Anne Boleyn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was

Anne's father continued his diplomatic career under Henry VIII. In Europe, his charm won many admirers, including Margaret of Austria, daughter of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. During this period, Margaret ruled the Netherlands on her nephew Charles's behalf and was so impressed with Boleyn that she offered his daughter Anne a place in her household. Ordinarily, a girl had to be 12 years old to have such an honour, but Anne may have been younger, as Margaret affectionately called her . Anne made a good impression in the Netherlands with her manners and studiousness; Margaret reported that she was well spoken and pleasant for her young age, and told Thomas that his daughter was "so presentable and so pleasant, considering her youthful age, that I am more beholden to you for sending her to me, than you to me" (E. W. Ives, op.cit.). Anne stayed at the Court of Savoy in

Anne's father continued his diplomatic career under Henry VIII. In Europe, his charm won many admirers, including Margaret of Austria, daughter of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. During this period, Margaret ruled the Netherlands on her nephew Charles's behalf and was so impressed with Boleyn that she offered his daughter Anne a place in her household. Ordinarily, a girl had to be 12 years old to have such an honour, but Anne may have been younger, as Margaret affectionately called her . Anne made a good impression in the Netherlands with her manners and studiousness; Margaret reported that she was well spoken and pleasant for her young age, and told Thomas that his daughter was "so presentable and so pleasant, considering her youthful age, that I am more beholden to you for sending her to me, than you to me" (E. W. Ives, op.cit.). Anne stayed at the Court of Savoy in

As Clement was at that time a prisoner of Charles V, the

As Clement was at that time a prisoner of Charles V, the

Catherine was formally stripped of her title as queen and Anne was consequently crowned queen consort on 1 June 1533 in a magnificent ceremony at Westminster Abbey with a banquet afterwards. She was the last queen consort of England to be crowned separately from her husband. Unlike any other queen consort, Anne was crowned with St Edward's Crown, which had previously been used to crown only monarchs. Historian Alice Hunt suggests that this was done because Anne's pregnancy was visible by then and the child was presumed to be male.Alice Hunt, ''The Drama of Coronation: Medieval Ceremony in Early Modern England'', Cambridge University Press, 2008. On the previous day, Anne had taken part in an elaborate procession through the streets of London seated in a litter of "white cloth of gold" that rested on two palfreys clothed to the ground in white damask, while the barons of the Cinque Ports held a canopy of cloth of gold over her head. In accordance with tradition, she wore white, and on her head, a gold coronet beneath which her long dark hair hung down freely. The public's response to her appearance was lukewarm.

Meanwhile, the House of Commons had forbidden all appeals to Rome and exacted the penalties of ''

Catherine was formally stripped of her title as queen and Anne was consequently crowned queen consort on 1 June 1533 in a magnificent ceremony at Westminster Abbey with a banquet afterwards. She was the last queen consort of England to be crowned separately from her husband. Unlike any other queen consort, Anne was crowned with St Edward's Crown, which had previously been used to crown only monarchs. Historian Alice Hunt suggests that this was done because Anne's pregnancy was visible by then and the child was presumed to be male.Alice Hunt, ''The Drama of Coronation: Medieval Ceremony in Early Modern England'', Cambridge University Press, 2008. On the previous day, Anne had taken part in an elaborate procession through the streets of London seated in a litter of "white cloth of gold" that rested on two palfreys clothed to the ground in white damask, while the barons of the Cinque Ports held a canopy of cloth of gold over her head. In accordance with tradition, she wore white, and on her head, a gold coronet beneath which her long dark hair hung down freely. The public's response to her appearance was lukewarm.

Meanwhile, the House of Commons had forbidden all appeals to Rome and exacted the penalties of ''

The infant princess was given a splendid christening, but Anne feared that Catherine's daughter, Mary, now stripped of her title of princess and labelled a bastard, posed a threat to Elizabeth's position. Henry soothed his wife's fears by separating Mary from her many servants and sending her to Hatfield House, where Elizabeth would live with her own sizeable staff of servants and the country air was thought better for the baby's health. Anne frequently visited her daughter at Hatfield and other residences.

The new queen had a larger staff of servants than Catherine. There were more than 250 servants to tend to her personal needs, from priests to stable boys, and more than 60 maids-of-honour who served her and accompanied her to social events. She also employed several priests who acted as her

The infant princess was given a splendid christening, but Anne feared that Catherine's daughter, Mary, now stripped of her title of princess and labelled a bastard, posed a threat to Elizabeth's position. Henry soothed his wife's fears by separating Mary from her many servants and sending her to Hatfield House, where Elizabeth would live with her own sizeable staff of servants and the country air was thought better for the baby's health. Anne frequently visited her daughter at Hatfield and other residences.

The new queen had a larger staff of servants than Catherine. There were more than 250 servants to tend to her personal needs, from priests to stable boys, and more than 60 maids-of-honour who served her and accompanied her to social events. She also employed several priests who acted as her

Queen of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disag ...

. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key figure in the political and religious upheaval that marked the start of the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and po ...

. Anne was the daughter of Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire, and his wife, Lady Elizabeth Howard, and was educated in the Netherlands and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, largely as a maid of honour to Queen Claude of France. Anne returned to England in early 1522, to marry her Irish cousin James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormond

James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormond and 2nd Earl of Ossory ( – 1546), known as the Lame (Irish: ''Bacach''), was in 1541 confirmed as Earl of Ormond thereby ending the dispute over the Ormond earldom between his father, Piers Butler, 8th Earl o ...

; the marriage plans were broken off, and instead, she secured a post at court as maid of honour to Henry VIII's wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Early in 1523, Anne was secretly betrothed to Henry Percy, son of Henry Percy, 5th Earl of Northumberland, but the betrothal was broken off when the Earl refused to support their engagement. Cardinal Thomas Wolsey refused the match in January 1524 and Anne was sent home to Hever Castle. In February or March 1526 Henry VIII began his pursuit of Anne. She resisted his attempts to seduce her, refusing to become his mistress, as her sister Mary had previously been. Henry soon focused his desires on annulling his marriage to Catherine so he would be free to marry Anne. Wolsey failed to obtain an annulment of Henry's marriage from Pope Clement VII, and when it became clear that Clement would not annul the marriage, Henry and his advisers, such as Thomas Cromwell, began the breaking of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

's power in England and closing the monasteries and the nunneries. In 1532, Henry made Anne the Marquess of Pembroke.

Henry and Anne formally married on 25 January 1533, after a secret wedding on 14 November 1532. On 23 May 1533, the newly appointed Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer declared Henry and Catherine's marriage null and void; five days later, he declared Henry and Anne's marriage valid. Shortly afterwards, Clement excommunicated Henry and Cranmer. As a result of this marriage and these excommunications, the first break between the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

and the Catholic Church took place, and the king took control of the Church of England. Anne was crowned Queen of England on 1 June 1533. On 7 September, she gave birth to the future Queen Elizabeth I. Henry was disappointed to have a daughter rather than a son but hoped a son would follow and professed to love Elizabeth. Anne subsequently had three miscarriages and by March 1536, Henry was courting Jane Seymour. In order to marry Seymour, Henry had to find reasons to end the marriage to Anne.

Henry VIII had Anne investigated for high treason in April 1536. On 2 May, she was arrested and sent to the Tower of London, where she was tried before a jury of peers, including Henry Percy, her former betrothed, and her uncle Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk; she was convicted on 15 May and beheaded four days later. Modern historians view the charges against her, which included adultery, incest and plotting to kill the king, as unconvincing.

After her daughter, Elizabeth, became Queen in 1558, Anne became venerated as a martyr and heroine of the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and po ...

, particularly through the written works of John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the su ...

. She has inspired, or been mentioned in, many artistic and cultural works and retained her hold on the popular imagination. She has been called "the most influential and important queen consort England has ever had",Ives, p. xv. as she provided the occasion for Henry VIII to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and declare the English church's independence from the Vatican.

Early years

Anne was the daughter of Thomas Boleyn, later Earl of Wiltshire and Earl of Ormond, and his wife, Lady Elizabeth Howard, who was the daughter of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk and a paternal aunt of the poet Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. Thomas Boleyn was a well-respected diplomat with a gift for languages; he was also a favourite of Henry VII of England, who sent him on many diplomatic missions abroad. Anne and her siblings grew up at Hever Castle inKent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. They were born in Norfolk at the Boleyn home at Blickling. A lack of parish records has made it impossible to establish Anne's date of birth. Contemporary evidence is contradictory, with several dates having been put forward by various historians. An Italian, writing in 1600, suggested that she had been born in 1499, while Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

's son-in-law William Roper

William Roper ( – 4 January 1578) was an English lawyer and member of Parliament. The son of a Kentish gentleman, he married Margaret, daughter of Sir Thomas More. He wrote a highly regarded biography of his father-in-law.

Life

William Roper ...

gave a date of 1512. Her birth is widely accepted by scholars and historians as most likely between 1501 and 1507.

As with Anne, it is uncertain when her two siblings were born, but it seems clear that her sister Mary was older than Anne. Mary's children clearly believed their mother was the elder sister. Mary's grandson claimed the Ormonde title in 1596 on the basis that she was the elder daughter, which Elizabeth I accepted.Fraser, p.119. Their brother George was born around 1504.

The academic debate about Anne's birth date focuses on two key dates: c. 1501 and c. 1507. Eric Ives

Eric William Ives (12 July 1931 – 25 September 2012) was a British historian who was an expert on the Tudor period, and a university administrator. He was Emeritus Professor of English History at the University of Birmingham.

