Antonio Cánovas del Castillo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (8 February 18288 August 1897) was a

Cánovas del Castillo played a key role in bringing an end to the last

Cánovas del Castillo played a key role in bringing an end to the last

In 1897, he was shot dead by Michele Angiolillo, an Italian

In 1897, he was shot dead by Michele Angiolillo, an Italian

File:Coat of Arms of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo.svg

1893: Spanish Conservative Leader Escapes Dynamite Attack

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

politician

A politician is a person who participates in Public policy, policy-making processes, usually holding an elective position in government. Politicians represent the people, make decisions, and influence the formulation of public policy. The roles ...

and historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

known principally for serving six terms as prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

and his overarching role as "architect" of the regime that ensued with the 1874 restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. He was assassinated by Italian anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

Michele Angiolillo.

As leader of the Liberal-Conservative Party

The Liberal-Conservative Party () was the formal name of the Conservative Party of Canada until 1917, and again from 1922 to 1938. Prior to 1970, candidates could run under any label they chose, and in many of Canada's early elections, there wer ...

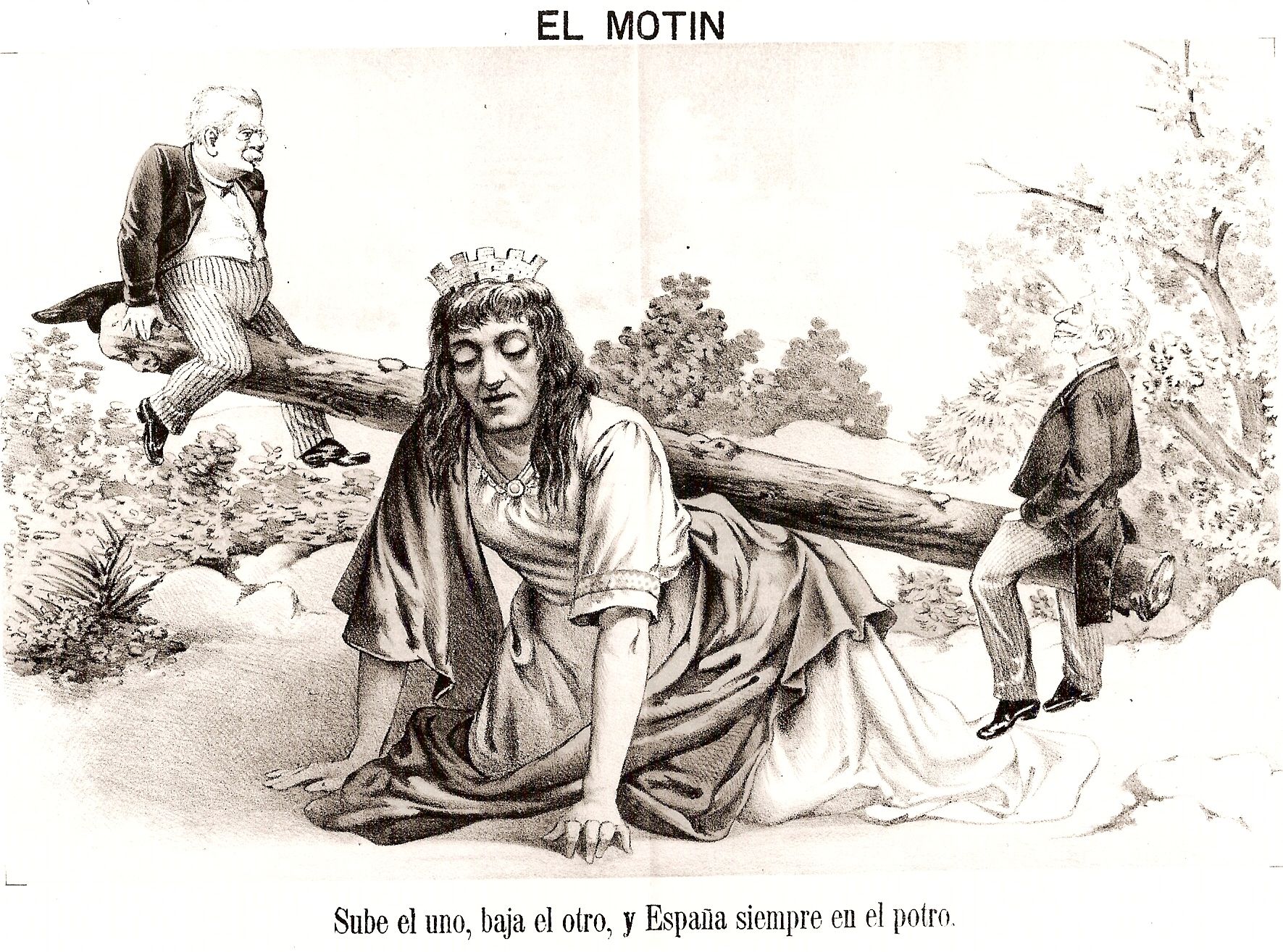

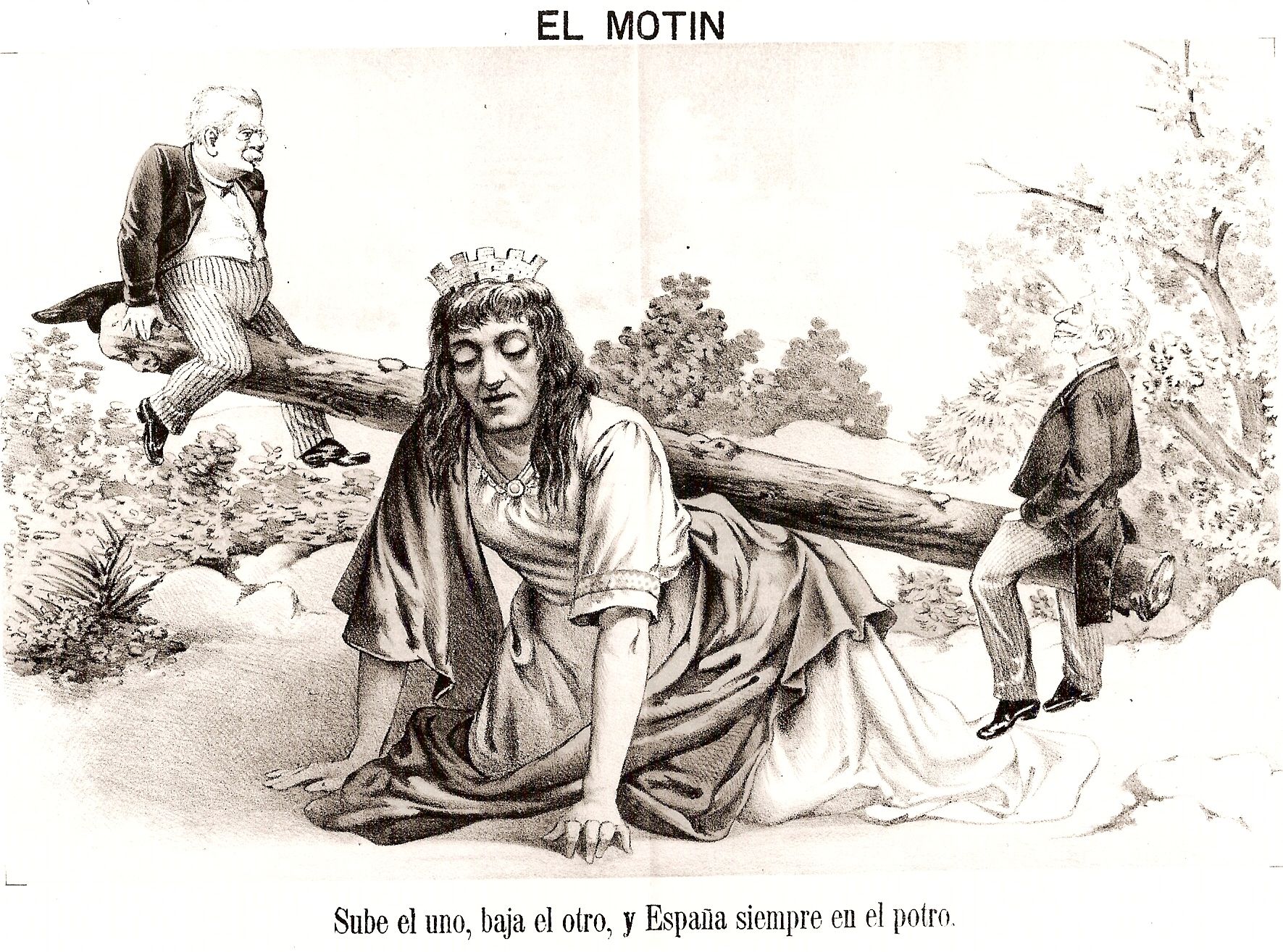

—also known more simply as the Conservative Party—the name of Cánovas became symbolic of the alternate succession in the Restoration regime along with Práxedes Mateo Sagasta

Práxedes Mariano Mateo Sagasta y Escolar (21 July 1825 – 5 January 1903) was a Spanish civil engineer and politician who served as Prime Minister on eight occasions between 1870 and 1902—always in charge of the Liberal Party—as part of t ...

