Anti-Italian Cartoon Published In Life Magazine, 1911 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-Italianism or Italophobia is a negative attitude regarding

Anti-Italianism or Italophobia is a negative attitude regarding

Anti-Italian prejudice was sometimes associated with the

Anti-Italian prejudice was sometimes associated with the

In 1899, in Tallulah, Louisiana, three Italian-American shopkeepers were lynched because they had treated blacks in their shops the same as whites. A vigilante mob hanged five Italian Americans: the three shopkeepers and two bystanders.

In 1920 two Italian immigrants,

In 1899, in Tallulah, Louisiana, three Italian-American shopkeepers were lynched because they had treated blacks in their shops the same as whites. A vigilante mob hanged five Italian Americans: the three shopkeepers and two bystanders.

In 1920 two Italian immigrants,

''The Internment of Aliens in Twentieth Century Britain''

, Routledge, 1st ed. (1 May 1993), pp. 176–178. During the Second World War, much Allied propaganda was directed against Italian military performance, usually expressing a stereotype of the "incompetent Italian soldier". Historians have documented that the Italian Army suffered major defeats due to its being poorly prepared for major combat as a result of Mussolini's refusal to heed warnings by Italian Army commanders. Objective World War II accounts show that, despite having to rely in many cases on outdated weapons, Italian troops frequently fought with great valor and distinction, especially well trained and equipped units such as the

''Anti-Italianism: Essays on a Prejudice''

Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. . * Gardaphe, Fred. ''From Wiseguys to Wise Men: The Gangster and Italian American Masculinities'' (Routledge, 2006). * * Larke-Walsh, George S. ''Screening the Mafia: Masculinity, Ethnicity and Mobsters from The Godfather to The Sopranos'' (Macfarland, 2010

online

* * Smith, Tom. ''The Crescent City Lynchings: The Murder of Chief Hennessy, the New Orleans "Mafia" Trials, and the Parish Prison Mob'', The Lyons Press, 2007

online

{{Italy topics

Anti-Italianism or Italophobia is a negative attitude regarding

Anti-Italianism or Italophobia is a negative attitude regarding Italians

Italians (, ) are a European peoples, European ethnic group native to the Italian geographical region. Italians share a common Italian culture, culture, History of Italy, history, Cultural heritage, ancestry and Italian language, language. ...

or people with Italian ancestry, often expressed through the use of prejudice, discrimination or stereotypes

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalization, generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can ...

. Often stemming from xenophobia

Xenophobia (from (), 'strange, foreign, or alien', and (), 'fear') is the fear or dislike of anything that is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression that is based on the perception that a conflict exists between an in-gr ...

, anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics and opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and its adherents. Scholars have identified four categories of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cul ...

sentiment and job security issues, it manifested itself in varying degrees in a number of countries to which Italians had immigrated in large numbers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and after WWII. Its opposite is Italophilia

Italophilia is the admiration, general appreciation or love of Italy, its people, culture, and its significant contributions to Western civilization. Italophilia includes Romanophilia, the appreciation of the Italian capital of Rome and its an ...

, which is admiration of Italy, its people, and its culture.

In the United States

Anti-Italianism arose among some Americans as an effect of the large-scale immigration of Italians to the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The majority of Italian immigrants to the United States arrived in waves in the early 20th century, many of them from agrarian backgrounds. Nearly all theItalian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

immigrants were Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, as opposed to the nation's Protestant majority. Because the immigrants often lacked formal education and competed with earlier immigrants for lower-paying jobs and housing, significant hostility developed toward them.