Early life

...

, a British historian and legal expert, advocates 1501, while Retha Warnicke, an American scholar who has also written a biography of Anne, prefers 1507. The key piece of surviving written evidence is a letter Anne wrote sometime in 1514. She wrote it in French to her father, who was still living in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

while Anne was completing her education at Mechelen

Mechelen (; french: Malines ; traditional English name: MechlinMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical contex ...

, in the Burgundian Netherlands, now Belgium. Ives argues that the style of the letter and its mature handwriting prove that Anne must have been about 13 at the time of its composition, while Warnicke argues that the numerous misspellings and grammar errors show that the letter was written by a child. In Ives's view, this would also be around the minimum age that a girl could be a maid of honour, as Anne was to the regent, Margaret of Austria. This is supported by claims of a chronicler from the late 16th century, who wrote that Anne was 20 when she returned from France. These findings are contested by Warnicke in several books and articles, and the evidence does not conclusively support either date.

Two independent contemporary sources support the 1507 date. Author Gareth Russell wrote a summary of the evidence and relates that Jane Dormer, Duchess of Feria

Duke of Feria ( es, Duque de Feria) is a hereditary title in the Peerage of Spain accompanied by the dignity of Grandee, granted in 1567 by Philip II to Gómez Suárez de Figueroa, 5th Count of Feria.

The name makes reference to the town of Fer ...

, wrote her memoirs shortly before her death in 1612. The former lady-in-waiting and confidante to Queen Mary I wrote of Anne Boleyn: "She was convicted and condemned and was not yet twenty-nine years of age." William Camden wrote a history of the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

and was granted access to the private papers of Lord Burghley and to the state archives. In that history, in the chapter dealing with Elizabeth's early life, he records in the margin that Anne was born in MDVII (1507).

Anne's great-great-great-grandparents included a Lord Mayor of London, a duke, an earl, two aristocratic ladies and a knight. One of them, Geoffrey Boleyn, had been a mercer and wool merchant before becoming Lord Mayor.Ives, p. 3. The Boleyn family originally came from Blickling in Norfolk, north of Norwich. Anne's relatives included the Howards, one of the preeminent families in England; and Anne's ancestors included King Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Duchy of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and D ...

. According to Eric Ives, she was certainly of more noble birth than Jane Seymour and Catherine Parr, Henry VIII's other English wives. The spelling of the Boleyn name was variable, as common at the time. Sometimes it was written as ''Bullen'', hence the bull's heads which formed part of her family arms.Fraser, p.115.

At the court of Margaret of Austria in the Netherlands, Anne is listed as ''Boullan''. From there she signed the letter to her father as ''Anna de Boullan''.Ives, plate 14. She was also called "Anna Bolina"; this Latinised form is used in most portraits of her.

Anne's early education was typical for women of her class. In 1513, she was invited to join the schoolroom of Margaret of Austria and her four wards. Her academic education was limited to arithmetic, her family genealogy, grammar, history, reading, spelling and writing. She also developed domestic skills such as dancing, embroidery, good manners, household management, music, needlework and singing. Anne learned to play games, such as cards, chess and dice. She was also taught archery, falconry, horseback riding and hunting.

The Netherlands and France

Anne's father continued his diplomatic career under Henry VIII. In Europe, his charm won many admirers, including Margaret of Austria, daughter of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. During this period, Margaret ruled the Netherlands on her nephew Charles's behalf and was so impressed with Boleyn that she offered his daughter Anne a place in her household. Ordinarily, a girl had to be 12 years old to have such an honour, but Anne may have been younger, as Margaret affectionately called her . Anne made a good impression in the Netherlands with her manners and studiousness; Margaret reported that she was well spoken and pleasant for her young age, and told Thomas that his daughter was "so presentable and so pleasant, considering her youthful age, that I am more beholden to you for sending her to me, than you to me" (E. W. Ives, op.cit.). Anne stayed at the Court of Savoy in

Anne's father continued his diplomatic career under Henry VIII. In Europe, his charm won many admirers, including Margaret of Austria, daughter of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. During this period, Margaret ruled the Netherlands on her nephew Charles's behalf and was so impressed with Boleyn that she offered his daughter Anne a place in her household. Ordinarily, a girl had to be 12 years old to have such an honour, but Anne may have been younger, as Margaret affectionately called her . Anne made a good impression in the Netherlands with her manners and studiousness; Margaret reported that she was well spoken and pleasant for her young age, and told Thomas that his daughter was "so presentable and so pleasant, considering her youthful age, that I am more beholden to you for sending her to me, than you to me" (E. W. Ives, op.cit.). Anne stayed at the Court of Savoy in Mechelen

Mechelen (; french: Malines ; traditional English name: MechlinMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical contex ...

from spring 1513 until her father arranged for her to attend Henry VIII's sister Mary, who was about to marry Louis XII of France

Louis XII (27 June 14621 January 1515), was King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Maria of Cleves, he succeeded his 2nd cousin once removed and brother in law at the tim ...

in October 1514.

In France, Anne was a maid of honour to Queen Mary, and then to Mary's 15-year-old stepdaughter Queen Claude, with whom she stayed nearly seven years.Fraser, p. 121. In the Queen's household, she completed her study of French and developed interests in art, fashion, illuminated manuscripts, literature, music, poetry and religious philosophy. She also acquired knowledge of French culture, dance, etiquette, literature, music and poetry; and gained experience in flirtation and courtly love. Though all knowledge of Anne's experiences in the French court is conjecture, even Ives suggests that she was likely to have made the acquaintance of King Francis I's sister, Marguerite de Navarre, a patron of humanists and reformers. Marguerite de Navarre was also an author in her own right, and her works include elements of Christian mysticism and reform that verged on heresy, though she was protected by her status as the French king's beloved sister. She or her circle may have encouraged Anne's interest in religious reform, as well as in poetry and literature. Anne's education in France proved itself in later years, inspiring many new trends among the ladies and courtiers of England. It may have been instrumental in pressing their King toward the culture-shattering contretemps with the Papacy. William Forrest, author of a contemporary poem about Catherine of Aragon, complimented Anne's "passing excellent" skill as a dancer. "Here", he wrote, "was fresh young damsel, that could trip and go."

At the court of Henry VIII: 1522–1533

Anne was recalled to marry her Irish cousin, James Butler, a young man several years older than she who was living at the English court. The marriage was intended to settle a dispute over the title and estates of the Earldom of Ormond. The 7th Earl of Ormond died in 1515, leaving his daughters,Margaret Boleyn

Lady Margaret Boleyn (c. 1454 – 1539) was an Irish noblewoman, the daughter and co-heiress of Thomas Butler, 7th Earl of Ormond. She married Sir William Boleyn and through her eldest son Sir Thomas Boleyn, was the paternal grandmo ...

and Anne St Leger, as co-heiresses. In Ireland, the great-great-grandson of the third earl, Sir Piers Butler, contested the will and claimed the earldom himself. He was already in possession of Kilkenny Castle, the earls' ancestral seat. Sir Thomas Boleyn, being the son of the eldest daughter, believed the title properly belonged to him and protested to his brother-in-law, the Duke of Norfolk, who spoke to Henry about the matter. Henry, fearful the dispute could ignite civil war in Ireland, sought to resolve the matter by arranging an alliance between Piers's son, James and Anne Boleyn. She would bring her Ormond inheritance as dowry and thus end the dispute. The plan ended in failure, perhaps because Sir Thomas hoped for a grander marriage for his daughter or because he himself coveted the titles. Whatever the reason, the marriage negotiations came to a complete halt. James Butler later married Lady Joan Fitzgerald, daughter and heiress of James FitzGerald, 10th Earl of Desmond and Amy O'Brien.

Mary Boleyn

Mary Boleyn, also known as Lady Mary, (c. 1499 – 19 July 1543) was the sister of English queen consort Anne Boleyn, whose family enjoyed considerable influence during the reign of King Henry VIII.

Mary was one of the mistresses of Henry VII ...

, Anne Boleyn's older sister, had been recalled from France in late 1519, ostensibly to end her affairs with the French king and his courtiers. She married William Carey, a minor noble, in February 1520, at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwic ...

, with Henry VIII in attendance. Soon after, Mary became the English King's mistress. Historians dispute Henry VIII's paternity of one or both of Mary Boleyn's children born during this marriage. ''Henry VIII: The King and His Court'', by Alison Weir, questions the paternity of Henry Carey; Dr. G.W. Bernard (''The King's Reformation'') and Joanna Denny

Joanna Denny (died 2006) was a historian and author specialising in the court of Henry VIII of England. Her books include '' Katherine Howard: A Tudor Conspiracy'' and '' Anne Boleyn.'' Her books are usually considered to be sympathetic towards ...

(''Anne Boleyn: A New Life of England's Tragic Queen'') argue that Henry VIII was their father. Henry did not acknowledge either child, but he did recognize his son Henry Fitzroy, his illegitimate son by Elizabeth Blount, Lady Talboys.

Anne made her début at the ''Château Vert'' (Green Castle) pageant in honour of the imperial ambassadors on 4 March 1522, playing "Perseverance" (one of the characters in the play). There she took part in an elaborate dance accompanying Henry's younger sister Mary, several other ladies of the court and her sister. All wore gowns of white satin embroidered with gold thread. She quickly established herself as one of the most stylish and accomplished women at the court, and soon a number of young men were competing for her.

