Anthony Eden, 1st Earl Of Avon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as

Eden was educated at two independent schools. He attended

Eden was educated at two independent schools. He attended

During the 1939 in the United Kingdom, last months of peace in 1939, Eden joined the Army Reserve (United Kingdom), Territorial Army with the rank of major, in the London Rangers motorised battalion of the King's Royal Rifle Corps and was at annual camp with them in Beaulieu, Hampshire, when he heard news of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

Two days after the Invasion of Poland, outbreak of war, on 3 September 1939, Eden, unlike most Territorials, did not mobilise for active service. Instead, he returned to Chamberlain's government as Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs and he visited Mandatory Palestine in February 1940 to inspect the Second Australian Imperial Force. However, he was not in the War Cabinet. As a result, he was not a candidate for prime minister when Chamberlain resigned on 10 May 1940 after the Narvik Debate and Churchill became prime minister. Churchill appointed Eden Secretary of State for War.

At the end of 1940, Eden returned to the Foreign Office and became a member of the executive committee of the Political Warfare Executive in 1941. Although he was one of Churchill's closest confidants, his role in wartime was restricted because Churchill himself conducted the most important negotiations, those with Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin, but Eden served loyally as Churchill's lieutenant. In December 1941, he travelled by ship to the Soviet Union where he met the Soviet leader Stalin and surveyed the battlefields upon which the Soviets had successfully defended Moscow from the German Army attack in Operation Barbarossa.

Nevertheless, he was in charge of handling most of the relations between Britain and the Free French leader, Charles de Gaulle, during the last years of the war. Eden was often both critical of the emphasis Churchill put on the Special Relationship, special relationship with the United States and disappointed by the American treatment of its British allies.

In 1942, Eden was given the additional role of Leader of the House of Commons. He was considered for various other major jobs during and after the war, including Commander-in-Chief Middle East in 1942 (which would have been a very unusual appointment as Eden was a civilian; General Harold Alexander would be appointed), Viceroy of India in 1943 (General Archibald Wavell was appointed to this job) or Secretary-General of the United Nations, Secretary-General of the newly formed United Nations Organisation in 1945. In 1943, with the revelation of the Katyn massacre, Eden refused to help the Polish Government in Exile. Eden supported the idea of post-war Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, expulsion of ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia.

In early 1943, Eden blocked a request from the Bulgarian authorities to aid with deporting part of the History of the Jews in Bulgaria, Jewish population from newly acquired Bulgarian territories to the British territory of Mandatory Palestine. After his refusal, some of the people were transported to Treblinka extermination camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. That same spring, Eden visited Washington, D.C., for high-level talks with President Roosevelt, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and Harry Hopkins, where they discussed anticipated postwar issues, including the occupation and future political structure of Germany.

In 1944, Eden went to Moscow to negotiate with the Soviet Union at the Tolstoy Conference. Eden also opposed the Morgenthau Plan to deindustrialise Germany. After the Stalag Luft III murders, he vowed in the House of Commons to bring the perpetrators of the crime to "exemplary justice", which led to a successful manhunt after the war by the Royal Air Force's Special Investigation Branch. During the Yalta Conference (February 1945) he pressed the Soviet Union and the United States to allow France a French occupation zone in Germany, zone of occupation in Allied-occupied Germany, post-war Germany.

Eden's eldest son, Pilot officer Simon Gascoigne Eden, went missing in action and was later declared dead; he was serving as a navigator with the Royal Air Force in Burma in June 1945. There was a close bond between Eden and Simon, and Simon's death was a great personal shock to his father. Mrs Eden reportedly reacted to the loss of her son differently, which led to a breakdown in the marriage. De Gaulle wrote him a personal letter of condolence in French.

In 1945, he was mentioned by Halvdan Koht among seven candidates who were qualified for the Nobel Peace Prize. However, he did not explicitly nominate any of them. The person who was actually nominated was Cordell Hull.

During the 1939 in the United Kingdom, last months of peace in 1939, Eden joined the Army Reserve (United Kingdom), Territorial Army with the rank of major, in the London Rangers motorised battalion of the King's Royal Rifle Corps and was at annual camp with them in Beaulieu, Hampshire, when he heard news of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

Two days after the Invasion of Poland, outbreak of war, on 3 September 1939, Eden, unlike most Territorials, did not mobilise for active service. Instead, he returned to Chamberlain's government as Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs and he visited Mandatory Palestine in February 1940 to inspect the Second Australian Imperial Force. However, he was not in the War Cabinet. As a result, he was not a candidate for prime minister when Chamberlain resigned on 10 May 1940 after the Narvik Debate and Churchill became prime minister. Churchill appointed Eden Secretary of State for War.

At the end of 1940, Eden returned to the Foreign Office and became a member of the executive committee of the Political Warfare Executive in 1941. Although he was one of Churchill's closest confidants, his role in wartime was restricted because Churchill himself conducted the most important negotiations, those with Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin, but Eden served loyally as Churchill's lieutenant. In December 1941, he travelled by ship to the Soviet Union where he met the Soviet leader Stalin and surveyed the battlefields upon which the Soviets had successfully defended Moscow from the German Army attack in Operation Barbarossa.

Nevertheless, he was in charge of handling most of the relations between Britain and the Free French leader, Charles de Gaulle, during the last years of the war. Eden was often both critical of the emphasis Churchill put on the Special Relationship, special relationship with the United States and disappointed by the American treatment of its British allies.

In 1942, Eden was given the additional role of Leader of the House of Commons. He was considered for various other major jobs during and after the war, including Commander-in-Chief Middle East in 1942 (which would have been a very unusual appointment as Eden was a civilian; General Harold Alexander would be appointed), Viceroy of India in 1943 (General Archibald Wavell was appointed to this job) or Secretary-General of the United Nations, Secretary-General of the newly formed United Nations Organisation in 1945. In 1943, with the revelation of the Katyn massacre, Eden refused to help the Polish Government in Exile. Eden supported the idea of post-war Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, expulsion of ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia.

In early 1943, Eden blocked a request from the Bulgarian authorities to aid with deporting part of the History of the Jews in Bulgaria, Jewish population from newly acquired Bulgarian territories to the British territory of Mandatory Palestine. After his refusal, some of the people were transported to Treblinka extermination camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. That same spring, Eden visited Washington, D.C., for high-level talks with President Roosevelt, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and Harry Hopkins, where they discussed anticipated postwar issues, including the occupation and future political structure of Germany.

In 1944, Eden went to Moscow to negotiate with the Soviet Union at the Tolstoy Conference. Eden also opposed the Morgenthau Plan to deindustrialise Germany. After the Stalag Luft III murders, he vowed in the House of Commons to bring the perpetrators of the crime to "exemplary justice", which led to a successful manhunt after the war by the Royal Air Force's Special Investigation Branch. During the Yalta Conference (February 1945) he pressed the Soviet Union and the United States to allow France a French occupation zone in Germany, zone of occupation in Allied-occupied Germany, post-war Germany.

Eden's eldest son, Pilot officer Simon Gascoigne Eden, went missing in action and was later declared dead; he was serving as a navigator with the Royal Air Force in Burma in June 1945. There was a close bond between Eden and Simon, and Simon's death was a great personal shock to his father. Mrs Eden reportedly reacted to the loss of her son differently, which led to a breakdown in the marriage. De Gaulle wrote him a personal letter of condolence in French.

In 1945, he was mentioned by Halvdan Koht among seven candidates who were qualified for the Nobel Peace Prize. However, he did not explicitly nominate any of them. The person who was actually nominated was Cordell Hull.