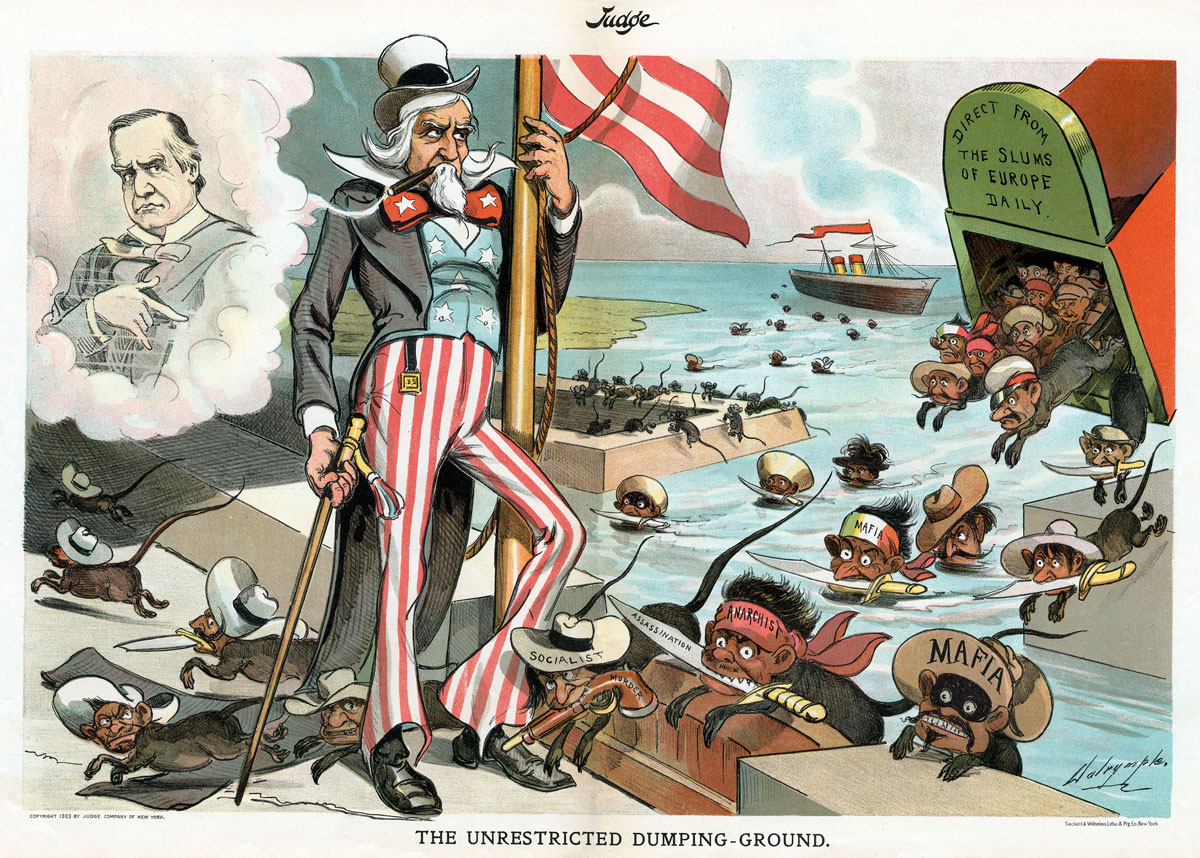

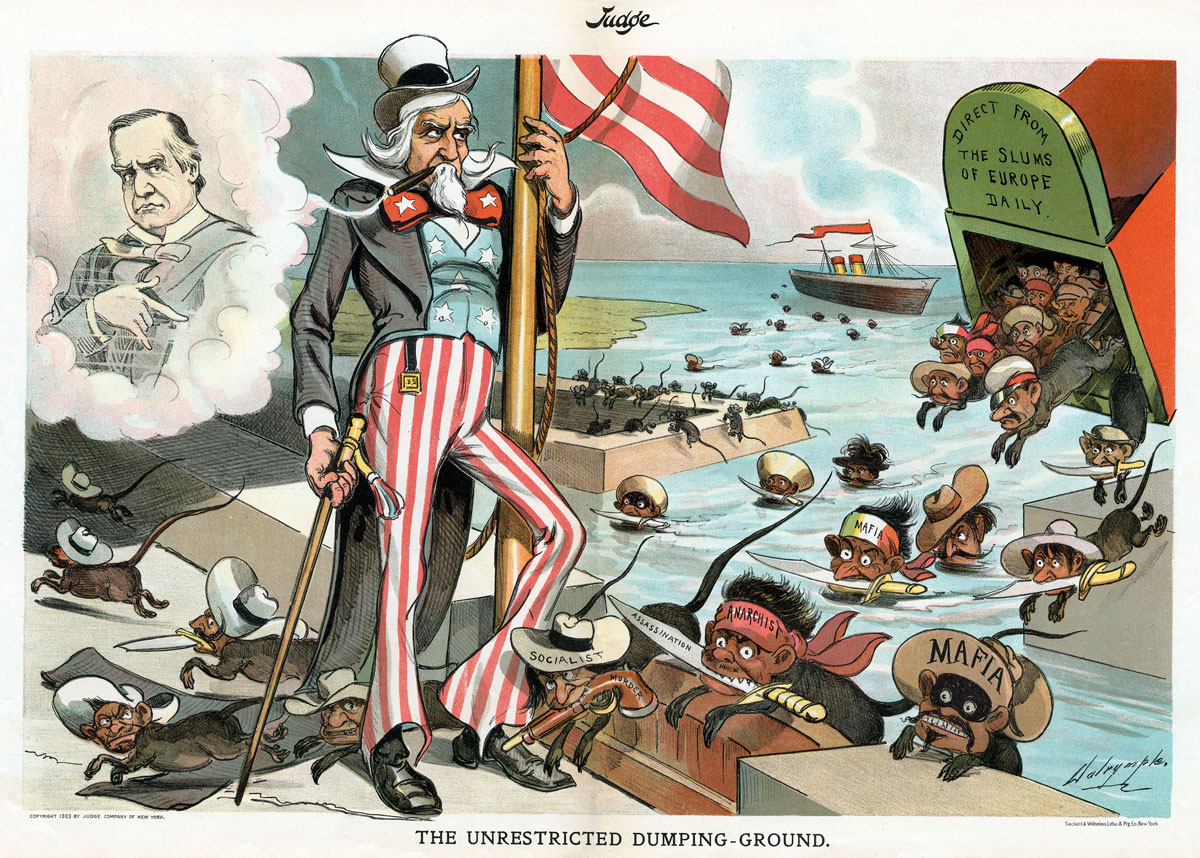

In reaction to the large-scale immigration from Southern Europe and Eastern Europe, the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

passed legislation (Emergency Quota Act

__NOTOC__

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act (ch. 8, of May 19, 1921), was formulated mainly in response to the lar ...

of 1921 and Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

) severely restricting immigration from those regions, but putting comparatively fewer restrictions on immigration from Northern European countries.

Anti-Italian prejudice was sometimes associated with the

Anti-Italian prejudice was sometimes associated with the anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics and opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and its adherents. Scholars have identified four categories of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cul ...

tradition that existed in the United States, which was inherited as a result of Protestant/Catholic European competition and wars, which had been fought between Protestants and Catholics over the preceding three centuries. When the United States was founded, it inherited the anti-Catholic, anti-papal animosity of its original Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

settler

A settler or a colonist is a person who establishes or joins a permanent presence that is separate to existing communities. The entity that a settler establishes is a Human settlement, settlement. A settler is called a pioneer if they are among ...

s. Anti-Catholic sentiments in the U.S. reached a peak in the 19th century, when the Protestant population became alarmed by the large number of Catholics who were immigrating to the United States from Ireland and Germany. The resulting anti-Catholic nativist movement, achieved prominence in the 1840s and 1850s. It had largely faded away before the Italians arrived in large numbers after 1880. The Italian immigrants, unlike some of the other Catholic immigrant groups, generally did not bring with them priests and other religious figures who could help ease their transition into American life. To remedy this situation, Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the A ...

dispatched a contingent of priests, nuns and brothers of the Missionaries of Saint Charles Borromeo and other orders (among which was Sister Francesca Cabrini), who helped establish hundreds of parishes to serve the needs of the Italian communities, such as Our Lady of Pompeii in New York City.