Warnicke writes that Anne was "the perfect woman courtier... her carriage was graceful and her French clothes were pleasing and stylish; she danced with ease, had a pleasant singing voice, played the lute and several other musical instruments well, and spoke French fluently... A remarkable, intelligent, quick-witted young noblewoman... that first drew people into conversation with her and then amused and entertained them. In short, her energy and vitality made her the center of attention in any social gathering." Henry VIII's biographer J. J. Scarisbrick

Professor John Joseph Scarisbrick MBE FRHistS (often shortened to J.J. Scarisbrick) is a British historian who taught at the University of Warwick. He is also noted as the co-founder with his wife Nuala Scarisbrick of Life, a British anti-aborti ...

adds that Anne "revelled in" the attention she received from her admirers.

During this time, Anne was courted by Henry Percy, son of the Earl of Northumberland, and entered into a secret betrothal with him. Thomas Wolsey's gentleman usher Gentleman Usher is a title for some officers of the Royal Household of the United Kingdom. See List of Gentlemen Ushers for a list of office-holders.

Gentlemen Ushers as servants Historical

Gentlemen Ushers were originally a class of servants f ...

, George Cavendish, maintained the two had not been lovers. The romance was broken off when Percy's father refused to support their engagement. Wolsey refused the match for several conjectured reasons. According to Cavendish, Anne was sent from court to her family's countryside estates, but it is not known for how long. Upon her return to court, she again entered the service of Catherine of Aragon. Percy was married to Lady Mary Talbot

The word ''lady'' is a term for a girl or woman, with various connotations. Once used to describe only women of a high social class or status, the equivalent of lord, now it may refer to any adult woman, as gentleman can be used for men. Inform ...

, to whom he had been betrothed since adolescence.

Before marrying Henry VIII, Anne had befriended Sir Thomas Wyatt

Sir Thomas Wyatt (150311 October 1542) was a 16th-century English politician, ambassador, and lyric poet credited with introducing the sonnet to English literature. He was born at Allington Castle near Maidstone in Kent, though the family wa ...

, one of the greatest poets of the Tudor period. In 1520, Wyatt married Elizabeth Cobham, who by many accounts was not a wife of his choosing. In 1525, Wyatt charged his wife with adultery and separated from her; coincidentally, historians believe that it was also the year when his interest in Anne intensified. In 1532, Wyatt accompanied the royal couple to Calais.

In 1526, Henry VIII became enamoured of Anne and began his pursuit. Anne was a skilful player at the game of courtly love, which was often played in the antechambers. This may have been how she caught the eye of Henry, who was also an experienced player. Some say that Anne resisted Henry's attempts to seduce her, refusing to become his mistress, and often leaving court for the seclusion of Hever Castle. But within a year, he proposed marriage to her, and she accepted. Both assumed an annulment could be obtained within months. There is no evidence to suggest that they engaged in a sexual relationship until very shortly before their marriage; Henry's love letters to Anne suggest that their love affair remained unconsummated for much of their seven-year courtship.

Henry's annulment

It is probable that Henry had thought of the idea of annulment (not divorce as commonly assumed) much earlier than this as he strongly desired a male heir to secure the Tudor claim to the crown. Before Henry VII ascended the throne, England was beset by civil warfare over rival claims to the crown, and Henry VIII wanted to avoid similar uncertainty over the succession. He and Catherine had no living sons: all Catherine's children except Mary died in infancy. Catherine had first come to England to be bride to Henry's brother Arthur, who died soon after their marriage. Since Spain and England still wanted an alliance, Pope Julius II granted a dispensation for their marriage on the grounds that Catherine was still a virgin. Catherine and Henry married in 1509 but eventually, he became dubious about the marriage's validity, claiming that Catherine's inability to provide an heir was a sign of God's displeasure. His feelings for Anne, and her refusals to become his mistress, probably contributed to Henry's decision that no Pope had a right to overrule the Bible. This meant that he had been living in sin with Catherine all these years, though Catherine hotly contested this and refused to concede that her marriage to Arthur had been consummated. It also meant that his daughter Mary was a bastard, and that the new pope ( Clement VII) would have to admit the previous pope's mistake and annul the marriage. Henry's quest for an annulment became euphemistically known as the " King's Great Matter". Anne saw an opportunity in Henry's infatuation and the convenient moral quandary. She determined that she would yield to his embraces only as his acknowledged queen. She began to take her place at his side in policy and in state, but not yet in his bed. Scholars and historians hold various opinions as to how deep Anne's commitment to the Reformation was, how much she was perhaps only personally ambitious, and how much she had to do with Henry's defiance of papal power. There is anecdotal evidence, related to biographer George Wyatt by her former lady-in-waitingAnne Gainsford

Anne Gainsford, Lady Zouche (died c.1590) was a close friend and lady-in-waiting to Queen consort Anne Boleyn.

She was in the household of Anne Boleyn, as early as 1528 before the latter became the second wife of Henry VIII of England five years ...

, that Anne brought to Henry's attention a heretical pamphlet, perhaps Tyndale's ''The Obedience of a Christian Man

''The Obedience of a Christen man, and how Christen rulers ought to govern, wherein also (if thou mark diligently) thou shalt find eyes to perceive the crafty of all .'' is a 1528 book by the English Protestant author William Tyndale. The spelling ...

'' or one by Simon Fish called ''A Supplication for the Beggars'', which cried out to monarchs to rein in the evil excesses of the Catholic Church. She was sympathetic to those seeking further reformation of the Church, and actively protected scholars working on English translations of the scriptures. According to Maria Dowling

Maria Dowling (1955–2011) was a historian. She was a senior lecturer in history at St Mary’s University College, Twickenham, England. Her best-known work is arguably ''Humanism in the Age of Henry VIII''.

References

1955 births

2011 ...

, "Anne tried to educate her waiting-women in scriptural piety" and is believed to have reproved her cousin, Mary Shelton

Mary Shelton (1510-1515 – 1570/71) was one of the contributors to the Devonshire manuscript. Either she or her sister Madge Shelton may have been a mistress of King Henry VIII.

Family

Both Margaret and Mary were daughters of Sir John Shel ...

, for "having 'idle poesies' written in her prayer book." If Cavendish is to be believed, Anne's outrage at Wolsey may have personalised whatever philosophical defiance she brought with her from France. Further, the most recent edition of Ives's biography admits that Anne may very well have had a personal spiritual awakening in her youth that spurred her on, not just as a catalyst but expediter for Henry's Reformation, though the process took years.

In 1528, sweating sickness broke out with great severity. In London, the mortality rate was great and the court was dispersed. Henry left London, frequently changing his residence; Anne Boleyn retreated to the Boleyn residence at Hever Castle, but contracted the illness; her brother-in-law, William Carey, died. Henry sent his own physician to Hever Castle to care for Anne, and shortly afterwards, she recovered.

Henry was soon absorbed in securing an annulment from Catherine. He set his hopes upon a direct appeal to the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

, acting independently of Wolsey, to whom he at first communicated nothing of his plans related to Anne. In 1527 William Knight William, Bill, or Billy Knight may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* William Frederick Knight (1933–2022), voice actor

* William Henry Knight (1823–1863), British painter

Politics

* William Knight (died 1622), Member of Parliament (MP) for ...

, the king's secretary, was sent to Pope Clement VII to sue for the annulment of Henry's marriage to Catherine, on the grounds that the dispensing bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not castrated) adult male of the species '' Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., cows), bulls have long been an important symbol in many religions,

incl ...

of Julius II permitting him to marry his brother's widow, Catherine, had been obtained under false pretences. Henry also petitioned, in the event of his becoming free, a dispensation to contract a new marriage with any woman even in the first degree of affinity, whether the affinity was contracted by lawful or unlawful connection. This clearly referred to Anne.

As Clement was at that time a prisoner of Charles V, the

As Clement was at that time a prisoner of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperator ...

, as a result of the Sack of Rome in May 1527, Knight had some difficulty obtaining access. In the end he had to return with a conditional dispensation, which Wolsey insisted was technically insufficient. Henry then had no choice but to put his great matter into Wolsey's hands, who did all he could to secure a decision in Henry's favour, even going so far as to convene an ecclesiastical court

An ecclesiastical court, also called court Christian or court spiritual, is any of certain courts having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. In the Middle Ages, these courts had much wider powers in many areas of Europe than be ...

in England, with a special emissary, Lorenzo Campeggio, from Clement to decide the matter. But Clement had not empowered his deputy to make a decision. He was still Charles V's hostage, and Charles V was loyal to his aunt Catherine. The pope forbade Henry to contract a new marriage until a decision was reached in Rome, not in England. Convinced that Wolsey's loyalties lay with the pope, not England, Anne, as well as Wolsey's many enemies, ensured his dismissal from public office in 1529. Cavendish, Wolsey's chamberlain, records that the servants who waited on the king and Anne at dinner in 1529 in Grafton heard her say that the dishonour Wolsey had brought upon the realm would have cost any other Englishman his head. Henry replied, "Why then I perceive...you are not the Cardinal's friend." Henry finally agreed to Wolsey's arrest on grounds of ''praemunire

In English history, ''praemunire'' or ''praemunire facias'' () refers to a 14th-century law that prohibited the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, or any other foreign jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the suprema ...

''. Had it not been for his death from illness in 1530, Wolsey might have been executed for treason. In 1531 (two years before Henry's marriage to Anne), Catherine was banished from court and her rooms given to Anne.