Eden had grave misgivings about American foreign policy under Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and President Dwight D. Eisenhower. As early as March 1953, Eisenhower was concerned at the escalating costs of defence and the increase of state power that it would bring.Charmley 1995, pp. 274–275. Eden was irked by Dulles's policy of "brinkmanship", the display of muscle, in relations with the Second World, communist world. In particular, both had heated exchanges with one another regarding the proposed American aerial strike operation (Operation Vulture, ''Vulture'') to try to save the beleaguered French Union garrison at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in early 1954. The operation was cancelled, in part, because of Eden's refusal to commit to it for fear of Chinese intervention and ultimately a third world war. Dulles then walked out early in the Geneva Conference (1954), Geneva Conference talks and was critical of the American decision not to sign it. Nevertheless, the success of the conference ranked as the outstanding achievement of Eden's third term in the Foreign Office. During the summer and autumn of 1954, the Anglo-Egyptian agreement to withdraw all British forces from Egypt was also negotiated and ratified.

There were concerns that if the European Defence Community was not ratified as it wanted, the United States might withdraw into defending only the Western Hemisphere, but recent documentary evidence confirms that the US intended to withdraw troops from Europe anyway even if the EDC was ratified. After the French National Assembly rejected the EDC in August 1954, Eden offered a viable alternative. Between 11 and 17 September, with the help of the Foreign Office's Frank Roberts (diplomat), Frank Roberts, he visited every major West European capital to negotiate the rearmament and NATO membership of West Germany. The intervention was a diplomatic triumph that marked a major step in the consolidation of the Western bloc.

In October 1954, Eden was appointed to the Order of the Garter and became ''Sir Anthony Eden''.

Eden had grave misgivings about American foreign policy under Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and President Dwight D. Eisenhower. As early as March 1953, Eisenhower was concerned at the escalating costs of defence and the increase of state power that it would bring.Charmley 1995, pp. 274–275. Eden was irked by Dulles's policy of "brinkmanship", the display of muscle, in relations with the Second World, communist world. In particular, both had heated exchanges with one another regarding the proposed American aerial strike operation (Operation Vulture, ''Vulture'') to try to save the beleaguered French Union garrison at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in early 1954. The operation was cancelled, in part, because of Eden's refusal to commit to it for fear of Chinese intervention and ultimately a third world war. Dulles then walked out early in the Geneva Conference (1954), Geneva Conference talks and was critical of the American decision not to sign it. Nevertheless, the success of the conference ranked as the outstanding achievement of Eden's third term in the Foreign Office. During the summer and autumn of 1954, the Anglo-Egyptian agreement to withdraw all British forces from Egypt was also negotiated and ratified.

There were concerns that if the European Defence Community was not ratified as it wanted, the United States might withdraw into defending only the Western Hemisphere, but recent documentary evidence confirms that the US intended to withdraw troops from Europe anyway even if the EDC was ratified. After the French National Assembly rejected the EDC in August 1954, Eden offered a viable alternative. Between 11 and 17 September, with the help of the Foreign Office's Frank Roberts (diplomat), Frank Roberts, he visited every major West European capital to negotiate the rearmament and NATO membership of West Germany. The intervention was a diplomatic triumph that marked a major step in the consolidation of the Western bloc.

In October 1954, Eden was appointed to the Order of the Garter and became ''Sir Anthony Eden''.