Some of the early 20th-century immigrants from Italy brought with them a political disposition toward anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

. This was a reaction to the economic and political conditions which they had experienced in Italy. Such men as Arturo Giovannitti, Carlo Tresca, and Joe Ettor were at the forefront of organising Italians and other immigrant laborers in demanding better working conditions and shorter working hours in the mining, textile, garment, construction and other industries. These efforts often resulted in strikes, which sometimes erupted into violence between the strikers and strike-breakers. Italians were often strikebreakers. The anarchy movement in the United States at that time was responsible for bombings in major cities, and attacks on officials and law enforcement. As a result of the association of some with the labour and anarchy movements, Italian Americans were branded as " labor agitators" and radicals by many of the business owners and the upper class of the time, which resulted in further anti-Italian sentiment.

The vast majority of Italian immigrants worked hard and lived honest lives, as documented by police statistics of the early 20th century in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

and New York City. Italian immigrants had an arrest rate that was no greater than those of other major immigrant groups. As late as 1963, James W. Vander Zander noted that the rate of criminal convictions among Italian immigrants was less than that among American-born whites.

A criminal element that was active in some of the Italian immigrant communities in the large eastern cities used extortion, intimidation and threats in order to extract protection money

A protection racket is a type of racket and a scheme of organized crime perpetrated by a potentially hazardous organized crime group that generally guarantees protection outside the sanction of the law to another entity or individual from viol ...

from the wealthier immigrants and shop owners (known as the Black Hand racket), and it was also involved in other illegal activities as well. When the Fascists came to power in Italy, they made the destruction of the Mafia in Sicily a high priority. Hundreds fled to the United States in the 1920s and 1930s in order to avoid prosecution.

When the United States enacted prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

in 1920, the restrictions proved to be an economic windfall for those in the Italian-American community who were already involved in illegal activities, as well as those who had fled from Sicily. They smuggled liquor into the country, wholesaled and sold it through a network of outlets and speakeasies. While members of other ethnic groups were also deeply involved in these illegal bootlegging activities, and the associated violence between groups, Italian Americans were among the most notorious. Because of this, Italians became associated with the prototypical gangster in the minds of many, which had a long-lasting effect on the Italian-American image.

The experiences of Italian immigrants in North American countries were notably different from those in South American countries, where many of them immigrated in large numbers. Italians were key in developing countries such as: Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

and Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

. They quickly joined the middle

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek ...

and upper classes in those countries. In the U.S., Italian Americans initially encountered an established Protestant-majority Northern European culture. For a time, they were viewed mainly as construction and industrial workers, chefs, plumbers, or other blue collar

A blue-collar worker is a person who performs manual labor or skilled trades. Blue-collar work may involve skilled or unskilled labor. The type of work may involve manufacturing, retail, warehousing, mining, carpentry, electrical work, custodia ...

workers. Like the Irish before them, many entered police and fire departments of major cities.

Violence against Italians

After theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, during the labour shortage that occurred as the South converted to free labour, planters in southern states recruited Italians to come to the United States and work, mainly as agricultural workers and labourers. Many soon found themselves the victims of prejudice and economic exploitation, and they were sometimes victims of violence. Anti-Italian stereotypes abounded during this period as a means of justifying the maltreatment of immigrants. The plight of the Italian immigrant agricultural workers in Mississippi was so serious that the Italian embassy became involved in investigating their mistreatment in cases that were studied for peonage

Peon ( English , from the Spanish '' peón'' ) usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control ove ...

. Later waves of Italian immigrants inherited these same virulent forms of discrimination and stereotyping which, by then, had become ingrained in the American consciousness. In the 1890s, more than 20 Italians were lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of in ...

in the United States.

