Antártica, Chile on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

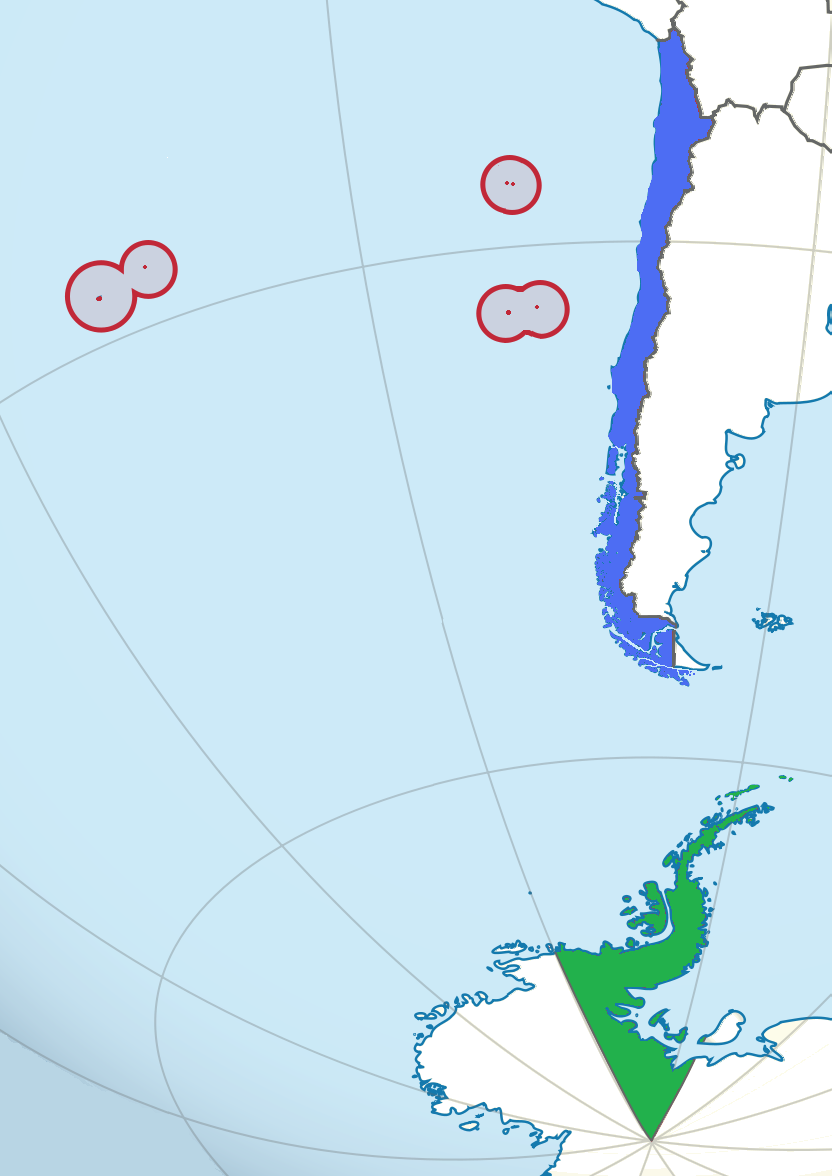

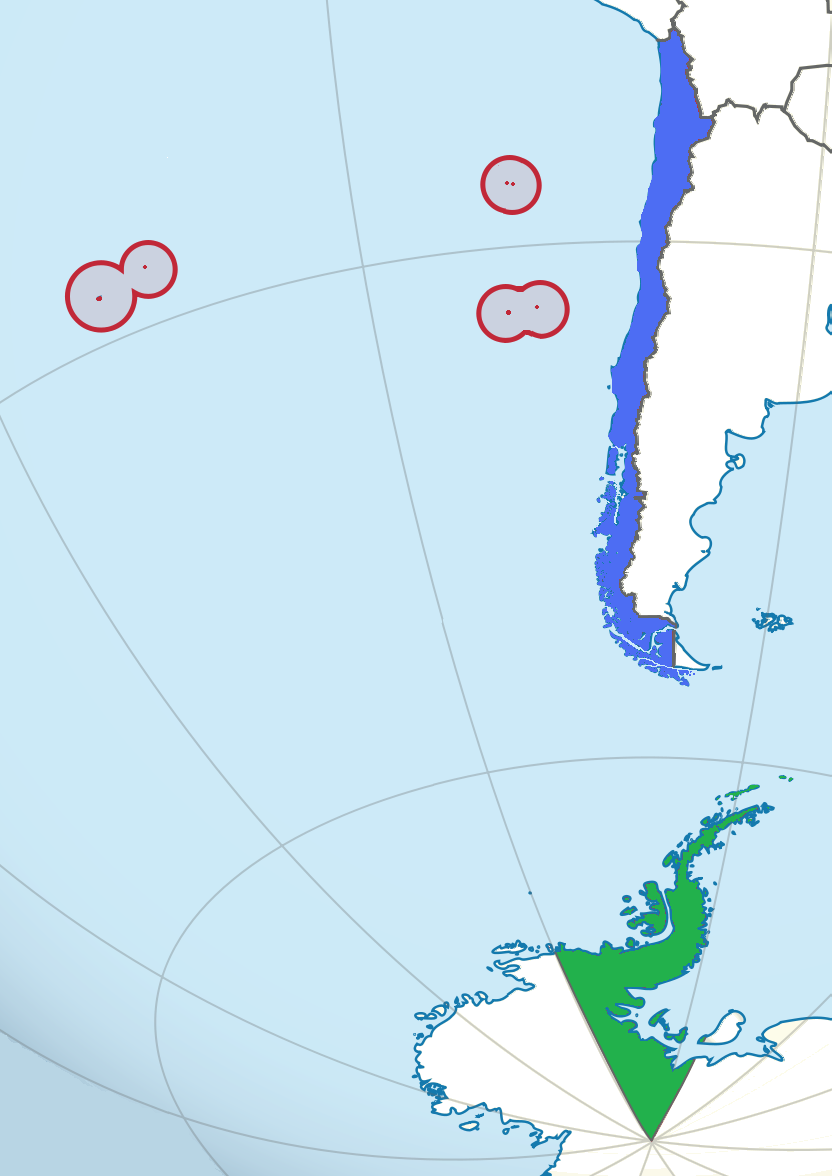

The Chilean Antarctic Territory, or Chilean Antarctica (, ), is a part of

After the colonies in the Americas had gained their independence, the new Spanish republics agreed amongst themselves to recognize the principle of ''

After the colonies in the Americas had gained their independence, the new Spanish republics agreed amongst themselves to recognize the principle of ''

On 14 January 1939,

On 14 January 1939,

West Antarctica

West Antarctica, or Lesser Antarctica, one of the two major regions of Antarctica, is the part of that continent that lies within the Western Hemisphere, and includes the Antarctic Peninsula. It is separated from East Antarctica by the Transan ...

and nearby islands claimed by Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

. It comprises the region south of 60°S latitude and between longitudes 53°W and 90°W, partially overlapping the Antarctic claims of Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

(Argentine Antarctica

Argentine Antarctica ( or ) is an area on Antarctica claimed by Argentina as part of its national territory. It consists of the Antarctic Peninsula and a triangular section extending to the South Pole, delimited by the 25th meridian west, 25 ...