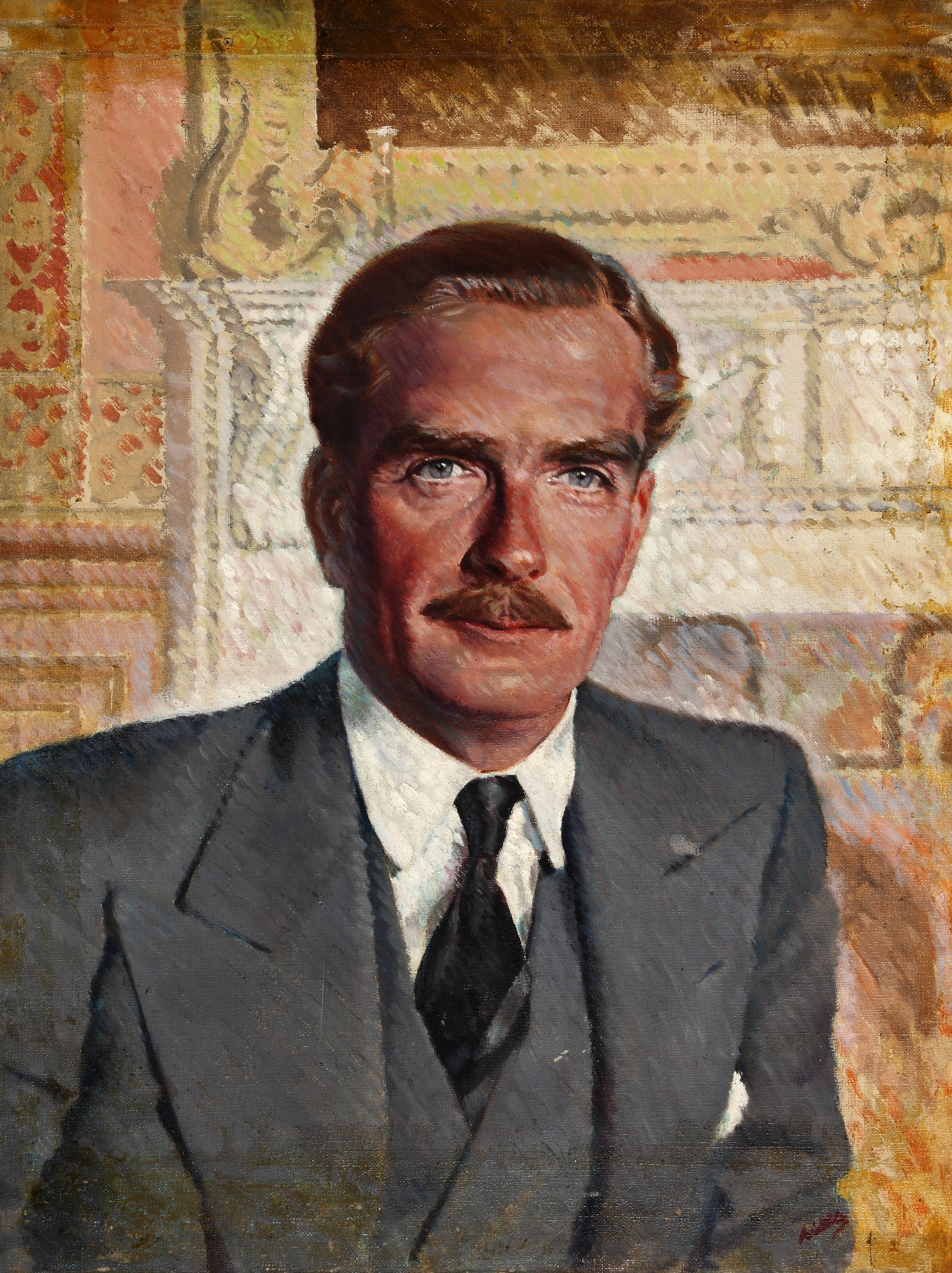

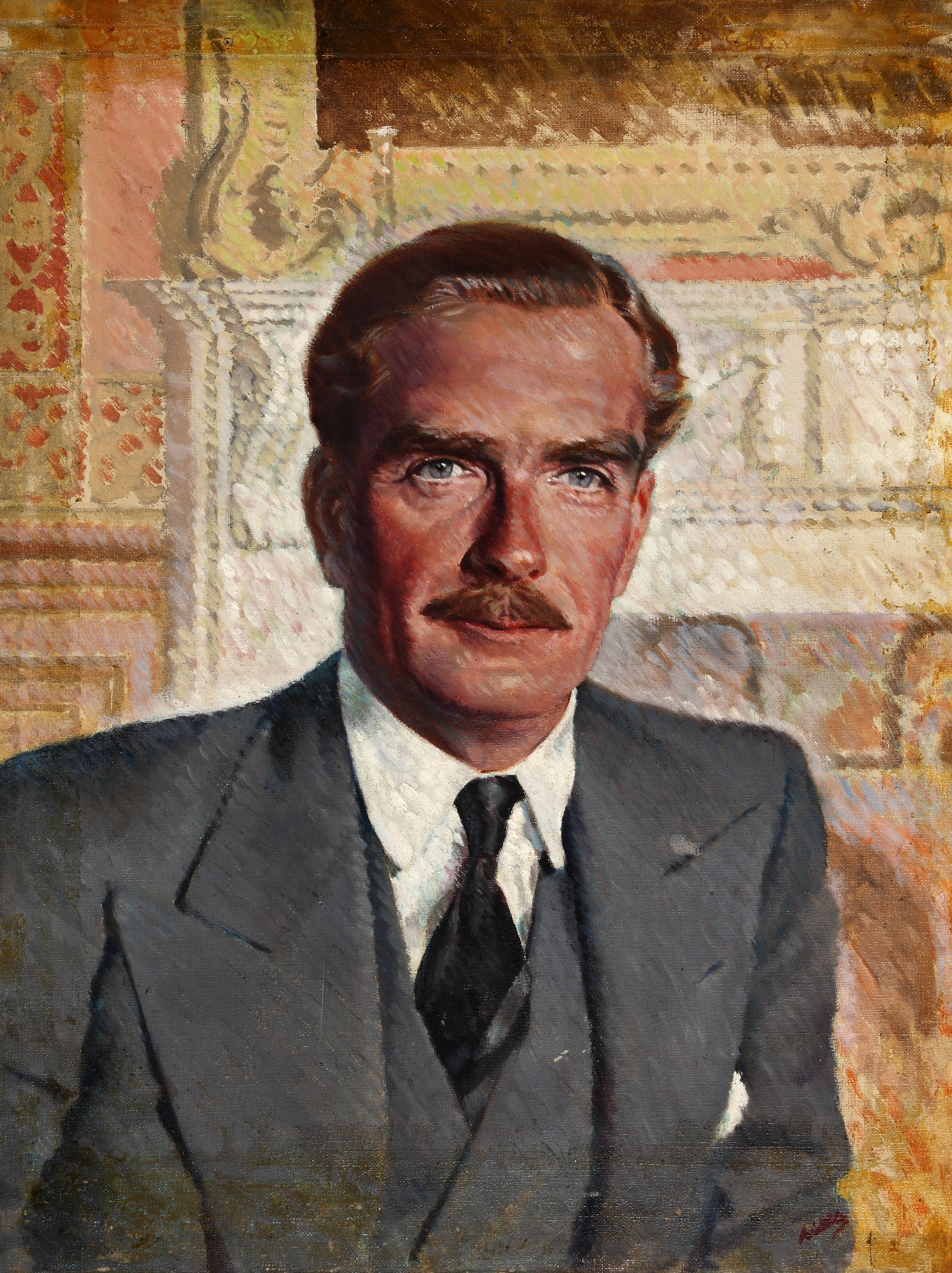

Eden was well-mannered, well-groomed, and good-looking. This image gave him huge popular support throughout his political life, but some contemporaries felt he was merely a superficial person lacking any deeper convictions. That view was enforced by his very pragmatism, pragmatic approach to politics. Sir Oswald Mosley, for example, said he never understood why Eden was so strongly pushed by the Tory party, as he felt that Eden's abilities were very much inferior to those of Harold Macmillan and Oliver Stanley. In 1947, Dick Crossman called Eden "that peculiarly British type, the idealist without conviction".

US Secretary of State Dean Acheson regarded Eden as quite an old-fashioned amateur in politics, typical of the British establishment. In contrast, Soviet Leader Nikita Khrushchev commented that until his Suez adventure Eden had been "in the top world class".

Eden was heavily influenced by Stanley Baldwin when he first entered Parliament. After earlier combative beginnings, he cultivated a low-key speaking style that relied heavily on rational argument and consensus-building, rather than rhetoric and party point-scoring, which was often highly effective in the House of Commons. However, he was not always an effective public speaker, and his parliamentary performances sometimes disappointed many of his followers, such as after his resignation from Neville Chamberlain's government. Winston Churchill once even commented on one of Eden's speeches that the latter had used every cliché except "1 John, God is love". That was deliberate; Eden often struck out original phrases from speech drafts and replaced them with clichés.

Eden's inability to express himself clearly is often attributed to shyness and lack of self-confidence. Eden is known to have been much more direct in meeting with his secretaries and advisers than in cabinet meetings and public speeches and sometimes tended to become enraged and behave "like a child", only to regain his temper within a few minutes. Many who worked for him remarked that he was "two men": one charming, erudite, and hard-working, and the other petty and prone to temper tantrums, during which he would insult his subordinates.

As prime minister, Eden was notorious for telephoning ministers and newspaper editors from 6 a.m. onward. Rothwell wrote that even before Suez, the telephone had become "a drug": "During the Suez Crisis Eden's telephone mania exceeded all bounds".

Eden was notoriously "unclubbable" and offended Churchill by declining to join The Other Club. He also declined honorary membership in the Athenaeum Club, London, Athenaeum. However, he maintained friendly relations with Opposition MPs; for example, George Thomas, 1st Viscount Tonypandy, George Thomas received a kind two-page letter from Eden on learning that his stepfather had died. Eden was a Trustee of the National Gallery (in succession to MacDonald) between 1935 and 1949. He also had a deep knowledge of Persian poetry and of Shakespeare and would bond with anybody who could display similar knowledge.

Rothwell wrote that, although Eden was capable of acting with ruthlessness, for instance over Repatriation of Cossacks after World War II, the repatriation of the Cossacks in 1945, his main concern was to avoid being seen as "an appeaser", such as over the Soviet reluctance to accept a democratic Poland in October 1944. Like many people, Eden convinced himself that his past actions were more consistent than they had in fact been.

A. J. P. Taylor wrote in the 1970s: "Eden … destroyed (his reputation as a peacemaker) and led Great Britain to one of the greatest humiliations in her history … (he) seemed to take on a new personality. He acted impatiently and on impulse. Previously flexible he now relied on dogma, denouncing Nasser as a second Hitler. Though he claimed to be upholding international law, he in fact disregarded the United Nations Organisation which he had helped to create...The outcome was pathetic rather than tragic".

Biographer D. R. Thorpe says Eden's four goals were to secure the canal; to make sure it remained open and that oil shipments would continue; to depose Nasser; and to prevent the USSR from gaining influence. "The immediate consequence of the crisis was that the Suez Canal was blocked, oil supplies were interrupted, Nasser's position as the leader of Arab nationalism was strengthened, and the way was left open for Russian intrusion into the Middle East.

Michael Foot pushed for a special inquiry along the lines of the Parliamentary Inquiry into the Gallipoli Campaign, Attack on the Dardanelles in the First World War, although Harold Wilson (Labour Prime Minister 1964–70 and 1974–76) regarded the matter as a can of worms best left unopened. This talk ceased after the defeat of the Arab armies by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967, after which Eden received a lot of mail telling him that he had been right, and his reputation, not least in Israel and the United States, soared. In 1986 Eden's official biographer Robert Rhodes James re-evaluated sympathetically Eden's stance over Suez and in 1990, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, James asked: "Who can now claim that Eden was wrong?" Such arguments turn mostly on whether, as a matter of policy, the Suez operation was fundamentally flawed or whether, as such "revisionists" thought, the lack of American support conveyed the impression that the West was divided and weak. Anthony Nutting, who resigned as Minister of State for Indo-Pacific (United Kingdom), Minister of State for Foreign Affairs over Suez, expressed the former view in 1967, the year of the Six-Day War, Arab–Israeli Six-Day War, when he wrote that "we had sown the wind of bitterness and we were to reap the whirlwind of revenge and rebellion". Conversely, Jonathan Pearson argues in ''Sir Anthony Eden and the Suez Crisis: Reluctant Gamble'' (2002) that Eden was more reluctant and less bellicose than most historians have judged. D. R. Thorpe, another of Eden's biographers, writes that Suez was "a truly tragic end to his premiership, and one that came to assume a disproportionate importance in any assessment of his careers"; he suggests that had the Suez venture succeeded, "there would almost certainly have been no Middle East war in 1967, and probably no Yom Kippur War in 1973 also".