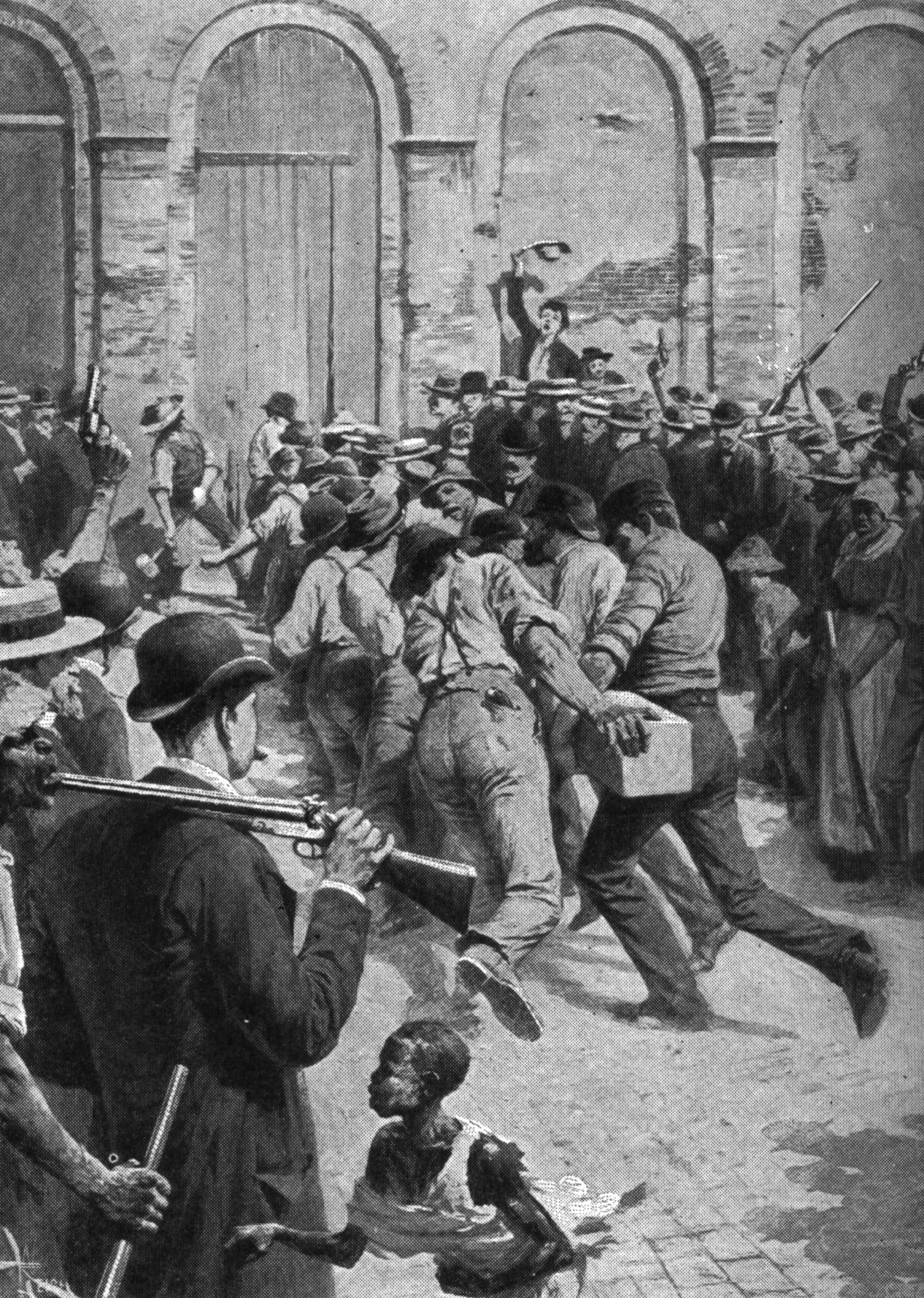

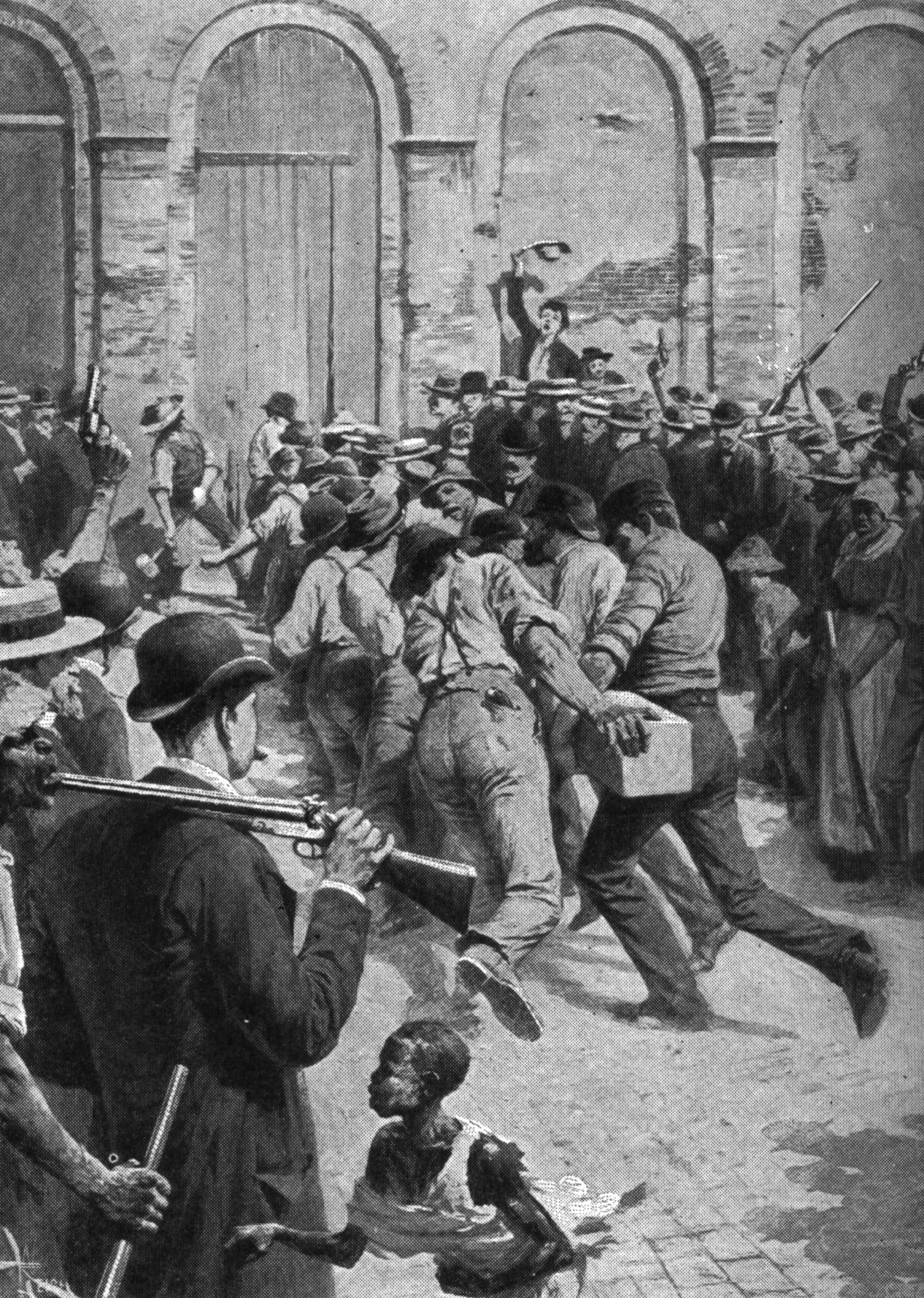

The largest mass-lynching in American history

The history of the present-day United States began in roughly 15,000 BC with the arrival of Peopling of the Americas, the first people in the Americas. In the late 15th century, European colonization of the Americas, European colonization beg ...

was the mass-lynching of eleven Italians in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, Louisiana, in 1891. The city had been the destination for numerous Italian immigrants. Nineteen Italians who were thought to have assassinated police chief David Hennessy were arrested and held in the Parish Prison. Nine were tried, resulting in six acquittals and three mistrials. The next day, a mob stormed the prison and killed eleven men, none of whom had been convicted, and some of whom had not been tried. Afterward, the police arrested hundreds of Italian immigrants, on the false pretext that they were all criminals. Teddy Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York politics, including serving as ...

, not yet president, famously said the lynching was indeed "a rather good thing". John M. Parker helped organize the lynch mob, and in 1911 was elected as governor of Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

. He described Italians as "just a little worse than the Negro, being if anything filthier in their habits, lawless, and treacherous".

In 1899, in Tallulah, Louisiana, three Italian-American shopkeepers were lynched because they had treated blacks in their shops the same as whites. A vigilante mob hanged five Italian Americans: the three shopkeepers and two bystanders.

In 1920 two Italian immigrants,

In 1899, in Tallulah, Louisiana, three Italian-American shopkeepers were lynched because they had treated blacks in their shops the same as whites. A vigilante mob hanged five Italian Americans: the three shopkeepers and two bystanders.

In 1920 two Italian immigrants, Sacco and Vanzetti

Nicola Sacco (; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrants and anarchists who were controversially convicted of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and Frederick Parm ...

, were tried for robbery and murder in Braintree, Massachusetts

Braintree () is a municipality in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is officially known as a town, but Braintree is a city with a mayor-council form of government, and it is considered a city under Massachusetts law. The populat ...

. Many historians agree that Sacco and Vanzetti were subjected to a mishandled trial, and the judge, jury, and prosecution were biased against them because of their anarchist political views and Italian immigrant status. Judge Webster Thayer called Sacco and Vanzetti "Bolsheviki!" and said he would "get them good and proper". In 1924 Thayer confronted a Massachusetts lawyer: "Did you see what I did with those anarchistic bastards the other day?", the judge said. Despite worldwide protests, Sacco and Vanzetti were eventually executed. Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis ( ; born November 3, 1933) is an American politician and lawyer who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1975 to 1979 and from 1983 to 1991. He is the longest-serving governor in Massachusetts history and only the s ...