) and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

(British Antarctic Territory

The British Antarctic Territory (BAT) is a sector of Antarctica claimed by the United Kingdom as one of its 14 British Overseas Territories, of which it is by far the largest by area. It comprises the region south of 60°S latitude and betwee ...

). It constitutes the ''Antártica

Antártica is a Chilean commune in Antártica Chilena Province, Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena Region, which covers all the Chilean Antarctic Territory (the territory in Antarctica claimed by Chile). It ranges from 53°W to 90°W and from t ...

'' commune of Chile.

The territory covers the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands located in the Drake Passage with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the n ...

, the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

(called O'Higgins Land——in Chile), and the adjacent islands of Alexander Island

Alexander Island, which is also known as Alexander I Island, Alexander I Land, Alexander Land, Alexander I Archipelago, and Zemlja Alexandra I, is the largest island of Antarctica. It lies in the Bellingshausen Sea west of Palmer Land, Antarcti ...

, Charcot Island and Ellsworth Land

Ellsworth Land is a portion of the Antarctica, Antarctic continent bounded on the west by Marie Byrd Land, on the north by the Bellingshausen Sea, on the northeast by the base of the Antarctic Peninsula, and on the east by the western margin of t ...

, among others. Its boundaries are defined by Decree 1747, issued on 6 November 1940 and published on 21 June 1955 by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

:

The commune of Antártica has an area of . If reckoned as Chilean national territory, it comprises 62.28% of the total area of the country. It is managed by the municipality of Cabo de Hornos

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

with a seat in Puerto Williams

Puerto Williams (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Port Williams") is a city, port and naval base on Navarino Island in Chile. It faces the Beagle Channel. It is the Capital city, capital of Antártica Chilena Province, the Chilean Antarctic Provin ...

in the Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South America, South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan.

The archipelago consists of the main is ...

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

(thus Antártica is the only commune in Chile not administered by a municipality of its own). It belongs to the province of Antártica Chilena, which itself is a part of the region of Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena. The commune was created on July 11, 1961, and was part of the Magallanes Province until 1974, when the Antártica Chilena Province was created.

Chilean sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

over the Chilean Antarctic Territory is exercised in conformity with the Antarctic Treaty

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antarctic comprises the continent of A ...

of 1961. This treaty established that Antarctic activities are to be devoted exclusively to peaceful purposes by the signatories and acceding countries, thereby freezing territorial disputes and preventing the construction of new claims or the expansion of existing ones.

The Chilean Antarctic Territory corresponds geographically to time zones UTC-4, UTC-5, and UTC-6, but as with Magallanes it uses UTC-3 year-round. Chile currently has 13 active Antarctic bases: 4 permanent, 5 seasonal, and 4 shelters.

History

Chilean Antarctica in colonial times

For many years,cartographers

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

and European explorers speculated about the existence of the ''Terra Australis Incognita

(Latin for ) was a hypothetical continent first posited in antiquity and which appeared on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries. Its existence was not based on any survey or direct observation, but rather on the idea that continental l ...

'', a landmass potentially of vast size located south of the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

and Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South America, South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan.

The archipelago consists of the main is ...

.

On 7 June 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in Tordesillas, Spain, on 7 June 1494, and ratified in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian (geography) ...

was signed between Spain and Portugal. This treaty gave rights to newly discovered territories to the two countries according to a line running from pole to pole; at 46° 37'W in the Spanish classical interpretation and farther west according to the Portuguese interpretation. The areas of Antarctica claimed by Chile today fall within the region granted to Spain by this original treaty. Though backed by the papal bull ''Ea quae pro bono pacis Ea quae pro bono pacis (''For the promotion of peace'') was a bull issued by Pope Julius II on 24 January 1506 by which the Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided the world unknown to Europeans between Portugal and Spain, but lacked papal approval as ...

'' in 1506, the Treaty of Tordesillas was not recognized by several other European powers, including France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and other Catholic states. For England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and other countries, the Antarctic areas were considered ''res nullius

''Res nullius'' is a term of Roman law meaning "things belonging to no one"; that is, property not yet the object of rights of any specific subject. A person can assume ownership of ''res nullius'' simply by taking possession of it ''( occupatio ...

'', a no man's land, subject to the occupation of any nation that had the courage and ambition to send people to claim them.

After the discovery of the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

in 1520, cartographers were convinced of the ancient theory of Claudio Tolomeo about the existence of a continent around the South Pole. Maps and charts were published on the basis that Tierra del Fuego was the discovered part of that continent.

In 1534, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

divided the South American territory of Spain into three governorates: New Castile or Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

(to Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish ''conquistador'', best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire.

Born in Trujillo, Cáceres, Trujillo, Spain, to a poor fam ...

), New Toledo or Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

(to Diego de Almagro

Diego de Almagro (; – July 8, 1538), also known as El Adelantado and El Viejo, was a Spanish conquistador known for his exploits in western South America. He participated with Francisco Pizarro in the Spanish conquest of Peru. While subduing ...

) and New León (to ) also known as the Magellanic Lands and subsequently extended to the Strait of Magellan. In 1539, a new governorate was formed south of New León called the ''Terra Australis'' under Pedro Sánchez de la Hoz

Pedro Sánchez de la Hoz or Pedro Sancho de la Hoz (1514 in Calahorra, La Rioja – 1547 in Santiago de Chile) was a Spanish merchant, conquistador and adelantado who served as secretary to Pizarro. In 1534 he obtained the rights of a south of t ...

. This consisted of the land south of the Strait of Magellan, i.e. Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South America, South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan.

The archipelago consists of the main is ...

, and onward unexplored land to the South Pole. At the time, the existence of the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile, Argentina, and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean (Scotia Sea) with the southeastern part of the Pa ...

was not known and Tierra del Fuego thought to be part of the Antarctic mainland.