's.

Early career

Born inMálaga

Málaga (; ) is a Municipalities in Spain, municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 591,637 in 2024, it is the second-most populo ...

as the son of Antonio Cánovas García and Juana del Castillo y Estébanez, Cánovas moved to Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

after the death of his father where he lived with his mother's cousin, the writer Serafín Estébanez Calderón. Although he studied law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

at the University of Madrid, he showed an early interest in politics and Spanish history. His active involvement in politics dates to the 1854 revolution, led by General Leopoldo O'Donnell

Leopoldo O'Donnell y Jorris, 1st Duke of Tetuán, GE (12 January 1809 – 5 November 1867), was a Spanish general and Grandee who was Prime Minister of Spain on several occasions.

Early life

He was born at Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Cana ...

, when he drafted the Manifesto of Manzanares, which accompanied the military overthrow of the sitting government, laid out the political goals of the movement, and played a critical role as it attracted the masses' support when the coup seemed to fail. During the final years of Isabel II, he served in a number of posts, including a diplomatic mission to Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, governor of Cádiz

Cádiz ( , , ) is a city in Spain and the capital of the Province of Cádiz in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula off the Atlantic Ocean separated fr ...

, and director general of local administration. That period of his political career culminated in his being twice made a government minister, first taking the interior portfolio in 1864 and then the overseas territories portfolio in 1865 to 1866. After the 1868 Glorious Revolution (Revolución Gloriosa), he retired from