Public support remained with Catherine. One evening, in the autumn of 1531, Anne was dining at a manor house on the River Thames and was almost seized by a crowd of angry women. Anne just managed to escape by boat.

When Archbishop of Canterbury William Warham died in 1532, the Boleyn family chaplain, Thomas Cranmer, was appointed, with papal approval.

In 1532, Thomas Cromwell brought before Parliament a number of acts, including the Supplication against the Ordinaries and Submission of the Clergy, which recognised royal supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the ...

over the church, thus finalising the break with Rome. Following these acts, Thomas More resigned as Chancellor, leaving Cromwell as Henry's chief minister.

Premarital role and marriage

Even before her marriage, Anne Boleyn was able to grant petitions, receive diplomats and give patronage, and had an influence over Henry to plead the cause of foreign diplomats. During this period, Anne played an important role in England's international position by solidifying an alliance with France. She established an excellent rapport with the French ambassador,Gilles de la Pommeraie

Gilles de la Pommeraie was a 16th-century French diplomat and Baron d'Entrammes.

Biography

He was a member of the La Pommeraie family, from Brittany and serves Laval Family, and possessed land of Verger Castle of Montigné and d'Entrammes ( Mayen ...

. Anne and Henry attended a meeting with the French king at Calais in winter 1532, at which Henry hoped to enlist the support of Francis I of France for his intended marriage. On 1 September 1532, Henry granted her the Marquessate of Pembroke

Marquess of Pembroke was a title in the Peerage of England created by King Henry VIII for his future spouse Anne Boleyn.

Background

The then extinct title of Earl of Pembroke had been very significant for the House of Tudor. It was held by He ...

, an appropriate peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Bel ...

for a future queen; as such she became a rich and important woman: the three dukes and two marquesses who existed in 1532 were Henry's brother-in-law, Henry's illegitimate son and other descendants of royalty; she ranked above all other peeresses. The Pembroke lands and the title of Earl of Pembroke had been held by Henry's great-uncle, and Henry performed the investiture himself.

Anne's family also profited from the relationship. Her father, already Viscount Rochford, was created Earl of Wiltshire. Henry also came to an arrangement with Anne's Irish cousin and created him Earl of Ormond. At the magnificent banquet to celebrate her father's elevation, Anne took precedence over the Duchesses of Suffolk and Norfolk, seated in the place of honour beside the king that was usually occupied by the queen. Thanks to Anne's intervention, her widowed sister Mary received an annual pension of £100, and Mary's son, Henry Carey, was educated at a prestigious Cistercian monastery.

The conference at Calais was something of a political triumph, but even though the French government gave implicit support for Henry's remarriage and Francis I had a private conference with Anne, the French king maintained alliances with the Pope that he could not explicitly defy.

Soon after returning to Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

, Henry and Anne married in a secret ceremony on 14 November 1532. She soon became pregnant and, to legalise the first wedding considered to be unlawful at the time, there was a second wedding service, also private in accordance with The Royal Book, in London on 25 January 1533. Events now began to move at a quick pace. On 23 May 1533, Cranmer (who had been hastened, with the Pope's assent, into the position of Archbishop of Canterbury recently vacated by the death of Warham) sat in judgement at a special court convened at Dunstable Priory

The Priory Church of St Peter with its monastery (Dunstable Priory) was founded in 1132 by Henry I for Augustinian Canons in Dunstable, Bedfordshire, England. St Peter's today is only the nave of what remains of an originally much larger Augu ...

to rule on the validity of Henry's marriage to Catherine. He declared it null and void. Five days later, on 28 May 1533, Cranmer declared the marriage of Henry and Anne good and valid.

Queen of England: 1533–1536

Catherine was formally stripped of her title as queen and Anne was consequently crowned queen consort on 1 June 1533 in a magnificent ceremony at Westminster Abbey with a banquet afterwards. She was the last queen consort of England to be crowned separately from her husband. Unlike any other queen consort, Anne was crowned with St Edward's Crown, which had previously been used to crown only monarchs. Historian Alice Hunt suggests that this was done because Anne's pregnancy was visible by then and the child was presumed to be male.Alice Hunt, ''The Drama of Coronation: Medieval Ceremony in Early Modern England'', Cambridge University Press, 2008. On the previous day, Anne had taken part in an elaborate procession through the streets of London seated in a litter of "white cloth of gold" that rested on two palfreys clothed to the ground in white damask, while the barons of the Cinque Ports held a canopy of cloth of gold over her head. In accordance with tradition, she wore white, and on her head, a gold coronet beneath which her long dark hair hung down freely. The public's response to her appearance was lukewarm.

Meanwhile, the House of Commons had forbidden all appeals to Rome and exacted the penalties of ''

Catherine was formally stripped of her title as queen and Anne was consequently crowned queen consort on 1 June 1533 in a magnificent ceremony at Westminster Abbey with a banquet afterwards. She was the last queen consort of England to be crowned separately from her husband. Unlike any other queen consort, Anne was crowned with St Edward's Crown, which had previously been used to crown only monarchs. Historian Alice Hunt suggests that this was done because Anne's pregnancy was visible by then and the child was presumed to be male.Alice Hunt, ''The Drama of Coronation: Medieval Ceremony in Early Modern England'', Cambridge University Press, 2008. On the previous day, Anne had taken part in an elaborate procession through the streets of London seated in a litter of "white cloth of gold" that rested on two palfreys clothed to the ground in white damask, while the barons of the Cinque Ports held a canopy of cloth of gold over her head. In accordance with tradition, she wore white, and on her head, a gold coronet beneath which her long dark hair hung down freely. The public's response to her appearance was lukewarm.

Meanwhile, the House of Commons had forbidden all appeals to Rome and exacted the penalties of ''praemunire

In English history, ''praemunire'' or ''praemunire facias'' () refers to a 14th-century law that prohibited the assertion or maintenance of papal jurisdiction, or any other foreign jurisdiction or claim of supremacy in England, against the suprema ...

'' against all who introduced papal bulls into England. It was only then that Pope Clement, at last, took the step of announcing a provisional excommunication of Henry and Cranmer. He condemned the marriage to Anne, and in March 1534 declared the marriage to Catherine legal and again ordered Henry to return to her. Henry now required his subjects to swear an oath attached to the First Succession Act, which effectively rejected papal authority in legal matters and recognised Anne Boleyn as queen. Those who refused, such as Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

, who had resigned as Lord Chancellor, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, were placed in the Tower of London. In late 1534 parliament declared Henry "the only supreme head on earth of the Church of England". The Church in England was now under Henry's control, not Rome's. On 14 May 1534, in one of the realm's first official acts protecting Protestant Reformers

Protestant Reformers were those theologians whose careers, works and actions brought about the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century.

In the context of the Reformation, Martin Luther was the first reformer (sharing his views publicly in 15 ...

, Anne wrote a letter to Thomas Cromwell seeking his aid in ensuring that English merchant Richard Herman be reinstated a member of the merchant adventurers in Antwerp and no longer persecuted simply because he had helped in "setting forth of the New testament in English." Before and after her coronation, Anne protected and promoted evangelicals

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

and those wishing to study the scriptures of William Tyndale. She had a decisive role in influencing the Protestant reformer Matthew Parker to attend court as her chaplain, and before her death entrusted her daughter to Parker's care.

Struggle for a son

After her coronation, Anne settled into a quiet routine at the king's favourite residence, Greenwich Palace, to prepare for the birth of her baby. The child was born slightly prematurely on 7 September 1533 between three and four in the afternoon. Anne gave birth to a girl, who was christened Elizabeth, probably in honour of either or both Anne's mother Elizabeth Howard and Henry's mother, Elizabeth of York. But the birth of a girl was a heavy blow to her parents, who had confidently expected a boy. All but one of the royal physicians and astrologers had predicted a son and the French king had been asked to stand as his godfather. Now the prepared letters announcing the birth of a ''prince'' had an ''s'' hastily added to them to read ''princes ' and the traditional jousting tournament for the birth of an heir was cancelled. The infant princess was given a splendid christening, but Anne feared that Catherine's daughter, Mary, now stripped of her title of princess and labelled a bastard, posed a threat to Elizabeth's position. Henry soothed his wife's fears by separating Mary from her many servants and sending her to Hatfield House, where Elizabeth would live with her own sizeable staff of servants and the country air was thought better for the baby's health. Anne frequently visited her daughter at Hatfield and other residences.

The new queen had a larger staff of servants than Catherine. There were more than 250 servants to tend to her personal needs, from priests to stable boys, and more than 60 maids-of-honour who served her and accompanied her to social events. She also employed several priests who acted as her

The infant princess was given a splendid christening, but Anne feared that Catherine's daughter, Mary, now stripped of her title of princess and labelled a bastard, posed a threat to Elizabeth's position. Henry soothed his wife's fears by separating Mary from her many servants and sending her to Hatfield House, where Elizabeth would live with her own sizeable staff of servants and the country air was thought better for the baby's health. Anne frequently visited her daughter at Hatfield and other residences.

The new queen had a larger staff of servants than Catherine. There were more than 250 servants to tend to her personal needs, from priests to stable boys, and more than 60 maids-of-honour who served her and accompanied her to social events. She also employed several priests who acted as her confessors

Confessor is a title used within Christianity in several ways.