In 1554, the conquistador Pedro de Valdivia

Pedro Gutiérrez de Valdivia or Valdiva (; April 17, 1497 – December 25, 1553) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' and the first royal governor of Chile. After having served with the Spanish army in Italy and Flanders, he was sent to South America in ...

, who led the Governorate of Chile, talked to the Council of the Indies

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

about giving the rights of New León and Terra Australis to Jeronimo de Alderete. After the death of Valdivia in the following year, Alderete became the governor of Chile and thereby claimed New León and Terra Australis for Chile. A Royal Decree of 1554 states:

Later, in 1558, the Royal Decree of Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

prompted the Chilean colonial government to "take ownership in our name from the lands and provinces that fall in the demarcation of the Spanish crown", referring to the land "across the Strait", i.e. Terra Australis.

One of the most important works of Spanish literature, the epic poem

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard to ...

''La Araucana

''La Araucana'' (also known in English as ''The Araucaniad'') is a 16th-century epic poem in Spanish by Alonso de Ercilla, about the Spanish Conquest of Chile. It was considered the national epic of the Captaincy General of Chile and one of the ...

'' by Alonso de Ercilla

Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga (7 August 153329 November 1594) was a Spanish soldier and poet, born in Madrid. While in Chile (1556–63) he fought against the Araucanians (Mapuche), and there he began the epic poem '' La Araucana'', considered one ...

, is considered by Chileans to give encouragement to their territorial claims in Antarctica. In the seventh stanza of his Canto I:

A circle located '27 degrees from the South Pole' corresponds to a latitude of 63 degrees south, on the southern side of the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile, Argentina, and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean (Scotia Sea) with the southeastern part of the Pa ...

and just north of the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

. However, ambiguity suggests that a misplaced Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

may be referred to.

There are other stories and maps, both Chilean and European, indicating that Terra Australis and Antarctica were claimed by the Captaincy General of Chile

The General Captaincy of Chile (''Capitanía General de Chile'' ), Governorate of Chile, or Kingdom of Chile, was a territory of the Spanish Empire from 1541 to 1818 that was, initially, part of the Viceroyalty of Peru. It comprised most of mod ...

for the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

.

In March 1603, the Spanish navigator Gabriel de Castilla sailed from Valparaiso entrusted with three ships belonging to the viceroy of Peru, Luis de Velasco y Castilla. The goal of this expedition was to repress the incursions of Dutch privateers in the Southern Seas as far as 64 degrees south latitude. No documents confirming the latitude reached or land sighted have been found in the Spanish archives. However, a story told by the Dutch sailor Laurenz Claesz (date unknown, but probably after 1607), gives interesting details. Claesz said:

In 1622, a Dutch document was published in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

stating that at 64 degrees south there was land which was "very high and mountainous, snow cover, like the country of Norway, all white, land. It seemed to extend to the Solomon Islands." This could be the first recorded sighting by a European of the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

. Other historians attribute the first sighting of Antarctic land to the Dutch mariner Dirk Gerritsz. According to his account, his ship was diverted from its course by a storm after passing through the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

as part of a Dutch expedition to the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

in 1599. Gerritsz may have sighted the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands located in the Drake Passage with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the n ...

, though there are doubts about his trustworthiness. Other authorities place the first sighting of mainland Antarctica as late as 27 January 1820 by an expedition of the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen

Faddey Faddeyevich Bellingshausen or Fabian Gottlieb Benjamin von Bellingshausen ( – ) was a Russian cartographer, explorer, and naval officer of Baltic German descent, who attained the rank of admiral. He participated in the first Russi ...

.

Open ocean south of South America was reported by the Spanish navigator Francisco de Hoces

Francisco de Hoces (died 1526) was a Spanish sailor who in 1525 joined the Loaísa Expedition to the Spice Islands as commander of the vessel ''San Lesmes''.

In January 1526, the ''San Lesmes'' was blown by a gale southwards from the eastern m ...

in 1525Oyarzun, Javier, ''Expediciones españolas al Estrecho de Magallanes y Tierra de Fuego'', 1976, Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispánica and by Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

in 1578. The existence of Drake Passage was confirmed when the Dutch navigator Willem Schouten

Willem Cornelisz Schouten (1625) was a Dutch navigator for the Dutch East India Company. He was the first to sail the Cape Horn route to the Pacific Ocean.

Biography

Willem Cornelisz Schouten was born around 1567 in Hoorn, Holland, Seve ...

became the first to sail around Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

en route to the East Indies in 1616. In 1772, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

explorer Captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

circumnavigated the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

.

19th century

After the colonies in the Americas had gained their independence, the new Spanish republics agreed amongst themselves to recognize the principle of ''

After the colonies in the Americas had gained their independence, the new Spanish republics agreed amongst themselves to recognize the principle of ''uti possidetis

''Uti possidetis'' is an expression that originated in Roman private law, where it was the name of a procedure about possession of land. Later, by a misleading analogy, it was transferred to international law, where it has had more than one mean ...

,'' meaning new states would have the same borders as their predecessor Spanish colonies. Thus the Republic of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes Mountains and the Pacific Oce ...

included all lands formerly belonging to the Captaincy General of Chile

The General Captaincy of Chile (''Capitanía General de Chile'' ), Governorate of Chile, or Kingdom of Chile, was a territory of the Spanish Empire from 1541 to 1818 that was, initially, part of the Viceroyalty of Peru. It comprised most of mod ...

, including claims over portions of Antarctica.

In 1815, the Argentine-Irish Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

William Brown launched a campaign to harass the Spanish fleet in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

and, when passing Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

with the Argentine vessels ''Hércules'' and ''Trinidad'', his ships were driven down into the Antarctic Sea beyond 65° south latitude. Brown's report indicated the presence of nearby land, though he did not see any portion of the continent and no landings were made.

On August 25, 1818, the government of Argentina, then called the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata, granted the first concessions for hunting earless seal

The earless seals, phocids, or true seals are one of the three main groups of mammals within the seal lineage, Pinnipedia. All true seals are members of the family Phocidae (). They are sometimes called crawling seals to distinguish them from th ...

s and penguin

Penguins are a group of aquatic flightless birds from the family Spheniscidae () of the order Sphenisciformes (). They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. Only one species, the Galápagos penguin, is equatorial, with a sm ...

s in Antarctica to Juan Pedro de Aguirre, who operated the ship ''Espíritu Santo'' based on Deception Island

Deception Island is in the South Shetland Islands close to the Antarctic Peninsula with a large and usually "safe" natural harbour, which is occasionally affected by the underlying active volcano. This island is the caldera of an active volc ...

. ''Espíritu Santo'' was joined by the American brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the l ...

''Hercilia''. The fact that the Argentine sealers were able to sail directly to the island can be regarded as evidence that its location was already known.