the government, but he was a strong supporter of the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy during the First Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), historiographically referred to as the First Spanish Republic (), was the political regime that existed in Spain from 11 February 1873 to 29 December 1874.

The Republic's founding ensued after the abdication of King ...

(1873–1874) and as the leader of the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

minority in the Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of ...

, he declaimed against universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

and freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

. He also drafted the Manifesto of Sandhurst and prevailed upon Alfonso XII to issue it, just as he had done years previously with O'Donnell.

Prime minister

Cánovas returned to active politics with the 1874 overthrow of the Republic by General Martínez Campos and theelevation

The elevation of a geographic location (geography), ''location'' is its height above or below a fixed reference point, most commonly a reference geoid, a mathematical model of the Earth's sea level as an equipotential gravitational equipotenti ...

of Isabell II's son Alfonso XII

Alfonso XII (Alfonso Francisco de Asís Fernando Pío Juan María de la Concepción Gregorio Pelayo de Borbón y Borbón; 28 November 185725 November 1885), also known as ''El Pacificador'' (Spanish: the Peacemaker), was King of Spain from 29 D ...

to the throne. He served as Prime Minister (''Primer presidente del Consejo de Ministros'') for six years starting in 1874 (although he was twice briefly replaced in 1875 and 1879). He was a principal author of the Spanish Constitution

The Spanish Constitution () is the supreme law of the Kingdom of Spain. It was enacted after its approval in 1978 in a constitutional referendum; it represents the culmination of the Spanish transition to democracy.