Guy Millard, one of Eden's private secretaries, who thirty years later, in a radio interview, spoke publicly for the first time on the crisis, made an insider's judgement about Eden: "It was his mistake of course and a tragic and disastrous mistake for him. I think he overestimated the importance of Nasser, Egypt, the Canal, even of the Middle East." While British actions in 1956 have usually been described as "imperialistic", the main motivation was economic. Eden was a liberal supporter of nationalist ambitions, including Sudanese independence, and his 1954 Suez Canal Base Agreement, which withdrew British troops from Suez in return for certain guarantees, was negotiated with the Conservative Party against Churchill's wishes.

Rothwell believes that Eden should have cancelled the Suez invasion plans in mid-October, when Anglo-French negotiations at the United Nations were making some headway, and that in 1956 the Arab countries threw away a chance to make peace with Israel on her existing borders.

Recent biographies put more emphasis on Eden's achievements in foreign policy and perceive him to have held deep convictions regarding world peace and security, as well as a strong social conscience. Rhodes James applied to Eden Churchill's famous verdict on Lord Curzon (in ''Great Contemporaries''): "The morning had been golden; the noontime was bronze; and the evening lead. But all was solid, and each was polished until it shone after its fashion".

Both Eden Court, Leamington Spa, built in 1960, and Sir Anthony Eden Way, Warwick, built in the 2000s, are named in his honour.

Eden was well-mannered, well-groomed, and good-looking. This image gave him huge popular support throughout his political life, but some contemporaries felt he was merely a superficial person lacking any deeper convictions. That view was enforced by his very pragmatism, pragmatic approach to politics. Sir Oswald Mosley, for example, said he never understood why Eden was so strongly pushed by the Tory party, as he felt that Eden's abilities were very much inferior to those of Harold Macmillan and Oliver Stanley. In 1947, Dick Crossman called Eden "that peculiarly British type, the idealist without conviction".

US Secretary of State Dean Acheson regarded Eden as quite an old-fashioned amateur in politics, typical of the British establishment. In contrast, Soviet Leader Nikita Khrushchev commented that until his Suez adventure Eden had been "in the top world class".

Eden was heavily influenced by Stanley Baldwin when he first entered Parliament. After earlier combative beginnings, he cultivated a low-key speaking style that relied heavily on rational argument and consensus-building, rather than rhetoric and party point-scoring, which was often highly effective in the House of Commons. However, he was not always an effective public speaker, and his parliamentary performances sometimes disappointed many of his followers, such as after his resignation from Neville Chamberlain's government. Winston Churchill once even commented on one of Eden's speeches that the latter had used every cliché except "1 John, God is love". That was deliberate; Eden often struck out original phrases from speech drafts and replaced them with clichés.

Eden's inability to express himself clearly is often attributed to shyness and lack of self-confidence. Eden is known to have been much more direct in meeting with his secretaries and advisers than in cabinet meetings and public speeches and sometimes tended to become enraged and behave "like a child", only to regain his temper within a few minutes. Many who worked for him remarked that he was "two men": one charming, erudite, and hard-working, and the other petty and prone to temper tantrums, during which he would insult his subordinates.

As prime minister, Eden was notorious for telephoning ministers and newspaper editors from 6 a.m. onward. Rothwell wrote that even before Suez, the telephone had become "a drug": "During the Suez Crisis Eden's telephone mania exceeded all bounds".

Eden was notoriously "unclubbable" and offended Churchill by declining to join The Other Club. He also declined honorary membership in the Athenaeum Club, London, Athenaeum. However, he maintained friendly relations with Opposition MPs; for example, George Thomas, 1st Viscount Tonypandy, George Thomas received a kind two-page letter from Eden on learning that his stepfather had died. Eden was a Trustee of the National Gallery (in succession to MacDonald) between 1935 and 1949. He also had a deep knowledge of Persian poetry and of Shakespeare and would bond with anybody who could display similar knowledge.

Rothwell wrote that, although Eden was capable of acting with ruthlessness, for instance over Repatriation of Cossacks after World War II, the repatriation of the Cossacks in 1945, his main concern was to avoid being seen as "an appeaser", such as over the Soviet reluctance to accept a democratic Poland in October 1944. Like many people, Eden convinced himself that his past actions were more consistent than they had in fact been.

A. J. P. Taylor wrote in the 1970s: "Eden … destroyed (his reputation as a peacemaker) and led Great Britain to one of the greatest humiliations in her history … (he) seemed to take on a new personality. He acted impatiently and on impulse. Previously flexible he now relied on dogma, denouncing Nasser as a second Hitler. Though he claimed to be upholding international law, he in fact disregarded the United Nations Organisation which he had helped to create...The outcome was pathetic rather than tragic".

Biographer D. R. Thorpe says Eden's four goals were to secure the canal; to make sure it remained open and that oil shipments would continue; to depose Nasser; and to prevent the USSR from gaining influence. "The immediate consequence of the crisis was that the Suez Canal was blocked, oil supplies were interrupted, Nasser's position as the leader of Arab nationalism was strengthened, and the way was left open for Russian intrusion into the Middle East.

Michael Foot pushed for a special inquiry along the lines of the Parliamentary Inquiry into the Gallipoli Campaign, Attack on the Dardanelles in the First World War, although Harold Wilson (Labour Prime Minister 1964–70 and 1974–76) regarded the matter as a can of worms best left unopened. This talk ceased after the defeat of the Arab armies by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967, after which Eden received a lot of mail telling him that he had been right, and his reputation, not least in Israel and the United States, soared. In 1986 Eden's official biographer Robert Rhodes James re-evaluated sympathetically Eden's stance over Suez and in 1990, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, James asked: "Who can now claim that Eden was wrong?" Such arguments turn mostly on whether, as a matter of policy, the Suez operation was fundamentally flawed or whether, as such "revisionists" thought, the lack of American support conveyed the impression that the West was divided and weak. Anthony Nutting, who resigned as Minister of State for Indo-Pacific (United Kingdom), Minister of State for Foreign Affairs over Suez, expressed the former view in 1967, the year of the Six-Day War, Arab–Israeli Six-Day War, when he wrote that "we had sown the wind of bitterness and we were to reap the whirlwind of revenge and rebellion". Conversely, Jonathan Pearson argues in ''Sir Anthony Eden and the Suez Crisis: Reluctant Gamble'' (2002) that Eden was more reluctant and less bellicose than most historians have judged. D. R. Thorpe, another of Eden's biographers, writes that Suez was "a truly tragic end to his premiership, and one that came to assume a disproportionate importance in any assessment of his careers"; he suggests that had the Suez venture succeeded, "there would almost certainly have been no Middle East war in 1967, and probably no Yom Kippur War in 1973 also".

Guy Millard, one of Eden's private secretaries, who thirty years later, in a radio interview, spoke publicly for the first time on the crisis, made an insider's judgement about Eden: "It was his mistake of course and a tragic and disastrous mistake for him. I think he overestimated the importance of Nasser, Egypt, the Canal, even of the Middle East." While British actions in 1956 have usually been described as "imperialistic", the main motivation was economic. Eden was a liberal supporter of nationalist ambitions, including Sudanese independence, and his 1954 Suez Canal Base Agreement, which withdrew British troops from Suez in return for certain guarantees, was negotiated with the Conservative Party against Churchill's wishes.

Rothwell believes that Eden should have cancelled the Suez invasion plans in mid-October, when Anglo-French negotiations at the United Nations were making some headway, and that in 1956 the Arab countries threw away a chance to make peace with Israel on her existing borders.