declared August 23, 1977, the 50th anniversary of their execution, as Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti Memorial Day. His proclamation, issued in English and Italian, stated that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that "any disgrace should be forever removed from their names". He did not pardon them, because that would imply they were guilty.

In the 1930s, Italians together with Jews were targeted by Sufi Abdul Hamid, an anti-Semite

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

and admirer of Mufti of Palestine Amin al-Husseini

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini (; 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine. was the scion of the family of Jerusalemite Arab nobles, who trace their origins to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Hussein ...

.

Anti-Italianism was part of the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic ideology of the revived Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

(KKK) after 1915; the white supremacist and nativist group targeted Italians and other Southern Europeans, seeking to preserve the supposed dominance of White Anglo-Saxon Protestants

In the United States, White Anglo-Saxon Protestants or Wealthy Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASP) is a sociological term which is often used to describe white Protestant Americans of English, or more broadly British, descent who are generally par ...

. During the early 20th century, the KKK became active in northern and midwestern cities, where social change had been rapid due to immigration and industrialization. It was not limited to the South. It reached a peak of membership and influence in 1925. A hotbed of anti-Italian KKK activity developed in South Jersey

South Jersey, also known as Southern New Jersey, comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is located between Pennsylvania and the lower Delaware River to its west, the Atlantic Ocean to its east, Delaware to its south, ...

in the mid-1920s. In 1933, there was a mass protest against Italian immigrants in Vineland, New Jersey

Vineland is a City (New Jersey), city and the most populous municipality in Cumberland County, New Jersey, Cumberland County, within the U.S. state of New Jersey. Bridgeton, New Jersey, Bridgeton and Vineland are the two principal cities of the ...

, where Italians made up 20% of the city population. The KKK eventually lost all of its power in Vineland and left the city.

Anti-Italian-American stereotyping

Since the early 20th century, Italian-Americans have been portrayed with stereotypes. Hostility was often directed toward the large numbers of southern Italians and Sicilians who began arriving in the U.S. after 1880. Italian-Americans in contemporary American society have actively objected to pervasive negativestereotyping

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for example ...

in the mass media. Stereotyping of Italian-Americans being associated with the Mafia

"Mafia", as an informal or general term, is often used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the Sicilian Mafia, original Mafia in Sicily, to the Italian-American Mafia, or to other Organized crime in Italy, organiz ...

has been a consistent feature of movies such as ''The Godfather

''The Godfather'' is a 1972 American Epic film, epic crime film directed by Francis Ford Coppola, who co-wrote the screenplay with Mario Puzo, based on Puzo's best-selling The Godfather (novel), 1969 novel. The film stars an ensemble cast inc ...