Between 1819 and 1821, the Russian ships ''Vostok'' and ''Mirny'', under the command of the German Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen

Faddey Faddeyevich Bellingshausen or Fabian Gottlieb Benjamin von Bellingshausen ( – ) was a Russian cartographer, explorer, and naval officer of Baltic German descent, who attained the rank of admiral. He participated in the first Russi ...

in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

n service, explored Antarctic waters, as already noted. In 1821, at 69°W 53'S, he sighted an island which he called Alexander I Land, after the Russian Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

. Although von Bellingshausen circumnavigated the continent twice, no member of his crew ever set foot on Antarctica.

In 1819, the British mariner William Smith William, Willie, Will, Bill, or Billy Smith may refer to:

Academics

* William Smith (Master of Clare College, Cambridge) (1556–1615), English academic

* William Smith (antiquary) (c. 1653–1735), English antiquary and historian of University C ...

rediscovered the South Shetland Islands, including King George Island. The American Nathaniel Palmer

Nathaniel Brown Palmer (August 8, 1799 – June 21, 1877) was an American seal hunter, explorer, sailing captain, ship designer, and a whale hunter. He gave his name to Palmer Land, Antarctica, which he explored in 1820 on his sloop ''Hero''. ...

spotted the Antarctic Peninsula that same year. Neither of them went ashore on the actual continental landmass. However, in 1821, Connecticut seal hunter John Davis reported setting foot on a southern land that he believed was a continent.

In 1823, James Weddell

James Weddell (24 August 1787 – 9 September 1834) was a British sailor, navigator and seal hunter who in February 1823 sailed to latitude of 74° 15′ S—a record 7.69 degrees or 532 statute miles south of the Antar ...

claimed to have discovered the sea that now bears his name, lying inside the Antarctic Circle to the east of the Antarctic peninsula. The hunting of baleen whales and South American sea lion

The South American sea lion (''Otaria flavescens'', formerly ''Otaria byronia''), also called the southern sea lion and the Patagonian sea lion, is a sea lion found on the western and southeastern coasts of South America. It is the Monotypic ta ...

s began to increase in the following years. In 1831, Chile's liberator Bernardo O'Higgins

Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme (; 20 August 1778 – 24 October 1842) was a Chilean independence leader who freed Chile from Spanish rule in the Chilean War of Independence. He was a wealthy landowner of Basque people, Basque-Spanish people, Spani ...

wrote to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, saying:

In 1856, a treaty of friendship between Chile and Argentina recognized boundaries and was enacted ''uti possidetis juris''. The growth of Chilean settlements in the Magallanes Region

The Magallanes Region (), officially the Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena Region () or Magallanes and the Chilean Antarctica Region in English, is one of Chile's 16 first order administrative divisions. It is the southernmost, largest, and sec ...

and especially the city of Punta Arenas

Punta Arenas (, historically known as Sandy Point in English) is the capital List of cities in Chile, city of Chile's southernmost Regions of Chile, region, Magallanes Region, Magallanes and Antarctica Chilena. Although officially renamed as ...

allowed the founding of companies for the hunting and exploitation of whales in the Antarctic seas, which required authorization from the Chilean government. In 1894, control over the exploitation of marine resources south of latitude 54 degrees south was given to the Punta Arenas Municipality.

20th century

In the early years of the 20th century, interest in the Antarctic territories increased. Some expeditions to Antarctica asked permission from the government of Chile, among these being those ofOtto Nordenskjöld

Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjöld (6 December 1869 – 2 June 1928) was a Swedish geologist, geographer, and polar explorer.

Early life

Nordenskjöld was born in Hässleby in Småland in eastern Sweden, in a family that included his maternal unc ...

in 1902 and of Robert F. Scott in 1900. Chile also granted mining permits, such as that conferred on 31 December 1902 by Decree No. 3310 allowing Pedro Pablo Benavides to lease the Diego Ramírez Islands

The Diego Ramírez Islands () are a small group of Chilean subantarctic islands located at the southernmost extreme of South America.

History

The islands were sighted on 12 February 1619 by the Spanish Garcia de Nodal expedition, and named a ...

and San Ildefonso

San Ildefonso (), La Granja (), or La Granja de San Ildefonso, is a town and municipality in the Province of Segovia, in the Castile and León autonomous region of central Spain.

It is located in the foothills of the Sierra de Guadarrama moun ...

.

In 1906, several decrees were promulgated

Promulgation is the formal proclamation or the declaration that a new statutory or administrative law is enacted after its final approval. In some jurisdictions, this additional step is necessary before the law can take effect.

After a new law i ...

, including some from the National Congress of Chile

The National Congress of Chile () is the legislative branch of the Republic of Chile. According to the current Constitution ( Chilean Constitution of 1980), it is a bicameral organ made up of a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate. Established by l ...

, offering mining permits in the Antarctic area. In that same year, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Chile mentioned on September 18 that the delimitation of Chilean Antarctic territory would be the subject of a preliminary investigation. On 10 June 1907, Argentina formally protested and asked for mutual recognition of Antarctic territories. There was work on a treaty to more concretely define territories in the region, but it was never signed.

On 8 May 1906, the Whaling Society of Magallanes was created with a base in Punta Arenas. On 1 December, the society was authorized to expand its territory to the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands located in the Drake Passage with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the n ...

, as allowed by Decree No. 1314 of the governor of Magallanes. The group expanded to Whalers Bay on Deception Island

Deception Island is in the South Shetland Islands close to the Antarctic Peninsula with a large and usually "safe" natural harbour, which is occasionally affected by the underlying active volcano. This island is the caldera of an active volc ...

, where they hoisted the Chilean flag and established a coaling station. This area was visited by Jean-Baptiste Charcot

Jean-Baptiste Étienne Auguste Charcot, better known in France as Commandant Charcot, (15 July 1867 in Neuilly-sur-Seine near Paris – 16 September 1936 at sea (30 miles north-west of Reykjavik, Iceland), was a French scientist, medical doctor ...

in December 1908 to replenish coal. The site was manned during the summer seasons until 1914.

On 21 July 1908, however, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

had officially claimed sovereignty over all lands between 20°W and 80°W and south of 50°S, including the Falkland Islands and South Georgia (although not, of course, the South American mainland). In 1917, the northern boundary of the claim was moved to 58°S, and in 1962 to the parallel 60°S.

In 1914, Anglo-Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarcti ...

began an expedition to cross the South Pole from the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha C ...

to the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

, known as the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Ernest Shackleton, Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the ...