Confessor of the Faith

Its oldest use is to indicate a saint who has suffered persecution and torture for the faith but not to the point of death.Matthew Parker, who became one of the chief architects of Anglican thought during the reign of Anne's daughter, Elizabeth I.

The king and his new queen enjoyed a reasonably happy accord with periods of calm and affection. Anne's sharp intelligence, political acumen and forward manners, although desirable in a mistress, were, at the time, unacceptable in a wife. She was once reported to have spoken to her uncle in words that "shouldn't be used to a dog".Fraser. After a

The king and his new queen enjoyed a reasonably happy accord with periods of calm and affection. Anne's sharp intelligence, political acumen and forward manners, although desirable in a mistress, were, at the time, unacceptable in a wife. She was once reported to have spoken to her uncle in words that "shouldn't be used to a dog".Fraser. After a

Anne's biographer Eric Ives believes that her fall and execution were primarily engineered by her former ally Thomas Cromwell. The conversations between Chapuys and Cromwell thereafter indicate Cromwell as the instigator of the plot to remove Anne; evidence of this is seen in the ''

Anne's biographer Eric Ives believes that her fall and execution were primarily engineered by her former ally Thomas Cromwell. The conversations between Chapuys and Cromwell thereafter indicate Cromwell as the instigator of the plot to remove Anne; evidence of this is seen in the ''

The accused were found guilty and condemned to death. George Boleyn and the other accused men were executed on 17 May 1536. William Kingston, the Constable of the Tower, reported Anne seemed very happy and ready to be done with life. Henry commuted Anne's sentence from burning to beheading, and rather than have a queen beheaded with the common axe, he brought an expert swordsman from Saint-Omer in France, to perform the execution. On the morning of 19 May, Kingston wrote:

Her impending death may have caused her great sorrow for some time during her imprisonment. The poem "

The accused were found guilty and condemned to death. George Boleyn and the other accused men were executed on 17 May 1536. William Kingston, the Constable of the Tower, reported Anne seemed very happy and ready to be done with life. Henry commuted Anne's sentence from burning to beheading, and rather than have a queen beheaded with the common axe, he brought an expert swordsman from Saint-Omer in France, to perform the execution. On the morning of 19 May, Kingston wrote:

Her impending death may have caused her great sorrow for some time during her imprisonment. The poem "

The ermine mantle was removed and Anne lifted off her headdress, tucking her hair under a coif. After a brief farewell to her weeping ladies and a request for prayers, she knelt down and one of her ladies tied a blindfold over her eyes. She knelt upright, in the French style of beheadings. Her final prayer consisted of her repeating continually, "

The ermine mantle was removed and Anne lifted off her headdress, tucking her hair under a coif. After a brief farewell to her weeping ladies and a request for prayers, she knelt down and one of her ladies tied a blindfold over her eyes. She knelt upright, in the French style of beheadings. Her final prayer consisted of her repeating continually, " Cranmer felt vulnerable because of his closeness to the queen; on the night before the execution, he declared Henry's marriage to Anne to have been void, like Catherine's before her. He made no serious attempt to save Anne's life, although some sources record that he had prepared her for death by hearing her last private confession of sins, in which she had stated her innocence before God.Schama, p. 307. On the day of her death, a Scottish friend found Cranmer weeping uncontrollably in his London gardens, saying that he was sure that Anne had now gone to Heaven.

She was then buried in an unmarked grave in the Chapel of

Cranmer felt vulnerable because of his closeness to the queen; on the night before the execution, he declared Henry's marriage to Anne to have been void, like Catherine's before her. He made no serious attempt to save Anne's life, although some sources record that he had prepared her for death by hearing her last private confession of sins, in which she had stated her innocence before God.Schama, p. 307. On the day of her death, a Scottish friend found Cranmer weeping uncontrollably in his London gardens, saying that he was sure that Anne had now gone to Heaven.