'' series, '' GoodFellas'', and ''Casino

A casino is a facility for gambling. Casinos are often built near or combined with hotels, resorts, restaurants, retail shops, cruise ships, and other tourist attractions. Some casinos also host live entertainment, such as stand-up comedy, conce ...

'', and television series such as ''The Sopranos

''The Sopranos'' is an American Crime film#Crime drama, crime drama television series created by David Chase. The series follows Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini), a New Jersey American Mafia, Mafia boss who suffers from panic attacks. He reluct ...

'', which itself explored the concept by featuring non-Mafia Italian-Americans expressing concern at the Mafia's effect on their community's public image.

Such stereotypes of Italian-Americans are reinforced by the frequent replay of these movies and series on cable and network TV. Video and board games, and TV and radio commercials with Mafia

"Mafia", as an informal or general term, is often used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the Sicilian Mafia, original Mafia in Sicily, to the Italian-American Mafia, or to other Organized crime in Italy, organiz ...

themes also reinforce this stereotype. The entertainment media has stereotyped the Italian-American community as tolerant of violent, sociopathic gangsters. Other notable stereotypes portray Italian-Americans as overly aggressive and prone to violence. MTV

MTV (an initialism of Music Television) is an American cable television television channel, channel and the flagship property of the MTV Entertainment Group sub-division of the Paramount Media Networks division of Paramount Global. Launched on ...

's series ''Jersey Shore

The Jersey Shore, commonly called the Shore by locals, is the coast, coastal region of the U.S. state of New Jersey. The term encompasses about of shore, oceanfront bordering the Atlantic Ocean, from Perth Amboy, New Jersey, Perth Amboy in the n ...

'' was considered offensive by the Italian-American group UNICO

is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Osamu Tezuka. It was serialized in Sanrio's manga magazine ' from November 1976 to March 1979 and collected in two volumes. The series follows the titular unicorn as he uses his magi ...

.

A comprehensive study of Italian-American culture on film, conducted from 1996 to 2001, by the Italic Institute of America, revealed the extent of stereotyping in media. More than two-thirds of the 2,000 films assessed in the study portray Italian-Americans in a negative light. Nearly 300 films featuring Italian-Americans as mobsters have been produced since ''The Godfather'' (1972), an average of nine per year.

According to the Italic Institute of America, "The mass media has consistently ignored five centuries of Italian American history and has elevated what was never more than a minute subculture to the dominant Italian American culture."

According to 2015 FBI statistics, Italian-American organized crime members and associates number approximately 3,000. Given an Italian-American population estimated to be approximately 18 million, the study concludes that only one in 6,000 is active in organized crime.

Italian-American organizations

National organizations which have been active in combatting media stereotyping and defamation of Italian Americans are: Order Sons of Italy in America, Unico National, Columbus Citizens Foundation, National Italian American Foundation and the Italic Institute of America. Four Internet-based organizations are: Annotico Report, the Italian-American Discussion Network, ItalianAware and the Italian American One Voice Coalition.Columbus Day

Decisions by states and municipalities across the United States to change Columbus Day to Indigenous People's Day have been claimed by some commentators to be an attack on Italian Americans and their history, including anti-Italian discrimination. In California, the Italian Cultural Society of Sacramento proclaimed that, "Indigenous Peoples Day is viewed by Italian Americans and other Americans as anti-Columbus Day." Other Italian-American groups, such as Italian Americans for Indigenous People's Day, have welcomed the change and asserted that it is not anti-Italian.In the United Kingdom

An early manifestation of anti-Italianism in Britain was in 1820, at the time whenKing George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until his death in 1830. At the time of his accession to the throne, h ...

sought to dissolve his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick

Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (Caroline Amelia Elizabeth; 17 May 1768 – 7 August 1821) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Queen of Hanover from 29 January 1820 until her ...

. A sensational proceeding, the Pains and Penalties Bill 1820

The Pains and Penalties Bill 1820 was a bill introduced to the British Parliament in 1820, at the request of King George IV, which aimed to dissolve his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick, and deprive her of the title of queen.

George and Caroline ...

, was held at the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

in an effort to prove Caroline's adultery; since she had been living in Italy, many prosecution witnesses were from among her servants. The prosecution's reliance on Italian witnesses of low repute led to anti-Italian sentiment in Britain. The witnesses had to be protected from angry mobs, and were depicted in popular prints and pamphlets as venal, corrupt and criminal. Street-sellers sold prints alleging that the Italians had accepted bribes to commit perjury.

Anti-Italianism broke out again, in a more sustained way, a century later. After Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's alliance with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

in the late 1930s, there was a growing hostility towards Italy in the United Kingdom. The British media ridiculed the Italian capacity to fight in a war, pointing to the poor state of the Italian military during its imperialistic phase. A comic strip, which began running in 1938 in the British comic ''The Beano

''The Beano'' (formerly ''The Beano Comic'') is a British anthology comic magazine created by Scottish publishing company DC Thomson. Its first issue was published on 30 July 1938, and it published its 4000th issue in August 2019. Popular and ...

'', was entitled "Musso the Wop". The strip featured Mussolini as an arrogant buffoon.

'' Wigs on the Green'' was a novel by Nancy Mitford

Nancy Freeman-Mitford (28 November 1904 – 30 June 1973) was an English novelist, biographer, and journalist. The eldest of the Mitford family#Mitford sisters, Mitford sisters, she was regarded as one of the "bright young things" on the ...

first published in 1935. It was a merciless satire of British fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

and the Italians living in the United Kingdom who supported it. The book is notable for lampooning the political enthusiasms of Mitford's sister Diana Mosley, and her links with some Italians in Great Britain who promoted the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

of Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980), was a British aristocrat and politician who rose to fame during the 1920s and 1930s when he, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, turned to fascism. ...