The current version was a ...

of 1876, which formalised the constitutional monarchy that had resulted from the restoration of Alfonso and limited suffrage to reduce the political influence of the working class and assuage the voting support from the wealthy minority becoming the protected status quo.

Cánovas del Castillo played a key role in bringing an end to the last

Cánovas del Castillo played a key role in bringing an end to the last Carlist

Carlism (; ; ; ) is a Traditionalism (Spain), Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty, one descended from Infante Carlos María Isidro of Spain, Don Carlos, ...

threat to Bourbon authority (1876) by merging a group of dissident Carlist deputies with his own Conservative party. More significantly, his term in office saw the victory achieved by the governmental Spanish troops in the Third Carlist War

The Third Carlist War (), which occurred from 1872 to 1876, was the last Carlist War in Spain. It is sometimes referred to as the "Second Carlist War", as the earlier Second Carlist War, "Second" War (1847–1849) was smaller in scale and relative ...

, the occupation of the Basque territory and the decree establishing an end to the centuries-long Basque specific status (July 1876) that resulted in its annexation to a centralist Spain. Against a backdrop of martial law imposed across the Basque Provinces (and possibly Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

), heated negotiations with Liberal Basque high-ranking officials led to the establishment of the first Basque Economic Agreement (1878).

An artificial two-party system designed to reconcile the competing militarist, Catholic and Carlist power bases led to an alternating prime ministership (known as the '' turno pacifico'') with the progressive Práxedes Mateo Sagasta

Práxedes Mariano Mateo Sagasta y Escolar (21 July 1825 – 5 January 1903) was a Spanish civil engineer and politician who served as Prime Minister on eight occasions between 1870 and 1902—always in charge of the Liberal Party—as part of t ...

after 1881. He also assumed the functions of the head of state during the regency of María Cristina after Alfonso's death in 1885.

Political crisis

By the late 1880s, Cánovas' policies were under threat from two sources. First, his overseas policy was increasingly untenable. A policy of repression against Cuban nationalists was ultimately ineffective and Spain's authority was challenged most seriously by the 1895 rebellion led byJosé Martí

José Julián Martí Pérez (; 28 January 1853 – 19 May 1895) was a Cuban nationalism, nationalist, poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, translator, professor, and publisher, who is considered a Cuban national hero because of his role in ...

. Spain's policy against Cuban independence brought her increasingly into conflict with the United States, an antagonism that culminated in the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

of 1898. Second, the political repression of Spain's working class was growing increasingly troublesome, and pressure for expanded suffrage mounted amid widespread discontent with the ''cacique'' system of electoral manipulation.

Cánovas' policies included mass arrests and a policy of torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

:

During a religious procession in 1896, at Barcelona, a bomb was thrown. Immediately three hundred men and women were arrested. Some were Anarchists, but the majority wereHis attempts to stabilize Spain's parliamentary system achieved a measure of success untiltrade union A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...ists and Socialists. They were thrown into the notorious prison at the fortress ofMontjuïc Montjuïc () is a hill in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Montjuïc or Montjuich, meaning "Jewish Mountain" in medieval Latin and Catalan, is a broad, shallow hill in Barcelona with a rich history. It was the birthplace of the city, and its st ...in Barcelona and tortured. After a number had been killed, or had gone insane, their cases were taken up by the liberal press of Europe, resulting in the release of a few survivors. Reputedly it was Cánovas del Castillo who ordered the torture, including the burning of the victims' flesh, the crushing of their bones, and the cutting out of their tongues. Similar acts of brutality and barbarism had occurred during his regime in Cuba, and Canovas remained deaf to the appeals and protests of civilized conscience.

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in which Spain was not spared the disturbances that ravaged much of the European continent. According to some views, his regime was a welcomed change from Spanish liberalism, considered by some to deny equal participation to political rivals. The restored parliamentary monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

recognized the principle of allowing rival political opponents within the framework of a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

. Yet, it would be decades before universal male suffrage and other typical characteristics of modern democratic systems were implemented; it was still very much an electoral system dominated by parties of established local elites.