Recent biographies put more emphasis on Eden's achievements in foreign policy and perceive him to have held deep convictions regarding world peace and security, as well as a strong social conscience. Rhodes James applied to Eden Churchill's famous verdict on Lord Curzon (in ''Great Contemporaries''): "The morning had been golden; the noontime was bronze; and the evening lead. But all was solid, and each was polished until it shone after its fashion".

Both Eden Court, Leamington Spa, built in 1960, and Sir Anthony Eden Way, Warwick, built in the 2000s, are named in his honour.

Online free

* * * * * * * * * * * Peters, A. R. ''Anthony Eden at the Foreign Office 1931-1938''. London: St. Martin's Press, 1986 . * * * Rose, Norman. "The Resignation of Anthony Eden." ''Historical Journal'' 25.4 (1982): 911–931. * Rothwell, V. ''Anthony Eden: a political biography, 1931–1957'' (1992) * Ruane, Kevin. "SEATO, MEDO, and the Baghdad Pact: Anthony Eden, British Foreign Policy and the Collective Defense of Southeast Asia and the Middle East, 1952–1955," ''Diplomacy & Statecraft,'' March 2005, 16#1, pp. 169–199 * Ruane, Kevin. "The Origins of the Eden–Dulles Antagonism: The Yoshida Letter and the Cold War in East Asia 1951–1952." ''Contemporary British History'' 25#1 (2011): 141–156. * Ruane, Kevin, and James Ellison. "Managing the Americans: Anthony Eden, Harold Macmillan and the Pursuit of 'Power-by-Proxy' in the 1950s," ''Contemporary British History,'' Autumn 2004, 18#3, pp 147–167 * * Thorpe, D. R. "Eden, (Robert) Anthony, first earl of Avon (1897–1977)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 2004

online

* Thorpe, D. R. ''Eden: The Life and Times of Anthony Eden, First Earl of Avon, 1897–1977''. London: Chatto and Windus, 2003 . * Trukhanovsky, V.

Anthony Eden

'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1984. * * Watry, David M. ''Diplomacy at the Brink: Eisenhower, Churchill, and Eden in the Cold War'' (LSU Press, 2014)

online review

* Woodward, Llewellyn. ''British Foreign Policy in the Second World War'' (1962) Abridged version of his massive five volume history; focuses on Foreign Office and British missions abroad, under Eden's control. 592pp * Woolner, David. ''Searching for Cooperation in a Troubled World: Cordell Hull, Anthony Eden and Anglo-American Relations, 1933–1938'' (2015). * Woolner, David B. "The Frustrated Idealists: Cordell Hull, Anthony Eden and the Search for Anglo-American Cooperation, 1933– 1938" (PhD dissertation, McGill University, 1996

online free

bibliography pp 373–91.

Search and download private office papers of Eden from The National Archives' website

* *

University of Birmingham Special Collections

The Avon Papers including on the Suez Crisis * * * *

"Prime Ministers in the Post-War World: Anthony Eden"

lecture by Dr David Carlton, given at Gresham College, 10 May 2007 (available for download as video or audio files) * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Eden, Anthony Anthony Eden, 1897 births 1940s missing person cases 1977 deaths 20th-century English memoirists 20th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford British anti-communists British Army personnel of World War I British Secretaries of State for Dominion Affairs British Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs British diplomats Burials in Wiltshire Chancellors of the University of Birmingham Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Conservative Party prime ministers of the United Kingdom Deaths from prostate cancer in England Deputy prime ministers of the United Kingdom Earls of Avon Eden family, Anthony English Anglicans English people of American descent English people of Danish descent English people of Norwegian descent Foreign Office personnel of World War II Honorary air commodores King's Royal Rifle Corps officers Knights of the Garter Leaders of the Conservative Party (UK) Leaders of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Lords Privy Seal Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Military personnel from County Durham Ministers in the Chamberlain peacetime government, 1937–1939 Ministers in the Chamberlain wartime government, 1939–1940 Ministers in the Churchill caretaker government, 1945 Ministers in the Churchill wartime government, 1940–1945 Ministers in the Eden government, 1955–1957 Ministers in the third Churchill government, 1951–1955 Earls created by Elizabeth II People educated at Eton College People educated at Sandroyd School People from County Durham (district) People of the Cold War People of the Suez Crisis Recipients of the Military Cross UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929 UK MPs 1929–1931 UK MPs 1931–1935 UK MPs 1935–1945 UK MPs 1945–1950 UK MPs 1950–1951 UK MPs 1951–1955 UK MPs 1955–1959 War Office personnel in World War II World War II political leaders Younger sons of baronets

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promotion as a young Conservative member of Parliament, he became foreign secretary aged 38, before resigning in protest at Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

's appeasement policy towards Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his overthrow in 194 ...

's Fascist regime in Italy. He again held that position for most of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, and a third time in the early 1950s. Having been deputy to Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

for almost 15 years, Eden succeeded him as the leader of the Conservative Party and prime minister in 1955, and a month later won a general election.

Eden's reputation as a skilled diplomat was overshadowed in 1956 when the United States refused to support the Anglo-French military response to the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

, which critics across party lines regarded as a historic setback for British foreign policy, signalling the end of British influence in the Middle East.David Dutton: ''Anthony Eden. A Life and Reputation'' (London, Arnold, 1997). Most historians argue that he made a series of blunders, especially not realising the depth of American opposition to military action. Two months after ordering an end to the Suez operation, he resigned as Prime Minister on grounds of ill health, and because he was widely suspected of having misled the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

over the degree of collusion with France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

.

Eden is generally considered to be among the least successful of British prime ministers in the 20th century, although two broadly sympathetic biographies have gone some way to shifting the balance of opinion.Robert Rhodes James (1986) ''Anthony Eden''; D. R. Thorpe (2003) ''Eden''.Thorpe (2003) ''Eden''. He was the first out of fifteen British prime ministers to be appointed by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

in her seventy-year reign.

Family

Eden was born on 12 June 1897 at Windlestone Hall, County Durham, into a conservative family oflanded gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

. He was the third of four sons of Sir William Eden, 7th and 5th Baronet, and Sybil Frances Grey, a member of the prominent Grey family of Northumberland

Northumberland ( ) is a ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North East England, on the Anglo-Scottish border, border with Scotland. It is bordered by the North Sea to the east, Tyne and Wear and County Durham to the south, Cumb ...

. Sir William was a former colonel and local magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judi ...

from an old titled family. An eccentric and often foul-tempered man, he was a talented watercolourist, portraitist, and collector of Impressionists

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subjec ...

.Rhodes James 1986, pp. 9–14. Eden's mother had wanted to marry Francis Knollys, who later became a significant Royal adviser, but the match was forbidden by the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

. Although she was a popular figure locally, she had a strained relationship with her children, and her profligacy ruined the family fortunes, meaning Eden's elder brother Tim had to sell Windlestone in 1936. Referring to his parentage, Rab Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden (9 December 1902 – 8 March 1982), also known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politici ...

would later quip that Anthony Eden — a handsome but ill-tempered man — was "half mad baronet, half beautiful woman".

Eden's great-grandfather was William Iremonger, who commanded the 2nd Regiment of Foot during the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

and fought under the Duke of Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

(as he became) at the battle of Vimeiro. He was also descended from Governor Sir Robert Eden, 1st Baronet, of Maryland and, through the Calvert family of Maryland, he was connected to the ancient Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

aristocracy of the Arundell and Howard

Howard is a masculine given name derived from the English surname Howard. ''The Oxford Dictionary of English Christian Names'' notes that "the use of this surname as a christian name is quite recent and there seems to be no particular reason for ...

families (including the Dukes of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The premier non-royal peer, the Duke of Norfolk is additionally the premier duke and earl in the English peerage. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the t ...