. With the ship ''Endurance

Endurance (also related to sufferance, forbearance, resilience, constitution, fortitude, persistence, tenacity, steadfastness, perseverance, stamina, and hardiness) is the ability of an organism to exert itself and remain active for a ...

'' he sailed into the Weddell Sea, but the weather worsened dramatically and the ''Endurance'' was trapped for weeks and ultimately crushed by the ice. There followed an episode of bravery involving both Britain and Chile. Shackleton and his crew dragged three lifeboats over the frozen sea until they came to open water again, then sailed to the desolate Elephant Island

Elephant Island is an ice-covered, mountainous island off the coast of Antarctica in the outer reaches of the South Shetland Islands, in the Southern Ocean. The island is situated north-northeast of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, west-so ...

at the very northern tip of the Antarctic peninsula. Shackleton and a picked crew then sailed one boat to South Georgia Island

South Georgia is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean that is part of the British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. It lies around east of the Falkland Islands. ...

where help was obtained. However, three attempts to reach the rest of the expedition on Elephant Island were turned back by pack ice. Finally, in Punta Arenas

Punta Arenas (, historically known as Sandy Point in English) is the capital List of cities in Chile, city of Chile's southernmost Regions of Chile, region, Magallanes Region, Magallanes and Antarctica Chilena. Although officially renamed as ...

, Shackleton obtained the help of the Chilean navy tugboat '' Yelcho'', captained by Luis Pardo Villalón, which managed to rescue the remaining survivors. On 4 September 1916, they were received at the port of Punta Arenas as heroes. Captain Pardo's feat, sailing with temperatures close to −30 °C (−22 °F) and a stormy sea of icebergs

An iceberg is a piece of fresh water ice more than long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". Much of an ic ...

, won him national and international recognition.

Sovereignty and the Antarctic Treaty System

On 14 January 1939,

On 14 January 1939, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

declared its territorial claims on Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land () is a roughly region of Antarctica Territorial claims in Antarctica, claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20th meridian west, 20° west, specifically the Caird Coast, ...

between 0° and 20°W. This prompted President Pedro Aguirre Cerda

Pedro Abelino Aguirre Cerda (; February 6, 1879 – November 25, 1941) was a Chilean political figure, educator, and lawyer who served as the 22nd president of Chile from 1938 until his death in 1941. He was Political moderate, moderate.

A me ...

of Chile to encourage the definition of Chilean territory in the Antarctic. Following Decree No. 1541 on 7 September, he organized a commission which set the bounds of Chilean territory according to the theory of polar areas, taking into account geographical, historical, legal, and diplomatic precedents. The bounds were formalized by Decree No. 1747, enacted on 6 November 1940, and published on 21 June 1955. The Chilean claim extended no farther east than the 53°W meridian; thus the claim excluded the South Orkney Islands

The South Orkney Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands, islands in the Southern Ocean, about north-east of the tip of the Antarctic PeninsulaPunta Dúngeness, the southernmost point of mainland Argentina. On 2 September 1946, Decree No. 8944 expanded the bundary for the Argentine Antarctic Sector, widening this sector out to 74° W. Chile began to exercise sovereignty in the Antarctic area in 1947, beginning with the establishment of Sovereignty Base, currently known as

Due to the geographical characteristics of the Antarctic Peninsula, which the Chilean Antarctic Territory completely encompasses, the territory has some of the best conditions for human settlement in Antarctica.

There are four Chilean permanent bases operating throughout the year, while an additional five remain open only during the

Due to the geographical characteristics of the Antarctic Peninsula, which the Chilean Antarctic Territory completely encompasses, the territory has some of the best conditions for human settlement in Antarctica.

There are four Chilean permanent bases operating throughout the year, while an additional five remain open only during the

* Estación Polar Científica Conjunta "Glaciar Unión" ; ''(Scientific Polar Station Joint "Union Glacier"'' in English'')'' incorporates Teniente Arturo Parodi Alister Base and Antonio Huneeus Antarctic Base which moved to the new location. It is located in the

* Estación Polar Científica Conjunta "Glaciar Unión" ; ''(Scientific Polar Station Joint "Union Glacier"'' in English'')'' incorporates Teniente Arturo Parodi Alister Base and Antonio Huneeus Antarctic Base which moved to the new location. It is located in the

Cristian Donoso and Claudio Scaletta completes historic journey in Antarctica

/ref> * Luis Risopatrón Base (formerly "Copper Mine Naval Refuge") is a summer station of the Chilean Navy at

File:Base Pedro Aguirre Cerda1.JPG, Pedro Aguirre Cerda Base (Closed Today), in

Gobierno Regional Magallanes y Antártica Chilena

Official website *

Gobernación Provincia de Antártica Chilena

Official website *

Chilean Antarctic Institute

Official website *

Chilean Sea Document *

Municipality of Cape Horn

{{DEFAULTSORT:Antartica Chilean Antarctic Territory, Territorial claims in Antarctica Magallanes Region States and territories established in 1940 1940 establishments in Antarctica

Arturo Prat

Agustín Arturo Prat Chacón (; April 3, 1848 – May 21, 1879) was a Chilean Navy officer and lawyer. He was killed in the Battle of Iquique, during the War of the Pacific. During his career, Prat had taken part in several naval engagements, in ...

, in the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands located in the Drake Passage with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the n ...

. The following year, as a way of establishing the Chilean claims, Chilean President Gabriel Gonzalez Videla

In the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), Gabriel ( ) is an archangel with the power to announce God's will to mankind, as the messenger of God. He is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament and the Quran. Many Chris ...

personally opened Base General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme

Base General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme, also Base Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme, or shortly Bernardo O'Higgins, named after Bernardo O'Higgins, is a permanently staffed Chilean research station in Antarctica and the capital of ...

on the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

. This was the first official visit of a head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

to Antarctica.

On March 4, 1948, Chile and Argentina signed an agreement on mutual protection and legal defense of their Antarctic territorial rights, agreeing to act in concert to defend the rights of both countries in Antarctica, while leaving the delimitation of their territories for a later date. The governments agreed that "between the meridians 25° and 90° west longitude from Greenwich, indisputable sovereign rights are recognized by Chile and Argentina", stating that "Chile and Argentina have unquestionable rights of sovereignty in the polar area called American Antarctica" ( in Spanish).

In 1953, the representative of he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

at the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

presented a project for the internationalization of Antarctica. The Chilean ambassador in New Delhi

New Delhi (; ) is the Capital city, capital of India and a part of the Delhi, National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the Government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Parliament ...

, Miguel Serrano

Miguel Joaquín Diego del Carmen Serrano Fernández (10 September 1917 – 28 February 2009), was a Chilean diplomat, writer, neopagan occultism, occultist, defender of a doctrine that supposedly would be true Christianity, the "Kristianism" an ...

