

Class I

Synopsis:

In "Observation I", for instance, he gives as an example, meaning 'fist' in Welsh and Irish, but 'hand' in Cornish and Breton.

Class II

Synopsis:

In "Observation II", he notes the many words in the Old Cornish Vocabulary (OCV) that are no longer understood by the Cornish, but still used by the Welsh. † 'a hermit' from the OCV is listed with an obelus as one example.

Class III

Synopsis:

"Observation III" includes examples of metathesis, such as Welsh , Cornish 'to buy'.

Class IV

"Transposition of Compounds."

In "Observation IV", Lhuyd describes transposition of compounds, such as Welsh 'squint-eyed' and Cornish , which "be but their corrupt pronunciation of the same word, transpos'd."

Class V

Syunopsis:

"Observation V" describes how initial vowels may be added to the beginning of words. "Observation VI" describes how

This title examines lexical and phonological correspondences in different languages, as well as semantic changes. In total this title consists of 24 linguistic observations, which Lhuyd later divides into 10 classes in a "summary of etymology". Lhuyd attaches special emphasis to this part of the volume, and accordingly places it at the beginning of the work.

He explains that it "consists wholly of Parallel Observations relating to the Origin of Dialects, the affinity of the British with other languages, and their correspondence to one another. What I aim'd at therein, was the shewing by a collection of examples methodized, that etymology is not, as a great many, till they have considered it with some application, are apt to be perswaded, a speculation merely groundless or conjectural."

Class I

Synopsis:

In "Observation I", for instance, he gives as an example, meaning 'fist' in Welsh and Irish, but 'hand' in Cornish and Breton.

Class II

Synopsis:

In "Observation II", he notes the many words in the Old Cornish Vocabulary (OCV) that are no longer understood by the Cornish, but still used by the Welsh. † 'a hermit' from the OCV is listed with an obelus as one example.

Class III

Synopsis:

"Observation III" includes examples of metathesis, such as Welsh , Cornish 'to buy'.

Class IV

"Transposition of Compounds."

In "Observation IV", Lhuyd describes transposition of compounds, such as Welsh 'squint-eyed' and Cornish , which "be but their corrupt pronunciation of the same word, transpos'd."

Class V

Syunopsis:

"Observation V" describes how initial vowels may be added to the beginning of words. "Observation VI" describes how  This title consists of a vocabulary arranged alphabetically with Latin headwords glossed with Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx translation equivalents, written in the phonetic transcription system devised by Lhuyd and introduced in the previous title.

This title consists of a vocabulary arranged alphabetically with Latin headwords glossed with Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx translation equivalents, written in the phonetic transcription system devised by Lhuyd and introduced in the previous title.

Lhuyd writes a preface in the Cornish language. He begins by apologising for the grammar to follow, being neither born in Cornwall nor having stayed there for more than four months. He states that the inhabitants of Cornwall could produce the grammar better than himself. He expresses the hope that "this poor work" might cause somebody else to produce something better. He explains how he acquired his knowledge of the Cornish language; from the inhabitants of the west of Cornwall, particularly in St. Just; by the help of gentlemen antiquaries, who provided him with Cornish words; and from three manuscripts given him by the Bishop of Exeter, Sir Jonathan Trelawney, from which he says he got "the best part" of his knowledge. He describes his discovery that the manuscript labelled was, in fact, a Cornish vocabulary.

Lhuyd describes changes in Cornish pronunciation over time based on the manuscripts he has studied, such as the development of pre-occlusion in the contemporary Cornish language, where they now "put the letter ''b'', before the letter ''m''", and "the letter ''d'', before the letter ''n''", palatalization of Old Cornish /t/ and /d/, and various other phonological features which distinguish Cornish from Welsh. Lhuyd expresses his view that Cornish is closer to Breton dialects than Welsh, which he suggests is due to Breton migration into Cornwall.

Lhuyd writes a preface in the Cornish language. He begins by apologising for the grammar to follow, being neither born in Cornwall nor having stayed there for more than four months. He states that the inhabitants of Cornwall could produce the grammar better than himself. He expresses the hope that "this poor work" might cause somebody else to produce something better. He explains how he acquired his knowledge of the Cornish language; from the inhabitants of the west of Cornwall, particularly in St. Just; by the help of gentlemen antiquaries, who provided him with Cornish words; and from three manuscripts given him by the Bishop of Exeter, Sir Jonathan Trelawney, from which he says he got "the best part" of his knowledge. He describes his discovery that the manuscript labelled was, in fact, a Cornish vocabulary.

Lhuyd describes changes in Cornish pronunciation over time based on the manuscripts he has studied, such as the development of pre-occlusion in the contemporary Cornish language, where they now "put the letter ''b'', before the letter ''m''", and "the letter ''d'', before the letter ''n''", palatalization of Old Cornish /t/ and /d/, and various other phonological features which distinguish Cornish from Welsh. Lhuyd expresses his view that Cornish is closer to Breton dialects than Welsh, which he suggests is due to Breton migration into Cornwall.