), as well as Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

families including as the earls of Carlisle

Earl of Carlisle is a title that has been created three times in the Peerage of England.

History

The first creation came in 1322, when Andrew Harclay, 1st Baron Harclay, was made Earl of Carlisle. He had already been summoned to Parliamen ...

, Effingham and Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

. The Calverts had converted to the Established Church early in the 18th century to regain the proprietorship

A sole proprietorship, also known as a sole tradership, individual entrepreneurship or proprietorship, is a type of enterprise owned and run by only one person and in which there is no legal distinction between the owner and the business entity. ...

of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

. He also had some Danish (the Schaffalitzky de Muckadell family) and Norwegian (the Bie family) descent. Eden was once amused to learn that one of his ancestors had, like Churchill's ancestor the Duke of Marlborough, been the lover of Barbara Castlemaine.

There was speculation for many years that Eden's biological father was the politician and man of letters George Wyndham

George Wyndham, PC (29 August 1863 – 8 June 1913) was a British Conservative politician, statesman, man of letters, and one of The Souls.

Background and education

Wyndham was the elder son of the Honourable Percy Wyndham, third son of G ...

, but this is considered impossible as Wyndham was in South Africa at the time of Eden's conception. Eden's mother was rumoured to have had an affair with Wyndham. His mother and Wyndham exchanged affectionate communications in 1896 but Wyndham was an infrequent visitor to Windlestone and probably did not reciprocate Sybil's feelings. Eden was amused by the rumours but, according to his biographer Rhodes James, probably did not believe them. He did not resemble his siblings, but his father Sir William attributed this to his being "a Grey, not an Eden".

Eden had an elder brother, John, who was killed in action in 1914, and a younger brother, Nicholas, who was killed when the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

blew up and sank at the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland () was a naval battle between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, durin ...

in 1916.

Early life

School

Eden was educated at two independent schools. He attended

Eden was educated at two independent schools. He attended Sandroyd School

Sandroyd School is an independent co-educational preparatory school for day and boarding pupils aged 2 to 13 in the south of Wiltshire, England. The school's main building is Rushmore House, a 19th-century country house which is surrounded by th ...

in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

from 1907 to 1910, where he excelled in languages. He then started at Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

in January 1911. There, he won a Divinity

Divinity (from Latin ) refers to the quality, presence, or nature of that which is divine—a term that, before the rise of monotheism, evoked a broad and dynamic field of sacred power. In the ancient world, divinity was not limited to a single ...

prize and excelled at cricket, rugby and rowing, winning House colours

Color (or colour in Commonwealth English; see spelling differences) is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though color is not an inherent property of matter, color perception is related to an object's light absorpt ...

in the last.

Eden learned French and German on continental holidays and, as a child, is said to have spoken French better than English. Although Eden was able to converse with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

in German in February 1934 and with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai ( zh, s=周恩来, p=Zhōu Ēnlái, w=Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 unti ...

in French at Geneva in 1954, he preferred, out of a sense of professionalism, to have interpreters translate at formal meetings.

Although Eden later claimed to have had no interest in politics until the early 1920s, his biographer writes that his teenage letters and diaries "only really come to life" when discussing the subject. He was a strong, partisan Conservative, thinking his protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

father "a fool" in November 1912 for trying to block his free-trade supporting uncle from a Parliamentary candidacy. He rejoiced in the defeat of Charles Masterman

Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman Privy Council of the United Kingdom, PC Member of parliament, MP (24 October 1873 – 17 November 1927) was a British radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician, intellectual and man of letters. He ...

at a by-election in May 1914 and once astonished his mother on a train journey by telling her the MP and the size of his majority for each constituency through which they passed. By 1914 he was a member of the Eton Society ("Pop").

First World War

During theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Eden's elder brother, Lieutenant John Eden, was killed in action on 17 October 1914, at the age of 26, while serving with the 12th (Prince of Wales's Royal) Lancers. He is buried in Larch Wood (Railway Cutting) Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery in Belgium. His uncle Robin was later shot down and captured whilst serving with the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

.Aster 1976, pp. 5–8.

Volunteering for service in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

, like many others of his generation, Eden served with the 21st (Service) Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (Yeoman Rifles)

The 21st (Service) Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (Yeoman Rifles), (21st KRRC) was an infantry unit recruited by Charles Duncombe, 2nd Earl of Feversham as part of 'Kitchener's Army' in World War I. It served on the Western Front (World War ...

(KRRC), a Kitchener's Army

The New Army, often referred to as Kitchener's Army or, disparagingly, as Kitchener's Mob,

was an (initially) all-volunteer portion of the British Army formed in the United Kingdom from 1914 onwards following the outbreak of hostilities in the F ...

unit, initially recruited mainly from County Durham

County Durham, officially simply Durham, is a ceremonial county in North East England.UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. The county borders Northumberland and Tyne an ...

country labourers, who were increasingly replaced by Londoners after losses at the Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

* Somme, Queensland, Australia

* Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), ...

in mid-1916. He was commissioned as a temporary second lieutenant on 2 November 1915 (antedated to 29 September 1915). His battalion transferred to the Western Front on 4 May 1916 as part of the 41st Division. On 31 May 1916, Eden's younger brother, Midshipman William Nicholas Eden, was killed in action, aged 16, on board during the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland () was a naval battle between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, durin ...

. He is commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial. His brother-in-law, Lord Brooke, was wounded during the war.

One summer night in 1916, near Ploegsteert, Eden had to lead a small raid into an enemy trench to kill or capture enemy soldiers to identify the enemy units opposite. He and his men were pinned down in no man's land under enemy fire, his sergeant seriously wounded in the leg. Eden sent one man back to British lines to fetch another man and a stretcher, and he and three others carried the wounded sergeant back with, as he later put it in his memoirs, a "chilly feeling down our spines", unsure whether the Germans had not seen them in the dark or were chivalrously declining to fire. He omitted to mention that he had been awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

(MC) for the incident, of which he made little mention in his political career. On 18 September 1916, after the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (part of the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (; ), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 Nove ...

), he wrote to his mother, "I have seen things lately that I am not likely to forget". On 3 October, he was appointed an adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an Officer (armed forces), officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of “human resources” in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed ...

, with the rank of temporary lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

for the duration of that appointment. At the age of 19, he was the youngest adjutant on the Western Front.

Eden's MC was gazetted in the 1917 Birthday Honours list. His battalion fought at Messines Ridge in June 1917. On 1 July 1917, Eden was confirmed as a temporary lieutenant, relinquishing his appointment as adjutant three days later. His battalion fought in the first few days of Third Battle of Ypres

The Third Battle of Ypres (; ; ), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele ( ), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by the Allies against the German Empire. The battle took place on the Western Front, from July to November 1917, f ...

(31 July – 4 August). Between 20 and 23 September 1917 his battalion spent a few days on coastal defence on the Franco-Belgian border.

On 19 November, Eden was transferred to the General Staff as a General Staff Officer Grade 3 (GSO3), with the temporary rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

. He served at Second Army HQ between mid-November 1917 and 8 March 1918, missing out on service in Italy (as the 41st Division had been transferred there after the Italian Second Army was defeated at the Battle of Caporetto

The Battle of Kobarid (also known as the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, the Battle of Caporetto or the Battle of Karfreit) took place on the Italian front of World War I.

The battle was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Central P ...

). Eden returned to the Western Front as a major German offensive was clearly imminent, only for his former battalion to be disbanded to help alleviate the British Army's acute manpower shortage. Although David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, then the British prime minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet, and selects its ministers. Modern pri ...

, was one of the few politicians of whom Eden reported frontline soldiers speaking highly, he wrote to his sister (23 December 1917) in disgust at his "wait and see twaddle" in declining to extend conscription to Ireland.Rhodes James 1986, p. 52.