, however, persuaded the Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

to withdraw the proposal. On 4 May 1955, the United Kingdom filed two lawsuits against Argentina and Chile before the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

, to declare invalid the claims of sovereignty of the two countries in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic areas. Chilean Law No. 11486 of June 17, 1955, added the Chilean Antarctic Territory to the Province of Magallanes, which on 12 July 1974 became the Region of Magallanes and Chilean Antarctica. On 15 July 1955, the Chilean government formally rejected the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice in this case, and on 1 August the Argentine government followed suit. The United Kingdom submitted its written argument on 16 March 1956.

On 28 February 1957, Argentine Decree Law No. 2129 established the limits of their claim as the meridians 25° and 74° W and the parallel 60° S. This continuied to overlap the territory claimed by Chile. In 1958, the U.S. president, Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, invited Chile to the International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY; ), also referred to as the third International Polar Year, was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War w ...

Conference in an attempt to resolve the claiming issues. On 1 December 1959, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

signed the Antarctic Treaty

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antarctic comprises the continent of A ...

.

In July 2003, Chile and Argentina began maintaining a joint emergency shelter called '' Abrazo de Maipú'' in the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

, halfway between Base General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme

Base General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme, also Base Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme, or shortly Bernardo O'Higgins, named after Bernardo O'Higgins, is a permanently staffed Chilean research station in Antarctica and the capital of ...

, operated by Chile, and Esperanza Base

Esperanza Base (, 'Hope Base') is a permanent, all-year-round Argentine research station in Hope Bay, Trinity Peninsula (in Graham Land on the Antarctic Peninsula). It is the only civilian settlement on the Antarctic mainland (the Chilean Vil ...

, maintained by Argentina. It was closed in 2010.

In February 2022, Chile submitted its second partial report regarding the Western Extended Continental Shelf of the Chilean Antarctic Territory. In August of the same year, it delivered oral presentations for both partial reports during the 55th Session of the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in New York.

In 2023, the Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service of the Chilean Navy made available an illustrative graphic showing all the maritime areas claimed by the country, including those of the continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an islan ...

and extended continental shelf The extended continental shelf, scientific continental shelf, or outer continental shelf, refers to a type of maritime area, established as a geo-legal paradigm by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Through the process kno ...

of the Chilean Antarctic Territory.

In January 2025, President Gabriel Boric

Gabriel Boric Font (; born 11 February 1986) is a Chilean politician and the President of Chile since 2022. He previously served two four-year terms as a deputy in the Chamber of Deputies of Chile, Chamber of Deputies.

Boric first gained prom ...

became the first head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

to visit the South Pole and the third he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...head of government

In the Executive (government), executive branch, the head of government is the highest or the second-highest official of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presid ...

, being the first from Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

. Prime Minister Helen Clark

Helen Elizabeth Clark (born 26 February 1950) is a New Zealand politician who served as the 37th prime minister of New Zealand from 1999 to 2008 and was the administrator of the United Nations Development Programme from 2009 to 2017. She was ...

from New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

went in 2007 and Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg

Jens Stoltenberg (; born 16 March 1959) is a Norwegian politician from the Labour Party. Since 2025, he has been the Minister of Finance in the Støre Cabinet. He has previously been the prime minister of Norway and secretary general of NATO.

...

from Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

went in 2011.

The Antarctic Treaty

The treaty states: * Antarctica is aWorld Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

.

* The Antarctic territory is to be reserved for peaceful purposes and cannot be used for war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

or for military or naval installations.

* The signatory countries of the treaty have the right to establish bases for scientific purposes (marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

, seismology

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes (or generally, quakes) and the generation and propagation of elastic ...

, volcanology

Volcanology (also spelled vulcanology) is the study of volcanoes, lava, magma and related geology, geological, geophysical and geochemistry, geochemical phenomena (volcanism). The term ''volcanology'' is derived from the Latin language, Latin ...

, etc.).

* Territorial claims are to be frozen, ensuring each signatory nation the ''status quo'' for the duration of the treaty.

* In this territory, even for peaceful purposes, there can be no nuclear tests and toxic waste cannot be left.

Geography and climate

Land elevation and features

The Chilean Antarctic Territory covers an area of . The thickness of ice covering the land can exceed in some areas in the interior of the continent, and the extent of sea ice varies dramatically with the seasons. Chilean Antarctic Territory is located predominantly in Lesser Antarctica orWest Antarctica

West Antarctica, or Lesser Antarctica, one of the two major regions of Antarctica, is the part of that continent that lies within the Western Hemisphere, and includes the Antarctic Peninsula. It is separated from East Antarctica by the Transan ...

, which includes the Antarctic Peninsula, known in Chile as O'Higgins Land. Forming the spine of this peninsula are the mountains of the Antartandes, which are a continuation of the Andes mountains

The Andes ( ), Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long and wide (widest between 18°S ...

. Mount Hope is the highest mountain in the Antartandes, reaching in altitude. The Antartandes clearly differentiate three geographic areas in O'Higgins Land: the western slope, the central plateau and the eastern slope.

To the southwest of the Antarctic Peninsula, within the land claimed by Chile, are the highest summits of the Antarctic continent, a part of the Sentinel Range

The Sentinel Range is a major mountain range situated northward of Minnesota Glacier and forming the northern half of the Ellsworth Mountains in Antarctica. The range trends NNW-SSE for about and is wide. Many peaks rise over and Vinson Mass ...

including the Vinson Massif

Vinson Massif () is a large mountain massif in Antarctica that is long and wide and lies within the Sentinel Range of the Ellsworth Mountains. It overlooks the Ronne Ice Shelf near the base of the Antarctic Peninsula. The massif is located ab ...

at , Mount Tyree

Mount Tyree (4852m) is the second highest mountain of Antarctica located 13 kilometres northwest of Mount Vinson (4,892 m), the highest peak on the continent. It surmounts Patton Glacier to the north and Cervellati Glacier to the ...

at and Mount Shinn

Mount Shinn is a mountain 4,661 meters in elevation, standing 6 km (4 miles) southeast of Mount Tyree in the Sentinel Range, Ellsworth Mountains in Antarctica. It surmounts Ramorino Glacier to the north, upper Crosswell Glacier to ...

at in height.

The claimed territory has a subglacial lake

A subglacial lake is a lake that is found under a glacier, typically beneath an ice cap or ice sheet. Subglacial lakes form at the boundary between ice and the underlying bedrock, where liquid water can exist above the lower melting point of ic ...