She was then buried in an unmarked grave in the Chapel of

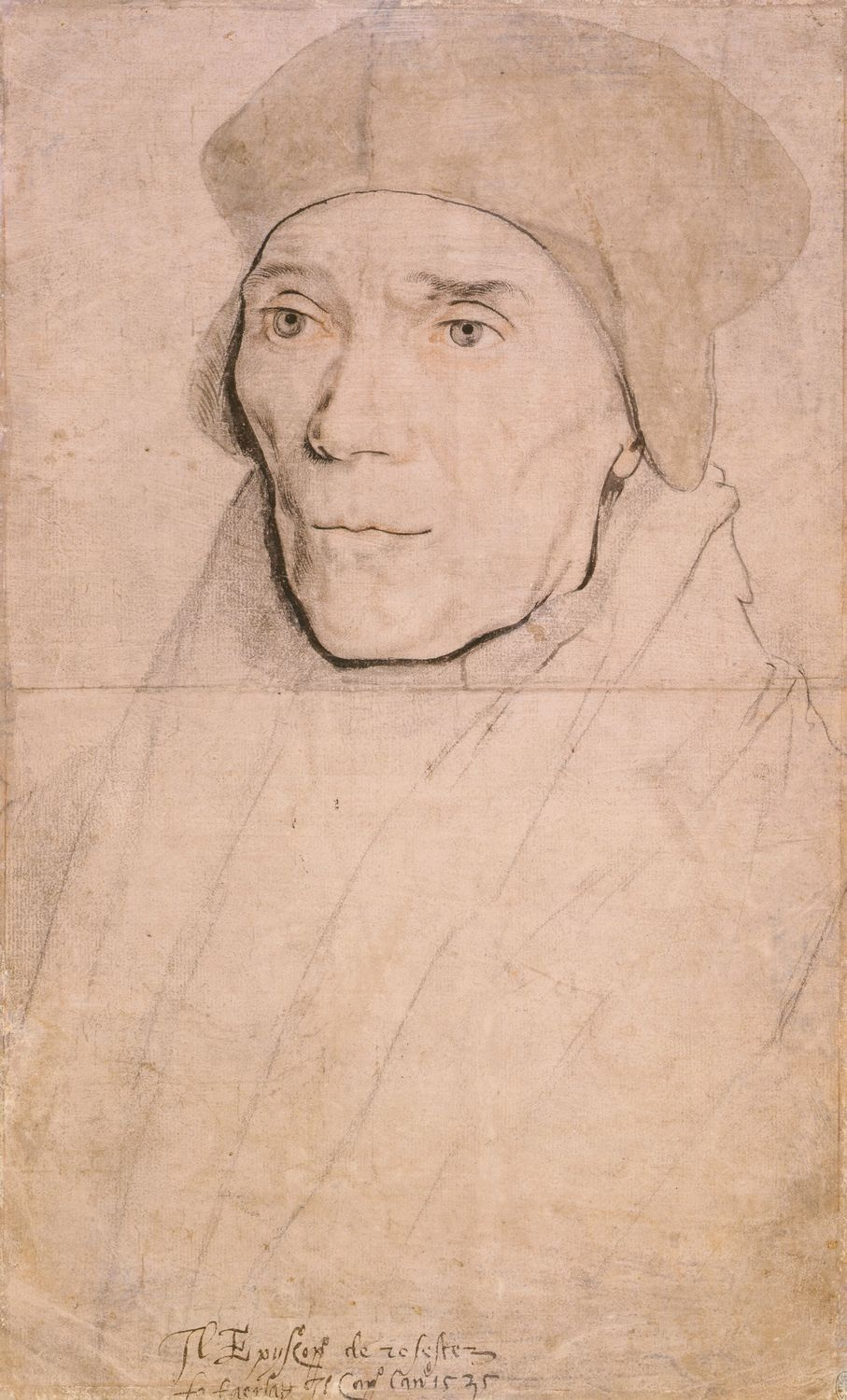

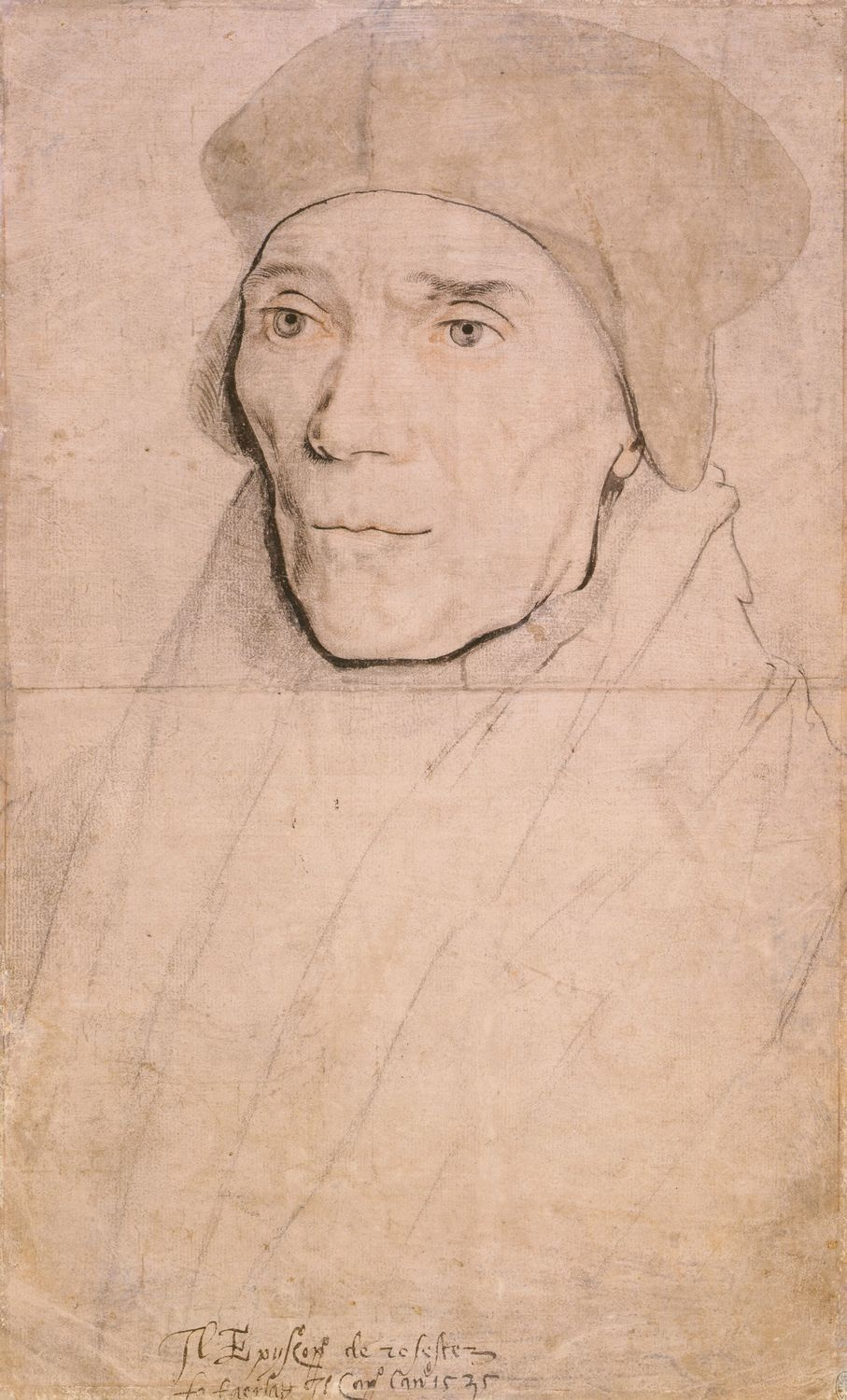

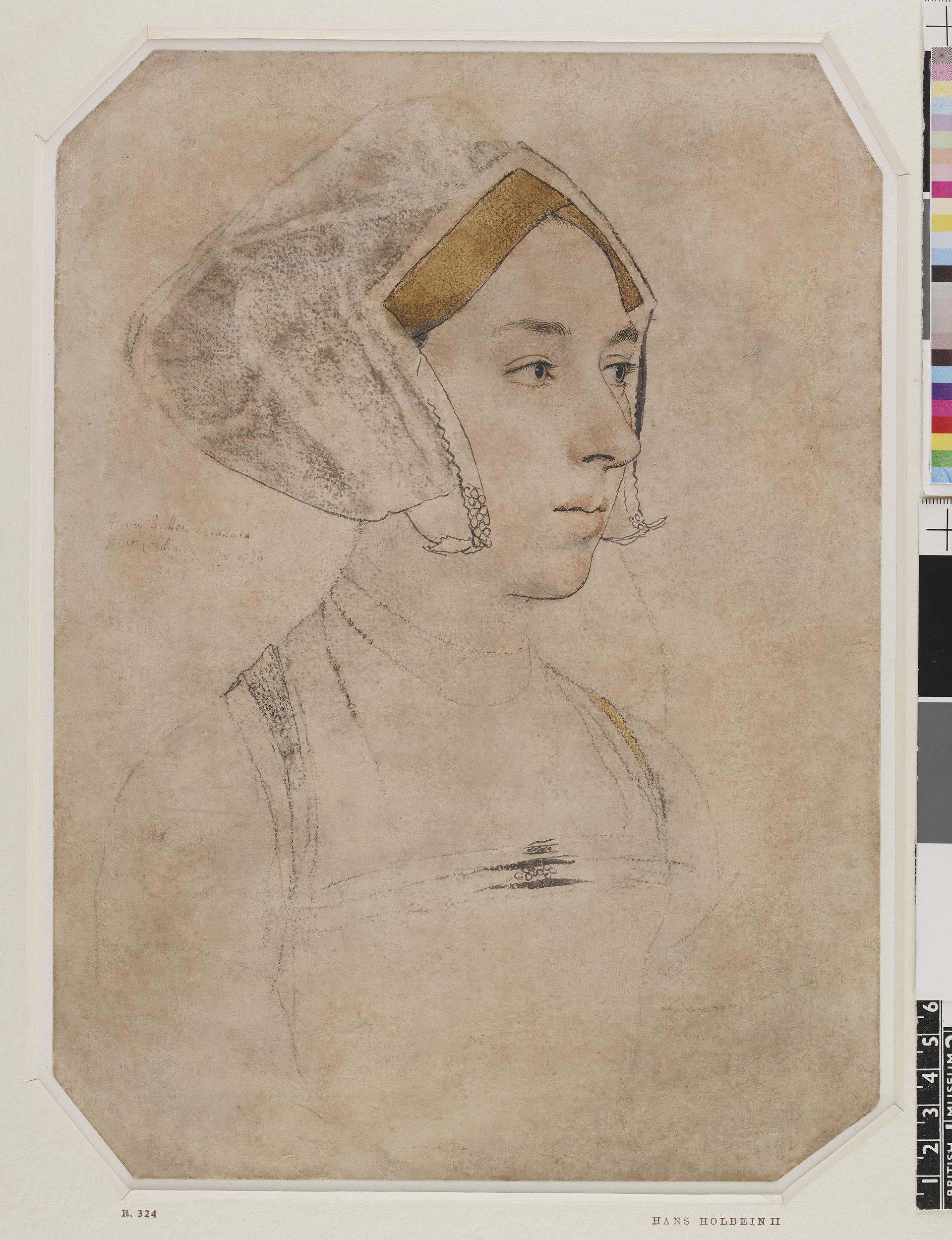

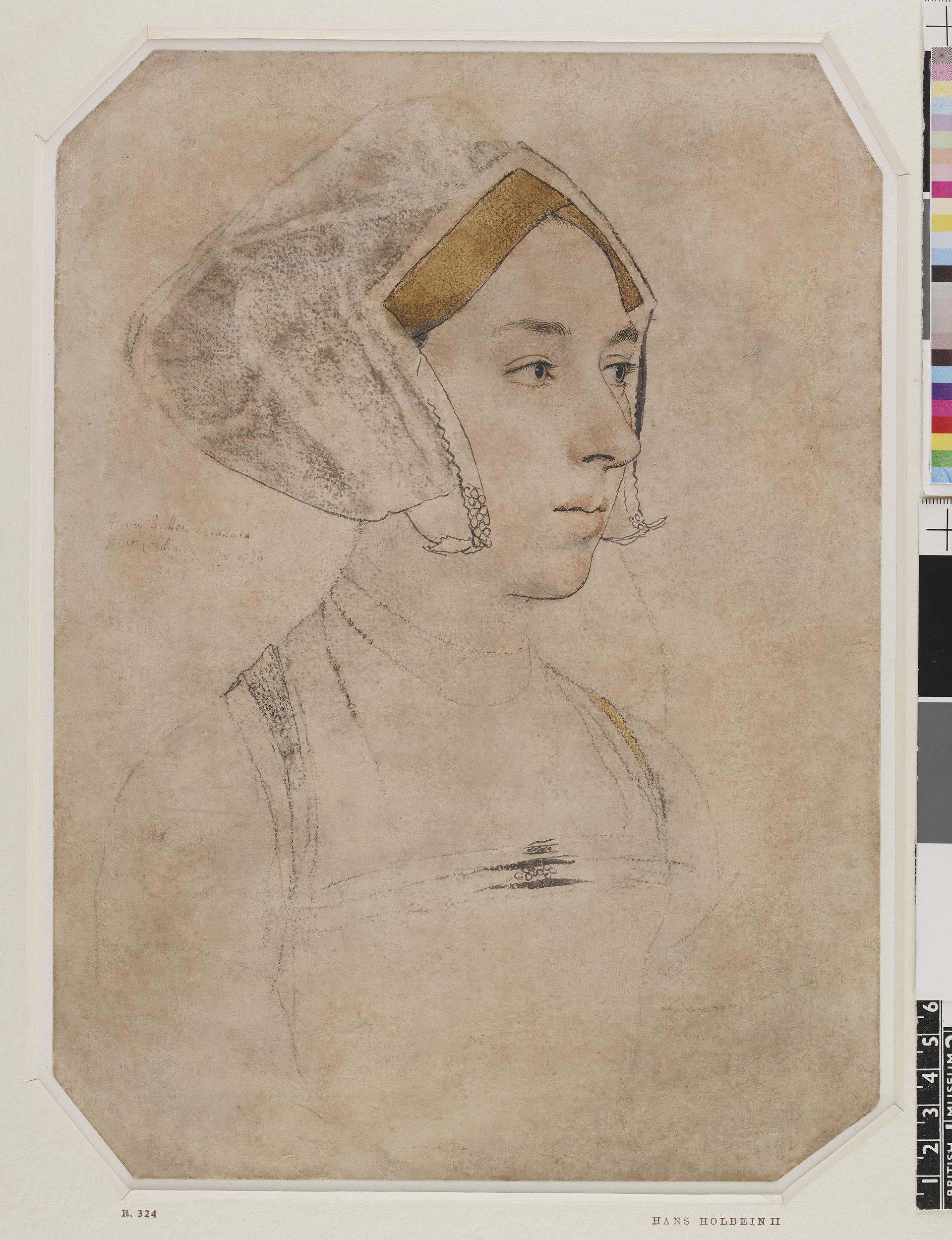

Anne's appearance has been much discussed by historians, as all of her portraits were destroyed following an order by Henry VIII, who wanted to erase her from history. Many surviving depictions of her may be copies of a lost original that apparently existed as late as 1773. One of the only contemporary likenesses of Anne was captured on a medal referred to as "The Moost Happi Medal" which was struck in 1536, probably to celebrate her pregnancy which occurred around that time. The other possible portrait of Anne was a secret locket ring that her daughter Elizabeth I possessed and was taken from one of her fingers at her death in 1603.