In March 1918, during the German spring offensive

The German spring offensive, also known as ''Kaiserschlacht'' ("Kaiser's Battle") or the Ludendorff offensive, was a series of German Empire, German attacks along the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during the World War I, First Wor ...

, he was stationed near La Fère

La Fère () is a commune in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in France. It was once famous for its military school (1720), one the oldest commissioned for instructing ordnance officers.

History

During World War II, Nazi Germany operat ...

on the Oise

Oise ( ; ; ) is a department in the north of France. It is named after the river Oise. Inhabitants of the department are called ''Oisiens'' () or ''Isariens'', after the Latin name for the river, Isara. It had a population of 829,419 in 2019.< ...

, opposite Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

, as he learned at a conference in 1935.Rhodes James 1986, p. 55. At one point, when brigade HQ was bombed by German aircraft, his companion told him, "There now, you have had your first taste of the next war." On 26 May 1918, he was appointed brigade major

A brigade major was the chief of staff of a brigade in the British Army. They most commonly held the rank of major, although the appointment was also held by captains, and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section direct ...

of the 198th Infantry Brigade, part of the 66th Division. At the age of 20, Eden was the youngest brigade major in the British Army.

He considered standing for Parliament at the end of the war, but the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

was called too early for that to be possible. After the Armistice with Germany {{Short description, none

This is a list of armistices signed by the German Empire (1871–1918) or Nazi Germany (1933–1945). An armistice is a temporary agreement to cease hostilities. The period of an armistice may be used to negotiate a peace t ...

, he spent the winter of 1918–1919 in the Ardennes with his brigade; on 28 March 1919, he transferred to be brigade major of the 99th Infantry Brigade. Eden contemplated applying for a commission in the Regular Army, but these were very hard to come by with the army contracting so rapidly. He initially shrugged off his mother's suggestion of studying at Oxford. He also rejected the thought of becoming a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

. His preferred career alternatives at this stage were standing for Parliament for Bishop Auckland, the Civil Service in East Africa or the Foreign Office. He was demobilised on 13 June 1919. He retained the rank of captain.

Oxford

Eden had dabbled in the study of Turkish with a family friend.Aster 1976, pp. 8–9. After the war, he studiedOriental Languages

Asia is home to hundreds of languages comprising several families and some unrelated isolates. The most spoken language families on the continent include Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Japonic, Dravidian, Indo-European, Afroasiatic, Turkic, ...

(Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

) at Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

, starting in October 1919.Rhodes James 1986, pp. 59–62. Persian was his main and Arabic his secondary language. He studied under Richard Paset Dewhurst and David Samuel Margoliouth.

At Oxford, Eden took no part in student politics, and his main leisure interest at the time was art. Eden was in the Oxford University Dramatic Society

The Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS) is the principal funding body and provider of theatrical services to the many independent student productions put on by students in Oxford, England. Not all student productions at Oxford University a ...

and President of the Asiatic Society. Along with Lord David Cecil

Lord Edward Christian David Gascoyne-Cecil, CH (9 April 1902 – 1 January 1986) was a British biographer, historian, and scholar. He held the style of "Lord" by courtesy as a younger son of a marquess.

Early life and studies

David Cecil was ...

and R. E. Gathorne-Hardy he founded the Uffizi Society, of which he later became president. Possibly under the influence of his father, Eden gave a paper on Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne ( , , ; ; ; 19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French Post-Impressionism, Post-Impressionist painter whose work introduced new modes of representation, influenced avant-garde artistic movements of the early 20th century a ...

, whose work was not yet widely appreciated. Eden was already collecting paintings.

In July 1920, still an undergraduate, Eden was recalled to military service as a lieutenant in the 6th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry

The Durham Light Infantry (DLI) was a light infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 to 1968. It was formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 68th (Durham) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry) and ...

. In the spring of 1921, once again as a temporary captain, he commanded local defence forces at Spennymoor as serious industrial unrest seemed possible.Rhodes James 1986, p. 62. He again relinquished his commission on 8 July. He graduated from Oxford in June 1922 with a Double First

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a Grading in education, grading structure used for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and Master's degree#Integrated Masters Degree, integrated master's degrees in the United Kingd ...

. He continued to serve as an officer in the Territorial Army until May 1923.

Early political career, 1922–1931

1922–1924

Captain Eden, as he was still known, was selected to contest Spennymoor, as aConservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

. At first, he had hoped to win with some Liberal Party (UK), Liberal support, as the Conservatives were still supporting Lloyd George ministry, Lloyd George's coalition government, but by the time of the 1922 United Kingdom general election, November 1922 general election, it was clear that the surge in the Labour Party (UK), Labour vote made that unlikely. His main sponsor was the Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, 7th Marquess of Londonderry, Marquess of Londonderry, a local coal owner. The seat went from Liberal to Labour.

Eden's father had died on 20 February 1915. As a younger son, he had inherited capital of £7,675 and in 1922 he had a private income of £706 after tax (approximately £375,000 and £35,000 at 2014 prices).

Eden read the writings of Lord Curzon, and was hoping to emulate him by entering politics with a view to specialising in foreign affairs. Eden married Beatrice Beckett in the autumn of 1923, and after a two-day honeymoon in Essex, he was selected to fight Warwick and Leamington for a by-election in November 1923. His Labour opponent, Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick, was, by coincidence, his sister Elfrida's mother-in-law, and also mother to his wife's step-mother, Marjorie Blanche Eve Beckett, née Greville. On 16 November 1923, during the by-election campaign, Parliament was dissolved for the 1923 United Kingdom general election, December 1923 general election. He was elected to Parliament at the age of twenty-six.Rhodes James 1986, pp. 78–79.

The first Labour Government, under Ramsay MacDonald, took office in January 1924. Eden's maiden speech (19 February 1924) was a controversial attack on Labour's defence policy, and was heckled; he was thereafter careful to speak only after deep preparation. He later reprinted the speech in the collection ''Foreign Affairs'' (1939) to give the impression that he had been a consistent advocate of air strength. Eden admired H. H. Asquith, then in his final year in the Commons, for his lucidity and brevity. On 1 April 1924, Eden spoke to urge Turkey–United Kingdom relations, Anglo-Turkish friendship and the ratification of the Treaty of Lausanne, which had been signed in July 1923.Aster 1976, pp. 12–13.

1924–1929

The Conservatives returned to power at the 1924 United Kingdom general election, 1924 general election. In January 1925, Eden, disappointed not to have been offered a position, went on a tour of the Middle East and met Faisal I of Iraq, Emir Feisal of Iraq. Feisal reminded him of the "Nicholas II of Russia, Czar of Russia & (I) suspect that his fate may be similar" (a similar fate indeed befell the Iraqi Royal Family 14 July Revolution, in 1958). During a visit to Pahlavi Iran he inspected the Abadan Refinery, which he likened to "a Swansea on a small scale".Rhodes James 1986, pp. 84–86. Eden was appointed Parliamentary Private Secretary to Godfrey Locker-Lampson, Under-Secretary at the Home Office (17 February 1925), serving under Home Secretary William Joynson Hicks.Rhodes James 1986, p. 85. In July 1925, Eden went on a second trip to Canada, Australia and India. He wrote articles for ''The Yorkshire Post'', controlled by his father-in-law Sir Gervase Beckett, under the pseudonym "Backbencher". In September 1925, he represented the ''Yorkshire Post'' at the Imperial Conference at Melbourne. Eden continued to be PPS to Locker-Lampson when the latter was appointed Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office in December 1925. He distinguished himself with a speech on the Middle East (21 December 1925), that called for the readjustment of Iraqi frontiers in favour of Turkey but also for a continued Mandatory Iraq, British mandate, rather than a "scuttle". Eden ended his speech by calling for Anglo-Turkish friendship. On 23 March 1926, he spoke to urge the League of Nations to admit Germany, which would happen the following year. In July 1926 he became PPS to the Foreign Secretary Sir Austen Chamberlain. Besides supplementing his parliamentary income of around £300 a year at that time by writing and journalism, he published a book about his travels, ''Places in the Sun'' in 1926 that was highly critical of the detrimental effect of socialism on Australia and to which Stanley Baldwin wrote a foreword.Rhodes James 1986, p. 103. In November 1928, with Austen Chamberlain away on a voyage to recover his health, Eden had to speak for the government in a debate on a recent Anglo-French naval agreement in reply to Ramsay MacDonald, then Leader of the Opposition. According to Austen Chamberlain, he would have been promoted to his first ministerial job, Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, if the Conservatives had won the 1929 United Kingdom general election, 1929 election.Rhodes James 1986, p. 101.1929–1931