, the Lake CECs, which was discovered in January 2014 by scientists of Centro de Estudios Científicos

Centro de Estudios Científicos (CECs; Center for Scientific Studies) is a private, non-profit corporation based in Valdivia, Chile, devoted to the development, promotion and diffusion of scientific research.

History

CECs research areas inclu ...

headquartered in Valdivia, Chile

Valdivia (; Mapuche language, Mapuche: Ainil) is a List of cities in Chile, city and Communes of Chile, commune in Southern Chile, southern Chile, administered by the Municipality of Valdivia. The city is named after its Organizational founder, ...

, and was validated in May 2015 with the publication of its existence in the journal ''Geophysical Research Letters

''Geophysical Research Letters'' is a biweekly peer-reviewed scientific journal of geoscience published by the American Geophysical Union that was established in 1974. The editor-in-chief iKristopher Karnauskas

Aims and scope

The journal aims for ...

''. The lake has an estimated area of , lies deep under the ice and is located in a buffer zone of three major glaciers, in an area designated low-disturbance with ice motion almost nonexistent. There is a hypothesis

A hypothesis (: hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. A scientific hypothesis must be based on observations and make a testable and reproducible prediction about reality, in a process beginning with an educated guess o ...

that it could have life; this would have developed in conditions of extreme isolation and the lake is encapsulated.

Climate

Coastal areas north of theAntarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

and in the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands located in the Drake Passage with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the n ...

, have a subarctic climate

The subarctic climate (also called subpolar climate, or boreal climate) is a continental climate with long, cold (often very cold) winters, and short, warm to cool summers. It is found on large landmasses, often away from the moderating effects of ...

or tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

, that is, the average temperature in the warmest month exceeds 0 °C (32 °F) and much is permafrost

Permafrost () is soil or underwater sediment which continuously remains below for two years or more; the oldest permafrost has been continuously frozen for around 700,000 years. Whilst the shallowest permafrost has a vertical extent of below ...

. The rest of the territory is under the regime of a polar climate

The polar climate regions are characterized by a lack of warm summers but with varying winters. Every month a polar climate has an average temperature of less than . Regions with a polar climate cover more than 20% of the Earth's area. Most of ...

. Precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls from clouds due to gravitational pull. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, rain and snow mixed ("sleet" in Commonwe ...

in the territory is relatively rare and decreases towards the South Pole, creating polar desert

Polar deserts are the regions of Earth that fall under an ice cap climate (''EF'' under the Köppen classification). Despite rainfall totals low enough to normally classify as a desert, polar deserts are distinguished from true deserts (' or ' un ...

conditions.

Population

The Antártica Commune had a population of 150 inhabitants on the Chilean bases according to a census conducted nationwide in 2012, corresponding to 54 civilians and 96 military. These people were mostly members of theChilean Air Force

The Chilean Air Force () is the air force of Chile and branch of the Chilean military.

History

The first step towards the current FACh is taken by Lieutenant Colonel, Teniente Coronel training as a pilot in France. Although a local academy was c ...

and their families, who lived predominantly in Villa Las Estrellas

Villa Las Estrellas (; Spanish language, Spanish for ''The Stars Village'' or ''Hamlet of the Stars'') is a permanently inhabited outpost on King George Island (South Shetland Islands), King George Island within the Chilean Antarctica, Antar ...

. This town, located next to the Presidente Eduardo Frei Montalva Antarctic base on King George Island, was opened on 9 April 1984 and has an airport, a bank, a school and child care, a hospital, a supermarket, mobile telephony and television.

In 1984 the first Antarctic Chilean, Juan Pablo Camacho Martino, was born in Villa Las Estrellas. As of 2024, a total of three Chileans have been born in the Chilean Antarctic Territory; Gisella Cortés Rojas was born on 2 December 1984, and Ignacio Miranda Lagunas on 23 January 1985. They do not know each other and have not returned to Antarctica. As of 2024, Ignacio is the most recent Antarctic baby, although the development of tourism has increased explosively through airplanes and cruise ships that depart from Punta Arenas

Punta Arenas (, historically known as Sandy Point in English) is the capital List of cities in Chile, city of Chile's southernmost Regions of Chile, region, Magallanes Region, Magallanes and Antarctica Chilena. Although officially renamed as ...

or Ushuaia

Ushuaia ( , ) is the capital city, capital of Tierra del Fuego Province, Argentina, Tierra del Fuego, Antártida e Islas del Atlántico Sur Province, Argentina. With a population of 82,615 and a location below the 54th parallel south latitude, U ...

, with most of the flights arriving at King George Island handled by Dap Group.

Bases, stations, shelters and settlements

Due to the geographical characteristics of the Antarctic Peninsula, which the Chilean Antarctic Territory completely encompasses, the territory has some of the best conditions for human settlement in Antarctica.

There are four Chilean permanent bases operating throughout the year, while an additional five remain open only during the

Due to the geographical characteristics of the Antarctic Peninsula, which the Chilean Antarctic Territory completely encompasses, the territory has some of the best conditions for human settlement in Antarctica.

There are four Chilean permanent bases operating throughout the year, while an additional five remain open only during the summer

Summer or summertime is the hottest and brightest of the four temperate seasons, occurring after spring and before autumn. At or centred on the summer solstice, daylight hours are the longest and darkness hours are the shortest, with day ...

(December – March) with four seasonal shelters.

The largest population center is located on King George Island at Base Presidente Eduardo Frei Montalva

Base Presidente Eduardo Frei Montalva is the most important Antarctic base of Chile. It is located at Fildes Peninsula, an ice-free area, in front of Fildes Bay, at the west end of King George Island, South Shetland Islands. Situated alongside t ...

, which has an airstrip, a meteorological center (the Meteorological Center President Frei) and the Villa Las Estrellas

Villa Las Estrellas (; Spanish language, Spanish for ''The Stars Village'' or ''Hamlet of the Stars'') is a permanently inhabited outpost on King George Island (South Shetland Islands), King George Island within the Chilean Antarctica, Antar ...

. Belonging to Chile, this enclave forms the nucleus for important logistical support to other countries with scientific bases on King George Island.

The Chilean Antarctic Institute

Chilean may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Chile, a country in South America

* Chilean people

* Chilean Spanish

* Chilean culture

* Chilean cuisine

* Chilean Americans

See also

*List of Chileans

This is a list of Chileans who ar ...

(INACH), under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

, operates the Profesor Julio Escudero Base on King George Island, which is the chief Chilean scientific research center in Antarctica.

The Chilean Navy

The Chilean Navy () is the naval warfare service branch of the Chilean Armed Forces. It is under the Ministry of National Defense (Chile), Ministry of National Defense. Its headquarters are at Edificio Armada de Chile, Valparaiso.