Man of letters

At the same time, Cánovas remained an active man of letters. His historical writings earned him a considerable reputation, particularly his ''History of the Decline of Spain'' (Historia de la decadencia de España) for which he was elected at the young age of 32 to theReal Academia de la Historia

The Royal Academy of History (, RAH) is a Spanish institution in Madrid that studies history "ancient and modern, political, civil, ecclesiastical, military, scientific, of letters and arts, that is to say, the different branches of life, of c ...

in 1860. That was followed by elevation to other bodies of letters, including the in 1867, the Academia de Ciencias Morales y Políticas in 1871 and the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando

The Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (RABASF; ), located on the Calle de Alcalá in the centre of Madrid, currently functions as a museum and gallery. A public law corporation, it is integrated together with other Spanish royal aca ...

in 1887. He also served as the head of the Athenaeum in Madrid (1870–74, 1882–84 and 1888–89).

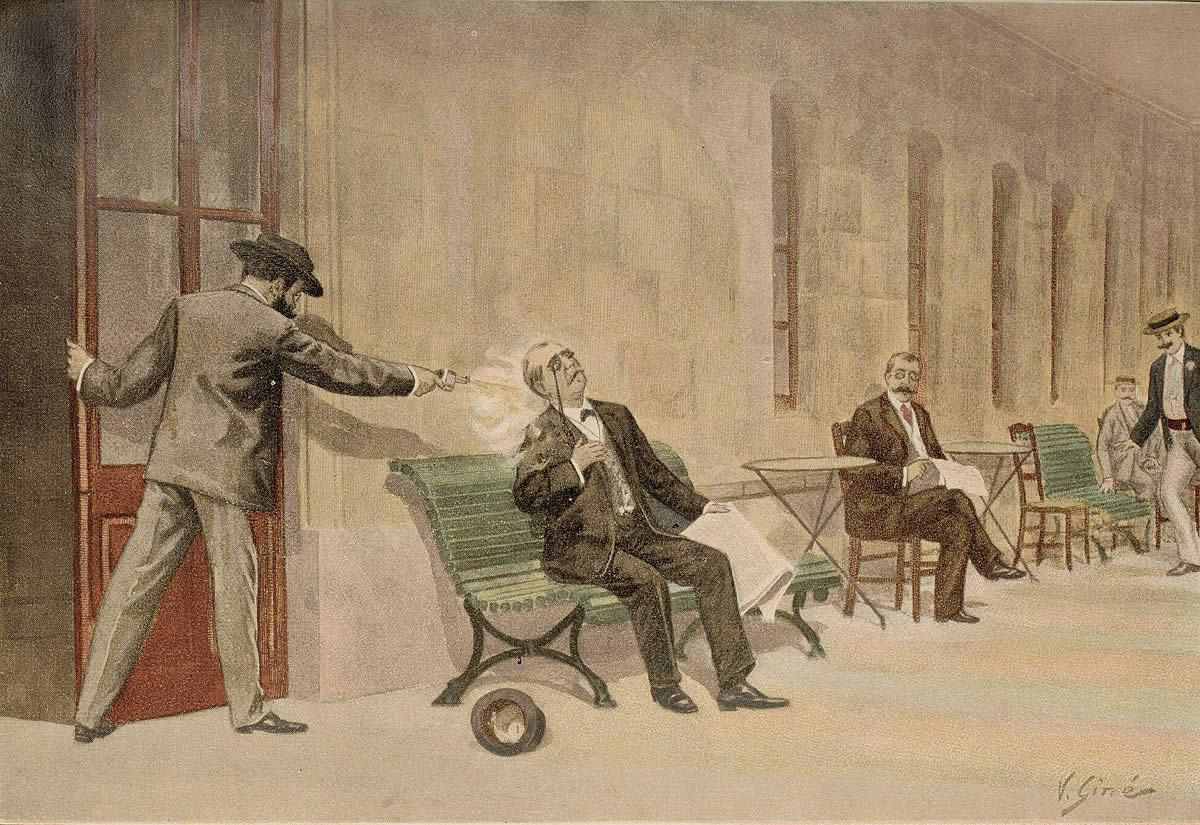

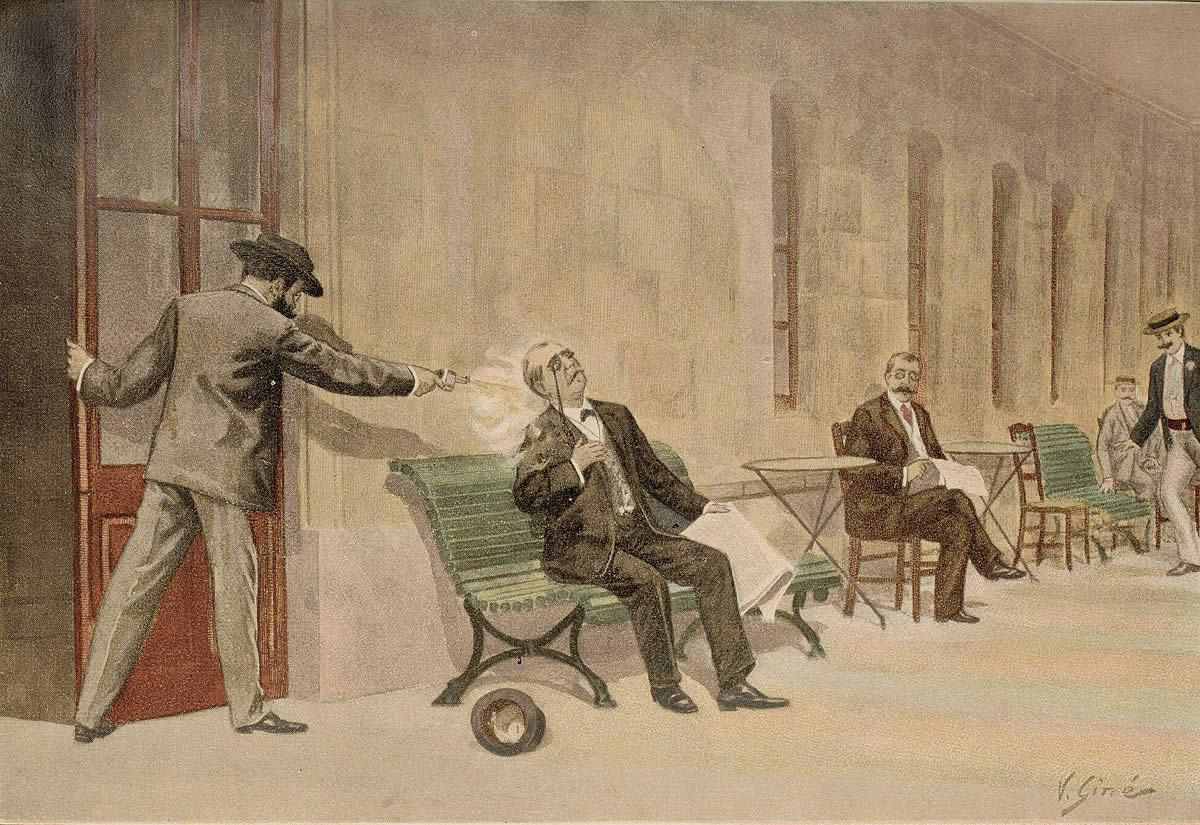

Assassination

In 1897, he was shot dead by Michele Angiolillo, an Italian

In 1897, he was shot dead by Michele Angiolillo, an Italian anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, at the spa ''Santa Águeda'', in Mondragón

Mondragón (in Basque: Arrasate) officially known as Arrasate/Mondragón, is a town and municipality in Gipuzkoa Province, Basque Country, Spain. Its population in 2015 was 21,933.

Toponymy

The current official name of the municipality is Arrasa ...