The 1929 general election was the only time that Eden received less than 50% of the vote at Warwick. After the Conservative defeat, he joined a progressive group of younger politicians consisting of Oliver Stanley, William Ormsby-Gore, 4th Baron Harlech, William Ormsby-Gore and the future Speaker of the House of Commons (United Kingdom), Speaker William Morrison, 1st Viscount Dunrossil, W.S. "Shakes" Morrison. Another member was Noel Skelton, who had before his death coined the phrase "property-owning democracy", which Eden was later to popularise as a Conservative Party aspiration. Eden advocated co-partnership in industry between managers and workers, whom he wanted to be given shares. In opposition between 1929 and 1931, Eden worked as a City broker for Harry Lucas, a firm that was eventually absorbed into S. G. Warburg & Co.Foreign Affairs Minister, 1931–1935

In August 1931, Eden held his first ministerial office as Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Under-Secretary for foreign policy, Foreign Affairs in Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald's National Government (United Kingdom), National Government. Initially, the office was held by Rufus Isaacs, 1st Marquess of Reading, Lord Reading (in the House of Lords), but Sir John Simon held the position from November 1931. Like many of his generation who had served in the First World War, Eden was strongly antiwar, and he strove to work through the League of Nations to preserve European peace. The government proposed World Disarmament Conference, measures superseding the post-war Versailles Treaty to allow Germany to rearm (albeit replacing its Reichswehr, small professional army with a short-service militia) and to reduce French armaments.Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

criticised the policy sharply in the House of Commons on 23 March 1933, opposing "undue" French disarmament as this might require Britain to take action to enforce peace under the 1925 Locarno Treaty. Eden, replying for the government, dismissed Churchill's speech as exaggerated and unconstructive and commented that land disarmament had yet to make the same progress as naval disarmament at the Washington Naval Conference, Washington and London Naval Treaty, London Treaties and arguing that French disarmament was needed to "secure for Europe that period of appeasement which is needed". Eden's speech was met with approval by the House of Commons. Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

commented shortly afterwards, "That young man is coming along rapidly; not only can he make a good speech but he has a good head and what advice he gives is listened to by the Cabinet".

Eden later wrote that in the early 1930s, the word "appeasement" was still used in its correct sense (from the ''Oxford English Dictionary'') of seeking to settle strife. Only later in the decade would it come to acquire a pejorative meaning of acceding to bullying demands.

He was appointed Lord Privy Seal in January 1934, a position that was combined with the newly created office of Minister for League of Nations Affairs. As Lord Privy Seal, Eden was sworn of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, Privy Council in the 1934 Birthday Honours.

On 25 March 1935, accompanying Sir John Simon, Eden met Hitler in Berlin and raised a weak protest after Hitler restored conscription against the Versailles Treaty. The same month, Eden also met Stalin and Maxim Litvinov, Litvinov in Moscow.

He entered the cabinet for the first time when Stanley Baldwin formed his third administration in June 1935. Eden later came to recognise that peace could not be maintained by appeasement of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. He privately opposed the policy of the Foreign Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, 1st Viscount Templewood, Samuel Hoare, of trying to appease Italy during its Second Italo-Abyssinian War, invasion of Abyssinia (now called Ethiopia) in 1935. After Hoare resigned after the failure of the Hoare-Laval Pact, Eden succeeded him as Foreign Secretary. When Eden had his first audience with King George V, the King is said to have remarked, "No more coals to Newcastle, no more Hoares to Paris".

In 1935, Baldwin sent Eden on a two-day visit to see Hitler, with whom he dined twice. Litvinov's biographer John Holroyd-Doveton believed that Eden shares with Molotov the experience of being the only people to have had dinner with Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin although not on the same occasion. Hitler never had dinner with any of the other three leaders, and as far as is known, Stalin never saw Hitler.

Attlee was convinced that public opinion could stop Hitler, saying in a speech in the House of Commons:"We believe in a League system in which the whole world would be ranged against an aggressor. If it is shown that someone is proposing to break the peace let us bring the whole world opinion against her".However, Eden was more realistic and correctly predicted:

"Hitler could only be stopped. There may be the only course of action open to us to join with those powers who are members of the League in affirming our faith in that institution and to uphold the principles of the Covenant of the League of Nations, Covenant. It may be the spectacle of the great powers of the League reaffirming their intentions to collaborate more closely than ever is not only the sole means of bringing home to Germany that the inevitable effect of persisting in her present policy will be to consolidate against her all those nations which believe in collective security but will also tend to give confidence to those less powerful nations which through fear of Germany's growing strength might well otherwise be drawn into her orbit".Eden proceeded to Moscow for talks with Stalin and Soviet Minister Litvinov, Most of the British cabinet feared of the spread of Bolshevism to Britain and hated the Soviets, but Eden went with an open mind and had a respect for Stalin:

"(Stalin's) personality made itself felt without exaggeration. He had natural good manners, perhaps a Georgian inheritance. Though I knew the man was without mercy, I respected the quality of his mind and even felt a sympathy I have never been able to analyse. Perhaps it was because of the pragmatic approach. I cannot believe he had any affinity to Marx. Certainly no one could have been less doctrinaire".Eden felt sure most of his colleagues would feel unenthusiastic about any favourable report on the Soviet Union but felt certain to be correct. The representatives of both governments were happy to note that as a result of a full and frank exchange of views, there is at present no conflict of interest between them on any of the major issues of international policy, which provided a firm foundation between them in the cause of peace. Eden stated when he sent the communiqué to his government, he thought that his colleagues would be "Unenthusiastic, I am sure". John Holroyd-Doveton argued that Eden would be proved right. Not only was the French army defeated by the German army, but France broke its treaty with Britain by seeking an armistice with Germany. In contrast, the Red Army finally defeated the Wehrmacht. At that stage in his career, Eden was considered as something of a leader of fashion. He regularly wore a Homburg (hat), Homburg hat, which became known in Britain as an "Anthony Eden hat, Anthony Eden".

Foreign Secretary and resignation, 1935–1938

Eden became Foreign Secretary after Samuel Hoare, 1st Viscount Templewood, Samuel Hoare had resigned after the collapse of the Hoare–Laval Pact. Britain had to adjust its foreign policy to face the rise of the fascist powers of Nazi Germany and Hitler as well as Italian fascism andMussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his overthrow in 194 ...

. He supported the policy of non-interference in the Spanish Civil War through conferences such as the Nyon Conference and supported Neville Chamberlain#Prime Minister (1937–1940), Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and National Government (1937–1939), his National Government in their European foreign policy of the Chamberlain ministry, efforts to preserve peace through seemingly reasonable concessions to Nazi Germany.

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Italian-Ethiopian War was brewing, and Eden tried in vain to persuade Mussolini to submit the dispute to the League of Nations. The Italian dictator scoffed at Eden publicly as "the best dressed fool in Europe". Eden did not protest when Britain and France failed to oppose Hitler's reoccupation of the Rhineland on 7 March 1936. When the French government (Albert Sarraut#Sarraut's Second Ministry, 24 January – 4 June 1936, Sarraut II government) requested a meeting with a view to some kind of military action in response to Hitler's occupation, Eden's statement firmly ruled out any military assistance to France.