History

Ori ...

provides logistic and other support for scientific and other activities within Chile's Antarctic territory. As of 2023, the navy is in the process of acquiring a new Polar 5-class icebreaker, , to support its Antarctic operations, offering year-round operation in medium first-year ice (which may include old ice inclusions). Elements of the Maritime Authority operate throughout the region, promoting the security and interests of Chile, notably with the Maritime Government of Chilean Antarctica in Fildes Bay and at the Captain Arturo Prat Base

Captain Arturo Prat Base (Spanish: Base Naval Antártica "Arturo Prat") is a Chilean Antarctic research station located at Iquique Cove, Greenwich Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica.

Opened February 6, 1947 by the First Chilean An ...

on Greenwich Island

Greenwich Island (variant historical names ''Sartorius Island'', ''Berezina Island'') is an island long and from (average ) wide, lying between Robert Island and Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. The island's surface ...

, formerly a naval base, now a research station. During the 2022–23 Antarctic season, the navy transferred 730 scientists and 3,091 tons of cargo for the logistical support of the Antarctic bases. The operation involved the transport vessel ''Aquiles'', the patrol vessel ''Marinero Fuentealba'', as well as two supporting tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, suc ...

s.

Since 14 January 1995, the navy has assisted the Mendel Polar Station belonging to the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

. Up to four Chilean researchers carry out scientific work at the base, each with sponsorship from a leading Czech researcher who collaborates in the work.

Chilean Antarctic Bases

Following is a list of Chilean Antarctic Bases: (P): Permanent; these bases are open all the year. (S): Seasonal; therse bases are open in the Austral Summer. The largest population center is located on King George Island and consists ofBase Presidente Eduardo Frei Montalva

Base Presidente Eduardo Frei Montalva is the most important Antarctic base of Chile. It is located at Fildes Peninsula, an ice-free area, in front of Fildes Bay, at the west end of King George Island, South Shetland Islands. Situated alongside t ...

which is connected to the communal capital, the village of Villa Las Estrellas

Villa Las Estrellas (; Spanish language, Spanish for ''The Stars Village'' or ''Hamlet of the Stars'') is a permanently inhabited outpost on King George Island (South Shetland Islands), King George Island within the Chilean Antarctica, Antar ...

, which has a town hall, hotel, day-care center, school, scientific equipment, hospital, post office and bank. There is an airport, ''Teniente Rodolfo Marsh Martin Aerodrome'', ICAO

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO ) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that coordinates the principles and techniques of international air navigation, and fosters the planning and development of international sch ...

Code SCRM) This enclave is a center of logistical support for the other eight countries with scientific bases on King George Island.

Nearby, Professor Julio Escudero Base is controlled by the Chilean Antarctic Institute

Chilean may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Chile, a country in South America

* Chilean people

* Chilean Spanish

* Chilean culture

* Chilean cuisine

* Chilean Americans

See also

*List of Chileans

This is a list of Chileans who ar ...

(INACH), under the Ministry of Foreign Relations, and is the main Chilean scientific facility in Antarctica.

Captain Arturo Prat Base

Captain Arturo Prat Base (Spanish: Base Naval Antártica "Arturo Prat") is a Chilean Antarctic research station located at Iquique Cove, Greenwich Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica.

Opened February 6, 1947 by the First Chilean An ...

is a Chilean Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

research base located on Greenwich Island

Greenwich Island (variant historical names ''Sartorius Island'', ''Berezina Island'') is an island long and from (average ) wide, lying between Robert Island and Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. The island's surface ...

. Opened 6 February 1947, it is the oldest Chilean Antarctic base. Until 1 March 2006 it was a base of the Chilean Navy, but was then handed over to the regional government of Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena Region

The Magallanes Region (), officially the Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena Region () or Magallanes and the Chilean Antarctica Region in English, is one of Chile's 16 first order administrative divisions. It is the southernmost, largest, and sec ...

. Until February 2004 it was a permanent base. Afterwards, it served as a summer base for ionospheric and meteorological research, but then reopened in March 2008 for year-round occupancy again.

The only permanent Chilean base on the Antarctic mainland (the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

) is Base General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme

Base General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme, also Base Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme, or shortly Bernardo O'Higgins, named after Bernardo O'Higgins, is a permanently staffed Chilean research station in Antarctica and the capital of ...

. This has been in operation since 18 February 1948. It is located on Puerto Covadonga and it is the official communal capital.

Seasonal bases

Ellsworth Mountains

The Ellsworth Mountains are the highest mountain ranges in Antarctica, forming a long and wide chain of mountains in a north to south configuration on the western margin of the Ronne Ice Shelf in Marie Byrd Land. They are bisected by Minneso ...

, Union Glacier. Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions LLC is a company that has been operating an airport on the Union Glacier since 2008.

* Dr. Guillermo Mann Base is a summer base of the Chilean Antarctic Institute ( INACH), under the Ministry of Foreign Relations, on Livingston Island

Livingston Island (Russian name ''Smolensk'', ) is an Antarctic island in the Southern Ocean, part of the South Shetland Islands, South Shetlands Archipelago, a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands north of the ...

. It is a weather and ecological research station. It is also a site for archaeological research into seal hunting. Another former Chilean refuge also called "Dr. Guillermo Mann" (or Spring-INACH), located in P. Spring (Pen. Palmer), is in ruins.Paul JeffreyCristian Donoso and Claudio Scaletta completes historic journey in Antarctica

/ref> * Luis Risopatrón Base (formerly "Copper Mine Naval Refuge") is a summer station of the Chilean Navy at

Robert Island

Robert Island or Mitchells Island or Polotsk Island or Roberts Island is an island

An island or isle is a piece of land, distinct from a continent, completely surrounded by water. There are continental islands, which were formed by being ...

, used for geodetic, geophysical and biological research.

* Julio Ripamondi Base is a little summer station of the Chilean Antarctic Institute (INACH) located on Ardley Island

Ardley Island is an island long, lying in Maxwell Bay close off the south-west end of King George Island, in the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It was charted as a peninsula in 1935 by Discovery Investigations personnel of the '' Disco ...

, next to Frei Montalva Station and Professor Julio Escudero Base (located nearby on King George Island). The Ripamondi Base has conducted research on geodesy and cartography since 1997, terrestrial biology since 1988 and studies of penguins since 1988. The base is located near a large colony of gentoo penguins.

* González Videla Antarctic Base

González Videla Base is an inactive research station on the Antarctic mainland at Waterboat Point in Paradise Harbor, Paradise Bay. It is named after Chilean President Gabriel González Videla, who in the 1940s became the first chief of state of ...