, Guipúzcoa. Angiolillo invoked vengeance on Canovas on behalf of the execution of Jose Rizal

Jose is the English transliteration of the Hebrew and Aramaic name ''Yose'', which is etymologically linked to ''Yosef'' or Joseph.

Given name Mishnaic and Talmudic periods

* Jose ben Abin

* Jose ben Akabya

*Jose the Galilean

* Jose ben Halaft ...

and other Barcelona anarchists. He thus did not live to see Spain's loss of her final colonies to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

after the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

.

Personal life

He married María de la Concepción Espinosa de los Monteros y Rodrigo de Villamayor on 20 October 1860; he was widowed on 3 September 1863. He married Joaquina de Osma y Zavala on 14 November 1887. No progeny survived him.Ideology and thought

Cánovas was the chief architect of the Restoration regime, that strived for bringing stability to the Spanish society. It has been emphasized that the two figures most influential to his political ideas wereEdmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

(from whom he derived a brand of traditionalism with a historicist rather than religious matrix) and Joaquín Francisco Pacheco

Don Joaquín Francisco Pacheco y Gutiérrez-Calderón (22 February 1808 – 8 October 1865) also known as El Pontífice (The Pontiff), was a Spanish politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of Spain in 1847 and held other important of ...

. Cánovas embraced an essentialist, metaphysical and providentialist conception of the nation. A staunch opponent to universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

, he held the view that "universal suffrage begets socialism in a natural, necessary and inevitable way".

A supporter of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, he declared in November 1896 in a press interview: "Blacks in Cuba are free; they can enter into contracts, work or not work, and I think that slavery was much better than this freedom which they only took advantage of to do nothing and form masses of unemployed. Anyone who knows the blacks will tell you that in Madagascar, the Congo, as in Cuba, they are lazy, savage, prone to misbehavior, and that you have to lead them with authority and firmness to get anything out of them. These savages have no owner other than their own instincts, their primitive appetites".

In reference to his political and intellectual stature, Cánovas was nicknamed as ''el Monstruo'' ("The Monster") by his peers.

Legacy

The policies of repression and political manipulation that Cánovas made a cornerstone of his government helped foster the nationalist movements in bothCatalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

and the Basque provinces and set the stage for labour unrest during the first two decades of the 20th century. The disastrous colonial policy not only led to the loss of Spain's remaining colonial possessions in the Pacific and Caribbean but also seriously weakened the government at home. A failed postwar coup by Camilo de Polavieja Camilo is both a given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

* Camilo (footballer, born 9 March 1986), Fernando Camilo Farias, Brazilian football midfielder

* Camilo (footballer, born 22 March 1986), Camilo de Sousa V ...

set off a long period of political instability, which ultimately led to the collapse of the monarchy and the dissolution of the constitution that Cánovas had authored.

His white marble mausoleum was carved by Agustí Querol Subirats at the Pantheon of Illustrious Men

The Pantheon of Illustrious Men () is a royal site in Madrid, under the administration of the Patrimonio Nacional. It was designed by Spanish architect Fernando Arbós y Tremanti, and is located in Basilica of Nuestra Señora de Atocha in the ...

, in Madrid.

Arms

References

;Citations ;Bibliography * * * *Further reading

*1893: Spanish Conservative Leader Escapes Dynamite Attack

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

Other sources

''The original version of this article draws heavily on the corresponding article in the Spanish-language Wikipedia, which was accessed in the version of 6 September 2007.'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Canovas Del Castillo, Antonio 1828 births 1897 deaths People from Málaga Assassinated prime ministers Assassinated Spanish politicians Deaths by firearm in Spain Knights of St. Gregory the Great Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Leaders of political parties in Spain Members of the Royal Spanish Academy Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium Economy and finance ministers of Spain Presidents of the Congress of Deputies (Spain) Conservative Party (Spain) politicians People murdered in Spain Prime ministers of Spain Spanish untitled nobility Spanish murder victims People murdered in 1897 Spanish political party founders Politicians assassinated in the 1890s 19th-century regents