Another possible portrait of Anne was discovered in 2015 painted by artist Nidd Hall. Some scholars believe that it portrays Anne because it resembles the 1536 medal more than any other depiction. However, others believe that it is actually a portrait of her successor Jane Seymour.

Anne's appearance has been much discussed by historians, as all of her portraits were destroyed following an order by Henry VIII, who wanted to erase her from history. Many surviving depictions of her may be copies of a lost original that apparently existed as late as 1773. One of the only contemporary likenesses of Anne was captured on a medal referred to as "The Moost Happi Medal" which was struck in 1536, probably to celebrate her pregnancy which occurred around that time. The other possible portrait of Anne was a secret locket ring that her daughter Elizabeth I possessed and was taken from one of her fingers at her death in 1603.

Another possible portrait of Anne was discovered in 2015 painted by artist Nidd Hall. Some scholars believe that it portrays Anne because it resembles the 1536 medal more than any other depiction. However, others believe that it is actually a portrait of her successor Jane Seymour.

Hans Holbein originally painted Anne's portrait and also sketched her during her lifetime. There are two surviving sketches that have been identified to be of Anne, by historians and people who knew her. Most scholars believe that Anne cannot be one of the two, as the portrayals do not look similar to each other, whilst others think that they do show the same woman but in one sketch she is pregnant, whilst in the other she is not.

She was considered brilliant, charming, driven, elegant, forthright and graceful, with a keen wit and a lively, opinionated and passionate personality. Anne was depicted as "sweet and cheerful" in her youth and enjoyed cards and dice games, drinking wine, French cuisine, flirting, gambling, gossiping and good jokes. She was fond of archery, falconry, hunting and the occasional game of bowls. She also had a sharp tongue and a terrible temper.

Anne exerted a powerful charm on those who met her, though opinions differed on her attractiveness. The Venetian diarist Marino Sanuto, who saw Anne when Henry VIII met Francis I at

Hans Holbein originally painted Anne's portrait and also sketched her during her lifetime. There are two surviving sketches that have been identified to be of Anne, by historians and people who knew her. Most scholars believe that Anne cannot be one of the two, as the portrayals do not look similar to each other, whilst others think that they do show the same woman but in one sketch she is pregnant, whilst in the other she is not.

She was considered brilliant, charming, driven, elegant, forthright and graceful, with a keen wit and a lively, opinionated and passionate personality. Anne was depicted as "sweet and cheerful" in her youth and enjoyed cards and dice games, drinking wine, French cuisine, flirting, gambling, gossiping and good jokes. She was fond of archery, falconry, hunting and the occasional game of bowls. She also had a sharp tongue and a terrible temper.

Anne exerted a powerful charm on those who met her, though opinions differed on her attractiveness. The Venetian diarist Marino Sanuto, who saw Anne when Henry VIII met Francis I at

in JSTOR

* Brigden, Susan ''New Worlds, Lost Worlds'' (2000) * * Elton, G. R. ''Reform and Reformation.'' London: Edward Arnold, 1977. . * Davenby, C "''Objects of Patriarchy''" (2012) (Feminist Study) * Dowling, Maria "A Woman's Place? Learning and the Wives of King Henry VII." ''History Today'', 38–42 (1991). * Dowling, Maria ''Humanism in the Age of Henry the VIII'' (1986) * * Fraser, Antonia ''The Wives of Henry VIII'' New York: Knopf (1992) * Graves, Michael ''Henry VIII.'' London, Pearson Longman, 2003 * * Haigh, Christopher ''English Reformations'' (1993) * Hibbert, Christopher ''Tower of London: A History of England From the Norman Conquest'' (1971) * Ives, Eric ''The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn'' (2004) * * Ives, E. W. "Anne (c.1500–1536)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,'' (2004

accessed 8 September 2011

* Lacey, Robert ''The Life and Times of Henry VIII'' (1972) * Lehmberg, Stanford E. ''The Reformation Parliament, 1529–1536'' (1970) * * Lindsey, Karen ''Divorced Beheaded Survived: A Feminist Reinterpretation of the Wives of Henry VIII'' (1995) * MacCulloch, Diarmaid ''Thomas Cranmer'' New Haven: Yale University Press (1996) . * Morris, T. A. ''Europe and England in the Sixteenth Century'' (1998) * Norton, Elizabeth ''Anne Boleyn: Henry VIII's Obsession'' 2009 hardback paperback * Parker, K. T. ''The Drawings of Hans Holbein at Windsor Castle'' Oxford: Phaidon (194

OCLC 822974.

* Rowlands, John ''The Age of Dürer and Holbein'' London: British Museum (1988) * Scarisbrick, J. J. ''Henry VIII'' (1972) * Schama, Simon ''A History of Britain: At the Edge of the World?: 3000 BC–AD 1603'' (2000) * * * Schofield, John. ''The Rise & Fall of Thomas Cromwell.'' Stroud (UK): The History Press, 2008. . * Somerset, Anne ''Elizabeth I.'' London: Phoenix (1997) * Starkey, David ''Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII'' (2003) * Strong, Roy ''Tudor & Jacobean Portraits''. London: HMSO (196

OCLC 71370718.

* Walker, Greg. "Rethinking the Fall of Anne Boleyn," ''Historical Journal,'' March 2002, Vol. 45 Issue 1, pp 1–29; blames what she said in incautious conversations with the men who were executed with her * Warnicke, Retha M. "The Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Reassessment," ''History,'' Feb 1985, Vol. 70 Issue 228, pp 1–15; stresses role of Sir Thomas Cromwell, the ultimate winner *

in JSTOR

* Warnicke, Retha M. ''The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family politics at the court of Henry VIII'' (1989) * Warnicke, Retha M. "Sexual heresy at the court of Henry VIII." ''Historical Journal'' 30.2 (1987): 247–268. * * Weir, Allison "The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn" * Williams, Neville ''Henry VIII and His Court'' (1971). * Wilson, Derek ''Hans Holbein: Portrait of an Unknown Man'' London: Pimlico, Revised Edition (2006) * Wooding, Lucy ''Henry VIII'' London: Routledge, 2009

Leanda de Lisle: Why Anne Boleyn was Beheaded with a Sword and not an Axe

The Anne Boleyn Files

Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn : the love letters

at the

Queen Anne Boleyn Website

Norfolk, UK * * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Boleyn, Anne 1500s births 1536 deaths 16th-century English women Annulment Anne Burials at the Church of St Peter ad Vincula Converts to Anglicanism from Roman Catholicism Hereditary peeresses created by Henry VIII Daughters of British earls English Anglicans Executed English women Executed royalty People convicted under a bill of attainder Executions at the Tower of London Howard family (English aristocracy) British maids of honour Pembroke, Anne Boleyn, 1st Marquess of People executed by Tudor England by decapitation People executed for adultery People executed under Henry VIII People executed under the Tudors for treason against England People from Sevenoaks District People from Blickling Wives of Henry VIII Year of birth uncertain 16th-century Anglicans Household of Catherine of Aragon Court of Francis I of France

Strife with the king

The king and his new queen enjoyed a reasonably happy accord with periods of calm and affection. Anne's sharp intelligence, political acumen and forward manners, although desirable in a mistress, were, at the time, unacceptable in a wife. She was once reported to have spoken to her uncle in words that "shouldn't be used to a dog".Fraser. After a

The king and his new queen enjoyed a reasonably happy accord with periods of calm and affection. Anne's sharp intelligence, political acumen and forward manners, although desirable in a mistress, were, at the time, unacceptable in a wife. She was once reported to have spoken to her uncle in words that "shouldn't be used to a dog".Fraser. After a stillbirth

Stillbirth is typically defined as fetal death at or after 20 or 28 weeks of pregnancy, depending on the source. It results in a baby born without signs of life. A stillbirth can result in the feeling of guilt or grief in the mother. The term ...

or miscarriage as early as Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

1534, Henry was discussing with Cranmer and Cromwell the possibility of divorcing her without having to return to Catherine.Williams, p.138. Nothing came of the matter as the royal couple reconciled and spent summer 1535 on progress. By October, she was again pregnant.

Anne presided over a court. She spent lavish amounts of money on gowns, jewels, head-dresses, ostrich-feather fans, riding equipment, furniture and upholstery, maintaining the ostentatious display required by her status. Numerous palaces were renovated to suit her and Henry's extravagant tastes. Her motto was "The most happy", and she chose a white falcon as her personal device.

Anne was blamed for Henry's tyranny and called by some of her subjects "the king's whore" or a "naughty paike rostitute. Public opinion turned further against her after her failure to produce a son. It sank even lower after the executions of her enemies More and Fisher.