. Furthermore, the announcement of Benito Mussolini's decision to side with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's Germany in the spring of 1940 caused an immediate response. By order of Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, all enemy aliens were to be interned, although there were few active Italian fascists

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social h ...

. This anti-Italian feeling led to a night of nationwide riots against the Italian communities in June 1940. The Italians were now seen as a national security threat linked to the feared British Fascism

file:Flash and circle.svg, The flash and circle symbol was first used by the British Union of Fascists (BUF).

British fascism is the form of fascism which is promoted by some political parties and movements in the United Kingdom. It is based on ...

movement, and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

gave instructions to "collar the lot!". Thousands of Italian men between the ages of 17 and 60 were arrested after his speech.

World War II

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

acknowledged the ancient history of the Roman civilization

The history of Rome includes the history of the Rome, city of Rome as well as the Ancient Rome, civilisation of ancient Rome. Roman history has been influential on the modern world, especially in the history of the Catholic Church, and Roman la ...

. He regarded the Italians as more artistic but less industrious than the Germanic population. In the interbellum period, Germans believed the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

had "stabbed them in the back" by joining the "Big Four" in the ( Treaty of London, 1915). Hitler never made any speech denouncing Italy for this, instead worked on forging an alliance with a fellow Fascist regime.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the United States and the United Kingdom designated Italian citizens living in their countries as alien, irrespective of how long they had lived there. Hundreds of Italian citizens, suspected by ethnicity of potential loyalty to Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

, were put in internment camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

. Thousands more Italian citizens in the U.S., suspected of loyalty to Italy, were placed under surveillance. Joe DiMaggio

Joseph Paul DiMaggio (; born Giuseppe Paolo DiMaggio, ; November 25, 1914 – March 8, 1999), nicknamed "Joltin' Joe", "the Yankee Clipper" and "Joe D.", was an American professional baseball center fielder who played his entire 13-year career ...

's father, who lived in San Francisco, had his boat and house confiscated. Unlike Japanese Americans, Italian Americans and Italian Canadians never received reparations from their respective governments, but President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

made a public declaration admitting the U.S. government's misjudgement in the internment.Di Stasi, Lawrence (2004). ''Una Storia Segreta: The Secret History of Italian American Evacuation and Internment during World War II'', Heyday Books. .

Because of the Italian conquest of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

and Italy's alliance with Nazi Germany, in the United Kingdom popular feeling developed against all the Italians in the country. Many Italian nationals were deported as enemy aliens, with some being killed by German submarines torpedoing the transportation ships.David Cesarani, Tony Kushner''The Internment of Aliens in Twentieth Century Britain''

, Routledge, 1st ed. (1 May 1993), pp. 176–178. During the Second World War, much Allied propaganda was directed against Italian military performance, usually expressing a stereotype of the "incompetent Italian soldier". Historians have documented that the Italian Army suffered major defeats due to its being poorly prepared for major combat as a result of Mussolini's refusal to heed warnings by Italian Army commanders. Objective World War II accounts show that, despite having to rely in many cases on outdated weapons, Italian troops frequently fought with great valor and distinction, especially well trained and equipped units such as the

Bersaglieri

The Bersaglieri, singular Bersagliere, (, "sharpshooter") are a troop of marksmen in the Italian Army's infantry corps. They were originally created by General Alessandro Ferrero La Marmora on 18 June 1836 to serve in the Royal Sardinian Ar ...

, Paratroopers

A paratrooper or military parachutist is a soldier trained to conduct military operations by parachuting directly into an area of operations, usually as part of a large airborne forces unit. Traditionally paratroopers fight only as light inf ...

and Alpini

The Alpini are the Italian Army's specialist mountain infantry. Part of the army's infantry corps, the speciality distinguished itself in combat during World War I and World War II. Currently the active Alpini units are organized in two operati ...

.

"''The German soldier has impressed the world, the Italian Bersagliere has impressed the German soldier''", praise towards Italian soldiers attributed to Erwin Rommel on a plaque at the Italian War Memorial at El Alamein

Bias includes both implicit assumptions, evident in Knox's title ''The Sources of Italy's Defeat in 1940: Bluff or Institutionalized Incompetence?'', and the selective use of sources. Also see Sullivan's ''The Italian Armed Forces''. Sims, in ''The Fighter Pilot'', ignored the Italians, while D'Este in ''World War II in the Mediterranean'' shaped his reader's image of Italians by citing a German comment that Italy's surrender was "the basest treachery". Further, he discussed Allied and German commanders but ignored Messe, who commanded the Italian First Army, which held off both the U.S. Second Corps and the British Eighth Army in Tunisia.

In his article, ''Anglo-American Bias and the Italo-Greek War'' (1994), Sadkovich writes:

Knox and other Anglo-American historians have not only selectively used Italian sources, but they have also gleaned negative observations and racist slurs and comments from British, American, and German sources and then presented them as objective depictions of Italian political and military leaders, a game that if played in reverse would yield some interesting results regarding German, American, and British competence.Sadkovich also states that

such a fixation on Germany and such denigrations of Italians not only distort analysis, but they also reinforce the misunderstandings and myths that have grown up around the Greek theater and allow historians to lament and debate the impact of the Italo-Greek conflict on the British and German war efforts, yet dismiss as unimportant its impact on the Italian war effort. Because Anglo-American authors start from the assumption that Italy's war effort was secondary in importance to that of Germany, they implicitly, if unconsciously, deny even the possibility of a 'parallel war' long before Italian setbacks in late 1940, because they define Italian policy as subordinate to German from the very beginning of the war. Alan Levine even goes most authors one better by dismissing the whole Mediterranean theater as irrelevant, but only after duly scolding Mussolini for 'his imbecilic attack on Greece'.

After World War II

Former Italian communities once thrived in Italy's African colonies ofEritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

, Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

and Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, and in the areas at the borders of the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. In the aftermath of the end of imperial colonies and other political changes, many ethnic Italians were violently expelled from these areas, or left under threat of violence.

Libya

InLibya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, during its years as an Italian colony, some 150,000 Italians settled there, constituting about 18% of the total population. During the rise of independence movements, hostility increased against colonists. All of Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

's remaining ethnic Italians were expelled from Libya in 1970, a year after Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (20 October 2011) was a Libyan military officer, revolutionary, politician and political theorist who ruled Libya from 1969 until Killing of Muammar Gaddafi, his assassination by Libyan Anti-Gaddafi ...

seized power: Day of Revenge

The Day of Revenge ( ''Yūm al-Intiqāmi'') was a Libyan holiday celebrating the expulsion of Italians from Libyan soil in 1970. Some sources also claim that the 1948–67 expulsion of Libyan Jews was also celebrated.

It was canceled in 2004 a ...

on 7 October 1970. Later, it was renamed the Day of Friendship because of improvement in Italy–Libya relations

Italy–Libya relations are the bilateral relations between the State of Libya and the Italian Republic. Italy has an embassy in Libya's capital, Tripoli, and a general consulate in Benghazi. Libya has an embassy in Italy's capital, Rome, and tw ...

.

Yugoslavia

At the end ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, former Italian territories in Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

became part of Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

by the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947

The Treaty of Paris between Italy and the Allied Powers was signed on 10 February 1947, formally ending hostilities between both parties. It came into general effect on 15 September 1947.

Territorial changes

* Transfer of the Adriatic isl ...

. Economic insecurity, ethnic hatred and the international political context that eventually led to the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

resulted in up to 350,000 people, nearly all ethnic Italians

Italians (, ) are a European peoples, European ethnic group native to the Italian geographical region. Italians share a common Italian culture, culture, History of Italy, history, Cultural heritage, ancestry and Italian language, language. ...

, choosing to or being forced to leave the region during Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslavia, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 unti ...

's rule. Scholars such as Rudolph Rummel

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (October 21, 1932 – March 2, 2014) was an American political scientist, a statistician and professor at Indiana University, Yale University, and University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He spent his career studying data on collect ...

note that the number of Dalmatian Italians

Dalmatian Italians (; ) are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro.

Historically, Italian language-speaking Dalmatians accounted for 12.5% of population in 1865, 5.8% in 18 ...

has dropped from 45,000 in 1848, when they comprised nearly 10% of the total Dalmatian population under Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, to 300 in modern times, related to democide

Democide refers to "the intentional killing of an unarmed or disarmed person by government agents acting in their authoritative capacity and pursuant to government policy or high command." The term, first coined by Holocaust historian and stat ...

and ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

, although much criticism has been raised regarding these numbers.

Ethiopia and Somalia

Other forms of anti-Italianism showed up in Ethiopia and Somalia in the late 1940s, as happened with the Somali nationalist rebellion against the Italian colonial administration that culminated in a violent confrontation in January 1948 ( Eccidio di Mogadiscio). 54 Italians, mostly women and children, died in the ensuing political riots inMogadishu

Mogadishu, locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Ocean for millennia and has ...

and several coastal towns.

In France

The massacre of the Italians at Aigues-Mortes took place on 16 and 17 August 1893, inAigues-Mortes

Aigues-Mortes (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Gard Departments of France, department in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitania region of southern France. The medieval Ramparts of Aigues-Mortes, city walls surrounding th ...

, France, which resulted in the deaths of immigrant Italian workers of the ''Compagnie des Salins du Midi'', at the hands of French villagers and labourers. Estimates range from the official number of eight deaths up to 150, according to the Italian press of the time. Those killed were victims of lynchings, beatings with clubs, drowning and rifle shot. There were also many non-fatal injuries.Gérard Noiriel, ''Le massacre des Italiens: Aigues-Mortes, 17 août 1893'' (Paris: Fayard, 2010). .

The massacre was not the first attack by French workers on poor Italian immigrant labourers that were prepared to work at cut-rate wages.Hugh Seton-Watson, ''Italy from liberalism to fascism'' (1967), pp. 161–62. When the news reached Italy anti-French riots erupted in the country. The case was also one of the greatest legal scandals of the time, since no convictions were ever made.

See also

*Racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

* '' Compagnie Francaise de Navigation a Vapeur v. Louisiana Board of Health'', a 1902 U.S. Supreme Court case that upheld state laws that prevented Italian immigrants from disembarking into quarantine zones

* Internment of Italian Americans in U.S. World War II

References

Further reading

* * * Connell, William J. and Fred Gardaphé, eds.''Anti-Italianism: Essays on a Prejudice''

Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. . * Gardaphe, Fred. ''From Wiseguys to Wise Men: The Gangster and Italian American Masculinities'' (Routledge, 2006). * * Larke-Walsh, George S. ''Screening the Mafia: Masculinity, Ethnicity and Mobsters from The Godfather to The Sopranos'' (Macfarland, 2010

online

* * Smith, Tom. ''The Crescent City Lynchings: The Murder of Chief Hennessy, the New Orleans "Mafia" Trials, and the Parish Prison Mob'', The Lyons Press, 2007

online

{{Italy topics

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

Italian-American culture