Downfall and execution: 1536

On 8 January 1536, news of Catherine of Aragon's death reached the king and Anne, who were overjoyed. The following day, Henry and Anne wore yellow, a symbol of joy and celebration in England but of mourning in Spain, from head to toe, and celebrated Catherine's death with festivities. With Catherine dead, Anne attempted to make peace with Mary. Mary rebuffed Anne's overtures, perhaps because of rumours circulating that Catherine had been poisoned by Anne or Henry. These began after the discovery during her embalming that Catherine's heart was blackened. Modern medical experts are in agreement that this was not the result of poisoning, but of cancer of the heart, an extremely rare condition which was not understood at the time. Queen Anne, pregnant again, was aware of the dangers if she failed to give birth to a son. With Catherine dead, Henry would be free to marry without any taint of illegality. At this time, Henry began paying court to one of Anne's maids-of-honour, Jane Seymour, and allegedly gave her a locket containing aportrait miniature

A portrait miniature is a miniature portrait painting, usually executed in gouache, watercolor, or enamel. Portrait miniatures developed out of the techniques of the miniatures in illuminated manuscripts, and were popular among 16th-century eli ...

of himself. While wearing this locket in the presence of Anne, Jane began opening and closing it. Anne responded by ripping the locket off Jane's neck with such force that her fingers bled.

Later that month, the king was unhorsed in a tournament and knocked unconscious for two hours, a worrying incident that Anne believed led to her miscarriage five days later. Another possible cause of the miscarriage was an incident in which, upon entering a room, Anne saw Jane Seymour sitting on Henry's lap and flew into a rage. Whatever the cause, on the day that Catherine of Aragon was buried at Peterborough Abbey, Anne miscarried a baby which, according to the imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys, she had borne for about three and a half months, and which "seemed to be a male child". Chapuys commented "She has miscarried of her saviour." In Chapuys' opinion, this loss was the beginning of the end of the royal marriage.

Given Henry's desperate desire for a son, the sequence of Anne's pregnancies has attracted much interest. Mike Ashley speculated that Anne had two stillborn children after Elizabeth's birth and before the male child she miscarried in 1536. Most sources attest only to the birth of Elizabeth in September 1533, a possible miscarriage in the summer of 1534, and the miscarriage of a male child, of almost four months' gestation, in January 1536. As Anne recovered from her miscarriage, Henry declared that he had been seduced into the marriage by means of "sortilege" – a French term indicating either "deception" or "spells". His new mistress, Jane Seymour, was quickly moved into royal quarters. This was followed by Anne's brother George being refused a prestigious court honour, the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George C ...

, given instead to Sir Nicholas Carew.

Charges of adultery, incest and treason

Anne's biographer Eric Ives believes that her fall and execution were primarily engineered by her former ally Thomas Cromwell. The conversations between Chapuys and Cromwell thereafter indicate Cromwell as the instigator of the plot to remove Anne; evidence of this is seen in the ''

Anne's biographer Eric Ives believes that her fall and execution were primarily engineered by her former ally Thomas Cromwell. The conversations between Chapuys and Cromwell thereafter indicate Cromwell as the instigator of the plot to remove Anne; evidence of this is seen in the ''Spanish Chronicle The Chronicle of King Henry VIII. of England, commonly known as the Spanish Chronicle is a chronicle written during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI by an unknown author.

The chronicle was translated from Spanish and published with notes in 1 ...

'' and through letters written from Chapuys to Charles V. Anne argued with Cromwell over the redistribution of Church revenues and over foreign policy. She advocated that revenues be distributed to charitable and educational institutions; and she favoured a French alliance. Cromwell insisted on filling the king's depleted coffers, while taking a cut for himself, and preferred an imperial alliance. For these reasons, Ives suggests, "Anne Boleyn had become a major threat to Thomas Cromwell." Cromwell's biographer John Schofield, on the other hand, contends that no power struggle existed between Anne and Cromwell and that "not a trace can be found of a Cromwellian conspiracy against Anne ... Cromwell became involved in the royal marital drama only when Henry ordered him onto the case." Cromwell did not manufacture the accusations of adultery, though he and other officials used them to bolster Henry's case against Anne. Warnicke questions whether Cromwell could have or wished to manipulate the king in such a matter. Such a bold attempt by Cromwell, given the limited evidence, could have risked his office, even his life. Henry himself issued the crucial instructions: his officials, including Cromwell, carried them out. The result was by modern standards a legal travesty; however, the rules of the time were not bent in order to assure a conviction; there was no need to tamper with rules that guaranteed the desired result since law at the time was an engine of state, not a mechanism for justice.

Towards the end of April, a Flemish musician in Anne's service named Mark Smeaton was arrested. He initially denied being the queen's lover but later confessed, perhaps after being tortured or promised freedom. Another courtier, Sir Henry Norris, was arrested on May Day, but being an aristocrat, could not be tortured. Prior to his arrest, Norris was treated kindly by the king, who offered him his own horse to use on the May Day festivities. It seems likely that during the festivities, the king was notified of Smeaton's confession and it was shortly thereafter the alleged conspirators were arrested upon his orders. Norris denied his guilt and swore that Queen Anne was innocent; one of the most damaging pieces of evidence against Norris was an overheard conversation with Anne at the end of April, where she accused him of coming often to her chambers not to pay court to her lady-in-waiting Madge Shelton but to herself. Sir Francis Weston

Sir Francis Weston KB (1511 – 17 May 1536) was a gentleman of the Privy Chamber at the court of King Henry VIII of England. He became a friend of the king but was later accused of high treason and adultery with Anne Boleyn, the king's seco ...

was arrested two days later on the same charge, as was Sir William Brereton, a groom of the king's Privy Chamber. Sir Thomas Wyatt

Sir Thomas Wyatt (150311 October 1542) was a 16th-century English politician, ambassador, and lyric poet credited with introducing the sonnet to English literature. He was born at Allington Castle near Maidstone in Kent, though the family wa ...

, a poet and friend of the Boleyns who was allegedly infatuated with her before her marriage to the king, was also imprisoned for the same charge but later released, most likely due to his or his family's friendship with Cromwell. Sir Richard Page

Sir Richard Page (died 1548) was an English courtier. He was a gentleman of the Privy Chamber at the court of Henry VIII of England, and Vice-Chamberlain in the household of Henry VIII's illegitimate son, Henry FitzRoy. Page was imprisoned in th ...

was also accused of having a sexual relationship with the queen, but he was acquitted of all charges after further investigation could not implicate him with Anne. The final accused was Queen Anne's own brother, George Boleyn, arrested on charges of incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity ( marriage or stepfamily), ado ...

and treason. He was accused of two incidents of incest: November 1535 at Whitehall and the following month at Eltham.Ives, p. 344.

On 2 May 1536, Anne was arrested and taken to the Tower of London by barge. It is likely that Anne may have entered through the Court Gate in the Byward Tower rather than the Traitors' Gate, according to historian and author of ''The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn'', Eric Ives. In the Tower, she collapsed, demanding to know the location of her father and "swete broder", as well as the charges against her.

In what is reputed to be her last letter to Henry, dated 6 May, she wrote:

Four of the accused men were tried in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buck ...

on 12 May 1536. Weston, Brereton and Norris publicly maintained their innocence and only Smeaton supported the Crown by pleading guilty. Three days later, Anne and George Boleyn were tried separately in the Tower of London, before a jury of 27 peers

Peers may refer to:

People

* Donald Peers

* Edgar Allison Peers, English academician

* Gavin Peers

* John Peers, Australian tennis player

* Kerry Peers

* Mark Peers

* Michael Peers

* Steve Peers

* Teddy Peers (1886–1935), Welsh international ...

. She was accused of adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and leg ...

, incest, and high treason. By the Treason Act of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

, adultery on the part of a queen was a form of treason (because of the implications for the succession to the throne) for which the penalty was hanging, drawing and quartering

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry I ...

for a man and burning alive

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

for a woman, but the accusations, and especially that of incestuous adultery, were also designed to impugn her moral character. The other form of treason alleged against her was that of plotting the king's death, with her "lovers", so that she might later marry Henry Norris. Anne's one-time betrothed, Henry Percy, 6th Earl of Northumberland, sat on the jury that unanimously found Anne guilty. When the verdict was announced, he collapsed and had to be carried from the courtroom. He died childless eight months later and was succeeded by his nephew

In the lineal kinship system used in the English-speaking world, a niece or nephew is a child of the subject's sibling or sibling-in-law. The converse relationship, the relationship from the niece or nephew's perspective, is that of an ...

.

On 17 May, Cranmer declared Anne's marriage to Henry null and void.

Final hours

The accused were found guilty and condemned to death. George Boleyn and the other accused men were executed on 17 May 1536. William Kingston, the Constable of the Tower, reported Anne seemed very happy and ready to be done with life. Henry commuted Anne's sentence from burning to beheading, and rather than have a queen beheaded with the common axe, he brought an expert swordsman from Saint-Omer in France, to perform the execution. On the morning of 19 May, Kingston wrote:

Her impending death may have caused her great sorrow for some time during her imprisonment. The poem "

The accused were found guilty and condemned to death. George Boleyn and the other accused men were executed on 17 May 1536. William Kingston, the Constable of the Tower, reported Anne seemed very happy and ready to be done with life. Henry commuted Anne's sentence from burning to beheading, and rather than have a queen beheaded with the common axe, he brought an expert swordsman from Saint-Omer in France, to perform the execution. On the morning of 19 May, Kingston wrote: